Aaron Gustafson's Blog, page 10

October 31, 2017

Web Form Conundrum: `disabled` or `readonly`?

Web forms are complex beasts. There are a lot of field types to remember, each with dozens of attributes. It���s hard to know which is the right way to go, especially when presented with a choice between two seemingly similar options for disallowing a field to be edited: disabled and readonly.

TL;DR: If you really need it, which you probably don���t, readonly is what you want.

The Use Case

There are times when you want to expose a bit of data to the user but don���t want them to be able to edit it. For example, your system might not allow a user to edit their username after completing the registration process. In situations like this, you may want to present the username in the context of a profile editing interface without allowing them to edit it.

The best choice in that situation would be to avoid using a form field to display the username, full stop, but if you���re hamstrung and need to drop it in an input field, you want to make sure the user can���t edit it. That���s when you need to make a choice between disabled and readonly.

Both of these attributes are ���empty��� attributes, meaning they don���t require value assignment:

<label for="username-1">Disabled Username</label>

<input id="username-1" name="username-1" disabled value="AaronGustafson">

<label for="username-2">Readonly Username</label>

<input id="username-2" name="username-2" readonly value="AaronGustafson">

view raw

disabled-readonly.html

hosted with ❤ by GitHub

As expected, both also prohibit editing directly in the browser.

The Key Difference

So why do we have two attributes that do the same thing? Unfortunately this is where developers often get confused: the user experience is the same, but the mechanics are quite different.

Fields marked as readonly are collected along with all of the normal field values in a form submission (���successful controls��� in the spec). The only difference between a readonly field and a regular field is the user experience.

Fields marked as disabled are ignored when collecting values from the form. In a traditional form submission, the action page would never receive values for a disabled field, regardless of whether it has a name attribute. In JavaScript, this is a little trickier as generic DOM access via a form���s elements collection includes all form controls, including disabled fields (and buttons, output elements, etc.). In order to ensure consistency with the spec, it is incumbent upon the JavaScript developer to keep an eye out for disabled fields so they can throw away their values before processing the form.

See the Pen jaPYLr by Aaron Gustafson (aarongustafson) on CodePen.

Thankfully, most library code I���ve found does this, so it���s not much of an issue if you are working with jQuery���s serialize() method or even the form-serialize module for Node (and React, etc.). Confusingly, the Node module enables developers to treat disabled fields as though they are readonly. Luckily, that���s not the default behavior.

Don���t Assume

In many of my forms-related talks, I���ve discussed the need for server side validation of info sent from the browser. Even if you have the most robust client-side validation logic in the world, that JavaScript (and your HTML, etc.) is all easily manipulated via common developer tools. If you don���t have equally robust checks running on the server side (be it via an API or simply a form-posting endpoint), you���re opening your system up for abuse.

It���s inconsequential to inspect a form field in the browser, remove the readonly or disabled attribute, and submit the form with a change to that field. If you, as the developer, truly don���t want the value of a particular key touched, don���t provide it in a field to begin with. Additionally, don���t accept any values submitted for it. You don���t need to throw an error to the user since it���s an improper use of the system, but you might consider logging it in case you see continued abuse by that user.

I Have Forms to Build, Which Do I Choose?

I want to display data as information, but don���t want a user to update it.

Don���t use a form field at all, display it as text.

I want the data included with the form submission.

Ideally, display the info as text (see above) and mix it into the form submission data on the server side. If that���s not possible, make it a readonly field an ensure there���s a validation check on the server side.

I do not want the data included in the form submission.

Display the info as text (see above).

September 18, 2017

A Different Kind of Intolerance

Nearly two decades ago, Kelly unravelled the mystery of my digestive tract that had eluded me for a number of years. It had become commonplace for me to get an upset stomach after eating. I didn���t think much of it really, but Kelly noticed a pattern: it only happened after meals that involved milk of some kind. ���I bet you���re lactose intolerant.��� Turns out she was right. Kind of.

Being an avid dairy fan, I quickly reached for the helping hand of big pharma to enable my addiction. Lactaid seemed to work on occasion, but not consistently. Then I discovered Digestive Advantage ���Lactose Defense Formula��� which seemed to work a bit better, but I hated having to take the pills all the time. So I stopped and just tried to avoid dairy as much as possible. As Jeremy can attest, it made trips to places like Wisconsin rather difficult.

Every now and then, I���d ���splurge��� (a.k.a., do something I���d later regret) and have a special cheese or a gelato. The weird thing I noticed was that sometimes I would have an issue, other times I���d be totally fine. Coming from a scientific background, I decided to begin experimenting in an effort to suss out the source of my digestive discomfort.

Along the way, I discovered that I had no issues with goat and sheep milk cheeses1. I also found that I only occasionally had issues with cow milk-based cheeses in Europe. But why?

At first I thought that maybe non-cow milks didn���t have lactose, but that���s not the case. At least according to Wikipedia, both sheep milks even contain more lactose. So lactose intolerance apparently wasn���t my problem. I was perplexed.

I continued digging and stumbled on a website about a doctor who���d been researching proteins in milk. The site I found it on looked like a straight-up conspiracy site,2 so I took what it said with a grain of salt, but the gist was this: When we domesticated cows around 10,000 years ago, they produced only the protein A2 beta-casein. Around 8,000 years ago, a genetic mutation occurred that caused some cattle to produce A1 beta-casein.

A1 beta-casein producing cows are pretty much all we have now in the United States, New Zealand, Australia, and Europe (except parts of Southern Europe). The reason seems to be that A1 beta-casein producing cows were milder mannered and easier to work with. They became the preference in most industrial farms. There are a few books out there about it if you���re interested. The Devil in the Milk seems to be particularly well-reviewed and draws connections between A1 milk and heart disease, Type 1 diabetes, autism, and schizophrenia.

I hadn���t really thought about it for a while, but the other day happened to see A2 brand milk in my grocery store the other day and decided to give it a try. Two bowls of delicious cereal later and I���m convinced that I���m actually allergic to A1 beta-casein. Not that it helps me order in restaurants. I���m sure some server would think I was straight out of Portlandia if I asked them if their milk was A1 or A2.

Anyway, if you think you���re lactose intolerant, you might want to run a little experiment of your own to determine if you���re actually lactose intolerant or if you���re really allergic to A1 beta-casein.

A fact that I was quite happy to discover. Goat cheeses are among some of the best I���ve ever had. Two recommendations: Cocoa Cardona from Carr Valley and Sn��frisk Firm Goat���s Cheese.��↩

Alas I can���t find the link any longer.��↩

August 28, 2017

Categories land in the Web App Manifest

Starting in early May, Rob Dolin began advocating for adding a categories member to the Web App Manifest spec. It was something we���d been discussing for a while now. It���s a feature that will be incredibly useful to users, especially as it relates to PWAs in the Windows Store, other app stores, and in catalogs. This weekend, our hard work paid off and it was added to the spec!

So what does it do and how do I use it?

First off, the new categories member is totally optional. It���s there if you think it offers a benefit for your users, but is by no means necessary.

According to the spec:

The categories member is only meant as a hint to catalogs or stores listing web applications and it is expected that these will make a best effort to find appropriate categories (or category) under which to list the web application. Like search engines and meta keywords, catalogs and stores are not required to honor this hint.

The categories member is a list of categorizations you want to apply to your site. There are no pre-defined categories, but the W3C is maintaining a list of common categories shared by most app stores and catalogs. You will probably want to use at least one of those to ensure your site gets filed properly.

Here���s quick example of a hypothetical manifest for a web version of the book Gojiro by Mark Jacobson:

{

"name": "Gojiro",

"description": "Gojiro, a freak mutation with a cynical worldview, suffers the pain of solitude as well as several maladies experienced by entertainers, including drug abuse and suicidal tendencies.",

"icons": [{

"src": "images/icon.png",

"sizes": "192x192"

}],

"category": ["books", "fiction", "science fiction & fantasy", "kaiju", "������"]

}

Here you can see 5 categories being assigned to the book. I chose to start with one of the top-level categories from the list and then get more specific, kinda like how class names were originally conceived. The genre ���Kaiju��� is a sub-classification of ���science fiction & fantasy��� novels, which are a sub-classification of ���fiction���, which is a sub-classification of ���books���.

Though the W3C list is in English (as with most web specs), there is no requirement to have all of your categories in English. The final entry, ������������, is ���Kaiju��� in Japanese.

This addition to the Web App Manifest was much-needed and, along with IARC rating (which we also landed recently) will help our users more easily find the resources they���re looking for. Many hearty congrats to Rob for landing this update and for being added as an editor of the spec!

July 6, 2017

Your Site���Any Site���Should be a PWA

The other day, Frances Berriman���who coined the term ���Progressive Web App������wrote a bit about how she came up with that name. In it she clearly points out that the name has become a little problematic in dev circles:

I keep seeing folks (developers) getting all smart-ass saying they should have been PW ���Sites��� not ���Apps��� but I just want to put on the record that it doesn���t matter. The name isn���t for you and worrying about it is distraction from just building things that work better for everyone. The name is for your boss, for your investor, for your marketeer. It���s a way for you to keep making things on the open web, even those things that look really ���app-y��� and your company wants to actually make as a native app, 3 times over. They don���t want you to make websites anymore, but you still can if you���re sneaky, if you tell them it���s what they think they want.

As someone who is at once a practitioner, an educator, and a consultant on web projects, this can be tough to wrestle with. But like DHTML, Ajax, and HTML5 before, when viewed as a catch-all term for an approach to building stuff for the web it really shouldn���t matter that the word ���app��� is in there. Sure, it could have been ���site��� or ���thang���, but when we���and I���m talking to the practitioners here���hear someone talking about PWAs, we need to take the broad view.

Jeremy Keith made a really solid case for the broad usefulness of PWAs:

Literally any website can be a progressive web app:

switch over to HTTPS,

add [a JSON manifest file](https://www.w3.org/TR/appmanifest/) with your [metacrap](https://www.well.com/~doctorow/metacr...), and

add a service worker.

PWAs don���t require you use a particular JavaScript framework or any JavaScript framework at all. You don���t need to be building a Single Page App either. In fact, it will probably be easier if you���re not.

If you work on a website, there���s a really good chance your site could benefit from the technologies and approaches aggregated under the PWA umbrella:

Works on any device (a.k.a. progressive enhancement and responsive design)? Check.

Secure by default? Check.

Links to any core functionality or content? Check.

Easily shared and discovered? Check and check.

Better network resilience and faster page loads? Check and mate.

Depending on what you���re building, your site might even benefit from features like

push notifications,

syncing data in the background (when your site���s not open), and

install-ability.

Every project is different, but there���s a good chance yours should be a PWA or at least have some of the features of one. To quote Christian Heilmann:

Nothing necessary to turn your current web product into a PWA is a waste. All steps are beneficial to the health and quality of your product.

What are you waiting for?

June 14, 2017

Adding Paragraphs in Zillow Should Not be This Hard

Kelly and I are in the process of selling our (beautiful) home and I have been amazed at how difficult it���s been for our agents to break up the listing description into paragraphs, especially on Zillow. After a ton of trial and error���after all, I wasn���t gonna let poor software design trump readability���I found a solution.

TLDR; Insert a blank line between the paragraphs and put ��� ������ (that���s a space followed by a tab) on that line.

Note: I wouldn���t normally blog about something like this. My preference would have been to leave a comment on the Zillow Questions thread on this topic, but that forum has been shut down. I wanted to make sure other people would be able to find and use this solution.

The Problem

On Zillow (and many other real estate and other sites), you are only given a standard textarea to enter a description. Ignoring the fact that they hard-code it to be 78px high, I���m cool with that. The problem is that their field does not respect hard or soft returns and reduces them to a single line break.

This has been the subject of much consternation within the Zillow community and the source of a lot of cludgey ���workarounds��� like putting single underscores on otherwise empty lines just to get some semblance of paragraph-level separation. Blech!

Why is This a Big Deal?

Paragraphs serve as a distinct piece of writing. They generally encapsulate one idea or series of related ones. The space between them also gives your eyes a moment to rest and your brain a moment to process what you just read. Without them, text is just one big jumble.

Here���s an excerpt from our home���s description without the paragraph separation:

Welcome to quintessential Northshore living! This 3 bedroom, 2 and a half bathroom home features beautifully restored original built-ins, wood trim, wavy glass windows, and vintage light fixtures throughout. Open and spacious, this craftsman bungalow lets you live with the comfort of new construction amenities while still enjoying the quality craftsmanship and elegance rarely found in newer homes. The main floor features large dining and living areas meant for entertaining, complete with a two-story private deck. The second floor is designed for family, with a spacious master suite and relaxing spa bathroom. The additional second floor bedrooms provide room for a growing family or visiting guests, and unlike many period homes, this house also has ample storage in both built-ins and closets. The second full bathroom features a clawfoot tub and shower, as well as a convenient and discrete laundry closet.

That���s rough. Broken up, it flows much better:

Welcome to quintessential Northshore living! This 3 bedroom, 2 and a half bathroom home features beautifully restored original built-ins, wood trim, wavy glass windows, and vintage light fixtures throughout. Open and spacious, this craftsman bungalow lets you live with the comfort of new construction amenities while still enjoying the quality craftsmanship and elegance rarely found in newer homes.

The main floor features large dining and living areas meant for entertaining, complete with a two-story private deck. The second floor is designed for family, with a spacious master suite and relaxing spa bathroom. The additional second floor bedrooms provide room for a growing family or visiting guests, and unlike many period homes, this house also has ample storage in both built-ins and closets. The second full bathroom features a clawfoot tub and shower, as well as a convenient and discrete laundry closet.

Expand that to the full description (around 440 words) and you quickly realize how much paragraphs matter.

Coming up With a Solution

Having seen the forum discussions, I already knew inserting br elements was out. The field treated the element as text and would literally display ���<br>��� on the page. No dice.

One enterprising user discovered that an underscore on a blank line worked. The underscore was visible, sure, but it didn���t bother her. It did, however, bother me. So I opted to riff on her idea and test every invisible character I knew. There are a bunch of them. Here are a small selection:

space,

non-breaking space,

tab,

em-space,

en-space,

thin space,

zero-width space,

etc.

Sadly, on their own, none of these seemed to work (despite one user having luck with a single space a few years back). The system must be doing some basic sanitization on the back-end to remove white space. Knowing this, I began to play around with combinations, hoping to trip it up. Finally I discovered that a space followed by a tab worked reliably.

As tab is not easily typed in forms (browsers will move focus to the next field), I offer the two characters in this code block for your copy and paste pleasure, should you ever need it:

���

I honestly hope Zillow fixes their form at some point, but given that this has been a request for more than three years, I don���t think it���s likely to get fixed any time soon. Fingers crossed they���ll get to it one day. And while they���re at it, maybe they can make the texture a little taller too. Or at least give us back the ability to resize it.

May 26, 2017

My 2017 Mentees

Early this year, I put out the call to anyone who might be interested in a mentorship with me. The response was overwhelming and the decision of who to work with this year was really tough. After a great deal of consideration, however, I chose not one, but two folks I really wanted to work with this year: Amberley Romo and Manuel Matuzovi��.

I���ve been working with the two of them for a few months now and wanted to highlight a bit about who they are and what we are working on.

Amberley Romo

Amberley���s story really resonated with me. She is heavily invested in the Web as a tool for good. A force capable of bringing more equity to this world.

Growing up with a nonverbal sibling with intellectual and developmental disabilities was one of the single most formative experiences of my life. I find myself very lucky to have been born when I was, to enjoy growing up without being oversaturated with technology, but witnessing and participating in the periods of growth that I have. One of the ways I personally benchmark that progress is in the evolution of the technology my sister used to communicate.

Over the last few years, Amberley has performed in a number of different roles in and around the Web, but in the last year she���s been getting more serious about her career as a web developer. She is incredibly motivated and enrolled herself in a 3-month, full-time development accelerator to deepen her understanding of software development. And in my discussion with her, it���s clear the force is strong with this one.

Much of my work with Amberley has, thus far, been centered around career development. We���ve spent a lot of time discussing what it���s like to work for smaller companies and large corporations and the benefits and frustrations inherent in each.

Outside of her day job, we���ve discussed opportunities for her to channel her talent into worthwhile open source projects. It was kismet that just as we started discussing this, I received an email from Shay Cojocaru, a front-end dev at The Center for Educational Technology (CET) in Israel. He introduced me to a project he was working on: CBoard. CBoard is an open source tool aimed at making communication easier for non-verbal people��� like Amberley���s sister, who she had mentioned in her application. The stars had aligned. After all, Amberley has had a lot of experience with these tools, both in analog and digital form.

It���s an understatement to say I���m very excited to see where this partnership goes. I���m also keen to discover new opportunities and learn more about Amberley in the months ahead. She���s an amazing lady.

Follow Amberley and check out her work

Twitter: @amberleyjohanna

Blog: amberley.me

Portfolio: amberleyromo.com

LinkedIn: @amberleyromo

Github: @amberleyromo

Manuel Matuzovi��

To be honest, Manuel was on my radar well before he applied for my mentorship. I was already following and sharing his writings on Medium and was impressed with his interest in generating practical introductions to accessibility for front-end developers. He has a knack for turning something that seems huge and daunting into something that is manageable and���dare I say���easy to understand and implement.

In his application, Manuel talked about his interest in continuing to grow as a developer, but also to do more to share what he knows, both in prose and at conferences. Seeing how much he has to offer, I leapt at the chance to help him do that. I want his work to get more exposure. I can easily see him contributing to Smashing Magazine and A List Apart and advocating for a more equitable Web on stage at Beyond Tellerrand and Generate.

In our work together over the past few months, we���ve worked on

developing the talk he gave at Wordcamp Vienna,

developing a talk and negotiating his participation in PiterCSS in Saint Petersburg, Russia; and

a substantial overhaul of the Adaptive Web Newsletter.

I know for a fact that Manuel would find success in his endeavors without me; he has the talent and he has the drive���no question. I���m just thankful I get to play a small part in his journey.

Follow Manuel and check out his work

Twitter: @mmatuzo

Medium: @matuzo

Codepen: @matuzo

May 24, 2017

Progressive Web Apps and the Windows Ecosystem

I had the great pleasure of delivering a talk about Microsoft���s strategy towards Progressive Web Apps at Build. You can view the slides or watch the recording of this talk, but what follows is a distillation of my talk, taken from my notes and slides.

I���m here to talk to you about Progressive Web Apps, but before we really tuck into that, I wanna give a shout out to an app that���s really impressed me. This is Expense Manager by the folks at Vaadin:

I do a lot of traveling and it���s helpful when I can easily track my expenses. Their app is simple but refined in this regard. It���s snappy and provides a great overall UX; it���s also cross platform, which is nice since I often jump between different OSes across mobile and desktop.

The experience on the desktop version of their app is obviously a little better because I���ve got more real estate for viewing my expenses, but the same attention to detail has clearly been paid to the experience in both form factors, which is nice to see.

Oh, and a little secret here��� it���s a web app. In fact it���s a Progressive Web App. You should really play around with it yourself and kick the tires a bit to see how it���s made.

What is a Progressive Web App?

Now that we���ve seen one in action, I want to start by clarifying what a Progressive Web App is, just so I���m sure we���re all on the same page before we go down this rabbit hole. As a point of clarification, you���ll hear me use the terms Progressive Web App and PWA interchangeably.

So what is a Progressive Web App? Let���s ignore the first part of this term for a moment���progressive���I promise I���ll circle back to it shortly. Now the term ���web app��� may sound like something you can put your finger on, right? It���s software, on the Web, you use to complete a task. Like an expense manager, but it can be any website or property, really.

And so it is with Progressive Web Apps too.

���Web apps��� in this context can be any website type���a newspapers, games, books, shopping sites���it really doesn���t matter what the content or purpose of the website is, the ���web app��� moniker is applicable to all of them. The term could just have easily been progressive web site and it may be helpful to think of it as such. It doesn���t need to be a single page app. You don���t need to be running everything client side. There are no particular requirements for the type of PWA you are developing.

Essentially, a PWA is a website that is capable of being promoted to being native-ish. It gets many of the benefits of being a native app (some of which I will cover shortly), but also has all of the benefits of being a website too. If you���ve looked at or developed a Hosted Web App(HWA), which Microsoft introduced with Windows 10, PWAs are very

similar. In fact, if you���ve built an HWA, it shouldn���t be too difficult for you to convert it into a PWA and, in doing so, you���ll get a ton of extra goodies for free��� but I���m getting ahead of myself.

Here���s a quick comparison of the native Twitter app and Twitter Lite, as seen on an Android device:

A video showing the native Twitter Android app and Twitter Lite, side-by-side to demonstrate how similar they are.

You���ll notice that from a quality, polish, and user experience perspective, they are nearly indistinguishable. And this is just the first iteration of Twitter Lite. It launched last month. The only real difference is that one was built using Web technologies and lives at a URL.

Though the ���progressive web apps��� moniker was coined by Frances Berriman in 2015 and has quickly become a buzzword in our industry, it���s important to recognize that this idea of the Web as native is not new.

Back in 2007, Adobe introduced Apollo, later renamed the Adobe Integrated Runtime (a.k.a. Adobe AIR). This technology enabled designers and developers to build native apps in Flash or using Web technologies���HTML, CSS and JavaScript. It was pretty revolutionary for the time, supporting drag & drop, menu bar integration, file management, and more.

In 2009, Palm debuted webOS with the Palm Pre. All software for webOS was built using web technologies. Sadly, as an operating system in the handset space, it failed to catch on, but LG has licensed webOS for use in smart TVs and is experimenting with it for IoT devices and smartwatches.

Since that time, more OSes have begun embracing Web technologies as a means of building applications. Windows 8 allowed Windows Store apps to be written in HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. And Firefox OS and Chromium/Chrome OS are fundamentally tied to to the Web stack.

Countless tools have followed Adobe���s lead as well, enabling designers and developers to use their Web skills to build native applications for the vast majority of operating systems out there. React Native, Ionic, Electron, PhoneGap, Appcelerator��� the list goes on and on. Obviously there���s something to the idea of building native software using Web technologies. Progressive Web Apps are a brilliant way of accomplishing this in a standardized, consistent, way.

What makes a PWA a PWA?

Google���s Alex Russell defined 10 characteristics he believes define this new breed of Web application:

Progressive: It works for every user, regardless of browser choice because it���s built with progressive enhancement as a core tenet.

Responsive: The UI adapts to fit any form factor.

Network independent: It works offline and on low-quality networks (which is something Service Worker helps with).

App-like: It feels like an app in terms of responsiveness and UX.

Fresh: The experience is always up to date (another area where Service Worker shines).

Safe: It is served via HTTPS to prevent snooping and to ensure content hasn���t been tampered with.

Discoverable: Search spiders can identify it as an app because it uses a Web Application Manifest (and a Service Worker).

Re-engageable: It can re-engage users through features like push notifications.

Installable: It can be installed by users if they find it useful. This could be done independently of���but is not necessarily exclusive of���app stores.

Linkable: It is easily accessed (and shared) via a URL.

Let���s tuck into the installable piece first since this is the bit that really sets a PWA apart from a standard website. Now many might view this as a continuation of the competition between Web and native development. I don���t think of the two as being competitive, so much as being choices. We should choose our development approach based on the needs of our project, team, budget, etc. It���s good to have options and both approaches have their strengths.

Web vs. Native

Web *or* Native?

It depends.

Often Web tech gets dismissed for not having the capabilities of native apps. That���s changing rather rapidly. A visit to whatwebcando.today will give you a run-down of what your browser supports; you might be surprised with what you���ll learn about your browser���s capabilities. And if the end user experience is really good, does it matter what the underlying technology is?

Well, it might���

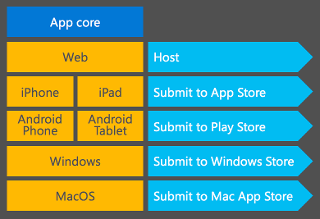

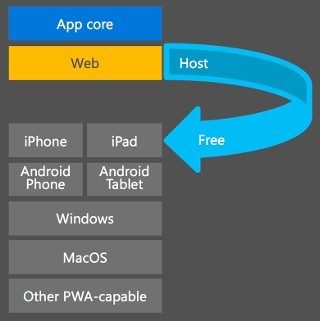

In the Web vs. native discussion, time to market is an aspect that isn���t often discussed. With a traditional web and native approach, each platform is typically built atop a core API. The apps are designed and developed independently, using different toolsets and languages and requiring different skills from the development team. And even in instances where they are all created using a single tool, the timeline needs to be padded in order to account for submission to each app store. That can cause delays in getting your product in front of users. It can also delay your delivery of critical updates.

Contrast that with building your software as a web-based product with the characteristics of a PWA. Using this approach, you can build it once and deploy it everywhere��� even to platforms that don���t support PWAs! And if you opt to submit your app to the various app stores, you could likely get away with a a one-time submission because updates will be seamless from there on out���it is the Web after all.

Now that we���ve talked about install ability���the ���app��� bit, if you will���let���s circle back to that first principle of Progressive Web Apps: progressive. It must be important, after all it is literally the first word in this approach. ���Progressive��� in this context refers to progressive enhancement. In case you���re unfamiliar with the idea, I���ll provide a quick analogy; I���m a huge music and movie fan, so we���ll focus on sound for this analogy.

Back in the early days of recording, we only had a single speaker (or horn, back in the Victrola days) to relay the sound to our ears. Round about the 1930s, modern two-channel stereophonic sound was invented to solve a cinematic problem: in early ���talkies��� a single channel of sound was delivered through multiple speakers, which sometimes led to a weird situation where a performer would be on one side of the screen, but their voice would be coming from the other side (the speaker near you). Stereo sound allowed the actor���s voice to follow them in a much more natural way. Even with this advancement, though, stereo recordings could still be listened to on a single speaker by combining the channels.

Over time, stereophonic sound gave way to quadrophonic (or ���surround���) sound and we kept adding more channels��� and more channels, creating more and more immersive experiences. But even though a recording might sound best in 16.2 or 22.21 channels of sound, movies, television, and music mastered for complete immersion can still be appreciated on a single, mono bluetooth speaker or on your mobile device (which is basically in mono when you���re viewing it in landscape mode). That is progressive enhancement.

An animated explanation of progressive enhancement using sound channels.

Progressive enhancement is concerned with honoring the core purpose of an experience���in software���s case the core purpose of a project and the core tasks a user will want to accomplish using it. The core experience should always be available, regardless of device or browser being used or the capabilities or limitations of that device��� or of the user. It doesn���t mean you can���t create a better experience for folks who can benefit from that, but you never do that to the exclusion of your users.

And yes, that means having an experience that works when JavaScript doesn���t. But that���s a whole other talk���

With progressive enhancement, we build the baseline experience and then enhance it as we are able to. In practical terms, progressive enhancement ensures people can use your product, regardless of

Unsupported browser and/or device features Network issues that block or delay important assets,

Browser plug-ins that interfere with JavaScript execution,

3rd party code that interferes with JavaScript execution.

Proxy browsers that optimize/adjust your code,

Your users requiring alternate input methods or assistive tech,

etc.

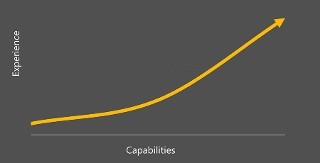

A chart plotting capabilities against experience, showing a steady improvement in experience as the number of capabilities increase.

Let me walk you through a very basic example of progressive enhancement in practice as I think it will illustrate this point.

Here we have an email input field:

<input type="email" name="email" id="email"

required aria-required="true">

view raw

email-input.html

hosted with ❤ by GitHub

The ���email��� field type was introduced in HTML5, so older browsers may not support it. Those that don���t will provide the default input type���a text field���to users. That���s totally fine���it���s all we had for more than a dozen years before HTML5 came along! But even if a user���s device does support email fields, it���s implementation may vary. Based on how a browser answers the following questions, users will end up with different experiences:

Do you support for email input type?

Do you support the HTML5 form validation algorithm including the email format?

Do you offer a virtual keyboard?

Moving on to the required attribute���another HTML5 introduction���some browsers will use it for input validation, some won���t know what to do with it. Those that implement this feature may block form submission if the field is left empty, but some won���t do anything with that info even if they know the field is empty!

Finally, there���s the aria-required attribute. This is a part of the ARIA (Accessible Rich Internet Applications) spec and is used to inform assistive technology if the field is required. But it���s possible the browser may not support the attribute or that the assistive tech being used may not do anything with that information even if the browser does expose it.

In terms of experience of this field, it improves incrementally along a path like this:

Input���

with required notification to assistive tech���

with required enforcement���

with email type validation���

with speedier entry via virtual keyboard.

Now think about that for a second���this incredible variety of experience is created by one HTML element when you add three specific attributes to it. And the experienced is enhanced���progressively���as the browser���s and operating system���s capabilities increase. Amazing!

As I mentioned, progressive enhancement ensures people can use your product, no matter what. You could just as easily swap in ���PWA��� for ���progressive enhancement��� in that statement. After all, PWAs give you network awareness and independence, they can be used to lower the overall cost of using your product for your for users through smart caching, they enable access to native APIs on certain platforms, and they provide more ways for your product to get discovered (e.g., search, store, links). Those are some impressive progressive enhancement bona fides.

Additionally, the two technical lynchpins of PWA���Web App Manifest and Service Worker���are ignored if they aren���t supported. Products you build using them will continue to work really well, even in their absence. They are, by definition, progressive enhancements too.

Now I���ve mentioned Service Worker a few times, so it probably makes sense to do a little sidebar here to explain what Service Workers are. A Service Worker is a proxy spawned by JavaScript that can handle a variety of tasks involving the network. They can

Manage offline experiences,

Intercept and respond to or modify network requests,

Manage caching,

Receive and handle push notifications, and

Handle background sync requests.

Note: At this point in the presentation, I passed the mic to my colleague Jeff Burtoft to give a quick demo of Service Worker in practice.

What���s the timeline for Progressive Web Apps in Windows?

Now that we���ve covered the groundwork of PWAs, I want to discuss where they fit in the Windows ecosystem. As I mentioned earlier, Windows has a history of supporting Web tech, but it even predates Windows 8. Back in Windows 7 we began supporting pinned sites. They enabled developers to customize a sticky tab in the taskbar that provided quick access to key tasks, a customizable browser UI, and more. Then, in Windows 8, packaged apps could be completely written in HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. In Windows 10 we introduced Hosted Web Apps, which enabled your wholly web-based product to be distributed and installed via the Windows Store. And now we are in the process of taking our support of the Web to the next level with Progressive Web Apps.

In terms of the work necessary to make this happen, the Edge team has already landed Fetch API support. Fetch is the powerful successor to XMLHttpRequest that is a critical underpinning of Service Worker. As I mentioned, Hosted Web Apps arrived with Windows 10 and they provide a secure, discrete container for Web apps within Windows that will also be used with PWAs. Additionally, WinRT provides programmatic access to OS internals like the calendar, contacts, Cortana, and more via JavaScript.

Our engineering effort around Service Worker kicked off about a year ago and we���re making great progress in bringing PWAs to Edge and Windows. Support for PWAs will become available to Windows Insiders early this summer. Initially, Service Worker, the Cache API, and the Push API will be behind a feature flag.

Once PWAs are fully supported, they will use the same container technology currently in use for Hosted Web Apps. As I mentioned, it���s an established container with excellent performance and a ton of benefits:

Standalone Window

Independent from browser process

** Less overhead

** Isolated cache

** Nearly unlimited storage (indexed DB, localStorage, etc.)

Offline & background processes

Access to Windows Runtime (WinRT) APIs via JavaScript

** Calendar

** Cortana

** Address Book

On Windows, Progressive Web Apps are essentially Hosted Web Apps, evolved. In fact, you could build your PWA and ship it as an HWA today and when the remainder of the PWA stack lands, it will automatically transform into a full-fledged PWA (another benefit of the Web for distribution).

How does a user discover a Progressive Web App?

Now that we���ve seen how PWAs operate within Windows, I want to take a few minutes to talk about how users will find your PWAs. As part of our initial move to support Progressive Web Apps, we will be enabling users to discover and install them from within the store and in Bing search results.

Screenshots of Bing search results and the Windows Store, highlighting how an app might appear in both contexts.

Now you may be wondering, with all of the awesomeness the Web has to offer, why does it make sense for PWAs to reside in app stores? There are numerous reasons:

It puts PWAs on equal footing with native apps.

Stores provide an alternate means of discovery for PWAs.

Users are generally more comfortable trusting software that has been reviewed for quality and safety.

Developers can get more insight into their users through reviews and ratings as well as analytics concerning installs, uninstalls, shares, and performance.

Having a store where users download software also reduces the cognitive overhead of tracking multiple sources for installing apps.

PWAs can get into the Windows Store in one of two ways. The first is through active submission. Using a tool like the open source utility PWA Builder, you can generate the necessary native wrappers used by the various app stores and manually submit your PWA.

Note: I invited Jeff back up on stage to walk through building a PWA and submitting it to the Windows Store using PWA Builder.

Obviously we want Windows users to have access to as many quality PWAs as possible, but we recognize that not all development teams have the time to submit and maintain their apps in the Store. To address this, we���ve developed an approach to enable their apps to be easily discovered in the Store too. For lack of a better term, we���re currently calling this process ���passive ingestion���.

We are already using the Bing Crawler to identify PWAs on the Web for our PWA research. The Web App Manifest is a proactive signal from developers that a given website should be considered an app; we���re listening to that signal and evaluating those sites as candidates for the Store. Once we identify quality PWAs, we���ll automatically generate the APPX wrapper format used by the Windows Store and assemble a Store entry based on metadata about the app provided in the Web App Manifest.

We completely understand that some of you may not want your products automatically added to the Store and we respect that.

By adding these 2 lines to your site���s robots.txt file, the Bing Crawler will ignore your Web App Manifest, opting your site out of this process:

User-agent: bingbot

Disallow: /manifest.json

view raw

robots-opt-out.txt

hosted with ❤ by GitHub

We are working on a set of criteria that will help us separate quality PWAs from sites that simply appear PWA-like. It���s still early days, but our consideration of what constitutes a ���quality��� PWA hinges on the following:

Does this site have a Web App Manifest? In our initial crawl of sites looking for PWAs, we discovered over 1.5 million manifests across 800k domains. Looking at a selection of these sites, we discovered that not all are good candidates for ingestion. Some aren���t PWAs at all, others have a boilerplate manifest generated by tools like favicon generators.

Does the Web App Manifest suggest quality? We will be looking for non-boilerplate manifests that include a name, description, and at least one icon that is larger than 192px square.

Is the site secure? At this point, we are only looking for HTTPS, we aren���t evaluating CSP or other protections.

Does the site have a valid Service Worker? Mozilla has a bunch of recipes if you are looking for somewhere to start.

Is the site popular? We will prioritize sites that rank highly on Alexa, Quantcast, and other ���top sites��� lists.

Does the site pass automated testing for quality? There are a number of tools out there for this, including our Site Scanner, Lighthouse, aXe, and more.

Is the app content free? There are certainly ways to charge for apps and content in the Windows Store, but we won���t passively ingest any sites that require a licensing fee or subscription. You���ll be able to submit those manually though.

Does the app pass manual review? PWAs will need to meet the standards of the Windows Store, just like any other app. We will not ingest apps that violate laws or Store policies.

Once in the Store, we���ll notify developers of their draft Store entry and they will be able to claim their apps to take complete control of their Store presence. Regardless, whether they got their by passive ingestion or my manual submission, the Web App Manifest will provide the basic set of information used for the app in the Store: name, description, icons, and screenshots. We���re also actively working with others in the W3C to introduce support for app categories and IARC ratings.

PWAs will appear alongside native apps in the Store, with no differentiation. From a users��� perspective, a PWA will just be another app. They will install just like any other app. They will have settings just like any other app. They will uninstall just like any other app. They will also be shareable via URL or the Store. PWAs will be first-class apps on Windows.

Phew��� that was a lot to take in. At this point, you might have some questions. Here are a few I imagine you���re wrestling with.

Should I forget everything I know and start building a Progressive Web App?

No. Progressive Web Apps are just one more way you can build a high-quality app experience.

Will Microsoft drop support for my favorite programming language in favor of Progressive Web Apps?

No. We are committed to supporting a breadth of language options when it comes to developing apps.

Are Progressive Web Apps the right choice for my project?

Maybe. When evaluating native app development in relation to Progressive Web Apps, here are some of the questions I recommend asking���

Are there native features the Web can���t offer that are critical to the success of this product?

What is the total cost (time and money) of building and maintaining each platform-specific native app?

What are the strengths of my dev team? or How easy will it be to assemble a new team with the necessary skills to build each native app as opposed to a PWA?

How critical will immediate app updates (e.g., adding new security features) be?

In other words, the choice between PWA and native should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. For example���

If you are looking to craft an experience that takes full advantage of each platform you release it on and you want to agonize over every UX detail in order to differentiate your product��� native might be the best choice for you.

If you are maintaining a product on multiple native platforms in addition to the Web and they are all largely the same in terms of look & feel and capabilities, it may make more sense to focus all of your efforts on the Web version and go PWA.

If you are planning a brand new product and the Web provides all of the features you need (especially when you also consider the additional APIs provided via the host OS), building a PWA is probably going to be a faster, more cost-effective option.

Should I consider Progressive Web Apps as a solid option when developing software for Windows?

Definitely.

You probably have more questions. I���ll do my best to answer them in the comments.

Slides

Slides from this talk are available on Slideshare.

Video

A video recording of this presentation (including Jeff���s demos) is available on Channel 9.

Crazy as it sounds, 22.2 is actually the standard used by Ultra-High Definition (UHD) television. ↩

May 3, 2017

PWAs + Desktop = Equity, Opportunity, and Reliability

Next week I���ll be giving a talk on Progressive Web Apps (PWAs) on Windows (and desktop) at Microsoft Build. While researching folks perspectives on PWAs for the desktop, I stumbled on this post from Justin Ribeiro. In it, he makes a solid case for why discussions of PWAs should not be limited to mobile contexts:

As web developers we use the desktop browser different than an average user. We use the desktop to develop and we sometimes fall prey to assumptions about the platform from that experience.

I know for a fact that right here in my backyard���Chattanooga, TN, self-proclaimed ���Gig City������connectivity is still a problem. Many of the folks who go through the digital literacy training programs offered by Tech Goes Home Chattanooga���which Kelly runs���don���t have an Internet connection at home. Period.

The adults and seniors taking TGH CHA classes may not know the value of or can���t afford Internet access. Students have an Internet connection at school, of course, but when they go home to complete their homework, they���re in the same boat. And even when folks have access, in many cases the connection is sub-optimal. Many access the Internet via a mobile or throttled connection tailored to low-income families.

Justin again:

Desktops can suffer the same ills as any mobile device, no matter how fast you think your LAN or uplink may be. Our assumptions about the desktop experience are like mobile; we believe in a perfectly fast and always connected world that does not exist.

Every improvement we can make with flakey mobile networks in mind pays dividends for folks who are using laptops and other devices without a reliable connection. PWAs excel at this.

Ultimately, the quality of the experience is what matters, but it���s not all about the network. As Alex Russell points out, reliability is also key (and it���s why native software has traditionally had an edge over the Web):

Think of it this way: the first load of a native app sucks. It���s gated by an app store and a huge download, but once you get to a point where the app is installed, that up-front cost is amortized across all app starts and none of those starts have a variable delay. Each application start is as fast as the last, no variance. What native apps deliver is reliable performance.

PWAs enable us to provide a consistent experience and give us the ability to mitigate network issues, making a big difference for a lot of people regardless of the device they���re using. And once we���ve got that, we can make our products even more useful by tying them in to core system components such as address books, calendar applications, and notifications���many desktop operating systems provide JavaScript hooks for those, some standardized, some proprietary.

I���m quite excited to see where all of this goes. PWAs on the desktop could be a revolution in the software development space, especially given that both Google and Microsoft are already looking at ways to surface PWAs within their respective app stores. That means that PWAs will not only be viable on Android, but likely also Chrome OS and Windows 10 (including the newly-announced Windows 10 S).

March 30, 2017

Pondering fallback content

I don���t remember what got it stuck in my craw, but I���ve been thinking a bit about HTML fallbacks of late. If you���re unfamiliar, consider the following picture element:

<picture>

<source type="image/webp" srcset="/i/j/r.webp">

<img src="/i/j/r.jpg" alt="">

</picture>

view raw

pic-webp.html

hosted with ❤ by GitHub

This picture element has two children: one source referencing a WebP image and an img element referencing a JPG. This pattern demonstrates how picture elements must be built in order to validate, but it also reinforces a best practice that uses the fault tolerant nature of HTML parsers to guarantee every user gets something.

In very simplistic terms, here���s what happens when a browser encounters this markup:

The browser recognizes the picture element and begins parsing its content to determine how to render it, or

The browser doesn���t recognize the picture and ignores it, moving inside to look for any elements it might recognize.

In practical terms, this markup delivers two potential experiences. Older browsers that haven���t implemented picture get the JPG image. Newer browsers that have implemented picture get either the WebP (if they support that format) or the JPG (if they don���t). In this scenario, the img element can be (and often is) referred to as ���fallback content���.

So why have I been thinking about fallback content? Well, I���ve been thinking a lot about media formats and what happens when a user���s browser encounters a video, audio, or picture element that only includes formats it doesn���t support. For instance: A video element that only offers an AVI source is highly unlikely to be playable in any browser.1

<video>

<source src="my.avi" type="video/avi">

</video>

view raw

video-avi.html

hosted with ❤ by GitHub

So what happens when most browsers encounter this markup? Nothing. Blank space. If you added a poster, that would be shown, but the user gets no video controls and receives no indication that it should even be video content.

This is the correct behavior, according to the spec:

When no video data is available (the element���s readyState attribute is either HAVE_NOTHING, or HAVE_METADATA but no video data has yet been obtained at all, or the element���s readyState attribute is any subsequent value but the media resource does not have a video channel) ��� The video element represents its poster frame, if any, or else transparent black with no intrinsic dimensions.

It���s also a pretty crappy user experience if you ask me. Now it���s worth noting that the spec does allow for a better experience, but it doesn���t require it:

User agents that cannot render the video may instead make the element represent a link to an external video playback utility or to the video data itself.

That would offer a much better experience. Of course, since it���s not a requirement for standards-compliance, it���s not guaranteed. In fact, I have yet to encounter a browser that provides that kind of affordance. So if we want our users to receive that kind of a fallback, we need to it using a tool we do control: HTML. Here���s a stab at what that might look like:

<video>

<source src="my.avi" type="video/avi">

<p>Your browser doesn���t support AVI, but you can

<a href="my.avi" download>download this movie</a></p>

</video>

view raw

video-avi-fallback.html

hosted with ❤ by GitHub

Given how fallbacks work, you might expect a browser to offer up the inner paragraph and download link when it realizes there is no video data it can play. Sadly that���s not the case. They all still display either an empty space or the poster image.2

A better way?

Obviously the native fallback would be best, but I have no concept of how difficult that would be to do. So what if browsers did expose our fallback content when the only media types on offer are ones they don���t support?

It seems like this would offer a number of benefits:

Authors without the requisite skill or knowledge necessary to transcode media into the various formats necessary for cross-browser support would not be penalized (nor would their users);

CMS developers could provide a standardized, expected fallback pattern without worrying that content contributors might only upload one format that isn���t universally supported; and

It would allow these elements to be more forward and backward compatible���newer media formats could be rolled out easily without sacrificing a page���s usability in non-supporting browsers.

That last one is the biggie for me. We want to support as many users as possible, now and well into the future. This might be a way to reliably do that.

I took a Twitter Poll to gauge your thoughts, but that was just a yes/no. I���d love to know your detailed thoughts on this. Is there be any downside to this approach?

Safari is the only possible exception here, and that���s only if QuickTime supports the particular CODEC that was used to create the AVI in the first place. Pretty slim odds. ↩

In case you���re interested, I put together a CodePen walking through some of these scenarios. ↩

Pondering Fallback Content

I don���t remember what got it stuck in my craw, but I���ve been thinking a bit about HTML fallbacks of late. If you���re unfamiliar, consider the following picture element:

<picture>

<source type="image/webp" srcset="/i/j/r.webp">

<img src="https://www.aaron-gustafson.com/i/j/r..." alt="">

</picture>

view raw

pic-webp.html

hosted with ❤ by GitHub

This picture element has two children: one source referencing a WebP image and an img element referencing a JPG. This pattern demonstrates how picture elements must be built in order to validate, but it also reinforces a best practice that uses the fault tolerant nature of HTML parsers to guarantee every user gets something.

In very simplistic terms, here���s what happens when a browser encounters this markup:

The browser recognizes the picture element and begins parsing its content to determine how to render it, or

The browser doesn���t recognize the picture and ignores it, moving inside to look for any elements it might recognize.

In practical terms, this markup delivers two potential experiences. Older browsers that haven���t implemented picture get the JPG image. Newer browsers that have implemented picture get either the WebP (if they support that format) or the JPG (if they don���t). In this scenario, the img element can be (and often is) referred to as ���fallback content���.

So why have I been thinking about fallback content? Well, I���ve been thinking a lot about media formats and what happens when a user���s browser encounters a video, audio, or picture element that only includes formats it doesn���t support. For instance: A video element that only offers an AVI source is highly unlikely to be playable in any browser.1

<video>

<source src="https://www.aaron-gustafson.com/noteb..." type="video/avi">

</video>

view raw

video-avi.html

hosted with ❤ by GitHub

So what happens when most browsers encounter this markup? Nothing. Blank space. If you added a poster, that would be shown, but the user gets no video controls and receives no indication that it should even be video content.

This is the correct behavior, according to the spec:

When no video data is available (the element���s readyState attribute is either HAVE_NOTHING, or HAVE_METADATA but no video data has yet been obtained at all, or the element���s readyState attribute is any subsequent value but the media resource does not have a video channel) ��� The video element represents its poster frame, if any, or else transparent black with no intrinsic dimensions.

It���s also a pretty crappy user experience if you ask me. Now it���s worth noting that the spec does allow for a better experience, but it doesn���t require it:

User agents that cannot render the video may instead make the element represent a link to an external video playback utility or to the video data itself.

That would offer a much better experience. Of course, since it���s not a requirement for standards-compliance, it���s not guaranteed. In fact, I have yet to encounter a browser that provides that kind of affordance. So if we want our users to receive that kind of a fallback, we need to it using a tool we do control: HTML. Here���s a stab at what that might look like:

<video>

<source src="https://www.aaron-gustafson.com/noteb..." type="video/avi">

<p>Your browser doesn���t support AVI, but you can

<a href="my.avi" download>download this movie</a></p>

</video>

view raw

video-avi-fallback.html

hosted with ❤ by GitHub

Given how fallbacks work, you might expect a browser to offer up the inner paragraph and download link when it realizes there is no video data it can play. Sadly that���s not the case. They all still display either an empty space or the poster image.2

A better way?

Obviously the native fallback would be best, but I have no concept of how difficult that would be to do. So what if browsers did expose our fallback content when the only media types on offer are ones they don���t support?

It seems like this would offer a number of benefits:

Authors without the requisite skill or knowledge necessary to transcode media into the various formats necessary for cross-browser support would not be penalized (nor would their users);

CMS developers could provide a standardized, expected fallback pattern without worrying that content contributors might only upload one format that isn���t universally supported; and

It would allow these elements to be more forward and backward compatible���newer media formats could be rolled out easily without sacrificing a page���s usability in non-supporting browsers.

That last one is the biggie for me. We want to support as many users as possible, now and well into the future. This might be a way to reliably do that.

I took a Twitter Poll to gauge your thoughts, but that was just a yes/no. I���d love to know your detailed thoughts on this. Is there be any downside to this approach?

Safari is the only possible exception here, and that���s only if QuickTime supports the particular CODEC that was used to create the AVI in the first place. Pretty slim odds. ↩

In case you���re interested, I put together a CodePen walking through some of these scenarios. ↩