Jacqueline Davies's Blog, page 3

February 17, 2018

Oh, the Things That Kids Can Do

During the Q&A sessions of more than a few school visits, I've been asked if I knew while I was writing my book The Lemonade War that it would become a catalyst for community service projects. (Often schools do an all-school reading event with the book and then host lemonade stands, donating their earnings to charity.) These Q&A kids ask me if I wrote the book with the intention of inspiring others to raise money for good causes. And make the world a better place.

Sigh. Oh, how I wish I could say 'yes.' Wish that I could claim a piece of all this goodness and love and generosity that flows from these school events. But no, that's now how it happened. I had no idea that my book would serve as the launching pad for the charitable efforts of hundreds of thousands of people—students, teachers, librarians, principals, parents—raising millions of dollars over the more than ten years since the book was first published.

The truth is, I don't write stories to try to make people do anything. Except maybe think, and even that's optional. But what a glorious, unintended consequence of The Lemonade War: that so many kids would work so hard to help others. And in so doing, make the world a better place.

Here's how it happened. I had these two characters, a brother and a sister, and they were mad at each other. Nothing out of the ordinary there. What siblings haven't at some point in their lives been angry with each other? And in fact, the idea of siblings fighting over a lemonade stand came from a real-life incident where my two sons argued about a lemonade stand.

In my story, the brother and sister have very clear (and different) ideas about what to do with the money they earn. Evan wants to spend it. Jessie wants to save it. But most importantly, they both want to win the war, and that means ending up with more money than the other. The money itself isn't as important to either one of them as winning the war. Remember, Evan and Jessie were mad at each other from the beginning of the story, and that's what the story is about: conflict and conflict resolution. How do we get into fights in the first place, how do those fights escalate, and how can we end the fighting in a meaningful, honest, and healing way?

No sign of charitable giving so far in this story.

But there's this other character: Megan. She's Jessie's friend and Evan's classmate, and Megan is...nice. She's just a naturally kind and giving person. Some kids are. They have that natural inclination to be generous, to think of others, to try to do the right thing. That's just who Megan is.

So Evan is the kind of character who would spend his money as soon as he has it. And Jessie is the kind of character who would hoard her money away in her lock box, saving it forever. And Megan is the kind of character who would give it all to the local Animal Shelter to help the poor stray dogs and cats who need a home.

And as an author, I'm not passing judgment on any of them. I don't believe that Megan is morally superior to Evan or Jessie. They're just different. And as a writer, I'm interested in exploring those differences and what happens when different kinds of people come together.

But then I needed a plot twist. I needed to raise the stakes in the story. I needed Jessie to suddenly have a windfall and completely obliterate any chance of Evan winning the war. So I had Megan give all her earnings to Jessie, because Megan wants them to donate all their money to the Animal Shelter. Because that's just who Megan is.

At the time, it seemed like a small part of the story. I was so focused on the argument that Evan and Jessie were having that this plot twist added at the end of the story hardly seemed worth noticing.

But my readers noticed it. Caught up in the story as they are, living and breathing with my characters, experiencing the ups and downs of their emotions, how could they not notice this critical moment: that when Megan (who is really, really nice; she's the kind of friend we all wish we had) held a lot of money in her hands, her impulse was to give it away to someone who needed it more than she did. Animals in need of a home.

And that's what started a national movement. Every day, I get letters, emails, news articles, and social media posts about schools that have read the book as an all-school reading event and then raised money (often through selling lemonade, but sometimes in very different ways!) to give to charity. They give to their local library or senior center, to Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation, to hurricane relief, to support services for distressed families, to First Book, to community centers, and yes, to animal shelters. Hundreds of dollars, thousands of dollars, and now, more than a decade in, millions of dollars. Incredible.

As I heard these stories, over and over, across the country, I thought to myself, "It's amazing what kids can do." Every single child can make a difference, the way Alex Scott did in starting Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation. And when kids work together, they can move mountains.

As authors, we write our books—we try to tell a good story, a true story, an important story—and then we send our stories out into the world, and the world makes of them what they will. We have no control over that. But that's really the wonder and miracle of being a writer. I never intended to write a story with the sole purpose of inspiring children to raise money for charity. I wrote the best story I could, and then the children took it and turned it into something entirely remarkable.

I've been so inspired by these stories that I've started to post about them on social media with the hashtag #KidsCan and gather them on my website on a page called #KidsCan. (If you ever find yourself having a low day and could use some inspiration, go to this page!)

Do you know of any efforts by families, schools, or community organizations to raise money after reading The Lemonade War? If so, please send them to me. A newspaper clipping, a school Facebook post, or just an email telling me about the amazing things that your kids are doing, matching literacy with charitable giving. I'll post your story on my Facebook page, send it out on Twitter, Instagram it, and include it on my website. And during the year I'll give prizes and personal thank you's to entries chosen at random.

Because I think the more we talk about all the incredible things that kids are doing, the more this movement will spread. More kids will realize that they're not powerless. They're not insignificant. And they're not alone. Kids Can make a difference. Kids Can lead the way. Kids Can make the world a better place.

September 21, 2017

I'm a what...?

Every morning, I roll out of bed and go for a walk. Early. Sometimes it’s 5 am. Sometimes a little later.

I walk for 2.6 miles (yes, I Google Mapped it), and I always take the same route. It includes one killer hill, a gentle downslope past the high school, and then flat terrain through the “downtown” of my small town. I pass historical houses (this is New England, after all), my grocery store, the town library, and my children’s elementary school.

My kids no longer attend Hillside Elementary; my youngest is off to college this year. But I still think of Hillside as my kids’ school. They went to that school (and so did I, as a parent) for a total of twelve consecutive years, so, yes, it is ours.

I notice something new as I take my morning walk, now that the school year has begun. Lawn signs have sprouted up throughout the neighborhood, signs announcing that Hillside has a mascot—the Hornet. The signs cheerfully proclaim: “Welcome to Hillside!!! You’re a hornet now!”

Yikes! Am I the only one who’s really scared of hornets? Am I the only one who avoids hornets whenever possible? Am I the only one who runs screaming if I see a hornet coming at me?

In fact, I’m not sure I can think of one positive association I have with a hornet. Now, I’m sure hornets do a lot of good in the world. (Full disclosure: I’m not a huge insect lover, but my guess is if I asked my smart, scientist/writer friends Loree Griffin Burns and Sarah Albee about the kinder, gentler side of hornets, they would probably have a lot to tell me.)

Still, school mascots are more of a gut reaction thing. A first impression thing. And my gut reaction to hornets is: OUCH. PAIN. RUN AWAY!

This got me thinking about the naming of mascots at other elementary schools, and so I did a quick survey. I visited 52 elementary schools last year. This morning, I surfed through the websites of all 52 to find their school mascots. Some had them prominently displayed; others didn’t seem to have any at all. Here’s the list I came up with:

The Vikings (2 schools)The PhoenixThe CougarsThe Owls (2 schools)The Eagles (3 schools)The Tigers (2 schools)The Mustangs (2 schools)The PatriotsThe WolvesThe PoniesThe Bears (2 schools)The PackersThe BruinsThe BuffalosThe BulldogsThe PanthersThe LionsSo clearly, the Eagle wins (!) in my totally unscientific survey, with the Vikings (who would have thought?), the Owls, the Tigers, the Mustangs, and the Bears tying for second place.

But, wait—this isn’t a competition!

Or is it?

As I look at the list, the word “ferocious” springs to mind. “Fierce.” “Attack.” I see bared teeth and sharp claws. The Cougar is shown hissing. The Bulldog is growling. The Wolf is howling at the moon. And the Hillside Hornet is wearing boxing gloves and clearly spoiling for a fight!

There are a few kinder and gentler animals mixed in with the predators. I don’t think the Phoenix does anyone any harm, although it’s got a rather gruesome tale of its own to tell. The Mustangs and the Ponies would certainly get invited to my birthday party, but I have mixed feelings about the Buffalo. I want it to thrive somewhere, but not necessarily too close to me. Those animals are huge. And shaggy. (Hey, I’m scared of elk.)

Even the Owl is potentially dangerous. At one school, the image is of a wide-eyed fluff-ball hopping on one foot and flapping its wings, but at the other school, the Owl mascot looks like it would rip my head off in a nanosecond.

(“Hold on,” you’re saying, “what about the Packers?” To which I respond: you don’t find the idea of canned meat SCARY?)

What are we saying to our kids? Be tough. Fight hard. Prepare to attack. Show your teeth. Extend your claws. Make sure your beak is sharp.

In a time when we work so hard in the classroom to foster community and teamwork, it’s hard not to notice that many of these mascots are lone hunters. One gets more a sense of “eat or be eaten” from looking at this list than one does of “everyone is welcome and safe here.” I wonder what the kids think. I wonder what the grownups who chose the mascot think. I wonder if we implant in our children, too early, the idea that life is a question of survival of the fittest. That if someone else wins, that means you lose.

And so we choose to honor the strong, ferocious meat eater over the gentler, less toothy herbivore. (As an aside: I stumbled across the Kinkeade Early Childhood School in Irving, Texas, that has a really cute kangaroo named Joey as its mascot. Wouldn’t you rather eat lunch with Joey than with a hornet?)

Another school year begins. We send our children off to be educated, to be social, to be challenged, to be out in the real world—but hopefully not to be stung. Be careful where you sit, Hornets!

August 24, 2017

Namely

For the past week, I’ve had the great good fortune to be on a solo writing retreat in the seaside village of Onset, which is a small peninsula (just 1.3 square miles) that extends into Buzzards Bay near Cape Cod. It’s a lovely, eclectic, peculiar community of tiny cottages inhabited by close-knit neighbors whose families have been connected to the village for generations. And when I say “connected,” I mean connected: The village was originally built in the 1880s as a summer camp meeting for Spiritualists. The cottages were used as second homes for people from Boston and other northeastern towns who would come to Onset for gatherings in which mediums would speak to the dead. What better place for a writer in search of a whispering muse?

One of the many joys of being here has been biking and walking nearly every street in the compact village. The cottages sit cheek by jowl, so in a short walk there are plenty of homes to gaze upon. And dream about. And wonder how much square footage and is there a downstairs bathroom and how old is the septic system…? (If you haven’t yet read my August 7 blog post “There’s a Reason They Call It an Obsession,” now might be a good time to do so, just so you’re up to speed on my relentless desire to own property that I really, really don’t want to own.

Many of the cottages here in Onset have names. Weather-beaten signs attached to the front door or the chimney or the widow’s walk announce the house’s appellation. Some of these designations seem to be mostly about the house itself: Eastlook or The Red Cloud Cottage or Shellpoint House or Gull's Nest. Some seem to reference the spirit of the community itself: Happy Ours or Seas the Day. But others seem to point directly into the soul of the resident.

For example, when I see the house named Happily Ever After, a neat little cottage facing the ocean, I picture a retired couple. They worked for years to raise their family, launch their children into the world as adults, keep up the family summer cottage—probably renting it to out-of-towners for most summers to help pay the double mortgage, doing the weekly housecleaning and yard work themselves to make the income go a bit farther. They did without when they had to, but always kept their eyes on the horizon. And finally, they were able to sell the triple-decker in Boston and retire to the village to become “year-rounders.” At least that’s my version.

Or the house on West Boulevard named, Night Rule, which brings to mind wild nights of sweaty poker playing in one’s underwear; the thick, blue smoke of cigars; and the occasional but always ill-conceived skinny dip in Shell Point Bay. I wonder if the residents of Night Rule know that “night-rule” is a “nonce-word,” that is a word created for one single occasion only. In this case, “night-rule” was coined, used, and discarded after one use by none other than William Shakespeare. It’s spoken by Oberon, the King of the Fairies in A Midsummer’s Night Dream, and its very definition is in dispute. According to some scholars, it means “revelry” or “frolic” (that is, something lighthearted, fun, and of no lasting consequence). But other Shakespearean scholars insist it means “havoc” or “mayhem,” which connotes something a little darker and more menacing.

Now that I think of it, I’m certain the owner of the lovely seaside cottage is well aware of the meaning and origin of the house’s name: Night Rule. I’m revising my original picture of the bacchanal. (Writers are allowed to do that. Change their minds completely and rewrite a scene. Isn’t that awesome?) Now my revised picture is of wild nights in the seaside cottage spent reading The Riverside Shakespeare, which contains the complete works of the bard and which was one of the best Christmas gifts I ever received as a teenager. (While Oberon was King of the Fairies, I was Queen of the Nerds.)

All of this makes me think about what I would name my own summer cottage. (Not that I’m going to buy one because I really, really don’t want to own one. (See Obsessions.)) I can picture it: gray-shingled and weathered, facing the sea without fear, a place where writing has a chance to happen. I think about the rhythm of my writing days this past week and the work I’ve accomplished on not one, but two books.

In the morning, I wake up, knowing that the entire day lies before me, uninterrupted, unfractured, full of possibilities and free of all responsibilities. At that moment, I would name my seaside cottage Great Expectations.

The work begins. There are many false starts. I stumble. The pathway is unclear, unmarked. But slowly, the story begins to take shape and there is the beginning of something. It isn’t much, but it’s unmistakable: something is on the page that wasn’t there before. That’s when I would name my cottage Birth of a Notion.

The hours pass. I’ve been unusually productive in this retreat house. I’m so grateful for the time, the silence, the emptiness that allows the ineffable process of writing to take place. And then, something unexpected happens. A character says something I hadn’t seen coming. Or an idea pops into my head as I sit on the beach, burying my toes in the hot sand. Or it suddenly occurs to me that the plot needs to move in a wholly different direction. Ask me the name of my cottage then, and I would say Unexpected Revelation.

Now I’m in the zone. The new idea has re-energized me, and all kinds of “stuff” is spilling out. It might be god-awful crap, and thankfully I won’t know that until tomorrow when the whole process begins again, but for now, the pages pile up and it is all glittering brilliance. My cottage is named Spun Gold. Or perhaps simply Bliss.

Alas, nothing lasts forever. After many productive hours, the gears start to grind a little more slowly. The ideas don’t seem quite so shiny. My brain is tired and my body wants chocolate and my spirit begins to sag. The sign banging against the outside of my cottage has changed. It now reads Diminishing Returns.

At day’s end, I assess: did I accomplish as much as I had hoped? If not that, did I at least get enough done? Or, on the darkest days, I ask myself did I get anything of value done? These questions are pointless. When I’m on retreat, the best I can do is the best I can do.

I’ve recently taken up bicycling again. Just as a means of transport. A way to get to the grocery store, the library, and the bank without taking my car out of the garage. I’m hopelessly out of shape. I plod up hills. Packs of ten-year-old boys zigzag past me, sometimes looping and circling me, just because they can. Occasionally, I have to get off the bike and walk—head hung low and filled with shame. But I’ve developed a new mantra as I struggle to keep pedaling when the bike seems to be traveling negative miles per hour: “Go as far as you can, and then stop.” It’s also my new mantra for writing retreats. Great expectations are wonderful at the beginning of the day, and I’m always astonished by and filled with gratitude for those unexpected revelations, but in the end, you go as far as you can and then you stop. And it’s good. So when all is said and done, I think my cottage would be named: A Good Place to Stop.

And here it is.

August 17, 2017

Nine Dinners

My friend Melissa was the one who said it. “Nine dinners.”

There were fourteen of us at the table, all speakers, volunteers, or organizers at a week-long literacy conference in Virginia. Our host had graciously invited us to dinner: to enjoy each other’s company, to relax after a day of presenting, to eat good food and drink wine at someone else’s expense (thank you!)—to laugh, to reflect, to enjoy some spirited differences of opinion. Some of us were writers; some of us were illustrators; some of us were literacy experts; some of us were smart, opinionated librarians. (Ooh, I love smart, opinionated librarians).

The question was, “What would you do if you knew you had only nine dinners left with someone you cared about but didn’t see all that often?" I thought immediately of my brother who lives on the West Coast. And Melissa, whom I’ve known for thirteen years and who lives just a couple of states away in tiny New England, and yet it took a conference in Virginia of all places (!) to get us to the same dinner table.

What would you do to get yourself to one of those last nine dinners? And what would you talk about? Would you be sure to tell that person how much they meant to you? Or would you talk about the Red Sox? (Or how much the Red Sox meant to you?)

The conference director at the far end of the table called out, “I didn’t hear. What are y’all talking about?”

“Death!” I shouted back gleefully. “Melissa is reminding us that we’re all going to die, and it’s going to be very, very soon!”

“Oh, that!” said the conference director. She waved her hand. She had had a long day making sure each conference event went off flawlessly, making sure the needs of others were taken care of before her own. And doing it all in stunningly high heels and a gorgeous suit. That woman dressed to kill!

(As I think back on it now, she must have already received the news that a dear, elderly member of her family had just passed away. She missed part of the conference on Friday to attend the funeral. I know that that evening she smiled at us, a genuine smile, a warm smile. She liked seeing all of us enjoying ourselves around her table.)

Nine dinners.

What I thought about was this: If you knew there were just nine dinners left with a loved one—a faraway cousin, an old college friend—what would possibly keep you from one of those dinners? A broken leg, a bad case of the stomach flu, a terrible headache, that first tickling of a sore throat that means a cold is on its way, a forecast of heavy rain, an incredibly frustrating day at work, just that feeling of I don’t want to go out tonight. We’ve all done it. Made the last-minute excuse that was real or felt real or contained the possibility of reality. Because, of course, you could always reschedule.

Nine dinners.

Tomorrow, I’m driving two hours north to spend the day with Melissa. We haven’t done that in years. She has a new house to show me! Yay! We might go on a schooner ride. Fun! We might take a yoga class.(Hmm....) I’m throwing my bike in the back of my car, in case we're in the mood for riding around the peninsula. I’m sure there will be at least one walking of dogs, as there always was when we summered nearby, years ago.

She thinks she has to entice me with 21-foot schooners and spectacular ocean views. But she doesn’t. I would drive up there just to sit around her kitchen table and yak about books and dreams and how to craft a story and why some shoes make so much noise when you walk while others are nearly silent. We have had these exact conversations and more.

Because the truth is—and we all know it, you do, too—that there really are just nine dinners with each of the people we love. Oh, the number might be slightly off. Maybe it’s twelve or maybe it’s two or maybe it’s forty-seven, but does that really make that much of a difference? Whatever the number, it is finite and it is not enough. That, I can guarantee.

So, now that I’ve told you, as Melissa told us, that there are only nine dinners, what will your response be?

Here’s one of mine: I’m booking tickets to see my brother in LA in October. You see, since the time when we were children and played the Milton Bradley game of Life (in which you had to bet your entire fortune on a single number and the spin of the wheel—ending up at the Poor Farm or Millionaire Acres), my lucky number was always nine. I bet it every single time. Why would I change it now? That would just be crazy.

August 7, 2017

There's a Reason They Call It an Obsession

E.B. White’s house and farm in Brooklin, Maine, are currently for sale, and I keep trying to work the numbers. The way I see it, if 370 like-minded people all agree to chip in $10,000 a piece, we can swing it, which sounds completely doable to me. Of course, the tricky part is that the 370 people need to be the right 370 people. Ideally, they would all have some connection to children’s literature, either as creators or editors or readers or sellers or reviewers or simply lovers of the stories that have marked our childhoods. They have to be not crazy. That would be really important in a venture like this. It would be nice if they were all fairly easy going and had a good sense of humor. And, most important of all, they all have to have no interest in living on the farm themselves since I want it all to myself.

My list of potential takers is short but growing.

I sent an email to a well-to-do friend of mine, who actually could make the purchase outright if she so chose, and asked if she would please buy the farm and install me as its permanent, on-site caretaker. Oddly, she has not responded. I can only guess she’s a little busy at the moment. August. People are often on vacation.

This is all a symptom of a much bigger problem, one I’m trying to figure out. I have lately and violently become obsessed with the idea of owning a few acres of land in Maine that overlook a pond. (Important to note: This obsession began before I knew that E.B.'s farm was for sale, and really that’s a separate obsession. I’m proud to claim that I’m complex enough to entertain more than one obsession at a time.)

Anyway, this other obsession: two to five acres of wooded land on the edge of a pond. What’s that about?

Here’s what I envision: a one-room cabin with a wood stove, running water, and solar panels with battery storage. A place to write. A place to think. A place of great solitude and natural beauty.

Why am I so taken with this fantasy? How often would I actually drive five hours north into the woods of Maine to take advantage of all that beautiful solitude? Why not just rent a cabin once a summer and call it a day? Why am I haunted by this image of a small cabin in a vast wilderness?

A friend of mine suggested it’s because I want two things simultaneously: a change of scenery and the familiar sense of home.

She’s probably right. My writing (and my sense of well being) improve when I can kick myself out of the wagon-wheel rut of my day-to-day existence, but land in a place that feels welcoming and attuned. A place that’s strange, but not too unpredictable. A place that is vast, but contained. Which is why the fantasy is so dependent on five or so acres of untouched land enclosing a single-room cabin no larger than my bedroom at home.

And you know what? I found it. I actually found the absolutely perfect place with 5.8 acres of wooded land that sloped gently down to the edge of a pristine pond. And because it was east of Bangor and more than an hour from the coast, it was actually affordable. It was one of those rare fantasies that held the possibility of slipping into reality.

But two things: First, I hesitated and the property is now under contract to someone else. (Who? Who are you? Please make yourself known. We must be kindred spirits of a sort.) Whoever it is, the little red flag on the internet site announces: Pending Sale.

And second: even I know that I don’t really want to own a cabin in the woods. I can barely manage the house I live in: mowing the lawn, wiping down the kitchen counters, and getting to the dump on a semi-regular bsis. I know, I really do know, that owning a piece of property is a burden, a headache, a constant worry, a financial drain. And the very last thing I need right now is an extra burden in my life, financial or otherwise. I’ve spent the last eight years shedding burdens and I’m nearly down to the bone.

Which makes it all the more interesting to ponder why the fantasy persists. Because it does. At least twice a day, I check that real estate listing to see if the Pending Sale flag has disappeared—if the sale has fallen through and the property is back on the market.

And what will I do if it is?

March 26, 2017

Saddle Up: Why I Keep Going Back to School

While reading a recent article by Bill McKibben, I had an epiphany. (If you’ve read any of McKibben’s thought-provoking books, you know that this is not an unusual reaction to his work. Henceforth, I am calling all such revelations McKibbeniphanies.)

In any case, this particular piece, entitled “Pause! We Can Go Back!,” was a review of a book by David Sax called The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter, a book I’m looking forward to reading. There are many insights throughout the brief review, and I have a feeling I’m going to be writing several blog posts in response to Sax’s and McKibben’s thoughts about life in the digital age, but for now I want to focus on just one—the one that felt the most personal to me.

Sax’s book, and hence McKibben’s review, explores the state we find ourselves in circa 2017: McKibben writes, “Our accelerating disappearance into the digital ether now defines us—we are the mediated people, whose contact with one another and the world around us is now mostly veiled by a screen.”

Like Sax and McKibben, I protest (too loudly) that I am no Luddite. I spend much of my day in front of a computer screen, either creating content or ingesting it. I have a Smartphone; I do my banking online; I text…when necessary. I’m keenly aware of the benefits the digital world has brought to my professional life. In fact, it’s hard to imagine being a writer without the breathtaking convenience of the Internet.

But I also mourn the loss of…oh, so many things. True solitude. The ability to go some place and actually be there. Certain mysteries that should remain mysteries but never do—at least not for more than the twenty seconds it takes to whip out a Smartphone and query Google.

Sax, by way of McKibben, lists these analog-to-digital losses. We have lost “places where we can touch actual physical objects….” We have lost “finishability”—a concept I adore—which Sax explains as “a defined beginning, middle, and end” and which McKibben contrasts thus: “It doesn’t spool on forever in the manner of the Web.”

And then there’s loneliness. “This was supposed to be digital’s real selling point—the ability to reach out and touch any other human being, to never be alone,” writes McKibben. But as we all know, we rarely find a feeling of true intimacy through digital devices. Instead, as Sax writes: Even if you’re playing games “with the same group of friends around the world each day, talking smack over your headsets, and typing in snippets of conversations, you were ultimately alone in a room with a screen, and the loneliness washed over you like a wave when the game ended.”

Through much of the article, I nodded my head, ruefully acknowledging all that we’ve lost without even realizing our losses. But it was near the end of the article, when McKibben brought up the issue of education, that I had my “aha” moment.

A bit of background first.

It is school-visit season as I write this post. As predictable as the phases of the moon, as faithful as the cliff swallows of San Juan Capistrano, as regular as sea turtles climbing ashore to lay their eggs, the spring school-visit season is upon us, that time when schools across the country invite authors to meet their students and talk about reading, writing, and what it’s like to be an author.

I visit approximately fifty schools each year. Just last week, I was in New York and Pennsylvania, visiting nine schools over five days and meeting 4,169 (give or take a few) students. I’ve traveled as far as Hawaii (from Massachusetts) to do school visits, and I’ve visited schools in more than half the states in the country. Over the years, I estimate that I’ve visited more than two hundred thousand students.

But I don’t do Skype visits. I don’t like them. In the past, I did them, because I wanted to be accommodating to schools that couldn’t host an in-person visit, but I always felt miserable—before, during, and after—exactly the opposite of how I feel when I do an in-person visit. When I visit a school, I feel engaged, vital, connected. The kids make me laugh. They make me think. They challenge me. There’s a lot of back-and-forth in my presentations. Teachers often remark how interactive my visits are. And I always leave the school feeling deeply satisfied.

But visiting through “the veil of the computer,” via Skype or some other technology, leaves me grumpy. Unsatisfied. Hungry. At the end of the session, I press the little icon that signifies “hang up,” and I invariably think, What was the point of that?

I’ve always blamed this feeling on the technology and myself. I say the technology’s “glitchy,” which it is. I say it’s hard to keep the kids’ attention, which it is. I say I can’t get a sense of the kids, I can’t get to know them, I can’t get them to know me—all of which is true.

I told myself there must be something wrong with my setup (laptop, internet connection, microphone). There must be something wrong with me. Why couldn’t I get that same wonderful feeling of connection with the kids that always happens when I visit a school in person? And did it matter? Was it selfish of me to want that deeply satisfying feeling of having reached out and made a difference in a child’s life? After all, the teachers always say, “The kids love visiting authors via Skype!” But from where I sit, they don't look like they love it. They don't even look like they're paying attention. They fidget. Their eyes wander. They engage in side conversations. None of this happens when I meet with kids in person. I’m accustomed to holding an auditorium of five hundred students in rapt silence. Or eliciting an explosion of laughter. Or having hands wave wildly in the air, each student eager to answer the question I’ve posed. Was it just me who was failing to connect in our digital age?

When I finally confessed all of this to Rachel Vail, she told me I didn't have to do them. She officially gave me permission to say no. And so I stopped.

But I felt inadequate. Selfish. Guilty.

So there I am, reading Bill McKibben’s review of David Sax’s book. And I read this: “The notion of imagination and human connection as analog virtues comes across most powerfully in Sax’s discussion of education.” I sit up in my chair. Ah, this pertains. “Nothing has appealed to digital zealots as much as the idea of ‘transforming’ our education systems with all manners of gadgetry.” Yes, yes! I think. That’s what I keep hearing. Is it just me who’s not keeping up?

McKibben goes on to describe the excitement around MOOCs (massive open online courses), but also the truth that “many of these classes have failed to engage the students who sign up, most of whom drop out.” I think to myself, that’s just what I see through the computer screen when I Skype with elementary school students. They’re there, but they’re not there.

And then McKibben gets to the crux of the matter: “Even those who stay the course ‘perform worse, and learn less, than [their] peers who are sitting in a school listening to a teacher talking in front of a blackboard.’ Why this is so is relatively easy to figure out: technologists think of teaching as a delivery system for information, one that can and should be profitably streamlined. But actual teaching isn’t about information delivery—it’s a relationship. As one Stanford professor who watched the MOOCs expensively tank puts it, ‘A teacher has a relationship with a group of students. It is those independent relationships that is the basis of learning. Period.” [emphasis mine]

Technologists think of teaching as a delivery system for information…but actual teaching isn’t about information delivery—it’s a relationship.

And there was my McKibbeniphany.

When I finish a presentation at an elementary school, it’s a pretty common experience that I’m “rushed.” That is, a swarm of students descends and encircles me, each student vying for my attention. They want to tell me things about their lives: that they have a bossy older sister, that they have a dog like mine, that they once lived in Cleveland or that their family is Greek. If one of them is brave enough to reach out and hug me, a dam breaks, and suddenly kids—girls and boys, kindergarteners through fifth-graders—are hugging me, high-fiving me, fist-bumping me, touching my hair, reaching out to play with my bracelets. Connecting in the most basic way. It goes right back to the beginning of McKibben’s article and the discussion of the things we’ve lost: “Places where we can touch actual physical objects.”

I have long known that for some students the single most important part of my visit to their school is the chance to come up to me after my talk and touch a real, live author. And to feel the gentle squeeze of my hand on a shoulder, to see my eyes staring directly into theirs, and to know in the most physical and elemental way: The author was here. And she looked right at me. And we shared a moment together. Whatever I might say in my presentation about ‘character development’ and ‘story arc’ and ‘the essentials of revision’ is secondary to that experience.

And you can’t get that over the Internet. McKibbeniphany!

January 20, 2017

March, in January

I’ve been thinking a lot about women who march, as I ready my own pack of carry-along essentials for tomorrow’s Women’s Boston March for America: water, granola bars, ID, MBTA pass, cell phone, hand warmers. (My eighteen-year-old daughter has planned for the march so well as to be able to carry all her essentials in her sports bra. But then, she’s always been a more efficient packer than me.)

And as I study the route of the march and figure out the logistics, my mind travels back to the Uprising of the 20,000, when so many women—young, poor, immigrant garment workers in New York City—took to the streets to march in protest of unsafe working conditions in their factories. The Uprising began on November 23, 1909, and the strike led by the women lasted for eleven weeks.

It’s not that these women were the first to march. Or the first to strike. But they turned out in greater numbers than had ever been seen, and they hung in there. For eleven weeks.

Strikes in those days were ugly affairs. “From the outset, the young strikers faced three-way opposition from the manufacturers, the police, and the courts. [Manufacturers] hired thugs and prostitutes to abuse strikers, often with aid from policemen who then arrested strikers on trumped-up charges of assault. In court, strikers faced hostile magistrates who upbraided the young women (“You are striking against God and nature,” scolded one enraged judge), fined them, and, in some cases, sentenced them to the workhouse.”1

But they continued to march.

In addition, lost wages were an incredible hardship for young women who helped support their families with their meager earnings. Missing even one week’s wages for these workers often meant the difference between eating and starving. Eleven weeks? That’s a long time to go without a meal.

But they continued to march.

And it was winter. November to February in New York City. When you look at photographs of the marchers, you can spot the well-heeled “reform ladies” who lent a vital hand to their poor working sisters. The wealthy reformers have warm winter coats. The rank-and-file factory women are often without coats. They didn’t own them.

But they continued to march.

Eleven weeks. Their endurance stunned and shamed the nation. These young women, many of them the age of my daughter, maintained the strike longer than their male counterparts who had led strikes in industries with predominantly male workforces. In fact, it had been a young woman who had defied the timid male leaders of the various garment workers’ unions to launch the Uprising. “In November, there was a mass meeting of workers from many different companies. Male union leaders dithered on the stage, debating what to do. Like many men in their position, they did not believe that women could be trusted with a strike. From the audience, a 23-year-old Ukraine-born Jewish woman stood up and demanded, in Yiddish, that workers take control and go on a general strike. Leading the gathered workers in a traditional Jewish oath of solidarity, Clara Lemlich started what became the Uprising of the 20,000.”2

Women, in my experience, excel at endurance. And walking. A child on our hip. A bucket of water on our heads. Bringing in the harvest. Rocking the cradle through the night. Slow and steady. We are the tortoise. We are the endless drip of water that carves out canyons. We are the tectonic shift that cannot be stopped.

And so we continue to march.

January 16, 2017

Tell Me a Story

First, go read “The Stories We Tell Ourselves,” an essay published today in The New York Times. (You have my permission to skim.)

Done? Good.

Now, I could talk about what I consider to be some missing connections in this piece (the loose definition of the word "value" and an odd unwillingness to specify values ascribed to certain scenarios), but truthfully, what I want to talk about is something at the very beginning of the essay, because that's where my attention got snagged. Right at the start, the author tells a (presumably true) story of himself: “I was driving home from work and a car cut me off. The guy was driving really slowly, and I wound up following him for half a mile…So I laid on my horn the whole time.”

He says that this story expresses this value: “I am not a person to be messed with.”

At this point, my mind wanders and I have trouble focusing on the rest of the essay. I try to imagine the road, the car, the other driver. My mind creeps to math problems from my youth: If both cars were traveling on a highway at 50 mph after the driver cut off the author, then the author was inconvenienced by this person for a total of 36 seconds as they traveled half a mile in tandem. If, on the other hand, they were traveling on a residential side street and the really slow driver was going 20 miles per hour, then the author leaned on his horn for a full 90 seconds.

In the first scenario, the author was slowed down for half a minute. For half a minute, he couldn’t go quite as fast as he wanted.

In the second scenario, the author audibly assaulted the other driver (and every human and animal within a hundred yards) for a really long time. Have you ever leaned on a car horn for a full 90 seconds? Go do it now. Go to your car (if you have one) and sound the horn for 90 seconds. Time it. I bet you can’t stand to do it. The noise is so obnoxious, so unnecessary, so completely out of proportion with anything that might have caused it in the first place that I bet you will stop well short of 90 seconds.

—

The essay is called “The Stories We Tell Ourselves,” and so it's about how “reflecting on the stories we tell about ourselves might reveal to us other aspects of who we are and what we value,” and that this might help us break out of the limiting echo chamber many of us inhabit. The author further encourages us to listen more carefully to the stories others tell about themselves.

Hey! I can get behind that!

But I can’t help but think the author missed another really important intersection, which is The Stories We Tell Ourselves About Other People.

Here’s a story, and I promise that it’s true, to the best of my recollection.

I was twenty-seven, and I was driving in the congested center of a completely unfamiliar town on Long Island where my parents had moved recently. I was trying to get a prescription filled for my father who was newly diagnosed with lung cancer. We had just, within the hour, received test results that proved the cancer was inoperable. There were no more options. My father was going to die. He was 56 at the time.

I was stopped at an intersection, having just pulled out of the incredibly jam-packed parking lot of the strip mall where the pharmacy was. I didn’t know my way. I wasn’t familiar with the traffic pattern. I was driving a strange car. The sun was in my eyes. I was trying to make a left turn onto the main road that ran through town, but the traffic was bumper to bumper and no one was yielding the right of way. I was distracted. I was grief stricken. My father was dying.

I guess I missed my chance. There must have been an opening in the traffic, but I didn’t see it. The driver behind me (a middle-aged man about my father’s age) leaned on his horn and then, in a fit of rage, swerved around me, creating a lane that didn’t exist. He stopped, rolled down his window, and proceeded to pour forth a torrent of expletives the likes of which I’d never heard before—or have ever heard since, for that matter. He finished by shouting “You stupid ___!” (an insult I’m unwilling to print, but one that’s reserved for women), jerked his car in front of mine, and then shoved his way into the flow of traffic and took off.

Hmm. I guess he was not a person to be messed with.

And I don’t know the story he told about himself on that day. But I know for sure he wasn’t sitting in his car telling himself a story about me. He wasn’t asking himself what might be up with the young woman in a ponytail who seemed really hesitant about moving forward.

It’s been almost thirty years since my dad died. I miss him. We still tell stories about him, and not just the same old ones. New ones crop up. (I found out two days ago that he voted for Nixon in 1972! Seriously? I never in a million years would have guessed.)

So there are memories and new stories, and my father lives on and continues to inform and affect the person I am. For example, here’s one thing that is now woven into the fabric of my life. Whenever I’m on the road, whether it’s a highway or a residential side street, and someone cuts me off—as people do, especially in Boston—I find myself thinking, I wonder if that person just found out that his dad is dying. And then, to pass the time, I often begin to tell myself a story about the reckless driver and what he might be moving toward or racing away from.

January 8, 2017

Patronage

In its end-of-the-year roundup of “11 Ways to Be a Better Person in 2017,” the New York Times offered this top tip: “Live Like Bill.” The article elaborated:

No one treasured his independence more than the late, great photographer Bill Cunningham. Live by his immortal words. “Once people own you,” he said, “they can tell you what to do. So don’t let ’em.”1

Once people own you…

I’ve been thinking about this concept a lot lately. As an artist, who owns me? How does one become owned? Is there an upside to being owned artistically, and am I aware (enough) of the downside?

Of course, there’s been patronage in the arts for centuries. Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Renoir, John Singer Sargent, Botticelli, Rafael (to name just the most obvious): all relied on patrons. In most cases, it was an entirely formal affair:

Whatever way a patron was commissioning an artist, there was always a formal contract written and signed, concerning the money and job for the artist. Artists of a lower status usually held this contract without breaking it, knowing that this was probably the only way to make a name for themselves. However, as an artist rose in respect and reputation, they would be more likely to break a contract for more money, a better opportunity, or more acceptable terms. This power struggle led to conflict between artists and their patrons. As Michelangelo wrote, “One cannot live under pressure from patrons, let alone paint.”2

Sigh. And there it is. One cannot live under pressure from patrons, let alone paint.

But wait! They did paint. And it was pretty good, their work, although there are countless stories of dissatisfied patrons. (Apparently Gilbert Stuart, famous portraitist of George Washington, once replied to a client’s complaint regarding his wife’s portrait: “You brought me a potato, and you expect a peach!” Again, sigh. We’ll try to get past the readiness of men to compare women to tubers and fruit.)

I suppose we could spend some time on a lazy Sunday wondering what Michelangelo might have painted if he hadn’t been born the son of a failed banker and thus forced to rely on the florens of the Medicis.

But instead my mind jumps to Virginia Woolf stating, baldly, that “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction…” In fact, Woolf goes so far as to say that a woman must have five hundred pounds per annum of secured income of her own in order to create art. The money must be unencumbered. She must owe nothing to anyone. Hmmm. She wrote this in 1929. Is it true today?

I am a woman. I write fiction. I do not have any unearned income. I support myself and my family. So…

Who owns me?

There’s a song in the musical Hamilton in which Jefferson, Burr and Madison plot to ferret out Hamilton’s supposed misconduct:

Look in his eyes!

See how he lies.

Follow the scent of his enterprise.

…

Let’s follow the money and see where it goes,

Because every second the Treasury grows.

If we follow the money and see where it leads,

Get in the weeds, look for the seeds of

Hamilton’s misdeeds.

In the end, I wonder if it’s as simple as following the scent of one’s enterprise. The person who owns is the one who has the money. The person who is owned is the one who conforms, who responds to the demands of others, who acquiesces—to keep the money flowing.

Artists? Who owns you?

And can we all live like Bill, and not let ’em?

December 30, 2016

Intersections

I've been thinking lately about freedom and power and the ways in which the two intersect, confront, and challenge each other, particularly as an artist and more particularly as a woman. I've been thinking about how these two related (but sometimes frighteningly divorced) spaces interact in ways both expected and surprising.

Freedom. It's a glorious word and an even more sublime concept. To do what one wishes to do. To do it without apology. Without explanation or justification. To live without the need to ask permission. Freedom.

Power. For women, this one is more fraught. Power carries so many heavy things: responsibility, the way it feels on our shoulders, the way others see us when we wear it. Men seem to wear power with greater ease. But women (and artists) are still not taught how to carry power. We look to men as our models: and that doesn't work. We have so few women as models: which seems only to reinforce the idea that somehow this is not our clothing. It is borrowed. And we don't look particularly good in it.

On Wednesday, I was in New York on business. Business, business, business. Artists out there, do you hear me? You know what I'm talking about. The things that need to get done (contracts, negotiations, marketing, networking) so that we can do the things we want to do (writing, painting, singing, dancing). Wednesday. A day of business in New York (which is a city that pulses and irradiates as the freedom and power capital of the world).

I was both unusually free (no children, no husband, no companion—with his or her own needs) and also focused on the idea of power, as one always is when negotiating. When creating a strategy. When testing new boundaries of what can be achieved. Freedom and power.

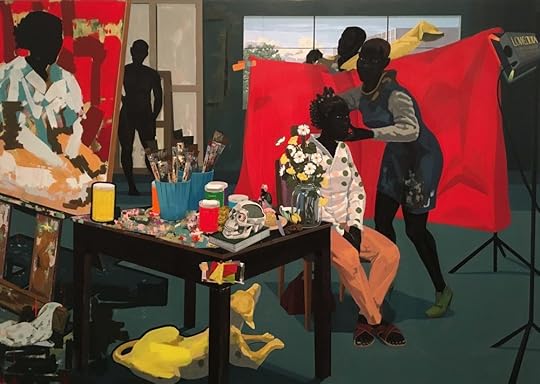

But after my midday meeting was done, I revisited the Kerry James Marshall exhibition at the Met Breuer museum, entitled "Mastry." (I'd seen it several weeks ago, in a rush, but this time I could take my time. My train didn't leave Penn Station until 5:00 PM. And I was unusually free.)

I'm including here one of Marshall's monumental pieces (Untitled (Studio) 2014, Acrylic on PVC panels) and his words from a short video produced by the museum. The painting is a favorite of mine, in part because of the subject matter: it shows the studio Marshall visited in the seventh grade, which was the first time (by his own accounts) that he realized that he could be an artist. The museum commentary describes the scene of the painting as "a place of labor where an allegorical catalogue of all modes of art making is on display." To my eye, the brushes could be pens; the canvases could be blank paper; the art students could be young writers. Or singers. Or dancers. Or sculptors. Here are the things we use to create our particular art. But the creation is all one.

The dog, of course, could only be a dog.

Here, then, are Marshall's own words:

"What you hope a retrospective shows, in a way, is that your career was a thoughtful one. Embedded in the imagery is a narrative of change and transformation and growth. Mastery is an important concept. It implies having achieved a certain level of proficiency that gives you the freedom to do what you want without fear of the consequences. In the entire narrative of art history as we know it, there is not a single black person who has achieved the title of Master. Certainly not an Old Master. Mastery means that one is able to self determine, to determine how one wants to be represented, how one wants to be seen. I tried to make a commitment to the craft. Everything about the picture is in my control. But I'm not working in a vacuum. I'm working in a culture that has a history. The goal was ultimately to be free and to not feel compelled to compromise ideals, vision, integrity in order to just fit in. And if ultimately the museum was a place that I wanted to go, I didn't have to abandon the black figure in order to get here. I decided early on you that have to be able to see evidence that I experience pleasure, that I experience pain, that I have desires, that I'm aware of history, that I'm a political creature, that I'm also a social creature. That's what it means to be a complete human being. I think that's true freedom."

For now, that's enough for us to think on the intersection of freedom and power. In future posts, I'll include more of my own thoughts on the subject. As we move into a new year, both freedom and power are much on my mind.

Jacqueline Davies's Blog

- Jacqueline Davies's profile

- 266 followers