Marilyn Oser's Blog, page 6

January 15, 2014

10 Things You Need to Know About… Chaim Soutine and Amadeo Modigliani

Two Jewish artists

Portrait of Soutine by Modigliani

1. Chaim Soutine was born near Minsk in January 1893, the tenth of eleven children.

2. He studied art in Vilnius between 1910 and 1913, then went to Paris to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. In Paris, he became friends with Modigliani, who painted his portrait several times.

3. He was the typically penniless expressionist artist when, in 1923, he was “discovered” by American art collector Albert C. Barnes, who bought sixty of his paintings.

Painting by Soutine

4. A still life by Rembrandt influenced a series of paintings he did of a carcass of beef. These are now considered his masterpieces, but at the time caused something of a local uproar. It’s said that Marc Chagall was undone, believing Soutine murdered, when he found blood oozing out under the studio door. Then there were the neighbors – how would you feel if the artist next door kept a ripening carcass in his studio?

5. After the Nazi occupation of France, Soutine went on the run. He died of a perforated ulcer in August 1943.

Modigliani Self-portrait

6. Amadeo Clemente Modigliani, painter and sculptor, was born in Livorno, Italy, in July 1884. His father was a mining engineer from a family of successful businessmen; his mother was descended from a family of intellectuals learned in Judaica. Family lore said that Chaim unwittingly saved the family’s possessions when a downturn in the price of metals sent his father into bankruptcy. His mother was pregnant with Chaim at the time and went into labor when the bailiffs arrived. All the family’s valuables were piled on top of her, where they were safe from seizure.

7. The boy painted from an early age and studied art in Livorno. His adolescent years were sickly. He suffered from pleurisy and typhus and eventually contracted tuberculosis. In 1902, he went to Paris, where his addictions to alcohol and drugs became legendary. It’s now proposed that he might have taken drugs to mask his pain and his bouts of coughing, knowing that people would tolerate a drunk, but would shun someone with TB.

8. His work is characterized by asymmetry and elongation of form, with simple, strong lines and mask-like faces. He produced sculpture for a period between 1909 and 1914, influenced by Brancusi and by his study of African sculpture. A series of nudes shocked Paris when they were shown in 1917. Today, he is perhaps best known for his portraits.

Hebuterne Self-portrait

9. He was known back then for his outrageous behavior, sometimes stripping himself naked at parties. He had frequent affairs with women, notably the poet Anna Akhmatova, the poet Beatrice Hastings, and the flamboyant, high-strung painter Jeanne Hebuterne, who often made jealous scenes in public.

10. Modigliani died in January 1920. The following day, Hebuterne threw herself to her death from a fifth-story window, nine-months pregnant with their second child.

In Tel Aviv, you’ll find Soutine and Modigliani Streets, among a number of other streets named for artists, just north-east of Rabin Square.

January 8, 2014

12 Things You Need to Know About… Moses Maimonides

Philosopher, scholar and physician

Author’s Note: Before we begin, please let me take a moment to commemorate this Shabbat as the 100th anniversary of the Bar Mitzvah of Mischa Lefkovits. Who, you ask? Okay, Mischa is a fictional character, brother of Rivka in my novel Rivka’s War. She is so affected by his reading of the Haftarah that she runs out into the snow and throws up her breakfast. To find out why, you’ll have to read the book. If you like Jewish history, you’ll enjoy Rivka’s War. If you know anyone else who likes history, think about recommending the book. Many thanks.

Statue in Cordoba

1. Mosheh ben Maimon, called Moses Maimonides – also known as the RaMBaM, from Rabbeinu Moshesh Ben Maimon (our rabbi Moses son of Maimon) and as haNesher haGadol (the great eagle) – was born in Cordoba in 1135. At an early age, he showed an interest in philosophy and the sciences; he studied Torah with his father. Because of the ill-treatment of Jews in Spain, the family moved frequently and eventually settled in Fez, Morocco, where he attended university and was trained in medicine. It was during this time (1166-68) that he wrote his commentary on the Mishneh.

2. He traveled to Eretz Yisrael and then settled in Festat, Egypt. He continued his studies in a yeshiva in Cairo. During this time, he helped raise money to rescue Jews held captive by the Crusaders. After financial reverses upon the death of his brother, he took up the practice of medicine, eventually serving as court physician to the Grand Vizier, and then to Sultan Saladin. Though he worked full days as a physician, he nonetheless also wrote trenchant treatises on medicine, on Jewish law and philosophy. About 1171, he was appointed Negid, or leader, of the Egyptian Jewish community.

3. His medical writing stressed moderation in daily life. He described a number of conditions that had not yet been adequately documented, including asthma, diabetes, hepatitis and pneumonia.

4. Of course, it is his writings in philosophy and Judaism that interest us most. His books and letters and responsa have become a cornerstone of Jewish scholarship.

5. He is known for his adaptation of Aristotelian thought to Biblical studies and to faith. In this, he was influenced by Saint Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus. Central to his belief was the conviction that there could be no contradiction between the truths of revelation and the findings of science and philosophy.

5. He is known for his adaptation of Aristotelian thought to Biblical studies and to faith. In this, he was influenced by Saint Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus. Central to his belief was the conviction that there could be no contradiction between the truths of revelation and the findings of science and philosophy.

6. His Mishneh Torah, a fourteen-volume codification of Jewish law and ethics, was a milestone then, and remains a touchstone today. Written in Hebrew (most of Maimonides’ works were in Arabic), it was the first full, systematic commentary on the Mishneh. He propounded eight levels of giving charity; his thirteen principles of faith are rendered today in the hymn Yigdal.

7. He wrestled with definitions of God, of good and evil. Because of the impossibility of knowing God, he chose negative, rather than positive, terms; for example, rather than saying God is one, he said God is not a multiplicity. Evil, he believed, was the absence of good, which was created by God; evil exists, he said, wherever good is absent, and in the aggregate is but a small part of the world, when one considers all of creation.

8. His Guide for the Perplexed remains a great Jewish philosophical work, examining Aristotle in the context of Jewish theology. In all his works, he never wavered from the conviction that the path to perfection and immortality – resurrection would be incorporeal in the world to come – was the path of duty as prescribed in the Torah and Talmud.

9. Other works on Judaism include his Book of Commandments, on the 613 mitzvot; a Book of Martyrdom; a commentary of the Jerusalem Talmud, of which we have only a fragment; and possibly a Treatise on Logic, though the authorship of that is disputed. In addition, he published ten known medical works, including commentaries on the aphorisms of Hippocrates; a compilation of his own 1500 medical aphorisms, many describing illnesses; a treatise on hemorrhoids and their relation to food and digestion; a treatise on aphrodisiacs and anti-aphrodisiacs; on asthma, on poisons and their antidotes, on seizures and on healthy living. He also compiled a glossary of drug names in six languages.

10. With such an output, it was inevitable that his works would cause controversy, especially as regards his ideas concerning the necessary agreement of reason with revelation, and concerning the resurrection of the dead in the world to come. These one would expect. But even his codification of the law met with opposition, some critics believing that it would halt the study of Talmud.

11. When he died in the year 1204, the Jews of Egypt observed three full days of mourning. It is said that his remains were taken to Tiberias on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee, where the Tomb of Maimonides may be seen today.

12. This is my fifty-first post, and in all my attempts to distill the lives of great Jewish artists, writers, thinkers and statesmen, none has been as humbling as this one, leaving me feeling that I have not even scratched the surface. Best to say, with the voice of tradition, “From Moshe [of the Torah] to Moshe [Maimonides] there was none like Moshe.”

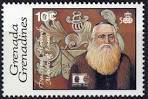

In Jerusalem, find Rambam Street running between the Knesset and the YMCA. Parallel to it runs Sderot Ben Maimon. In Tel Aviv, Rambam Street runs off Allenby to HaKarmel. In Haifa, it’s between Sderot Wingate and Leon Blum. There’s a Rambam Medical Center in Haifa and a Maimonides Medical Center in New York City; a Maimonides School in Massachusetts and a Maimonides Academy in Florida – and many more, no doubt. An Israeli stamp honoring Maimonides was issued in 1953. In 2004, Uruguay issued a postage stamp honoring him.

honoring Maimonides was issued in 1953. In 2004, Uruguay issued a postage stamp honoring him.

December 31, 2013

Happy New Year to All!

December 25, 2013

10 Things You Need to Know About… Isaac Abravanel

Jewish statesman, philosopher and financier

1. First, a word about the Abravanel family, one of the oldest and most distinguished families of Iberia, tracing their origin back to King David. Don Judah Abravanel (1284-1312) was treasurer and tax collector to the court; Samuel of Seville, known for his wisdom and goodness, was royal treasurer (1388); the family fled to Portugal after having been forcibly converted to Christianity – and then returned to Judaism. His son, Judah, was the father of Isaac. He, too, was in financial service, to the Portuguese court.

2. Don Isaac Abravanel was born in Lisbon in 1437. His scholarly promise showed early, as he studied Jewish philosophy and rabbinic literature. Not surprisingly, he had a superb understanding of financial matters, which caught the attention of the King of Portugal, who employed him as royal treasurer.

2. Don Isaac Abravanel was born in Lisbon in 1437. His scholarly promise showed early, as he studied Jewish philosophy and rabbinic literature. Not surprisingly, he had a superb understanding of financial matters, which caught the attention of the King of Portugal, who employed him as royal treasurer.

3. Wealthy in his own right and by virtue of his family, he was generous to the Jewish poor and spearheaded an effort to raise funds to free 250 Jews taken captive in Morocco. After their redemption, he supported them as they settled in a new place.

4. Upon the death of the Portuguese king, he was accused of conspiracy and had to flee to Toledo, leaving much of his fortune to be confiscated. Initially, he undertook Biblical studies there, in a scant six months producing extensive commentaries on the books of Joshua, Judges and Samuel. To each book he provided a general introduction and discussion of its date of composition and authorship – an innovation at the time.

5. He entered the employ of the court of Castile, again dealing in financial matters and eventually lending the king money to pursue the Moorish war. All this did not prevent the banishment of the Jews from Spain in 1492, though Abravanel did his best to persuade the king otherwise by both arguments and bribery.

5. He entered the employ of the court of Castile, again dealing in financial matters and eventually lending the king money to pursue the Moorish war. All this did not prevent the banishment of the Jews from Spain in 1492, though Abravanel did his best to persuade the king otherwise by both arguments and bribery.

6. He went to Naples and entered the service of the king there, but then war forced him to go to Messina; from there he went to Corfu, then to Monopoli, and finally to Venice, where he lived the rest of his life, starting over again and rising again to wealth and prominence.

7. His philosophy dealt with science and its relation to Judaism. He was not a rationalist, not a Kabbalist, but knew both streams of thought, as well as midrash, which he quoted liberally. He believed that the Torah is a revelation from God, and therefore not subject to human science. Christian scholars readily took up his work because of its accessibility (more about that below) and its focus on Messianic ideas. Abravanel fiercely defended the Jewish idea of the coming of the Messiah.

8. It was a time of hopelessness and despair for Jews from the Iberian peninsula. Under this pressure, with the danger of their Judaism disappearing, Abravanel made his works accessible to the common reader. His introductions were an innovation; in them, he listed questions that he sought to answer in his commentary. He compared the social structures in Biblical time with social and political conditions facing the Jews in his own time. This is perhaps his chief characteristic – the use of scripture to discuss contemporary Jewish problems.

9. Also notable in his work was his knowledge of Christian theology and his discussion of Christian exegesis where it was relevant to his commentary.

9. Also notable in his work was his knowledge of Christian theology and his discussion of Christian exegesis where it was relevant to his commentary.

10. He died in 1508. The Abravanel family has continued to produce scholars, physicians, writers and outstanding practitioners of the sciences and the arts up to the present.

Find Abravanel Street in Jerusalem between the Knesset and the YMCA, parallel to Rambam.

December 18, 2013

10 Things You Need to Know About… The Chelouche Family

Builders of Tel Aviv

Aharon Chelouche

1. Aharon Chelouche was born in Algeria in 1827 and made aliyah with his family while still a boy.

2. His two sons, Yosef and Avraham, were named for his two brothers who drowned when the family was shipwrecked on the voyage from Algeria.

3. He made his living as a goldsmith, trading in gold and silver, and as a money changer. And he bought land, lots of it. Some of the land he bought became Neve Tzedek, where he built a house in 1887. This was the first settlement outside of Jaffa’s walls. Adjoining the house, he built a synagogue, Beit Chelouche, which is still in operation today.

4. Aharon died in 1920, by which time his sons were active in Tel Aviv’s affairs. Yosef Eliyahu was educated in a Talmud Torah and at a Jewish school in Beirut. He married at age seventeen.

Yosef Chelouche

5. In the 1890s, he and his brother opened a store, Chelouche Freres, dealing in building materials. Later, they used the same name for a factory that produced building products.

6. Like his father, Yosef bought land. He became a building contractor, constructing many buildings in Neve Tzedek and, later, Tel Aviv. Thirty-two of the buildings of Ahazat Bayit were his, as was the Alliance School, now the Susan Dallal Center. The edifice of the Herzliya Gymnasium was another of his accomplishments.

7. In 1909, he was among the founders of Tel Aviv. He became a member of the first local council following World War I, and in the 1920s sat on the Jaffa city council.

8. Because he spoke Arabic, he was an important mediating force between Arabs and Jews. He believed the two peoples could co-exist peacefully and to their mutual benefit.

9. Yosef wrote a memoir, Reminiscences of My Life, in which he made an impassioned plea for Jewish understanding of, and outreach to, their Arab neighbors. An annotated edition of this work came out in 2005.

10. Yosef died in July 1934. The family continues to be involved in the life of Tel Aviv.

In Tel Aviv, you’ll find Chelouche Street in Neve Tzedek and Yosef Eliahu Street near the Frederic Mann Auditorium.

December 11, 2013

12 Things You Need to Know About… Yitzhak Rabin

Israeli statesman

1. Nehemiah Rubitzov, from the Ukraine, emigrated to the United States, where he changed his name to Rabin. Then, in 1917, he made aliyah to Palestine as part of the Jewish legion. He met the woman who would become his wife, and in March of 1922, Yitzhak Rabin was born. He grew up in Tel Aviv, where his parents moved when he was a year old. His mother was one of the first members of the Haganah.

2. Yitzhak Rabin graduated with distinction in 1940 from an agricultural high school, with the goal of becoming an irrigation engineer.

3. In 1941 he joined the Palmach and saw service in the first half of that year in the allied invasion of Lebanon.

4. He continued in the Palmach, and after the war planned and executed the raid on the Atlith detention camp in October 1945. Two years later, he became Chief Operations Officer of the Palmach.

4. He continued in the Palmach, and after the war planned and executed the raid on the Atlith detention camp in October 1945. Two years later, he became Chief Operations Officer of the Palmach.

5. In 1948, he married Leah Schlossberg. In the war following Israel’s declaration of statehood, Rabin served as commander of the Harel Brigade and fought on the road to Jerusalem. He directed operations in Jerusalem and fought the Egyptians in the Negev. He was deputy commander of Operation Danny, involving four IDF brigades in capturing the cities of Ramle and Lydda. His duties were fraught with difficulty: he signed orders there for the expulsion of the Arab population.

6. In 1949, he move from warrior to peacemaker, taking part in the delegation to the armistice talks on Rhodes that led to the end of hostilities with the Arab nations.

7. By 1964, he’d become Chief of Staff of the IDF. The forces were under his command in the Six-Day War of 1967, and he was among the first to visit the Old City of Jerusalem after its capture.

8. In 1968 he was appointed ambassador to the United States, a position he held for five years.

9. He became Minister of Labor in March 1974 under Golda Meir and then Prime Minister in his own right in June of that year – the fifth prime minister of Israel, and the first to have been native-born. He was to serve from 1974 to 1977 and again from 1992 until his death in 1995. Operation Entebbe, the successful effort to rescue hijacked Israeli airline passengers, was carried out under his orders in the first year of his tenure. In the following years, he focused on improving the economy, solving social problems and strengthening the IDF.

10. He continued as a member of the Knesset on the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee and served as Minister of Defense 1984-90. Perhaps he is best known for his role in the 1993 Oslo Accords, setting up a framework for an Israeli-Palestinian peace process. In 1994, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, along with Yasser Arafat and Shimon Peres, “for their efforts to create peace in the Middle East.” In his acceptance speech he said, “Military cemeteries in every corner of the world are silent testimony to the failure of national leaders to sanctify human life.”

10. He continued as a member of the Knesset on the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee and served as Minister of Defense 1984-90. Perhaps he is best known for his role in the 1993 Oslo Accords, setting up a framework for an Israeli-Palestinian peace process. In 1994, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, along with Yasser Arafat and Shimon Peres, “for their efforts to create peace in the Middle East.” In his acceptance speech he said, “Military cemeteries in every corner of the world are silent testimony to the failure of national leaders to sanctify human life.”

11. He also oversaw the signing of the Israel-Jordan Treaty of Peace in 1994. But his signing of the Oslo Accords brought him calumny from right-wingers, and in 1995 he was assassinated by a young radical.

12. He was buried on Mt. Herzl, hundreds of world leaders attending his funeral. The Knesset set aside the 12th of Cheshvan in the Jewish calendar as his official memorial; but many Israelis follow the secular date of November 4th. In 1995, a commemorative stamp was issued in his memory. Ten years later, in 2005, he was voted number one in a poll of the greatest Israelis – a man of war who became a statesman working for peace.

“We, who have fought against you, the Palestinians – we say to you today, in a loud and clear voice: enough of blood and tears…enough!”

“We, who have fought against you, the Palestinians – we say to you today, in a loud and clear voice: enough of blood and tears…enough!”

Besides Rabin Square in Tel Aviv, you’ll find streets, neighborhoods, schools, bridges, and parks named for Rabin throughout Israel, as well as streets in Bonn, Berlin and New York and parks in Montreal, Paris, Rome and Lima.

December 4, 2013

10 Things You Need to Know About…HaRav Kook

Talmudist, leader, visionary, mystic, rabbi, peacemaker

1. Abraham Isaac Kook was born in 1865 in Griva, Courland, then part of the Russian Empire, now Latvia. The son of a student of the Volozhin Yeshiva, and the grandson, on his mother’s side, of a Chasid, he quickly became known as an outstanding student, a child prodigy. He was odd, though, in that he loved speaking Hebrew – a habit that was frowned upon in that place and time, Hebrew being the holy tongue. Yet at the same time, he prayed with unusual fervor, sensing the immediacy of the divine presence.

2. In 1887, at the age of 23, he became rabbi of Zimel (or Zaumel) in Lithuania, and in 1894 of Boisk (or Bausk). He wrote prodigiously, earning renown as a thinker, Torah scholar, Halachist and Kabbalist. What set him apart was his openness to new ideas alongside his orthodox beliefs. In his first essay on Zionism, published while he was in Boisk, he accepted Jewish nationalism – even at its most secular – as an expression of the divine will.

3. He didn’t have to go to Eretz Yisrael: in fact, he turned down tempting offers in Lithuania, and instead, in the summer of 1904, took up the position of rabbi for Jaffa and its surrounding agricultural settlements. He served not only the religiously observant, but reached out to all Jews.

4. In the summer of 1914, while traveling in Europe, he was caught in the outbreak of World War I. He spent two years in Switzerland before relocating to London, England, where he stayed until 1919.

5. After the war, he was appointed rabbi of the Ashkenazim in Jerusalem, and under the British mandate, the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi. In his mind, the establishment of a chief rabbinate was the first step toward re-establishing the Sandhedrin. He was not political; his philosophy was inclusive – he believed that Jews, working together, serving God, would bring about redemption.

6. In other words, he was a religious Zionist who welcomed those who did not follow orthodox Judaism. He believed the end of days was near, and bringing together all Jews was part of the divine plan that would introduce the Messianic era. His role, as he saw it, was to embrace, rather than reject: to build and maintain channels of communication between the various Jewish sectors – Zionist and non-Zionist, religious and secular.

7. In 1924, he founded the yeshiva knows as Merkaz HaRav. The language of instruction was Hebrew, a fresh concept in that day, and the curriculum included not just the Law, but also classics of philosophy and devotion. He thought of the yeshiva as a place where Jews from all over the world could come and learn.

8. He was a man of his time, and there is an undeniable element of Jewish chosenness in his writings. If you look at his photograph, you can see in his eyes the inner light that touched so many.

8. He was a man of his time, and there is an undeniable element of Jewish chosenness in his writings. If you look at his photograph, you can see in his eyes the inner light that touched so many.

“Deep in the heart of every Jew, in its purest and holiest recesses, there blazes the fire of Israel.”

9. It is said that when he died in 1935, over 20,000 mourners attended his funeral.

10. Moshav Kfar Haroeh, in central Israel, had been established and named for him in 1935. In 1937, Mossad HaRav Kook, a research foundation and publishing house was established in his name in Jerusalem. It has produced more than 2000 books.

Rav Kook House, once Kook’s apartment, is a museum located on Rav Kook Street in Jerusalem, between Nahalat Shira and Mea Shearim.

In Tel Aviv, HaRav Kook Street is located near the sea, just south of Kerem HaTemanim, crossing HaKoveshim.

November 26, 2013

10 Things You Need to Know About… Chaim Tchernowitz AKA HaRav Zair

Author and Talmudic scholar

1. Chaim Tchernowitz was born in 1871 in Sebesh, Vitebsk in the Russian Empire. He studied in Lithuania with Isaac Elhanan Spektor and was ordained in 1896.

2. He aimed to rejuvenate Jewish learning by combining traditional study with modern research. He opened a yeshiva in Odessa in 1897 and later transformed it into a rabbinical seminary (1907). He believed that study was the center of Jewish life, as opposed to prayer, and the house of study as opposed to the synagogue. The seminary was attended by such later luminaries as Hayyim Nachman Bialik [see my post of May 22, 2013] and Joseph Klausner.

3. In 1914, he earned a Ph.D. in Judaica from the University of Wuerzburg. After WWI, in 1923, he settled in the United States and taught Talmud at the Jewish Institute of Religion, started by Rabbi Stephen S. Wise in New York.

4. He started writing scholarly papers as early as 1898, when his first article appeared in HaShiloah. He wrote studies on the codes of law preceding Joseph Caro [see my post of October 2, 2013] and general articles on Talmud. His books were mainly methodological studies aimed at modernizing the teaching of Talmud. He wrote four volumes on the development of Halakhah from pre-Mosaic times until the Second Temple. Then he produced a further three volumes on post Talmudic thought through the medieval period.

4. He started writing scholarly papers as early as 1898, when his first article appeared in HaShiloah. He wrote studies on the codes of law preceding Joseph Caro [see my post of October 2, 2013] and general articles on Talmud. His books were mainly methodological studies aimed at modernizing the teaching of Talmud. He wrote four volumes on the development of Halakhah from pre-Mosaic times until the Second Temple. Then he produced a further three volumes on post Talmudic thought through the medieval period.

5. He thus authored a comprehensive history of Jewish law. In a less scholarly vein, he wrote articles in Hebrew and Yiddsh concerning Zionism and contemporary Jewish issues.

6. His pen name, HaRav Zair, means “the young rabbi.”

7. In 1940, he founded Bitzaron, a Hebrew monthly, which he edited until his death in 1949. Many of his essays of this period were later collected in book form. They included humorous autobiographical sketches, as well as articles on Mendele Mokher Seforim, Bialik, Ahad HaAm [see my post of April 24, 2013] and others.

7. In 1940, he founded Bitzaron, a Hebrew monthly, which he edited until his death in 1949. Many of his essays of this period were later collected in book form. They included humorous autobiographical sketches, as well as articles on Mendele Mokher Seforim, Bialik, Ahad HaAm [see my post of April 24, 2013] and others.

8. A good portion of his work remains in print today. In addition, an archive of his correspondence and other writings may be found at the American Jewish Archives in Cincinnati.

9. Among his friends was Albert Einstein (shown at left, with Tchernowitz on the right), who praised his work in making Torah accessible.

9. Among his friends was Albert Einstein (shown at left, with Tchernowitz on the right), who praised his work in making Torah accessible.

10. His granddaughter said of him, “The Bible is not abstract religious text. The human beings whose stories make it up are inseparable from its meaning….Rav Zair was full of stories.”

In Tel Aviv, the street named for HaRav Zair runs north from Bene Moshe, parallel to Weizmann.

November 20, 2013

12 Things You Need to Know About… Eli’ezer Kaplan

Zionist and fiscal wizard

1. Eliezer Kaplan was born in Minsk in 1891. He attended cheder and Russian high school, then went on to polytechnic university in Moscow, where he graduated in 1917 as a building engineer.

2. While in school, he joined the Socialist Zionist Party. He was one of the founders of the Youth of Zion – Renewal movement and a member of the Youth of Zion (Ze’irei Zion) central committee.

3. During World War I he was active in helping Jewish refugees. He was a member of the Ukrainian Jewish delegation to the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919.

4. He made aliyah in 1920. In Palestine, he was one of the initiators of the merger between Ze’irei Zion and HaPoel HaZair to become Hitachdut (haHichtachdut haOlamit), with a program of pioneering and labor socialism. He represented the organization at the London Zionist Conference of 1920, where he was elected to the Zionist Executive Committee and then sent to Berlin to head the Hitachdut world office.

5. In 1923, he returned to Palestine and joined the Office of Public Works of Histradut (note: not Hichtachdut). In 1925, he was elected to the Tel Aviv City Council, a position he held until 1933.

6. He joined the board of the Jewish Agency in 1933, serving as its treasurer until 1949 and head of its Settlement Department from 1943-48. As treasurer, he obtained the first foreign loan for the Jewish Agency from Barclays Bank in London. Other loans followed, and he introduced meticulous supervision over expenditures. It was his financial acumen that gave him an important role in the developing Jewish state.

6. He joined the board of the Jewish Agency in 1933, serving as its treasurer until 1949 and head of its Settlement Department from 1943-48. As treasurer, he obtained the first foreign loan for the Jewish Agency from Barclays Bank in London. Other loans followed, and he introduced meticulous supervision over expenditures. It was his financial acumen that gave him an important role in the developing Jewish state.

7. He was one of the founders of the Mapai party and a member of its central committee. Within Mapai, he was looked upon as a moderate. David Ben-Gurion was to say of him later, “He was not an easy man to work with,” but his opinions came from “deep and pure conviction.”

8. When the State of Israel was in its gestation, Kaplan was a member of the Assembly of Representatives, signing the Israeli Declaration of Independence on May 14, 1948. He was appointed Minister of Finance in the provisional government and elected to the first Knesset as a member of Mapai. In Ben-Gurion’s first government, he served as both Finance Minister and Minister of Trade and Industry.

9. Kaplan laid the foundation for the State of Israel’s fiscal policy, shaping its first budgets and its taxation structure. He headed the committee for establishment of a state bank, securing the bank’s independence. He was particularly interested in agricultural settlements and worked to strengthen their economic foundations. He published several books on the economy of Israel.

10. In 1949, he obtained the first loan for the State of Israel from the Import and Export Bank of the United States. Later, he contributed to organizing the sale of Israel Bonds in the United States.

11. In June 1959, he became the country’s first Deputy Prime Minister – but died three weeks later while on a trip to Genoa. Thousands upon thousands of immigrants lined the three-mile road into Tel Aviv when his body was returned to Israel, honoring the man whose stringent financial oversight made their aliyot possible.

12. All over Israel, his name is honored: the Kaplan Medical Center in Rehovot; Kiryat Eliezer, a suburb of Netanya; the Eliezer neighborhood of Kfar Saba; Kiryat Eliezer in Haifa; and the Eliezer Kaplan School of Politics and Social Sciences at Hebrew University.

In Tel Aviv, if you follow Dizengoff eastward, you will come to Kaplan after crossing Ibn Gevirol. In Jerusalem, Eli’ezer H. Kaplan Street fronts the Knesset, and is the site of many a protest.

Author’s note: OOOPS! This was scheduled for November 20. I don’t know why it didn’t post. Perhaps I forgot to push the “Publish” button. Anyway, lucky you, you get an extra post for Hanukah.

November 13, 2013

12 Things You Need to Know About… Beba Idelson

Zionist politician and women’s rights activist

Zionist politician and women’s rights activist

1. Beba Trachtenberg was born in October 1895 in Yekaterinoslav, in the Russian empire. Though the family was far from wealthy, the children were well educated. An older sister became a gynecologist. Beba was educated first by a private tutor, then in high school and university. When Beba was eight, her mother died in childbirth (thirteenth child). Her father died four years later. Beba helped raise her younger siblings, under the care of her grandmother.

2. In 1912, at the age of sixteen, she graduated from the Russian gymnasium and began studying economics and statistics at the University of Ukraine. At the time, she was an advocate of Russian – rather than Jewish – culture, but the Beilis blood libel trial in 1913 began bringing her to greater Jewish awareness. In 1915, as the Great War sent Jewish refugees from Austria across Ukraine’s western border, she volunteered in relief activities, joining an organization called Youth of Zion and meeting its leader, Israel Idelson.

3. The increasing unrest in Russia led her to involvement in Jewish self-defense training, as the Jewish students became more and more aligned with Zionist ideology. In 1917, she married Israel Idelson (later Bar-Yehudah), and their household became a magnet for Zionist activists. The couple moved to Kharkov in 1919. She continued her studies, he his Zionist work. In 1923 they were exiled to Siberia, but the horror of exile was replaced by deportation after timely intervention by Maxim Gorky’s wife.

4. They left the Soviet Union in 1924, spending two years in Berlin, where they were active in the World Union of Socialist Zionists. In April 1926 they reached Palestine. Israel was appointed secretary of the Workers’ Council in Petach Tikvah. At first she did agricultural work, but was then hired in 1927 as a statistician at the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem.

5. In 1928, Israel Idelson was appointed to the central comptrolling committee of the Executive Council of Histradut, the organization of trade unions. They moved to Tel Aviv.

6. It was in Tel Aviv, helping conduct a census of domestic workers, that Beba Idelson became aware of the wretched condition of women workers. She began working in the Tel Aviv Women’s Employment Bureau. She was one of the founders, and by 1930 became secretary, of the Organization of Working Women.

7. The Mo’ezet HaPoalot was the women’s section of Histradut. In the summer of 1931, she was asked to step in temporarily for its leaders in the secretariat. She became a permanent member of the secretariat and remained so until 1974, a tenure of nearly forty-five years. Lack of funds was a major obstacle to the development of the women’s movement, and she was good at handling money.

8. Here are some of her accomplishments: She organized the wives of Histradut and the Workers’ Movement to collaborate, got them membership cards and the right to participate in party elections. She was active in the Council of Women’s Organizations organized by Henrietta Szold [see my post of August 7, 2013] in the mid 1930s and, after the State of Israel was established, its chairwoman. She was a board member of Mishan, a Histradut institution supporting homes for orphans and the elderly; a board member of the Women’s International Zionist Organization for sixteen years; a Mapai delegate to the nineteenth Zionist Congress (1935); chair of Histradut’s ninth congress and a member of its central committee (1960s); and a member of the Flag and Emblem committee of the Provisional State Council, which chose the emblem of the State of Israel.

9. She believed in women’s economic independence and opposed any pressure on married women to resign from their jobs. Working through Histradut, she achieved a ban on dismissing women for this reason. She believed, as well, in women’s obligations to the state, advocating for conscription of women and supporting a national service law. In World War II, 3200 women served in the Women’s Auxiliary services of the British Army. She was one of the leading proponents for this volunteerism. Later, when the State of Israel was established, she became a member of the Knesset, working on the Constitution, Law and Justice, House, Foreign Affairs and Defense and Labor committees during her sixteen years of service. In all these functions, she continued to promote social reforms, particularly around women’s equality.

10. Her legislative activities affected the character of the new state, especially as regards the public status of women. Successful legislation she helped formulate included marital age (1951); women’s work (1953); national insurance, including insurance of mothers and pensions for widows (1953); inheritance law (1958); criminal law amendment (1959), equality law (1962). She tried, but was unable, to pass laws establishing civil, non-religious, matrimony and family courts.

11. In 1965, the year she left the Knesset, she was named Mother of the Year. She went on to chair the World Movement of Pioneer Women from 1968-75.

12. She died in January 1975 in Tel Aviv. Would you call her a late bloomer? If so, she didn’t she make up for lost time!

In Tel Aviv, Idelson Street crosses Pinsker and is west of Bialik.