Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 212

August 9, 2019

The royal monuments at St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle

St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle is perhaps the most impressive part of the entire complex at Windsor. The present chapel was begun by King Edward IV in 1475, and it’s the spiritual home of the Most Noble Order of the Garter. It was Edward’s wish to begin a Yorkist mausoleum there and it began with the burials of his children George and Mary. Over the years, more royals were buried with Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother and Princess Margaret being the last so far in 2002.

Embed from Getty Images

A visit to St. George’s Chapel is included in your ticket if you visit Windsor Castle. Below are some of the royal monuments that can be found inside the chapel. The monument for Princess Charlotte is especially touching.

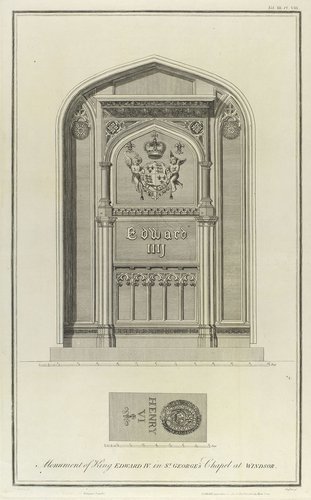

King Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville

The tomb of Henry VI is included in the image but is located near King Edward VII and Alexandra of Denmark. To the left of this is a plaque remembering Princess Louise of Saxe-Weimar, a niece of Queen Adelaide who died at Windsor Castle (not pictured)

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019King George V and Mary of Teck

Embed from Getty Images

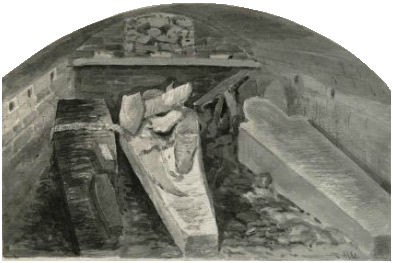

King Henry VIII, Jane Seymour, King Charles I and an infant child of Queen Anne

(Under the black marble plaque)

Embed from Getty Images

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019King George VI, Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon

Embed from Getty Images

Embed from Getty Images

King Edward VII and Alexandra of Denmark and King Henry VI nearby

Embed from Getty Images

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

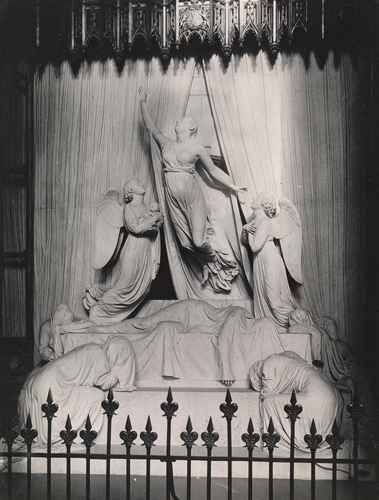

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019Monument to Princess Charlotte of Wales

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019The Gloucester Vault

Contains: Prince William, Duke of Gloucester (d.1805), Princess Maria, Duchess of Gloucester (d.1807), Prince William, Duke of Gloucester (d.1834) and Princess Sophia of Gloucester (d.1844) and Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester (d.1857).

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

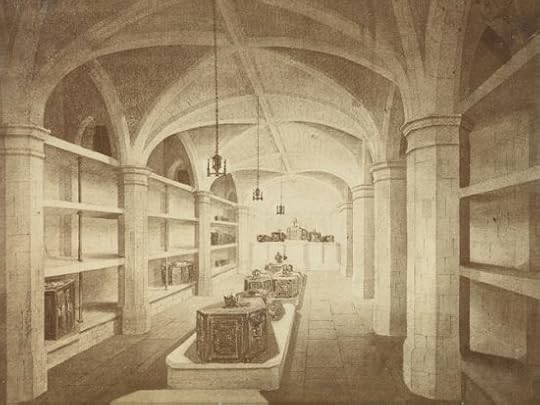

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019The Royal Vault

Contains: Princess Amelia, daughter of George III, Princess Augusta, Duchess of Brunswick, sister of George III, Stillborn son of Princess Charlotte, Princess Charlotte (daughter of George IV), Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, father of Queen Victoria, King George III, Prince Alfred, son of George III, Prince Octavius, son of George III, Princess Elizabeth, daughter of William IV, Prince Frederick, Duke of York, King George IV, Still-born daughter of Prince Ernest Augustus, son of George III, King William IV, Princess Sophia, daughter of George III, Queen Adelaide, wife of William IV, Prince Frederick of Schleswig-Holstein, son of Princess Christian, King George V of Hanover, Victoria von Pawel Rammingen, daughter of Princess Frederica of Hanover, Princess Mary Adelaide, Duchess of Teck, mother of Queen Mary, Prince Francis, Duke of Teck, father of Queen Mary, Princess Frederika of Hanover, Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, grandfather of Queen Mary, Princess Augusta, Duchess of Cambridge, grandmother of Queen Mary.

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019 Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019Prince Albert Memorial Chapel

Contains: Baroness Victoria von Pawel-Rammingen, daughter of Princess Frederica of Hanover, Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany and Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence.

Embed from Getty Images

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksThe post The royal monuments at St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 8, 2019

Adelaide of Cleves – Fighting for her daughter’s rights

Adelaide of Cleves was born on an unknown date as the daughter of Dietrich II, Count of Cleves and Adelaide of Sulzbach.

We know nothing about her youth and upbringing. She had two brothers and a sister. We know that she married the future Dirk VII, Count of Holland in 1186 and he succeeded his father as Count of Holland in 1190. The couple would go on to have three daughters: Adelaide and Petronilla (both deceased before 1203) and Ada.

Adelaide was the first of the Countesses to be referred to as Comitissa, instead of the usual “wife of.” She played a prominent part in the running of the county and was often a co-signer with her husband. It is thought that perhaps Dirk wanted to prepare her for a possible regency over their daughter Ada who was his heiress. Adelaide took charge in 1195 when the county was attacked from the north by Dirk’s younger brother, and Adelaide led the (successful) counter-attack from Egmond.

Dirk became ill in 1203 and Adelaide tried to quickly arrange for the marriage between Ada and Louis II of Loon. Dirk died before the wedding could take place, but the two were married before Dirk was even buried – Ada was then 15 years old. As expected, Dirk’s brother William refused to accept Ada as Countess and Adelaide could not prevent Ada being taken prisoner after being cornered near Leiden. Dirk’s brother styled himself as Count of Holland, but Adelaide also continued to use the title – despite not being able to do anything about Dirk’s brother.

Ada was initially imprisoned on the Island of Texel, but she was later shipped off to England, where King John ruled. William began ruling the county, though his reign was quickly overshadowed by a war with Ada’s husband Louis, which would last until 1206. The Treaty of Brugge ended the war and divided the county, though William effectively ruled all of it.

Louis finally managed to free Ada in 1207, under the condition that she give up her claim to Holland. He probably went to collect her himself. They didn’t keep to this condition, however, and the battle continued until 1213 when they were finally forced to give up their claim. Adelaide was surprisingly quiet during these years, though a letter exists from 1207 in which she begs King John to release Ada. We don’t even know where she was during these years.

She probably died around 1238 – even outliving Ada who had probably died around 1234. She was buried at Rijnsburg Abbey with other members of her family.1

The post Adelaide of Cleves – Fighting for her daughter’s rights appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 7, 2019

Irmingard of Bavaria – A Princess in a concentration camp

Whether we like it or not…our lives are determined to a certain degree not only by individual choices and circumstances but also by history…the history that happens around us, in our corners of the world and during our lifetimes. And the first half of the 20th century was – at least in Europe – a period that through its events and developments changed dramatically the destinies of so many people regardless of their social class, status, nationalities or religions. Royals were no exceptions to this and depending on the side of history, you or your family happen to be on in those times; you could live or die.

Princess Irmingard Maria Josefa of Bavaria is one such story. The girl with such an interesting name was born on 29 May 1923 at Schloss Berchtesgaden, the second child and eldest daughter of former Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria and his second wife Princess Antonia, born Princess of Luxembourg. She spent her childhood in the residences of her father, four former royal residences spread in Bavaria. Related to many royal houses of Europe, the little princess was supposed to enjoy a life of luxury and privileges, marry (when the time came) a prince or even a king and live happily ever after. But history had other plans.

As it often happens, one night can change everything. In Irmingard’s life, that night was the night of the “Beer Hall Putsch” of 8 November 1923, when Hitler attempted to seize power with the ostensible aim of restoring the Bavarian monarchy. Her father, the former Crown Prince Rupprecht, refused to lend his support, earning Hitler’s eternal enmity. In 1933, the Adolf Hitler became Chancellor, and it was the time for all his enemies to pay dearly for their opposition. Friends of the family were imprisoned; the King and Country League, the major monarchist group in Bavaria, was dissolved, and Crown Prince Rupprecht found himself excluded from public life. Taking the advice of his British relatives, the prince decided to send his children in England to avoid his son Henry being pressured to join the Hitler Youth or his daughters becoming members of the League of German Girls. He went into exile in Italy hoping that Hitler’s regime would not last for long. His wife and children joined him in 1940 as guests of King Victor Emmanuel of Italy, and they set up a house in Florence.

L-R – Irmingard, Gabrielle, Rupprecht. Sophie (on her father’s lap), Editha, Antonia, Hilda and Heinrich. (Public domain)

L-R – Irmingard, Gabrielle, Rupprecht. Sophie (on her father’s lap), Editha, Antonia, Hilda and Heinrich. (Public domain)Irmingard was sent to Padua to continue her studies, while the family was forbidden to return to Germany. But things would change again. After the unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Hitler in July 1944, Crown Prince Rupprecht went into hiding and eventually made contact with the Allies. The Nazis arrested Princess Antonia and her three youngest daughters in retaliation for the betrayal of their father. But Princess Antonia, who was suffering from typhus, was left in a hospital in Innsbruck while her daughters were transported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp at Oranienburg in Brandenburg.

In the meantime, Princess Irmingard was arrested while she was on holiday at Lake Garda. As she also contacted the typhus virus, she was sent to the same Innsbruck hospital as her mother. Eventually, the medical staff decided they were well enough to be transferred to Sachsenhausen. The princesses were later transferred to the concentration camps at Flossenbürg and Dachau, before being freed by the American Third Army on 30 April 1945. Their mother was discovered in a hospital in Jena in a terrible condition. She never recovered and died a few years later in Switzerland.

In 1950, Irmingard married her first cousin, Prince Ludwig of Bavaria and they had three children. She never talked about her experiences in the concentration camp, but unlike her mother who always refused to return to Germany, she decided to set up her home there in 1955, after having lived in Luxembourg with her husband for five years. She tried her best to give her children a normal life, and she tried to make peace with the past.

Maybe it is worth saying that her son, Prince Luitpold of Bavaria currently runs Kaltenberg, one of Bavaria’s most successful breweries. Princess Irmingard died on 23 October 2010, at the age of 87. She remains an example of dignity and resilience like so many others in her social class who had to pay for the courageous acts of their parents. And unlike another famous royal princess, Mafalda of Savoy who died in a concentration camp, she lived and found her way back to…life.

The post Irmingard of Bavaria – A Princess in a concentration camp appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 6, 2019

Princess Ilona of Liechtenstein has died at the age of 98

The Princely House of Liechtenstein has announced that Princess Ilona of Liechtenstein has died at the age of 98 on 2 August 2019.

Princess Ilona was born on 17 May 1921 in Sárosd, Hungary as Countess Esterházy de Galánth. Her first husband was Miklós Graf Cziráky von Czirák und Dénesfalva who died in 1944.

In 1977, she married Prince Constantin of Liechtenstein. It was also Prince Constantin’s second marriage. His first wife had been Maria Elisabeth von Leutzendorff whom he had married in 1941. They had one daughter together before Maria Elisabeth was killed in an air raid in Vienna in 1944.

A Requiem will take place on 16 August in the Cathedral in Vaduz. Princess Ilona will be interred in the Princely Crypt in Vaduz.

The Princely Family of Liechtenstein is quite large, and there are currently at least 53 men in the line of succession for the throne and women are currently barred from the succession. The Principality is ruled by Hans-Adam II, Prince of Liechtenstein, although his son Alois, Hereditary Prince of Liechtenstein, has acted as regent since 2004. The country is only 160 square kilometres, and it has a population of just 37,877.

The post Princess Ilona of Liechtenstein has died at the age of 98 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Princess Ilona of Liechtenstein has died at the age of 99

The Princely House of Liechtenstein has announced that Princess Ilona of Liechtenstein has died at the age of 99 on 2 August 2019.

Princess Ilona was born on 17 May 1921 in Sárosd, Hungary as Countess Esterházy de Galánth. Her first husband was Miklós Graf Cziráky von Czirák und Dénesfalva who died in 1944.

In 1977, she married Prince Constantin of Liechtenstein. It was also Prince Constantin’s second marriage. His first wife had been Maria Elisabeth von Leutzendorff whom he had married in 1941. They had one daughter together before Maria Elisabeth was killed in an air raid in Vienna in 1944.

A Requiem will take place on 16 August in the Cathedral in Vaduz. Princess Ilona will be interred in the Princely Crypt in Vaduz.

The Princely Family of Liechtenstein is quite large, and there are currently at least 53 men in the line of succession for the throne and women are currently barred from the succession. The Principality is ruled by Hans-Adam II, Prince of Liechtenstein, although his son Alois, Hereditary Prince of Liechtenstein, has acted as regent since 2004. The country is only 160 square kilometres, and it has a population of just 37,877.

The post Princess Ilona of Liechtenstein has died at the age of 99 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Inverness Castle and Mary, Queen of Scots

In 1562, Mary, Queen of Scots visited Inverness Castle – or rather she tried to. On 9 September the gates of the castle were closed to her by Alexander Gordon on the order of the 4th Earl of Huntly. Subsequently, Mary’s supported besieged the castle for three days until it finally fell.

Alexander Gordon was hanged for treason with his head being displayed on the castle. Mary herself stayed at Inverness from 11 until 14 September before moving on to Spynie Palace. “I never saw the Queen merrier – never dismayed; nor never thought I that stomach to be in her that I find. She repented nothing but (when the Lords and others at Inverness came in the morning from the watch) that she was not a man, to know what life it was to lie all night in the fields, or to walk upon the causeway with a jack and a knapsack, a Glowgow buckler, and a broadsword.”1

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksThe current red sandstone structure was built in 1836 by William Burn and it now houses the Inverness Sheriff Court. It is not open to the public but you can go inside the north tower of the castle which has a viewpoint at the top.

The post Inverness Castle and Mary, Queen of Scots appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Princess Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg’s last message

In August 1831, Princess Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg – the mother of Queen Victoria’s future husband Prince Albert – was dying. Her marriage to Albert’s father had ended in divorce in 1826 after she had allegedly committed adultery with Lieutenant Alexander von Haustein, who was created Count Pölzig when they married later that same year. Ernst himself had, of course, not been faithful to her either. Louise never denied or admitted to the charges and wrote to a friend, “I am to separate from the Duke… We came to an understanding and parted with tears, for life.” She later wrote, “Leaving my children was the most painful thing of all.” In March 1831, Louise and Alexander went to see a performance at the theatre, and she fainted after suffering a haemorrhage and had to be carried out.

She dictated a final message to her maid;

The feeling that my strength is sinking every hour and that perhaps this illness will end only with my death induces me to make one more request of my deeply beloved husband. If it is God’s wish to call me away in Paris, I wish my body to be taken to Germany, to my husband’s estate, in case he intends to live there in future. Should he choose another place, I beg to be taken there. I was happy to have lived by his side, but if death is going to part us, I wish my body at least to be near him.

She never recovered and died of uterine cancer on 30 August 1831. She had collapsed with Alexander in the next room. On 13 December 1832, she was buried in the churchyard at Pfesselbach, but she was moved 14 years later by her sons to the Ducal tomb in the Church of St Moritz in Coburg to lay by her first husband’s side in defiance of her last wishes.1

The post Princess Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg’s last message appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 5, 2019

The Year of Queen Victoria – Prince Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

On 6 August 1844, Queen Victoria gave birth to her fourth child whom they named Alfred Ernest Albert. The labour was long and gruelling, and her suffering was “severe.” Prince Albert was by his wife’s side throughout the labour. He would be nicknamed “Affie.” At the time of his birth, he was second in the line of succession behind his elder brother.

Soon Prince Albert was plotting the future. Four-year-old Victoria, Princess Royal would marry into the Prussian royal family, the Prince of Wales was, of course, to be King one day and Alfred… he would be Duke of Coburg one day if Albert’s brother Ernst did not produce any heirs. Alfred grew up as a favoured child of Queen Victoria, and she described him as a “sunbeam in the house” and “so like his precious father.”

Alfred was baptised by the Archbishop of Canterbury at the Private Chapel in Windsor Castle on 6 September 1844. His godparents were Prince George of Cambridge, the Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and the Prince of Leiningen.

At the age of 12, Alfred entered the Royal Novy, and he passed the examination in August 1858. He was then appointed as a midshipman on the HMS Euryalus, and a heart-broken Victoria wrote to her eldest daughter, “Papa is most cruel upon the subject. I assure you, it is much better to have no children than to have them only to give them up! It is too wretched!” When Prince Albert died in 1861, Prince Alfred was in Mexico with the navy, and he was not able to return home until February. In 1862, Alfred was chosen to succeed the childless King Otto of Greece, but this plan was blocked by the British government. Alfred remained in the navy for now and was promoted to lieutenant in 1863, to captain in 1866 and finally appointed to the command of the frigate HMS Galatea in 1867.

On 24 May 1866, Prince Alfred was created Duke of Edinburgh, Earl of Ulster, and Earl of Kent. He became the first member of the royal family to visit Australia in 1867, and he was received with great enthusiasm. However, during a visit to Sydney Prince Alfred was shot in the back and the bullet lodged in his abdomen. Alfred survived the attack though he later described not being able to breathe for three days. The assailant was caught and executed. Alfred returned home in June 1868. He continued to travel the world and visited Hawaii, New Zealand, Japan, India and Sri Lanka.

By 1870, Alfred was drinking heavily, and he was involved with a young woman in Malta when he was stationed there. On 23 January 1874, Alfred married Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia at the Winter Palace in St Petersburg. Queen Victoria refused to go and wrote, “I dislike now witnessing marriages, very much, and think them sad and painful, especially a daughter’s marriage.” Maria and Alfred returned home in March, but the marriage was not a happy one. Maria had expected precedence over the Princess of Wales and all of Queen Victoria’s daughters, but Queen Victoria refused her demands, granting her only precedence after the Princess of Wales.

Maria and Alfred would go on to have six children: Alfred, Hereditary Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1874 – 1899), Marie (1875 – 1938), Victoria Melita (1876 – 1936), Alexandra (1878 – 1942), unnamed son (1879 – 1879) and Beatrice (1884 – 1966). Alfred continued in the navy – finally being promoted to Admiral of the Fleet on 3 June 1893.

On 22 August 1893, Alfred’s uncle Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha died without an heir. Alfred’s elder brother had renounced his rights to the succession, and so Alfred became the new Duke. He retained Clarence House as his London residence, and though initially received coldly by the people, he gained popularity. In February 1899, Alfred’s only son died after shooting himself. He survived for two weeks, finally dying in Italy where he was sent to recover. Alfred himself would die the following year of throat cancer, just before his 56th birthday. He was the third of Queen Victoria’s children to die, and she cried out upon hearing the news, “My 3rd Grown-up child, besides 3 very dear sons-in-law. It is hard at 81!”

Alfred was succeeded as Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha by his nephew Charles Edward, the son of Prince Leopold, who would be the last ruling Duke.

The post The Year of Queen Victoria – Prince Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 4, 2019

Princesses of Orange – Catharina-Amalia of the Netherlands

After the death of his first wife, Sophie of Württemberg, King William III of the Netherlands remarried to Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont, but he was already King of the Netherlands, and she immediately became Queen and was never known as Princess of Orange. After King William III, the title was subsequently held by his sons William and Alexander. William was denied marriage to a mere countess, Matilde of Limburg-Stirum. There were rumours that it was not her low birth that had caused King William III to block the marriage, but that it was because Matilde was possibly the result of an affair he had with her mother. William could not possibly marry his half-sister. He decided to live in Paris after a Russian Grand Duchess also turned down an offer of marriage. He lived a licentious life in Paris and probably died of a combination of liver disease, typhoid and exhaustion, after which his title passed to his brother Alexander.

Alexander had been sickly from birth. He never married, and he became quite lonely after the deaths of both his mother and brother. He lived to see the birth of his half-sister Wilhelmina but died four later in 1884 – still only 32 years old. The Prince of Orange title had always been limited to men. So, even though Wilhelmina was now the heiress, she never carried the title in her own right. Wilhelmina became Queen in 1890 when her father died. She was still only ten years old and her mother Emma acted as regent for her. After Alexander’s death, it would be another 96 years before the title Prince of Orange was used again.

The current King of the Netherlands was born on 27 April 1967, and he became the Prince of Orange on 30 April 1980, when his mother Beatrix succeeded her mother as Queen. When he married Máxima Zorreguieta in 2002, she did not become Princess of Orange due to a recent change in the law, which limited the title to the heir apparent alone. On her wedding day, she was granted the titles Princess of the Netherlands and Princess of Orange-Nassau with ‘Her Royal Highness’ as the style of address. They had three daughters together, Catharina-Amalia was born in 2002, Alexia was born in 2005 and Ariane was born in 2007. When Willem-Alexander succeeded his mother on 30 April 2013, his eldest child automatically became Princess of Orange as the title no longer differentiated between a male or female heir. Catharina-Amalia is the first woman to hold the title in her own right, despite the Netherlands having had three Queens regnant before her. Mary of Baux did hold the title as sovereign Prince of Orange from 1393 to 1417.

Catharina-Amalia was born on 7 December 2003 at 5.01 PM in the Bronovo Hospital in The Hague. She was baptised on 12 June 2004 with Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden, Baroness Rengers-Deane, Prince Constantijn, Martin Zorreguieta, Herman Tjeenk Willink and Marc ter Haar as godparents. Her full name is Catharina-Amalia Beatrix Carmen Victoria. Catharina-Amalia and her sisters attend mayor functions, such as King’s Day and the press moments, but not much more. Catharina-Amalia’s first major function, as well as her sisters’, was their grandmother’s abdication and their father’s accession. Catharina-Amalia was just ten years old at the time. She has been attending a school like a regular child since 2007. She reportedly already speaks two languages, and she speaks some Spanish, no doubt taught to her by her mother! She will assume a seat in the Advisory Division of the Council of State of the Netherlands upon reaching the age of majority at 18 and is expected to become Queen regnant someday.

The post Princesses of Orange – Catharina-Amalia of the Netherlands appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 3, 2019

Princesses of Orange – Sophie of Württemberg

Sophie of Württemberg was born in Stuttgart on 17 June 1818 as the daughter of King William I of Württemburg and his second wife Catherine Pavlovna of Russia. Her mother died just seven months after her birth. She never grew close to her father’s third wife and new stepmother Pauline of Württemberg. She was very fond of her father, though. She was also close to her sister Marie because they were just two years apart in age. They were raised together by Russian and Swiss governesses. She was very well-educated and spoke several languages.

She married her first cousin William, future Prince of Orange and future King William III of the Netherlands in Stuttgart on 18 June 1839. She considered herself to be more intelligent than him and thought she could dominate him. She became Princess of Orange upon the abdication of King William I of the Netherlands in 1840. Her reception in The Hague was cold. Her new mother-in-law Anna Pavlovna had been against the marriage, though it’s not entirely clear why. The Russian Orthodox Church forbade marriages between first cousins. Perhaps Anna Pavlovna feared that her grandfather’s madness would be passed on with Sophie. Sophie did get on very well with King William I and his son Frederick.

Sophie and her husband William never got along. The births of their sons changed nothing. They had three sons, William in 1840, Maurice in 1843 and Alexander in 1851. William also had several affairs during their marriage, and he probably fathered at least a dozen illegitimate children. Sophie became Queen consort in 1849 when King William II died suddenly. By then, William and Sophie were on the brink of a separation. Their second son Maurice suffered from meningitis, and they quarrelled by his sickbed. Sophie wanted to consult another doctor but William refused. Maurice ultimately died of the illness. In 1855, they separated for good, but divorcing was not an option. William was given custody of their eldest son and Sophie was allowed to keep their youngest son Alexander until he was nine years old. Sophie would also have to continue to fulfil her duties as Queen.

From 1855, she lived mostly in Huis ten Bosch, and she went to visit her father almost every year. She was also a regular visitor to Emperor Napoleon III and his wife, Eugénie. She corresponded with intellectuals, who praised her. Historian John Lothrop Motley wrote, “The best compliment I can pay her is, that one quite forgets that she is a queen, and only feels the presence of an intelligent and very attractive woman.” She also held several seances with a psychic, probably to connect with her son Maurice. She was a patron of the women’s movement in the Netherlands.

Sophie died suddenly on 3 June 1877 of a heart condition at Huis ten Bosch. She left her personal property to her sons William and Alexander, but William died just two years later before becoming King. Sophie wore her wedding veil on her deathbed ass he believed that her life had ended on the day of her wedding. Perhaps mercifully, she never lived to see the deaths of both her other sons. Her husband King William III remarried just two years after her death in order to prevent a succession crisis. With his second wife, Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont, he had a daughter named Wilhelmina who would succeed him in the Netherlands as Queen Regnant.

The post Princesses of Orange – Sophie of Württemberg appeared first on History of Royal Women.