Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 216

July 6, 2019

Catherine Dashkova – Russia’s Enlightenment Princess (Part one)

The princess was born as Catherine Romanov Vorontsov in 1743 but for the purposes of this article, we will mainly call her by her married name of Princess Dashkova to differentiate from her friend Empress Catherine. Princess Dashkova’s parents were Count Roman Vorontsov and his wife Marfa who were closely involved with the Russian royal family. The sources on the princess’s family are sparse and not in agreement on the number of siblings she had, but it appears that she was the third of four children. Elizabeth was her older sister, followed by a brother Alexander and a younger brother called Semyon was born in 1744. All of the siblings made their mark on Russian history.

When Catherine Vorontsov was just two years old, she lost her mother and it seems her father lost interest in his children. Of her father, the Princess said he was “a man of pleasures not much occupied with the care of his children”. This early childhood neglect turned into an advantage for the princess who was sent off to live with her uncle Michael, the Imperial Chancellor, who provided her with the highest standard of education. Even as a child, Princess Dashkova would stay up late devouring the works of Voltaire and Bayle and she excelled especially in languages. It was clear from early on that the young girl was gifted.

At the age of fifteen, the Princess met the Grand Duchess Catherine who delighted in finding an equally intelligent young woman to converse with. The young princess was bored by gossip and parties and refused to wear makeup or ornate dress which made her stand out from her contemporaries. The Grand Duchess was impressed with the Princess’s knowledge of Enlightenment philosophes and the pair spoke to each other in French. The princess began to see the Grand Duchess as an idol from then on.

Within a year the Princess was married, her husband was Prince Michael Dashkova who was a high ranking and wealthy officer. The couple moved away to Moscow where they had three children in very quick succession. Princess Dashkova felt quite isolated in Moscow as her Russian was poor and many of her husband’s family spoke no foreign languages. During this time the Princess studied Russian further and devoted her time to reading.

In 1761, it was clear that the life of Empress Elizabeth was nearing its end and the Grand Duke Peter, the husband of the Princess’s friend Grand Duchess Catherine was officially proclaimed heir to the throne. It was at this time that the Dashkovas returned to St Petersburg and the Princess became more aware of how terrible a ruler Peter would be. Peter was rude and ill-tempered, he loved to play childish pranks and spent his time partying. He also undermined the current Empress Elizabeth by sending military tip-offs to Prussia to assist them, despite Russia being Prussia’s opponent in the war. In doing so, Peter was breaking his alliances with Austria and France and forging new ones in secret with Frederick II of Prussia. On top of this, Peter boasted of his plans to restructure the Russian Orthodox Church and the army once he became Emperor.

Most embarrassingly of all for Princess Dashkova, however, was the fact that Peter kept a mistress whom he openly flaunted at court. He discussed replacing his wife the Grand Duchess Catherine with this rival. The mistress was Princess Dashkova’s sister Elizabeth. Understandably Princess Dashkova was mortified by this and stayed out of Peter and Elizabeth’s social circle, siding with Catherine. Princess Dashkova was one of the few people who would speak their mind to Peter and the pair often bickered publically. On one occasion Peter and Princess Dashkova debated over the death penalty while at a meal together; Dashkova prevailed and Peter just mocked her and stuck out his tongue. Dashkova gained a lot of respect for this.

While spending time together in Finland over the summer, Princess Dashkova began to see Catherine as the solution to the problem of Peter being the heir to the throne. She saw her as a saviour of the nation and wrote in her memoirs that Catherine had “captured her heart and her mind”. Princess Dashkova became very protective of Catherine and even reported to her the goings-on of her sister Elizabeth and Peter, Catherine’s husband.

As Empress Elizabeth lay dying the political atmosphere was intense. The Empress had wished to defeat Prussia in her lifetime, but her heir Peter was sending them information to undermine the attacks before the Russian generals even knew the information. The powerful Orlov family began to rally support for Catherine; she was a powerful woman after all and mother to Paul the future heir. As support rallied around her, Catherine became more and more withdrawn and hid away from the public. At this time she was six months pregnant but not by her husband Peter, the child was Gregory Orlov’s. This scandal had to be covered up and was even hidden from Princess Dashkova when she came to visit the Grand Duchess to see if she had come up with a plan. It was clear that Catherine did not see herself coming to power as a ruler in her own right and due to her pregnancy, she could plan little for even her own safety. It is reported that Princess Dashkova said that their friends must act for Catherine and proclaimed “I have enough courage and enthusiasm to arouse them all”.

On Christmas day 1761, the Empress passed away and Peter and Catherine were proclaimed the new Emperor and Empress of Russia. In the following months, Catherine grieved publically for Empress Elizabeth and gained the respect of the Russian people. Peter, however, began to roll out immense changes in the church and the army which were deeply unpopular. Princess Dashkova and Catherine’s other supporters knew they had to act soon to help to topple Peter and make Catherine Empress in her own right.

Read part two to find out what happened next and to see what happened later in Princess Dashkova’s life. (Coming soon)

The post Catherine Dashkova – Russia’s Enlightenment Princess (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

From Queen Victoria to the German Empress – 7 July 1888

From Queen Victoria to the German Empress – Windsor Castle, 7 July 1888

How well I know that feeling when the months change and the year. I have now been a widow four years and half more than I was a wife. And I had hoped for a year or two, and more, to be taken to join him! After a time the sense of being of use to others made me wish again to live on. For your three dear girls’ sakes, you must struggle on bravely. Why had you to give up the uniform which your darling husband wore? Is it a rule? When I had to give up Orders and things, I had them (replicas) made and kept the originals.

I am sorry you could not keep his little pet dogs. The two little ones here are looking very well and growing nicely. They are under the special kind care of the Taits. Is there any bust of darling Fritz1 you like and any cast of his dear hands? I thought both existed. I shall be too glad to contribute to the building of the addition to the Friedenskirche (at Potsdam). Those receptions must be cruel but the veil is a great comfort. We have terribly wet weather almost like tropical rains. Would the small sum I mentioned be of any use for the purchase of what you mention (a house of her own). Is Bornsted a private property?

Oh, how dreadful is the thought that all goes on and we remain alone, as you so truly say. We shall stay here till the 17th and then go to Osborne. How, oh how small I think of last year! Here and at Frogmore where he came to tea or to breakfast, how I thought of him and of you all! I have just had a letter from darling Arthur, who had heard by telegram the dreadful news three days before. I send you again Lord Rosslyn’s sonnets, written by himself and with some difficulty, as he has a numbness in one hand, I don’t know why. I still hope and pray that this controversy between the doctors may not be pursued further.2

The post From Queen Victoria to the German Empress – 7 July 1888 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 5, 2019

A possible reburial for Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut?

The Historische Kring Voorhout (HKV) wants to rebury Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut in the cemetery of the Maartenskerk in Sint-Maartensdijk, according to the Countess’s last wishes. She is currently buried in the court chapel in the Binnenhof in The Hague with other family members.

She was born in the castle of Le Quesnoy in Hainaut on 16 August 1401. She was the only daughter of William II, Duke of Bavaria and Margaret of Burgundy. Jacqueline was famously married four times.

Her first marriage was to John, Duke of Touraine, fourth son of Charles VI of France and Isabeau of Bavaria. He was not expected to rule in France. They married on 6 August 1415, when Jacqueline was only 14, in The Hague. However, that same year John became the new Dauphin of France after the death of his elder brother. The marriage was short. John died two years later on 4 April 1417. A mere two months later, Jacqueline’s father also died.

Jacqueline was acknowledged as the sovereign of Holland, Zeeland and Hainaut, but her uncle John III, Duke of Bavaria-Straubing, claimed them as his rightful inheritance. To make her position stronger, Jacqueline decided to marry again. She married her cousin John IV, Duke of Brabant, but he proved a bad choice. He gave John III full custody over Holland and Zeeland for 12 years. It was decided that the marriage should be dissolved.

In 1422 Jacqueline obtained a dubious divorce from John IV of Brabant to allow her to marry Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, who was a brother of Henry V of England. Jacqueline had hoped for help from Humphrey, but he was not recognised in Holland and Zeeland as count. He eventually had to return to England, and he had to leave Jacqueline behind. In 1425 she was imprisoned in Ghent by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy. She escaped from Ghent dressed in men’s clothes. During this time the pope decreed that she was still married to John IV, Duke of Brabant and that her marriage to Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester was invalid. John IV had died a year before the decree, however.

In 1428 Jacqueline was forced to agree to a peace treaty that basically took away all her lands, but she was allowed to keep her titles. Philip the Good was also her heir if she died without children and she was not to marry without the permission of her mother, Philip and the three counties. Philip did not abide by this peace treaty; however, and in 1433, Jacqueline ended up giving him all her land and titles, and in return, she was to have an income from several estates. Her financial situation before this had been dire.

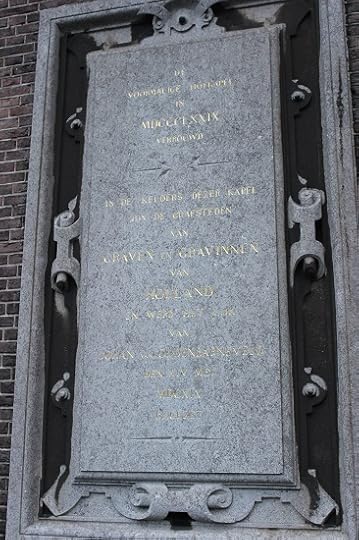

Plaque outside the Court Chapel – Photo by Moniek Bloks

Plaque outside the Court Chapel – Photo by Moniek BloksJacqueline retired to her lands in Zeeland, and this is where she met her fourth husband, Francis, Lord of Borssele. They married in 1434. Supposedly it was a love match. It was to be a short marriage. Jacqueline became ill in 1436, and she died a few months later. She died in Teylingen Castle on 8 October 1436. She had no children.

The Binnenhof in The Hague is due to be remodelled, and according to the HKV, this would be the best time to grant the Countess’s final wish. However, it is unknown which bones are Jacqueline’s as the tombstones have been moved over time and after extensive renovations the court chapel currently houses offices. One solution would be to DNA-test the bones and match them to a braid currently housed in the Rijkmuseum that is said to belong to Jacqueline.

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Nothing is certain yet, and so Jacqueline will, for now, remain buried in The Hague.

The post A possible reburial for Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut? appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Princesses of Orange – Amalia of Solms-Braunfels

Amalia of Solms-Braunfels was born as the daughter of John Albert I, Count of Solms-Braunfels and Countess Agnes of Sayn-Wittgenstein on 31 August 1602. She grew up at the Palatine Court at Heidelberg. When Frederick V and Elizabeth Stuart were elected as King and Queen of Bohemia, Amalia travelled with them to Prague as the new Queen’s lady-in-waiting. The Bohemian quest for the crown ended after a year, and Amalia joined them on their flight through Europe. They finally settled in the Hague.

It was in The Hague that Amalia met Frederick Henry of Orange, a younger son of William, Prince of Orange, from his fourth marriage to Louise de Coligny. At the time the Prince of Orange was Maurice, a son from William’s first marriage to Anna of Buren. However, Maurice was unmarried, and he pressured his younger brother to get married to secure the dynasty. Frederick Henry and Amalia had been involved since 1622, but she had refused to become his mistress. They finally married just before Maurice’s death in 1625. The courts of Elizabeth Stuart and Amalia of Solms-Braunfels were soon in competition. The women were often painted in a similar fashion as they would employ the same painter.

Amalia commissioned the building of Huis Ten Bosch, and its main Orange hall would eventually be completely dedicated to the life of Frederick Henry. Reportedly, Amalia and Frederick Henry had a happy marriage. Though Frederick Henry had fathered an illegitimate son before his marriage to Amalia, no illegitimate children were born during his marriage. He had nine children with his wife, though only five of them would live to adulthood. Amalia became quite ambitious in trying to arrange suitable marriages for her children, and she was successful, too. Her only son William married the eldest daughter of King Charles I of England, Mary, Princess Royal. She forced her daughter Louise Henriette to marry Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg, even though she was in love with Henri-Charles de la Tremoille, Prince of Talmant.

Amalia became more politically active as her husband began to suffer from gout and something that was most probably Alzheimer’s disease. He died in 1647 and was succeeded by their son William, now William II, Prince of Orange. William would die just three years later of smallpox. His only son, yet another William, was born a week after his death. His mother Mary initially retained custody of her son, but Amalia was not pleased with this at all. When Mary died in 1660, Amalia began to care for William. Amalia was known to be an intelligent woman, though she would continue to write her letters in phonetic German and French.

Amalia died on 8 September 1675, and she did not live to see her grandson William become King of England. She was buried in the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft.

The post Princesses of Orange – Amalia of Solms-Braunfels appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 4, 2019

The Year of Queen Victoria – The Lady Flora Hastings Scandal

The year 1839 caused scandal for Queen Victoria after the death of Lady Flora Hastings – a lady-in-waiting to Victoria’s mother, the Duchess of Kent.

The scandal, which gave the Queen a negative image, is well known, and when the first season of Victoria aired on ITV (UK) and PBS (US), it was a central plot point.

Lady Flora Hastings was the daughter of the 1st Marquess of Hastings, Francis Rawdon-Hastings and Flora Mure-Campbell. The aristocrat would enter the Royal Household as a lady-in-waiting for Victoria’s mother and would know about the Kensington System that kept then Princess Victoria isolated and under strict rules.

Well aware that Lady Flora knew about the system, Victoria viewed her with suspicion alongside Sir John Conroy, who she detested and referred to as the “devil incarnate.” Conroy served as a comptroller to Victoria and her mother.

Lady Flora was suspected of having an affair with Sir John Conroy and a swollen stomach, pain, nausea, and vomiting would be the perfect mixture for runaway rumours and theories. She met with Queen Victoria’s doctor, Sir James Clark, who wanted to examine her, but she refused. He prescribed her medicine of rhubarb and camphor. This led to him assuming she was pregnant. His suspicions were kept quiet, but the Baroness Lehzen (Queen Victoria’s governess) and the Marchioness of Tavistock (a close friend of the Queen) decided to spread rumours that she was pregnant after noticing her growing stomach.

The Queen would write in her journal that she suspected Lady Flora was pregnant by Sir John Conroy. She would write, in part, on 2 February 1839, that she suspected the Lady was “We have no doubt that she is – to use plain words – …with child!! Clark cannot deny the suspicion; the horrid cause of all this is the Monster and demon Incarnate, whose name I forbear to mention, but which is the 1st word of the 2nd line of this page.”

Lady Flora went on the defence and published an article in The Examiner denying the accusations and accusing a foreign lady (Baroness Lehzen) of spreading the false rumours.

Two weeks later, Sir James Clark told her she had to submit to an examination and that the Queen’s ladies said she should be privately married due to being pregnant out of wedlock. Only an exam would prove she was not carrying a child. Lady Flora’s mother would call this “this most revolting proposal.” Queen Victoria banned her from her court until she submitted to an examination. Lady Flora wrote, “Upon which he told me, that nothing but my submitting to a medical examination would ever satisfy them, and remove the stigma from my name. I found the subject had been brought before the Queen’s notice, and all this had been discussed, and arranged, and denounced to me, without one word having been said to my own mistress (the Duchess of Kent), one suspicion hinted, or her sanction obtained for their proposing such a thing to me… My beloved mistress, who never for one moment doubted me, told them she knew me, and my principles, and my family, too well to listen to such a charge. However, the edict was given.”

She eventually relented and had a physical examination, proving that she was not with child. According to Lady Flora, the examination was rough, prolonged and painful. It concluded that there were “no grounds for believing that pregnancy does exist, or ever has existed.” Victoria visited an agitated Lady Flora and promised to be everything behind them for the sake of her mother. Lady Flora accepted the Queen’s apology but said, “I must respectfully observe, madam, I am the first, and I trust I shall be the last, Hastings ever so treated by their Sovereign. I was treated as if guilty without a trial.”

Lady Flora wrote to her brother that “her honour had been most basely assailed” as a result of the examination by two doctors. Her brother, Lord Hastings teamed up with Sir Conroy, and together they attacked Queen Victoria and her doctor through the press for the malicious rumours that insulted Lady Flora. However, it did not work to discredit the Queen, but her approval took a dent.

Queen Victoria would visit her again on 27 June – just a few days before her death on 5 July 1839. She was mortified and wrote, “I found poor Ly. Flora stretched on a couch looking as thin as anybody can be who is still alive; literally a skeleton, but the body very much swollen like a person who is with child; a searching look in her eyes, a look rather like a person who is dying; her voice like usual, and a good deal of strength in her hands; she was friendly, said she was very comfortable & was very grateful for I had done for her & that she was glad to see me look well. I said to her; I hoped to see her again when she was better – upon which she grasped my hand as if to say ‘I shall not see you again.'” The autopsy report showed that Lady Flora had a grossly enlarged liver which was pressing on her stomach.

Queen Victoria’s approval would improve the following year after she married Prince Albert and fell pregnant. The occurrences with Lady Flora, though, would haunt the Queen for many years to come. She swore that she would never leap to such conclusions again and wrote, “I can’t think what possessed me.”

The post The Year of Queen Victoria – The Lady Flora Hastings Scandal appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 3, 2019

Queen Victoria – Daughter, Wife, Mother, Widow by Lucy Worsley Book Review

It is nearly impossible to miss the fact that we are celebrating 200 years since Queen Victoria’s birth and one of the new books this year is by Lucy Worsley, who is also the chief curator at Historic Royal Palaces.

Queen Victoria – Daughter, Wife, Mother, Widow also known as Queen Victoria: Twenty-Four Days That Changed Her Life takes you along her life through 24 days or “windows.” It begins with the double wedding of Queen Victoria’s parents and that of the Duke and Duchess of Clarence (later King William IV and Queen Adelaide) and ends with Queen Victoria’s death bed. I really enjoyed Lucy Worsley’s wit and style of writing. I was glad to see more unknown “windows” and it truly is a fresh look at Queen Victoria.

I did spot two errors in the family tree as the Princess Royal is listed as marrying Emperor Frederick II and Charlotte of Wales marrying a “Charles William of Brunswick.”

Overall, I would highly recommend Queen Victoria – Daughter, Wife, Mother, Widow by Lucy Worsley. It is available now in both the UK and the US.

The post Queen Victoria – Daughter, Wife, Mother, Widow by Lucy Worsley Book Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 2, 2019

Princesses of Orange – Queen Mary II of England

The future Queen Mary II of England and the future Prince of Orange was born on 30 April 1662 as the daughter of King James II of England and Anne Hyde. She grew up at Richmond Palace with her sister Anne. She spoke excellent French, learned to play several instruments. She also loved to read as well as dance. She was raised a Protestant, and she was confirmed in the Church of England in 1676, despite her father’s protests.

In 1677, Mary married her first cousin William, Prince of Orange. It was well-known that the future King James II, a Catholic himself, would have preferred a Catholic match. Mary reportedly wept all afternoon and the following day after being told that she was to marry William. She received a grand reception in the Netherlands. She would later describe her time in the Netherlands as the happiest time of her life. She learned to speak Dutch, and she was popular with the public. Her relationship with William was relatively good. He was disappointed when Mary and he had no surviving children. She had suffered a miscarriage in 1678 and likely suffered other miscarriages.

Their relationship changed for the worse when she publicly made a scene at the Loo Palace when he returned from a mistress at a late hour. In 1685, Mary’s father became King of England after the death of King Charles II. Mary herself realised by 1688 that her father’s politics might lead to a great crisis. Because of her earlier mistrust of her father, she easily believed the rumours that his son and her half-brother born in 1688 was a changeling. Later that year, William agreed to invade England to depose James, though he was initially reluctant. He was probably jealous of Mary’s position as the heiress and believed she would be more powerful than him. Mary told him she did not care for any political power. William then agreed to invade England, and he issued a declaration which referred to King James’s newborn son as the “pretended Prince of Wales.”

William left the Netherlands without Mary and landed in England on 5 November 1688. Mary’s father was defeated and attempted to flee on 11 December, but he was intercepted. He succeeded in escaping on 23 December, most likely because William had let him go. He managed to flee to France, and despite an attempt to return via Ireland, he never returned to England.

Mary returned to England in February 1689, and she would never go back to the Netherlands again. William and Mary were jointly crowned at Westminster Abbey in 1689. Mary did not take much part in the government of the country. She believed that women shouldn’t interfere in politics. However, while William was in battle or in the Netherlands between 1690 and 1694, Mary took on all of the duties. After a hesitant start, she became a leader, earning her the nickname ‘Good Queen Mary’.

Death came suddenly for Mary at the end of 1694. After falling ill with smallpox, she died on 28 December 1694. William was inconsolable and swore that no better person had ever lived. Mary was embalmed, but she was not buried until 5 March 1695. She had a grand funeral with a procession from Whitehall Palace to Westminster Abbey. Her father refused to let his exiled court to go into mourning for her.

William succeeded Mary as sole monarch as had been previously agreed and he never remarried. Mary’s sister Anne was pregnant several times, but a single son lived to the age of 11, before dying suddenly. The Act of Settlement eventually settled the succession of Sophia of Hanover. In the Netherlands, William was succeeded as Prince of Orange by John William Friso, of the Frisian branch of the family. He was William’s closest agnatic relative, as well as the son of William’s aunt, Albertine Agnes.

The post Princesses of Orange – Queen Mary II of England appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Diana, Princess of Wales was set to star in sequel to The Bodyguard with Kevin Costner

Kevin Costner has confirmed that the late Diana, Princess of Wales had been set to star alongside him in a sequel to The Bodyguard.

He told PeopleTV, “The studio liked the idea of doing a Bodyguard 2,” with Diana taking on a role “in the same kind of capacity as Whitney. Nobody really knew that for about a year.” The plot would have involved Costner’s character protecting Diana’s character from paparazzi and stalkers before the relationship turned romantic. The first script was delivered to him the day before Diana was killed in a crash on 31 August 1997.

Kevin Coster also recalled that he and Diana had discussed their roles and the possibility of intimate scenes. “I just remember her being incredibly sweet on the phone, and she asked the question, ‘Are we going to have, like a kissing scene?’” Costner recalled. “She said it in a very respectful … she was a little nervous because her life was very governed. And I said, ‘Yeah, there’s going to be a little bit of that, but we can make that OK too.’”

He said that talks for the film had been initiated by Sarah, Duchess of York. “Sarah was really important,” he said. “I always respect Sarah because she’s the one that set up the conversation between me and Diana. And she never said, ‘Well, what about me? I’m a princess too.’ She was just so supportive of the idea.”

The post Diana, Princess of Wales was set to star in sequel to The Bodyguard with Kevin Costner appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 1, 2019

From Queen Victoria to the German Crown Princess – 2 July 1862

From Queen Victoria to the German Crown Princess – Osborne, 2 July 1862

Poor Alice’s1 wedding2 (more like a funeral than a wedding) is over and she is a wife! I say God bless her – though a dagger is plunged in my bleeding, desolate heart when I hear from her this morning that she is ‘proud and happy’ to be Louis’ wife! I feel what I had, what I hoped to have for at least 20 years more and what I can only have in another world again. All that has been passed since December 143 seems gone – forgotten. What I shall not forget is Alice herself, and her wonderful bearing – such calmness, self-possession and dignity, and how really beautiful she looked, so tall and graceful, and her voice so sweet. The Archbishop of York read that fine service (purified from its worst coarsenesses) admirably, and himself had tears running down his cheeks – for he too lost his dear partner not long ago. I sat the whole time in an armchair, with our four boys near me; Bertie4 and Affie5 led me down stairs. The latter sobbed all through and afterwards – dreadfully.

Dear Uncle Ernest6 is very low, and sad and was much affected. It was a comfort to me that he, darling Papa’s only brother, led her and gave her away! I had rather he than any one else should do it. He was so affectionate at our marriage.

Prince and Princess Charles7 were much affected – but we none of us like her, and Alice not at all. She was very cold, very grand and not at all affectionate to Alice and most unamiable (and I must call it ‘de mauvaise foi’8 about Alice’s living a good deal here and about what is right and proper. But she has nothing to say and Louis is all right about it and most amiable. Alice is very determined and from the first has taken her position vis-à-vis of the ‘mother-in-law’. But I am sorry it should be so. I shall certainly see the Pagets as soon as possible and put General Grey and Sir C. Phipps (he knows more about Bertie even than the other, General Bruce being so very intimate with him) in communication with them.

I must end for today. Tomorrow I shall go over to see the ‘Honey-Couple’, who return here on Friday and on Tuesday evening, 8th, they embark.9

The post From Queen Victoria to the German Crown Princess – 2 July 1862 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 30, 2019

Sophia of Rheineck – The Countess who died in the Holy Land

Sophia of Rheineck was born circa 1120 as the only daughter of Otto I, Count of Salm and Gertrude of Northeim. She was married to Dirk VI, Count of Holland before 1135 and most likely in 1131. They went on to have at least 9 children together: Floris (future Count of Holland), Otto (future Count of Bentheim, through his mother), Dirk (died at the age of 12), Baudouin (bishop of Utrecht), Gertrude (died young), Petronilla (probably died young), Sophia (Abbes of Rijnsburg) and Hedwig (a nun at Rijnsburg). Dirk also had an illegitimate son named Robert who died sometime before 1190.

Sophia was known to be very pious. We know this because of her many gifts to the Abbeys of Egmond and Rijnsbrug and to the poor but she also went on several pilgrimages to the Holy Land. Her son Dirk was given the nickname “the Pilgrim” after being born during one of these pilgrimages. She also undertook a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela and was rescued from robbers with the help of Saint Adelbert. She went to the Holy Land three times during her lifetime. One of these pilgrimages was in 1173 after she had been widowed. She was accompanied by her son Otto.

Three years later, she went again and was probably joined by her sons Floris and Otto, at least part of the way. She would die in Jerusalem on 26 September 1176 and she was buried at the St. Mary’s hospital of the Teutonic Knights there.1

The post Sophia of Rheineck – The Countess who died in the Holy Land appeared first on History of Royal Women.