Stewart Brand's Blog, page 25

January 18, 2019

James Turrell’s Roden Crater, an Artwork 45 Years in the Making, Set to Open…Sooner

James Turrell’s Roden Crater.

Last month, Kanye West visited James Turrell’s monumental art project, Roden Crater. Turrell bought the extinct volcano, located in Northern Arizona, in 01977. Since then, work at the site has been aimed at creating a naked-eye observatory using principles of light and perception similar to Turrell’s more accessible installations, but cosmic in scale. An ever more prevalent element of the mythos of the project is the question of when it will be done. Few have seen it as it’s come together over the decades. Kanye West was so impressed by what he saw that he pledged a $10 million donation.

In a statement to The Wall Street Journal, who broke the story about the donation, West said that he wants the Roden Crater Project to be “experienced and enjoyed for eternity.” Turrell told The Wall Street Journal that he was “thrilled” by the gift, as it comes “at a critical juncture of the project.”

Along with West’s donation, Turrell is also partnering with Arizona State University and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to help bring the project closer to completion. The coalition hopes to raise $200 million for final additions to the site, including:

A series of water-filled chambers are coming, fed by underground wells. One 8-foot-deep pool will reflect every sunrise. In a light-spa complex, bathers will dive under a barrier, emerging outdoors looking out across the horizon. In the fumarole, the volcano’s secondary vent, Turrell imagines a brass bath where transducers hooked to a radio telescope will broadcast the sounds of passing planets and the Milky Way underwater. In another space a visitor will sometimes be able to see his or her shadow with the light of Venus. An amphitheater is on the drawing boards too, as well as a wine cellar.

There is still no public timetable on when the project will be completed, but there is hope that parts of the Roden Crater will be open to the public in the next few years.

Learn More

Read our feature about James Turrell’s Roden Crater and other monuments of deep time.

Read Fast Company’s recap of Kanye’s donation and the new partnerships Turrell has secured for the Roden Crater.

January 14, 2019

Deep Civilization, a New Essay Series by BBC, Takes the Long View

BBC Future has launched a new series about “the long view of humanity” called “Deep Civilization:”

[Deep Civilization] aims to stand back from the daily news cycle and widen the lens of our current place in time. Over the coming months, we will explore multi-generational thinking in all its forms, and hear from writers, researchers and artists who are looking beyond the short-term horizon.

Our goal is to explore what really matters in the broader arc of human history and what it means for our descendants, as well as revealing the hidden patterns shaping our societies in the long term.

Its inaugural article, written by Richard Fisher (a managing editor at BBC), explores the perils of short-term thinking, calling it “civilization’s biggest threat.”

Fisher begins by contemplating his young daughter’s future, who might live to see the year 02100. 02100 is an oft-cited milestone in journalism, but thinking about it in the concrete as it relates to his daughter’s future makes Fisher realize we don’t often consider the long view in our daily lives, which will likely yield devastating effects for our future.

The rest of the essay provides an extensive survey of various thinkers and project whose aim is to provide antidotes to short-termism, including The Long Now Foundation’s 10,000 Year Clock, Long Now Research Fellow Roman Krznaric, Jem Finer’s Longplayer, and more:

What these thinkers from myriad fields share is a simple idea: that the longevity of civilisation depends on us extending our frame of reference in time — considering the world and our descendants through a much longer lens. What if we could be altruistic enough to care about people we might never live to see? And if so, what will it take to break out of our short-termist ways?

Learn more

Read Fisher’s piece in full here.

Read our blog post on the Future Library (a project mentioned in the piece), where authors such as Margaret Atwood submit books that will not be read until 2114.

Read our feature on Longplayer.

Future Thoughts

The featured “Long Short” from our Seminar on Long-term Thinking in January 02019 with Martin Rees, “Future Thoughts” by Loek Vugs.

Future Thoughts is an experimental, short film showing a collection of ideas about everyday life and new technologies in the near future.

December 29, 2018

Deep Time

Photo by Darv Robinson on Unsplash

This is the week when we recall what we’ve done last year, and resolve to use time better in the year to come. Indeed, in our everyday lives, time is a precious commodity. We can gain or lose it. We can save, spend or waste it. If our crimes are revealed, we risk having to DO time.

But to scientists, time is something we can measure. Clocks have, over the centuries, been the high-tech artifacts of their era — the water clock, the pendulum clock, Harrison’s chronometer, and so forth up to the incredible precision of atomic clocks — marvels of modern technology, albeit without the evident aesthetic quality of more traditional timepieces. (Though my engineering friends tell me that, viewed through a microscope, there’s beauty in the intricacies of a silicon chip).

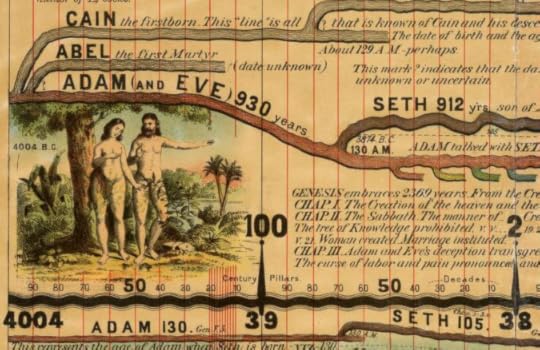

Before there was a reliable calendar — or any records or artifacts that could be reliably dated — the past was a ‘fog’. But this didn’t stop efforts to impose fanciful precise chronologies. Most precise of all was that worked out by James Ussher, Archbishop of Armagh, according to which the world began at 6 pm on Saturday, 22 October, 4004 BC. Right up until 01910, Bibles published by Oxford University Press displayed Ussher’s chronology alongside the text.

Sebastian C. Adams’ 23-foot-long Synchronological Chart of Universal History (01871) was grounded Ussher’s chronology. This excerpt shows 4004 BC as the date when the world began. David Rumsey Map Collection.

Even in 17th century, Ussher’s chronology ran into problems. Jesuit missionaries returned from China, telling of detailed historical records dating back to dynasties before 2350 BC — the proclaimed date for Noah’s Flood. Many were skeptical that the entire history of Earth’s mountains, rivers and fauna could be squeezed into 6000 years. Sir Isaac Newton, in his old age, had abandoned science but was obsessed with completing his own ‘Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms.’ He did not contest Ussher’s dating of human origins, but conjectured that the six ‘days’ of Genesis could each be a prolonged era.

In the 19th century, Darwin’s genius was to recognize how “natural selection of favored variations” could have transformed primordial life into the amazing varieties of creatures, now mainly extinct, that have crawled, swum or flown on Earth. But this emergence —a higgledy-piggledy process, proceeding without any guiding hand — is inherently very slow. Darwin guessed that evolution required not just millions but hundreds of millions of years. He was mindful of supporting evidence from geology. He estimated, by an argument that was actually flawed (and which he cut from later editions of his book) that to carve out the Weald of Kent took 300 million years. If he had seen the Grand Canyon he could have made a more convincing estimate.

Precise radioactive dating now tells us that the Sun and its planets condensed 4.55 billion years ago from interstellar gas in a Galaxy that is part of a still vaster cosmos that emerged from a fiery “beginning” that has now been pinned down to have happened 13.8 billion years ago.

A 13.8-billion-year-long timeline of the universe. NASA.

What happened before the beginning? On this fundamental question, we cannot do much better than Saint Augustine in the 5th century. He sidestepped the issue by arguing that time itself was created with the universe. The ‘genesis event’ is in some ways as mysterious to us as it was to Saint Augustine.

So cosmic history, we now believe, extends over billions of years, not just Ussher’s few thousand years. Our time-horizons have hugely extended back into the past. But there has to be an even greater enlargement in our concept of the future. To our 17th century forbears, history was nearing its close. Sir Thomas Browne wrote, “The World itself seems on the wane. A greater part of Time is spun than is to come.”

Even today most people still somehow think we humans are necessarily the culmination of the evolutionary tree. That hardly seems credible to an astronomer — indeed, we are probably still nearer the beginning than the end. Our Sun has got about 6 billion more years before the fuel runs out. It then flares up, engulfing the inner planets. And the expanding universe will continue — perhaps forever — destined to become ever colder, ever emptier. To quote Woody Allen: “Eternity is very long, especially towards the end.”

Dandora Landfill #3, Plastics Recycling, Nairobi, Kenya 2016. Photograph by Edward Burtynsky .

Our cosmic horizons are far more extensive than those of our forbears. And we’ve entered the anthropocene era when one species, ours, can determine the entire planet’s fate. The collective ‘footprint’ of humans on the Earth is heavier than ever; today’s decisions on environment and energy resonate centuries ahead and will determine the fate of the entire biosphere, and how future generations live.

In contrast, our planning horizons have shrunk because our lives are changing so fast. The political focus is on the urgent and immediate, and the next election. Medieval cathedrals took a century or more to complete. Now, there are few efforts to plan more than two or three decades ahead — or to build structures that will, as the cathedrals have done, offer inspiration for a millennium.

The 10,000 Year Clock, currently under construction in west Texas.

As an antidote to short-termism, we should welcome the initiative of the California-based Long Now Foundation. In an excavation inside the top of a mountain in west Texas, it is building a massive clock designed to tick (very slowly) for 10,000 years, programmed to resound with a different chime every day over that expanse of time. Those who visit it this century will contemplate an artifact built to outlast the cathedrals — and will hope that it will still be ticking a hundred centuries from now, and that this century’s legacy is a world that is sustainable rather than devastated.

Martin Rees, Astronomer Royal, will be speaking at The Long Now Foundation on Monday, January 14, 02019. His book, On The Future: Prospects for Humanity , was recently published by Princeton University Press.

December 20, 2018

Video of Kim Stanley Robinson’s Salon Talk on Ursula K Le Guin is now online

In a recent talk at The Interval, Kim Stanley Robinson, Ursula K Le Guin’s student 40 years ago and now a celebrated science fiction writer himself, reflects on Le Guin the teacher, her impact on his work, and how she changed the world. Watch the full video here.

December 18, 2018

California’s Liquid Assets: Tracing the Water that Powers the World’s Sixth-Largest Economy

This graphic from the California Water Atlas (1979) represents the water flows of major rivers in California. The yellow figures represent the actual flow measured in a single year, with the peak typically occurring in spring. The corresponding blue figures represent the estimated flow of that river in the absence of dams or other human modifications. California Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, courtesy David Rumsey Map Center.

The following is an excerpt from All Over The Map: A Cartographic Odyssey by Betsy Mason and Greg Miller, published in October 2018 by National Geographic.

“This book sets out to tell the biggest story in the richest, most populous state in the Union.” So begins the foreword to a surprisingly ambitious government publication, the California Water Atlas, published in 1979 by the state Governor’s Office of Planning and Research.

The atlas attempted to distill one of the most complex and contentious issues in the state — water use — into a series of maps and data visualizations that any citizen could understand. The goal of its idealistic creators was to use cutting-edge cartography to better inform the public about the water policy issues confronting the state.

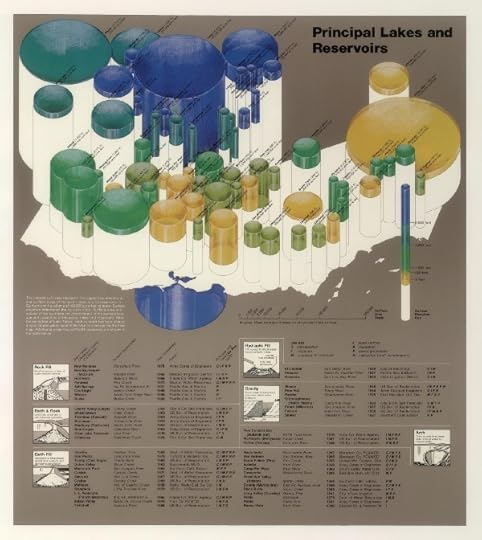

A massive blue cylinder represents Lake Tahoe on this graphic of California’s lakes and reservoirs. The lake, one of the deepest in the world, holds 40 trillion gallons (151 trillion L) of water, dwarfing the state’s other lakes and reservoirs. California Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, courtesy David Rumsey Map Center.

The history and economy of California are inextricably tied to water. Fortunes hinge on where it falls, where it’s diverted to, and who decides how it’s used. So do many of the state’s scenic natural features, from the glacial lakes of the Sierra Nevada to the once thriving wetlands of the great Central Valley.

The idea for the atlas arose from the office of the state’s young governor, Jerry Brown. Brown’s liberal leanings and tendency to embrace the unconventional had earned him the moniker “Governor Moonbeam” from his more conservative critics. One of Brown’s advisors was counterculture hero Stewart Brand, the creator and editor of the Whole Earth Catalog, a progressive magazine and guide to political action. Brand was instrumental in getting the water atlas project off the ground.

The goal was to educate people about where the state’s water came from and how it was being used, Brand says. He insists there was no political agenda. “There were no ‘shoulds,’” he says — no prescriptions about what ought to be done. “The book could be used by someone on any side of the issue to get the facts.”

The entire project — from wrangling the data from various state and local agencies to creating the maps and graphics — was done in just 15 months. It was an amazing feat, especially in the days before computers.

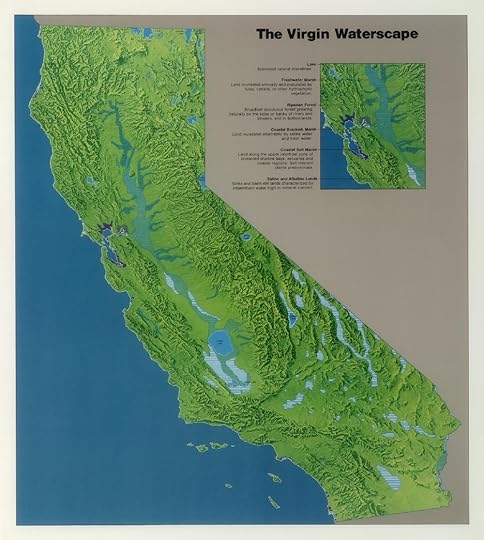

This map of California’s waterways as they existed before significant human intervention was based on historical maps made between 1843 and 1878, when most parts of the state were relatively untouched by settlers. California Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, courtesy David Rumsey Map Center.

The atlas begins with the basics of where water falls as rain and snow and includes several maps like the “Virgin Waterscape” map (see above) that depict the state’s lakes, rivers, and wetlands before humans altered them. It goes on to sketch the history of how inhabitants of the state began to alter that picture in the 19th century as they diverted river water, first for mining and later to meet the needs of a burgeoning agricultural economy and fast-growing cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Several chapters explore the economics of water, including which industries are the heaviest users (petroleum and coal mining, by a wide margin) and the relationship between cost and consumption in urban areas. The graphics, with their groovy 1970s color schemes, may look crude compared to modern data visualizations, but the creative displays of maps and data were groundbreaking in those precomputer days.

These pages from the atlas show five agricultural areas in the state, each represented by two long maps. The top map in each pair shows the type of crops grown there, the bottom one how much irrigation water was applied. California Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, courtesy David Rumsey Map Center.

The digital age had not quite dawned, but it was getting close. William Bowen, a young geography professor at California State University, Northridge, headed the small team of cartographers. Bowen says one breakthrough came when he happened on a new model calculator from Texas Instruments that could do cube roots. That made it possible to quickly calculate the right dimensions for the many three-dimensional graphics — though someone still had to use a ruler to measure them out and mark them on the page.

The atlas was well received when it came out, winning plaudits from cartographers and water wonks alike. The book originally sold for $20, and the first print run quickly sold out. It was almost too nice for its own good, says Brand. “We wound up with a book that immediately found its way into the rare book rooms of libraries,” he says, instead of becoming the continually updated, easily accessible document he had hoped for. If you’re lucky enough to find a copy for sale today, it will probably cost a few hundred dollars. As far as Brand is concerned, that’s a pity. “We inadvertently created a collector’s item instead of a political tool,” he says.

The above is an excerpt from All Over The Map: A Cartographic Odyssey by Betsy Mason and Greg Miller, published in October 2018 by National Geographic.

Learn More:

In 2013, there was an effort to make an interactive digital water atlas inspired by the original. The project has since fizzled out. The original vision for the California Water Atlas still hasn’t been realized, even though the need for it would seem to be as great as ever. Read Greg Miller’s WIRED profile of the proposed atlas here.

Explore the full atlas online at the David Ramsey Map Center.

December 5, 2018

The Equation of Time Cam: Keeping Good Time for 10,000 Years

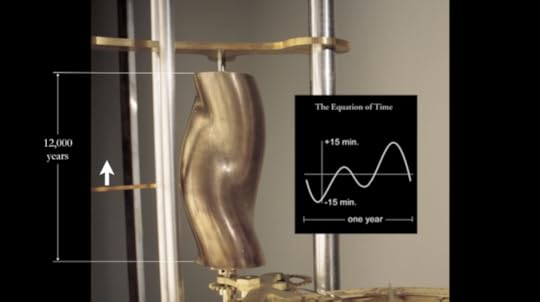

Fig. 1. The Equation of Time Cam.

Fig. 1. The Equation of Time Cam.In the collections of the Royal Observatory of Greenwich, amongst the myriad time-keeping and navigational devices of the past, there sits a curious artifact built to last into a future none of us will witness. Standing half-a-foot tall, it looks more like a sculpture than an instrument of time, with slender curves that lend it the appearance of a human torso.

It is a prototype of the Equation of Time Cam, a mechanism that will be in The Long Now Foundation’s 10,000 Year Clock. The Equation of Time Cam solves one of the crucial design and engineering problems in building a clock meant to last ten thousand years: keeping accurate time while accounting for the slow but significant changes in the Earth’s rotation over the millennia.

Even the most accurate mechanical clocks in the world eventually drift off of the correct time. In order to remain accurate over thousands of years, the 10,000 Year Clock needed a feedback mechanism that could check what time it is, and correct itself. The clock’s builders chose the sun to serve as that feedback mechanism. As Danny Hillis, the inventor of the Clock of the Long Now, puts it (02011):

Human societies have always organized their activities around the rising and setting of the Sun. Civilization required agriculture. Agriculture required sunlight. Much of human culture is organized around a diurnal or annual cadence. […] The Sun matters to humans, even to their devices in the depths of space and on the surfaces of other planets. It has done so throughout history and the Clock makes the statement that it will continue to matter thousands of years into the future.

The Clock keeps time with a pendulum, which generates absolute time.¹ The sun is used to correct any drift. On the sunny days around the solstices at solar noon, a shaft of light will shine into the mountain where the Clock resides, synchronizing it to the sun and providing the input of solar time.

But there’s a discrepancy between solar time and absolute time. That’s because the position of the sun at solar noon throughout the course of a year is not regular. It varies due to the Earth’s elliptical trajectory around the sun (called the eccentricity of Earth’s orbit) and the Earth’s axial tilt (called the obliquity of the ecliptic). This variability is represented by a diagram called an analemma (Figure 2).

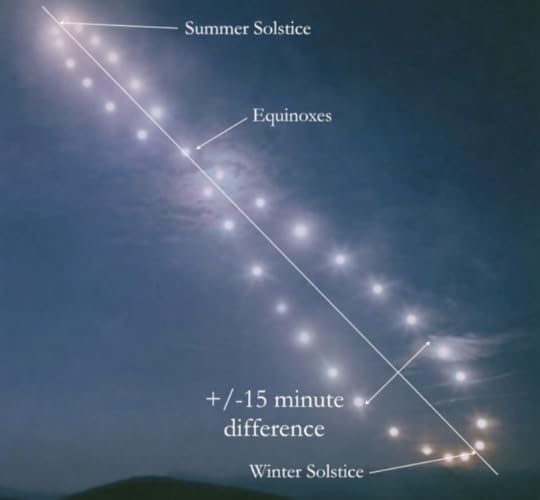

Fig. 2. The analemma showing the sun’s position at solar noon over the course of one year. Note the plus or minus fifteen minute time difference.

Fig. 2. The analemma showing the sun’s position at solar noon over the course of one year. Note the plus or minus fifteen minute time difference.If you were to visit an accurate sundial at exactly noon on a sunny day in mid-February and looked at the time on your watch or phone, this discrepancy would become especially apparent: your watch or phone would read 12:00, but the shadow cast by the sun on the sundial would correspond to 11:46. If you were to do the same on a sunny day in early November, the opposite would be true: 12:00 on your timekeeping device would correspond to 12:14 on the sundial.

The equation of time reconciles the difference between these two kinds of time. It converts solar time to clock time, and vice versa, such that over the course of a year the differences resolve to zero.

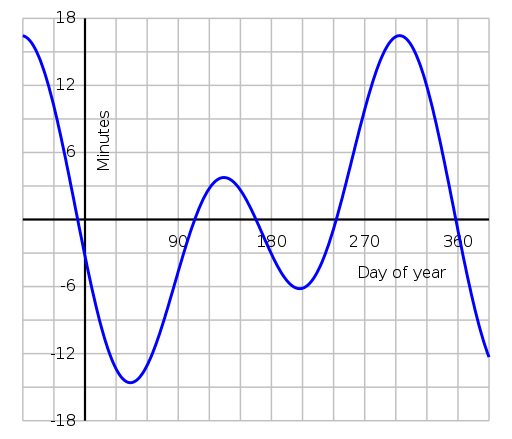

Fig. 3. The Equation of Time as it appears today. Note the four times over the course of the year where solar time and sundial time align.

Fig. 3. The Equation of Time as it appears today. Note the four times over the course of the year where solar time and sundial time align.In the early eighteenth century, astronomical regulator clocks were invented that used equation of time cam mechanisms that automatically converted clock time to solar time. The two-dimensional cam, shaped in such a way to embody the equation of time, would rotate once a year, with a follower that traveled around the curves.

Fig. 4. Left: A Graham astronomical regulator clock. Right: A two-dimensional equation of time cam.

Fig. 4. Left: A Graham astronomical regulator clock. Right: A two-dimensional equation of time cam. These traditional equation of time cams would not be sufficient for purposes of reconciling time in the 10,000 Year Clock. That’s because they’re designed to correct for the same analemma year after year. They do not take into account slow, long-term changes in the Earth’s rotation. These variations would scarcely be perceptible over the lifetime of a normal clock, but on a long enough time scale, such as 10,000 years, these changes would be profound, and would result in errors for purposes of timekeeping.

Fig. 5. The “wobble” of the Earth during the Precession of the Equinoxes.

Fig. 5. The “wobble” of the Earth during the Precession of the Equinoxes.The first variation in the Earth’s motion that must be accounted for is its cyclic wobble, called the precession of the equinoxes. Like a spinning top, the Earth gradually shifts the orientation of its axis, and completes a cycle after roughly 26,000 years. Today, our axis points to the North Star, Polaris. In 8,000 years, we will have a new North Star: Demeb. In 12,000 years, our North Star will be Vega.

The second variation is the fact that the Earth is slowing down by 1.8 milliseconds per day, or roughly one second per century. This is due to a number of factors, including the tidal effects of the moon, shifts in the Earth’s crusts, and changes in sea levels. If you were to synchronize two clocks 2,500 years ago, with one keeping perfect time and the other based on solar time, these clocks would be out of sync by four hours today.

Fig. 6. The moon accounts for some of the Earth’s rotation slowing down over time.

Fig. 6. The moon accounts for some of the Earth’s rotation slowing down over time.The Equation of Time Cam was built to enable the Clock to convert from local solar time to absolute time while accounting for these predicted long-term variations over the next 10,000 years.²

Fig. 7. The Equation of Time Cam.

Fig. 7. The Equation of Time Cam.But the Clock’s builders wanted to do more than simply turn a mathematical equation into its physical representation. They wanted to create an object that would be aesthetically compelling to visitors of the Clock for millennia.

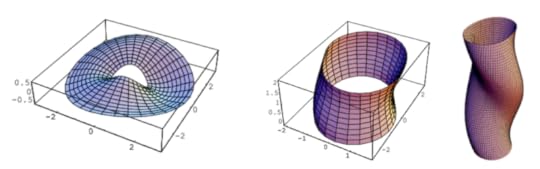

Fig. 8. The evolution of the Equation of Time Cam prototype models.

Fig. 8. The evolution of the Equation of Time Cam prototype models.“Most engineering solutions, usually the first one that someone comes up with that fulfills the engineering goal is the solution,” says Alexander Rose, who works with Danny Hillis on the Clock Project at The Long Now Foundation. “In our case, the goal of this project is not only to make the cam work but to make it a compelling object. We didn’t stop at the first one that worked, we didn’t stop at the second one that worked, we got to a third one that worked and tuned that until it was very aesthetic and interesting to hold and to look at.”

Fig. 9. The Equation of Time Cam over the coming thousands of years, with the equation of time visible at left. The cam rotates once each year, with a follower slowly moving up the cam until the year 12000.

Fig. 9. The Equation of Time Cam over the coming thousands of years, with the equation of time visible at left. The cam rotates once each year, with a follower slowly moving up the cam until the year 12000.Danny Hillis enlisted engineer Stewart Dickson to create a three-dimensional model based on his derivations of the equation of time. The Cam for the first prototype of the Clock was built using a 3D printer, and then cast into bronze. This work was carried out at The Crucible under the direction of fabricator Chris Rand. After the first one that was made for the Clock, Levenger made an edition of 365 Equation of Time Cams, most of which were given as a thank you for Long Now members at the “Equation of Time Cam” level of membership.

Fig. 10. The prototype of the 10,000 Year Clock. The Equation of Time Cam is visible in the top left, below the Clock’s face.

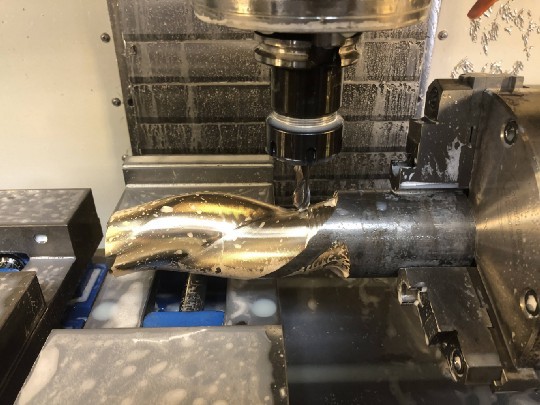

Fig. 10. The prototype of the 10,000 Year Clock. The Equation of Time Cam is visible in the top left, below the Clock’s face.In 02018, a new numbered edition of the Equation of Time Cam was created. These cams are made of bronze and entirely machined similar to the one now being made for the monument scale Clock. This next edition is available via donation on Long Now’s “Artifacts” page.

Fig. 11. Machining the new edition of the Equation of Time Cam.

Fig. 11. Machining the new edition of the Equation of Time Cam.02018 also saw the construction of the full-size stainless steel Equation of Time Cam for the monument scale clock. Compared to the prototype Equation of Time Cam, which stands at six inches tall, the full-size cam will be 10.2 inches — one inch per thousand years with a little extra room on either end. This extra room provides future engineers with a window of roughly 100 years to create a new Cam.

Fig. 12. Construction and assembly of the full-size Equation of Time Cam that will be in the 10,000 Year Clock.

Fig. 12. Construction and assembly of the full-size Equation of Time Cam that will be in the 10,000 Year Clock.In examining the question of what time was, Saint Augustine once said: “If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know.” The Equation of Time Cam ensures that the Clock of the Long Now will — for the next ten thousand years, at least — always know.

Footnotes:

[1] Absolute time, as used here, basically just means “man made clock time.” But the broader way to think about this refers to the solar system barycentric coordinate time of general relativity. As Hillis et al put it (02011): “This timescale is the independent variable in the equations of planetary motion that emerge from Einstein’s space-time field equations and metric tensor. It is therefore a direct expression of our current understanding of the space-time relationship. A defined relationship between coordinate time in the solar system barycentric frame and International Atomic Time (TAI) at a site on Earth (or Earth satellite) can be used to properly relate these timescales.”

[2] While the Equation of Time Cam is precomputed to correct for celestial variations over time, there’s one variable that potentially places a limit on the Clock’s accuracy: climate change. As noted above, rising sea levels are one factor that slows the Earth’s rotation over time. The Earth’s predicted slowdown is accounted for in the Equation of Time Cam, but calamitous climate change events could slow it down even further. In 02010, Danny Hillis requested a paper from astrophysicist Michael Busch to assess the impact of the most dramatic predictions of climate change on the Clock’s accuracy. Busch found that if the ice sheets of Antarctica or Greenland were to melt completely — which could take centuries, i.e., less than the total timespan of the Clock — it could affect when solar noon is by 37 days over the course of 10,000 years.

Learn More:

Read about how the Clock Of The Long Now keeps time with Danny Hillis et al’s “Time in the 10,000 Year Clock.”

Learn more about the Equation of Time from the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Watch Alexander Rose discuss the design challenges of building the Clock of the Long Now in a 02018 Google Talk.

Curious about how climate change could impact timekeeping in the Clock? Read Michael Busch’s 02010 paper.

What we mean by time continues to evolve, as it has for millennia. Read Charlotte Hajer’s 02011 essay on the nature of civil time.

Browse Long Now’s new Artifacts page, where the new edition of Equation of Time Cams are available via donation.

Nevada Museum of Art Launches a Piece of Art into Orbit

Earlier this week, Trevor Paglen’s Orbital Reflector launched into low orbit and became the world’s first space sculpture. “The point for me,” Paglen says in a WIRED profile, “was to create a kind of catalyst for looking at the sky and thinking about everything from planets to satellites to space junk to public space and asking, ‘What does it mean to be on this planet?’”

Watch: Videos from Whole Earth 50th Now Online

This October, hundreds gathered in San Francisco at the Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture to celebrate the 50th anniversary of The Whole Earth Catalog. Long Now was a sponsor and helped produce media for the event, which is now available online. The evening program (viewable above) featured conversations between Whole Earth Catalog contributors and contemporary wave-makers as they discussed the legacy of the Catalog and what the next 50 years might hold. Speakers included Ryan Phelan, Danica Remy, Rusty Schweickart, Kevin Kelly, Simone Giertz, Howard Rheingold, Chip Conley, Stephanie Mills, Stephanie Feldstein, Stewart Brand and Sal Khan. Select highlights from the program are viewable below.

Whole Earth Catalog contributor Kevin Kelly and robotics inventor Simone Giertz share their advice for aspiring makers:

Whole Earth contributor and social media pioneer Howard Rheingold on what makes a community a community:

Whole Earth Catalog founder Stewart Brand discusses the future of education with Khan Academy founder Sal Khan.

Stewart Brand on what his 29-year-old self would think of 02018:

More photos and videos from the event can be accessed on the Whole Earth 50th website.

Whole Earth 50th was sponsored by the San Francisco Art Institute, WIRED, The Long Now Foundation, Ken and Maddy Dychtwald, Peter and Cathleen Schwartz, Stewart Brand and Ryan Phelan, Juan and Mary Enriquez, and Gerry Ohrstrom.

December 1, 2018

The Kilogram is Dead. Long Live the Kilogram!

Last month, the standard measure for mass was redefined. Yoked to a material object housed in a Parisian vault since 01889, the kilogram will now be defined by abstract concepts in nature.

CONTEXT FROM THE ARCHIVES:

Alex Mensing, “How Much Does a Kilogram Weigh?” (02011)

Stewart Brand's Blog

- Stewart Brand's profile

- 291 followers