Stewart Brand's Blog, page 27

May 29, 2018

Overview: Earth and Civilization in Macroscope

“Once a photograph of the Earth, taken from outside, is available…a new idea as powerful as any in history will be let loose.“ — Astronomer Fred Hoyle, 01948

I. “Why Do You Look In A Mirror?”

InFebruary 01966, Stewart Brand, a month removed from launching a multimedia psychedelic festival that inaugurated the hippie counterculture, sat on the roof of his apartment in San Francisco’s North Beach, doing what he usually did when he was bored and uncertain. He took some LSD and got to scheming.

Stewart Brand and Ken Kesey, 01966. California Historical Society.

“There I sat,” Brand later recalled, “wrapped in a blanket in the chill afternoon sun, trembling with cold and inchoate emotion, gazing at the San Francisco skyline, waiting for my vision. The buildings were not parallel — because the Earth curved under them, and me, and all of us; it closed on itself. I remembered that Buckminster Fuller had been harping on this at a recent lecture — that people perceived the Earth as flat and infinite, and that that was the root of all their misbehavior. Now from my altitude of three stories and one hundred mikes, I could see that it was curved, think it, and finally feel it. But how to broadcast it?”

Scribbled in his journal entry for that day was the answer, in the form of a question: “Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole earth yet?”

Stewart Brand’s journal entry when he conceived of his “Why Haven’t We Seen A Photograph of the Whole Earth?” campaign. Stanford University Special Collections.

In the aftermath of World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union competed for nuclear dominion on Earth. With the 01957 launch of Sputnik, the contest expanded to space. But in the race to the moon, neither side had given much thought to the value of training their satellites’ apertures on the world left behind. Brand glimpsed the power such an image could hold.

Brand in the midst of his Whole Earth campaign, 01966.

“A photograph would do it — a color photograph from space of the earth,” Brand said. “There it would be for all to see, the earth complete, tiny, adrift, and no one would ever perceive things the same way.”

Brand mounted a spirited campaign selling buttons that posed the question “Why Haven’t We Seen A Photograph of the Whole Earth?” on college campuses across the country. He often showed up in costume, and he often was chucked out by security. He sent buttons to Marshall McLuhan, Buckminster Fuller, NASA officials, and members of Congress.

According to a 01966 Village Voice article, a student at Columbia asked Brand: “What would happen if we did have a picture? Would it eliminate slums, or meanness, or anything?”

“Maybe not,” said Brand, “but it might tell us something about ourselves.”

“What?” asked the girl.

“It might tell us where we’re at,” said Brand.

“What for?” asked the girl.

“Why do you look in the mirror?” asked Brand.

“Oh,” said the girl, and bought a button.

The first color photograph of the whole earth, from ATS-3 (01967).

Brand would soon get his photo. On November 10, 01967, the NASA geostationary weather and communications satellite ATS-3 captured the first color photograph of the whole earth. Brand used a reproduction of the photo for the cover of the first Whole Earth Catalog, a countercultural bible and forerunner to the World Wide Web that Steve Jobs once called “Google in paperback form.”

But the image didn’t enter the mainstream, as the first copies of The Whole Earth Catalog seldom strayed far from the communes. (That would change by 01972, when The Last Whole Earth Catalog won a National Book Award).

The moment of revelation for a global audience came in 01968, at the conclusion of a year of violence and unrest that saw the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, the escalation of war in Vietnam, and the brutal suppression of student protests across the globe.

During the Apollo 8 lunar mission on Christmas Eve, 01968, Astronauts Frank Borman, James Lovell, and Bill Anders left Earth’s orbit for the moon, traveling further than any humans before. And then they looked back.

The first time humans saw the whole earth (01968).

Anders later said the view of a fragile earth hanging suspended in the void “caught us hardened test pilots.”

“Here we came all this way to the Moon, and yet the most significant thing we’re seeing is our own home planet, the Earth. “— Astronaut Bill Anders

The descriptions of awe, connection, and transcendence Lowell, Borman and Anders said they felt that day when they looked back at Earth would be echoed by future astronauts.

“You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it. From out there on the moon, international politics look so petty. You want to grab a politician by the scruff of the neck and drag him a quarter of a million miles out and say, ‘Look at that, you son of a bitch.’” — Astronaut Edgar Mitchell

Psychologists call this cognitive shift of awareness during spaceflight the “overview effect.”

The view of Earth for TV audiences during the Apollo 8 Christmas Eve broadcast.

The Apollo 8 astronauts reached for their cameras and started snapping photos. Later that day, in what was, at that time, the most watched television broadcast in history, the astronauts read from the Book of Genesis as the cameras showed a grainy, black and white image of the Earth.

When the astronauts returned to Earth three days later, they brought with them the boon of their new whole earth perspective in the form of a photograph. Earthrise captured what the grainy television cameras could not.

“Earthrise, Seen For The First Time By Human Eyes” (01968). NASA.

“Up there, it’s a black-and-white world,” James Lovell later recalled. “There’s no color. In the whole universe, wherever we looked, the only bit of color was back on Earth…It was the most beautiful thing there was to see in all the heavens.”

Earthrise and its companion Blue Marble (01972) are among the most widely disseminated images in human history. By approximating the overview effect for the earthbound, the photos helped launch the modern environmental movement and reframed how we think about our relationship to the planet.

Blue Marble (01972).

“The sight of the whole Earth, small, alive, and alone, caused scientific and philosophical thought to shift away from the assumption that the Earth was a fixed environment, unalterably given to humankind, and towards a model of the Earth as an evolving environment, conditioned by life and alterable by human activity,” writes historian Robert Poole.² “It was the defining moment of the twentieth century.”

Be that as it may, historian Benjamin Lazier argues that by the twenty-first century, Earthrise and Blue Marble became victims of their own success.

“Views of Earth are now so ubiquitous as to go unremarked,” he writes. “These two images and their progeny now grace T-shirts and tote bags, cartoons and coffee cups, stamps commemorating Earth Day and posters feting the exploits of suicide bombers.” The whole earth’s very omnipresence means that “we ceased, in a fashion, to see it.”

Perhaps. Benjamin Grant, founder of the Daily Overview, believes we just need to look closer.

The Mount Whaleback Iron Ore Mine in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. 98% of world’s mined iron ore is used to make steel and is thus a major component in the construction of buildings, automobiles, and appliances such as refrigerators. Daily Overview.

II. An Amazing Mistake

In02013, Benjamin Grant, then a brand strategist at a buttoned-up consulting firm in New York City, found himself thinking less about marketing and more about outer space. Earlier that year, a meteor whose light shone brighter than the sun exploded into fragments across Russian skies. In September, NASA confirmed that the Voyager space probe entered interstellar space, becoming the first human-made object to leave the solar system. And SpaceX was making strides with the rockets it hoped would one day carry humans to Mars. Grant was fascinated, and decided to start a space club at work.

“It was not a normal thing for anyone at my job to start a club of any kind,” Grant says. “But I figured I would do it and if I got fired for doing it then it probably was not the right place for me to work anyway.”

Grant started giving talks at the firm, and soon became known to his colleagues as the space guy. One introduced him to a short film by Planetary Collective called Overview.

The film explored the overview effect in meditative detail and shared astronauts’ reactions to seeing the earth from space.

“It was so powerful to me, so profound,” Grant says of watching Overview. “Maybe I was searching for something like that.”

Grant began sharing the video with everyone he knew. The overview effect was very much on his mind when he started preparing for a space club talk on GPS satellites. As he was pulling some satellite imagery for the talk, he entered “Earth” into the Apple Maps search bar, hoping it would take him to a zoomed out view of the whole earth. What he saw instead stunned him: Earth, Texas, a small town in the Northern part of the state with a population of 1,048.

The screenshot Benjamin Grant took of Earth, TX, seen from above. Benjamin Grant

Viewed from above, Earth, Texas is dappled by perfect circle after circle of fields, looking not unlike a pattern of verdant vinyl records.

“I had no idea what I was seeing at the time, but I’d studied art history and was dabbling in photography,” Grant says. “This was so stunningly beautiful and I had absolutely no idea what it was. It was this amazing mistake that set me off on this adventure.”

Grant went back to his apartment, plugged his computer into his big-screen, and showed the image to his roommates. They discovered that they were looking at pivot irrigation fields. The image inspired an evening of searching for similarly arresting satellite imagery of man-made systems. A friend from Europe showed him the shipping containers of the Port of Rotterdam, Europe’s largest sea port. Another friend who worked in energy asked if Grant had ever looked at solar concentrators before. A friend’s girlfriend who worked for an NGO at the time showed them the Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya.

Top left: The Port of Rotterdam. Top right: A solar farm in Seville, Spain. Bottom: The Dadaab Refugee camp, Kenya. Daily Overview

In an epiphanous moment not unlike Stewart Brand’s whole earth vision—sans LSD—Grant realized that these seldom-considered perspectives might inspire something akin to what seeing the Earth from space did for astronauts.

He launched the Daily Overview on Instagram soon after. Each day, the account shares an image of the Earth from above, called an Overview, that is optimized to capture fleeting attention on social media. Underneath each arresting image is a bite-size caption of two to three sentences describing what you’re seeing, along with geocoordinates. Daily Overview is one of the most popular blogs on social media. On Instagram, no account with an environmental focus has more followers.

“I think we’re inundated and saturated with so much information all the time now,” Grant tells me, “that if you can focus it to a few simple things it can actually stick with someone.”

The Eixample District in Barcelona, Spain. The neighborhood is characterized by its strict grid pattern, octagonal intersections, and apartments with communal courtyards. Daily Overview.

There’s a key difference between these Overviews and the whole earth photographs of yore: Blue Marble and Earthrise showed a planet seemingly unaffected by human activity. (“Raging nationalistic interests, famines, wars, pestilences don’t show from that distance,” Apollo 8 astronaut Frank Borman said). Zooming in changes that.

What one witnesses from this vantage — intricate and vibrant patterns of human activity, construction, and destruction— is still aesthetically-pleasing. But in asking how those systems came to be, and learning about their impact, Grant hopes that one gains a planetary awareness, and, ideally, a motivation to act in a way that ensures planetary flourishing.

Ipanema Beach, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Daily Overview.

“If people have a better understanding of what is going on they’re more likely to behave in a way that serves the planet rather than serving themselves,” Grant tells me. “These images are a way to introduce things that people would never look at. If you were like, ‘I want you to look at waste ponds from this iron ore mine,’ people would say, ‘Why would I spend my time doing that?’ But if you can do that in a beautiful way that gets people engaged and gets people to ask questions about why it looks a certain way or is a certain color that’s an opportunity to educate and potentially change behaviors.”

Left: Iron Ore Mine, Tailings Pond, Negaunee, Michigan, USA. Right: Tulip fields in Lisse, Netherlands. Daily Overview

For Grant, inspiring awe with his overviews is as important as inspiring awareness.

“The things that stimulate awe, such as exposure to perceptually vast things, that you can experience if you go to the Grand Canyon or look out your airplane window, results in fascinating behaviors,” Grant says.

A 02014 study found that exposure to perceptually vast stimuli that transcend current frames of reference (i.e., awe) resulted in increased ethical decision making, generosity, and prosocial values while leading to decreased feelings of entitlement. “Awe,” the study’s authors concluded, “may help situate individuals within broader social contexts and enhance collective concern.”

Evaporation ponds at a Potash mine, Moab, Utah. The mine produces muriate of potash, a potassium-containing salt that is a major component in fertilizers. Daily Overview.

For Grant, stimulating awe with an overview comes down to not just what the satellite image portrays, but its artfulness. Each overview is stitched together out of as many as 25 images, purposefully cropped with balance and composition in mind. Many of Grant’s overviews evoke the works of Piet Mondrian, Mark Rothko, and Ellsworth Kelly.

“My favorite art is abstract expressionist painting—very simple, almost flat two dimensional painting,” Grant says. “When you look at the world from outer space it also appears flat and two dimensional.”

A juxtaposition of an Overview with a Piet Mondrian tableau. Via Benjamin Grant.

“If I can get people to experience awe,” Grant says, “not only because they’re seeing something that’s visually vast, like seeing an entire city in one frame or an entire mine in one frame, but if also I can compose it in such a way that the artistry of the image itself gets someone to feel awe, perhaps I’m being doubly as effective at getting them to think more prosocially or think beyond themselves or think of the collective.”

The first fully illuminated snapshot of the Earth captured by the DSCOVR satellite, a joint NASA, NOAA, and U.S. Air Force mission (02015).

III. A New Icon?

Grant’s notions about his overviews as art reminds me of something Stewart Brand once said when asked to elaborate on his intentions with getting NASA to release an image of the earth from space

“I saw the whole earth as an icon, mainly,” he said, “one that did indeed replace the mushroom cloud as the main image for understanding our world.”

These days, Brand’s focus has shifted to a creating a new icon for a different age, The Long Now Foundation’s Clock of the Long Now. “Ideally, it would do for thinking about time what the photographs of Earth from space have done for thinking about the environment,” Brand writes. “Such icons reframe how people think.”

Brand’s co-founder at Long Now, Brian Eno, sees both the whole earth photographs and The Clock of The Long Now as works of art that are imbued with a “mythic, metaphorical presence.”

“The 20th Century yielded its share of icons,” Eno writes. “In this, the 21st century, we may need icons more than ever before.”

Grant’s overviews present the Earth in piecemeal — fragments of a larger whole delivered to a global audience on platforms engineered for ephemerality.

When asked if he thinks it’s possible for a single image of the Earth to serve as an icon for our current age like the whole Earth photos did half a century ago, Grant says he doesn’t think so.

“I don’t know if you could unify people in that way now,” he says. “It’s certainly necessary.”

Elon Musk recently sent a Tesla roadster into space.

Nonetheless, Grant believes advances in technology and the current space revolution will make the overview effect more and more a part of our lives. Geostationary satellites with better cameras are creating new Blue Marbles. Space tourism is on the rise, with trips to Mars on the horizon. The perspective the whole earth icon points to could—for those fortunate enough to “slip the surly bonds of earth”—become a direct experience.

“The overview effect is going to become more of a thing,” Grant says. “Whether or not it’s called that, or whether or not people are experiencing it first hand…if awe is generated, regardless of how it happens, it will lead to more prosocial values and more collaboration, and that will create a better planet.”

Notes

[1] The Long Now Foundation uses five digit dates to serve as a reminder of the time scale that we endeavor to work in. Since the Clock of the Long Now is meant to run well past the Gregorian year 10,000, the extra zero is to solve the deca-millennium bug which will come into effect in about 8,000 years.

[2] Poole, Robert. Earthrise: How Man First Saw the Earth (02008), Yale University Press, 198–9.

Learn More

Watch Benjamin Grant’s Long Now talk and conversation with Stewart Brand.

Read Benjamin Grant’s book about the Daily Overview project, Overview(02016).

Read “The Overview Effect: Awe and Self-Transcendent Experience in Space Flight” in Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice (02016), Vol. 3, №1, 1–11.

Read “Awe, the Small Self, and Prosocial Behavior” in Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (02015), Vol. 108, №6, 883–899.

Read “The Man Who Changed The World, Twice” by David Brooks.

Watch Benjamin Grant’s 02017 TED talk.

May 15, 2018

The Role of Art in Addressing Climate Change: An interview with José Luis de Vicente

“Sounds super depressing,” she texted. “That’s why I haven’t gone. Sort of went full ostrich.”

That was my friend’s response when I asked her if she had attended Després de la fi del món (After the End of the World), the exhibition on the present and future of climate change at the Center of Contemporary Culture in Barcelona (CCCB).

Burying one’s head in the sand when it comes to climate change is a widespread impulse. It is, to put it brusquely, a bummer story — one whose drama is slow-moving, complex, and operating at planetary scale. The media, by and large, underreports it. Politicians who do not deny its existence struggle to coalesce around long-term solutions. And while a majority of people are concerned about climate change, few talk about it with friends and family.

Given all of this, it would seem unlikely that art, of all things, can make much of a difference in how we think about that story.

José Luis de Vicente, the curator of Després de la fi del món, believes that it can.

“The arts can play a role of fleshing out social scenarios showing that other worlds are possible, and that we are going to be living in them,” de Vicente wrote recently. “Imagining other forms of living is key to producing them.”

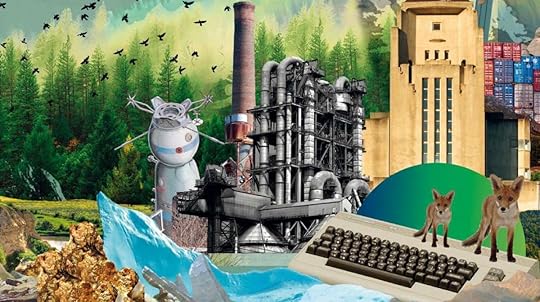

Scenes from “After the End of the World.” Via CCCB.

The forms of living on display at Després de la fi del món are an immersive, multi-sensory confrontation. The show consists of nine scenes, each a chapter in a spatial essay on the present and future of the climate crisis by some of the foremost artists and thinkers contemplating the implications of the anthropocene.

“Mitigation of Shock” by Superflux. Via CCCB.

In one, I find myself in a London apartment in the year 02050.¹ The familiar confines of cookie-cutter IKEA furniture give way to an unsettling feeling as the radio on the kitchen counter speaks of broken food supply chains, price hikes, and devastating hurricanes. A newspaper on the living room table asks “HOW WILL WE EAT?” The answer is littered throughout the apartment, in the form of domestic agriculture experiments glowing under purple lights, improvised food computers, and recipes for burgers made out of flies.

“Overview” by Benjamin Grant. Via Daily Overview.

In another, I am surrounded by satellite imagery of the Earth that reveals the beauty of human-made systems and their impact on the planet.

“Win>CCCB.

The most radical scene, Rimini Protokoll’s “Win>Després de la fi del món goes on tour in the United Kingdom and Singapore. All I can say is that it has something to do with jellyfish, and that it is one of the most remarkable pieces of interactive theater I have ever seen.

A “decompression chamber” featuring philosopher Timothy Morton. Via CCCB.

Visitors transition between scenes via waiting rooms that de Vicente describes as “decompression chambers.” In each chamber, the Minister Of The Future, played by philosopher Timothy Morton, frames his program. The Minister claims to represent the interests of those who cannot exert influence on the political process, either because they have not yet been born, or because they are non-human, like the Great Barrier Reef.

“Aerocene” by Tomás Seraceno. Via Aerocene Foundation.

A key thesis of Després de la fi del món is that knowing the scientific facts of climate change is not enough to adequately address its challenges. One must be able to feel its emotional impact, and find the language to speak about it.

My fear—and the reason I go “full ostrich”—has long been that such a feeling would come about only once we experience climate change’s deleterious effects as an irrevocable part of daily life. My hope, after attending the exhibition and speaking with José Luis de Vicente, is that it might come, at least in part, through art.

“This Civilization is Over. And Everybody Knows It.”

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

AHMED KABIL: I suspect that for a lot of us, when we think about climate change, it seems very distant — both in terms of time and space. If it’s happening, it’s happening to people over there, or to people in the future; it’s not happening over here, or right now. The New York Times, for example, published a story finding that while most in the United States think that climate change will harm Americans, few believe that it will harm them personally. One of the things that I found most compelling about Després de la fi del món was how the different scenes of the exhibition made climate change feel much more immediate. Could you say a little bit about how the show was conceived and what you hoped to achieve?

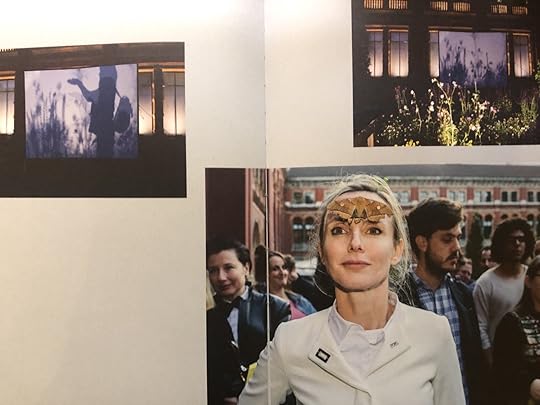

José Luis de Vicente. Photo by Ahmed Kabil.

JOSÉ LUIS DE VICENTE: We wanted the show to be a personal journey, but not necessarily a cohesive one. We wanted it to be like a hallucination, like the recollection of a dream where you’re picking up the pieces here and there.

We didn’t want to do a didactic, encyclopedic show on the science and challenge of climate change. Because that show has been done many, many times. And also, we thought the problem with the climate crisis is not a problem of information. We don’t need to be told more times things that we’ve been told thousands of times.

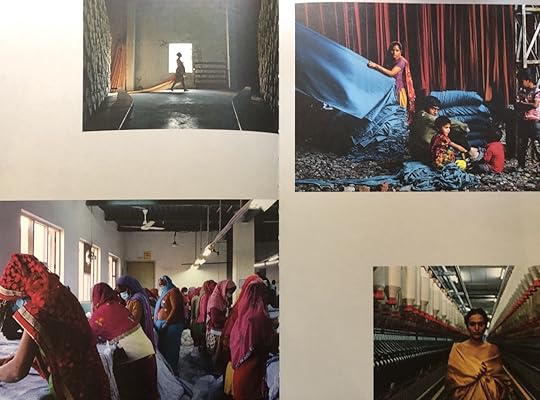

“Unravelled” by Unknown Fields Division. Via CCCB.

We wanted something that would address the elephant in the room. And the elephant in the room for us was: if this is the most important crisis that we face as a species today, if it transcends generations, if this is going to be the background crisis of our lives, why don’t we speak about it? Why don’t we know how to relate to it directly? Why does it not lead newspapers in five columns when we open them in the morning? That emotional distance was something that we wanted to investigate.

One of the reasons that distance happens is because we’re living in a kind of collective trauma. We are still in the denial phase of that trauma. The metaphor I always like to use is, our position right now is like the one you’re in when you go to the doctor, and the doctor gives you a diagnosis saying that actually, there’s a big, big problem, and yet you still feel the same. You don’t feel any different after being given that piece of news, but at the same time intellectually you know at that point that things are never going to be the same. That’s where we are collectively when it comes to climate change. So how do we transition out of this position of trauma to one of empathy?

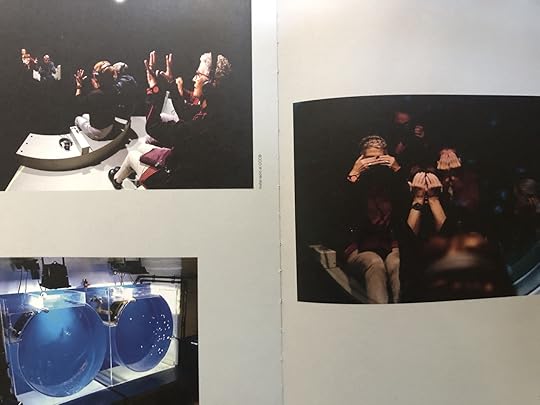

“Win>CCCB.

We also wanted to look at why this was politically an unmanageable crisis. And there’s two reasons for that. One is because it’s a political message no politician will be able to channel into a marketable idea, which is: “We cannot go on living the way we live.” There is no political future for any way you market that idea.

The other is—and Timothy Morton’s work was really influential in this idea—the notion that: “What if simply our senses and communicative capacities are not tuned to understanding the problem because it moves in a different resolution, because it proceeds on a scale that is not the scale of our senses?”

Morton’s notion of the hyper-object—this idea that there are things that are too big and move too slow for us to see—was very important. The title of the show comes from the title of his book Hyperobjects: An Ecology of Nature After the End of the World (02013).

AHMED KABIL: One of the recent instances of note where climate change did make front-page news was the 02015 Paris Agreement. In Després de la fi del món, the Paris Agreement plays a central role in framing the future of climate change. Why?

JOSÉ LUIS DE VICENTE: If we follow the Paris Agreement to its final consequences, what it’s saying is that, in order to prevent global temperature from rising from 3.6 to 4.8 median degrees Celsius by the end of the 21st century, we have to undertake the biggest transformation that we’ve ever done. And even doing that will mean that we’re only halfway to our goal of having global temperatures not rise more than 2 degrees, ideally 1.5, and we’re already at 1 degree. So that gives a sense of the challenge. And we need to do it for the benefit of the humans and non-humans of 02100, who don’t have a say in this conversation.

“Overview” by Benjamin Grant. Via CCCB.

There are two possibilities here: either we make the goals of the Paris Agreement—the bad news here being that this problem is much, much bigger than just replacing fossil fuels with renewable energies. The Tesla way of going at it, of replacing every car in the world with a Tesla—the numbers just don’t add up. We’re going to have to rethink most systems in society to make this a possibility. That’s possibility number one.

Possibility number two: if we don’t make the goals of the Paris Agreement, we know that there’s no chance that life in the end of the 21st century is going to look remotely similar to today. We know that the kind of systemic crises we have are way more serious than the ones that would allow essential normalcy as we understand it today. So whether we make the goals of the Paris Agreement or not, there is no way that life in the second part of the 21st century looks as it does today.

That’s why we open the exhibition with McKenzie Wark’s quote.

“This civilization is over. And everybody knows it.” — McKenzie Wark

This civilization is over, not in the apocalyptic sense that the end of the world is coming, but that the civilization we built from the mid-nineteenth century onward on this capacity of taking fossil fuels out of the Earth and turning that into a labor force and turning that into an equation of “growth equals development equals progress” is just not sustainable.

“Environmental Health Clinic” by Natalie Jeremijenko. Via CCCB.

So with all these reference points, the show asks: What does it mean to understand this story? What does it mean to be citizens acknowledging this reality? What are possible scenes that look at either aspects of the anthropocene planet today or possible post-Paris futures?

This show should mean different things for you whether you’re fifty-five or you’re twelve. Because if you’re fifty-five, these are all hypothetical scenarios for a world that you’re not going to see. But if you’re twelve this is the world that you’re going to grow up into.

02100 may seem very far away, but the people who will see the world of 02100 are already born.

AHMED KABIL: What role will technology play in our climate change future?

JOSÉ LUIS DE VICENTE: Technology will, of course, play a role, but I think we have to be non-utopian about what that role will be.

The climate crisis is not a technological or socio-cultural or political problem; it’s all three. So the problem can only be solved at the three axes. The one that I am less hopeful about is the political axis, because how do we do it? How do we break that cycle of incredibly short-term incentives built into the political power structure? How do we incorporate the idea of: “Okay, what you want as my constituent is not the most important thing in the world, so I cannot just give you what you want if you vote for me and my position of power.” Especially when we’re seeing the collapse of systems and mechanisms of political representation.

“Sea State 9: Proclamation” by Charles Lim. Via CCCB.

I want to believe—and I’m not a political scientist—that huge social transformations translate to political redesigns, in spite of everything. I’m not overly optimistic or utopian about where we are right now. But our capacity to coalesce and gather around powerful ideas that transmit very easily to the masses allows for shifts of paradigm better than previously. Not only good ones, but bad ones as well.

AHMED KABIL: Is there a case for optimism on climate change?

JOSÉ LUIS DE VICENTE: I cannot be optimistic looking at the data on the table and the political agendas, but I am in the sense of saying that incredible things are happening in the world. We’re witnessing a kind of political awakening. These huge social shifts can happen at any moment.

And I think, for instance, that the fossil fuel industry knows that it’s the end of the party. What we’re seeing now is their awareness that their business model is not going to be viable for much longer. And obviously neither Putin nor Trump are good news for the climate, but nevertheless these huge shifts are coming.

“Mitigation of Shock” by Superflux. Via CCCB.

Kim Stanley Robinson always mentions this “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” I think that’s where you need to be, knowing that big changes are possible. Of course, I have no utopian expectations about it—this is going to be the backstory for the rest of our lives and we’re going to have traumatic, sad things happening because they’re already happening. But I’m quite positive that the world will definitely not look like this one in many aspects, and many things that big social revolutions in the past tried to make possible will be made possible.

If this show has done anything I hope it’s made a small contribution in answering the question of how we think about the future of climate change, how we talk about it, and how we understand what it means. We have to exist on timescales more expansive than the tiny units of time of our lives. We have to think of the world in ways that are non-anthropocentric. We have to think that the needs and desires of the humans of now are not the only thing that matters. That’s a huge philosophical revolution. But I think it’s possible.

Notes

[1] The Long Now Foundation uses five digit dates to serve as a reminder of the time scale that we endeavor to work in. Since the Clock of the Long Now is meant to run well past the Gregorian year 10,000, the extra zero is to solve the deca-millennium bug which will come into effect in about 8,000 years.

Learn More

Stay updated on the After The End of The World exhibition.

Read The Guardian’s 02015 profile of Timothy Morton.

Watch Benjamin Grant’s upcoming Seminar About Long-Term Thinking, “Overview: Earth and Civilization in the Macroscope.”

Watch Kim Stanley Robinson’s 02016 talk at The Interval At Long Now on how climate will evolve government and society.

Read José Luis de Vicente’s interview with Kim Stanley Robinson.

May 1, 2018

A Tribute to the Late Larry Harvey

The late Larry Harvey, founder of Burning Man, on what makes the festival so unique. From Larry Harvey’s 02014 Long Now Seminar “Why The Man Keeps Burning,” which you can watch in full here.

April 25, 2018

This is How You Perform a Piece of Music 1,000 Years Long

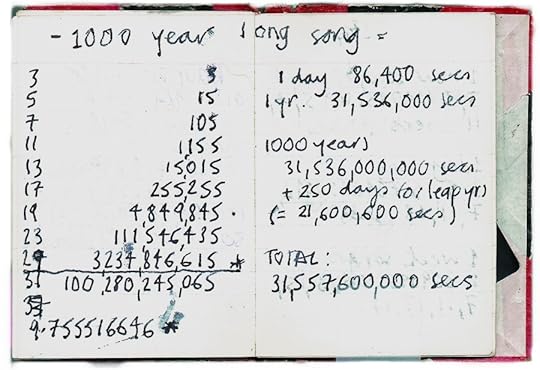

Jem Finer’s initial calculations for his Longplayer project, (01995).

Time is evoked in music in countless ways. In the first article in this series, we explored some of the long-term themes in Brian Eno’s work and traced that influence to his involvement with the 10,000-Year Clock. Through generative music — a compositional technique that uses a small set of rules to generate many unique outcomes — Eno created expansive compositions theoretically capable of lasting over extremely long periods of time. This is precisely the logic behind the 10,000-Year Clock’s Chime Generator.

Questions arise, however, when the extreme potential duration of combinatorially-generated music is taken as a challenge. How does one actually perform a piece that is 1,000 years long? Let’s explore two attempts to answer this question.

John Cage and As Slow As Possible

John Cage preparing a piano (01947).

John Cage’s name will likely remain one of the most enduring among 20th century composers. He pioneered avant garde expeditions that pushed the boundaries of what could be considered composition. His experiments began after studying under another of the 20th century’s masters, the Austrian Arnold Schoenberg, himself a pioneer. One of Schoenberg’s major contributions to modern music was a style of composition he began to develop in the first decade of the 01900s. Though he rejected the term, it came to be known as atonality — lacking a tonal center, or key. Rejecting the key did away with the central organizing structure around which the vast majority of music was traditionally written. Tonal music was organized around a hierarchy of tones, with the key tone at the top. Atonality gave the composer the opportunity to throw out hierarchy and focus on any and all tones as he or she chose.

John Cage.

As Schoenberg and others further developed atonality, some received it well and others did not. Among those who did not were the newly ascendant Nazi party, labeling it “degenerate” and “Bolshevik.” In 01933, Schoenberg emigrated to the United States, where he would soon come to teach at UCLA. One of his students during this time was John Cage, who had explored compositional techniques similar to Schoenberg’s.

A particular avenue of Schoenberg’s that Cage followed is the expansion of the composer’s palette. Cage struggled with harmony, but his work broke down traditional definitions of how to compose and what could be considered an instrument, especially beginning the latter part of the 01930s and ’40s. During that time, he began using household items and non-musical objects in his compositions, as well as writing for a piano that he modified by placing items like coins and tacks in between its hammers and strings.

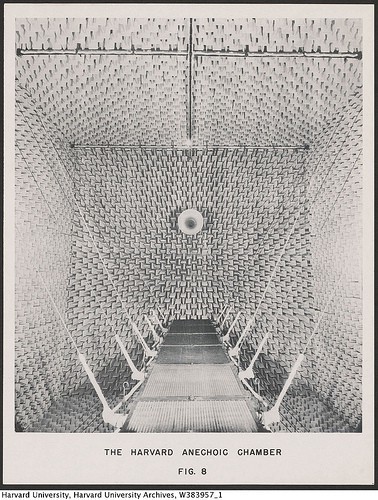

Experimenting with what kind of sounds could be called music led him to his most iconic composition. At Harvard, he was able to access a room specially designed to block out all external sound, an anechoic chamber:

From Rhode Island I went on to Cambridge and in the anechoic chamber at Harvard University heard that silence was not the absence of sound but was the unintended operation of my nervous system and the circulation of my blood. —John Cage

This experience inspired 4’33’’, a composition written in 01952 that instructs its performer to play nothing for four minutes and thirty-three seconds and encourages its listeners to hear the many sounds that make up what would normally be called silence.

Though his most famous, 4’33’’ was but one of many experimental compositions by Cage. Time and rhythm were important to him, and in 01987 he composed a piece for organ that took its name from its tempo. While it would have traditionally been delineated using Italian terms like allegro or andante and more recently in units of Beats Per Measure (BPM), As Slow As Possible leaves quite a bit more open to the performer’s interpretation. Organ²/ASLSP (As SLow aS Possible), as it is more formally known, has been taken on as a challenge by performers over the years, but none have gone to such extreme lengths as a group of organ enthusiasts in Germany.

The church in Halberstadt, Germany where the first organ was built and where John Cage’s “As Slow As Possible” is being performed.

In 01997, a symposium on organs was held in Trossingen, Germany, and among the discussions was one about Cage’s As Slow As Possible. They took the physical life of an organ to be the main limiting factor of the piece’s slowness and hatched a plan to put on one of the longest concerts ever. The first instrument to be created that could be called an organ, they determined, had been built in 01361, in a church in Halberstadt, Germany. Their performance of As Slow As Possible would be in that same church, on a recreation of the original organ. The piece was scheduled to begin in 02000, 639 years after the organ’s invention. They decided that duration would determine the tempo — that the performance must last as long as the oldest known organ, or until 02640.

The Faber organ built specifically for the performance of Cage’s As Slow As Possible.

The 639 years back to the Faber organ with its 12 tone keyboard was mirrored forward at the millennium change into the minimum of 639 years for the current performance. Halberstadt itself was transformed into a structure, both of time and space, pointing simultaneously backward and forward as is manifested in both directions via the duration set for the performance of the piece. (Harriett Watts, December 6th correspondence)

With the church repaired and the organ rebuilt, weights rest on the keys to play the piece and are moved occasionally as the score progresses. The last note change occurred on October 5, 02013. The next change will not occur until 2020. The performance is supported by an organization that wasn’t officially founded until five years after it had begun: The John Cage Organ Project Arts Association. To help the project, enthusiasts are encouraged to choose a year, between now and 02640, to fund and can have a plaque installed in the church to mark the donation. The Association’s website now dutifully tracks the time and notes that have passed and the ones that are yet to come as well as offering information about visiting the organ and events centered around note shifts.

John Cage himself may or may not have imagined As Slow As Possible to be an experiment in long-term thinking, but his admirers have undertaken a challenging exercise on his behalf. If they are successful, his work will be heard and known in Halberstadt for at least the next 6 centuries.

Jem Finer and Longplayer

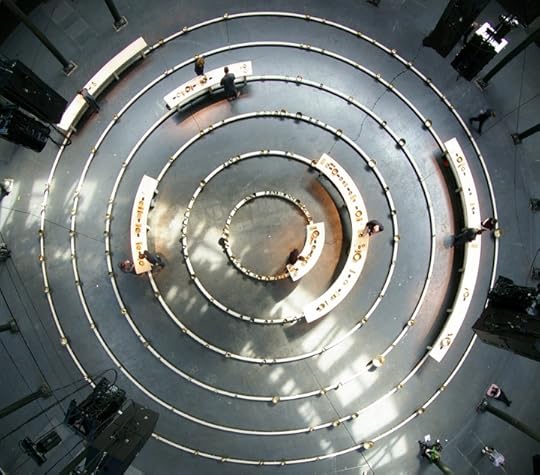

The Longplayer.

Jem Finer’s foray into extremely long-term performance came about very differently from Cage’s. Finer grew up in England and studied not music, but computer science. He was a founding member of punk band The Pogues, and wrote much of the group’s music until they disbanded in 01996.

Jem Finer.

Around that time, he was approached by Artangel, a British group that commissions unique artworks “which impact upon the way we view our world, our times and ourselves in unusual and enduring ways.” Out of the conversations and collaboration with Artangel came Longplayer, a composition intended from its inception to last 1,000 years:

In the mid 1990s, as the year 2000 approached, I started to wonder about how to make sense of a millennium — that is, how to render as sensible or tangible the great span of one thousand years, not so long in cosmic terms but sufficiently longer than a human lifetime — and how to possibly focus the mind on time as a longer and slower process than the frenetic jump-cut pace of the late 20th Century.

It occurred to me that to make a piece of music exactly 1000 years long not only solved the problem of how to “make” time, but added another dimension to the idea by opening up questions about music and sound, composition and duration. The simple idea that popped into my mind, “write a 1000 year long piece of music,” demanded solutions to an ever expanding range of questions; how to deal with changing cultural perceptions of music, how to listen to music too long to hear completely, where to place it, what technology to base it on, how to make it available to the public… and perhaps most importantly, how to plan for its survival. — Jem Finer

Ten centuries’ worth of music would seem a lot to write, but Finer devised a combinatorial system that would generate the full amount from a more reasonable set of source recordings. Finer played singing bowls for the recordings and then wrote a software algorithm that layers and combines the recordings so they generate a pattern that takes 1,000 years to repeat:

Longplayer is composed in such a way that the character of its music changes from day to day and — though it is beyond the reach of any one person’s experience — from century to century.

It works in a way somewhat akin to a system of planets, which are aligned only once every thousand years, and whose orbits meanwhile move in and out of phase with each other in constantly shifting configurations.

In a similar way, Longplayer is predetermined from beginning to end — its movements are calculable, but are occurring on a scale so vast as to be all but unknowable. — Jem Finer

The currently ongoing performance of Longplayer began at midnight on December 31st, 01999. It will continue to play without repetition until December 31st, 02999, at which point it will begin again. It is being performed by a computer and can be heard online or at a number of physical locations around the world, including the lighthouse at Trinity Buoy Wharf in East London, Yorkshire Sculpture Park near Wakefield, Yorkshire, at Kings Place, Kings Cross, London. Beginning on June 7, 02018, a new listening post will launch in Amsterdam in a tower on the roof of the Lloyd Hotel.

On occasion, the digital performance of this piece is accompanied by live performers. In 02010, Long Now helped produce an event in which Jem Finer and others filled in for the computer for a 1,000 minute (that’s 16.6 hours) segment.

Unlike As Slow As Possible, Longplayer has always been explicitly about long-term projects and survival. To sustain funding and continuity through changes in culture and technology, the Longplayer Trust was established. In 02017, a new fund, Buying Time, was launched.

Jem Finer intended from the start to grapple with the long-term in Longplayer. For eighteen years, the piece has resonated online, in listening stations and concert halls. He has worked to ensure it will ring throughout this Millennium and in so doing, to encourage us to consider such a long time-span.

Written by Austin Brown , Danielle Engelman , and Alex Mensing . Edited and updated by Ahmed Kabil .

Learn More

Read a 02011 Washington Post profile of John Cage’s As Slow As Possible performance.

Read a 02009 Guardian profile of Jem Finer’s Longplayer.

In 02017, Longplayer hosted a Longplayer Conversation between naturalist Sir David Attenborough and sound recordist Chris Watson.

Read about the conceptual background of Longplayer.

April 20, 2018

Tim O’Reilly’s Book List for the Manual for Civilization

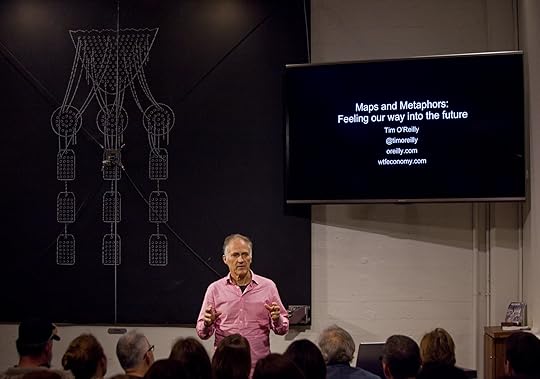

Tim O’Reilly speaking at The Interval at Long Now in January 02018. Photo: Gary Wilson

In 02009 Tim O’Reilly told Forbes magazine how studying Greek and Latin Classics had influenced his business career:

John Cowper Powys noted in The Meaning of Culture, [that] culture (vs. mere education) is how you put what you’ve learned to work in your own life, seeing the world around you more deeply because of the historical, literary, artistic and philosophical resonances that current experiences evoke. Classical stories come often to my mind, and provide guides to action.

That’s a good summary of the goal of our Manual for Civilization project: to identify books that will resonate for those living in the distant future. What information won’t expire in a century? What literature will still speak to our descendants across a millennia? What ideas can carry forward and be useful tools as Plato, Lao Tzu, Homer, continue to have wisdom for us today? What texts will prove essential for upcoming generations, weathering time to become the “new” Classics?

Following his recent talk at The Interval, we asked Tim O’Reilly if he’d be willing to make a list of books he felt could meet those challenging criteria. We’re so grateful that he did, and his full list is below.

Of course, Tim’s expertise doesn’t stop with the ancient world. From the Classics he would move on to the cutting edge. The groundbreaking software and technical manuals his company produced starting in the 01980s would ultimately track the evolution of Free and Open Source software, the rise of the Internet, the Web, and other technological trends that underpin our networked world today.

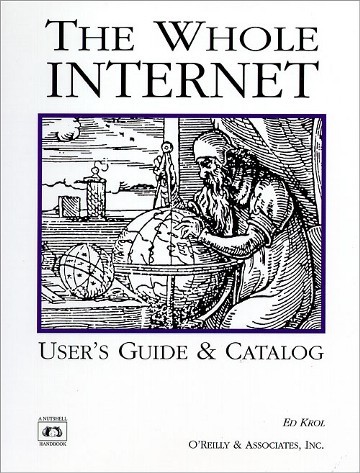

In 01993 O’Reilly & Associates published The Whole Internet User’s Guide & Catalog, the first popular book about the Internet. It was eventually named one of the most important books of the 20th century.

That book included a chapter on the “World Wide Web” which was less than two years old. “Those who don’t use the Net are increasingly getting the feeling of being left out,” wrote Stewart Brand 25 years ago in hisrecommendation of The Guide.

As the 01990s progressed, the Web became friendlier and more useful; more people were on it and fewer left out. The amateurs building websites became professionals, and a geeky niche became big business. Throughout, O’Reilly books seemed to arrive simultaneously with each new useful tool that extended the Internet’s capabilities. A stack of manuals that kept pace with the stacks of technologies. Putting friendly animal faces on a menagerie of mostly open source tools.

Tim confirms that “The Whole Internet” title is an homage to Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog

O’Reilly & Associates has become O’Reilly Media, Inc today, which still publishes books, but also runs conferences, an online learning platform, and more. Tim’s insight and advocacy continues to be crucial for technology’s progression: through Web 2.0, Big Data, Internet as a platform, the Maker movement, to the Cloud and beyond.

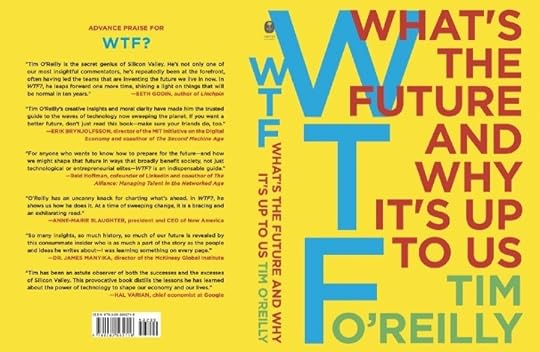

His latest book is WTF?: What’s the Future and Why It’s Up to Us (02017) which Tim describes as “a memoir, business strategy guide, and call to action.” As a book that encompasses both a history of innovation and thinking about the future, we’ve added a signed copy to The Manual for Civilization.

While he still writes about specific companies and software, Tim’s underlying focus is on larger questions about technology and culture: how does tech impact the future of government and the economy? What elements of this complex system can be modified to lead to better outcomes? Ultimately these are societal equations, but technology can be a lever.

You‘ll find these themes not only in WTF?, but also in Tim’s 02012 Long Now talk Birth of the Global Mind from our Seminar series.

Book list from Tim O’Reilly, recommended on Feb 26, 02018:

“This is far from comprehensive, but here are a few personal favorites.”

Religious / Philosophical Works:

The Way of Life According to Lao Tzu translated by Witter Bynner

The Bhagavad Gita translated by Christopher Isherwood

The Analects of Confuciustranslated by Roger Ames and Henry Rosemont

The Trial and Death of Socratesby Plato (translated by GMA Grube, revised by John Cooper)

Zen in the Art of Archery by Eugene Herrigel

The New Testament (read this answer on Quora about which translation to read)

An Introduction to Realistic Philosophy by John Wild

The Hero With a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell

The Masks of God (4 volumes) by Joseph Campbell

Literature:

The Complete Works of William Shakespeare

Chapman’s Homer: The Iliad and The Odyssey translated by George Chapman

Samuel Johnson: Poems and Selected Prose

To The Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

The Palm at the End of the Mind by Wallace Stevens

The Four Quartets by T.S.Eliot

Two books of poetry that Tim included in his list, both of which he referenced during his Interval talk

Science, Technology, and Society:

A Pattern Language also appears on Stewart Brand & Brian Eno’s book lists

A Pattern Language, Chris Alexander

The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs

Governing the Commons Elinor Ostrom

The Pleasure of Finding Things Out, Richard Feynman

The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Richard Feynman

Stuff that would be useful if civilization declines:

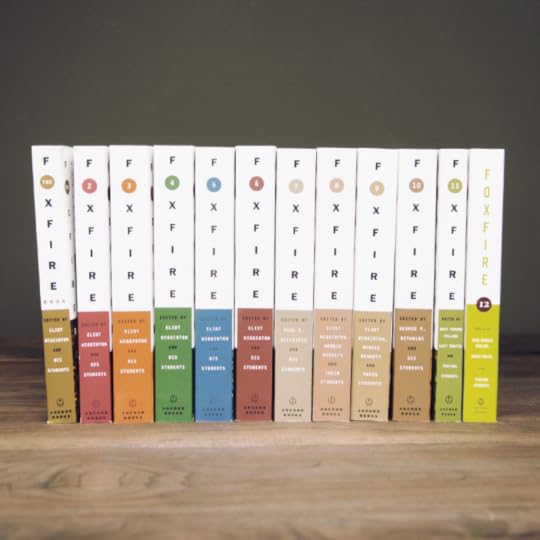

The Foxfire Books edited by Eliot Wigginton (more info)

The Tracker: The True Story of Tom Brown Jr. by Tom Brown

Putting Food By by Ruth Hertzberg

Luther Burbank: His Methods and Discoveries and Their Practical Application by Luther Burbank

(Burbank was one of North America’s foremost American plant breeders. He experimented with thousands of plant varieties and developed many new ones — more info here)

Plant and mushroom identification manuals for every major geography: Edible Wild Plants: A North American Field Guide and

Edible Wild Mushrooms of North America.

Guide to Identifying Trees and Shrubs by Mark Zampardo (or similar)

First published in 01972, the Foxfire book series documents a wide range of Appalachian crafts, traditions, and practical skills from fencemaking to corn shuckin to telling ghost stories

Practical Books for making and fixing things:

From Tim:

You also need engineering, including (bicycles, flight, bridges, and factories), spinning and weaving and the manufacturing technology thereof, metallurgy, materials science, math (including slide rule design and logarithmic tables), chemistry, biology, fundamentals of computer chips (and alternate ways of doing computing without the ability to do a full fab).

We’ve already added books on some of these subjects via Kevin Kelly’s list, George Dyson’s list, and Rick & Megan Prelinger’s list, among others. Tim talks more about books that have influenced him here.

Thanks to Tim for this thoughtful list. We’re excited to share it, and we are acquiring all the books mentioned for the Manual for Civilization library. You can browse what we have so far in person at The Interval, our bar/cafe in San Francisco. Or read more book lists for the Manual from Brian Eno, Stewart Brand, Maria Popova, among others.

Tim’s own most recent book: WTF?: What’s the Future and Why It’s Up to Us came out in 02017

This list is an excerpt of the 3,500 book crowd-curated Manual For Civilization library which we are compiling to back up the essential knowledge of civilization. More than 800 titles are already available online at The Internet Archive.

March 24, 2018

Paleolithic Cave Paintings Appear to be the Earliest Examples of Sequential Animation and Graphic Narrative

In the 02010s, the animated GIF, for better or worse, took hold as the visual language of internet culture. The ubiquity and increased power of mobile devices enabled users to share animations with ease. And share they did. In 02016, the GIF-sharing site Giphy revealed that its 100 million daily active users sent 1 billion GIFs a day.

While seemingly frivolous, these animations satisfied a real need online: non-linguistic social and emotional cues, difficult to convey in purely text-based communication, could be simply expressed through the visual communication of GIFs.

The Jean-Luc Picard “facepalm” GIF leaves no ambiguity about one’s emotional intention.

Many pointed out that the GIF trend hearkened back to earlier periods of history — such as the 01990s, when the GIF format first proliferated the web, or the 01800s, when Eadweard Muybridge, John Hershel, and others experimented with early animation techniques that were a prelude to modern cinema.

Animation of Eadweard Muybridge’s “Sally Gardner at a Gallop” (01872).

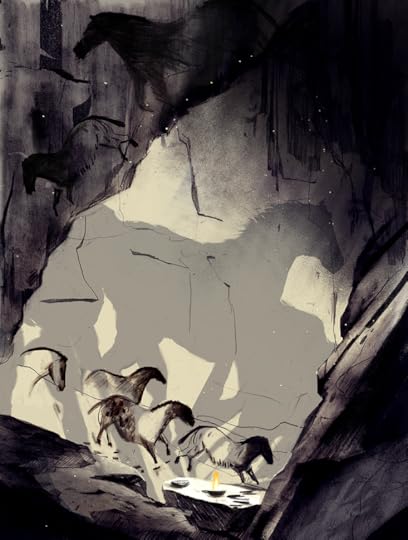

But one can go back even further, all the way to the Stone Age. Marc Azéma, a Paleolithic researcher and filmmaker, claimed in a 02012 paper that the cave paintings found in Lascaux, Chauvet, and other famous Paleolithic caves—the oldest of which were painted 32,000 years ago—were actually early animations:

Palaeolithic artists designed a system of graphic narrative that depicted a number of events befalling the same animal, or groups of animals, so transmitting an educational or allegorical message. They also invented the principle of sequential animation, based on the properties of retinal persistence. This was achieved by showing a series of juxtaposed or superimposed images of the same animal.

The effect of animation was likely achieved, Azéma claims, by the flickering of a lamp as it was moved across the stone wall. To demonstrate the effect, Azéma made a video animating the juxtaposed and superimposed cave painting images.

As science journalist Zach Zorich notes, when Lascaux was discovered in 01940, over 100 stone lamps were found throughout the cave, lending credence to Azéma’s claims. The original placement of the lamps, however, was not recorded.

“At the time, archeologists did not consider how the brightness and the location of lights altered how the paintings would have been viewed,” Zorich writes. “In general, archeologists have paid considerably less attention to how the use of fire for light affected the development of our species, compared to the use of fire for warmth and cooking.”

Image via Nautilus.

Some of these paintings, such as the “Grand Panneau” in Chauvet, depicted not only movement, but narrative. As such, Azéma considers them a progenitor of cinema.

To buttress his claims that the cave paintings were intentionally animated, Azéma raises another apparent example of Paleolithic animation. In 01868, archaeologists found a bone disk a little over an inch in diameter in southwestern France. Scholars estimate the disk is between 14,000 to 21,000 years old. Both sides of the disk depict a doe, with one side showing the doe standing, and the other showing it lying down.

Azema’s reproduction of the spinning disk.

Azéma hypothesized that the disk was depicting animation, and created a reproduction to test it out. He passed a string through the hole in the center of the disc, and pivoted it rapidly by pulling both ends of the string. The two images are superimposed on the retina in quick succession, giving the appearance of the animal sitting down and getting up.

“Thus,” writes Azéma, “the Palaeolithic artists invented an optical toy, whose principle was to be found again with the invention of the thaumatrope in 01825, which is itself the direct ancestor of the cinematic camera.”

An example of a thaumatrope, invented by John Hershel in 01825.

Archaeologists have tended to interpret artifacts like the spinning disc as ritual or decorative objects, rather than toys. Recent work by scholars such as Kristine Garroway and Michelle Langley has drawn attention to the myriad of artifacts across the world dating back tens of thousands of years that were more likely used for purposes of play than worship.

Like the GIFs of today, these early animations served to entertain while also fulfilling a deeper function. In the case of the cave paintings and the spinning disk, Azéma believes that the depiction of a number of events befalling the same animal or groups of animals “transmitted an educational or allegorical message.”

According to science writer Steven Johnson, even if these animations were simply created for purposes of delight and entertainment, that too would be fulfilling an essential function in the evolution of civilization: activating our sense of interest and delight in the world—which ultimately powers innovation.

“There’s a whole world of seemingly frivolous things that have been part of the human experience for tens of thousands of years that are nonetheless incredibly productive and important to our civilization,” Johnson said in a recent Seminar on Long-term Thinking. “These forms of delight, these forms of play have actually been significant drivers of change and of progress in society.”

February 20, 2018

Clock of the Long Now – Installation Begins

“The Long Now is the recognition that the precise moment you’re in grows out of the past and is a seed for the future.”

– Brian Eno (founding board member of The Long Now Foundation)

After over a decade of design and fabrication, we have begun installing the first parts of the Clock of the Long Now on site in West Texas. In this video you can see the first elements to be assembled underground, the drive weight, winder and main gearing. This is the first of many stages to be installed, and we continue to fabricate parts for the rest of the Clock in several shops along the west coast.

The 10,000 Year Clock was conceived by Long Now co-founder Danny Hillis as an icon to long-term thinking, and the first prototype of the Clock now resides in the Science Museum in London. This monument scale version, built in partnership with Long Now supporter Jeff Bezos, began with construction of the underground site itself, and is now moving into the installation phase.

This monument scale Clock is designed to run for ten millennia with minimal maintenance and interruption. The Clock is powered by mechanical energy harvested from the temperature difference from day to night, as well as the people that visit it. The primary materials used in the Clock are special grades of stainless steel, titanium and dry running ceramic ball bearings.

The Long Now Foundation was founded in 01996 as a non-profit dedicated to encouraging long-term thinking and responsibility. The 10,000 Year Clock is one of our many projects which include long-term data archiving, documenting endangered languages, and producing events and media that engage the long-term future. Long Now is entirely funded by donations and the support of more than 9000 members around the world. Find out more at Longnow.org

Some of the engineers and fabricators seen this video include:

Jascha Little: Power System Lead Engineer

Brian Ford: Lead Install Engineer

Jake Faw: Machinist and Install

Alexander Rose: Project Design and Install

Sean Riley: Lead Rigging Design

Dave Freitag: Rigger

Aaron Griffith: Site Supervisor

We would also like to thank the amazing people, partners, shops, and artisans that we have worked with over the years to make these parts and the underground site. Without all their devoted efforts and attention to detail this work would not be possible.

Applied Invention

Machinist Inc.

Rand Machine Works

Swaggart Brothers Construction

Seattle Solstice

Bollinger Atelier

NW Precast

CG Mechanical

Boca Bearings

LMI

Autodesk

Video Production by Sustainability Media

Director of photography: Chris Baldwin

Photography and editing: Jesse Chandler

February 17, 2018

How Warren Buffett Won His Multi-Million Dollar Long Bet

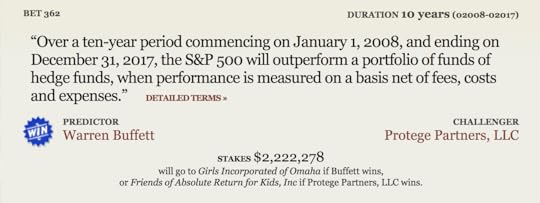

This year, Warren Buffett won his multi-million dollar, decade-long Long Bet .

From the preacher warning that the day of reckoning is nigh, to the sports analyst prognosticating about the outcome of next week’s big game, to the fortune teller calling for hard times in Mercury retrograde, predictions are pervasive, but accountability is rare. That the vast majority of predictions fail to come true is hardly a deterrent; we tend to remember the few that do.

This is a story about a prediction that was made ten years ago, on the eve of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, by Warren Buffett, one of the three richest people in the world. Unlike most predictions, Buffett’s came to pass. And unlike most predictors, Buffett was willing to put his money where his mouth was.

I. The Oracle of Omaha

InMay 02006, some 20,000 investors convened, as they did every year, at the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting to hear the Oracle of Omaha hold forth. After issuing prophecies on matters such as whether to invest in newspapers (don’t), and a looming housing bubble (there would be), Berkshire Hathaway CEO and legendary investor Warren Buffett took aim at hedge fund managers and the exorbitant fees they charged investors for their supposed expertise in beating the market.

The scene at the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting. Sarah Hoffman/The World-Herald

“If your wife is going to have a baby,” Buffett said, “you’d be better to call an obstetrician than do it yourself. If your pipes leak, you should call a plumber.Most professions add value beyond what the average person can do for themselves. But in aggregate, the investment profession does not do this — despite $140 billion in total annual compensation.”

Every hedge fund manager believes they’ll be the exception that outperforms the market, Buffett said, even after taking into account the high fees they charge. Some certainly do. But over time, and in aggregate, the “math doesn’t work.”

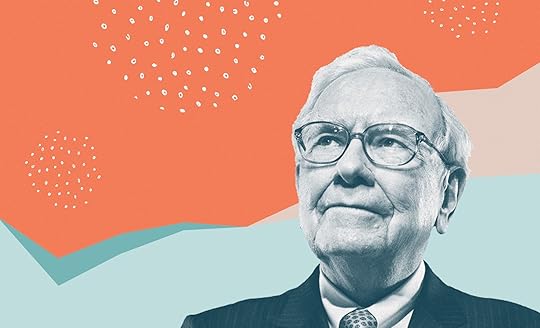

Warren Buffett at the Berkshire Hathaway annual shareholders meeting in Omaha in 2015. Bloomberg via Getty images

Buffett said he was willing to bet anyone $500,000 that over ten years, an S&P index fund would outperform a collection of hedge funds. An index fund, at low-risk and low-cost, neither underperforming nor overperforming the market, has been called the “most boring fund there is.” It simply follows the market’s undulations, for better or for worse. And, since it’s not actively managed, the fees are a fraction of something like a hedge fund. In Buffet’s eyes, that’s almost always a better investment than trusting the experts.

As he wrote in his 02017 Berkshire Hathaway annual report:

Over the years, I’ve often been asked for investment advice, and in the process of answering I’ve learned a good deal about human behavior. My regular recommendation has been a low-cost S&P 500 index fund. To their credit, my friends who possess only modest means have usually followed my suggestion.

I believe, however, that none of the mega-rich individuals, institutions or pension funds has followed that same advice when I’ve given it to them. Instead, these investors politely thank me for my thoughts and depart to listen to the siren song of a high-fee manager or, in the case of many institutions, to seek out another breed of hyper-helper called a consultant.

Buffett didn’t have any takers that weekend, nor in the months that followed. But in July 02007, Ted Seides, a principal at investment firm Protégé Partners, wrote Buffett to say he was in. “For hedge funds, success can mean outperforming the market in lean times, while underperforming in the best of times,” Seides later wrote in his official argument against Buffett’s bet. “Through a cycle, nevertheless, top hedge fund managers have surpassed market returns net of all fees, while assuming less risk as well. We believe such results will continue.”

Seides reasoned that Protégé would have an eighty-five percent chance of winning. And anyway, the bet would doubtless garner Protégé a lot of publicity.

Ted Seides and Warren Buffett. Fortune

The question then became how to place the bet legally and publicly. Betting where bettors keep the money winnings is defined as gambling and is illegal throughout the United States. Though some may do it under the table, Buffett and Protégé wanted the bet to play out in the public, with their reputations on the line. For that, there was really only one game in town: Long Bets, The Long Now Foundation’s public arena for competitive predictions of interest to society. Each side picks a charity, and the winnings go to the winner’s charity choice. That was just fine with Buffett and Protégé. $1 million might make a substantial difference in most people’s lives, but it’s a different story when a man with a net worth in the tens of billions of dollars takes on a hedge fund. After all, this bet wasn’t about the money. It was about being right.

II. Wanna Bet?

The story of Long Bets begins, appropriately, with a bet. In 01995, Kevin Kelly, then-Executive Editor of Wired, was interviewing self-described neo-luddite Kirkpatrick Sale, who believed the end of the world was imminent. In the interview, Sale said that by 02020, humanity would suffer “multinational global currency collapse, social friction and warfare both between the rich and the poor and within nations, and […] continent-wide environmental disasters causing death and great migrations of people” — a perspective that, suffice it to say, Kelly did not share.

“Would you be willing to bet on your view?” Kelly asked.

Sale said he was. Kelly pulled out a check for $1,000. The exchange was left in the interview for Wired’s readers to see.

Kevin Kelly, one of the founders of Long Bets. Christopher Michel

“The bet forced both of us to refine strongly held beliefs, and because our predictions were now public, our reputations were on the line,” Kelly later wrote. “This is what public wagers can do: sharpen logic, filter out the halfhearted. Sometimes they can even alter collective views and shape society.”

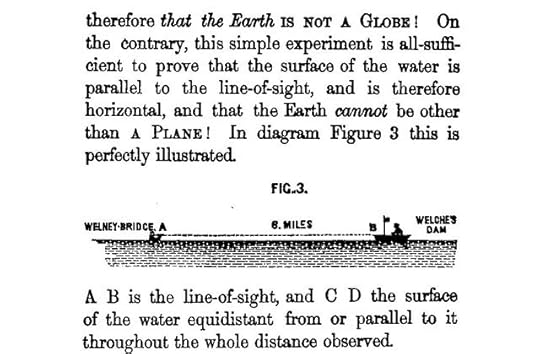

As Kelly notes, there’s a long history of these kinds of public wagers, particularly in science. In 01600, astronomer Johannes Kepler bet his rival Christian Longomontanus that he could derive the formula for the solar orbit of Mars in eight days. It took him five years. Kepler lost the bet, but his calculations ultimately helped bring about modern astronomy. In 01870, flat earther John Hampden made a 500 pound bet with naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace (who, it should be noted, conceived of the theory of evolution independent of Darwin) that he could prove the Earth was flat using the Bedford Level Experiment. Hampden lost the bet, insisted that Wallace cheated, and ultimately was imprisoned for threatening to kill Wallace. The myth of the flat earth was laid to rest, albeit temporarily.

The results from the Bedford Level Experiment confounded scientists for 30 years before it was realized that it is merely an optical refraction effect. Lateral Science

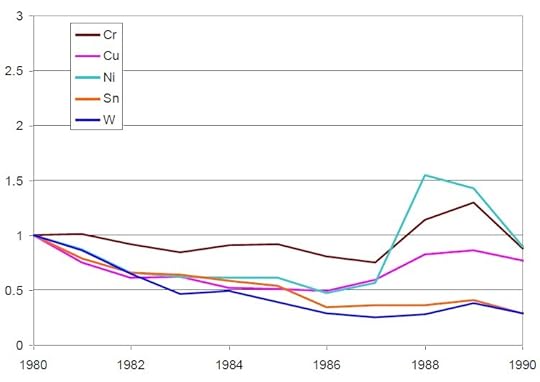

More recently, there’s the bet that biologist and environmentalist Paul Ehrlich made with economist Julian Simon in 01980. Ehrlich bet Simon $10,000 that the prices of five metals (copper, chromium, nickel, tin, and tungsten) would increase over a decade. The prices declined sharply, and Simon won the bet.

The Simon-Ehrlich wager.

The wager received a lot of publicity over the decade, and the result ultimately shaped societal thinking around limited resources. “Simon was a prolific skeptic of environmentalism,” Kelly wrote, “yet nothing that he ever wrote had as much impact on the course of culture as his wager with Ehrlich. That single, relatively small bet transformed the environmental movement by casting doubt on the notion of resource scarcity.” (Although, if the bet were repeated in subsequent decades, Ehrlich would have won, given the rise in commodity prices. On a long enough timescale, however, it’s one more blip in a multiple-centuries-long trend towards decreasing prices).

Kevin Kelly, Stewart Brand, and Long Now Executive Director Alexander Rose. Gary Wilson

Both Kelly and Long Now Foundation co-founder Stewart Brand were intrigued by the Simon-Ehrlich bet and the public accountability and long-term thinking it made possible. (Ehrlich was Brand’s teacher and mentor at Stanford, and his concerns around resource scarcity and overpopulation were ones Brand used to share). Brand formulated the idea that would become Long Bets in an email to the Long Now board in May 02001:

People bet people about things that will happen farther in the future than the horserace next weekend. Peter Schwartz almost bet Hunter Lovins today about when electric-drive autos will be the norm — -in 10–20 years or in 15–25 years.

If Long Now offered a Longbets holding service, they could have bet, say $1,000, with the outcome to be decided in 02016. The money, the bet, and a fee could be placed with Long Now. The money draws interest in behalf of the eventual winner, minus a maintenance fee to Long Now. Long Now robots keep track of Peter and Hunter. As 2016 approaches the file wakes up and contacts them to begin negotiation toward resolution of the bet. If they don’t resolve, the amount is split 50–50. If they resolve, winner takes all. If only one of the two can be found, that person gets the winnings by default. If neither can be found, the money is held a while longer and then is absorbed into Long Now.

I bet it will work.

It did. Brand founded Long Bets in 02002 with Kevin Kelly and a little seeding assistance from Amazon’s Jeff Bezos. The forum asks all predictors to put their name, a solid argument, and a financial pledge down in support of their statement about the future. Long Now, in turn, provides a long-term record where any prediction can be revisited, reviewed, and discussed at any time.

A Long Bet always starts with a prediction. All predictions should come with an argument in support, a financial pledge, and an end-date. The minimum term for a prediction is two years; there is no maximum term.

A prediction becomes a bet when a challenger comes forward with a counterargument. The predictor may then choose to make a bet with the challenger. The predictor and challenger will agree on a wager, and each will choose a charitable cause to receive the winnings.

When the end-date for the bet passes, The Long Now Foundation adjudicates the bet and donates the proceeds to the winner’s charity of choice.

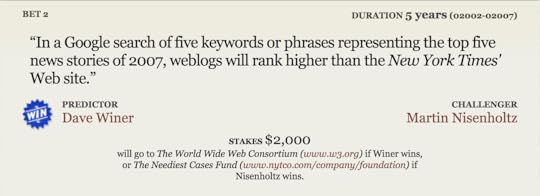

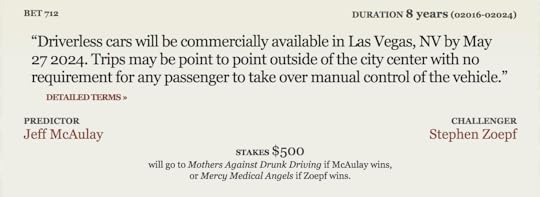

Long Bet #2.

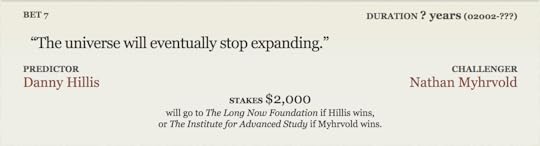

Long Bet #7.

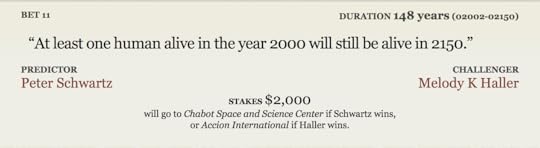

Long Bet #11.

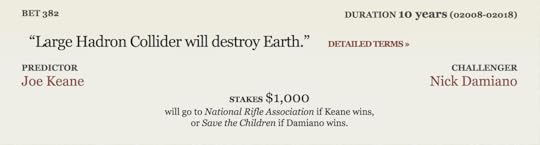

Long Bet #382.

Long Bet #712 .

The Long Bets site offers a public record of all predictions and bets. It highly encourages discussion about what we may learn, or what we have learned, from bets and their outcomes. This discussion feeds improvement of long-term thinking — the real pay-off.

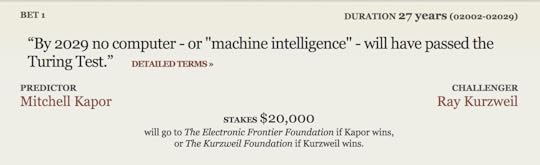

The bets on Long Bets range from the serious, inculcating questions about what it means to be human, to the playful. The first Long Bet on record was between Mitchell Kapor, co-founder of The Electronic Frontier Foundation, and the futurist Ray Kurzweil, who popularized the idea of the technological singularity. Kapor bet Kurzweil $10,000 that by 02029, no computer — or “machine intelligence” — will have passed the Turing test (the test conceived in 01950 by mathematician Alan Turing that tests whether a machine is capable of human intelligence).

Long Bet #1.

The first winner of a Long Bet was actor and Red Sox fanatic Ted Danson. In 02002, the late Time Editor Michael Elliott bet Danson $1,000 that the U.S. Men’s soccer team would win the World Cup before the Red Sox win the World Series. “The Red Sox have had such bad luck in the 20th century,” Danson argued, “I have to believe that in the new millennium it can only get better.” Danson would be vindicated a mere two years later.

Long Bet #8.

The stakes of Long Bets typically ranged in the hundreds and thousands of dollars. Through 02007, the largest bet was the Kurzweil-Kapor Turing test bet. Then along came Warren Buffett.

Long Bet #362.

III. The Tortoise and the Hare

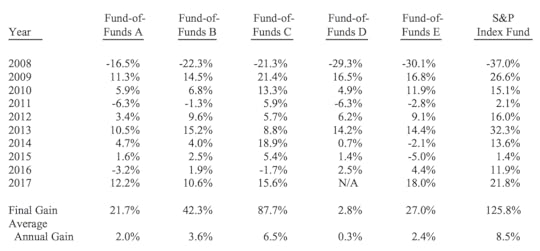

Buffett invested in the Vanguard index fund. Protégé picked five hedge funds of funds (whose names have never been publicly disclosed — although Buffett does see their annual audits).

Buffett and Protégé initially wagered an investment of $320,000 each that was expected become $1 million at the end of the bet. Seides chose the charity Absolute Return for Kids, a London-based philanthropic organization. Buffett chose Girls, Inc. from his hometown of Omaha.

“Buffett’s bet is an ideal Long Bet,” Kevin Kelly wrote once the bet was announced. “It makes a huge difference to anyone who invests in stocks (as do a large percentage of the US, either directly or indirectly) whether a boring index fund yields as much as fancy private hedge funds. The answer either way would be a huge influential signal.”

Carol Loomis, a friend of Buffett’s and reporter for Fortune, wrote at the time that, despite Seides’ confidence that Protégé would win easily, the hedge fund fees Buffett railed against were a significant hurdle. Further, because Protégé chose funds of funds, there was a second level of fees that would be imposed:

On top of the management fee, the hedge funds typically collect 20% of any gains they make. That leaves 80% for the investors. The fund of funds takes 5% (or more) of that 80% as its share of the gains. The upshot is that only 76% (at most) of the annual return made on an investor’s money accrues to him, with the rest going to the “helpers” that Buffett has written about. Meanwhile, the investor is paying his inexorable management fee of 2.5% on capital. The summation is pretty obvious. For Protégé to win this bet, the five funds of funds it has picked must do much, much better than the S&P.

Once the bet was officially announced, the webpage was flooded with comments and vigorous debate. “Voting Against Buffet? [sic],” Louise Murphy commented. “Am quite a novice when it comes to hedge funds and such, but I would never vote against one Warren Buffett. Time will tell.” It was a sentiment many shared.

“Fortunately for us, we’re betting against the S&P’s performance,” Seides said at the time. “Not Buffett’s.”

\The 02008 Financial Crisis hit soon after the bet began. Business Insider UK

In the initial going, the S&P performed horribly. The global financial crisis intensified by November 02008, leaving the S&P down 45% from its 02007 high. After the first year, Protégé fund of funds trounced Buffett’s index fund. But all things considered, it was a bad year for both, with Buffett down 37% and Protégé down 23.9%. Buffett maintained his sense of humor.

“I just hope that Aesop was right,” he said, “when he envisioned the tortoise overtaking the hare.”

He was. Buffett steadily gained ground in the years that followed, finally overtaking Protégé in the bet’s fifth year. And he never looked back. By 02017, it was clear that, short of another collapse in the stock market, Buffett would prevail.

The final scorecard for the bet.

Over the decade-long bet, the index fund returned 7.1% compounded annually. Protégé funds returned an average of only 2.2% net of all fees. Buffett had made his point. When looking at returns, fees are often ignored or obscured. And when that money is not re-invested each year with the principal, it can almost never overtake an index fund if you take the long view.

“In my opinion, the disappointing results for hedge-fund investors that this bet exposed are almost certain to recur in the future,” Buffett said in last year’s Berkshire Hathaway annual report. “When trillions of dollars are managed by Wall Streeters charging high fees, it will usually be the managers who reap outsized profits, not the clients. Both large and small investors should stick with low-cost index funds.”

Seides, meanwhile, thinks Buffett just got lucky, and that the S&P’s performance over the previous decade “vastly overperformed” his expectations. “My guess is that doubling down on a bet with Warren Buffett for the next 10 years would hold greater-than-even odds of victory,” he wrote in his 02017 concession essay.

Perhaps. Buffett, as you might expect, feels otherwise.

“Human behavior won’t change,” he said. “Wealthy individuals, pension funds, endowments and the like will continue to feel they deserve something ‘extra’ in investment advice. Those advisors who cleverly play to this expectation will get very rich. This year the magic potion may be hedge funds, next year something else. The likely result from this parade of promises is predicted in an adage: ‘When a person with money meets a person with experience, the one with experience ends up with the money and the one with money leaves with experience.’”

Left: Warren Buffett and Long Now Executive Director Alexander Rose present the $2.2 million check to Girls Inc. of Omaha on February 16, 02018.

And what of the winnings? As it happens, the bond value of the initial wager appreciated faster than expected, resulting in shifting the investment strategy and growing the winnings to $2.2 million.

It’s a huge win for long-term thinking. But it’s an even bigger win for Girls Inc. of Omaha, which has an annual operating budget of $2.8 million. Protégé, Buffett and Long Now’s Executive Director Alexander Rose settled the bet on Friday, February 16, 02018 at Girls Inc. headquarters.

Long Now co-founder Danny Hillis, Jeffrey Tarrant of Protégé, Alexander Rose, and Warren and Susie Buffett at the Girls Inc. of Omaha check event on February 16, 02018.

“I just told [Executive Director Roberta Wilhelm] to use it where it’s going to do the most good,” said Buffett.

The sum will be used to help renovate an old convent into a transitional home for girls as they age out of foster care. It will be called the Protégé House.

Learn More

Do you have strong opinions about the future? Put your money where your mouth is. Make a bet with Long Bets here.

Listen to Planet Money’s primer on the Bet.

Read Wired’s 02002 Long Bets profile.

Read Long Now’s year-by-year accounting of the bet.