Jacqueline Davies's Blog

July 30, 2021

Fruition (literally)

It’s that time of the year, when the garden has grown wild and unruly and I’ve pretty much given up. I allow myself to wander without purpose and marvel at the petty miracles that present themselves to me like mid-summer gifts: the astonishing ability of melons to tendril onto any support they can find; the wild pandemic hairdo of potato vines that obscures the hidden tubers nestled deep in the ground; the surprise discovery of what appears to be—dare I hope it after the brutal demolition by the Rabbit Brigade?—a single sunflower plant with one, two, three, four, five buds about to blossom.

There is endless, irrefutable evidence of fruition. Things coming to be at long last.

As I walk in the garden, I find myself scratching my head and thinking, “Now, what can I make out of that?” Well, to begin with, there’s lots of salsa and gazpacho to be wrought from those obscenely huge heirloom tomatoes. And at least one dish of eggplant parmesan from the cluster of baby eggplants that appeared like a miracle when I had given up hope (never having grown eggplant before, so not understanding their shy nature). And there are a lot of good jokes to be made from the spiny cucumbers that hang like heavy elephant trunks from the trellises.

But apparently, I can also make a blog post out of the garden (which is not something they mention in the gardening books), because fruition happens. But not only in the garden.

As I think about fruition in my life…

I had three books come out this year. That’s never happened to me before. There will be two more next year, there is one more that’s been accepted for publication, one more that I’ve nearly finished writing, and three more ideas that I’m turning over and tilling in my mind. In mid-summer, my brain seems always to be working on the telling of something—a story, a poem, a joke, a blog post. I allow the word redolent to roll around in my mouth. I feast on plot and character and setting. I store away story ideas for the cold winter months ahead.

Fruition.

I’m building a small house in the woods in Maine. I’ve been going up there as often as possible to watch the impossible happen: space opened up, a foundation properly laid, the magic trick of a well that brings water up from the ground. I stood for hours watching the well digger work his machine. At seventy-six, he’s probably dug more than ten thousand wells, but this was my one and only, and I didn’t want to miss a single minute. When he struck water, after pounding through one hundred feet of solid ledge, a small piece of the ancient rock shot out, and he gave it to me, saying, “This is the rock that sits at your water table.” I’ve placed that rock on my writing desk, the proof of what can come up when you work hard enough at something and stick to it through the hours of not knowing. In the next few months, walls will rise, a roof will be pitched, doors will hang on their hinges. I’m already planning a small, slatted bench that will sit outside so that I can take off my muddy boots when I come in from the garden. What a thing to come to be.

Fruition.

In September, when the last of the tomatoes will be ripening and I’ll already have planted the fall-to-winter leafy greens—kale and spinach and swiss chard—that will carry me through to the wetness of next spring, my youngest child will move to France. We curl up on my bed, as we’ve done since she was an infant, and scout out apartments on the internet and imagine the route she’ll walk to work and practice our French (hers is quite good and mine is a funny-sad joke). I look at her, my youngest, and think, What a thing to come into being. Because all of us are was and is and will be, all at the same moment, but it’s a particular moment when a young person first launches into the world, a specific and peculiar confluence of all that ever was and everything that absolutely is and the whole of what might be. And as her mother, I hold all three of those beings in my mind as perhaps only I can, having been there from before the beginning and always thinking about her future, even before she was born.

We are rounding the corner into August, and summer will soon turn its back on us. But what a season of fruition it has been. My heart and mind and stomach are full of it. Until the last fruit drops from the rotting vine, I will continue to walk in the garden and think to myself, “Now, what can I make of that?”

May 9, 2021

Mother’s Day: I Gave Away My Children

I’ll start by saying that I had a lovely Mother’s Day thanks in part to my three terrific kids, all grown. Though two are away, I received wondrous moments of love from all: texts throughout the day, a living arrangement of plants delivered to my door, chocolate-chip cookies from my favorite bakery that quietly appeared on my desk. Lots of hugs from the one who’s home and fun videos, photos, messages, and calls from the ones who are away. I love my adult kids, and it’s really nice to know they like me, too.

But that’s not what this post is about. It’s about a chance I took on seeming ridiculous and the unexpected result of taking that chance.

First, I did do something ridiculous. In the dark months of January and February, nearly one year into the pandemic, amid the swirl of news stories about the virus variants that were spreading like California wildfires and the vaccines that were still months away—I planted way too many seeds on the grow rack in my basement. Yes, I’m one of those pandemic gardeners (there are worse things on earth) who took up gardening as if in a state of bacchanalian mania. I started planting things in 2020, had a beginner’s year filled with some successes and a lot of failures, and then returned in 2021 (What? The pandemic is still going on???) with just enough experience under my belt to make even more mistakes.

And the biggest mistake I made was planting way too much. Don’t judge me! The seeds are so little. How can plants even grow out of them (impossible!), let alone become too big to fit in my limited garden beds (inconceivable!)? And yet…

Plants do grow, and I had some hella crazy germination rates. Really, I don’t think this was normal.

In any case, I planted all my beds and planted twenty large pots and gave away a lot of seedlings to my sister, friends, next door neighbors, and writers group. And still. I had hundreds of extra seedlings: tomatoes, peppers, basil, eggplant, zinnias, sage, cucumbers. And that doesn’t even include the hundreds of flower seedlings on my back porch that need to be planted in my front beds once the weather gets warmer.

What to do? I couldn’t throw out these beautiful plants.

Look, it would be a lie to say that the seedlings were like my children—not even close—but I did germinate them and then tend to them twice a day for months. Lately, I’ve been carrying them in and out of the house to gently introduce them to the great big world. Okay, they’re kind of like my babies.

But it was time to plant them in the ground. And I had no more ground to give. Plus, everyone I knew had already taken what they wanted.

So, I decided to give them away. Early in the morning (7 am) on Mother’s Day, I set all of them out on my front lawn and invited the world to take them.

And take them they did. While I was still carrying plants out, a man drove by, stopped, and stepped out of his car with his four-year-old son, George. It turns out they were new to the neighborhood. George was silent but intrigued. He wore a tiger face mask. His father, Gregg, asked him quietly which of the plants he wanted, and he chose each one carefully, keeping a wary eye on me. The father and I were not wearing masks; we were outside and more than ten feet apart, plus I’m fully vaccinated. I couldn’t help but notice how nice it was to meet strangers and talk. And see their faces.

Another woman who was out walking stopped by. Her name was Rachael and she lived one street over. She confessed that she had tried gardening twice, but “failed” each time. Her voice was rueful. This led to a walking tour of the few raised beds I have on the side of the house. She asked for advice. I told her I was nearly as new to this as she was, but I also told her what I knew. She said, “I’m going to do this. I’m going to see it through. I’ve always wanted to do this.” She took a boxful of plants.

A woman with a lovely Old World accent came by pushing her four-week-old grandson in a stroller. She had gardened a lot in the country of her birth but had moved recently to help take care of the baby. She would love to start a garden here, but had no way to carry the plants home. Rachael, who was still selecting her own plants, offered to drive some plants to the woman’s house. They had never met before. Off they went.

People came and they came and they came. A young man who used to work on a farm and was out walking with his dad. A runner who jogged by and instagrammed my yard. A 91-year-old man who had spent his whole life gardening but now was unable to walk more than a few feet. He and his daughter were on the way to his wife’s grave. (I live next to a cemetery. Cool, huh?) We spent twenty minutes slowly touring the garden. He asked me out on a date. (I declined.) In the end, he took an eggplant seedling and a basil plant. His daughter said she would transplant the eggplant to a container and place it on a table on the porch so that he could tend it without bending over.

All this to say, I had more conversations with more strangers than I’ve had in the last fourteen months. And it felt great. By the end, all the plants were gone, and I like to think of the fruit that will be borne in the coming months. But mostly I’m just grateful for living proof that when given the chance people still want to get together and chat, talk about something they love, and share a little bit of their lives with each other. It’s been so darn long. It was just a lovely day filled with little miracle moments of connecting. Happy Mother’s Day, all.

April 26, 2021

A Pandemic Is a Terrible Thing to Waste

Now that we’ve arrived at this inflection point, when it feels like the curve of the universe might finally bend in a better direction, when we still have the metallic taste of fear in our mouths, but we’re beginning to feel the thawing trickle of hope in our hearts—while we are still in the muscly grip of the pandemic, but feel as though we’re finally flexing our own biceps with the vaccine—now is the time to ask: What do we make of this terrible year we’ve endured?

It’s no exaggeration to say that everyone is re-evaluating everything. The pandemic radically, swiftly, brutally upended every aspect of our lives, and now that we’ve been forced to accept what seemed impossible—namely that anything (including funerals) can be redefined, reimagined, reconfigured—we’re asking ourselves, What do we want to keep from this horrible experience? What’s the good that floated to the surface when the boat that was our Lives in the Before Times crashed against the rocky shore? What do we salvage from the wreckage and what do we let sink to a watery grave? Many of us made surprising discoveries of delight: more time with our kids, daily walks, less pressure to socialize too much, no commute. From exercise habits to better work/life balance to focus on family to working from home to an overall slower pace, everything is up for a complete vision overhaul. And that includes: school visits.

I’ve been doing a lot of virtual visits lately. (I just posted on my website four short clips that give a sense of what my visits are like, each with a different grade.) When I talk to teachers and administrators, I keep hearing different versions of the same question: Will in-person school visits come back, and if so when? Principals ask it of authors. Authors ask it of each other. I get the sense that principals are wondering when authors will be willing to return, while authors are wondering when our germy selves will be invited back. This mutually exclusive exclusion has all of us questioning the future.

It’s hard to imagine a time when schools will think it’s a good idea to cram three-hundred-and-fifty third-graders into a gym. And yet, this is how it was: hundreds of wiggling bodies sitting criss-cross-applesauce on an unswept cafeteria floor, so close their knees bumped, so close their shoulders were pressed together, so close they could reach forward and tap the shoulder of the child in the next row. I’m astonished that we did this without thinking. All of us, hundreds of us, in a room that was too small, with no open windows, breathing in and out, shouting, laughing, sneezing, coughing, so that by the end of the presentation, the air was thick with our collective funk. I remember times when the kids would come straight in from recess, sweaty and panting, and the windows would fog up with their youthful humidity.

And we all kept breathing, in and out.

(I think about the many times before the pandemic when I would enter a school and be told by a teacher, “Oh, there’s a terrible stomach bug going around—half the kids are out,” and then the rest of us would crowd into the gym for a presentation! I don’t know about you, but during this 14-month stretch of social distancing, I haven’t had so much as a cold. Not one cough. Not one fever. Not one sore throat. Not one runny nose. It’s something to ponder.)

So, I have trouble imagining in-person school visits returning anytime soon. But then again, I have trouble imagining going back to crowded movie theaters or tightly-packed restaurants or rush-hour elevators. It’s even hard to envision a grocery store with two-way aisles. So…maybe this is largely a failure of my imagination. Or maybe we’ll just never look at mass close contact in the same way again.

Meanwhile, principals are wondering about us: Will authors come back into the schools? Will they risk getting on a plane, staying in a hotel, riding in a taxi, shaking hands?

I have to report: A lot of my author friends are saying, Never again. I am never going back to in-person visits. And not just because of the risk of infection from all kinds of germs, but because virtual visits have so many advantages.

I did twenty-two virtual sessions for a school district in California this year. They scheduled presentations for Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, (not Thursday) and Friday. And then they wanted a single day two weeks later. And then at the last minute they added another single day separate from all the others. If we had followed that schedule for in-person visits, it would have required three roundtrip coast-to-coast flights—which would have been impossible. But, virtually, it was not only possible, it was actually easier.

One day this spring, I did a virtual visit in North Carolina in the morning, a virtual visit in a local town at midday, and a virtual visit in Pittsburgh in the afternoon. Easy.

There was one school that wanted me to do three sessions, but the morning was the only time that worked well for them. So, I visited with them at 8:30 am on Wednesday, 8:30 am on Thursday, and 8:30 am on Friday. No problem.

Another school called me three days before they wanted me to appear. Could I do it? they asked. Sure, I answered, slotting it in between a virtual doctor’s appointment and a phone call with my lawyer.

No travel costs. No packing. No hotel stays. No rental cars. No hassle. What’s not to like?

And yet…the kids. I miss the kids. I stare at the screen. I call them by name. I notice when its Dr. Seuss day and they’re all wearing funny hats and blue hair. I ask them about the weather and the time difference, and tell them what’s going on where I am. I ask them questions and answer theirs. I do everything short of reaching out with both hands, willing my fingers to break through the glass that divides us.

Sometimes I ask myself, what’s the difference, really, between being connected through a high-quality monitor with great sound and being there in person? The answer comes to me without even thinking: everything.

I will always do virtual visits, if for no other reason than that they make it possible for multiple schools to share a single session with me, thereby dropping the per-school cost to a fraction of my usual fee. It thrills me when five schools get together and I present to all of them at the same time. These are schools that don’t have the budget to fly me across the country and have me all to themselves, but now I’m talking to their kids, calling them by name, answering the questions they’ve always wanted to ask an author. It’s a great option and one of the truly good things to come out of this terrible year.

But in-person visits? Yeah. That’s in my future, too. I’ll come, bringing my germs with me, and eat cafeteria pizza in the library with the kids and probably catch a lot of colds and miss flight connections and long for my own bed. Can’t wait.

January 31, 2021

Match, Flame, Gasoline

Book promotion doesn’t usually require me to challenge the status quo, rethink every aspect of a well-known process, or question the very humanness of the human condition—but this year is different.

This year has been different in almost every way. And that’s a challenge for us humans. Evolutionarily, we don’t like change. For authors, who live within the tradition-bound, custom-heavy (let’s just say it: stodgy) ecosystem of publishing, it’s an especially steep hill to climb—particularly for those authors who have a book to promote. And while book promotion certainly isn’t the most critical of pandemic re-toolings, it does offer a close-up view of why we humans are so resistant to change and why this change was coming, whether we liked it or not. It just came faster.

I’m deep into book promotion right now because my next book, Sydney & Taylor Explore the Whole Wide World, will launch on February 2, 2021. (Groundhog Day! Perhaps you should buy multiple copies, just in case the day keeps repeating itself.)

Now, that sentence right there (and one could argue this whole blog post) is an example of book promotion in the time of Covid. It’s a way of getting the word out about my book without getting within six feet of another person, without leaving my house, and without physical contact. In other words, digital.

And that gets at the heart of the change, because book promotion in the past was always a very person-to-person process. The author would go on the road, pass through airports, be greeted by media escorts, share car rides, strike up random conversations, meet bookstore owners, greet the audience of readers, sign books, shake hands, chat one-on-one with book lovers, pose for photographs. There was a lot of touching in those days. A lot of physical closeness. Which one could argue was the whole point of the promotional tour. It was less about books sold at any one stop and more about building a chain of ongoing relationships and creating closeness within the larger book community. It was a way to break out of the writing bubble that most authors live in and infuse the passage of the private manuscript to the public book with warmth and intimacy.

But all that touching!

Believe me, I’m no germaphobe (my reaction to germs is more: “bring it on” so I can keep my immune system strong), but seen through the lived lens of Covid (going on one year now), it seems remarkable that we (regularly! unthinkingly! innocently!) made so many choices and spent so much money to effect so much close gathering of strangers in tight spaces, so much handing of objects back and forth (books, pens, phones, children!), and so much pressing of the flesh.

But that’s the human condition. We like to be close. We feed (all of us, to a lesser or greater extent) on human contact. And contact does mean contact.

Scott Galloway, professor of marketing at the NYU Stern School of Business, points out that the pandemic hasn’t changed things; that is, it hasn’t altered the course of events in terms of the trajectory that businesses were already on. It’s simply acted as an accelerant, moving us forward on the path we would have taken anyway in one giant leap. He argues that the result of the pandemic wasn’t to change where we were going in business. Instead, it simply accelerated the process; thus, because of the pandemic, we find ourselves exactly where we would have been—ten years into the future, but in a matter of merely eight weeks.

In other words, malls were dying anyway, and now they’re dead. Elite colleges and universities were reaching the limits of their ability to justify the obscene amounts they charge for a four-year education, and now students are turning away from them en masse. Working from home was always a good solution to a host of challenges, and now it’s suddenly gone from being a weird outlier to being the norm.

Within this framework, we can consider the conditions that existed before the pandemic (a need to cut greenhouse emissions, a desire for more time with family, a cultural movement away from materialism, etc.) as the match; the folks who heralded the need to pay attention to these conditions for years (Greta Thunberg, Catherine Jones, Marie Kondo) as the flame; and the pandemic as the gasoline—the accelerant that Scott Galloway notes pushed us forward ten years in just eight weeks.

All these things were going to happen anyway; the pandemic just cut ten years off the inevitable timeline. Which is no small thing.

Was book promotion always moving to a digital world of no contact? There are so many good reasons for making the switch to digital that have nothing to do with Covid:

I can’t tell you how many author friends have said to me in the past few months of the pandemic, “I really like being off the road. It’s so much less exhausting. And I get to be with my family.”

Digital book promotion saves money for publishers. A book tour that used to cost tens of thousands of dollars can now be put together for almost no money.

To that end, authors can set up their own far-flung book events, which is a boon for those who don’t get the marketing attention they deserve from their publishers.

It’s better for the environment to stay put. Greta Thunberg has opened our eyes to that truth.

The audience size is so much bigger. An event that might have attracted 15-20 people at a live, in-person venue, now attracts an audience of 150+ on a digital platform.

Digital promotion gives marketing departments more bang for the buck, because those digital gatherings have a great shelf life, living on as recordings that can be used as content for a variety of marketing purposes.

It’s a more efficient use of time for authors. I can be cooking soup, pop over to do a book event on my computer, and then eat the perfectly simmered soup for dinner.

We’re all spending a lot less money on clothes: one good shirt does the trick—pants be damned.

Bottom Line: More people are actually hearing about new books. My virtual Tai Chi class, which could accommodate a maximum of 25 people when we met in person in the studio, regularly has up to 185 attendees from all over the world, including Denmark, Hawai’i, Hong Kong, and the Arctic Circle. People who would have had to fly in to attend a book event can now show up after mowing the lawn and before helping their kids with their homework. It’s a brave new world.

A couple of nights ago, I was a presenter at HarperCollins Children’s Summer Showcase, promoting another book that’s coming out this year: Bubbles…UP!, which pubs on May 4, 2021. (Ha ha! There’s another example of digital book promotion. Two for two!) Normally, the authors and the booksellers would have all been in one room. This time, we were in hundreds of rooms, in different time zones, wearing who knows what from the waist down. The author from Scotland told us it was 2 AM where she was. I marveled that she had her hair combed, her lipstick on straight, and was speaking in complete sentences.

Introducing the event, Harper’s VP of Marketing and Publicity, Nellie Kurtzman, called attention to the strangeness of it all:

We’re still in such a weird world, but this is our third time doing these seasonal showcases [virtually] and I think it’s a weirdly distanced yet intimate way to let you know about what we have coming up…and I would say we’ll probably do this even past pandemic times.

Weirdly distanced, yet weirdly intimate. I feel this in so many virtual adaptations of “normal” life. My meetings with business colleagues, my therapy sessions, my school visits. We see each other’s bedrooms. We see each other’s lunches. We see each other’s beginning-to-slip-into-dementia elder parents wandering onto the screen and demanding an Oreo. It doesn’t get much more intimate than that.

And “we’ll probably do this even past pandemic times,” because…it makes sense for all the right reasons and now seems so obvious and…normal.

And yet.

And yet, would I opt for this change in book promotion, even if the pandemic had never happened? Is this the trajectory, inevitable perhaps, that I would have chosen? There are so many good reasons to go digital.

I don’t know. I miss all of you. As I contemplate a robust book event schedule (please sign up for my newsletter for all the latest info on when I’ll be appearing digitally to introduce my newest books, as well as to receive fun giveaways. Ha ha! Three for three promotion hits!), I know that I’ll feel bereft, not seeing your faces; not posing for pictures; not answering your personal questions, whispered in that quiet space we create as we bend over the book I’m signing for you. That brief moment in the book-signing process when only the two of us exist: you excited to receive my new book personally signed by me, and me signing that book—just for you.

I’ll even miss the crunchy airplane rides and making small talk with the media escorts, who really do have some whack-a-doodle stories to tell of their years driving celebrities around. I’ll miss all the strange and interesting cities and towns I would have seen with my own eyes and all the strange and interesting encounters with people who don’t live within my house.

But Greta Thunberg is right. And Scott Galloway is right. And my Tai Chi teacher is right in saying, “Do nothing, and everything gets done.”

So, I jump in with both feet, excited as ever to share my new books with the world, a little nostalgic for the old ways, but ready to face the accelerated future and seek new adventures and experiences in whatever form they might come. I hope to see you through the digital looking glass soon.

September 8, 2020

The Spy Who Sold Me

Of course I know that internet companies collect my data and sell it for profit. We all know this. Sometimes, though, it’s hard to appreciate what this means on a personal level.

And then, sometimes it’s not.

I was reading an article last week in the New York Times about all the international spying that’s going on right now related to the development of a vaccine for the novel coronavirus.

Oddly, it was the banner ads more than the article itself that made me think about spying. The New York Times, like many online news sources, forcibly interrupts your reading with ads that slash across the full width of the page, forcing you to “jump over” the intrusive ad to continue.

(I admit, when I come across these barrier ads, I’m reminded of the classic folktale of the old woman who found a crooked sixpence and decided to buy a pig, only to learn on the way home that the piggy wouldn’t jump over the stile. Whenever I hit one of those speed-bump ads, I feel like the stubborn little piggy who refuses to jump. Vive la résistance!)

The first ad was a row of books for sale. Nothing too surprising there; I’m a writer and I buy a lot of books. Anyone could guess that. But the weird thing about the ad was that the first book in the row was one I had just purchased online that day. The other books were tagged as “HOT” or “NEW.”

Banner ad #1

The advertising ploy worked: my eye instantly went to the cover I recognized, because it was one I had chosen myself, and then just as automatically trailed along the row to read the other titles. The ad never explicitly said, ‘You liked this first book enough to buy it, so you will probably like these other books as well,’ but it’s an implied and readily-absorbed message. The ad did its job: it got me to look at those books in an altered state, a more receptive state, a state of mind that inclined me to believe I would like those other books.

What freaks me out about this ad is the manipulative way the company used my own feelings, my own choices, my own desires to try to sell me stuff. I was also heebie-jeebied by the speed of it all; I had bought the book just hours earlier.

The second ad was notable because it’s been trailing me for years.

Banner ad #2

About seven years ago, a friend convinced me to try Stitch Fix, the online “personal styling” subscription service that chooses clothes for you. I tried it for one month, it wasn’t for me, and I cancelled my trial subscription. Seven years later, they’re still hoping to win me back.

If there was ever a time to invoke the foundational phrase from the 2009 movie He’s Just Not That Into You, this would be it. Believe me, Stitch Fix, I will never sign up for your service again. It was just a fling. A poor and impulsive choice. Please don’t take it too hard. It’s not you. It’s me. I have long-standing issues with clothes. I’m not in a place where I feel ready to make a commitment. I just ended a long-term relationship with another subscription business. So please, let it go. It’s been seven years since I’ve shown any interest in you. Have some dignity. Have some self-respect.

Break-ups are hard, but this one is ridiculous. Who made a computer algorithm that rests on the belief that someone who signed up for a service on a whim and then cancelled after one month is likely to sign up again—seven years later? Come on, coders, you can do better than that.

The last ad is perhaps the creepiest (and funniest) of them all.

A little background. Last year I bought a small wooded piece of land in Maine with no house on it. In order to build a house, I needed a construction road built from the main road down to the site. Enter Bill, an extraordinarily talented excavator who has been moving and shaping earth for more than fifty years. When I stopped by the land to see how things were going, Bill explained, with the simplicity and accent of an Old Mainer, “I took a bush hog down there and cleared out all the crap.”

I had no idea what a bush hog was, and Bill offered no explanation. What sprang into my mind was a pig, or perhaps a herd of pigs, let loose by Bill onto the land. Pigs who then neatly and completely devoured everything in sight, leaving a lovely, level spot to build a house. “Good little piggy,” said the old woman with the crooked sixpence.

At some point, I must have Googled ‘bush hog.’ I must have, though I don’t remember doing it.

But I must have. Because the third ad interrupting the spy article was from a company selling bush hogs. (I finally got to see what one looks like! It’s much redder than I had imagined.)

Banner ad #3

Which means that there’s a computer algorithm out there that rests on the belief (hope?) that anyone who would Google ‘bush hog’ just once must want to own one. This computer algorithm clearly doesn’t take into account the weird perambulations of an author’s mind: We Google everything.

So, what’s the point of this blog post? I started out by saying that I already know, as you already know, that our personal information is tracked, stored, and sold for profit in an attempt to get us to buy stuff. What surprised me though, was the speed with which these efforts take place (I just bought the book a couple of hours ago), the comprehensiveness of these efforts (I Googled ‘bush hog’ once, maybe?), and the longevity of these efforts (Give it up, Stitch Fix. Ain’t gonna happen.).

It doesn’t escape my notice that these disturbing ads appeared in the middle of an article on global spying. No need to look to Russia and China for invasive, civil-rights-denying, privacy-eroding attacks; they’re happening right here in our own homes.

In his book Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now, virtual reality scientist Jaron Lanier points out that advertising has been around for a long time, and advertisers have always used every weapon in their arsenal to try to get us to buy stuff. But Lanier also points out that advertising was never particularly effective and not nearly as efficient and cheap—until Big Tech learned how to use our own information against us. Our own selves turned against our own selves. When I think about it, it’s kind of like the way the novel coronavirus exploits our own immune system to wreak havoc in our bodies.

Lanier isn’t a fringe alarmist, and neither am I. These personalized ads are creepy. They just are. It’s disturbing to think that I could be sitting in my bedroom, in my pajamas, writing a blog post that causes me to Google the folktale “The Old Woman and Her Pig,” and for the next ten years I’ll be trailed by ads for cosmetics that promise to make me look younger and by ads from farms that sell pigs for a sixpence.

I’ll tell you how it feels. I don’t remember searching Google for ‘bush hog’, so it feels as though the internet went straight into my brain and extracted one of my thoughts. And then that thought raced through those internet “tubes” that Alaska Senator Ted Stevens so famously described, and all those tubes—connected to an infinite number of other tubes —finally connected to a company I’ve never heard of that launched an advertising attack on me with weapons so finely designed I didn’t even realize I was under attack.

George Orwell’s 1984 presaged an era of surveillance. But surveillance by camera seems quaint these days. Today, we surveille ourselves simply by existing. With more people wearing computerized glasses and watches, carrying (phone) trackers, oversharing on social media, and inviting Alexa into their homes to eavesdrop and then take action without authorization (because it’s convenient), it isn’t hard to imagine the worlds described in the book Feed (M.T. Anderson, 2002) or the movie Minority Report (also 2002), where in order to preserve yourself as a distinct entity, you need to rip out some piece of your physical body and destroy it. (Hello, The Matrix.) And has anyone noticed that the law-and-order chaos of Robocop (1987) seems like it’s happening on our streets today, except without the hilarity of the clunky CGI?

Forget about clearing your browser history to protect your privacy. It’s gotten to the point where you need to wipe clean your entire mind. No thought is safe. No thought belongs just to you. No thought can exist without invasive action following. The problem isn’t that the New Technology is coming for us, fast and furious; it’s that it’s already here.

And that’s not just creepy. It’s terrifying.

August 26, 2020

Quiet, Please

I’m thinking about quiet.

Which means I’m also thinking about chaos.

Because it’s impossible to think about any concept without considering its opposite—even if that consideration takes place below the level of consciousness. For example, when you finish a meal and appreciate that feeling of fullness and satisfaction—satiety—you’re also (inescapably) thinking about hunger, even if the thinking takes the shape of how good it feels not to be hungry. You have to be thinking about hunger, because fullness has no meaning without the concept of hunger.

Just as light has no meaning without the experience of darkness.

Happiness becomes senseless without sorrow.

I’m thinking about quiet because of the pandemic. It was reported in the journal Science that the world has experienced an historic quieting. In a coordinated project, seismologists around the world measured human noise from March through May of this year and found that the din created by humans has dropped 50%. “The length and quiescence of this period represents the longest and most coherent global seismic noise reduction in recorded history,” they concluded.

(Can we take a moment and appreciate the euphonic beauty of the word “quiescence”? The lovely repeated soft ‘e’ sounds, and the susurus of the two ‘s’ sounds? Please, take a moment and say the word out loud: quiescence.)

Did you know that human noise can be felt in the bedrock of the Earth? Heavy traffic, football games, jackhammers, industrial blasting, rock concerts, subways, fireworks, factories—all register on the same equipment designed to detect earthquakes and other tectonic activity.

For those of us who naturally like quiet, these would seem to be the best of days (if only they weren’t the worst of days). We are allowed to enjoy the quiet, aren’t we?

Except that there are a few strange phenomena attached to this particular quiet.

The first is that it contributes to the time-disconnection that so many of us have been feeling. Who knows what day it is, anymore? The hours blur, the days blur, the weeks and months blur. And this, in part, is due to the quiet. It turns out that hours, days, weeks, months have different and predictable levels of noise associated with them. Microphones on once-busy city streets around the world have recorded the sound of the pandemic, and the sound is an unchanging, undifferentiated quiet. “The rhythm of the week—Mondays louder than Sundays—has disappeared,” reports an article in the New York Times.

Another unwanted attachment to this quiet is the sadness that accompanies it, like the quiet at a funeral. One of the scientists on the pandemic noise project noted, “It’s the sound of the city aching. It’s not a healthy sound in my mind.” Context matters. So, while the decibel level in the woods on a snowy evening might be the same as that of the eerie quiet between mortar shellings in the Battle of the Somme during World War I, the experience of the quiet is entirely different.

Akin to this altered experience of quiet is the fact that cities are not meant to be quiet. And so the silence of an empty street in New York City on a Tuesday evening becomes ominous, because it doesn’t match the pattern of our thinking about a city street. And the quiet is a very loud reminder of our altered lives. The quiet shouts within us, “I am sick. I am unemployed. I am isolated. I am afraid.” It’s hard to welcome quiet when it carries such heavy baggage.

Arline Bronzaft is an environmental psychologist who has spent years studying noise pollution. She explains, “People have said they miss the sounds of New York City. They miss the honking horns, the crowds. And they would probably be the first people who were critical of those sounds. But it’s not that they miss them. They miss their lives.”

And so we return to context. Quiet—blissful, blessed, long-desired quiet—has been transmuted into a void within us. The word ‘chaos’ in English is derived from the ancient Greek word ‘κενος ’, which means ‘void.’

Quiet and chaos. In this time of the pandemic, you don’t get one without the other.

I don’t live in a city. I live in a densely populated suburb of Boston, a commuter town twelve miles outside the city limits, on a quarter-acre plot of land with a thin strip of woods behind it. For me, the quiet isn’t ominous. It doesn’t make my heart ache with sadness. It isn’t a void.

I’m one of the lucky ones. I’ve always worked from home, and I continue to work and earn money from the relative security of my house. I live with my kids—college-age adults—and so I don’t suffer from isolation. I’ve been able to spend time in my backyard, gardening and socializing with friends (10 feet apart), or meeting them in their backyards, chatting with my neighbors whose backyard flows unimpeded into mine, neither of us entirely sure where the boundary line exists. And perfectly happy to leave it that way. Last evening, there was a full Klezmer band rehearsing in my neighbor’s backyard, each musician socially distanced, together making wonderful music.

I’m one of the lucky ones who can embrace the quiet, enjoying the revealed song of birds, the sighting of a stealthy fox on my lawn, the twice daily perambulations of roving bands of wild turkeys that have decided they own the town.

‘Cacophony’ comes from the Greek words ‘κακος ’ (bad) and ‘φωνη’ (voice or sound). Bad sound. When did quiet become a bad sound?

When it became the echo of more than 800,000 lives lost in this world with no clear end in sight.

And how have New Yorkers chosen to forcibly beat back the virus every evening at 7 o’clock?

They make noise.

References

“The Coronavirus Quieted City Noise. Listen to What’s Left,” by Quoctrung Bui and Emily Badger, New York Times, May 22, 2020.

“With Covid-19, a Seismic Quiet Like No Other,” by William J. Broad, New York Times, July 23, 2020.

July 23, 2019

Who Doesn’t Like Pie?

Today, we celebrate pie!

I love pie, don’t you? Especially in the summer.

Blueberry. Key lime. Plum. Revenue.

Revenue? Oh, I know you’re probably thinking Yuck, revenue pie sounds disgusting. But it isn’t. Because if you get a big enough slice of revenue pie and the revenue pie is tasty enough (that is, has value), then you can go and buy as much blueberry, key lime, and plum pie as you want. You can also pay the mortgage, get the car fixed, and put braces on your kid. Revenue pie, it turns out, is the best pie of all.

I’m going to focus today’s post on just one kind of revenue pie: the deep-discount pie—not to be confused with a deep-dish pie. (Sigh. So many pies, so little time.)

I balk at the traditional designations of “regular” sales versus “deep discount” sales (also called “special” sales and “high discount” sales), because today’s (unhappy) truth is that “deep discount” sales have become as “regular” as any kind of sale for most publishers. They are no longer “special,” the strange outlier; for many books, “deep discount” sales make up a significant number—sometimes the largest part—of total units sold.

So, they’re important, and the terms in your contract surrounding “deep discount” sales can have a huge effect on your bottom line—your slice of the publishing pie.

I’m going to use actual numbers from the sales of one of my titles and graphics (in pie charts!) to illustrate a couple of important points about “deep discount” sales.

But for now, here’s a super easy way to understand the fundamental difference between “regular” sales and “deep discount” sales.

First, a few basics about retail. Like all retail businesses, the wholesaler (the publisher) sells the product (the book) to retailers (bookstores or other outlets) that then sell the product (the book) to customers (the readers). Unlike most retail businesses, every book has a list price printed on the cover. The list price is the price that the retailer (the bookstore) typically charges the customer (the reader) for the product (the book).

How does this work in publishing? Publishers charge the bookstores less than the list price for the book; otherwise, the bookstore couldn’t make a profit and so couldn’t pay its rent, utility bills, salaries, and so on—the expenses it needs to cover in order to stay in business. So, publishers sell every book to bookstores (and other retailers) at some discount off the list price, and this discount varies from 40% off the list price to 85% off the list price.

That’s a big jump, isn’t it? From 40% to 85% is a significant portion of the pie.

Somewhere in that 40–85% range, a publisher designates a breakpoint—a line set by the publisher that divides the “regular” sales to a bookstore from the “deep discount” sales to a bookstore. For Publisher A, that breakpoint might be 51%; for Publisher B, that breakpoint might be 54%; for Publisher C, that breakpoint might be 60%. I have seen with my own eyes all of these breakpoints in actual contracts for children’s books from top-tier publishing houses on contracts signed within the last year. So, there is great variation between houses and even within houses regarding the definition of what a “deep discount” sale actually is. It’s a fluid concept.

Why is this breakpoint important?

Because at this breakpoint the entire payment structure for how you, the author, are paid, changes radically. For sales at or below the breakpoint, you are paid a percentage of the list price—which doesn’t change. But when you exceed the deep discount breakpoint, you are paid a percentage of the net amount received (in other words, the list price less the discount, also simply called “net”). The greater the discount, the lower the net amount received, and thus the less money you receive for that sale.

Let’s take an example and see how this affects the amount of money you, the author, receive for the sale of your book. For this example, let’s assume four things:

The list price of your (paperback) book is $8.00.

Your regular paperback royalty is 10% of list.

The breakpoint in your contract (that divides “regular” sales from “deep discount”) is 54%.

Your contract says that for “deep discount” sales, you will receive 5% of net.

For a book that your publisher sells to a bookstore for 54% off the list price, you will receive your regular royalty, which is 10% of $8.00 = 80¢. This is a “regular” sale.

For a book that your publisher sells to a bookstore for 55% off the list price (above the breakpoint), you will receive 5% of net, which is [5% of (45% of $8.00)] = 18¢. (The 45% is what’s left over after the 55% discount has been deducted from the list price; i.e., “net.”) This is a “deep discount” sale.

It doesn’t take a PhD in mathematics to understand that there’s a big difference between 18¢ and 80¢. And when this difference is applied over multiple sales over multiple years, the loss in revenue to you grows. Quickly and devastatingly. “Deep discount” sales result in significantly lower revenues for authors in the short run and in the long run.

In its landmark survey that revealed the decline of authors’ income over the past ten years, the Authors Guild considered the following to be the principal causes of the loss of revenue to authors:

… the growing dominance of Amazon over the marketplace, lower royalties and advances for mid-list…including the extremely low royalties paid on the increasing number of deeply discounted sales and the 25 percent of net ebook royalty. [emphasis mine]

I discussed this survey in an earlier blog post, Power…And Money. It’s critical for authors to understand that even a single percentage point up or down on the breakpoint (for example from 51% to 52%) can make a huge difference in how much money ends up in your pocket. (Think about how you might shop for a mortgage, where even an eighth of a percentage point makes a difference over the life of the loan. It’s the same with the breakpoint defining “regular” versus “deep discount” sales if your book remains in print over a period of time. It adds up.)

So how, as authors, can we mitigate the loss of “deep discount” sales and maximize our revenues? How can we ensure that our backlist titles will generate solid income? (For more on the importance of the backlist, read my post Backlist to the Future.) And why aren’t we talking about pie anymore??? (Don’t worry, pie is just around the corner. Hang in there!)

We have to do two things to control the hemorrhaging of revenue that typically occurs around “deep discount” sales: (1) push that breakpoint as high as we can during contract negotiations so that as many sales as possible earn our full royalty; and (2) negotiate a higher percentage of net that we receive on sales above that breakpoint.

Our goal is to keep as many sales as possible in the “good” slice of the pie (full royalty) and for those that do fall into the “bad” slice of the pie (deep discount), make that slice yield more taste (value).

To be clear: “deep discount” sales don’t have to be bad, as long as their numbers are controlled and you receive a decent slice of the revenue pie on every “deep discount” sale. It can be wonderful to sell 5,000 copies of your paperback at a “deep discount’—as long as you’re not earning 18¢ per copy.

Recently, I renegotiated a contact for a backlist title that has sold well over the years. The contract was old and outdated, and I wasn’t happy with some of the terms. My publisher was willing to work with me to find a way we could both be happy with the contract, and I’m glad that we were able to work together to reach new terms. One important focus for me was “deep discount” sales.

I negotiated on two fronts: raising the breakpoint from 54% to 60% and raising the percentage of net paid on each sale above the breakpoint from 10% to 20%. This means I achieved both goals listed above: (1) I pushed the breakpoint up six percentage points thus keeping more sales in the “good” slice of pie; and (2) I negotiated a doubling of the amount I receive on sales above that breakpoint, meaning the “bad” slice of pie would yield more money.

I’ve now had 18 months of sales to review since the changes in terms took place, which means I can compare the effects of the new terms—the actual bottom line.

The first thing to note is that the change in terms did not result in a loss of sales; in fact, there was a modest increase in sales (8.4%) from before I renegotiated the terms. I don’t think the change in contract terms had any effect on the number of books sold.

But there’s a critical difference in the before and after of renegotiating the contract (and here comes the pie!):

Watch how the full-royalty slice of pie grows as the breakpoint in my contract rises six percentage points.

By raising the breakpoint in my contract for the dividing line between “regular” sales and “deep discount” sales, I shifted a significant number of sales from the “deep discount” category into the “regular” sales category. “Regular” sales will always earn you more revenue than “deep discount” sales, so you always want to increase the size of the “regular” sales slice of pie.

So, at this point, without selling more books, I’m earning more money. Just by raising that breakpoint.

But then I also made that After slice of pie (the 36% that represents “deep discount” sales) “tastier” by doubling the amount of money I get for each sale from 10% of net to 20% of net.

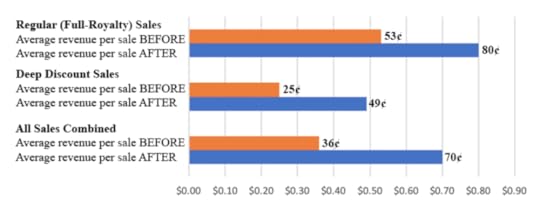

Here’s a bar chart that shows a comparison of revenue with the old contract terms (BEFORE) and the new contract terms (AFTER):

Comparison of revenue per sale for different categories (“regular” and “deep discount”) and combined overall that shows the difference in revenue generated by my old contract terms and my new contract terms.

One more thing I want to add is that I was successful in having the terms “deep discount” and “regular” removed from my contract. In today’s publishing industry, sales are sales, and “deep discount” sales are as regular as “regular” sales. In my contract, we distinguish between sales that pay a percentage of list price versus sales that pay a percentage of net as “books that sell at a discount of 60% or less” and “books that sell at a discount greater than 60%.” There is no separate paragraph in the contract that distinguishes “deep discount” sales from “regular” sales. The new terms say what they mean, and don’t employ anachronistic euphemisms to mask the true meaning (and consequences) of these sales. The old terms don’t make sense in today’s publishing industry, and they’ve been used to the detriment of the author.

If, after reading this post, you’re saying to yourself, “But it’s just pennies!”, you have to consider how those pennies add up over time, just as interest on a mortgage adds up to a surprisingly large amount over a 30-year period. So, using this particular book of mine, which has sold reasonably well as a backlist title over more than a decade: if, for the past ten years, I had had the contract terms related to “deep discount” books that I have now, I would have earned an additional $397,960 above and beyond the revenue I received for sales of this title. Pennies add up.

And if you’re saying, “But I don’t sell as many books as you do,” then you’re missing the point of this post, which is not about whether I sell more or less than anyone else. It’s about how each of us, in the space we occupy in the publishing ecosystem, can each tend our own garden and nurture growth. And growth in revenue—on whatever scale—is possible for every individual writer. Educate yourself. Read your contracts. Review your royalty statements. Talk openly with other writers. Make yourself smarter. Declare your value to yourself. Dare to ask for what you want. Live and learn.

“Take care of the pence; for the pounds will take care of themselves.”

—William Lowndes, British Secretary of the Treasury, 1696–1724

I would add, take care of the pennies, and you’ll be able to buy as much pie as you like!

Who Doesn't Like Pie?

Today, we celebrate pie!

I love pie, don’t you? Especially in the summer.

Blueberry. Key lime. Plum. Revenue.

Revenue? Oh, I know you’re probably thinking Yuck, revenue pie sounds disgusting. But it isn’t. Because if you get a big enough slice of revenue pie and the revenue pie is tasty enough (that is, has value), then you can go and buy as much blueberry, key lime, and plum pie as you want. You can also pay the mortgage, get the car fixed, and put braces on your kid. Revenue pie, it turns out, is the best pie of all.

I’m going to focus today’s post on just one kind of revenue pie: the deep-discount pie—not to be confused with a deep-dish pie. (Sigh. So many pies, so little time.)

I balk at the traditional designations of “regular” sales versus “deep discount” sales (also called “special” sales and “high discount” sales), because today’s (unhappy) truth is that “deep discount” sales have become as “regular” as any kind of sale for most publishers. They are no longer “special,” the strange outlier; for many books, “deep discount” sales make up a significant number—sometimes the largest part—of total units sold.

So, they’re important, and the terms in your contract surrounding “deep discount” sales can have a huge effect on your bottom line—your slice of the publishing pie.

I’m going to use actual numbers from the sales of one of my titles and graphics (in pie charts!) to illustrate a couple of important points about “deep discount” sales.

But for now, here’s a super easy way to understand the fundamental difference between “regular” sales and “deep discount” sales.

First, a few basics about retail. Like all retail businesses, the wholesaler (the publisher) sells the product (the book) to retailers (bookstores or other outlets) that then sell the product (the book) to customers (the readers). Unlike most retail businesses, every book has a list price printed on the cover. The list price is the price that the retailer (the bookstore) typically charges the customer (the reader) for the product (the book).

How does this work in publishing? Publishers charge the bookstores less than the list price for the book; otherwise, the bookstore couldn’t make a profit and so couldn’t pay its rent, utility bills, salaries, and so on—the expenses it needs to cover in order to stay in business. So, publishers sell every book to bookstores (and other retailers) at some discount off the list price, and this discount varies from 40% off the list price to 85% off the list price.

That’s a big jump, isn’t it? From 40% to 85% is a significant portion of the pie.

Somewhere in that 40–85% range, a publisher designates a breakpoint—a line set by the publisher that divides the “regular” sales to a bookstore from the “deep discount” sales to a bookstore. For Publisher A, that breakpoint might be 51%; for Publisher B, that breakpoint might be 54%; for Publisher C, that breakpoint might be 60%. I have seen with my own eyes all of these breakpoints in actual contracts for children’s books from top-tier publishing houses on contracts signed within the last year. So, there is great variation between houses and even within houses regarding the definition of what a “deep discount” sale actually is. It’s a fluid concept.

Why is this breakpoint important?

Because at this breakpoint the entire payment structure for how you, the author, are paid, changes radically. For sales at or below the breakpoint, you are paid a percentage of the list price—which doesn’t change. But when you exceed the deep discount breakpoint, you are paid a percentage of the net amount received (in other words, the list price less the discount, also simply called “net”). The greater the discount, the lower the net amount received, and thus the less money you receive for that sale.

Let’s take an example and see how this affects the amount of money you, the author, receive for the sale of your book. For this example, let’s assume four things:

The list price of your (paperback) book is $8.00.

Your regular paperback royalty is 10% of list.

The breakpoint in your contract (that divides “regular” sales from “deep discount”) is 54%.

Your contract says that for “deep discount” sales, you will receive 5% of net.

For a book that your publisher sells to a bookstore for 54% off the list price, you will receive your regular royalty, which is 10% of $8.00 = 80¢. This is a “regular” sale.

For a book that your publisher sells to a bookstore for 55% off the list price (above the breakpoint), you will receive 5% of net, which is [5% of (45% of $8.00)] = 18¢. (The 45% is what’s left over after the 55% discount has been deducted from the list price; i.e., “net.”) This is a “deep discount” sale.

It doesn’t take a PhD in mathematics to understand that there’s a big difference between 18¢ and 80¢. And when this difference is applied over multiple sales over multiple years, the loss in revenue to you grows. Quickly and devastatingly. “Deep discount” sales result in significantly lower revenues for authors in the short run and in the long run.

In its landmark survey that revealed the decline of authors’ income over the past ten years, the Authors Guild considered the following to be the principal causes of the loss of revenue to authors:

… the growing dominance of Amazon over the marketplace, lower royalties and advances for mid-list…including the extremely low royalties paid on the increasing number of deeply discounted sales and the 25 percent of net ebook royalty. [emphasis mine]

I discussed this survey in an earlier blog post, Power…And Money. It’s critical for authors to understand that even a single percentage point up or down on the breakpoint (for example from 51% to 52%) can make a huge difference in how much money ends up in your pocket. (Think about how you might shop for a mortgage, where even an eighth of a percentage point makes a difference over the life of the loan. It’s the same with the breakpoint defining “regular” versus “deep discount” sales if your book remains in print over a period of time. It adds up.)

So how, as authors, can we mitigate the loss of “deep discount” sales and maximize our revenues? How can we ensure that our backlist titles will generate solid income? (For more on the importance of the backlist, read my post Backlist to the Future.) And why aren’t we talking about pie anymore??? (Don’t worry, pie is just around the corner. Hang in there!)

We have to do two things to control the hemorrhaging of revenue that typically occurs around “deep discount” sales: (1) push that breakpoint as high as we can during contract negotiations so that as many sales as possible earn our full royalty; and (2) negotiate a higher percentage of net that we receive on sales above that breakpoint.

Our goal is to keep as many sales as possible in the “good” slice of the pie (full royalty) and for those that do fall into the “bad” slice of the pie (deep discount), make that slice yield more taste (value).

To be clear: “deep discount” sales don’t have to be bad, as long as their numbers are controlled and you receive a decent slice of the revenue pie on every “deep discount” sale. It can be wonderful to sell 5,000 copies of your paperback at a “deep discount’—as long as you’re not earning 18¢ per copy.

Recently, I renegotiated a contact for a backlist title that has sold well over the years. The contract was old and outdated, and I wasn’t happy with some of the terms. My publisher was willing to work with me to find a way we could both be happy with the contract, and I’m glad that we were able to work together to reach new terms. One important focus for me was “deep discount” sales.

I negotiated on two fronts: raising the breakpoint from 54% to 60% and raising the percentage of net paid on each sale above the breakpoint from 10% to 20%. This means I achieved both goals listed above: (1) I pushed the breakpoint up six percentage points thus keeping more sales in the “good” slice of pie; and (2) I negotiated a doubling of the amount I receive on sales above that breakpoint, meaning the “bad” slice of pie would yield more money.

I’ve now had 18 months of sales to review since the changes in terms took place, which means I can compare the effects of the new terms—the actual bottom line.

The first thing to note is that the change in terms did not result in a loss of sales; in fact, there was a modest increase in sales (8.4%) from before I renegotiated the terms. I don’t think the change in contract terms had any effect on the number of books sold.

But there’s a critical difference in the before and after of renegotiating the contract (and here comes the pie!):

Watch how the full-royalty slice of pie grows as the breakpoint in my contract rises six percentage points.

By raising the breakpoint in my contract for the dividing line between “regular” sales and “deep discount” sales, I shifted a significant number of sales from the “deep discount” category into the “regular” sales category. “Regular” sales will always earn you more revenue than “deep discount” sales, so you always want to increase the size of the “regular” sales slice of pie.

So, at this point, without selling more books, I’m earning more money. Just by raising that breakpoint.

But then I also made that After slice of pie (the 36% that represents “deep discount” sales) “tastier” by doubling the amount of money I get for each sale from 10% of net to 20% of net.

Here’s a bar chart that shows a comparison of revenue with the old contract terms (BEFORE) and the new contract terms (AFTER):

Comparison of revenue per sale for different categories (“regular” and “deep discount”) and combined overall that shows the difference in revenue generated by my old contract terms and my new contract terms.

One more thing I want to add is that I was successful in having the terms “deep discount” and “regular” removed from my contract. In today’s publishing industry, sales are sales, and “deep discount” sales are as regular as “regular” sales. In my contract, we distinguish between sales that pay a percentage of list price versus sales that pay a percentage of net as “books that sell at a discount of 60% or less” and “books that sell at a discount greater than 60%.” There is no separate paragraph in the contract that distinguishes “deep discount” sales from “regular” sales. The new terms say what they mean, and don’t employ anachronistic euphemisms to mask the true meaning (and consequences) of these sales. The old terms don’t make sense in today’s publishing industry, and they’ve been used to the detriment of the author.

If, after reading this post, you’re saying to yourself, “But it’s just pennies!”, you have to consider how those pennies add up over time, just as interest on a mortgage adds up to a surprisingly large amount over a 30-year period. So, using this particular book of mine, which has sold reasonably well as a backlist title over more than a decade: if, for the past ten years, I had had the contract terms related to “deep discount” books that I have now, I would have earned an additional $397,960 above and beyond the revenue I received for sales of this title. Pennies add up.

And if you’re saying, “But I don’t sell as many books as you do,” then you’re missing the point of this post, which is not about whether I sell more or less than anyone else. It’s about how each of us, in the space we occupy in the publishing ecosystem, can each tend our own garden and nurture growth. And growth in revenue—on whatever scale—is possible for every individual writer. Educate yourself. Read your contracts. Review your royalty statements. Talk openly with other writers. Make yourself smarter. Declare your value to yourself. Dare to ask for what you want. Live and learn.

“Take care of the pence; for the pounds will take care of themselves.”

—William Lowndes, British Secretary of the Treasury, 1696–1724

I would add, take care of the pennies, and you’ll be able to buy as much pie as you like!

July 15, 2019

Backlist to the Future

Here are three facts about publishing that you may or may not know. I think it’s worth considering each on its own, but then also how they relate to one another and how they connect back to the point I raised in my recent blog post “Power…and Money,” namely that American authors have seen their writing income decline by 42% over the past decade.

Fact #1: For the large publishing houses, profits from their backlist cover their day-to-day operating costs.“Most new books are only about a third as profitable as backlist titles. The big publishers can gear their businesses in such a way that the cost of all their operations are covered by the profits from the backlist, allowing them to run their new books programme more like a spread bet.” [1]

Think of that: backlist titles (those are your books, however small your royalty checks may be) are three times as profitable as most new books. How can that be? Well, remember there’s an active culling process, because plenty of books never make it to the backlist; they go out of print within the first eighteen months of their pub date. So any book that is on the backlist is, by its very existence, still selling to some profitable degree. It might not be selling a record amount, but it’s still selling enough to justify the house keeping it in print. (It also might be generating sublicensing revenue.) All this, after every expense (except warehousing) has been recouped. So, if you have a book that’s more than a year-and-a-half old and it’s still in print, take a bow. It’s not an exaggeration to say that you’re holding up the whole publishing ecosystem. Sort of like bugs. So small and easy to overlook, but without them, we’d all be dead. [2]

So, it’s the backlist that keeps the publishing houses in business. Not the big, new, splashy titles that everyone’s talking about (or all the other new-but-not-splashy titles that not enough people are talking about).

And because operating costs are covered by the backlist, publishing houses are free to gamble with the frontlist. To swing for the fence. To go on a quest for the Holy Grail, which is the next bestseller. “Everyone in publishing is always looking for the next bestseller.” [3]

Arthur Levine gave a tongue-in-cheek talk at the national SCBWI conference more than a decade ago entitled something like, “How to Write a Bestseller.” He pointed out (in fact, he even showed a very funny bar graph to illustrate the point) that he currently had a book on his frontlist that had sold fewer than 2,000 copies and one that had sold something like ten million copies.

The point he was making (bar graph and all) is that he had had no way to predict the bestsellerdom of the first Harry Potter book when he acquired those rights at auction for an astonishing $105,000 (which was more than ten times the average amount paid for such rights). He was placing a bet. A big bet. And it paid off. This time. But usually it doesn’t. Usually, publishing houses swing for the fence and miss. Levine might have had hopes and faith and a gambler’s instinct, but he couldn’t know the return on investment he would generate for his publishing house. Because no one knows how to spot the next bestseller. That was the point of his talk.

It’s a gamble.

At the time of the announcement of the mind-boggling advance that Michelle Obama (and her husband, Barack Obama, in a joint deal) would receive from Penguin Random House for the rights to publish her as-yet unwritten book, Publisher’s Weekly wrote confidently, “Michelle Obama’s book is more of a gamble [than Barack Obama’s]. Many insiders said that, despite her popularity as first lady and the notoriety she achieved in the just-closed presidential election, it’s harder to make an educated guess about how well her book could sell, out of the gate or in backlist.” [4]

It was a gamble. Penguin Random House was essentially placing a bet when it offered an advance of $65 million for a (debut!) author’s book. No one knew her book would become the book of the year.

But it isn’t just the big books with mega-advances that are a gamble. The New York Times reports that “…7 out of 10 titles do not earn back their advance…,” [5] which is not the same as saying that publishers don’t earn money on those titles. It’s possible for a house to recoup all of its upfront investment on a book that hasn’t technically “earned out.” In fact, more than one insider has told me that houses almost always earn back their money before any royalty checks flow to the author.

Remember this: it’s the backlist that keeps the publishing houses in business.

It’s the backlist that keeps the lights on. It’s the backlist that pays the rent. It’s the backlist that provides salaries for the staff. It’s the backlist that pays the outsized and unbalanced marketing budgets for the handful of select books that are the “buzz” books of each season. It’s the backlist that covers any loss from the 7 out of 10 books that don’t earn out. And it’s the backlist that generates the $65 million that went to Michelle Obama. Or at least part of it. And now her book will become part of the backlist for Penguin Random House and will keep the lights on in their Midtown offices for years to come. (Like about 52,000 years.)

Do you have a backlist book? Or two? Or three or four? If so, you are crucial to the operation of the publishing industry. It doesn’t matter how small your royalty checks are. In the aggregate, you are essential.

Fact #2: The big publishing houses had a very good 2018. And the first quarter of 2019 is looking strong, too.I don’t know if you noticed back in April and May, but one by one the publishing houses announced their first quarter earnings in the trade publications, and everybody seemed to be doing really well. [6]

HarperCollins led the pack with earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) up 29.3% over the same period a year ago. Revenue increased 5.8% to $421 million. Overall, 63% of revenue in the quarter came from the company’s backlist. And digital sales rose 5% worldwide, pushed higher by a remarkable 32% gain in downloadable audio.

Revenue at Hachette Book Group rose 3.3% in the first quarter, compared to the same period in 2018. Where was the growth? The company said a mix of frontlist and backlist titles resulted in the gain, along with strong sales at Little, Brown Books for Young Readers. And of course, the continued growth in downloadable audio sales played its part in a very strong quarter.

Sales at Simon & Schuster rose 2.5% in the first quarter over the same period in 2018. The sales gains were led by print books (particularly in the children’s publishing group) and digital audio. Also, a number of the company’s best-performing titles in the quarter were backlist from 2018.

Newly renamed Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Books & Media had the biggest revenue gain in the quarter, with sales up over 11%, driven in part by higher licensing income. Also, the company announced the formation of HMH Audio, a new division that is expected to produce about 75 audiobooks each year. [7]

And over at Penguin Random House, revenue rose 1.9% in 2018 over 2017 and earnings increased 1.3%. EBITDA rose to €528 million ($595 million). Remember, PRH is the house that released Obama’s Becoming in November. Clearly, that helped drive growth, but the company also cited digital audio downloads.

In addition, global PRH CEO Markus Dohle wrote a letter stating his ongoing goal: “to grow above the market averages—organically and through acquisitions—particularly in categories that are expanding, such as audio and children’s books—and of course benefit from great frontlist publishing and the growth of our rich backlist—in both fiction and non-fiction.” [8]

Are you noticing the repeated themes in all these earnings announcements? First, they’re all showing an increase in revenue. Second, the growth sectors are children’s publishing and downloadable audio. Third, backlist matters.

Fact #3: Even as the publishing houses post profits, quarter over quarter, midlist writers, once the backbone (and arguably still the backbone) of the publishing industry, are having a really hard time.“There was a time when writers of serious books not destined to become bestsellers could expect to get contracts from publishers that included decent terms and large enough advances to survive until the next book. Today such expectations are rarely met ... While publishers lavish large sums of money and lots of attention on a few high-profile authors, conditions have grown increasingly bad for those writers known as midlist authors.”[9]

That was written in 1998, more than twenty years ago, and things haven’t improved for midlist writers. In fact, as the Author’s Guild survey shows, writing income for American writers (and similar surveys in the UK and Australia show the same decline) has decreased dramatically over this period.

So, connecting the dots: Any publisher’s backlist is made up of a whole lot of titles from midlist authors, along with some backlist bestsellers. (Michelle Obama and Dr. Seuss will always help keep the lights on at PRH.) And it’s the backlist that keeps the publishing houses operating and allows them to gamble on acquiring what they hope will be bestsellers. Sometimes they win, sometimes they lose, because no one knows how to spot the next bestseller. Publishing houses are making a lot of money. Midlist authors are not. In fact, midlist authors have sunk below the poverty line in terms of income from their writing.

That’s all. Just three facts about publishing you might not have been aware of. All thoughts and comments welcome in the Comments section below.

[1] Toby Mundy, former chief executive at UK publisher Atlantic Books, now a literary agent. “Retail: How Bookshops Survived the Amazon Onslaught, Financial Times, June 11, 2019.

[2]“Without Bugs, We Might All be Dead,” Simon Worrall, National Geographic, August 6, 2017.

[3] Jody Archer, former acquiring editor who wrote her PhD at Stanford on bestsellers. TheGuardian, Sept, 23, 2017.

[4]“The Obamas’Book Deals Spark $65 Million Mystery,” Jim Milliot and Rachel Deahl, Publishers Weekly, March 3, 2017.

[5]“About That Book Advance…”,Michael Meyer, New York Times, April 10, 2009.

[6]“Big Trade Houses Start 2019 Strong,” Jim Milliot, Publishers Weekly, May 10, 2019.

[7]“Trade Sales, Earnings Up in Q1 at HMH,” Jim Milliot, Publishers Weekly, May 9, 2019.

[8]“Sales, Earnings Rose at PRH in 2018,” Jim Milliot,Publishers Weekly, March 26, 2019.

[9]"Crisis of the Midlist Author in American Book Publishing," Phil Mattera, vice president, National Writers Union, Revue Française d'Études Américaines, October, 1998.

July 8, 2019

Oh, What a Tangled Web We Weave...

Quick recap: Last week I posted “Power…and Money,” which pointed out four things: (1) American authors’ income has declined 42% in the last decade; (2) the same cannot be said for others who work in the publishing industry; (3) without writers and illustrators, there wouldn’t be an industry at all; and (4) perhaps it is time we, as creators, took back our power.

That’s all the ground I tried to cover in that post. (A blog post—longer than a tweet, but shorter than a book—is a form with limits, which is one of the things I like about it.)

A lot of people responded to the post on social media with their own thoughts, questions, personal experiences, and perspectives, which is great. I’m glad the conversation expanded. (Because I’m no longer on social media, I heard about these responses second hand, which is also fine.)

The more people talked about the topic of power and money in children’s publishing, the more thoughts occurred to me, and I tried to capture some of what people were saying, some of what I was thinking, and some of the thoughts from various books I’ve been reading this summer about the attention economy and the fast-paced rise of surveillance capitalism. (I’ve included below a picture of just some of the titles that I’ve read on this subject in the last few months.)

Out of this nest of ideas, I created a web diagram in my notebook (see header above), and I was struck by both the richness of the topics that bubbled up and the intersectionality of various ideas and experiences that were offered in people’s responses. I did my best to gather all these points of intersection in a visual form and was surprised at what a connected—though disorganized—web they created. There’s chaos in that diagram, but also deep, deep ties.

That’s what I want to explore. The deep ties between the questions people asked following my post.

The most insistent question people seemed to ask was, “But HOW? How do we take back our power?” Lisa Robinson noted in the Comments section, “So what do we do?! Organize a union? Rise up?! Perhaps we need those with ‘more’ power than us to assert their power (ie. bestselling authors with clout (hello J.K. :).”

And looking at responses to the post on Twitter and Facebook, my friend Nancy Werlin pondered in an email: “But everybody is stumbling over the HOW do I reclaim some power and what if the answer is the same one it is throughout publishing careers, which is simply: It’s individual; there is no one way.”