Zetta Elliott's Blog, page 74

June 16, 2012

hot mess

Unfortunately I missed the conversation with Terry Boddie last night—migraine. I should have seen that coming—too many trains and planes—but Terry has kindly agreed to answer the questions I prepared for our talk, and I’ll post those on the blog later this month. For now I’m posting my ChLA conference paper. This isn’t the paper I hoped to present—my slides weren’t finished and so I only synched a few with my talk, which means the MLK part of the presentation dropped out. I had about 2/3 of the paper finished before I left for Nevis and figured I could finish the rest on the train to Boston, but I forgot to pack my power cord and so only had about 90 minutes before my laptop shut down. I got to Boston at noon, caught a cab to Simmons College, found the technology lab, pleaded with the student clerk to let me borrow a power cord, and then spent 40 minutes registering online as a “guest” so that I could print my 12-page paper. Arrived at the room five minutes before our session began at 1pm and was allowed to catch my breath and present at the end instead of the beginning. I got some positive feedback afterward and really appreciate that the audience was willing to engage with these issues. And it helped a *lot* that I was up there with three other black women (and “real” kidlit scholars): Michelle Martin, Rachelle Washington, and Nancy Tolson. It was also nice to look out and see some familiar and friendly faces in the audience (thanks, Sarah!). For the second year in a row, I presented and then split, but for the second year in a row I found the experience rewarding and very worthwhile. This paper needs work but I have another essay due July 1 so it’ll just have to be what it is…

Unfortunately I missed the conversation with Terry Boddie last night—migraine. I should have seen that coming—too many trains and planes—but Terry has kindly agreed to answer the questions I prepared for our talk, and I’ll post those on the blog later this month. For now I’m posting my ChLA conference paper. This isn’t the paper I hoped to present—my slides weren’t finished and so I only synched a few with my talk, which means the MLK part of the presentation dropped out. I had about 2/3 of the paper finished before I left for Nevis and figured I could finish the rest on the train to Boston, but I forgot to pack my power cord and so only had about 90 minutes before my laptop shut down. I got to Boston at noon, caught a cab to Simmons College, found the technology lab, pleaded with the student clerk to let me borrow a power cord, and then spent 40 minutes registering online as a “guest” so that I could print my 12-page paper. Arrived at the room five minutes before our session began at 1pm and was allowed to catch my breath and present at the end instead of the beginning. I got some positive feedback afterward and really appreciate that the audience was willing to engage with these issues. And it helped a *lot* that I was up there with three other black women (and “real” kidlit scholars): Michelle Martin, Rachelle Washington, and Nancy Tolson. It was also nice to look out and see some familiar and friendly faces in the audience (thanks, Sarah!). For the second year in a row, I presented and then split, but for the second year in a row I found the experience rewarding and very worthwhile. This paper needs work but I have another essay due July 1 so it’ll just have to be what it is…

“Stranger Than Fiction: Depicting Trauma in African American Picture Books”

or “One Hot Mess”

This paper is a hot mess. I begin with this assertion because it serves as a warning to you, my audience, while also engaging with Bruce Sterling’s definition of “slipstream:”

This is a kind of writing which simply makes you feel very strange; the way that living in the late twentieth century makes you feel, if you are a person of a certain sensibility.

It’s very common for slipstream books to screw around with the representational conventions of fiction, pulling annoying little stunts that suggest that the picture is leaking from the frame and may get all over the reader’s feet.”[i]

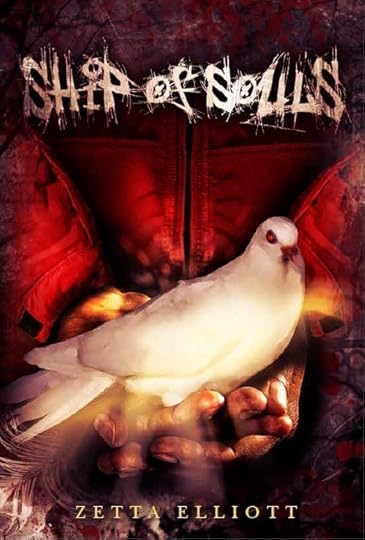

Sterling’s essay is a bit murky, and I confess that I am wary of debates within the field of science fiction since they often end badly for people of color. But I do like his idea of a young, badass genre “screwing around with convention.” As a nontraditional scholar I regularly fight against certain stifling conventions, and as a black feminist writer—“a person of a certain sensibility”—I often feel quite strange: never more so than when I am presenting at an academic conference, and most particularly when I am addressing the issue of race and equity in the children’s publishing industry. Sterling asserts that, “Many slipstream books [fall]  through the yawning cracks between categories.” This is another point to which I can relate. My third book for young readers, Ship of Souls, was published by AmazonEncore in February of this year; it’s a unique blend of realistic urban fiction, historical fiction, and multicultural speculative fiction. Ship of Souls received a starred review from Booklist and was added to their list of Top Ten Sci-Fi/Fantasy Youth Titles.

through the yawning cracks between categories.” This is another point to which I can relate. My third book for young readers, Ship of Souls, was published by AmazonEncore in February of this year; it’s a unique blend of realistic urban fiction, historical fiction, and multicultural speculative fiction. Ship of Souls received a starred review from Booklist and was added to their list of Top Ten Sci-Fi/Fantasy Youth Titles.

I live in and write about New York City; last month I conducted author presentations and writing workshops in twenty schools and libraries across the city. Yet despite my actual presence in NYC and my virtual presence in the blogosphere, I still had to petition the NYPL to add Ship of Souls to their collection. The person in charge of acquisitions, Betsy Bird, explained that she normally finds books through Kirkus Reviews, and since Kirkus opted not to review Ship of Souls, it didn’t come to her attention. I suspect that my books are probably unfamiliar to many of you, and in this paper I want to consider just what “familiarity” within the children’s publishing industry means for writers who may be deemed foreign, exotic, rebellious, or simply “messy.” Richard Horton argues that, “Slipstream tries to make the familiar strange—by taking a familiar context and disturbing it with SFnal/ fantastical intrusions.”[ii] This is what I try to do with my own fiction, inserting historical and fantastical elements in order to transform the familiar urban landscape and the white-dominated field of science  fiction and fantasy. In my capacity as an activist blogger, I regularly attempt to disrupt the “familiar context” of children’s publishing with an intrusion—or an infusion—of social justice and critical race theory. Today, after considering the narrow representation of trauma in African American picture books, I will “wake the past,” drawing upon Martin Luther King’s 1963 “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” to contrast historical and contemporary efforts to challenge white supremacy and achieve equity.

fiction and fantasy. In my capacity as an activist blogger, I regularly attempt to disrupt the “familiar context” of children’s publishing with an intrusion—or an infusion—of social justice and critical race theory. Today, after considering the narrow representation of trauma in African American picture books, I will “wake the past,” drawing upon Martin Luther King’s 1963 “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” to contrast historical and contemporary efforts to challenge white supremacy and achieve equity.

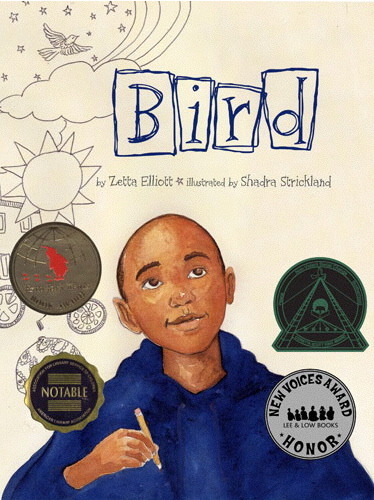

When President Michelle Martin invited me to join this panel, my initial impulse was to decline. I am not a children’s literature scholar, and only began researching racism in publishing after surviving a decade of rejection as a young writer. In fact, I finally accepted a life in the academy only after I finally accepted the fact that I was not going to sell my first novel for a six-figure advance. My academic training allows me to think critically—if not dispassionately—about race and representation within the field of children’s literature. But I know that for some, my critique of the publishing industry will automatically be dismissed as “sour grapes,” and it is true that I likely never would have investigated the players in this game had I succeeded in placing more of my manuscripts. As it is, despite winning a number of awards for my first picture book, Bird, about 80% of my work remains unpublished, and I admit that I began studying the industry in order to understand how so many editors could praise my writing and yet refuse to publish my work.

When I discovered that only 3% of children’s book authors published annually in the US were black, I abandoned my naïve assumption that publishing was a matter of merit; thanks to statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, I now had proof that the problem was institutional and systemic. Whatever others might think of my so-called “bad attitude” (I’m often dismissed as just another angry black woman), there was something much bigger and more sinister at play; black writers in North America face much steeper odds than the average white writer. As John K. Young explains in Black Writers, White Publishers (2006), “…what sets the white publisher-black author relationship apart is the underlying social structure that transforms the usual unequal relationship into an extension of a much deeper cultural dynamic. The predominantly white publishing industry reflects and often reinforces the racial divide that has always defined American society” (4).

I grew up in Canada on the outskirts of Toronto; I attended majority-white schools and then, after college, fled to NYC where I lived in a majority-black environment for the first time in my life. I immediately became immersed in and engaged with the culture and the struggles of “my people,” and vowed that I would never live as a “minority” ever again. But life after graduate school and outside of NYC required me to forsake that vow, and as I began teaching at majority-white institutions, I felt that all too familiar strangeness—the estrangement I experienced in my youth returned, along with all the defenses I acquired over the years in order to combat my own erasure. I was simultaneously conspicuous yet invisible as the only black professor in an all-white department, and/or the only feminist in a department full of patriarchal men, and/or the only unmarried, child-free, thirty-something artist on a short-term contract in a department full of driven, stressed out junior faculty desperately seeking tenure.

Now—here’s where things get a bit messy because I want to talk about the familiarity and strangeness of my estrangement, and then link that to dominance within the children’s publishing industry. To be estranged is “to be removed from customary environment or associations,” and so in that sense, I am not entirely estranged within the academy nor the publishing industry because the first twenty years of my life were spent in rooms much like this one. Majority-white spaces are, within the professional world, far too “customary” and so are familiar to people of color like me. Estrangement also means alienation, of course: “isolation from a group or an activity to which one should belong or in which one should be involved.” Estrangement can also involve the “loss or lack of sympathy;” and to estrange is “to arouse hostility or indifference where there had formerly been love, affection, or friendliness.” [Dr. King referred to segregation as a kind of estrangement: “Is not segregation an existential expression of man's tragic separation, his awful estrangement, his terrible sinfulness?”]

Taken together, these definitions accurately describe my relationship to the children’s literature community. As a scholar and author, I feel as though I should belong and be involved, and yet I currently find myself experiencing a “loss or lack of sympathy” for those groups that claim to share my belief in the transformative power of books. And so when Michelle asked me to join this panel, I had my reservations because I know that when I speak the truth as “a person of a certain sensibility,” collegiality often vanishes. Michelle is the first black president of this association, and I feel she has already gone out on a limb by citing my 2011 ChLA conference paper in her membership letter. Like another first black president, she runs the risk of being accused of “tribalism,” and I do worry that she may be judged guilty by her association with me. I’ve found that since I began publicly critiquing racism in the children’s publishing industry in 2009, I have become something of a tar baby. It’s clear to me that I make people uncomfortable, not by “pulling an annoying little stunt” but by pointing out the ways white supremacy goes unchecked in the children’s literature community. I consider this discomfort necessary, however, for complacency is largely to blame for the current state of the industry. For decades, critiques have been made about the lack of equity in children’s publishing, yet here we are in the twenty-first century—so-called “minority babies” now make up the majority of births in the US, and yet 95% of books published for children annually are still written by whites, and these authors find their mirrors in the team of professionals who acquire, edit, publish, and market those books.

When I started blogging in 2008, I never anticipated that my blog would operate as a site of resistance. After reading my most recent essay on the kidlit community’s silence around the shooting of Trayvon Martin, a close friend who teaches at a women’s college in MN urged me yet again to compile all my essays in a book. I assured her, yet again, that I would do no such thing, though I briefly entertained the idea this past spring. My book proposal was also a bit “messy,” but attempted to combine two areas of interest: racism in publishing and African American speculative fiction for youth. Unlike my prospective editor, I felt the two topics were inextricably linked—indeed, I think any consideration of children’s literature should begin with an analysis of bias within the industry. It is a mistake to treat children’s literature as organic or naturally occurring when we all know that it is produced and therefore shaped by a commercial industry dominated by middle-class whites who are predominantly straight women.

And so, as I now turn to the depiction of trauma in African American picture books, I must begin with the problem of lack. How do I analyze books that do not exist, and how do I prove that racial dominance and discomfort are to blame? When Michelle approached me about this panel and I overcame my initial resistance, my first thought was to write something about lynching. My dissertation was on representations of rape and lynching in African American literature, and I have long been interested in the ability of children to comprehend the many race-based atrocities that fill this nation’s history. There are plenty of picture books about slavery and the Civil Rights movement—tragic scenarios, one could argue, that offer space for whites to function as saviors or at least as participants in a triumphant narrative. But where are the books about the brutal race riots in Tulsa and Rosewood and Newark and L.A.? African American children, women, and men were lynched for nearly a century in this country—where are the picture books to reflect that fact? Will there be a picture book to help children understand what happened to Trayvon Martin? Do we have enough picture books that address the mass incarceration of black men and the growing incarceration of black women? Do children in this country understand the holocaust that was the Middle Passage?

Kenneth Kidd argues that, “Since the early 1990s, children’s books about trauma, especially the trauma(s) of the Holocaust, have proliferated, as well as scholarly treatments of those books. Despite the difficulties of representing the Holocaust, or perhaps because of them, there seems to be consensus now that children’s literature is the most rather than the least appropriate literary forum for trauma work.”[iii] Acknowledging that African American novels about trauma “have yet to be reclaimed by the emergent field of trauma studies,” Kidd then concludes that “many if not most contemporary children’s books about African American life are historical and often traumatic in emphasis, so pervasive is the legacy of slavery, Reconstruction, and the fight for civil rights.”[iv]

Certainly, the devastating and lasting impact of enslavement, segregation, and the denial of voting rights manifests in the literature produced by African American authors. But again, it seems to me that the limited range of books by or about African Americans should not be read as proof of some organic impulse. If there appears to be a preoccupation with this traumatic history, we must at least consider the curatorial impact of editors who are almost exclusively nonblack. I know that I have twenty unpublished picture book manuscripts, and less than half deal with trauma but those stories about frolicking in the snow are rarely if ever requested by editors. My peers and I have often wondered whether those working in the children’s publishing industry prefer distant historical moments involving African Americans that, though undeniably traumatic, have some sort of “happy ending”—slavery was terrible, but brave white soldiers fought the Civil War to abolish it forever. Segregation was terrible, but brave white citizens marched to end it. Racism was terrible, but white voters elected Barack Obama!

Kidd argues that, “Of all contemporary genres of children’s literature, the picture book offers the most dramatic and/or ironic testimony to trauma, precisely because the genre is usually presumed innocent.”[v] He then points to the rapidity with which the US publishing industry produced picture books about 9/11, an event that Kidd calls “the ultimate and easily knowable affront to self and nation.”[vi] I haven’t been able to place my picture book manuscript about 9/11, “The Girl Who Swallowed the Sun.” Nor have I found a publisher willing to consider my story about lynching as a motivating factor behind the Great  Migration. When I first started submitting the manuscript for Bird, it was rejected over and over—one editor at the Canadian press, Annick, declared that it was “too sad;” Lee & Low rejected the story twice before it won their New Voices Honor Award. When an established writer friend kindly put me in touch with her editor, my agent submitted An Angel for Mariqua, my chapter book manuscript about an unexpected friendship between a teen whose mother is dying of AIDS and a little girl whose mother is incarcerated. The feedback we received indicated that the editor found the protagonist’s anger uncomfortable and therefore unacceptable, even though the mentoring relationship that develops helps the little girl to manage her anger. An editor at Viking who read my time travel novel, A Wish After Midnight, which ends with an Afro-Panamanian teen and her Rastafarian boyfriend fleeing the NYC Draft Riots of 1863, declared it “unoriginal.” An easy way, perhaps, of side-stepping the issues of racial inequality and outright violence faced by African Americans in 1863 and 2001.

Migration. When I first started submitting the manuscript for Bird, it was rejected over and over—one editor at the Canadian press, Annick, declared that it was “too sad;” Lee & Low rejected the story twice before it won their New Voices Honor Award. When an established writer friend kindly put me in touch with her editor, my agent submitted An Angel for Mariqua, my chapter book manuscript about an unexpected friendship between a teen whose mother is dying of AIDS and a little girl whose mother is incarcerated. The feedback we received indicated that the editor found the protagonist’s anger uncomfortable and therefore unacceptable, even though the mentoring relationship that develops helps the little girl to manage her anger. An editor at Viking who read my time travel novel, A Wish After Midnight, which ends with an Afro-Panamanian teen and her Rastafarian boyfriend fleeing the NYC Draft Riots of 1863, declared it “unoriginal.” An easy way, perhaps, of side-stepping the issues of racial inequality and outright violence faced by African Americans in 1863 and 2001.

Laura Atkins has written several articles on the ways in which white privilege operates within the children’s publishing industry. Laura is a friend of mine, and she was the first editor who saw merit in my work and asked to meet face to face. Regrettably, Laura left publishing for academia, though she still manages to work as a freelance editor, often with writers of color who turned to self-publishing after finding themselves locked out of the mainstream publishing industry. Laura’s work led me to an essay by Joel Taxel, “Children’s Literature at the Turn of the Century: Toward a Political Economy of the Publishing Industry.” Taxel rightly contends that, “While obvious to those within the industry, the impact of the business side of children’s literature has not been given the sustained and systematic scrutiny it deserves by children’s literature scholars and the educational community in general.”[vii] Yet as thorough, important, and impressive as Taxel’s article is, his analysis of the corporatization of publishing includes only a limited consideration of racial dominance within the industry. He acknowledges that,

Fear of controversy undoubtedly has led some cross-cultural writers and their editors to stick to safer, simpler books or to avoid writing and publishing books with complex and divisive issues and themes (e.g., racial conflict, violence, sex and sexuality, etc)…Novels of this sort are anathema in many communities, especially in conservative times, and many teachers believe they would risk losing their jobs if they taught books that addressed issues of racial conflict and violence, sex and sexuality, etc. in their classrooms. Publishers are mindful of the way these attitudes impact sales.[viii]

I believe Taxel is correct to conclude that publishers are primarily concerned with profit, but what is left unsaid is the extent to which editors, marketers, teachers, and librarians may fear something other than diminished profits and/or the loss of their job. The books do not exist because the WILL does not exist to directly address this nation’s long history of white supremacy and white privilege. Just look at what’s happening in Arizona with the dismantling of the Mexican American Studies Program—its social justice and cultural heritage curriculum has been accused of generating “resentment toward a race or class of people,” meaning whites.

I have no doubt that some of you have been scribbling down titles that you feel must have escaped my attention. “What about Marilyn Nelson’s A Wreath for Emmett Till?” you will say. “Or Tom Feelings’ Middle Passage?” I call this phenomenon the “big fish, small pond” syndrome, which ensures that a handful of authors (writing approved and/or “daring” narratives) are celebrated while emerging talent often is left undiscovered and/or undeveloped. Arundhati Roy calls this the “new racism,” which she explains using this brilliant analogy:

I have no doubt that some of you have been scribbling down titles that you feel must have escaped my attention. “What about Marilyn Nelson’s A Wreath for Emmett Till?” you will say. “Or Tom Feelings’ Middle Passage?” I call this phenomenon the “big fish, small pond” syndrome, which ensures that a handful of authors (writing approved and/or “daring” narratives) are celebrated while emerging talent often is left undiscovered and/or undeveloped. Arundhati Roy calls this the “new racism,” which she explains using this brilliant analogy:

Every year, the National Turkey Federation presents the US president with a turkey for Thanksgiving. Every year, in a show of ceremonial magnanimity, the president spares that particular bird (and eats another one). After receiving the presidential pardon, the Chosen One is sent to Frying Pan Park in Virginia to live out its natural life. The rest of the 50 million turkeys raised for Thanksgiving are slaughtered and eaten on Thanksgiving Day. ConAgra Foods, the company that has won the Presidential Turkey contract, says it trains the lucky birds to be sociable, to interact with dignitaries, school children and the press.

That’s how new racism in the corporate era works. A few carefully bred turkeys – the local elites of various countries, a community of wealthy immigrants, investment bankers, the occasional Colin Powell, or Condoleezza Rice, some singers, some writers (like myself) – are given absolution and a pass to Frying Pan Park.

The remaining millions lose their jobs, are evicted from their homes, have their water and electricity connections cut, and die of AIDS. Basically, they’re for the pot. But the fortunate fowls in Frying Pan Park are doing fine.

I don’t want a handful of books on the historical and ongoing trauma experienced by African Americans. One or two books about lynching will not suffice because those brutal murders were not an aberration; for too long in this country—all over this country—lynching was “the norm.” It did not disrupt everyday life; it was a regular part of it. I am reminded here of Laura S. Brown’s work on the gendering of trauma diagnosis, and how everyday experiences that devastate women—like incest, sexual assault, and harassment—did not constitute “an event outside the range of human experience” and so were not initially considered genuine causes of trauma. She explains:

“Human experience” as referred to in our diagnostic manuals, and as the subject for much of the important writing on trauma, often means “male human experience” or, at the least, an experience common to both women and men. The range of human experience becomes the range of what is normal and usual in the lives of men of the dominant class; white, young, able-bodied, educated, middle-class, Christian men. Trauma is thus that which disrupts these particular human lives, but no other. War and genocide, which are the work of men and male-dominated culture, are agreed-upon traumas; so are natural disasters, vehicle crashes, boats sinking in the freezing ocean.[ix]

This definition, Brown contends, has devastating consequences for women, and I would argue, equally damaging consequences for people of color who live with the effects of racism and social injustice on a daily basis:

What purposes are served when we formally define a traumatic stressor as an event outside of normal human experience and, by inference, exclude those events that occur at a high enough base rate in the lives of certain groups that such events are in fact, normative, “normal” in a statistical sense? I would argue that such parameters function so as to create a social discourse on “normal” life that then imputes psychopathology to the everyday lives of those who cannot protect themselves from these high base-rate events and who respond to these events with evidence of psychic pain. Such a discourse defines a human being as one who is not subject to such high base-rate events and conveniently consigns the rest of us to the category of less than human, less than deserving of fair treatment. (103)

And, therefore, less deserving of equal representation in children’s literature.

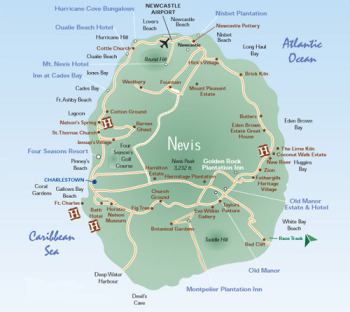

Yesterday I returned from a week-long trip to Nevis, the Caribbean island where my father’s family originates. I’m not exactly rugged, but I am Canadian—I grew up camping and romping around outdoors, and didn’t imagine I’d have any trouble hiking up Nevis Peak. However, this particular mountain—a dormant volcano covered in rainforest—was not at all what I expected. It was practically vertical, and scaling the mucky, rocky slope laced with roots proved too much for me. As my guide urged me on, I found myself repeating one question over and over in my mind: “Why am I doing this?” Just to see if I can make it to the top? Nevis Peak is usually cloaked in fog, so when we turned back at the halfway point and returned to the base, my guide pointed out that we probably wouldn’t have been able to see much anyway. The next day I could barely walk—for DAYS I could barely walk. Every muscle in my body ached. “I’ll train and come back and climb this darn mountain!” I vowed. But then I thought, is that really the best use of my time and energy?

I have reached the same conclusion regarding the children’s publishing industry. I had hoped the US would follow the UK’s lead and adopt a Publishing Equalities Charter as implemented by DIPNET. But as far as I can tell, all we have so far is the Children’s Book Center’s new “Diversity Committee,” which is composed entirely of industry insiders whose primary goal, it seems, is not to collect data on hiring practices but to maintain a bibliography and “keep the conversation going.” Of course, you can keep talking without actually proposing anything new. Which is how I’m starting to feel. Bruce Sterling talks of a “parody of the mainstream”—I see this Diversity Committee as something of a parody, not in the sense that it intends to mock DIPNET, but that it is instead “a feeble or ridiculous imitation.”

I selected a number of quotes from Dr. King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” to share with you, but I haven’t the time or energy to go through them all now. [Here's one:

I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to "order" than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: "I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action"; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man's freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a "more convenient season." Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.]

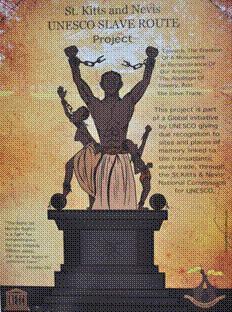

I have decided instead to devote my time and energy from this point forward to finishing the two novels I have underway and the three new book projects I started this past spring. While in Nevis I followed the newly developed “Heritage Trail” but noticed there was little if any mention made of the experiences of the enslaved men and women who made the tiny island one of the richest sugar producers of the 18th century. When I asked about this I was told that the historical society’s membership consisted primarily of white expats from Canada, the US, and the UK. The island recently joined UNESCO’s Slave Route Project and they plan to develop a school curriculum around slavery in Nevis. I see a role for myself in that project, and I hope to have greater success “screwing around with convention” on that Caribbean island than I have had here in North America.

I have decided instead to devote my time and energy from this point forward to finishing the two novels I have underway and the three new book projects I started this past spring. While in Nevis I followed the newly developed “Heritage Trail” but noticed there was little if any mention made of the experiences of the enslaved men and women who made the tiny island one of the richest sugar producers of the 18th century. When I asked about this I was told that the historical society’s membership consisted primarily of white expats from Canada, the US, and the UK. The island recently joined UNESCO’s Slave Route Project and they plan to develop a school curriculum around slavery in Nevis. I see a role for myself in that project, and I hope to have greater success “screwing around with convention” on that Caribbean island than I have had here in North America.

[Final slide:

In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.

~ Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

"The Trumpet of Conscience,” 1967]

[i] “Slipstream” by Bruce Sterling.

[ii] “On the Net: Slipstream” by James Patrick Kelly.

[iii] Kenneth B. Kidd, “‘A’ is for Auschwitz: Psychoanalysis, Trauma Theory, and the ‘Children’s Literature of Atrocity,’” Children’s Literature, Volume 33, 2005, 120.

[iv] Kidd, 133-134.

[v] Kidd 137.

[vi] Kidd 137.

[vii] Taxel 146.

[viii] Taxel 179.

[ix] Laura S. Brown, “Not Outside the Range: One Feminist Perspective on Psychic Trauma,” in Trauma: Explorations in Memory, edited by Cathy Caruth (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1995) 101.

June 15, 2012

trains & planes

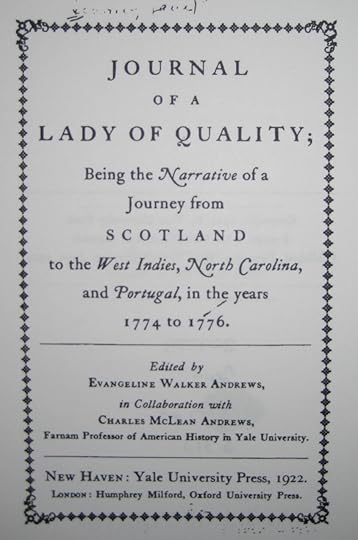

I miss seeing the mountain. I still wake with the birds, and the mourning doves here in Brooklyn sound just like the ones in Nevis. Yesterday I took the subway to Penn Station to catch my 8am train, which got me to Boston in about four hours. I delivered my paper, caught up with some friends, and then got back on the train and reached Brooklyn five hours later. Was actually too tired to sleep but crashed around 1am knowing I had a lot to do today. Now I’m ready to crash again and only made it through half of my To Do list—wrapped and shipped about 20 books and will send the rest tomorrow. Need to work on my talk for tonight and I’m tempted to read this journal that arrived today, but right now I need a nap! Yesterday’s panel at the ChLA conference was amazing—definitely want to blog about that but for now I need some shuteye. It’s strange being in the city again after driving all around the island and seeing birds at my breakfast table and goats roaming the streets. The sea, the hills. The past still present in so many ways…

I miss seeing the mountain. I still wake with the birds, and the mourning doves here in Brooklyn sound just like the ones in Nevis. Yesterday I took the subway to Penn Station to catch my 8am train, which got me to Boston in about four hours. I delivered my paper, caught up with some friends, and then got back on the train and reached Brooklyn five hours later. Was actually too tired to sleep but crashed around 1am knowing I had a lot to do today. Now I’m ready to crash again and only made it through half of my To Do list—wrapped and shipped about 20 books and will send the rest tomorrow. Need to work on my talk for tonight and I’m tempted to read this journal that arrived today, but right now I need a nap! Yesterday’s panel at the ChLA conference was amazing—definitely want to blog about that but for now I need some shuteye. It’s strange being in the city again after driving all around the island and seeing birds at my breakfast table and goats roaming the streets. The sea, the hills. The past still present in so many ways…

June 14, 2012

Friday Night

June 13, 2012

parting shot

I’ve only got a couple photos of myself here in Nevis—next time I’ll ask others to take the camera so that I’m actually in some of the shots! After breakfast I tried to take a few self-portraits outside but they didn’t turn out so well…I wish I could snap my fingers and be home already. Instead of taking a taxi to the ferry, the ferry to the dock, another taxi to the airport, a flight to JFK, and then a cab or train to Brooklyn. Probably a cab! This has been an amazing journey, and I thank all of you for following along and providing support and encouragement. I don’t have my paper finished for tomorrow’s conference so will have to work on that tonight; on Friday evening I’m moderating a discussion with Terry Boddie at the Kedar Gallery in Newark. So this weekend I will spread out all my notes, photos, pamphlets, books, and maps to try to figure out how these pieces fit together. I think my grant application will be much stronger now that I’ve started the proposed project. Three hummingbird sightings this past week…

I’ve only got a couple photos of myself here in Nevis—next time I’ll ask others to take the camera so that I’m actually in some of the shots! After breakfast I tried to take a few self-portraits outside but they didn’t turn out so well…I wish I could snap my fingers and be home already. Instead of taking a taxi to the ferry, the ferry to the dock, another taxi to the airport, a flight to JFK, and then a cab or train to Brooklyn. Probably a cab! This has been an amazing journey, and I thank all of you for following along and providing support and encouragement. I don’t have my paper finished for tomorrow’s conference so will have to work on that tonight; on Friday evening I’m moderating a discussion with Terry Boddie at the Kedar Gallery in Newark. So this weekend I will spread out all my notes, photos, pamphlets, books, and maps to try to figure out how these pieces fit together. I think my grant application will be much stronger now that I’ve started the proposed project. Three hummingbird sightings this past week…

Yesterday’s visit at my cousin’s school was great—super nice teachers (one from Canada!) and very engaged kids—only one shy little girl in a group of about eight boys with lots to say. I will be sending so many books back to Nevis! Books for the library, books for the school, books for all my aunt’s friends who want to read my work. Did you know that Nevis has a 98% literacy rate? One of the highest in the world…

Better finish packing. Back to Brooklyn!

June 12, 2012

back to school

I know I fussed about all those school visits last month, but I miss working with kids. Yesterday I caught the bus (van) back to the hotel and it was full of uniformed school children. I sat alone at the back until we pulled up to another school and half a dozen little boys piled in and filled the back seat. The littlest one accidentally stepped on my toe and looked up at me with a blend of awe and fear—I managed to keep a straight face as he softly apologized. I wanted to ask them what they do for fun once school is out, which books they love to read, but I don’t know these kids that way. Yet. Today I head over to my cousin’s school where I’ll speak to her mixed class of 1st–4th graders. I won’t have my powerpoint presentation to fall back on, so will answer their questions and ask a few of my own. Yesterday I received a lovely email from a teacher in Harlem:

I know I fussed about all those school visits last month, but I miss working with kids. Yesterday I caught the bus (van) back to the hotel and it was full of uniformed school children. I sat alone at the back until we pulled up to another school and half a dozen little boys piled in and filled the back seat. The littlest one accidentally stepped on my toe and looked up at me with a blend of awe and fear—I managed to keep a straight face as he softly apologized. I wanted to ask them what they do for fun once school is out, which books they love to read, but I don’t know these kids that way. Yet. Today I head over to my cousin’s school where I’ll speak to her mixed class of 1st–4th graders. I won’t have my powerpoint presentation to fall back on, so will answer their questions and ask a few of my own. Yesterday I received a lovely email from a teacher in Harlem:

I just wanted to say a huge thank you to you for coming and visiting with my 6th grade class at **** Academy. My students had so much fun working with you, and even more fun working on their speculative fiction stories (which we hope to complete this week). You had such a huge impact on my kids. I’m watching my students push themselves to improve as writers in ways they haven’t tried before. Some students who have stumbled to find points of entry into class activities this year have finally found success and enjoyment as a result of the work you did with them in the classroom, and for that I am forever grateful.

That particular collaboration worked so well because Behind the Book knows how to select the very best teachers…

This is my last full day here in Nevis. I have a lot more work to do, but I think I’ve absorbed about as much as I can for now. It will take months for me to fully “unpack” everything I’m bringing back. Yesterday I stopped at the police station but no one had any idea of how to find a record of my grandmother’s institutionalization; I’ll try the hospital later today. I went to the registrar’s office and flipped through two big books of birth records but didn’t find my great-grandparents. Many babies born before 1900 weren’t named at birth, it seems—or not at the time of registration. So I scanned the column that listed the name of the mother…interesting to see how certain names appeared over and over, sometimes because women had multiple children and other times because certain names were clearly popular: Keziah, Eliza Jane, Dorcas, Rosetta. Just not the Jane and Eliza I was looking for.

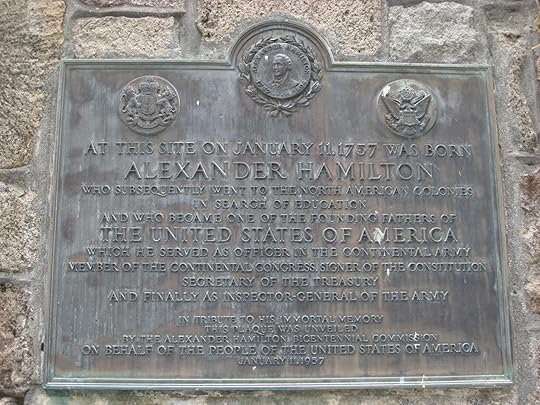

I spent the morning at the Alexander Hamilton House Museum. They had a small section on slavery, which was interesting, and I had a great conversation with the museum attendant. She confirmed what I had suspected: that Alexander Hamilton was an octoroon! His maternal grandfather, a doctor, lost his wife and so remarried a creole woman who was mixed race (mulatto). They had a daughter, Rachel, who would have been a quadroon (one quarter black) and she in turn had Alexander! Everything’s mixed here, and everyone’s connected it seems. This plaque (right) explains that John Smith, before founding Jamestown, VA, stopped at Nevis for 6 days back in 1607…we’re all migrants and have been for centuries.

I spent the morning at the Alexander Hamilton House Museum. They had a small section on slavery, which was interesting, and I had a great conversation with the museum attendant. She confirmed what I had suspected: that Alexander Hamilton was an octoroon! His maternal grandfather, a doctor, lost his wife and so remarried a creole woman who was mixed race (mulatto). They had a daughter, Rachel, who would have been a quadroon (one quarter black) and she in turn had Alexander! Everything’s mixed here, and everyone’s connected it seems. This plaque (right) explains that John Smith, before founding Jamestown, VA, stopped at Nevis for 6 days back in 1607…we’re all migrants and have been for centuries.

I walked over to the alley—a narrow drive with high stone walls that marks all that remains of the original slave depot. Then I met Amba and Dianne for lunch at a nearby cafe that’s on the site of Amba’s former family home. We talked for more than two hours and could have kept on going—it was great to get the perspective of other “returnees,” people who have ties to Nevis but lived most of their lives abroad. We discussed the cost of living, the artist’s need for community, and the challenge of learning new ways of doing things to shift from “outsider” to “insider.” Dianne also shared *her* family research, which indicates that our shared Hood ancestors were of Portuguese Jewish descent. My cousin in Canada confirmed this, and added that her great-aunt moved to Panama at some point. It’s dizzying, all this information! But it’s also another point of entry, another open door…

June 11, 2012

waking dream

Up at 2am. I’ve *never* had insomnia like this before. Once a month I’ll have a restless night but I’ve never found myself progressively losing sleep like this. It was happening in Brooklyn, too—over the past couple of months I started to wake at six, then five, then four. So what could it mean? Around 4am this morning I decided that it must be related to my ancestor search. Each time I find another generation and reach farther into the past, I lose an hour of sleep! The only good thing about this is that I have moments of lucidity while self-directing my waking dreams. I realized this morning that I want to open a museum. Not just an arts center, but a museum. What I haven’t found here in Nevis so far is a critical, comprehensive examination of slavery. The perspective of colonizers and slave owners is still being privileged—the one ghost story that’s mentioned in the tourist material I’ve gathered is a white woman whose fiance shot her brother in a duel and then proposed to another woman. So she shut herself up in her great house and now haunts the crumbling remains. THAT is the ghost story we’re supposed to care about? I realize the intent is not to alienate tourists who are primarily white, but I think it’s a mistake to assume that whites don’t want to know the truth about slavery. In fact, the greater risk is getting too deep, too graphic, and turning the past into another kind of exotic artifact. I mean, we have to have a conversation about language—what’s in a name? Why does the word “plantation” trigger positive associations for tourists and negative associations for me? I can already see a panel in my museum that will list “Ways to Be a Better Tourist.” All the grant-writing experience I’ve been accumulating will come in handy because I’ll need a major grant to make this happen. Everything prepares you for what’s next. I’ve been teaching this course on neo-slave narratives, and now I can select the best slavery novels for my museum bookstore. I’m going to enlarge those slave registers and line the walls with them. I’ll find an artist to develop a rendition of the mass suicide that took place in 1736 when 100 slaves jumped from the Prince of Orange slave ship anchored off the coast of Nevis. The history book I’m reading suggests it was a “cruel joke” that prompted an enslaved man to board the ship with his owner and tell the slaves that they were to be eaten once they were taken ashore. Maybe what he really said was, “Life as a slave on this island is unbearable,” and the newly arrived Africans decided death was the better option.

Up at 2am. I’ve *never* had insomnia like this before. Once a month I’ll have a restless night but I’ve never found myself progressively losing sleep like this. It was happening in Brooklyn, too—over the past couple of months I started to wake at six, then five, then four. So what could it mean? Around 4am this morning I decided that it must be related to my ancestor search. Each time I find another generation and reach farther into the past, I lose an hour of sleep! The only good thing about this is that I have moments of lucidity while self-directing my waking dreams. I realized this morning that I want to open a museum. Not just an arts center, but a museum. What I haven’t found here in Nevis so far is a critical, comprehensive examination of slavery. The perspective of colonizers and slave owners is still being privileged—the one ghost story that’s mentioned in the tourist material I’ve gathered is a white woman whose fiance shot her brother in a duel and then proposed to another woman. So she shut herself up in her great house and now haunts the crumbling remains. THAT is the ghost story we’re supposed to care about? I realize the intent is not to alienate tourists who are primarily white, but I think it’s a mistake to assume that whites don’t want to know the truth about slavery. In fact, the greater risk is getting too deep, too graphic, and turning the past into another kind of exotic artifact. I mean, we have to have a conversation about language—what’s in a name? Why does the word “plantation” trigger positive associations for tourists and negative associations for me? I can already see a panel in my museum that will list “Ways to Be a Better Tourist.” All the grant-writing experience I’ve been accumulating will come in handy because I’ll need a major grant to make this happen. Everything prepares you for what’s next. I’ve been teaching this course on neo-slave narratives, and now I can select the best slavery novels for my museum bookstore. I’m going to enlarge those slave registers and line the walls with them. I’ll find an artist to develop a rendition of the mass suicide that took place in 1736 when 100 slaves jumped from the Prince of Orange slave ship anchored off the coast of Nevis. The history book I’m reading suggests it was a “cruel joke” that prompted an enslaved man to board the ship with his owner and tell the slaves that they were to be eaten once they were taken ashore. Maybe what he really said was, “Life as a slave on this island is unbearable,” and the newly arrived Africans decided death was the better option.

Ok, I better get myself ready to go. Alexander Hamilton House, lunch with Amba, and then all that other stuff. And maybe another nap on the beach…

June 10, 2012

day of rest

If I really was a bird in a previous life, I think I might have been a bananaquit. Yesterday while I was eating breakfast in the open air dining room, a tiny bird flew up to the railing next to my table. Then it flitted to the next table and the next and the next—and each time it tried to use its beak to prod the lid off the sugar jar! A bird after my own heart. I realized today that I haven’t had anything sweet since I arrived—no cake, no cookies. So I broke down and had a candy bar (which required me to walk over to the main office on my stiff, sore legs). I didn’t do much today. Woke at 3am again and finally got up since it was clear I wasn’t going to fall back to sleep. Dozed a bit this afternoon and then put on my bathing suit and lay out in the sun. I keep thinking about my grandmother’s birth certificate—we thought she was born in St. John’s Parish but it turns out she was born in Gingerland (great name, right?). The certificate was signed by Jane Hanley of Crab Hole—could that be Rosetta’s grandmother? My great-grandmother? I also discovered that the most famous writer in Nevis, Amba Trott,

If I really was a bird in a previous life, I think I might have been a bananaquit. Yesterday while I was eating breakfast in the open air dining room, a tiny bird flew up to the railing next to my table. Then it flitted to the next table and the next and the next—and each time it tried to use its beak to prod the lid off the sugar jar! A bird after my own heart. I realized today that I haven’t had anything sweet since I arrived—no cake, no cookies. So I broke down and had a candy bar (which required me to walk over to the main office on my stiff, sore legs). I didn’t do much today. Woke at 3am again and finally got up since it was clear I wasn’t going to fall back to sleep. Dozed a bit this afternoon and then put on my bathing suit and lay out in the sun. I keep thinking about my grandmother’s birth certificate—we thought she was born in St. John’s Parish but it turns out she was born in Gingerland (great name, right?). The certificate was signed by Jane Hanley of Crab Hole—could that be Rosetta’s grandmother? My great-grandmother? I also discovered that the most famous writer in Nevis, Amba Trott,  is an old family friend; I haven’t seen him since I was a child, but his first wife up in Canada put me in touch with him and we’re going to meet tomorrow hopefully. After I visit the Alexander Hamilton House, the police station, the registrar’s office, and the hospital (to see if there are any medical records for Rosetta). Hopefully I can visit my cousin’s school on Tuesday, and on Wednesday I head home…

is an old family friend; I haven’t seen him since I was a child, but his first wife up in Canada put me in touch with him and we’re going to meet tomorrow hopefully. After I visit the Alexander Hamilton House, the police station, the registrar’s office, and the hospital (to see if there are any medical records for Rosetta). Hopefully I can visit my cousin’s school on Tuesday, and on Wednesday I head home…

I bought a new instant camera for this trip, but have hardly taken any photos. And then when I do, I can’t post them online–frustrating. I need to get someone to take some pictures of me over the next couple of days to make sure I’m part of the official record…

June 9, 2012

peaked

Pa’s name is Denny Elliott!!! This has been an unbelievable day. My body is sore and a bit bruised but I feel incredibly blessed. Unfortunately, I woke at 3:30am and couldn’t fall back to sleep—too many ideas percolating! I had breakfast at 7am to make sure I’d be ready for my pick-up at 7:30; the waitress in the dining room marveled at my desire to climb the mountain and said her teenage sister climbed it, then came home, fell into bed, and cried. And now I know why! Just a few words about Nevis Peak: it’s very steep (or, as I like to say, “practically vertical”). Now, I have zero experience climbing mountains and I am not super fit,

Pa’s name is Denny Elliott!!! This has been an unbelievable day. My body is sore and a bit bruised but I feel incredibly blessed. Unfortunately, I woke at 3:30am and couldn’t fall back to sleep—too many ideas percolating! I had breakfast at 7am to make sure I’d be ready for my pick-up at 7:30; the waitress in the dining room marveled at my desire to climb the mountain and said her teenage sister climbed it, then came home, fell into bed, and cried. And now I know why! Just a few words about Nevis Peak: it’s very steep (or, as I like to say, “practically vertical”). Now, I have zero experience climbing mountains and I am not super fit,  but I’m no slouch either! My guide, Evenson, didn’t break a sweat, didn’t use the guide ropes, and wasn’t covered in mud by the time we got back to the bottom. I, on the other hand, was out of breath before we even got onto the mountain and that hike up a modest incline was *nothing* compared to what lay ahead. I realized within about half an hour that I was *not* going to complete the hike—imagine climbing the steepest stairs you’ve ever seen—two or three at a time. Then imagine those steps covered in slippery mud! I was naive, I guess—the peak is covered in rainforest and so as we climbed, the ground became wet and mucky. Sometimes there were ropes that you could use to haul yourself up the rocky mountainside; other times you simply grabbed roots on the ground. Evenson gave me plenty of breaks and pep talks, but we were eventually overtaken by a British couple with TWO KIDS who were loving the adventure. The wife warned me about the challenge of getting back down, and she was right—mud, roots, dripping foliage, slick tree trunks, and a wet rope to help you repel down the mountainside! I was covered in mud, I slid and slammed my hip

but I’m no slouch either! My guide, Evenson, didn’t break a sweat, didn’t use the guide ropes, and wasn’t covered in mud by the time we got back to the bottom. I, on the other hand, was out of breath before we even got onto the mountain and that hike up a modest incline was *nothing* compared to what lay ahead. I realized within about half an hour that I was *not* going to complete the hike—imagine climbing the steepest stairs you’ve ever seen—two or three at a time. Then imagine those steps covered in slippery mud! I was naive, I guess—the peak is covered in rainforest and so as we climbed, the ground became wet and mucky. Sometimes there were ropes that you could use to haul yourself up the rocky mountainside; other times you simply grabbed roots on the ground. Evenson gave me plenty of breaks and pep talks, but we were eventually overtaken by a British couple with TWO KIDS who were loving the adventure. The wife warned me about the challenge of getting back down, and she was right—mud, roots, dripping foliage, slick tree trunks, and a wet rope to help you repel down the mountainside! I was covered in mud, I slid and slammed my hip  into a tree (but Evenson stopped me from falling into the ghut). I have some lovely photos, and am proud that I even made it halfway—and I’m grateful that I didn’t seriously hurt myself! Know your limitations. That’s my motto. I seriously doubt I’ll be able to get out of bed tomorrow but if I can, I’ll be parking myself in that hammock on the beach…

into a tree (but Evenson stopped me from falling into the ghut). I have some lovely photos, and am proud that I even made it halfway—and I’m grateful that I didn’t seriously hurt myself! Know your limitations. That’s my motto. I seriously doubt I’ll be able to get out of bed tomorrow but if I can, I’ll be parking myself in that hammock on the beach…

Peak Heaven is absolutely wonderful—three generations of the Herbert family run the site and it’s the perfect place to learn about Nevisian history and culture. Kathleen picked me up from my hotel and we talked about the importance of developing and supporting native-run initiatives. There’s a piece of land for sale not too far from Peak Heaven, and I would *love* to open an arts center that could collaborate with them on their many community-based projects. I’ve already chosen a name for the center: Black Dog Arts…

run the site and it’s the perfect place to learn about Nevisian history and culture. Kathleen picked me up from my hotel and we talked about the importance of developing and supporting native-run initiatives. There’s a piece of land for sale not too far from Peak Heaven, and I would *love* to open an arts center that could collaborate with them on their many community-based projects. I’ve already chosen a name for the center: Black Dog Arts…

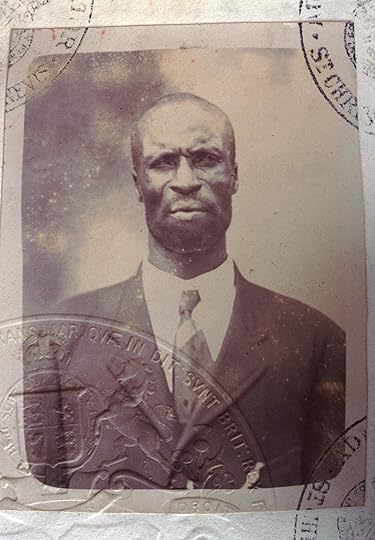

I’ve met so many wonderful people here and today when I showed Mrs. Herbert the photo of my great-grandfather, she suggested that I talk to Rodney Elliott since she would know whether we were in fact related. Kathleen kindly drove me over to Rodney’s lovely cafe in Stoney Grove; I pulled up a stool at the bar, brought up the photo of “Pa” Elliott on my camera, and handed it to her. Rodney looked at the image, looked at me, and asked, “Why do you have a picture of my Pa?” You could have knocked me OFF that stool—it was like an episode of one of those genealogy shows! I quickly pulled out my notebook and started making a family tree. Turns out Rodney is the sister of the head librarian here in Nevis, and their father was my grandmother’s brother! And just as Rodney finished listing her siblings for me, her brother drove by in a black pick-up truck—she hollered to him and he came in to meet me and to inspect the photo of Pa. Both were surprised to learn that an Elliott could be so “clear” (pron. “clair”)  when the Elliotts are known to be dark, but my forehead apparently removed any doubts. Rodney gave us some passion fruit juice to drink and shared some of her family photos; she’s certain I’m related to plenty of people over in Rawlins, so I definitely want to spend more time there. On the way back down the mountain I looked for a souvenir—something that will last longer than my aching muscles. I found a purple seed that opens like a star. Time for me to plant a seed in Nevis, I think.

when the Elliotts are known to be dark, but my forehead apparently removed any doubts. Rodney gave us some passion fruit juice to drink and shared some of her family photos; she’s certain I’m related to plenty of people over in Rawlins, so I definitely want to spend more time there. On the way back down the mountain I looked for a souvenir—something that will last longer than my aching muscles. I found a purple seed that opens like a star. Time for me to plant a seed in Nevis, I think.

Tomorrow will be a day of rest but Monday is going to be busy—my other cousin, Vannie, asked me to visit her school and I can’t *wait* to meet some Nevisian kids! Then I want to visit the registrar’s office and see how many birth certificates they can find for my ancestors. I’m hoping to be able to trace our family to a particular plantation, and my aunt told me yesterday that my great-grandmother lived in Braziers—a village named for a former estate. This afternoon another  cousin in Canada, Carlene, sent me a priceless photograph of my great-grandfather Joseph Hood. I’m being inundated with assistance and I am *so* grateful. Before I left NYC I was feeling anxious and a little upset, and I realized that I was missing my Dad. I missed him when I went to Nevis for the first time in 2003 because he was still alive then and I wanted him to introduce me to his homeland—to keep me from feeling like such an outsider. But my Dad had been diagnosed with cancer by then and a trip simply wasn’t possible (not that he offered to go, and not that I asked); he attended my graduation from NYU and then I went off on my own the very next day. This time around I felt angry, resentful, and hurt—I still don’t fully understand why my father kept so much of his childhood from us. I know the mystery surrounding his mother bothered him; maybe the shame made him want to stay away and stay silent. But he rarely passed down any of his good memories, and I know there were some because he recorded them in his memoir. But then he died, and there are so many questions I can no longer ask him…which is why I’m so grateful that my other relatives are willing to talk to me. Almost every door has opened since I arrived in Nevis. I don’t know how my father would feel about my prospective move (back) to Nevis. He wanted to escape the past, I think, but sankofa means “there is no shame in going back to retrieve something of value you left behind.” And there’s value here…

cousin in Canada, Carlene, sent me a priceless photograph of my great-grandfather Joseph Hood. I’m being inundated with assistance and I am *so* grateful. Before I left NYC I was feeling anxious and a little upset, and I realized that I was missing my Dad. I missed him when I went to Nevis for the first time in 2003 because he was still alive then and I wanted him to introduce me to his homeland—to keep me from feeling like such an outsider. But my Dad had been diagnosed with cancer by then and a trip simply wasn’t possible (not that he offered to go, and not that I asked); he attended my graduation from NYU and then I went off on my own the very next day. This time around I felt angry, resentful, and hurt—I still don’t fully understand why my father kept so much of his childhood from us. I know the mystery surrounding his mother bothered him; maybe the shame made him want to stay away and stay silent. But he rarely passed down any of his good memories, and I know there were some because he recorded them in his memoir. But then he died, and there are so many questions I can no longer ask him…which is why I’m so grateful that my other relatives are willing to talk to me. Almost every door has opened since I arrived in Nevis. I don’t know how my father would feel about my prospective move (back) to Nevis. He wanted to escape the past, I think, but sankofa means “there is no shame in going back to retrieve something of value you left behind.” And there’s value here…

June 8, 2012

day of discovery

I just ate a mango with a spoon. Not pretty, but *so* good and I didn’t have a knife here in my room. I need to figure out how to eat dinner here in Nevis. By the time I get back to the hotel, I desperately need silence and solitude. I don’t want to eat alone in the dining room, I don’t want anyone to keep me company (not that the other guests have made any friendly overtures), and there’s no room service at night. So dinner tonight is a granola bar plus a mango. I also have some tiny plums that my aunt sent me home with—I didn’t have the nerve to ask for a third serving of black-eyed peas and rice to go! My grandparents used to make the best rice and I haven’t had any since my grandmother died in 2005. Yes, I could learn to cook it myself, but that’s not the point. I want to be cooked for.

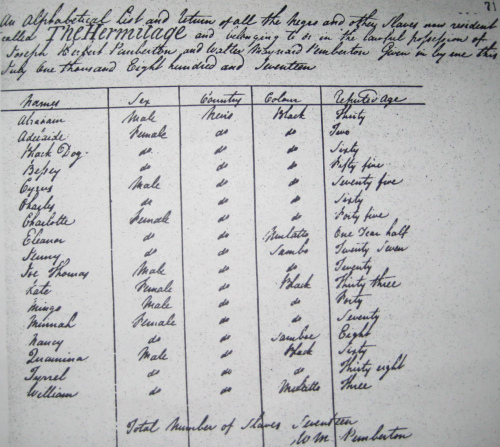

This morning I started a journal and tried to recall all the impressions and observations that I haven’t had the energy to post here on the blog. My days are so full of discovery—I’m not sure when I’ll actually process everything that’s going on. Today I learned that a photograph I’ve had for years is actually of my great-grandfather and not my great-grandmother’s second husband as I’d been told. All I need now is a photograph of my grandmother, and I’m starting to believe that *just* might happen because when I got into the taxi this morning, my driver turned out to be an attorney and former politician who listened to my mission, made a few calls, and then drove me straight to the Nevis administration office and introduced me to another Elliott! She kindly listened to my story about Rosetta, called her aged father to ask for details, and promised to get back to me when he didn’t pick up the phone. Just like that! I was late getting to my 10am appointment at the Nevis Historical and Conservation Society, but was nonetheless warmly received and the curator patiently listened to my many areas of interest and brought me *just* what I was looking for: a booklet about Nevis at the time of Alexander Hamilton’s residence here, slave registers, and a list of the plantations in St. John’s parish (where my family’s from). We had some trouble with the photocopier, but I still came away with this sample roster—look at the name of the third slave on the list:

This morning I started a journal and tried to recall all the impressions and observations that I haven’t had the energy to post here on the blog. My days are so full of discovery—I’m not sure when I’ll actually process everything that’s going on. Today I learned that a photograph I’ve had for years is actually of my great-grandfather and not my great-grandmother’s second husband as I’d been told. All I need now is a photograph of my grandmother, and I’m starting to believe that *just* might happen because when I got into the taxi this morning, my driver turned out to be an attorney and former politician who listened to my mission, made a few calls, and then drove me straight to the Nevis administration office and introduced me to another Elliott! She kindly listened to my story about Rosetta, called her aged father to ask for details, and promised to get back to me when he didn’t pick up the phone. Just like that! I was late getting to my 10am appointment at the Nevis Historical and Conservation Society, but was nonetheless warmly received and the curator patiently listened to my many areas of interest and brought me *just* what I was looking for: a booklet about Nevis at the time of Alexander Hamilton’s residence here, slave registers, and a list of the plantations in St. John’s parish (where my family’s from). We had some trouble with the photocopier, but I still came away with this sample roster—look at the name of the third slave on the list:

Can you read it? A sixty year old enslaved black woman was called “Black Dog.” I’d like to believe I’m reading that wrong, but I don’t think I am. And I’ve never seen the word “Sambo” being used to describe a slave’s color (a Google search provides this clue: “samboe is offspring of a half-caste and a black person”). This particular plantation didn’t have any African slaves, but most had quite a few—and some rosters ended with a list of slaves who “absconded.” So many names for so many people whose stories we’ll never know. Sobering but also inspiring. After the historical society I went to my aunt’s house and devoured the tasty meal she’d prepared for me. The last time I visited her at home, an itinerant donkey left an unwanted deposit on the front step; this time around we heard the dog barking and I looked out the window to see a giant hog rooting around the yard. Yesterday I saw a little white egret hanging out with a herd of goats and three monkeys sneaking onto the grounds of a luxurious hotel…there’s no way I can paint a complete picture of this experience. While I was at Golden Rock Plantation yesterday, I raised my camera to take a photo of the converted windmill and saw a tiny black dot hovering at the edge of the frame. I lowered the camera just in time to see the hummingbird disappear. Today, as I left Mrs. Liburd’s yard, I looked over at a hibiscus plant and saw two tiny black-crested hummingbirds—I had just enough energy left to smile before they raced toward me and flew just inches above my head…

Can you read it? A sixty year old enslaved black woman was called “Black Dog.” I’d like to believe I’m reading that wrong, but I don’t think I am. And I’ve never seen the word “Sambo” being used to describe a slave’s color (a Google search provides this clue: “samboe is offspring of a half-caste and a black person”). This particular plantation didn’t have any African slaves, but most had quite a few—and some rosters ended with a list of slaves who “absconded.” So many names for so many people whose stories we’ll never know. Sobering but also inspiring. After the historical society I went to my aunt’s house and devoured the tasty meal she’d prepared for me. The last time I visited her at home, an itinerant donkey left an unwanted deposit on the front step; this time around we heard the dog barking and I looked out the window to see a giant hog rooting around the yard. Yesterday I saw a little white egret hanging out with a herd of goats and three monkeys sneaking onto the grounds of a luxurious hotel…there’s no way I can paint a complete picture of this experience. While I was at Golden Rock Plantation yesterday, I raised my camera to take a photo of the converted windmill and saw a tiny black dot hovering at the edge of the frame. I lowered the camera just in time to see the hummingbird disappear. Today, as I left Mrs. Liburd’s yard, I looked over at a hibiscus plant and saw two tiny black-crested hummingbirds—I had just enough energy left to smile before they raced toward me and flew just inches above my head…

So much more to share but I think I’d better save it for the journal. I managed to sleep until past 5am this morning, so will hope for another hour tonight. Tomorrow my mountain-climbing adventure begins at 7:30am. My great-grandfather, “Pa” Elliott, was from Rawlins and where do you think I’ll be heading tomorrow? Rawlins…I’m taking his photo with me in case anyone recognizes him. If nothing else, I’d like to know his name…

June 7, 2012

the human stain

Had a full day today, starting with my 10am tour of the island and ending with my ingenious use of thermal energy (hot water in an ice bucket) to heat up my leftovers from last night. By midafternoon I was ready to crash—not in a hammock on the beach, but in my little bungalow with the a/c on HIGH. Actually I’m trying to be energy conscious, especially after I learned the high cost of electricity here in Nevis. Edith, my tour guide, shared that sometimes the monthly bill is as high as $400 EC (about $150 US). Which means that a/c is a luxury for most—you open the windows wide and let the strong breeze blow through. But that also means letting the mosquitoes in…I’ve already got a few bites and my bungalow’s screened in. Nevis is addressing the energy issue by adding wind turbines along the windward (Atlantic Ocean) side of the island and they’re also exploring geothermal energy since there are natural hot springs here. Each bungalow at this

Had a full day today, starting with my 10am tour of the island and ending with my ingenious use of thermal energy (hot water in an ice bucket) to heat up my leftovers from last night. By midafternoon I was ready to crash—not in a hammock on the beach, but in my little bungalow with the a/c on HIGH. Actually I’m trying to be energy conscious, especially after I learned the high cost of electricity here in Nevis. Edith, my tour guide, shared that sometimes the monthly bill is as high as $400 EC (about $150 US). Which means that a/c is a luxury for most—you open the windows wide and let the strong breeze blow through. But that also means letting the mosquitoes in…I’ve already got a few bites and my bungalow’s screened in. Nevis is addressing the energy issue by adding wind turbines along the windward (Atlantic Ocean) side of the island and they’re also exploring geothermal energy since there are natural hot springs here. Each bungalow at this  hotel has a solar panel at the back, which is brilliant. I didn’t see solar panels at the other hotels on my tour, and we stopped at a few. The luxury hotels are often converted plantations, which reminded me of Louisiana. It’s unsettling to see white people lounging by the pool when enslaved Africans were worked to death on that spot—would you vacation or get married at Auschwitz? Still, there I was snapping photos (which are posted on Facebook) and complimenting the Rastafarian men who maintain the stunning gardens at Golden Rock Plantation Inn (left). “Have you seen any ghosts?” I asked one of them. And without missing a beat he started telling me about ghosts he’s seen around the island and the particular ghost of a murdered slave that is sometimes heard climbing the steps at the hotel. Then my tour guide joined in and opined that another unsuccessful hotel had likely closed due to a haunting. Nevisian artist Terry Boddie writes about “the residue of memory” and there are plenty of stains or

hotel has a solar panel at the back, which is brilliant. I didn’t see solar panels at the other hotels on my tour, and we stopped at a few. The luxury hotels are often converted plantations, which reminded me of Louisiana. It’s unsettling to see white people lounging by the pool when enslaved Africans were worked to death on that spot—would you vacation or get married at Auschwitz? Still, there I was snapping photos (which are posted on Facebook) and complimenting the Rastafarian men who maintain the stunning gardens at Golden Rock Plantation Inn (left). “Have you seen any ghosts?” I asked one of them. And without missing a beat he started telling me about ghosts he’s seen around the island and the particular ghost of a murdered slave that is sometimes heard climbing the steps at the hotel. Then my tour guide joined in and opined that another unsuccessful hotel had likely closed due to a haunting. Nevisian artist Terry Boddie writes about “the residue of memory” and there are plenty of stains or  scars on the landscape. We stopped at several sites along the Heritage Trail: Cottle Church (right), St. James Church, New River sugar factory, the silk cotton tree where Lord Nelson married his Nevisian bride on the Montpelier Estate (apparently slaves stole the ox that was to be roasted for the wedding feast!). We passed through several villages and saw wooden shacks overgrown with weeds and vines alongside impressive terraced homes and sprawling mansions. I saw the village where my father was born (Brown Hill) and then slipped back into the present moment to meet my aunt for lunch in Charlestown. I dropped off a bag of books for the Nevis Public Library and got to meet their wonderful librarians. And

scars on the landscape. We stopped at several sites along the Heritage Trail: Cottle Church (right), St. James Church, New River sugar factory, the silk cotton tree where Lord Nelson married his Nevisian bride on the Montpelier Estate (apparently slaves stole the ox that was to be roasted for the wedding feast!). We passed through several villages and saw wooden shacks overgrown with weeds and vines alongside impressive terraced homes and sprawling mansions. I saw the village where my father was born (Brown Hill) and then slipped back into the present moment to meet my aunt for lunch in Charlestown. I dropped off a bag of books for the Nevis Public Library and got to meet their wonderful librarians. And  I survived the break-neck speed of a bus (van) that brought me back to the hotel. There’s more to write but I think I’d better turn in—I was up half the night and need to start sleeping more soundly if I’m going to rise at dawn on Saturday for the four-hour trek to the top of Nevis Peak…

I survived the break-neck speed of a bus (van) that brought me back to the hotel. There’s more to write but I think I’d better turn in—I was up half the night and need to start sleeping more soundly if I’m going to rise at dawn on Saturday for the four-hour trek to the top of Nevis Peak…