Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 87

October 26, 2012

A Crash Course in Stoicism

In his discourse entitled “we ought not to yearn for things that are not under our control” (Discourses, 3.24), the Stoic philosopher Epictetus, described three steps used to cope with apparent misfortunes. He intended that these should be rigorously rehearsed until they become habitual…

In his discourse entitled “we ought not to yearn for things that are not under our control” (Discourses, 3.24), the Stoic philosopher Epictetus, described three steps used to cope with apparent misfortunes. He intended that these should be rigorously rehearsed until they become habitual…

Have thoughts like these ready at hand by night and by day; write them, read them, make your conversation about them, communing with yourself, or saying to another, “Can you give me some help in this matter?”

Later he says:

If you have these thoughts always at hand and go over them again and again in your own mind, and keep them in readiness, you will never need another person to console you, or strengthen you.

Speaking to a group of aspiring Stoic students, he outlines the recommended steps to be memorised and rehearsed as follows.

Step One: Tell yourself it was to be expected.

Your initial response when something apparently “undesirable” happens should be to tell yourself that it was “not unexpected”, and this “will be the first thing to lighten the burden”, according to Epictetus. This is made easier by regularly anticipating potential setbacks that can happen in life, imagining what it would be like to face typical misfortunes philosophically. This is sometimes called premeditatio malorum by Stoics, or the technique of contemplating potential misfortunes in advance. In particular, the Stoics frequently remind themselves that both they and their loved ones are mortal, and bound to die one day, and that life is inevitably transient. Here Epictetus simply says, however, that when adversity comes we should greet it by reminding ourselves not to be surprised but to recognise that we knew all along that this sort of thing can potentially happen in life.

Step Two: Tell yourself that it is indifferent to your wellbeing.

This is sometimes described as the “Sovereign precept” of ancient Stoicism: Some things are under our control and some things are not. Only things under our control reflect on our character and therefore constitute our wellbeing, i.e., our judgements and acts of will are our own business and when they are done well we may be described as being wise and good. Things outside of our control, such as health, wealth and reputation are indifferent with regard to our own character and therefore our happiness and wellbeing. Epictetus says you should consider where the misfortune comes from, and if it is an external event, tell yourself:

It comes from the quarter of the things that are outside the sphere of volition, that are not my own; what, then, is it to me?

The typical answer Stoics give to that rhetorical question is: “It is nothing to me.” In fact, one of Epictetus’ basic maxims is that things beyond our volition, outside of our control, are “nothing to us.” For Stoics, the ultimate good in life is to possess wisdom, justice, and other virtues, and to act according to them. The vicissitudes of fate, external events, the wheel of fortune that sometimes raises us up and at other times casts us down, is “indifferent” with regard to our own character and virtue and, in that sense, of no concern with regard to our true wellbeing as rational agents.

Step Three: Remind yourself that it was determined by the whole.

Epictetus describes the third and last stage of the Stoics response as “the most decisive consideration”. We should ask ourselves who has ordained that this should happen: “Who was it that has sent the order?” The answer is that it was sent by God, or, if you like, it should be viewed as having been determined by the “string of causes” that constitute the universe as a whole, which Stoics call “Nature”. The Stoic therefore tells himself: “Give it to me, then, for I must always obey the law in every particular.” In other words, he sees events outside of his control as necessary, determined by the whole of Nature, or fated by the Will of God, and he actively accepts them as such. This may simply be another way of stating the importance that philosophical “determinism” has for Stoics, the belief that all things happen of necessity and are caused by the totality of the universe. When we tell ourselves that events come as no surprise, that they lie outside the domain of our concern, and that they could not have been otherwise, and form part of the unfolding pattern of universal Nature, we may achieve the wisdom and serenity in the face of adversity that Stoics aspire to, and call a “smooth flow of life.”

Filed under: Stoicism Tagged: Epictetus, philosophy, stoic, stoicism

October 24, 2012

Epictetus on Natural or Family Affection

This is a story recorded in the Discourses of Epictetus, in the chapter on philostorgia, meaning “natural affection” or “family affection” (Discourses, 1.11). A magistrate came to see Epictetus one day and mentioned that his experience of married life had been miserable. Epictetus replied that we marry and have children to flourish and be happy (eudaimon) rather than to be miserable, and so he was curious what had gone wrong. The man said that recently when his young daughter was dangerously ill, he found it so unbearable that he ran from her bedside in distress, only to return when someone brought word that she had recovered. He also said he believed being overwhelmed with distress was a natural response and that this was the right thing to do because “this is the way most fathers would feel” if their beloved child were dying. Epictetus maintained the Stoic view that what is done according to nature is right but he questioned whether this man’s response was genuinely the most natural one, despite the fact that it might be what most fathers, in that period, would feel like doing. Epictetus notes that although to err is common, and that physical tumours are common, we don’t assume that these occur for our own good or that they’re what our natures intended. Being common and being natural are two different things. When Epictetus then asks the man what criterion he would use to determine whether some action is natural and rightly done, or not, he says he has no idea. Epictetus sees this lack of a criterion for the good, for what is natural, as the greatest harm that can befall someone, and he therefore beseeches the magistrate to discover this criterion and to then use it to decide each individual case that confronts him in life.

This is a story recorded in the Discourses of Epictetus, in the chapter on philostorgia, meaning “natural affection” or “family affection” (Discourses, 1.11). A magistrate came to see Epictetus one day and mentioned that his experience of married life had been miserable. Epictetus replied that we marry and have children to flourish and be happy (eudaimon) rather than to be miserable, and so he was curious what had gone wrong. The man said that recently when his young daughter was dangerously ill, he found it so unbearable that he ran from her bedside in distress, only to return when someone brought word that she had recovered. He also said he believed being overwhelmed with distress was a natural response and that this was the right thing to do because “this is the way most fathers would feel” if their beloved child were dying. Epictetus maintained the Stoic view that what is done according to nature is right but he questioned whether this man’s response was genuinely the most natural one, despite the fact that it might be what most fathers, in that period, would feel like doing. Epictetus notes that although to err is common, and that physical tumours are common, we don’t assume that these occur for our own good or that they’re what our natures intended. Being common and being natural are two different things. When Epictetus then asks the man what criterion he would use to determine whether some action is natural and rightly done, or not, he says he has no idea. Epictetus sees this lack of a criterion for the good, for what is natural, as the greatest harm that can befall someone, and he therefore beseeches the magistrate to discover this criterion and to then use it to decide each individual case that confronts him in life.

However, in the meantime, Epictetus gave him the following advice about the case of his child. He first asks whether family affection (philostorgia) seems to the magistrate both to accord with nature and to be good or noble, which it does, without question. This is a premise they can both agree upon for the time being: that family affection is both natural and morally good. Epictetus also established that he takes for granted the view that what is rational with regard to life is good. He adds that if both family affection and living rationally are genuinely morally good then they should not contradict each other. Moreover, if they were in conflict, at least one of them would have to be unnatural but living rationally and loving one’s family are both assumed to be natural by the magistrate. Family affection and living rationally are therefore both agreed to be morally good and consistent with each other. However, the magistrate admits that fleeing his child’s bedside is not rational, although he feels it may have been an expression of his love and affection for her.

Epictetus invokes what modern cognitive therapists call the “double-standards” strategy by asking the magistrate whether he would consider it loving and affectionate of others, such as the child’s mother or nurse, to act as he had done and flee her bedside. Would it make sense to say that those who love his daughter the most should, because of their great love for her, leave her potentially to die in the arms of others who do not love her as much? Likewise, the magistrate admits that if he had been dying himself, he would not want those who love him the most, including his wife and children, to express their affection by running from his bedside and abandoning him to die alone. Epictetus points out that if this is how love manifests itself, it would make more sense to wish that one’s enemies loved one more than one’s friends, and that they would keep their distance as a result. This is what philosophers call a reductio ad absurdum, the favoured debating technique of Socrates, in which careful questioning leads an individual to recognise that their position is inherently contradictory and nonsensical. It leads to the revised conclusion that the magistrate’s flight from his daughter’s bedside was not really an act of love or family affection at all but rather something else. The act of running away was a form of avoidance, like covering your eyes, and the result of a fundamental decision to concludethat escape is preferable to endurance of the painful situation. As Epictetus put it, “the cause of your running away was just that you wanted to do so; and another time, if you stay with her, it will be because you wanted to stay.” It is not external events that cause our actions but our own opinions and decisions, otherwise everyone would respond in the same way to the same events. Therefore, Epictetus concludes, the magistrate should attribute his actions not to external events, like the illness of his child, which are outside his direct control, but rather to his own voluntary decisions, and that it should become his priority in life to study these closely and patiently and determine whether they are natural and morally good or not.

Filed under: Stoicism Tagged: affection, love, stoic, stoicism

October 18, 2012

The System of Stoic Philosophy

Copyright (c) Donald Robertson, 2012. All rights reserved.

This article attempts to summarise some of the structured elements of the early Stoic philosophical system, such as the tripartite classification of the topics of philosophy, the virtues, the passions, and their subdivisions, etc., as reputedly described by the primary sources. It’s still a work in progress, see please feel free to post comments or corrections.

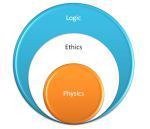

The Parts of Philosophy

From Diogenes Laertius (7.38-41)

Zeno introduced the tripartite division of philosophy in his book On Rational Discourse. Whereas some Stoics say the three parts of philosophy are mixed and taught together, Zeno, Chrysippus, and others, put them in the following order:

Logic

Physics

Ethics

However, Plutarch says that Chrysippus thought the parts should be studied as follows (Early Stoics, p. 9):

Logic

Ethics

Physics (and theology)

Cleanthes divided philosophy into six parts, however.

Dialectic

Rhetoric

Ethics

Politics

Physics

Theology

Several metaphors are used in conjunction with this tripartite division of philosophy. For example, philosophy is like an animal:

Logic = The bones and sinews

Ethics = The fleshier parts

Physics = The soul

Philosophy is like an egg:

Logic = The shell

Ethics = The egg white

Physics = The yolk

Philosophy is like a productive field:

Logic = The surrounding wall

Ethics = The fruit

Physics = The land and trees

Philosophy is like a city “which is beautifully fortified and administered according to reason.” According to Sextus Empiricus, Posidonius compared philosophy to an animal, as follows (Early Stoics, p. 9):

Physics = The flesh and blood

Logic = The bones and sinews

Ethics = The soul

Ethics & The Virtues

From Diogenes Laertius (7.84-131).

The early Stoics define “the good” as encompassing three senses:

The most fundamental sense is that through which it is possible to be benefitted, which corresponds mainly to the virtues

In addition, the good includes that according to which being benefitted is a typical result, which refers both to the virtues and to specific virtuous actions

Finally, the good includes that which is such as to benefit, namely the Wise man himself, true friends, and the gods, who engage in virtuous actions and possess the virtues

From another point of view, the good is described as being both beneficial (healthy?) and honourable or praiseworthy.

Although Zeno and Cleanthes did not divide things in such detail, the followers of Chrysippus and others Stoics classify the sub-divisions of ethics as follows:

On impulse

On good and bad things

On passions

On virtue

On the goal

On primary value

On actions

On appropriate actions

On encouragements and discouragements to action

Diogenes Laertius says that whereas Panaetius divided virtues into two kinds (theoretical and practical), other Stoics divided the virtues into logical, ethical and physical. According to Aetius also, there are three categories of virtue, which correspond with the three divisions of philosophy: physics, ethics, and logic (Early Stoics, p. 9). He doesn’t say what these virtues are, but we might speculate:

Physics = Self-Control (Courage & Moderation, two of the cardinal virtues)

Ethics = Justice

Logics = Wisdom (or Prudence)

Most Stoics appear to have agreed that there are four “primary” virtues, common to other ancient schools of philosophy:

Prudence or Practical Wisdom (Phronesis), sometimes just called Wisdom (Sophia), which opposes the vice of “ignorance”

Justice or Integrity (Dikaiosune), which opposes the vice of “injustice”

Fortitude or Courage (Andreia), which opposes the vice of “cowardice”

Temperance or Moderation (Sophrosune), which opposes the vice of “wantonness”

These are defined as forms of knowledge (q.v., Stobaeus in Early Stoics, p. 125-130):

Prudence is knowledge of which things are good, bad, and neither; or “appropriate acts”.

Temperance is knowledge of which things are to be chosen, avoided, and neither; or stable “human impulses”.

Justice is the knowledge of the distribution of proper value to each person; or fair “distributions”.

Courage is knowledge of what is terrible, what is not terrible, and what is neither; or “standing firm”.

The cardinal virtues are also sub-divided as follows:

Prudence takes the form of deliberative excellence, good calculation, quick-wittedness, good sense, good sense of purpose, and resourcefulness.

Temperance takes the form of organisation, orderliness, modesty, and self-control.

Justice takes the form of piety, good-heartedness, public spiritedness, and fair dealing.

Courage takes the form of endurance, confidence, great-heartedness, stout-heartedness, and love of work.

A famous slogan of Epictetus is usually translated as “bear and forbear” or “endure and renounce”. This can perhaps be seen to correlate with the two virtues relating to self-control in the broad sense: courage and temperance. It’s possible that these two complementary virtues both correspond somehow with the discipline of Stoic physics and with the passions, as follows:

Endure (bear), through the virtue of courage, whatever irrational pain or suffering would normally be feared and avoided

Renounce (forbear), through the virtue of temperance (or moderation), whatever irrational pleasures would normally be desired and pursued

According to Chrysippus and other Stoics, the main examples of indifferent things, being neither good nor bad, are listed as pairs of opposites (Diogenes Laertius, 7.102):

Life and death

Health and disease

Pleasure and pain

Beauty and ugliness

Strength and weakness

Wealth and poverty

Good reputation and bad reputation

Noble birth and low birth

…and other such things.

The Passions

According to Zeno, the passions are to be defined as judgements or movements of the soul, which are (Diogenes Laertius, 7.109):

Irrational,

Unnatural, or,

Excessive

According to Zeno, the most general division of these irrational passions is into four categories:

Pain (or suffering)

Fear

Desire

Pleasure

These can be subdivided as follows (following Diogenes Laertius but also Stobaeus, in Early Stoics, pp. 138-139:

Pain is an “irrational contraction” of the soul and can take the form of pity, grudging, envy, resentment, heavyheartedness, congestion, sorrow, anguish, or confusion. Or according to Stobaeus, envy, grudging, resentment, pity, grief, heavyheartedness, distress, sorrow, anguish, and vexation.

Fear is the “expectation of something bad” and can take the form of dread, hesitation, shame, shock, panic, or agony. Or according to Stobaeus, hesitation, agony, shock, shame, panic, superstition, fright, and dread.

Desire is an “irrational striving” and can take the form of want, hatred, quarrelsomeness, anger, sexual love, wrath, or spiritedness. Or according to Stobaeus, anger (e.g., spiritedness, irascibility, wrath, rancor, bitterness, etc.), vehement sexual desire, longings and yearnings, love of pleasure, love of wealth, love of reputation, etc.

Pleasure is an “irrational elation over what seems to be worth choosing” and can take the form of enchantment, mean-spirited satisfaction, enjoyment, or rapture. Or according to Stobaeus, mean-spirited satisfaction, contentment, charms, etc.

In addition to the irrational, excessive or unnatural (unhealthy) passions, there are also corresponding “good passions”. These fall into three categories, because no good state corresponds with emotional pain (suffering) or contraction of the soul (Diogenes Laertius, 7.116).

Joy or delight (chara), a rational elation, which is the alternative to irrational pleasure

Caution or discretion (eulabeia), a rational avoidance, which is the alternative to irrational fear

Wishing or willing (boulêsis), a rational striving, which is the alternative to irrational desire

These good passions can be subdivided as follows:

Joy can take the form of enjoyment/delight (terpsis), good spirits/cheer (euphrosunos), or tranquility/contentment (euthumia)

Caution can take the form of respect/restraint/honour (aidô) or sanctity/purity/chastity (agneia)

Wishing can take the form of goodwill/favour (eunoia), kindness (eumeneios), acceptance/welcoming (aspasmos) or contentment/affection (agapêsis)

In other words, a distinction can be made between rational and irrational passions as follows:

Elation (eparsis) can take the form of rational joy (chara) or irrational pleasure (hêdonê)

The impulse to avoid something (ekklisis) can take the form of rational discretion (eulabeia) or irrational fear (phobos)

The impulse to get something (orexis) can take the form of rational willing (boulêsis) or irrational craving (epithumia)

There is no rational form of pain or suffering (lupê), in the Stoic sense

The good passion of caution (or discretion) appears to particularly resemble the virtue of temperance. The good passion of wishing (or willing) appears to mainly encompass love (agapêsis), and related affects, such as goodwill, kindness, acceptance and affection. This is the rational alternative to anger and sexual lust, or irrational desire.

Filed under: Stoicism Tagged: philosophy, stoic, stoicism

October 10, 2012

Were Hand Gestures a Technique of Stoicism?

Were they a psychological technique?

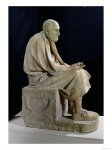

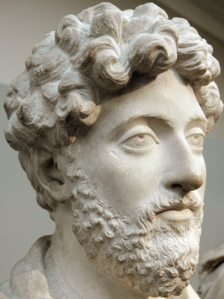

Chrysippus Gesturing

Copyright (c) Donald Robertson, 2012. All rights reserved.

[This is still a draft, using material I'm researching for my next book, so please feel free to comment or raise questions, and I may revise the content accordingly.]

The early Stoics reputedly said that “knowledge is the leading part of the soul in a certain state, just as the hand in a certain state is a fist” (Sextus in Inwood & Gerson, 2008, The Stoic Reader, p. 27). This analogy between secure knowledge, having a firm grasp on an idea, and the physical act of clenching the fist seems to be a recurring theme in Stoic literature.

And Zeno used to make this point by using a gesture. When he held out his hand with open fingers, he would say, “This is what a presentation is like.” Then when he had closed his fingers a bit, he said, “Assent is like this.” And when he had compressed it completely and made a fist, he said that this was grasping (and on the basis o f this comparison he even gave it the name ‘katalepsis’ [grasp], which had not previously existed). But when he put his left hand over it and compressed it tightly and powerfully, he said that knowledge was this sort of thing and that no one except the wise man possessed it. (Cicero in Inwood & Gerson, 2008, p. 47)

The sculpture of Chrysippus in the picture above, from the 3rd century BC, shows him holding his hand out with open fingers, in a similar posture. So we have a series of four hand gestures:

The hand is held open, at a distance, with palm upwards, to symbolise a superficial impression or “presentation”.

The hand is closed loosely, to symbolise initial “assent” or agreement with the idea.

The hand is squeezed tightly into a fist to symbolise a firm grasp (katalepsis) or sense of certainty.

The fist is enclosed tightly in the other hand, to symbolise the perfect “knowledge” of true ideas attained by the ideal Sage, which is elsewhere described as an interconnection of firmly-grasped principles and ideas, forming the excellent character of the wise.

Marcus Aurelius refers to clenching the fist as thought it symbolises the act of the Stoic student in arming himself with his philosophical precepts.

The student as boxer, not fencer. The fencer’s weapon is picked up and put down again. The boxer’s is part of him. All he has to do is clench his fist. (Meditations, 12.9)

For the Stoics it was important to memorise the precepts and integrate them completely with one’s character in order to have them always “ready-to-hand” in the face of adversity. It’s possible that the physical act of literally clenching the fist, like a boxer, was used as a mnemonic to recall principles required in difficult situations.

It’s possible perhaps to construct a modern Stoic psychological exercise out of this symbolic set of hand gestures. While repeating a precept of Stoicism (“the only good is moral good”, “pain is not an evil”) the Stoic student might initially hold his hand open as if toying with the idea and then progressively close it more tightly, while imagining accepting it more deeply, until he finally clenches his fist tightly to symbolise having a firm grasp of the idea, and closes his other hand around it, to symbolise integrating it more deeply with his character. This might be compared to the use of “autosuggestions” or rehearsing “rational coping statements” in modern psychological therapies.

There may also be an additional use, in relation to false or irrational ideas. In the Enchiridion, Epictetus says that the first thing a Stoic should do when encountering a harsh (problematic) impression is to remind himself that it is merely an impression and not at all the thing it claims to represent. This sounds very much like an important psychological strategy used in modern CBT and behaviour therapy, called “cognitive distancing” or “defusion”. As it happens, Cicero says that the hand gesture demonstrated in the sculpture of Chrysippus above was used by Zeno and other Stoics to symbolise entertaining an idea, such as an “automatic negative thought”, in the form of a superficial “presentation” or impression. Hence, a modern Stoic might make the same gesture when he notices an unhelpful or irrational thought occurring spontaneously, and entertain it a while longer, as if holding it loosely in an open hand, at a distance, while repeating “This is just an automatic thought, and not at all the thing it claims to represent” or “This is just a thought, not a fact”, etc.

We don’t know whether the set of symbolic hand gestures described by Zeno was meant originally as a psychological technique of this kind. However, the quote from Marcus Aurelius above could perhaps be read, if taken very literally, as a description of an actual physical practice employed by Stoic students: clenching their fists to arm themselves, like a boxer, with their philosophical precepts (dogmata) in the face of adversity.

Filed under: Stoicism Tagged: Epictetus, marcus aurelius, stoic, stoicism

October 7, 2012

Stoicism: God or Atoms?

Can you be a modern Stoic and an atheist (or agnostic)?

Although most Stoics appear to have placed considerable importance upon belief in God (actually, Zeus), there is some indication that others may have adopted a more agnostic stance, something relatively unusual for the period in which they lived. This debate naturally interests modern Stoics, many of whom are agnostics or atheists themselves and seek to reconcile Stoic ethics and psychological practices with their own contemporary worldview.

Although most Stoics appear to have placed considerable importance upon belief in God (actually, Zeus), there is some indication that others may have adopted a more agnostic stance, something relatively unusual for the period in which they lived. This debate naturally interests modern Stoics, many of whom are agnostics or atheists themselves and seek to reconcile Stoic ethics and psychological practices with their own contemporary worldview.

According to Cicero, at least one influential Stoic explicitly discounted the importance of belief in God. Panaetius, the last “scholarch” or head of the Athenian school of Stoicism, who introduced it to Rome, is reported to have stated that discussion of the gods is “nugatory” or pointless in relation to the Stoic way of life (q.v., Algra, ‘Stoic Theology’, in The Cambridge Companion to The Stoics, 2003, p. 154).

About nine times in The Meditations, Marcus Aurelius alludes to contrasting viewpoints traditionally taken as characteristic of two opposing traditions in ancient Graeco-Roman philosophy: “God or atoms”. Belief that God (or “Providence”) ordered the cosmos was taken to be characteristic of the broad tradition originating with Pythagoras and Socrates, and including Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics. By contrast, belief that the universe was due to the random collision of atoms, originating with Democritus, was characteristic of the Epicurean school, the main rival of Stoicism. Some of Marcus’ comments are as follows:

Recall once again this alternative: ‘if not a wise Providence [God], then a mere jumble of atoms’… (iv.3)

Alexander of Macedon and his stable-boy were brought to the same state by death; for either they were received among the same creative principle of the universe [God], or they were alike dispersed into atoms. ( vi.24)

If the choice is yours, why do the thing? If another’s, where are you to lay the blame for it? On gods? On atoms? Either would be insanity. All thoughts of blame are out of place. ( viii.17)

It may be that the World-Mind [God] wills each separate happening in succession; and, if so, then accept the consequences. Or, it may be, there was but one primal act of will, of which all else is the sequel; every event being thus the germ of another. To put it another way, things are either isolated units [atoms], or they form one inseparable whole. If that whole be God, then all is well; but if aimless chance, at least you need not be aimless also. (ix.28)

Either things must have their origin in one single intelligent source [God], and all fall into place to compose, as it were, one single body – in which case no part ought to complain of what happens for the good of the whole – or else the world is nothing but atoms and their confused minglings and dispersions. So why be so harassed? (ix.39)

No matter whether the universe is a confusion of atoms or a natural growth, let my first conviction be that I am part of a Whole which is under Nature’s governance; and my second, that a bond of kinship exists between myself and all other similar parts. (x.6)

So, in summary, Marcus appears to be trying to persuade himself:

That whether we are dissolved into God or dispersed among random atoms, either way all of us, whether kings or servants, face the fate in death.

That whether the universe is rule by a provident God or due to the random collission of atoms, either way it makes no sense to blame others for our actions.

Whether the universe is governed by God or due to the “aimless chance” movement of atoms, either way “you need not be aimless also.”

Wether the universe is governed by a single intelligent Providence or it is nothing but random atoms, in either case on should not be “harassed”.

Finally, whether the universe is a “confusion of atoms” or the natural growth (of a provident God?), either way I should be convinced that I am part of something bigger, and a kinship therefore exists between me and other parts.

Scholars disagree over Marcus’ intention in presenting himself with this dichotomous choice between “God and atoms”, however. One common interpretation is that he is reminding himself that whether a creator God exists, or whether the universe is simply ordered by blind chance, in either case the practical (ethical) principles of Stoicism should still be followed. For the Stoics, who were essentially pantheists, theology was part of the discipline of “physics”, because they were materialists, who viewed God as pervading, and ordering, the whole of nature.

Moreover, I believe that a remark made by Epictetus, whose philosophy Marcus studied closely may be read as shedding further light on the contrast between “God or atoms”. In one of the fragments attributed to Epictetus (fr. 1) we are told he said the following:

What does it matter to me, says Epictetus, whether the universe is composed of atoms or uncompounded substances, or of fire and earth? Is it not sufficient to know the true nature of good and evil, and the proper bounds of our desires and aversions, and also of our impulses to act and not to act; and by making use of these as rules to order the affairs of our life, to bid those things that are beyond us farewell…

In other words, Epictetus makes it clear that questions of physics, specifically whether the universe is made of atoms or of elements such as “fire and earth”, are fundamentally indifferent with regard to Stoic ethics. The Stoics believed that the universe is composed of a divine fire-like substance with causal powers (aka “pneuma”), identified both with God and the “spark” or fragment of divinity within humans, and the inert earth or matter upon which it acts.

Epictetus goes on to say that the elements of nature are “perhaps are incomprehensible to the human mind, but even if one should suppose them to be wholly comprehensible, still, what good does it do to comprehend them?” As the Stoic thought God to be material, this might be read as a kind of agnosticism, which questions whether knowledge of God is comprehensible or necessary to the practical aims of Stoic philosophy.

Overall, I would say that the literature of ancient Stoicism suggests that Marcus Aurelius and perhaps also Epictetus believed that agnosticism or even atheism may have been consistent with the Stoic way of life. What I haven’t attempted to do here is to argue at length for the philosophical consistency of an agnostic (or atheistic) form of Stoicism. However, in this regard, I would begin by pointing to the argument that the central principle of Stoicism, that the only true good is wisdom (the cardinal human virtue or excellence), acceptance of which arguably does not require belief in God, and from which other Stoic principles may derive without the need for belief in God as an additional premise.

Filed under: Stoicism Tagged: Epictetus, God, philosophy, stoic, stoicism

October 6, 2012

Stoicism and Therapy: Exeter University

Workshop at Exeter University

Marcus Aurelius

I’ve just come back from an academic workshop at the University of Exeter, organised by Christopher Gill, Professor of Ancient Thought. Prof. Gill has a special interest in Galen and Stoicism, and their relevance for modern physical and mental wellbeing.

University of Exeter: Ancient Healthcare Blog

Along with Professor John Wilkins, Prof. Gill, leads the Healthcare and Wellbeing: Ancient Paradigms and Modern Debates project in the Department of Classics and Ancient History. The project explores the significance of ancient medicine and psychology for modern debates and practice in healthcare and psychotherapy.

Our discussion involved a number of professional psychologists, psychotherapists and academic philosophers and classicists, with a specialist interest in Stoic philosophy, including Tim Lebon, author of Wise Therapy, Jules Evans, author of Philosophy for Life, and John Sellars, author of The Art of Living: The Stoics on the Nature and Function of Philosophy. I talked briefly about the potential relevance of Stoicism for “third-wave” (mindfulness and acceptance-based) CBT, and vice versa. Prof. Gill concluded with a discussion of his recent work on the thought and writings of Marcus Aurelius, the Stoic Emperor and philosopher.

My previous book on Stoicism, The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy, goes into the practical analogies between Hellenistic philosophy and modern psychotherapy in some detail, from a moderately academic perspective. By contrast, my subsequent self-help book Build your Resilience, in addition to many references to Marcus Aurelius, concludes with a chapter on Stoicism and Psychological Resilience-Building, written as an introduction for the lay reader. This is currently being expanded by me into a new book about Stoicism, which provides a much more comprehensive introduction to the use of Stoic concepts and techniques in daily living.

Filed under: News Tagged: cbt, Cognitive behavioral therapy, marcus aurelius, stoicism

August 20, 2012

Reddit: Stoicism Q&A with Donald Robertson

Posted by Miyatarama on the Stoicism Subreddit (14th August 2012):

Hi everyone, a few months ago we had a very successful Q&A session with Dr John Sellars and now we have an opportunity to interview a modern author that approaches Stoicism from a psychology point of view. Donald Robertson, the author of The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy has graciously agreed to answer our questions about CBT and Stoicism.

Here is how this will work. Please post your questions in this thread, then I will organize them after a few days and forward them to Donald. I will then post his answers and hopefully he will be available to answer any follow-up questions within a few days of the answers being posted.

Please be sure to check out his websites: The Philosophy of CBT website

Books: The Philosophy of CBT

(Forthcoming) Resilience–How to Survive and Thrive in Any Situation

(Forthcoming) The Practice of Cognitive-Behavioural Hypnotherapy

Twitter: SolutionsCBT

Reddit: SolutionsCBT

Also, of particular interest to me is this excerpt from his book providing a Stoic Meditation script.

http://www.reddit.com/r/Stoicism/comments/y7ei9/rstoicism_interviews_donald_robertson_learn_more/

Filed under: News Tagged: cbt, Cognitive behavioral therapy, philosophy, stoicism

July 20, 2012

Reviews of The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (2010)

Stoic Philosophy as Rational and Cognitive Psychotherapy

Online Reviews as of July 2012

There are now seven reviews of The Philosophy of CBT on Amazon, all of them giving it five out of five stars:

There are now seven reviews of The Philosophy of CBT on Amazon, all of them giving it five out of five stars:

There are also six ratings and three text reviews on Goodreads, giving an average four out of five stars:

There have also been two reviews, both very positive, in academic peer-reviewed journals:

Review in the European Journal of Psychotherapy

Review in the Journal of Value Inquiry

Numerous blogs have discussed or reviewed the book. For example, Jules Evans has a bried review on The Browser blog:

Filed under: Reviews Tagged: Amazon, Philosophy of CBT, reviews, stoicism

June 18, 2012

Stoic Philosophy in Build your Resilience (2012)

Excerpts from Resilience: Teach Yourself How to Survive & Thrive in any Situation

Copyright © Donald Robertson, 2012. All rights reserved.

Copyright © Donald Robertson, 2012. All rights reserved.

ISBN: 1444168711

My previous book The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT): Stoic Philosophy as Rational and Cognitive Psychotherapy (2010) discussed the relationship between Stoic philosophy and modern cognitive-behavioural therapy in some detail, from an academic perspective. My new book, Resilience: Teach Yourself How to Survive and Thrive in any Situation (2012), is a self-help guide to psychological resilience-building, based on modern CBT. However, it contains many references to Stoic philosophy. The outline below is based on modified excerpts from the text, which is available for pre-order now from Amazon and other online book stores.

Most of the chapters begin with a quotation from Marcus Aurelius, linking ancient Stoic practices to modern cognitive-behavioural approaches to psychological resilience-building. However, the final chapter, looks at perhaps the oldest Western system of resilience-building, the classical Graeco-Roman school of philosophy known as “Stoicism”, which is derived from the teachings of Socrates and influenced the development of modern CBT (Robertson, 2010). The Stoics are, in a sense, the ancient forebears of most modern resilience-building approaches. Indeed, Epictetus, the Stoic philosopher who has most influenced the field of psychotherapy, has been described as “the patron saint of the resilient” (Neenan, 2009, p. 21).

The Essence of Stoicism

So what practical advice do the Stoics give us about building resilience? Well, this is a philosophy that can be studied for a lifetime and more detailed accounts are available. An excellent modern guide to Stoicism already exists in the book A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy by Prof. William Irvine, an academic philosopher in the USA (Irvine, 2009). My own writings, especially my book The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy, have focused on describing the relationship between Stoicism and modern psychotherapy (Robertson, 2010; Robertson, 2005).

However, although, Stoicism is a vast subject, it was based upon a handful of simple principles. Epictetus summed up the essence of Stoicism as “following Nature” through the “correct use of impressions”. By “following Nature”, the Stoics meant something twofold: accepting external events as decreed by the Nature of the universe, while acting fully in accord with your own nature as a rational human being, living in accord with your core values. (Scholars capitalise “Nature” when referring to the nature of the universe as a whole, whereas lower-case “nature” means your internal human nature as an individual.)

Don’t treat anything as important except doing what your nature demands, and accepting what Nature sends you. (Meditations, 12:32)

Reverence: so you’ll accept what you’re allotted. Nature intended it for you, and you for it.

Justice: so that you’ll speak the truth, frankly and without evasions, and act as you should – and as other people deserve. (Meditations, 12: 1)

However, the basic twofold principle “follow Nature” leads on to an elaborate system of applied philosophy, which this chapter will explore in more detail.

The first few passages of the philosophical Handbookof Epictetus provide arguably the most authoritative summary of basic Stoic theory and practice. I’ve paraphrased the key statements below, to highlight the possible continuity with ACT, CBT and the approaches to resilience-building discussed in this book.

1. The Handbookbegins with a very clear and simple “common sense” declaration: Some things are under our control and others are not.

2. Our own actions are, by definition, under our control, including our opinions and intentions (e.g., commitments to valued action), etc.

3. Everything other than our own actions is not under our direct control, particularly our health, wealth and reputation, etc. (Although, we can influencemany external things through our actions we do not have complete or direct control over them, they do not happen simply as we will them to.)

4. Things directly under our control are, by definition, free and unimpeded, but everything else we might desire to control is hindered by external factors, i.e., partly down to fate.

5. The Stoic should continually remember that much emotional suffering is caused by mistakenly assuming, or acting as if, external things are directly under our control.

6. Assuming that external events are under our control also tends to mislead us into excessively blaming others and the world for our emotional suffering.

7. However, if you remember that only your own actions are truly under your control and external things are not, then you will become emotionally resilient as a result (“no one will harm you”) and you may achieve a kind of profound freedom and happiness, which is part of the ultimate goal of Stoicism.

8. To really succeed in living as a Stoic, you need to be highly committed, and may need to abandon or at least temporarily postpone the pursuit of external things such as wealth or reputation, etc. (Stoics like Epictetus lived in poverty while others, like Marcus Aurelius, tried to follow the principles while commanding great wealth and power – both were considered valid ways of living for a Stoic but Marcus perhaps believed his complex and privileged lifestyle made commitment to Stoicism more difficult at times.)

9. From the very outset, therefore, the Stoic novice should rehearse spotting unpleasant experiences (“impressions”) and saying in response to them: “You are an impression, and not at all the thing you appear to be.” (Something that closely this resembles the basic strategy we call “distancing” or “defusion” in modern CBT.)

10. After doing this, ask yourself whether the impression involves thinking about what is under your control or not; if not, then say to yourself, “It is nothing to me.” (Meaning, it’s essentially indifferent to me if it’s not under my control – I just need to accept it; although the Stoics did admit that some external outcomes are naturally to be preferred, despite lacking true intrinsic value.)

The Teach Yourself book goes on to describe the basic principles of Stoicism in more detail and, in particular, to elaborate upon some of the basic psychological strategies employed for resilience-building by the Stoic sages, such as acting “with a reserve clause”, visualising the “view from above”, and contemplation of the ideal Sage, etc.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction: What is Resilience?

2. Letting go of Experiential Avoidance

3. Values Clarification

4. Commitment to Valued Action

5. Acceptance & Defusion

6. Mindfulness & the Present Moment

7. Progressive Relaxation

8. Applied Relaxation

9. Worry Postponement

10. Problem-Solving Training

11. Assertiveness & Social Skills

12. Stoic Philosophy & Resilience

About the Author

Donald Robertson is a psychotherapist with a private practice in Harley Street. He is a CBT practitioner specialising in treating anxiety and building resilience and director of a leading therapy training organisation. He is the author of many journal articles and three books on therapy, The Philosophy of CBT, The Discovery of Hypnosis, and The Practice of Cognitive-Behavioural Hypnotherapy, and blogs regularly from his website www.londoncognitive.com.

Pre-Order Online

Available for pre-order online from….

Amazon

WH Smiths

Waterstones

Blackwells

The Book Depository

Filed under: Excerpts Tagged: Cognitive behavioral therapy, Epictetus, marcus aurelius, philosophy, stoic, stoicism

June 5, 2012

The Earl of Shaftesbury on The View from Above

The View from Above

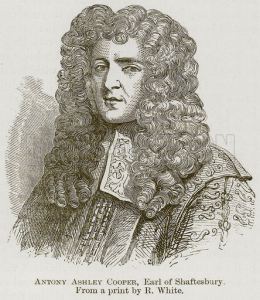

Antony, Earl of Shaftesbury

This quotation from the private philosophical regimen of Antony Ashley-Cooper, the third Earl of Shaftesbury (1671-1713), contains a good description of The View from Above, probably closely based upon his reading of Marcus Aurelius:

View the heavens. See the vast design, the mighty revolutions that are performed. Think, in the midst of this ocean of being, what the earth and a little part of its surface is; and what a few animals are, which there have being. Embrace, as it were, with thy imagination all those spacious orbs, and place thyself in the midst of the Divine architecture. Consider other orders of beings, other schemes, other designs, other executions, other faces of things, other respects, other proportions and harmony. Be deep in this imagination and feeling, so as to enter into what is done, so as to admire that grace and majesty of things so great and noble, and so as to accompany with thy mind that order, and those concurrent interests of things glorious and immense. For here, surely, if anywhere, there is majesty, beauty and glory. Bring thyself as oft as thou canst into this sense and apprehension; not like the children, admiring only what belongs to their play; but considering and admiring what is chiefly beautiful, splendid and great in things. And now, in this disposition, and in this situation of mind, see if for a cut-finger, or what is all one, for the distemper and ails of a few animals, thou canst accuse the universe.

Filed under: Philosophy of CBT Tagged: Earl of Shaftesbury, marcus aurelius, philosophy, stoic, stoicism