Marilyn Oser's Blog, page 8

August 21, 2013

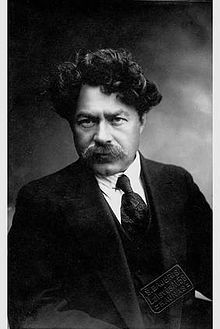

10 Things You Need to Know About… Ben Avigdor

Literary entrepreneur

1. Ben Avigdor is the pen name for Abraham Leib Shalkovich, born near Vilna in 1867. He grew up near Grodno and was educated in Bible and Talmud with the expectation that he’d become a rabbi. Evidently, it didn’t take.

2. In 1889, he moved to Vilna, where he wrote a group of essays on Zionism and his first short story. He joined Bene Mosheh, a Zionist movement and in 1891 was appointed secretary of its Warsaw office. Note that his choice of pen name relates to Bene Mosheh (sons/children of Moses), since “Avigdor” in Talmudic usage refers to Moses.

3. In Warsaw, he began publishing a “library” series in Hebrew - short stories under the name Sifre Agurah (Penny Books) – bringing out 31 numbers in all. His success with these Penny Books prompted a reconsideration among the younger Jewish literati about the titles and distribution of Hebrew texts.

4. Under his leadership, the New Movement was formed by young writers who were rebelling against established themes and writing styles. Every two weeks in the years 1891-93, they put out a 32-page, tightly printed pamphlet that included fiction and nonfiction exploring a variety of issues.

5. Ben Avigdor contributed six novels and novelettes to this effort. Frischmann [see my blog post of February 27] wrote for them, as did Peretz.

5. Ben Avigdor contributed six novels and novelettes to this effort. Frischmann [see my blog post of February 27] wrote for them, as did Peretz.

6. His next publishing venture was Ahi’asaf, the first publicly funded Jewish printing press. Ben Avigdor was one of the founders of this Hebrew literary venture and its managing editor for three years.

7. In 1895, he sold his shares in Ahi’asaf and founded Tushiyah (Sound Knowledge), a publishing company devoted to the development of modern Hebrew culture. It was the first privately owned, modern secular Jewish printing press, and he served as its editor, producing both literary and scientific works.

8. He also published in the “mother tongue”: Yiddish newspapers; the first edition of Sholem Aleichem’s collected works; and, in the wake of the Kishinev pogrom, a collection edited by Sholem Aleichem to benefit the victims.

9. In 1921 in Carlsbad, having expanded his company’s activities to Palestine and the United States, Abraham Shalkovich, AKA Ben Avigdor, died suddenly at the age of 55.

10. He is not to be confused with Avraham ben Avigdor of Prague, who was longtime chief rabbi and head of Prague’s yeshiva, and who is listed in the Alteneuschul‘s memorial book. In 1541, when Jews were expelled from Prague, he was one of fifteen who were permitted to stay. In response, he wrote an elegy, “Ana Elohe Avraham,” that became part of the prayers said on Yom Kippur. Author of commentary and legal decisions, Avraham ben Avigdor died in 1542.

You’ll find Ben Avigdor Street in Tel Aviv just west of Ayalon South and (appropriately) parallel to Tushiya. Ben Avigdor is today a street lined with clubs and dance bars.

August 14, 2013

10 Things You Need to Know About… Nahum Sirkin

Founder of Labor Zionism

1. Nahum Sirkin (or Nachman Syrkin) was born in Mogilev, Russia – now Belarus – in February, 1868. Early on, he was educated by Jewish private tutors; but when his family moved to Minsk in 1884, he attended a Russian high school.

2. He had a philosophical bent and became interested in both Hovevei Zion (a movement to settle Palestine) and socialism. Moving in Russian revolutionary circles, he sought to meld the two, an effort in which he was joined by Ber Berochov [see my blog post of April 10]. He led the Socialist Zionist faction – admittedly, a group with few members – at the First Zionist Congress in 1897.

3. In 1888, after a 3-week imprisonment for his activities, he left Russia and settled in Berlin to pursue his studies in psychology and philosophy. There, he was a founder of the Russian-Jewish Scientific Society; among its members were a number of future Zionist leaders, including Chaim Weizmann. He founded short-lived Yiddish and Hebrew journals and wrote Socialist-Zionist pamphlets which were smuggled into tsarist Russia.

4. “The Jewish Question and the Socialist Jewish State” – originally written in German (1898) – described his concept of Zionism based on cooperative settlement by the Jewish proletariat. In fact, he was the first to propose that immigrants in Palestine form collective settlements. At the Second Zionist Congress, he submitted a resolution for the formation of a Jewish national fund to support settlement.

5. At the congresses, he was known for his provocative speeches, in which he attacked establishment views; he fought with just about everyone about their ideas of Zionism, and his frequent outbursts gave rise to loud protests. He went to the Seventh Zionist Congress in Basel in 1905 as a delegate of the new Zionist Socialist Workers Party.

6. In 1905, no longer welcome in Berlin, he returned to Russia. Then, in 1907, he moved to the United States and became one of the leaders of Poale Zion (the socialist Jewish labor party) in America. He would lead this party until his death.

7. During World War I, Sirkin supported the idea of a Jewish legion to fight with the Allies for the liberation of Palestine from the Ottoman Empire. In 1919, following the war, he served as a member of the American Jewish delegation to the Versailles Peace Conference.

8. In the same year, 1919, the world Poale Zion conference was held it Stockholm. He was given the assignment of visiting Eretz Yisrael as head of a study commission that would develop a plan for kibbutz settlement. He toured the land with other members of the commission and was principal author of the plan, which was later adopted in concept by the Zionist labor movement.

9. Sirkin intended to make aliyah, but he died of a heart attack in New York City in September 1924. His remains were re-interred in Kibbutz Kinneret, along with other founders of labor Zionism, in 1951.

10. What sort of thinker was Sirkin? Unlike many socialists and communists, he was deeply religious, despite his contempt for what he considered the “petrified” form of rabbinic Judaism in the diaspora. He was not a Marxist; he considered socialism a moral concept, perhaps coming out of Biblical concepts of social justice. He supported making Hebrew the national language. He suported Herzl’s Uganda Plan. Herzl called him “that exaltado.”

“A classless society and national sovereignty are the only means of completely solving the Jewish problem.”

“A classless society and national sovereignty are the only means of completely solving the Jewish problem.”

You’ll find Sirkin Street in Tel Aviv off Bograshov, between Ben Yehudah and Sholem Aleichem; and in Haifa south of the City Hall. Kfar Sirkin, founded 1933, is located close to Petach Tikvah.

August 7, 2013

12 Things You Need to Know About… Henrietta Szold

Hadassah’s Founder, and – Wow! – so much more.

1. Henrietta Szold was born in Baltimore in December 1860, the daughter of a rabbi, the eldest of eight girls. Among her earliest memories was being perched on her father’s shoulders to catch sight of the funeral cortege of Abraham Lincoln. After graduating at the top of her class from high school in 1877, she taught in both secular and religious schools while attending public lectures at Johns Hopkins.

2. It was she who established the first American night school offering English language instruction and vocational skills to Russian-Jewish and other immigrants in Baltimore. It wasn’t long before 5000 people had attended, and the school became a national model.

2. It was she who established the first American night school offering English language instruction and vocational skills to Russian-Jewish and other immigrants in Baltimore. It wasn’t long before 5000 people had attended, and the school became a national model.

3. She began work for the nascent Jewish Publication Society in 1888, an association she maintained for over twenty years. She was the first female editor, one of the nine members of the publications committee and its first executive secretary (1893). Among the many important works that she translated, edited, indexed: translated Simon Dubnow‘s Jewish History, and Nahum Slovschz’s The Renascence of Hebrew Literature; edited the translation of Heinrich Graetz’s History of the Jews (see my blog post of July 17); translated, edited and indexed much of Legends of the Jews, compiled by Louis Ginzberg; and was involved in producing the American Jewish Yearbook from 1898 to 1909.

4. As to her Zionism, in 1896, a month before the publication of Herzl’s Der Judenstaat (see my post of June 26), Szold gave a speech in which she outlined her ideas, including the ingathering of Jews and revival of Jewish culture. In 1898 she was elected to the executive committee of the Federation of American Zionists – its only female member. Later, during World War I, she was the only woman on the Provisional Executive Committee for General Zionist Affairs, headed by Louis Brandeis.

5. She began advanced Jewish studies at the Jewish Theological Seminary in 1902. A rabbinic school, it was for men only, and she was able to pursue her studies only because she managed to obtain permission from Solomon Schechter, its president, in exchange for her promise that she would never seek ordination.

6. In 1909 she visited Palestine for the first time. The trip reinforced her commitment to Zionism and focused her attention on the health, education and welfare of the Yishuv, the Jews of Palestine. In 1910 she became secretary of the board of the Agricultural Experiment Station established by Aaron Aaronsohn (who happens to be one of my characters in Rivka’s War).

7. 1912: Szold, along with a small group of friends, founded Hadassah. She was to serve as its president until 1926, recruiting American women to upgrade health care in Palestine. Her first project was to start a visiting nurse program in Jerusalem.

8. In 1913, the first Hadassah mission sent two nurses to Palestine to provide pasteurized milk and to eradicate the eye disease trachoma. By 1918, Hadassah sent an entire medical unit of 45 doctors, nurses and sanitary workers. Hadassah was to fund hospitals, a medical school, dental facilities, x-ray clinics, infant welfare stations, and soup kitchens for Jews and Arabs alike.

9. In 1933, Szold made aliyah to Palestine, where she helped run Youth Aliyah, an organization that rescued tens of thousands of Jewish children from Nazi Europe and brought them to settlements in Palestine.

10. During the 1920s and 30s, she had supported Brit Shalom, an organization committed to finding a binational solution to the issue of Jews and Arabs in Palestine. In 1942, she co-founded (with Judah Magnes, Martin Buber, and Ernst Simon) the Ihud political party, dedicated to Arab-Jewish reconciliation and a binational state.

11. Though Szold was religiously traditional, she advocated for a larger role for women in Judaism. Her words are quoted in a responsum adopted by the Law Committee of Conservative Judaism, permitting women to recite the mourner’s Kaddish: “The Kaddish means to me that the survivor publicly and markedly manifests his wish and intention to assume the relation to the Jewish community which his parent had, and that so the chain of tradition remains unbroken from generation to generation, each adding its own link…I believe that the elimination of women from such duties was never intended by our law and custom.”

12. She died in Jerusalem at Hadassah Hospital in February 1945, and was buried on the Mount of Olives. In Israel, Mother’s Day is celebrated on 30 Shevat, the day of her death.

In Tel Aviv, Henrietta Szold Street runs north-south off the eastern end of Arlosoroff. In Haifa, you’ll find it in the Central Carmel district. Kibbutz Kfar Szold in the upper Galilee is named for her, as is PS134 on East Broadway in Manhattan.

“Dare to dream…and when you dream, dream big.”

“Dare to dream…and when you dream, dream big.”

July 30, 2013

10 Things You Should Know About… Shaul Tchernichovsky

Hebrew poet, one of the greats

1. He was born in the Crimea in August 1875 and had a basic Jewish education. This was followed by a relatively secular education. He studied German, French, English, Greek and Latin. He attended secondary school in Odessa from 1890-92, when he had his first poem published.

2. Because he could not gain acceptance to a Russian university, in 1899 he went to Heidelburg, where he studied medicine. He finished his degree in Lausanne in 1906.

3. He practiced medicine and served in the First World War as a Russian army doctor. After the Bolshevik revolution, he continued to practice medicine and to write, but he earned only a scant livelihood.

4. He left Russia in the early 1920s and wandered here and there, settling in Berlin, where he did his translations. In less than a decade, he was to translate Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and also Sophocles, Horace, Shakespeare, Moliere, Pushkin, Goethe, Heine, Shelley, the Gilgamesh cycle, and the Icelandic eddas - all into Hebrew. To this day, Tel Aviv gives a prize in his name for exemplary translation.

4. He left Russia in the early 1920s and wandered here and there, settling in Berlin, where he did his translations. In less than a decade, he was to translate Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and also Sophocles, Horace, Shakespeare, Moliere, Pushkin, Goethe, Heine, Shelley, the Gilgamesh cycle, and the Icelandic eddas - all into Hebrew. To this day, Tel Aviv gives a prize in his name for exemplary translation.

5. Between 1925 and 1932, he was one of the editors of the newspaper HaTekufa. He spent part of 1929-30 in America. Then, in 1931, he was commissioned to edit a Book of Medical and Scientific Terms – in Latin, English and Hebrew. This commission enabled him to make aliyah to Palestine.

6. He became the physician for the Herzliya High School and later for Tel Aviv’s municipal schools. He was active, too, in writers’ organizations and the Committee on the Hebrew Language, serving as editor of the Hebrew terminology manual for medicine and the natural sciences.

7. Throughout all this, he continued to write poetry. He was twice awarded the Bialik Prize for literature, in 1940 and ’42.

8. His poetry was influenced by Jewish cultural heritage and by ancient Greek culture. He is especially known for his sonnets. He introduced into Hebrew the “crown of sonnets,” a grouping of 15 individual sonnets in which the last poem is made up of the first lines of the other 14.

9. Collections of his poetry have been translated into English, French, Russian, Spanish and Yiddish, and individual poems have made their way into Arabic, Czech, Dutch, English, Esperanto, Estonian, French, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Yiddish. In addition, many of his poems have been set to music by Hebrew composers.

10. Tchernichovsky died in October 1943. In 2011, he was chosen to be one of the four great Israeli poets whose portrait would grace Israel’s currency.

Want to see the difficulty of translation? Here are two versions of a quatrain from one of Tchernichovsky’s sonnets. The first, edited by Stanley Burnshaw, is closer to direct translation from the Hebrew. The second, by A. Z. Foreman, seeks to convey more closely the spirit of the words. Which do you prefer?

Eagle! Eagle over your mountains, an eagle is flying over your mountains!

Soaring, gliding - gliding, and with wondrous touch did not move a wing.

For an instant – it froze, then – the barest movement in its wings

The slightest tremble suddenly – and it rises toward the cloud.

___________

Hawk! A hawk atop your hills! A hawk atop your hills on high:

Gliding wide with wondrous touch, with wings locked back against the sky,

Frozen for a moment, then a single pinion barely sways.

Now the slightest palpitation, and it surges toward the haze.

______________

Find Tchernichovsky Street in Tel Aviv parallel to King George Street, west of it, running between Allenby and Dizengoff.

July 24, 2013

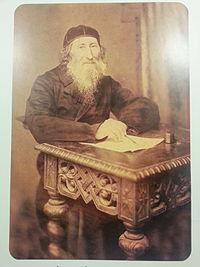

10 Things You Should Know About… Zvi Hirsch Kalischer

Proto-Zionist

1. He was born in Lissa in the Prussian province of Posen (now Lesano, Poland) and educated for the rabbinate, studying with two of the leading Halachik authorities of the time. As an adult, he settled in Thorn, a city on the Vistula River, where he would spend his life, serving for forty years as “acting rabbi” and choosing to receive no remuneration for his work. Yes, he was supported by his wife, who ran a small shop.

1. He was born in Lissa in the Prussian province of Posen (now Lesano, Poland) and educated for the rabbinate, studying with two of the leading Halachik authorities of the time. As an adult, he settled in Thorn, a city on the Vistula River, where he would spend his life, serving for forty years as “acting rabbi” and choosing to receive no remuneration for his work. Yes, he was supported by his wife, who ran a small shop.

2. He wrote prolifically – commentaries on the Pentateuch, the Talmud, the Haggadah and the Shulhan Aruch; he contributed, as well, to several Hebrew periodicals, including one called HaLevaron. His Sefer Emuhah Yesharah is an inquiry in two volumes into Jewish philosophy and theology, written after he had studied medieval and then-current Jewish and Christian philosophy.

3. The first known expression of his Zionist ideas came in a letter to the head of the Berlin branch of the Rothschild family. The year was 1836. He believed that the redemption of Zion would have to begin with action on the part of the Jewish people, and that only then would come the messianic miracle. Salvation, in other words, would come to the Jews through self-help and through emigration to the Land of Israel – and through this would come salvation of the world.

4. The reform movement at the time was turning Jews’ attention to their “host countries.” Kalischer’s orthodoxy focused on Palestine. He proposed collecting money from Jews of all nations; buying and cultivating land in Eretz Israel; founding an agricultural school there or in France; and, ultimately, forming a Jewish quasi-military guard for security of the settlements.

5. He put these ideas forward in articles in HaLevaron and, in 1862, in a book called Drishat Tzion (Seeking Zion), the first Hebrew book to appear in eastern Europe on the subject of modern Jewish agricultural settlement, proposing settling the Land of Israel with homeless Jews of eastern Europe and also providing beggarly Jews in Palestine the ability to support themselves by agriculture.

6. The book was translated into German in 1865. Kalischer traveled to cities all over Germany for the purpose of setting up colonization societies and raising money for them. His efforts led to the establishment of the Mikveh Israel agricultural school in Israel (southeast of Tel Aviv) in 1870.

7. It was he who formulated the ideology of national orthodoxy – that the Jewish people were a nation and that their aspiration to re-establish their historical homeland was fully legitimate. This idea had a strong influence upon Heinrich Graetz (see my post of July 17), among others, becoming the foundation for later religious Zionist thought.

8. Throughout his adult life, he kept up a wide correspondence with rabbis, public figures and benefactors throughout Europe. Among these were Moses Montefiore, Anschel Rothschild and Albert Cohen. A collection of his letters was published in 1946.

9. He died in October 1874 and was buried in Thorn. Later, a plot was purchased for him near Rachel’s tomb with funds raised in a deposit box that he’d always kept on his desk for contributions to Jewish settlement.

10. He wrote: “When we redeem the land, we make a pathway for our God and a  way towards final redemption.”

way towards final redemption.”

Tirat Tzevi, a religious kibbutz in the Bet She’an valley, is named for him.

Kalischer Street is located in Tel Aviv off HaCarmel, a short walk southwest from the maket and Nahalat Binyamin.

July 17, 2013

10 Things You Should Know About… Heinrich Graetz

First modern Jewish historian

1. He was born Tzvi Hirsh Graetz to a butcher’s family in Poznan – then Prussia, now Poland - in October 1817. He received a traditional education in a yeshivah, though he had an interest, as well, in secular studies, which he pursued privately. Initially, he was influenced by Samson Raphael Hirsch, a champion of orthodox Judaism, and spent three years as his pupil and secretary.

2. He was awarded a doctorate by the University of Jena, though he had studied at the University of Breslau: Jews could not receive doctorates at Breslau. In 1845 he became principal of a Jewish school in Breslau and later taught history at the Jewish Theological Seminary there.

3. His History of the Jews, told from a Jewish perspective, ran to eleven volumes. Quickly and widely translated, it ignited worldwide interest in Jewish history. And in a bit of poetic justice, earned him the title of Honorary Professor at the University of Breslau.

4. The fourth volume was the first to be published, in 1853. It was followed by the third in 1856, and then, rapidly and in succession, the sixth to the eleventh, which came out in 1870, bringing the history up to the year 1848. For the first two volumes, covering the earliest period of Jewish history, he traveled to Palestine to do research in 1872, and had completed the history by 1876.

5. The work was difficult, drawing on sources scattered over nations and continents and written in many languages. Chronological sequences often had to be interrupted. But he wrote sympathetically, vividly, passionately, reconstructing the past with a remarkable grasp of the sweep of history, though he was wrong in many of the details.

5. The work was difficult, drawing on sources scattered over nations and continents and written in many languages. Chronological sequences often had to be interrupted. But he wrote sympathetically, vividly, passionately, reconstructing the past with a remarkable grasp of the sweep of history, though he was wrong in many of the details.

6. He emphasized the contribution of the Jewish people in realizing the divine will, of Jewish spirituality as expressed in literary sources, and of the spiritual stirrings of the Jewish heart as the essential feature of their political and social life. Still, he ruffled feathers.

7. His fourth volume (remember – the first to be published) was reviewed by Rabbi S. R. Hirsch in a group of essays that grew to 203 pages and must have stung Graetz deeply. The exhaustive treatment showed the scholarship to have been sloppy, omitting parts of quotations, fabricating dates, and making conclusions based on little or faulty evidence. His eleventh volume gave rise to attacks, notably by the historian Heinrich von Treitschke, of hatred of Christianity, bias against the German people, and Jewish chauvinism. His work was quoted as proof that the Jews would never be able to assimilate themselves into European culture.

8. It’s true that his mammoth work was full of ad hominen arguments, preconceived notions, and attacks against Christianity. Scenes were imaginatively rendered, often based on flimsy evidence. Graetz might rightly be called the father of the lachrymose vision of Jewish history, for his narrative is drenched in darkness and suffering.

9. Nevertheless, he succeeded in presenting for the first time the whole of Jewish history. Indeed, the great Jewish historians of the twentieth century wrote their histories in response to Graetz’s work.

10. Though he published an anthology of Hebrew poetry and a one-volume edition of the Jerusalem Talmud, his reputation rests on the history, because it became the first standard work in the field of modern Jewish history. He died in September 1891.

You can find Graetz Street in Tel Aviv running north from Ben Gurion between Ben Yehudah and Dizengoff, and in Jerusalem south of Liberty Bell Park off Emeq Refa’im.

July 10, 2013

10 Things You Need to Know About Soncino

Distinguished Printers of Hebrew Books

1. The Soncino family were Italian Sephardic printers who derived their name from the town of Soncino in the duchy of Milan.

2. In Soncino in 1483, Nathan ben Samuel set up a Hebrew printing press. On February 2, 1484, he published his first Hebrew book – the Talmud tractate Berakhot.

3. Over the next century, through five generations, the press moved to many locations in Italy and as far abroad as Constantinople and Salonica. They published mostly Hebrew titles, but also general works and even works of religious significance with Christian symbols.

4. In all, over 100 Hebrew books were printed, including books of the Talmud, mahzors, haggadot, Maimonides, Judah ha-Levi, Rashi, responsa, prophets, proverbs, Ibn Gabirol and the Pentateuch (see below). An equal number of books appeared in Latin and Italian. Their printer’s mark was a tower.

4. In all, over 100 Hebrew books were printed, including books of the Talmud, mahzors, haggadot, Maimonides, Judah ha-Levi, Rashi, responsa, prophets, proverbs, Ibn Gabirol and the Pentateuch (see below). An equal number of books appeared in Latin and Italian. Their printer’s mark was a tower.

5. They printed the first Hebrew language Bible. Though they were not the first to publish in Hebrew, they were notable for the quality of their publications.

6. Gershon Soncino was the most famous of this family. His first book was Sefer Mtizvot Gadol by Moses of Courcy, published in 1488. The Library of Congress has two copies of this book in its Jefferson Library collection. In one of the copies is a handwritten bill pasted in the flyleaf signed “Gershon, the son of Moses Soncino of blessed memory, Printer.” It’s dated 25 Tevet 5249 (December 1488) in Soncino.

7. The last of the Soncinos worked in Constantinople, and the last printed book came out in the mid-16th century.

8. But if you are of a certain age, you know the Soncino Chumash, published in 1947 and edited by Chief Rabbi Joseph H. Hertz. It was published by the modern Soncino Press, based in the UK.

9. The Soncino Press uses the tower as a trademark.

10. The Soncino Books of the Bible, published in 14 volumes between 1945 and 1952 and edited by Dr. Abraham Cohen, contains wide-ranging commentaries covering the whole Tanakh. A second edition, deleting works from historical scholars and Christian commentators, was edited by Rabbi Abraham J. Rosenberg and published in 1990.

You’ll find Soncino Street in the Shekhunat Montefiore area of Tel Aviv.

June 26, 2013

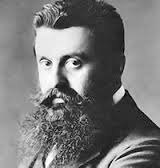

12 Things You Need to Know About… Theodor Herzl

The visionary behind the State of Israel

1. Theodor Herzl was born Benjamin Ze’ev Herzl in May 1880, in Pest, Hungary, the younger child of German-speaking, assimilated Jews. His upbringing, as he described it, was “thoroughly emancipated, anti-traditional, secular.” He was a “would-be German boy” who viewed religion as uncivilized. Indeed, there was a time when he thought the best solution to the “Jewish problem” in Europe would be mass conversion of the Jews – but this was before the Dreyfus Affair.

2. Following the death by typhus of his sister, the family moved to Vienna, where he studied law at the University, encountering anti-Semitism. After a brief legal career, he became a journalist and devoted himself to writing. He authored some plays and became a correspondent for the Viennese newspaper Neue Freie Press, where he also served as literary editor. In 1891, he became the Paris correspondent for the paper.

3. 1895 was a watershed year for Herzl. The Dreyfus Affair broke, and he followed the trial for his paper. At the same time, in Vienna, an anti-Semitic demagogue named Karl Lueger rose to power. Herzl was converted to a new view of European anti-Semitism: that it could not be overcome by any means, only avoided by the establishment of a Jewish state.

3. 1895 was a watershed year for Herzl. The Dreyfus Affair broke, and he followed the trial for his paper. At the same time, in Vienna, an anti-Semitic demagogue named Karl Lueger rose to power. Herzl was converted to a new view of European anti-Semitism: that it could not be overcome by any means, only avoided by the establishment of a Jewish state.

4. His 86-page pamphlet, Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State) came out in early 1896 to immediate acclaim by existing Zionist groups such as Hovevei Zion; and to vilification by establishment Jewry who either felt their own assimilation threatened by it or thought that Herzl’s ideas went against God’s will.

5. Having visited Baron de Hirsch, members of the Rothschild family, Jewish architect Oskar Marmouk and journalist Friedrich Schiff with no great result, he proceeded to wangle “direct and publicly known” meetings with heads of state in order to legitimize his standing with his fellow Jews, so that they would “believe in me and follow me.” He met with the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Court, offering payment by Jews of the entire Turkish foreign debt in return for Palestine as a Jewish homeland under Ottoman rule. Five years later, he met with the Sultan, who turned down the offer. He met with Bismarck. He met with the Grand Duke of Baden, uncle of Kaiser Wilhelm II.

6. He had popular support. In July 1896, in London’s East End, an enthusiastic crowd greeted him at a mass rally. The following year, he founded the Zionist newspaper Die Welt, and with his friend Max Nordau planned the first Zionist Congress [see my blog post of June 19]. It was the very first inter-territorial gathering of Jews to be held on a national, secular basis; and it brought together about 200 delegates, mostly from central and eastern Europe, with a handful from western Europe and from the United States. They elected him President of the organization, a position he held until his death.

7. More visits: In 1898, he went to Palestine, coordinating his trip with that of Kaiser Wilhelm. They met twice, but Wilhelm dismissed his entreaties with anti-Semitic remarks.

8. He was deeply affected by the Kishinev pogroms of 1903, of the desperate condition of Russian Jews, and continued to seek the support of world leaders for a Jewish homeland. Through connections with the British government, he negotiated with Egypt for a charter to settle Jews in the Sinai; he sought the Pope’s aid, but he was denied – as long as the Jews continued to deny the divinity of Jesus.

9. Finally he received an offer from the British to facilitate a resettlement of a large number of Jews in East Africa, where they would have an autonomous government under British suzerainty. After traveling to Russia to obtain the approval of that government, he presented the “Uganda Program” to the Sixth Zionist Congress in Basel in August, 1903. A motion to investigate the offer further was carried by a vote of 295 to 198 with 98 abstentions (the Russian delegation walked out in protest.) The plan was rejected at the Seventh Zionist Congress in 1905.

10. Herzl’s last literary work, Altneuland (Old New Land), a novel, was published in 1902. In it, he envisioned what would be accomplished by 1923 in a state combining Jewish culture and European heritage. The government he imagines is not a religious state, though the Temple has been rebuilt. Economically, he foresees a “third way” between capitalism and socialism. Socio-politically, he sees no conflict with the Arabs; and women have political equality.

11. He died on July 3, 1904, of illness variously described as a heart ailment, cardiac sclerosis and pneumonia – all of which may be true. “Greet Palestine for me,” he told a friend. “I gave my heart’s blood for my people.” In 1949, his remains were moved from Vienna and reinterred in Jerusalem on Mount Herzl.

12. How to sum up his contribution in one bullet point: having offered a reassessment of the Jewish problem as a national problem requiring an international political solution, Herzl initiated diplomatic steps toward that end; and having proposed a practical program for collecting funds from Jews around the world (the blueprint for the Zionist Organization), Herzl strengthened the ties of Jews around the world through his indefatigable efforts traveling, writing, speaking.

Theodor Herzl has been commemorated on Mount Herzl; in the Herzl forests at Ben Shemen and Hulda; in the Herzliya Gymnasium, the first Hebrew language high school; in the city of Herzliya; and in neighborhoods and streets all over Israel.

A note to the followers of this blog: Well, I’ve done it, tackled Herzl, a task and an opportunity that I’ve been ducking for half a year. I deserve a break, so in honor of Independence Day, and in commemoration of the anniversary of Herzl’s death, I’m taking next week off. Look for a new post on July 10.

June 19, 2013

Ten Things You Need to Know About… Max Nordau

Cofounder of the World Zionist Organization

1. Max Nordau was born Simon (Simcha) Maximillian Sudfeld in Pest, Hungary, in July 1849. His father was a Hebrew poet.

2. He studied to be a physician, earning his medical degree from the University of Budapest in 1872. In 1873 he changed his name to Max Nordau (more about this below). He served for six years as an Austrian military surgeon; then, in 1880 he moved to Paris, where he would spend most of his life.

3. He considered himself fully assimilated. “When I reached the age of fifteen,” he wrote, “I left the Jewish way of life and the study of Torah….Judaism remained a mere memory and since then I have always felt as a German and as a German only.” Hence the name change.

3. He considered himself fully assimilated. “When I reached the age of fifteen,” he wrote, “I left the Jewish way of life and the study of Torah….Judaism remained a mere memory and since then I have always felt as a German and as a German only.” Hence the name change.

4. Then came the Dreyfus Affair. In Paris, he attended the trial, reported on it, and witnessed a mob screaming, “Death to the Jews!” He concluded that anti-Semitism was universal. And therefore, that Zionism was a necessity.

5. Theodor Herzl was in Paris working as a correspondent to a Vienna newspaper. Nordau, as his friend and advisor, was the one who convinced Herzl of the need for democratic assemblies in the Zionist movement. Nordau organized the first Zionist Congress, held in Basel in 1897; there would come to be 11 in all.

6. Nordau had already achieved fame as an intellectual and essayist, who wrote on contemporary art, society and politics. His works were widely translated, and his involvement lent the congress a certain vogue. He spoke second at the conference, after Herzl, offering statistics that documented the miserable condition of Eastern European Jews and then expressing his belief in the future establishment of a democratic nation-state.

7. In 1898, at the second Zionist Congress, he coined the term “muscular Judaism” to describe the discipline and agility of a stronger, more physically assured Jew – replacing the physically weak, intellectually sustained stereotype. Though he railed against such characterizations, he himself believed that the Jew had a special genius for politics.

8. He supported the Uganda Plan, coining the term “night shelter” to describe a temporary solution to the precarious condition of so many Eastern European Jews.

8. He supported the Uganda Plan, coining the term “night shelter” to describe a temporary solution to the precarious condition of so many Eastern European Jews.

9. He is best known today for his book Degeneration (1892), an attack on what he considered degenerate art. Always controversial, other works of social criticism included The Conventional Lies of Our Civilization (1883) and Paradoxes (1896). He died in Paris in January 1923; three years later, his remains were moved to Trumpeldor Cemetery in Tel Aviv.

10. Here’s one of my favorite quotes from Nordau, though I’m certain he would not appreciate my amused and ironic take on it: “Degenerates are not always criminals, anarchists and pronounced lunatics; they are often authors and artists.”

You’ll find Nordau Street in Tel Aviv not far from the port. In Jerusalem, Kikkar Nordau is located near the central bus station. Look for him in Haifa, too.

June 12, 2013

10 Things You Need To Know About… Yehuda Leib Gordon

Poet of the Jewish Enlightenment

1. Y.L. Gordon was born in 1831 in Vilna. His parents were well-to-do hoteliers. He studied Torah and Talmud, and he began writing Hebrew poetry at a young age.

2. He became a teacher in some of Europe’s major yeshivot, and his poetry began to be widely read.  “The Love of David and Michal” (1856) was noteworthy for its attempt to voice the concerns, feelings and even the sexuality of a woman. Indeed, much of his poetry used biblical themes to espouse enlightenment values.

“The Love of David and Michal” (1856) was noteworthy for its attempt to voice the concerns, feelings and even the sexuality of a woman. Indeed, much of his poetry used biblical themes to espouse enlightenment values.

3. More evidence of his enlightenment philosophy appears in his “Fables of Judah” (1859), which included stories of Aesop, LaFontaine and Ivan Krylov.

4. Two of his most famous poems urged Jews to partake in Russian and western culture while remaining committed to Jewish culture. His most famous line – from “Awake, My People” (1863) - was widely quoted, becoming a rallying cry for the Haskalah (secularist) movement: “Be a man in the streets [outdoors] and a Jew at home [in your tent].” In “The Tip of the Yud,” (where Yud refers to the Hebrew letter) Gordon called for the Jewish woman’s liberation from traditional roles, so that she, too, could benefit from enlightenment ideas.

5. Gordon’s style was modern, rather than biblical, though it was full of references to biblical and rabbinic words and thought. He wrote mostly in Hebrew, only occasionally in Yiddish, viewing Yiddish as a language of degradation.

6. In 1872, he moved to St. Petersburg, where he served as secretary of the St. Petersburg Jewish community and the main branch of the Society for the Promotion of Culture Among the Jews of Russia. His fervor for western ideas brought him into conflict with Orthodox Jewry. Denounced to the Russian authorities for alleged anti-tsarist activities, he was sent into internal exile within Russia. But exile did not stop him from writing his anti- traditionalist, pro-humanist verse. His “King Zedekiah in Prison” is one example from this period.

7. After his return to St. Petersburg, he became editor of HaMelits, the most important Hebrew newspaper of the time. In his daily columns, he continued to promote enlightenment ideals, urging the translation of general literature into Hebrew and the education of Jews in Russian (and other languages) as well as Hebrew.

8. Following the assassination of Tsar Alexander in 1881 - with its subsequent pogroms and the consequent development of Jewish nationalism – Gordon hung on to his liberal, reformist stance, thus coming into conflict with Jewish nationalists. He supported emigration to the United States, rather than Palestine, for he was concerned that Jewish hegemony in Eretz Yisrael would lead to a theocracy if Judaism was not first purged of its religious traditionalism. (Hmmmm.)

9. He died in 1892, having been repudiated by his friends, who no longer subscribed to his liberal, pre-nationalist ideology. He died believing that “our spiritual deliverance” had to be a precursor to the Jewish physical return to Zion.

10. He is remembered as a poet who projected the image of a prophet, a forerunner of Bialik.

You can find Gordon Street in Tel Aviv off Rabin Square, running between the sea and the square.