Zetta Elliott's Blog, page 73

July 16, 2012

teach the truth

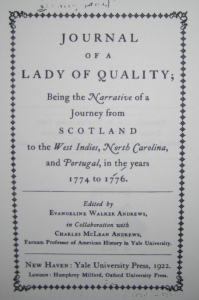

I’m thinking about the best way to develop a curriculum on slavery for school-age children. I think you have to start with the larger ethical issues—what is just, and right, and moral. And you have to cite source documents so that children know how history is written. I’m reading the Journal of a Lady of Quality, and found it quite riveting as Miss Schaw departs from Scotland and crosses the stormy seas to reach Antigua. One black man was forcibly brought on board in Scotland, though he hasn’t been mentioned since, and one of her brother’s servants is described as an “Indian,” but I can’t tell whether she means he’s from India or that he is Native American. It’s 1774—either is possible. Now that Miss Schaw has reached the Caribbean I’m finding it harder to read her journal—there are endless descriptions of the food that’s served, and the wonderful company they keep, and the delicious drinks they sip while strolling along shaded paths. Hardly any mention of the enslaved Africans who make their plantation life so lovely…except for this:

I’m thinking about the best way to develop a curriculum on slavery for school-age children. I think you have to start with the larger ethical issues—what is just, and right, and moral. And you have to cite source documents so that children know how history is written. I’m reading the Journal of a Lady of Quality, and found it quite riveting as Miss Schaw departs from Scotland and crosses the stormy seas to reach Antigua. One black man was forcibly brought on board in Scotland, though he hasn’t been mentioned since, and one of her brother’s servants is described as an “Indian,” but I can’t tell whether she means he’s from India or that he is Native American. It’s 1774—either is possible. Now that Miss Schaw has reached the Caribbean I’m finding it harder to read her journal—there are endless descriptions of the food that’s served, and the wonderful company they keep, and the delicious drinks they sip while strolling along shaded paths. Hardly any mention of the enslaved Africans who make their plantation life so lovely…except for this:

We proceeded to our lodgings thro’ a narrow lane; as the Gentlemen told us no Ladies ever walk in this Country. Just as we got into the lane, a number of pigs run out at a door, and after them a parcel of monkeys. This not a little surprized me, but I found what I took for monkeys were negro children, naked as they were born. We now arrived at our lodgings, and were received by a well behaved woman, who welcomed us, not as the Mrs of a Hotel, but as the hospitable woman of fashion would the guests she was happy to see.

Watching this BBC documentary on racism and the slave trade helped balance things out a bit. I’m only reading this journal because the author apparently makes some keen observations about slavery in St. Kitts/Nevis. Not sure how many more pages I can stand…

July 14, 2012

reboot

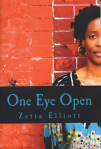

I need to reboot my brain. On Thursday morning I submitted my chapter on magic in NYC parks—it still needs work, but it was time to let go so that I could turn my attention to the five other projects I hope to complete this summer. On Thursday afternoon I ordered a final proof of One Eye Open and started the e-book conversion process. I’ve had “coming soon!” on the Rosetta Press blog for over a year now, and I think it’s finally time to let the book live, warts and all. That night I started working on my slideshow for The Hummingbird’s Tongue; I’ve been invited to attend the inaugural Nevis Book Fair on July 27, and this time I’ll be presenting before children and adults. The director of library services kindly helped me find a guesthouse in town, so I’ll be spending another week in Nevis at the end of the month. That got the wheels turning—I’m supposed to be working on The Deep (Nyla’s story), but instead I’ve been designing a logo and blog for Black Dog Arts. Ultimately I hope to open an arts center in Nevis, but for now I think maybe I’ll start a nonprofit and try to collaborate with existing institutions on the island. Yesterday I heard from the SKN Culture office and my request to participate in the UNESCO Slave Route Project has been forwarded to the minister of education. Maybe I can meet some administrators while I’m in Nevis later this month. Once I get my letter of good conduct from the NYPD next week, my citizenship application will be complete—another thing I can do while I’m there. And since my friend Rosa will be in Antigua at the same time, I may be able to fly over from Nevis and inquire about my grandmother’s alleged institutionalization there. More digging…

I need to reboot my brain. On Thursday morning I submitted my chapter on magic in NYC parks—it still needs work, but it was time to let go so that I could turn my attention to the five other projects I hope to complete this summer. On Thursday afternoon I ordered a final proof of One Eye Open and started the e-book conversion process. I’ve had “coming soon!” on the Rosetta Press blog for over a year now, and I think it’s finally time to let the book live, warts and all. That night I started working on my slideshow for The Hummingbird’s Tongue; I’ve been invited to attend the inaugural Nevis Book Fair on July 27, and this time I’ll be presenting before children and adults. The director of library services kindly helped me find a guesthouse in town, so I’ll be spending another week in Nevis at the end of the month. That got the wheels turning—I’m supposed to be working on The Deep (Nyla’s story), but instead I’ve been designing a logo and blog for Black Dog Arts. Ultimately I hope to open an arts center in Nevis, but for now I think maybe I’ll start a nonprofit and try to collaborate with existing institutions on the island. Yesterday I heard from the SKN Culture office and my request to participate in the UNESCO Slave Route Project has been forwarded to the minister of education. Maybe I can meet some administrators while I’m in Nevis later this month. Once I get my letter of good conduct from the NYPD next week, my citizenship application will be complete—another thing I can do while I’m there. And since my friend Rosa will be in Antigua at the same time, I may be able to fly over from Nevis and inquire about my grandmother’s alleged institutionalization there. More digging…

Now I think I’m ready to turn my attention back to The Deep. Though I just started reading Leonard Pitts Jr.’s Freeman, so maybe it makes more sense to work on Judah’s Tale. The summer ends in six weeks! I was fussing and fuming about that fact yesterday, but it makes more sense to just get busy and make the most of the time that’s left. And accept that everything I hoped to accomplish this summer may get done later rather than sooner.

July 10, 2012

Black Dog Arts

July 8, 2012

less mess

Pushing back against a migraine this morning. I’m still working on this essay, which I said I would submit on Friday. I hate missing my own deadlines but know this paper needs a couple more days to cohere. I finally figured out which voice to use. That sounds odd, but I can’t write anything remotely academic until I establish who I am and where I stand in relation to these texts in this particular moment. Somewhere in the footnotes I’m going to have to admit that contributing to this anthology is preventing me from finishing my latest novel—which pisses me off. But it’s my own fault for saying yes when I should have said no. The paper is a bit like “Hot Mess” in that I’m writing about incongruity, incompatibility, and nonbelonging…which sets the stage for magic.

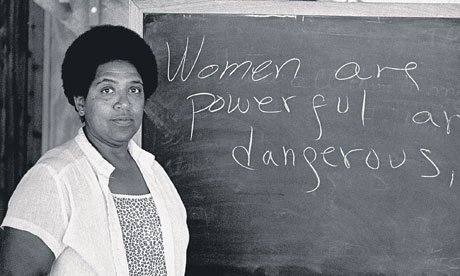

Did anyone see the Audre Lorde film that was screened at Weeksville last night? They posted this photo on their Facebook page and I just had to post it here:

July 3, 2012

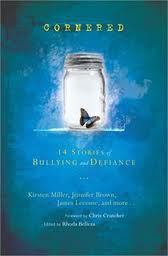

Cornered

Today’s the official release date of a new anthology to which I contributed: Cornered: 14 Stories of Bullying & Defiance. Here’s a description from the publisher:

Today’s the official release date of a new anthology to which I contributed: Cornered: 14 Stories of Bullying & Defiance. Here’s a description from the publisher:

Guy, girl, straight, gay, outsider, insider, nerd, beauty, jock, or brain—none of these labels matter when it

comes to feeling harassed, intimidated, or less than one’s true self. Bullying has no bounds, and the

manifestation of if it occurs not only in person, but via text, phone, and online, as well as at school, in the

home, and on the street. This YA fiction anthology includes stories from some of today’s hottest teen authors

and addresses this extremely important issue that affects almost every teen in some way, shape, or form.

Contributors include Kirsten Miller (New York Times bestseller The Eternal Ones), Jennifer Brown (Hate List),

James Lecesne (Absolute Brightness, founder of The Trevor Project), and Lish McBride (Morris Award finalist

Hold Me Closer, Necromancer). No other recent fiction anthology on the market addresses bullying with this

caliber of authors. • Rhoda Belleza is a freelance writer and editor who has worked with Paper Lantern Lit.

If you work with teens I hope you’ll share this important collection with them—and be ready for the conversation that’s sure to follow.

July 1, 2012

just the thing

I never have to wonder why I write what I write…here’s a recent review posted by a teacher on Amazon:

I never have to wonder why I write what I write…here’s a recent review posted by a teacher on Amazon:

1.0 out of 5 stars Just the Thing to Stir Up Racial Tension

June 30, 2012

By Biblically Informed Reader

This review is from: A Wish After Midnight (Paperback)I won this book as part of a prize in a drawing for teachers. Frankly, I am appalled. I would never use it with my students. It’s nothing but poorly written, mind-in-the-gutter, depressing trash destined to incite racial tensions, rather than to encourage unifying discussion. Surely there is something better than this to offer the youth of our nation.

I read seven more Ruth Chew novels yesterday and continue to find striking similarities between her books and mine—except I’m sure the above teacher would *love* Chew’s sanitized version of historical events…

June 27, 2012

black nature

I woke up this morning with my introduction written out in my mind. It shouldn’t have taken me this long to turn to black feminist writer June Jordan, and thinking about my favorite poem of hers reminded me of the James Baldwin quote I used for the title of my dissertation: “the terror of trees and streets.”

I woke up this morning with my introduction written out in my mind. It shouldn’t have taken me this long to turn to black feminist writer June Jordan, and thinking about my favorite poem of hers reminded me of the James Baldwin quote I used for the title of my dissertation: “the terror of trees and streets.”

“Poem about My Rights“

Even tonight and I need to take a walk and clear

my head about this poem about why I can’t

go out without changing my clothes my shoes

my body posture my gender identity my age

my status as a woman alone in the evening/

alone on the streets/alone not being the point/

the point being that I can’t do what I want

to do with my own body because I am the wrong

sex the wrong age the wrong skin and

suppose it was not here in the city but down on the beach/

or far into the woods and I wanted to go

there by myself thinking about God/or thinking

about children or thinking about the world/all of it

disclosed by the stars and the silence:

I could not go and I could not think and I could not

stay there

alone

as I need to be

alone because I can’t do what I want to do with my own

body and

who in the hell set things uplike this

Which bodies belong in which spaces? Our age, race, gender, and sexual orientation too often determine where we’re able to find sanctuary. I’ve read almost half of Ruth Chew’s books and won’t have any trouble comparing hers to mine, but need to begin with a consideration of the way African Americans relate to nature. In Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry, editor/poet Camille Dungy reflects on the trauma of enslavement (and lynching) and its impact on the way blacks engage with the natural world:

African Americans are tied up in the toil and soil involved in working this land into the country we know today. Viewed once as chattel, part of a farm’s livestock or an asset in a banker’s ledger, African Americans developed a complex relationship to land, animals, and vegetation in American culture. (xxii)

Given the active history of betrayal and danger in the outdoors, it is no wonder that many African Americans link their fears directly to the land that witnessed or abetted centuries of subjugation. (xxvi)

Even during the most difficult periods of African American history, the natural world held potential to be a source of refuge, sustenance, and uncompromised beauty. (xxv)

I’ve got a few more articles to read on the development and design of urban parks, and the memorialization of the dead…writing an essay is like putting the pieces of a puzzle together. Not exactly fun, but challenging and—if it coheres—satisfying. Scheduling a midday break at the museum…

June 25, 2012

more art, please

One of my sort-of resolutions for this year was to see more art. It’s very easy when you live in NYC to take access to art for granted—you hear about an exhibit and make a mental note to see it, and then another exhibit opens, and another, and another. I live near the Brooklyn Museum and yet only caught the “Question Bridge” exhibit because it was extended for a few weeks *and* my cousin came to visit. Out of town guests are often the push I need to explore the city I call home. And now that I’ve started seeing some art, I’ve got art on the brain, which makes it hard to concentrate on this essay. Last week my cousin came with me to PS 399, a school in Brooklyn that was celebrating the achievements of its bookmaking club. The students participated in the Ezra Jack Keats bookmaking competition and had a chance to share their beautiful creations with family and friends. I gave a presentation and read from Ship of Souls, and a spoken word artist performed before handing the mic to students who also shared their poetry. It was a great event, and I left feeling hopeful. Imagine what the art scene will look like in ten or twenty years when these kids of color become young adults! On Saturday I went to MoCADA and saw an incredible student exhibit, “Afrofuturism: Imagining Tomorrow.” The museum sent teaching artists into several local schools and helped kids (K-12) develop art projects that express an African sensibility toward technology and the future. One class visited the African Burial Ground and photographed themselves (wearing futuristic clothing) next to adinkra symbols…if you’re in NYC, make a point of going to see this show. It made me want to take an art class! But instead I came home and searched for this video of Hassan Khan‘s film Jewel. I saw it earlier this year at the New Museum with a friend from out of town…the only downside of feeding the need for more art is that it makes me dreamy and then it’s hard to get my own work done. I’m reading Ruth Chew‘s books about witches in Brooklyn but every so often I stop to play this clip and on Wednesday we’re going to see Beasts of the Southern Wild…will try to get some work done in between. Taking the train uptown is a good way to get some reading done and the Studio Museum of Harlem has a new exhibit on Caribbean art…

One of my sort-of resolutions for this year was to see more art. It’s very easy when you live in NYC to take access to art for granted—you hear about an exhibit and make a mental note to see it, and then another exhibit opens, and another, and another. I live near the Brooklyn Museum and yet only caught the “Question Bridge” exhibit because it was extended for a few weeks *and* my cousin came to visit. Out of town guests are often the push I need to explore the city I call home. And now that I’ve started seeing some art, I’ve got art on the brain, which makes it hard to concentrate on this essay. Last week my cousin came with me to PS 399, a school in Brooklyn that was celebrating the achievements of its bookmaking club. The students participated in the Ezra Jack Keats bookmaking competition and had a chance to share their beautiful creations with family and friends. I gave a presentation and read from Ship of Souls, and a spoken word artist performed before handing the mic to students who also shared their poetry. It was a great event, and I left feeling hopeful. Imagine what the art scene will look like in ten or twenty years when these kids of color become young adults! On Saturday I went to MoCADA and saw an incredible student exhibit, “Afrofuturism: Imagining Tomorrow.” The museum sent teaching artists into several local schools and helped kids (K-12) develop art projects that express an African sensibility toward technology and the future. One class visited the African Burial Ground and photographed themselves (wearing futuristic clothing) next to adinkra symbols…if you’re in NYC, make a point of going to see this show. It made me want to take an art class! But instead I came home and searched for this video of Hassan Khan‘s film Jewel. I saw it earlier this year at the New Museum with a friend from out of town…the only downside of feeding the need for more art is that it makes me dreamy and then it’s hard to get my own work done. I’m reading Ruth Chew‘s books about witches in Brooklyn but every so often I stop to play this clip and on Wednesday we’re going to see Beasts of the Southern Wild…will try to get some work done in between. Taking the train uptown is a good way to get some reading done and the Studio Museum of Harlem has a new exhibit on Caribbean art…

June 23, 2012

book love

On Thursday I ordered my new bookcase from Gothic Cabinet and then went to the new visitor center at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden with my cousin and purchased this little pin…we then went next door to the Brooklyn Museum and saw the Question Bridge exhibit—I will definitely be going back to watch more of this expertly integrated video installation (you can watch excerpts on the website *and* there’s an educator guide). Black men ask and answer questions of themselves and one another, and though their answers are interesting, it’s almost more fascinating to simply watch them processing and articulating their values and beliefs…and they’re beautiful! I joked with my cousin that they need to put names and numbers in captions, but really it’s quite moving just to hear so many thoughtful black men reflecting on issues that matter. I

On Thursday I ordered my new bookcase from Gothic Cabinet and then went to the new visitor center at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden with my cousin and purchased this little pin…we then went next door to the Brooklyn Museum and saw the Question Bridge exhibit—I will definitely be going back to watch more of this expertly integrated video installation (you can watch excerpts on the website *and* there’s an educator guide). Black men ask and answer questions of themselves and one another, and though their answers are interesting, it’s almost more fascinating to simply watch them processing and articulating their values and beliefs…and they’re beautiful! I joked with my cousin that they need to put names and numbers in captions, but really it’s quite moving just to hear so many thoughtful black men reflecting on issues that matter. I  wish I heard those voices more often…it’s somewhat sad that it takes technology and a degree of manipulation to create/simulate this kind of dialogue among men. Still, it’s very creative…I’ll be teaching two sections of The Black Male this fall, and will definitely use this in the classroom.

wish I heard those voices more often…it’s somewhat sad that it takes technology and a degree of manipulation to create/simulate this kind of dialogue among men. Still, it’s very creative…I’ll be teaching two sections of The Black Male this fall, and will definitely use this in the classroom.

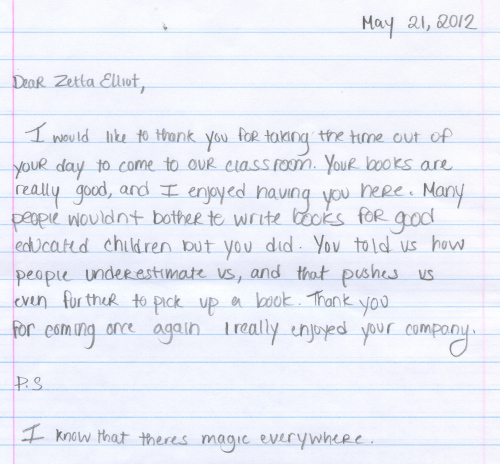

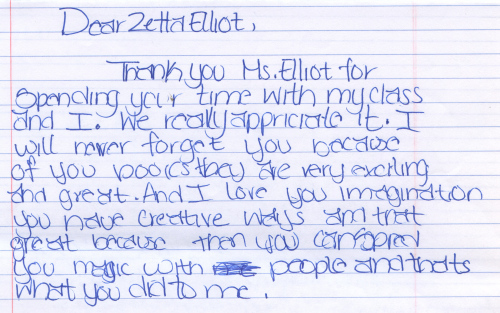

On Friday morning I went up to East Harlem to join the party—my Behind the Book students at JHS 13 were celebrating the publication of their full-color short story anthology, Remembering Our Loved Ones. These are stories they wrote after completing my “Postcards from Far Away” workshop. It was really gratifying to listen as each student went to the front of the classroom and read part or all of her/his story, which was a tribute to someone s/he loved and lost. At the end I asked the students to autograph my copy of their book…I felt really lucky to be able to share that moment with them. Chris from Behind the Book then gave me a packet of letters written by a group of 6th graders I’d worked with at Thurgood Marshall Academy. Their teacher already sent me a moving email, but there’s nothing like hearing from the kids themselves:

June 19, 2012

creative extremist

Just—say—no! Easier said than done, right? After I finish this essay I am taking a break from academic writing. I had my end of year evaluation at work this afternoon and my director actually told me to slow down…great advice! I want to finish two novels this summer, but that’s probably not realistic. As she said, there’s no point pushing yourself so hard that you’re burnt out by the time the fall semester begins. So if you’re thinking of asking me to contribute to some fantastic project, think again. Please. Help me help myself…

Yesterday I had my film date with CUNY TV—I’m going to be featured on their show, Study With the Best, and so we spent more than three hours at the African Burial Ground yesterday (three hours of footage they’ll have to edit down to *five* minutes!). I pulled on my top as I dressed that morning and swore I could still smell the sea—even though I hand-washed that shirt the night before. I came home from the film shoot and mailed more books back to Nevis. I’ve got my 1871 map of the island on the wall above my desk, and my growing library of books on Nevis will require me to buy a new bookcase this week—despite what I said at ChLA about books being designed to circulate and not to reside in the home…

Yesterday I had my film date with CUNY TV—I’m going to be featured on their show, Study With the Best, and so we spent more than three hours at the African Burial Ground yesterday (three hours of footage they’ll have to edit down to *five* minutes!). I pulled on my top as I dressed that morning and swore I could still smell the sea—even though I hand-washed that shirt the night before. I came home from the film shoot and mailed more books back to Nevis. I’ve got my 1871 map of the island on the wall above my desk, and my growing library of books on Nevis will require me to buy a new bookcase this week—despite what I said at ChLA about books being designed to circulate and not to reside in the home…

I’m doing research for this paper on NYC parks and it’s reminding me of graduate school when I did one of my exams in the field of urban studies. I’m trying to build momentum but Dr. King’s words are still ringing in my ears. If you haven’t read his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” lately, do take another look. I had lunch with a friend today and we marveled at those PoC authors and editors who jump up and insist that publishing is a level playing field—how else to explain their individual success? Dr. King shared these pearls of wisdom 50 years ago:

You speak of our activity in Birmingham as extreme. At first I was rather disappointed that fellow clergymen would see my nonviolent efforts as those of an extremist. I began thinking about the fact that I stand in the middle of two opposing forces in the Negro community. One is a force of complacency, made up in part of Negroes who, as a result of long years of oppression, are so drained of self respect and a sense of “somebodiness” that they have adjusted to segregation; and in part of a few middle-class Negroes who, because of a degree of academic and economic security and because in some ways they profit by segregation, have become insensitive to the problems of the masses. The other force is one of bitterness and hatred, and it comes perilously close to advocating violence…So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice?…Perhaps the South, the nation and the world are in dire need of creative extremists. (my emphasis)