Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 214

July 23, 2019

Ada of Huntingdon – A Scottish Princess as Countess of Holland

Ada of Huntingdon was born circa 1139 as the daughter of Henry of Huntingdon, a son of King David I of Scotland and Maud, Countess of Huntingdon, and Ada de Warenne. Her brothers Malcolm and William would later succeed as Kings of Scotland.

She probably married Floris III, Count of Holland sometime in 1162. She received the County of Ross in the Scottish Highlands as a gift for her wedding. Floris was around 30 years old at the time of the wedding. They went on to have at least ten children together: Dirk (future Count of Holland, Henry, Floris, William (another future Count of Holland), Ada, Sophia, Margaret, Elisabeth, Agnes and Baudouin. Her husband was quite politically active, but there is little evidence that Ada was. We know that she knew Latin as she borrowed two books from Egmond Abbey. Floris went on several campaigns with Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor.

Floris died during the Third Crusade on 1 August 1190, and he was buried in Antioch. She outlived her eldest son Dirk and was forced to flee with her son William and his wife Adelaide during the Loon War. We know that she died on 11 January, though the year is unknown, but it was definitely after 1206. She gave considerable funds to Middelburg Abbey, and it is likely that she was buried there.

Her great-great-grandson Floris V, Count of Holland, claimed the throne of Scotland in the Great Cause as her descendant.1

The post Ada of Huntingdon – A Scottish Princess as Countess of Holland appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 22, 2019

The Bonaparte Women: Elisa Bonaparte

Elisa Bonaparte was born Maria Anna on 3 January 1777 at Ajaccio, Corsica as the daughter of Carlo Buonaparte and Letizia Ramolino. She was thus a younger sister of Napoleon Bonaparte. She was given the name Maria Anna in honour of an elder sister who had died a few days after her baptism. She assumed the name Elisa later in life because she did not like the name Maria Anna. From now on we will use the name Elisa.

She attended the Maison royale de Saint-Louis at Saint-Cyr from 1784 until 1792 when her brother Napoleon brought her back with him to Ajaccio. These were scary times in France – it was in 1792 that the monarchy fell – and Elisa had no family in France. Shortly after, the school was closed. Elisa, her mother, and her sisters later went to live in Toulon and Marseilles, and her mother was eventually granted a small pension as a Corsican refugee. It was difficult for Elisa to adjust back to living with her family. By then, Napoleon’s star was on the rise in the army.

Elisa was given in marriage to a retired Corsican officer named Felix Baciocchi. They married in Marseilles on 1 May 1797. Her other brother Lucien was against the match and believed she could do better. Nevertheless, Baciocchi was a decent and accommodating husband, but he apparently lacked intellect. Elisa herself was also not the social success she was perhaps expecting to be. The Duchesse d’Abrantès said, “Never did a woman seem so utterly devoid of the charms of her sex; one would have said she wore a mask.” She also said, “Madame Baciocchi was never nice to her mother but who was she ever nice to? I have never known anyone with a sharper tongue!” Yet, as she was the sister of Napoleon, people gladly came to her salon. Their first child, a son named Felix-Napoleon, was born in June 1798 but he lived for only six months. Elisa’s marriage apparently soured quite quickly, and as her husband went on a mission to Spain with her brother Lucien, he wrote, “Madame Baciocchi was determined to be rid of her husband!” Meanwhile, Elisa went to Paris. In 1803, she was once again pregnant but her second son too lived for just one month. Elisa and her sisters carried Empress Joséphine’s train during her and Napoleon’s coronation at the Notre-Dame in Paris in 1804, and they were dismayed.

Elisa and her daughter (public domain)

Elisa and her daughter (public domain)When the Empire was proclaimed, and Napoleon became its Emperor, his sisters were initially not given any titles – to their displeasure. They complained to their brother of their “situation of inferiority”, and although he was reluctant, they were eventually created “Princesses” with the address of “Imperial Highness.” In 1805, Elisa was also given the State of Piombino as Napoleon considered it to be badly governed and she was recognised as the Princess of Piombino. Her husband was recognised as Prince of Piombino. Elisa was elated to have a Crown of her own though it did not take long for her to complain that it was “very small for her head.” She was then also given the Principality of Lucca. Elisa took up the reigns of her principalities – even inspecting her little army on horseback. Upon their solemn entry into the city of Lucca on 14 July 1805, their state coach was drawn by six bay horses, and Elisa wore a robe of white satin, heavily embroidered in gold. Their court at Lucca soon became famous for its erudition and refinement and also for its strict etiquette. During these years, Elisa finally gave birth to a child who survived – a daughter named Napoleone. Shortly after the birth, she was described by a courtier, “Her manner, and her way of doing things, are those of the Emperor, and I should be very surprised if her character was not similar to his. Since her confinement, she has put on weight. Her complexion is excellent; in a word she has become pretty.” In 1809, she was created Grand Duchess of Tuscany, and she did everything she could to make herself popular with the people. She began to tour the province, but despite her best efforts, the Tuscan nobility gave her the cold shoulder. In 1810, Elisa gave birth to a son named Jérôme but tragically, he died the following year.

Elise had fallen in love with the power, but it was not to last. She wrote to her brother, “Things in Italy are going badly. There have been some insurrectional movements, and brigands have appeared in the north. I shall leave the Grand Duchy only if the enemy should occupy Florence, and then I would withdraw via Piombino to the island of Elba, and wait there until matters improved.” Just as the tide was turning and the Grand Duchess was forced to flee, Elisa gave birth to a son named Frédéric, and according to a lady-in-waiting to Empress Joséphine, “at a moment when she ceased to have need of an heir.” Elisa was arrested by the Austrian at Bologna and escorted to Brünn as a prisoner of war. She wanted to establish herself in Rome, and she had no intention of joining her brother Napoleon in his exile. This was denied her, and she settled in Bologna under the name Countess of Campignano. The tragedies that had struck her family seemed to have impaired her health, and she contracted a nervous fever during archaeological work. She deteriorated quickly and died on 7 August 1820 in Trieste at the age of 42, shortly after imploring her brother Jerome to look after her husband. Her husband bought a chapel in Bologna where her ashes were to be deposited.

From his exile in Elba, Napoleon wrote of Elisa, “My sister, Elisa, has a masculine mind, a forceful character, noble qualities and outstanding intelligence; she will endure adversity with fortitude.”1

The post The Bonaparte Women: Elisa Bonaparte appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 21, 2019

Princesses of Orange – Wilhelmina of Prussia (2)

Wilhelmina of Prussia was born on 18 November 1774 as the daughter of King Frederick William II of Prussia and Frederika Louisa of Hesse-Darmstadt. Not much is known about her early life. She received an education in several languages, needlepoint and painting. She married her first cousin William, then Prince of Orange, on 1 October 1791 in Berlin, and it was considered to be a love match.

They first lived in The Hague at Noordeinde Palace, and it was there that she gave birth to her first child, William. The family’s following exile to England became even more tragic when she gave birth to a stillborn child just four months later. She left for Berlin a year later, and on 28 February, she gave birth to a second son named Frederick. He was followed by another stillborn son and two healthy daughters Pauline and Marianne, though Pauline would die at the age of six.

She triumphantly returned to the Netherlands in January 1814 as the wife of the future sovereign. In 1815, she officially became the first Queen consort of the Netherlands. Between 1815 and 1830 she lived in the four official residences in the Netherlands and Belgium – which at the time was still a part of the Netherlands. This union ended in 1830 when Belgium officially separated from the Netherlands. Their daughter Marianne married Prince Albert of Prussia, who was also Marianne’s first cousin and Wilhelmina visited them often.

Wilhelmina was a great lover of art, and she was taught by Friedrich Bury, though no work from her hand has survived. During her tenure as Queen, she was not a very visible Queen, and she liked it that way. She was considered to be a modest woman, which made her even more loved by the people. Her health began to deteriorate from the 1820s, but she still travelled. Her last journey was in the spring of 1837 when she went to Berlin for the baptism of her grandson. She died on 12 October 1837. She was interred in the royal crypt at Delft two weeks later.

Her husband married her former lady-in-waiting Henriette d’Oultremont, who was not only a Belgian but also a Catholic. The resistance to this marriage was so great that William decided to abdicate in favour of his eldest son. He did so on 7 October 1840. He married Henriette on 17 February 1841. William died just two years, but Henriette was awarded an allowance and a castle at Aachen, where she died in 1864.

The title ‘Prince of Orange’ was granted to her eldest son William, who went on to become King William II of the Netherlands. Since 1983, the heir apparent to the Dutch throne, whether male or female, bears the title of Prince(ss) of Orange.

The post Princesses of Orange – Wilhelmina of Prussia (2) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 20, 2019

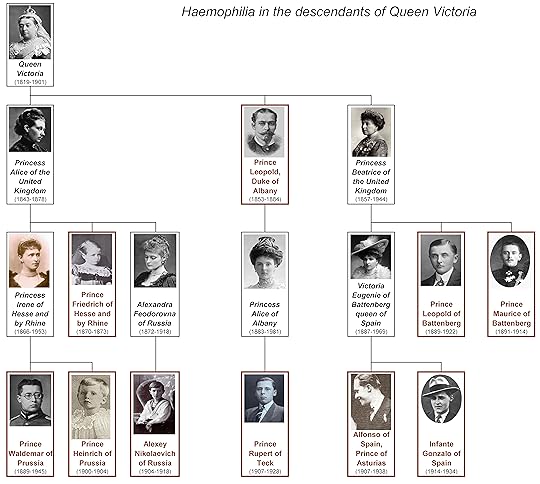

Queen Victoria and haemophilia

When the future Queen Victoria was born in 1819, no one knew that she was the carrier of a blood disease that would go down in history as the “royal disease.” Haemophilia was quite misunderstood in Queen Victoria’s day, and few haemophiliacs were expected to live to adulthood. Queen Victoria’s youngest son Prince Leopold turned out to have the so-called “royal disease” and Victoria lived with continuous guilt. She once wrote, “No one knows the constant fear I am in about him.” Yet at the time, it was thought he simply had weak veins or some kind of male menstruation. In 1891, researchers finally showed that the blood of haemophiliacs took longer to clot.

In addition to Prince Leopold, two of Queen Victoria’s daughters – Princess Alice and Princess Beatrice – carried the gene for haemophilia and passed it on. When Leopold began to walk, it was noticed that he bruised easily. Queen Victoria first mentioned a “defect” in a letter to the King of the Belgians on 2 August 1859 – there had clearly been a diagnosis though it is unknown if they were aware of the hereditary aspect. Victoria wrote, “Your poor little namesake is again laid up with a bad knee from a fall – which appeared to be of no consequence. It is very sad for the poor Child – for really I fear he will never be able to enter any active service. This unfortunate defect… is often not outgrown & no remedy or medicine does it any good.” He continued to have accidents and resorted to wearing a knee-pad. Leopold married Princess Helena of Waldeck and Pyrmont in 1882. They had a daughter named Princess Alice of Albany in 1883, and she too was a carrier of the gene for haemophilia, and she passed to her son Rupert who died in a car crash at the age of 20. Leopold died after suffering a fall in 1884, leaving behind a pregnant Helena. She gave birth to a son named Leopold Charles Edward George Albert a few months later. He did not suffer from haemophilia.

Princess Alice married the future Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse in 1862 and they went on to have seven children together. Of Alice’s two sons, one suffered from haemophilia and the two-year-old Friedrich died after a fall. Of her five daughters, two were definitely carriers- Alix, the future Tsarina of Russia and Irene, who married Prince Henry of Prussia – of the gene as they passed it on to their children.

Princess Beatrice married Prince Henry of Battenberg in 1885. Of their three sons, one was a haemophiliac, while their only daughter Victoria Eugenie was a carrier of the gene.

By Shakko – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

By Shakko – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia CommonsBut how did Queen Victoria end up with the haemophilia gene? Her father certainly wasn’t a haemophiliac, so it is likely to have been a spontaneous mutation of the gene. Tests on the remains of the Imperial Family of Russia (who were related to Queen Victoria through her daughter Alice) show that Victoria’s great-grandson the Tsarevich Alexei suffered from the relatively rare Haemophilia B, while his sister Anastasia was a carrier of the gene.1 However Queen Victoria came to be a carrier of the gene, it sure caused a lot of suffering.

The post Queen Victoria and haemophilia appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 19, 2019

Book News August 2019

Maria Romanov: Third Daughter of the Last Tsar, Diaries and Letters, 1908–1918

Hardcover – 20 August 2019 (US) & 30 June 2019 (UK)

In Maria Romanov: Third Daughter of the Last Tsar, Diaries and Letters, 1908–1918, by translator and researcher Helen Azar with George Hawkins, Mashka’s voice is heard again through her intimate writings, presented for the first time in English. The Grand Duchess was much more than a pretty princess wearing white dresses in hundreds of faded sepia photographs; Maria’s surviving diaries and letters offer a fascinating insight into the private life of a loving family—from festivals and faith, to Rasputin and the coming Revolution; it is clear why this middle child ultimately became a pillar of strength and hope for them all. Maria’s gentle character belied her incredible courage, which emerged in the darkest hours of her brief life. “The incarnation of modesty elevated by suffering,” as Maria was described during the last weeks of her life, she was able to maintain her kindness and optimism, even in the midst of violence and degradation.

Agrippina: The Most Extraordinary Woman of the Roman World

Hardcover – 6 August 2019 (US & UK)

In her own time, she was recognized as a woman of unparalleled power. Beautiful and intelligent, she was portrayed as alternately a ruthless murderer and helpless victim, the most loving mother and the most powerful woman of the Roman empire, using sex, motherhood, manipulation, and violence to get her way, and single-minded in her pursuit of power for herself and her son, Nero.

This book follows Agrippina as a daughter, born in Cologne, to the expected heir to Augustus’s throne; as a sister to Caligula who raped his sisters and showered them with honors until they attempted rebellion against him and were exiled; as a seductive niece and then wife to Claudius who gave her access to near unlimited power; and then as a mother to Nero―who adored her until he had her assassinated.

Through senatorial political intrigue, assassination attempts, and exile to a small island, to the heights of imperial power, thrones, and golden cloaks and games and adoration, Agrippina scaled the absolute limits of female power in Rome. Her biography is also the story of the first Roman imperial family―the Julio-Claudians―and of the glory and corruption of the empire itself.

The Royal Art of Poison: Fatal Cosmetics, Deadly Medicines and Murder Most Foul

Paperback – 22 August 2019 (UK & US)

For centuries, royal families have feared the gut-roiling, vomit-inducing agony of a little something added to their food or wine by an enemy. To avoid poison, they depended on tasters, unicorn horns and antidotes tested on condemned prisoners. Servants licked the royal family s spoons, tried on their underpants and tested their chamber pots.

Ironically, royals terrified of poison were unknowingly poisoning themselves daily with their cosmetics, medications and filthy living conditions. Women wore makeup made with lead. Men rubbed feces on their bald spots. Physicians prescribed mercury enemas, arsenic skin cream, drinks of lead filings and potions of human fat and skull, fresh from the executioner. Gazing at gorgeous portraits of centuries past, we don t see what lies beneath the royal robes and the stench of unwashed bodies; the lice feasting on private parts; and worms nesting in the intestines.

[no image yet]

The Mountbattens

Hardcover – 22 August 2019 (UK & US)

A major figure behind his nephew Philip’s marriage to Queen Elizabeth II and instrumental in the royal family taking the Mountbatten name, Dickie Mountbatten’s career included being Supreme Allied Commander of South East Asia during World War Two and the last Viceroy of India.

Once the richest woman in Britain and a playgirl who enjoyed numerous affairs, Edwina Mountbatten emerged from World War Two as a magnetic and talented charity worker loved around the world.

From the prize-winning and bestselling historian, Andrew Lownie, comes a nuanced portrayal of two very unusual people and their complex marriage to mark the 40th anniversary of Lord Mountbatten’s assassination by the IRA.

From British high society and the South of France to the battlefields of Burma and the Viceroy’s House, this is a rich and filmic story whose characters include all the key figures of the Second World War. From Churchill and Montgomery to Roosevelt and Eisenhower; the Royal Family, including the Duke of Windsor, George VI, the Queen, Prince Philip and Prince Charles; to Charlie Chaplin, Noel Coward, Salvador Dali, George Gershwin, Grace Kelly and Merle Oberon.

Princess: Stepping Out Of The Shadows

Paperback – 22 August 2019 (UK & US)

In the international bestseller, Princess: The True Story of Life Behind the Veil in Saudi Arabia, Princess Al-Sa’ud and the acclaimed author Jean Sasson began a remarkable series of books. Now, more than twenty-five years later, this compelling journey continues as we follow the fortunes and the dazzling life of the Princess, her friends and her family.

But, of course, there is a less glamorous, much darker side to this engaging series, and in Stepping Out of the Shadows Jean and the Princess focus their attention on how, despite positive news on civil rights reforms, Saudi women still suffer physical and psychological abuse and have little legal protection due to the archaic guardianship laws of the land. So, although this is a kingdom on the threshold of revolutionary change – change spearheaded by the young Saudi Crown Prince who is keen to modernize his country – any thoughts of equal rights and the chance to lead an independent life remain little more than dreams for most Saudi women.

Whilst the Princess acknowledges and welcomes the reforms that are on the horizon, through stories of joy and sorrow, we see how she is determined to continue to fight for equal rights for women in this, her beloved kingdom.

Pets by Royal Appointment: The Royal Family and Their Animals

Paperback – 8 August 2019 (UK) & 1 October 2019 (US)

The royal family say they can do without many things, but not their animals. For countless monarchs and their consorts, dogs, cats, horses and even the occasional parrot have acted as constant, faithful companions, unquestioning allies and surrogate children.

With intimate anecdotes and fascinating detail, royal expert Brian Hoey describes the mini palaces provided for the Queen’s pampered corgis; Princess Anne’s badly behaved bull terriers; the wild animals including crocodiles, hippopotami and an elephant presented to princes and princesses; a regal passion for all things equine; and the pigeon awarded a military medal for its efforts in the Second World War.

Royal Homes and Gardens

Paperback – 1 August 2019 (UK & US)

Britain has a wealth of royal palaces, some owned by the Crown as part of the country’s assets, while others have been bought by members of the Royal Family themselves as personal residences. Each property has a fascinating story behind it, as well as its own unique place in history. This beautifully illustrated book looks at some of the UK’s best-loved royal homes, current and former, their buildings, gardens, treasures and, of course, their inhabitants past and present. Discover how these homes have evolved over the centuries and how they are being adapted for the future and the demands of modern life. Written by seasoned Pitkin royal author Halima Sadat, this easily digestible volume makes a wonderful companion for anyone visiting these impressive buildings and their beautiful gardens. Entries include: Hampton Court, Osborne House, Windsor Castle, Kensington Palace, Buckingham Palace, Highgrove, Sandringham and Balmoral.

Dark History of the Kings and Queens of England

Hardcover – 14 July 2019 (UK) & 6 August 2019 (US)

Despite its reputation as the longest established in Europe, the history of the English monarchy is punctuated by scandal, murders, betrayals, plots, and treason. Since William the Conqueror seized the crown in 1066, England has seen three civil wars; six monarchs have been murdered or executed; the throne of England has been usurped four times, and won in battle three times; and personal scandals and royal family quarrels abound. The Dark History of the Kings & Queens of England provides an exciting and dramatic account of English royal history from 1066 to the present day. This engrossing book explores the scandal and intrigue behind each royal dynasty, from the ‘accidental’ murder of William II in 1100, through the excesses of Richard III, Henry VIII and ‘Bloody’ Mary, to the conspiracies surrounding the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1997 and the present-day troubles of Meghan’s family. Carefully researched, superbly entertaining and illustrated throughout with more than 200 colour and black-and-white photographs and artworks, this accessible and immensely enjoyable book highlights the true personalities and real lives of the individuals honoured with the crown of England – and those unfortunate enough to cross their paths.

The Tudor Kings and Queens: The Dynasty that Forged a Nation

Paperback – 15 August 2019 (US & UK)

Tudor Kings and Queens is the ideal, handy guide to what is a perennially popular era in British history. Beginning with the accession to the English throne of Henry VII, Alex Woolf guides the reader through a succession of monarchs, including the infamous King Henry VIII, Mary I, Edward VI and Elizabeth I, the Virgin Queen. Identifying the key moments of their reigns, from insurrections to their handling of foreign policy to their many marriages, Woolf reveals the ways in which these kings and queens governed their realm and the challenges they faced. It’s the perfect companion for anyone who enjoys historical drama and wants to know more about one of history’s most compelling royal dynasties.

Julia Augusta: Images of Rome’s First Empress on Coins of the Roman Empire

Hardcover – 13 August 2019 (US & UK)

Julia Augusta examines the socio-political impact of coin images of Augustus’ wife, Livia, within the broader context of her image in other visual media and reveals the detailed visual language that was developed for the promotion of Livia as the predominant female in the Roman imperial family.

The book provides the most comprehensive examination of all extant coins of Livia to date, and provides one of the first studies on the images on Roman coins as gender-infused designs, which created a visual dialogue regarding Livia’s power and gender-roles in relation to those of male members of the imperial family. While the appearance of Roman women on coins was not entirely revolutionary, having roughly coincided with the introduction of images of powerful Roman statesmen to coins in the late 40s BC, the degree to which Livia came to be commemorated on coins in the provinces and in Rome was unprecedented. This volume provides unique insights into the impact of these representations of Livia, both on coins and in other visual media.

Julia Augusta: Images of Rome’s First Empress on the Coins of the Roman Empire will be of great interest to students of women and imperial imagery in the Roman Empire, as well as the importance of visual representation and Roman imperial ideology.

Neslishah: The Last Ottoman Princess

Paperback – 20 August 2019 (UK) & 3 September 2019 (US)

Twice a princess, twice exiled, Neslishah Sultan had an eventful life. When she was born in Istanbul in 1921, cannons were fired in the four corners of the Ottoman Empire, commemorative coins were issued in her name, and her birth was recorded in the official register of the palace. After all, she was an imperial princess and the granddaughter of Sultan Vahiddedin. But she was the last member of the imperial family to be accorded such honors: in 1922 Vahiddedin was deposed and exiled, replaced as caliph–but not as sultan–by his brother (and Neslishah’s other grandfather) Abd lmecid; in 1924 Abd lmecid was also removed from office, and the entire imperial family, including three-year-old Neslishah, was sent into exile. Sixteen years later on her marriage to Prince Abdel Moneim, the son of the last khedive of Egypt, she became a princess of the Egyptian royal family. And when in 1952 her husband was appointed regent for Egypt’s infant king, she took her place at the peak of Egyptian society as the country’s first lady, until the abolition of the monarchy the following year. Exile followed once more, this time from Egypt, after the royal couple faced charges of treason. Eventually Neslishah was allowed to return to the city of her birth, where she died at the age of 91 in 2012. Based on original documents and extensive personal interviews, this account of one woman’s extraordinary life is also the story of the end of two powerful dynasties thirty years apart.

The post Book News August 2019 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 18, 2019

Empress Elisabeth’s Tattoo

Empress Elisabeth of Austria, perhaps better known as Sisi, has gone down in history as a formidable but complicated woman. One would perhaps be surprised to learn that the Empress had a tattoo of an anchor on her shoulder done in 1888 to represent her love undying love for the sea. Elisabeth abhorred the court in Austria and spent most of her time away from it, travelling around the world. During one of these trips to Greece, she had an anchor tattooed. Her husband, Emperor Franz Joseph, was less than amused by the tattoo and described it as a “dreadful surprise.”

Her love of the sea perhaps began in 1860 when Elisabeth went to Madeira as a treatment for pulmonary disease in the midst of a marital crisis. She was reportedly one of the very few people not seasick during the trip. In Madeira, she lived a quiet and solitary life in a rented villa by the sea.

In later life, she considered living in Greece and eventually had a villa built on Corfu. She also wished to be buried there according to her daughter Marie Valerie who wrote, “A marvellous spot, and if one knows Mama and knows what she needs in the way of beauty, wonderful climate, and quiet serenity for body and soul, one can only be happy about wonderful Gasturi and this spot! From the terrace, Mama showed me the view through two tall, dark cypresses to the open sea, this is the very place where she wants to be buried.”

When expressing her wish to visit America, she said, “What I would most like to do is go to America for a little while, the ocean draws me so much whenever I look at it. Valerie would like to go along, too, for she found the sea voyage charming. All the others with few exceptions were sick [on their current trip to the Isle of Wight].”

Even more dramatically, she wrote after the marriage of Marie Valerie, “I shall travel the whole world over, Ahasuerus shall be a stay-at-home compared to me. I want to cross the seven seas on a ship, a female ‘Flying Dutchman’ until I drown and am forgotten.” During one particularly stormy trip, Elisabeth tied herself to a chair on the deck and said, “I do like this Odysseus because the waves tempt me.”

It is perhaps only fitting that Elisabeth spent her final moments on board a ship after being stabbed. Her daughter certainly thought so, and she wrote, remembering something her mother had said, “And when it is time for me to die, lay me at the ocean’s shore.” Unfortunately, her wish to be buried by the sea in Corfu was not granted, and she lies in the Imperial Crypt next to her husband and son. 1

The post Empress Elisabeth’s Tattoo appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 17, 2019

Catherine Dashkova – Russia’s Enlightenment Princess (Part two)

In early 1762, Russian politics and Princess Dashkova’s life were both in a state of turmoil. Russia had a new Emperor, Peter III, who was the husband of Empress Catherine, Princess Dashkova’s close friend. As we learned earlier, though, Peter’s policies were deeply unpopular, and people were beginning to favour the idea of Catherine ruling as monarch in her own right.

For the time being, however, Princess Dashkova was trapped in a difficult situation. She had devoted herself to her friend Catherine’s cause, but Catherine’s husband and Princess Dashkova’s sister Elizabeth were caught up in an affair. Peter was determined to divorce his wife and supplant her with Elizabeth Vorontsov. Princess Dashkova tried as best she could to stay out of Peter and her sister’s circle but could not get out of some social events. At one event that Dashkova was forced to attend, Peter warned her “my little friend, you will take my advice; pay a little more attention to us…repent of any negligence shown to your sister.”

Peter’s reign continued with more and more unpopular policies. When he signed an ‘eternal alliance’ with Prussia and waged war on Denmark, a lot of people decided enough was enough. In July 1762, Peter decided to take a trip out of the country and visited Mecklenburg with many of his supporters. It was at this time that Catherine decided to listen to the opinions of her friends and overthrow her husband. On the 9th of July, the clergy was prepared to declare Catherine as the sole ruler of Russia, Empress Regnant; she also had widespread support from the public and the backing of the army. She rode in army uniform with her own 14,000 troops, and Princess Dashkova was by her side during the following days, sleeping next to her at night.

Peter III was captured and imprisoned at Ropsha under Catherine’s orders. It is not known what she planned to do with Peter in the long-term, but in the end, this problem was solved for her when Peter died at the hands of his Orlov guards after he had abdicated. His death was announced to have been caused by a stroke; Princess Dashkova had said: “It is a death too sudden, Madame, for your glory and for mine.” This was clear to Catherine, she had not ordered Peter’s death, but she had to at least make it look natural to protect her own reign.

With her best friend now reigning as Empress of Russia, Princess Dashkova expected to be by her side as a principal advisor. In reality, this could not happen, as Empress, Catherine had to limit the power of those around her. Princess Dashkova spoke openly about her ideas for reforms and policies and for the Empress this was a problem, the Princess could soon be at the head of her own faction and cause divisions at court. Empress Catherine had to limit her friend’s power.

This is not to say that Princess Dashkova was not rewarded for her part in the coup; Empress Catherine made her a lady-in-waiting and promoted Dashkova’s husband to the rank of colonel and rewarded the princess with thousands of rubles and a yearly pension. The couple were well-liked and resided in the Winter Palace where they dined with the Empress daily. This position meant that Princess Dashkova could be carefully watched by the Empress.

Over time as the Empress became busy with the daily running of the country, the pair’s friendship dwindled for some time, and it was reported across Europe that Dashkova was becoming a burden. In 1763, tensions were brought to the surface when Dashkova was implemented in a plot to murder the Orlov family. She was innocent in this, but the claims caused scandal. Princess Dashkova replied to the claims, “if the Empress wants to me lay my head upon a block as a reward for having placed a crown upon her own, I am quite prepared to die.” The Empress was furious at this and told Dashkova’s husband to bring his wife into line.

Princess Dashkova got on with life at court for the next few years until the death of her husband made her seek a change. The Princess received permission from the Empress to go travelling and set off on an extended trip around Europe. On her travels, she was warmly received at many courts and was able to meet many of the writers and philosophes she had studied for years. In Paris, she spent time with Voltaire and Diderot before travelling on to England and Scotland.

In Scotland, Dashkova spent several years in Edinburgh where she arranged for her son Pavel’s education. She then travelled to Ireland, back to London and then returned to Paris where she even met Benjamin Franklin. President Franklin was impressed with Dashkova’s ideas and education, and at the age of 37, she became the first woman to join the American Philosophical Society.

In 1782, Princess Dashkova returned to Russia after almost fifteen years of travelling. She was warmly welcomed back by Empress Catherine, and the pair rekindled their friendship. The Empress was impressed with Dashkova and believed she had promoted Russia well on her travels and that she could be useful in helping to continue Russia’s enlightenment transformation.

As soon as she got back, Dashkova was given the position of the Director of the Imperial Academy of Arts and Sciences. She was the first woman in the world to head a national scientific academy and was not even a scientist herself! Two years later she was awarded the post of President of the new Russian Academy where she oversaw the creation of a six-volume Dictionary of Russian languages.

Sadly upon the accession of Emperor Paul in 1796, Princess Dashkova lost all of the positions she had worked tirelessly in for over a decade, and she retired to Novgorod. The Princess continued to write in later life and worked on dramas on top of writing her extensive memoirs. In 1804, the Princess published her own memoirs before her death in 1810. These memoirs give a great insight into life at the Russian court and into the remarkable life of Princess Dashkova.

The post Catherine Dashkova – Russia’s Enlightenment Princess (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 16, 2019

From Queen Victoria to the Princess Royal – 17 July 1859

From Queen Victoria to the Princess Royal – Osborne, 17 July 1859

My first impression on hearing this dreadful news is to write to you!1 God has taken a pure, lovely angel to him! She was too good for this world, poor dear Pedro!2 He had found an angel to cheer his hard, trying life – his melancholy character – and now in a moment snatched from him! It is too dreadful! And the poor parents! Dear excellent Prince Hohenzollern! whom I do so honour and the poor delicate Princess – to think of their agony! To feel that his patriotism and devotion to his country prevented his going as he had intended in March to see her! What will his feelings be! Oh! I can’t tell you what I feel! I know what you will both feel – what your warm heart will feel! We who had brought about in a great manner this marriage, who had rejoiced at the happiness of both dear young people – married at the same age as ourselves – the same difference between their ages as between ours – married the year you did! And now all gone – crushed, shipwrecked! It is too, too dreadful! It makes my heart bleed! And we know nothing, heard nothing but that wretched telegram from good Louis3!4

The post From Queen Victoria to the Princess Royal – 17 July 1859 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 15, 2019

Princesses of Orange – Wilhelmina of Prussia

Wilhelmina of Prussia was born on 7 August 1751 as the daughter of Prince Augustus William of Prussia and Duchess Luise of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. Her brother eventually became King Frederick William II of Prussia. She barely knew her father because he died when she was just seven years old. She was raised mostly by her grandmother, Sophia Dorothea of Hanover and her aunt, Elisabeth Christine. One of her first governesses was abusive and neglected her often, and her family never realised. It must have been a relief when another governess replaced her.

Wilhelmina’s education was limited to religion, geography, history and French. She shared a household with her brothers Henry and Frederick William and Frederick William’s wife and their cousin Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Lüneburg. This setup ended rather suddenly when Henry died, and Elisabeth was disgraced after having an affair.

At the age of 16, Wilhelmina married 19-year-old William V, Prince of Orange. They met for the first time on the day of their wedding. Their first child was born in 1769, but tragically, the baby died at birth. A healthy daughter, Louise, followed in 1770. Wilhelmina again had a stillborn child in 1771. She gave then birth to two healthy sons in 1772 en 1774, William Frederick (William) and William George Frederick (Frederick). She was loyal to her husband, but their characters were mismatched.

By 1785, the country was on the brink of a civil war. The family left and headed towards Nijmegen. Wilhelmina took charge and on 28 June 1787, she took a small following to The Hague to plead William’s case. She was stopped and promptly arrested. She was taken to a farm where she was questioned and then escorted back. She was not allowed to continue her journey to The Hague and was eventually forced to return to Nijmegen. She demanded reparation for her mistreatment, and she was now supported by her brother, the King of Prussia. On 13 September, Prussian troops entered the Republic, and by October the country was back under control.

William and Wilhelmina were finally able to return to The Hague, and the people involved in her arrest were severely punished. However, her perceived harsh reaction made her unpopular, even with those in favour of their cause. However, more trouble was soon to come. In 1789, the French Revolution began, and by 1793, the French King and Queen had been guillotined and Wilhelmina’s cousin the King of Sweden had also been murdered. Wilhelmina began receiving death threats. In 1793, the French Revolutionary government declared war on William and the Dutch Republic was invaded by the French in the winter of 1794. Wilhelmina and her family were forced to flee to England on 18 January 1795.

Their shared exile was to last almost 20 years. Part of this time, they lived at Hampton Court Palace on an allowance from William’s cousin, King George III of Great Britain. Their eldest son left for Berlin while their second Frederick died in 1799 while in Austrian military service. Their daughter Louise married Hereditary Prince Charles George August of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel on 14 October 1790 and was now living in Brunswick. In 1801, her husband left to live in one of their properties in Germany, and she followed him there in 1802. Wilhelmina’s husband died on 9 April 1806. Wilhelmina went to live with her daughter Louise, who had also recently been widowed. The Napoleonic German expansion forced them to flee, and Louise and Wilhelmina went to Schwerin and Schleswig, where they spent the winter. They travelled on to Weimar and then to Berlin, arriving in late 1807.

The fall of Napoleon changed everything. Her eldest son William was welcomed back home as the Netherlands’ first sovereign. He returned to the Netherlands in November 1813. Wilhelmina and Louise followed him in early 1814. On 16 March 1815, William was proclaimed King William I of the Netherlands. Wilhelmina died on 9 June 1820, a year after her daughter Louise. She was interred in the crypt in Delft on 7 November 1822.

The post Princesses of Orange – Wilhelmina of Prussia appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 14, 2019

Lost Kingdoms: Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily began its life in 1130 when it was created by Count Roger II of Sicily with the agreement of Pope Innocent II.

Roger was married three times. His first wife was Elvira of Castile who was thus the first Queen of Sicily. They went on to have six children together, and Elvira died in 1135. He remarried in 1149 when he had outlived four of the five sons he had with Elvira. His second wife was Sibylla of Burgundy, but she died a year after their wedding giving birth to a stillborn child. In 1151, he remarried for a third time to Beatrice of Rethel. She was three weeks pregnant with a daughter named Constance when she was widowed. Roger left the throne to his last surviving son, now King William I of Sicily.

Henry VI and Constance (public domain)

Henry VI and Constance (public domain)William was married to Margaret of Navarre, and they had four sons together, though two would predecease their father. Though it was not a particularly happy marriage, Margaret was left to act as regent for their eldest surviving son upon her husband’s death in 1166. He became King William II at the age of 16. In 1177, he married Joan of England, daughter of King Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine, but they would not have any surviving issue. In 1184, William released his 30-year-old aunt Constance for the convent she had been confined in and married her off to the future Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor, perhaps in an attempt to secure the succession. Upon William’s death in 1189, he was succeeded by Tancred, Count of Lecce, an illegitimate grandson of King Roger II, who had the support of the Norman nobles.

Tancred had married Sibylla of Acerra and had six children by her. He crowned his eldest son co-King in 1193, and he became King Roger III. However, he died later that same year. Tancred died in 1194, and he was succeeded by his second son, still only a child, became King William III of Sicily. Meanwhile, Constance’s rival claim to the throne still loomed. Constance’s husband Henry marched on Sicily and dethroned the child King. His subsequent fate is unknown. Constance and Henry were now the King and Queen of Sicily. Constance was 40 years old and after nine years of marriage was pregnant for the first time. Knowing that many would doubt that the child was truly hers, she gave birth to her son in a tent in the market square, and she later returned to publicly breastfeed him. Constance died after a reign of just four years and was succeeded by her only child, the four-year-old Frederick. Her son also became Holy Roman Emperor in 1220 as Frederick II.

Frederick would leave both legitimate and illegitimate issue. His first wife was Constance of Aragon, who was 16 years older than him. They had one son named Henry together. Constance died in 1222 of malaria. In 1225, he remarried to Queen Isabella II of Jerusalem, and he became King of Jerusalem by right of his wife. Isabella gave birth to a short-lived daughter in 1226 and Isabella died in 1228 giving birth to a son – who survived – by the name of Conrad. She was still only 15 or 16 years old. In 1235, Frederick married for a third time – to Isabella of England, daughter of John, King of England and Isabella of Angoulême. They probably had at least four children but only one daughter – named Margaret – survived to adulthood. Isabella died in 1141 after giving birth to Margaret. Frederick also had at least three children – including a son named Manfred – with Bianca Lancia. Upon Frederick’s death in 1250, he was succeeded as King of Sicily by his second son Conrad, as his eldest son Henry had predeceased him. Conrad had already become King of Jerusalem upon his mother’s death.

Conrad had married Elisabeth of Bavaria in 1246, and they had one son named Conradin together. Conrad died after a reign of just four years as King of Sicily, and his young son Conradin became King of Jerusalem and King of Sicily under the regency of his uncle, Manfred. Tragically, Conradin would die in battle at the age of 16, leaving no issue. The heiress of the Kingdom of Sicily was his aunt Margaret, half-sister of his father, Conrad. Her son Frederick claimed Sicily by right of his mother. However, this claim was unpopular and his illegitimate uncle Manfred became King of Sicily.

Manfred married Beatrice of Savoy in 1247, and they had one daughter named Constance together. Beatrice was never Queen of Sicily because she died before her husband became King. He remarried to Helena Angelina Doukaina in 1259, and they went on to have at least five children before her husband was killed in battle in 1266. Manfred was defeated at the Battle of Benevento by a rival claimant named Charles of Anjou. Charles imprisoned Helena for the last five years of her life.

Charles had the support of the Holy See, but his hold on the Kingdom was tenuous. The island and the territories on the mainland were divided. Charles was married twice. His first wife was Beatrice of Provence, and they had at least six children together. She died a year after her husband became King of Sicily. In 1268, he remarried to Margaret of Burgundy, but their only daughter died in infancy. Upon Charles’s death in 1285, he was succeeded in the mainland territories (later better known as the Kingdom of Naples) by his son, now King Charles II of Sicily. On the island, he was succeeded by King Peter III of Aragon and his wife Constance of Sicily, the daughter of Manfred. We will follow the island line.

Constance and Peter had married in 1262, and they had six children together. Peter died in 1285 and was succeeded as King of Aragon by their eldest son, now King Alfonso III of Aragon. Alfonso died in 1291 without leaving issue and was succeeded in Aragon by his younger brother, now King James II. James also succeeded his mother as King of Sicily upon her death in 1302. James was married four times. His first wife was Isabella of Castile, but this marriage was annulled. His second wife was Blanche of Anjou, who gave him ten children. She died in 1310 shortly after giving birth to her tenth child. In 1315, he remarried to Marie of Lusignan, but this marriage remained childless. She died in 1319. In 1322, he remarried to Elisenda de Montcada. They too were childless, and she became a nun after her husband’s death. However, James made a peace treaty with Charles II, and he agreed to give up Sicily, but the Sicilians preferred James’s brother Frederick who became King Frederick III of Sicily.

Frederick married Eleanor of Anjou, the daughter of Charles, on the condition that the Kingdom of Sicily would revert Charles and his heirs after Frederick’s death. He and Eleanor went on to have nine children together, and he ruled the Kingdom of Sicily until his death in 1337. Despite the earlier treaty, he was succeeded as King of Sicily by his son, now King Peter II. Peter married Elisabeth of Carinthia, and they had nine children together. When Peter died in 1342, he was succeeded by his five-year-old son, now King Louis. He died in 1355 and did not leave issue. He was succeeded by his younger brother, now King Frederick IV.

Maria Carolina of Austria (public domain)

Maria Carolina of Austria (public domain)

On 11 April 1361, Frederick married Constance of Aragon, and they had one daughter named Maria together. Constance died in 1363 and Frederick remarried to Antonia of Baux, but she too died after just two years of marriage. Frederick did not remarry and died in 1377. Maria was only 13 years old when her father died, and she became Queen. The regency was held by several baronial families. In 1379, she was kidnapped by a Sicilian nobleman to prevent her marriage to the Duke of Milan. She was imprisoned for two years before being rescued by an Aragonese fleet. She was taken to Aragon in 1384 where she was married to Martin the Younger, a grandson of Peter IV of Aragon. Maria and Martin returned to Sicily and defeated the barons. Their only son named Peter died before his second birthday. Maria died in 1401, and Martin managed to rule Sicily alone. He remarried to Queen Blanche I of Navarre, but they had no surviving issue. Martin died in 1409 and was briefly succeeded by his father, King Martin II of Sicily (and Aragon). The second Martin now had no legitimate issue and his nephew Infante Ferdinand of Castile became King of Aragon and Sicily. Sicily followed the Kingdom of Aragon until the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, when by the Treaty of Utrecht, Sicily was ceded to the Duke of Savoy.

Victor Amadeus, Duke of Savoy and later also King of Sardinia, was married to Anne Marie of Orléans and they had nine children together, though only three survived to adulthood. The Kingdom of Sicily was invaded by the Spanish in 1718, and the Duke of Savoy ceded it to Austria in 1720 by the Treaty of The Hague. Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor was now also King of Sicily. His marriage to Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel produced two surviving daughters, Maria Theresa and Maria Anna. During the War of the Polish Succession, Sicily was conquered by Charles I, Duke of Parma, also known as King Charles III of Spain. Charles was married to Maria Amalia of Saxony, and they had 13 children together, though not all survived to adulthood. His third son Ferdinand succeeded him in Naples in 1759 when he abdicated in his son’s favour.

Ferdinand was married to Maria Carolina of Austria, the daughter of Maria Theresa. They had 18 children together, though not all survived to adulthood. Ferdinand and Maria Carolina were the last King and Queen of Sicily. In 1816, the Kingdom of Naples and the Kingdom of Sicily were merged as the new Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

The post Lost Kingdoms: Kingdom of Sicily appeared first on History of Royal Women.