Deb Vanasse's Blog: Book Birthday!, page 13

October 8, 2013

Alaska Book Week! Five Good Alaska Reads

On my shelves are dozens and dozens of Alaskatitles in a dazzling variety of genres and styles, books I recommend often, including some authored by good friends of mine. This week, Amy Fletcher of the Juneau Empire asked me to list five of them for a feature that runs on Thursday, October 10, in honor of Alaska Book Week.

Five - only five - out of all those books! I decided to reach back in time for those that have inspired my own writing: character-driven narratives with a brilliance of atmosphere, internalized tension, haunting language, and a keen reliance on place. Just thinking about them makes me want to drop everything and read them all over again.

And She Was , by Cindy Dyson: Brilliantly interwoven in this novel are the sagas of long-dead Aleut women and a troubled cocktail waitress, an outsider in the fishing boomtown of Unalaska in the 1980s. A page-turner with scenes and images that will stick with you for a long, long time. Blessing’s Bead , by Debby Dahl Edwardson: Edwardson gained well-deserved recognition for My Name is Not Easy, a National Book Award finalist, but I have a special fondness for this middle-grade novel, rich with history and quiet tension. Like Dyson’s book, it interweaves past and present. Just Breathe Normally , by Peggy Shumaker: A poet, Shumaker has crafted a memoir of excruciating beauty, pivoting on haunting images and scattered memories from a horrific accident in Fairbanks. A tribute to the power of the human spirit. Road Song , by Natalie Kusz: Honest, original, wise, elegant, riveting, sad, and courageous—these are among the adjectives that have been used to describe Kusz’s story. I couldn’t agree more. This is no ordinary memoir of a family’s move north. Ordinary Wolves , by Seth Kantner: I love everything about this book. Flinching from nothing, it rings true in all the ways a novel should, plus it transports you to parts of Alaska you’d likely never otherwise know. It should be required reading for every Alaskan.No matter where you live, here's hoping you'll celebrate Alaska Book Week with a great Alaska title. For the full feature, including "good reads" picks by other Alaskans, check the feature in this Thursday's special Arts section of the Juneau Empire, which also includes an article about Running Fox Books. And if you're in Anchorage, don't miss the Great Alaska Book Fair this Saturday, October 12, at Alaska Pacific University, where I'll be sharing a table with the lovely and talented Cinthia Ritchie. We'll have goodies and bookmarks and book giveaways, plus books, of course.

Published on October 08, 2013 08:00

October 1, 2013

Book Reviews: How Should Writers Respond?

I’ll begin with a confession: I haven’t closely followed the recent Goodreads reader-writer wars. What I gather through my informant—a niece who’s quite active on Goodreads and has a love for books so deep that she recently organized a campaign to get a book un-banned in her former school district—is that certain reader-writer discussions over reviews escalated to the point that Goodreads declared a new policy of removing comments that target authors personally, comments that were aggravated when authors jumped into the fray by responding to reader reviews.

Slow down, people, and take a deep breath. Reader response is part of what you signed on for when you decided to publish a book. To rail back at unfavorable reviews is more than unprofessional; it’s downright childish.

As a writer, you should covet the responses of readers, good and bad. As it happens, this month I’m leaning heavily on reader responses to guide the pre-production polishing of two of my novels—Cold Spell, a literary crossover in women’s fiction, and No Returns, a middle grade novel co-authored with the lovely Gail Giles. So I’m in a good place to offer these tips for authors who want to know how to best approach the reviews they get from their readers, both before and after publication.

· Check your ego at the door. Your book is not you. It’s not your baby. Not everyone will love it or even like it; as author Cindy Dyson points out, if someone doesn’t hate it, you’re probably not doing your job. Your book is the product of your best creative efforts, and yet it can always be better. You did set out to write the best book you could, didn’t you? Then your attitude toward each and every reader response should be gratitude.· Every response is a gift, but that doesn’t mean that you have to use it. Upon close examination, you may decide a particular comment isn’t right for you or your book; if that’s the case, stash it away. I know this is tough when the review is published online, but reviews are what they are. Learn what you can from them, and move on.· Whether a review comes from a beta reader or is delivered after publication, be methodical in your approach to it. Set your emotions aside. Read the comments. Sort them. Wait. Repeat as necessary. Use both sides of brain: analyze, and also let your intuition have at it.· Consciously hold back your defenses. Criticism is not an attack. Keep in mind that if you’re any kind of a reader yourself, it’s the rare book you’ve found flawless.· Consider where the comments are pointing. Often a reader’s response is only an opening to an area that needs work; the real problem may lie elsewhere. For instance, if a reader says your character isn’t memorable, that doesn’t mean you should give her spiked purple hair and a third eye. It may instead mean that you need to reveal more of her complexities and vulnerabilities.· Never dismiss a comment out of hand. Make response notes for yourself, in which you carefully and objectively consider each response, good and bad, and decide whether to act on it, either in a revision or your next project. Sometimes, a comment is merely a reflection of taste.· If you solicit comments from beta readers, allow time in your production or submission schedule to process and act on them. If the comments come in the form of post-publication reviews, don’t argue them, and don’t rewrite the book. Your project has met the world. If you released it before it was ready, you’re a better and wiser writer now, and you’ll learn from your mistake. If your book deserves to be forgotten, it will be. Prudence, judgment, discernment—all of these boring attributes serve a writer well.· The only response you should have for your readers is “thank you.” (See point number one: cultivate an attitude of gratitude.)

Published on October 01, 2013 08:00

September 24, 2013

Lessons from a Master: David Vann on Voice and Language

It was from David Vann that I first learned about "aspirational authors." Soon he became one of mine. Recently released is the book Vann deems his best, Goat Mountain. Booklist agrees, calling it “his finest, most contemplative work to date.” As the starred review in Library Journal notes, “Alaska-born Vann experienced catastrophic family violence in his past, and his work has returned to this theme again and again, this being his most ambitious exploration of the subject.”

Three years ago, Vann led the first 49 Writers Retreat at Tutka Bay. What I learned from him there about the relationship of content and language changed the way I approached my own work. A clear voice emerged from the novel I'd been attempting, and with that, the book, Cold Spell found its legs. Here, a few notes from Vann's lecture on language, focusing on a selection by Annie Proulx, who’ll be the keynote speaker at the 2014 AWP Conference in Seattle.

Listing is a great way to compress content; an epic convention (from Greek and Roman) – compresses content, collapses time. Also doesn’t fill in time. Sentence fragments. You can divide the English language into grammar and content. Morphemes not the same as words – they are the building blocks. Grammatical parts organize; content parts are what Proulx (opening pages of The Shipping News ) leaves in – nouns, adjectives, and active verbs. She converts verbs to adjectives. Using words as other than their normal parts of speech: this makes language fresh. Becomes foregrounded – readers tend to be automatons. Cliches are bad b/c we get only the literal meaning. Poor writers – readers can just skim. As soon as something’s outside of its usual position – you’re required to pause. Style is choice. There are different ways to present something: the kinds of sentences, whether things are foregrounded and not in their usual spots. Style is the combination of choices – syntax, phonology, lexicon; voice is the combination of that and the sensibility (attitude toward the world) – voice is bigger.Basic distinctions of style: language divides into Anglo-Saxon (Germanic) and Latinate lexicon and meter. Each has its own vocabulary and metrical properties. 1066 is the most important date in English literature. Latinate meter in Aeniad is accentual syllabic (dactile: heavy stress, two soft stresses). Metrical line arranged by the kind of metrical pattern in each foot plus the number of syllables. Everything declined and marked. Sentence order didn’t matter – much more flexible than Germanic, which had only accentual meter: two heavy stresses and then two more (number of syllables doesn’t matter). Poets can use either paired heavy stresses (accentual meter) or iambic pentameter (Latin) to satisfy readers.Chaucer – first to write verse in Middle English instead of Latin or French. Class divide in our language: German is low; refined is French (example: cow v. beef). Instinctive class divide can be used for jokes: Latinate sentence with crude German word thrown in for fun. (Ex: mad libs – swaps content with grammar; not fun to switch out grammar). Grammar is our glue and we can’t process if grammar is switched. Double heritage: high/low vocab; double metric schemes. Language use – simplify distinctions; tough words go away. Hymns forced full ideas into single lines – destroyed language over time. English made difficult sounds vanish; French – we’ve shortened sounds. Chaucer’s initial lines: Latin meter. Over time, lost vowels, lost aspirations. Language deteriorates, but English is still the beefiest.Annie Proulx is one of our best stylists. She matches style to content. In first two pages, she heaps up content, cuts out grammar. Favoring content over grammar, favoring Germanic over Latinate. These two pages are among David’s favorite in contemporary writing. Emphasis and foregrounding in last sentence on page 3, providing a snapshot of the rest of the book – theme. Points of emphasis are about the meaning of the book and the character. Similar moment to Faulkner: this sentence tells us how to read the rest of the book; it will work through the landscape. The book is a love story. The sludge could be his thoughts, but it could also be his heart. We get some sympathy for Quoyle. We can’t reduce it to a one-to-one correspondence. Syntactic departure – David’s theory is that the beautiful is not just in content, but it’s created by syntax. There are road signs to beauty. For a study of voice and its impact on writing, I'll be teaching a four-week workshop “Sound and Fury: Find and Free Your Writer’s Voice,” in Anchorage beginning Oct. 17.

Published on September 24, 2013 08:44

September 17, 2013

Where We Write

In the inaugural essay of the new “Where We Write” feature in Poets and Writers Magazine, Francine J. Harris wrote about Detroit, an urban setting that could not be more different than the place where I write. Still, her observations on regionalism, integration, and forgetfulness helped me think in fresh ways about Alaska, where I write.

Fresh out of a Midwestern college, I boarded a series of planes, each smaller than the last, until a single-engine Cessna dropped me on a muddy runway in the middle of the Alaska tundra. I saw no houses, no roads, no school where I’d planned to teach, only wind-rippled grasses and a brown, winding slough. The wind stinging my face, the plane droning into the gray sky as it circled and then disappeared, I couldn’t fathom then what a place like that might mean or, within it, who I might become.

Thirty-four years later, I’m still exploring those questions in my writing. Happily, I have company, in the form of what Oprah Magazine book editor Leigh Newman has dubbed an Alaska Literary Renaissance. In the sixteen years since I began publishing, first out of New York, later with regional presses, our once-marginalized Alaska literary community is growing into a sense of itself.

Breeding misconceptions even as it inspires, this place where we write is iconic—wild, vast, and in many ways unfamiliar, even to those of us who live here. To write within such a place requires resisting stereotypes and the rehashing of familiar themes. Geographically, culturally, and socially, we have many Alaskas to explore. Beyond the familiar “man versus wild,” there are multiple tensions to consider, too—outsiders and insiders, colonial intrusion and aboriginal integrity, preservation and development, community and isolation.

I’m fortunate to have been writing and publishing here for a long time. I’ve lived in places few can pronounce, much less imagine— Nunapitchuk, Tuluksak, Akiachak—places that in many ways seem a world apart, and yet beyond the windswept tundra and the bitter wind and the collision of cultures run hopes and heartaches that inspire stories everywhere. On any given day, I may look up from my laptop and through the window spot a moose with her calf, a black bear sneaking across the yard, or a late winter sunrise cast a pink light over Mt. McKinley.

Where do you write?

Published on September 17, 2013 08:00

September 10, 2013

Authors, Booksellers, Readers: You're invited (by none other than Sherman Alexie)

Sherman Alexie

Sherman AlexieIn a letter signed "Sherman Alexie, An Absolutely True Part-Time Indie," one of America's best-known authors had launched a great concept, declaring November 30 "Indies First" day at local bookstores all over the country.

Addressing all "book nerds," Alexie makes his pitch: "Now is the time to be a superhero for independent bookstores. I want all of us (you and you and especially you) to spend an amazing day hand-selling books at your local independent bookstore on Small Business Saturday (that's the Saturday after Thanksgiving, November 30 this year, so you know it's a huge weekend for everyone who, you know, wants to make a living)."

"Here's the plan," Alexie explains. "We book nerds will become booksellers. We will make recommendations. We will practice nepotism and urge readers to buy multiple copies of our friends' books. Maybe you'll sign and sell books of your own in the process. I think the collective results could be mind-boggling (maybe even world-changing)."

The "Indies First" idea grew from an invitation extended to Alexie by Janis Segress when she and others re-opened Seattle's Queen Anne Book Company last spring. Alexie accepted. After all, he says, "What could be better than spending a day hanging out in your favorite hometown indie, hand-selling books you love to people who will love them too and signing a stack of your own?"

I love this idea. It plays right into one of my secret but (usually) suppressed urges: to tug the sleeves of strangers whenever I spot titles I love on the shelves of a bookstore. I'm spreading the word well in advance because booksellers need to sign up (only two to date in Alaska - what's up with that?) and so do authors.

Authors, booksellers, readers - you're all invited. Mark your calendars, sign up, and let's get out and sell books!

Published on September 10, 2013 08:00

September 3, 2013

Tour a book before it’s published? Five reasons why it’s not as crazy as it sounds

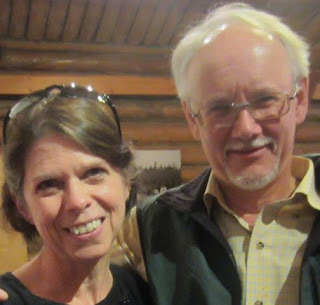

In Whitehorse: That's me with Michael Gates, one of my favorite writer/historians

In Whitehorse: That's me with Michael Gates, one of my favorite writer/historiansRecently I returned from ten days of traveling Alaska and the Yukon, touring a book that’s yet to be published. A year ago, I’d never thought of doing such a thing, but now that I’ve done it, it makes perfect sense.

Of course, it has to be the right kind of book. I wouldn’t do a pre-publication tour of a novel, for instance, because novels are slippery little things, prone to a lot of shifting even in their final stages.

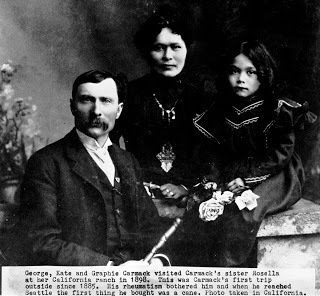

You also have to be the right kind of author, meaning that you have the confidence and means to make sure the book actually gets published. Because my publishing options now include Running Fox Books, I’ve got an in with the publisher (me!), and that means I know Wealth Woman: Kate Carmack and the Last Great Race for Gold will see the light of day, one way or the other.

Finally, you have to be at the right place in your work. I’ve been at this project for two years. My research is nearly wrapped up (I completed the last of it while touring, which helped me decide where to stop.). I’ve written half the book, and the other half’s thoroughly outlined. Put it this way: I can talk about Kate Carmack in my sleep. All night. For several nights in a row. If there’s anyone in the world who knows more about her than I do, we definitely need to talk.

Here’s why I recommend a before-the-fact tour of your book:

· You’ll be reminded why you’re writing the book in the first place. After a few years on a project, you start wondering why you ever began. A few talks in new places before eager listeners will get you jazzed all over again about your subject.· You’ll get to test-drive some of the book’s key components. Before a live audience, you can see where interest peaks and fizzles. You’ll find out which parts you’ve nailed, and which ones will benefit from further work.· You’ll build excitement for your project. If you’ve ever waiting nervously for those first reviews to come in, wondering whether anyone but you and your mother and your friends who are too polite to say otherwise will like what you’ve written, then you can appreciate how nice it is to meet a bunch of readers who are enthusiastic about your book before it’s even finished.· You’ll expand your platform. Is any phrase tossed around more in publishing these days? Enough said.· You’ll meet some really cool people. In Haines, I stayed with Nancy, in the very same house owned by Louis Shotridge almost a hundred years ago (as it happens, Louis Shotridge appears in my book. Thanks to my friend Dan, I also met Lee, a local genealogy whiz who helped me firm up some family connections of Kate’s. In Skagway, I reconnected with Cindy at the National Park Service, who set my whole tour in motion with a lecture request made last spring. In Tagish, I was welcomed by Ida, a descendent of Kate’s who shared fantastic views (literally and figuratively) of the place Kate called home. In Whitehorse, a stranger I met at the archives became a friend, inviting me to stay at her home, where we swapped research on our subjects (thanks, Lian!), and a fellow writer delivered some research material I hadn't yet found (thanks, Michael!). In Dawson, Laura served wine and cheese at my lecture, and she made email connections for me with writers I need to know, plus I got a rare tour of the Anglican Church that Kate’s daughter attended (thanks, Dan and Betty!).

Cross-posted at www.49writers.blogspot.com.

Published on September 03, 2013 08:00

August 27, 2013

Do you need a literary agent?

Of the twelve books I’ve published through traditional channels, none has been placed with the help of an agent. That doesn’t mean I’m opposed to working with agents, nor that I’d not want to work with one at some point in the future. In fact, for nine years I worked as an agent myself—a real estate agent, that is, because the average writer’s royalties don’t do much toward helping her children through college.

A book is not a house, but by working as an agent, I did learn quite a lot about the value of a third party in important transactions. In most cases, I still advise buyers and sellers that they’ll come out ahead if they work with an agent who knows the business.

In the end, it’s an individual decision—whether to seek representation or go it alone, which in the book business could mean either placing your manuscript directly with an editor or bringing it directly to readers. Here are seven things to consider when you’re contemplating a literary agent:

· Your project: Can you convince an agent that your book has real breakout potential? It used to be that agents would sign authors with the idea of developing them over the long haul. But in today’s market, the place of the midlist author is becoming more and more precarious. That’s why you hear so much about platforms—agents prefer authors who bring their own readers. If your project’s worthy but not destined to be a chart-busting success, you might be better off publishing independently, or with a small press where you can submit directly to the acquiring editor. The genre matters, too. In children’s books, for instance, many editors (even at big houses) will consider unagented manuscripts, while in other genres, that’s almost unheard of.· Your ambitions: Will you still feel like a writer if you don’t have a literary agent? When others are talking about their agents (complaining about them even), will you feel left out? While this may seem trivial, the gravitas that comes with having an agent may signify to you that you’re part of the game. And if only a big New York house will do for your book, you’ll likely need an agent to place it there. · Your connections: Agents are middlemen. They network. Ironically, it’s the writer who’s been in publishing awhile, someone who has established a few industry relationships on her own, who may be most able to navigate without a literary agent.· Your skills: Agents know contracts. They’re negotiators. They see the big picture. Many are fine editors, and can help authors fine-tune their manuscripts. Yes, you can hire out some of those services, but in the end, it may be a lot more efficient to work with one person who can do it all, someone who has a vested interest in your success, since commissions are dependent on sales.· Your expectations: As in any profession, there are good agents and bad agents. There are no licensing requirements for literary agents, so if you pursue one, make sure that person is well-affiliated and well-recommended. Keep in mind, too, that whether you acknowledge it openly or not, one of the reasons you’re drawn to an agency relationship is that you simply want someone to believe in you and your work. The reality, though, is that agents are very busy, and you may get little personal attention. And despite her best efforts, there’s no guarantee that an agent will place your manuscript. On the other hand, if you’re eager to see your book on the shelves in France or on the big screen, you’ll need an agent, as foreign and film rights are notoriously difficult to sell.· Your options: By signing with a particular agent, are you narrowing your options strictly to the traditional publishing path—a path that’s becoming increasingly narrow and difficult to navigate? Or is yours one of the forward-thinking agents whose services include helping independent authors get noticed? Once you enter into an agency relationship, you’ll have certain legal and ethical commitments to that agent. Yes, agents and clients “break up” all the time, but the understanding is that as the agent invests in your career, you’ll be loyal to your agent.· Your patience: Good agents have lots of clients. Out of hundreds (if not thousands) of queries a year, they can often take on only a handful of new authors. Much as they may like you and your project, the numbers aren’t in your favor. Do you have the time and patience to keep shopping for an agent in an increasingly tight market?

Published on August 27, 2013 08:00

August 20, 2013

Writing a book you love

Having published a dozen books, I’ll let you in on a little secret: I don’t love them all equally.

Don’t get me wrong. I worked hard on each of my books, and I’m not ashamed of any of them. But some are real labors of love, including a book I’m touring this week—a book I’m not yet finished writing.

I know it’s odd to tour a book that’s not finished. After all, the point of a book tour is to sell books, and you can’t sell a half-finished book. (Or can you? Dickens did.) But when the National Park Service asked me to do a program on Kate Carmack, the subject of my forthcoming book Wealth Woman, I scheduled the program into a final research trip, lining up presentations at several museums along the way.

I’ll get a few comped travel expenses. I’ll sell a few copies of titles that are already in print. But mostly, the reward for this particular journey—and for this book—is setting Kate’s story straight. It’s been a long time coming.

Kate Carmack, first called Shaaw Tláa, was once known as the richest Indian woman in America. She claimed to have made the discovery of a lifetime, Klondike gold. But when she’s mentioned at all in writing about the Klondike, it’s as a difficult woman, a drunkard who gave her husband nothing but trouble. “After reading about her, who could blame a man for shedding her!” wrote an editor to George Carmack’s biographer.

As it turns out, nothing could be further than the truth. Though cheated out of her wealth, Kate defied convention and proved that defeat need not follow loss. The more I learned of her, the more passionate I became about her story, and the more I knew it had to be told.

The more I learned, the more I also realized the overwhelming extent to which the prevailing Klondike narratives glorify individualism and colonialism. As it turns out, Wealth Woman: Kate Carmack and the Last Great Race for Gold will be the first authentic rendering of the gold rush from the perspective of those who were there first, the Natives of Alaska and the First Nations of Canada.

My passion for Kate’s story comes from thirty-four years of living and traveling in Alaska and the Yukon, including villages where I was the outsider. I want silenced voices to be heard. I want fresh perspectives on familiar history. Though not yet fully birthed as a book, Kate’s is already a story I love.

You can read a chapter from Wealth Woman in draft here.

Published on August 20, 2013 08:00

August 13, 2013

Dead fish, free books

Forget those back-to-school sales. Summer’s not over yet. In Alaska, the silvers are running, and so is the Ode to a Dead Salmon bad writing contest, sponsored by Running Fox Books.

Judges Ned Rozell and Howard Weaver have narrowed the stinky field to three finalists, displayed here. Now it’s up to the public to choose the best of the worst. So don’t delay—click over to the Ode to a Dead Salmon site and hold your nose as you choose. Voting ends Monday, Aug. 19, with the winner to be announced on Thursday, Aug. 22.

As a special thanks for your vote—and to anyone else who sees this post—Running Fox author Deb Vanasse is offering the Kindle edition of her novel Out of the Wilderness free on Friday, Aug. 16 and Saturday, Aug. 17. Mark your calendars, tell your friends, and reward yourself with a free book!

Published on August 13, 2013 08:00

August 6, 2013

Publishers: Is it wrong to jump ship?

When I write about independent publishing and hybrid authors (those who publish both traditionally and independently), I’m routinely asked about whether it’s fundamentally wrong for an author to strike out on her own after being published by someone else.

In one sense, these questions are heartening. Relationships matter. We should respect those we work with. But they also point to a huge disconnect between what writers think goes on in traditional publishing and what actually happens.

Let me say first off that no author’s experience in publishing is exactly like anyone else’s. With that in mind, here’s my perspective on the ethics of jumping ship:

After a publisher commits resources to publishing your book, isn’t it wrong to publish your next book somewhere else, or to publish it yourself? With the exception of a few big-name authors, publishers aren’t courting writers, and they’re not looking to marry. They’re selling books, title by title. Their investment is in a particular title at a particular time for a particular market. It’s a calculated risk. If your publisher wants first option on your next book, they’ll include an option clause in your book contract.But it’s hard to get a contract with a publisher. Once you’ve got one, shouldn’t you do everything you can to get another one with the same publisher? Not necessarily. Each book deserves the best home you can find for it, and these days there are more options than ever. Sometimes that will be with the publisher who published your last book. Sometimes it will be with a different publisher. Sometimes a book is best served by you bringing it directly to readers.I thought publishing was about relationships. Once you’re working with people who believe in you, shouldn’t you stick with them? Decades ago, it was common for agents and editors to identify and mentor writers with promise, nurturing them from one book to the next. Those relationships tended to be exclusive. These days, it’s a rare and beautiful thing to find someone in the industry who has the time, energy, and freedom to develop a long-term relationship with an author. Unless you’re able to bat book after book out of the park in terms of sales, market forces require most industry professionals to turn their attention to the next author and book with hit potential.When you publish independently, aren’t you competing with the traditional publishers you worked with in the past? Not if the book’s not right for that publisher. In fact, the reverse is true: Your previous publishers will benefit from the marketing and branding you do when you promote books you’ve published on your own—and frankly, you will do more of it for those books because your return in sales is so much higher than for traditionally published books. As more and more readers discover your writing, sales of all your titles increase—and those previous publishers had to risk nothing to achieve it. That’s a win-win for everyone.

Published on August 06, 2013 08:00

Book Birthday!

Happy Birthday to my latest book, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/5...! Thanks to West Margin Press for bringing it into the world and to authors C.B Bernard, Bill Streever, Gary Krist, Caroline V

Happy Birthday to my latest book, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/5...! Thanks to West Margin Press for bringing it into the world and to authors C.B Bernard, Bill Streever, Gary Krist, Caroline Van Hemert, and Kim Heacox for their endorsements!

...more

- Deb Vanasse's profile

- 39 followers