Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 4

February 3, 2025

Helena P. Schrader on Biographical Fiction -- Or the Fine Art of Resurrecting the Dead

Helena P. Schrader is the author of six non-fiction history books and twenty historical novels, twelve of which have won one or more literary award. Her novels on the Battle of Britain and the Berlin Airlift have been a #1 best-sellers on amazon. She holds a PhD in History earned with a dissertation on a leading figure in the German Resistance to Hitler and served more than a decade in the U.S. Diplomatic Corps. Born and raised in the United States, she has since lived in Asia, South America, Africa and more than forty years in Europe, where she is now retired.

My first published work was a non-fiction biography of General Friedrich Olbricht so it is probably not surprising that I soon turned to biographical fiction. Biographical fiction is the art of bringing historical figures back to life. It turns a name in the history books into a person so vivid, complex, and yet comprehensible that history itself becomes more understandable. Good biographical fiction provides insight into the psychology of real historical characters and so helps explain the historical events these men and women helped shape by explaining the motives and character traits that drove them to play their role in history.*

While I love writing biographical fiction, it has a number of unique challenges. As with writing history of any kind, there are always gaps in the historical record and events so controversial or complex that they produce multiple, conflicting accounts. When writing biography, however, there is the added challenge of trying to understand motives for recorded actions and the emotions of the individuals involved ― unless, of course, the subject kept diaries or wrote letters and memoirs describing emotions. In that case, however, the biographer is confronted with the equally challenging issue of how honest or self-serving such documents are!

Biographers like historians, whether working in fiction or non-fiction, must fill in gaps, select between competing accounts of events, and speculate about motives and emotions. Non-fictional biographers do this openly by discussing the different possible interpretations and explaining the reasoning behind their analysis of the character’s actions and motives. Novelists do this by turning their analysis of events into a novel and their interpretation of the personalities into characters.

For the biographical novelist, the historical record is therefore the skeleton ― or plot ― of the book. History, not the novelist, defines the beginning and the end of the principal character, and indeed all the essential historical events in between. But most readers do not want to read about skeletons, certainly not inert ones. They want characters with flesh and blood – with faces, emotions, dreams, and fears. The goal of a biographical novelist is to add contours, colours, animation and above all personality to that historical skeleton.

The novelist’s toolbox for fleshing out a historical skeleton includes research into the “skeleton’s” family background, social status, and profession (and that of the “skeleton’s” ancestors, spouse and partners as well). It includes investigating the customs and culture of the society in which the “skeleton” lived, the legal system to which he or she was subject, the technology and fashions of the age and more. In addition, the biographer (whether for fiction or non-fiction) must also investigate the biographies of known figures who influenced the subject: e.g. their parents, siblings, spouses, colleagues, superiors and subordinates, partners, opponents and rivals.

Only after the biographer has developed an understanding of the environment in which the subject lived and the relationships the historical figure had with his contemporaries is it possible to start constructing a plausible character. Based on this research, the novelist evolves an understanding of why the subject acted in one way or another. The novelist is able to hypothesize the emotions the subject likely felt in certain situations, and to understand the fears, inhibitions, ambitions, and obsessions that might have driven, inspired, warped, and hindered the protagonist. An excellent example of this is Sharon Kay Penman’s biographical novel of Richard III, The Sunne in Splendour. She effectively explains King Richard III by showing how his childhood relationships with his brothers and his Neville cousins made him the man he became.

So far, so good, but a good novelist, in contrast to a non-fiction biographer, also wants to address readers at a literary level. A good novel is not just accurate history about engaging characters, it should also have some compelling themes that will keep the reader thinking about the book long after the reading is over. In biographical fiction, however, the historical skeleton limits a novelist’s freedom of action. It is not possible to give a biographical novel about Anne Boleyn a happy ending!

So this is where it gets tricky ― and bit controversial: a biographical novelist striving to produce a work of art may feel the need to deviate – carefully, selectively, and strategically – from the historical record. This is not about giving a character two heads, or only one hand: it is about changing very subtly some of the “flesh and blood.”

Let me give an example from the world of painting. The surviving contemporary paintings of Isabella I of Castile painted by unknown artists who may have met her are not terribly flattering or inspiring.

However, there are many portraits of Isabella by subsequent artists who had certainly never laid eyes on her yet who produced works that are far more evocative and appealing. These later works may not as accurately depict Isabella’s physical features, yet they may capture her spirit in that they make the viewer see aspects of Isabella’s known personality – her piety combined with her iron will, and so on.

This explains how different works of biographical fiction about the same subject can be very different ― yet equally good. Is Schiller’s or Shaw’s Joan of Arc better? I cannot say offhand which one historians would choose as more accurate, but I do know that both – regardless of which is more accurate – are great works of biographical fiction.

This explains how different works of biographical fiction about the same subject can be very different ― yet equally good. Is Schiller’s or Shaw’s Joan of Arc better? I cannot say offhand which one historians would choose as more accurate, but I do know that both – regardless of which is more accurate – are great works of biographical fiction.Creating a work of art requires clarity of purpose, consistency of style, and a proper use of light and dark. It requires not only extrapolating and interpreting, but some outright falsification. In a novel, it almost always requires the creation some fictional characters – servants or friends, lovers or rivals – that serve as foils for highlighting character traits, explain later (known) behavior, or provide contrast in order to give the central character deeper contours.

However, from my experience as a writer of non-fictional biography (Codename Valkyrie: General Olbricht and the Plot Against Hitler) and biographical fiction (the Leonidas of Sparta trilogy and the Balian d’Ibelin trilogy), the greatest challenge for the biographical novelist is paring away or condensing some of the known facts or strategically making changes to the historical record in order to produce a clearer and more compelling central character or more comprehensible story.

When resurrecting the dead, historical novelists seek to raise the spirit, not the body. The spirit, not each pound of flesh or each wrinkle on the face, is what we wish our readers and future generations to understand and honor. And spirits are always ethereal, elusive – and not quite real.

* This essay is based on an article that first appeared in the History Press. Copyright Helena P. SchraderJanuary 27, 2025

Historical Figures in Historical Fiction -- A Guest Entry from Mercedes Rochelle

Mercedes Rochelle is an ardent lover ofmedieval history and has channeled this interest into fiction writing. Shebelieves that good Historical Fiction is an excellent way to introduce thesubject to curious readers. Born in St. Louis, MO, she received a BA inLiterature at the Univ. of Missouri St.Louis in 1979, then moved to New York in1982 while in her mid-20s to "see the world". The search hasn'tended! Today she lives in Sergeantsville, NJ with her husband in a log home theybuilt themselves.

Many thanks, Helena, for giving me theopportunity to chat on your blog page. Biographical fiction is all I write,ever since my first book when I discovered the joy of research. In the middleof that first novel, I evolved from a sort of myth/legendary theme (the Witchesof Macbeth) to actual historical figures, which I found much more interesting.And I’ve never looked back.

Every book presents a Point of Viewchallenge to me. Some of my own characters seem very distant to me, while withothers, I climb into their heads. And I can’t figure out why.

My second novel, Godwine Kingmaker waswritten in third person. To this day, Godwine is my favorite character, and hefelt like a member of the family. We got close and personal; I even delved intohis love life. Very little is known about his origin, and I made him my own, Iguess I could say. This was the first book of a trilogy, though I hadn’tplanned that initially. But by the time I got to the end, I realized the storywas only halfway written. What about the sibling rivalry between his sonsHarold and Tostig, contributing to the catastrophe that was the NormanConquest? This was a story I needed to tell, and more importantly, I thoughtthat Tostig was given a “bad rap” by historians.

Actually, I had taken a twenty year breakafter Godwine to pursue a career, then started writing again around 2005. I hadalmost forgotten that I had started the next book of the trilogy, and when Ifound it on my closet shelf, I was surprised to see that I had written it infirst person from Harold's point of view. Where did that come from? I wasreally surprised. But the more I thought about it, I realized I must have beenon to something. What better way to explain their conflicts than tell theevents from their own points of view? Tostig needed equal time! And, frankly,the other brothers did not play an insignificant role in the mid-eleventhcentury. So I told books two and three as personal memoirs, each writing theirstory for their sister’s benefit, who would set the record straight in her Life of King Edward. The Life was a real book about Edward theConfessor, commissioned by Queen Edith, though even at the time the first halfof the book became a history of her own family. So I had a bona fide opportunityto make this work.

My chapters alternated between all fivesons of Godwine (excluding Swegn, who died early on). So I had to give each ofthem a distinct voice, which was much more difficult than I anticipated. I’llnever do that again! It also meant that book one of the trilogy was in thirdperson and book two and three were in first person. I caught some criticism forthat. But I honestly felt I couldn’t do it any other way. Again, perhaps I wasable to dive into their heads because there is so little historical informationavailable, so they were open to interpretation.

Then I jumped 300 years into the futureand wrote two books about King Richard II. There was considerably more materialavailable about him, which gave me direction but also defined the man. It's notwise to detour from established histories—unless they conflict—and a person'sactions will define their personality. Interestingly enough, Richard kepthimself at a distance from me. I wrote this book in third person omniscient,but even so I had a hard time getting into his head. King Richard has come downto us as a tyrant, unstable and vindictive. But he was so much more! And hereally had the proverbial cards stacked against him, from taking the crown at ageten, to the peasants’ revolt at fourteen, to struggling against powerful andcontrolling uncles. I would say he insulated himself against almost everyoneexcept his queen. Is this why he seemed so remote to me? Was it because he wasa king that I felt unworthy to make assumptions about him, as though he wasuntouchable? Once again, I found myself trying to vindicate this sorelymisunderstood historical character. Unfortunately, he may have been beyondexoneration, but at least I tried to explain his motives.

Then I moved on to King Henry IV,Richard’s usurper. I didn’t feel the same distance from him. Was it because hewasn’t supposed to be a king? He was just a normal guy—well, not really—who wasthrust into an uncompromising situation. Henry spent most of his reign fightingone rebellion after another—mostly because of the usurpation. It destroyed hishealth and made him a sympathetic character. Perhaps that’s why he wasapproachable?

But then there was his son, the famous andreserved Henry V, hero of Agincourt. There is a tremendous amount ofinformation about him, which makes my job both easier and harder. Once again, Ifound him to be an arms-length king. Was it because of his personality? He wasgreatly respected and feared. He was fair but ruthless. I tried to write abouthim in third person, but he was so distant I felt like the book was toneless.So on the second draft, I made a detour and told the Henry parts from hisbrother Humphrey’s point of view. This took some serious rewriting! The rest ofthe book is in third person; it was important to describe the chaos in Francethat made it so easy for the English to invade. So when Henry was in thepicture I needed to start a new chapter, narrated by Humphrey. It worked,fortunately. Henry was still at arm’s length, but he was closer to his brotherthan to me—though Humphrey also found him inscrutable at times. That's allright; it could be Humphrey's lack of insight at work here, not my own.

So my journey into biographical fiction isa bumpy road for me. One would think, since I’m in charge here, that I wouldhave a handle on every one of my own characters. But I suppose, since they werelarger than life in real life, their personality took control. They can'teasily be defined. The more documentation I find about a historical person, theless leeway I'm given. I had better stay away from the 20th Century!

Website: http://www.MercedesRochelle.com

Blog Host, Helena P. Schrader, is the author of

the Bridge to Tomorrow Trilogy.

The first two volumes are available now, the third Volume will be released later this year.

The first battle of the Cold War is about to begin....

Berlin 1948. In the ruins ofHitler’s capital, former RAF officers, a woman pilot, and the victim of Russianbrutality form an air ambulance company. But the West is on a collision coursewith Stalin’s aggression and Berlin is about to become a flashpoint. World WarThree is only a misstep away. Buy Now

Berlin is under siege. More than twomillion civilians must be supplied by air -- or surrender to Stalin's oppression.

USAF Captain J.B. Baronowsky and RAF FlightLieutenant Kit Moran once risked their lives to drop high explosives on Berlin.They are about to deliver milk, flour and children’s shoes instead. Meanwhile,two women pilots are flying an air ambulance that carries malnourished andabandoned children to freedom in the West. Until General Winter deploys on theside of Russia. Buy now!

Based on historical events, award-winning and best-selling novelistHelena P. Schrader delivers an insightful, exciting and moving tale about howformer enemies became friends in the face of Russian aggression — and how closethe Berlin Airlift came to failing.

Winning a war with milk, coal and candy!

January 19, 2025

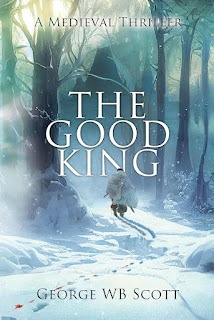

Historical Figures in Historical Fiction - A Guest Entry from George WB Scott

George WB Scott was born in Stuart, Floridawhere he lived until he went to college in North Carolina. After graduation fromAppalachian State University, he went into television news in Tennessee and is now an independent video producer and writer, living in Knoxville with hiswife Mary Leidig. He has written a childhood memoir,"Growing Up In Eden," and two historical novels, "I Jonathan, aCharleston Tale of the Rebellion," and "The Good King, A MedievalThriller." He is currently workingon a novel set in Ohio, Texas, France and Florida during the first half of the20th century. Today he shares his insights on including historical figures into historical fiction.

NOT TRUE, BUT DEFINITELY NOT FAKE

"I pledge myself not to fakeanything."

This is a 1971 quote from renowned authorJames Michener in an interview by the Academy of Achievement. Michener is aninspiration to me, and to many writers. Historical fiction writers try to getit right, while building characters and situations to tell the author'sstories.

When I wrote "I Jonathan," myfirst historical novel, I spent more than a decade reading, studying, workingto get it right, not to "fake" anything.

The challenge as a writer is to put acharacter into a believable world based on facts, as best we can know them fromour vantage point. And we all come from "another where and when," aswe craft the story in another time. So we must do the best we can to faithfullyrecreate the world inhabited by our characters.

My book's main character is fictional. Hecomes from a different culture (New England and France) to the American Southduring the American Civil War. Jonathan very briefly encounters Robert E. Leein Charleston, in 1861. He was commander of the Southern forces aroundCharleston early in the war, and helped save some buildings during the greatfire. This is documented.

Vice President John C. Breckinridge appearson his presidential campaign, and other prominent people are at some point onthe scene. They are often peripheral characters whose presence would be hard toignore in those times. They did not drive the story, and are used more forauthentic atmosphere of the times than active elements.

Jonathan, foreign to this culture, is awitness from Boston to an ostensibly Christian society based on kindness andcharity, learning how it justifies holding thousands of fellow humans inpermanent and hereditary bondage. For profit. This is one of his conflicts, andI must build a credible world for him to interact with.

My research includes subjects that are notusually part of the popular mystique of the Old South—particularly the LowCountry. The book explores occupations of the hundreds of free Blacks in thetown, the Jewish population in Charleston, and the lives, work andentertainments of the common people. I include some individuals representingtypes or categories, such as a root doctor, a military observer in the belltower of St. Michael's Church, Irish merchants, workers and policemen, and ablockade-running sea captain who was patterned after an actual personality.These characters are often composites, with traits of multiple historicalcharacters.

As Jonathan meets historical figures likeU.S. Army Major Robert Anderson at Fort Sumter, the photographer George Cook,and Abner Doubleday who many readers will know as the "inventor ofbaseball (false)," he learns about Charleston and environs. These and thehistoric figures are the texture, the touchstones for the tale of a young mancoming to terms with his own beliefs, doubts and feelings.

Robert Smalls is also documented. He laterbecame a South Carolina legislator and is best known for his theft of the steamtransport "Planter." His actions give another fictional character onboard ship the platform to justify rebellion from his own family and enslavedsituation.

Clara Barton, who later founded theAmerican Red Cross, makes a fleeting appearance across a beach after a terriblebattle where she actually tended U.S. troops. She and a fictional nurse fromthe opposing side share a distant, silent wave and lend Jonathan a moment toreflect on a feminine view of the folly of men.

Some scenes are drawn from history,especially from Mary Chesnut's invaluable "A Diary from Dixie," andfrom historical records, such as the bombardment of Fort Sumter by the UnionNavy, and battles of Secessionville and Battery Wagner. One social party is myre-creation of an event that was attended by Mrs. Chesnut. Maimed officers inattendance are commented on by young women watching their men diminished by thethen-current "unpleasantness" of war. "Oh, he has his eye outfor you," and of a one-armed soldier, "He is going to ask for yourhand."

Building a story around the dramatic eventsof a well-documented series of events such as Civil War Charleston can be anadvantage. The writer can "hang the story on the bones of history,"as the expression puts it. Indeed, much of my inspiration came from amicrofiche film of The Charleston Courier newspaper held in the library of theUniversity of Tennessee.

My second historical novel is verydifferent, as the history in 10-century Bohemia is decidedly less detailed. Ina way this is very liberating, as I can use the few historical elements tocreate an almost wholly fictional story employing the very few facts we know ofthat time and place.

"Good King Wenceslas" is afavorite Christmas song about a little-known saint and leader of ancientPrague. His basic story is one of grace, with a tragic end. The historicalcharacters offer a mostly blank slate. I based the novel on chronicles andlegends of a beatific figure who performed acts of kindness and even miracles.His younger brother is almost wholly unknown except for the castles andchurches he built, and that he cold-bloodily murdered his older sibling. Theyboth were children of a totally evil pagan princess, whose grasping claim topower drove her to do any vile thing to regain it. The brothers are also thegrandchildren of the very real Saint Ludmila, a pivotal figure who broughtadvanced agriculture and Christianity to their country.

With these historic people and a fewdisembodied names associated with the legends, I discovered a basic story andstock of characters I could mold into a plausible drama. I researched Slavicpagan religions, academic archeology and anthropology, folk tales, and elementsof more modern traditional Czech life. I built these into a stew of palaceintrigue and internal conflict. Finally it developed into a coherent story witha resolution, or at least the striving toward one. Such was my goal.

Much of my research involveshistories—books and articles, and there is a great range of readability. I'vealways loved history, and know that even some famous writers may put lots ofinformation into exciting narratives. And many simply provide lots of information.Writers like Eric Larson can take mundane events around a dramatic happeningand craft riveting accounts. Barbara Tuchman gave us medieval Europe through aflashing prospect. Others may do exhaustive research on a president or otherimportant person and compose a manuscript, a trough of molasses that the readermust slog through, held between the covers of a book.

My own great-uncle Lawrence Schoonoverwrote historical fiction that mostly upheld the goals of Michener, "not tofake," but built new stories, novels, based on the real, on kings andpashas, queens and heroes. Historical facts are served as side items on agleaming platter of a savory main course.

C.S. Forester wrote the thrilling HoratioHornblower series and took us into the world of sailing ships of the Napoleonicera. Admiral Nelson, as I recall, made only a brief appearance. His are newstories, solidly based on the naval publications of the period—real events.

Even writers of fantasy must have someidentifiable framework to build on. J.R.R. Tolkien's wonderful world of MiddleEarth is solidly based on European legends and epics, as well as those of theMiddle East. His works even have elements of Biblical, Native American, FarEastern and African traditions. Frank Herbert's "Dune" series has thevibes of palace intrigue from medieval European royal courts.

I love Michener because he was unafraid totackle the big issues, the big stories. And he wrote so many by telling thelittle stories, the ones of the people peripheral to the main event. Hischaracters surround the larger historical figure of the king, or the general,the chief, the emperor. We learn much by listening in the head of the servingboy, the concubine, or the soldier, where we see the trials of the time throughhis more personal experiences. I first read "Hawaii" when I was aboutfourteen, and I was hooked. Historical fiction! And hundreds, thousands writein that genre. Worlds to discover!

Novels are, by their very name, "newstories," so the reader expects that all aspects are not "true."But in the words of Michener, good historical novels are "not fake."

I use old newspapers for background when Ican. I particularly like "Chronicling America" Library of Congresswebsite. The "LOC" has historical maps for geographical references.Interlibrary loan is also valuable. Go online and discover what you can findthrough your local library.

So, to writers of historical fiction, theobvious advice from the masters is: do your research, verify your facts, andcreate your own (new) story.

Your historical novel—your new story—canbe, if not quite true, definitely not fake!

Find out more about George at: https://www.amazon.com/stores/author/...

Find out more about George at: https://www.amazon.com/stores/author/...

Blog Host, Helena P. Schrader, is the author of

the Bridge to Tomorrow Trilogy.

The first two volumes are available now, the third Volume will be released later this year.

The first battle of the Cold War is about to begin....

Berlin 1948. In the ruins ofHitler’s capital, former RAF officers, a woman pilot, and the victim of Russianbrutality form an air ambulance company. But the West is on a collision coursewith Stalin’s aggression and Berlin is about to become a flashpoint. World WarThree is only a misstep away. Buy Now

Berlin is under siege. More than twomillion civilians must be supplied by air -- or surrender to Stalin's oppression.

USAF Captain J.B. Baronowsky and RAF FlightLieutenant Kit Moran once risked their lives to drop high explosives on Berlin.They are about to deliver milk, flour and children’s shoes instead. Meanwhile,two women pilots are flying an air ambulance that carries malnourished andabandoned children to freedom in the West. Until General Winter deploys on theside of Russia. Buy now!

Based on historical events, award-winning and best-selling novelistHelena P. Schrader delivers an insightful, exciting and moving tale about howformer enemies became friends in the face of Russian aggression — and how closethe Berlin Airlift came to failing.

Winning a war with milk, coal and candy!

January 13, 2025

Historical Figures in Historial Fiction - A Guest Post by Patsy Trench

Patsy Trench took up writing books in herlater years. To date she’s published three non fiction books about the earlydays of colonial Australia, based on her ancestors, five novels featuring womenin the past misbehaving, and a collection of short stories about love inadversity. In a previous life she has been an actress, a scriptwriter, script editor,lyricist, a co-founder of The Children’sMusical Theatre of London, a teacher and a tour organiser.

Today she tells us:"HowNoel Coward made a surprise appearance in my novel."

It was my first historical novel,set in England in the 1920s – The Roaring Twenties as it became known. Thecentral character, a woman in her fifties and a mother of three, named Claudia,was as a result of a chance encounter breaking out of the her reticent shelland discovering a rapidly-changing world around her. She was attending a partyat the home of her eldest daughter, quite a challenge for a reserved lady likeherself, surrounded by all these vibrant young things Charlestoning and‘Black-Bottoming’ to the latest American music blasting from a brand newcontraption called a gramophone. Then in the midst of all this there’s a suddenhush and in walks Noel Coward.

Coward, born in the last year of the nineteenth century, wasin his early twenties at the time and was at the beginning of his careeralready beginning to make a name for himself as an actor, a performer and aplaywright. His appearance – both at this party and in my book – came as asurprise to everyone, including the author.

On spotting Claudia, the only older woman in the room, hehomed in on her and began to quiz her in a disarming yet decidedly intimateway. It appears he’d written a play – for which he was struggling to find atitle – featuring a woman of a certain age who had fallen in love with ayounger man, to the disgust of her drug-addicted son, and he (Coward, that is)wanted to know what someone like Claudia would make of it. Never having been inthat situation herself Claudia did her best, and most useful of all, she suggesteda title for the new work: ‘The Vortex’.

It was the only time she actually met Coward in the courseof the book, although later, sitting in the waiting room in a railway stationwaiting for her train she spotted a man of roughly her age gazing in herdirection rather mournfully, and reminded of the conversation she’d had withNoel Coward she began to fantasise a scenario in which the sad-looking man hadjust said a heart-wrenching goodbye for the last time to a woman he’d met righthere in this waiting room, whom he loved passionately yet hopelessly, asneither of them could leave their respective spouses. She pondered on the titleand came up with ‘Brief Encounter’ and made a mental note to pass it on toCoward if she ever saw him again.

All this was nonsense, of course, and I made it clear it wasnonsense in a note in the book. Why Coward made his surprise appearance I haveno idea, it really wasn’t planned. I just fancied the notion of including areal-life person into my fictional world, perhaps to give it a context, perhapsbecause before this I had been writing non fiction, about real people, perhaps becauseof all the people I could think of no one personified more precisely the imagewe all have of the Roaring Twenties than Noel Coward.

Having done it once I did it again with my other novels.Novel number 2 featured the actress Mrs Patrick Campbell, the founder of thesuffragist movement Mrs Millicent Fawcett and several members of the Bloomsburyset, including in particular Lady Ottoline Morrell and John Maynard Keynes.Novels 3 and 4 featured my favourite character of all, the actor-managerHerbert Beerbohm Tree, the man who built Her (now His) Majesty’s Theatre in theHaymarket in London, who lit up the West End with his lavish, extraordinaryproductions of anything and everything from Shakespeare to extravaganza. Aneccentric with a colourful private life, a generous, humorous, kind yet unpredictableman who disarmed and infuriated everyone he met. The original Professor Higginsin Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, lateradapted into the musical My Fair Lady. BeerbohmTree was simply irresistible.

The title of novel number four, Mrs Morphett’s Macaroons, about a play of the same name featuring alady’s maid who becomes a suffragette, was a spoof on Mrs Millicent Fawcett(the lady in question was called Lady Phillicent Morphett: you can see how sillyit all was).

Needless to say all these real characters were meticulously researched; that was partof the fun as I love researching.Delving into their lives was a useful and delightful way of immersing myself inthe times in which they lived.

Maybe, now I come to think of it, I’m featuring these peoplebecause – fearful thought – they are more interesting than the ones I inventmyself. Truth is stranger than fiction after all, if I had tried to invent aman like Beerbohm Tree no one would have believed me.

In the end, if I examine my sub conscious, what perhaps I’mreally trying to do is introduce readers to people in the past who I happen tofind particularly fascinating, to keep the memory of them alive, in my ownsmall way. I’m not sure that was in my mind when they first walked into it butit’s there now. I’ve switched to non fiction for my current project, but in theback of my mind is the thought – who of these real people will I include in mynext novel?

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0B5NJSH8R

(Link to my 5-book series titled Modern Women Breaking theMould)

Blog Host, Helena P. Schrader, is the author of

the Bridge to Tomorrow Trilogy.

The first two volumes are available now, the third Volume will be released later this year.

The first battle of the Cold War is about to begin....

Berlin 1948. In the ruins ofHitler’s capital, former RAF officers, a woman pilot, and the victim of Russianbrutality form an air ambulance company. But the West is on a collision coursewith Stalin’s aggression and Berlin is about to become a flashpoint. World WarThree is only a misstep away. Buy Now

Berlin is under siege. More than twomillion civilians must be supplied by air -- or surrender to Stalin's oppression.

USAF Captain J.B. Baronowsky and RAF FlightLieutenant Kit Moran once risked their lives to drop high explosives on Berlin.They are about to deliver milk, flour and children’s shoes instead. Meanwhile,two women pilots are flying an air ambulance that carries malnourished andabandoned children to freedom in the West. Until General Winter deploys on theside of Russia. Buy now!

Based on historical events, award-winning and best-selling novelistHelena P. Schrader delivers an insightful, exciting and moving tale about howformer enemies became friends in the face of Russian aggression — and how closethe Berlin Airlift came to failing.

Winning a war with milk, coal and candy!

January 6, 2025

The Challenges and Rewards of Writing Historical Figures into Historical Fiction

This is the first entry in a new series about the challenges and rewards of integrating real people into works of historical fiction. Each entry will open with a brief introduction to the contributor and end with information about one of their published works. But first some background information about the topic of the series.

In the widest sense of the term, historical fiction is any work of fiction in which all or part of the action takes place in an historical setting. For vast numbers of historical novels, probably the majority, only the setting and background events are in any sense "historical." For example, a romance about a nurse and a sailor set in Hawaii in 1941 is certainly historical fiction. Yet even if it describes in great and vivid detail the Japanese attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, it need not include a single historical person -- famous, infamous or obscure.

Yet sometimes, we novelists do choose to include -- or even focus on -- real historical figures.

Novels that seek to depict the life and character of a historical personage in comprehensive detail are an important sub-genre of Historical Fiction, namely Historical Biography aka Biographical Fiction. Hilary Mantel's famous trilogy of novels about Thomas Cromwell is a example that is familiar to most readers. Anya Seaton's Katherine, and Sharon Kay Penman's novels about Richard I, Richard III, or Edward IV are other examples as is Robert Graves I, Claudius.Yet, there are undoubtedly many more novels in which historical figures make an appearance although they are are not the protagonist. In these novels, the historical figures play a subordinate role or may make only a fleeting appearance. They may seek to depict a person familiar to us from the history books in a new light by shining an indirect light on their story, that is, by telling their story through the eyes of a fictional friend, servant, or even pet, for example. Alternatively, a novel may be entirely focused on fictional characters and yet in a single episode include a short encounter with someone who played a role in history. Many Christian historical novels, for example, use this technique of a single encounter with Christ that transforms the life of the otherwise fictional protagonist.

For this series on "Historical Figures in Historical Fiction," I have asked other writers of historical fiction to share their experiences with integrating real people into works of fiction. I hope they will also share their reasons for blending fact and fiction and describe the challenges this brings. I'm looking forward to what they have to say and expect it will be entertaining reading for all of us!

Helena P. Schrader is the author of the Bridge to Tomorrow Trilogy. The first two volumes are available now, the third Volume will be released later this year.

The first battle of the Cold War is about to begin....

Berlin 1948. In the ruins ofHitler’s capital, former RAF officers, a woman pilot, and the victim of Russianbrutality form an air ambulance company. But the West is on a collision coursewith Stalin’s aggression and Berlin is about to become a flashpoint. World WarThree is only a misstep away. Buy Now

Berlin is under siege. More than twomillion civilians must be supplied by air -- or surrender to Stalin's oppression.

USAF Captain J.B. Baronowsky and RAF FlightLieutenant Kit Moran once risked their lives to drop high explosives on Berlin.They are about to deliver milk, flour and children’s shoes instead. Meanwhile,two women pilots are flying an air ambulance that carries malnourished andabandoned children to freedom in the West. Until General Winter deploys on theside of Russia. Buy now!

Based on historical events, award-winning and best-selling novelistHelena P. Schrader delivers an insightful, exciting and moving tale about howformer enemies became friends in the face of Russian aggression — and how closethe Berlin Airlift came to failing.

Winning a war with milk, coal and candy!

November 26, 2024

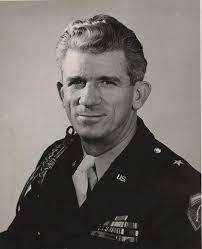

Historical Characters in "Cold War" - General William H. Tunner

No novel about the Berlin Airlift could make any claim to accuracy and authenticity without including General William H. Tunner. Although his influence was felt only in stages, as he was granted increasing authority, he was the world's greatest expert in military air transport. As Commander of the Combined Airlift Taskforce, Tunner took charge of the Airlift and imprinted his own character upon it. His innovations and his forceful personality saved the Airlift from chaos and collapse at a critical juncture.

Tunner had beenone of the first officers in the entire Air Force to specialise in airtransport. He had helped establish the Ferrying Division and nurtured it from ahandful of men to an organisation 50,000 strong and delivering 11,000 planes amonth to domestic and overseas destinations. In fact, he can be largelycredited with creating not only an organisation but an entire ethos andstandard for air transport pilots. He passionately believed that transportpilots had a different mission and required different qualities than combatpilots. He was proud to claim that he had “proved that air transport was ascience in itself; to be carried out at its maximum efficiency air transportmust be run by men who … are dedicated to air transport – professionals.” [Tunner, Over the Hump, Office of Air Force History, 1964, p. 41] He had then, in August1944, taken command the highly risky supply operation across the Himalayas – which had already defeated several previouscommanders – and turned it into a spectacular success.

Tunner also had areputation as a hard driver. His nickname was “Willy the Whip” and he claimedhe didn’t lose any sleep over it. The official air forcehistory of Air Transport Command described him as “arrogant, brilliant,competent. He was the kind of officer whom a junior officer is well advised tosalute when approaching his desk.” In short, he was boththe consummate professional air transport commander and the kind of commanderwho could be expected to get the job done – even if it was a job that theofficers appointing him did not believe could be done. For more details on his impact on the Berlin Airlift see: Tunner Takes Command.

The below excerpt depicts a first meeting between General Tunner and the RAF Station Commander Gatow, my fictional character Robin Priestman. This scene is set on August 14, a time when the airlift operations of Britain and the United States were still independent, i.e. before the formation of the Combined Airlift Task Force and before Tunner became Priestman's indirect superior.

The USAF C-54 settled down at Gatowfour minutes late and was led by the “Follow-Me” Land Rover to a hardstandingwhere Priestman awaited. The engines had not stopped spinning before the dooropened and a US general in a khaki uniform and polished shoes jumped down ontothe tarmac. He was trim, modestly good-looking with regular features, and abusinesslike rather than a friendly demeanour. He returned Priestman’s salute, andhe offered his hand with the words, “Thank you for seeing me at such shortnotice, Wing Commander.”

“Everything is short notice on thisAirlift,” Priestman replied. “How can I help you?”

“Oh, I just thought I’d take a look atyour operations and see how you were handling things. If you’ll wait onemoment, my pilot and copilot are two of my staff officers. I want them to joinus.” He looked toward the aircraft and on cue, two lieutenant colonels droppedout of it to be introduced as Bettinger and Foreman.

Priestman reciprocated by introducing,“Captain Bateman, RASC, responsible for our Forward Area Supply Organization orFASO. That is, everything to do with unloading the aircraft and moving the cargoesup to Berlin.” Priestman drew attention to the fact that Tunner’s aircraft wasalready being unloaded.

Tunner turned to watch as the trailerwas backed up against the cargo door of his Skymaster. “I see you’re usingGerman stevedores, just as we do. Any problems with them?” he asked.

Priestman nodded to Bateman to answer.

“None at this end. In the early days,German loaders were didn’t understand that the cargo capacity of aircraftvaries. They knew even less about maintaining the aerodynamics of the aircraftby careful distribution of loads. Those teething problems have since been resolved.”…

Tunner snorted but nodded hisunderstanding, then looked at Priestman. Taking this to mean Tunner wasfinished with the topic of unloading, Priestman invited the Americans into hiscar and drove them over to the maintenance hangar. Here Tunner and his staffofficers met Gatow’s Chief Engineering Officer, Squadron Leader Holt. Tunner’ssharp eye rapidly noted, “You don’t have many aircraft in maintenance andalmost no spare parts inventory. Why is that?”

“All Airlift aircraft are based in theWest and that is where routine maintenance is carried out. We only maintain alimited supply of those essential components most likely to require immediatereplacement such as tyres, brakes, etc.”

“What if an aircraft lands with adifferent problem?” Tunner asked, adding, “You seem to have ample hangar spaceto manage much more maintenance.”

“Our problem isn’t space butpersonnel. We only have enough ground crew here to handle an emergency. As forspare parts, the RAF doesn’t have infinite stockpiles and what we have iscentralised at our main depot in the UK. If we lack something, it can be flownin within a couple of hours — a day at the most. As a rule, however, we preferan aircraft’s regular crew to handle all repairs during routine maintenance.”

“You have crews assigned to individualaircraft?” Tunner sounded surprised.

“That’s right.”

“Isn’t that a waste of manpower?”Although his expression was impassive, his disapproval was evident.

“How so, sir?” Holt asked defensively.

“Well, 50-hour checks only come due everyfive or six days. What is the crew doing in the meantime?”

Priestman took over from the rattledHolt, “Squadron ground crews handle two aircraft each and the RAF requiresdaily inspections. In addition, squadron ground crews do the 150-hourinspections which come up roughly every fortnight. Our ground crews are workingtwelve-hour days. There’s no question of them lazing about.”

“You still do daily inspections? Thatseems over-cautious. We’ve found fifty-hour checks are adequate to correctminor issues and identify major ones,” Tunner countered.

Priestman was unimpressed. “Ourphilosophy is to carry out preventive not merely corrective maintenance. Weprefer repairing an item in time rather than waiting for it to break down andneed replacing.”

“That sounds like an admirableapproach in peacetime, Wing Commander, but in war — or warlike conditions suchas we have here — the primary concern must be maximum utilization of assets.That means aircraft should be flying, loading/unloading or undergoingmaintenance. They shouldn’t be sitting around on the ground being inspected forproblems they don’t yet have. My preference is to give them a thorough check at200 hours. I’ve arranged for the C-47s to go down in Oberpfaffenhofen and theC-54s to fly to Burtonwood.”

That sounded as though it would takeaircraft off the Airlift longer than the RAF’s daily inspections, but Priestmanchose not to challenge the “expert.” Instead, he suggested they move on.

The tour continued to the MalcolmClub. Priestman explained that station personnel used the messes, while theMalcolm Club served the crews waiting for their aircraft to be unloaded. “TheSalvation Army, NAAFI and YMCA also offer quick snacks from mobile canteens onthe airfield or beside the maintenance hangars, but here men can sit down andget a bit of peace and quiet. They also have a barber shop if someone wants ahaircut while waiting, and the lounge is well-stocked with newspapers andperiodicals.” Priestman proudly pointed to a table where these were displayed.“If an aircraft is stranded here overnight, the club offers limited butcomfortable accommodation.”

Tunner looked around the roomcritically. “The problem with nice places like this is that the crews get tochatting and smoking and reading when they ought to be flying. As of yesterday,my crews have orders not to move more than 10 feet away from their aircraft.”

“I’m sure that’s popular,” Priestmannoted.

“I’m not here to win a popularitycontest,” Tunner shot back. “As I said a moment ago, I want maximum utilizationof assets, and that includes pilots.”

“And how do they get the weatherreport and file a return flight plan?”

“I send a jeep around with theoperations officer, another with the weather report, and finally, a mobilesnack bar manned by the prettiest girls the Red Cross could recruit in Berlindrives from plane to plane. The men don’t seem to be bitching too much.”

Priestman nodded acknowledgementrather than approval and asked if his guests wanted a tour of the full stationincluding accommodations, messes, and recreational facilities, or if theypreferred to go straight over to the meteorology section, operations room andthe tower. Unsurprisingly, Tunner opted for the latter.

As they mounted the steps of the mainbuilding, Tunner remarked, “I’ve asked my staff to work out new trafficpatterns in the corridors, and I hope the RAF will cooperate… For a start,one-way traffic. Everything flies in via the northern and southern corridorsand out via the central corridor.”

“That would be a great improvement andsomething I suggested long ago,” Priestman noted dryly. Tunner gave him asecond look, but Priestman kept his eyes averted.

Tunner continued, “You’ve probablyalready heard that I’ve ordered all pilots who miss a landing to return fullyloaded to avoid stacking up aircraft in the limited airspace over Berlin — andwoe betide any pilot who misses his landing without good reason!”

Priestman nodded without commentary.He was not as averse to stacking aircraft as Tunner and felt sending loadedaircraft back was a waste of aviation fuel that also delayed the delivery ofdesperately needed supplies to Berlin. He conceded that in a situation such ashad developed at Tempelhof yesterday, it was preferable to an accident, but hethought the decision should be made on a case-by-case basis.

Tunner next remarked, “I’ve asked thePentagon to call up one hundred civilian air traffic controllers and send themover to improve the quality of the ATC. Some of our guys just aren’texperienced enough for this environment.”

Priestman nodded agreement wordlessly.

Tunner wasn’t finished, “I’ve also putin a formal request via General LeMay to Air Marshal Sanders to base a bunch ofour aircraft in your Zone.”

That brought Priestman to a halt, andhe looked over at the American surprised.

“Look, the distance to Berlin fromeither Wiesbaden or Rhein-Main is roughly 300 miles while it’s just over 120miles from Celle or Fassberg and less than 100 from Hamburg. The same aircraftcan make three trips to Berlin from Fassberg in the time it takes to make twosorties from Rhein-Main. That’s 50% more.”

Priestman nodded and conceded, “Thatmakes sense.”

“What it means is that most of thoseplanes will be funnelled down the northern corridor and directed into Gatow,starting one week from today.”

“Ah, I see. That’s why you were sokeen to visit,” Priestman concluded with a faint smile.

“That was one reason. The other is thata C-74 is arriving today at Rhein-Main with vitally needed engines and otherbulky replacement parts. Some genius in the Pentagon came up with the idea ofstuffing it full of flour — after we’ve unloaded those special cargoes — andsending it on to Berlin. The problem with that is it’s far too heavy to land onthe PSP runways at Tempelhof. If we’re going to make a show — and that’s allthis is since the brass refuses to dedicate any C-74s to the Airlift — it isgoing to have to take place here at Gatow.”

“I see,” Priestman commented dryly. Hedidn’t like having something like this sprung on him at such short notice.

Tunner could read his mood and triedto make the event more palatable. “It wasn’t my idea, but to be fair, somethinglike this will highlight that this is a joint effort — even if it is still,irrationally, two separate operations.”

Intentionally or not, Tunner had justshown his hand. The American general wanted a combined operation. Morespecifically, he wanted to control not just the U.S. aircraft and airfields butthe British ones as well. That way they would all have to dance to his tune.

Priestman had mixed feelings aboutthat. He could see the sense in many of Tunner’s suggestions and disliked Bagshot’ssmall-minded approach to problems. Yet the American general also struck him as rigidand adverse to alternative approaches. Tunner appeared to believe he had allthe answers already. Most damning, his obsession with “maximum utilization ofassets” struck Priestman as almost inhuman.

Tunner, P. 41.

Tunner, p. 110.

Oliver LaFarge, The Eagle inthe Egg, p.26.

Tunner is a character in the Second two volumes of the Bridge to Tomorrow Trilogy

Berlin is under siege. More than twomillion civilians must be supplied by air -- or surrender to Stalin's oppression.

USAF Captain J.B. Baronowsky and RAF FlightLieutenant Kit Moran once risked their lives to drop high explosives on Berlin.They are about to deliver milk, flour and children’s shoes instead. Meanwhile,two women pilots are flying an air ambulance that carries malnourished andabandoned children to freedom in the West. Until General Winter deploys on theside of Russia. Buy now!

Based on historical events, award-winning and best-selling novelistHelena P. Schrader delivers an insightful, exciting and moving tale about howformer enemies became friends in the face of Russian aggression — and how closethe Berlin Airlift came to failing.

Winning a war with milk, coal and candy!

November 19, 2024

"The Berlin Candy Bomber" Lt. Gail Halvorsen

The Bridge to Tomorrow Series includes several historical characters. None of these is more important that Lt. Gail Halvorsen, a man who has gone down in history as "the Berlin Candy Bomber."

Lt. Gail Halvorsen joined the U.S. Army Air Corps during the Second World War and flew transport planes out of Natal, Brazil. A military professional, he was still flying transport planes in 1948 when the crisis in Berlin erupted. Halvorsen arrived in Berlin in early July when the Airlift was only a couple weeks old and the crews had been told the situation wouldn't last more than 25 days or so. Halvorsen was anxious to see some of the famous capital of Hitler's Germany from the ground before getting sent home to the States. So one day, instead of sleeping, he hitch-hiked on another C-54 and flew to Berlin as a tourist.

The first thing he wanted to do was get a snap-shot of the way the cargo planes barely scraped over the tops of the surrounding five-story apartment buildings to land at Tempelhof airfield. So Halvorsen walked around to the opposite side of the airfield from the terminal to take a photo from right beside the perimeter fence. Here he found about 30 German kids hanging on the fence and watching the planes land. Halvorsen became involved in a conversation with these kids and was impressed both by how well they understood about what the political situation -- and by the fact that they didn't try to bum any candy or gum off him. He decided then and there to bring them some more candy so they could all have some. Knowing he couldn't get away from his plane, he said he'd drop it from his aircraft on approach.

The first thing he wanted to do was get a snap-shot of the way the cargo planes barely scraped over the tops of the surrounding five-story apartment buildings to land at Tempelhof airfield. So Halvorsen walked around to the opposite side of the airfield from the terminal to take a photo from right beside the perimeter fence. Here he found about 30 German kids hanging on the fence and watching the planes land. Halvorsen became involved in a conversation with these kids and was impressed both by how well they understood about what the political situation -- and by the fact that they didn't try to bum any candy or gum off him. He decided then and there to bring them some more candy so they could all have some. Knowing he couldn't get away from his plane, he said he'd drop it from his aircraft on approach.The "rest is history" (as the saying goes) and you can read more details at: https://europeanaviationhistory.blogs...

Below is an excerpt which depicts Lt. Gail Halvorsen's first candy drop seen through the eyes of my fictional character J.B. Baronowsky:

“The oldest of these kids couldn’t have beenmore than twelve,” Halvorsen stressed to his copilot in a breathless, excitedvoice. “The littlest was about eight. Yet every one of them understood thatthis Airlift isn’t about food but freedom! It was amazing!” The American pilotswere sitting together in the mess having a quick meal before bed. Halvorsen hadjust returned from his off-duty trip to Berlin.

“Yeah,” J.B. agreed. “That is pretty amazing. Wheredid you say you ran into these kids?”

“They were hanging onto the perimeter fenceright at the end of the runway. I’d gone over there to try to get a picture ofa C-54 landing over the apartment houses, and they were clinging to the outsideof the fence. They said they live nearby and come to watch the planes everyday.”

“And what did they say aboutfreedom, exactly?” J.B.’s scepticism was reflected in his voice. The kids heknew didn’t care about politics.

“Well, there was this little girl with blondpigtails wearing hand-me-down trousers from probably more than one older brotherand she said, ‘When you bombed us and killed some of our parents and sistersand brothers —”

“She said that to your face?” J.B. askedhorrified.

“Yeah, and then she went on—”

“Wait a minute! Didn’t you correct her? Didn’tyou tell her you hadn’t flown bombers in the war? That you hadn’t even beenin the European theatre?”

“No, that wasn’t important. What’s importantis what she said. Listen to me, J.B.! She said, that during the bombing, they’dthought nothing could be worse than that — until the Russians came. She saidsomething like, ‘After the final battle for Berlin, we saw what the Russiansdid in the city before you arrived. And we’ve learned more about Communismsince.’ An older boy with good English added, ‘We don’t need lectures aboutfreedom. We can walk on both sides of the city, and we have relatives who visitfrom the East. They are hungry for American newspapers and listen to RIAS.’Several then chimed in to say that everyone listened to RIAS if they could getit — East or West.”

“Yeah, RIAS has a good mix of entertainmentand information — and they have children’s programs, too.” J.B. conceded beforeasking, “Did you enjoy the rest of your sightseeing tour?” He had finished hismeal and was wiping his hands on a paper napkin. Their next flight wasscheduled to depart at 2 am and he wanted to get some sleep first.

Halvorsen nodded absently and answered betweenhis last mouthfuls of dinner. “Sure. It was interesting, although everything’spretty wrecked. The tour got cut short when we had to hightail it back in ahurry because some Reds started chasing us. Apparently, any American with acamera is treated like a spy. But I keep coming back to those kids.” He put hiscutlery down and wiped his hands on his napkin. “Here they are living on lessthan 1,000 calories a day, with no candy or chocolate or gum. Geeze, they don’teven get much sugar on the rations we give them, but not one of them tried tobum something off me.”

They both stood to return their trays with thedirty dishes, and Halvorsen continued, “Everywhere else in the world the kidscluster around — not begging exactly, but, you know, hinting that they couldsure use some candy or gum. Brazil, Colombia, Panama, wherever — the kids wouldgrin and wave and call out: ‘Hey, chum, got any gum?’ But not these kids. I’d already turned awayfrom them before I realised that they hadn’t asked me for a thing. I felt in mypockets to see what I had to share and came up with just two sticks ofWriggley’s gum — for a dozen kids! I tore the sticks in half and gave a pieceto each of the kids who’d done most of the talking. You know what they did?They passed the wrappers to the others so they could sniff it — and youshould have seen their faces! You would have thought they’d just been given awhole bowl of ice cream with hot chocolate sauce and whipped cream on top.”

The pilots put their trays on the counter forthe mess stewards and started for the shuttle to the Zeppelinheim. “When I sawthat,” Halvorsen continued casually, “I promised to bring them some candytoday.”

“Hal! We’re not allowed more than ten feetaway from the aircraft, remember? You can’t go wandering off across theairfield to give kids candy.”

“I know, that’s why I said I’d drop it fromthe plane, just as we come over the fence.”

J.B. screeched to a halt, “You said what?”Then before Halvorsen repeated himself, he added, “We can’t do that! It wouldjust get blown away and scatter all over the place. Hell, it would probably shatteron impact! We’re still 200 feet up and going 90 to 100 mph when we come overthe fence.”

“I’ve been thinking about it all the way back,and I figured we could make little parachutes out of handkerchiefs.”

“Hal, you’re crazy. Sleep deprived, that’swhat. Let’s get some shuteye, and you’ll feel better and see things straight whenyou wake up.”

They returned to their quarters in the oldbarn. J.B. stripped down to his undershorts, rolled himself into his blanketand was out like a light. When he woke up, he was dismayed to find that insteadof sleeping Halvorsen had been fashioning tiny parachutes from hishandkerchiefs. “They work too!” he assured J.B. “I tested one from the windowof the loft.” Then with one of his irresistible, shy smiles, he asked, “Youwouldn’t happen to have any left-over candy or chocolate bars, would you? I’ve stillgot six parachutes.”

Shaking his head, J.B. handed over all hiscandy rations, but he warned Hal. “If anyone finds out about this, we are goingto get into a heap of trouble. Hell, Tunner’s such a stickler for regulations,he’ll probably court-martial us for something like this.”

“He’ll never find out,” Halvorsen insisted.

Soon they had Sergeant Elkins’ candy rationtied to parachutes too, and they hid the lot in Elkins’ tool kit. Promptly, attwo am they took off for Berlin, arriving before dawn. The C-54 was unloadedwith the usual efficiency, while they waited beside it, receiving one jeepafter another with the weather and paperwork that went with each flight. Theybought coffee at the mobile snack bar when it came by, and then flew back toFrankfurt. Here the routine was repeated with them waiting near the aircraft asit was loaded with a cargo of powdered vegetable soup and then they were in thecorridor again. It was approaching noon when they entered the traffic patternfor Tempelhof.

Halvorsen hadn’t slept a wink that J.B. hadseen, and he was very keyed up. J.B. had never seen him like this before. Hewas licking his lips every few seconds and leaning forward in his seat as hesquinted against the sun. Then, sounding as excited as a kid, he exclaimed: “Therethey are! There they are!” He pointed ahead toward the airfield coming intoview as they dropped down on their steep glide path over the apartmentbuildings. Sure enough, about thirty kids of all shapes and sizes wereclustered at the perimeter fence and staring upwards at the approaching cargoplanes.

“Sergeant Elkins, go back and prepare to dropthe parachutes when I tell you to,” Halvorsen ordered.

“Are you really going to go through with this?”J.B. asked.

“Yes,” Halvorsen’s tone brooked nocontradiction, and Elkins, shaking his head but grinning, retreated to thecabin where the parachutes waited near the flare-chute.

Halvorsen started wiggling the wings of theheavily loaded freighter; that is, rolling ten to degrees first in onedirection and then the other several times in succession.

“The tower is going to think we’re drunk asskunks!” J.B. groaned, but his words were lost on Halvorsen. He was grinningfrom ear to ear as the kids started jumping up and down and waving like crazy.

“What if one of the aircraft waiting fortake-off gets our number?” J.B. asked anxiously.

Halvorsen answered with: “Give me full flapsand 1800 RPM!”

Rolling his eyes, J.B. followed orders and asthey almost stalled out over the end of the runway, Halvorsen called to Elkinsover the intercom, “Now!”

Elkins answered with: “Bon-bons away!”

An instant later their tyres screeched on therunway and the nose wheel flopped down, but they had no way of seeing if theparachutes had landed near the children, never mind if they’d been retrieved.

Halvorsen is a character in "Cold Peace" Only

Berlin is under siege. More than twomillion civilians must be supplied by air -- or surrender to Stalin's oppression.

USAF Captain J.B. Baronowsky and RAF FlightLieutenant Kit Moran once risked their lives to drop high explosives on Berlin.They are about to deliver milk, flour and children’s shoes instead. Meanwhile,two women pilots are flying an air ambulance that carries malnourished andabandoned children to freedom in the West. Until General Winter deploys on theside of Russia. Buy now!

Based on historical events, award-winning and best-selling novelistHelena P. Schrader delivers an insightful, exciting and moving tale about howformer enemies became friends in the face of Russian aggression — and how closethe Berlin Airlift came to failing.

Winning a war with milk, coal and candy!

November 12, 2024

Historical Characters in "Cold War" - Frank Howley

The Bridge to Tomorrow Series includes several historical characters. One of these is the American Commandant in Berlin, Colonel Frank Howley. In the immediate post-war era, no Western figure was more consistently or more vehemently maligned and insulted by the Soviets than Howley -- and Howley was proud of it. He earned Soviet ire and the love of the Berliners -- 'though not always his superiors -- for his words and deeds as the American Commandant of Berlin 1945-1949. Without doubt he was one of the more colorful -- and controversial -- historical figures involved in the Berlin Airlift -- and I couldn't resist including him in the Bridge to Tomorrow Series as a character.

Nothing in Howley's background ordained him for the role he was to play in Berlin's history. Born in Hampton, New Jersey in 1903, Howley attended Parson's School of Fine and Applied Arts. He spent time time studying business and art at the Sorbonne in Paris before obtaining a BS in Economics from New York University. He then worked as an advertising executive, establishing his own firm in Philadelphia the 1930s, which proved highly successful despite the depression. Somewhere along the line he taught himself five languages, but not notably not German.

In the Second World War he initially commanded an Air Corps ground school, but he was not interested in flying and transferred to the cavalry. By 1943, he had been promoted to lieutenant colonel and was serving as the Executive Officer of the Third Mechanized Cavalry, but he was involved in a motorcycle accident in which he broke his back and pelvis. After five months in hospital, he was released but was not rated fit for active duty with a combat unit. Given the option of retiring or taking an assignment in the Civil Affairs division, which was responsible for re-establishing civil administration in occupied territory in the wake of anticipated Allied battlefield victories, Howley chose the latter. The task he had taken on was described cogently as "...to sweep into newly liberated territories and impose order on chaos, repairing shattered infrastructure and feeding starving civilians."

After training in the U.S. and the U.K. Howley landed in Normandy four days after D-Day as head of a mixed British-U.S. unit designated A1A1. Working with French liaison officers, Howley's team got the civil administration of Cherbourg working within days of its liberation. His success here lead to him being given responsibility for the same role after the liberation of Paris, and he entered the French capital on the heels of the fighting troops now in command of a unit of 350 officers and men. Here his success not only earned him the Legion of Merit, Croix de Guerre and the Legion d'Honneur, it also drew the attention of General Dwight D. Eisenhower's staff. Howley was asked to head the U.S. military government in Berlin, nominally as deputy to a figurehead who was a more senior combat officer.

Clearly, taking control of restoring civil infrastructure in Berlin would be different from his role in the liberated French cities since the population was presumed to be hostile and Berlin was to be shared with the other Allies, including the Soviets. Decisions were to be taking jointly and unanimously. Even before entering Berlin, Howley worked hard the establish rapport between the designated British and American teams, but dealing with the Soviets proved more difficult. From Day 1, the Soviets showed hostility to both the Americans and British troops sent to garrison their sectors of Berlin. Details can be read elsewhere, but by the end of his first day in Berlin, Howley knew who the enemy was -- and it wasn't the defeated, traumatized and starving population of Berlin. It was the Soviets.

From that point forward, Howley never deviated from his position that the Soviets were not to be trusted and could not be won over as friends, they were adversaries and had to be treated as such. The logical corollary of such a position was to start favoring and advocating on behalf of the Berliners under constant attack from the Soviets. Howley employed every tactic he could get away with to back the democratic elements in Berlin and to expose the machinations of the Soviet Military Administration and their puppet German Communists. He consistently reported to the press Soviet attempts to bribe and coerce voters. Wisely, he established a radio stations controlled by the U.S. military government, Radio in the American Sector or RIAS. In addition, independent newspapers were encouraged and allocated paper.

Meanwhile, the Kommandatura (where the city commandants of the four occupying powers regularly met) increasingly became a battlefield of words and exchanged insults. Howley recorded in his diary the suspicion that the Soviets were seeking to provoke a crisis. On June 16, at 11:15 pm after thirteen hours of haggling that was going no where, Howley turned his seat over to his deputy and excused himself. Describing his behavior and "hooligan," the Soviet's used his departure as an excuse to break up the Kommandatura and stormed out.

But the more the Soviets insisted in describing Howley as a "hooligan," "terrorist," "black market knight," "dictator," "cowboy," or "rough-rider from Texas," the more the Berliners loved him. He appeared the only one who shared their outrage over Soviet bullying. To be sure, Howley's style had not won him friends in Washington and his relationship with the cool and restrained General Clay were also often testy and strained. "Howlin' Mad Howley" was a epitaph applied as much by his Western colleagues as his Eastern adversaries. Yet whether one liked his style or not, he was the American who reassured the Berliners that the Americans weren't going home when the crisis came on June 24.

Such a colourful character could not be excluded from a novel about Berlin in this period! Below is an excerpt from "Cold War" in which he plays a role:

Priestman was startled to find Colonel Howley alreadywaiting in Herbert’s office. There had been a time when Herbert detestedHowley, and although they had been getting along better recently, it was still surprisingto find them together in apparent harmony. Nor did Priestman like the eagernesswith which they greeted him. Instinctively, he sensed a trap.

Herbert was a blunt man in the best ofcircumstances and got straight to the point. “Wing Commander, we asked you tomeet us today because, in view of the deteriorating situation, the Berlin CityGovernment has made a direct appeal to the Allied Kommandatura to assist in theevacuation of particularly vulnerable Berliners. What the city officials arethinking of is malnourished children, fragile, elderly people, and peoplesuffering from chronic illnesses such as asthma, arthritis, multiple sclerosis,and so on.”

“We’ve known for some time that Berlin’shospitals are in a deplorable state and understaffed,” Priestman reminded them.“You may remember that one of the civilian charter companies and our Sunderlandflying boats have been evacuating children on a small scale since earlyOctober.”

“Yes, yes,” Herbert brushed his remark asideand Priestman doubted if he had even been aware of the evacuations. Instead, heforged ahead exclaiming, “I’m sure you understand that we had no choice but toagree.”

He’d said “we” so Priestman glanced at Howley,who nodded vigorously and added, “This really must be done, Robin, and bothGeneral Herbert and I assured the mayor it would be done. What elsecould we say, for heaven’s sake? The Berliners are suffering enough as it is.How can we ask people with serious chronic illnesses, fragile old people, andkids to face a winter without heat, light or adequate rations? These aren’tsoldiers. They’re civilians.” Howley, as always, spoke forcefully.

Alarms started ringing in Priestman’s head. Hedistinctly remembered Tunner saying he would not get involved in flyingcivilians out of Berlin. Surely, the American and British Commandants had notmade promises to the Mayor of Berlin without first checking with the CombinedAirlift Task Force Commander? Out loud he asked cautiously, “Did the Mayor giveyou any indication of how many people are in these particularly vulnerablecategories that they now want to see evacuated?”

“Reuter suggested around 17,000.”

Priestman stiffened and asked at once, “HasTunner agreed?”

“No, blast him!” Herbert answered jumping tohis feet in exasperation and starting to pace with his hands behind his back.

Howley took over, explaining, “Tunner saystaking passengers on board his transport aircraft will slow down his entiresupply operation — ‘completely disrupt it’ is the way he worded it. He says17,000 people are a mere drop in the bucket and their departure will reducerequirements only marginally.”

Priestman had heard all that from Tunner himselfonly a month before, so it didn’t surprise him, even if he personally deploredTunner’s short-sightedness. For the others, Priestman pointed out, “Mathematicallyspeaking, he’s right. However, saving children’s lives is the right thing to do— from a humanitarian standpoint. Furthermore, if children, old people andpeople with chronic illnesses start dying in droves, the Soviets will be quickto accuse us of ‘mass murder.’ I doubt our political leaders would want eitherpeople to die or the Soviets to win a propaganda victory, so you’ll have to goover Tunner’s head. Have you spoken to Generals Clay and Robertson?”

“Yes,” Howley replied looking grim. “Roberstonpassed the buck, saying Americans control the Airlift since the creation of theCombined Air Lift Task Force, and Clay refused to ‘interfere.’ He said hewasn’t enough of an expert on military transport to feel he could overruleGeneral Tunner on an operational matter.”

That shook Priestman. He did not see this as astrictly ‘operational’ matter, and he had expected more understanding andcompassion from Clay.

Herbert returned to the table, sat down andfaced Priestman. “I’m pleased to hear you share my point of view on thisbecause I hope you can help us out.”

Priestman felt his pulse rate increase as hereminded the other two officers, “Tunner is my superior.”

“We know,” Howley assured him, “but hear usout. What Tunner said was that his freighters weren’t going to carry onesingle evacuee, but he added that he had no objection to the RAF taking thepassengers out.” Howley and Herbert were sitting on the edge of theirrespective seats as they awaited Priestman’s reaction.

“You’re asking me if the RAF can manage thison its own?”

“Can it?” Herbert pressed him.

“Have you asked Group Captain Bagshot?”

“No, I’m asking you, Wing Commander!” Herbert admonishedangrily. “I want your opinion as the professional who will have the mainresponsibility for implementation since all the passengers will have to departfrom Gatow. Could you evacuate 17,000 passengers on RAF aircraft and if so, howlong do you think it would take?”

Priestman did the maths out loud for them. “TheRAF aircraft most suitable for flying passengers out are the Dakotas and theSunderlands, but the latter are about to be taken off the Airlift because thefog clings to the water, reducing visibility even when Gatow is open, and wehave no radar control on the Havel. Furthermore, there is an increasing risk ofice. In short, only the Dakotas are available for an evacuation of this kind. Theycan carry between 24 and 28 passengers, but let’s be conservative and say 25passengers per flight. Weather permitting, we average a hundred Dakotadepartures each 24-hour period, but not all Dakotas can carry passengers and nightflights are extremely hazardous. So, let’s assume passengers are evacuated onjust seventy Dakota sorties per day. That would mean evacuating 1,750 peopleper day or all 17,000 of them in ten days — assuming good weather.”

“That’s jolly good!” Herbert exclaimed, evidentlysurprised, and Howley clapped Priestman on the back saying, “I knew we couldcount on you, Robin!”

“Slow down, please. Getting that many peopleout in one day, as I said, depends very much on the weather. Also, the evacueeswill have to be ready to board at a moment’s notice. They will have to be organisedin groups of 25 and can’t bring much luggage. I should say no more than onesuitcase per person weighing one and a half stone at the most. There can be noconfusion, pushing or shoving and fighting.” The other two officers nodded vigorouslyin understanding.

Priestman continued. “Nor do the problems endthere. Where are all the evacuees to go at the other end? We can’t just dumpthem on the Airlift airfields and tell them to look after themselves—”

“No, no! Of course, not!” Herbert agreed. “TheBerlin City government assured us they would organise onward transport tohospitals and homes. They said they were already doing this on a much smallerscale — is that what you mentioned earlier?”

“What we’ve done to date is evacuate roughly120 passengers per day using just one civilian company and the Sunderlandsflying into Hamburg. However, to remove 17,000 people we’ll need almost theentire RAF Dakota fleet, and it operates from a variety of different airfields.I would recommend that the evacuation flights end at the civil airport inHannover so that from there the aircraft and crews can return to their home baseto take on another load of inbound cargo for Berlin.”

“That sounds first-rate, Wing Commander!”Herbert’s relief added to his rare display of enthusiasm.

Howley nodded forcefully as well, adding,“Hannover has the added advantage of being centrally located, so the evacuees couldreadily be distributed across the West. I’m sure the City Council will agree.You’ll just need to coordinate this with them.”

“Bear in mind, furthermore, that even ifeverything goes like clockwork, embarking and disembarking passengers and theirluggage will delay return flights. That’s why Tunner wants nothing to do withit. Realistically, it means the Dakotas won’t be able to make three roundtripson a good day as they have been doing, but two. Which means I must revise myearlier calculations and say we’d need closer to fifteen days of good weatherto clear 17,000 passengers through Gatow using the RAF’s fleet alone. If weinclude civilian Dakotas, we might get as many as 2,000 passengers out in aday, but don’t forget we will also reduce by one-third the tonnage of goodsthat our Dakotas have been delivering to Berlin so far.”

Herbert looked alarmed. “What would that meanin terms of supplies delivered?”

“Well, last month the RAF hauled 21% of thetonnage. The Dakotas were responsible for one-third of that — or 7% of overalltonnage. If they reduce their sorties by one-third, 2% less tonnage will bedelivered.”

“That sounds quite acceptable to me,” Herbertdeclared with a glance at Howley, who nodded in agreement. Noting Priestman’ssilence, Herbert asked him directly. “Don’t you agree, Wing Commander?”