Deb Vanasse's Blog: Book Birthday!, page 15

June 4, 2013

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Gate: New Thinking on How to Publish

Until recently, I’d never heard the term hybrid author. Now I’m about to become one.

It all started last year, when I was on faculty at the North Words Writers Symposium and discovered that some of my colleagues – writers whose work I admire – were swearing off traditional publishing. No ifs, ands, or buts: they were done. These are people with agents and multiple books with big New York houses. Other writers I know and admire had already reached the same conclusion, including Ned Rozell and David Marusek, who’d shared what they’d learned about digital publishing at another blog I help run, 49 Writers.

Hmmm. I thought a little about the phenomenon, but not too hard. I was working on two big projects, one literary novel and one narrative nonfiction, and wasn’t concerned yet about how they’d reach readers.

Flash forward to this spring. Raves came in from respected beta readers on the literary novel, now finished. I made my first runs at the usual gates – the agents who get you to the editors who get you to the sales teams. Having traditionally published twelve books, I knew how to do this. Research. Query. Submit on request. Wait. Wait. Wait. Revise query. Wait. Wait. Wait.

“I am rooting for you and this novel,” one agent responded. “I truly loved your writing, and devoured what you wrote,” wrote another. But despite the positive comments, I got no takers on round one. “This may be owing mainly to my own overload,” one agent said. “I have about a dozen novels that I need to plow through before I can get to yours,” said another.

I stopped right there, and took a good hard look at the gate.

As it happened, I’d recently learned a lot about digital publishing. Every since the digital revolution began, I’d been telling myself I needed to bring out my first two novels, now out of print, as e-books. But I’d never gotten around to it. This spring, inspired in part by a revision project on a collaborative novel I’d done with Gail Giles, I carved out some time to research the digital publishing process.

Here’s what I found that convinced me to become a hybrid author, with one foot in the traditional publishing world and with the other bypassing the gates:

As the digital revolution unfolds, angst and uncertainty among traditional gatekeepers is only increasing, making it harder for them to take on new projects. Understandably, there’s a lot of watching to see how things settle out.The stigma on self-publishing that goes back to the days of vanity presses is dissipating as good authors with good books put them out in digital format. Is there still an ocean of crap out there? Absolutely. But readers are smart. The good stuff will float to the top, if authors do a little work to make sure they get noticed. Also, releasing your own work in digital format used to discourage traditional publishers from picking you up later. Not any more.The work authors do to get noticed is virtually the same these days, no matter how you publish. Unless you’ve got huge name recognition, you’re going to do blog posts and blog tours. You’re going to maximize your presence on Author Central and Goodreads Author. You’re going to have a social media strategy. As my friend David Marusek points out, a big advantage of the hybrid author is confidence, the kind you get from having passed through the gates. Reviews in the big-name publications (Kirkus, Publishers Weekly, Booklist) on previous books, selection of those books for industry honors, and the response of readers all help to generate that confidence. The hybrid author also knows, to the extent that anyone can, how the publishing biz works.By bypassing the gates, hybrid authors enjoy two huge advantages: control and profit. Of these two, artistic and marketing control matter most. Profit is nice, too (although real artists aren’t supposed to talk about it). The irony is that if you’re bringing your own work to readers, your marketing and promotion responsibilities are actually lessened, in that you can sell a lot fewer books and still put food on the table.With these advantages come responsibilities – but in my case, these are responsibilities I’m well-trained for. For several years, I’ve done developmental and line-editing for hire. Don’t get me wrong – I still use multiple strategies to get editorial advice on my books, because I want them to be the best books they can possibly be, and because I know every author has blind spots when it comes to her own work. But I’ve learned a lot about editing my own work by editing for others.Artists can and should use both sides of their brains. In getting to the place where I can write full-time, I’ve run businesses. I do spreadsheets. I can estimate profit and loss. I do marketing plans. That I do so in no way diminishes my creativity. They are separate functions.The production part is easier than you think, and getting easier by the day.The revolution is bigger than you think, and it’s getting bigger every day with the other big game changer, Print on Demand, which is revolutionizing the way booksellers order and stock books from all publishers, big and small.I’ve been at this awhile. I know myself pretty well. At this point in my career, I don’t covet big awards. I don’t worry a lot about reviews. I don’t need to be a star. I love to write. I want to tell good stories. I want them to reach readers. That’s pretty much it.I’m disturbed by the so-called experts who proclaim that digital writers must spend 80% of their time on marketing and 20% of their time on writing. I’ve set out to prove that writers can and must flip those numbers around: 80% of their time on writing, 20% of their time on marketing. (Stay tuned for how that plays out.)As documented in research by Dr. Alison Baverstock, indie authors (a broader term that encompasses hybrid authors as well as those who bypass the gates entirely), this new breed is a remarkably collaborative and helpful bunch. That makes the whole process much more pleasant (and efficient) than I’d ever dreamed. (Stay tuned for my upcoming post, A Tale of Two Covers, for a detailed example.)Good, smart people like Guy Kawasaki are also making the process easier. Reading his APE: Author, Publisher, Entrepreneur (and joining the Google+ APE community) empowered me to move forward with this paradigm shift. He also coined the term artisanal publishing, which is pretty cool.The time is now. This is a sorting out period. When I was first contemplating whether to do anything other than my out-of-print books as digital releases, I did a lot of searching for other literary authors who’d taken the plunge. As I started to get distressed over how few I was finding, my left brain delivered a revelation: from an entrepreneurial perspective, that’s called opportunity.

Like my colleagues at North Words, am I done forever with traditional publishing? I doubt it. I like the idea of straddling the gate as a hybrid author. Next week, you’ll see the release of my first “artisanal” e-book, Out of the Wilderness, the digital version of the novel that came out several years ago. In the coming weeks, I’ll be talking more about Running Fox Books, a related venture that extends a goodwill platform to select hybrid authors.

Published on June 04, 2013 08:00

May 28, 2013

Finish the Book

Endit.

I typed this happily last week, on two different manuscripts. One is Cold Spell, a book that over the past three years has shape-shifted from the story of a woman who searches for her missing mother to the story of a woman who’s obsessed with a glacier. The other is No Returns, a novel for younger readers that I drafted five years ago with a good friend, then set aside.

If you’ve ever finished a book, you know it’s a lot like getting a diploma. There are parts of getting there that you love. There are parts you hate. At times the process seems endless. Getting to the end feels heady. It feels scary. You feel nostalgic. You feel proud – and well you should – but doubt plagues you. Are you really finished?

Endit is a state of mind. It’s also a process. Unless you recognize both of these truths, your elation at ending – and quite possibly the success of your book – will be short-lived.

To get to the finish, and to help you know when you’ve arrived, keep these precepts in mind:

When the end’s in sight, there’s a natural tendency to hurry things up, which hurts the pacing of your book. Writing may feel like a marathon, but trust me: a sprint to the end won’t satisfy your reader.You’ll finish your book many times before you’re through. Cold Spell isn’t really done; it’s ready for the proofreader. No Returns isn’t finished either – only the latest draft. If you’re a serious writer, concerned about quality, you’ll enjoy multiple Endits. You’ll finish multiple drafts of every book You’ll finish at least one round – likely more – of line edits. You’ll finish a copy-edited version. Set up these gates for yourself and celebrate an Endit as you pass through each.Use deliberate strategies to become more and more objective about your work. If you compose on the keyboard, print out your manuscript and do the next pass on paper, or send it to your e-reader so it looks like a book. Try reading your whole book out loud. If you can afford it, hire a developmental editor and a proofreader. For a cheaper alternative, try your book out on beta readers, the more objective the better. They’ll let you know when you’re finished.Don’t be seduced by your achievement. Know where you’re most vulnerable, and once you’ve finished your draft (not before!), set your radar on your known weaknesses. Every writer worth her ink (that includes digital) should know, front and center, her three greatest strengths and her three greatest flaws as a writer. Kafka had this one-word reminder posted at his writing desk: Wait. Build wait time into your process, preferably a few weeks after each pass through the book. You’ll be amazed how much more you’ll see, and how much better your book will become. Just don’t wait forever.

For more about endings in fiction, check out this post from the archives.

Published on May 28, 2013 13:03

May 21, 2013

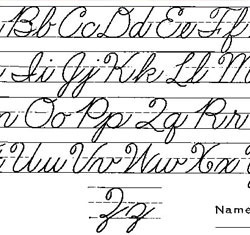

Goodbye, Cursive: Why I’ll Miss You

I spent second grade trying to please Mrs. Rebscher. She had a paddle, and she wasn’t afraid to use it on any seven-year-old who got out of line. Under her watchful eye, we worked hard on our penmanship. Graduating from printing to cursive was proof we were growing up.

If Mrs. Rebscher could see what a mess I’ve made of my handwriting, she’d be reaching for that paddle. My signature is almost as bad Jack Lew’s loop-de-loops, my day-to-day cursive only slightly more readable.

Still I was sad to learn that longhand is going the way of the typewriter. The Common Core State Standards don't require it, so more and more schools are swapping out the teaching of cursive for lessons in keyboarding, which is deemed practical, fast, and efficient - the same advantages that cursive once had over printing. Before long, cursive will be like Gregg shorthand, a quaint and old-fashioned novelty, or like calligraphy, an art practiced by people with too much time on their hands.

I understand we have to move on. But my sadness is not just nostalgia. There are good reasons why I’ll miss cursive:

· Longhand reveals who we are in ways that printing does not. If you want to check this out for yourself, write the sentence She sells seashells by the seashore. Then go here for a little analysis. Through this short exercise, I learned that the slant of my letters affirms that I’m open and like to socialize. The size of my words indicates that I’m well-adjusted and adaptable. The way I write e’s and l’s shows that I’m somewhat skeptical and unswayed by emotional appeals (sorry, PTL Network).· Handwriting changes as we change. It documents our growth. As years intervened between Mrs. Rebscher and me, I quit connecting some of my letters. My loops have gotten larger. Other letters have compressed. My handwriting may not be all that readable, but I like it. It’s me, all grown-up (mostly). · In losing cursive, we’re not just losing a way of writing. We're losing a way of thinking. Longhand encourages right-brained messiness. Poetry, brainstorming, revision notes – for these, keyboarding just doesn’t cut it. And the kinesthetic activity of the hand on the page, joining letters, makes us feel close to our work. That’s why there are still authors who draft whole books by hand. One of them is Claire Messud, author of The Emperor’s Children. In a recent interview with Poets and Writers, she reports how writing by hand brings her close to the text. “It sounds silly,” she says, “but it used to be that when I was reading aloud from a book at a reading I basically knew it by heart.”

Published on May 21, 2013 08:00

May 14, 2013

Revision for the Rest of Us: Five Strategies for Writers

In prepping for a stint at the Kachemak Bay Writers Conferencenext month, I came across this from author Katherine Paterson: “I wish for every writer in the world an editor like Virginia Buckley.”

I was among the lucky ones; Virginia Buckley edited my first two novels. As Paterson notes, she had a gift for seeing beyond a messy draft to a real story. Guided by her gentle prodding, revision was easy. One of my deep regrets as a writer was letting an agent convince me that I needed to cast my nets beyond her shores. I would have learned much more, much quicker, had I stuck with Virginia.

These days, editors like Virginia Buckley and the venerable Maxwell Perkins (check out Susan Bell’s The Artful Edit to learn more about how he helped Fitzgerald shape The Great Gatsby ) are hard to come by. Editors are busier than ever. So are agents.

If you have the money – a few thousand dollars or so - you can hire a freelance editor. If your concept of publishing is to throw your book at the wall and see if it sticks, you can forego editing altogether.

For the rest of us, here are five editing strategies:

· As Bellexplains in her book, there are two types of editing. She calls them macro and micro; micro is often called line editing. Once a draft is finished, it’s tempting to jump straight to micro-editing: clarifying sentences, correcting language, fixing discrepancies, adjusting the balance between showing and telling. But most drafts are best served if the writer first takes the macro-view, finding and fixing problems with intention, theme, structure, foreshadowing, character, and continuity of tone. · Editing is not mopping the corners. It’s probing the entire structure, from the ground up. Treat your book like a house constructed by a well-meaning faulty builder. Search from foundation to rafters to find the weaknesses. Trust me: they’re there.· Editing happens in rounds, each one circling closer to the book’s truest and finest form. Don’t think you can do it once and be done.· When editing, don’t be the writer. Be the reader. Get distance from your manuscript. Though you’ve worked hard on your draft and you’re dying to move forward, don’t do it. Wait. Wait several weeks if you can. Then come at the book in the most objective way you can find. For me, this entails uploading my manuscript on my e-reader. That way, it looks like a book. When the waiting is over, I read with pen in hand, jotting notes in a simple lined, spiral notebook. Because I can’t fix as I go, I avoid micro-editing too soon. I write in longhand so I can get wild and messy on the page, bracketing, drawing lines and arrows to connect ideas, circling important points, writing in the margins. When I’ve finished re-reading, I have several pages of notes to guide my revision.· Engage trusted readers. Not your family, not your friends. No one who’s worried about hurting your feelings. Your trusted readers should be smart and tough. They’ll be fallible – but so are you. Either address or dismiss each comment they make. For every comment you dismiss, you should be able to articulate why.

Published on May 14, 2013 08:00

May 7, 2013

Hybrid Publishing: An Interview with Adam Glendon Sidwell, author of The Buttersmiths' Gold

It may be that we’ll look back on 2013 as the year of The Big Shift in publishing, the year the market tipped in favor of the Indie Author.

Who’ll curate? How will readers find books they love? How will authors find time to write and publish and promote? These are among the questions I explored with Adam Glendon Sidwell, whose second book, The Buttersmith’s Gold, came out last week.

On the day it launched, Sidwell’s first book, Evertaster, rose to number 51 on the Amazon Bestseller List. “And the funny thing is,” Sidwell wrote in a post for A Storybook World, “there was no one to do my marketing but me.” Sidwell had “an amazing agent” and together they had tried for years to place his work, but as editor after editor championed his story, the final decision at each house they approached was the same: “We don’t know how to sell your book.”

Evertaster was a hybrid venture between the publishing house you created and

your literary agency. Tell us a little about how this worked. In what ways has this

collaboration been helpful for you and your book? Will The Buttersmiths' Gold be

a similar collaboration?

My agent at Trident Media Group, Alyssa Henkin, provided the editorial insight and review that helps when putting a book together. Working with Alyssa is great, since she also was an editor for years at Simon & Schuster. We worked on the manuscript for two years together. Then they take care of all the copyrighting, and ebook creation, and I handle the print product. The world of publishing is wide open right now, and cooperation like this is possible. The Buttersmiths' Gold will be a similar approach.

The Buttersmith’s Gold is being marketed as a novella, which isn’t a term one

hears much in association with children’s books. Tell as how you decided on that

genre, and what it means to you as the author.

I'm calling it a novella simply because it's a shorter book -- 124 pages. Don't worry, it's not a Latin American Soap Opera! I wanted to do a story about Torbjorn and Storfjell from the first book, but this wasn't a sequel. The Buttersmiths' Gold is a spin off story, and you see novella being used to describe shorter books all across genres. It was the most fitting description.

What do you think are the top ways in which young readers found out about

Evertaster? In what ways are you replicating and refining the marketing reach for

The Buttersmiths' Gold ?

It's really been word of mouth. Often from my mouth to their ears, but something they hear about with a lot of buzz. I've been sure to build up the Facebook page and the excitement surrounding the book there. Then I had a book trailer that explains the general idea succinctly. And after that, I spent a lot of time touring and meeting people. It was great. I will continue to tour with The Buttersmiths' Gold .

To what extent do you find young readers embracing the e-book format? In what

ways do they find out about e-books as opposed to printed books?

I was surprised to find out how far behind the e-book format lagged the print version! Only about 6% of my book sales are ebook. Which says a lot about young readers on ebook -- they're not there -- yet.

What advice do you have for writers who wonder how to balance the demands of

marketing with the time they need to create their books?

If your marketing is selling more books, keep doing it. Don't get caught up in time-drainers though. And you better ask me that question again after I've finished The Delicious City -- because it's the exact question I'm asking myself right now! I hope I'll have an answer for you then!

Published on May 07, 2013 08:00

April 30, 2013

Time to Write

“Time is grit.”

That’s how author Leigh Newman recently answered a question that writers often get asked: How do you find time to write?

Grit. It’s one of the best answers I’ve heard. But if you’re looking for more, here are seven keys to making the most of whatever time you have to write, whether it’s ten minutes or ten hours a day:

Know yourself: When David Vann’s working on a book, he writes every morning, seven days a week. Leigh Newman gets up at 4 a.m. Others do their best work at midnight. Figure out when and how you do your best work. Arrange your other obligations around whatever time you can spare.Be present: This isn’t just butt in the chair – it’s senses to the world. Figure out what most helps you feel present – a walk, a few yoga poses, meditation, a single deep breath. Half an hour, two minutes, ten seconds – it’s not the amount of time so much as the grounding itself that matters.Revel in language: Language is your instrument, your palette, your stage. Read a poem. Sing. Share a quote. It takes precious little time to embrace words.Study your craft: Read from your aspirational writers. Challenge yourself with a book on writing well in your genre. The 80/20 rule: Whether you’ve got ten minutes or ten hours, aim for 80 percent of your time actually writing, and 20 percent on everything else - the things mentioned here, plus other stuff like networking and promotion.Set limits: Identify your personal time-suckers, the ones you have control over, things like surfing the internet, social media, checking sales figures. Box these in tightly. Not only do they rob time from your passion - they also activate parts of your brain that aren’t conducive to creativity. Order your operations: After a little “be present” grounding, I start my writing sessions by copying words, lines, and phrases from poetry. Then I read in a genre I’m not writing at the moment, with a timer set so I don’t linger. Then I write, and write, and write. Don’t like routines? Discover what works for you and make it happen. That’s the grit.

You don’t have to write every day or every week or even every month. Sometimes a writer’s best move is to wait. But if you tell yourself you’ll write when you have time, or when you feel inspired, you’ll likely be waiting a long, long time.

Published on April 30, 2013 08:00

April 23, 2013

All Ate Up: Five Humble Precepts for Writers

All ate up.

I’m told this is an old Indianaexpression, used to describe someone who’s consumed by something. She’s all ate up, you might say, for instance, of a writer who’s obsessed by results.

In one sense, writers have to be all ate up. Goals and optimism and perseverance and dedication – these are essential to your work. But it’s ever so easy to get all ate up over results – not your work, but how your work is received. When you think no one’s looking, you’re checking your Amazon rankings, your earnings summaries, your Twitter follows, your Facebook likes, your BookScan sales. When grants and awards and fellowships are announced, you’re wondering when your turn will come.

Last week it was announced that Eowyn Ivey’s book The Snow Child was one of two Pulitzer finalists in fiction. Knowing Eowyn, I doubt this was a result she in any way expected. Besides being a fine writer, Eowyn is gracious and kind. At every opportunity, she’s thanking and acknowledging others for her success. She wrote the best book she could write, and now she’s on to the next one.

I started thinking about other authors I know who’ve won national or international recognition. Debby Dahl Edwardson, National Book Award Finalist for I doubt that any of these writers expected the particular recognition they received. They aren’t people who obsess over winning or results beyond producing their best writing, day after day. They aren’t “all ate up” over the many aspects of publishing that are beyond their control.

Pondering what I admire about these prizing-winning authors, I’ve distilled out five precepts to help all of us keep from getting “ate up” over the wrong things:

· Writers control products, not perceptions. When building a platform becomes a whole lot of striving, it’s time to back off.· Though some claim it’s motivational, envy is distracting at best, destructive at worst. Cultivate joy for writers who achieve recognition, and don’t fret over when you’ll get yours. Keep producing the best writing you can, and keep making it better.· When results do come, acknowledge your team. Increasingly, it takes a village to grow a book.· Cultivate gratitude, not gratification. Be aware of how social media can mess with your mind.· Cultivate grace. It will serve you in a wide range of matters beyond your control.

I’m told this is an old Indianaexpression, used to describe someone who’s consumed by something. She’s all ate up, you might say, for instance, of a writer who’s obsessed by results.

In one sense, writers have to be all ate up. Goals and optimism and perseverance and dedication – these are essential to your work. But it’s ever so easy to get all ate up over results – not your work, but how your work is received. When you think no one’s looking, you’re checking your Amazon rankings, your earnings summaries, your Twitter follows, your Facebook likes, your BookScan sales. When grants and awards and fellowships are announced, you’re wondering when your turn will come.

Last week it was announced that Eowyn Ivey’s book The Snow Child was one of two Pulitzer finalists in fiction. Knowing Eowyn, I doubt this was a result she in any way expected. Besides being a fine writer, Eowyn is gracious and kind. At every opportunity, she’s thanking and acknowledging others for her success. She wrote the best book she could write, and now she’s on to the next one.

I started thinking about other authors I know who’ve won national or international recognition. Debby Dahl Edwardson, National Book Award Finalist for I doubt that any of these writers expected the particular recognition they received. They aren’t people who obsess over winning or results beyond producing their best writing, day after day. They aren’t “all ate up” over the many aspects of publishing that are beyond their control.

Pondering what I admire about these prizing-winning authors, I’ve distilled out five precepts to help all of us keep from getting “ate up” over the wrong things:

· Writers control products, not perceptions. When building a platform becomes a whole lot of striving, it’s time to back off.· Though some claim it’s motivational, envy is distracting at best, destructive at worst. Cultivate joy for writers who achieve recognition, and don’t fret over when you’ll get yours. Keep producing the best writing you can, and keep making it better.· When results do come, acknowledge your team. Increasingly, it takes a village to grow a book.· Cultivate gratitude, not gratification. Be aware of how social media can mess with your mind.· Cultivate grace. It will serve you in a wide range of matters beyond your control.

Published on April 23, 2013 08:00

April 16, 2013

Mentoring, Anyone? Five Things Writers Should Consider

These days you’ll find an abundance of mentorship opportunities for writers, from the mentoring relationships inherent to full-blown MFA programs to mentors-for-hire who advertise online.

For several years, I’ve mentored writers both informally and for hire. Recently, I was asked by a chapter of SCBWI (Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators) to design an affordable digital mentorship opportunity, and that prompted me to think about what contributes to a positive mentoring experience.

Here are five factors you should consider if you’re thinking about signing on with a mentor:

Your expectations: A mentorship should yield improved writing and a refined sense of how you can grow as a writer. It is not, however, a guarantee of publication. Which particular areas you hope to work on with your mentor? Which aspects of publishing you hope to learn more about? As you begin to explore mentorship options, list what you hope to accomplish with your mentor. Take a hard look at these expectations and adjust based on where you are in your journey as a writer as well as how much time you can devote to improvement. Depending on what you hope to accomplish, you might be best served by a series of mentorships, either arranged independently or within the context of an MFA program.What you’ll bring to the mentorship: Before you begin working with a mentor, you should have at least a solid start on a project you’d like to improve. You should also have a sense of your strengths and weaknesses as a writer. A good mentor functions as your coach, your editor, and your critic. If you’re thin-skinned, mentoring probably isn’t for you (and writing may not be, either). As with your expectations, jot down what you’ll bring to the membership. Sharing your expectations and your self-assessment with a potential mentor will help both of you decide whether the relationship will be helpful. What else you’re doing to grow as a writer: Mentoring is a wonderful way to work one on one with a writer who can help you toward your goals, but you shouldn’t rely on it entirely. Do you read systematically both in your genre and in your craft? Do you write regularly? (One of the benefits of a mentorship, by the way, is that it gives you deadlines.) Do you study with a variety of writers at workshops and conferences? How will your mentorship dovetail with these other activities?Your options: Ideally, you want a writer who has experience as a mentor and who enjoys mentoring. You also want a writer who is several steps ahead of you in the game, a person whose writing you admire, and who has a proven track record in publishing and/or sales. As with many other professionals, the best mentors don’t need to advertise much, and they know better than to take on too many clients. Ask other writers whom they’d recommend. If you’ve enjoyed a workshop with a particular writer, ask if he or she does any mentoring. Ask your local writing center and local chapters of writer’s organizations like SCBWI if they offer mentorship opportunities. Although the ideal mentoring relationship might be with a writer in your genre, that’s not essential. I rarely write short nonfiction (except for blog posts), but one writer I mentor only writes essays, and most of the projects she has worked on with me have been published. It goes without saying that a good mentor will be able to provide references and testimonials upon request.Your relationship: I’m a big believer in the preventative power of the written word. If your potential mentor doesn’t offer a written description of how the relationship will work, don’t be shy about asking for one. How long will the relationship last? How will you communicate back and forth? How often? Will both macro- and micro-editing be included? If the relationship’s not working out, can it be dissolved? Will your mentor work with you on building a career as a writer? How much will it cost, and how is the cost billed? Every mentor handles these questions differently. For both macro- and micro-editing, you can expect to pay in the $50 per hour range.

For several years, I’ve mentored writers both informally and for hire. Recently, I was asked by a chapter of SCBWI (Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators) to design an affordable digital mentorship opportunity, and that prompted me to think about what contributes to a positive mentoring experience.

Here are five factors you should consider if you’re thinking about signing on with a mentor:

Your expectations: A mentorship should yield improved writing and a refined sense of how you can grow as a writer. It is not, however, a guarantee of publication. Which particular areas you hope to work on with your mentor? Which aspects of publishing you hope to learn more about? As you begin to explore mentorship options, list what you hope to accomplish with your mentor. Take a hard look at these expectations and adjust based on where you are in your journey as a writer as well as how much time you can devote to improvement. Depending on what you hope to accomplish, you might be best served by a series of mentorships, either arranged independently or within the context of an MFA program.What you’ll bring to the mentorship: Before you begin working with a mentor, you should have at least a solid start on a project you’d like to improve. You should also have a sense of your strengths and weaknesses as a writer. A good mentor functions as your coach, your editor, and your critic. If you’re thin-skinned, mentoring probably isn’t for you (and writing may not be, either). As with your expectations, jot down what you’ll bring to the membership. Sharing your expectations and your self-assessment with a potential mentor will help both of you decide whether the relationship will be helpful. What else you’re doing to grow as a writer: Mentoring is a wonderful way to work one on one with a writer who can help you toward your goals, but you shouldn’t rely on it entirely. Do you read systematically both in your genre and in your craft? Do you write regularly? (One of the benefits of a mentorship, by the way, is that it gives you deadlines.) Do you study with a variety of writers at workshops and conferences? How will your mentorship dovetail with these other activities?Your options: Ideally, you want a writer who has experience as a mentor and who enjoys mentoring. You also want a writer who is several steps ahead of you in the game, a person whose writing you admire, and who has a proven track record in publishing and/or sales. As with many other professionals, the best mentors don’t need to advertise much, and they know better than to take on too many clients. Ask other writers whom they’d recommend. If you’ve enjoyed a workshop with a particular writer, ask if he or she does any mentoring. Ask your local writing center and local chapters of writer’s organizations like SCBWI if they offer mentorship opportunities. Although the ideal mentoring relationship might be with a writer in your genre, that’s not essential. I rarely write short nonfiction (except for blog posts), but one writer I mentor only writes essays, and most of the projects she has worked on with me have been published. It goes without saying that a good mentor will be able to provide references and testimonials upon request.Your relationship: I’m a big believer in the preventative power of the written word. If your potential mentor doesn’t offer a written description of how the relationship will work, don’t be shy about asking for one. How long will the relationship last? How will you communicate back and forth? How often? Will both macro- and micro-editing be included? If the relationship’s not working out, can it be dissolved? Will your mentor work with you on building a career as a writer? How much will it cost, and how is the cost billed? Every mentor handles these questions differently. For both macro- and micro-editing, you can expect to pay in the $50 per hour range.

Published on April 16, 2013 08:00

April 12, 2013

2013 Writeathon over...but you can still donate! Final update: 10:09 pm

My final session:

1599 words

First line: "Lunch came as a big relief."

Last line: "Dr. Faustus is the classic.”

Total revision of "No Returns" during writeathon: 4221 words! Thanks so much, everyone!

1599 words

First line: "Lunch came as a big relief."

Last line: "Dr. Faustus is the classic.”

Total revision of "No Returns" during writeathon: 4221 words! Thanks so much, everyone!

Published on April 12, 2013 23:21

Writeathon update 9:04 pm

Woo-hoo! 1045 words (keep in mind I'm revising, so some of these were already written)Starting line: "I’d rather face down a pack of snarling wolves than meet up with a guy who looks like James Cagney."Ending line: "

Published on April 12, 2013 22:05

Book Birthday!

Happy Birthday to my latest book, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/5...! Thanks to West Margin Press for bringing it into the world and to authors C.B Bernard, Bill Streever, Gary Krist, Caroline V

Happy Birthday to my latest book, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/5...! Thanks to West Margin Press for bringing it into the world and to authors C.B Bernard, Bill Streever, Gary Krist, Caroline Van Hemert, and Kim Heacox for their endorsements!

...more

- Deb Vanasse's profile

- 39 followers