Zetta Elliott's Blog, page 77

April 9, 2012

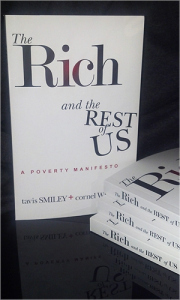

The Rich & The Rest of Us

Join Us for a Post-National Black

Join Us for a Post-National BlackWriters Conference (NBWC) Event

featuring

NBWC Past Participants

TAVIS SMILEY

and CORNEL WEST

Meet Tavis Smiley and Cornel West

at a Fundraiser for the

Center for Black Literature

Friday, April 20, 2012

6:30pm

The Kaye Playhouse at Hunter College

695 Park Avenue (at E. 68th Street)

(between Park & Lexington Avenues)

New York, NY 10065

POVERTY THREATENS OUR DEMOCRACY

Smiley and West take on the "P" word—poverty. During this compelling lecture and book-signing they challenge all Americans to re-examine their assumptions about poverty in America-what it really is and how to eradicate it.

Join Tavis Smiley and Cornel West

on Friday, April 20, 2012

at a lecture & book signing for

a Fundraiser for the Center for Black Literature

Get Your Tickets In Advance & Buy Now!

$35 (includes book)

$25 (without book)

Go to www.CLSJ.org and click "Donate"

[Online ticketing administered by the Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College (CLSJ)].

We thank you for your continued support of

the Center for Black Literature at Medgar Evers College!

For more information, call 718.270.4811

or visit www.centerforblackliterature.org

April 6, 2012

Blackout in the Great White North

I've decided to post my paper from last month's "Race, Ethnicity, and Publishing" conference here on my blog. Unfortunately, I don't have time this month to expand this essay, though I know it would benefit from input from Canadian publishers. I'm still hopeful that this topic will get the attention it deserves at a conference of its own. For now, this is all I have to offer. (This essay only considers English language novels that were authored by African Canadians and published by Canadian presses.)

"Blackout in the Great White North:

Responding to Racism & Erasure in the Canadian Children's Publishing Industry"

Whenever I speak publicly about the children's publishing industry, I feel the need to start with a confession. I am an academic but I am also an author; my third book for young readers was published in February, and I only began researching racism in publishing after surviving a decade of rejection as a young writer. In fact, I turned to the academy when I finally accepted the fact that I was not going to sell my first novel for a six-figure advance. My academic training allows me to think critically—if not dispassionately—about race and representation within the field of children's literature. I know that for some, my critique of the publishing industry will automatically be dismissed as "sour grapes," and it is true that I likely never would have investigated the players in this game had I succeeded in placing more of my manuscripts. As it is, despite winning a number of awards, about 80% of my work remains unpublished, and I admit that I began studying the industry in order to understand how so many editors could praise my writing and yet refuse to publish my work.

When I discovered that only 3% of children's book authors published annually in the US were black, I abandoned my naïve assumption that publishing was a matter of merit; thanks to statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children's Book Center, I now had proof that the problem was institutional and systemic. Whatever the world might think about my so-called "bad attitude," there was something much bigger and more sinister at play; black writers in North America face much steeper odds than the average white writer. As John K. Young explains in Black Writers, White Publishers: Marketplace Politics in Twentieth-Century African American Literature (2006), "…what sets the white publisher-black author relationship apart is the underlying social structure that transforms the usual unequal relationship into an extension of a much deeper cultural dynamic. The predominantly white publishing industry reflects and often reinforces the racial divide that has always defined American society."

Satisfied that I had discovered the ugly truth about racism in US children's publishing, I turned my attention to Canada, land of my birth. This paper was supposed to be about the responses to racism & erasure in the Canadian children's publishing industry, but since I began speaking and writing on the subject two years ago, I haven't detected much of a response at all. I reached out to academics and librarians in Canada and proposed a symposium on multicultural children's literature; the idea was taken up by the Children's Studies Program at York University, but I believe they have since postponed the event indefinitely. And so the "blackout" that I reference in the title of my paper refers both to the relative exclusion of black writers from the Canadian literary scene, but also the disinclination of certain members of the publishing community to publicly acknowledge that a problem exists.

This conference paper actually started out as an article I wrote in the summer of 2011 at the request of Quill & Quire, "the" magazine of the Canadian book trade. When I shared with them my research on African Canadian children's literature, an editor immediately expressed interest and asked me to write something. I turned in an essay within a week, but months later the editor stopped returning my emails, apparently having a change of heart. In January, a colleague asked for Black History Month submissions for the blog of the Canadian Federation of the Humanities and Social Sciences; I reworked my piece for Quill & Quire but to my surprise, this second editor made a number of changes to my essay, including the title, which went from "Achieving Excellence & Avoiding Annihilation" to "Gatekeepers and Border Crossings: Celebrating Canada's Talented Black Writers."

It was not my intention then, nor is it my intention now, to "celebrate" the talent of African Canadian writers; indeed, I worry that well-intentioned boosterism too often takes the place of rigorous critiques of novels by black Canadians, and I have no desire to contribute to that trend. Instead I would like to explore the challenges faced by African Canadian novelists, drawing upon my own perspective as an expatriate writer as well as the experiences of eight black authors whom I interviewed via email. This paper will address the "difficult miracle" of becoming a black author in the Great White North, and will conclude with some suggestions for broadening the path to publication.

Naming the Problem

Last summer, after returning from a cross-border trip to Toronto, a friend of mine asked: "What's wrong with Canada?" It's a question she and I have considered over the years as we've worked to establish ourselves as black women writers and scholars in New York City. Rosamond S. King is a poet/performance artist/activist/academic. I met her in graduate school at NYU, where she wrote her dissertation on Caribbean immigrant literature, including texts by Dionne Brand and Austin Clarke.

It was both surprising and embarrassing for me to find that many graduate students in the United States knew more about African Canadian literature than I did. I read no  black-authored books as a child growing up in Toronto, and in high school was exposed to "classics" written primarily by white American authors (e.g. Catcher in the Rye, A Streetcar Named Desire, The Great Gatsby, To Kill a Mockingbird.). The few black-authored novels I had access to also came from the US, and so in 1994 when I decided to pursue my dream of becoming a writer, I left Canada with barely a backward glance, convinced that my best chance of success was on the other side of the border.

black-authored books as a child growing up in Toronto, and in high school was exposed to "classics" written primarily by white American authors (e.g. Catcher in the Rye, A Streetcar Named Desire, The Great Gatsby, To Kill a Mockingbird.). The few black-authored novels I had access to also came from the US, and so in 1994 when I decided to pursue my dream of becoming a writer, I left Canada with barely a backward glance, convinced that my best chance of success was on the other side of the border.

In some ways, it's reassuring to know that my African American friends also sense something "wrong" when they venture into the Great White North. Most bookstores carry few if any black-authored books, and African Canadians seem satisfied with—or resigned to—having limited literary offerings for themselves and their children. Blacks in the US don't always realize their relatively privileged position in relation to other members of the African diaspora; compared to Canada, African Americans represent a much larger percentage of a much larger nation, and while many challenges remain, they have a long tradition of highlighting African American talent and resisting racism and social exclusion in publishing and other spheres of life.

When the 2012 Coretta Scott King Book Awards were announced recently, my American community of book bloggers, librarians, and educators bemoaned the fact that the same black children's book authors and illustrators seem to win the CSKs year after year. My colleagues here in the US have to be reminded that there are countries where not enough books are published annually to even sustain such an award. A prize for the best children's book written or illustrated by a black artist is a luxury that the Canadian publishing industry cannot afford and to which, I suspect, it does not aspire.

When the 2012 Coretta Scott King Book Awards were announced recently, my American community of book bloggers, librarians, and educators bemoaned the fact that the same black children's book authors and illustrators seem to win the CSKs year after year. My colleagues here in the US have to be reminded that there are countries where not enough books are published annually to even sustain such an award. A prize for the best children's book written or illustrated by a black artist is a luxury that the Canadian publishing industry cannot afford and to which, I suspect, it does not aspire.

Book awards are meant to celebrate excellence, but can excellence emerge from a small and/or stagnant pool? I call this phenomenon the "big fish, small pond" syndrome, which ensures that a handful of authors are celebrated while emerging talent often is left undiscovered and/or undeveloped. Indian author/activist Arundhati Roy calls this the "new racism," which she explains using this brilliant analogy:

Every year, the National Turkey Federation presents the US president with a turkey for Thanksgiving. Every year, in a show of ceremonial magnanimity, the president spares that particular bird (and eats another one). After receiving the presidential pardon, the Chosen One is sent to Frying Pan Park in Virginia to live out its natural life. The rest of the 50 million turkeys raised for Thanksgiving are slaughtered and eaten on Thanksgiving Day. ConAgra Foods, the company that has won the Presidential Turkey contract, says it trains the lucky birds to be sociable, to interact with dignitaries, school children and the press.

That's how new racism in the corporate era works. A few carefully bred turkeys – the local elites of various countries, a community of wealthy immigrants, investment bankers, the occasional Colin Powell, or Condoleezza Rice, some singers, some writers (like myself) – are given absolution and a pass to Frying Pan Park.

The remaining millions lose their jobs, are evicted from their homes, have their water and electricity connections cut, and die of AIDS. Basically, they're for the pot. But the fortunate fowls in Frying Pan Park are doing fine.

If the Canadian publishing industry only opens the gate for two or three black novelists each year, what happens to all the other talented and aspiring writers? According to my research, thirty-one novels written by twenty African Canadian authors have been published in Canada since the start of the twenty-first century – and only four of the twenty were by first-time authors. A rather astonishing percentage of  those novels have won or been nominated for major literary awards, including Esi Edugyan's Half Blood Blues, which won the 2011 Giller Prize. Yet can you name three black Canadian women novelists under the age of forty? I can't. I couldn't do it when I emigrated in 1994, and I still can't do it now that I'm nearing forty myself. I can name black women novelists from the UK (e.g. Helen Oyeyemi, Diana Evans, Zadie Smith) and the US (e.g. Jesmyn Ward, N.K. Jemisin, Heidi Durrow). I adore the novels of Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie, an amazingly talented writer from Nigeria. But when I think about young black Canadian women novelists, I draw an unsettling blank.

those novels have won or been nominated for major literary awards, including Esi Edugyan's Half Blood Blues, which won the 2011 Giller Prize. Yet can you name three black Canadian women novelists under the age of forty? I can't. I couldn't do it when I emigrated in 1994, and I still can't do it now that I'm nearing forty myself. I can name black women novelists from the UK (e.g. Helen Oyeyemi, Diana Evans, Zadie Smith) and the US (e.g. Jesmyn Ward, N.K. Jemisin, Heidi Durrow). I adore the novels of Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie, an amazingly talented writer from Nigeria. But when I think about young black Canadian women novelists, I draw an unsettling blank.

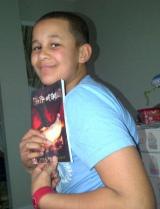

Over the past couple of years I've found myself writing extensively about my childhood in Canada and my subsequent efforts to "decolonize" my imagination. I started my blog to advocate for greater equity and inclusion in the United States publishing industry, but soon realized that the situation was actually  much worse for blacks in Canada. I dedicated my latest novel, Ship of Souls, to my cousin's son, Kodie. He's not yet twelve but his childhood in twenty-first century Canada is looking a lot like my own childhood of the 1970s and '80s. His white mother and black father are no longer together, and this brown-skinned child is growing up outside of Toronto in an all-white environment. I send him books from the US that offer Kodie a mirror in which he can see himself, but I resent the fact that his mother can't walk into a local bookstore or library and find Canadian books that do the same.

much worse for blacks in Canada. I dedicated my latest novel, Ship of Souls, to my cousin's son, Kodie. He's not yet twelve but his childhood in twenty-first century Canada is looking a lot like my own childhood of the 1970s and '80s. His white mother and black father are no longer together, and this brown-skinned child is growing up outside of Toronto in an all-white environment. I send him books from the US that offer Kodie a mirror in which he can see himself, but I resent the fact that his mother can't walk into a local bookstore or library and find Canadian books that do the same.

Last year I began to compile a bibliography on my blog and discovered that, of the 500 English-language books published for children in Canada each year, on average only three are written by black authors. Since 2000, of the nearly thirty novels featuring a black protagonist, only two depict black children living in contemporary Canada. Outraged (though not especially surprised), I wrote an essay, "Navigating the Great White North: Representations of Blackness in Canadian Young Adult Literature," in which I examined this "symbolic annihilation" of black youth:

I detect a disturbing focus on people of colour who are represented as distinctly not Canadian, not living within the country's borders, and not active in the current historical moment; blacks specifically are imagined as foreigners and/or figures from the distant past rather than established/integrated members of the national "mosaic."

…instead of reflecting this racially diverse nation, books for young readers published in Canada during the first decade of the twenty-first century paint a picture of a country devoid of black citizens.

…black youth appear as fugitive and/or former slaves or as impoverished Africans grappling with violence and disease. Why is it so difficult for authors of any race to situate black teens in contemporary Canada? Why do so many authors prefer to see blacks as "eternal slaves" seeking sanctuary in "the promised land?" And what effect does the erasure of black teens from the contemporary Canadian landscape have on young readers?

I worry that, like me, Kodie will grow up not dreaming in color, not imagining himself as worthy of assuming the starring role in literature (as protagonist and/or author). Right now he has aspirations of becoming a writer and I'll do what I can to help him realize that goal. But I'm not a very good role model since I never managed to get my own books published in Canada, and ultimately chose to leave rather than blaze a trail that successive generations might follow.

The Difficult Miracle of Black Canadian Writers

In her 1986 essay, "The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America: Something Like a Sonnet for Phillis Wheatley," African American poet/activist June Jordan marvels at the daring and determination of black writers to express their truths in a land that is hostile to their existence as anything other than slaves:

…the difficult miracle of Black poetry in America, is that we have been rejected and we are frequently dismissed as "political" or "topical" or "sloganeering" and "crude" and 'insignificant" because…we have persisted for freedom…We will write, published or not, however we may…of the terror and the hungering and the quandaries of our African lives on this North American soil. And as long as we study white literature, as long as we assimilate the English language and its implicit English values, as long as we allude and defer to gods we "neither sought nor knew," as long as we…remain the children of slavery, as long as we do not come of age and attempt, then to speak the truth of our difficult maturity in an alien place, then we will be beloved, and sheltered, and published.

But not otherwise. And yet we persist.

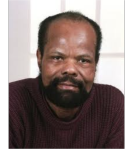

Considering the challenges they face, it is somewhat miraculous that black writers manage to get published in Canada. The eight African Canadian authors I interviewed for this paper were first asked to describe their exposure to black characters within the books they read children. Tessa McWatt, David Chariandy, Cheryl Foggo, and Suzette Mayr all expressed a love of books that started at an early age, but also  reported that they found few if any representations of black children. Cheryl Foggo recalled seeing the loathsome image of Little Black Sambo in the 1960s, and stated that she "decoloured" herself in order to identify with beloved characters like Anne of Green Gables and Trixie Belden. Suzette Mayr, who also grew up in Alberta but a decade later, was drawn to British novels by E. Nesbit and Enid Blyton but also read and was deeply moved by American novels with black protagonists such as Sounder and The House of Dies Drear. David Chariandy (who grew up in the 1970s a few

reported that they found few if any representations of black children. Cheryl Foggo recalled seeing the loathsome image of Little Black Sambo in the 1960s, and stated that she "decoloured" herself in order to identify with beloved characters like Anne of Green Gables and Trixie Belden. Suzette Mayr, who also grew up in Alberta but a decade later, was drawn to British novels by E. Nesbit and Enid Blyton but also read and was deeply moved by American novels with black protagonists such as Sounder and The House of Dies Drear. David Chariandy (who grew up in the 1970s a few  doors down from me in Scarborough, ON) explained that it took "a degree of imagination" for him to see himself in the books he read as a child since so few contained images of people who looked like him. Chariandy further shared that he had no role models once he decided, as a child, that he wanted to become a writer; he never met an author until reaching university, and today believes he pursued a career as a literature professor because it seemed to be "the only way for someone like me to be around books."

doors down from me in Scarborough, ON) explained that it took "a degree of imagination" for him to see himself in the books he read as a child since so few contained images of people who looked like him. Chariandy further shared that he had no role models once he decided, as a child, that he wanted to become a writer; he never met an author until reaching university, and today believes he pursued a career as a literature professor because it seemed to be "the only way for someone like me to be around books."

Born and raised in Kenya, David Odhiambo began writing as a Canadian university student, and at that time knew only of African Canadian author Dany Laferriere who was also based in Montreal; after "a couple of polite rejections from Independent Houses," Odhiambo's first novel, completed at age 23, "ended up abandoned in a file cabinet"—it took ten more years for his first novel to be published. While submitting query letters to publishers for her memoir, Pourin' Down Rain, Cheryl Foggo was told by one publisher that "there were not enough Black people in Canada to justify publishing [her] book." Foggo eventually found a supportive small press, yet notes that despite having "many publishing credits and awards" on her resume, she was "surprised" by the trouble [she] had placing the manuscript for her recent children's picture book, Dear Baobab.

Born and raised in Kenya, David Odhiambo began writing as a Canadian university student, and at that time knew only of African Canadian author Dany Laferriere who was also based in Montreal; after "a couple of polite rejections from Independent Houses," Odhiambo's first novel, completed at age 23, "ended up abandoned in a file cabinet"—it took ten more years for his first novel to be published. While submitting query letters to publishers for her memoir, Pourin' Down Rain, Cheryl Foggo was told by one publisher that "there were not enough Black people in Canada to justify publishing [her] book." Foggo eventually found a supportive small press, yet notes that despite having "many publishing credits and awards" on her resume, she was "surprised" by the trouble [she] had placing the manuscript for her recent children's picture book, Dear Baobab. My youngest interviewee, Zalika Reid-Benta, was recently selected by George Elliott Clarke as a "writer to watch" on the CBC Books blog. She has nonetheless decided to pursue an MFA in Creative Writing at Columbia University in NYC. Despite having competitive offers from Canadian schools, Reid-Benta said she chose to study in the US because "Canada has a very limited and Eurocentric definition of Canadian literature" and if she stayed, then her writing would "suffocate." Shortlisted for the Random House of Canada Student Writing Award, Reid-Benta learned that her use of Jamaican "patwa" held her back: "one of the things a few of the Random House judges told me was that they loved my story but couldn't get past the dialect and it made it harder to navigate. I have tried to write my stories without that dialect and it just doesn't feel right to me so I've decided to keep it…it's something I won't compromise."

My youngest interviewee, Zalika Reid-Benta, was recently selected by George Elliott Clarke as a "writer to watch" on the CBC Books blog. She has nonetheless decided to pursue an MFA in Creative Writing at Columbia University in NYC. Despite having competitive offers from Canadian schools, Reid-Benta said she chose to study in the US because "Canada has a very limited and Eurocentric definition of Canadian literature" and if she stayed, then her writing would "suffocate." Shortlisted for the Random House of Canada Student Writing Award, Reid-Benta learned that her use of Jamaican "patwa" held her back: "one of the things a few of the Random House judges told me was that they loved my story but couldn't get past the dialect and it made it harder to navigate. I have tried to write my stories without that dialect and it just doesn't feel right to me so I've decided to keep it…it's something I won't compromise."

I see something of myself in Zalika Reid-Benta. Like me, all the books she read as a child had white protagonists, and by the time she reached college, her role models were all writers of color based in the US. Grateful to have several mentors including George Elliott Clarke, Benta-Reid wishes there was some kind of forum for African Canadian writers. Cheryl Foggo agrees, urging that, "opportunities for professional development and networking be heavily promoted to young writers from diverse communities."

The visibility of African Canadian authors is closely tied to the exposure their books receive in review journals and newspapers (and, to a lesser extent, I think, in the blogosphere). Despite winning numerous awards throughout his thirty-year career, George Elliott Clarke admits that he still doesn't "feel 'respected,' per se." Although his ten books of poetry have gone into multiple editions, Clarke attributes this to his work being taught at the college level: "I still find most white critics 'grudging' toward my work, while black critics are more favourable, but still too few." H. Nigel Thomas concurs: "unless a book comes out with a major publisher it receives few reviews." For Clarke, the solution is two-fold: "What is still needed is a cadre of critics who understand and appreciate the specific poetics of consciously 'black' articulation as well as the development of African-Canadian literary journals."

The visibility of African Canadian authors is closely tied to the exposure their books receive in review journals and newspapers (and, to a lesser extent, I think, in the blogosphere). Despite winning numerous awards throughout his thirty-year career, George Elliott Clarke admits that he still doesn't "feel 'respected,' per se." Although his ten books of poetry have gone into multiple editions, Clarke attributes this to his work being taught at the college level: "I still find most white critics 'grudging' toward my work, while black critics are more favourable, but still too few." H. Nigel Thomas concurs: "unless a book comes out with a major publisher it receives few reviews." For Clarke, the solution is two-fold: "What is still needed is a cadre of critics who understand and appreciate the specific poetics of consciously 'black' articulation as well as the development of African-Canadian literary journals."

As mentioned previously, a remarkably high percentage of books by African Canadians are nominated for and/or awarded prestigious literary prizes—according to my research, 18 of the 31 novels written by African Canadians since 2000 have been nominated for a literary prize (nearly 60%) with 7 winners (23% of the total). Does this mean that editors at Canadian presses are especially adept at identifying the very best black writers? If there is irrefutable evidence that black writers in Canada are writing at the highest level, then why haven't their numbers increased? Cheryl Foggo  notes that "it has been proven to the Canadian publishing industry that African-Canadian subject matter will sell, and…I hope this means writers of African descent in Canada can expect to be received with interest and due consideration by publishing houses." H. Nigel Thomas is less optimistic: "Now there are few publishing options for Caribbean and African Canadian writers, fewer today than in [the] eighties and nineties or for that matter the fifties and sixties. If a publisher takes a chance on you and brings out your first book, it had better win a significant prize or you are dead on arrival." Thomas identifies another hurdle, which is that "major publishers read manuscripts from literary agents only, and tell [those agents] which manuscripts not to send."

notes that "it has been proven to the Canadian publishing industry that African-Canadian subject matter will sell, and…I hope this means writers of African descent in Canada can expect to be received with interest and due consideration by publishing houses." H. Nigel Thomas is less optimistic: "Now there are few publishing options for Caribbean and African Canadian writers, fewer today than in [the] eighties and nineties or for that matter the fifties and sixties. If a publisher takes a chance on you and brings out your first book, it had better win a significant prize or you are dead on arrival." Thomas identifies another hurdle, which is that "major publishers read manuscripts from literary agents only, and tell [those agents] which manuscripts not to send."

Addressing the issue of race in the US publishing industry, John Young contends that "Minority texts are edited, produced, and advertised as representing the 'particular' black experience to a 'universal,' implicitly white (although itself ethnically constructed) audience" (4). Young further suggests that "a concentration of money and cultural authority in mainstream publishers works to produce images of blackness that perpetuate an implicit black-white divide between authors and readers, with publishers acting as a gateway in this interaction" (6). Gatekeepers within the publishing industry, therefore, seek to satisfy the reading public's (perceived) desire for difference: "the basic dynamic through which most twentieth-century African American literature has been produced derives from an expectation that the individual text will represent the black experience (necessarily understood as exotic) for the white, and therefore implicitly universal, audience" (12).

When David Odhiambo completed his first novel he thought to himself, "just wait till Canadians see the kind of racism my novel exposes." But that novel never made it past the industry gatekeepers. Suzette Mayr is pleased by the success of many of her peers, but notes that "So much African-Canadian fiction is very dour, very earnest, [and]  usually pretty depressing." A wider range of stories isn't really possible, however, when only two novels are published nationwide each year. David Chariandy submitted his first novel to the larger presses in Canada but "received no offer to publish, and was even 'fired' by a literary agent." Chariandy admits that his manuscript "wasn't quite 'ready,'" but suspects another factor was at play:

usually pretty depressing." A wider range of stories isn't really possible, however, when only two novels are published nationwide each year. David Chariandy submitted his first novel to the larger presses in Canada but "received no offer to publish, and was even 'fired' by a literary agent." Chariandy admits that his manuscript "wasn't quite 'ready,'" but suspects another factor was at play:

…what I was addressing in terms of black experience in Canada was rather "new" and difficult to process in terms of conventional publishing categories. I wanted to write not an immigrant narrative, nor a story set in some darker-skinned "elsewhere," but a story set in Canada from the perspective of the children of racial minority immigrants. Ultimately, I published my novel content with what I'd done, but not particularly optimistic about how it would be received.

Chariandy's pessimism was fortunately unfounded: Soucouyant was a finalist for the Governor General's Literary Award for Fiction and was short-listed for six others prizes including the Commonwealth Writers' Prize for Best First Book.

Chariandy's pessimism was fortunately unfounded: Soucouyant was a finalist for the Governor General's Literary Award for Fiction and was short-listed for six others prizes including the Commonwealth Writers' Prize for Best First Book.

Conclusion

Will the second decade of the 21st century look any different than the first? George Elliott Clarke argues that African Canadians "need a national publishing infrastructure (and critical/reception apparatus) to help along emerging writers," and H. Nigel Thomas agrees: "The solution would be for Blacks to establish publishing houses and the promotion infrastructure that makes people aware of products," though he feels that "geography, demographics, [and] economics  conjoin against" such an endeavor. Tessa McWatt believes that "Canada is a much better place for writers of African descent than many other countries (particularly the UK) as it has more small presses that support 'marginalised' writers." McWatt feels that ultimately, "the problem is systemic and deeper than publishing can solve," and that "to enhance the publishing of African-Canadian authors we need to enhance the readership. This is done in schools and communities and in families – encouraging reading of all literature at all levels." Yet how can this happen when gatekeeping in the Canadian publishing industry limits the flow of diverse voices to a trickle?

conjoin against" such an endeavor. Tessa McWatt believes that "Canada is a much better place for writers of African descent than many other countries (particularly the UK) as it has more small presses that support 'marginalised' writers." McWatt feels that ultimately, "the problem is systemic and deeper than publishing can solve," and that "to enhance the publishing of African-Canadian authors we need to enhance the readership. This is done in schools and communities and in families – encouraging reading of all literature at all levels." Yet how can this happen when gatekeeping in the Canadian publishing industry limits the flow of diverse voices to a trickle?

For me, effecting change in Canadian publishing is difficult when I've committed myself to life in another country; as an expatriate it is challenging to organize a much-needed symposium on multicultural children's literature – something comparable to the inaugural 'A Is For Anansi' conference held in 2010 at NYU. In the US I have advocated for the adoption of a Publishing Equalities Charter like the one sponsored  by the Diversity In Publishing Network (DIPNET) in the UK, but my pleas have had little if any effect. I have, nonetheless, managed to launch my writing career, and I have found a community of like-minded activists who helped me to establish a childhood literacy initiative with an emphasis on purchasing multicultural books. As a black writer, I have no regrets about leaving Canada. By comparison, the US is a vast sea that is, perhaps, more perilous but ultimately more productive for me than Canada's "small pond."

by the Diversity In Publishing Network (DIPNET) in the UK, but my pleas have had little if any effect. I have, nonetheless, managed to launch my writing career, and I have found a community of like-minded activists who helped me to establish a childhood literacy initiative with an emphasis on purchasing multicultural books. As a black writer, I have no regrets about leaving Canada. By comparison, the US is a vast sea that is, perhaps, more perilous but ultimately more productive for me than Canada's "small pond."

young, black–and HUMAN

Up before dawn on the first day of spring break, hoping this headache doesn't bloom into a migraine. Lots to watch online (episode one of Great Expectations at PBS.org) and Amy Bodden Bowllan has posted Part 1 and Part 2 of our conversation about race and representation in the wake of the murder of Trayvon Martin. I use this poem by Sharon Flake in my poetry workshops, but think I'll include the cover image from now on…

Up before dawn on the first day of spring break, hoping this headache doesn't bloom into a migraine. Lots to watch online (episode one of Great Expectations at PBS.org) and Amy Bodden Bowllan has posted Part 1 and Part 2 of our conversation about race and representation in the wake of the murder of Trayvon Martin. I use this poem by Sharon Flake in my poetry workshops, but think I'll include the cover image from now on…

I showed Pratibha Parmar's brilliant film, A Place of Rage, in my classes yesterday. As always, the students were deeply moved and impressed by the profound statements made by Alice Walker, Angela Davis, and June Jordan. Pratibha posted this important Ms. Magazine blog article on Facebook this morning: "From Emmett Till to Trayvon Martin: How Black Women Turn Grief Into Action." And the students are writing on Audre Lorde's essay, "The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action." It's not enough to mourn. You have to channel the pain that is the core of rage into something constructive that can help others in addition to yourself…

April 4, 2012

talking back

The only good thing about bigots is that they usually hang themselves if you give them enough rope. That's just what happened on The Daily Show when Al Madrigal traveled to Arizona to interview a school board member who voted to ban Mexican American Studies in Tucson schools (based on "hearsay," not facts). If you haven't seen the segment, you can watch it here. Debbie Reese has also transcribed the interview and you can find that on her blog, American Indians in Children's Literature. You want to laugh because it's so ridiculous, but the ramifications of this kind of ignorance are very real—and harmful to our youth and the future of the country. This week Amy Bodden Bowllan is featuring Matt de la Peña on her School Library Journal blog; Matt recently visited AZ after his novel, Mexican Whiteboy, was pulled from the shelves. Amy also gave me a chance to reflect on the Trayvon Martin case and its impact on young readers. THIS is what I'm talking about when I say that "the lack of books for children in our communities IS A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH."

The only good thing about bigots is that they usually hang themselves if you give them enough rope. That's just what happened on The Daily Show when Al Madrigal traveled to Arizona to interview a school board member who voted to ban Mexican American Studies in Tucson schools (based on "hearsay," not facts). If you haven't seen the segment, you can watch it here. Debbie Reese has also transcribed the interview and you can find that on her blog, American Indians in Children's Literature. You want to laugh because it's so ridiculous, but the ramifications of this kind of ignorance are very real—and harmful to our youth and the future of the country. This week Amy Bodden Bowllan is featuring Matt de la Peña on her School Library Journal blog; Matt recently visited AZ after his novel, Mexican Whiteboy, was pulled from the shelves. Amy also gave me a chance to reflect on the Trayvon Martin case and its impact on young readers. THIS is what I'm talking about when I say that "the lack of books for children in our communities IS A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH."

Yesterday I told my students that I never used to talk in class; they were amazed to learn that I used to sit in class in college and even in graduate school with my lips sealed shut. And even at the conference in France last month—the keynote speaker was making some really problematic statements, and I sat there hoping someone else would speak up. But no one did, so that's when I raised my hand and tried to keep my voice from shaking with rage…most days I'd rather disappear, but we don't only speak for ourselves. We speak for those who have been silenced. We speak because we've been given a platform and so many others have not.

April 1, 2012

just us

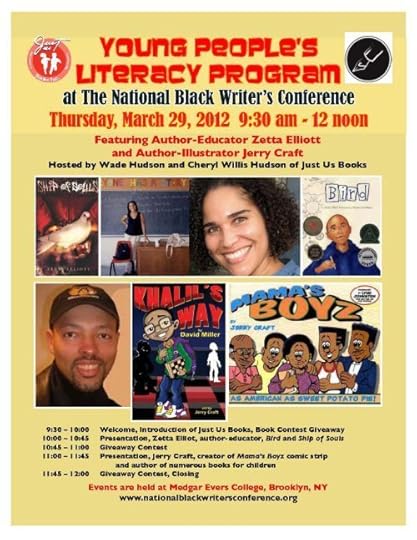

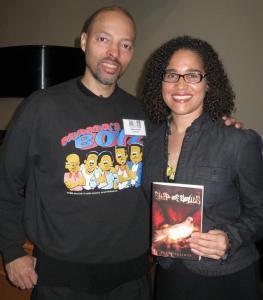

On March 29th I had the chance to share Ship of Souls with students from the Jackie Robinson School in Crown Heights; they were invited to attend the youth program of the National Black Writers Conference held at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn. Cheryl Willis Hudson and Wade Hudson (authors and publishers of Just Us Books) were wonderful hosts and emcees, and the kids were great, too! Unfortunately, I had to dash back to work and so I missed Jerry Craft's presentation, but I'm sure he wowed the crowd.

On March 29th I had the chance to share Ship of Souls with students from the Jackie Robinson School in Crown Heights; they were invited to attend the youth program of the National Black Writers Conference held at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn. Cheryl Willis Hudson and Wade Hudson (authors and publishers of Just Us Books) were wonderful hosts and emcees, and the kids were great, too! Unfortunately, I had to dash back to work and so I missed Jerry Craft's presentation, but I'm sure he wowed the crowd.

March 31, 2012

soon come

To celebrate the end of this ridiculously hectic month, I'm having a day of silence. I also subscribed to HBO in order to watch the second season of Game of Thrones, which airs tomorrow night—at the same time as Masterpiece Theatre's adaptation of Great Expectations! I devoured novels by Dickens when I was in high school, but I also wrote my senior thesis on The Mists of Avalon…and Game of Thrones reminds me of my teenage passion for all things medieval. It also makes me wish they had hired a woman director for at least some of the episodes—maybe then we could avoid the

To celebrate the end of this ridiculously hectic month, I'm having a day of silence. I also subscribed to HBO in order to watch the second season of Game of Thrones, which airs tomorrow night—at the same time as Masterpiece Theatre's adaptation of Great Expectations! I devoured novels by Dickens when I was in high school, but I also wrote my senior thesis on The Mists of Avalon…and Game of Thrones reminds me of my teenage passion for all things medieval. It also makes me wish they had hired a woman director for at least some of the episodes—maybe then we could avoid the  gratuitous female nudity and "rutting" scenes. For every powerful queen there are at least five naked whores prancing around the castle/brothel/tent. It did end with dragons, though, which is what made me sign up for season 2. Yes, they were all perched on the naked body of a white-blonde white woman, and yes, the only women of color in the show are cast as "savages" who dance naked around an open fire…but I'm hooked. If I can grade twenty more papers, then watching Game of Thrones tomorrow night will be my reward.

gratuitous female nudity and "rutting" scenes. For every powerful queen there are at least five naked whores prancing around the castle/brothel/tent. It did end with dragons, though, which is what made me sign up for season 2. Yes, they were all perched on the naked body of a white-blonde white woman, and yes, the only women of color in the show are cast as "savages" who dance naked around an open fire…but I'm hooked. If I can grade twenty more papers, then watching Game of Thrones tomorrow night will be my reward.

I only have two school visits lined up for April, and I'm looking forward to getting back into my usual routine over spring break. I went to the park and the garden yesterday and was amazed to see some cherry trees and magnolias in full bloom and others dropping their white/pink petals already. I almost missed the arrival of spring! Definitely need to slow down a bit.

Ebony Mom Politics recommends Ship of Souls for parents looking to ward off spring break boredom:

My kids will be on spring break soon and by Day 3 I will hear this familiar phrase, "I'm bored." To cure that boredom I am going to let them read Ship of Souls by Zetta Elliott. This novel details the journey of D (Dmitri) an orphaned math whiz, Hakeem, a basketball star and Nyla a spunky Army brat. Their paths intersect when D becomes a tutor for Hakeem who only has eyes for Nyla. In this fantastical tale D meets a magic bird who has the ability to morph into all sorts of things, but the bird has a specific mission for the trio that will ultimately change their lives. This urban fantasy is centered around Brooklyn, and it is exciting to watch them navigate in search of their own truth. This sometimes frightening tale will keep the reader on pins and needles as they watch the trio walk toward their destiny. It successfully combines African history with modern day mystery. The beauty of this story is it is a learning experience and an adventure. I also love that the fact that the reader also gets the opportunity to reflect on the tale with a series of thought-provoking questions at the end. This is a great read for adults and kids alike.

Ship of Souls also got a nice review over at Finding Wonderland. Thoughtful reviews are always appreciated, but critiques by fellow authors are especially meaningful:

Dmitri, or D, is a great narrator—he's a smart kid who's trying to muddle along and be strong in the wake of his mother's death, but that's hard to do when your world has turned upside down and you're living with a foster mother. Endearingly, he wants to do everything right, and he really is a good guy, but he still feels set apart from his classmates at his new school. The two new friends he makes couldn't be more different from one another—Hakeem is a Muslim basketball star D is tutoring in math, and Nyla is a worldly-wise, mouthy military brat who hangs out with the self-confessed "freaks". But they quickly forge a bond when they're drawn into D's adventure. I loved that both Hakeem and Nyla are as multicultural as you can get, from diverse families, but in a way that was still realistic rather than seeming forced. I also liked D's foster mother Mrs. Martin, although I kind of wished she'd had a bigger part somehow.

Lastly, have you signed up for The Book Smugglers' newsletter? I was asked to write something for their April issue, and we'll be giving away five copies of Ship of Souls—so sign up!

March 26, 2012

tea & sympathy

Grading. Grading on the subway. Grading while on line at the burrito place. Grading before going to bed and again first thing in the morning. Sigh. I took a stack of papers with me to France but didn't make much progress, in part because I got off the plane with a cold. The south of France is lovely but French culture doesn't really work for me: I don't drink or smoke, I hate baguette, I'm not crazy about little dogs, and I can't eat cheese. Sitting at a packed outdoor cafe doesn't appeal to this solitary Scorpio, and so when I first arrived on Wednesday, I actually wished I could speed up the clock. I don't like to travel alone, and as a woman—and a woman of color—with only limited French, I felt insecure in Aix-en-Provence (though I generally found the people to be friendlier than Parisians). It's a pretty town (photo above is Cathédrale Saint-Sauveur d'Aix) but it seems people mostly go there to shop, and that was the last thing I wanted to do. I got some ibuprofen and vitamin C from the pharmacy and spent the first couple of nights recuperating at the hotel. Then Laura arrived on Friday

Grading. Grading on the subway. Grading while on line at the burrito place. Grading before going to bed and again first thing in the morning. Sigh. I took a stack of papers with me to France but didn't make much progress, in part because I got off the plane with a cold. The south of France is lovely but French culture doesn't really work for me: I don't drink or smoke, I hate baguette, I'm not crazy about little dogs, and I can't eat cheese. Sitting at a packed outdoor cafe doesn't appeal to this solitary Scorpio, and so when I first arrived on Wednesday, I actually wished I could speed up the clock. I don't like to travel alone, and as a woman—and a woman of color—with only limited French, I felt insecure in Aix-en-Provence (though I generally found the people to be friendlier than Parisians). It's a pretty town (photo above is Cathédrale Saint-Sauveur d'Aix) but it seems people mostly go there to shop, and that was the last thing I wanted to do. I got some ibuprofen and vitamin C from the pharmacy and spent the first couple of nights recuperating at the hotel. Then Laura arrived on Friday  and everything changed—I had a running buddy! A sounding board. A friend. I'm not a big talker but whenever Laura and I get together, we find endless issues to discuss: teaching, grading, the pros and cons of being in the academy, the pros and cons of US & UK publishing, immigration, ambition, relationships. And the conference itself, of course, which was interesting and really well organized. I think both our papers were well received, and we met some interesting people, including American graphic artist/illustrator/professor John Jennings whose hotel room was right across from ours. We ate at Chez Grandmere Friday night and had "authentic Provencale cuisine." The next day we checked out the local bookstores, ambled through the outdoor market, and had pizza in a candlelit, cobble-stoned corner of Aix. We shared our family histories and projected where we'd be in five years. John requires students in his hip hop visuals class to come up with a tag—"What would yours be?" I woke up this morning trying to answer that question. I think I've settled on "bittersweet" or "bittasweet," though it's probably not wise to pick a tag that can be reduced to "b.s." This morning I was at the central branch of the BPL listening to the amazing poetry my two middle school classes created. During our second workshop I asked them to circle ten words that represented the essence of a special memory. A tag is sort of like your essence—if you had to reduce yourself to ONE word, what would it be? I thought about "scribe" but that seemed too one-dimensional. I like bittersweet because it represents contradiction but also balance. In my third workshop with the students

and everything changed—I had a running buddy! A sounding board. A friend. I'm not a big talker but whenever Laura and I get together, we find endless issues to discuss: teaching, grading, the pros and cons of being in the academy, the pros and cons of US & UK publishing, immigration, ambition, relationships. And the conference itself, of course, which was interesting and really well organized. I think both our papers were well received, and we met some interesting people, including American graphic artist/illustrator/professor John Jennings whose hotel room was right across from ours. We ate at Chez Grandmere Friday night and had "authentic Provencale cuisine." The next day we checked out the local bookstores, ambled through the outdoor market, and had pizza in a candlelit, cobble-stoned corner of Aix. We shared our family histories and projected where we'd be in five years. John requires students in his hip hop visuals class to come up with a tag—"What would yours be?" I woke up this morning trying to answer that question. I think I've settled on "bittersweet" or "bittasweet," though it's probably not wise to pick a tag that can be reduced to "b.s." This morning I was at the central branch of the BPL listening to the amazing poetry my two middle school classes created. During our second workshop I asked them to circle ten words that represented the essence of a special memory. A tag is sort of like your essence—if you had to reduce yourself to ONE word, what would it be? I thought about "scribe" but that seemed too one-dimensional. I like bittersweet because it represents contradiction but also balance. In my third workshop with the students  I asked them to make two lists: words others would use to describe them, and words they would use to describe themselves. "Sweet" isn't a word that would appear on either of my lists, but I like "bittasweet" because there's at least a little sugar in me…though these days I'm so stressed out that I'm consuming more sugar than I really need. While I was in France I got thirty emails a day, including two stressful surprises: the book I plan to write about African American YA speculative fiction is going to be announced later this spring at another conference (never mind that I haven't actually finished the proposal), and the editors of an anthology on urban children's literature asked me to contribute a chapter (by June). Trouble is, I haven't had any time just to write for myself and that's why the "bitter" is threatening to overwhelm the "sweet" in me. I don't even have time to record all the details of my time in France. I made a dozen mental notes but can't remember half of them now: sugar cubes in the shape of hearts, Lionel Richie's "Hello" and the theme from Flashdance playing on the shuttle bus radio, a thin sliver of a moon in a starless sky. On the flight back to NYC I watched Puss 'n Boots and (when I wasn't laughing my head off) nearly wept at some of the coloring—I remember seeing a Maxfield Parrish exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum and having a similar reaction. How do you capture the color of a child's dream? Do illustrations teach us how to dream? I need to write but can't afford to let myself drift. Not until spring break. I had tea with a friend this afternoon and she reminded me that there is a time to "frolic" and a time to work. What matters most is that you apply yourself fully to every task, trusting that you will be changed by the experience. I think that's what worries me…

I asked them to make two lists: words others would use to describe them, and words they would use to describe themselves. "Sweet" isn't a word that would appear on either of my lists, but I like "bittasweet" because there's at least a little sugar in me…though these days I'm so stressed out that I'm consuming more sugar than I really need. While I was in France I got thirty emails a day, including two stressful surprises: the book I plan to write about African American YA speculative fiction is going to be announced later this spring at another conference (never mind that I haven't actually finished the proposal), and the editors of an anthology on urban children's literature asked me to contribute a chapter (by June). Trouble is, I haven't had any time just to write for myself and that's why the "bitter" is threatening to overwhelm the "sweet" in me. I don't even have time to record all the details of my time in France. I made a dozen mental notes but can't remember half of them now: sugar cubes in the shape of hearts, Lionel Richie's "Hello" and the theme from Flashdance playing on the shuttle bus radio, a thin sliver of a moon in a starless sky. On the flight back to NYC I watched Puss 'n Boots and (when I wasn't laughing my head off) nearly wept at some of the coloring—I remember seeing a Maxfield Parrish exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum and having a similar reaction. How do you capture the color of a child's dream? Do illustrations teach us how to dream? I need to write but can't afford to let myself drift. Not until spring break. I had tea with a friend this afternoon and she reminded me that there is a time to "frolic" and a time to work. What matters most is that you apply yourself fully to every task, trusting that you will be changed by the experience. I think that's what worries me…

March 20, 2012

au revoir

I woke up feeling ready for this day—my suitcase was packed, my lessons were in order. My flight leaves at 7pm, and I will be heading to the airport just as soon as I administer the midterm in my third and final class of the day. Then I noticed I had a voicemail message so I listened to it before class #1 started and learned that my great aunt passed away earlier this morning in Nevis. I only met my Aunt Maudie once because I've only been to Nevis once before…but she was the matriarch of a large family, and will be sorely missed, I'm sure. I'm planning to return to Nevis this spring and hoped to press her for information about my grandmother, her older sister. Now I'm wondering if I can find a way to wire some money before heading to the airport and on to France. My older brother is adopted, and Maudie is his biological mother—we've no way to reach him. I feel like I'm in the wrong place at the wrong time. Can't do much while I'm at work, and can't do anything really while I'm abroad. Spending all this money to attend this conference and could have bought a ticket to Nevis instead…anyway. Must press on. Will try to blog a bit while I'm in Aix…

I woke up feeling ready for this day—my suitcase was packed, my lessons were in order. My flight leaves at 7pm, and I will be heading to the airport just as soon as I administer the midterm in my third and final class of the day. Then I noticed I had a voicemail message so I listened to it before class #1 started and learned that my great aunt passed away earlier this morning in Nevis. I only met my Aunt Maudie once because I've only been to Nevis once before…but she was the matriarch of a large family, and will be sorely missed, I'm sure. I'm planning to return to Nevis this spring and hoped to press her for information about my grandmother, her older sister. Now I'm wondering if I can find a way to wire some money before heading to the airport and on to France. My older brother is adopted, and Maudie is his biological mother—we've no way to reach him. I feel like I'm in the wrong place at the wrong time. Can't do much while I'm at work, and can't do anything really while I'm abroad. Spending all this money to attend this conference and could have bought a ticket to Nevis instead…anyway. Must press on. Will try to blog a bit while I'm in Aix…

March 18, 2012

pruning

I have finally got my conference paper down to 12 pages! Unfortunately, in my effort to include as many quotes from my interviewees as possible, I cut a really strong passage and *forgot* to paste it into the footnotes. Crap. In that passage I analyzed a troubling review Ship of Souls received from a Canadian bookseller—and one of her critiques was the "unnecessary" inclusion of crude language ("crap" and "pissed off"). I use crap in order to avoid using "sh**"—which is what lots of kids use every day. But that was a minor issue for me. I had more of a problem with her description of Hakeem as "a stereotypical black jock." She did note that he was Muslim, but made no mention of the fact that he's biracial (Senegalese father, Bangladeshi mother), that he's determined to graduate from high school AND college despite his athletic ability, and that he dreams of becoming a chef and opening his own restaurant someday. If he really is a stereotype, I'd love for this reviewer to list the other books that feature a kid like Keem. She couldn't, of course, (especially not in Canada, where there are NO books about contemporary black boys) which was the point I was trying to make in my paper. Bad reviews are part of life for an author; generally we read them, fume a bit, and move on. But when there are only two review journals for children's literature in the country, you really need those reviewers to be on point.

I have finally got my conference paper down to 12 pages! Unfortunately, in my effort to include as many quotes from my interviewees as possible, I cut a really strong passage and *forgot* to paste it into the footnotes. Crap. In that passage I analyzed a troubling review Ship of Souls received from a Canadian bookseller—and one of her critiques was the "unnecessary" inclusion of crude language ("crap" and "pissed off"). I use crap in order to avoid using "sh**"—which is what lots of kids use every day. But that was a minor issue for me. I had more of a problem with her description of Hakeem as "a stereotypical black jock." She did note that he was Muslim, but made no mention of the fact that he's biracial (Senegalese father, Bangladeshi mother), that he's determined to graduate from high school AND college despite his athletic ability, and that he dreams of becoming a chef and opening his own restaurant someday. If he really is a stereotype, I'd love for this reviewer to list the other books that feature a kid like Keem. She couldn't, of course, (especially not in Canada, where there are NO books about contemporary black boys) which was the point I was trying to make in my paper. Bad reviews are part of life for an author; generally we read them, fume a bit, and move on. But when there are only two review journals for children's literature in the country, you really need those reviewers to be on point.

I wanted to say something in my conference paper about the competency of reviewers—cultural competency, which for the most part has nothing to do with race. As I tried to explain to the editor of the journal that ran the review, I'm not qualified to teach Black Studies because I'm black—I'm qualified b/c I've been trained in the field. And several other reviewers—white and black—have noted that the cast of kids in SoS is remarkably diverse. They note that, I think, because they've read enough speculative fiction and African American kidlit to know just what's stereotypical and what's not. Queer kids of color don't often see themselves reflected in MG/YA lit, so my choice to have Nyla question her sexuality was deliberate; this particular reviewer felt the "odd reference to lesbianism" was "unnecessary to the story." But this was the comment that stunned me:

…Canadian children will have to do some quick double think to incorporate the views of the American Revolution presented here in which their ancestors are clearly portrayed as the enemy of the brave Americans.

I still don't know how to process this remark. Is the reviewer saying that Canadian children will feel conflicted because they'll conjure British loyalists while reading the book? There are no references to the British in my novel—in fact, the patriot ghosts recount fending off German soldiers (Hessians). So what's the problem? And I have to wonder which Canadian children she's worried about. I seriously doubt that black children in Canada would read this story and experience anxiety around their loyalty to the Crown. There were black loyalists, of course, but I doubt that's what she's talking about. I suspect this reviewer worries that WHITE Canadian children will be unable to identify with the African American protagonists, and will therefore align themselves with the whites who aren't even present in the novel—the British. Good grief. This reviewer gave Ship of Souls two stars out of four, yet still declared it "recommended." Thanks.

Other African Canadian authors made more concise statements about the issue of race and reviews, so I'll focus on them in my paper. Which it's time to get back to…