Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 81

February 2, 2013

Marcus Aurelius

New Stoicism Discussion Group on Facebook

I’ve created a new Stoicism Group on Facebook, which anyone can join, for Discussion of Stoic Philosophy!

I’ve created a new Stoicism Group on Facebook, which anyone can join, for Discussion of Stoic Philosophy!

https://www.facebook.com/groups/Stoicism/

Come along and join in!

Filed under: Stoicism Tagged: philosophy, stoic, stoicism

February 1, 2013

Action with a “Reserve Clause” in Marcus Aurelius

There are five references to the concept of acting “with a reserve clause” in The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, which he obviously employs as a kind of technical term. This isn’t very clear in some of the English translations available. The concept of action “with a reserve clause” (hupexhairesis) is obviously closely-related to the concept of “moral choice” (prohairesis) and the definition of the good as “worthy of being chosen” (haireton) in accord with reason and nature.

The concept of the “reserve clause” (exceptio in Latin) can be found in Seneca and Epictetus, and to some extent in Cicero’s writings on Stoicism. The basic idea is that Stoics must act in the world, although the good of their own soul (wisdom and virtue) is the chief goal in life, external and bodily things, despite being classed as “indifferent” with regard to our ultimate wellbeing, are to be “selected” or “rejected” in a somewhat detached manner, insofar it is natural and rational to either get or avoid them. In other words, we should pursue external goals with the caveat: “Fate permitting.” There’s a good description of this in the New Testament:

Now listen, you who say, “Today or tomorrow we will go to this or that city, spend a year there, carry on business and make money.” Why, you do not even know what will happen tomorrow. What is your life? You are a mist that appears for a little while and then vanishes. Instead, you ought to say, “If it is the Lord’s will, we will live and do this or that.” (James, 4:13-15)

Hence, Christians used to write “D.V.” or “Deo Volente” (God willing, in Latin) at the end of letters. However, Marcus makes it explicit that he’s deriving the concept, in part, from Epictetus, whom he quotes.

Hear Epictetus: No one can rob us of our free choice. We must, says he, hit upon the true science of assent and in the sphere of our impulses pay good heed that they are with a “reserve clause”; that they have in view our neighbour’s welfare; that they are proportionate to a thing’s value. And we must abstain wholly from inordinate desire and show avoidance in none of the things that are not in our control. (Meditations, 11.37-38)

The Stoics believed the mind was composed of a physical substance like a subtle form of fire, and Marcus describes its ability to adapt to external events, through the “reserve clause”, as resembling an all-consuming fire.

That which holds the mastery within us, when it is in accordance with Nature, is so disposed towards what befalls, that it can always adapt itself with ease to what is possible and granted us. For it is wedded to no definite material, but in the pursuit of its aims it works with a “reserve clause”; it converts into material for itself any obstacle that it meets with, just as fire when it gets the mastery of what is thrown upon it. (Meditations, 4.1)

What stands in the way becomes the way:

Though a man may in some sort hinder my activity, yet on my own voluntary impulses and mental attitude no fetters can be put because of the “reserve clause” and their ability to adapt to circumstances. For everything that stands in the way of its activity is adapted and transmuted by the mind into furtherance of it, and that which is a check on this action is converted into a help to it, and that which is a hindrance in our path goes but to make it easier. (Meditations, 5.20)

The “reserve clause” is a way of overcoming emotional pain and as the perfect Sage cannot, by definition, be happy (eudaimon) if he is distressed, then he must act at all times according to this rule.

Try persuasion first, but even though men would say to you not to, act when the principles of justice direct you to. If anyone one should obstruct you by force, take refuge in being contented and without emotional pain, and use the obstacle for the display of some other virtue. Remember that the impulse you had was with an “reserve clause”, and your aim was not to do the impossible. (Meditations, 6.50)

However, he also seems to refer this concept to the image of the “sphere” of the presocratic philosopher Empedocles, which he mentions three times in The Meditations.

If your impulse is without an “reserve clause”, failure at once becomes an evil to you as a rational creature. But once you accept that universal necessity, you cannot suffer harm nor even be thwarted. Indeed, nobody else can thwart the inner purposes of the mind. For it no fire can touch, nor steel, nor tyrant, nor public censure, nor anything whatsoever: a sphere once formed continues round and true. (Meditations, 8.41)

Filed under: Stoicism Tagged: philosophy, stoic, stoicism

January 27, 2013

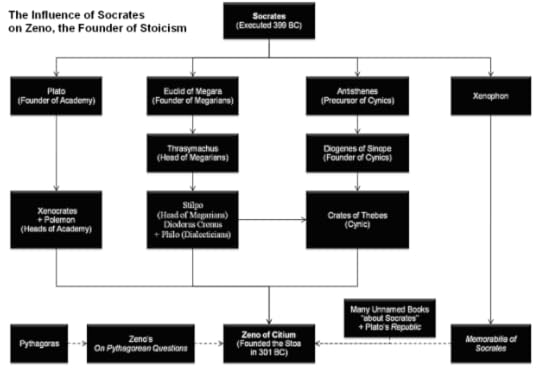

The Influence of Socrates on Stoicism

Please add your comments below. You’ll probably need to click on the image to enlarge its size for readability… You can also read more about this diagram on the page below:

http://philosophy-of-cbt.com/diagram-the-influence-of-socrates-on-stoicism/

Click to enlarge!

Filed under: Stoicism Tagged: diagram, stoic, stoicism

January 22, 2013

Complete Online: The Stoic Attitudes Scale (Test Version)

January 21, 2013

Stoic Attitudes Scale

(Version for preliminary testing only!)

(Version for preliminary testing only!)

Copyright © Donald Robertson, 2013. All rights reserved.

NB: Your feedback is much appreciated, especially on whether the questions make sense to you, and whether you feel they adequately assess (self-rated) attitudes that would be consistent with a classical Stoic philosophy of life.

Introduction. This scale is still under development. The initial version is designed to help arrive at a consensus on items (questions/statements) that accurately and comprehensively define a classical Stoic philosophical outlook. There’s also a section for basic Stoic practices or cognitive and behavioural strategies. In some cases a balance has to be struck between fidelity to the ancient tradition and making the statements comprehensible to a modern research participant. This scale is initially being developed with a view to using it in correlational research to establish the extent to which existing Stoic attitudes, among students of Stoicism or the general population, correlate with established measures of psychological resilience, emotional wellbeing, etc. (There are currently no reverse-scored questions, although these may be incorporated at a later date.)

Rate how strongly you agree with each of the statements below using this scale:

1. Strongly disagree / 2. Disagree / 3. Neither agree nor disagree / 4. Agree / 5. Strongly agree

Overall Self-Rating of Stoicism

“I would describe myself as someone who believes in and tries to follow the Stoic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium.”

Stoic Beliefs & Attitudes

1. “The goal of human life is to attain personal happiness and fulfilment.”

2. “I seek to achieve happiness by living in harmony with my own nature and the world around me.”

3. “When we accept what happens to us, insofar as it’s outside of our control, life goes smoothly and it’s easier to remain calm.”

4. “Virtue, or excelling in terms of our moral reasoning, is the only true good in life and vice the only true evil.”

5. “I like to think of all things in the universe as being parts of a unified whole.”

6. “I think all virtues are fundamentally one and the same thing, different forms of practical wisdom.”

7. “The material world is in constant change, as things gradually turn into their opposites.”

8. “All material things are transient.”

9. “We shouldn’t be surprised by any misfortune because we know various things befall other people in life.”

10. “Virtue consists in perfecting our essential nature as rational and social beings.”

11. “Moral goodness is all that’s required to have a good life.”

12. “Health, wealth, reputation, and other ‘external’ things can never contribute to genuine happiness and fulfilment in life.”

13. “The most important human virtues are prudence, justice, courage, and moderation.”

14. “Peace of mind comes from abandoning fears and desires about things outside our control.”

15. “Virtue consists in perfecting our rational nature, through cultivating wisdom.”

16. “Practical wisdom mainly entails knowledge of what is good, bad, and indifferent in life.”

17. “The fear of death is more harmful to the good life than death itself.”

18. “Things beyond our control neither help nor harm our ability to flourish and be fulfilled in life.”

19. “Emotional suffering is based on irrational judgments that place excessive value on external things.”

20. “The only things truly under our control in life are our judgments and acts of will.”

Stoic Behaviours & Strategies

21. “I like to contemplate what a perfectly wise and good person would do when faced with various misfortunes in life.”

22. “We should wish that other people attain wisdom and flourish, fate permitting, while accepting that it is ultimately outside of our control.”

23. “It’s important to anticipate future misfortunes and to rehearse rising above them.”

24. “I often contemplate the smallness and transience of human life in relation to the totality of space and time.”

25. “Virtue requires effort in the form of continual attention to our judgments and actions.”

26. “It’s natural and healthy to be grounded in the present moment.”

27. “I try to live simply and with moderation.”

28. “When a disturbing thought enters my mind the first thing I do is remind myself it’s just an impression and not the thing it claims to represent.”

29. “I regularly contemplate the inevitability of my own death in order to come to terms with my mortality.”

30. “I routinely examine my own actions and evaluate what I did well, what badly, and what I omitted to do.”

Filed under: Stoicism Tagged: evidence, philosophy, research, stoic, stoicism

January 18, 2013

Cognitive Distancing in Stoicism

“Distancing” versus “Disputation” as the central process of Stoic psychotherapy

Copyright © Donald Robertson, 2013. All rights reserved.

Copyright © Donald Robertson, 2013. All rights reserved.

This article explores the question whether “distancing” from thoughts/impressions or “disputation” of underlying irrational beliefs is more integral to Stoic therapy. If it were established that Stoicism employs a focus on “cognitive distancing” strategies that would be important for several reasons. Distancing is a simpler and more consistent procedure than verbal disputation, so analogies between Stoicism and CBT would be easier to make. Moreover, large volumes of research now exist on distancing, which suggest that it may be one of the most important mechanisms in psychotherapy, and may serve both a preventative and remedial function. Some modern researcher also believe that disputation may interfere with distancing, which would be an important consideration for modern Stoics to assimilate.

The first major modern psychotherapist to notice the relevance of ancient Stoic philosophy for their work was Albert Ellis. In the late 1950s, Ellis began developing what later became known as Rational-Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT). REBT is the main precursor of modern cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), currently the approach to psychological therapy with by far the strongest evidence-base for most clinical problems. Ellis had read the Stoics as a youth. He later trained in and practiced psychoanalytic therapy. However, after becoming disillusioned with psychoanalytic theory and practice he started looking for a radically different approach, and remembered Stoicism. Hence, Ellis explicitly stated that Stoicism was the main philosophical inspiration for REBT, and it stands in the same relation to subsequent CBT approaches in general, although these are really quite a diverse cluster of different therapies, rather than a single homogenous approach.

Ellis’ approach placed considerable emphasis on the systematic and vigorous verbal disputation of irrational beliefs – its characteristic feature. However, he used to provide clients with a quotation from Epictetus to illustrate his basic premise that our beliefs are at the root of emotional disturbance: “It is not the things themselves that disturb people but their judgements about those things” (Enchiridion, 5). This quotation highlights a basic assumption shared by all cognitive-behavioural therapies: that we should begin by separating our thoughts from external events. Ellis and Beck, the founder of cognitive therapy, both saw this as an important insight in therapy but mainly because it was a necessary precursor to the use of disputation techniques. Typically, for example, REBT or CBT practitioners would ask their clients to evaluate the “pros and cons” of an irrational belief, or the evidence “for and against it”, and to identify alternative rational beliefs to replace it with. This, combined with “behavioural experiments” designed to test out and challenge irrational beliefs in practice, form the bulk of what happens in most modern CBT sessions.

However, although the Stoics do appear to have sometimes challenged specific beliefs in ways that loosely resemble this, it’s not their dominant approach. REBT and CBT might encourage clients to challenge underlying (“core”) irrational beliefs such as “I am worthless” or “Other people must like me otherwise it’s awful!” When philosophically evaluating beliefs, they tend to focus on defending underlying precepts of an even more general nature from which individual judgements are derived, such as “the only good is moral good”, considering the possible criticisms, or arguments against these positions, and those in favour of them. Whereas CBT and REBT often target “underlying” value judgements, Stoic disputation might be described as more “philosophical” or “meta-ethical” as it tends to concern the very nature of “the good” itself. The Stoics do appear to have challenged their judgements about specific situations but the focus in their writings is typically more on defending their core philosophical dogmas. Moreover, when Stoics do examine particular situations they appear to place more emphasis on constructing a positive mental representation of how the Sage might act, or what virtues Nature has granted that allow them to rise above adversity. CBT places more emphasis on the identification and direct disputation of negative or irrational beliefs.

Since the 1990s, different researchers have introduced alternative approaches to CBT that are collectively known as the “third-wave” movement. (The first wave was behaviour therapy in the 1950s and 1960s, the second the rise of cognitive therapy in the 1970s and 1980s.) Although there are significant differences between these new forms of CBT, they all tend to place less emphasis on direct verbal disputation of beliefs and more on the initial step of gaining “cognitive distance” (follow link for a detailed article on this concept). Beck defined “distancing” in cognitive therapy as a “metacognitive” process, a shift to a level of awareness involving “thinking about thinking”, which he defined succinctly as follows:

“Distancing” refers to the ability to view one’s own thoughts (or beliefs) as constructions of “reality” rather than as reality itself. (Alford & Beck, 1997, p. 142)

In CBT, clients are usually “socialised” or introduced to this notion through the use of simple diagrams or metaphors. For example, they may be taught that when thoughts distort our perception of events it’s like we’re wearing coloured spectacles. When we gain cognitive distance from our own thoughts, it’s as though we’re taking off the spectacles and looking at them, rather than looking through them. A similar “distancing” mechanism has been seen as integral to mindfulness meditation practices which have been found effective in the treatment of depression, and were therefore integrated with some forms of CBT. Therefore, the third-wave approaches are often described collectively as the new “mindfulness and acceptance-based” approaches. For example, one of the most prominent of these, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), was originally called “comprehensive distancing” because it explicitly aimed to test the hypothesis that the initial “cognitive distancing” strategy in conventional CBT was much more important than had previously been assumed.

Unlike REBT and Beck’s cognitive therapy, these recent forms of therapy do not explicitly claim to be influenced by Stoic philosophy. However, perhaps by chance, they may have many similarities with aspects of Stoicism that were overlooked by the founders of CBT. In particular, it might be argued that Stoicism itself placed more emphasis on a something akin to “cognitive distancing” than upon direct disputation of beliefs. This may have been somewhat overlooked by scholars because “distancing” is a more subtle and elusive concept than disputation. For that reason, sometimes it is difficult to tell if the Stoics are genuinely referring to the same mechanism, as this often turns on subtleties of translation and interpretation.

One of the passages that stands out in this regard occurs in the Enchiridion of Epictetus, where he writes:

Make it, therefore, your study at the very outset to say to every harsh impression: “You are an impression [phantasia] and not at all what you appear to be [phainomenon].” (Enchiridion, 1) [Alternatively, more literally: “You are an appearance and not the whole thing appearing.”]

Epictetus, as is often the case, appears to be literally instructing his students to repeat this phrase to themselves as part of a general-purpose psychological strategy for managing disturbing thoughts or impressions. The fact that this occurs in the first passage of the Enchiridion may also signal its importance. It’s presented, as in cognitive therapy, as a prelude to other strategies, which involve “testing” the impression by applying the core precepts of Stoicism to it. At this point, cognitive therapy might involve weighing up the evidence for and against the impression (or “automatic thought”), or identifying the types of distortion it contains, such as “over-generalisation” or “black and white thinking”, etc. However, Epictetus says the most important response a Stoic can make is to question whether the impression has to do with things under our control or not. If it refers to something external, the student is to say to it: “It is nothing to me.” That is, this is completely indifferent with regard to happiness and the good life, the chief goal of Stoicism. The Stoics appear to have realised, as modern CBT does, that any form of re-evaluation or disputation is impossible unless the initial step of gaining “psychological distance” takes place first. I have to be able to view my judgements as hypothesis (merely impressions) rather than as facts (confusing them with the things they claim to represent), before I can begin to question them as such.

Beck’s cognitive therapy writings only discuss “cognitive distancing” very briefly, although he does mention about half-a-dozen practical strategies, which are taught to clients in the initial stage of therapy. For example:

Writing down negative automatic thoughts on a daily thought record, particularly fleeting automatic thoughts that might normally go unnoticed or get conflated with feelings

Writing thoughts on a blackboard and literally viewing them from a distance, as something objective and “over there”, by patiently describing the colour, size, and style of the writing, etc.

Viewing thoughts as inferences or hypotheses instead of facts, distinguishing between “I believe” and “I know”, discriminating carefully between thoughts and facts

Referring to your thoughts and feelings in the third-person (“Bill is having anxious feelings, he’s thinking that people are criticising him…”)

Using a counter to keep a tally of specific types of automatic thoughts, seeing them as habitual and repetitive, as just a meaningless side-effect of previous experience rather than something important and meaningful that deserves to be taken seriously

Self-observation, being aware of your own awareness, noticing how you observe your thoughts, maintaining a sense of yourself as conscious observer, separate from the contents of your stream of consciousness

Shifting perspectives and imagining being in the shoes of other people, who might disagree with your beliefs and view things differently, adopting a different perspective on things and identifying a range of alternative views, among which your current thought is just one of many

ACT and other third-wave therapies have added more techniques to this list and refined the existing ones. In particular, they’ve introduced the use of mindfulness meditation techniques, derived from Buddhism, which are mean to train clients to develop greater detachment or psychological distance from their thoughts. Beck himself never mentioned the use of meditation in this way, although it may seem an obvious adjunct to the techniques described above.

Moreover, a brief survey of the Stoic literature suggests that most of the psychological techniques employed can be seen as relating more to the mechanism of “distancing” than “disputation”. For example, in the Enchiridion, Epictetus instructs students of Stoicism to do the following:

We should continually maintain attention (prosoche) to the leading faculty of the mind (hegemonikon), watching our judgements as they happen; as if watching our steps, cautious of stepping on a sharp object, or as if looking out for an enemy in hiding

When upset, we should always remind ourselves that it is our judgment that harms us and not the external thing itself, and we should guard against being “swept away” by upsetting external impressions

When something appears to be upsetting, you should imagine the same thing befalling someone else, so that you can judge it from a distance

We should abandon value judgements and stick instead to a bare description of the facts of a situation, which forces us to see our value judgements as something we’re imposing on events rather than an intrinsic characteristic of external events themselves

We should remind ourselves how the wise man would judge the same thing differently because noting that different people view things differently helps us to distinguish our thoughts from external facts. Epictetus’ favoured example: Death cannot be intrinsically evil otherwise Socrates would have judged it to be so.

We should postpone responding to impulses associated with powerful impressions until later, something which forces us to adopt a more detached perspective on them – modern therapists call this taking a “time-out” or simply “postponement”

These might be described as brief “shifts in perspective” rather than stepwise methods of disputation. They are perhaps more experiential than verbal. There’s no need to evaluate the evidence for these judgements, the Stoic simply reminds himself that they are judgements, peeling them away from the surface of reality, as it were, and viewing them as events within his own mind. The Stoics referred to this process as “withholding assent” from initial impressions that mistakenly ascribe intrinsic value to indifferent things. They assumed that impressions are outside of our control, being triggered by external events, like the “automatic thoughts” of cognitive therapy. However, we do control what happens next: whether we accept the impression as reality or not, by giving our “assent” and saying “yes” to it. Interestingly, the Stoics don’t seem to refer to saying “no” or exercising “dissent” toward impressions, merely suspending assent appears to be sufficient, at least at first. Shortly after, attention may be shifted on to alternatives to the initial impression, such as “What would the Sage do?”

Some researchers, most notably the founders of ACT, have argued that verbal disputation techniques may interfere with psychological distance (which they call “cognitive defusion”). The best way to illustrate this is perhaps by considering the example of Buddhist-style mindfulness meditation. While meditating, if a distracting thought crosses the mind, mindfulness practitioners are taught to view it with detachment and resist the urge to respond to it by analysing its meaning or engaging in an internal dialogue about it. They might view it as if it were like a cloud passing across the sky and “let it go”. Engaging with the thought can simply make it more prominent, even if someone is attempting to challenge or dispute it. One can easily be swept along with the thought this way and lose psychological distance from it. The relative brevity of Stoic techniques arguably lends itself to maintaining psychological distance from upsetting impressions. That could be lost again, though, if you “get into a debate with yourself” about the truth or falsehood of certain thoughts. There’s a considerable body of modern research showing that attempts to suppress or distract oneself from distressing thoughts tend to be counter-productive. Gaining psychological distance neatly circumvents this problem because it means neither assenting to (“buying into”) a thought nor trying to eliminate it, but rather viewing it from a detached perspective. Rather than “I must not have this thought”, someone with psychological distance from their thoughts might say: “It’s okay to have this thought cross my mind but it’s just a thought, I don’t need to dwell on it or take it too seriously.” There appear to be some references in the Stoic literature to suppressing automatic thoughts or feelings, though, which would be considered unhealthy and problematic from the perspective of modern research on psychotherapy. However, the dubious strategies of thought-suppression or distraction do not seem to be an important or necessary part of Stoic therapeutics, and could easily be replaced with more consistent emphasis on “cognitive distancing” or merely withholding assent.

Filed under: Stoicism Tagged: cbt, cognitive therapy, mindfulness, philosophy, stoic, stoicism

Roundup of Recent Posts (January 2013)

January 17, 2013

Some Musings on the Nature of the Good in Stoicism

Some Musings on Stoic Ethics

This will be a bit of a different blog post from me. Rather than publishing a finished piece of work, I’m just going to post some thoughts on a work in progress. I’m currently writing something on Stoic Ethics and particularly the definition of the good in Stoicism. This is arguably the central definitive feature of Stoicism. Famously, Stoicism was divided into three topics: ethics, physics and logic. However, when ancient authors compare Stoicism to other philosophical schools they typically focus on the uniquely uncompromising ethical doctrines adopted by the Stoics. Although there are many similarities between Stoicism and certain other schools of philosophy, particularly the “Academic” (Platonic) and “Peripatetic” (Aristotelian) schools, there are also some celebrated differences. The other philosophical schools generally recognised that the most important good for man was virtue or excellence (aretê). The main exception were the Epicureans who believed the chief good in life to be pleasure. However, those schools that recognised the importance of virtue tended to endorse a composite view of the good life, which required other non-moral goods as well, i.e., external goods as well as the virtues. The Aristotelians introduced a threefold distinction between types of good, in descending order of value:

This will be a bit of a different blog post from me. Rather than publishing a finished piece of work, I’m just going to post some thoughts on a work in progress. I’m currently writing something on Stoic Ethics and particularly the definition of the good in Stoicism. This is arguably the central definitive feature of Stoicism. Famously, Stoicism was divided into three topics: ethics, physics and logic. However, when ancient authors compare Stoicism to other philosophical schools they typically focus on the uniquely uncompromising ethical doctrines adopted by the Stoics. Although there are many similarities between Stoicism and certain other schools of philosophy, particularly the “Academic” (Platonic) and “Peripatetic” (Aristotelian) schools, there are also some celebrated differences. The other philosophical schools generally recognised that the most important good for man was virtue or excellence (aretê). The main exception were the Epicureans who believed the chief good in life to be pleasure. However, those schools that recognised the importance of virtue tended to endorse a composite view of the good life, which required other non-moral goods as well, i.e., external goods as well as the virtues. The Aristotelians introduced a threefold distinction between types of good, in descending order of value:

Goods of the soul, such as virtue

Goods of the body, such as physical health

Goods of accident or external goods, such as wealth and reputation

Happiness (eudaimonia) was generally understood by all schools to be the chief goal in life, although they defined it differently. Happiness isn’t a subjective feeling but rather a state of fulfilment or “flourishing”. It was generally agreed to equate with the “good life”, which was assumed to be a life that is, in a sense, complete: lacking nothing good, and containing nothing bad. Hence, Cicero wrote: “When we say ‘happy’ the essential significance of this word is that everything that is bad shall be excluded and everything good shall be included.” Virtue may be essential but someone cannot be said to have a good life, it was felt, and to be happy, unless he also has a good healthy body and possesses external goods, such as property and good reputation. That might seem like common sense. However, it does leave it somewhat in the hands of fate whether someone has a good life and attains happiness/fulfilment or not because of the three categories of “good”, only the first is actually under our control. Hence, Theophrastus (the Peripatetic) apparently wrote: “Chance, and not wisdom, rules the life of men”, which Cicero says his critics called “the most demoralizing utterance that any philosopher has ever made.” By contrast, even Epicurus wrote: “Over a man who is wise, chance has little power.”

The Stoics notoriously challenged this notion of a composite good life encompassing three distinct classes of good, and adopted instead a stridently moral position. They vigorously argued that good men necessarily have good lives, regardless of their external fortune. As Cicero wrote:

The belief of the Stoics on this subject is simple. The supreme good, according to them, is to live according to nature, and in harmony with nature. That, they declare is the wise man’s duty; and it is also something that lies within his own capacity to achieve. From this follows the deduction that the man who has the supreme good within his power also possesses the power to live happily. Consequently, the wise man’s life is happy. (Tuscalan Disputations, 5.28)

This forces them to reject the threefold view above and to argue that “the only good is moral good” or virtue. Health, wealth, and reputation might be called “goods” but this is only a figure of speech. They are not truly “good” in the same sense as virtue. Crucially, the life of the virtuous man lacks nothing, even if it is deprived of health, wealth, and reputation. The Sage is complete, whatever misfortunes befall him. His is the good life and he is therefore supremely happy.

The life of a wealthy and famous man, who is full of vice, is not one iota better than that of a poor and ridiculed Sage. Cicero illustrates this with the metaphor of scales, a kind of “moral balance”, which he attributed to a Peripatetic philosopher called Critolaus of Phaselis. He said that if virtue is placed on one side of the scales, no matter how many external (or bodily) goods are heaped up on the other side, it would never be enough to shift the balance. This is a colourful way of expressing the notion that moral and external goods are absolutely incommensurate for the Stoics. Indeed, for these reason they refer to external and bodily things as “indifferent”. Epictetus advises his students to rehearse literally saying in response to them: “This is nothing to me.” No amount of health, wealth, and reputation, can outweigh the importance of wisdom, justice, courage, self-control, etc. Now, the Stoics (with some exceptions) did recognise that health, wealth, and reputation, etc., were naturally to be desired, and preferred to disease, poverty, and condemnation. Rather than refer to these as “good” and “bad”, though, they refer to them as “preferred” and “dispreferred” or “advantageous” and “disadvantageous” to make it clear that they were talking about a second (different) system of value. This led some ancient authors to argue that the Stoics were merely introducing a terminological distinction. However, others felt that they were making an important ethical distinction that marked their whole philosophical system out from the other schools. Of course, among different Stoics, Platonists, and Aristotelians, some were closer to the views of rival schools and some further removed, in terms of their own philosophy.

For example, some of the arguments employed by ancient Stoics to defend the view that “moral goodness is sufficient for perfect happiness” are as follows:

The Sage is Beyond Emotional Disturbance

It’s not external goods that determine our happiness but our fears and desires with regard to them. Emotional disturbance is incompatible with peace of mind and complete happiness. Human (moral) goodness necessarily entails the possession of virtues such as wisdom, courage and self-control, through which we overcome emotional disturbance. The perfectly good man is therefore free from emotional disturbance. Or rather he’s as free from disturbance as he can be, through voluntary action, although he may still experience some distress in the form of automatic thoughts and feelings, which may occur unbidden. The good man therefore also has a good and happy life because he is not distressed even by the lack of external and bodily goods.

The Sage is Confident about Fortune

Cicero argues that the ideal Sage must have an unshakeable sense of security. If he does not know that the good life is under his control then he is doomed to experience anxiety and insecurity. The Sage is therefore inconceivable unless we assume that all of the ingredients of the good life are under his control, that happiness is entirely within his grasp. Moral good must therefore be the only good and sufficient for happiness because perfect happiness that depends on external fortune would necessarily be polluted by uncertainty over the future. Cicero says, “nothing that there is the slightest possibility of eventually losing can be regarded as an ingredient of the happy life”, which would relegate all bodily and external goods to the level of “indifferent” things.

The Good Life is Praiseworthy

The good life of the Sage is thoroughly praiseworthy. However, only moral good is praiseworthy. We do not praise a man because of his wealth, health or reputation but because of his virtues. Although people desire external goods for themselves, in other words, they do not really praise their possession in others. The only true good therefore is moral good, because only moral good is agreed to be truly praiseworthy. A foolish and unjust man is no more praiseworthy if he is healthy, rich, and famous. A Sage, like Diogenes or Socrates, is no less praiseworthy if he is physically frail, poor, and ridiculed. In fact, ironically, the Sage may actually be even more praiseworthy if he retains his virtues despite misfortune, i.e., the loss of bodily and external goods.

I will give you a short rule of thumb by which to measure yourself, by which you will perceive that you are now perfect; you will have your own good when you understand that the successful are the most unsuccessful. (Seneca, Letters, 124)

In particular, although foolish men may sometimes judge the “good” otherwise, someone who is wise and good will judge the value of all things in terms of how praiseworthy they are but only the morally good is praiseworthy, he will therefore judge his own life and that of others in terms of how praiseworthy and morally good they are. The Sage will therefore not judge the value of his life as the majority of men do, but because of his possession of virtue, he will judge his life to be good or bad purely in moral rather than material terms.

What is Truly Good Cannot be Made Bad

The Stoics argue that what is “good” in the true sense of the word, what is intrinsically and absolutely good, cannot be turned into something bad. If it seems something “good” has turned into something “bad”, that suggests that it was never really good at all, but that its use was good. For example, the wealth of a good man is “good” insofar as it is used virtuously, but the wealth of a bad man is judged a “bad” thing, if used viciously by him. Hence, these things are actually indifferent, but the wisdom and virtue of the person using them are what is truly good. External things are made apparently “good” or “bad” by the use we make of them, but the presence or absence of external goods cannot affect virtue.

The Finitude and Transience of Virtue Doesn’t Affect its Value

The Stoics would perhaps want to argue that contemplating the transience of all material things and the finitude of human existence allows us to see the whole picture more clearly, in a way that allows the mind to naturally better discern where true value (the good) really lies. Heaping up wealth, enjoying pleasure, or acquiring fame, for a few seconds might seem very trivial, and when considered in relation to the whole cosmos, all human life appears as if it might as well be a few seconds in duration. However, do we naturally judge virtue’s worth in the same way? An act of great courage and integrity may take place in a few seconds but would we naturally discount that as worthless in the way we do with fleetingly brief pleasures? Someone might say that we don’t normally focus on the bigger picture, so why should we care? The Stoics might respond that the totality is the truth and that our normal, narrow perspective on events is a falsehood, a kind of “selective thinking” or lie of omission. It’s striking that a split-second of absolute bravery appears so valuable whereas pleasure, wealth, and public acclaim, seem to lose their worth if they are merely fleeting. All mortal things are miniscule and fleeting, though, compared to the whole of Nature, the Cosmos, or the Olympian perspective of Zeus.

Socrates and Cato Looked Down on Death

As Epictetus puts it very bluntly: Death cannot be an evil for if it were then Socrates would have judged it to be so also. He’s alluding to a more general Stoic argument which says that if external things were truly “good” or “bad” then everyone would agree that they are, especially the most wise. It’s our own judgements that make external things appear good or bad, and consequently distress us. The Stoics argue that some animals will risk injury and death to protect their young, so they do not judge these things to be absolutely bad. Likewise, even foolish men will often endure things others fear or renounce things others desire, in order to achieve other (foolish) goals. Acrobats, soldiers, and lovers, will often risk their lives, because of something else they judge more important than avoiding death. Hence, things are neither good nor bad but thinking makes them so. However, wisdom is defined as the knowledge of good and bad, and so it is the only thing which we can truly say is good, and folly is bad. The virtues are all defined as forms of knowledge and therefore species of practical wisdom. So perhaps the Stoics, who do note this circularity, might say that nothing is good except the wisdom to know that “nothing is good except wisdom”. (This recalls Socrates’ “ironic” claim to know only that he knows nothing, and to be wiser than other men in that respect alone.)

Filed under: Stoicism Tagged: Ethics, good, philosophy, stoic, stoicism

January 6, 2013

Blues Version of Marcus Aurelius

Animated recital of an excerpt from Book Two of The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, er, set to a blues rock backing track.

Filed under: Stoicism Tagged: stoic, stoicism, video