Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 208

September 7, 2019

Margaret of Prussia – The Emperor’s Sister (Part one)

Princess Margaret of Prussia was born on 22 April 1872 as the daughter of the future Frederick III, German Emperor and Victoria, Princess Royal. Her mother wrote to her grandmother Queen Victoria after her birth, “You may imagine how disappointed I was to have another little girl – if it had been a boy I should have hoped with you for it to have been the youngest forevermore, as really what one has to endure is too wretched but it would be wrong of me to complain, and for myself alone a little girl is much nicer, and she will be a companion for Sophie. Though you take no interest in babies, I may mention that this one has got an immense lot of dark hair, which I am sorry to think will not remain.”1 Queen Victoria wrote back, “I am most thankful to hear you going on so satisfactorily. I never thought you care (have 3 of each) whether it was a son or a daughter; indeed I think many Princes a great misfortune – for they are in one another’s and almost everybody’s way.”2 The new baby received the name Margaret Beatrice Feodora and Queen Victoria was delighted with the name of her half-sister writing, “Feodora is a dear name which I love to see repeated.”3

Margaret and her elder siblings – Wilhelm (1859 – 1941), Charlotte (1860 – 1919), Henry (1862 – 1929), Sigismund (1864 – 1868), Victoria (1866 – 1929), Waldemar (1868 – 1879), Sophie (1870 – 1932) – were brought up between the Palace at Unter den Linden in Berlin and the Neue Palais in Potsdam. Margaret received the nickname “Mossy”, and on her first birthday, her mother wrote to Queen Victoria that she was “such a little love – so forward, so pretty and so good.”4 Margaret’s mother was affectionate, but she also demanded excellence. She watched over their behaviour and their education.

Margaret joined her parents in England for the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria before going to San Remo with them. Her father was by then already quite ill, and he had been advised to spend the winter there. Her father succeeded as Emperor on 9 March 1888, but by then he was already unable to speak and dying of throat cancer. He died just three months later on 15 June 1888. Margaret could only watch as her brother, now Emperor Wilhelm II, had his mother’s desks searched for private correspondence. Her mother, now known as Empress Frederick, took her three youngest daughters to Bornstadt. Empress Frederick wrote to her mother, “I have my three sweet girls – whom he (her husband) loves so much – they are my consolation.”5 The following year, Margaret’s elder sister Sophie married the future King Constantine I of Greece and Empress Frederick was sad to see her trio break up. Empress Frederick brought her two youngest daughters to see Sophie’s first son, who was born the following year. Margaret was about to lose her last sister to marriage as Victoria was due to marry Prince Adolf of Schaumburg-Lippe. Margaret was now the sole unmarried child, and she remained as her mother’s companion for now.

Margaret had grown up into a beautiful young woman, and it was not believed that she would remain unmarried for long. She was linked to the Tsarevich of Russia, Crown Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria and the Duke of Clarence. Margaret herself was more interested in Prince Max of Baden, but then in 1892, Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse came knocking. The request of a proposal came as a shock to both her and her mother, but when the actual proposal came in June 1892, Margaret said yes. He was her third cousin, and it seemed likely that he would one day become Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel. Empress Frederick was sad to be losing her but wrote to her mother, “You can imagine how upset and agitated I am, although very thankful to think my own precious darling will be happy -though I shall now be left quite alone.”

On 25 January 1893, Margaret married Frederick Charles at the Stadtschloss in Berlin. Margaret “held herself so well and bore herself with such natural dignity and grace that everyone was charmed with her.” The newlyweds made their home at Schloss Rumpenheim, and Margaret soon found herself pregnant. Her first son was born a month early on 24 November 1893, and he was named Friedrich Wilhelm. Just 11 months later, she gave birth to a second son named Maximilian. Empress Frederick had missed both births because they were early, so she came even earlier for the third pregnancy. Margaret gave birth to twin boys on 6 November 1896 – they were named Philipp and Wolfgang.

On 22 January 1901, Queen Victoria died, and it was Margaret’s task to break the news to her mother – who was already very ill with spinal cancer. Margaret’s last pregnancy was once again twin boys and Richard and Christoph were born on 14 May 1901. Empress Frederick died on 5 August 1901 at Schloss Friedrichshof. Margaret had been appointed her literary executor, and she had been left Friedrichshof and most of its contents. To maintain it, Margaret and her family moved in, and English nannies were employed for their six boys. English remained a dominant language in their lives. Philip and Wolfgang were sent to be educated in England in 1910 and Margaret used the opportunity to visit family. She would often visit England and always enjoyed a cordial relationship with her cousins there. Shortly after the death of King Edward VII Margaret wrote, “I wish for nothing more than to go to dear old England again this year although it will be very sad, but how delightful it would be to see you all again. One can still hardly realise the King’s death, it all came too suddenly.” Margaret was in England when the Great War loomed in 1914, and she returned home on one of the last ships to leave England. Less than a week later, the war was declared on Germany.6

Part two coming soon.

The post Margaret of Prussia – The Emperor’s Sister (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 6, 2019

Marie of Brabant – From Empress to Countess

Marie of Brabant was born circa 1290 as the eldest daughter of Henry I, Duke of Brabant and Maud of Boulogne. For a long time, she was the eldest of four daughters, and so it would seem that she might one day succeed her father as Duchess of Brabant, making her quite the catch. A younger brother named Henry was finally born in 1207, followed by Godfrey in 1209.

In 1198, Marie was betrothed to King Otto IV of Germany, later Holy Roman Emperor but when her father changed sides to a rival King, the betrothal fell through. The rival King was assassinated in 1208 and Otto became Holy Roman Emperor the following year, but he was not keen to renew the marriage alliance and instead married Beatrice of Swabia, his late rival’s daughter. Beatrice was only 14 years old and died just weeks after her wedding, leaving Otto free to marry again. He married Marie on 19 May 1214 at Maastricht. However, his reign as Holy Roman Emperor was to be short and he was deposed in 1215. Marie joined her husband in retirement, where he quickly became seriously ill. He died on 19 May 1218 – their fourth wedding anniversary. They had not had any children. Marie returned to the court of Brabant.

She remained a widow for two years and remarried in 1220 to William I, Count of Holland. He too had been widowed in 1218 – his first wife was Adelaide of Guelders. This was considered to be a mismatch by many contemporaries due to Marie’s high rank with one calling it an “unbelievable humiliation.” This marriage would be short as well, and William died just two years later. It appears that they too did not have any children, as all of his children are traditionally attributed to Adelaide. Marie was still only 30 years old but would not remarry. She outlived her second husband by 38 years. In 1224, her younger sister Mathilde married her stepson Floris IV, Count of Holland.

Marie remained active in her widowhood, and her father even sent her to negotiate political differences. When her father died in 1235, Marie was granted the fortress in Helmond, where she settled. During her later year, she found a convent near Helmond. The fortress where she lived burned down in 1250, and she was involved in its rebuilding. Marie died in 1260 between 9 March and 14 June. She was buried in the St. Peter’s Church in Leuven.1

The post Marie of Brabant – From Empress to Countess appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 5, 2019

The Year of Queen Victoria -The Famine Queen

In 1900, Irish activist Maud Gonne referred to Queen Victoria as the ‘Famine Queen’. This nickname stuck as Irish Nationalism, and a quest for independence from the United Kingdom gained traction. Before this, while British laissez-faire capitalist policies were often blamed for the extent of the devastation felt during the famine, the Queen herself had not been so widely and outrightly blamed for it. In this article, we are going to take a brief look at what happened during the Great Famine in Ireland and at why the British Government and Queen Victoria are often blamed for the sheer number of famine related deaths.

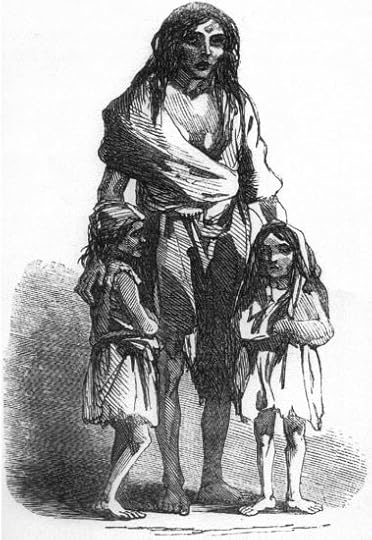

(public domain)

(public domain)Ireland in the 1800s was no stranger to famine. So, when potato blight struck in 1845, it was widely believed by politicians in Westminster that the issue would soon blow over. However, this did not happen, and the Great Famine destroyed Ireland between 1845 and 1852. A quarter of the population died or had no choice but to emigrate in a mass exodus which left the Irish population in decline for almost a century. Even today the population is less than the pre-famine figure.

Ireland in this time was part of the United Kingdom and was ruled from Westminster. Though Ireland was represented in a way by Irish MPs and Lords, they often lived in England and were out of touch with the Irish people. The land was owned by the English or wealthy Protestants by the time of the Great Famine, meaning the majority of the Catholic population had to rent small plots of land from these wealthy absentee landlords. Land rental was expensive, and the plots were small and so Irish tenant farmers often relied on crops like the potato to survive. On top of this, there were a large number of landless labourers who had to find farm work when they could or sublet smaller plots.

Despite the failure of the potato crops over a number of years, there were some larger farms which did produce foods during the famine, but these were grains that were often sold abroad as the Irish people could not afford to buy them. The Irish blamed the Queen and her ministers for allowing precious oats, wheat and cattle to be sold overseas especially to the English. The government at the time were very wary of interfering with the free market and so allowed the food to be sold while people starved to death rather than subsidising the cost of the food for the poor. Here we can see that the Irish anger at the British was understandable.

By the time the British government took notice of what was happening and tried to intervene, people were already dying in droves. There were many different schemes which aimed to help the Irish, with varying results over the years. The Queen and her cabinet were often blamed when the schemes failed or when no help was provided to certain regions. Due to a largely agrarian economy and a lack of government presence in Ireland, people relied on aid and intervention from England and from their Protestant landlords who owed allegiance to Queen Victoria.

Robert Peel, the Prime Minister, did try to help as much as possible in the early years of the famine. He introduced Public Works to allow the landless poor to do jobs to earn a small amount of money, and he also imported corn from America for people to eat. Under Peel’s government, the Corn Laws were repealed in and aimed to bring down the price of bread and grains for the people, but Peel’s weak government soon fell. With the loss of Peel also came the loss of any progress that was being made by the British government to help the starving Irish. People often had to turn to charities to receive food from soup kitchens which could never meet the demand, or if all else failed, people piled into the diseased workhouses which were at ten times their usual capacity.

Peel, the charities and the workhouses are seen as the things that at least tried to help the Irish people during the famine even if they often failed. Peel’s successor Lord John Russell and the civil servant and Treasurer Charles Trevelyan, however, are often seen as purposefully holding back help from the Irish. If these men who were Queen Victoria’s Prime Minister and Treasurer were seen as so badly failing the people during the Irish famine, then how can the Queen be blameless?

Under Russell’s government, the Public Works did continue for a while, but they were poorly managed. Charles Trevelyan, it seems had no wish to help the Irish people, he said the famine was “a direct stroke of an all-wise and all-merciful Providence”. Here he reflected the view of many British politicians that the famine was sent by God to get rid of the poor Irish who were a burden on the state. In 1846, Trevelyan stopped many of Peel’s relief programs, and the Labour Rate Act was introduced, meaning help was only given to the very worst affected areas, and it was never enough. Trevelyan blamed the Irish gentry and landlords for the devastation caused and convinced the government that the Irish should deal with the problem themselves. This brought a lot of aid to a standstill during the worst of the famine years.

From letters, it is clear to see that although Queen Victoria did visit Ireland four times during her reign, she had little interest in Ireland and felt disconnected from her Irish subjects. Historian Christine Kinealy says of Queen Victoria “There is no evidence that she had any real compassion for the Irish people in any way”. We also know that the Queen only campaigned for funds to be raised for Ireland after Russell told her to do so. The Queen did not donate money herself until 1848, and when she did donate £2000, it meant to nobody else could donate more money than she had done. This meant that when foreign rulers tried to send large sums of money, they were not allowed to do so.

It is unfair to blame Queen Victoria for the extent of the deaths and emigrations caused by the Irish famine. However, it is not acceptable to say that she and her government completely innocent. It is clear that the Queen did not care much for her Irish subjects and that on many occasions, her government was negligent. During the famine, The Times reported that Ireland was “a mass of poverty, disaffection, and degradation without a parallel in the world.” Queen Victoria clearly knew what was happening, and without a doubt, she could have done more, and if the famine had struck England or Wales instead, there would have been a very different outcome.

The post The Year of Queen Victoria -The Famine Queen appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 4, 2019

Helene in Bavaria – The almost Empress

Helene had expected to make the most brilliant match of all until the man she was supposed to marry fell in love with her younger sister Elisabeth.

Helene was born on 4 April 1834 as the daughter of Maximilian Joseph, Duke in Bavaria and Princess Ludovika of Bavaria. She would grow up to be the opposite of her famous sister. While Elisabeth enjoyed hunting and riding, Helene sat quietly with her embroidery. This often worried her mother, who believed her eldest daughter to be too serious. Her sense of duty, however, would be perfect for a future empress.

A letter from their aunt Sophie, the mother of Emperor Franz-Joseph I of Austria, would change everything. Her son was in need of a bride and marriages between cousins were not uncommon. Ludovika was delighted with the idea that her eldest daughter would become Empress of Austria. Duke Max was not asked because everyone knew of his dislike of his sister-in-law. The letter did cause some panic, though. Helene, though beautiful and dutiful, had received very little formal education and how was she going to make up for it in such a short period of time? Tutors were quickly hired to teach Helene the basics of French and dancing. Sophie considered her to be the perfect match for her son – except for one thing: she was habitually late.

The letter invited the women to Bad Ischl, and Helene would return home as a spurned bride. Helene, already prone to depression, became even more withdrawn. She began to go to church on a daily basis, and Ludovika began to fear that Helene would want to take the veil. Helene threw herself into charity work and was cheered wherever she went. Her mother remained determined to find her a match – before she was too old.

We don’t know when Ludovika noticed Maximilian Anton Lamoral, Hereditary Prince of Thurn and Taxis but he probably attended a hunt organised by Duke Max. Ludovika hosted a dinner to which Helene was also invited. Cupid did the rest, and on 30 March 1858, Duke Max wrote to the Prince’s father, “I can only wholeheartedly assure you that this marriage will make me very happy, especially as Helene will join the family of a man of whom I have long been a sincere and devoted friend.” There was one problem; however, the bridegroom was not of equal rank. Helene’s cousin, King Maximillian II of Bavaria, had to be persuaded to allow the marriage and he wrote on 2 May 1858 that she should retain the rank and rights of a Princess and a Duchess with Royal Highness to lead. The wedding was scheduled for 24 August 1858, just three days after Elisabeth gave birth to Crown Prince Rudolf. Nevertheless, many of the Imperial relations came to Possenhofen to celebrate the wedding, including Ludovika’s half-sister Caroline Augusta, Dowager Empress of Austria. The heavy rains that day could not dampen the festive mood.

Bild-PD-alt via Wikimedia Commons

Bild-PD-alt via Wikimedia CommonsTheir honeymoon was spent at Biederstein, and the newlyweds even went to visit the Imperial family at Bad Ischl, where her new husband got along well with the Emperor – both enjoyed hunting. Their entry into Regensburg was meticulously planned, and she was welcomed warmly by her new family. Helene cared much for the concerns of her people and devoted her time to charity work. Helene now found herself at the centre of one of the wealthiest courts in Europe. She was soon pregnant with her first child, though the birth of a daughter – named Louise – on 1 June 1859 was a disappointment to the family. A second daughter – named Elisabeth – was born on 28 May 1860.

Then a letter arrived from the Emperor asking Helene to accompany her sister to Corfu, possibly for many months, as the Empress recovered from an illness. Though at first unsure about the request, one can hardly refuse the Emperor and so Helene travelled south. Her husband accompanied her part of the way and on 18 August 1861; she boarded a train that would take her to Trieste – saying goodbye to her husband. Elisabeth was thrilled to have her sister with her on Corfu. Helene soon learned all about Elisabeth’s unhappy life at the Austrian court and was soon counting the days for her return to Regensburg. Sooner than expected, Helene bid her sister farewell and returned home.

On 24 June 1862, Helene gave birth to a son and heir – named Maximilian Maria. Not much later, her husband moved their official residence to the city itself and called it the “Erbprinzen-Palais.” They moved there in 1863. When her brother Karl Theodor was set to marry Princess Sophie of Saxony in 1865, the daughter of King John of Saxony, all the siblings were invited. Helene and Elisabeth agreed to meet in Prague to spend a few days together before the wedding.

Helene’s own marriage had been happy, but it was soon apparent that her husband was seriously ill. When Helene was pregnant for the fourth time in 1866, he quickly deteriorated and when their second son – named Albert – arrived on 8 May 1867 no one could deny the physical decline. His doctors desperately tried to save his life with several cures he had to drink, but it was no use. He died in his beloved Erbprinzen Palais on 26 June 1867, still only 35 years old. The Emperor granted the guardianship of the children to Helene, which was surprising given his conservative views. Her father-in-law also saw a talent in Helene, and she was slowly educated to lead the house. Helene remained devout, and she spent an hour at her husband’s mausoleum every morning. When her father-in-law passed away in 1871, her eldest son became the 7th Prince of Thurn and Taxis at the age of 9.

Though her lands were profitable, Helene became more restless and lonely as she grew older. Her second daughter Elisabeth married Miguel, Duke of Braganza and her first grandchild Prince Miguel of Braganza, Duke of Viseu was born the following year. Two more grandchildren – Prince Francis Joseph of Braganza and Princess Maria Theresa of Braganza – followed before tragedy struck once more. Elisabeth had grown weak from having given birth to three children in quick succession, and she died on 7 February 1881, still only 20 years old. Helene had prayed for her daughter, but no amount of prayer could have saved her – Helene was devastated. With her two sons away at school and her eldest daughter Louise having married her childhood friend Prince Frederick of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen in 1879, Helene became even more lonely.

Helene also began to search for a suitable bride for her eldest son, but his heart had been weakened by a childhood illness. He died on 2 June 1885 as the bells of Regensburg tolled in mourning for their beloved prince. Once more, Helene was called upon for a regency, this time for her younger son Albert, now the 8th Prince of Thurn and Taxis. Helene was deeply depressed by the death of her son and travelled to Paris to visit her sister Sophie Charlotte. She then invited Elisabeth to visit England with her. It took two years before Helene was able to emerge from her deep mourning. Albert had grown up during this time and helped his mother where he could. Her regency lasted until his 21st birthday in 1888, and in the meantime, her health had begun to seriously decline, and she was diagnosed with stomach cancer. Albert sent a telegram to his aunt in Vienna and Elisabeth hurried to Regensburg.

Elisabeth arrived just in time to say goodbye. Elisabeth’s daughter Marie Valerie wrote in her journal, “Aunt Néné … was glad to see Mama and said to her, ‘Old Sisi’ — she and Mama almost always spoke English together. ‘We two have had hard puffs in our lives,’ said Mama. ‘Yes, but we had hearts,’ replied Aunt Néné.” On 16 May 1890, Helene died, still only 56 years old. She was buried in the family crypt in Regensburg. The current head of the House of Thurn und Taxis is her great-great-grandson.1

The post Helene in Bavaria – The almost Empress appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 3, 2019

The Franziskaner-Klosterkirche ruins in Berlin

The Franziskaner-Klosterkirche was founded in 1250 as a monastery church. It evolved over the years but was closed during the Reformation in 1539. The monastic buildings are gone now but the church continued to evolve.

The church was destroyed during the bombing of Berlin on 3 April 1945. The ruins were not secured until 1959 and some of it was demolished to may way for the park around it. Restorations in 2003 now allow it to be used by the neighbourhood for exhibitions and concerts.

Click to view slideshow.

Somewhere on the grounds are the remains of Margrete of Denmark, the daughter of King Christopher II of Denmark, and Louis II, Elector of Brandenburg and his wife Kunigunde of Poland, the daughter of Casimir III of Poland and his first wife, Aldona-Anna of Lithuania. Unfortunately, there is very little on the site itself, except about the bombing, and the site is closed off outside of events.

The ruins are easy to visit as the Klosterstrasse U-bahn station is right across the street.

The post The Franziskaner-Klosterkirche ruins in Berlin appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 2, 2019

Lady Mary Victoria Douglas-Hamilton – The absent Princess

The daughter of our Scotch duke will become a sovereign princess. Her future Kingdom, it is true, is scarcely as extensive as is one of her brother’s estates, but, nevertheless, the Principality has maintained its independence for many centuries. The fair and amiable Lady Hamilton is the Emperor’s cousin.

Lady Mary Victoria Douglas-Hamilton was born on 11 December 1850 as the daughter of William Hamilton, 11th Duke of Hamilton and his wife, Princess Marie Amelie of Baden.

Maria Caroline, the dowager Princess of Monaco, was most keen to see her grandson, Albert, the Hereditary Prince of Monaco, marry into the British royal family. When this turned out to be an impossible dream, she turned to Napoleon III, Emperor of the French, who suggested another option – his second cousin Lady Mary Victoria. This was an offer she could not refuse. Albert was less enthusiastic and promptly sailed off on a yacht for a three-month cruise. Lady Mary Victoria was also less than amused at the prospect, and they hadn’t even met yet. When Albert returned home, a marriage contract was drawn up.

On 21 September 1869, the wedding took place at the private chapel at the Château Marchais. The Emperor and Empress of the French were supposed to attend, but the Emperor had fallen ill. Their wedding gifts more than made up for their absence; Lady Mary Victoria received an emerald and brilliant bracelet, a diamond thistle brooch and a suite of sapphires. She wore a white satin gown, designed by Worth, with a white tulle veil and a 16-feet-long train. She wore a pearl tiara. Over the course of the day, she would change three times. During the signing of the marriage contract, she wore pink poult-de-soie with a demi-train and a pouf just below the waist. After the ceremony, she wore a blue gown trimmed with velvet. Albert soon found he had little in common with his glamorous wife and he wrote he found her, “sadly deficient in even the most basic of common knowledge.”

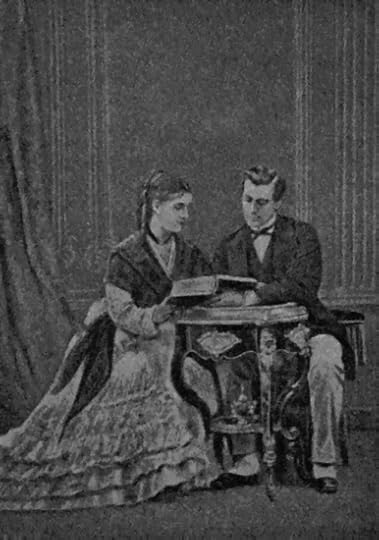

(public domain)

(public domain)After attending the Paris Autumn Races, they went on a honeymoon to Baden-Baden in the black forest. They arrived in foul weather and as a war between France and Prussia lay looming. Mary Victoria discovered she was pregnant and was soon in bed with severe morning sickness. They returned to Monaco in even worse weather and to a Palace in mourning for Albert’s uncle, Wilhelm, 1st Duke of Urach. His devastated aunt Florestine dominated the princely palace to the horror of her mother, Maria Caroline. In January 1870, Mary Victoria’s mother planned to return to Baden-Baden, and Mary Victoria wanted to go with her. Albert was almost glad to see her go, and he refused to accompany her. Maria Caroline did see the danger ahead and wrote to Mary Victoria, “My dear Mary, my grandson’s grief has so saddened me that I’m writing directly to you to make an appeal to your heart. Can you not forgive Albert for what you reproach him with [not being attentive enough]? The tender love you have aroused in him will give him the strength to change his ways, he has assured me, and to do all he can to make you happy… I’m sure that for your part, my dear Mary, you must feel that a wife is the link of her family…” Mary Victoria wrote back, “My dear grandmother. I was greatly touched by your letter, and I thank you for all its affection for me. The best memory I have of the recent sad time is the kindness you showed towards me. I am most grateful for this memory, which eases the bitterness of the weeks I spent at Monaco…” Saying no more, Mary Victoria continued her travels towards Baden-Baden. On 12 July 1870, she gave birth to a son who was christened Louis-Honoré-Charles-Antoine. Albert did not go to see his son and instead signed up with the French Navy as the war was declared.

For five years, Albert and Mary Victoria did not have any contact though she did write to Maria Caroline. Mary Victoria had fallen passionately in love with a dashing Hungarian Count named Tassilo Festetics de Tolna. She refused to see her husband and applied to the Vatican for an annulment of their marriage. Albert, though shocked, agreed to this but it would take another four years before all the financials matters were settled. Their son was also a future Prince of Monaco and Albert insisted that he should be educated in France. On 28 July 1880, the Vatican finally annulled their marriage while declaring their son legitimate. Mary Victoria had already moved on and had married her count in June, despite going against church law. She was already carrying his child. They would go on to have four children: Mária (born 1881), Georg (born 1882), Alexandra (born 1884) and Karola-Friederika (born 1888).

They spent part of the year on her husband’s estates in Hungary and also often visited France. On 21 June 1911, her husband was made a Prince with the style Serene Highness by Emperor Franz-Joseph I of Austria – making Mary Victoria a Princess once more.

Albert and his son were never close. Albert’s great-grandson Baron Christian de Massy later said, “Albert despised Louis… He poured upon him all of the ill-feeling he had for Lady Douglas-Hamilton, whom he never forgave for the humiliation she had caused him by fleeing in the middle of the night, nor for his doubts about his son’s origins. The fact that Louis did not in the least resemble Albert had never helped.”

Mary Victoria died on 14 May 1922 at the age 71, and she was buried in the family mausoleum on the Festetics Palace estate. Her son would succeed as Prince of Monaco just one month later.1

The post Lady Mary Victoria Douglas-Hamilton – The absent Princess appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Queen Mother Helen of Romania to be reburied in Romania

The remains of Queen Mother Helen of Romania, born Helen of Greece and Denmark, will be repatriated to Romania in October. Helen will be laid to rest with her son King Michael I of Romania – who died in 2017 – at the new Archdiocesan and Royal Cathedral.

Helen died in exile in Lausanne, Switzerland. She had spent most of her life living in Italy, but when she became older, she moved to Lausanne to be closer to her son’s family. She died on 28 November 1982 at the age of 86 and was buried without pomp in the Bois-de-Vaux Cemetery. In March 1993, the State of Israel gave Helen the title of Righteous Among the Nations in recognition for her actions during the Second World War towards Romanian Jews.

The post Queen Mother Helen of Romania to be reburied in Romania appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 1, 2019

Kensington Palace – Victoria: A Royal Childhood & Victoria: Woman and Crown

At Kensington Palace in the early hours (4.15 am) of 24 May 1819, Alexandrina Victoria was born to Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, and Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (the Duchess of Kent), as Her Royal Highness Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent.

For Queen Victoria’s bicentenary, Kensington Palace plays host to two exhibitions about her life. The first, Victoria: A Royal Childhood focuses on her childhood and features such things as the room where Victoria was born, her dolls and the hallway where she first met Prince Albert. The second, Victoria: Woman and Crown focuses more on her family life with items such as etchings of her children, a locket containing Prince Albert’s hair and her Urdu journals.

Victoria: A Royal Childhood

Click to view slideshow.

Victoria: Woman and Crown

Click to view slideshow.

Both exhibitions are equally fabulous but the Victoria: Woman and Crown exhibition is created in much smaller rooms, making it a bit harder to navigate. The Victoria: A Royal Childhood is located in the rooms that were actually lived in by Queen Victoria and her mother, giving it a little something extra. I particularly enjoyed seeing the reconstruction of the room where she was born. The exhibition is also accompanied by a wonderful publication called The Young Victoria by Deirdre Murphy.

The exhibitions are included in the admission price. Victoria: Woman and Crown is currently set to end on 6 January 2020 while Victoria: A Royal Childhood currently has no end date. I would highly recommend a day at Kensington Palace. You simply cannot miss these exhibitions. Get your most recent info for visiting here.

The post Kensington Palace – Victoria: A Royal Childhood & Victoria: Woman and Crown appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 31, 2019

Blanche of Valois – The French Queen of Bohemia

Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia married four times. His first wife was Blanche of Valois. They both met as children at the French court. The marriage of Blanche and Charles was one of four royal marriages that tied the Bohemian royal family to the French royal family in the 14th century.

Early Life in France

Blanche was born around 1316, as the youngest daughter of Charles, Count of Valois, and his third wife, Matilda of Chatillon. Blanche’s father was a French prince – he was the second son of Philip III, King of France. Blanche’s name at birth was Margaret, but she was always called Blanche, allegedly because of her fair hair. In 1323, John of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia, sent his eldest son, Wenceslaus to the French court for his education. There he was renamed Charles after the French king at the time, Charles IV. From then on, the Bohemian prince was known by his new name.

The French and Bohemian royal families already had a connection – the previous year, King Charles married Marie of Luxembourg, the sister of John. As the King’s first cousin, Blanche would have spent much of her time with Marie. When Blanche and Charles of Bohemia first met in 1323, they were both about seven years old. That same year they were betrothed. In 1324 Marie gave birth prematurely to a son after she was involved in a carriage accident. Both she and her son died. Despite this, the ties between France and Bohemia remained in place. King Charles married again but had no surviving sons. When he died in 1328, the French crown went to Blanche’s older half-brother, Philip, as Charles’ closest living male relative. This caused Blanche’s status to grow even more.

Marriage with the Bohemian heir

After the betrothal, Blanche lived with her mother until 1330, when she left for Luxembourg to join Charles. Soon afterwards, Charles was called by his father to campaign in Northern Italy. Blanche remained in Luxembourg for the next four years, while Charles was in Italy.

Finally, in 1334 Charles returned to Bohemia. Blanche would join him there on 12 June of that year. She was warmly welcomed by the nobility, clergy, and citizens of Prague. A month after her arrival, most of the people who accompanied Blanche on her journey returned to France. It was possibly a move to avoid disputes with the Bohemian courtiers. Blanche quickly learned both Czech and German, so she could communicate with the people in her new country.

Blanche quickly became pregnant after her arrival, and in May 1335, she gave birth to a daughter named Margaret. Blanche was said to have been very popular in Prague. She was admired for her beauty and introduced her new homeland to the latest French fashions. However, her life could not have been very easy. She seems to have had a difficult relationship with her father-in-law, John. In 1336, John brought his new bride, Blanche’s second cousin, Beatrice of Bourbon, to Prague. Beatrice was always compared unfavourably to Blanche. Blanche knew Czech, but Beatrice did not. Possibly due to a falling out with John or Beatrice, Blanche and her daughter moved to Brno in 1337. Brno was located in Moravia, a different region of Bohemia. As heir to the Bohemian throne, Charles held the title Margrave of Moravia. Blanche stayed there for the next several years.

Blanche seems to have returned to court by 1342, which was also the year that her second daughter Catherine was born. By then, Beatrice of Bourbon had left Bohemia. That same year, a marriage between Louis I of Hungary, and Blanche’s elder daughter, Margaret was contracted. It was finalized in 1347.

Queen of Bohemia

John was killed in the Battle of Crecy on 26 August 1346. This event made Charles and Blanche the new King and Queen of Bohemia. Even before John’s death, Charles was elected King of the Romans in opposition to Holy Roman Emperor Louis IV. Charles and Blanche were crowned as King and Queen of Bohemia on 2 September 1347 at St Vitus Cathedral in Prague. For this event, a new coronation code for the Kings and Queens of Bohemia was written. New crowns were made for the ceremony. In the 1980s, a golden crown that probably belonged to Blanche was found in the Sroda Treasure.

One month after the coronation, Emperor Louis IV died, and now Charles could take more steps to becoming Holy Roman Emperor. Charles finally reached the imperial title in 1355. However, Blanche did not live long enough to become Holy Roman Empress. She died on 1 August 1348 in Prague, after a brief illness, aged 32. She is sometimes thought to have died from the bubonic plague, but it did not reach Bohemia until two years later. Blanche was buried in the St Vitus Cathedral.

Charles, who was still in need of a son, remarried to Anne of Bavaria less than a year after Blanche’s death. Blanche did not enjoy her status as Queen for long, but Charles never forgot his first wife. Blanche and Charles knew each other since childhood, and some believe that out of his four wives, Blanche was the one he loved the most. Thirty years later, near the end of his life, Charles made one last visit to France. There he met with Blanche’s sister, Isabella, Duchess of Bourbon. They were said to have talked about Blanche and wept at her memory.1

The post Blanche of Valois – The French Queen of Bohemia appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 30, 2019

Diana, Princess of Wales is remembered at Kensington Palace

People have gathered outside Kensington Palace to pay tribute to Diana, Princess of Wales, who died 22 years ago in Paris. Tributes were being left at the gates of the palace including flowers and balloons.

Embed from Getty Images

Embed from Getty Images

Embed from Getty Images

Embed from Getty Images

In the summer of 1997, Diana began a relationship with Dodi Fayed, and she joined his family in the south of France. On 31 August 1997, Diana, Dodi Fayed and their driver were killed in a crash in the Pont de l’Alma tunnel in Paris. They had been hounded by paparazzi, and the driver had lost control of the car at high speed while intoxicated. Her funeral service on 6 September was watched by millions. She was buried on an island within the grounds of Althorp Park.

The post Diana, Princess of Wales is remembered at Kensington Palace appeared first on History of Royal Women.