Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 218

June 21, 2019

Book News July 2019

Meet Me in Monaco: A Novel of Grace Kelly’s Royal Wedding

Hardcover –23 July 2019 (US & UK)

Movie stars and paparazzi flock to Cannes for the glamorous film festival, but Grace Kelly, the biggest star of all, wants only to escape from the flash-bulbs. When struggling perfumer Sophie Duval shelters Miss Kelly in her boutique to fend off a persistent British press photographer, James Henderson, a bond is forged between the two women and sets in motion a chain of events that stretches across thirty years of friendship, love, and tragedy. James Henderson cannot forget his brief encounter with Sophie Duval. Despite his guilt at being away from his daughter, he takes an assignment to cover the wedding of the century, sailing with Grace Kelly’s wedding party on the SS Constitution from New York. In Monaco, as wedding fever soars and passions and tempers escalate, James and Sophie—like Princess Grace—must ultimately decide what they are prepared to give up for love.

Katherine’s House

Paperback – 28 July 2019 (US & UK)

Kettlethorpe, a modest little group of buildings deep in the English countryside, has housed many lives woven of great events and private joys and griefs. It was the home of Katherine Swynford, perhaps the most romantic figure of medieval times, but before and after her of knights and farmers, soldiers and lawyers, maids and maidservants, whose footsteps echo through the house’s history. In telling the story of Kettlethorpe, this story touches on some of the greatest events in our history, from the Danish invasion and the Norman Conquest to the Battle of Lincoln Fair, the Pilgrimage of Grace and the Civil War. These were events that took place on Kettlethorpe’s doorstep. It passes through the great days of the Georgian country house to the fate of a converted ruin, a farmhouse and dower house for a hunting widow, keeping the estate going until close to the outbreak of the Second World War. A war in which, once more, Lincolnshire – “Bomber County” – would play such an important part. What’s more, this is a story not about the great or whom grand houses were built, but about what Cromwell called “the middling sort” – a little up in some generations, down in others, but with lives always within the compass of our imagination.

Anna, Duchess of Cleves: The King’s Beloved Sister

Hardcover – 1 July 2019 (US)

‘The King’s Beloved Sister’ looks at Anne of Cleves from a new perspective, as a woman from the Holy Roman Empire and not as a woman living almost by accident in England. Starting with what Anne’s life as a child and young woman was like, the author describes the climate of the Cleves court, and the achievements of Anne’s siblings. It looks at the political issues on the Continent that transformed Anne’s native land of Cleves – notably the court of Anne’s brother-in-law, and its influence on Lutheranism – and Anne’s marriage. Finally, Heather Darsie explores ways in which Anne influenced her step-daughters Elizabeth and Mary, and the evidence of their good relationships with her.

Was Anne – the Duchess Anna – in fact a political refugee, supported by Henry VIII? Was she a role model for Elizabeth I? Why was the marriage doomed from the outset? By returning to the primary sources and visiting archives and museums all over Europe (the author is fluent in German, and proficient in French and Spanish) a very different figure emerges to the ‘Flanders Mare’.

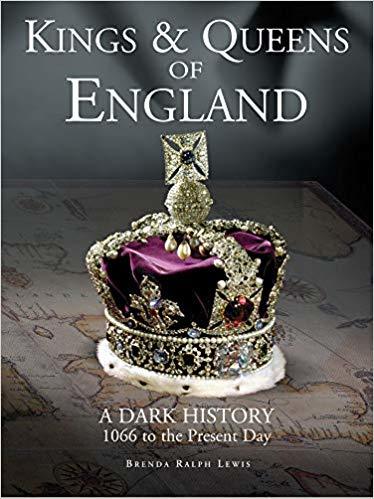

Dark History of the Kings and Queens of England

Hardcover – 14 July 2019 (UK) & 6 August 2019 (US)

Despite its reputation as the longest established in Europe, the history of the English monarchy is punctuated by scandal, murders, betrayals, plots, and treason. Since William the Conqueror seized the crown in 1066, England has seen three civil wars; six monarchs have been murdered or executed; the throne of England has been usurped four times, and won in battle three times; and personal scandals and royal family quarrels abound. The Dark History of the Kings & Queens of England provides an exciting and dramatic account of English royal history from 1066 to the present day. This engrossing book explores the scandal and intrigue behind each royal dynasty, from the ‘accidental’ murder of William II in 1100, through the excesses of Richard III, Henry VIII and ‘Bloody’ Mary, to the conspiracies surrounding the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1997 and the present-day troubles of Meghan’s family. Carefully researched, superbly entertaining and illustrated throughout with more than 200 colour and black-and-white photographs and artworks, this accessible and immensely enjoyable book highlights the true personalities and real lives of the individuals honoured with the crown of England – and those unfortunate enough to cross their paths.

Elizabeth I (Penguin Monarchs): A Study in Insecurity

Paperback – 4 July 2019 (UK) & 25 April 2019 (US)

In the popular imagination, as in her portraits, Elizabeth I is the image of monarchical power. But this image is as much armour as a reflection of the truth. In this illuminating account of England’s iconic queen, Helen Castor reveals her reign as shaped by a profound and enduring insecurity that was a matter of both practical politics and personal psychology.

The post Book News July 2019 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 20, 2019

Princesses of Orange – Éléonore de Bourbon

Éléonore de Bourbon was born on 30 April 1587 as the daughter of Henri I de Bourbon and his second wife, Charlotte Catherine de la Tremoille. Her father was a first cousin of King Henry IV of France, and thus she was closely connected to the French court. She had a half-sister from her father’s previous marriage and a full brother, who eventually succeeded to their father’s titles. Her future husband was the son of William, Prince of Orange and his first wife, Anna of Buren. His name was Philip William. When they were married in 1606, he was already 51 years old. He had had a troubled childhood. His mother died in 1558 when he was just four years old, and he was taken as a hostage in February 1568 by the Spanish and taken to Spain to be raised as a good Catholic. He never saw his father again, and the Dutch never again trusted him. By this marriage, the French king finally recognised Philip William as Prince of Orange.

Not much is know about Éléonore’s youth, but she was most likely raised at the French Court. Despite marrying a much older man, it is believed that it was a happy marriage. Éléonore followed her husband on his many campaigns. They would have no children together, but Éléonore raised her great-niece Louise de Bourbon. The marriage would come to an end quite suddenly when Philip William died after a failed medical treatment. He willed his entire inheritance to his half-brother, and Éléonore was left with nothing.

She was still young and perhaps expected to marry again. She died just 11 months later on 20 January 1619, still only 31 years old. It is not known what her cause of death was.

The post Princesses of Orange – Éléonore de Bourbon appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 19, 2019

The Year of Queen Victoria – Becoming Queen

Victoria had gone to bed knowing that her uncle King William IV was in terrible health and was not expected to live much longer. He had already reached his ultimate goal – living until Victoria had turned 18. He had been unable to attend her 18th birthday, but he sent her a grand piano as a birthday present. He also sent her an offer of her own establishment independent of her mother. By June 15th, William’s strength was fading, and he was unlikely to recover. On 18 June, he received the sacrament from the Archbishop of Canterbury. Queen Adelaide had not gone to bed for over ten days, and she was exhausted. She broke down as he received the sacrament to which he said, “Bear up! Bear up!” He was more concerned with her distress than his own suffering.

Victoria was looking forward to her upcoming accession with calmness and quietness, as she had written to her uncle King Leopold I of the Belgians on the 19th. Meanwhile, William was propped up in a leather chair to help with his breathing. His last spoken word was the name of his valet. He died that night at 2.20 A.M. His chamberlain, Lord Conyngham and the Archbishop of Canterbury sped from Windsor Castle to Kensington Palace in a coach. They arrived at Kensington Palace at five to closed gates, and the snoring porter was deaf to their calls. They rang the bell repeatedly until the porter finally heard and he led them into one of the lower rooms. They were soon forgotten again and were asked to wait. The Duchess of Kent finally woke Victoria at 6.

Early on the morning of 20 June 1837, the Princess awoke a Queen. She stood up and put a cotton dressing robe over her white cotton nightgown. Her mother held her hand as she escorted her down the stairs. Victoria closed the door behind her, shutting out her mother.

She later wrote in her diary, “I was awoke at 6 o’clock by Mamma, who told me the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Conyngham were here and wished to see me. I got out of bed and went into my sitting-room (only in my dressing gown) and alone, and saw them. Lord Conyngham then acquainted me that my poor Uncle, the King, was no more, and had expired at 12 minutes past two this morning, and consequently that I am Queen.” Lord Conyngham kissed her hand and handed her the certificate of the King’s death. The Archbishop told her that God would be with her. She then excused them, walked out and cried on her mother’s shoulder. The first thing she asked for was some time alone. She ordered her bed to be moved out of her mother’s room and into a room of her own. She had breakfast with Baron Stockmar and then wrote three letters – one to King Leopold, one to her half-sister Feodora and one to Queen Adelaide. She also received a note from the now widowed Queen Adelaide. She wrote, “Excuse my writing more at present, my heart is overwhelmed, and my head aches very much. Accept the assurance of my most affectionate devotion, and allow me to consider myself as Your Majesty’s most affectionate Friend, Aunt and Subject.”

At 9 in the morning, she received the Prime Minister “quite ALONE”, and they wrote a draft of her statement to the Privy Council which was to meet at 11. At the Privy Council, Victoria was led in by her uncles the Duke of Cumberland – who had succeeded William as King of Hanover – and the Duke of Sussex. Victoria spoke, “The severe and afflicting loss which the nation has sustained by the death of His Majesty, my beloved uncle, has devolved upon me the duty of administering the government of this empire. This awful responsibility is imposed upon me so suddenly, and at so early a period in my life, that I should feel myself utterly oppressed by the burden were I not sustained by the hope that Divine Providence, which has called me to this work, will give me strength for the performance of it, and that I shall find in the purity of my intentions, and in my zeal for the public welfare, that support and those resources which usually belong to a more mature age and to longer experience… Educated in England, under the tender and enlightened care of a most affectionate mother, I have learnt from my infancy to respect and love the constitution of my native country. It will be my unceasing study to maintain the reformed religion as by law established, securing at the same time to all the full enjoyment of religious liberty; and I shall steadily protect the rights, and promote to the utmost of my power the happiness and welfare, of all classes of my subjects.” She had made a marvellous first impression.1

The post The Year of Queen Victoria – Becoming Queen appeared first on History of Royal Women.

The Last Czars – Official Trailer

Coming to Netflix on 3 July 2019.

The post The Last Czars – Official Trailer appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Queen Victoria in her journal – 20 June 1837

“I was awoke at 6 o’clock by Mamma, who told me the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Conyngham were here and wished to see me. I got out of bed and went into my sitting-room (only in my dressing gown) and alone, and saw them. Lord Conyngham then acquainted me that my poor Uncle, the King, was no more, and had expired at 12 minutes past two this morning, and consequently that I am Queen. Lord Conyngham knelt down and kissed my hand, at the same time delivering to me the official announcement of the poor King’s demise. The Archbishop then told me that the Queen (Adelaide) was desirous that he should come and tell me the details of the last moments of my poor, good Uncle; he said that he had directed his mind to religion and had died in a perfectly happy, quiet state of mind, and was quite prepared for his death. He added that the King’s sufferings at the last were not very great but that there was a good deal of uneasiness. Lord Conyngham, who I charged to express my feelings of condolence and sorrow to the poor Queen, returned directly to Windsor. I then went to my room and dressed.

Since it has pleased Providence to place me in this station, I shall do my utmost to fulfil my duty towards my country; I am very young and perhaps in many, though not in all things, inexperienced, but I am sure, that very few have more real good will and more real desire to do what is fit and right than I have.

Breakfasted, during which time good faithful Stockmar came and talked to me. Wrote a letter to dear Uncle Leopold and a few words to dear good Feodora. Received a letter from Lord Melbourne in which he said he would wait upon me at a little before 9. At 9 came Lord Melbourne, whom I saw in my room, and of course quite alone as I shall always do my Ministers. He kissed my hand and I then acquainted him that it had long been my intention to retain him and the rest of the present Ministery at the head of affairs, and that it could not be in better hands than his. He then again kissed my hand. He then read to me the Declaration which I was to read to the Council, which he wrote himself and which is a very fine one. I then talked with him some little longer time after which he left me. He was in full dress. I like him very much and feel confidence in him. He is a very straightforward, honest, clever and goods man. I then wrote a letter to the Queen. At about half-past 11 I went downstairs and held a Council in the red saloon. I went in of course quite alone, and remained seated the whole time. My two Uncles, the Dukes of Cumberland and Sussex, and Lord Melbourne conducted me… I was not at all nervous and had the satisfaction of hearing that the people were satisfied with what I had done and how I had done it. Receiving after this, Audiences of Lord Melbourne, Lord John Russell, Lord Albemarle, and the Archbishop of Canterbury, all in my room and alone. Saw Stockmar. Saw Clark, whom I named my physician.

Wrote my journal. Took my dinner upstairs alone… At about 20 minutes to 9 came Lord Melbourne and remained till near 10. I had a very important and very comfortable conversation with him. Each time I see him I feel more confidence in him; I find him very kind in his manner too. Saw Stockmar. Went down and said goodnight to Mamma etc. My dear Lehzen will always remain with me as my friend but will take no situation about me, and I think she is right.1

The post Queen Victoria in her journal – 20 June 1837 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 18, 2019

Princess Victoria to King Leopold I of Belgium – 19 June 1837

The day before Victoria’s accession as Queen, Victoria wrote to her uncle King Leopold I of Belgium.

The King’s state, I may fairly say, is hopeless; he may perhaps linger a few days, but he cannot recover ultimately. Yesterday the physicians declared he could not live till the morning, but today he is a little better; the great fear is his excessive weakness and no pulse at all. Poor old man! I feel sorry for him; he was always personally kind to me, and I should be ungrateful and devoid of feeling if I did not remember this.

I look forward to the event which it seems is likely to occur soon, with calmness and quietness; I am not alarmed at it, and yet I do not suppose myself equal to all; I trust, however, that with goodwill, honesty and courage I shall, at all events, fail. Your advice is most excellent, and you may depend upon it I shall make use of it, and follow it.1

The post Princess Victoria to King Leopold I of Belgium – 19 June 1837 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Queen Elizabeth II – The 00s to the present day (Part five)

The Queen began the year 2000 with her 13th visit to Australia, but the health of both her mother and her sister remained on her mind. Her mother would celebrate her 100th that August and Elizabeth made sure it was an unforgettable occasion. First, there was a grand ball, which also marked the 70th birthday of Princess Margaret, the 50th birthday of Princess Anne and the 40th birthday of Prince Andrew. On the day of her birthday, the Queen Mother rode with the Prince of Wales in carriage up the Mall to Buckingham Palace. That summer the planning for the Queen’s Golden Jubilee two years later also began. After the September 11 attacks, Elizabeth joined a congregation of 2,700 – mostly Americans – at St. Paul’s Cathedral for a memorial service and she sang the words to the National Anthem.

Embed from Getty Images

Princess Margaret passed away in the early hours of 9 February 2002. Her funeral took place on 15 February – fifty years to the day of King George VI’s funeral. The Queen Mother had cut her arm in a fall two days before the funeral, but she still managed to attend. As scheduled Elizabeth left for Jamaica – the first stop on a two-week Golden Jubilee Tour – three days after the funeral. She called in every day to check on her mother. The Queen Mother died on 30 March 2002 with her daughter and Margaret’s grandchildren and her niece Margaret Rhodes by her side. She was 101 years old. On the night before the funeral, Elizabeth gave a televised address to her “beloved mother” at Windsor Castle saying, “I thank you also from my heart for the love you gave her during her life and the honour you now give her in death.” In early 2003, Elizabeth slipped and tore the cartilage in her right knee, which required surgery. She was frustrated with being stuck indoors, but she recovered well and was soon back to riding.

Embed from Getty Images

On 9 April 2005, the Prince of Wales finally married Camilla Parker Bowles – who had been gradually brought into the fold. The Church of England had recently relaxed their rules – allowing for divorcees to remarry. Elizabeth – also the Supreme Governor of the Church of England – decided it was inappropriate to attend the civil service – but 28 other members of the family did attend. She and Prince Philip did attend the “Service of Prayer and Dedication” afterwards at St George’s Chapel. Camilla became known as the Duchess of Cornwall. Just three months later, 52 people were killed in a terror attack in London and said, “I want to express my admiration for the people of our capital city, who in the aftermath of yesterday’s bombings are calmly determined to resume their normal lives. That is the answer to this outrage.” On 20 November 2007, Elizabeth and Philip celebrated 60 years of marriage, and there was a commemoration in Westminster Abbey where their grandson Prince William read from the Book of John. They flew to Malta – where they had lived as a normal couple long ago – on the 20th. On 21 December 2007, Elizabeth surpassed her great-great-grandmother Queen Victoria to become the longest-living British monarch.

Embed from Getty Images

On 29 December 2010, her first great-grandchild – Savannah Phillips – was born. This was followed by another great-granddaughter – Isla – in 2012. Her grandson Prince William married Catherine Middleton in 2011, and they have three children together. Prince Harry married Meghan Markle in 2018 and their first child Archie was born on 6 May 2019. Zara Phillips married Mike Tindall in 2011, and they have two children together – making a grand total of 8 great-grandchildren. Princess Eugenie married Jack Brooksbank in 2018, and so the total will probably grow in the near future.

On 6 February 2012, Elizabeth celebrated her Diamond Jubilee, but for Elizabeth, it would always be the day her beloved Papa died. In a statement, she said, “In this special year, as I dedicate myself anew to your service, I hope we will all be reminded of the power of togetherness.” In 2015, she also became the longest-reigning British monarch.

Embed from Getty Images

Her health has remained robust with few health scares in recent years. In 2013, she developed symptoms of gastroenteritis but was allowed to return home from the hospital the following day. She also had cataract surgery in May 2018. Prince Charles is expected to take on more of his mother’s duties as she grows older, but she does not intend to abdicate. She celebrated her 93rd birthday in 2019.1

The post Queen Elizabeth II – The 00s to the present day (Part five) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 17, 2019

Hedwig of Zagan – The King’s last hope for heirs

In 1365, Casimir III, King of Poland was 55, had been married three times, but still had no legitimate sons. His second wife, Adelaide of Hesse, whom he had repudiated in 1356 was still alive and fighting for her marital rights. Casimir instead decided to marry a much younger woman, in the hope that she would give him the desired son. His chosen bride was the teenaged Hedwig of Zagan.

A complicated marital situation

During his unhappy and childless marriage with Adelaide of Hesse, Casimir began an affair with the Prague townswoman, Krystyna Rokiczana, whom he soon married. This was a great scandal, not only because of Krystyna’s low rank but also because of the fact that he was still officially married to Adelaide. Adelaide soon left Poland but continued to fight for her rights.

Casimir and Krystyna separated around 1363. By then, Casimir had lost his only legitimate children, his two daughters by his first marriage to Aldona-Anna of Lithuania. The elder one, Elizabeth left behind a son and a daughter. Casimir considered this grandson, also named Casimir as his heir, but he desired to have sons of his own. His legal wife, Adelaide was about forty, never gave him children, and they were long since separated. Casimir wanted to marry again, but he would have to break the church’s rules.

As early as 1362, Casimir was considering Hedwig of Zagan to be his new queen. Hedwig of Zagan was born around 1350 or shortly before, as the daughter of Henry V, Duke of Zagan and Anna of Plock. Hedwig was from the Silesian branch of Poland’s royal Piast dynasty. The lands ruled by the Silesian dukes were in the west of Poland and were constantly disputed between the kings of Poland and Bohemia, as to who was their overlord. Casimir hoped that by marrying Hedwig, he would bring Silesia closer under his rule. Hedwig’s father was the most powerful Silesian duke after Casimir’s nephew, Bolko II, Duke of Swidnica. We know nothing of Hedwig’s appearance, but she was described as beautiful. As a young wife, she would also be easy to manipulate because of the king’s complicated marriage situation.

Queen of Poland

Casimir and Hedwig were married on 25 February 1365. Hedwig was about 14-15, or a little older, and Casimir almost 55. Hedwig was probably younger than Casimir’s granddaughter, Elizabeth of Pomerania. When Casimir’s previous wife, Adelaide, learnt of the marriage, she sent a complaint to the Pope. She pointed out the Casimir and Hedwig were related in the fourth degree. Adelaide also pointed out that the necessary papal dispensation was faked. She also demanded that Casimir dismiss Hedwig. The Pope also wrote to Casimir asking for him to set aside Hedwig and return to Adelaide. It is likely that Hedwig was convinced that the marriage to Adelaide was actually annuled. The Pope did not blame Hedwig for the situation and suggested that she was seduced by the king by trick. Even though the legitimacy of Hedwig’s marriage was disputed, she was crowned queen soon afterwards.

Despite the age difference, Casimir and Hedwig appear to have spent a lot of time together. Their favourite residence was the castle of Zarnowiec, where Adelaide have previously been imprisoned. Hedwig quickly bore three daughters: Anna around 1366, Kunigunde around 1368, and Hedwig in late 1369 or early 1370. Hedwig did not play any political role, and not much is known of her activity.

In 1368, Casimir was cleared of the accusations of faking the papal dispensation about his relationship to Hedwig. However, the Pope never recognised Hedwig’s marriage as valid. Unlike the papacy, the Polish clergy saw this marriage as valid. Even though Pope Urban V refused to recognise this marriage, he was willing to legitimise the daughters that came from it. On 5 December 1369, Anna and Kunigunde were legitimised. The youngest daughter, Hedwig, was either not born yet, or news of her birth had not yet reached the Pope. She would not be legitimised until October 1371, after Casimir’s death. Hedwig’s daughters, however, were not given rights to inherit the throne of Poland.

Hedwig’s middle daughter, Kunigunde died sometime before Casimir in 1370. In the autumn of 1370, Casimir suffered a fall from his horse. He was badly wounded, and by November, it was clear that he was dying. Hedwig had not born him any sons as he had hoped. His two likely successors were his nephew Louis, King of Hungary, or his grandson Casimir of Pomerania. On 3 November 1370, Casimir wrote his will and bequeathed his movable possessions to Hedwig and their two remaining daughters. He died two days later.

Hedwig was now a young widow aged 20 or a little older and had two young daughters. She had no control over who would inherit the Polish throne. It was Casimir’s nephew Louis, who became the new King of Poland. He was crowned as King of Poland on 17 November 1370. Hedwig and her daughters participated in the coronation.

Life after Queenship

Hedwig seems to have completely subjected herself to the new king. It was decided that her daughters will be brought back to Hungary with Louis and raised at his court and that Louis will arrange their marriages. Hedwig’s daughters left for Hungary in early 1371. She probably never saw them again. The older one, Anna married William, Count of Cilli in 1380. He was chosen by Louis, and his lands were far away from Poland. By this marriage, Anna had one daughter, another Anna, who later became a queen consort of Poland. The fate of Hedwig’s namesake daughter is less certain. Louis is thought to have arranged for her to marry around 1382, but who the groom was, and if this marriage ever actually happened is unknown. Louis remained in his home kingdom, and his mother, Casimir’s sister, Elizabeth, governed Poland. Hedwig herself returned to Silesia.

Before 10 February 1372, Hedwig remarried to Rupert I, Duke of Legnica, another Silesian prince. He was much closer to her age, and perhaps Hedwig chose to marry him herself. Very little is known about her second marriage except that she had two more daughters- Barbara, who married Rudolf III, Elector of Saxony, and Agnes, who became a nun. Hedwig died on 27 March 1390 in her early forties. Her brief time as queen was probably mostly forgotten by the Polish by then. She was buried in the collegiate church in Legnica.

Hedwig was only queen of Poland for five years. She did not bare Casimir a much-needed son, so she has mostly been forgotten by history. However, her memory has been revived recently, as she appears in the final episodes of the Polish television series Korona Krolow (Crown of Kings) which dramatises the reign of her first husband. 1

The post Hedwig of Zagan – The King’s last hope for heirs appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 16, 2019

Princesses of Orange – Charlotte of Bourbon

William, Prince of Orange, next chosen wife was Charlotte of Bourbon. She was born in 1546 or 1547 as the daughter of Louis, Duke of Montpensier and Jacqueline de Longwy, Countess of Bar-Sur-Seine. Her father supposedly intended for her to enter the church as well as some of her sisters, as he did not wish to pay a dowry for all of them. She was taken into the care of her aunt, the abbess of the Jouarre Convent. She was professed at the age of 13, but she wrote a protest. In 1565 – she was still only 18 years old – she became the abbess of the Jouarre convent. She reportedly received a secret Calvinistic education while at the convent, and her family was shocked when she escaped the convent in 1572 on the advice of Jeanne d’Albret, the Queen Regnant of Navarre, and she converted to Calvinism. She fled to the court of the Elector Palatine in Germany.

It was at this court that she met her future husband in 1572. It was supposedly loved at first sight, but it wasn’t until 1575 that William officially asked for her hand in marriage. Charlotte wasn’t the greatest match, and there were hardly any upsides to marrying her, despite her connections to the Palatine court. She could not offer him any kind of dowry as she had broken with her family. William was also still officially married to Anna of Saxony. The dubious annulment of this marriage made even Charlotte question the validity of her marriage. Despite this, William and Charlotte were married on 12 June 1575 in Brielle. Charlotte was 28, and William was 43. She became stepmother to his children from his other marriages, and they would have six daughters together. After six years of marriage, Charlotte finally reconciled with her father.

Tragedy struck on 18 March 1582 when an attempt was made on William’s life. He was seriously injured, and Charlotte devoted herself to nursing him back to health. Legend has it she plugged the wound with her finger for several days to stop the bleeding. William survived the assassination attempt, but the nursing had drained Charlotte to the point of exhaustion, and she died on 5 May 1582 of pneumonia. The public widely mourned her. She was buried in the Church of Our Lady in Antwerp.

The post Princesses of Orange – Charlotte of Bourbon appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 15, 2019

Princesses of Orange – Anna of Saxony

After the death of Anna of Buren, William, Prince of Orange, remarried to Anna of Saxony. Anna was born on 23 December 1544 in Dresden, the daughter of Maurice, Elector of Saxony and Agnes of Hesse. She would be their only surviving child, and she was just nine years old when her father died. She continued her education at her uncle’s court, who was now the Elector. Marriage negotiations began for a Swedish match but when that fell through a second candidate presented himself in the form of The Prince of Orange, who had been a widower since 1558.

William was 11 years older than her, and the marriage negotiations would last over a year. William was born Lutheran, but a condition of his inheritance stated that he had to be a Catholic and fears arose that any children he and Anna would have would be raised as a Lutheran. Things were eventually settled, and they were married on 24 August 1561 in Leipzig.

Five children were born from this marriage, but things would soon turn sour. After her eldest son Maurice died in infancy, Anna fell into a depression and supposedly had suicidal thoughts. She also began to drink excessively. Just three of their children would live to adulthood, and like William’s first wife, Anna would be left alone a lot. She became more and more annoyed living under the watchful eye of William’s mother Juliana of Stolberg. She complained to anyone who would listen.

In 1568, Anna had gone to Cologne on her own, but she soon fell into debts, and she requested more money as she had brought quite a fortune to the marriage. Her dowry had fallen into Habsburgs hands and had not yet been reclaimed by her husband. By the time things were settled, she and her husband were ordered to go to Erfurt, but Anna had different plans. Anna had fallen in love with her legal advisor, Jan Rubens. They were not careful enough, and things were soon found out. Jan was arrested in March 1571, and he confessed, but we do not know if he confessed under torture. Anna denied the affair but by August 1571 she was obviously pregnant, and she gave birth later that month to a daughter, who would be known as Christina von Dietz.

Though Anna and Jan should’ve faced the death penalty, her husband needed Anna’s influential family, and he wanted to keep the whole affair a secret. Anna would have to wait for a year and a half to find out what her fate would be. In the meantime, her mental state deteriorated. She drank, fought with the servants, and suffered from extreme mood swings. By the end of 1572, she was ordered to Castle Beilstein where she was put under house arrest. She was given religious books to read, and the only one allowed to visit was a Lutheran priest. She wrote several letters to her husband, but he never responded.

By 1575, William was hoping to marry again. He managed to secure a dubious annulment, and Anna was secretly brought back to Dresden. She was then locked in a room where the windows were bricked up, and food would be handed to her through a hatch. She had no contact with the outside world, and her mental state deteriorated further. We do not know exactly what she died of, but there are reports of ‘constant haemorrhaging’. She died imprisoned and alone – just 32 years old.

The post Princesses of Orange – Anna of Saxony appeared first on History of Royal Women.