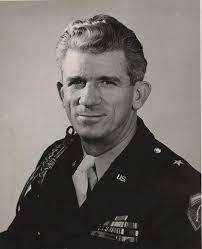

Historical Characters in "Cold War" - Frank Howley

The Bridge to Tomorrow Series includes several historical characters. One of these is the American Commandant in Berlin, Colonel Frank Howley. In the immediate post-war era, no Western figure was more consistently or more vehemently maligned and insulted by the Soviets than Howley -- and Howley was proud of it. He earned Soviet ire and the love of the Berliners -- 'though not always his superiors -- for his words and deeds as the American Commandant of Berlin 1945-1949. Without doubt he was one of the more colorful -- and controversial -- historical figures involved in the Berlin Airlift -- and I couldn't resist including him in the Bridge to Tomorrow Series as a character.

Nothing in Howley's background ordained him for the role he was to play in Berlin's history. Born in Hampton, New Jersey in 1903, Howley attended Parson's School of Fine and Applied Arts. He spent time time studying business and art at the Sorbonne in Paris before obtaining a BS in Economics from New York University. He then worked as an advertising executive, establishing his own firm in Philadelphia the 1930s, which proved highly successful despite the depression. Somewhere along the line he taught himself five languages, but not notably not German.

In the Second World War he initially commanded an Air Corps ground school, but he was not interested in flying and transferred to the cavalry. By 1943, he had been promoted to lieutenant colonel and was serving as the Executive Officer of the Third Mechanized Cavalry, but he was involved in a motorcycle accident in which he broke his back and pelvis. After five months in hospital, he was released but was not rated fit for active duty with a combat unit. Given the option of retiring or taking an assignment in the Civil Affairs division, which was responsible for re-establishing civil administration in occupied territory in the wake of anticipated Allied battlefield victories, Howley chose the latter. The task he had taken on was described cogently as "...to sweep into newly liberated territories and impose order on chaos, repairing shattered infrastructure and feeding starving civilians."

After training in the U.S. and the U.K. Howley landed in Normandy four days after D-Day as head of a mixed British-U.S. unit designated A1A1. Working with French liaison officers, Howley's team got the civil administration of Cherbourg working within days of its liberation. His success here lead to him being given responsibility for the same role after the liberation of Paris, and he entered the French capital on the heels of the fighting troops now in command of a unit of 350 officers and men. Here his success not only earned him the Legion of Merit, Croix de Guerre and the Legion d'Honneur, it also drew the attention of General Dwight D. Eisenhower's staff. Howley was asked to head the U.S. military government in Berlin, nominally as deputy to a figurehead who was a more senior combat officer.

Clearly, taking control of restoring civil infrastructure in Berlin would be different from his role in the liberated French cities since the population was presumed to be hostile and Berlin was to be shared with the other Allies, including the Soviets. Decisions were to be taking jointly and unanimously. Even before entering Berlin, Howley worked hard the establish rapport between the designated British and American teams, but dealing with the Soviets proved more difficult. From Day 1, the Soviets showed hostility to both the Americans and British troops sent to garrison their sectors of Berlin. Details can be read elsewhere, but by the end of his first day in Berlin, Howley knew who the enemy was -- and it wasn't the defeated, traumatized and starving population of Berlin. It was the Soviets.

From that point forward, Howley never deviated from his position that the Soviets were not to be trusted and could not be won over as friends, they were adversaries and had to be treated as such. The logical corollary of such a position was to start favoring and advocating on behalf of the Berliners under constant attack from the Soviets. Howley employed every tactic he could get away with to back the democratic elements in Berlin and to expose the machinations of the Soviet Military Administration and their puppet German Communists. He consistently reported to the press Soviet attempts to bribe and coerce voters. Wisely, he established a radio stations controlled by the U.S. military government, Radio in the American Sector or RIAS. In addition, independent newspapers were encouraged and allocated paper.

Meanwhile, the Kommandatura (where the city commandants of the four occupying powers regularly met) increasingly became a battlefield of words and exchanged insults. Howley recorded in his diary the suspicion that the Soviets were seeking to provoke a crisis. On June 16, at 11:15 pm after thirteen hours of haggling that was going no where, Howley turned his seat over to his deputy and excused himself. Describing his behavior and "hooligan," the Soviet's used his departure as an excuse to break up the Kommandatura and stormed out.

But the more the Soviets insisted in describing Howley as a "hooligan," "terrorist," "black market knight," "dictator," "cowboy," or "rough-rider from Texas," the more the Berliners loved him. He appeared the only one who shared their outrage over Soviet bullying. To be sure, Howley's style had not won him friends in Washington and his relationship with the cool and restrained General Clay were also often testy and strained. "Howlin' Mad Howley" was a epitaph applied as much by his Western colleagues as his Eastern adversaries. Yet whether one liked his style or not, he was the American who reassured the Berliners that the Americans weren't going home when the crisis came on June 24.

Such a colourful character could not be excluded from a novel about Berlin in this period! Below is an excerpt from "Cold War" in which he plays a role:

Priestman was startled to find Colonel Howley alreadywaiting in Herbert’s office. There had been a time when Herbert detestedHowley, and although they had been getting along better recently, it was still surprisingto find them together in apparent harmony. Nor did Priestman like the eagernesswith which they greeted him. Instinctively, he sensed a trap.

Herbert was a blunt man in the best ofcircumstances and got straight to the point. “Wing Commander, we asked you tomeet us today because, in view of the deteriorating situation, the Berlin CityGovernment has made a direct appeal to the Allied Kommandatura to assist in theevacuation of particularly vulnerable Berliners. What the city officials arethinking of is malnourished children, fragile, elderly people, and peoplesuffering from chronic illnesses such as asthma, arthritis, multiple sclerosis,and so on.”

“We’ve known for some time that Berlin’shospitals are in a deplorable state and understaffed,” Priestman reminded them.“You may remember that one of the civilian charter companies and our Sunderlandflying boats have been evacuating children on a small scale since earlyOctober.”

“Yes, yes,” Herbert brushed his remark asideand Priestman doubted if he had even been aware of the evacuations. Instead, heforged ahead exclaiming, “I’m sure you understand that we had no choice but toagree.”

He’d said “we” so Priestman glanced at Howley,who nodded vigorously and added, “This really must be done, Robin, and bothGeneral Herbert and I assured the mayor it would be done. What elsecould we say, for heaven’s sake? The Berliners are suffering enough as it is.How can we ask people with serious chronic illnesses, fragile old people, andkids to face a winter without heat, light or adequate rations? These aren’tsoldiers. They’re civilians.” Howley, as always, spoke forcefully.

Alarms started ringing in Priestman’s head. Hedistinctly remembered Tunner saying he would not get involved in flyingcivilians out of Berlin. Surely, the American and British Commandants had notmade promises to the Mayor of Berlin without first checking with the CombinedAirlift Task Force Commander? Out loud he asked cautiously, “Did the Mayor giveyou any indication of how many people are in these particularly vulnerablecategories that they now want to see evacuated?”

“Reuter suggested around 17,000.”

Priestman stiffened and asked at once, “HasTunner agreed?”

“No, blast him!” Herbert answered jumping tohis feet in exasperation and starting to pace with his hands behind his back.

Howley took over, explaining, “Tunner saystaking passengers on board his transport aircraft will slow down his entiresupply operation — ‘completely disrupt it’ is the way he worded it. He says17,000 people are a mere drop in the bucket and their departure will reducerequirements only marginally.”

Priestman had heard all that from Tunner himselfonly a month before, so it didn’t surprise him, even if he personally deploredTunner’s short-sightedness. For the others, Priestman pointed out, “Mathematicallyspeaking, he’s right. However, saving children’s lives is the right thing to do— from a humanitarian standpoint. Furthermore, if children, old people andpeople with chronic illnesses start dying in droves, the Soviets will be quickto accuse us of ‘mass murder.’ I doubt our political leaders would want eitherpeople to die or the Soviets to win a propaganda victory, so you’ll have to goover Tunner’s head. Have you spoken to Generals Clay and Robertson?”

“Yes,” Howley replied looking grim. “Roberstonpassed the buck, saying Americans control the Airlift since the creation of theCombined Air Lift Task Force, and Clay refused to ‘interfere.’ He said hewasn’t enough of an expert on military transport to feel he could overruleGeneral Tunner on an operational matter.”

That shook Priestman. He did not see this as astrictly ‘operational’ matter, and he had expected more understanding andcompassion from Clay.

Herbert returned to the table, sat down andfaced Priestman. “I’m pleased to hear you share my point of view on thisbecause I hope you can help us out.”

Priestman felt his pulse rate increase as hereminded the other two officers, “Tunner is my superior.”

“We know,” Howley assured him, “but hear usout. What Tunner said was that his freighters weren’t going to carry onesingle evacuee, but he added that he had no objection to the RAF taking thepassengers out.” Howley and Herbert were sitting on the edge of theirrespective seats as they awaited Priestman’s reaction.

“You’re asking me if the RAF can manage thison its own?”

“Can it?” Herbert pressed him.

“Have you asked Group Captain Bagshot?”

“No, I’m asking you, Wing Commander!” Herbert admonishedangrily. “I want your opinion as the professional who will have the mainresponsibility for implementation since all the passengers will have to departfrom Gatow. Could you evacuate 17,000 passengers on RAF aircraft and if so, howlong do you think it would take?”

Priestman did the maths out loud for them. “TheRAF aircraft most suitable for flying passengers out are the Dakotas and theSunderlands, but the latter are about to be taken off the Airlift because thefog clings to the water, reducing visibility even when Gatow is open, and wehave no radar control on the Havel. Furthermore, there is an increasing risk ofice. In short, only the Dakotas are available for an evacuation of this kind. Theycan carry between 24 and 28 passengers, but let’s be conservative and say 25passengers per flight. Weather permitting, we average a hundred Dakotadepartures each 24-hour period, but not all Dakotas can carry passengers and nightflights are extremely hazardous. So, let’s assume passengers are evacuated onjust seventy Dakota sorties per day. That would mean evacuating 1,750 peopleper day or all 17,000 of them in ten days — assuming good weather.”

“That’s jolly good!” Herbert exclaimed, evidentlysurprised, and Howley clapped Priestman on the back saying, “I knew we couldcount on you, Robin!”

“Slow down, please. Getting that many peopleout in one day, as I said, depends very much on the weather. Also, the evacueeswill have to be ready to board at a moment’s notice. They will have to be organisedin groups of 25 and can’t bring much luggage. I should say no more than onesuitcase per person weighing one and a half stone at the most. There can be noconfusion, pushing or shoving and fighting.” The other two officers nodded vigorouslyin understanding.

Priestman continued. “Nor do the problems endthere. Where are all the evacuees to go at the other end? We can’t just dumpthem on the Airlift airfields and tell them to look after themselves—”

“No, no! Of course, not!” Herbert agreed. “TheBerlin City government assured us they would organise onward transport tohospitals and homes. They said they were already doing this on a much smallerscale — is that what you mentioned earlier?”

“What we’ve done to date is evacuate roughly120 passengers per day using just one civilian company and the Sunderlandsflying into Hamburg. However, to remove 17,000 people we’ll need almost theentire RAF Dakota fleet, and it operates from a variety of different airfields.I would recommend that the evacuation flights end at the civil airport inHannover so that from there the aircraft and crews can return to their home baseto take on another load of inbound cargo for Berlin.”

“That sounds first-rate, Wing Commander!”Herbert’s relief added to his rare display of enthusiasm.

Howley nodded forcefully as well, adding,“Hannover has the added advantage of being centrally located, so the evacuees couldreadily be distributed across the West. I’m sure the City Council will agree.You’ll just need to coordinate this with them.”

“Bear in mind, furthermore, that even ifeverything goes like clockwork, embarking and disembarking passengers and theirluggage will delay return flights. That’s why Tunner wants nothing to do withit. Realistically, it means the Dakotas won’t be able to make three roundtripson a good day as they have been doing, but two. Which means I must revise myearlier calculations and say we’d need closer to fifteen days of good weatherto clear 17,000 passengers through Gatow using the RAF’s fleet alone. If weinclude civilian Dakotas, we might get as many as 2,000 passengers out in aday, but don’t forget we will also reduce by one-third the tonnage of goodsthat our Dakotas have been delivering to Berlin so far.”

Herbert looked alarmed. “What would that meanin terms of supplies delivered?”

“Well, last month the RAF hauled 21% of thetonnage. The Dakotas were responsible for one-third of that — or 7% of overalltonnage. If they reduce their sorties by one-third, 2% less tonnage will bedelivered.”

“That sounds quite acceptable to me,” Herbertdeclared with a glance at Howley, who nodded in agreement. Noting Priestman’ssilence, Herbert asked him directly. “Don’t you agree, Wing Commander?”

“I agree, but I hope you will forgive me fornoting that that’s 2% of overall capacity — whether the RAF or the USAF takesthe passengers. There is no logical reason why the burden of removingmalnourished children, feeble old people, and chronically ill patients fromBerlin should not be shared evenly. If both the RAF and the USAF carried theirshare, the entire operation could be concluded in less than half the time.”

“We already have Tunner’s answer!” Herbert snappedin annoyance, while Howley held up his hands in a gesture of surrender. “You’reright! I’m not going to argue with you, Robin. But the fact is that I can’ttell General Tunner what to do and General Clay isn’t willing to do so. Inother words, it’s the RAF or no one.”

Priestman had already grasped that fact andwas resigned to it. He nodded. “I need to talk to whoever on the City Councilis responsible for organising things at their end. I will prioritise this and tryto be ready to put it into effect in three or four days’ time — weatherpermitting.”

“Well done!” General Herbert exclaimed, “Ishould have known the RAF would come through!”

“If there’s nothing else, General, I’d betterget to work,” Priestman concluded.

Herbert got to his feet, thanking him. As hesaw Priestman to the door, he shook his hand more energetically and warmly thanever before. Howley took his leave of Herbert at the same time and the two men walkeddown the corridor and stairs together. At the exit, as they prepared to go totheir respective waiting cars, Priestman set his cap on his head with the peak partiallycovering his eyes and remarked in a low voice, “I presume you know this will bemy last act as Station Commander Gatow.”

“What do you mean?” Howley asked back inastonishment.

“You and Herbert avoided asking Group Captain Bagshotabout this because you knew he would say ‘no.’ Tunner’s indirect approval is a shabbyand transparent excuse that won’t hold up. Bagshot will rightly view me asinsubordinate, and he’ll have my skin. This may cost me more than my position,it might cost me my career.”

Howley took a second to absorb that and then asked,“But you’ll still do it?”

“I don’t see how we can maintain this Airliftfor more than a few weeks, which means Berlin will most probably be in Soviethands by Christmas. If I can save 17,000 civilians — the bulk of them children— from Stalin, then I will. It’s the moral equivalent of going down fighting.”

Howley is a character in all Three books of the "Bridge to Tomorrow" Trilogy

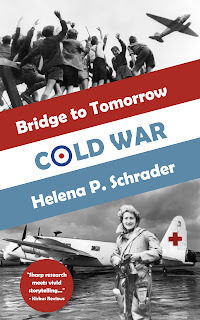

Berlin is under siege. More than twomillion civilians must be supplied by air -- or surrender to Stalin's oppression.

USAF Captain J.B. Baronowsky and RAF FlightLieutenant Kit Moran once risked their lives to drop high explosives on Berlin.They are about to deliver milk, flour and children’s shoes instead. Meanwhile,two women pilots are flying an air ambulance that carries malnourished andabandoned children to freedom in the West. Until General Winter deploys on theside of Russia. Buy now!

Based on historical events, award-winning and best-selling novelistHelena P. Schrader delivers an insightful, exciting and moving tale about howformer enemies became friends in the face of Russian aggression — and how closethe Berlin Airlift came to failing.

Winning a war with milk, coal and candy!