Deb Vanasse's Blog: Book Birthday!, page 9

June 24, 2014

The Successful Writer

In a recent workshop on publishing, I opened the session with a brief exercise. First, I asked participants to write for a few minutes about the fantasies that all of us have about becoming successful writers: if in five years, each and every one of their writers’ dreams were fulfilled, how would it all look, in terms of income, recognition, their body of work, and how they spent their time (creative vs. production/promotion).

Then I asked them to take a few more minutes to consider each of those areas—income, recognition, body of work, and how they’d be spending time—in terms of what they realistically thought they could achieve within five years.

This exercise takes only a little time, and the results are revealing. Lurking within every writer are fantasies which, for the most part, we shy from acknowledging—the what-ifs and it-could-happens. By bringing these forward, we can learn a lot about what defines success for us: money, fame, awards, the work itself, the creative life.

When we take a moment to examine them, we find that our ideas about what would make us feel successful as writers are often misguided—either internalized from others or skewed toward factors over which we have no control.

After my first two novels came out, both with big New York publishers, I was working sixty-plus hours a week at my day job and struggling to keep writing. But I wanted to eventually make a living as a writer, which led me to think I needed to keep publishing, so I set a goal of having a book a year published (through a traditional publisher; this was back when I would never have considered self-publishing). I came fairly close to my book-a-year goal, but to do it, I ended up doing some travel books on contract—time that in retrospect I wish I’d spent honing my craft. If I’d done the fantasy/reality five-year exercise, I’d have figured out that for me, it’s the work itself and the creative life that matter more than accumulating publishing credits.

That point was brought home this week when an author copy of my forthcoming novel, Cold Spell , arrived in the mail. Compared to my previous thirteen titles, this one feels different. It’s the book I always wanted to write, the one that’s most like the books I love to read, and it’s the result of what I call my DIYMFA (do-it-yourself MFA), in which I worked hard to learn how to write the very best novel I could. Some authors I hugely admire have written beautiful endorsements of it, and early readers have told me that even after they’d finished reading, they couldn’t stop thinking about it. That feels like success.

Would I also like a six-figure advance? A Pulitzer? A National Book Award? Sure. But I can’t control whether I get those or not. And great as they sound, there’s always a downside. For big award-winners, there’s horrible pressure regarding the next book. And even the six-figure advance has its downside—if you don’t believe me, read the interview with Cheryl Strayed in the most recent issue of Scratch (a publication to which you should subscribe if you’re serious about making a living as a writer).

If you don’t think consciously about how success looks for you as a writer, you’re going to be pushed about by comparing yourself with others—sales figures, accolades, book deals, and more. You can end up spending a lot of time and energy chasing your tail around aspects of authorship that don’t matter as much as you might think.

Published on June 24, 2014 08:00

June 17, 2014

On a Budget: Write Your Book without Going Broke

As I’ve said here before (not that it’s any big revelation), there’s not a lot of money in books. So most of us authors (even big sellers like Jonathan Franzen, I was pleased to learn) go about our lives in a less-than-extravagant way.

Fortunately, you don’t have to break the bank to write books. A few thoughts on where you can cut corners—and where to splurge:

· I understand that some writers prefer to record their thoughts in beautiful, expensive journals as a way of honoring their work. But my thinking is exactly the opposite—I like to be messy with my ideas, and I don’t want to cling to words that aren’t worthy just because I wrote them on expensive papaer. So I use spiral composition books for all my writing, purchased ten for a dollar at back-to-school sales. In the red ones, I keep my weekly to-do lists, one page per week; in the blue ones, I keep my creative work—quotes, ideas, revision notes, brainstorming; in the purple, my notes on production and promotion. The rest I reserve for specific projects.· I’m addicted to writing with certain pens, but I keep my addiction affordable—Uniball 207 signos that I purchase in bulk, for about a dollar a piece.· In addition to an external hard drive, I use Dropbox (free) for file backup; I save everything there as a matter of course.· To extend the life of my laptop (five years and counting; wish me luck), I use a netbook when I travel.· I use Mailchimp (free) for my e-newsletters, and I use PicMonkey (also free; maybe a cousin to Mailchimp?) for certain projects, like audiobook covers.· Obviously, a good word processing/spreadsheet/presentation program is essential—and you should learn how to use it. After much resistance, I finally upgraded to Word 365, a subscription service ($99 per year). The time I’ve saved thanks to its enhanced features (not to mention the free tech support) makes me glad I switched. I’m no whiz at Excel, but I know it well enough to save myself all sorts of time by using it to keep track of everything from research material to mailing lists to marketing plans. · A book budget is essential—no respectable writer can do without reading, including the work of your friends and colleagues, which you’ll want to buy new. For other titles, I keep a reading list in the back of my creative notebook and pick up them up at Powells (used) and also at the library. · For books I bring out independently, I prefer contracting a la carte for the parts I can’t do myself, such as cover design, as opposed to purchasing an author services package. (I love working with Cyrusfiction Productions; Cyrus is professional and affordable.) For print books that aren’t with a publisher, I use Print on Demand through Lightning Source and CreateSpace so that I don’t have to deal with inventory and warehousing. · For promotion, I’ve learned that a whole lot of what sells books doesn’t cost a thing, other than some time, which I personally limit to 20% of my overall time for writing, so that my primary focus remains creative.

Published on June 17, 2014 08:00

June 10, 2014

Book Promotion: Bundling Works

Because we’re both fans of the same blog, The Business Rusch, my friend David Marusek and I read at the same time a post that mentioned book bundling, and we both had the same idea: let’s make it easy for readers to discover the real Alaska, minus the hype and minus the cost, by creating a free bundled eBook.

So we put the challenge to ten of Alaska’s finest authors: to share unique and intimate prose—some previously published, some brand new—that reaches beyond the usual media stereotypes of Alaska. The resulting collection, the Alaska Sampler 2014 , features fiction, memoir, biography, and humor that lay bare a cherished and primal land. Dana Stabenow, Howard Weaver, Don Rearden, and Ned Rozell are among the contributors.

“Our selections range all over the literary landscape,” says Marusek. “As we swerve from adventure to opinion and biography to humor, you’d best keep both hands on the wheel.”

Unique to this ebook is a partnership with brick-and-mortar bookshops in Anchorage, Homer, Palmer, and Skagway; each Sampler selection includes a link to annotated store listings, aiming to get beyond the either-or thinking about books that are downloaded and books that readers hold in their hands.

For those who are thinking of creating their own book bundles, here’s our advice:

· · Approaching authors: For this initial bundle (we plan to do one every year), we approached ten authors whose work would add value to our Alaska-themed bundle. These authors needed to either own the digital rights to their work or be able to get reprint permission from their publishers. They also needed to be forward-thinking in their understanding of our purpose in offering the book for free—that by aggregating high-quality prose, we’d be getting cross-readership, plus the advantages of marketing together.· Legalities: We procured signed agreements with all contributors, and we signed agreements with one another, with David as the production person and me as the editorial director. The project is officially housed with Denali Ventures, a sub-S corporation doing business as Running Fox Books.· Production: David is a master at graphic design and eBook production, so he handled the cover and the manuscript conversion. We used social media to get input on covers in draft and we used Dropbox for file sharing. We assembled the contributions into a “bible” that we updated as we went along.· Partners: We appreciate independent booksellers, and we didn’t want them out of the loop by producing in digital format. So we offered annotated bookshop listings within the book, and we feature our bookshop partners on our webpage and in our newsletter.· Timeline: We came up with the idea in March, with the goal of releasing in time for Alaska’s big influx of summer tourists. Next year, we’ll start earlier.· Proofing: I proofed the contributions; once assembled into the initial “bible,” they were returned to the authors for their proofing. Then David proofed the entire book, and we did a short beta launch during which our authors re-proofed before our official launch on June 5.· Availability: I created a “freebie” page on the Running Fox website so that readers could easily access links for downloading the book in all formats. We made the book free wherever we could (Kobo, Inkbok, Instafreebie) and listed it for 99 cents on Nook and Amazon, with links and side-loading instructions so that readers could load to Nook and Kindle directly from our webpage.· Promotion: On launch day, we urged our authors to broadcast to their contacts. We also sent out a press release and an e-newsletter. Within a few hours, we’d hit #1, #2, and #5 in our Amazon categories. Amazon’s bots took note, and within twenty-four hours, the book became free on Amazon—exactly what we’d hoped for. In the same one-day period, our website received ten times the traffic it normally gets in a week. We’ll continue promoting the Sampler through blogs, social media, and sites that feature free books and/or Alaska-themed material.· Follow-through: Together, David and I have so far clocked over 180 hours of work on the Sampler. We believe it’s worth it in terms of exposure and cross-marketing. Collectively and individually, we’ll be tracking the impact of the Sampler on traffic and sales.

Readers can download the Alaska Sampler 2014 for free at www.runningfoxbooks.com, or directly from Amazon and Kobo.

This post also appears at www.selfmadewriter.blogspot.com.

Published on June 10, 2014 08:00

June 3, 2014

What Authors Should Know: Proofreading Matters

The person who points out to a business owner that an apostrophe is misused on a sign? That’s me: former English teacher, grammar geek. So it’s no surprise that proofreading matters to me. A lot.

Does it matter to anyone else? Absolutely.

Most of us spent at least twelve years in school with teachers who encouraged us to look closely at language in order to understand how it works so we could use it properly. With some, these lessons took greater hold than they did with others, but in a certain sense, that hardly matters. The point is that our mere exposure to matters of punctuation, grammar, and usage make us question anything that looks amiss, even if we can’t quite articulate what’s wrong.

One of the largest complaints I hear from readers of self-published books is the lack of attention to proofreading. I worked with one author who had a particularly compelling story, a real-life adventure that only he could tell. After opting to self-publish, he devoted his entire budget to offset printing and relied on friends to proofread. The result is a professionally bound book with a fine cover and a text that’s nearly unreadable because of the errors.

Within the author services arm of the rapidly expanding self-publishing industry, I’ve found some rather shocking inattention to detail. Two examples:

· “[Name of company], book publishers, has established a legacy of providing authors opportunities for expression, preserving histories and stories, and bringing joy to readers and writers; and, doing so in an atmosphere of mutual respect and integrity.” What’s wrong here? The semicolon is used incorrectly, and the last item in the series is not structurally parallel with the others.· “[Name of author services person] discovered his love for the written word in Elementary School, where he started spending his afternoons sprawled across the living room floor devouring one childrens’ novel after the other and writing short stories.” Here there’s an error in capitalization (“elementary school” is only capitalized when the entire name of the school is given) and an apostrophe error.

I’d be leery of contracting with either of these individuals for help with my books. Their business is language, yet they don’t care enough to get it right in their promotional materials.

I hope you’re among the authors who respect their readers enough to want to get it right. Here, some thoughts on how to approach proofreading:

· You don’t have to be a grammar whiz in order to write a great book. I know plenty of great writers who are rough around the edges when it comes to the rules, but their work is brilliant. Know your limitations, learn what you can, and hire out what you can’t do yourself.· Get a copy of the Chicago Manual of Style and use it to look up what you don’t know. You may never understand all the rules, but you’ll eventually get most of them.· Don’t proofread too soon. Do your drafting and revisions first, and don’t let worries about mechanics interfere with your creative process.· Even when you’re a whiz at proofreading, you won’t catch everything. With work that’s familiar (like the tenth draft of a novel), our minds tend to correct as we read, so we literally don’t see errors. Enlist the help of beta readers to catch errors you might otherwise miss—but don’t expect them to do the work of a professional copy editor.· Professionally prepared manuscripts are proofed multiple times by multiple people, including the author. Even then, a mistake or two may slip through. In the fourth edition of one of my novels, I found a sentence about “insulted” instead of “insulated” coveralls - this despite the fact that the book had gone through all the rigors of copyediting and final proofing by professionals at one of the largest publishing companies in the world.· Would you embark any other endeavor—quilting, painting, building birdhouses—without learning to use the necessary tools? You may never achieve the expertise of a professional proofreader, but you should still approach language with a healthy curiosity and a desire to learn how it works. And learning the ropes with grammar and punctuation isn’t as tough as you might think. Most of what I learned about language came from a few months of tutoring a disabled veteran using a programmed grammar text.· If you’re shopping your manuscript in hopes of it being picked up by a traditional publisher, make it as clean as you can before submitting. Though the publisher has the resources tidy it up before it goes to print, first impressions matter, and few agents and editors have the time or the inclination to read more than a sentence or two of a submission that’s riddled with flaws.· If you’re publishing on your own and you’re not a professional proofreader, you should budget for one. The going rate for straight proofing is in the range of $35 to $50 per hour, or $5 per page. As with developmental editors, ask for references. Anyone can call herself a proofreader, and even some English teachers fail to grasp the nuances of language and how it’s used. Ask what you’re getting for the price. If it’s straight, simple proofing for mechanical errors, your manuscript may still have deeper problems at the sentence level: mistakes involving parallel structure, dangling modifiers, pronoun reference, and such. Line edits will address those problems, which can be even more distressing to readers than a misplaced comma or an apostrophe error. ,And never assume that an author services company does proofing; generally, their concern is only production, and in some cases, distribution.

Published on June 03, 2014 08:00

May 27, 2014

Publishing Mistakes I’ve Made (so you don’t have to)

After sixteen years and twelve books traditionally published, plus another year of independent and hybrid publishing (two re-released titles, two originals), you’d think that an author like me would be savvy enough not to make many mistakes.

You’d think.

Sadly, I have so much material for a post like this that I hardly know where to start. It’s not that I’m especially inept. It’s just that this is a business in which there are lots of ways to go wrong—and many of them can’t be foreseen.

Here, in no particular order, are a few things I wish I (and some of my author friends) had known:

· An agent can be a wonderful person to have on your team, but she should be the right match for you and your book. Sometimes, you’re better off without one.· Rarely will your publisher do what you think they should to market your book. Don’t assume they’ve got you covered.· People really do judge books by their covers. Of my four independently published books, I’ve done redesigns on two of them.· An author who’s relatively well known within her genre won’t necessarily sell well independently based on name recognition alone.· If you’re publishing independently, keep your production and promotion budgets in check. Make sure you’re investing in the right places. I recently encountered an author who spent a lot of money on production and had nothing budgeted for proofreading. His book is a mess. If you look beyond bundled author services companies to a la carte services, or use author services companies that work on a percentage basis instead of charging up front, you can minimize production costs and invest instead in making sure you’ve got a quality product that will hold up in the long term.· When it comes to promotion, most paid advertising will not deliver enough in sales to pay for itself. I know—advertising is about exposure, not sales—but if you don’t have a gigantic budget that allows you to make a really big splash, online ads here and there are not going to make much of a difference. For the most part, the most effective ways of letting readers know you’re releasing another wonderful book are also the ways that don’t cost anything. The old adage about getting what you pay for simply doesn’t apply to marketing independently published books.· The same goes for paid reviews (like Kirkus) that put your book in a “self-published” category. Unless the review is starred or featured, a self-published book is never going to get noticed by book buyers (librarians and booksellers) who pay strong attention to reviews. · If you only do what everyone else does, you may get only modest results. When it comes to reaching you audience, think creatively in order to engage with them in unique and unexpected ways.

Published on May 27, 2014 08:00

May 20, 2014

What Authors Should Know: Point of View

It’s a favorite among critique partners: the gotcha game of point of view. To play, you need only a sharp eye for inadvertent shifts in point of view. Top players earn bonus points by tossing around terms like first person peripheral, first person colloquial, authorial omniscience, limited omniscience, free indirect, and free direct.

But beyond showing off our ability to find where point of view’s not working and to use the terms ascribed to its various forms, there’s much about point of view that can help authors craft intriguing, nuanced prose that will captivate agents, editors, and readers.

You only have to know how it works. Between you and me, it’s not all that important to know what labels apply to various points of view. What matters are the point-of-view techniques you use to strengthen your narrative.

“Perhaps the most important purpose of point of view is to manipulate the degree of distance between the characters and the reader in order to achieve the emotional, intellectual, and moral responses the author desires,” explains author David Jauss in On Writing Fiction.

“The true rhetorical aim of point of view is to complicate the question, not steer the reader to one answer or another,” notes Catherine Brady Story Logic and the Craft of Fiction. “You have to consider the reader’s take on things in relation to your own and in relation to the perspective character’s and/or the narrator’s, and point of view lets you play these off against each other to shape the stakes and lend texture to dramatic tension.”

Though the topic can be complex, there’s a large pay-off in taking a little time to study and understand point of view. For starters, you might avoid having to re-write a novel, as I did four times with Out of the Wilderness before I got it right.

That’s likely why writers in Juneau asked for the 49 Writers workshop “Perspectives and Viewpoints: Exploring Point of View.” In it, we'll review the basics and terms, from first-person to third-person, objective, subjective, and omniscient, then look closely at what introductory approaches leave out: subtleties of psychic distance, transitioning between points of view, and how point of view creates character.

If you’re in Juneau, I hope you can join us on Monday, June 2 from 6 to 9 pm as we explore point of view. To register, visit the 49 Writers website.

Published on May 20, 2014 08:00

May 13, 2014

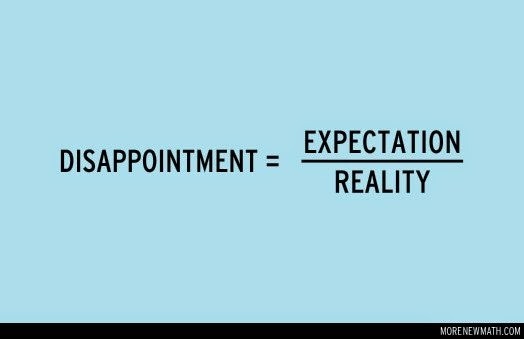

What Authors Need to Know: Book Disappointments

It has happened to all of us: we buy a book, eagerly anticipating a great read, and discover after the first chapter or two that it’s not one we care to finish. Off it goes to the used bookstore, or to delete-land, if it's an e-book.

While reading is most certainly a matter of taste, those of us who write books hope for many satisfied readers and few disappointments. Here, a few tips for authors to help make sure your satisfied readers outnumber those who trade off your books before they’ve finished reading.

· While your book description needs to get readers excited about reading what’s inside, make sure your enthusiasm doesn’t result in overreach. Recently, I came upon a newly released book deemed in its description to be a “classic.” That’s a tall order for a brand new author to fill.· Likewise, the cover needs to promise what’s best about the book and nothing more. Keep in mind this fundamental of the marketplace: negative news has ten times the reach of positive news. When you disappoint readers, the effects can be far-reaching.· Consider your price points. The more we pay, the more value we expect, and the greater our disappointment if the book doesn’t meet our expectations.· Readers are often disappointed when an author’s next book doesn’t rise to the level of the previous title. Some of this has to do with branding—in general, readers want to know what they can expect of a particular author, while the author herself might want to expand beyond a particular niche. More often, it has to do with the time the author invests in her work. As agent Susan Golomb points out in a recent interview with Poets & Writers, an author’s first book often results from years and years of crafting and development, while subsequent titles are pumped out every couple of years (unless you’re Donna Tartt). This effect is even more pronounced among authors who independently publish, as the latest “wisdom” says that the best thing you can do to build a readership is to keep pumping out books. In truth, you will only build a following if your books are consistently good. · Need it be said? Make sure you book is absolutely the best it can be. That means revision, unbiased beta readers, more revision, attention to macro and micro-editing, proofreading, professional design and formatting—in short, a book that gives you reason to feel proud, and a book that readers will want to keep on their shelves (virtual or otherwise) long after they’ve finished reading.

Published on May 13, 2014 08:00

May 6, 2014

Is Self-Publishing Right for You?

Following my post on “The Way In: Where to Publish,” a reader wrote with questions so well-articulated that I asked if I might answer in a more public forum. Here, our Q & A:

Q: I am so disappointed I can't be there for your self-publishing seminar. I just read your piece on what happened with Dana (Stabenow) after she decided to re-issue her own out-of-print titles. It certainly helped that she had a big name and a built-in following. What I'm curious about are NEW novelists who don't go through gatekeeping but who decide to digitally self-publish (the ones who do actually have their work proofread first!). How do these authors fare financially?

A: According to recent data, it’s true that hybrid authors who have already established a following among readers fare better than authors launching a first title on their own. But keep in mind we’re talking averages here. Some traditionally published authors have no idea who their readers are or how they would reach them through even a basic tool like an e-newsletter. Others, like Dana, have been effectively connecting directly with readers (hers call themselves “Danamanics”) for years.

On the other hand, there certain books from newly published authors that surprise everyone by breaking through the clutter and noise to achieve phenomenal sales. The odds are very much against this, but it does happen, for both self-published and traditionally published books. The difference, of course, is that traditional publishers do their best not only to predict the books that become big hits but also to try to make them hits by throwing lots of money into creating buzz about those titles. Increasingly, however, publishers are less likely to have such confidence (as demonstrated by large marketing budgets) in brand new authors. Q: Without a built-in audience for your work, self-promoting is a LOT of work, whether you use social media as your main marketing reach or not. It's still tough to get peoples' attentions, and when books aren't reviewed, either, well...

A: Even as the market shifts and fewer publications are doing formal reviews of new books, reviews still matter within the “literary community” — that is, for librarians and booksellers and what we might call, in perhaps a snooty way, “discriminating readers.” For these readers, reviews provide social proof; that is, the book is acknowledged as having merit by “smart” readers who move within their cultural and intellectual circles.

But of course readers choose books for many reasons. The so-called “beach read” is a great example. Even readers who care deeply about the social proof of reading well-reviewed books will choose something lighter and more entertaining in certain contexts in which reader reviews in online venues may play more directly into their choices than reviews in places like Kirkus or Booklist.

All of that being said: yes, it’s tough to get people’s attentions. When if you land a book deal with a traditional publisher, you’re going to be expected to self-promote; in fact, in weighing their publishing options, some authors have chosen the independent route because they understand that, either way, they’ll have to do most of their own marketing. Why not have control of the process while earning substantial more on each sale, these authors reason, which means of course that they need fewer sales to generate the same income.

Q: I have met someone in Europe who recently published her novel on Amazon's self-publishing division (my understanding is that Amazon also has its own imprint and that they have an editorial staff in-place for those who go through the Amazon gatekeeping route, but maybe I'm mistaken about this?)

A: Amazon is a living, breathing animal that’s always prowling new territories and adapting to market changes even as it helps create those changes. As they monitor the market and look for opportunities, they are experimenting with imprints that operate like traditional publishing, with editors and a selection process, but which also have the advantage of working outside some of the usual industry practices, incorporating strategies such as flexible e-book pricing, for instance, and print-on-demand instead of warehousing large numbers of books. Within the traditional industry, Amazon still gets branded as the evil empire, and that may potentially affect whether titles from some of its imprints get featured in bricks-and-mortar stores, but in terms of overall sales, I’m not sure how much that will matter to Amazon’s bottom line.

Q: Do we have marketing info on what genres are selling more than others in self-publishing world? Is it sci-fiction and fantasy? Or romance? Is anyone self-publishing literary fiction, for example? And what's happening with self-published NONFICTION?

A: Marketing data from all aspects of publishing, especially traditional, is notoriously hard to come by and difficult to interpret. Within the traditional system of distribution, this is primarily because of returns—there might be high front-end orders of a particular title, but when it doesn’t sell as expected, those “sales” are diminished by a high number of returned books, and the reporting on that comes in long after the launch.

In 2011, when the floodgates opened and the self-publishing stigma began to fade, the change happened first in genre fiction, especially romance, where readers care less about whether a title is reviewed in Publishers Weekly and more about when they can get their hands on the next book by an author they love. Nonfiction in certain categories also does well, especially self-help in various niche markets that are underserved by traditional publishers, who with their aversion to risk equate platform with celebrity status. Oddly, biography does well through independent channels; I’m not sure why.

Literary fiction, which is what I write, has been late to the party—or, if you think of it in another way, literary fiction is an area of self-publishing in which the market is less crowded and therefore offers some unique opportunities for authors who are willing to think outside the traditional boxes. Amazon knows this: they were one of the big sponsors at this year’s AWP, and you’ll also see their Kindle Direct Publishing on the masthead page of The Writer’s Chronicle .

In one sense, the literary community has been self-publishing for years; they just haven’t called it that. Literary journals don’t depend on traditional publishers. For the most part, the writers whose work they publish aren’t concerned about getting paid. And the readers are few – probably on par with the numbers who read the average independently published e-book. Yes, journals have gatekeepers, but other than that, the model is not all that different.

Another sign that writers who deem themselves “literary” are exploring new self-publishing options: an interview (well worth reading) on self-publishing in a recent issue of Poets & Writers.

Q: I know the stigma for self-publishing has greatly diminished but I am still one of those dinosaurs who is holding out and trying to get my manuscript picked up by a brick-and-mortar publisher. This is also why it may take me 10 more years!

A: It’s true that the stigma associated with self-publishing has diminished, and it will continue to fall away as more authors of truly fine books embrace that option, assisted in some cases by forward-thinking agents like Kristin Nelson who help their clients navigate in both arenas. Within a few years, we may even find that much of this binary thinking about publishing slips away.

I don’t see authors who hold exclusively to the traditional route as “dinosaurs.” There’s a certain validation that comes from getting through the traditional gates. Authors who’ve traditionally published, as Dana and I have, enjoy the psychological advantage of our work having been validated in this way. Authors need to follow the paths best suit them and their books.

Time is certainly one factor to consider. Waiting is important to the creative process. But waiting for someone to decide your book is worth taking a chance on in an increasingly crowded marketplace? For me, that kind of waiting is a source of huge frustration.

Q: There's this attitude from certain "writers" out there that they can just put what they want up on the Internet so that their friends and family can share in what they're doing as a kind of writing album or something, to say "I have a novel, or I have a book of poetry, and you can buy it cheap on _____." Meanwhile, other writers are working themselves to death honing their craft, going through the submission and rejection agonies, paying close attention to language, attending writing seminars and degree programs, studying all aspects of structure and storytelling, etc. And they pull their hair out or have nervous breakdowns while they wait, and wait, and wait.

A: The floodgates have opened, that’s for certain. What I see is a distinction between writer and author—and please note, I’m creating my own semantics here; others use the terms differently.

If you’re literate, you can write. And if you have something to say, something to share, and you want your friends and family to be able to read it, go ahead and put it out there on one of the digital platforms. It can cost as little as nothing. But don’t succumb to any delusions that your work will be discovered beyond your own circles.

Authors have a different mindset. For them, writing isn’t a hobby; it’s a way of life. They care deeply about craft and recognize that they’re always learning. They aim for each book to be better than the one before. On the merits of their work, they hope to connect with readers they’ll never meet, though they understand that in today’s market, regardless of how their books enter, they’ll need to be strategic about helping that happen. Are they going to wait and wait and wait for validation? That’s up to them

Books by all these people, books that are gems and books that are trash, these co-exist in the marketplace, now more than ever. With publishing that’s accessible to all, titles by “writers” will always outnumber titles by “authors.” But readers can tell the difference.

Published on May 06, 2014 08:00

April 29, 2014

But How Will They Find Us? Book Marketing and Promotion

If you’ve been publishing for any length of time, either traditionally or independently, you know that there’s little money in books. If money’s your goal, sell real estate (but make sure you’re good at it).

So let’s agree that we’re not in this for the money. Still, we’d like to have readers. How can they find us?

The odds are against a reader simply stumbling upon your book. If you don’t believe me, go ahead and put your book up for sale on all the major platforms and see who notices.

No one.

Simple principles of supply and demand are at work here. Solid figures on titles published are hard to come by, but take two recent numbers from Bowker on US publishing alone—391,000 self-published titles in 2012, and 347,000 traditionally published print books in 2011. Do a little extrapolation and it’s not hard to validate a figure that gets tossed around quite a bit: 3,000 books published per day, worldwide.

And here’s the thing: books no longer go out of print. With e-publishing and print on demand, these books will be around forever. How can your book stand out when it’s competing with a million books this year, two million next year, three million the next year, and so on?

There are some very good reasons why the average book sells only 250 copies, and why most self-published books sell fewer than 150 copies. (For more on the numbers, check out these articles in Forbes, the New York Times, and Out:think)

My point is not to discourage anyone from writing. I believe in the power of the written word and feel privileged to have been a published author for the past seventeen years. My point is that if you want more than 150 readers, you either need to convince a traditional publisher that your book will generate sufficient corporate profits after their substantial costs of production, distribution, and marketing have been met, or you need to enter into this adventure of independent publishing with both eyes open and a strategic plan for building a readership.

This week, I’ll be moderating a panel at a statewide convention on the arts that brings together writers and also musicians to address this question of how our creative work finds its audience. Since their industry imploded/exploded a few years earlier than the shake-up in the book industry, I’m looking forward to discovering what musicians have learned about “discoverability.”

Already, in our planning session, my fellow panelists have offered these helpful thoughts on discoverability, to which I’ll add a few of my own:

·

Published on April 29, 2014 08:00

April 22, 2014

The Way In: Where to publish?

Publishing has never been easy. First, there’s writing the beast, be it a poem or a story or an essay or an entire book. A large accomplishment, pouring yourself onto the page. Let’s not lose sight of that.

From there, it used to be that f you wanted readers, you had to find a way into publishing. You might submit to a journal. Query an agent or editor. Work your way through the gates. The odds were small, but writers are a persistent bunch.

With the right combination of craft and talent and luck and possibly connections and definitely perseverance, you were in. You were golden.

Well, okay. It was a start. As any published author will tell you, all sorts of struggles and frustrations are visited on authors after a book is accepted for publication. The advance is too small, which means the publisher likely does little to promote the book. Or the advance is too large, which means the author’s chances of earning out (and getting a decent offer on the next book) are slim. The books aren’t in stores. Or they’re in stores, but not face out, because the publisher hadn’t bought co-op space. The book doesn’t get reviewed. Or it gets reviewed, but the reviews aren’t starred, or glowing, even. The editor leaves the press. The agent turns her interest from the now-midlist author to the hot new talent.

And so on.

For the most part, these difficulties are as troublesome today as they were sixteen years ago, when I started publishing—maybe even more so, as the market shifts and tightens. But now there are options.

Last summer, I met up with bestselling author Dana Stabenow at La Baleine, a little café on Alaska’s Homer Spit, owned by another writer, Kirsten Dixon. I’d read in the paper that through sales of independently published reprints of titles that had previously gone out of print, Dana had earned enough to pay off her mortgage. That’s right: after an agent and thirty books in print and time on the New York Times bestseller list, Dana was reaching more readers on her own, without going through a traditional publisher.

Ever since the first rumblings about the digital revolution in publishing, I’d been telling myself I needed to get my two out-of-print (OP) books back into print. When I met with Dana, I’d finally gotten to one of them—it had been out for precisely ten days. But already I was excited. The process had been easier than I’d expected. There were nice reviews from readers. I could track in real-time how the book was faring, an impossibility with traditional publishing, owing to a complicated system of distribution.

“We have to let authors know,” Dana said. “There’s another way. They have options.”

We came up with the idea for a workshop: “The Pressure is Off: Independent Publishing Options for Writers,”so titled because with the advent of digital publishing and print on demand, the pressure is now off for writers to be traditionally published and to strive for bestseller/blockbuster status.

These days, you can make a good living—maybe even a better living—as a writer who publishes independently. But is it for you? How does a writer decide whether to go the traditional route or strike out on her own? It’s a lot to sort through. In your search for answers, what you find are cheerleaders, authors firmly in one camp or the other.

I should know. If eighteen months ago, you’d told me I’d be leading a workshop on independent publishing options for writers, I’d have laughed you right out the door. I’d been lucky enough to get through the gates, to have not just one book but several published in the traditional way. Self-publishing—well, that was for people who couldn’t get published any other way.

Authors like Dana Stabenow changed the way I think about getting books to readers. One way of publishing is not part and parcel better than the other. Authors need to know their options—not in the form of cheerleading for one camp or the other, but through a reasoned and thorough understanding of what to expect from their adventures in publishing.

Dana will open our workshop with an informal discussion of today’s publishing options. I’ll follow up with resources and strategies for deciding whether independent publishing is the right way in for you. Among the topics we’ll cover: assessment of your goals and expectations; project readiness; digital and print production, distribution, and marketing; budgeting time and money; balancing art and business; and sustaining momentum. You’ll leave knowing whether independent publishing is right for your book, and if it is, you’ll know the basics of how to make it happen.

In the spirit of the workshop, I’m also in the process of assembling a comprehensive guide to publishing, tentatively titled What Every Author Should Know, No Matter How or Where You Publish, to be released later this year. Where to publish is a big decision, and every author needs the facts to make an informed choice.

Published on April 22, 2014 08:00

Book Birthday!

Happy Birthday to my latest book, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/5...! Thanks to West Margin Press for bringing it into the world and to authors C.B Bernard, Bill Streever, Gary Krist, Caroline V

Happy Birthday to my latest book, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/5...! Thanks to West Margin Press for bringing it into the world and to authors C.B Bernard, Bill Streever, Gary Krist, Caroline Van Hemert, and Kim Heacox for their endorsements!

...more

- Deb Vanasse's profile

- 39 followers