Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 222

May 23, 2019

Princess Victoria in her journal – 24 May 1833

Today is my birthday. I am today fourteen years old! How very old!! I awoke at half-past five and got up at half-past 7. I received from Mamma a lovely hyacinth brooch and china pen tray. From Uncle Leopold a very kind letter, also one from sister Feodora. I gave Mamma a little ring. From Lehzen I got a pretty little china figure and a lovely china basket. I gave her a golden chain…

At half past 7, we went to a Juvenile Ball that was given in honour of my birthday at St. James’s by the King and Queen. We went into the Closet. Soon after, the doors were opened, and the King leading me went into the ballroom… I danced (with several young gentlemen) We then went to supper. It was half-past 11; the King leading me again. I sat between the King and Queen. We left supper soon. My health was drunk… I danced in all 8 quadrilles. We came home at half-past 12. I was very much amused.1

The post Princess Victoria in her journal – 24 May 1833 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 22, 2019

The Year of Queen Victoria – The race to have Victoria born on British soil

The Duke of Kent was convinced that his future child would have a good chance of inheriting the throne, even though the Duchess of Clarence (Adelaide – wife of the future King William IV) was also pregnant. Besides, the Duchesses of Cumberland and Cambridge were also pregnant – though their children would be below any Kent baby in the succession. The Duke of Kent decided to bring his wife to England so that she could give birth there and so that dignitaries could confirm his child’s legitimacy.

He wrote to his brother the Prince Regent (the future King George IV) requesting a yacht, £1,200 for travel expenses, rooms in Kensington Palace and a house by the sea. The Regent refused as he was keen that the Duke of Kent should stay away. Both the Duchesses of Cambridge and Hanover were to have their children in Hanover. However, the Duke of Kent did not give in so easily, and his friends managed to raise money for his journey. Their efforts doubled when the Duchess of Clarence’s daughter died within a few hours of her birth in November 1818. On New Year’s Eve, the Duke of Kent wrote to his wife, “This evening will put an end, dear beloved Victoire, to the year 1818, which saw the birth of my happiness by giving you to me as my guardian angel… All my efforts are directed to one end, the preservation of your death health and the birth of a child who shall resemble you, and if Heaven will give me these two blessings I shall be consoled for all my misfortunes and disappointments, with which my life has been marked.”

By March, the Duke of Kent had finally raised about £15,000 through loans, bonds and gifts. He wrote again to the Regent asking for the Royal Yacht, and finally, the Regent consented – fearing criticism from the newspapers. The Duchess of Kent was nearly eight months pregnant when they set off for England on 28 March. She was driven to Calais by the Duke himself so they would not have to pay for a coachman. It was nearly 430 miles over appalling roads. Behind the Duchess of Kent’s coach came more coaches containing their belongings, Princess Feodora and her maids, several servants and even a surgeon and a female obstetrician – just in case the Duchess went into premature labour. They reached Calais on 18 April but had to wait a week before the weather was good enough to sail. Finally, on 24 April they embarked for England. After three hours on a rough sea, they finally arrived and set off for Kensington Palace. Their apartments had been empty since 1814 when Caroline of Brunswick – the Regent’s estranged wife – abandoned them. A thorough renovation was required, and the room where the Duchess would give birth received its final touches on 22 May. The following evening at 10.30, her labour began. After six hours of labour, at 4.15 in the morning, the Duchess of Kent gave birth to “a pretty little Princess, as plump as a partridge.”1

The post The Year of Queen Victoria – The race to have Victoria born on British soil appeared first on History of Royal Women.

From Queen Victoria to the Empress Frederick – 23 May 1891

From Queen Victoria to the Empress Frederick – Balmoral, 23 May 1891

This is the eve of my dear old birthday. I have much to be grateful for in the affection of my children, grandchildren, relations and friends and my people, and in good health; but I have also many anxieties, not the least of which is my sorrow for all your cruel trials and anxieties which ought not to be…

The visit to Derby was a great success. The decorations were beautiful and very tasteful and the enthusiasm great though it was dull. There was no real rain to speak of… Victoria B1 quite shares your feelings about Sophie’s2 treatment. She had not heard of the last dreadful outburst till I told her…3

The post From Queen Victoria to the Empress Frederick – 23 May 1891 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 21, 2019

Queen Elizabeth II – Mother and Queen (Part two)

On 9 July 1947, the engagement between Princess Elizabeth and Philip Mountbatten was announced. Shortly before the wedding, Elizabeth’s father bestowed a number of titles on his future son-in-law. He was to be the Duke of Edinburgh, Earl of Merioneth, Baron Greenwich and should be addressed as “His Royal Highness.” He was also invested with the Order of the Garter, a week after Elizabeth was also invested with it. On 20 November 1947, Elizabeth and Philip were married at Westminster Abbey. Elizabeth wore a dress by Norman Hartnell of pearl-and-crystal-encrusted ivory silk satin with a 15-foot train. After the hour-long service, Elizabeth emerged as Duchess of Edinburgh and the newlyweds were driven to Buckingham Palace in the Glass Coach. After a “wedding breakfast” the couple was driven to Waterloo Station to head to their honeymoon. From her honeymoon, Elizabeth wrote to her parents, “I only hope that I can bring up my children in the happy atmosphere of love and fairness which Margaret and I have grown up in.”

After their honeymoon, they took up residence in Clarence House, though they temporarily lived at Buckingham Palace while Clarence House was being renovated. Elizabeth soon found herself pregnant with her first child. On 14 November 1948 – not even a year after their wedding – Elizabeth gave birth to a son named Charles. She later wrote to her cousin Lady Mary Cambridge, “I still find it hard to believe that I really have a baby of my own!” She breastfed him until she fell ill with the measles and Charles was sent away so that he would not catch the illness. Their new home was finally ready for them in the summer of 1949. Philip was determined to have a career in the navy, and he had been taking courses at the Naval Staff College at Greenwich. He took up active service in October 1949 and became based in Malta and Elizabeth joined him there – leaving Charles behind. Margaret Rhodes – Elizabeth’s first cousin – later said, “I think her happiest time was when she was a sailor’s wife in Malta.” In 1950, she was pregnant once more, and on 9 May, she flew back to London to resume some of her royal duties. On 15 August 1950, Elizabeth gave birth to her second child – a daughter named Anne. She breastfed Anne for several months but left both Anne and Charles behind at the end of the year to rejoin her husband in Malta.

Embed from Getty Images

However, as her father’s health deteriorated, Elizabeth was called upon more than ever to stand in for her father when he was too sick to do so. It was soon clear that both Elizabeth and Philip were needed to represent the sovereign. King George VI was seriously ill with cancer. They would need to go on a long-planned state visit to Australia, New Zealand and Ceylon and decided to add a few days in Kenya. On 31 January 1952, the King and Queen went with Elizabeth to the airport to wave them off. In the early morning of 6 February, the King was found dead in his bed – the cause of death was a blood clot in his heart. It took a while to contact Elizabeth and Philip in Kenya, and it was Philip who broke the news to Elizabeth. She apparently did not cry but was “pale and worried.” They then took a long walk along the river. When asked what her name should be, she answered, “My own name, of course. What else?”

After a 19-hour flight back home, Elizabeth emerged as Queen dressed in a simple black coat and hat. At Clarence House, Elizabeth found her grandmother Queen Mary waiting to kiss her hand, though she added, “Lillbet, your skirts are much too short for mourning.” Her Accession Council took place the following day at St. James’s Palace and she declared, “By the sudden death of my dear father, I am called to assume the duties and responsibilities of sovereignty. My heart is too full for me to say more to you today than I shall always work, as my father did throughout his reign, to advance the happiness and prosperity of my peoples, spread as they are the world over… I pray that God will help me to discharge worthily this heavy task that has been lain upon me so early in my life.” On 15 February, her father was laid to rest.

By April, the family had moved into Buckingham Palace, and she adopted an office schedule, which she would maintain throughout her reign. Almost every single day, she attended to the red leather dispatch boxes filled with official government papers. Elizabeth’s mother had been only 51 when she had been widowed, and she was urged to continue her public service as she was a much-loved figure. She and Elizabeth spoke nearly every day on the telephone.

Embed from Getty Images

Two months before Elizabeth’s coronation, Queen Mary died in her sleep, and upon her request, the coronation was not postponed. The coronation was the first of a British monarch to be televised, though the most sacred parts were left out. Canon John Andrew later said, “The real significance of the coronation for her was the anointing, not the crowning. She was consecrated, and that makes her Queen. It is the most solemn thing that has ever happened in her life. She cannot abdicate. She is there until death.” Elizabeth had made Charles, Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester on 26 July 1958 but he was not invested until 1969.1

Part three coming soon.

The post Queen Elizabeth II – Mother and Queen (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 20, 2019

Stéphanie of Belgium – The would-be Empress of Austria (Part one)

At the time of Stéphanie’s marriage to Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria, the Austrian court was one of the most brilliant in Europe. The following tragedies plunged into sadness from which it never recovered.

Princess Stéphanie of Belgium was born on 21 May 1864 as the daughter of King Leopold II of Belgium and Archduchess Marie Henriette of Austria at the Royal Palace of Laeken. She was their third child, after an elder sister named Louise and an elder brother named Leopold – who tragically died in childhood. Another daughter named Clémentine would be born in 1872. Her father spent little time with his family, and Stéphanie later wrote in her memoirs, “One can hardly be surprised that the children of such a marriage were foredoomed to unhappiness.” Nevertheless, Stéphanie was devoted to her mother despite also being afraid of her. Stéphanie’s formal education began at the age of six and her sister’s governess Mademoiselle Legrand also took her under her wings. Her days were filled with iron discipline; rising at five, being silent while dressing and doing the toilet, making her own bed, saying her prayers, at her school work by half-past eight, which was done for the entire day except for three hours devoted to walking, games and gardening. The windows were kept open in winter and summer, and Stéphanie wrote, “In winter the study was like an ice-house, and my teeth chattered with the cold.”

Stéphanie enjoyed painting and reading, but neither hobby was encouraged as her mother was afraid it would distract her from more important things. Stéphanie often underwent punishments, such as kneeling on parched peas. She most dreaded being confined between double days – where she sometimes spent an entire day. Stéphanie was especially close to Mademoiselle Antoinette Schariry – nicknamed Toni – who had entered the royal household shortly after Stéphanie’s birth. She was also fond of her aunt and uncle, the Count and Countess of Flanders, the parents of the future King Albert I of Belgium. In 1871, Stéphanie fell with typhoid fever, and for weeks she suffered horribly. Miraculously, she made a full recovery.

Three years later, her sister Louise announced her betrothal to Prince Philipp of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and cried upon being told that Louise was going to leave. Louise’s wedding took place on 18 February 1875. Stéphanie later wrote, “I can still picture her kneeling at the steps of the altar, then getting up and curtseying to her parents, the King and Queen, before she uttered the decisive word, the word which fettered her forever to the man she had not chosen for herself, but who had been chosen for her by others.” For Stéphanie, life continued at its monotonous pace.

In 1878, her aunt Archduchess Elisabeth Franziska of Austria came to visit, perhaps to discuss the idea of Stéphanie marrying the Crown Prince of Austria. The following winter, Stéphanie would also meet her future mother-in-law, Empress Elizabeth, when she came to visit on her way to England. Stéphanie was allowed to kiss her hand and received an embrace. Some weeks later, Stéphanie was finally allowed to wear a long dress with a train to meet Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha who had also heard of the marriage rumours. On 4 March 1880, Crown Prince Rudolf visited the court at Brussels and the following day her father told her, “The Crown Prince of Austria-Hungary is here to ask your hand in marriage. Your mother and I are very much in favour of this marriage. It is our desire that you should be the future Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary. You can withdraw now, think over this plan, and give us your answer tomorrow.” Stéphanie talked to Toni and her mother, who believed it would be her greatest happiness if Stéphanie became Austrian by marriage. Stéphanie – still only 15 years old – did not sleep at all that night. In the end, Stéphanie abided by her parents’ wishes and consented to the match. She later wrote, “I never guessed how heavy I should find the chains he (her father) was forging for me. I had no inkling that I was already being betrayed. Not until months later did I learn that my future bridegroom had not come to Brussels alone, but accompanied by his mistress, a certain Frau F.”

Stéphanie and Rudolf

Stéphanie and RudolfCrown Prince Rudolf presented her with an engagement ring, a large sapphire surrounded by diamonds. During the following dinner, Rudolf spoke of his plans for the future and Stéphanie wanted nothing more than to acquaint herself with his thoughts to become a suitable companion to him. The formal betrothal took place on 7 March in the palace chapel. The wedding was set for the end of the year. Stéphanie now underwent a crash course in preparing her for court life. She was expected to attend every official dinner and was given lessons in dancing and deportment. However, the wedding had to be postponed because Stéphanie had not had her first menstruation yet. Nevertheless, the preparations went on, and the new wedding date was set for 10 May. She later wrote, “I had pondered matters long and deeply, but at sixteen I was still no more than a child, incapable of grasping the situation.”

On 2 May 1881, Stéphanie left Belgium for her new life in Austria. When Stéphanie entered the specially prepared train, she lost control and began to cry. Her mother held her and chided her for breaking down. She was so exhausted that she fell asleep before they had left Belgium and did not wake until Augsburg in Bavaria. The followed day, she was met by her future husband at Salzburg. He later took a train to Vienna while Stéphanie followed him on 6 May. At Schönbrunn, Stéphanie met her future family-in-law. On the morning of her wedding, her mother took her to take mass in the court chapel. Afterwards, her mother helped Toni to dress Stéphanie for her wedding. Her wedding dress was made of heavy silver brocade with garlands and silver roses embroidered on its long train. Her veil was of Brussels lace, and it was fastened by a diamond brooch. She wore a diadem given to her by the Emperor, and she wore the Order of the Star and Cross. She later wrote, “As for my feelings at this moment, they were much more those of a martyr than of a bride.”1

Part two coming soon.

The post Stéphanie of Belgium – The would-be Empress of Austria (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 19, 2019

Begum Hazrat Mahal – The rebel Princess

Born as Muhammadi Khanum at Faizabad, Awadh, India, into an extremely poor family, Muhammadi Khanum was sold into the royal harem as a khawasin (attendant). She was trained in the harem in manners, etiquette and Royal ways. She grew up to be a beautiful, intelligent girl and rose from being a khawasin to being a part of the royal Pari Khana (house of fairies).

In those days beauty could help you up to a certain point, but to stand out among the crowd of girls one had to be clever, creative and wise, especially in a harem full of women. The house of fairies was an institution set up by Nawab Wajid Ali Shah (1822 -1887) to train young, beautiful girl for theatre and dances. The last Nawab of Awadh was a patron of the arts, drama, dance, music and poetry. He was a gifted composer who had received vocal training under great ustads (teachers ). He is widely credited with the revival of Kathak, a classical Indian dance form. In the Pari Mahal, Muhammadi Khanum’s talent was noticed, and she was given a new name Mehak Pari (fragrance fairy). This was the time when courtesans were not looked down upon and were refined and respected. Soon, Mehak Pari had a special place in Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s court, and she became Nawab’s concubine. The Nawab had many such wives, and they were given the title of ‘Begum’ if they gave him a male heir. Then, they would become his official wife and could get accommodation in the palace. Mehak Pari did produce a male heir and was given the title of Begum and the new name ‘Hazrat Mahal’.

She was one of the favourite young queens and envied by other older queens. In 1856, Nawab Wajid Ali Shah had to leave Awadh, after his Kingdom was annexed by the East India company on very flimsy grounds. He was sent to Calcutta. He could not take all his wives and servants so, Begum Hazrat Mahal, her son, the young heir to the throne, Birgis Qadr, and the other wives were left in Awadh.In1857, rumours of anger among sepoys in the British army started doing the rounds. The cartridges of a new rifle were greased with cow and pig fat – cow being a sacred animal for Hindus and pig was forbidden for Muslims. Soon this rumour fanned deep anger and resentment for the East India company and revolt broke out. This was India’s first war of independence.

The people of Awadh were already angry that their ruler had been deposed. They stood with the rebellious soldiers of various cantonments. They needed a leader, and Begum Hazrat Mahal played the part. This is where the true character of Begum Hazrat Mahal came out. She led from the front; organising, planning strategy and administrating. This was a big surprise to the East India company. She united Hindus and Muslims against the British. She worked across the classes, castes, religions and genders to bring everybody together against one common enemy. She was in charge of her army. Her army commander was a Hindu king. The rebels under her leadership took the city of Lucknow, forcing Sir Henry Lawrence, commissioner of Awadh, along with his troops and all Europeans to seek refuge in the residency.

Begum Hazrat Mahal and her forces kept on attacking the residency, and Sir Henry Lawrence had no choice but to stay put and wait for more troops. The siege of the residency continued for months, and the troops that came for help could only save the people trapped inside the residency as Begum Hazrat Mahal had made sure that they could not fight the resistance and her army. The siege of the residency lasted for several months, Begum Hazrat Mahal called upon the people to stand by her and her army and to donate funds and help her to throw the British out of India. She refused all offers of a peace treaty and a pension. As the siege of the residency was a long one, soldiers felt demotivated, and many deflected and deserted. The king of Nepal also agreed to send his army to help the British. Begum Hazrat Mahal left with a relatively small army and had to flee from Lucknow. She finally fled towards the Nepalese border joined by another rebel prince Nana Sahib Peshwa, thinking of organising her troops again and attacking the British. Slowly the war of independence was crushed. Many of its leaders were either caught and hanged or dead.

After the revolt of 1857 powers went from the East India company to the British monarchy. Queen Victoria, proclaimed herself as ‘Empress of India’. In 1858, she passed a proclamation, promising to give more freedom to native Indians for their religion and better governance. Along with this came a pardon for all the rebels.

Begum Hazrat Mahal refused to surrender, calling the proclamation a sham. She said,”To eat pigs and drink wine, to bite greased cartridges and to mix pig’s fat with sweetmeats, to destroy Hindu and Musalman temples on pretence of making roads, to build churches, to send clergymen into the streets to preach the Christian religion, to institute English schools and pay people a monthly stipend for learning the English sciences, while places of worship of Hindus and Musalman are to this day entirely neglected; with all this how can people believe that religion will not be interfered with?”

She refused to surrender and escaped to Nepal, and she took her jewels and treasures along with her to live a dignified life in a new land. ‘The Times’ in London stated, “The Begum of Awadh shows greater strategic sense and courage than all her generals put together.” High praise indeed.

Begum Hazrat Mahal died in exile in 1879. She was buried in a cemetery close to the mosque she helped built and had named it ‘Hindustani Masjid’. While in exile, she continued to closely follow developments back in India and repeatedly refused to return to India. With each offer of a pardon and a pension, she sent a fitting reply. To one such offer she had replied, “Do not tell me about such things, I am fully aware what you have done with the children of Tipu Sultan and with Bahadur Shah Zafar until your type of people will prevail, Lakshmi Bai and Hazrat Mahal will take birth in this country.”

The post Begum Hazrat Mahal – The rebel Princess appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 18, 2019

Elizabeth of Poland – The popular Duchess of Pomerania

Elizabeth of Poland, Duchess of Pomerania, does not have the fame and accomplishments that her namesake aunt has. However, she is fondly remembered in the Pomeranian city of Szczecinek, which shows that she must have been a popular duchess in her lifetime. Everything known about her suggests that she was an ideal duchess consort.

Early years and marriage arrangements

Elizabeth was the first of two daughters born to Casimir III, King of Poland and his first wife, Aldona-Anna of Lithuania. She had one younger full sister named Kunigunde. The girls seem to have been born in the early years of their parents’ marriage before Casimir became king in 1333. Elizabeth’s birth occurred between 1326 and 1331, probably closer to the first date.

As the oldest daughter of a king, marriage arrangements were underway for Elizabeth from an early age. Casimir wanted to form a marriage alliance with the Wittelsbach dynasty that ruled Bavaria. At the time, the Wittelsbachs were one of Europe’s most powerful dynasties. The head of the family, Louis, was the Holy Roman Emperor since 1328. In 1335, a possible marriage between Elizabeth and Louis the Roman, the eldest son of the Emperor from his second marriage to Margaret of Hainault, was planned. However, a formal betrothal never happened, and by the end of the year, Casimir was looking at another branch of the Wittelsbach dynasty instead. This time, an agreement for the engagement of Elizabeth to John, the son of Henry, Duke of Lower Bavaria, was signed. This arrangement was broken off by 1338.

In September 1338, plans for Elizabeth to marry Louis the Roman returned. On 26 November 1338, the two were betrothed. However, in 1341, Casimir wanted to make an alliance with the dukes of Pomerania. He agreed to marry one of his daughters to Bogislaw V, Duke of Pomerania-Wolgast. Elizabeth, as the older daughter was eventually chosen as Bogislaw’s bride. Just like her parent’s marriage, Elizabeth’s marriage was arranged as an alliance against the Teutonic Knights. Her sister, Kunigunde, instead would be married to Louis the Roman in 1345.

Duchess Elizabeth

Elizabeth and Bogislaw were married on 24 or 25 February 1343. At the time, the Duchy of Pomerania was divided between two branches of the Griffins dynasty. Bogislaw ruled the eastern side (known as Pomerania-Wolgast) with his younger brothers Barnim IV and Wartislaw V. The western side, know as Pomerania-Stettin, was ruled by their cousin, Barnim III. The Duchy of Pomerania was located on the Baltic coast in present-day Poland and East Germany.

Elizabeth and Bogislaw had three children; a daughter Elizabeth, born between 1345 and 1347, a son Casimir, born around 1351, and an unnamed daughter who probably died in infancy. Not much is known about Elizabeth’s activities, and she was not politically active. She, however, introduced elements of Polish culture to Pomerania, which was becoming more and more German and Danish. Elizabeth’s seal, which shows her royal origin has been preserved.

In 1356, Bogislaw and his brothers founded an Augustine monastery near Szczecinek. Elizabeth probably supported the building of the monastery and was connected to it for the rest of her life. In 1357, Casimir began efforts to Christianize Lithuania, the homeland of her mother. Elizabeth probably supported this. Lithuania was still largely pagan at the time. However, it was not successfully Christianized until about thirty years later.

Since Casimir did not have any sons of his own, he looked at Elizabeth’s son, also named Casimir, as his possible successor. In 1360, to secure peace with Lithuania, King Casimir had his grandson married to Kenna, the daughter of the Lithuanian duke, Algirdas, who also happened to be Elizabeth’s maternal uncle. Just like Elizabeth’s mother, Aldona-Anna, Kenna was raised as a pagan and needed to be baptised. She was baptised with a new name, Joanna, soon before the marriage.

In 1356, a plague swept through Pomerania. Elizabeth and her sister-in-law, Sophia of Mecklenburg (wife of Barnim IV) took refuge at the Augustine monastery near Szczecinek that their husbands had founded. Elizabeth died there in 1361, but it’s unclear if it was from the plague or not. She was no more than thirty-five. The year of her death is known from some chronicles, but the exact date has not been recorded. Elizabeth was buried in this monastery, according to her own wish. Bogislaw married secondly to Adelaide of Brunswick-Grubenhagen. He died in 1374.

Soon after Elizabeth’s death, her father took her two children to his court. By this time, Casimir did not have any surviving legitimate children left, so his grandchildren were very important in his plans. In 1363, Elizabeth’s namesake daughter was married to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles IV. Elizabeth’s son was seen as his grandfather’s heir to the Polish throne, but on Casimir’s death in 1370, his nephew Louis I, King of Hungary took the throne instead. It is interesting to think that if Elizabeth outlived her father, her son may have had a better chance of becoming king.

Commemoration

Although she was not politically active, Elizabeth seems to be one of the most memorable Pomeranian duchesses. Largely forgotten today, she is still well-remembered in Pomerania, especially Szczecinek. She is considered an important figure in Polish-Pomeranian relations. In Szczecinek, she is a patron of a school that is named after her. Every year, the school hosts a festival called Elzbietanki. There is also a street named after her in the city. There are various legends about her around Szczecinek, and in 1965, a local poet wrote a poem about her. Most recently, Elizabeth has been a character in the Polish television series Korona Krolow (Crown of Kings), which dramatizes the reign of her father.1

The post Elizabeth of Poland – The popular Duchess of Pomerania appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 17, 2019

Book News June 2019

An Audience with Queen Victoria: The Royal Opinion on 30 Famous Victorians

Paperback – 1 March 2019 (UK) & 1 June 2019 (US)

During her 63-year reign Queen Victoria met everyone from Charlotte Brontë to Buffalo Bill; she had opinions on all those who graced her parlor—and some who didn’t. This book examines the meetings and letters exchanged between the queen and a veritable who’s who of her time. It draws on often brutal character assessments in her journals and letters—Henry “Dr. Livingstone I presume” Stanley was “a determined ugly little Man.” Exploring those she met officially and personally, and her thoughts on figures of the time such as Jack the Ripper, this book unlocks a fascinating aspect of Victoria’s outlook through brand-new archival research, newspapers and interviews with descendants.

Ira: The Life and Times of a Princess

Hardcover – 17 June 2019 (UK) & 28 May 2019 (US) A breathtakingly beautiful photo-narrative biography of the incredible life of Princess Ira von Fürstenberg – half Austro-Hungarian Princess, half Agnelli: model, actress, princess, socialite, heiress, mother, and jewellery designer. Bursting onto front-page news in 1955 at the age of 15 in a jewel-laden gondola-wedding in the last great assembly of European nobility, Princess Ira von Fürstenberg swung into the spotlight and has never left. Subject for master photographers Cecil Beaton and Helmut Newton, among others, actress alongside Klaus Kinski and Peter Lawford, and model for Vogue’s Diana Vreeland, Princess Ira has been an actress, model, muse, mother, socialite, jewellery designer, and creator of objets d’art. On and off screen, in and out of the flashbulb, Ira’s life – or, more accurately, lives – reads like a history of the jet set. More than just a chronicle of a gorgeously fascinating life, this lavish photographic biography is a truly sumptuous snapshot of the glamour and charm of a lost era, a prism through which to see the world of European royalty, Italian cinema in its heyday, couture at most haute, and parties at their wildest.

Maria Romanov: Third Daughter of the Last Tsar, Diaries and Letters, 1908–1918

Hardcover – 30 May 2019 (US) & 30 June 2019 (UK)

In Maria Romanov: Third Daughter of the Last Tsar, Diaries and Letters, 1908–1918, by translator and researcher Helen Azar with George Hawkins, Mashka’s voice is heard again through her intimate writings, presented for the first time in English. The Grand Duchess was much more than a pretty princess wearing white dresses in hundreds of faded sepia photographs; Maria’s surviving diaries and letters offer a fascinating insight into the private life of a loving family—from festivals and faith, to Rasputin and the coming Revolution; it is clear why this middle child ultimately became a pillar of strength and hope for them all. Maria’s gentle character belied her incredible courage, which emerged in the darkest hours of her brief life. “The incarnation of modesty elevated by suffering,” as Maria was described during the last weeks of her life, she was able to maintain her kindness and optimism, even in the midst of violence and degradation.

Queens of Sicily 1061-1266: The queens consort, regent and regnant of the Norman-Swabian era of the Kingdom of Sicily (Sicilian Medieval Studies)

Paperback – 6 June 2019 (US) & unknown (UK)

Eighteen women. Eighteen stories. Each one unique. Some never told before. They are the semi-forgotten women of European medieval history. This is the first compendium of detailed scholarly biographies of the countesses and queens of the Kingdom of Sicily during the Hauteville and Hohenstaufen reigns, based on original research in medieval charters, chronicles and letters, augmented by extensive on-site research at castles, cathedrals and towns across Europe. The multicultural Kingdom of Sicily described here encompassed the island and nearly half of the Italian peninsula. It was one of the most powerful kingdoms of Europe and the Mediterranean. Its queens came from Italy, England, France, Spain, Portugal, Germany, Greece and elsewhere, constituting a cosmopolitan sisterhood.

The Quest for Queen Mary

Paperback – 13 June 2019 (UK) & 17 September 2019 (US)

When James Pope-Hennessy began his work on Queen Mary’s official biography, it opened the door to meetings with royalty, court members and retainers around Europe. The series of candid observations, secrets and indiscretions contained in his notes were to be kept private for 50 years. Now published in full for the first time and edited by the highly admired royal biographer Hugo Vickers, this is a riveting, often hilarious portrait of the eccentric aristocracy of a bygone age. Giving much greater insight into Queen Mary than the official version, and including sharply observed encounters with, among others, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, the Duke of Gloucester, and a young Queen Elizabeth, The Quest for Queen Mary is set to be a classic of royal publishing.

Queen of the World

Paperback – 13 June 2019 (UK)

On today’s world stage, one leader stands apart. Queen Elizabeth II has seen more of the planet and its people than any other head of state, and has engaged with them like no other monarch in British history. Since her coronation, she has visited over 130 countries across the ever-changing globe, acting as diplomat, stateswoman, pioneer and peace-broker. She has transformed her father’s old empire into the Commonwealth, her ‘family of nations’, and has come to know its leaders better than anyone. In 2018, they would gather in her own home to endorse her eldest son, the Prince of Wales, as her successor. With extensive access to the Queen’s family and staff, Hardman tells a true story full of drama, intrigue, exotic and even dangerous situations, heroes, rogues, pomp and glamour – and, at the centre of it all, the woman who has genuinely won the hearts of the world.

Elizabeth of Bohemia: A Novel about Elizabeth Stuart, the Winter Queen

Paperback – 4 June 2019 (US) & 6 June 2019 (UK)

October 1612. King James I is looking to expand England’s influence in Europe, especially among the Protestants. He invites Prince Frederic of the Palatinate to London and offers him his 16-year-old daughter Elizabeth’s hand in marriage. The fierce and intelligent Elizabeth moves to Heidelberg Castle, Frederic’s ancestral home, where she is favored with whatever she desires, and the couple begins their family. Amid much turmoil, the Hapsburg emperor is weakened, and with help from Bohemian rebels, Frederic takes over royal duties in Prague. Thus, Elizabeth becomes the Queen of Bohemia. But their reign is brief. Within the year, Catholic Europe unites to take back the Hapsburg throne. Defeated at the Battle of White Mountain, Frederic, Elizabeth, and their children are forced into exile for a much-reduced life in The Hague. Despite tumultuous seasons of separation and heartache, the Winter Queen makes every effort to keep her family intact. Written with cinematic flair, this historical novel brings in key figures such as Shakespeare and Descartes as it recreates the drama and intrigue of 17th-century England and the Continent. Elizabeth’s children included Rupert of the Rhine and Sophia of Hanover, from whom the Hanoverian line descended to the present Queen Elizabeth II.

Royal Women and Dynastic Loyalty (Queenship and Power)

Paperback – 18 June 2019 (UK & US)

Royal women did much more to wield power besides marrying the king and producing the heir. Subverting the dichotomies of public/private and formal/informal that gender public authority as male and informal authority as female, this book examines royal women as agents of influence. With an expansive chronological and geographic scope―from ancient to early modern and covering Egypt, Great Britain, the Ottoman Empire, and Asia Minor―these essays trace patterns of influence often disguised by narrower studies of government studies and officials. Contributors highlight the theme of dynastic loyalty by focusing on the roles and actions of individual royal women, examining patterns within dynasties, and considering what factors generated loyalty and disloyalty to a dynasty or individual ruler. Contributors show that whether serving as the font of dynastic authority or playing informal roles of child-bearer, patron, or religious promoter, royal women have been central to the issue of dynastic loyalty throughout the ancient, medieval, and modern eras.

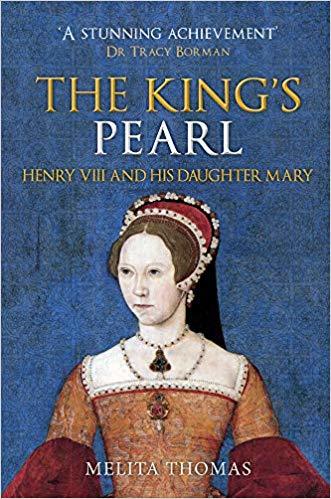

The King’s Pearl: Henry VIII and His Daughter Mary

Paperback – 15 June 2019 (UK) & 1 November 2019 (US)

Mary Tudor has always been known as ‘Bloody Mary’, the name given to her by later Protestant chroniclers who vilified her for attempting to re-impose Roman Catholicism in England. Although a more nuanced picture of the first queen regnant has since emerged, she is still stereotyped, depicted as a tragic and lonely figure, personally and politically isolated after the annulment of her parents’ marriage and rescued from obscurity only through the good offices of Katherine Parr.

Although Henry doted on Mary as a child and called her his ‘pearl of the world’, her determination to side with her mother over the annulment both hurt him as a father and damaged perceptions of him as a monarch commanding unhesitating obedience. However, once Mary had finally been pressured into compliance, Henry reverted to being a loving father and Mary played an important role in court life.

As Melita Thomas points out, Mary was a gambler – and not just with cards. Later, she would risk all, including her life, to gain the throne. As a young girl of just seventeen she made the first throw of the dice, defiantly maintaining her claim to be Henry’s legitimate daughter against the determined attempts of Anne Boleyn and the king to break her spirit.

The post Book News June 2019 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Princess Victoria in her Journal – 18 May 1836

Princess Victoria in her Journal – 18 May 1836

At a quarter to 2 we went down in the Hall, to receive my Uncle Ernest, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha and my Cousins, Ernest and Alberts, his sons. My Uncle was here, now 5 years ago, and is looking extremely well. Ernest is as tall as Ferdinand and Augustus1; he has dark hair, and fine dark eyes and eyebrows, but the nose and mouth are not good; he has a most kind, honest and intelligent expression in his countenance, and has a very good figure. Albert, who is just as Ernest but stouter, is extremely handsome; his hair is about the same colour as mine; his eyes are large and blue, and he has a beautiful nose and a very sweet mouth with fine teeth; but the charm of his countenance is his expression, which is most delightful; c’est à la fois2 full of goodness and sweetness, and very clever and intelligent.

Both my Cousins are so kind and good; they are much more formés3 and men of the world than Augustus; they speak English very well, and I speak it with them. Ernest will be 18 years old on the 21st of June and Albert 17 on the 26th of August. Dear Uncle Ernest made me the present of a most delightful Lory, which is so tame that it remains on your hand, and you may put your finger in its beak, or do anything with it, without its ever attempting to bite.4

The post Princess Victoria in her Journal – 18 May 1836 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 16, 2019

Lutgardis of Luxembourg – An unknown Countess

Lutgardis of Luxembourg was born circa 955 as the daughter of Siegfried of Luxembourg and Hedwig of Nordgau. Unfortunately, we do not know much about her. We know that her parents were very pious and they made sure that she was well-educated. Her sister Cunigunda, who married Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor, learned to embroider but also to read and write. She also spoke Latin. Lutgardis probably had a similar education.

In 980, Lutgardis married the future Arnulf, Count of Holland. They went on to have at least two sons, the future Dirk III, Count of Holland and Sicco (Siegfried) who married a woman of unknown origin named Thetburg. They may have had one or more daughters but they are not recorded. Lutgardis does not appear in any of her husband’s charters.

Lutgardis was with her sons in Ghent when she received the news of her husband’s death in battle in September 993. She then offered their possessions in Rugge to the St Peter’s Abbey in Ghent for her husband’s soul. With the help of her brother-in-law Henry II, the Holy Roman Emperor, she managed to maintain the county of Holland. She last appeared in 1005 when she asked for his help with the Frisians. She died on 13 May of an unknown but certainly after 1005. She was buried in Egmond Abbey next to her husband.

There is no surviving image of Lutgardis.1

The post Lutgardis of Luxembourg – An unknown Countess appeared first on History of Royal Women.