Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 8

March 26, 2024

Why I Write Historical Fiction - A Guest Blogpost by David Wessel

David K. Wessel is a retired U.S.diplomat and amateur historian turned novelist. When it comes to writing aboutGermany between the two world wars, he relies not only on his family stories,but on his Rutgers University history degree (where he focused on the WeimarRepublic) and a life-long interest in his subject matter. Wessel is one of sixchildren born to Karl-Heinz Wessel, the primary character in Choosing Sides– and the coming sequel, Changing Sides.

Ihave always loved the old adage: “Before you judge a man, walk a mile in hisshoes.” I believe that before ascribing motive to the actions of anotherperson, one should attempt to understand his/her/their life experiences. Beforecriticizing someone or assuming negative intent behind the words they speak, weshould try to appreciate where they are coming from. Before criticizing othersfor what we see or hear them do, we should make an effort to see things fromtheir perspective.

Whatare the challenges they have faced? How have their thought processes beenformed? What events have they been influenced by? How have they been shaped bythe world in which they live? What is their history?

Inthe words of the renowned scholar and Pulitzer Prize winning author DavidMcCullough, “History is who we are and why we are the way we are.” It is thekey to understanding the thoughts and deeds of an individual – and is especiallycritical to understanding the words and actions of societies.

Butthe recording of factual history – a description of past events with the datesand locations in which they occurred – does not get into the soul of theparticipants. Well written historical accounts of days-gone-by do explore thepreceding events that shaped the participant’s actions. And the best writers ofhistory, like McCullough, provide insight into the thinking and intent of theprotagonists. But their writing, as good as it is, does not leave the readerwith a true understanding of what it would have felt like to be in that time andplace.

Forthat, we need historical fiction. As E. L. Doctorow, author of BillyBathgate, Ragtime and other wonderful novels said: “The historianwill tell you what happened. The novelist will tell you what it felt like.”

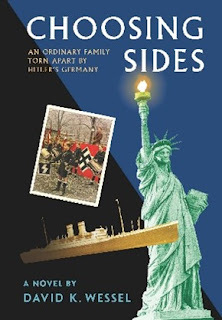

WhenI decided to write the story of my father’s childhood - growing up on bothsides of the Atlantic in the years between the two world wars - I wanted to dojust this. I hoped to portray what it must have felt like for Dad. In writingabout an ordinary family torn apart by Hitler’s Germany, my aim was to developthe reader’s understanding of what it meant to live in that time and place.

Howdid my family’s experiences in World War I and the post-war years lead to anemigration to the United States? Why did they move back to Germany just a yearafter Hitler had come to power? What was it like for Dad to be placed in theHitler Youth? How did the family’s meeting with der Fuhrer himself comeabout? How did my immediate family respond to the Nazi takeover of theircountry? And what did the extended family, who remained, feel about it all?

While writing the first draft of ChoosingSides I worked at getting the story down and making sure I had the factsright. I focused on placing the family lore into historical context, buildingmy own understanding of the circumstances behind the family’s multiple movesfrom northern Germany to southern New Jersey. The result was, in the estimationof my dear wife and ‘first-reader,’ a 90,000 word term paper with a personaltwist. It was, at best, something a few of my family members might read. But itwas dry and lacking in emotion and devoid of any character development,description of settings, dialogue or buildup of personal feelings and tensionbetween family members. If I wanted anyone else to read it, I needed to livenit up.

I needed to change it from abiographical history to historical fiction. In doing so, I wanted to use thepower of fiction to draw the reader into the souls of my characters – my father,his parents, his aunts and uncles and cousins, his schoolmates and friends. Ihoped that I would enable the reader to understand the difficult choices myfamily members made as Hitler ascended in power and their country descendedinto chaos and despair.

How well I have achieved my goal is,of course, a matter for readers to decide. But I must say that the exercise ofgetting the family stories down on paper and placing them in the context ofthis terrible period of history has certainly given me, as the author, a levelof understanding that is much deeper than I had before I started. I hope itwill do the same for my readers.

Blog Host Helena P. Schrader is the author of 25 historical fiction and non-fiction books, eleven of which have one one or more awards. You can find out more about her, her books and her awards at: https://helenapschrader.com

Her most recent release, Cold Peace, was runner-up for the Historical Fiction Company BOOK OF THE YEAR 2023 Award, as well as winning awards from Maincrest Media and Readers' Favorites. Find out more at: https://www.helenapschrader.com/cold-peace.html

March 19, 2024

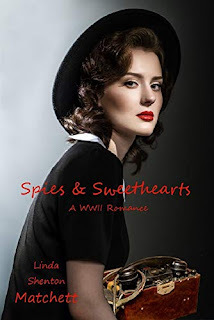

Why I Write Historical Fiction - A Guest Blogpost by Linda Matchett

Linda Shenton Matchett writes happily-ever-afterhistorical Christian fiction about second chances and women who overcome life’schallenges to be better versions of themselves. Follow the journeys ofrelatable characters whose faith is sorely tested, yet in the end, emerge triumphant.Be encouraged in your own faith-walk through stories of history and hope. Anative of Baltimore, Maryland, Linda was born a stone’s throw from Fort McHenry(of Star-Spangled Banner fame) and has lived in historical places all her life.She now lives in central New Hampshire where she is a volunteer docent andarchivist at the Wright Museum of WWII.

This opportunity toshare about why I write historical fiction has come an interesting time becauseI recently spent three months with a branding consultant. Her first fewquestions were about this very topic. Why did I write? Why did I write fiction?And…why did I write historical fiction?

When I was in thirdgrade, my parents gifted me a notebook, and I’ve been scribbling stories eversince. Thanks to my dad’s job, we moved often, mostly to areas steeped inhistory. Writing was my one constant. However, after entering the workforce, myfiction writing dropped away as I focused on business writing for my job. Aftermoving to New Hampshire, I freelanced for travel and live style magazines, andas much as I enjoyed that, fiction was always my first love.

But what to write about? I startedlots of stories, but struggled to finish. All historical, they covered avariety of eras, but none of the plotlines resonated with me.

Then one afternoon at the WrightMuseum of WWII changed my life...

The carpet muffled my footsteps as Iwandered into the home front gallery during my volunteer docent shift. Isauntered past the dioramas: a five-and-dime, a kitchen, then a living room,chatting with visitors and answering questions. As I approached the exhibitabout war correspondents, my eye was drawn to the small photo at the bottom: awoman wearing a combat helmet and a cheeky grin as she cradled her camera,finger poised over the button. Riveted, I stopped.

Who was she, this lone women in adisplay of men? I scanned the placard: Therésé Bonney, photojournalist.Minimal information so I yanked out my smart phone and keyed in her name. Factsand figures emerged, but one struck me more than the others: Of the more thantwo thousand accredited war correspondents, only 127 were women, including Ms.Bonney. Intrigued, I continued to dig. My pulse raced as I read.

By all accounts, she and the otherfemale correspondents had it tough, often relegated to fluff pieces and deniedaccess to combat zones. They fought for the right to tell stories…realstories…the same sort of stories the men had access to. By hook and by crook,these stalwart women made their way across Europe and other countries, shiningthe light on war’s atrocities.

There had to me more women like them.Women who went outside their comfort zone to do jobs never before held by womenin places they’d never dared go: pilots, welders, mechanics, doctors, farmers,truck and ambulance drivers, parachute riggers, radio operators, laboratorytechnicians, and even spies. Then there were the women who served in everybranch of the armed forces. Some of the women remained on the U.S. home frontwhile others crossed the globe to places most people had never heard of.

Inspired by the tenacity anddoggedness of these often-overlooked women to follow a story wherever it led, Iknew I needed to shine the light on their stories, their lives, andthose of other ordinary women who did extraordinary things – things I couldnever do in my wildest dreams.

Spies & Sweethearts

Shewants to do her part. He’s just trying to stay out of the stockade. Will twoagents deep behind enemy lines find capture… or love?

1942.Emily Strealer is tired of being told what she can’t do. Wanting to proveherself to her older sisters and do her part for the war effort, the highschool French teacher joins the OSS and trains to become a covert operative. Afterher training, she finds herself parachuting into occupied France with herinstructor to send radio signals to the Resistance.

MajorGerard Lucas has always been a rogue. Transferring to the so-called “Office ofDirty Tricks” to escape a court-martial, he poses as a husband to one of histrainees on a dangerous secret mission. But when their cover is blown afteronly three weeks, he has to flee with the young schoolteacher to avoid Naziarrest.

Runningfor their lives, Emily clings to her mentor’s military experience during theharrowing three-hundred-mile trek to neutral Switzerland. And while Gerardcan’t bear the thought of his partner falling into German hands, their forgedpapers might not be enough to get them over the border.

Website/Blog:http://www.LindaShentonMatchett.com

Blog Host Helena P. Schrader is the author of 25 historical fiction and non-fiction books, eleven of which have one one or more awards. You can find out more about her, her books and her awards at: https://helenapschrader.com

Her most recent release, Cold Peace, was runner-up for the Historical Fiction Company BOOK OF THE YEAR 2023 Award, as well as winning awards from Maincrest Media and Readers' Favorites. Find out more at: https://www.helenapschrader.com/cold-peace.html

March 12, 2024

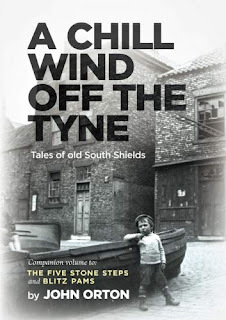

Why I Write Historical Fiction - Guest Blogpost from John Orton

John Orton took up writingfollowing his retirement and found a niche for himself in writing about his home-town of South Shields. His Tales ofOld South Shields tell the unofficial history of the town and itscharacters. The first three, set in the earlydecades of the 20th Century, are based on the memoirs of SergeantThomas “Jock” Gordon, of the Shields Police. In his latest book, He Wears a BlueBonnet, John went back in time to the 17th century with aripping yarn set in the salt pans of Auld Sheels.

Young Johnlad used to listen entrancedas his Nan, Gertie, sitting in her usual chair in the kitchen, a cup of tea athand, told stories of her time as a girl in Sheels in the early 1900s:about her Da’, a sailor, John Blot, so called because he could soak it up, whowent on to become a North Sea Pilot; about the monkey who jumped on her headfrom a sailors’ lodging house when she was taking her Da’s dinner to him in apudding basin when he was in dock; about wrecks on the Black Middens and thedangers of crossing the bar; about the time they burned Kruger in the streetsof Shields when Mafeking was relieved; of Dick Burke, the bookie, who wouldescape the polis by going up the backstairs of a house, (you’d hear him comingas his wooden leg knocked on the steps), through the kitchen, ‘G’dafternoon’..’ G’d afternoon Dick’, down the front stairs and away; of the LambtonWorm, with its ‘Geet big teeth, geet big mooth and geet big gogglyeyes.’ The wireless would go on at six o’clock sharp for the latest horseracing results, and Johnlad could remember when she won £13 12s 8d on athre’penny accumulator. He and his brothers got new shoes.

Johnlad never forgot her stories. Heloved comics like the Hotspur, and read books all the time. Againstexpectations he turned out clever, went to Oxford and became a lawyer, reachingthe top of his chosen field in local government as a County Solicitor. But hehad not only taken a love of stories from his Nan, who had neurasthenia as ayoung woman and always suffered with her nerves. Johnlad inherited the gene, hada serious nervous breakdown in his mid-forties and retired from workpermanently. He suffered many years with depression trying to find something worthwhilethat would give him enjoyment and fill his days.

More than forty years after hearinghis Nan’s stories of Old Shields he discovered the memoirs of Station SergeantTom ‘Jock’ Gordon who’d joined the Shields Police from Scotland at the end ofthe First World War. The manuscript, hand written, dog eared and whiskystained, brought vividly to life the characters, good and bad, of a busy coalmining, ship building, industrial port in the 1920s and 1930s where folk tookthe rough with the smooth and got on with it.

Jockhad more tales than Jonlad’s Nan: of one-legged Hughie Ross who’d knocked off anInspector’s helmet with his crutch; of the publicans who left a small pot ofwhisky tied to the back gate of their pub for the Bobby on night shift; of themounted officer whose horse would stop at every pub on the regular route backto the nick, much to the frustration of new riders; of the true story behindthe 1926 race-riots when the Yemeni seamen fought with British sailors for thefew jobs that were going on the ships; of the day the polis raided the pitchand toss gambling dens on Trow rocks. Johnlad also rediscovered Dick Burke,one of many street bookies - Jock Gordon had been in on the raid on Dick’shouse when the Polis confiscated over £800 placed in bets on St Leger Day.

Johlad thought that others should knowabout the old days and decided to write up Jock’s memoirs, together with hisown Nan’s stories. But the tales were short so Johnlad filled in the gaps, and hadto learn for himself how life was lived in those days. So, as well as writing thestories down, Johnlad spent as much time in historical research, to make surehe got things right.

After Johnlad’s books were publishedhe’d hear from Shields folk who’d loved the stories and whose own families had similartales. A woman of Yemeni descent contacted John to tell him that she had wipedaway tears after reading the story of Geordie Hussain in Johnlad’s book, AChill Wind off the Tyne. The same things that happened to him in the 1920swere happening again to people now, she said. Geordie was a foundling, and had been ‘adopted’ by an Arab lodging housekeeper. He had been caught up in the 1926 race riots and was under threat ofdeportation to the Yemen if convicted. He was married to a Shields lass, hadthree children, and had never been to the Yemen in his life –but he had nopapers to prove he was born in Shields. (No spoiler as to how it ends.)

Well, Johnlad thought to himself, ‘Ifmy stories of the past can move someone to tears, then that is why I writehistorical fiction’.

A Chill Wind off the Tyne, byJohn Orton, UKBook Publishing; illustrated edition (9 Aug. 2018) is available onAmazon (paperback and Kindle).

Blog Host Helena P. Schrader is the author of 25 historical fiction and non-fiction books, eleven of which have one one or more awards. You can find out more about her, her books and her awards at: https://helenapschrader.com

Her most recent release, Cold Peace, was runner-up for the Historical Fiction Company BOOK OF THE YEAR 2023 Award, as well as winning awards from Maincrest Media and Readers' Favorites. Find out more at: https://www.helenapschrader.com/cold-peace.html

March 5, 2024

Why I Write Historical Fiction - A Guest Blogpost from Tessa Floreano

Tessa Floreano is an author and community historian who lives near Seattle, but considers Vancouver and Venice her second homes. She writes historical tales about Italians, with a gallon of mystery and a pint of romance thrown in for good measure. Her stories are set mainly in the Pacific Northwest and Europe, though a few are in New York City and San Francisco, just because she has a strong pull to the Italians in both those cities, too. Coming Winter 2024 is a romantic mystery set in 1899 in Italy at Christmas involving murder, matrimony, and mayhem, oh my!

Inpalmistry, a square atop Jupiter's mount signifies a teacher's box. Unlike myhusband, no such pronounced formation exists on my palm. If it did, I imagineit might provide the impetus to teach historical fiction—a genre towhich I am intensely and increasingly drawn. Rather than a classroom as myteaching box, I use the power of the pen to scribe stories, both real andimagined. Some kind readers have even insisted that I am teaching, though perhaps in a lessstructured way. Hopefully, more entertaining, too. And why do I prefer to writewords about history rather than speak them? Read on, fair reader.

Asan impressionable youngster, I devoured historical fiction. Betwixt the pagesof fairy tales and fantastic yarns of yore, my imagination soared unobstructed.I had never visited a Saxon fortress, worn a Roman toga, or witnessed a Saharansandstorm, reading about medieval knights, ancient senators, or whirlingdervishes in faraway places allowed me to dream and put myself in someoneelse's shoes; or rather, smack in the middle of their adventures andmisadventures.

Growing up, I didnot come across stories about girls like me whose parents were immigrants,spoke with a funny accent, and whose customs and traditions did not fit themainstream. Thus, I escaped into what was available, like The Borrowers, Anneof Green Gables, Little House on the Prairie, and Nancy Drew. Eventually, thesenear-contemporary stories fell short. To ease the ache for something moreenticing, I glommed onto the classics set in foreign lands, like The Count ofMonte Cristo, Anna Karenina, and The Hound of the Baskervilles.

As I got older,and soon after my father died, I delved headlong into our family's past. Therewere many questions I did not get to ask my father, so I dug into our familytree and that is when the stories started to pop. Though my genealogy isincomplete, I turned to stories about other Italians. Some reflected my ownnorthern Italian heritage that surrounded me in my Canadian hometown ofVancouver. Some were based on southern Italian ancestry, by far the largestgroup I encountered when I emigrated to the Seattle area.

Fastforward to today where I write through a lens colored by a variety of Italianhistory, herstory, and heritage—some fictionalized, some not. Through thesetales, I share what I know, love, and am curious about. Always, they include animaginative reconstruction of historical events and Italian personages that Ifind fascinating and yearn to learn more about. My curiosity drives my researchand storytelling. Both mundane and obscure items can start me off. I satiate mycuriosity when I fall deeper down the rabbit hole after finding a gem or twothat I know I can develop further.

Toeducate myself and ensure I am getting as accurate a picture as I can ofpeople, places, events, and the vernacular of the time, I draw on primary andsecondary sources to give depth and nuance. Primary sources include documentsand artifacts—personal letters, oral interviews, diaries, carte de visites,calling cards, photographs, newspapers, advertisements, maps, and governmentdocuments. Secondary sources include scholarly articles, illuminatedmanuscripts, black and white movies, and old books with wonderful and strangebon mots in the margins. I seek out that which supports my story, thoughoccasionally the words and objects I find completely change the trajectory Ihad planned, be it for the plot, characters, or theme.

Throughoutmy story, I weave one or more themes—love, hate, betrayal, loyalty, bravery,cowardice, survival, power, secrets—making sure my protagonists and antagonistsdrive the problems and solutions. My characters are not automatons, and theyexperience things in different ways and filter them through their own ideas,prejudices, understandings, and misunderstandings, specific to their time. WhenI begin to tell my tale, I make a choice about what historical words to use,what to emphasize, what to leave out, and so on. I might imagine a situationwhere one of my newly arrived Italian immigrants witnesses a brawl. AnEnglish-speaking American who understands what everyone is saying—from thevictim to the first responders to the perpetrator—might offer a vastlydifferent view than a foreigner who does not understand the language or thelaw. Therefore, I have to factor that in to how the scene unfolds and thecharacters behave, and that is where the opportunities and challenges lie.

Ienjoy juxtaposing political, social, cultural, and religious views and biasesof yesterday without imposing those of today onto my characters. If I do my jobwell, I can use my stories to not only show readers what happened in the past,but how it has shaped the present. And I have to do it intentionally. Forexample, I have a great idea for a dual timeline story. You can bet that mycharacters will—at some point—say that they must not change the annals whenjumping chronology, regardless of how tempting, especially if there's dangerafoot. I have to respect that because historical fiction has some rules, mostof which I adhere to (wink wink).

Iam careful when I bring in historical events and how I manage them. Here is anexample: Let's say that in my interwar series, Roosevelt announcesthe New Deal with great fanfare. Rather than having a character read about itin a newspaper, I can use a conversation between characters to help my readersunderstand the implications for Italians of the programs and public worksprojects that took place in that era. I could show how the first ItalianRepublican congresswoman in her state, who did not want the New Deal, reacts toit. Conversely, I might show how a Dust Bowl farmer benefited eventually fromthe President’s reforms and the life changes he and his Italian familyexperience because of the impact on their finances.

Actually,I would not be able to use the first example because the first Italian Americanwoman to serve in Congress did not happen until 1970, many decades after theDepression, which is the time period of my series. You might have thought Idigressed there for a moment, but double-checking my facts is a big part of whyI love writing about history.

Sometimes,a fact just will not work within the timeline I chose, and I either have toleave it out, or include a mention of my fabricated use of it in my Author'sNote, and why it is plausible. Critics, ahem, sticklers for one hundred percentfactual historical detail, will bemoan that I use the Author's Note as acrutch. They will argue that it is how I justify why I wrote certain events outof context or included details about real personages that were not real. Theymight even write off my story because of it.

Ido not argue with people who feel that way, however, I reserve the right to usesuch a device to inform, and yes, even teach my readers. It is a space I holdsacrosanct. It is where I exhale and reveal my raw side, including my sources,inspiration, methods, and hope for the book's place in the world. I usethe Author's Note like an informal letter to my readers—to give deepermeaning to my story, some accountability, and a more objective understanding ofthe history. If I change facts to suit the story's timeline, I owe it to myreaders to be transparent about why, and I believe they will respect me for it.

Mostreaders love that intimate connection that my Author's Note provides becausethey know I spent the time speaking directly to them. Usually, I include extrainformation that adds a new dimension to the story they just read and I amtickled when they embrace it. Some readers have shared that it leads them downtheir own rabbit holes of history, and that makes the effort of writing aboutwhat I am learning all the more satisfying.

Towrite is to learn, and this is true for me, especially as it relates tohistorical fiction. It has staying power in my writing (and teaching) life,even if I am short of one geometric square imprinted on my skin.

Find out more about Tessa’s books on her website https://tessafloreano.com and by signing up for her newsletter

Find out more about Tessa’s books on her website https://tessafloreano.com and by signing up for her newsletter

Blog Host Helena P. Schrader is the author of 25 historical fiction and non-fiction books, eleven of which have one one or more awards. You can find out more about her, her books and her awards at: https://helenapschrader.com

Her most recent release, Cold Peace, was runner-up for the Historical Fiction Company BOOK OF THE YEAR 2023 Award, as well as winning awards from Maincrest Media and Readers' Favorites. Find out more at: https://www.helenapschrader.com/cold-peace.html

Why I Write Historical Fiction - A Guest Blogpost from Teresa Goertz

Tessa Floreano is an author and community historian who lives near Seattle, but considers Vancouver and Venice her second homes. She writes historical tales about Italians, with a gallon of mystery and a pint of romance thrown in for good measure. Her stories are set mainly in the Pacific Northwest and Europe, though a few are in New York City and San Francisco, just because she has a strong pull to the Italians in both those cities, too. Coming Winter 2024 is a romantic mystery set in 1899 in Italy at Christmas involving murder, matrimony, and mayhem, oh my!

Inpalmistry, a square atop Jupiter's mount signifies a teacher's box. Unlike myhusband, no such pronounced formation exists on my palm. If it did, I imagineit might provide the impetus to teach historical fiction—a genre towhich I am intensely and increasingly drawn. Rather than a classroom as myteaching box, I use the power of the pen to scribe stories, both real andimagined. Some kind readers have even insisted that I am teaching, though perhaps in a lessstructured way. Hopefully, more entertaining, too. And why do I prefer to writewords about history rather than speak them? Read on, fair reader.

Asan impressionable youngster, I devoured historical fiction. Betwixt the pagesof fairy tales and fantastic yarns of yore, my imagination soared unobstructed.I had never visited a Saxon fortress, worn a Roman toga, or witnessed a Saharansandstorm, reading about medieval knights, ancient senators, or whirlingdervishes in faraway places allowed me to dream and put myself in someoneelse's shoes; or rather, smack in the middle of their adventures andmisadventures.

Growing up, I didnot come across stories about girls like me whose parents were immigrants,spoke with a funny accent, and whose customs and traditions did not fit themainstream. Thus, I escaped into what was available, like The Borrowers, Anneof Green Gables, Little House on the Prairie, and Nancy Drew. Eventually, thesenear-contemporary stories fell short. To ease the ache for something moreenticing, I glommed onto the classics set in foreign lands, like The Count ofMonte Cristo, Anna Karenina, and The Hound of the Baskervilles.

As I got older,and soon after my father died, I delved headlong into our family's past. Therewere many questions I did not get to ask my father, so I dug into our familytree and that is when the stories started to pop. Though my genealogy isincomplete, I turned to stories about other Italians. Some reflected my ownnorthern Italian heritage that surrounded me in my Canadian hometown ofVancouver. Some were based on southern Italian ancestry, by far the largestgroup I encountered when I emigrated to the Seattle area.

Fastforward to today where I write through a lens colored by a variety of Italianhistory, herstory, and heritage—some fictionalized, some not. Through thesetales, I share what I know, love, and am curious about. Always, they include animaginative reconstruction of historical events and Italian personages that Ifind fascinating and yearn to learn more about. My curiosity drives my researchand storytelling. Both mundane and obscure items can start me off. I satiate mycuriosity when I fall deeper down the rabbit hole after finding a gem or twothat I know I can develop further.

Toeducate myself and ensure I am getting as accurate a picture as I can ofpeople, places, events, and the vernacular of the time, I draw on primary andsecondary sources to give depth and nuance. Primary sources include documentsand artifacts—personal letters, oral interviews, diaries, carte de visites,calling cards, photographs, newspapers, advertisements, maps, and governmentdocuments. Secondary sources include scholarly articles, illuminatedmanuscripts, black and white movies, and old books with wonderful and strangebon mots in the margins. I seek out that which supports my story, thoughoccasionally the words and objects I find completely change the trajectory Ihad planned, be it for the plot, characters, or theme.

Throughoutmy story, I weave one or more themes—love, hate, betrayal, loyalty, bravery,cowardice, survival, power, secrets—making sure my protagonists and antagonistsdrive the problems and solutions. My characters are not automatons, and theyexperience things in different ways and filter them through their own ideas,prejudices, understandings, and misunderstandings, specific to their time. WhenI begin to tell my tale, I make a choice about what historical words to use,what to emphasize, what to leave out, and so on. I might imagine a situationwhere one of my newly arrived Italian immigrants witnesses a brawl. AnEnglish-speaking American who understands what everyone is saying—from thevictim to the first responders to the perpetrator—might offer a vastlydifferent view than a foreigner who does not understand the language or thelaw. Therefore, I have to factor that in to how the scene unfolds and thecharacters behave, and that is where the opportunities and challenges lie.

Ienjoy juxtaposing political, social, cultural, and religious views and biasesof yesterday without imposing those of today onto my characters. If I do my jobwell, I can use my stories to not only show readers what happened in the past,but how it has shaped the present. And I have to do it intentionally. Forexample, I have a great idea for a dual timeline story. You can bet that mycharacters will—at some point—say that they must not change the annals whenjumping chronology, regardless of how tempting, especially if there's dangerafoot. I have to respect that because historical fiction has some rules, mostof which I adhere to (wink wink).

Iam careful when I bring in historical events and how I manage them. Here is anexample: Let's say that in my interwar series, Roosevelt announcesthe New Deal with great fanfare. Rather than having a character read about itin a newspaper, I can use a conversation between characters to help my readersunderstand the implications for Italians of the programs and public worksprojects that took place in that era. I could show how the first ItalianRepublican congresswoman in her state, who did not want the New Deal, reacts toit. Conversely, I might show how a Dust Bowl farmer benefited eventually fromthe President’s reforms and the life changes he and his Italian familyexperience because of the impact on their finances.

Actually,I would not be able to use the first example because the first Italian Americanwoman to serve in Congress did not happen until 1970, many decades after theDepression, which is the time period of my series. You might have thought Idigressed there for a moment, but double-checking my facts is a big part of whyI love writing about history.

Sometimes,a fact just will not work within the timeline I chose, and I either have toleave it out, or include a mention of my fabricated use of it in my Author'sNote, and why it is plausible. Critics, ahem, sticklers for one hundred percentfactual historical detail, will bemoan that I use the Author's Note as acrutch. They will argue that it is how I justify why I wrote certain events outof context or included details about real personages that were not real. Theymight even write off my story because of it.

Ido not argue with people who feel that way, however, I reserve the right to usesuch a device to inform, and yes, even teach my readers. It is a space I holdsacrosanct. It is where I exhale and reveal my raw side, including my sources,inspiration, methods, and hope for the book's place in the world. I usethe Author's Note like an informal letter to my readers—to give deepermeaning to my story, some accountability, and a more objective understanding ofthe history. If I change facts to suit the story's timeline, I owe it to myreaders to be transparent about why, and I believe they will respect me for it.

Mostreaders love that intimate connection that my Author's Note provides becausethey know I spent the time speaking directly to them. Usually, I include extrainformation that adds a new dimension to the story they just read and I amtickled when they embrace it. Some readers have shared that it leads them downtheir own rabbit holes of history, and that makes the effort of writing aboutwhat I am learning all the more satisfying.

Towrite is to learn, and this is true for me, especially as it relates tohistorical fiction. It has staying power in my writing (and teaching) life,even if I am short of one geometric square imprinted on my skin.

Find out more about Tessa’s books on her website https://tessafloreano.com and by signing up for her newsletter

Find out more about Tessa’s books on her website https://tessafloreano.com and by signing up for her newsletter

Blog Host Helena P. Schrader is the author of 25 historical fiction and non-fiction books, eleven of which have one one or more awards. You can find out more about her, her books and her awards at: https://helenapschrader.com

Her most recent release, Cold Peace, was runner-up for the Historical Fiction Company BOOK OF THE YEAR 2023 Award, as well as winning awards from Maincrest Media and Readers' Favorites. Find out more at: https://www.helenapschrader.com/cold-peace.html

February 27, 2024

Why I Write Historical Fiction - A Guest Blogpost from G. M. Baker

G. M. Baker is trying to revive the serious popular novel, the kind of story that finds the truth of the human condition in action, adventure, romance, and even magic. He is the author of the historical novel series Cuthbert's People (The Wistful and the Good, St. Agnes and the Selkie, The Needle of Avocation) and the literary fairy-tale Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight. He writes the newsletter, Stories All the Way Down, which examines serious popular fiction in theory and practice.

My reasonsfor writing historical fiction may be somewhat eccentric these days. I don’t doit to deep dive into the personality of an historical figure or to delve intothe details of life in a particular era. Rather, I turn to the past to find theperfect stage on which to set the story I want to tell. The modern world isdesigned to remove as much drama from our lives as possible. That’s a goodthing as far as daily living is concerned. I don’t want to live my lifeconstantly trying to dodge starvation, war, and shipwreck. But when it comes towriting stories, this lack of daily drama is limiting. In particular, it tendsto force the writer of contemporary fiction to find drama in the darker partsof the psyche and in the lost and the broken of society. There’s nothing wrongwith that, but as an exclusive diet, it gets wearisome.

In thepast, however, you did not need to suffer from alienation or mental disorder tohave drama in your life. Even the rich and the healthy faced threats of manykinds and, by and large, had to face them alone or with the help of theirfriends. We may not live those kinds of lives anymore, but we still love thosekinds of stories. Or I do, anyway.

Forinstance, in my latest published novel, The Needle of Avocation, myprotagonist, Hilda, goes to fulfill a promise of marriage to a man above herstation. Her ambitious mother wrung the promise out of the groom’s father at atime of sorrow, anger, and drunkenness. No one except Hilda’s mother wants themarriage to take place, not even Hilda herself. And yet, the consequences ofrefusing the marriage could be dire for her kin. This is not a situation thatcould possibly arise in the contemporary West. So I set it in 8thcentury Northumbria. This was a story I wanted to tell, and the past provided astage on which to tell it.

I have twodegrees in history, but in history it has always been the deep ground ofcivilizations and societies that has fascinated me rather than individual livesand events. I am interested in understanding how all of the constraints ofparticular times and places shape the lives and mores of the people who live inthem. We can be very glib today in either blaming or patronizing people of thepast for not thinking the way we do. But I don’t believe human beings getbetter or worse. I think we are shaped by our circumstances, and what ishorrific in one circumstance may be normal and necessary in another. Forinstance, in my 8th-century Northumbria stories, my characters keepslaves, which is, to them, a perfectly normal thing. Everyone in that society isbound together by chains of obligation that are essential for maintaining lifeand defense. Degrees of liberty can be won by service, but only degrees. Theslaves are simply those who have none of these privileges.

It is mygoal to fully enculturate my characters in their milieu so that things likeslaveholding do not seem exceptional or objectionable to the reader within theworld of the novel. One of the things that most pleases me about my Anglo-Saxonseries is that no reader or reviewer has ever brought up the issue of slaverywhen reviewing or discussing them.

Fullyenculturating characters in this way is also part of finding the right stagefor the story. If Hilda in The Needle of Avocation reacted to herdilemma the way that a woman of her age would today, it would be a verydifferent and less authentic story. Hilda takes her obligations to her familyentirely seriously. Her difficulties come with how to fit herself into a familythat does not want her. It is, as far as I can make it, a story of a woman ofthe 8th century, not the story of a woman of today dropped into the8th century.

But for mycurrent work in progress, I have jumped forward 1000 years and to the other endof Britain to tell the story of a wrecker’s daughter in Cornwall during theNapoleonic era. Hannah follows her father in the trade, wrecking ships, killingcrews, and stealing their cargos. But as she sees more of the wider world, herconscience begins to trouble her, setting up a deep conflict of loyalties.Again, the time and place are chosen as the right stage to tell this story, andonce again I have tried to thoroughly enculturate Hannah in what is,admittedly, a circumstance that stands on the border between history and myth.

In otherworks, such as Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight, I have gone entirely intomyth in search of the perfect stage for the story I wanted to tell. But for themost part, I find our vast and varied past provides the perfect stage forsetting almost any story you might want to tell. The trick then is to thoroughlyenculturate your characters in the time and place you have chosen, for theplayer must own the stage, or the play will be a dud.

Mark's website is https://gmbaker.net

Blog Host Helena P. Schrader is the author of 25 historical fiction and non-fiction books, eleven of which have one one or more awards. You can find out more about her, her books and her awards at: https://helenapschrader.com

Her most recent release, Cold Peace, was runner-up for the Historical Fiction Company BOOK OF THE YEAR 2023 Award, as well as winning awards from Maincrest Media and Readers' Favorites. Find out more at: https://www.helenapschrader.com/cold-peace.html

February 20, 2024

Why I Write Historical Fiction - A Guest Blogpost from Jackson Marsh/James Collins

Today it is my pleasure introduce "Jackson Marsh" and hear his reasons for writing historical fiction. Jackson Marsh is the pen name of author and screenplay writer James Collins, who published 11 books before turning to what he had been hankering to write, historical mysteries and MM romance novels. Originally from Romney Marsh, England, Jackson now lives on a Greek island with his husband of 26 years.

I write historical fiction from the perspective of gay men.To be precise, I write about British gay men living in the Victorian era. Atthis time, being gay (as we call it now) was punishable by up to two years inprison with hard labour, and thanks to the Labouchere Amendment of the Criminal Law AmendmentAct 1885, it was extremely easy for men to be suspected of and arrested for ‘grossindecency.’ What’s more, sexual acts no longer had to be proven. This is thelaw that was used most famously against Oscar Wilde, but many men from all classesfell foul of it.

At the same time, Victorian London (and other less written about cities)suffered from what I call an outbreak of immorality. This, I believe, was areaction to the more widespread outbreak of morality.

Pressure of Being Gay in Victorian Times

With the idea in mind of ‘What was it like to be illegal from birth?’ I setabout writing a series of novels set in the late 19th century, where all themain characters bar one are gay men. Throughout the series, these men areillegal by their very nature, and I was interested to explore the pressurebeing gay would have put on them. Waking up every day knowing that you loveother men and can do nothing about it, having to be careful who you meet andspeak to, not being able to express yourself and knowing you might, at anytime, be arrested… These are still issues in many countries around the worldtoday. So, I thought, my theme is still very relevant.

The Clearwater Mysteries

What I do with the series is, in effect, put modern-day issues into a historicalsetting, and that is the overarching theme. The stories are individualmysteries set within this world and its expectation of morality, and thecharacters react to this outside pressure through male bonding, bromance, and romance,all of which no doubt went on and thrived at the time yet had to happen with agreat deal of caution.

Thus, the series is blanketed by the pressure of illegality.However, it goes further than that because the two main characters are fromdifferent social classes. One is a viscount newly elevated to his title ofViscount Clearwater, and the other — Silas, the man who becomes the love of theviscount’s life — is what we’d now call a rent boy, a homeless young man livingrough on the streets of the East End of London. With him is his best friend, aUkrainian refugee and a fellow part-time renter. Viscount Clearwater wants tohelp such young men by providing a mission, and thus, he and Silas meet.

Setting Fiction Against History

There’s another layer to the series-starter novel, ‘Deviant Desire.’ The mysteryand action plot take the premise: ‘What if Jack the Ripper killed men?’ Inother words, the East End Ripper of 1888 is attacking rent boys, instantlyputting Silas in another danger.

Having written ‘Deviant Desire’ I realised that not only didI have a good band of five principal male characters (all gay apart from theUkrainian refugee) and a couple of hideous villains/antagonists, but I also hadthe opportunity to explore other true-life events and crimes, and use them asthe inspiration for an ongoing series of mysteries. This is why, as The Clearwater Mysteriesprogresses, we meet characters such as Bram Stoker and Henry Irving, and wespend time in the British Museum Reading Rooms and the Royal Opera House.Throughout the background of these fictionalised stories are facts and truismsfrom history, and as much as I can, I have the characters living the zeitgeistof the time. That in itself if something of a challenge for many authors of historicalfiction, particularly those who are not historians.

I have great fun exploring old dictionaries and modern onesto see if a word I want to use was in existence at the time in which I am writing.If ever I read, or hear on a film or TV show, characters pre-1940 saying theword ‘Okay’, I switch off. If I’m not sure about a word, I check it out, andfind an alternative. For example, none of my characters can use the word‘acerbic’ because it didn't come into usage until the start of the 20thcentury.

So, Why Do I Write Historical Fiction?

I write historical fiction based on facts because a) I enjoywriting stories, b) I enjoy researching and learning as I go, and c) I wantedto highlight the plight of 19th century gay men. To do this, I created a protagonistwho is in a position to help other gay men, and Lord Clearwater does so throughoutthis 11-book series and the ones that follow.

The ClearwaterMysteries begins at the time of the East End Ripper in 1888 with theopening novel, ‘Deviant Desire.’

Website: www.jacksonmarsh.com

Blog Host Helena P. Schrader is the author of 25 historical fiction and non-fiction books, eleven of which have one one or more awards. You can find out more about her, her books and her awards at: https://helenapschrader.com

Her most recent release, Cold Peace, was runner-up for the Historical Fiction Company BOOK OF THE YEAR 2023 Award, as well as winning awards from Maincrest Media and Readers' Favorites. Find out more at: https://www.helenapschrader.com/cold-peace.html

February 13, 2024

Why I Write Historical Fiction - Guest Blogpost from Jean M. Roberts

I am delighted to host my first guest blogger. Jean M. Roberts,former nurse, voracious reader, ancestor hunter and occasional gardener, is theauthor of five historical fiction books. She maintains a blog, The Book’sDelight, dedicated to all things books. She lives near Houston with her family.When not writing, she’s thinking about writing.

I fell in love with historical fiction as a youngteenager. Daphne du Maurier, Anya Seaton, and Barbara Erskine thrilled me withtragic tales of love and adventure. My passion for history continued intoadulthood as I devoured books by authors new and old. Sharon Kay Penman’s epicnovels of the War of the Roses are still favorites. My bookcases groaned underthe weight of nonfiction tomes on the Tudors, the Plantagenets, the RomanEmpire and Colonial America.

I fell in love with historical fiction as a youngteenager. Daphne du Maurier, Anya Seaton, and Barbara Erskine thrilled me withtragic tales of love and adventure. My passion for history continued intoadulthood as I devoured books by authors new and old. Sharon Kay Penman’s epicnovels of the War of the Roses are still favorites. My bookcases groaned underthe weight of nonfiction tomes on the Tudors, the Plantagenets, the RomanEmpire and Colonial America.When I planned my first book, I knew it would behistorical fiction. The beauty of this genre is the freedom to incorporatealmost all other genres into your story. Romance, Fantasy, Magical Realism,Paranormal, Suspense, Murder Mystery and more, all set in the past. Writinghistorical fiction is also a great excuse to read more history, dive deep intoa time period, scour the internet and library for tidbits to fill the pageswith authentic details. There’s nothing as glorious as a historical rabbit hole,spending hours lost in time, mining the past for clues.

As an author, writing historical fiction has also beena vehicle for me to tell the history of my ancestors. The genealogy bug bit memany years ago and found the fleeting traces of my ancestors fascinating butsterile. I wanted more than just names and dates. What were their lives like?How did they live, love and die? What were the major events that affected theirlives? Writing Blood in the Valley, set before and during the AmericanRevolution, took a deep dive into the Mohawk Valley of New York. I was luckyenough to travel to the area and spent a week exploring places where mycharacters live and fought for their country. I’ve written several books thatinclude my distant ancestors. It brings them alive to me and my readers.Nothing is more satisfying than getting an email from an unknown distant cousinthanking me for writing the story of our shared ancestor.

Another love of mine is time travel. Du Maurier’s Houseon the Strand and Seaton’s Green Darkness captivated my imaginationwith their different modes of viewing the past. I’ve written several books withelements of time travel and it’s so much fun to put your modern day characterinto the past and watch them try to survive. In The Angel of Goliad, I plunk mymain character down in the middle of the Texas Revolution and let her tell thestory of the real Angel of Goliad, Francita Alavez. Of course, a trip to Goliadto see the sight of the massacre was warranted, and I got to walk in herfootsteps.

I’ve always been a bit of an anglophile, aided andabetted by my years living in England. Covid allowed me to indulge myself bywriting a historical fantasy blended with elements of Roman mythology. Ireincarnated my poor main character over and over and put her in all myfavorite moments of English history. The Frowning Madonna is my covidode to England.

My current WIP, Midsummer Women, is a dual-timeblend of history, suspense, with elements of witchcraft, and a whiff of thesupernatural. Like most of my books, my main historical focus is early Americanhistory. It includes the story of the little known and ill-fated Popham Colonyin Maine, settled at the same time as Jamestown in Virginia. That trip to Maineis in the planning!

I think my writing is a good example of the umbrellathat is historical fiction. I write pure historical fiction, playful historicalfantasy, gothic suspense, and exciting time-travel all while bringing historyalive for my readers. I cannot think of a genre that allows such freedom andjoy to write what the mind can imagine.

Buy now on Amazon

Buy now on Amazon

Blog Host Helena P. Schrader is the author of 25 historical fiction and non-fiction books, eleven of which have one one or more awards. You can find out more about her, her books and her awards at: https://helenapschrader.com

Her most recent release, Cold Peace, was runner-up for the Historical Fiction Company BOOK OF THE YEAR 2023 Award, as well as winning awards from Maincrest Media and Readers' Favorites. Find out more at: https://www.helenapschrader.com/cold-peace.html

February 6, 2024

Why I Write Historical Fiction

Why Write Historical Fiction?

As the author of nineteen historical novels, I am often asked why I write historical fiction. It is an intriguing question, so I decided to put this question to other historical novelists, and see what they had to say. Over the next four and a half-months, I will share their answers in this space. I hope my readers enjoying meeting these different writers as much as I did! But first, my personal answer to the question.

Objective, scholarly history provides facts, statistics, data, evidence, verifiable quotes, information and analysis. Well-written history can bring history back to life and help us experience historical events. It can be thrilling, moving, and inspiring. Yet there are also many things good, academic history cannot do because history is tied to evidence. Historical evidence may come in the form of archaeological and pathological findings or through written and photo records including court documents, letters and diaries, inventories, ship manifests, burial registers and the like. But evidence like that is often lacking, lost to "the ravages of time." Indeed the overwhelming majority of what forms the facts of history have been destroyed over time -- in natural disasters like earthquakes, fires, and floods or through human action from war, economic development, and simply 'cleaning out the old shed.' Where evidence is lacking, historians can put forth hypotheses or suggest plausible explanations. However, serious historians usually offer multiple theses for any unusual development or dubious event. Some aspects of history are, however, particularly elusive. The motives of humans, for example, cannot always be imputed from their actions -- or their words. Memoirs and even diaries are notoriously deceptive. In consequence, the farther we go back in time, the more imperfect and imprecise the historical record becomes. Like a sphinx eroded by three thousand years of desert sandstorms, the historical record often lacks clarity and color and details. Yet it is precisely those aspects of a picture which make it attractive to humans.

Historical fiction, on the other hand, can go beyond the historical record. It can "connect the dots" and extrapolate beyond the point where credible historians dare to go. A novelist can offer an interpretation of historical events and characters that completes the imperfect image left by the remaining evidence. It can build upon the eroded remnants and restore a bright, vivid and vibrant image of the past. Let me take a concrete example from my own biography. At the age of four, I visited the Colosseum in Rome. The tour guide could explain the history in great detail, but my father triggered my imagination with a single fact: "This is where they fed the Christians to the lions." Now, a scholarly history of the Colosseum can probably tell us the exact date when this practice started and ended. It can probably tell us how many Christians died, possibly the names of many. I may be able to cite individual cases in which the Emperor intervened to save one or another Christian. It might tell us where the lions came from and how they were transported to Rome. But it cannot and would not tell us what it felt like to be a fifteen-year-old girl who is condemned along with her family to face the lions before a crowd of spectators. I cannot tell us the thoughts of a lion handler, angry to see his noble lions abused and starved until they are turned in to man-eaters. It would not describe being in the stands in the heat, buying snacks from the vendors and listening to gossip, while people are torn apart by wild beasts on the sand in the arena. A novel about the Colosseum can bring it back to life and reach us at an emotional level in a way that no history book can.

Personally, I have been most inspired to write novels about eras, societies or events that are popularly misunderstood. That is, when I realize there is a major disconnect between what serious history tells us about someplace or some age and what most people believe, then I get inspired to "correct the record." My novels on Sparta and the crusader states grew out of this need to make the historical facts as uncovered by meticulous scholarly research more accessible to people who couldn't be bothered reading about these things. Likewise, my novel Moral Fibre was inspired by misconceptions about the RAF's procedures and polices regarding men who "lacked of moral fibre."

For more about my novels on Ancient Sparta visit: https://www.helenapschrader.com/ancient-sparta.html

For more about my crusades era novels visit: https://www.helenapschrader.com/crusades-era.html For more about books set in WWII or about military aviation see: https://www.helenapschrader.com/aviation.html

January 30, 2024

Why I Write

For the last five years, I have concentrated on writing full-time. I've released one new major work of non-fiction, published two new novels, an anthology of three novellas and re-launched three earlier works. All that represents massive emotional and financial commitment, time and sheer hard work.

It is legitimate to ask, if it is all worth it?

The answer is simple: financially, not on your life. Emotionally, definitely.

The answer is simple: financially, not on your life. Emotionally, definitely. But, you may ask, do I find so emotionally satisfying about writing? Why do I write?

I've tried to analyze this before and I've come up with lots of reasons: to learn, to teach, to share, to entertain, even to pray because I believe that my writing is inspired and when I write I am communicating with the divine.

Yet, the simplest answer is that it gives me an opportunity to be more than I physically am. Writing enables me to go beyond the constraints of my body. Through my characters, I can become a better human being, a stronger, more generous, more courageous, or more loving person. My characters are my better self and through them I can envisage a better world. My writing inspires me to go on living.