Doug Henwood's Blog, page 14

July 20, 2023

Fresh audio product: Bolivia vs. Venezuela, pain for pleasure

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

July 20, 2023 Gabriel Hetland, author of Democracy on the Ground, on contrasts in popular participation between Bolivia and Venezuela • Leigh Cowart, author of Hurts So Good, on seeking out pain for pleasure

July 13, 2023

Fresh audio product: French riots, US collapse

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

July 13, 2023 Harrison Stetler on the riots in France • Peter Turchin, complexity theorist and author of End Times, on why the US is heading for a smashup

July 6, 2023

Fresh audio product: austerity & fascism, AMLO’s presidency in Mexico

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

July 6, 2023 Clara Mattei, author of The Capital Order, explores the links among neoclassical economics, austerity, and fascism • Edwin Ackerman, author of this article, looks at AMLO’s presidency in Mexico

June 29, 2023

Fresh audio product: the Wagner uprising in Russia, the Confederate disapora

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

June 29, 2023 Anatol Lieven, Eurasia director of the Quincy Institute, on Prigozhin’s aborted uprising in Russia and Putin’s status • Samuel Bazzi, co-author of this paper, on the effects of the white migration out of the South after the Civil War on the recipient areas

June 28, 2023

Neoliberalism right and left

This is the text of a talk I gave at New York City DSA’s Night School, June 27, 2023. This was the concluding session of a series, Socialism in America, organized by the chapter’s Political Education Committee, of which I’m a member. Also speaking: Raina Lipsitz and Jamie Peck. The graphics were shown as slides during the talk.

Neoliberalism is a funny word. True, it’s often used as an epithet by people who don’t really know what it means, which makes it easy for proponents to deny the label. It’s curious how often those proponents deny the affiliation; it’s almost as if it’s as disreputable as being accused of being an Ed Sheeran fan. Sophisticates—and I used to be one of them—often dismiss it as a fancy but pointless neologism for capitalism. An old friend was on Twitter the other day calling the name a conspiracy theory, which he thought was a dismissal, but the evolution of the doctrine did have aspects of conspiracy about it.

So, what does it mean?

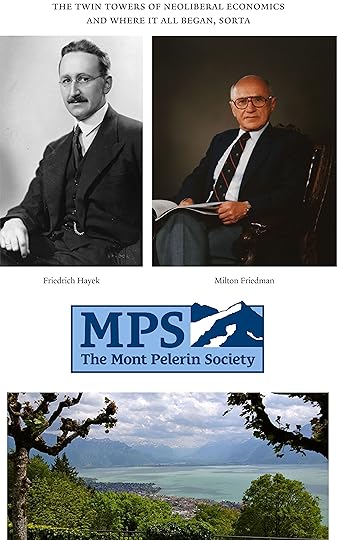

The term itself goes back more than a century by some accounts, or to 1938 by others, and the school of thought has deep roots, but it’s best to think about it as descending from the first meeting of the Mont Pèlerin Society (MPS) in Switzerland in 1947, a group of thirty-nine people selected by the notorious Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek. The end was the reversal of what they saw as a long slide towards socialism (or, in the US, New Dealism), and the means would be intellectual agitation. The model that developed was a consciously hierarchical one: peak intellectuals like Hayek would do the heavy thinking, which would then be distributed by think tanks and then picked up by journalists and politicians. The distribution process has often been assisted by fake grassroots organizations, funded by capital or its philanthropists, with preposterously deceptive names like Citizens for Free Choice in Medicine, or Energy, or whatever the particular issue.

As Burton Yale Pines of the Heritage Foundation, one of neoliberalism’s principal think tanks, put it back in the 1980s: “Our targets are the policymakers and the opinion-making elite. Not the public. The public gets it from them.” That hierarchical distribution model was adopted by Charles Koch—the brains of the reactionary brotherly duo—with great success. Calling this a conspiracy evokes the tinfoil hat problem, but it certainly has some aspects of one.

what it all meansAs for what it all means, a few things stand out. It’s not a comprehensive rolling back of the state in favor of the market, as some colloquial definitions would have it. Since its rise to political power starting in the late 1970s—in the US, the march towards deregulation began under the Carter administration—it’s been promoted and enforced by the state. By the state I mean not just national governments but also multinational bodies like the IMF, World Bank, and World Trade Organization. As Quinn Slobodian, one of neoliberalism’s leading scholars, points out, “the founding text of the WTO in 1994 was more than 30,000 pages of agreements, annexes and legal decisions, and understandings.” That really doesn’t sound like a rolling back of the state.

Rather than a comprehensive withdrawal of the state, as Slobodian puts it, neoliberalism is characterized by “the legal encasement of markets rather than their liberation,” “to inoculate capitalism against the threat of democracy.” The Market, cap-M, is central to neoliberalism, but it requires lots of political support.

Markets as we know them aren’t spontaneous forms of human organization that are stifled by states; they’re brought into existence and sustained by political action. We saw all that very clearly with the end of Communism in the late 1980s and early 1990s: market relations in those countries were birthed under the supervision of Western governments and official organizations (including one created expressly for that purpose, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development).

The original Mont Pèlerin gang was quite consciously not promoting the old-school, 19th century small-government laissez-faire liberalism: they knew that the hand of the state had to be heavy if they were to get their way. As Michel Foucault put it in 1978, in a book on neoliberalism that, in characteristically Foucaultian style, never quite commits to the doctrine but flirts energetically with it, “Neoliberalism should not therefore be identified with laissez-faire, but rather with permanent vigilance, activity, and intervention.”

OG neoliberals also thought that government would have to break up monopolies to ensure competition, provide a legal system to enforce contracts, create a stable monetary order, invest in education, and maybe even fund a modest welfare state or means of basic income support. Milton Friedman, who was at the Society’s founding meeting on his first trip out of the US, recalled Ludwig von Mises, Hayek’s mentor and one of the founders of Austrian school of economics, storming out in a fury, denouncing the attendees as a “bunch of socialists.”

For Hayek, the central role of the market was as a giant decentralized information processing system. Central planners could never have a comprehensive view of the needs of a complex economy, whether for raw materials or workers or finance or consumer preferences, because there are too many things to know, and they change over time. The point of competitive markets was to work those things out. (Modern computing and communication equipment may well have changed this, but that’s a topic for another conversation.) This information-processing function must be protected from political intervention, lest distortions and inefficiencies arise. Inequalities will inevitably result, but to put it crudely, that’s because some of us are better than others and there’s no point in trying to deny that. The conception is fundamentally antidemocratic, which is why we found Hayek and Friedman defending the Pinochet regime in Chile. Neoliberalism may have sold itself to the public as promoting freedom of choice and rolling back the nanny state, but the inner circle knew better, that democracy was nothing but troublesome.

problems of democracyDemocracy fell into broad disrepute among elites in the 1970s. In 1971, future Supreme Court justice Lewis Powell wrote a famous memo for the US Chamber of Commerce that worried about “the Communists, New Leftists and other revolutionaries who would destroy the entire system.” He worried even more about the spread of antibusiness attitudes in previously respectable realms like academia, the media, and churches, and among intellectuals, artists, and even politicians, and lamented the passivity of business in the face of these existential threats and urged a massive mobilization by capital to make a fundamental case for its legitimacy.

Four years later, the Trilateral Commission—an organization founded in 1973 by David Rockefeller to promote unity among the ruling classes of the US, Western Europe, and Japan—issued a report called The Crisis of Democracy, co-written by a trio of academics, one American, one French, and one Japanese. (The American was Samuel Huntingon, who would later become additionally famous for his “clash of civilizations” theory of post-Cold War conflict, the stars of which would be Islam vs. the “West.”) It worried among other things about an “excess of democracy” in the US (its phrase, not mine). To the authors, the proper functioning of a democracy requires “some measure of apathy and noninvolvement on the part of some individuals and groups” (their words, again, and “the blacks” were explicitly named), an arrangement that the uprisings of the 1960s and early 1970s undermined, thereby posing the “danger of overloading the political system with demands.”

The critique fit nicely with ruling class anxiety about inflation, declining profitability, crappy financial markets, and the erosion of US imperial power in the 1970s. Elites were ready to put some Mont Pèlerin theory into practice.

political taxonomiesThough you sometimes hear neoliberalism identified as a conservative policy, it’s not really, at least by conventional taxonomies. The word entered US political discourse in the early 1980s to describe a business-friendly, tech-worshipping reaction against the New Deal/Great Society inheritance within the Democratic Party. Its major proponents were politicians like Colorado Senator (and romantic adventurer) Gary Hart and journalists like Charlie Peters of the Washington Monthly. It was an idiosyncratic usage and fell out of favor even as it became the dominant strand in the party.

While neoliberalism enjoyed its earliest political victories in the 1980s under conservative figures like Reagan and Thatcher those were consolidated in the 1990s under center-left figures like Bill Clinton and Tony Blair. It’s sometimes said—including by Thatcher herself, though I heard it in an interview I did with her economic adviser Alan Walter in 1994—that Thatcher’s most lasting achievement was the transformation of the Labour Party from a quasi-socialist formation into a business-friendly one. You could say something similar about Reagan and the Democrats (though they were never even quasi-socialist).

Not that they weren’t already on the neoliberal path however. In the US, the first shots of the neoliberal revolution were fired by Jimmy Carter, who deregulated transport and appointed Paul Volcker chair of the Federal Reserve in 1979. (A number of Trilateralists worked in his administration too. Huntington, by the way, was a Democrat too.) On taking office, Volcker (yet another Democrat) said the American standard of living must decline and he made it happen by driving interest rates up towards 20% and causing a deep recession. Reagan took office in 1981, cut taxes on the rich and social spending on the poor, and fired the striking air traffic controllers, signaling to employers that it was open season on labor.

As in Thatcher’s Britain, Reagan got the ball rolling, but Clinton and Blair kept it going. A couple of decades of this transformed the common sense of the masses, from expecting some benefits from public policy to expecting nothing.

There was some interesting quasi-leftish action on the other side of the world, notably by New Zealand’s Labour Party finance minister in the 1980s, Roger Douglas, who traveled the world preaching the doctrine; his country was a site of some of the most extreme neoliberalization in the world. (For the story, see Jane Kelsey’s The New Zealand Experiment.) His bigger neighbor across the Tasman Sea, Australia, was heavily neoliberalized under the leadership of Paul Keating, a Labor Party politician who served as Finance Minister and then Prime Minister. In Europe, Felipe Gonzalez of the Spanish Socialist Workers Party and Gerhard Schröder of the German Social Democrats did a lot of neoliberalizing work. In a 1992 interview in Forbes, Friedman more or less endorsed Clinton over H.W. Bush (“very close to a disaster”), suggesting that Clinton might have a better economic policy, because some of the most radical marketizing reforms have been “left-wing governments,” like those in Australia, France, New Zealand, and Spain.

Neoliberalism got turned into a formula in the 1990s, which is how many people have come to think of it. The most famous example is economist John Williamson’s ten-point program, known as the Washington Consensus, to be applied to poor countries under IMF and World Bank restructuring programs. (Continuing a theme, Williamson worked for a thinktank, the Institute for International Economics, founded by a former Carter administration official.) Cut budget deficits, liberalize finance (indeed, financialization is often named as one of its defining features), open up trade and cross-border investment (“globalization”), privatize state-owned enterprises, secure property rights, etc. etc.

The list is a reminder that in what used to be called the Third World, neoliberalism was imposed during the debt crisis of the 1980s, as debtor countries, desperate for finance, were forced to follow the prescriptions summarized in Williamson’s famous list. Structural adjustment programs they were called, and the came by the score throughout the decade. The poorer countries were driven into crisis because the debt they assumed in the 1970s (out of a mix of necessity, economic ambitions, and corruption), when interest rates were low, became unbearable when Volcker’s high interest rate policies drove up the cost of servicing it. It was political blackmail on a global scale and from the point of view of the creditor countries, with the US in the lead (and with many elites in the debtor countries playing along), highly successful.

Neoliberalism has been pronounced dead almost as many times as Marxism, but the thing trudges on. It’s certainly not incompatible with the right-wing movements that have arisen in Europe over the last couple of decades, whether we’re talking about Italy under Berlusconi or Meloni, or far right movements like the Alternative für Deutschland or Austria’s Freedom Party. All are firmly neoliberal in economic policy. A branch of the Brexit movement dreamed that leaving the EU would throw off the collectivist yoke of Brussels and allow Britain to return to the glory days of Margaret Thatcher. Among the core MPS neoliberals themselves, there’s been no shortage of white supremacist thinking, whether it was sympathy for South African apartheid (Wilhelm Röpke, present at the creation in 1947, and president in 1961) or opposition to school desegregation in the US (James Buchanan, president 1984–1986). Also in the US, neoliberal economists have allied with traditional values reactionaries because they understand that a generous welfare state undermines the power of the conventional family, and that welfare state cuts reinforces it. Though he talked a lot of shit, Trump did little to undermine neoliberalism. You could argue that Biden’s industrial policy—infrastructure investment, the CHIPS Act—is a move away from neoliberal orthodoxy, but much of it is about using public funds to leverage private money, as they say, so it’s not really a serious rupture. It’s up to us to wreck it.

neoliberal oppositionI had planned to talk more about the experience of being a socialist amidst the antiglobalization struggles of the 1990s and more recently around Occupy Wall Street, but I got carried away with the neoliberalism part. (The links in the last sentence are to a couple of pieces on those subjects I wrote for Jacobin.) The two topics do share a curious affinity, however. Much of what passed for oppositional politics before the re-emergence of socialism in American political discourse was, strangely enough, not entirely at odds with Friedrich Hayek’s worldview. It was deeply suspicious of centralization and very much in love with spontaneous, unplanned order. But it lacked the cunning and strategic sense of the Mont Pèlerinites, given the activists reluctance to dirty their hands too much with real world concerns.

Master narratives—generalized stories about progress or the class struggle—were deeply out of fashion, and to most of the antiglobo movement—few of whom had actually read Lyotard’s obituary for them in The Postmodern Condition—socialism was one of those. Master narratives crushed particularity and led to grandiose accumulations of power that prepared the ground for police states and gulags. Conclusions could be no more than provisional, and presuming to speak for others was not merely rude but almost totalitarian. As my late friend, the organizer Joanne Landy, confessed to me after one of the many conferences the antiglobalization movement was organized around, “I’ve been a socialist my whole adult life but I’m afraid to say the word aloud.”

The Seattle-era left was heavy with philanthropists and the NGOs they funded. Critiques of capitalism were largely over size and style, never critiques of it as a social system. “Globalization” was identified as the major problem, a word that always sounded like an evasive euphemism for capitalism and imperialism, but those concepts were shunned as hopelessly antique. If you pointed out the euphemizing, you were red-baited.

The old and homey ways of doing things were mourned. Despite the presence of people from all over the world, no one thought much about internationalism from the left.

That was the drift of the official events. To the left of those events were anarchists, many of them anti-capitalist, but their refusal to talk about a new system was embedded in the “anti-” prefix. They were more into action than thinking about strategy or goals anyway.

For a sample of the ideology of the time, let me turn for a moment to David Korten’s book, When Corporations Rule the World. The movement wasn’t big on theory, but Korten was a regular at conferences and the book was often cited as authoritative by partisans. As the excerpts in the graphic show, Korten’s ideal was a small-scale, localized capitalism. (The words “Marx” and “socialism” barely appear in the book; they didn’t even merit a critique.) To Korten, late 20th century capitalism was a betrayal of Adam Smith’s admirable vision that inhibited the self-adjusting mechanisms of a truly free market. It’s not clear the world Smith described ever really existed, and it’s quite clear that small-scale local firms could never produce advanced industrial goods at all, but these sorts of questions never troubled this crowd. Nor is it clear how revering owner–managers, as Korten does, would ever address the issues of class society; it doesn’t matter how local they are if they live large on the hill and the workers in cramped circumstances in the valley.

The movement climaxed in the mass demonstrations against the World Trade Organization in Seattle in December 1999. I was there, wrote about it, did some radio about it, and even took some pictures like some kind of glamorous photojournalist. It felt glorious and exuberant, but I was never clear on what it accomplished other than derailing the meeting (which had plenty of problems of its own), or how it fit into a larger struggle for…what? That too was never clear. It did feel good, I won’t deny that. But to ask about goals was to traffic in grand narratives, and could Stalin be far behind?

A bit over a decade later, Occupy emerged. There were continuities—the same reticence about master narratives, goals, organization, though class achieved a prominence it lacked a dozen years earlier. If there was a dominant ideology it was some sort of anarcho-capitalism, but underlying assumptions were rarely examined.

I was briefly part of a working group that was formulating “demands”—a social democratic package featuring increased public investment and greatly expanded social benefits. That approach, and the notion of demands itself, were not welcome by the consensus-makers in Zuccotti Park (the unacknowledged rulers of the process), and somehow our proposals routinely fell off the discussion agenda of the General Assembly. It was all too statist and poisoned by talk about money and budgets, which was the language of The Man.

Occupy had no vision of life beyond the parks it was occupying. There was no sense of how an economy could have been organized on its principles or how a society larger than a handful of people could be governed by consensus. And how would anyone with a job and/or family have time for all those meetings?

Nor was there any sense of how the larger world would be transformed along Occupy’s principles; there was no serious theory of social change about. Some participants saw the occupied parks as the new society in embryo, but it was hard to imagine how these autonomous zones would ever be able to feed themselves without the continued existence of money and supermarkets. But bringing up questions like this was unwelcome. It contravened the movement’s foundational reticence about goals and organization.

Things are somewhat better now.

June 22, 2023

Fresh audio product: family abolition, the cult of homeownership

Just added to my radio show (click on date for link):

June 22, 2023 slaying sacred cows: M.E. O’Brien, author of Family Abolition, on doing that and “communizing care” • Jane Chung, author of this article, on what’s wrong with our cult of homeownership

June 15, 2023

Fresh audio product: Corey Robin on Clarence Thomas

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

June 15, 2023 While other shows are getting applause for interviewing Corey Robin about his excellent book on Clarence Thomas (who is very much in the headlines these days), Behind the News was there first, as it so often is. This is a rebroadcast of a show that first ran in 2019: Corey Robin on The Enigma of Clarence Thomas.

June 8, 2023

fresh audio product: Ukraine and slavery

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

June 8, 2023 Christopher Layne, co-author of the Harper’s magazine article “Why are we in Ukraine?” • Marcus Brown on his augmented reality exhibit that evokes the eighteenth-century Wall Street slave market

June 1, 2023

fresh audio product: varieties of correctional control, challenging mainstream economics

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

June 1, 2023 Wanda Bertram of the Prison Policy Initiative talks about some underappreciated aspects of the carceral state: probation, parole, and civil commitment • Francisco Pérez of the Center for Economic Democracy on why mainstream economics is so terrible and an online course that can help civilians break through the discipline’s mystifications

May 25, 2023

Fresh audio product: rising seas meet small islands; libertarian enclaves

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

May 25, 2023 Tina Gerhardt, author of Sea Change, on the effects of rising oceans on small island nations • Quinn Slobodian, author of Crack-Up Capitalism, on libertarian enclaves insulated from democracy

Doug Henwood's Blog

- Doug Henwood's profile

- 30 followers