Marilyn Oser's Blog, page 4

June 4, 2014

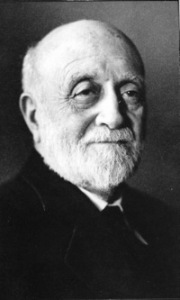

10 Things You Need to Know About… David Wolffsohn

Zionist leader

1. He was born in Kovno, Lithuania in 1856 to a financially struggling family. His father was a Talmudic scholar, and he had a traditional Jewish education.

2. In 1872, he was sent to East Prussia, where his brother lived, in order to avoid conscription in the Russian army. He continued his Jewish studies with Rabbi Isaac Ruif, also learning German and mathematics. Later, he met David Gordon, editor of HaMaggid. Both men influenced his commitment to Jewish nationhood, which had begun with his father.

3. After a number of failed business attempts, Wolffsohn became successful in the timber trade and settled in Cologne. In 1894, with Zionist Max Bodenheimer, he founded the Association for the Development of Agriculture in Israel, a German branch of Hovevei Zion.

4. In 1896, having read and been transfixed by Herzl’s Der Judenstaat, Wolffsohn sought out Herzl in Vienna. They soon became fast friends. Wolffsohn was a loyal friend and a diplomatic one, standing by Herzl even when he disagreed with him. With his unassuming nature, he mediated between the political and the practical Zionists (explained below), and he stood by Herzl in the Uganda crisis while generally soothing ruffled feathers. The character of David Littwak in Herzl’s Altneuland is said to be based on Wolffsohn.

“Ever since I learned to think and feel, I was a Zionist.”

5. As the moving spirit behind, and first president of, The Jewish Colonial Trust, Wolffsohn ensured its solvency. He became the director of all the financial and economic institutions of the Zionist movement, serving in this capacity until his death.

6. In 1898, he accompanied Herzl to London, Constantinople and Palestine. He was present during the audience with Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II, taking photographs that unfortunately did not come out (haven’t we all, at some important moment?).

7. When Herzl suggested seven gold stars on a white background for the Jewish national flag, Wolffsohn lifted his tallit and said, in effect, why re-invent the wheel? We have our flag right here. Thus was conceived the banner with a white field, two blue stripes near the margins, and a six-pointed Star of David in the center. Wolffsohn also introduced the shekel for the payment of Zionist members’ dues.

8. In 1907, after Herzl’s death, Wolffsohn was appointed leader of the World Zionist Organization, its second president. He took a typically moderate stance on the issues roiling up between the practical and political Zionists, all the while maintaining that all WZO programs were being carried out according to Herzl’s plans. The main issue between the political and practical Zionists was this: the political Zionists remained faithful to Herzl’s view that a charter of some kind was necessary prior to organized settlement in Palestine, while the practical Zionists (many of them from Russia, where conditions for Jews were dire) emphasized immediate local activity in Palestine.

9. Wolffsohn carried on with political efforts while allowing practical colonization. Under his watch, an office was opened in Jaffa to foster agricultural settlement; a JNF loan was granted to the founders of Ahuzat Bayit, the settlement that was to become Tel Aviv; the WZO’s official newspaper, HaOlam, was founded; and Wolffsohn traveled widely – to South Africa, Turkey, Russia, Hungary – in furtherance of Zionist efforts.

10. In failing health, he resigned leadership of the WZO in 1911, though he continued as financial director until his death in Hamburg in 1914. His estate provided the means for the National and University Library to be built in Jerusalem. In 1952, his remains were brought to Israel and buried on Mount Herzl.

In Tel Aviv, you’ll find Wolffsohn Street just west of the Central Bus Station.

May 28, 2014

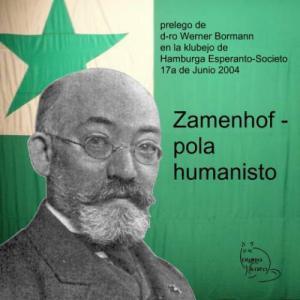

10 Things You Need to Know About… L. L. Zamenhof

Creator of Esperanto

“I was taught that all men were brothers, and meanwhile, in the street, in the square, everything at every step made me feel that men did not exist, only Russians, Poles, Germans, Jews, and so on.”

“I was taught that all men were brothers, and meanwhile, in the street, in the square, everything at every step made me feel that men did not exist, only Russians, Poles, Germans, Jews, and so on.”

1. Eliezer Zamenhof (also called Leyzer Levi Zamenhov and Ludwig Lazar Zamenhof) was born in December 1859 in Bialystok. His father was a teacher of German. He grew up speaking Russian, Polish and Yiddish and later learned French, Latin, Greek, Hebrew and English.

2. As a young man, he conceived the notion that ethnic and national hatreds had a linguistic basis, and that understanding among peoples could be achieved if they had a common, neutral communication tool. He began developing that tool while he was still in high school.

3. He studied medicine in Moscow and Warsaw and in 1886 established a practice as an ophthalmologist. But he had not forgotten his goal of promulgating an international language and spent the better part of two years trying to raise funds to publish a forty-page booklet describing his “lingvo internacia.”

4. Finally, with the help of his father-in-law, his International Language was published in Russian under the pseudonym “Dr. Esperanto,” which, in his constructed language, meant Doctor Hopeful.

5. The first magazine in what came to be called Esperanto came out in Germany in 1889. A formal organization was formed in the 1890s, and the first international congress was held in Boulogne in 1905. It was not a ringing success, as the French Esperantists were put off by Zamenhof’s religious enthusiasm (see below). In 1908, the Universal Esperanto Association was founded in Rotterdam.

6. Zamenhof continued to write dictionaries, texts and translations in Esperanto, including the Old Testament. Some of his works can be found today at Project Gutenberg (www.gutenberg.org).

7. His linguistic efforts extended to Yiddish. In 1879 he wrote the first grammar of the Yiddish language, later translating it into Russia and Esperanto.

8. After the Russian pogroms of 1882, Zamenhof joined the early Zionist movement, but left it only five years later. In 1901, in an essay on what he called Hillelism, he argued against nationalism of any sort. He wanted Judaism reconstructed on an ethical basis, advocating for people of all religions to reject national, racial and religious chauvinism. Jews, he argued, should give up Hebrew, which was “cadaverous,” and Yiddish, which was “a jargon;” instead, they should adopt Esperanto and practice a theosophical faith based on cultural Judaism. In 1906, the name Hillelism was changed to Homaranismo (Humanitarianism), which he described as a “philosophically pure” monotheism, a universal ethical order.

8. After the Russian pogroms of 1882, Zamenhof joined the early Zionist movement, but left it only five years later. In 1901, in an essay on what he called Hillelism, he argued against nationalism of any sort. He wanted Judaism reconstructed on an ethical basis, advocating for people of all religions to reject national, racial and religious chauvinism. Jews, he argued, should give up Hebrew, which was “cadaverous,” and Yiddish, which was “a jargon;” instead, they should adopt Esperanto and practice a theosophical faith based on cultural Judaism. In 1906, the name Hillelism was changed to Homaranismo (Humanitarianism), which he described as a “philosophically pure” monotheism, a universal ethical order.

9. He died in Warsaw in April 1917 and is buried there in the Jewish Cemetery at Okopowa Street. Hundreds of streets, parks and bridges worldwide have been named in his memory – in Lithuania, England, France, Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, Spain, Italy, Belgium and Brazil. There is a Zamenhof Island in the Danube River and a minor planet, Zamenhof 1462, among the stars. A genus of lichen has been named for him. And he is honored as a deity by the followers of Oomoto, a Shinto sect.

10. Esperanto is still in use today by an estimated minimum of 100,000 people, and perhaps as many as two million. It has its own flag, and its online learning platform receives upwards of 200,00 hits a month. If you noodle around online, you will find jokes in Esperanto, tongue-twisters in Esperanto….

In Tel Aviv, you’ll find Zamenhof Street running east off Kikkar Zina and crossing King George Street.

In Tel Aviv, you’ll find Zamenhof Street running east off Kikkar Zina and crossing King George Street.

May 21, 2014

10 Things You Need to Know About… Shimon bar Kokhba

The warrior we remember on Lag B’Omer

1. Shimon bar Kokhba led a Jewish revolt against the Roman Empire in the years 132-135 CE.

2. Let’s start with his name. We know his first name, Shimon, from coins minted at the time of the revolt. Likely, his surname was initially Bar Koseva. It is thought that this was changed, perhaps by Rabbi Akiva, to bar Kokhba at the time of the revolt. Messianic hopes were high then, and it was said he descended, as was required by Jewish tradition, from the Davidic line. The reconfigured name read “son of a star,” a reference to the prophecy in Numbers 24:17, “there shall step forth a star out of Jacob, and a scepter shall rise out of Israel, and shall smite through the corners of Moab.” Later, when the revolt went down to stupendous failure, he was called bar Koziba, meaning “son of disappointment.” Each change required the substitution of just one letter.

2. Let’s start with his name. We know his first name, Shimon, from coins minted at the time of the revolt. Likely, his surname was initially Bar Koseva. It is thought that this was changed, perhaps by Rabbi Akiva, to bar Kokhba at the time of the revolt. Messianic hopes were high then, and it was said he descended, as was required by Jewish tradition, from the Davidic line. The reconfigured name read “son of a star,” a reference to the prophecy in Numbers 24:17, “there shall step forth a star out of Jacob, and a scepter shall rise out of Israel, and shall smite through the corners of Moab.” Later, when the revolt went down to stupendous failure, he was called bar Koziba, meaning “son of disappointment.” Each change required the substitution of just one letter.

3. For three years he led the revolt as warrior and as executive (Nasi, or prince) of an independent Jewish state. As a leader he was strict and punctilious. It is said that he required his soldiers to cut of a finger as a kind of initiation rite. When he went into battle, he is said to have asked God for neither assistance nor discouragement, saying, “There is no need for You to assist us, but do not embarrass us either.” Letters written in his name during the war show not only his focus on the smallest issues of camp life, but also on issues relating to Jewish observance, including Shabbat, tithes and holidays. Archaeologist Yigael Yadin says that he also tried to revive Hebrew (Aramaic was the language spoken at that time) as the official language of his realm.

4. The rebellion broke out when the emperor Hadrian, who had initially been somewhat welcoming to the Jews, took increasingly hard measures against them, appointing rulers who ravaged the population, interdicting religious practices such as circumcision, and starting to build a temple to Jupiter on the site of the destroyed Temple.

5. At first, success was rapid. Bar Kokhba’s forces, including Jews and non-Jews, overran some fifty strongholds in Judea and 985 undefended towns and villages. Hadrian sent stronger troops to fight the insurgents, and the Jews defeated them, too. Coins were minted with Bar Kokhba’s name and slogans such as “the freedom of Israel.”

6. More Roman legions were dispatched to Judea, and rather than waging open war, they set siege to the Jewish fortresses and villages, utilizing a scorched-earth policy that weakened the bodies and the will of the inhabitants. The tide of war turned, yet the Romans continued to take heavy casualties, too.

7. Bar Kokhba’s headquarters in Bethar also housed the Sanhedrin. It was the vital center of the nation and a military stronghold strategically located on a mountain ridge overlooking the road to Jerusalem. Here, after a bitter siege, the final battle was fought. When the Romans conquered the stronghold, they killed every Jew there, sparing just one youth, Simeon ben Gamliel.

8. It was reported by the Roman consul and historian Cassius Dio (135-236 CE) that 580,000 Jews were killed in the war, not counting those who died of famine, disease and fire. More were sold into slavery. The Romans plowed Jerusalem with a yoke of oxen, then built on its site the city of Aelia Capitolina, where Jews were not permitted. Judea, Galilee and Samaria were reconstituted as a single province, Syria Palaestina. Persecution of the Jews, and prohibition of religious practices, continued at an even higher pitch until the end of Hadrian’s reign in 138 CE.

9. Bar Kokhba has been the subject of some twenty works of music and literature over the last century and a half, in Hebrew, Yiddish, English, French, Hungarian and Danish.

10. Why Lag B’Omer? In modern times, Zionism connected Bar Kokhba with heroism in the face of overwhelming odds, and today in Israel the holiday continues to symbolize the Jewish fighting spirit.

May 14, 2014

10 Things You Need to Know About… Eliyahu Golomb

Chief architect of the Haganah

1. He was born in March 1893 in Volkovysk, Byellorussia. When he was sixteen, his family made aliyah. He graduated with the first class of Herzliyah High School.

2. He went to settle in Kibbutz Degania Aleph, working there and organizing agricultural training courses. But upon the death of his father, he returned to run the family flour mill in Jaffa. When World War I came, he was ordered by the Turks to operate the flour mill on Shabbat. He refused, and was publicly whipped for it.

4. He opposed Jewish enlistment in the Turkish Army. When, late in the war, the British permitted formation of a Jewish Legion, he headed up the volunteers for it.

5. He was active in the labor party Ahdut Ha-Avodah, but he is best known for his work in creating a Jewish military presence. Golomb believed that all Jews must be involved in their own defense. After the war, he was active in founding and organizing the Haganah. He served on its command council and in 1920 was involved in sending aid to the defenders of Tel Hai.

5. He was active in the labor party Ahdut Ha-Avodah, but he is best known for his work in creating a Jewish military presence. Golomb believed that all Jews must be involved in their own defense. After the war, he was active in founding and organizing the Haganah. He served on its command council and in 1920 was involved in sending aid to the defenders of Tel Hai.

6. From 1922-24, he was abroad – Vienna, Berlin, Paris – purchasing arms for the Haganah and organizing pioneer youth groups.

7. Through the 1930s, Golomb largely directed the organization and financing of illegal immigration of Jews to Palestine. During the riots of 1936-9, he was one of the initiators of the field units that confronted Arab terrorists. He supported defense against Arab attacks, but not indiscriminate attacks on Arab populations. These punitive actions he opposed.

8. Like most of his compatriots, he supported the British in World War II without ever forgetting the need to remove the mandate. He was a founder of the Palmach – the elite unit of the Haganah – and trained many future commanders of the IDF.

9. He authored “The History of Jewish Self-Defence in Palestine, 1878-1921,” a pamphlet that is currently (May 2014) up for bid at Delcampe.net.

10. He died in June 1945. His home on Rothschild Street in Tel Aviv, where the command council typically met, is now Beit Eliyahu Golomb, the museum of the Haganah. His apartments have been restored, and the museum is adjacent.

10. He died in June 1945. His home on Rothschild Street in Tel Aviv, where the command council typically met, is now Beit Eliyahu Golomb, the museum of the Haganah. His apartments have been restored, and the museum is adjacent.

In Haifa, you’ll find Eliyahu Golomb Street running southeastward from the Bahai Shrine.

May 7, 2014

Several Things You Need to Know About… Shaul Pinchas Rabinovitch and David Bloch

Two Ardent Zionists

1. Shaul Pinchas Rabinovitch, known as SheFeR, was born in Lithuania in 1845. He became a Zionist, one of the leading forces in Hovevei Zion in the Russian Empire.

2. He was active in Hebrew publication, writing for such newspapers as HaMagid and HaTsefira.

3. He published a collective work, Knesset Yisroel – the Gathering of Israel.

4. He translated Graetz’s history of the Jews [see my blog post of July 13, 2013] into Hebrew, making significant changes to remove anything that shed a poor light on Israel.

5. He died in Frankfurt in 1910.

David Bloch visiting Detroit

6. David Bloch (also known as David Bloch-Blumenfeld) was born Efraim Blumenfeld in Grodno in 1884. He was active in Poalei Zion, helping establish labor offices and workers’ settlements.

7. He was a distinguished part of the second aliyah, a founding member of both Ahdut HaAvodah (1919) and Histradut (1920).

8. In 1923, he became Deputy Mayor of Tel Aviv; he served as the city’s mayor from 1925-7.

9. He died in 1947. Moshav Dovev in the upper Galilee was named for him (1963).

In Tel Aviv, you’ll find Shefer Street in Neve Tzedek running eastward from HaKarmel just north of Kalischer. Further north, you’ll find Bloch running northeastward from Ben Gurion to Arlosoroff.

April 29, 2014

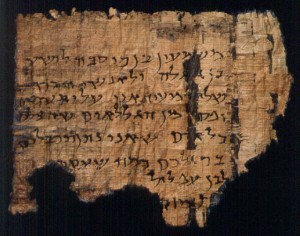

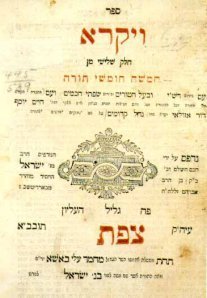

8 Things You Need to Know About…Yisrael Bak

Pioneering Hebrew printer

1. Israel Bak was born in 1797 in Berdichev, Ukraine, where he became a printer and published close to thirty Hebrew books.

2. In 1831, he made aliyah, settling in Safed his family, two printing presses and tools for casting letters and for bookbinding.

3. No Hebrew book had been printed in Eretz Yisrael for 245 years. In 1832, Bak printed a Sephardi prayerbook, reviving a moribund industry. The next year, he published the Book of Leviticus, the first book of the Pentateuch ever to come from a printing press in Eretz Yisrael.

3. No Hebrew book had been printed in Eretz Yisrael for 245 years. In 1832, Bak printed a Sephardi prayerbook, reviving a moribund industry. The next year, he published the Book of Leviticus, the first book of the Pentateuch ever to come from a printing press in Eretz Yisrael.

4. After a peasant revolt in 1834 that destroyed his press and injured him, he began farming land on Mount Yarmak, overlooking Safed. His was the first Jewish farm in modern times.

5. He continued publishing, as well, the press employing 30 people at its height. But ill fortune continued to plague the people of Safed – an earthquake in 1837 and a Druze revolt in 1838. Again, his press was destroyed. In 1841, he moved to Jerusalem and established himself there, the first Hebrew press in Jerusalem. He continued printing books, some 130 in all, for 33 years.

6. He was a close correspondent of Moses Montefiore, who gave him a new press for his shop in Jerusalem.

7. In 1863, he founded the newspaper Havazzelet, but this venture was closed down by the Ottoman government after only five issues. After his death it was revived by his son-in-law and, though continually troubled, became an important organ for the Chasidic community.

8. With his son Nisan, he was a major force in establishing a central synagogue in Jerusalem for Chasidim. He died in 1874.

In Tel Aviv, you’ll find Yisrael Bak Street near the Ayalon River at Shekhunat Montefiore.

April 23, 2014

8 Things You Need to Know About…David Yellin

Advocate for the Hebrew language

1. David Yellin was born in Jerusalem in March 1864. He was educated at the Etz Hayim Yeshiva there, but in 1882 enrolled in the Alliance Israelite Universelle. At age eighteen he became a teacher, and eventually he headed the Lamael School.

2. In 1903, he was one of the organizers and also first president of the Teachers Association.

3. In 1913, Yellin resigned his position as director of the Lamael School over the issue of using German as the dominant language. He was a firm advocate for Hebrew.

3. In 1913, Yellin resigned his position as director of the Lamael School over the issue of using German as the dominant language. He was a firm advocate for Hebrew.

4. He founded a Hebrew teachers’ seminary at Beth Hakerem, where he served as director until his death. The David Yellin College of Education still exists today.

5. He helped establish the nucleus of the Jewish National Library, now housed at Hebrew University.

6. He served in many political capacities, including the Jerusalem Municipal Council, Deputy Mayor of Jerusalem and president of the Jewish National Council.

7. A member of the Ottoman parliament, he joined the Zionist movement (1913), one of the first public figures to do so openly. During World War I, he was exiled to Damascus by the Ottomans. While in exile, he served with the American Palestine Relief Committee. When the war ended, he was a member of the Jewish Committee to the Paris Peace Conference.

8. David Yellin died in Jerusalem in December, 1941.

In Tel Aviv, you’ll find David Yellin Street just north of Jabotinsky and west of Kikkar HaMedina. In Jerusalem, look for him in Mahane Yehuda north of Kikkar HaHerut.

April 16, 2014

Watch for a new post next week. Zissen Pesach to all.

April 9, 2014

10 Things You Need to Know About… Moshe Sharett

Second Prime Minister of Israel

1. He was born Moshe Shertok in October 1884 in Kherson, Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire. In 1906, he made aliyah with his family, living first in an Arab village, thus learning Arabic and becoming familiar with Arab customs.

2. In 1910, his family were among the founders of Tel Aviv. He was in the very first class to graduate from Herzliya High School. He went on to study law at Istanbul University, but his academic career was cut short by the advent of World War I. Fluent in Arabic, Turkish and German (and ultimately five other languages), he served as an interpreter in the Ottoman Army.

3. After the war, he became an agent for the Yishuv, working in Arab affairs and land purchase. He joined the labor party Ahdut Ha’Avoda and later Mapai. Between 1922-24 he attended the London School of Economics, where he was active in Poalei Zion. He edited their periodical Workers of Zion and later worked on Davar, Histradut’s daily newspaper, editing its English language weekly from 1925-31.

3. After the war, he became an agent for the Yishuv, working in Arab affairs and land purchase. He joined the labor party Ahdut Ha’Avoda and later Mapai. Between 1922-24 he attended the London School of Economics, where he was active in Poalei Zion. He edited their periodical Workers of Zion and later worked on Davar, Histradut’s daily newspaper, editing its English language weekly from 1925-31.

4. Upon returning to Palestine after his studies in England, he became secretary of the political division of the Jewish Agency. After the assassination of Arlosoroff in 1933 [see my post of May 8, 2013], he became head of the division, a position he was to hold until 1948.

5. He was the key negotiator with the British Mandatory during the critical time of the thirties and forties. In 1944, he was instrumental in establishing the Jewish Brigade, doing all he could to encourage Jewish volunteers.

6. In 1947, Sharett appeared before the United Nations General Assembly with regard to the partition of Palestine. He worked tirelessly to mobilize international support for the plan and was one of the signatories to the Israeli Declaration of Independence.

7. During the 1948 War of Independence he served as Foreign Minister for the provisional government. He led the Israeli delegation to the cease-fire negotiations during and after the War of Independence. He was elected to the Knesset in the first Israeli election (1949) and served as Minister of Foreign Affairs until 1956, establishing the diplomatic service and embassies, forging diplomatic ties with many nations and helping to bring about Israel’s admission to the United Nations. In 1952, he signed a reparations agreement with West Germany.

8. Sharett was eager to stabilize relations with the Arab nations and opposed any use of harsh tactics against border incursions [cf. my post of March 19, 2014]. In this, he came into conflict with his old friend and colleague, David Ben-Gurion. In December 1953, when Ben-Gurion retired from politics – though only temporarily, as it turned out – Sharett became Prime Minister and held the position for two years. During his tenure, a scandal arose (the Lavon Affair) over a covert operation in Egypt run (poorly) by the IDF; Sharett, unaware of it, publicly denied the espionage. This and his disagreements with Ben-Gurion caused his political downfall and retirement.

8. Sharett was eager to stabilize relations with the Arab nations and opposed any use of harsh tactics against border incursions [cf. my post of March 19, 2014]. In this, he came into conflict with his old friend and colleague, David Ben-Gurion. In December 1953, when Ben-Gurion retired from politics – though only temporarily, as it turned out – Sharett became Prime Minister and held the position for two years. During his tenure, a scandal arose (the Lavon Affair) over a covert operation in Egypt run (poorly) by the IDF; Sharett, unaware of it, publicly denied the espionage. This and his disagreements with Ben-Gurion caused his political downfall and retirement.

9. In retirement, he became Chairman of Am Oved publishing house and of Beit Berl College, both Histradut institutions. He represented the Labor Party at the Socialist International. In 1960, he became Chairman of the World Zionist Organization and the Jewish Agency. He died in Jerusalem in 1965 and is buried in Trumpeldor Cemetery in Tel Aviv. In the Ynet 2005 poll, he was voted 150th on the list of 200 greatest Israelis.

10. The Prime Minister’s Office lists several books written by Sharett, though I have been unable to verify this information elsewhere: Oar in Asia (1957), At the Time of Nations (1958), Booklet of Poetry Translations (1965) and Fading lights (196-). It is certain, however, that after his father’s death, Sharett’s son published Sharett’s diaries, making an important contribution to historical scholarship. A new edition of the diaries came out in 2007, with passages that had been left out of the earlier editions.

10. The Prime Minister’s Office lists several books written by Sharett, though I have been unable to verify this information elsewhere: Oar in Asia (1957), At the Time of Nations (1958), Booklet of Poetry Translations (1965) and Fading lights (196-). It is certain, however, that after his father’s death, Sharett’s son published Sharett’s diaries, making an important contribution to historical scholarship. A new edition of the diaries came out in 2007, with passages that had been left out of the earlier editions.

In Tel Aviv, Sharett Street circles around HaMedina Square, intersecting with Arlosoroff, Jabotinsky and Weizmann, among others.

April 2, 2014

8 Things You Need to Know About… Micah Joseph Berdichevsky

Journalist and scholar

1. He was born Micha Yosef Berdichevsky, August 1865, in the Ukraine and into a family of Chasidic rabbis. His father was the rabbi in a town of impoverished Jews. He was to grow up to speak for a generation that was trying to navigate the rocky straits between traditionalism and modernism.

2. An early prodigy in Talmud, he began reading mystical writings and other materials that brought him into conflict with his teachers. He was married while still in his teens to the daughter of a wealthy, pious merchant. But when his father-in-law discovered that he’d been reading works of the Haskalah (Jewish enlightenment), Berdichevsky was forced to divorce his wife.

3. He ran away to Volozhin, to the yeshiva there, but again ran into difficulty because of his unorthodox reading. He was nineteen. A few years later, he published an article about these difficulties in the Hebrew language newspaper Hamelitz. The impassioned language he used – expressive of the conflict within him between tradition and assimilation – was to become a hallmark of his writing.

3. He ran away to Volozhin, to the yeshiva there, but again ran into difficulty because of his unorthodox reading. He was nineteen. A few years later, he published an article about these difficulties in the Hebrew language newspaper Hamelitz. The impassioned language he used – expressive of the conflict within him between tradition and assimilation – was to become a hallmark of his writing.

4. In 1890 he went to study in Germany and Switzerland, studying philosophy, notably the works of German philosophers, and earning a doctoral degree. His thought was deeply influenced by the works of Nietzsche and, to a lesser extent, Hegel. These were years of enormous productivity: between 1890 and 1900, Berdichevsky published ten books as well as articles and stories in Hebrew journals.

5. In 1900 he married and returned to his home in the Ukraine, where he was struck by the deterioration of traditional ways of life under the harsh conditions there. He returned to Germany in 1911 and lived there the rest of his life. The outpouring of stories, essays and novels continued, expressing always the ambivalence he felt between the wish to preserve Jewish tradition and the wish to live according to secular European culture. His aim, he said, was to repair the rent in the heart of the Jewish nation, making it possible to be both a Jew and a man in the modern world.

6. Berdichevsky’s essays included literary criticism and polemics against what he considered the dead weight of Jewish tradition, which he thought emphasized history over life. He spoke for a “rebellion of historically suppressed individualism.” Jews, he thought, had been detached from nature and physicality, their culture ossifying in exile. He hearkened back to ancient Israel – a time of political sovereignty and physical heroism – as a model; and he argued for a Hebrew literature that would become a means for Jews to retain their cultural and spiritual coherence while embracing the phenomena of modern life.

7. His fiction portrayed the difficulty of navigating a break from the immediate past while still continuing Jewish tradition. The characters in nearly all of his stories are either attempting to escape the weight of tradition or to survive within it, both with equally futile results.

8. In 1914, he began using the name Micha Yosef Bin-Gurion and continued to do so until his death in Berlin in 1921. In these later years, he devoted himself to collecting Jewish legends, myths and folktales, which he rewrote in a modern idiom, using a sparse, lyrical Hebrew, a kind of old-new tongue. This remarkable collection is perhaps, in the long run, his greatest contribution to Jewish literature.

“It is upon us to choose in ourselves that which is good and beautiful, that which is righteous and lasting. Free men are turned into slaves if they close the path before themselves, if we open our windows – freedom arrives from the distance.”

“It is upon us to choose in ourselves that which is good and beautiful, that which is righteous and lasting. Free men are turned into slaves if they close the path before themselves, if we open our windows – freedom arrives from the distance.”

In Tel Aviv, you’ll find Berdischevsky Street running eastward off the northern end of Rothschild Blvd., between Marmorek and Cremieux.

The moshav Sdot Micha, founded in 1955, was named for him, as well. It is located in central Israel near Beit Shemesh.