Tim Mathis's Blog, page 9

March 17, 2020

Is it ok to send my kids hiking with their grandma during the COVID-19 Pandemic?

When Angel Mathis isn’t instigating adventure through Boldly Went, she’s caring for patients as a nurse practitioner, and in recent weeks that’s meant she’s been fully consumed with helping people across Washington State navigate the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis. We know that many of you are out there on lockdown, and, like us, you probably don’t do well being forced to stay inside for hours at a time, let alone weeks. Here we are sharing our expert advice on how to play outside safely when you’re self-isolating during a pandemic. (I know, I never imagined I’d type those words either, but here we are!)

When Tim Mathis isn't instigating adventures, he's writing bios for Angel and calming people the eff down. Seriously. He's a psych nurse and he's really good at it. He's also a great writer, editor, friend, and husband.

Bonus for those of you with short attention spans! In case you don’t want to read the whole article, here are some quick TL;DR Pandemic Guidelines:Playing outside is great. Sun kills viruses (though we’re not sure how quickly in this case). The virus (except under very unusual circumstances) is not airborne. It’s droplet. That’s different. Read on for detailed info. Indoor public spaces associated with playing outside are still cesspools, but even bigger cesspools - public restrooms, visitor centers, cafes, etc. Avoid them. Crowded outdoor spaces like playgrounds are likely a bad idea - especially for kids or anyone who has to (gets to!) come into contact with them. Shared equipment is also a bad idea - including ball sports, playgrounds, rented equipment, etc. The closer to the hands or face, the worse. Go play outside to keep yourself sane, but still avoid the crowds and do activities that don’t involve interpersonal touching or shared equipment - like hiking, running, biking, walking, birding, gardening, or paddling.

Soooo….

You heard the news, your city’s shut down, your kids’ school is cancelled, you’re working from home or not at all, and the world is freaking out. You’re supposed to be keeping your distance from other humans (6 feet folks!), but most of your coping skills involve either going outside to play yourself, or sending your kids outside to play.

This stuff is stressful. This is going to be rough.

Well, we here at Boldly Went have at least a little bit of good news: social distancing responsibly doesn’t mean staying inside - though you should follow some basic guidelines.

How can I be sure I’m not spreading disease around?

Read more by selecting your preferred option below. Download Free E-Book with this complete article and all COVID 19 Content No, thanks, take me to this full blog post

When Tim Mathis isn't instigating adventures, he's writing bios for Angel and calming people the eff down. Seriously. He's a psych nurse and he's really good at it. He's also a great writer, editor, friend, and husband.

Bonus for those of you with short attention spans! In case you don’t want to read the whole article, here are some quick TL;DR Pandemic Guidelines:Playing outside is great. Sun kills viruses (though we’re not sure how quickly in this case). The virus (except under very unusual circumstances) is not airborne. It’s droplet. That’s different. Read on for detailed info. Indoor public spaces associated with playing outside are still cesspools, but even bigger cesspools - public restrooms, visitor centers, cafes, etc. Avoid them. Crowded outdoor spaces like playgrounds are likely a bad idea - especially for kids or anyone who has to (gets to!) come into contact with them. Shared equipment is also a bad idea - including ball sports, playgrounds, rented equipment, etc. The closer to the hands or face, the worse. Go play outside to keep yourself sane, but still avoid the crowds and do activities that don’t involve interpersonal touching or shared equipment - like hiking, running, biking, walking, birding, gardening, or paddling.

Soooo….

You heard the news, your city’s shut down, your kids’ school is cancelled, you’re working from home or not at all, and the world is freaking out. You’re supposed to be keeping your distance from other humans (6 feet folks!), but most of your coping skills involve either going outside to play yourself, or sending your kids outside to play.

This stuff is stressful. This is going to be rough.

Well, we here at Boldly Went have at least a little bit of good news: social distancing responsibly doesn’t mean staying inside - though you should follow some basic guidelines.

How can I be sure I’m not spreading disease around?

Read more by selecting your preferred option below. Download Free E-Book with this complete article and all COVID 19 Content No, thanks, take me to this full blog post

Published on March 17, 2020 11:47

March 2, 2020

January 22, 2020

Oregon Timber Trail

In part 2 of our 3 part mini-series all about bikes in January 2020, we heard from Heather VanValkenburg. Heather was kind enough to share some details and tips for the Oregon Timber Trail (OTT). We're sharing them with you here!

In part 2 of our 3 part mini-series all about bikes in January 2020, we heard from Heather VanValkenburg. Heather was kind enough to share some details and tips for the Oregon Timber Trail (OTT). We're sharing them with you here! Listen to the OTT episode: Field Notes 133: Bikepacking the Oregon Timber Trail

Check out the other episodes in our bike mini series:Episode 134: Coming soon! Field Notes 132: Bike Touring. Olympic Coast, Ghana, & Midwestern USA Heather VanValkenburg's Sage Advice about the OTT

Heather VanValkenburg on the Oregon Timber Trail. She did have fun sometimes! I started a blog last summer when I did the Oregon Timber Trail. Last night's story (Episode 133) is from one of the last entries (day14).

Heather VanValkenburg on the Oregon Timber Trail. She did have fun sometimes! I started a blog last summer when I did the Oregon Timber Trail. Last night's story (Episode 133) is from one of the last entries (day14). Here is the Oregon Timber Trail Website. We used the maps and descriptions on here to plan our trip. Although all former bike racers, we were not in a hurry to do this quickly. We planned on 30-40 miles a day, with resupply boxes every 3 days. We later decided that the resupply days are also good days to get a hotel or other bed to sleep in with showers and electricity for charging our phones, Garmin computers, and other devices.

I think that particular section of the OTT that I describe is a mix of high desert and volcanic remains, hence the sand. Most of the time, if you're going to ride over so much sand, you will choose tires that are much wider than what I was riding. I had 2.3 size tires. which are fairly standard. A 2.4 or 2.5 or even 3.0 tire would be wider, have more float, and be easier to ride in sand.

BUT, the full trip was over 500 miles and this section was about 14 miles. So, a rider has to choose a tire that will work for them for the duration. I wish I would have gone with a slightly wider tire. The chain didn't really pick up sand while we rode. This sand was about 2-6 inches deep, getting nowhere near our chains, but we did a little bike maintenance every night, including wiping down and lubing chains. I think, also, I was mentally ready to be off my bike for a while, and on this last day, we were just moving SO SLOW on flat terrain.

I used to race cyclocross too, and there is often sand in the races, so I have some experience with it. The best advice I have is to pick a small gear and maintain a steady, consistent spin. Riding in the sand is a little like driving on ice -no sudden or hard forced pedal strokes.

And swearing. Swearing really helps too.

Visit Heather's blog to read more details about her experience on the OTT and (hopefully soon) about Heather's trip to Peru to ride some downhill mountain bike routes and go on a high fiving mission, and riding the Annapurna Circuit in Nepal. Girl gets around!

Here are some more photos from Heather's OTT trip. Photos of the day that she described are the one's past where she took a photo of the forecast on the TV that says HOT, nearer to the bottom.

Heather VanValkenburg wasn't lying when she said it was hot and she's got the evidence to prove it. Listen to the original episode: Field Notes 133: Bikepacking the Oregon Timber Trail

Heather VanValkenburg wasn't lying when she said it was hot and she's got the evidence to prove it. Listen to the original episode: Field Notes 133: Bikepacking the Oregon Timber TrailCheck out the other episodes in our bike mini series:Episode 134: Coming soon! Field Notes 132: Bike Touring. Olympic Coast, Ghana, & Midwestern USA

Want to figure out how you can make adventure your lifestyle too? You need to read our book, The Dirtbag's Guide to Life.

If you like this, support us on Patreon! We really need your help to make this production happen each week. Become a Patron!

Published on January 22, 2020 18:11

January 12, 2020

Ally Mantey on learning to sail in land locked Alberta

I caught up with Ally after hearing her story in Canmore, which was featured in Episode 130 of the Boldly Went Podcast. I thought it was so interesting that she decided that sailing was a lifestyle she wanted to pursue, especially coming from land-locked Alberta. She shares her thoughts about jumping off the corporate ladder, coming to terms with being a dirtbag, and what it takes to embrace adventure as a lifestyle.

If you want to learn more about what it takes to make moves similar to Ally, you'll like our book. Meet Ally Mantey, Sailor Allyson was once a corporate-chick who realized in her early 30's that the dream to climb the corporate ladder was not for her. Despite growing up on the East-Coast of Canada, she had never sailed before.

Allyson was once a corporate-chick who realized in her early 30's that the dream to climb the corporate ladder was not for her. Despite growing up on the East-Coast of Canada, she had never sailed before.

At the age of 34 she decided to buy a 26 foot trailorable sailboat, Seaweasel, with her husband Steve. In the 5 years following, they travelled in their boat and in their friends' boats around Alberta, British Columbia, Montana, the Caribbean and Mexico.

They slowly learned the 'ropes' (actually called lines) and began to fall in love with the sport and sense of community that exists around sailing. It was on their 10 day passage down the Baja from San Diego to Cabo that they realized maybe a live-a-board life on a sailboat was the perfect way to travel and live a life filled with off the beaten track adventures.

Realizing you're a dirtbag Thanks so much for opening my eyes to the term 'dirtbag.' I didn't really know how to label ourselves before I met you both! haha.

We realize this life is not for everyone, and living differently than the masses can seem either exhilarating or crazy depending on who you talk to. Steve and I live a pretty low-key life in many ways and aren't out to prove anything by living this unique lifestyle. It is just what excites us, even though it means giving up a lot! (Like time with family and friends.)

We feel very privileged to be able to live a life of adventure and free from the traditional 9-5 jobs that so many people feel enslaved to.

To anyone who considers what we have as *Luck*, I would like to say, "You are wrong. Anyone can live this life, if you choose to. After you make that choice, it is only your own perseverance, determination and hard work that will stand in your way." Click to get the first chapter free of The Dirtbag's Guide or to buy now! Living the Dirtbag Life A bit more about our current situation...

Click to get the first chapter free of The Dirtbag's Guide or to buy now! Living the Dirtbag Life A bit more about our current situation...

In January, 2019 we bought our next boat in Sidney BC, a 36 foot NON-trailorable, real ocean worthy boat. Ally sold her house in Canmore and moved aboard for the summer of 2019!

At the time of this interview, Ally admitted that the future felt uncertain. The questions she gets from other people makes that feel even more real! How long will we sail? Will we sail up to Alaska? Will we take the boat to Mexico? Or further? Where will we go in the winter? Will we drive our van to Mexico (this is my vote )

The truth is that we don't know yet. This has been our dream for so long that we haven't had time to plan beyond the next few months. Find out what's been going on by following on You Tube at Sailing the Free Life.

More on sailing Baja Link to Justin & Loree's blog (Ally's sailing companions) including our trip down the Baja:

http://storiesofjustdreamin.blogspot.com/2016/11/san-diego-to-cabo-san-lucas.htmlhttp://storiesofjustdreamin.blogspot.com/2016/11/cabo-san-lucas-to-la-paz.html Arriving by sailboat in Cabo Are you ready to make adventure your lifestyle and create the life you want? Check out the book we wrote, The Dirtbag's Guide to Life: Eternal Truth of Hiker Trash, Ski Bums, and Vagabonds. It definitely applies to sailors!

Arriving by sailboat in Cabo Are you ready to make adventure your lifestyle and create the life you want? Check out the book we wrote, The Dirtbag's Guide to Life: Eternal Truth of Hiker Trash, Ski Bums, and Vagabonds. It definitely applies to sailors!

Listen to Ally's Baja sailing story in Episode 130 of the Boldly Went Podcast.

While you're here, can you throw a $1+ in the pot to help support this work by joining us on Patreon? Become a Patron!

If you want to learn more about what it takes to make moves similar to Ally, you'll like our book. Meet Ally Mantey, Sailor

Allyson was once a corporate-chick who realized in her early 30's that the dream to climb the corporate ladder was not for her. Despite growing up on the East-Coast of Canada, she had never sailed before.

Allyson was once a corporate-chick who realized in her early 30's that the dream to climb the corporate ladder was not for her. Despite growing up on the East-Coast of Canada, she had never sailed before.At the age of 34 she decided to buy a 26 foot trailorable sailboat, Seaweasel, with her husband Steve. In the 5 years following, they travelled in their boat and in their friends' boats around Alberta, British Columbia, Montana, the Caribbean and Mexico.

They slowly learned the 'ropes' (actually called lines) and began to fall in love with the sport and sense of community that exists around sailing. It was on their 10 day passage down the Baja from San Diego to Cabo that they realized maybe a live-a-board life on a sailboat was the perfect way to travel and live a life filled with off the beaten track adventures.

Realizing you're a dirtbag Thanks so much for opening my eyes to the term 'dirtbag.' I didn't really know how to label ourselves before I met you both! haha.

We realize this life is not for everyone, and living differently than the masses can seem either exhilarating or crazy depending on who you talk to. Steve and I live a pretty low-key life in many ways and aren't out to prove anything by living this unique lifestyle. It is just what excites us, even though it means giving up a lot! (Like time with family and friends.)

We feel very privileged to be able to live a life of adventure and free from the traditional 9-5 jobs that so many people feel enslaved to.

To anyone who considers what we have as *Luck*, I would like to say, "You are wrong. Anyone can live this life, if you choose to. After you make that choice, it is only your own perseverance, determination and hard work that will stand in your way."

Click to get the first chapter free of The Dirtbag's Guide or to buy now! Living the Dirtbag Life A bit more about our current situation...

Click to get the first chapter free of The Dirtbag's Guide or to buy now! Living the Dirtbag Life A bit more about our current situation...In January, 2019 we bought our next boat in Sidney BC, a 36 foot NON-trailorable, real ocean worthy boat. Ally sold her house in Canmore and moved aboard for the summer of 2019!

At the time of this interview, Ally admitted that the future felt uncertain. The questions she gets from other people makes that feel even more real! How long will we sail? Will we sail up to Alaska? Will we take the boat to Mexico? Or further? Where will we go in the winter? Will we drive our van to Mexico (this is my vote )

The truth is that we don't know yet. This has been our dream for so long that we haven't had time to plan beyond the next few months. Find out what's been going on by following on You Tube at Sailing the Free Life.

More on sailing Baja Link to Justin & Loree's blog (Ally's sailing companions) including our trip down the Baja:

http://storiesofjustdreamin.blogspot.com/2016/11/san-diego-to-cabo-san-lucas.htmlhttp://storiesofjustdreamin.blogspot.com/2016/11/cabo-san-lucas-to-la-paz.html

Arriving by sailboat in Cabo Are you ready to make adventure your lifestyle and create the life you want? Check out the book we wrote, The Dirtbag's Guide to Life: Eternal Truth of Hiker Trash, Ski Bums, and Vagabonds. It definitely applies to sailors!

Arriving by sailboat in Cabo Are you ready to make adventure your lifestyle and create the life you want? Check out the book we wrote, The Dirtbag's Guide to Life: Eternal Truth of Hiker Trash, Ski Bums, and Vagabonds. It definitely applies to sailors! Listen to Ally's Baja sailing story in Episode 130 of the Boldly Went Podcast.

While you're here, can you throw a $1+ in the pot to help support this work by joining us on Patreon? Become a Patron!

Published on January 12, 2020 15:30

January 10, 2020

Jesse Blough and the Silk Road Mountain Bike Race in Kyrgystan

Jesse Blough (Pronounced like: “blau,” he says), is an ultra-endurance cyclist, ultra runner, and creator of NW Competitive. Jesse recently announced he'll be directing a hardcore, self-supported mountain biking race called The Big Lonely. It will take you on a tour of the land of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs which many of you know as the land where Bend, OR is situated.

Jesse Blough (Pronounced like: “blau,” he says), is an ultra-endurance cyclist, ultra runner, and creator of NW Competitive. Jesse recently announced he'll be directing a hardcore, self-supported mountain biking race called The Big Lonely. It will take you on a tour of the land of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs which many of you know as the land where Bend, OR is situated.He shared his experience biking the world's toughest mountain race in Kyrgystan after breaking his leg in 3 places and having a rod nailed through the femur to hold it together in Episode 130 "Comebacks." Go there next and listen!

Jesse shared so many really interesting details about his trip and what it takes to pack a bike all the way to Kyrgystan, and we're sharing those with you below. About Kyrgyzstan Interesting stuff that Jesse shared with us about his experience going to The Silk Road Mountain Race in Kyrgyzstan that we really wanted to share with you!Kyrgyzstan is a former Soviet republic.Outside of the cities, people still live nomadically, bringing livestock (horses and sheep) to the high mountains and living in yurt camps during summer, and retreating to lower elevations in the harsh winters.Kyrgystan is crazy cheap. Central Asia is generally a very affordable place to travel, but Kyrgyzstan was way more affordable than we expected.The food is awesome, but most of the meat is either sheep or horse, and almost everyone I met who had traveled to Kyrgyzstan spent at least part of their trip with food poisoning. My favorite meal was Ashlan-Fu, which is a cold vinegar soup with two kinds of noodles, served with fried potato bread. It cost 40 cents.

Jesse's trip Logistics: 30+ hours of planes. Jesse and his wife went PDX>NYC>Moscow>Bishkek.

Jesse's trip Logistics: 30+ hours of planes. Jesse and his wife went PDX>NYC>Moscow>Bishkek. Bike gets partially disassembled and packed tightly in a bike bag (evoc travel bag pro) with all gear.

It was nerve-wracking to hope that my bike would make it safely to the tiny airport in Kyrgyzstan, along with everything else you need to survive for the duration of the race (bivy, sleeping bag, clothing, food). I was so nervous that the luggage handlers would just throw my bike around — a bike that I spent thousands of dollars and most of a year building to be the best possible machine for the race - and break it. I remember watching out of the window of the plane in Istanbul to see if my bike made it from one plane to the other. Fortunately mine did, but a few participants in the race weren’t so lucky. World Nomad Games Jesse and his wife attended the World Nomad Games in Cholpon Ata — a nomadic peoples’ Olympics — after the race. There’s acrobatic archery, dozens of forms of wrestling, horse racing, falconry, and a variety of other sports. Kok-Boru was the highlight (according to Jesse), where teams on horseback play polo with a freshly slaughtered headless goat carcass. Blood everywhere. (eeeeewwwwwww!)

Published on January 10, 2020 15:34

November 12, 2019

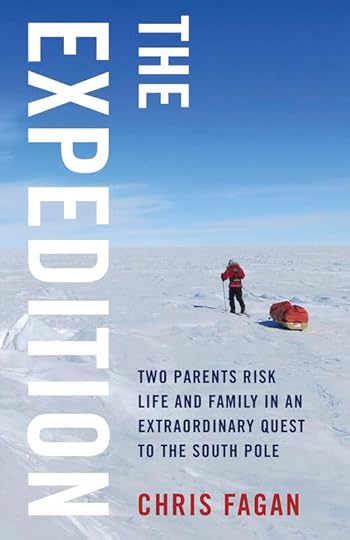

Book review: "The Expedition" by Chris Fagan

The Expedition: Two Parents Risk Life and Family in an Extraordinary Quest to the South Pole

, by Chris Fagan, September 2019, 272 pages, published by She Writes Press  Through Boldly Went, travel, trail running and hiking we've gotten to know a lot of remarkable people, but Chris and Marty Fagan are definitely some of the most impressive. We met Chris originally through the trail running community in the Seattle area, and since the Fagans have shared at one of our original Boldly Went proto-events - "Grit and Grace", been featured on our podcast about the 2019 Race to Alaska, and most recently shared a story live at one of our Tacoma events.

Through Boldly Went, travel, trail running and hiking we've gotten to know a lot of remarkable people, but Chris and Marty Fagan are definitely some of the most impressive. We met Chris originally through the trail running community in the Seattle area, and since the Fagans have shared at one of our original Boldly Went proto-events - "Grit and Grace", been featured on our podcast about the 2019 Race to Alaska, and most recently shared a story live at one of our Tacoma events.

Chris recently completed a book called "The Expedition" about maybe their biggest adventure - when she and her husband Marty became the first American married couple to ski unsupported and unguided to the South Pole. If you like Boldly Went, I'm confident you're going to like this book. In November 2013, Chris and Marty Fagan were dropped off on an ice shelf on the edge of Antarctica, put on their skis, and spent 48 days dragging themselves and all of their supplies across 500 miles of ice and snow to the South Pole, becoming the first American married couple to have done so without a guide or support. Her book, "The Expedition," is a well-written and well-paced chronicle of that experience that starts in the beginning - from the time she and Marty first met while climbing Denali in treacherous conditions, through their subsequent marriage and adventure life together in the ultra-running and mountaineering worlds, on to this specific quest itself.

The description of the 48 days they spent in Antarctica is an enjoyable and interesting read, and does a great job of describing the challenges of just existing in Antarctica - how do you take a leak when you'll get frostbite on any exposed skin in minutes, for instance, and how do you manage if you can't wash clothes or shower on an almost two month adventure? It also does a great job of describing the physical and psychological challenges associated with 48 straight 8 - 10 hour days of maximum effort in an unforgiving environment where there are literally no other people (or any other kind of mammal, for that matter) for hundreds of miles. Chris captures some of the small moments along the way - their first Ramen meal on the ice, struggles with dealing with navigation in white out conditions, managing early signs of frost bite - in a way that brings you into the experience in a relatable way. The most striking physical challenge beyond the expected cold and isolation were the miles of "sastrugi" that they had to contend with - imagine trying to cross country ski over frozen waves of varying heights - from speed bumps to rollers taller than they were.

Reading about the physical challenges of the adventure was interesting, but for me what sets this book apart as one to pick up when there are hundreds of adventure chronicles out there is the perspective that Chris gives into what this experience was like for her as a mother and a member of a family.

The book spends a lot of time on the lead up to the expedition, so readers get the sense of how big this thing actually was. Chris and Marty spent a small mortgage worth of personal money on the expedition, and devoted their life to it for several years. They focused their physical energy on it, Marty left a long time job, and you get the sense that their entire community was involved in the expedition in some way or another. While they were in Antarctica for under two months, everything in their life had to center on preparations for the year prior.

Chris doesn't necessarily play up the fact that this is a book about adventure from a wife and mother's perspective, but it is, and that's one of the things that makes it particularly interesting. The husband-wife dynamic day after day on the ice and in the tent is interesting, and navigating life and death and exhaustion of every type with a spouse was a big theme in the book. There were anecdotes in the lead up to the trip about family and friends who questioned their responsibility as parents leaving a child behind to risk their lives on something like this, and as someone who loves big travel and outdoor adventures, that was relatable.

Chris wrestles with those types of questions extensively as a theme throughout the book, and to me the most intriguing moments were when she wrote about how the trip was impacting her relationship with her son Keenan - in both challenging and inspiring ways. The most striking moment in the whole book, in my opinion, was when Chris shared a letter she wrote to Keenan to be given to him if she didn't come back - essentially a goodbye letter on the occasion of her death. The letter brought the seriousness of the experience into focus, and her reflection on the experience of writing the letter produced, to me, the most memorable quote in the book:

“My conversation with death prepared me to live.”

One of the big takeaways of an adventure like this one is that we're all mortal, and it's only when we come to terms with death that we can put our lives in their proper context - whether or not we're choosing the risks we take consciously.

In the end the book flips the script on the narrative that adventure is selfish. I don't want to reveal too much about one of the central tensions in the book, but I don't think it's too much of a spoiler to say that in the end, as a reader I felt that the positives for their family in the experience far outweighed the negatives.

Taken as a whole, the book does a great job of showing how optimism, planning, sheer toughness, commitment, and a little bit of a “haters gonna hate” attitude got Chris and Marty through not just Antarctica but the social and emotional challenges that come along with a big, scary expedition. It's a book that's satisfying as a chronicle of a massive, record setting expedition, but in the bigger picture was a great read because it dealt in interesting ways with social and relational issues that often are only peripheral in adventure literature.

If you want to buy the book, predictably enough, it's for sale on Amazon, but also look out for it at REI stores and other purveyors of fine adventure literature. And if you're a fan of adventure and reading, pick up a copy of our book, The Dirtbag's Guide to Life: Eternal Truth for Hiker Trash, Ski Bums, and Vagabonds.

Through Boldly Went, travel, trail running and hiking we've gotten to know a lot of remarkable people, but Chris and Marty Fagan are definitely some of the most impressive. We met Chris originally through the trail running community in the Seattle area, and since the Fagans have shared at one of our original Boldly Went proto-events - "Grit and Grace", been featured on our podcast about the 2019 Race to Alaska, and most recently shared a story live at one of our Tacoma events.

Through Boldly Went, travel, trail running and hiking we've gotten to know a lot of remarkable people, but Chris and Marty Fagan are definitely some of the most impressive. We met Chris originally through the trail running community in the Seattle area, and since the Fagans have shared at one of our original Boldly Went proto-events - "Grit and Grace", been featured on our podcast about the 2019 Race to Alaska, and most recently shared a story live at one of our Tacoma events.Chris recently completed a book called "The Expedition" about maybe their biggest adventure - when she and her husband Marty became the first American married couple to ski unsupported and unguided to the South Pole. If you like Boldly Went, I'm confident you're going to like this book. In November 2013, Chris and Marty Fagan were dropped off on an ice shelf on the edge of Antarctica, put on their skis, and spent 48 days dragging themselves and all of their supplies across 500 miles of ice and snow to the South Pole, becoming the first American married couple to have done so without a guide or support. Her book, "The Expedition," is a well-written and well-paced chronicle of that experience that starts in the beginning - from the time she and Marty first met while climbing Denali in treacherous conditions, through their subsequent marriage and adventure life together in the ultra-running and mountaineering worlds, on to this specific quest itself.

The description of the 48 days they spent in Antarctica is an enjoyable and interesting read, and does a great job of describing the challenges of just existing in Antarctica - how do you take a leak when you'll get frostbite on any exposed skin in minutes, for instance, and how do you manage if you can't wash clothes or shower on an almost two month adventure? It also does a great job of describing the physical and psychological challenges associated with 48 straight 8 - 10 hour days of maximum effort in an unforgiving environment where there are literally no other people (or any other kind of mammal, for that matter) for hundreds of miles. Chris captures some of the small moments along the way - their first Ramen meal on the ice, struggles with dealing with navigation in white out conditions, managing early signs of frost bite - in a way that brings you into the experience in a relatable way. The most striking physical challenge beyond the expected cold and isolation were the miles of "sastrugi" that they had to contend with - imagine trying to cross country ski over frozen waves of varying heights - from speed bumps to rollers taller than they were.

Reading about the physical challenges of the adventure was interesting, but for me what sets this book apart as one to pick up when there are hundreds of adventure chronicles out there is the perspective that Chris gives into what this experience was like for her as a mother and a member of a family.

The book spends a lot of time on the lead up to the expedition, so readers get the sense of how big this thing actually was. Chris and Marty spent a small mortgage worth of personal money on the expedition, and devoted their life to it for several years. They focused their physical energy on it, Marty left a long time job, and you get the sense that their entire community was involved in the expedition in some way or another. While they were in Antarctica for under two months, everything in their life had to center on preparations for the year prior.

Chris doesn't necessarily play up the fact that this is a book about adventure from a wife and mother's perspective, but it is, and that's one of the things that makes it particularly interesting. The husband-wife dynamic day after day on the ice and in the tent is interesting, and navigating life and death and exhaustion of every type with a spouse was a big theme in the book. There were anecdotes in the lead up to the trip about family and friends who questioned their responsibility as parents leaving a child behind to risk their lives on something like this, and as someone who loves big travel and outdoor adventures, that was relatable.

Chris wrestles with those types of questions extensively as a theme throughout the book, and to me the most intriguing moments were when she wrote about how the trip was impacting her relationship with her son Keenan - in both challenging and inspiring ways. The most striking moment in the whole book, in my opinion, was when Chris shared a letter she wrote to Keenan to be given to him if she didn't come back - essentially a goodbye letter on the occasion of her death. The letter brought the seriousness of the experience into focus, and her reflection on the experience of writing the letter produced, to me, the most memorable quote in the book:

“My conversation with death prepared me to live.”

One of the big takeaways of an adventure like this one is that we're all mortal, and it's only when we come to terms with death that we can put our lives in their proper context - whether or not we're choosing the risks we take consciously.

In the end the book flips the script on the narrative that adventure is selfish. I don't want to reveal too much about one of the central tensions in the book, but I don't think it's too much of a spoiler to say that in the end, as a reader I felt that the positives for their family in the experience far outweighed the negatives.

Taken as a whole, the book does a great job of showing how optimism, planning, sheer toughness, commitment, and a little bit of a “haters gonna hate” attitude got Chris and Marty through not just Antarctica but the social and emotional challenges that come along with a big, scary expedition. It's a book that's satisfying as a chronicle of a massive, record setting expedition, but in the bigger picture was a great read because it dealt in interesting ways with social and relational issues that often are only peripheral in adventure literature.

If you want to buy the book, predictably enough, it's for sale on Amazon, but also look out for it at REI stores and other purveyors of fine adventure literature. And if you're a fan of adventure and reading, pick up a copy of our book, The Dirtbag's Guide to Life: Eternal Truth for Hiker Trash, Ski Bums, and Vagabonds.

Published on November 12, 2019 14:30

November 10, 2019

Moab 240: A Defining Moment by Wes Ritner

Early in the race, before the problems began. All photos by Scott Rokis, Howie Stern, Hilary Matheson. Wes Ritner is an accomplished ultra runner who won the 2018 Bigfoot 200 and tied for 2nd in the 2018 Moab 240, and he's shared several stories from his 200 mile experiences with Boldly Went. He's also a West Point grad and a veteran, and this Veteran's Day we're excited to highlight some of the cool things vets are doing in the adventure community by sharing this moving story from his experience during the 2019 Moab 240. On October 14, I completed the Moab 240, a 240-mile running race near Moab, Utah involving 115 runners from 15 different countries. The course was a single loop that took the runners across vast deserts and atop 10,000-foot mountains. This was my eighth 200+ mile race since 2015, and it was arguably my worst performance in any of them.

Early in the race, before the problems began. All photos by Scott Rokis, Howie Stern, Hilary Matheson. Wes Ritner is an accomplished ultra runner who won the 2018 Bigfoot 200 and tied for 2nd in the 2018 Moab 240, and he's shared several stories from his 200 mile experiences with Boldly Went. He's also a West Point grad and a veteran, and this Veteran's Day we're excited to highlight some of the cool things vets are doing in the adventure community by sharing this moving story from his experience during the 2019 Moab 240. On October 14, I completed the Moab 240, a 240-mile running race near Moab, Utah involving 115 runners from 15 different countries. The course was a single loop that took the runners across vast deserts and atop 10,000-foot mountains. This was my eighth 200+ mile race since 2015, and it was arguably my worst performance in any of them.Initially, I thought I’d write a more thorough, traditional narrative of the race, like I’ve done for some of my other events. But since this race had been different for me, I decided to write a different kind of recap, one that focused solely on what became, for me, the defining moment of the race. Everything else during those countless hours on the trail was either a precursor to that moment or a result of the decision made in that same moment.

The first 20 miles of the race went well. I cruised along somewhere around 9th place at an easy pace, and I chatted with the other runners nearby. The early miles of most ultramarathons are like this. The pack hasn’t completely fragmented into front-runners, mid-packers and back-of-the-packers, so everyone takes advantage of having friendly company around them to take their minds off the long trail ahead.

It was somewhere around mile 25 that I started having difficulty getting calories and fluids in without feeling queasy. The problem might have been caused by the fact that my body hadn’t fully recovered from running another 200-mile race three weeks earlier, in addition to the slowly rising temperatures and the relentless exposure to the sun in the treeless, desert environment. Regardless, the temporary inability to absorb nutrients wasn’t new to me. I’d faced similar problems many times before. In such situations, I typically forced myself to eat more or drink more or to take fewer electrolyte tablets…whatever I needed to do to solve the problem. It was odd that it was hitting me so early in the race, but I figured this would pass in 10 or 20 miles, as it typically had before. When I arrived at the mile-32 aid station I made a point of taking the time to eat something other than the snacks and fruit I’d been consuming on the trail, and to drink plenty of fluids. I left that aid station thinking I would soon be feeling better.

But nothing changed. In fact, it gradually became more difficult to eat, drink, or run without feeling nauseous. I attempted to make adjustments to my diet but, strangely, nothing was working. Soon I realized that there was a good chance I would not turn this around for a long time. A very long time. It was unlikely I would even come close to hitting the most modest of my goals for the race. I would be suffering for another 205 miles to achieve a result that I wouldn’t be proud of.

With my body chemically out of balance—fluids, electrolytes and calories out of synch—the core of my thought processes was impacted. Normally, I consider myself a very driven, positive, goal-oriented person. But my mind had reacted to the imbalance by going in a very different direction. I saw only barriers and roadblocks. I saw no meaningful path through the pain. I could only see that the results I wanted to achieve in this race were impossible, and that the amount of time which I would be suffering to achieve mediocre results was going to be much longer than I’d planned. I could find no reason to continue trying.

The next aid station, positioned at mile 57 of the race, was still another 10 miles away.

I wanted to give up. Why should I continue suffering? This was just a silly race, after all. I wasn’t saving lives here. I wasn’t feeding the homeless or rescuing the helpless. I was running through the desert and having a miserable time of it. There was no reason to keep pushing forward. Such was my mindset as I slowly knocked off the next few miles. Dropping from the race at the next aid station started looking like the only reasonable action to take. Why should I suffer when there was no purpose to the suffering?

But a shred of the person who is the best of me remained engaged in the moment despite the pain. And that shred remained engaged even though I knew how bad 190 more miles of this pain could be. I knew that if I didn’t change the nature of the thoughts going through my mind, I would arrive at the next aid station and announce that I was dropping. I at least wanted to leave the door open to the possibility of a different outcome. And to do that, I needed to somehow step back from what I was going through, and evaluate why I was running this race. I needed to decide what the race really meant to me. I knew I might make the decision to drop anyway, but, if I didn’t try to change something in my mind, then my path was already decided and it was the path to dropping out.

So I did something different. I stopped running. I stepped to the side and I sat down at the edge of the trail. Runners passed by, and they asked if I was okay. I told most of them I was doing fine, of course, which was a lie. I forced myself to nibble on some of the food in my pack, and I forced myself to take small sips of water. I forced myself to take my time and allow the race to continue without me. Once I felt at peace with what I was doing, I tipped over to my side in the rocky soil, and I closed my eyes. Rocks probably jutted into my shoulder, but I didn’t feel them. I lay there silently.

Last year I’d finished this race in a little over 62 hours in a tie for second place. Based upon how it was going, I couldn’t imagine finishing it in less than 90 hours this year. I thought again about the fact that this truly was just another silly race, just like every other race out there. It was artificially constructed adversity. I knew I’d feel great if the misery ended early and abruptly at the next aid station. And I knew that I would feel a tremendous sense of relief at having avoided 190 more miles of needless, voluntary suffering.

But I also knew that such relief would quickly turn to disappointment. Disappointment in my unwillingness to finish something I’d started. Disappointment in taking the easy path of escape instead of facing the demons that I knew were still to come. This race was a task I’d chosen. It was mine to finish. Was I here to feel the fleeting success of being a top finisher at the end of the race? Was I here to hit some arbitrary finishing time goal? Granted, I enjoyed the sense of accomplishment of a strong finishing position. But that wasn’t why I’d started running these races, and it wasn’t why I continued running them. I was here to face a tough mental and physical challenge and to overcome it. To quit merely because the race wasn’t going as well as I wanted it to ran contrary to who I am.

And that was enough.

I pushed myself back into a sitting position. Where I finished in the pack of runners no longer mattered to me. I could be first or I could be last. I might suffer through nausea for the next 190 miles or I might come out of it in 20 miles…either way I was going to conquer this thing. This race would not beat me.

I started moving again, walking first, then transitioning to a slow jog. The finish line was a few steps closer.

Porcupine Rim aid station. Fueling up before the final, 16-mile push. My inability to eat and drink without feeling nauseous continued until mile 120, a total of about 90 miles of sickness. During this time, my running was essentially a slow jog, and when I was at aid stations I sat for as many as three hours trying to get food to stay in my belly, vomiting, and then starting the cycle again so I could leave the station with at least some small amount of calories in my stomach. Never in my race experience had these kinds of problems gone on for so long.

Porcupine Rim aid station. Fueling up before the final, 16-mile push. My inability to eat and drink without feeling nauseous continued until mile 120, a total of about 90 miles of sickness. During this time, my running was essentially a slow jog, and when I was at aid stations I sat for as many as three hours trying to get food to stay in my belly, vomiting, and then starting the cycle again so I could leave the station with at least some small amount of calories in my stomach. Never in my race experience had these kinds of problems gone on for so long.I seemed to finally turn a corner standing atop Shay Mountain at the mile 121 aid station. I was able to consume several cups of tomato soup, and it felt amazing to feel those calories flooding my veins. This trend continued when I hit Dry Valley at mile 140: more food and more energy. And from there things only got better. I’d dropped to 50th place when I was going through the worst of it, but after my turnaround at Shay Mountain, I progressed slowly up the field until I was running alongside Ryan Fecteau about twelve miles from the finish.

Some part of the competitive side of me reared its head as I pulled up beside Ryan….the part that wanted me to push harder and improve my meaningless statistics. But the part of me that had made a single decision in a long moment of despair almost 200 miles ago reminded me what this race was about. It was about overcoming adversity. And it was about overcoming that adversity whether it was alone or with others. Today, it would be with others. Ryan and I hiked and ran those last twelve miles, getting to know each other and appreciating each other’s stories.

We stopped just short of the finish line in a gesture of non-competitiveness, playing rock-paper-scissors to see who would cross the finish line first. It took three rounds, but, in the end, Ryan was victorious. His rock crushed my scissors. He raised his arms and crossed the line in 10th place. I followed a few seconds later in 11th. We’d finished in 80 hours and 48 minutes….more than 18 hours later than my 2018 finish. Somehow, that didn’t matter.

Looking back at the race, I attribute my finish to the moment when I realized that the morass of negativity that had drowned my mind was a result of external conditions and was not indicative of who I was. I attribute my finish to that same moment when I decided to just stop, when I decided to do something different, and when I decided to realign my thoughts with the person I knew myself to be. It was at that moment that victory became possible once again. Victory, not over other competitors, but over the obstacles that were preventing me from finishing what I knew I could finish.

Running a 240-mile race was a small price to pay for the opportunity to experience that single moment. I will gladly pay it again.

Crossing the finish line. If you like reading about adventure, or probably more importantly actually going on adventures, we're confident that you'll like our guide to developing the life you want, The Dirtbag's Guide to Life: Eternal Truth for Hiker Trash, Ski Bums, and Vagabonds.

Crossing the finish line. If you like reading about adventure, or probably more importantly actually going on adventures, we're confident that you'll like our guide to developing the life you want, The Dirtbag's Guide to Life: Eternal Truth for Hiker Trash, Ski Bums, and Vagabonds.

Published on November 10, 2019 05:56

November 6, 2019

Dirtbagging the Canadian Rockies: Cheap Trips, Expensive Places Part 3

I haven't seen all the mountains, but of the ones I have, the Canadian Rockies are solidly in the top 3 ranges for spectacular-ness (with New Zealand's Southern Alps and Patagonia, if you're wondering). They are so freaking pretty - a seemingly endless sea of hanging glaciers and turquoise lakes and snow capped peaks. To me, the Canadian Rockies look like what I imagined mountains would look like as a kid growing up among the corn fields of Ohio.

I haven't seen all the mountains, but of the ones I have, the Canadian Rockies are solidly in the top 3 ranges for spectacular-ness (with New Zealand's Southern Alps and Patagonia, if you're wondering). They are so freaking pretty - a seemingly endless sea of hanging glaciers and turquoise lakes and snow capped peaks. To me, the Canadian Rockies look like what I imagined mountains would look like as a kid growing up among the corn fields of Ohio. They also are no secret. Visit during the relatively short summer and at the most popular spots you'll be joined by tens of thousands of others, to the point that parking and road infrastructure in Banff and Jasper is swamped beyond its ability to cope. An average hotel room in the Banff/Jasper corridor can easily cost $300 per night, and national park camp sites get booked up months in advance. It's an easy place to have your experience destroyed by the crowds and cost of travel.

Thankfully though, those types of crowds and costs are for less savvy travelers than yourselves, and you can absolutely figure out how to hang out in the Rockies during the high season without breaking the bank, and even find some solitude. I know, because we just did.

Our route, more or less. We traveled it in a clockwise fashion. Finding ourselves without a place to stay for the month of August, this year Angel and I decided to fulfill a long-time ambition by spending a big hunk of summer in the Rockies. Being the people we are, we did almost zero pre-planning, threw our kayaks and tent in the Element, and figured things out as we went. In the end our experience took the form of an extended road trip loop punctuated by multiple kayaking and hiking excursions, with a few town days, some wine tasting, and a few too many brewery stops. We spent a week in Canmore to do some work online, but mostly we slept outside in either provincial or national parks.

Our route, more or less. We traveled it in a clockwise fashion. Finding ourselves without a place to stay for the month of August, this year Angel and I decided to fulfill a long-time ambition by spending a big hunk of summer in the Rockies. Being the people we are, we did almost zero pre-planning, threw our kayaks and tent in the Element, and figured things out as we went. In the end our experience took the form of an extended road trip loop punctuated by multiple kayaking and hiking excursions, with a few town days, some wine tasting, and a few too many brewery stops. We spent a week in Canmore to do some work online, but mostly we slept outside in either provincial or national parks. For some rough logistics, we started our trip in Tacoma, WA, drove north through Vancouver (to meet up with a friend), then up through Whistler and Pemberton. We drove to Bowron Lakes Provincial Park on the western edge of the Rockies, then drove east to Mt Robson Provincial Park, south through Jasper and Banff, crashed in Canmore, went south to Peter Lougheed Provincial Park, west to Yoho, Glacier, and Mt Revelstoke National Parks, then south through Kelowna and Penticton before heading back through Eastern Washington to home.

I haven't done exact calculations, but I just scrolled back through our accounts and we spent less than $3000 for the month. That's not nothing, but to me it's pretty darn good for two people to have seen all that we saw. It was definitely worth it for a month-long bucket list trip.

Here's what we learned that you should know. This might be a little bit "what I did on my summer vacation"-ish, but I'm writing with the intention of helping you do the same. First, 9 general rules... The Canadian Rockies are HUGE. They stretch roughly from the US border 1000 miles north to Northern BC/Alberta, and from east to west something like 400 miles. The plains are to their east, but to their west, north and south the Canadian Rockies are surrounded by more mountain ranges. Some of the southern portion of the Rockies is over-touristed, but if you want wilderness, you can surely find it. Our trip was almost entirely in the most heavily visited parts of the range, during one of the busiest months, and while it felt overwhelmingly busy in the tourist centers at times, even then it wasn't a huge task to get away from the crowds.In related business, there are lots of national and provincial parks in the Canadian Rockies, and generally speaking the provincial parks are a bit less busy than the national parks, with the exception of Mt Robson Provincial Park, which felt just as busy as Jasper, and Mt Revelstoke National Park, which felt generally less busy than any other park we visited. If you're flying in, I'd recommend Calgary over Edmonton. It's closer to the Rockies, and a generally more likable city, in my opinion.If your primary experience of the Canadian Rockies is the drive between Banff and Jasper on the Icefields Parkway, it will all feel gross and overrun and exorbitantly expensive. It's genuinely stunning here, and it's worth the trip, but try not to make this your primary experience of the Canadian Rockies, if you have a choice.No matter where you go, an hour or two of effort (hiking, biking, paddling, climbing) will reliably get you away from the worst of the crowds, as will an hour or two of rain.Free car camping on public land is widespread outside of the parks. Paid car camping can be competitive to find inside the parks but isn't ridiculously expensive. There are no real budget options to sleep in a hotel anywhere in the parks, but plenty on the periphery of the parks. Before you go, download the iOverlander App. It's the best resource for finding camping, boondocking and other types of cheap road trip accommodation and services.Even for hike- or paddle-in sites, received wisdom is that everything in the southern Rockies books up months in advance and you won't be able to do what you want in the summer if you haven't planned ahead. But what we found is that if you're a little bit flexible you can find stuff to do and places to camp on the day of pretty much anywhere, even in Banff and Jasper. My theory - the further in advance people feel they have to book, the more likely they are to cancel their reservations when the time comes. Which means lots of things open up last minute....so don't be afraid to just show up and ask at the park office if you want to do something. You might not get exactly what you want (but then again you might - we did, in every case), but because literally everything is awesome there, you'll get something cool. The provincial parks are just as spectacular as the national parks. My three favorite trips from the month were all in provincial parks - Bowron Lakes, Mt Robson, and Peter Lougheed. The national parks are incredible, but so is everything else. ...and now the specifics. While I can't give you a full Canadian Rockies guidebook, I can give you a decent introduction by talking about the places we went and the stuff we did. After spending a bit of time before the trip looking at the options of awesome places to spend a month, they're the areas we settled on, as well as a couple of surprise gems that we found along the way. These are the things we learned, a few crucial hot tips, and some photos of pretty places.

Bowron Lakes While it wasn't the most spectacular mountain scenery we saw, paddling a portion of the Bowron Lakes Circuit was maybe my personal favorite part of the whole month - it was relaxing, beautiful, and felt like a real wilderness experience. For a short orientation, the Bowron Lakes are a 116 km (or 72 mile) chain of lakes and streams that, unusually, form a square shaped circuit that hundreds of hearty Canadians visit time and time again to canoe or kayak, usually across about a week, during the nice parts of summer. The circuit is frequently compared to the Boundary Waters in Minnesota, but with mountains. I can confirm that it's SO nice - remote, beautiful, peaceful, the very picture of idyllic wilderness lake paddling despite the fact that it's a popular destination.

Bowron Lakes While it wasn't the most spectacular mountain scenery we saw, paddling a portion of the Bowron Lakes Circuit was maybe my personal favorite part of the whole month - it was relaxing, beautiful, and felt like a real wilderness experience. For a short orientation, the Bowron Lakes are a 116 km (or 72 mile) chain of lakes and streams that, unusually, form a square shaped circuit that hundreds of hearty Canadians visit time and time again to canoe or kayak, usually across about a week, during the nice parts of summer. The circuit is frequently compared to the Boundary Waters in Minnesota, but with mountains. I can confirm that it's SO nice - remote, beautiful, peaceful, the very picture of idyllic wilderness lake paddling despite the fact that it's a popular destination. You can take trips of theoretically any length in the park, from day trips up to the full circuit, but because of the flow of the lakes and the system of permitting, most people either do the full circuit, or an out and back on the Western side of the circuit. We were worried we couldn't fit the whole thing in, and we were in folding kayaks so not the best tool for the job, so we spent four days doing the Western circuit. In retrospect, it probably would have been possible to fit the whole thing in, but we still loved it.

Key things to know if you want to take a stunning multi-day paddling excursion in the Bowron Lakes surrounded by moose and bear and idyllic scenery, which you might not find on the website.Conventional wisdom is that you should plan way ahead for this trip, as it books out up to a year in advance for the best portion of the season. Our wisdom: in those sorts of scenarios, same day availability is pretty darn likely because when you plan something a year in advance, things change and people cancel. We showed up and were able to get permitting for the next day, even on the tail end of a holiday weekend in August. No guarantees, but if you're a lazy planner, don't immediately write this off just because received wisdom is that permits are always booked up months in advance - especially if you have your own boats and some flexibility. There's a provincial park campground right at the start of the circuit, and the story's the same - conventional wisdom is that it's frequently full in summer, but we found a site day of, arriving early in the day. There are in fact lots of mosquitos, and that impacts your experience, but hey, you're here to paddle, not hang out in camp. Other wildlife - also abundant. We saw 5 moose and a black bear swimming across a lake. It was magical.Buy your supplies way before you get anywhere close to the Provincial Park. This place takes a long time to drive to, and the closer you get the smaller towns are, and the more expensive groceries get. Coming from the West side, we'd recommend stocking up in Quesnel (which is hours away) if you want anything like affordable groceries. Wells is a reasonable distance from the park and has a small grocery, but choice is extremely limited and prices are a little bit silly. There are two outfitter type places at campgrounds in Bowron Lakes with limited hours, few choices, and exorbitant prices, but you can pick up basic supplies there in a pinch.The weather for us was perfect - hot even. We skinny dipped and almost never changed out of bathing suits and were on flat water the entire trip. The previous week paddlers were caught in a persistent downpour and people had to fight off hypothermia, hail, wind and waves. Anything in between is possible all season. Gird your loins.5/5 stars. Highly recommended.

Mt Robson Provincial Park Mt Robson Provincial Park is just west of Jasper National Park, and for my money was just as beautiful. We hiked the Berg Lake Trail, and I would rate it as one of the most spectacular short backpacking trips I've ever been on. It's all glaciated peaks shooting out of turquoise lakes - exactly what I picture when I picture the Canadian Rockies. There are a variety of camping options, so there are a lot of possibilities here - you can do some amazing day hikes, or stretch it out into 2 - 4 days. We spent 3 days and 2 nights, and that allowed us to have a good experience of the area - enough to get out on some side trips and away from crowds, and to not feel too stressed that one of the days was interrupted by a bit of rain. Our hot tips for this trip:Good lord it's beautiful - even if you can only get out for a day hike there, prioritize it. We saw a fair number of trail runners making an intrepid day of it - I think the full route was a 28 mile out and back that would make for one of the prettiest big days imaginable. There is some climbing, but the terrain is relatively friendly if you're a fit hiker/runner.Also, there will be other people there. It's really busy, with helicopters flying in kayakers and hikers to some of the further up shelters and campsites even. That can be obnoxious, it's true, but it's also true that we took a 10km side jaunt from the busiest point on the trail to get the view in the photo above, and we didn't see anyone else on that portion of trail. As if normally the case, if you walk a mile from the most popular spots, you'll find solitude.With the popularity, received wisdom again is to book way ahead. Again, we managed to show up at the ranger station and get permits on the same day for two nights during a decent weather window. Maybe it was luck, but the odds are in your favor, I think, for cancellations if you have some degree of flexibility and the ability to hike 10 - 15 miles to the further out camp sites. If you have time and want to do this one, don't write it off just because you haven't planned ahead.

Mt Robson Provincial Park Mt Robson Provincial Park is just west of Jasper National Park, and for my money was just as beautiful. We hiked the Berg Lake Trail, and I would rate it as one of the most spectacular short backpacking trips I've ever been on. It's all glaciated peaks shooting out of turquoise lakes - exactly what I picture when I picture the Canadian Rockies. There are a variety of camping options, so there are a lot of possibilities here - you can do some amazing day hikes, or stretch it out into 2 - 4 days. We spent 3 days and 2 nights, and that allowed us to have a good experience of the area - enough to get out on some side trips and away from crowds, and to not feel too stressed that one of the days was interrupted by a bit of rain. Our hot tips for this trip:Good lord it's beautiful - even if you can only get out for a day hike there, prioritize it. We saw a fair number of trail runners making an intrepid day of it - I think the full route was a 28 mile out and back that would make for one of the prettiest big days imaginable. There is some climbing, but the terrain is relatively friendly if you're a fit hiker/runner.Also, there will be other people there. It's really busy, with helicopters flying in kayakers and hikers to some of the further up shelters and campsites even. That can be obnoxious, it's true, but it's also true that we took a 10km side jaunt from the busiest point on the trail to get the view in the photo above, and we didn't see anyone else on that portion of trail. As if normally the case, if you walk a mile from the most popular spots, you'll find solitude.With the popularity, received wisdom again is to book way ahead. Again, we managed to show up at the ranger station and get permits on the same day for two nights during a decent weather window. Maybe it was luck, but the odds are in your favor, I think, for cancellations if you have some degree of flexibility and the ability to hike 10 - 15 miles to the further out camp sites. If you have time and want to do this one, don't write it off just because you haven't planned ahead.  Jasper/Banff Jasper and Banff are two large National Parks that interconnect and protect some of the most spectacular parts of the Canadian Rockies. They're also the belly of the beast when it comes to over-tourism in the area. You should absolutely go there, but also be prepared for what you'll find.

Jasper/Banff Jasper and Banff are two large National Parks that interconnect and protect some of the most spectacular parts of the Canadian Rockies. They're also the belly of the beast when it comes to over-tourism in the area. You should absolutely go there, but also be prepared for what you'll find.First things first, the core infrastructure of Banff/Jasper looks like two small namesake cities within the National Park with a 232 km busy tourist highway connecting them (the Icefields Parkway) and providing access to other areas of the park. These are all beautiful places, but they are also to some degree places that, if you go during the summer high season, will need to be endured as much as enjoyed. The towns of Banff and Jasper are both pleasant enough, and beautifully situated, but also good luck finding a hotel for less than $200/night or a reasonably priced meal. The Icefields Parkway is punctuated by places that you should totally visit - Bow Lake, the Columbia Icefield, Athabasca Falls, Lake Louise - but when you do be prepared to be surrounded by hoards of tourists pouring out of buses and stopping in inopportune places to take photos. Rest assured that if you hike out more than 5 km you will find relative solitude, but prepare for this crush of humanity and embrace it for what it is rather than allowing bitterness to creep in.

These NPs are highly developed and highly regulated, even more so than in most US NPs, if I can make that anecdotal assessment. Boondocking and free camping aren't really a thing, and hike in or paddle in camp sites will all be in designated spots that require getting permits. This is the only place on the entire trip where we got a little stressed about finding somewhere affordable to sleep without pre-planning, but to calm your worries we did still manage.

We've been to this area at least a half dozen times, usually in the shoulder season, and here are a few thoughts.It's amazing here all year. Late Spring and Early Fall can be great options because crowds are somewhat dispersed, but weather can be really cold even then, and snow lingers well into June/July, and can fall any time of the year, so prep for the conditions. Also some of the best skiing you will find anywhere is here, and the season is long - November to May, generally. Most is around Banff, but Jasper also has some ski areas - they're much less crowded I'm told, because Calgarians can't easily pop up for the day or weekend. It's not cheap there, but SO pretty and so many options. Summer feels the busiest - to me, to the point of unpleasantness at times.Even in our fancy-free summer visit to Jasper, it wasn't hard to find a place to stay for a few days, because they have an overflow camping site where we were told "there are always sites available". That seemed true, and it was fine, and surprisingly affordable - $10/night. That sight is on the outskirts of the park, but it wouldn't be a terrible option for a first timer who didn't plan ahead in the high season to stay there for a week and just make day trips around if you didn't want to fight for sites closer in or pay for ridiculously priced hotels. We also managed to find a next day camping permit for a paddle in site on Maligne Lake - one of the most popular spots in the park and one of the places we really wanted to go - so even in Jasper our lack of planning didn't prevent us from seeing things we wanted to see.We did almost get ourselves into a pinch by leaving late in the day from Jasper and planning to find a spot to camp between there and Banff. Lots of sites along the Icefield Parkway are first come first serve, but tip: most of the car camping sites along the way will fill earlier in the day than 9 pm. The good news is that being willing to walk 1/2 mile saved us once again, and we were able to find a site that had overflow camping in an area that you had to walk to, and there were plenty of spots available.There are a series of hostels along the Parkway that are affordable compared to other lodging options if you want to sleep inside. Moraine Lake and Lake Louise are likely the most famous sites in the area, and they're both stunning, but sadly visiting in Summer has turned into an absolute shocker of a traffic experience. (I blame Instagram.) Go for the day, hike up to the Tea Houses, but please, for the love of Pachamama, take a shuttle if you're going in high season. Things have gone too far, and wait times for parking are sometimes measured in hours.If you can't stomach that, Lake Minnewanka is a great alternative to those lakes, and a nice place to visit any time of year for a hike because it's flat and low altitude. We chose not to do any big overnight backpacking in Banff/Jasper because permitting can be a bit of a hassle and you really should plan ahead, but as with other places, if you show up and are flexible you will almost definitely be able to find somewhere stunning to go, even on day of. Really literally everywhere in these parks is incredibly beautiful.

Canmore Our standard strategy when visiting the area is to stay in Canmore. Canmore is just outside of Banff NP, East towards Calgary, and compared to the town of Banff is just as beautiful, significantly cheaper, and similarly convenient. If I had to pick one mountain town to live in anywhere in the world, it would probably be there. I freaking love it. There's just as much to do as in Banff, and you don't even have to worry about a National Parks Permit. There are also a good number of places on the outskirts where you can park and free camp without hassle (which isn't going to happen in the NPs), and even though it's heavily touristed as well, the tourists here tend to be Canadian ski bums and dirtbags rather than scenic drivers and bus passengers, so you get good breweries and a few relatively affordable groceries and bars.In Canmore, for day hikes or runs, check out Ha Ling and Mt Rundle. Grassi Lakes is cool too if you're looking for something more mellow.For free camping, head up Spray Park Road, which has options to pull off.If you visit, say hi to our friends Gavin and Joel at Ski Uphill/Run Uphill and ask them for beta on climbing, hiking, running, or skiing, or even join them on one of the group runs they organize. They're world class and run a great little shop. The beer's great at Canmore Brewing, and check out events at artsPlace - they do a ton of great mountain town kind of events - film festivals, music, guest speakers, etc.

Canmore Our standard strategy when visiting the area is to stay in Canmore. Canmore is just outside of Banff NP, East towards Calgary, and compared to the town of Banff is just as beautiful, significantly cheaper, and similarly convenient. If I had to pick one mountain town to live in anywhere in the world, it would probably be there. I freaking love it. There's just as much to do as in Banff, and you don't even have to worry about a National Parks Permit. There are also a good number of places on the outskirts where you can park and free camp without hassle (which isn't going to happen in the NPs), and even though it's heavily touristed as well, the tourists here tend to be Canadian ski bums and dirtbags rather than scenic drivers and bus passengers, so you get good breweries and a few relatively affordable groceries and bars.In Canmore, for day hikes or runs, check out Ha Ling and Mt Rundle. Grassi Lakes is cool too if you're looking for something more mellow.For free camping, head up Spray Park Road, which has options to pull off.If you visit, say hi to our friends Gavin and Joel at Ski Uphill/Run Uphill and ask them for beta on climbing, hiking, running, or skiing, or even join them on one of the group runs they organize. They're world class and run a great little shop. The beer's great at Canmore Brewing, and check out events at artsPlace - they do a ton of great mountain town kind of events - film festivals, music, guest speakers, etc.  Peter Lougheed Provincial Park Peter Lougheed Provincial Park is Southeast of Banff, and like Mt Robson and Bowron Lakes, is just as amazing, and slightly less busy than the adjacent National Parks. It's day-trippable from Canmore or Calgary, and it is also so freaking pretty with lots of options for hiking, climbing or paddling. On this trip, it's hard for me to decide whether the Berg Lake Trail or a hike we did in this park was more beautiful - the Northover Ridge Loop. Like Berg Lake, this loop could be taken on as one big day for a very strong hiker or trail runner, but the ridge is nothing to be trifled with if you have any doubts about your ability to complete 25 miles in a day with a significant amount of climbing, some exposure, and changeable weather. We enjoyed it as a one night overnight. Permitting for this park happens online, and there is no ranger station to pop in for permits (unless I'm missing something - I might be? Canadians, correct me please!) so does take a day or two of forethought.

Peter Lougheed Provincial Park Peter Lougheed Provincial Park is Southeast of Banff, and like Mt Robson and Bowron Lakes, is just as amazing, and slightly less busy than the adjacent National Parks. It's day-trippable from Canmore or Calgary, and it is also so freaking pretty with lots of options for hiking, climbing or paddling. On this trip, it's hard for me to decide whether the Berg Lake Trail or a hike we did in this park was more beautiful - the Northover Ridge Loop. Like Berg Lake, this loop could be taken on as one big day for a very strong hiker or trail runner, but the ridge is nothing to be trifled with if you have any doubts about your ability to complete 25 miles in a day with a significant amount of climbing, some exposure, and changeable weather. We enjoyed it as a one night overnight. Permitting for this park happens online, and there is no ranger station to pop in for permits (unless I'm missing something - I might be? Canadians, correct me please!) so does take a day or two of forethought.We glommed on to a friend's permit, but there were permits available even on the weekend during the Summer, so it makes another excellent option for a backpacking trip for the (mostly) poor planner or dirtbag passing through.

A thing to bear in mind is that the Northover Ridge Loop is relatively high country, so the season is short - the trail isn't really snow free until mid-July most years and snow starts falling again in September. We got snowed on in mid-August. Totally worth it though.

Yoho Yoho National Park is kind of Banff/Jasper's kid brother. It's contiguous with them, and just as pretty, but a bit smaller and less popular. The highlight (and virtual entirety) of our time in Yoho was a weekend spent volunteering with Fran Drummond at the Twin Falls Chalet, but that's a complicated story of its own. The chalet may or may not be open again in the future, and Fran may or may not be there, but if it is, and if she is, it's a highly recommended experience for the reasons that you'll pick up on if you read the article linked above.Another good place for a stop in Yoho are Emerald Lake, which is a beautiful, but very busy, spot - a sort of poor man's Lake Louise where masses of people pay $75/hour to rent canoes and try to capture great shots for Instagram. Bring your own boat and try to create the world's most beautiful photobomb for free. The Burgess Shale is a really interesting and historically important fossil site you can visit from the town of Field. I like that kind of crap so I would put visiting the site as a Yoho must-do, but I understand that most people grow out of their fossil/dinosaur stage by the time they're 8.

Yoho Yoho National Park is kind of Banff/Jasper's kid brother. It's contiguous with them, and just as pretty, but a bit smaller and less popular. The highlight (and virtual entirety) of our time in Yoho was a weekend spent volunteering with Fran Drummond at the Twin Falls Chalet, but that's a complicated story of its own. The chalet may or may not be open again in the future, and Fran may or may not be there, but if it is, and if she is, it's a highly recommended experience for the reasons that you'll pick up on if you read the article linked above.Another good place for a stop in Yoho are Emerald Lake, which is a beautiful, but very busy, spot - a sort of poor man's Lake Louise where masses of people pay $75/hour to rent canoes and try to capture great shots for Instagram. Bring your own boat and try to create the world's most beautiful photobomb for free. The Burgess Shale is a really interesting and historically important fossil site you can visit from the town of Field. I like that kind of crap so I would put visiting the site as a Yoho must-do, but I understand that most people grow out of their fossil/dinosaur stage by the time they're 8.  Glacier/Revelstoke When you cross into Glacier and Mount Revelstoke National Parks on the Trans-Canada, the mountains start to feel a bit less like the Rockies, and a bit more like the Cascades. They're both smaller, beautiful parks right along the highway where we stopped for just a day hike, and that's pretty appropriate, I think. They're both great, beautiful places, but relatively small and with fewer options for activities than the other, larger parks. They're also significantly less crowded, and free to cheap camping options exist near both. The town of Revelstoke itself is picking up in popularity as an outdoor town for a lot of really solid reasons, but it's still a relatively affordable place to base yourself. The city campground in town is a great, cheap place to post up for a few nights with wifi and laundry, right in the middle of town, and right on the Columbia River.