Doug Henwood's Blog, page 73

July 20, 2012

Credit default

Back in 2009, Justin Fox, then of Time magazine, published a book called The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall Street. I interviewed him about it on my radio show in June of that year. It’s a pretty good book, but at the time, I thought it bore an uncanny resemblance to some of the arguments I made in my book Wall Street, published by Verso in 1997. (Verso let it go out of print, so it’s now available for free download at that link.) With the publication of the book, Fox went on to become editorial director of the Harvard Business Review (HBR).

My feeling of uncanny resemblance has just gotten a strong booster dose with the publication of an article that Fox co-wrote with Harvard business prof Jay Lorsch, “What Good Are Shareholders?” In Wall Street, I argued (among other things)

shareholders provide little or no money to the companies whose stock they own, and rarely have

in fact, since the early 1980s, the flow of cash has mostly gone in the reverse direction, from companies to shareholders

stock prices are often noisy and even systematically wrong, so therefore provide no good evidence on how well managers are running firms

shareholders’ interests are very narrowly selfish, usually at odds with workers, communities, and the broader society

so, basically, who needs them?

Curiously, the Fox/Lorsch article makes a very similar argument—one, I might add, that I haven’t really seen anywhere else. My version was explicitly radical; though it engaged deeply with the mainstream financial literature, it was also larded with quotes from Marx. Theirs is not. It makes a more modest case for bringing other “stakeholders” into the corporate governance game: “boards, customers, employees, lenders, regulators, nonprofit groups.” My conclusion was somewhat different:

In other words, the modern corporation shows that production can be organized on a large scale over time and space, bringing together thousands of workers in pheonomenally productive cooperation. But these institutions are nonetheless run by and for a small group of owners and managers whose social role is peripheral or even harmful to the institution’s proper running. This contradiction, in Marx’s words, constitutes “the latent abolition of capital ownership contained within it….”

But these days, even asking the question, “What good are shareholders?” is pretty subversive stuff.

In any case, I was paid a pittance for writing Wall Street. I enjoy neither the fame nor the compensation of Harvard swells. It would be nice even to get a prominent credit for having developed an original argument, even if its full form is too radical for an august establishment organ like the HBR. To his credit, Fox acknowledges the pedigree:

this is true RT @DougHenwood: @foxjust @HarvardBiz Well damn, I asked the same question 15 years ago!

—

Justin Fox (@foxjust) July 20, 2012

But a midnight tweet isn’t enough, really.

July 19, 2012

Fresh audio product

Just added to my radio archives:

July 19, 2012 Art Goldhammer of Harvard’s Center for European Studies on the political economy of Hollande’s France • Liza Featherstone, Report Card columnist for the Brooklyn Rail, on neoliberal school reform

July 12, 2012 Enrique Diaz-Alvarez of Ebury Partners on the Spanish crisis (and the German mind) • Michael Dorsey, professor of environmental studies at Dartmouth, on Rio+20

July 10, 2012

Fresh audio product

Just posted to my radio archives:

July 5, 2012 Adolph Reed, author of one of the pieces on this Nation thread, on the crisis in labor • Yanis Varoufakis, now economist in residence at Valve Software, talks about the economics of gaming, and the anarcho-syndicalist organization of the firm

June 27, 2012

SEIU’s FFFE: a lot of expensive nothing, apparently

In my recent posts on the Wisconsin results and the dire crisis of organized labor, I argued among other things that unions must fight for the broad working class and not just their shrinking memberships if they’re ever going to turn things around. Some people who disagreed with me claimed that unions were already doing that. Example offered were the AFL-CIO’s Working America program the SEIU’s Fight for a Fair Economy. [Ed. note: I’d originally said that Working America was one word, a la high-tech branding, but it’s two. Sorry.]

So what are these things about? Veteran labor journalist Steve Early told me that the AFL-CIO’s WA scheme is a whole lot of nothing. Canvassers take down names and then—nothing. No organization, no meetings, no agenda, no consequences for anyone.

And a source (who must remain anonymous) with excellent intelligence on SEIU tells me that FFFE—which critics like to mock by calling it Fifi, much to the annoyance of its sponsors—is a “massively expensive boondoggle.” The union is spending scores of millions of dollars on a campaign with no agenda, no organization building, no “metrics” of success. Remember, this is a union that former president Andy Stern left a wreck—in debt, torn by internal conflict, its reputation severely damaged (see Early’s The Cost of Labor Civil War for details). And they’re spending big on a program that apparently has no imaginable payoff at all.

It would be nice if these folks used their considerable resources to organize and fight for stuff that matters. But they’re not.

June 26, 2012

Profitability: high, and maybe past its peak?

As every Marxist schoolchild knows, the profits “call the tune” for the capitalist economy, as Michael Roberts put it recently. He writes:

Despite the very high mass of profit that has been generated since the economic recovery began, the rate of profit stopped rising in 2011. That’s a sign that the US capitalist economy will not achieve any significant sustainable growth over the next year so so. The rate remains below the peak of 1997. But the rate is clearly higher than in was in the late 1970s and early 1980s at its trough. That can be explained by one counteracting factor, namely the record high rate of surplus value in recent years. But it also suggests that there is still a long way down to go for US capitalism before it reaches the bottom of the current down phase.

That is not how I see it. I see a rather high rate of profit that has maybe begun to roll over—but only after a remarkable recovery from the Great Recession’s lows. Despite that, however, U.S. corporations are not investing much domestically, producing a gusher of what financial theorists call free cash flow.

Everyone who plays this game does it by different rules. Many esteemed Marxist profit-watchers adjust the official stats in numerous ways, such as trying to eliminate “nonproductive” activity. While I understand the interest in jiggering the numbers, no known capitalist can see or feel the adjusted rate of profit. What they (and their shareholders) care about is the actual rate of profit, reported in cash money, relative to the amount of capital that had to be invested to gain the return.

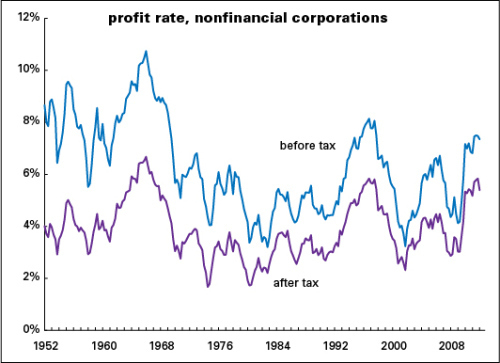

Under the rules I’ve written for myself, I measure the rate of profit by dividing the profits of nonfinancial corporations (before- and after-tax, from the national income accounts; it’s in table 1.14 here) by the value of the tangible capital stock (from the Fed’s flow of funds accounts, available here—just hit “download”). Here’s a graph of the results:

This is the long-term story I’d tell: after a peak in 1966 (coincidentally the year of the first serious credit crisis since the 1930s), the rate of profit declined hard through the miserable 1970s into a trough during the deep 1981–82 recession. But the class war from above, led by Volcker, Reagan, and the Shareholder Rebellion, succeeded in breaking labor, cutting costs, and speeding up everything. With that came a long upsurge in the profit rate, rising to a peak in 1997. This rise was the fundamental reason behind the great bull market in stocks of the 1980s and 1990s. The market kept rising after the profit peak, but then came crashing to earth. It recovered rather quickly, coming close to the 1997 highs in 2005, then turned south. Note that in both cases, 1997 and 2005, the profit rate peaked well ahead of the economy—three and two years, respectively. (Note too that the tax code became more corporate-friendly: the 1997 and 2005 peaks after taxes were much closer to 1966 levels than the pretax measure.) And the 1966 peak was well ahead of the troubles of the 1970s.

While many lefties pronounce neoliberalism a failure, on this measure it looks like it accomplished just what it set out to accomplish: raise the profit rate back to its glory days. The subsequent peaks were a little short of 1966, before everything collapsed into inflation and diminished expectations, but not by much. To say that the rate of profit stopped rising in 2011—which is quite plausible, is to underplay the sharp recovery from 2009′s depths. And given the propensity of the profit rate to lead by several years, it’s quite possible that this crappy recovery could stumble on into 2014.

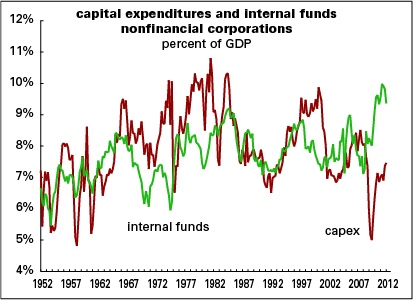

Strikingly, though you might think that with profits this high, corporate America would be investing with both hands in pursuit of more. But it isn’t. Here’s a graph of corporate cash flow (profits plus depreciation allowance) and capital expenditures:

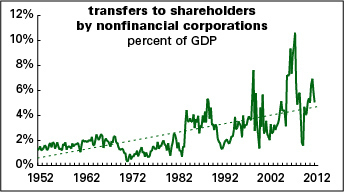

Despite the strong recovery in cash flow, to record-breaking levels, firms are investing at levels typically seen at cyclical lows, not highs. Some cash flow is going abroad, in the form of direct investment, but still you’d think returns like these would encourage investment. Instead, they’ve been shipping out gobs to shareholder. Here’s a graph of what I call shareholder transfers (dividends plus stock buybacks plus proceeds of mergers and acquisitions) over time:

Though not at the preposterously elevated levels of the late 1990s and mid-2000s, transfers are at the high end of their historical range. Instead of serving the textbook role of raising capital for productive investment, the stock market has become a conduit for shoveling money out of the “real” sector and into the pockets of shareholders, who besides buying other securities, pay themselves nice bonuses they transform into Jaguars and houses in Southampton. Is this a decadent phase of American capitalism, where its owners choose to liquidate rather than accumulate?

Profit may call the tune, but it doesn’t necessarily guide the choreographer.

June 21, 2012

Fresh audio product

Just posted to my radio archives:

June 21, 2012 Yanis Varoufakis, now economist in residence at Valve Software, on the Greek elections and the reasons for German Sturheit • Amber Hollibaugh, co-director of Queers for Economic Justice, and Kenyon Farrow, former director of QEJ, on the New Queer Agenda

June 18, 2012

From the vault: money and the mind, a psychoanalysis

[Related topics came up earlier today on the Facebook, so I thought I’d post this excerpt from my book Wall Street (Verso, 1996/1997). You can download the whole book for free here.]

Money, mind, and matter: a psychocultural digression

Money is a kind of poetry.

— Wallace Stevens (1971, p. 165)

Who drinks on credit gets twice as drunk.

— Turkish proverb

One virtue of Keynes’s attention to psychology and sentiment is that it forces us to think about economics in a way that most economists find squishy and unscientific. This narrowness of vision has harmed the dismal science immeasurably.

Credit is money of the mind, as James Grant (1992) put it in a book title, though of course every now and then mental money faces an unpleasant coming to terms with matter. Still, in these days of multibillion dollar bailouts, it seems that mind can sustain fantastic valuations for far longer than ever seemed imaginable in the past.

We might date the modern credit culture’s beginning to the severance of paper currencies from gold in the early 1970s. It waxed during the 1983–89 binge, waned during the 1989–92 slump, and waxed again starting in 1993. At its root, it’s based on the assumption that a munificent river of liquidity will flow for all time. Someone will always be willing to take an overvalued asset off your hands tomorrow at a price comfortably higher than today’s. Two famous axioms from apostles of credit illustrate this faith. In the late 1970s, Citibank chair Walter Wriston, a promoter of Third World lending, rebutted skeptics with the argument that “Countries don’t go bankrupt” (quoted in Kuczynski 1988, p. 5). Last decade’s chief debtmonger, the junk bond supremo Michael Milken, used to argue in the days before his incarceration that capital isn’t a scarce resource, capital is abundant — it’s vision that’s scarce (quoted in Bruck 1988, p. 272).

This credit culture is a long way from that described by a 19th century Scottish banker, G.M. Bell, who thought his colleagues to be finer moralists than clerics:

Banking establishments are moral and religious institutions. How often has the fear of being seen by the watchful and reproving eye of his banker deterred the young tradesman from joining the company of riotous and extravagant friends…? Has he not trembled to be supposed guilty of deceit or the slightest misstatement, lest it should give rise to suspicion, and his accommodation be in consequence restricted or discontinued [by his banker]?… And has not that friendly advice been of more value to him than that of priest? (quoted in Marx 1981, p. 679).

‘The cult of money,” wrote Marx (1973, p. 232), “has its asceticism, its self-denial, its self-sacrifice — economy and frugality, contempt for the mundane, temporal, and fleeting pleasures…. Hence the connection between English Puritanism or also Dutch Protestantism, and money-making.” In a phrase Keynes also used, it is auri sacra fames — the sacred hunger for gold.

This austerity strikes moderns, supersaturated with commodities, as quaint — though there’s nothing passé about sadomonetarist adjustment programs. But there’s another sense in which money and religion travel together — especially when money takes the form of a promise rather than a hard form of settlement, that is, when money becomes credit (from Latin, “I believe”). A credit agreement is a profession of faith by both parties: short of a swindle, both parties believe the debtor will be able to repay the loan with interest. It is a bet on the future. This theological subtlety is lost on the information asymmetry theorists, who, even as they concede the possibility of deception, don’t allow departures from rational self-interest.

For most of history, credit’s dreamier excesses were limited by gold, a metal at once seen as both “natural money” and pure enough to touch the body of Christ. Marx (ibid., p. 727):

The monetary system [i.e., gold-based] is essentially Catholic, the credit system essentially Protestant…. [T]he monetary existence of commodities has a purely social existence. It is faith that brings salvation. Faith in money value as the immanent spirit of commodities, faith in the mode of production and its predestined disposition, faith in the individual agents of production as mere personifications of self-valorizing capital. But the credit system is no more emancipated from the monetary system as its basis than Protestantism is from the foundations of Catholicism.

Money conflates the sacred and profane; it’s no accident that American currency states that “In God We Trust.”

This conflation of high and low, of matter and spirit, is enough to send a student of money to Freud. By the lights of classical psychoanalysis, money is gold, and gold is transformed shit, and exchange relations, sublimated rituals of the anus. Though this is by now a commonplace, readers found this a rather shocking thesis almost 90 years ago. Freud’s (1908) essay on the anal character began by noting the coexistence of a trio of features in such cases: orderliness, obstinacy, and thrift. Freud speculated that this unholy trinity — hallmarks of the Victorian bourgeois — spring from an infantile interest in the anus and its products. Orderliness, said Freud, gives “the impression of a reaction-formation against an interest in what is unclean and disturbing and should not be part of the body.” Obstinacy represents the baby’s lingering reluctance to part with his or her stool on command.

And the infantile roots of thrift are perhaps the most interesting of all. Freud noted the rich associations between money and dirt found in folklore and everyday language. In English, there are expressions like “stinking rich” and “filthy lucre.” In legends, “the gold which the devil gives his paramours turns into excrement after his departure…. We also know about the superstition which connects the finding of treasure with defaecation, and everyone is familiar with the figure of the ‘shitter of ducats’ [a German idiom for a wealthy spendthrift; we have our goose with its golden eggs, more fertile than fecal, but emerging from a neighboring bodily region]. Indeed, even according to ancient Babylonian doctrine gold is ‘the faeces of hell.’” Finally, Freud suggested that “it is possible that the contrast between the most precious substance known to men and the most worthless…has led to th[e] specific identification of gold with faeces.”

Freud’s early followers — notably Abraham, Ferenczi, and Jones — trod the anal path blazed by the master. The accumulation of money is a sublimated urge to retain feces for the very pleasure of it, and the production of commodities is the psychic derivative of the expulsion of feces. Money, in Ferenczi’s (1976) marvelous phrase, is “nothing other than odourless, dehydrated filth that has been made to shine.”[1]

The psychological equivalence of dirt and money is suggested by the low social status of bankers in pre-modern times. Using decidedly non-fecal reasoning, philosopher of money Georg Simmel (1978, p. 221) speculated that “the importance of money as a means, independent of all specific ends, results in the fact that money becomes the center of interest and the proper domain of individuals and classes who, because of their social position, are excluded from many kinds of personal and specific goals.” Among Simmel’s examples are the emancipated Roman and Athenian slaves who became became bankers, as did Armenians in Turkey; Moors in Spain; and Huguenots, Quakers, and Jews across Europe. Reading Simmel eighty years later, one thinks how the social prestige of banking increased along with the development of credit, that is, with its evolving liberation from gold.

Norman O. Brown, not the most fashionable of writers these days, found this psychoanalytic orthodoxy wanting. Brown returned the sacred to the analysis of money and demeaned both equally. For Brown (1985, p. 297), money and the sacred were both sublimated products of a revulsion from the body. And such sublimation, whether aimed at god or mammon, is “the denial of life and the body…. The more the life of the body passes into things, the less life there is in the body, and at the same time the increasing accumulation of things represents an ever fuller articulation of the lost life of the body.”

To Brown, the exchange relation is imbued with guilt, and the debtor–creditor relation with sadomasochism. In this, Brown followed Nietzsche, for whom all religions are “systems of cruelties” and for whom all creditors enjoy “a warrant for and a title to cruelty” (Nietzsche 1967, Second Essay, sections 3 and 5). (Modern usage confirms the link of debt with both sadomasochism and the sacred: “bonds” impose conditions known as “covenants” on debtors.) Creditors in the ancient world “could inflict every kind of indignity and torture upon the body of the debtor; for example, cut from it as much as seemed commensurate with the size of the debt.” Creditors can take pleasure in “being allowed to vent [their] power on one who is powerless, the volutptuous pleasure ‘de faire le mal pour le plaisir de la faire,’ the enjoyment of violation.”

For Brown, debt is a sickly tribute paid by the present to the past. (Of course, we postmoderns often see — consciously or not — credit as a way to steal from the future.) But for a partisan of the body, Brown was nonetheless guilty of the ancient psychoanalytic habit of dematerializing its needs. As the early analyst Paul Schilder (1976) — who rightly lamented the absence of a psychoanalysis of work — noted, “When one looks over large parts of the psychoanalytic literature one would not conceive the idea that one eats because one is hungry and wants food for sustaining one’s life but one would rather suppose that eating is a sly way of satisfying oral libido…. Silberer once said…[that] according to psychoanalytic conceptions…the Danube…is merely a projection of urine and birthwater.”

Similarly, Brown’s gold is more a fetishized projection of intrapsychic drama than an alienated embodiment of real social power. His moneyed subjects lack class, race, nationality, and gender. For Marx, what made gold valuable was that it embodied human labor and served as the universal exchange equivalent for all other commodities, whose value arises from the labor that made them. But the nature of market relations — anonymous, mathematical — is to hide the social nature of production and exchange behind the veil of money. As psychoanalysis lacks a theory of work, so does orthodox Marxism lack an understanding of the passions that sustain the disguise. With credit comes a set of passions entirely different from those of gold.

Money, Brown said, is but part of the “commitment to mathematize the world, intrinsic to modern science.” But modern science has now almost completely mathematized money. Aside from doomsayers, survivalists, and other goldbugs, the monetary functions of dehydrated filth are all but forgotten. Even paper money is getting scarce — only about 10% of the broadly defined money supply (M2). Most money now lives a ghostly electronic life.

With this dematerialization of money has come at least a partial banishment of the guilty sadomasochism of the anus. That banishment was seen at its fullest during the 1980s, when fantasy ruled the financial scene; in the early 1990s, the repressed made a partial return, and the exuberance of the Roaring Eighties seemed a distant memory. But the psychological dethronment, however complete or incomplete, of anality and guilt, has an interesting analogue in the cultural and social transformations that so trouble American reactionaries. Capitalism, having undermined the authoritarian–patriarchal family, now produces fewer guilt-ridden obsessives and more hungry narcissists than it did in the days when gold and daddy reigned as the harsh taskmasters from whom there was no appeal. Like the narcissist, today’s consumer seems less interested in the accumulation of possessions than in the (novelty-rich, credit-financed) act of purchase itself.[2] Rather than the guilty obstinacy of the anus — or the Puritan character identified by Max Weber as the spirit of capitalism — one detects a more primitive, fickle, and eternally dissatisfied orality. In contrast with the dry, tight, fixed, “masculine” aura of gold, modern credit money seems protean, liquid, and “feminine.”[3]

Unlike the classic neurotic, whose conflicts centered around anxiety and guilt over what were seen as dangerous or forbidden desires, the modern narcissist complains most about a sense of emptiness, of disconnectedness, of a free-floating rage and anxiety attached to nothing in particular. Under a superficially well-functioning veneer, the upscale narcissist, in Joel Kovel’s (1980) words, “is unable to affirm a unity of project or purpose, a common goal, with other people in a way that goes beyond immediacy or instrumentality.”

According to Kovel, the transformations of domestic life that have occurred since the capitalist industrial revolution first gave us the authoritarian–patriarchal–obsessive personality type, only to be succeeded by the modern, or postmodern, narcissistic type. The breakup of traditional social arrangements that came with the development of the capitalist labor market meant that the scale of social life simultaneously expanded — transportation and communication making people far more mobile and informed about life beyond their locality — and shrank, as the nuclear family became the central focus of all non-work life. “Childhood” in the sense of a protected, privileged phase of life was invented sometime in the 19th century.

This child-centered, father-dominated life became increasingly penetrated, Kovel argued, by the state, the media, and the increasing power of the commodity form. The family, in Kovel’s coinage, became de-sociated. People’s lives became increasingly determined by institutions far beyond their immediate sphere of experience. Decisions about lives in New Jersey are often made by executives in Tokyo; about lives in Brazil made in Grosse Pointe and Milan. The family has effectively ceased to be a barrier against outside events, a haven in a heartless world.

A right-wing version of this analysis calls for a return to the patriarchal family, which is both impossible and undesirable. But leaving aside the issues of the politics of the household, we have to wonder how capitalism can survive this new personality type? On one hand, the system, especially its American variant, depends on credit-financed consumption to keep the wheels spinning, but on the other, the financial system can’t live indefinitely with its consequences. Central bankers and partisans of fiscal austerity can impose sadomonetarism (to steal Dennis Healey’s fine coinage), but it’s not clear that the system can bear it either economically or psycho-politically over the long term. The attempt to evade the sadomonetarist logic produces only a bizzarria of hollow prosperity, speculative bubbles, and an atmosphere of generalized irresponsibility. The attempt to conform to it provokes economic stagnation and corrosive popular resentment. This is another way of looking at the Minsky paradox.

[1]Anyone who has observed modern goldbugs knows that behind their faith often lies a deep snobbery, a contempt for “common,” debased forms of money like paper, which lack the aristocratic status of the sacred metal. Economically, they love the austere, punishing regime of a gold standard, which makes mass prosperity difficult, and hate loose money, which threatens to make prosperity more widespread than it should be. Though there is an economic point to this, the psychosocial truth is another matter entirely; while gold is certainly rarer than feces, both are undifferentiated substances; an ingot is as characterless as a turd. But, as Fenichel (1945, p. 281) wrote, the anal characters who love money love the kind that appears to be “not deindividualized; they love gold and shining coins.”

[2] Or as The Slits put it in their 1979 song “Spend, Spend, Spend”: “I need something new/Something trivial will do/I need to satisfy this empty feeling.”

[3]Needless to say, the gender contrast alludes to convention, not to timeless sexual essences.

Sam Gindin on the crisis in labor

[This is a lightly edited transcript of my interview with Sam Gindin, first broadcast on June 14, 2012. The audio is here. Thanks a million to Andrew Loewen for doing the transcription.]

My next guest is the excellent Sam Gindin. Sam is an economist who spent more than 20 years in the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) Union, first as a researcher and then as an adviser to the president. He retired from the CAW in 2000 and has since been teaching in the wonderful political science department at York University, Toronto. He frequently collaborates with another Behind the News favorite, Leo Panitch.

The debacle in Wisconsin is deeply symptomatic of the crisis in American labor, and there’s no smarter commentator on that topic than Sam, even though he lives north of the 49th parallel.

Welcome Sam. The defeat of the Walker recall in Wisconsin has prompted some reflections on the state of the labor movement. What are your initial thoughts on that? I know you’re across the border in Canada, but it certainly has repercussions across North America.

Yeah, I’m interested for the same reasons everybody else is. It has repercussions here, and also my wife’s family is in Wisconsin, so we’ve been in touch with them. The main thing is—and it’s a point that you’ve made—that we have to take a look at what happened and ask ourselves some hard questions. I’m sympathetic to people who feel like “Walker won the election through the amount of money he put in; we have to try to defend the labor movement; we have to hope that people don’t get demoralized.”

But the real thing we have to do is be honest about what’s happened. And being honest means talking about the real, serious crisis in the labor movement. And it’s a crisis that’s actually been there for at least a quarter of a century. And it was especially evident when the financial crisis happened. And instead of being able to go on the offensive, labor was on the defensive. And it was revealed again with Occupy, when the labor movement supported Occupy but what was really called for was a question of labor showing that it can occupy things and that it had the power to do things.

So this is a serious crisis. And I think we really have to be honest and step back and address the seriousness of the crisis. We have to stop talking about just the economic crisis and just how bad the rightwing is when it does all the things that we expected them to do—and actually have that kind of discussion about the labor movement.

How similar are things in Canada to things in the US? I mean a lot of people will say this is an American issue, an American problem—you’ve got American individualism, the brutality of American repression of labor activism throughout the course of the last century or so.

Of course there are differences in Canada. In some ways the attack hasn’t been as aggressive. Canada doesn’t play the same imperial role that the United States plays and that leads to some differences, but the fact of the matter is that the differences are not that great in Canada. If anything we’ve been kind of converging to that same notion: of limited options, and ‘there’s nothing you can do about this,’ and lowering our expectations so that whatever happens ‘it could have been worse,’ or the Democrats—you know, ‘you have to make a choice between whoever is worse and whoever is worser.’

So I don’t think the differences are that great here and I’d even go further: I don’t think the differences are that great generally in Europe, except for some places like Greece, where there’s been a particular kind of resistance because of how much they’ve been attacked. But I think there’s been a general crisis in the trade union movement everywhere. And I think we should talk more about ‘what is it’ exactly; but I think it’s also wrapped up with a crisis on the left, which is an integral part of this.

Some of the criticisms I’ve gotten for the things I’ve written is that, first of all, not having been an organizer myself I don’t understand how difficult things are. I think I do understand how difficult things are—but the other thing is that there’s some people who seem to think what we need to do is keep doing the same thing with increased dedication and intensity. What do you think? Is that the way out of the crisis?

No. That’s part of the problem. I respect everybody who’s feeling like they’re put upon. It is difficult, and workers have immediate struggles. But seeing this as a problem of “let’s just plug on, let’s just be a little bit more committed”—if there’s anything we should learn it’s that that doesn’t get us anywhere.

This is a really serious, radical problem. Let me just say what I think it is, and what we have to talk about. There is a problem in unions, that in their very formation they were sectional organizations, that the essence of unions is that you’re defending a group of workers. You’re not actually thinking about the class as a whole, or about other dimensions of workers’ lives. On occasion, in spite of that sectionalism, you see the potential of workers because they go beyond it, as they did when they were mobilizing in Madison. But the problem is that the structure of unions, and their culture and their logic, takes them back to returning to being very instrumental. The problem with being sectional and just thinking about yourself is you also tend to think instrumentally. You look to your leaders as—you pay some insurance for being in the union, you give them some dues, and they’ll deliver. And the leaders think in terms of “well, we occasionally have to mobilize the workers but we shouldn’t exaggerate that or really open the door to mass mobilization, because we just want to mobilize them enough to make a deal.”

That problem is fundamental to what we’re seeing in this crisis. After World War II, this wasn’t obvious, because then you could in fact make gains by being sectional. And in fact some of those gains would spread to others. The defeat after the war was the defeat of the left inside unions, and part of that was promising people that “well, you can just win things within capitalism and just being instrumental, and you don’t really need a left.” And a lot of workers accepted that.

When neoliberalism came, in the absence of a wider vision, in the absence of a left, that sectionalism was dead. You just couldn’t make gains when you’re facing not just an employer but you’re facing the state, and you’re facing the employer in an entirely different context. I don’t think the trade union movement ever came to grips with that fact. They stumbled on doing what you just raised: “well, we’ll just have to try harder, this is cyclical, it’ll get a little bit better, maybe we’ll elect somebody else.” They didn’t realize that that whole era was over and unions really had to reinvent themselves.

And then came the financial crisis, the biggest crisis we’ve seen since the 1930s. In the 1930s, unions at least had recognized the limits of craft unionism and developed a new organizational form in terms of industrial unionism. The question that was being posed by the financial crisis is: okay, what are you going to do this time? What is the new organizational form that workers might come up with, given that the organizational form that that they have, sectional unionism, isn’t capable of doing it. The public sector unions can say “we’ll put up billboards to say we support the public sector,” but nobody really believes them—they see it as opportunist.

So there’s a real question of, what might a different unionism mean? I don’t think that people who are trying to defend unions—by saying “they’re okay, don’t attack them, just plug along”—are actually doing the unions any favor. I think what really needs to be done is we have to challenge unions. And I think that was the excellent part of what you were writing about.

There’s a perception in the broad public that unions are mostly interested in themselves. The leaders seem to be very interested in their own salaries and perks, too. But it seems that the leadership thinks it has a product to sell. That product is a contract and certain privileges in wages and benefits. That seems to foster a perception among the broad public that unions just don’t care about the working class as a whole. Is that a fair perception on the part of the public?

Yes and no. If you tested the unions compared to the ruling class, to other sections of society, they might in fact be more progressive on these issues. But the reality is that it’s not enough. It’s not enough that unions might in general—that their members might in general vote more progressively, or they might care more about these things. Unions have to prove it. And you don’t prove it by passing good resolutions, and even donating some money to good causes, or putting up billboards that say we support public services. Unions have to prove it. And to prove it they have to be radically different.

So, for example, they have to consider, when we’re in bargaining maybe we actually have to put the quality and level and administration of services on the bargaining table. Unions don’t do that. In other words, we would actually be ready to strike for something that we consider a fundamental right in society. Now when you start doing that you have to educate your members differently, you have to change all your structures, your research has to be different, how you mobilize and organize has to be different. But, you know, starting to think about that would mean a radical change and a chance to actually win the public over. And when I say win the public over I actually include other unions, who are also skeptical of this, who see this as “well they just want to raise their wages, and that means raising my taxes.”

So you’ve got to win people over. And it means you have to develop a class perspective. You have to be driven by a class perspective. You can’t say “we’re organizing but the point of organizing is we want to just get more dues,” because that effects what kind of commitment you have, what kind of energy you put into it, whether you’re going to cooperate with other unions to organize people even if you don’t get them. If you have a class perspective you’d have a different take on unionization—you have to deal with this question of, “Hey, wait a second, we’re saying that we support the public but then we go on strike and take away the service, isn’t that a contradiction?” You have to start thinking about, “Well, maybe we have to do other things, so that when we really go out on a full-scale strike people will get it.”

And by other things I mean such as if it’s a garbage strike, and they’re asking you to drop the garbage off in a park while the strike is on, maybe you drop it off on Wall Street, because you want to make a connection between austerity and the strike. Maybe you actually think about—we’re not going to pick up garbage in rich neighborhoods because we want to make that connection. We’ve had examples of workers coming up with that sporadically, but the problem is it’s only sporadic. It has to get to what the organization is actually about.

I should say, I don’t know that you can transform unions as they are to being more than that. But I’ve been trying to think through what it might mean to think about intermediate organizations. By an intermediate organization I mean something that would be a new form of working-class organization, that would see workers as joining them, linking them across unions. Having networks of activists across unions, so it isn’t just a union with a sectional interest, but it’s workers joining something because they see it as a class interest, and that it also expresses all the other dimensions of their lives. So it’s linked to the community.

So it’s not a political party but it is explicitly trying to take on the question of class and educate around the fact that unions face systemic problems that are more than facing a particular employer.

What do you make of the fact that something like a third of union members voted for Walker?

I think there’s a division between the public and the private which is part of that, with people being won over to isolating the public sector. But it completely reflects the fact that if unions are only instrumental, sectionalist organizations, and then people are voting on the basis of “does this help me in particular, even if it screws other workers?,” with no sense of if you’re screwing other workers how that might come back to bite you in the longer term perspective. If you accept the fact that, well look, in practical terms I do want to support business because the only model we have for growth and therefore for financing public services is to support business, then workers can make a very sensible and rational decision that this is best for me given that there’s actually no alternative. No one’s talking about challenging business. No one’s talking about an alternative way of creating jobs that isn’t just some stimulus, but is actually thinking about questions of planning and conversion.

So I think that as long as people have a limited perspective on how you define the problem that shouldn’t surprise us. And the reality is that unions don’t see their role as developing that kind of a broader perspective, for the longer term. My argument would be that that kind of narrow perspective which worked in the past isn’t even actually practical anymore. It’s not that you can make an argument that “well it’s practical to just be small.” That’s what we find out is impractical. You lose your own members. They see the solution not working. And we have to start thinking bigger and more radically, because that’s the only thing that’s practical right now.

That would a revolution inside unions—a massive cultural change. And I don’t think this can happen without a left that is both inside and outside the unions, pushing this kind of thing and getting unions, even if you don’t win them over, but getting them to at least put on their own agenda strategic questions about “how should we respond?”

If you think of the Wisconsin uprising, there should have been some structures formed as this was happening, like assemblies. Where people are actually discussing things. What do we do? How do we get neighbors on side? What do we when they say this? How do we answer these questions? How do we get into the high schools and develop people because is this is going to be, you know, we’re talking about another generation that’s going to be affected. When that was ignored, and everything just got channeled into an election—which at this point you’re simply operating on their terrain—yeah, the end result isn’t that surprising. And you’re not really building things.

You can also ask the question well what would’ve happened if unions won? In these circumstances even if unions won, it would’ve been a very important victory in terms of bargaining, but the Democrats would’ve been there to make sure that you have bargaining but that you couldn’t bargain over anything significant. They would’ve reinforced that image. I mean the main thing that the Democrats did in this election was run away from actually speaking about class, defending workers, defending unions, and thinking that you could win just by demonizing the other side. So there wasn’t even that kind of education and buildup during the election.

When you say things like this a lot of union people say, “Yeah that’d be very nice but we operate under a very severe set of legal constraints. We can get fined, we can go to jail, we can be destroyed. So we just have to operate by some rules that are very much stacked against us.” What do you say to that?

Part of the problem is people not knowing their own history. Unions didn’t come out of people sitting down and practically saying, “what are the rules, what are the constraints, and how do we operate within them?” They figured out how you actually have to break rules, how you have to change them, how you have to mobilize broadly. When you look at these problems in very small ways, like workers saying, “If I just walk out of my workplace, I’ll be fired”—yeah, you will be fired, so you shouldn’t do that. But you should figure out what would we have to do so we actually have a mass base. How do we build that base?

They showed that in Wisconsin. They were sitting in on the legislature—a massive act of defiance. All the things that we cheer when they happen elsewhere are acts of defiance. Everything about our history was an act of defiance. That requires being sober about it. It’s not just romantic. Let’s do it—it actually means asking, ‘If we can’t do certain things now, how do we prepare so that we can do them?” It does mean saying that if you want to change things, these are the kind of risks you have to take. How do we prepare ourselves to take those risks and pull it off?

Because if you accept the status quo then the thing you have to remember is that you’re not just protecting yourself right now. You’re sending a signal to them that they can keep doing it to you. And that’s what’s been going on for the last quarter of a century. You know, first they lower expectations, then you have the crisis, so then now you have to pay for the crisis and bailing out the banks. Now you get defeated. What’s going to come out of this Wisconsin thing is that there are going to be further attacks on workers in other states, and workers will be relieved because they weren’t as bad as what Walker was promising.

This is going to keep going on; it’s going to get worse. There’s no future in it. There’s no future in it for people’s kids. People have to start thinking in terms of: you have to take a stand, you have to think about what this means, and you have to prepare for it. And it is going to be risky. Everything that you raise should be addressed, you know, right on, instead of pretending that if you do these things it’ll be easy.

You’ve also said that the labor movement needs a left and the decay of the left has really damaged the labor movement. Could you elaborate on that?

It’s really difficult for me to imagine unions being transformed completely through their own dynamic. We just haven’t seen it happen. We’ve seen attacks on unions consistently now since the early eighties. And we haven’t seen bad times leading to something new. People just lower their expectations and hope that if there’s a crisis you just fix it so you can get back to what was normal before, even if that wasn’t so great. The leadership have no pressure on them to change. In fact, a lot of them have learned that since nobody blames them, maybe it’s more comfortable to be able to blame big money, or globalization, or neoliberalism. The leadership has gotten comfortable—and the membership finds it very hard to rebel when you’re looking at the world from one particular workplace and you don’t have connections to others. You know your leaders are worldly; they travel around; they know what’s going on in other places. But the workers are overwhelmed in terms of time, so it’s very hard for me to imagine that kind of rebellion.

What a left has to offer is making connections between people across workplaces, bringing in a class analysis so they seem it’s not just them. They can never win if it’s just a few of them against the state. They have to see there’s actually a class involved here. Giving them some alternatives, you know, giving them some historical memory, so they see how workers did this—in fact in more difficult circumstances in the past. Giving them some comparative analysis of what’s going on in Greece and elsewhere—how did people organize. So the left can play that role, in terms of bringing a class perspective, resources, memory into the picture. The truth is the left that we have now isn’t capable of doing that. So I think one of the questions that comes out of Wisconsin is not just “what’s wrong with unions?,” but “what kind of a left could actually do that?”

And the answer to that isn’t that we’ve got to convince workers that the politically right thing to do is to go into the Democratic Party. Because that will not develop capacities. In fact, it constrains the development of working-class capacities.

Some practical types would listen to what you just said and say, “well that’s all very nice but, you know, it’s too highfalutin’. We need some action on the ground. And all this stuff about making connections and international comparisons and class analysis is just over-intellectualizing what needs to be a much more activist approach to the problem.” What do you say to that?

At one level of course they’re right. The point of organizing isn’t that you phone up a worker and you say, “Hello, I’m so-and-so. I think we need a revolution and we need a class analysis and can you come and join me?” That’s not how people get organized. You do have to be on the ground. But you have to be on the ground in a way that has a class perspective behind it. If you’re talking about organizing and you’re thinking in terms of class, one of the questions is, “If there are so many people being laid off, what are unions doing about their members who’re being laid off?” If they can’t even organize people who were just recently their members, how would you expect them to organize anybody? And the reason they don’t do that, is because there’s no money in it.

There’s money in getting new members but there’s no money in helping your members once they stop paying dues. But if you have a class perspective it leads to something else. It leads to actively organizing the unemployed that were formerly your members. And if you don’t do it that’s where you get a lot of the rightwing populist response that you mentioned earlier. Workers say, “Well, they cared about me when I was paying dues; they don’t give a shit anymore.” And they don’t end up being very sympathetic to labor. That’s very on the ground.

If you’re talking about making a breakthrough and organizing homecare workers, who do exactly the same thing as homecare workers in institutions that are unionized do but do it privately, you have to get cooperation among unions. It would be a massive project. And if you got cooperation, it’d be a very on-the-ground, hands-on response to organizing low-paid, immigrant women. It’s very concrete. But to do that you’d need this cooperation among unions. And you’d actually have to talk about, “What kind of a union do you want, where does class fit in, why are you doing this?” And if you don’t want to talk about that you won’t do it. This notion of ‘let’s just go out and do it the old way and it’s on-the-ground’—that’s what I consider really idealist. It’s not working! You do have to think bigger.

That’s part of the role of the left: it’s to be a bridge—responding to practical and immediate things, but putting them in that kind of a larger context. Because without that kind of larger context we’re losing and we’re going to continue to lose. What’s really abstract is pretending that these kinds of questions don’t matter.

Is there really any hope for a model in which the goal of union activity is organizing a group of workers to get a contract and then have them pay dues for union membership? This is the central model of American unionism. Could this survive another generation, or has this got to go?

I don’t know if it has to go. But we need another kind of organization, which doesn’t mean this one has to go. It might mean that if we in fact had workers’ assemblies and spaces and places where workers were actually mobilizing and organizing around class, that might begin to have an impact on unions. Injecting that into unions might actually demonstrate to them that you actually need some kind of strategic thinking to even be effective at what you’re trying to do. So it may be that there’s a way of renewing unions—but only because you’ve actually responded to the times, and learned something, and said, “We need new forms of working-class organization.”

I just got back from Montreal. It’s fascinating because it’s one of those moments where in retrospect you can say it was predictable—there was a lot of student organizing and mobilizing before. But they’ve had marches of around 300,000 people. They’ve been fighting around the cost of tuition. Quebec has the lowest cost of tuition in the country and yet they’ve been fighting around it because they think it should be a public good that’s free. So what recently happened is they began to actually go into neighborhoods, banging pots, and what’s happened is neighbors have come out to join them. Nobody would’ve predicted this. They would’ve thought they’d be, you know, isolated as spoiled university kids.

You begin to see that once people begin to see that something’s possible, it opens everything. There are people on the streets supporting them. People in the bars run out and join the demo, There are all kinds of discussions taking place. People are actually talking about capitalism, because they’re being forced to as they do this. And the students have been running assemblies—democratic spaces in every university, in different faculties, to make decisions about where to go and what to do and about tactics. And then this is now being imitated to some extent in some of the communities, where people are forming community assemblies to talk about broader issues. Not just tuition fees but the educational system or why there are cutbacks. As struggles take place, you get surprised and things emerge. Then the question is well what do you do next to sustain it?

If you’re sober you have to be pessimistic. But there’s a quote that’s usually attributed to Gramsci—I don’t know if he actually said it—that the challenge is to have no illusions but not get disillusioned. That’s the trick. It’s just one of those historical moments where we have to figure out how to do something. If you think of the periods since The Communist Manifesto it’s always been as if there were some answers that somebody had: unionization, insurrection, forming communist parties, forming social-democratic parties.

Now we have to come up with our own answers because those answers weren’t real answers. It’s very difficult to live through this period because there’s no answer on any shelf to take, and we don’t have an example abroad to say why don’t we just do it like so-and-so.

It’s an incredibly difficult period, but I think capitalism has really been delegitimated. I don’t have any trouble talking to workers, telling them that capitalism is a barrier to human development. They nod their heads. They’re just not sure how to change it or have confidence in changing it; but it does mean that there’s an opening if we can organize and figure out how to organize and take advantage of it. And that’s a difficult challenge. It is crucial that we take our heads out of the sand, stop pretending that if we just keep trying, and defend workers, that things will change. That’s actually becoming a barrier to change. I say that with real respect for the fact that while you’re doing this of course all kinds of struggles are going to take place, and of course we should support them. But we should also be pointing to their limits.

June 10, 2012

My chat with Adam Davidson

My latest radio show, a long chat with Adam Davidson, is up in my radio archives:

June 9, 2012 Adam Davidson, host of NPR’s Planet Money and columnist for the New York Times Magazine, on finance, innovation, bourgeois ideology, journalism, and being mean on the Internet (a conversation that was prompted by this piece of mine) [Davidson columns discussed include: Wall Street, Bain dude, Honduras]

•

full conversation (unedited, except to remove some patter at the beginning and to suppress several volume spikes) is here

June 7, 2012

Sam Gindin comments…

The excellent Sam Gindin, who spent many years with the Canadian Auto Workers as an economist/advisor (and who cannot be dismissed as some armchair pointy-head), writes in response to my recent stuff on Wisconsin:

Very good response; I think you are right on re labour. The one thing I’d add, and I think it is very significant, is that this crisis in labour overlaps with the crisis on the left. I’m convinced that any renewal in labour won’t happen until there is an organized left with feet inside and outside labour—and even then it would have to be a left of a particularly creative kind. Which raises the unavoidable question of what we do to create such a left if neither the unions nor the democratic party are sites to make this happen and the notion of this happening through the old Leninist structures seems no less of a dead-end. THIS is the challenge that needs taking on….

I like this very much, and I don’t think it’s just because I’m flattered. I love the bit about an organized left that’s both inside and outside labor.

Doug Henwood's Blog

- Doug Henwood's profile

- 30 followers