Doug Henwood's Blog, page 70

December 14, 2012

Capital drought

U.S. corporations are flush with cash. As of the end of the third quarter, they had $1.8 trillion in cash, bonds, and other liquid financial assets on hand—and I’m talking about nonfinancial corporations, not banks or insurance companies. Profits are very high, and firms are gushing with cash flow. But they’re not investing all that much—in things, that is, like buildings and machines. Usually, corporate capital spending tracks closely with cash flow (profits plus depreciation allowances). Firms typically invest all their cash flow, and very often more (borrowing the difference). Over the long term, in fact, capital expenditures have slightly exceeded cash flow by 0.2% of GDP

Not lately, though. Since the economy bottomed in 2009, cash flow has exceeded real investment by 2.6% of GDP. Just as firms are reluctant to hire new workers, they’re reluctant to spend their plentiful cash on expanding operations.

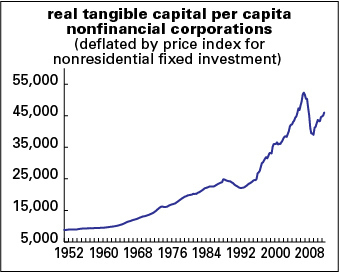

The reluctance to invest comes on top of a sharp cutback in capital spending during the recession. Along with all these numbers I’ve been quoting, the Federal Reserve, in its flow of funds accounts, provides estimates of the total capital stock—a dollar valuation of buildings and equipment owned by the corporate sector. Graphed below is the real value of that capital stock for the nonfinancial corporate sector per capita.

It fell by over 25% during the recession. It’s recovered some since, but remains about 12% below its 2007 peak. We’ve never seen a comparable pattern—sharp decline, weak recovery—since these figures began in 1952. There was a more modest decline between 1988 and 1992, but it was quickly recovered.

This weakness in the capital stock is bad for current growth—if corporations were investing all their cash flow, they’d be spending $300 billion more than they are now, which would add almost 2 points to GDP growth—but also bad for the future. Weak capital stock growth means weak productivity growth, and weak productivity growth guarantees weak income growth for the masses if it’s drawn out over the long term. (Yes, strong productivity growth doesn’t guarantee strong income growth; it could just mean higher profits and higher upper-bracket income. But low productivity growth guarantees low income growth.) According to the textbooks, high profitability and juicy cash flow should encourage investment. But they’re not. Instead, managers are hoarding their cash—the cash that they’re not shipping out to shareholders via dividends and buybacks, that is, a flow that is at near-record levels. (Things haven’t changed much on the shareholder score since this.

The managerial class loves to talk about itself as bold and risk-taking—characteristics which are supposed to justify all that money they make. But they’re being cowardly and tightfisted. What are they afraid of? Why have their animal spirits gone into hibernation?

More on this in the next issue of LBO, out next week.

Audio format change?

I’m thinking of changing the bit rate for the hi-fi versions of my radio show from 64kbps to 128kbps (mono). It would double the size of the file from about 25 megs to 50 megs. Would this trouble anyone? My iPhone has no trouble with 128kbps on the AT&T network—and of course it’d be a piece of cake on WiFi. I’d still keep the 16kbps lo-fi version for people with slow dialup connections.

Thoughts?

December 6, 2012

Fresh audio product

Wow, haven’t posted in a few weeks. Sorry! Here’s some new content, just added to my radio archives. I usually post the files well in advance of updating the web page, so if you subscribe to the podcast, you’ll enjoy almost immediate gratification. Podcast instructions are on the archive page.

December 6, 2012 Jane McAlevey, author of Raising Expectations (And Raising Hell), on how to revive the U.S. labor movement [The KPFA version of this show was a fundraiser. If you like these shows and want to keep them coming, please consider contributing to KPFA. If you do, mention “Behind the News”!]

November 29, 2012 Frank Bardacke, author of Trampling Out the Vintage, on Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers

November 22, 2012 James Galbraith on the fiscal cliff • Walter Benn Michaels, author of this and this and this, on the election and the victory of left neoliberalism

November 24, 2012

Ezra Klein thinks constructively about Walmart

Neoliberal über-dweeb Ezra Klein just unleashed one of those “balanced” efforts on the controversies of the day that are so characteristic of his species: “Has Wal-Mart been good or bad?” The conclusion, it might not surprise you to learn: it’s “a complicated question to frame and a devilishly tough one to answer.”

Drawing on—I’m not kidding—Reason editor “Peter Suderman’s 17-part Twitter defense of Wal-Mart,” Klein asserts that Walmart’s low prices are a gift to low-income consumers. (They’ve dropped the hyphen/star, folks; here’s the official timeline.) The Bentonville behemoth’s wages may be low, but not “when compared with the prevailing wages in the retail sector.” Walmart’s influence in setting wages is not a topic that they consider. Nor does either our neoliberal or our libertarian actually look at the history of retail wages, because it would be rather inconvenient for their argument.

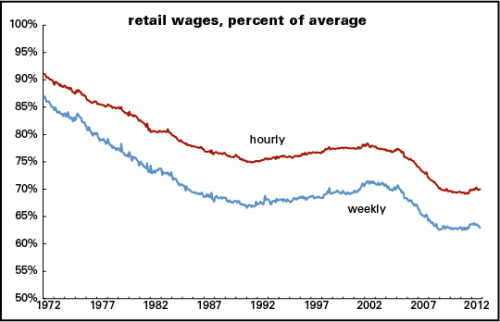

Over the last 40 years, as the real value of the hourly wage has fallen—down 9.3% since the January 1973 peak—the real retail wage has fallen three times as hard, 28.7%. The decline in weekly wages is even harsher, as workweeks have gotten shorter: down 17.2% in inflation-adjusted terms for all workers, but 38.3%, more than twice as much, for retail workers.

Or, looked at another way, the average retail hourly wage was 91% of that for all workers in 1972 (when the BLS’s retail wage stats begin) to 70% in October 2012. The decline in the weekly ratio was even steeper—from 87% of the average in 1972 to 63% in October. Here’s a graph of that history.

So clearly there‘s been a massive squeeze not only on the hourly wage, but also the number of weekly hours, in retail. (The average workweek is down about 3 hours since 1972 overall—but about 5 in retail.) And who has been the dominant force in retail over these decades? Walmart, of course. Not only is it famous for everyday low wages—it’s also famous for never providing its workers with as many hours as they’d like to work in a week.

And, yeah, it’s nice that Walmart has been able to provide a working class facing at best stagnant wages with lots of cheap stuff, but Walmart has itself had no small effect on dragging average wages down. It’s not just that they’ve been an inspiring business model for the rest for corporate sector, impressed by the chain’s growth and profitability. That’s led to endless rounds of outsourcing and speedup. But also by lowering the cost of reproduction of the working class, to use the old language, they’ve made it easier for employers to keep a lid on wages. You might think of the minimum feasible wage as the one that would assure that most of the workforce could show up and labor day after day. By lowering the cost of the bare minimum, Walmart makes it a lot easier for all employers to pay less. That brings a smile to the faces of stockholders, of course, but no so much the average worker.

Back in 1985, Alex Cockburn, reflecting on a creepy editorial about what Augusto Pinochet’s proper approach to fighting “terrorism” a decade into his dictatorial term should be, remarked that it was an instance of “our old friend The Washington Post editorialist trying to think constructively again.” Clearly Ezra Klein is extending a noble tradition, even though the Post is a mere shadow of its once-grand self.

November 15, 2012

Responding to Mike Konczal’s response

Mike Konczal responds to my criticisms of the Rolling Jubilee by rejecting arguments I don’t really make, though he runs some of them through a caricature machine, and then brings up other “more important” worries that bear no small resemblance to mine.

I can’t even make sense of some of the things he says. For example, I’m not sure what this even means, much less how it fairly represents anything I said:

Doug Henwood, for instance, believes that this is generated by activists’ uncritical populism, or the anarchist anthrology of David Graeber’s Debt, or the reification of Bowles-Simpson’s debt talk. But this is putting the carriage before the horse.

Just what is the carriage, and what is the horse?

The first part of this passage is a tendentious summary of my argument that the StrikeDebt! people have inherited from American populism an obsession with money and finance as the root of all our economic problems, while not paying much attention to the things they connect to in the real world. So, debt is a symptom of crappy wages, unemployment, expensive health care and tuition, and a cheesy welfare state. It’s fine to organize and propagandize around debt as long as you use it as a point of entry into that larger conversation—but the StrikeDebt! people have so far done that more in passing, while fixating instead on a so-called “debt system.” They say they’ll move on to that, and I hope that’s true.

Apparently Konczal actually agrees with me, because he says about 600 words later that it would be wrong to focus too much on debt itself, and declares himself happy that “the Strike Debt coalition has worked to link its concerns back to larger ones of public health care, free education, and a more robust safety net. Weaving these concerns with broader ones is precisely the work that needs to be done.” I’m not sure that the coalition is actually doing those things very prominently; almost everyone who’s commented on the scheme is talking about the buybacks, and not those larger issues.

Moving along, I assume the reference to “anarchist anthrology” is a typo, and not an invocation of Anthrax’s 2005 greatest hits compilation. Konczal is ignoring what I think is an important point: that the movement is influenced by Graeber’s analysis of debt, an analysis that really has little to say about how debt works in capitalist societies. It fixates on debt as a transhistorical category, encouraging an obsession with it to the exclusion of other economic categories.

Konczal is also skeptical about my proselytizing for bankruptcy. I hardly think it’s a “universal solvent” (solution?) and never said it was. But it could be used by a lot more people than are using it now. And, while it can be expensive, as I pointed out in the bankruptcy chapter of the Debt Resistors’ manual—a passage that thankfully survived the collective editing process—you can get free representation by contacting your local bar association. It’s a lot more promising way out of debt for more people than this debt buyback scheme. And here’s some testimony from someone who went through the process a bit over a decade ago—a passage that did not survive the manual’s editing process:

At the mere suggestion by a friend who claimed to know of a lawyer who could help me by declaring bankruptcy, I immediately felt a sense of relief. It made no sense that I was in this situation. I did not buy one thing that I didn’t need. It was extremely demoralizing. So I borrowed the amount for the small fee this lawyer asked for and was soon set free of that godawful ball and chain. And now my credit record is impeccable, and delivered from all that worry.

And another of Konczal’s “more important” worries is “whether or not this will build a community of people committed to the cause going forward.” Uncanny, since I said something very much like this myself:

It’s also difficult to imagine an organized political movement emerging from it. One of the beauties of the various Occupy encampments around the country is that it created deep bonds among participants that last to this day. These ties were the reason that Occupy Sandy emerged so quickly in New York in the wake of the hurricane. But the Rolling Jubilee operates largely through murky, near-anonymous secondary debt markets and through the media. It’s difficult to explain in itself, and it doesn’t lead easily into a discussion of larger issues of political economy. And it doesn’t create organization or social ties: even if the relieved debtors knew about their liberation, which they well might not, it would be viewed more as a deus ex machina than a political act.

Finally, I resent the hell out of the implication that I don’t care about people’s suffering, assuming that’s what it is, since it’s often hard to parse the prose in this post (though the Marx-baiting sneer is clear enough):

It’s fun to imagine people writing hostile comments on that 99% tumblr saying that all these people’s misery is not useful to the cause because it focuses on the sphere of circulation instead of the sphere of production. But this is what is behind young people’s suffering and it is an important project to address it as such.

Really, Mike, if I didn’t care, I could have chosen a more lucrative and/or less aggravating line of work. I’ve tried to be very comradely in my criticisms; you could too.

The debt obsession

As I was electronically discussing my comments on the Rolling Jubilee yesterday, I got an email from Fix The Debt, the deficit-obsessed austerian group founded by Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson. Bowles and Simpson are, of course, the deficit scolds who led the failed commission created by Barack Obama in 2010 whose mission was to lead the U.S. back to the path of fiscal rectitude.

And though the StrikeDebt! people have little in common with that gang of ghouls who want to cut Social Security and Medicare, they do share one feature: an obsession with debt. (I want to say again that I like and admire the people who conceived this project, and I offer these criticisms in a comradely, not hostile, spirit.) Instead of talking about the challenge of recovering from the after-effects of the Great Recession, of thinking how to provide people at all stages of their lives with material comfort and security, of how to humanize our mad systems of health care and education finance, of how to deal with climate change, both parties focus on debt as central to everything.

There’s an old saying in the public opinion business: we can’t tell people what to think, but we can tell them what to think about. The orthodox are constantly telling us to think about debt. But aren’t radicals supposed to challenge that discursive tyranny?

November 14, 2012

Rolling Jubilee: PS

Some follow-ups to yesterday’s Rolling Jubilee post (“Rolling where?”):

• A correction: they’re not buying credit card debt—they’re buying medical debt to start with. Several RJ people complained about this bit of misinformation, saying that it was “widely known.” It’s not on their rather sparse website though, so it’s not clear how this widely disseminated information has been disseminated.

• There were also quite a few complaints about my missing how the campaign did indeed point to a larger strategy, including a wider conversation about debt as a symptom of a larger disease rather than the disease itself. Partisans point to this sentence on the website: “We believe people should not go into debt for basic necessities like education, healthcare and housing.” Well, yes, but that’s 16 words—and it immediately segues into “a growing collective resistance to the debt system.” But debt is only one part of the system—a competitive system built around wage labor which is always, by definition, inadequate to needs. Debt can often be a supplement to paltry wages, but that doesn’t make this a debt system.

• As I said yesterday, this obsession with the centrality of debt reflects Occupy’s inheritance of American populism’s emphasis on finance at the expense of how finance fits into a larger system of production of ownership. But I suspect it’s not just populism—it’s the influence of David Graeber’s book Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Graeber’s book has many virtues—and I mean that, it’s not just boilerplate—but it offers somewhere between little and no analysis of how debt works in capitalism. (See Mike Beggs’ review for more.) Debt (or credit, to use the more upbeat word) allows people and businesses to buy things beyond the limits of current income, which means that while many people view it as nothing but a burden, many others view it as a way to buy cars, houses, and capital equipment that they couldn’t afford out of the cash lurking in their pockets. And since one person’s debt is another’s asset, it becomes a repository of savings, and not just the savings of the proverbial 1%. Any serious debt strike—one that was more than symbolic, meaning measured in the billions and not the millions, much less the thousands—would threaten those savings, and be greeted by a large chunk of the population as not liberating, but dangerous.

• Speaking of popular opinion, people who have been sweating to pay their debts might not view the deliverance of the heavily indebted as a cause for celebration. They might view it as unfair. Debt aggregates are typically driven by a minority of very heavily indebted people or businesses, and simple averages can be very misleading.

• It’s really difficult to see how the buyback scheme leads to a larger conversation about debt. It’s also difficult to imagine an organized political movement emerging from it. One of the beauties of the various Occupy encampments around the country is that it created deep bonds among participants that last to this day. These ties were the reason that Occupy Sandy emerged so quickly in New York in the wake of the hurricane. But the Rolling Jubilee operates largely through murky, near-anonymous secondary debt markets and through the media. It’s difficult to explain in itself, and it doesn’t lead easily into a discussion of larger issues of political economy. And it doesn’t create organization or social ties: even if the relieved debtors knew about their liberation, which they well might not, it would be viewed more as a deus ex machina than a political act.

• Call me old-fashioned, and I’m sure many have already done so, but I think that a discussion of those larger issues—stagnant wages, high unemployment, a crazy system of health care finance, madly expensive higher education—would lead inevitably to making demands on the state. (So too would debt relief: it would be a lot more powerful and effective if the Federal Reserve and the Treasury were buying bad debt and liberating debtors with their vast resources rather than a volunteer effort raising funds through Paypal.) And given the prominent role that anarchists and anarchism play in the Occupy movement, there’s not much inclination to make demands on the state. But what other institution in this society could raise the minimum wage, make it easier to organize unions, fund a Green New Deal to address climate change and create decent jobs, create a single-payer health care system, and provide universal free higher ed? The lack of those things in this very rich society contribute a lot to debt and deprivation. But that lack is not the product of a “debt system.”

I am very willing, eager even, to be proven wrong. So should this thing take off in fruitful ways, I will happily eat my words—and my hat too, with a side of crow.

November 13, 2012

Rolling where?

Rolling Jubilee (RJ) has certainly gotten a lot of attention in the few days since it was launched. An initiative of Strike Debt!, an offshoot of Occupy Wall Street, the Jubilee describes itself as

a…project that buys debt for pennies on the dollar, but instead of collecting it, abolishes it. Together we can liberate debtors at random through a campaign of mutual support, good will, and collective refusal. Debt resistance is just the beginning. Join us as we imagine and create a new world based on the common good, not Wall Street profits.

Anything that attracts attention to the burden of debt and the potential of liberation from it is admirable. But it will not surprise regular readers to learn that I’ve got some serious reservations about the project.

A few words first on the mechanics. Banks and other creditors typically try really hard to collect delinquent debts, but when they give up all hope, they write them off and typically sell the claims for pennies on the dollar to collection agencies and other financial vultures. The new holders are often relentless and ugly in their pursuit of debtors in default. If they bought the bad debt for two cents on the dollar, they’re happy to get five—they’ve more than doubled the money, though they do have to pay the call centers that do the ugly work of harassment. The tools of the trade are relentless threatening phone calls. Many of these techniques are technically illegal, but the law rarely stops a collection agency. According to Strike Debt!, about 15% of Americans are being pursued by collection agents, and there’s no reason to doubt their numbers.

Strike Debt!’s strategy is to raise money from generous sympathizers and buy the debt from the collection agents and then just wipe it away. Debtors might not even know what’s happened—they tell me they’re reluctant to track down the debtors they’ve delivered from harassment, and in many cases might not even be able to—but the phone calls will at least stop.

Sounds great, right? And the scheme has gotten some great buzz. Blogger Alex Moore writes that it’s “a great new answer to all the doubters who ripped on them over the past year for not having a specific enough plan.” To Guardian blogger Charles Eisenstein, it’s a “genius move” with “significant transformative potential.” Celebrants, though, are rather vague on the mechanisms by which the transformation will occur.

So far, both Rolling Jubilee and the commentators have been rather light with numbers. As I’m writing this, RJ has raised $137,688. Since they figure they can buy bad debt for about five cents on the dollar, that means they could “abolish” (the evocation of the anti-slavery movement is no accident) $2,758,584 in debt. Though they don’t say, it’s almost certain that the debt they aim to buy is the credit card kind. Student debt, even if delinquent, isn’t sold into the secondary market. Debt backed by things—as auto loans are by vehicles and mortgages by houses—aren’t generally sold that way either, because lenders can seize the underlying assets. Though there are other kinds of unsecured personal loans (those backed by pledges only, and not things), the bulk of them are credit cards, so we’ll do the math on them.

According to the FDIC, there was $664.3 billion credit card debt outstanding in the second quarter of 2012. Of that, $16.5 billion was 30 days or more past due. Banks had charged off $8.5 billion. They’re required by regulators to do that once an account is 180 days past due, but that doesn’t mean the debt is extinguished. Though the bank removes the asset from its balance sheet and takes a (tax-deductible) loss, the debt still exists. The bank can try to collect it on its own, or sell the bad debt to the vultures described above.

Let’s think about that $8.5 billion. The people who owe that money are probably getting threatening communications from the banks or whoever now holds the claims. If RJ could raise $1 million—they’re more than 1/8th of the way there now—they could buy $20 million in debt, or 0.2% of what’s been charged off. To buy all the charged-off debt at five cents on the dollar, they’d need to raise $423 million. But of course if any more than notional amounts of money were put to this task, the price of the debt would rise dramatically. To buy a tenth of it at ten cents on the dollar they’d need $85 million. In other words, given those sums, the monetary angle for RJ is purely symbolic.

What about larger political points? Strike Debt! says its aim is:

to build popular resistance to all forms of debt imposed on us by the banks. Debt keeps us isolated, ashamed, and afraid. We are building a movement to challenge this system while creating alternatives and supporting each other. We want an economy where our debts are to our friends, families, and communities — and not to the 1%.

Totally marvelous. No argument from me about the goal. But why the intense focus on debt and its relief? Debt could be an excellent point of entry into a discussion about many other things. Why so much personal debt? Because wages are stagnant or down, unemployment is high, yet the cost of living continues to rise. Why so much mortgage debt? Because until sometime in 2007, housing inflation (meaning tax-subsidized homeownership) was practically the American national religion. Why so much student debt? Because higher education is too expensive—in fact, it should be free. Etc. But Occupy has inherited a lot of American populism’s obsession with finance as the root of all evil, without connecting it to the rest of the system.

And their call for debt repudiation also seems not to have been fully thought through. The world economy nearly collapsed a few years ago because maybe 10% of debtors were unable to service their debts. If we were to return to something like that, we’d return to the verge of collapse or beyond. And such a collapse wouldn’t hurt just the 1%. Workers’ pensions would be jeopardized. Banks would fail, and millions could lose their savings. Unemployment would rise towards 1932 levels of 25%. If you’re jonesing for systemic collapse in the hope of building something better out of the rubble, then be honest about it. But don’t expect to get much support for the agenda.

A more fruitful approach to lightening the burden of the heavily indebted would be to proselytize on behalf of filing for bankruptcy. Another project of Strike Debt! is their Debt Resistors Operations Manual. Here’s their description of the manual:

You’ll find detailed strategies and resources for dealing with credit card, medical, student, housing and municipal debt. Also included are tactics for navigating the pitfalls of personal bankruptcy, and information to help protect yourself from predatory lenders. Recognizing that individually we can only do so much to resist the system of debt, the manual also introduces ideas for those who have made the decision to take collective action.

There’s a lot of good stuff in there. But the chapter on bankruptcy is larded with unnecessary warnings and complications. I know, because I wrote the original draft and watched it get deformed by group editing. The opening sentence is a fine example: “Bankruptcy, for some people, sometimes, can be a way to fight back against the creditors and escape a life of indebtedness.” No, bankruptcy is much better than that. My original opening read: “Unlike the other chapters in this manual, which are organized around ways the rich screw debtors (and how debtors can get back at them), this one is almost entirely about how debtors can screw the rich—filing for bankruptcy. To get right to the point: if you have a serious problem with credit card debt, there is absolutely no reason you shouldn’t think seriously about doing that.” Much better, I think.

And the chapter concludes by saying that it’s an unsatisfactorily individualist solution to a collective problem—which is true in some sense, but not of much help to millions suffering from credit card debt today. Many people are unaware of what a deliverance a bankruptcy filing can be, and many others are inhibited by shame. They shouldn’t be. And filing for bankruptcy has a lot more to offer than some lightly funded scheme to buy bad debt on the secondary market. Why the Strike Debt! collective chose to tone down my exhortations mystifies me.

I feel somewhat bad writing this critique. There are a lot of fine people trying to do good things with this initiative. But as long as it focuses on debt without using it as a portal to a larger discussion, it’s not going to do much more than generate some publicity.

November 9, 2012

Fresh audio product

Just added to my radio archives:

November 8, 2012 Sarah Jaffe on Occupy Sandy • Anne Elizabeth Moore, author of Hip Hop Apsara, on Cambodia

No show last week, alas: blown off course by Hurricane Sandy.

October 26, 2012

Much fresh audio product

Some of this just posted to my radio archives, and some of it’s been around for a while without being noted on the web page. Subscribe to the podcast (here’s the iTunes page—details on other portals on my archive page), and you’ll get the audio files right after they’re posted, instead of waiting for me to update the web index.

Note: several of these shows were fundraisers for KPFA. I’ve cut out the pleas, but if you want to keep these coming, please support KPFA.

October 25, 2012 Jodi Dean, professor of political science at Hobart & William Smith and author of The Communist Horizon, on how we need to reclaim that cuss-word and stop fetishizing “democracy”

October 18, 2012 Josh Eidelson on the Walmart strikes (his Salon stories are here) • Ethan Pollack of the Economic Policy Institute on green jobs

October 11, 2012 David Cay Johnston, author of The Fine Print, on how Corporate America rips us off

October 4, 2012 Matt Kennard, author of Irregular Army, on the neo-Nazis, gangbangers, and sad/broken people who populate our military, and the damage they’ve done and will do.

September 27, 2012 Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin, authors of The Making of Global Capitalism, on U.S. imperial power, etc.

September 20, 2012 Bruce Bartlett on his scary former GOP comrades • Jared Bernstein on income, poverty, and the 47%

Doug Henwood's Blog

- Doug Henwood's profile

- 30 followers