Marilyn Oser's Blog, page 7

November 6, 2013

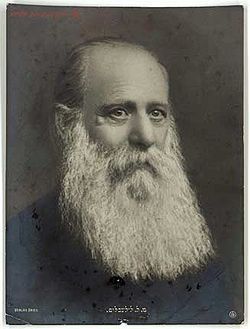

10 Things You Need to Know About… Kalonymus Ze’ev Wissotzky

Merchant and philanthropist

1. Kalonymus Wissotzky was born in 1824 in Zhagare in the Kovno province of Lithuania. As a young man, he attended yeshivot in Volozhin and in Kovno. It was during this time, influenced by his studies with the Salanter rabbi, that he resolved to dedicate ten percent of his income to charity.

2. Having tried, but failed, at farming, he moved to Moscow and established a tea company. This was either in 1849 or 1858, depending on which source you believe, but what is certain is that by the 1870s, he had become a major force in tea trading.

3. He owned the concession for the tsar’s entire military operation. He opened branches in New York, London and elsewhere. The Wissotzky Tea Company in Israel today descends from his firm.

4. He was an early and dedicated supporter of Jewish settlement in Palestine. A proponent of Hovevei Zion, he gave money for establishment of neighborhoods in Jerusalem, helped finance a Jewish school in Jaffa, and funded land purchases for Jewish workers. He was a member of the Odessa Committee, which promoted aliyah, and he later gave to the Zionist movement.

5. His support went, as well, to Jewish causes closer to home. He gave help to Jewish soldiers stationed in Moscow, contributed to the Society for the Promotion of Culture among Jews in Russia, provided funding for the yeshiva in Volozhin, and gave his support to the Alliance Israelite Universelle and to ORT (ORT is a Russian acronym for “Society for Trades and Agricultural Labor”).

6. After the pogroms of 1881, he became active in Agudat Ohave Zion and then a member of the central committee of Hovevei Zion. In 1885 he visited Eretz Yisrael and prepared a survey of the general conditions there. His report was influential in the further work of Hovevei Zion.

7. Among his favorite philanthropic interests was Hebrew literature. Ha Shilo’ah, a Hebrew monthly, was initially financed by him. Influenced by his London manager Ahad Ha’Am [see my post of April 24, 2013], in 1894 he tried to foster the publication of a Hebrew encyclopedia for Jewish studies, but the project fell through; the 20,000 rubles originally intended for it were given instead to foster in other ways the haskalah (the enlightenment) of Jews in Russia.

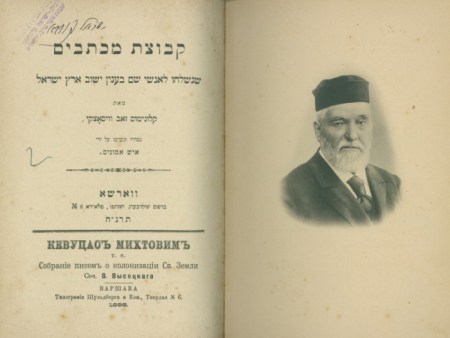

8. In 1898 a collection of his letters was published containing his impressions of the Land of Israel and his activities there.

8. In 1898 a collection of his letters was published containing his impressions of the Land of Israel and his activities there.

9. So widely known was his name that during the Russian Revolution an anti-Semitic ditty went around: “Tea of Wissotzky, sugar of Brodsky, and Russia of Trotsky.”

10. He died in 1904. In his will, he left his entire share of the Wissotzky Tea Company – a million rubles – to charity. Of this sum, 100,000 rubles was used for the establishment of the Haifa Technion.

In Tel Aviv, Wissotzky Street is located north of Jabotinsky and west of Derech Namir off Moshe Sharet.

October 30, 2013

10 Things You Need to Know About…Haviva Reik

Resistance fighter

1. Haviva Reik was born in June 1914 in the Slovakian village of Nadabula. One of seven children, she grew up in the Carpathian Mountains.

2. As a young woman, she joined the Zionist Socialist youth movement Hashomer Hatzair and in 1939 made aliyah. She joined Kibbutz Ma’anit, where she coordinated the citrus harvest. Before long, she enlisted in the Palmach.

3. In 1942, the Jewish Agency Defense Department, working in coordination with the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), asked the Palmach for volunteers to go behind enemy lines. They needed people who spoke the languages and knew the lands and cultures of Central Europe. Reik signed up. She joined the WAAF and received specialized training from the SOE.

4. She was with a group to be parachuted into Nazi-controlled Slovakia, but the British balked, refusing to send a woman on a “blind drop.” Determined not to be left behind, she hitched a ride with an American military transport and made her way to the rendezvous. The group set up their operations in Banska Bystrica.

4. She was with a group to be parachuted into Nazi-controlled Slovakia, but the British balked, refusing to send a woman on a “blind drop.” Determined not to be left behind, she hitched a ride with an American military transport and made her way to the rendezvous. The group set up their operations in Banska Bystrica.

5. An uprising had been planned there against the Nazi-controlled puppet government. Her group helped organize Jewish groups in the resistance. Reik was in charge of a public kitchen that served thousands of refugees; she facilitated the escape of Jewish children to Hungary and thence to Palestine; and she helped rescue Allied pilots who had been shot down. For six weeks, she carried out this double function, organizing Slovakian Jews and aiding Allied airmen.

6. The uprising was delayed, and the Germans advanced on their location in October of 1944. When her group prepared to escape to the mountains, she advocated for taking all the Jews who wanted to go, not just the young and healthy. Along with about forty Slovakian Jews, they set up camp in the forest.

7. The camp was overrun by Ukrainian pro-Nazi collaborators in November 1944. She was captured, executed and buried in a mass grave.

8. After the war, her body was exhumed and buried in a military cemetery in Prague. In September 1952, her remains were brought home and reburied in the Mount Herzl Cemetery in Jerusalem.

9. She wrote, “Every day we are alive is a gift from the heavens.” An excrutiating truth in her case, and not a bad existential stance for the rest of us.

10. Kibbutz Lahavot Haviva, Givat Haviva Institute, a river, a gerbera flower, a water resevoir, a ship used for (illegal) immigration to Palestine, and numerous streets in Israel are named in her memory.

In southeast Tel Aviv, Haviva Reik Street is located east of the Ayalon River and south of LaGuardia Street.

October 23, 2013

10 Things You Need to Know About… Yehudah Alharizi

Rabbi, translator, poet and traveler

1. Little is known about the early life of Judah ben Solomon AlHarizi. He was born about 1165 in Spain to a family that boasted at least one scholar and one poet of note. He became one of the last great personalities of the Golden Age of Jewish culture in Spain.

2. The first 25 years of his life were spent in study. He was fluent in Arabic, Aramaic, French, Latin and Greek, in addition to Hebrew.

3. At about the age of 25, he began to travel: to France, Italy, Greece, Syria, Palestine, Persia and Egypt. And he began to write poetry; his works are suffused with impressions from his journeys. For the rest of his life, he traveled, rarely spending a long time in any one place. After some lean years, he was comfortably supported by patrons.

4. He translated the Guide to the Perplexed of Maimonides from its original Arabic into Hebrew. His translation is considered more readable and understandable than the standard translation by Samuel ben Judah ibn Tibon, though less precise, less faithful to the original. It was his aim to prove that Hebrew had the grace and elegance of Arabic. He wrote, “They serve foreign tongues and despise their own.”

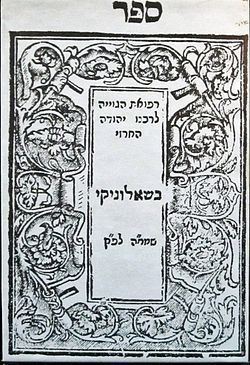

His medical treatise, Refuath Geviyah

5. A thorough rationalist, he also translated Artistotle’s “Ethics” and “Politics.” He translated several Greek and medical treatises and wrote a treatise of his own in Hebrew – leading scholars to propose that he may have been trained as a physician, though there is no record of his having practiced as one.

6. It is his poetry that made him famous, and among his works the Tahkemoni, composed 1218-20. Written in Hebrew, it takes an Arabic form called “makama,” a rhyming unmetrical style full of wit, fancy, and flowery language. AlHarizi added to this by interweaving Biblical style and sometimes whole sentences of text that were both incongruous and fitting in their new setting.

7. The Tahkemoni has two main characters: Heber the Kenite, called the Jewish Don Quixote because of his exploits; and Heman the Ezrahite, the narrator and interlocutor. The episodes are widely varied, containing philosophical discussions and tributes to past poets, but also a humorous debate between an ant and a flea.

8. His linguistic virtuosity is staggering, as demonstrated in his “Song of the Three Languages.” Each of its 23 lines is written one-third in Hebrew, a third in Arabic, and a third in Aramaic. The Arabic portion rhymes with the Hebrew throughout; the Aramaic portions have one, two-syllabled rhyme throughout.

9. He could be scathing about other poets of his time. Of a certain Syrian poet, he wrote,” When he a ditty writes or eke an ode – it sounds as if some pot or kettle did explode.”

10. AlHarizi died in 1225, but his writing lives on. A new edition of Tahkemoni, translated into English by David Segal, was published in 2003, and a critical-philological text by Joseph Yahalon came out in 2010.

“As if the word of the Lord of life – in Israel were no longer rife; like her of old – of whom we are told – other vineyards I protected – my own, alas, that I neglected!”

In Tel Aviv, Alharizi Street runs just south of Arlosoroff between Adam Ha-Cohen and Ibn Gevirol.

October 16, 2013

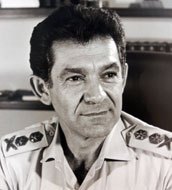

10 Things You Need to Know About… David El-Azar

Warrior for Israel

1. David “Dado” El-Azar was born in Sarajevo in August 1925, to parents of Sephardic heritage. His father was a partisan who fought against the Nazis in Tito’s guerilla forces.

2. In 1940, Dado made aliyah as part of the Youth Aliyah movement and settled in Kibbutz Ein Shemer. For a time he studied at Hebrew University.

3. He joined the Palmach and fought with them in a number of battles in the War of Independence. He was twice wounded in the battle for Jerusalem.

4. At age 24, he became the youngest battalion commander in the Palmach, heading up HaPortzim Battalion, part of the famous Harel Brigade led by Yitzhak Rabin.

4. At age 24, he became the youngest battalion commander in the Palmach, heading up HaPortzim Battalion, part of the famous Harel Brigade led by Yitzhak Rabin.

5. He stayed in the army following the establishment of the State of Israel. In 1961, he became commander of the armored corps, and is credited with building its strength. By 1964, he’d become chief of the Northern Command, and in this capacity oversaw the capture of the Golan Heights during the Six Day War (1967) – in just two days.

6. In 1972, he was appointed Chief of Staff of the IDF, its ninth. Terrorism became an important issue in these years – including Munich. It was difficult to know when to act and when not to. Under his command, for example, a Libyan airliner carrying civilians was shot down over Sinai when it did not respond to repeated requests. When the Egyptian army began carrying out frequent training maneuvers in the Sinai, lookouts began to ignore them. El-Azar became convinced that Egypt and Syria were about to attack and recommended complete mobilization, but the government, including Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, thought it unlikely and opted instead for a call-up of reserves coupled with an appeal for international pressure against Arab aggression.

7. Egypt and Syria attacked on Yom Kippur in what has become known as the Yom Kippur War. Israel was unprepared. The war, though successful for Israel, caused heavy casualties. Some commentators say that El-Azar’s ability to keep his cool during the early, trying days of the war led directly to Israel’s comeback and ultimate victory.

8. Nonetheless, El-Azar resigned his position after the war, following publication of a report that criticized his performance as Chief of Staff, saying he bore responsibility for assessment and preparedness.

9. He died of a heart attack in April 1976, and is buried on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem.

10. In 2006, in a poll of the general public, he was voted one of Israel’s top 200 greatest Israelis, coming in at number 107.

In Tel Aviv, El-Azar Street can be found in Neve Tzedek, near the sea.

In Haifa, it runs along the southern coast into Hubert Humphrey Street. Also, a street in Hadera is named for him.

October 9, 2013

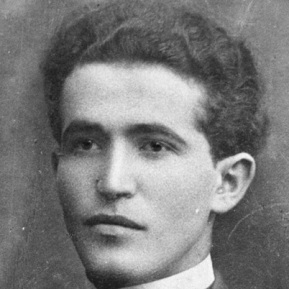

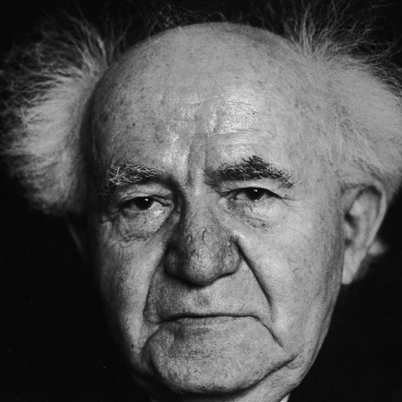

12 Things You Need to Know About… David Ben-Gurion

Israel’s founding father

1. David Grun was born in Plonsk, Poland (then part of the Russian Empire) in October 1886. His father was a lawyer and ardent Zionist. In this case, the apple didn’t fall far from the tree. The son was educated in a Hebrew school and at age 14, with two friends, formed Ezra, a club intended to promote emigration to Palestine. Its members spoke only Hebrew among themselves.

2. As a student at the University of Warsaw, he joined Poalei Zion. In the 1905 uprising that shook the Tsarist regime, he was arrested. In 1906 he left for Palestine, though he insisted that it was not because life in Poland had become untenable; rather it was “for the positive purpose of rebuilding a homeland….Life in Plonsk was peaceful enough.” Following his arrival in Jaffa, he was elected to the central committee of the newly formed branch of Poalei Zion.

2. As a student at the University of Warsaw, he joined Poalei Zion. In the 1905 uprising that shook the Tsarist regime, he was arrested. In 1906 he left for Palestine, though he insisted that it was not because life in Poland had become untenable; rather it was “for the positive purpose of rebuilding a homeland….Life in Plonsk was peaceful enough.” Following his arrival in Jaffa, he was elected to the central committee of the newly formed branch of Poalei Zion.

3. At age 20 he was involved in creating the first agricultural workers’ commune (“Kvutzah,” eventually “Kibbutz”). He was a laborer, picking oranges in Petach Tikvah, doing other agricultural work in the Galilee, withdrawing from politics. In 1908 he joined an armed group acting as watchmen at Sejera and fought a skirmish there. Then he volunteered with Hashomer, a force of volunteers being organized to guard isolated settlements.

4. In 1911 he went to Thessalonika to learn Turkish in preparation for law school. By 1912, he was studying law in Istanbul. It was then that he adopted the name David Ben-Gurion (after the medieval historian Joseph Ben Gurion).

5. At the start of World War I, he was living in Jerusalem. Believing that the future of the Jews lay with the Ottoman Empire, he joined with Yitzhak Ben-Zvi (with whom he’d attended school in Istanbul, and who would later become Israel’s second president) to recruit a Jewish militia to assist the Turks. No dice: he and Ben-Tzvi were deported anyway, in March of 1915. They made their way to the United States, where they tried to raise funds for an army to fight for Turkey. He married in New York in 1917; and that same year following the issuing of the Balfour Declaration, he changed his thinking about what was best for the Jews. In 1918 he returned to Palestine as a member of the Jewish Legion to fight with the British against the Ottomans.

5. At the start of World War I, he was living in Jerusalem. Believing that the future of the Jews lay with the Ottoman Empire, he joined with Yitzhak Ben-Zvi (with whom he’d attended school in Istanbul, and who would later become Israel’s second president) to recruit a Jewish militia to assist the Turks. No dice: he and Ben-Tzvi were deported anyway, in March of 1915. They made their way to the United States, where they tried to raise funds for an army to fight for Turkey. He married in New York in 1917; and that same year following the issuing of the Balfour Declaration, he changed his thinking about what was best for the Jews. In 1918 he returned to Palestine as a member of the Jewish Legion to fight with the British against the Ottomans.

6. Following the war, and through the 1920s, Ben-Gurion increasingly took leadership of labor politics. Amid opposing ideas and factions, he was a founder of Histradut, which became a central force in the economic and social affairs of the Jews under the British Mandate. Its role, as he saw it, was to build a Jewish economy under the leadership of a Jewish working class. Labor Zionism became dominant in the World Zionist Organization, and by 1935 he was chairman of the Zionist Executive, the movement’s highest directing body, and head of the Jewish Agency, its executive branch. As such, he led the struggle for an independent Jewish state. He was an early supporter of the partition of Palestine, having tried in the 1920s to make peace with the Arabs, and failed. Initially a proponent of restraint with regard to using violence, he called for a “fighting Zionism” when Britain took a pro-Arab stance on the even of World War II.

7. He believed the Negev offered an opportunity for Jews to settle unimpeded and settled in a kibbutz there called Sde Boker. He also resided in Tel Aviv in what is now called Ben-Gurion House. It was in Tel Aviv in May 1948 that he declared the new State of Israel, a nation that, he said, would “uphold the full social and political equality of all its citizens, without distinction of religion, race.” Had he ever doubted this time would come? In 1946, he’d met and become friends in Paris with Ho Chih Minh. The latter offered a Jewish home-in-exile in Vietnam. Ben-Gurion turned it down, certain that a government would be established in Palestine. So it’s fitting that he was the first to sign the Israeli Declaration of Independence, which he’d helped write, and that he became the first Prime Minister.

8. He knew war would immediately come, and when it did he looked upon it as a means to conquer - and therefore confirm ownership of - the land. To do so, he consolidated the army, uniting the various Jewish militias – by force, when necessary – into the IDF, the Israel Defense Force.

9. As the first Prime Minister, he built state institutions and oversaw development of the country, including the absorption of great numbers of diaspora Jews. Among the national projects he presided over: “Operation Magic Carpet,” the airlift of Jews from Arab countries; construction of new towns and cities, settlements in the Negev, and construction of the national water carrier; creation of a unified school system. One controversy (there were many, but this one stood out) surrounded his working with West Germany to secure compensation for Nazi Germany’s treatment of Jews. Reparations in the amount of $715 million were paid.

10. Ben-Gurion continued in office as Prime Minister and then Minister of Defense and then Prime Minister again, until 1963, when he stepped down from office. In 1970, he retired from political life entirely. His years in office were marked by remarkable events (Suez Canal campaign, capture of Eichmann, establishment of a secret nuclear facility, to name a few), and always by intense political conflict. Even today, historians argue about his actions toward the Arabs, whether or not he was involved in a policy of forced expulsion.

11. What cannot be denied is the extraordinary way in which he combined a vision of Jewish unity with pragmatic politics and military tactics – plus a great sense of humor. Charismatic and controversial, he remains one of history’s great characters. Time Magazine named him one of the hundred most important people of the twentieth century. Consider this summary just a start: a dozen things can’t begin to scratch the surface of Ben-Gurion’s life and contributions. He wrote memoirs and published his collected speeches and essays. Start there. Then there are the biographies of him, the histories….

“Anyone who believes you can’t change history has never tried to write his memoirs.”

“Anyone who believes you can’t change history has never tried to write his memoirs.”

“If an expert says it can’t be done, get another expert.”

12. David Ben-Gurion died of cerebral hemorrhage in December 1973. He is buried alongside his wife, Paula, at Midreshet Ben-Gurion, a research center in the Negev.

In Tel Aviv, Sederot David Ben-Gurion runs toward the sea from the northwest corner of Rabin Square. In Haifa, it runs from the Bahai Gardens down toward the port.

The largest airport in Israel is named in his honor, as is the university in Beersheva. His home in Sde Boker is now a visitor’s center, the one in Tel Aviv a museum.

October 2, 2013

10 Things You Need to Know About…Joseph Caro

He codified Jewish law for everyone

1. Joseph Ben Ephraim Caro was born in Toledo, Spain, in 1488. A few years later Jews were expelled from Spain and then Portugal, and his family resettled in Nikopolis in the Ottoman Empire. His father, Ephraim, was an eminent Talmudist who taught his son well. After his death, young Joseph was brought up by an uncle. Death continued to stalk his family throughout his life: he married early, lost his wife, and went on to marry and lose several more. All together, he had six children.

Artist’s conception

2. As a young man, he earned a reputation for excellent scholarship. He wrote Kesef Mishnah, citing and explaining the sources in the Maimonides Mishneh Torah.

3. In 1535, after years spent in various locations in Turkey and then Egypt, he arrived in Palestine and settled in Safed, where, he was appointed to the Rabbinical Court of Jacob Berab. He established a yeshiva, teaching Torah to over 200 students.

4. When Berab died, Caro became head of the Rabbinical Court in Safed, by then the central rabbinical court of Palestine, its rulings considered final and conclusive throughout the Jewish world.

5. Contacted by sages throughout Palestine and the diaspora, who sought his halachic decisions and clarifications, he developed the grand idea to codify all Jewish law, not only applying the responsa of all the prominent legalists, but also taking community customs into account.

6. The result was his Beit Yosef, a commentary on the Arba’ah Turim (“the Tur”), the work of Jewish law then current. He began it in 1522 and finished twenty years later. His all-encompassing mastery of Talmud and legalistic literature is evident in it. He discusses every law starting with its source in the Talmud, tracing its development, considering every divergent view and finally ruling on the law – usually, though not always, basing his rulings on the majority view of Isaac Alfasi, Maimonides and Asher ben Yehiel.

7. Caro is best known today for his Shulhan Aruch (1565), a concise condensation of Beit Yosef that lists only the final rulings. The title translates as “The Prepared Table.” Written for young students, it made halachah available to even the simplest Jew. It was the first such code ever to be printed on a printing press, and it was distributed around the world. Because it was written primarily according to Sephardic tradition, it was later supplemented with Ashkenazic commentary by Moshe Isserles [see my post of May 15, 2013]. In this form it remains the go-to source today.

Caro’s signature

8. For a period of over fifty years, Caro kept a diary in which he recorded the mystical visits to him of an angelic teacher who instructed him, berated him, and spurred him to acts of righteousness. Many years after his death, the diary was published by Kabbalists as Maggid Meisharim (“Preacher of Righteousness”).

9. Caro produced other halachic works and many responsa. If you make it a practice to stay up all night on Erev Shavuot, you’ll be pleased to know that Caro was one of the originators of this practice.

10. Rabbi Yosef Caro died and was buried in Safed in March 1575. A synagogue there bears his name, though it is not the original synagogue, two others having been built earlier, but destroyed by natural disasters.

Rabbi Yosef Caro Street in Tel Aviv runs between Derekh Petach Tikva and the Ayalon River, just south (appropriately) of Isserles.

September 25, 2013

10 Things You Need to Know About… Josef Haim Brenner

Pioneer of modern Hebrew literature

1. Born in the Ukraine in the Russian empire in September 1881, Josef Haim Brenner had a yeshiva education and went on to teach Hebrew as a young man in Bialystok and Warsaw. In 1900, his first story was published, in the Hebrew newspaper HaMelitz. The following year he published a volume of stories.

2. Then he was drafted into the Imperial Russian Army (1902). Two years later, when war with Japan broke out, Brenner deserted and escaped to London.

3. In London, working as a typesetter, he was active in Poalei Zion. He edited and published a Hebrew periodical. He married and the couple had a son.

4. He made aliyah in 1909, working first as a farmer. He wanted to build the land, but the strain of manual labor proved too much. He began teaching at the Gymnasium Herzliya in Tel Aviv.

5. He kept writing. Modern Hebrew was in its infancy, and he experimented in both form and language. He sought to capture the sound of spoken Hebrew, and he used not only Hebrew vocabulary, but Aramaic, Yiddish, Arabic and English.

6. It was his aim to portray truth without any authorial intervention – an impossibility, of course, but a useful fiction. The subjects of his novels include moving from religious to secular life; military service; the life of Jewish workers in London; the life of the settlements in Palestine – in other words, he wrote from his own experiences. His characters wander, hoping to improve their destiny and failing. A deep sense of pessimism permeates his work.

“The old man and the youth were both crowned by thorns, as they stood the watch of life together. The sun was shining, life was full of thorns. The account was still open.”

“The old man and the youth were both crowned by thorns, as they stood the watch of life together. The sun was shining, life was full of thorns. The account was still open.”

7. His articles, plays and novels are firm in their advocacy of a secular Hebrew identity and in their concern for social justice. His characters are plagued by economic insecurity; they are left stranded, their goals unrealized, their lives bitter. They are savaged by poverty, disappointment and humiliation. Even life in Palestine is discouraging.

8. He wrote essays for Poalei Zion and was one of the founders of Histradut, the federation of Israel’s trade unions. And he translated Crime and Punishment and works by Tolstoy into Hebrew.

9. Today, his works are studied in academia and admired for their existentialist elements, but they are no longer well known to the general public.

10. Brenner died on May 2, 1921, killed in anti-Jewish riots in Jaffa. Brenner House stands at the site of his murder, a center for the Histradut youth organization. Kibbutz Givat Brenner, near Rehovot, is named for him, as is Israel’s Brenner Prize, a prestigious literary award.

In Tel Aviv, Brenner Street runs east from Allenby between Sheinkin and Balfour.

September 18, 2013

10 Things You Need to Know About… Yehudah Halevi

Poet, philosopher, physician

1. The life of Judah ben Shmuel haLevi, as it has come down to us, is long on legend and short on established fact. He was born in Spain during what is known as the Golden Age, in Toledo probably, but possibly Tudela, in either 1075 or 1086. Reliable childhood details are slim, but it is known that he was Jewishly educated and learned Arabic literature and the Greek sciences and philosophy.

2. He lived at various times in Toledo (which was Christian) and in cities of southern (Moorish) Spain. He was a busy physician, occupying an honored position as a community leader and intellectual. Of his family life little is known, but in his poetry he refers to a daughter and her son, named Judah.

3. He wrote prose in Arabic and poetry in Hebrew and is widely considered the greatest of all medieval Hebrew poets.

3. He wrote prose in Arabic and poetry in Hebrew and is widely considered the greatest of all medieval Hebrew poets.

4. Early on, he wrote poems of joy in friendship, love songs, drinking songs – poems full of delight in life. He wrote odes, epigrams, riddles and also religious verse. The themes and structure were common to many Hebrew poets of the time, employing complicated Arabic meters and Biblical diction. But Halevi brought special beauty to the sound of the poetry, a sparkling wit and a fine wedding of language, form and substance.

5. Here’s one brief example, translated by Robert Mezey:

Cups without wine are low things/Like a pot thrown to the ground/But brimming with the juice, they shine/Like body and soul.

6. At some point he experienced a religious awakening – possibly as a result of events in the world around him: it was the time of the first crusades. Whatever the reasons, he came to feel close to God and compelled to praise God. And for the Jewish people and their destiny, he felt a special bond. He believed that destiny lay in return to Eretz Yisrael.

7. Hundreds of his religious poems were dispersed widely, entering the liturgy of far-flung synagogues. Here’s one from the Tisha Ba’Av service:

Zion, wilt thou not ask if peace’s wing/Shadows the captives that ensue thy peace,/Left lonely from thine ancient shepherding?/Lo! west and east and north and south – worldwide/All those from far and near, without surcease/Salute thee: Peace/ And Peace from every side.

8. He produced a treatise known as Kuzari, structured as a dialogue between a Jewish sage and the king of the Khazars, a heathen tribe which converted to Judaism. In it, he argues for the superiority of religious revelation over philosophical systems as the guide to life. He argues that the Land of Israel and the people Israel are intrinsically holy, that the people Israel have a special spiritual position, and as a nation they are, to other nations, as the heart is to the rest of the body.

9. Believing that religious fulfillment was possible only in the presence of Israel’s God – and most possible in the Land of Israel – he left Spain and sailed to Egypt in September 1140. He remained in Egypt, visiting with friends and dignitaries, until May 1141, when he boarded ship for Palestine. He died that summer. The circumstances of his death are foggy. Legend has it that, upon arriving in Jerusalem, he was run over by an Arab horseman. However, it may, in fact, be legend that he reached Palestine at all. Though there are accounts of a visit in Tyre, recent research suggests he died in Egypt.

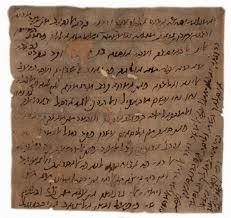

10. Yet he did write prolifically about his journey. Poems and letters (found in the Cairo geniza) explore his religious motivations, describe storms at sea, praise his hosts, and express his doubts and anxieties. These writings have been translated and are available in Song of the Distant Dove, by Raymond Scheindlin. For a quick look at Halevi’s poetry, try http://www.poemhunter.com

10. Yet he did write prolifically about his journey. Poems and letters (found in the Cairo geniza) explore his religious motivations, describe storms at sea, praise his hosts, and express his doubts and anxieties. These writings have been translated and are available in Song of the Distant Dove, by Raymond Scheindlin. For a quick look at Halevi’s poetry, try http://www.poemhunter.com

Yehuda HaLevi Street runs from Neve Tzedek northeast to central Tel Aviv, where it joins Ibn Gevirol.

September 4, 2013

Shanah Tovah 5774

August 28, 2013

10 Things You Need to Know About… Moshe Leib Lilienblum

Scholar, author, Zionist

1. Born in Lithuania in October 1843, he was given a traditional Talmudic education, and in 1865 started a yeshivah in Vilna.

2. Beginning In 1868, he wrote articles in Hebrew that called for reform in the practice of Judaism that would bring a closer connection between religion and life. He proposed changes in line with the changing conditions of modern life – suspension, for example, of the prohibition against legumes during Passover in the wake of a famine in Lithuania. He argued that the oral law was a human creation that had developed historically and contained internal contradictions. His language was sober, clear and well-reasoned – and it raised a storm of controversy in his orthodox surroundings. In 1869, having been denounced as a freethinker, he moved to Odessa.

3. Now the darling of the movement for reform, he nevertheless felt himself alone in Odessa, where he despaired of the possibility of a compromise between Jewish law and modern life. He read widely among radical writers, including Mapu [see my blog post of February 20]. Compelled by historical explanations for biblical composition, he lost his faith in the divine source of the Torah.

4. He edited a Yiddish newspaper in which were published a series of articles entitled “Jewish Life Questions.” He wrote, “All human beings live on the earth, but the Jews live in heaven. Even modern Jewish literature has not yet managed to come down to earth, and most of it hovers in the air.”

4. He edited a Yiddish newspaper in which were published a series of articles entitled “Jewish Life Questions.” He wrote, “All human beings live on the earth, but the Jews live in heaven. Even modern Jewish literature has not yet managed to come down to earth, and most of it hovers in the air.”

5. By 1873, at the age of 30, he was publishing an autobiography, The Sins of Youth, a narrative that reflected the spiritual and social problems of those who no longer fit into traditional society, but who found only frustration in the culture of the city.

6. In 1878, his parody of the Mishnah was published serially in a radical Hebrew journal. Using the form of the sacred text, he promulgated social, political and economic ideas of social reform. This secularization of holy language had a major influence on his peers.

7. The widespread pogroms of 1880-81 led Lilienblum to question his faith in progress, in the rule of human reason, and in the possibility of integration of Jews into European society. He later said that the close proximity of the pogroms led him to “know and feel the life of my nation during the exile.”

8. He now believed that the higher Jews rose on the social and economic ladder in their various countries, the more precarious their position would be. Security for Jews could only come in a territory where they could form a majority. Toward this end, in 1883 he founded the Odessa committee of Hovevei Zion and served as its secretary until his death, working alongside Leon Pinsker to organize and assist agricultural settlement while continuing his literary activities. Settlement of the land had become his priority, and he devoted much of his time to it; reform of Judaism took second place.

9. Lilienblum’s writings included poetry, literary criticism, a history of the Hovevei Zion movement, a psychological profile of Moses, two autobiographies (the second was published 1899), and a theatrical piece. Zerubavel, his Yiddish play, was the first modern drama to be produced on the stage in Eretz Yisrael, performed by students in Jerusalem in a Hebrew translation.

10. He died in 1910, having become one of the most important writers produced by the movement for a Jewish national culture. With his deep Jewish learning and his knowledge of European modernism, his writing – both literary and journalistic – argued persuasively for a new Jewish nationalism based on a new Jewish identity.

Kfar Mala is named for Lilienblum; an agricultural moshav in the Sharon region north of Petach Tikvah, it is also the birthplace of Ariel Sharon.

In Tel Aviv, Lilienblum Street runs between Neve Tzedek and Nahalat Binyamin and is known for its restaurants. The first cinema in Israel was established at 2 Lilienblum.