Jacqueline Davies's Blog, page 2

July 2, 2019

Power...and Money

Oh, how I wish that statement were true.

Not the second part about authors’ earnings declining by nearly half in ten years; that part is appalling and destructive and disheartening and shockingly true.

The part that isn’t true is that most authors know about it. Or even know about the survey. And some don’t even know about the Authors Guild, which is the oldest and largest professional organization for writers in America. Among other things, it fights for fair contracts and a living wage for authors. If you’re a writer, you benefit from their efforts, whether you belong to the organization or not. It fights to protect us all.

So, when the Authors Guild does the most extensive survey of writing income ever (5,067 authors responded, including traditionally published, self-published, and hybrid authors) — and considering that income, our income, is not exactly a dull and distant subject that feels boring or irrelevant — you’d think more writers would be talking about it.

But among the children’s writers I spoke to (granted, just a small, non–scientifically selected sample), most didn’t even know about the survey. And many shrugged it off when I did talk about the contents. You know that shrug that children’s authors do whenever we talk about the newest unfair and exploitative term that has crept into our latest contracts, soon to become “industry standard.” (As examples, there’s the insertion of unreasonable morality clauses, as well as the publishers’ in toto hardline stance on negotiating audio royalties, which occurred when everyone in the industry at the very same instant recognized the enormous potential in the audio market as smart speaker sales grew 79% in 2018.)

The shrug that communicates Well, what can we do about it? It sure is a good thing I love writing so much, because I’m certainly not in it for the money! Ha ha! Almost cheerfully. Almost matter-of-factly. Almost…brainwashed. Shrug! Is there an emoji for that?

Anyway, I find myself asking two questions, and again, I’m just going to stick with the group I know best: those of us who write for the children’s market. The first is why don’t you know how much power you have lost? (Because money is power, more so these days than ever.) And the second is why, if you do know, aren’t you taking more of a power stance?

It all comes down to power. In business, it often does. And that, I suppose, is likely the first obstacle (or I might suggest escape hatch for authors who would rather not think about any of this) that authors summon up: Oh, I’m not a good business person. I’m an artist. Numbers! Contracts! I could never understand that stuff. Or even more likely: My agent takes care of all of that for me. So I can write.

And then I hear these same authors moaning about how they can’t get a response from their editor, or that she’s rejected a manuscript that she wouldn’t even sign up before it was complete and had gone through several revisions—after years of working together, both investing in each other’s careers. Or how their agent doesn’t return calls or send out their submissions with enthusiasm or speed. Or that their agent doesn’t even seem particularly interested in the author’s career. Or her own.

It’s all about the money.

And while editors are, in general, in my opinion (I have no data, but only anecdotal information), grossly underpaid for the valuable and voluminous work they do, I am positive that children’s book editors at the major houses have not seen their salaries decline by 42% over the past decade.

And furthermore, while declining author incomes would seem to indicate a commensurate decline in incomes for agents, I don’t believe that’s true either. I very much doubt (again, no hard data) that agents for children’s authors have, as a group, lost almost half of their annual income, as authors have. I think they’ve discovered the secret to maintaining or increasing their income: volume.

Agents are taking on more clients than ever. At many agencies, each agent represents around 50 authors and illustrators. Since I started rep’ing myself about three years ago, I’ve learned how much work goes into vigilantly and vigorously managing the agent side of this business. (I often say to people that my favorite thing about my agent (me) is that she has only one client (me)).

So, while author incomes have gone down, my guess is agents are combatting a similarly steep decline in their own annual income by taking on more clients. If so, they’re giving each client less attention, which is simply a result of the immutability of time: there are, always were, and always will be only twenty-four hours in a day. (Fun fact: actually, the Earth’s rotation slows down over time, so most days are usually a little bit longer than twenty-four hours, although today, July 2, 2019, will be 23.9999998668 hours long, or 24 hours minus 0.48 milliseconds. So, get going!)

My point is this, and it’s an important one: it seems to me that no other group, including agents, but even more significantly the people who work inhouse at the big publishers (editors, assistants, marketers, publicists, art directors, lawyers, contracts staff, subrights managers, content managers, digital content managers, new media developers, audio producers, publishers, vice presidents, presidents, etc.) has suffered a 42% decline in their salaries over the past ten years. Not one group. They might not be making as much as they’d like and they sure might not be making as much as they’re worth, but they aren’t making half as much as they were a decade ago.

So what gives? Why are authors making so much less while everyone else in the children’s book publishing food chain isn’t?

The answer is power.

So if you’re one of those authors who shrugs and says, Well, what can I do? I would suggest you take a moment, or a day, or a week, or a month, or a year—however long it takes—and locate your power. Because you are the one who creates. You start with nothing, nothing, and you make something: a story, a novel, a graphic novel, an audio script, or even a form that no one has ever imagined. Before putting your time and energy and faith and talent to work, there was nothing, and now there is something new in the world that has never existed before and that could come only from you. Take a moment to reflect on that.

And think that if you (all of us) hadn’t done that work, there would be nothing for the agent to sell. Nothing for the editor to edit. Nothing for the art direct to direct artistically, nothing for the cover designer to cover, nothing for the marketer to market, nothing for the publisher to publish.

Now create a picture in your head. Imagine all those people in that bustling, light-soaked, metal-polished, glassy, top-floor office in Manhattan that you visit once every few years suddenly sitting very quietly. Their hands folded in their laps, their glasses resting on their desks, their computers turned off, the phones silent.

Because they have nothing to do. Without the creators, the entire upside-down pyramid collapses. All those people, and the jobs they do, crumble. Without the creators.

So, no matter what stage of your career you’re at, please take a moment to ask yourself why the people who support the entire pyramid of publishing, the ones who make it possible for the industry to even exist, have lost 42% of their income in the past ten years when all the big trade houses posted gains in the first quarter of 2019, following a similarly robust 2018. (HarperCollins had a monster first quarter in 2019, with earnings jumping 29% over the comparable period in 2018.) Think about that.

And then get mad.

And then take back your goddamn power.

June 25, 2019

Today, I Bought a Watch

To repeat, today I bought a watch.

Not an Apple watch, an analog watch. (For those of you too young to know what analog means, look it up in the dictionary. For those of you too young to know what dictionary means, look it up on line.)

I’ve worn watches my whole life until—I didn’t. Can’t say why. The last watch died, and, well, by then I had a cell phone, so it looked like a good opportunity to eliminate a redundancy in my life. (I had three kids by then. Perhaps I had missed the boat on eliminating redundancies.) Why wear a watch if you always had a time piece (albeit an enormous, relatively heavy, rectangular one) with you?

Never mind that watches are elegant, eye-catching, distinctive, and just plain cool. It was unnecessary, now that I carried a smart phone with me whenever I left the house. (Never mind that I almost never used the smart phone. It was still a big, functioning watch.)

And let me clarify on the cell phone part: I was a very late adopter. In fact, I was the second-to-last person I know to get a cell phone. The other person still doesn’t own one. I think she’s über cool.

The reason I got a cell phone was because my children made me.

The reason I got a watch is because my cell phone died.

Well, first it got sick, and then it died. Actually, first it got sick, and then it got better, and then it got sold for parts. (Long story long: I was sitting with a friend at an outdoor café table and had my cell phone on top of a book on top of the table. The sun inched forward, and when I finally reached for my phone to show my friend a photo, the phone was kind of hot and the top half of the touch screen no longer worked. The next day, I took the (entirely cooled-down but still malfunctioning) phone to the Apple store at The Mall, and the nice, head-to-toe tattooed man told me that they would simply replace the screen and it would be good as new and ready at 12:30, which was in an hour and a half. He suggested I go get some lunch—which I did, because I often find the advice dispensed by head-to-toe tattooed men to be reasonable and worth following. And when I returned an hour and a half later, the very nice man told me they had accidentally stripped a screw while replacing the screen on the now-fixed phone, so they were giving me an entirely brand-new iPhone 10 for free. Because that’s what you do when you strip a screw. (Yeah, that story makes sense in some universe; I just can’t figure out which one.)

Anyway, for at least the last month I’d been considering buying a watch (after all these years of not wearing a watch which came after even more years of wearing a watch every single day) because I’ve been seriously evaluating my digital habits, and I realized that I really do check my phone to see what time it is…and then I see that I have email or a text or an app needs updating or there’s breaking news on the New York Times and is it going to start raining soon?…and then I’m off in digital land.

I’m consciously trying to make digital land more of a place I visit than live, but I still need to know what time it is so I can get places on time in the real (analog) world, and how else was I going to kill an hour and a half at The Mall? I’m a woman of limited imagination once I set foot in that ecosystem.

I went into three stores. I looked at three watches. I bought the cheapest.

I have to admit at the end of my first day with a new watch that I only looked at the face of the watch once, maybe twice. (Oddly, I had no appointments today, so it really didn’t matter what time it was.) But I did look at the shiny band a lot and thought it looked sort of elegant, definitely eye-catching, pretty distinctive, and just plain cool.

Hey, what are watches for?

I’ll also say that I didn’t look at my phone once, but that’s a different story for a different day.

I will relate one last bit of irony in this whole irony-laden venture, which is that as I finished my lunch (of course I managed to fit in eating in that hour and a half), I realized that I had been told by the nice tattooed man at the Apple store to return at 12:30 to retrieve my repaired phone, but I had no idea what time it was (not having bought the watch yet), so I asked the woman sitting next to me in the restaurant what time it was. I could see she had a nice big Apple watch on her left wrist, but in her left hand, she also held an iPhone, which she had been looking at while she ate. When I asked her for the time, she started to check her Apple watch, then stopped abruptly and tilted up her phone to look at it, but then stopped again and twisted her wrist to look at the watch, before finally consulting her phone one last time.

“It’s 12:29,” she said quietly. Then, she added, “No, wait. It’s 12:30.”

She looked exhausted.

June 17, 2019

The Lobster That Could Have Eaten My Car

So, I was heading south on Route 1 in Woolwich, Maine, having driven five hours from my home outside of Boston the day before and now returning home, when suddenly…and I do mean suddenly…there was a lobster.

And this lobster—the one I’m telling you about now—was the size of an eighteen-wheeler. From tip to tail and claw to claw, east to west and north to south. Forty feet at least in every direction.

And it was draped over the roofline of an unassuming, single-story, gray-shingled building—The Taste of Maine restaurant, which has been serving food (lobster, one presumes, though I admit that I haven’t checked the menu) for the past forty years.

This lobster…you see the picture, right?...was epic, and I mean that in the original sense of the word. Long-form poetry should have been written about this lobster. It could have been the Eighth Wonder of the Ancient World.

Except, of course, that it exists in the modern world, in fact, on Route 1 in Woolwich, Maine, in the tragically prosaic year of 2019.

Of course, the first question that occurred to me as the lobster first came into view was How in the world did I miss seeing that on my way up yesterday? I had taken the same route. It certainly hadn’t been put there in the middle of the night.

The second question, as I sped along the highway, making good time and eager to be home, was Are you really not going to stop? Really? You won’t spend even three minutes to look at what must surely be the largest fiberglass lobster in the world? What kind of person doesn’t stop for something like that?

Too often, me. But not that day.

So, after a few minutes of debating (Should I? I shouldn’t. But should I?), I pulled into a turnaround, drove a few minutes back up the road, parked across the street from the restaurant, and got out of my car to have a good look.

The oft-quoted opening lines from Mary Oliver’s “Mindful” poem came into my head:

Everyday

I see or hear

something

that more or less

kills me

with delight,

that leaves me

like a needle

in the haystack

of light.

To be clear, Mary Oliver is not talking about forty-foot fiberglass lobsters in this poem. She’s applauding “the ordinary, the common, the very drab, the daily presentations…” Encouraging us to find the needle of light in the haystack of what is most prosaic. But in that moment I could not deny that that great big hunk of nonsense draped like a burlesque dancer on the edge of a stage absolutely killed me with delight.

Poetry is entirely about understatement. This lobster knew nothing of that. And yet in its own way, it had called forth poetry, at least in me. It had encouraged me “to instruct myself, over and over in joy…”

And why not? Why not take joy in the absurd, in the foolishly human, in the overwrought redness of an extended crusher claw?

I have absolutely nothing profound or poetic to say about that big lobster. But I think, maybe, that might be the bigger point I was trying to grasp as I pulled my car to the side of the road, adding five minutes to a long journey from one place to another.

July 29, 2018

Equations

My effort to help books find their way into the hands of kids who need them (new books to keep, to own, to have forever) is off to a flying start...and hit its first bump...all in one week. To which, I say, HOORAY! If there weren't bumps along the way, I would find myself questioning the value of the journey. So bump #1 is: I'm going to rename the initiative.

Originally, I called it "Kids Need Books," but Jarrett Lerner helpfully pointed out that the wonderful Ann Braden had launched an earlier effort using that name (with the hashtag #kidsneedbooks). So I reached out to Ann and Jarrett, apologizing for inadvertently using the same name (bump!) and offering to change the name of my effort. They felt it was okay to keep both with the same name (very gracious and generous!), but upon reflection I've decided to change the name to avoid further confusion. So I'm now going to call my initiative kids+books—and I stand ready to apologize to anyone who might be using that name, too!

I strongly encourage everyone who would like to learn more and participate in Ann's project to visit http://annbradenbooks.com/2018/05/kid.... There, you'll see that Ann, too, was inspired by Donalyn Miller (that woman is inspirational) and her message of kids needing books.

So, a new name, a new week, a new day: kids+books. It's a good equation.

July 22, 2018

It’s Not That Complicated

So, an author walks into a literacy conference…

I know there’s a joke in there somewhere. When I figure it out, I’ll let you know.

Meanwhile…I went to NerdCamp Michigan 2018 a few weeks ago, which is basically a few thousand teachers, librarians, authors, illustrators, and other assorted ne’er-do-wells, assembling to talk crazy-talk about books, kids, reading, getting kids to read books…you get the idea. Nerding out about literacy.

I spoke about/led sessions on (1) service-learning projects tied to literacy, (2) One School One Book events, and (3) early chapter books. But I also attended every session I could, because there were so many brilliant people talking about things that profoundly interest me. NerdCamp is an avalanche of ideas, and I’ve decided my best approach is to let it bury me alive for the two days of the conference. And then…

…on the plane ride home, I sift and settle and see what is left poking up from the now-silent drifts. What are the things I’m still pondering as the plane lifts off from Detroit Metro Airport? What are the pieces of the puzzle of children’s literacy that keep rattling around in my brain, still demanding my attention? Do they fit together in some coherent way? Do they lead to action?

Well, this year: YES. Yes, yes, yes, in a really big way. Let me first tell you the fragments, the singular puzzle pieces I picked up over the two-day blizzard that is NerdCamp.

Fragment #1Donalyn Miller said the best way to get kids to read is to give new books to kids who need them. Give them new books. To keep. Forever. That’s it. Give a new book; make a reader. (There’s a ton of good research to support this strategy, but I’ll just include this info from a 2017 survey of 42,406 children aged eight to eighteen conducted by the National Literacy Trust in the UK: “Children who say they own a book are 15 times more likely to read above the level expected for their age than their peers who say they don’t own a book.”)

Fragment #2Donalyn has been speaking at literacy conferences for a long time, so it’s pretty understandable that she’s kind of had it with road blocks and excuses and red tape and all the things that keep good people from doing the good things they should and can do. Her refrain, repeated several times in her short talk: It’s not that complicated. We can figure out how to get books to readers in need. It’s not that complicated. Really? I wondered. It’s not that complicated? Inside my brain, everything is complicated. Hmm, let me think about that (as the plane climbed higher and Detroit fell away from view).

Fragment #3Alison Morris (@AlisonLMorris), along with Ro Menendez, Ashleigh Rose, and Meg Medina, gave a presentation on First Book, which is one of the greatest non-profits on earth. (Please go to their website right now and become a member and/or donate!) This from First Book: “Since 1992, First Book has distributed more than 175 million books and educational resources to programs and schools serving children from low income families in more than 30 countries.”

Whoa! That’s a lot of books. A massive number of books. Sitting in that room in Parma, Michigan, I was overwhelmed by the magnitude of the work First Book does. And while I’ve been a fan of First Book for years and always understood their mission, I never fully understood how they did their work. Now I get it. Because of Alison’s brilliant, organized presentation, I’ve seen a workable model for getting books into the hands of kids who need them.

Fragment #4And then there was Ro Menendez (@romenendez14). I still haven't actually met Ro, but she might be the new love of my life. (In the previous session I had led on early chapter books, her name had been mentioned by Jarrett Lerner with a certain hush of reverence that made me take notice.) Ro is a school librarian in Texas who uses First Book to get books for her kids to keep. During Alison’s info-packed, statistically grounded presentation, Ro kept popping up like a prairie dog with a Post-it note stuck to her index finger to provide yet another real-life example of a kid at her school who had received a book. Every couple of minutes, she’d interrupt Alison—pop!—and tell one more story with the same message: just do it. She made participation in this concept (getting books into the hands of kids who need them) seem like a no-brainer. Why wasn’t everyone doing this?

By now, we had reached our cruising altitude of 30,000 feet, and from that point on, there’s nothing left to do but ponder the enormity of the sky and the beauty of the world, marvel over the miracle of flight, and consider the fact that we’re all on earth for such a short period of time and that the time is always growing shorter. Never longer.

Putting all the puzzle pieces together, I landed in Boston with this personalized, synthesized takeaway from NerdCamp 2018: Kids need books. New books. Good books. Books they get to keep forever. In order to make this happen, I don’t need to reinvent the wheel. Instead, I can follow a stripped-down version of First Book’s model and create my own channel for getting books into the hands of kids who need them. I don’t need permission from anyone, I can just do it. And in the end, it’s not that complicated.

So, um, I did.

I set up a web page, and I’m calling my personal initiative kids+books. I’m inviting any teacher, librarian, or administrator of a Title I school to submit their names. Every month, I’ll pick one or more names from the list of registered participants, and then I’ll ship a carton of books at no cost to them. It’s up to the teachers, librarians, and administrators to decide how best to distribute the books I send. I trust them. (I needed to hear it two or three times, Donalyn, but I get it now: It’s really not that complicated.)

And yes, I know this is just a drop in the bucket. I can’t get a book into the hands of every child who needs one. But it’s something, and it’s what I can do for now, so here goes. Learning on the fly.

And if you’re reading this blogpost (and all the way to the end, bless you), I’d like to ask a favor. Could you please spread the word? Using whatever tools you have at your disposal, let as many teachers, librarians, and school staff know about the initiative. Pass along the website address (http://www.jacquelinedavies.net/kids-...). It’s true, not everyone who registers will get free books, but many will, and I’m going to try my hardest to get as many books out as I can.

And if you’re an author or illustrator and any of this makes sense to you (and you have the means to give free books to kids who need them), then consider doing it. You don’t have to follow my model. You can figure out your own way. Because any way is better than no way.

It’s really not that complicated.

It's Not That Complicated

So, an author walks into a literacy conference…

I know there’s a joke in there somewhere. When I figure it out, I’ll let you know.

Meanwhile…I went to NerdCamp Michigan 2018 a few weeks ago, which is basically a few thousand teachers, librarians, authors, illustrators, and other assorted ne’er-do-wells, assembling to talk crazy-talk about books, kids, reading, getting kids to read books…you get the idea. Nerding out about literacy.

I spoke about/led sessions on (1) service-learning projects tied to literacy, (2) One School One Book events, and (3) early chapter books. But I also attended every session I could, because there were so many brilliant people talking about things that profoundly interest me. NerdCamp is an avalanche of ideas, and I’ve decided my best approach is to let it bury me alive for the two days of the conference. And then…

…on the plane ride home, I sift and settle and see what is left poking up from the now-silent drifts. What are the things I’m still pondering as the plane lifts off from Detroit Metro Airport? What are the pieces of the puzzle of children’s literacy that keep rattling around in my brain, still demanding my attention? Do they fit together in some coherent way? Do they lead to action?

Well, this year: YES. Yes, yes, yes, in a really big way. Let me first tell you the fragments, the singular puzzle pieces I picked up over the two-day blizzard that is NerdCamp.

Fragment #1Donalyn Miller said the best way to get kids to read is to give new books to kids who need them. Give them new books. To keep. Forever. That’s it. Give a new book; make a reader. (There’s a ton of good research to support this strategy, but I’ll just include this info from a 2017 survey of 42,406 children aged eight to eighteen conducted by the National Literacy Trust in the UK: “Children who say they own a book are 15 times more likely to read above the level expected for their age than their peers who say they don’t own a book.”)

Fragment #2Donalyn has been speaking at literacy conferences for a long time, so it’s pretty understandable that she’s kind of had it with road blocks and excuses and red tape and all the things that keep good people from doing the good things they should and can do. Her refrain, repeated several times in her short talk: It’s not that complicated. We can figure out how to get books to readers in need. It’s not that complicated. Really? I wondered. It’s not that complicated? Inside my brain, everything is complicated. Hmm, let me think about that (as the plane climbed higher and Detroit fell away from view).

Fragment #3Alison Morris (@AlisonLMorris), along with Ro Menendez, Ashleigh Rose, and Meg Medina, gave a presentation on First Book, which is one of the greatest non-profits on earth. (Please go to their website right now and become a member and/or donate!) This from First Book: “Since 1992, First Book has distributed more than 175 million books and educational resources to programs and schools serving children from low income families in more than 30 countries.”

Whoa! That’s a lot of books. A massive number of books. Sitting in that room in Parma, Michigan, I was overwhelmed by the magnitude of the work First Book does. And while I’ve been a fan of First Book for years and always understood their mission, I never fully understood how they did their work. Now I get it. Because of Alison’s brilliant, organized presentation, I’ve seen a workable model for getting books into the hands of kids who need them.

Fragment #4And then there was Ro Menendez (@romenendez14). I still haven't actually met Ro, but she might be the new love of my life. (In the previous session I had led on early chapter books, her name had been mentioned by Jarrett Lerner with a certain hush of reverence that made me take notice.) Ro is a school librarian in Texas who uses First Book to get books for her kids to keep. During Alison’s info-packed, statistically grounded presentation, Ro kept popping up like a prairie dog with a Post-it note stuck to her index finger to provide yet another real-life example of a kid at her school who had received a book. Every couple of minutes, she’d interrupt Alison—pop!—and tell one more story with the same message: just do it. She made participation in this concept (getting books into the hands of kids who need them) seem like a no-brainer. Why wasn’t everyone doing this?

By now, we had reached our cruising altitude of 30,000 feet, and from that point on, there’s nothing left to do but ponder the enormity of the sky and the beauty of the world, marvel over the miracle of flight, and consider the fact that we’re all on earth for such a short period of time and that the time is always growing shorter. Never longer.

Putting all the puzzle pieces together, I landed in Boston with this personalized, synthesized takeaway from NerdCamp 2018: Kids need books. New books. Good books. Books they get to keep forever. In order to make this happen, I don’t need to reinvent the wheel. Instead, I can follow a stripped-down version of First Book’s model and create my own channel for getting books into the hands of kids who need them. I don’t need permission from anyone, I can just do it. And in the end, it’s not that complicated.

So, um, I did.

I set up a web page, and I’m calling my personal initiative Kids Need Books. I’m inviting any teacher, librarian, or administrator of a Title I school to submit their names. Every month, I’ll pick one or more names from the list of registered participants, and then I’ll ship a carton of books at no cost to them. It’s up to the teachers, librarians, and administrators to decide how best to distribute the books I send. I trust them. (I needed to hear it two or three times, Donalyn, but I get it now: It’s really not that complicated.)

And yes, I know this is just a drop in the bucket. I can’t get a book into the hands of every child who needs one. But it’s something, and it’s what I can do for now, so here goes. Learning on the fly.

And if you’re reading this blogpost (and all the way to the end, bless you), I’d like to ask a favor. Could you please spread the word? Using whatever tools you have at your disposal, let as many teachers, librarians, and school staff know about the initiative. Pass along the website address (http://www.jacquelinedavies.net/kids-...). It’s true, not everyone who registers will get free books, but many will, and I’m going to try my hardest to get as many books out as I can.

And if you’re an author or illustrator and any of this makes sense to you (and you have the means to give free books to kids who need them), then consider doing it. You don’t have to follow my model. You can figure out your own way. Because any way is better than no way. And Kids Need Books.

It’s really not that complicated.

June 2, 2018

Excuse me, sir? Did you forget something?

Imagine this: You go to a swank hotel, and you’re totally digging the fantastic amenities—state-of-the-art fitness center, Olympic-sized pool, fabulous brunch buffet, jacuzzi tub in the room—until you discover that (surprise!) you’ve been treated to something that wasn't advertised in the brochure: bed bugs. Ugh. You know the feeling: you went for one thing, but came home with something completely different. And now you have to burn all your clothes and throw away your luggage because yuck. And the only thing you remember about that hotel—the only thing you will ever remember about that hotel—is the bed bugs.

Well, I had an experience like that when I attended a recent two-hour workshop on children’s book illustration. I didn’t come home covered in red, itchy bumps, but I definitely went for one thing and sadly came home with something I hadn't asked for.

Here’s how it happened.

At a recent writing conference, I attended a workshop that was billed as a “two-hour crash course in art school.” Awesome! I thought. That’s about as much time as I have to devote to art school at the moment.

The lecture delivered on much of what it promised: I learned about hue, saturation, value, and temperature. I learned about composition and the basic four-color palette. I learned about the all-important "first read" of an illustration. The lecturer was knowledgeable and organized. He clearly knew his stuff.

But…here come the bed bugs.

About five minutes into the lecture, I noticed that the first four names that the artist/lecturer referenced (and presented as illustrators to study) were men. My recent involvement with The KidLitWomen project had sharpened my awareness of this imbalance in our industry: male illustrators receive a disproportionate amount of attention, dollars, and awards in the world of children’s literature. Women illustrators (and particularly illustrators who are women of color) have a hard time getting noticed at all, let alone walking away with the big awards.

Getting noticed matters in this business.

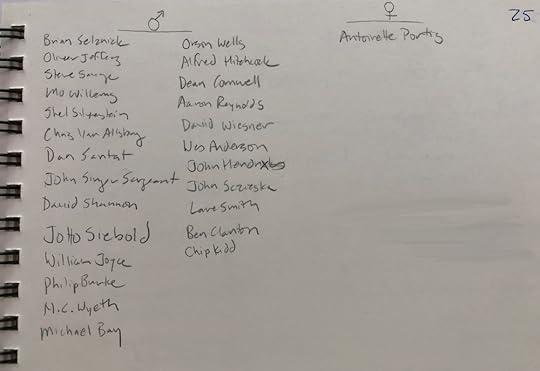

A thought occurred to me: It would be interesting to see how the male/female imbalance might play out in this one two-hour session. I started jotting down every name that the lecturer mentioned. Many were children’s book artists, but others were filmmakers, art critics, fine artists, designers, and others. These were the people that the lecturer held up as models to the audience. His message was, These are the people I have learned from in my extensive (and expensive!) art school education, and these are the people you should learn from, too.

Over the course of the two-hour lecture, 26 names were referenced in total; 25 of them were men. The only woman who was referenced at all during the two hours was mentioned in the last ten minutes and only in passing. I don’t even remember what was said about her, the reference was so brief. Her name was spoken once by the lecturer, and none of her work was shown on the screen. Male references: 96%. Female references: 4%.

Page from my notebook noting the references made by the lecturer.

Being referenced leads to getting noticed, which matters in this business.

And (here’s the bed bug part) while the content of the lecture was valuable, the only thing I will ever remember about that lecture is that women were practically shut out. There could be no denying it. I had the stats staring me in the face.

During and after the lecture, I was hyper-aware of the unspoken message that was delivered that day. But I’m sure that many people in the audience (who were overwhelmingly women) walked away absorbing the message unconsciously, which of course is the most powerful way to take in a belief. The belief being: the best of the best in children’s book illustration are men. The belief being: If you’re a woman illustrator, your work is second-rate. The belief being: In the world of children’s book illustration, men matter and women do not. They’re barely worth mentioning. They hardly exist.

So the people in the audience (to repeat, mostly women) went home without knowing that they’d been infested with bed bugs. And they brought those bugs into their own houses and into the intimacy of their own beds (which I will liken to their subconscious minds), and those bugs are going to cause all kinds of harm. And then, like the worst infestations, they will spread. Women thinking, I don’t deserve to be noticed. I don’t deserve to win awards. I don’t deserve as much money as my male counterparts. And right now, I just want to shout: It’s not true! It’s just the damn bugs you brought home with you!

I would guess that the lecturer doesn’t realize that he references only men. I could be wrong, but it wouldn't amaze me if his response to seeing the list from my notebook would be one of genuine surprise. I’m going to give him the benefit of the doubt and assume he is unaware; that is, he isn’t purposefully, mindfully, intentionally excluding women.

But that’s the worst part of this experience. The really yucky bed-buggy part. He went to an elite art school. He studied. He learned. He graduated with distinction. He was consciously taught by the best of the best. And what he came away with after four years and $200,000—the knowledge he absorbed down to his cellular level—is that male artists matter and female artists hardly exist at all.

Because these are the names (look at them again in my notebook) that are presented over and over as the canon of children’s book illustration. These are the artists and thinkers that today’s art students study and emulate and learn to value and revere. And this male-created art is the well that all artists drink from. And then that artistic sensibility is absorbed and is expressed in the work of today’s illustrators (male and female). And then, that male sensibility is passed on to the next generation of art students who want to make children’s book art. And we all drink from this well—art directors and editors and librarians and teachers and writers and reviewers and parents and readers. The curated importance of the male perspective flows through all of us: from centuries ago through to the present and then on into the future.

And until we all, male and female, consciously and purposefully and mindfully and intentionally audit our own immediate responses and take the time to consciously and purposefully and mindfully and intentionally correct the imbalance that we can see when we total up and examine the names we reference, the gender imbalance that hurts all of us will persist.

The presenter gave much to his audience during his two-hour lecture. He owed us more. He owed us the care and concern to review his lecture through the lens of gender equity so that he could teach without doing harm. If he had chosen (and it is a choice) to be more self-aware, he could have taught us about illustration technique without giving us a bad case of bed bugs.

_____

Here are a few more articles/radio shows about why we need to audit our own content to promote gender equity:

“On Point: Tackling the Gender Imbalance in News Media,” NPR, May 24, 2018.

“I Analyzed a Year of My Reporting for Gender Bias (Again),” by Adrienne LaFrance, The Atlantic, February 17, 2016.

“Introducing Sourcelist: Promoting Diversity in Technology Policy,” by Susan Hennessey, The Brookings Institution, May 14, 2018.

“I’m Not Quoting Enough Women,” by David Leonhardt, The New York Times, May 13, 2018.

March 24, 2018

Women! Read Your Royalty Statements!

We're celebrating Women's History month with 31 days of posts focused on improving the climate for social and gender equality in the children’s and teens' literature community. Join in the conversation on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/kidlitwomen or Twitter #kidlitwomen

There’s an old joke: What’s the difference between a children’s author and a park bench?

Answer: A park bench can support a family.

Many of us in the world of children’s publishing (#KidLitWomen) are talking about pay equity and fair pay in our business. I’m going to address one small piece of the puzzle. I’m writing this to women who are authors and illustrators, but I think people of all genders and in many work situations can get something out of this discussion. Because the bottom line is…

If you want equality (as Malcolm X said) you have to take it. Because no one is going to give it to you. And in order to take equality for your own, you need to value yourself. And in order to value yourself, you need to arm yourself with the knowledge of your worth. And in order to arm yourself with the knowledge of your worth, you need to...(wait for it)…read your royalty statements!

Okay, calm down. Just calm down! I hear you screaming. I see you running for the door. I smell your fear.

I know you have a long and impressive list of reasons why you only glance at your royalty statements. (And some of you don’t even do that!) Let me list your Top Ten reasons:

All I need to know is the final number, and that’s printed on the check.Royalty statements are generated by computers and therefore cannot contain errors.My agent reviews all my royalty statements.I don’t understand my royalty statements, so looking at them will just make me feel insecure and bad about myself. I don’t have time. They’re so boring!The type is too small.I’m no good with numbers.The financial side of writing doesn’t matter to me—I write for art!If I look too closely at my royalty statement, I’ll just end up depressed.Did I get them all? Maybe you have a few more in your pocket? Behold as I decapitate every one of those ten “reasons.” (Um, let’s be honest and call them excuses.)

1. All I need to know is the final number, and that’s printed on the check.

Actually, the check tells you just one thing: how much you earned. The royalty statements, however, tells you how you earned your money, which is way more important. You can’t change how much you earn until you understand how you earn it. As an author or illustrator, you are running a business, and the details of your royalty statement give you vital information about the way your business functions.

2. Royalty statements are generated by computers and therefore cannot contain errors.

Computers rely on human data entry. Mistakes are made on royalty statements all the time. All. The. Time. I recently discovered an error in which my publisher (truly by accident!) failed to report 125,716 copies sold over a three-year period. Those sales had been mis-categorized by a person in their royalty department who interpreted contract language incorrectly. It was an honest mistake (and an understandable one—don’t get me started on the ambiguous language of book contracts!), but I’m glad I caught it by reading my royalty statements carefully.

3. My agent reviews all my royalty statements.

Uh, no. Your agent probably has 50–100 clients. She doesn’t have time to review your individual royalty statements.

4. I don’t understand my royalty statements, so looking at them will just make me feel insecure and bad about myself.

Listen to me. They’re not that complicated. Trust me, you can understand them, and I’m here to help you. And once you do look at your royalty statements, you’ll feel extra good about yourself!

5. I don’t have time.

If you don’t have time to look at your royalty statements (i.e., run a business), then you can’t complain about anything related to your career. Anything. Because it’s all related: royalties and advances and future book contracts and marketing dollars and whether your house picks up your next book and who you get to work with and whether your editor (or agent) prioritizes your career…It’s all part of the same thing: your business. So here's my advice in terms of time: skip the latest episode of Game of Thrones and read your latest royalty statement instead. (And then go back and catch up on Game of Thrones.)

6. They’re so boring!

Royalty statements are NOT boring. They’re fascinating. They reveal secrets about your sales that you wouldn’t believe. Who doesn’t love a secret?

7. The type is too small.

Get a magnifying glass. And a good light.

8. I’m no good with numbers.

Get a calculator. You don’t have to do anything more complicated than addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. And I’ll explain the (simple) math each step of the way.

9. The financial side of writing doesn’t matter to me—I write for art!

Well, that’s great. It must be nice not to care about the money you earn from your work. I mean that! Truly! BUT do you care about being treated fairly? Do you care about gaining respect? Do you care about having some power over the work you do? Do you care about the marketing dollars allocated to your books and whether your next book will be picked up? If so, you need to understand how you’re paid, because money = power in business, and YOU, dear artist, are running a business.

10. If I look too closely at my royalty statement, I’ll just end up depressed.

This is a very real concern. Yes, looking at one’s royalty statement (and truly understanding it) can lead to depression. I’ve felt it many times myself. But depression can lead to (righteous!) anger, which can lead to an awakened sense of injustice, which can cause you to act, which can lead to positive change. And even if you decide not to pursue change, it’s always better to know. Because knowledge = power, even if the power is simply the power of being well informed.

So enough! Basta! No more excuses. Take out a recent royalty statement and sit down with me. This won’t take more than ten minutes, and you know you’re a little curious…

Okay, first things first. Every publishing house’s royalty statement looks different from every other house’s statement. But they all share some commonalities. What makes them the same is more important than what makes them different.

Most statements begin with a summary and then move on to a detailed accounting of each sale. I’ve posted an example of a royalty statement for a picture book of mine. Here’s the link. This royalty statement is actually four pages long, but I cut-and-pasted it onto a single page for ease of reference. So follow along with this example, and then try to find the same elements on your royalty statement.

First, you’ll see that I drew a thick black line and divided the statement into SUMMARY and DETAIL. The summary (overview) shows me that there are two categories of editions for this statement: Hardcover and eBook. There are also Subsidiary Rights earnings reported on this statement. (I’ve gone ahead and highlighted/color-coded the detailed information for each of these three areas of information: Hardcover is orange; eBook is blue, and Subsidiary Rights is pink.)

You might have many more categories on the summary page of your royalty statement. (Some of my statements have up to eight.) That’s okay. The process is the same; you’ll just need more colored highlighters.

The summary on my royalty statement shows that I earned $2,326.56 from Hardcover sales; $103.62 from eBook sales; and $343.40 from Subsidiary Rights sales, for a total of $2,773.58.

Right off the bat, I can see that I earned 84% of all my money from hardcover sales:

hardcover earnings ÷ total earnings

$2,326.56 ÷ 2,773.58 = 0.838 or 84%

That doesn’t surprise me for a picture book. However, I have other books where my eBook earnings are the lion's share of my earnings. It’s always good to understand the sales profile of each book and to understand that each book is unique in its sales profile.

Remember! Each royalty statement provides a snapshot of a moment in time: a mere six months’ of sales. What you see on one statement for a book may be very different from the previous statement or the next statement for the same book. Hopefully your books will stay in print a long time and you can build a long-term profile of each book’s sales.

Now let’s look at the details. Let’s start with the Hardcover sales. That’s the portion of the statement boxed in orange. Notice there are two editions of the hardcover book: one costs $17.99 (the trade edition) and the other costs $20.99 (the library binding edition). Only 14% of my hardcover sales went to libraries.

library binding sales ÷ total hardcover sales

376 ÷ 2630 = 0.1429 or 14%

It’s good for me to understand that this book has a much stronger presence in the trade market than in the school and library market.

[TRUE STORY: I prepared this blogpost at the beginning of March, and about a week later, I received the dreaded Remainder Letter from my publisher. I freaked out! How was it possible this particular title (which was selling steadily and was less than two years old) was being remaindered? Then I noticed that it was only the library binding edition that was being remaindered. Oh, of course! I thought. I already knew from my royalty statement that the library binding edition was underperforming. It made perfect sense that the publisher was remaindering that stock. But without that knowledge from my royalty statement, I would have been confused and depressed. Side note: I bought every last remaindered copy from the publisher at the cost of manufacture; I will easily sell those books at school visits. (This title is a bestseller for me at school visits.) Conservatively, I'll earn $10,000–$14,000 from the sale of those books. Good business.]

Okay, back to the royalty statement.

Let’s look more closely at the trade edition. Ignoring external sales to Australia, this book sold into six categories/territories. The first category is “U.S. First 25000”. What does that 25000 mean? It means that I have an escalation clause in my contract, and so I’m paid a lower initial royalty on the first 25,000 copies of the book that sell, and then after 25,000 copies have sold, my royalty rate will go up a little. (Questions to ask yourself: Do you have an escalation clause in your contract? Is it reflected properly on the royalty statement?)

The second category is Canada, and clearly they hate my book because they returned 99 copies of it. That’s what the parentheses around the number mean: it’s a negative number. You’ll see that these returns translated into a loss for me of $59.37. Feh on Canada.

For the sales to the US and Canada, I receive my straight royalty of 5%. (The illustrator receives 5%, too; together, we earn the standard 10% royalty.) Let’s multiply the royalty rate by the list price of the book: 0.05 x $17.99 = $0.89950. You’ll see that number listed under “Royalty Per Unit or Net Receipts.” It means that I earned approximately 90¢ every time a book sold in that first category (US First 25000). Because 2,054 books sold in that category, I earned $1,847.57 ($0.8995 x 2,054 = $1,847.57). So far, so good.

You can do the same calculations across to see that I “lost” $59.37 on my Canadian sales. (A pox upon the Canadians!) Notice that my royalty rate for Canadian sales is lower than for sales in the US. I earn only 3.3333% on each sale, or approximately 60¢. (This means I “lost” less money than I would have at my full 5% royalty. Ha ha, Canadians!)

But what happens in the next four categories: Export; Spcl disct; Spcl Sales; and Premium? The number in the “Royalty Per Unit or Net Receipts” column suddenly jumps! Instead of 90¢ per copy or 60¢ per copy, we’re suddenly seeing $175.43; $5.40; $62.97; and $557.68. What does this mean?

The change is due to the fact that for these sales (Export, Special Discount, Special Sales, and Premium) the payment structure completely changes. Before, each sale earned me a percentage of the list price of the book. Now, in these new categories, I am earning a percentage of “net,” which is defined as what the publisher sold the book for. You'll see that it’s significantly less than the list price.

Let’s look at a simple example from this royalty statement: “Special Discount”. Do you see it on my sample royalty statement? Only 1 book sold in this category. But it sold for $5.40. What? you say. The list price for that book is $17.99. How could it sell for $5.40? That would be a discount of 70% off the list price! To which I would answer, Yep.

Sales of our books at discounts of 70%–84% off list price are common, and it’s important that we understand the impact of these deep-discount sales on our earnings.

So let’s quickly do the math for each category (net receipts ÷ copies sold = price per copy). I’ve highlighted the price per copy in bold, as well as the amount of the discount.

Export ($175.43 ÷ 29 = $6.05) That’s a discount of 66% off the list price.

Special Discount ($5.40 ÷ 1 = $5.40) That’s a discount of 70% off the list price.

Special Sales ($62.97 ÷ 10 = $6.30) That’s a discount of 65% off the list price.

Premium ($557.68 ÷ 62 = $8.99) That’s a discount of 50% off the list price.

So how much am I earning per book for those sales? Export, Special Discount, and Special Sales all earn me 5% of the net amount. (Look under the column titled “Royalty Rate or External Market.”) But Premium sales on this book earn me only 2.5% of the net amount. That’s half! So here’s what I’m earning per book in each of these different categories (highlighted in bold).

Export (0.05 x $6.05 = 30¢)

Special Discount (0.05 x $5.40 = 27¢)

Special Sales (0.05 x $6.30 = 31.5¢)

Premium (0.025 x $8.99 = 22¢)

Ouch. That last one hurts. From a full royalty of 90¢ per book to a drop of 22¢ per book. I’d have to sell four copies of Premium sales books to equal just one copy of a regular sale book. The reason is that both the price of the book drops and the percentage I receive of that lower price drops. It’s a double whammy. (Questions to ask yourself: Are there "Premium" sales on your royalty statement? Does your contract require your Publisher to get your approval for Premium sales? Was your approval secured?)

These are the economics of being an author or illustrator. And it’s vital that we understand how we make (or don’t make) our money.

For this royalty statement for this book, the vast majority of my sales earned their full royalty of 90¢ per book. Here’s the breakdown by percentage, adjusted for those pesky returns from Canada:

US First 25000 95%

Export 1%

Special Discount < 1%

Special Sales < 1%

Premium 3%

I feel good about the fact that this particular book is selling mostly in the trade market and into sales channels from which I earn my full royalty. However, I have other books where the numbers are reversed: the vast majority of sales fall into the “Premium” or “Deep Discount” category. That isn’t necessarily bad, but it’s something I need to know about my business, and it’s knowledge that will help me make future decisions about how I run my business.

That’s most of what I want to say on royalty statements in this one blogpost. I might tackle further topics related to royalty statements in the future, if readers are interested. But let me quickly address the information in the blue and pink boxes.

First, the blue box. This is information about eBook sales. The first thing you should notice is that there are four editions at four different prices: $53.97; $17.99; $11.00; and $10.99. Did you know that eBooks are sold in so many different formats? This is an area I’m continuing to learn about. I know that the most expensive category is Audio CDs, and those are sold mostly to the school and library market. I know that the least expensive category is Kindle. I don’t know what those two middle categories are. As I continue to learn about audio (which, by the way, is potentially the hottest, about-to-explode segment of sales in children’s books, thanks to the advent of Smart Speakers), I plan to learn more about these different formats.

And finally, the pink box: Subsidiary Rights sales. One sale here: the publisher sold Book Club rights to the Junior Library Guild for $1,373.60. The publisher kept 50% of that amount, and both the illustrator and I received 25%, or $343.40. Pretty standard stuff, but I’ve had some books where the subsidiary rights earnings over the lifetime of the book were more than ten times the amount I earned through royalties. Some books do great in subrights, and others not so much.

So that’s a quick intro to royalty statements. The more you review them, the easier it becomes to understand them. You’ll notice that the painful figure (22¢) for the “Premium” earning per book doesn’t appear anywhere on the statement. My guess is the publishers don’t want us to know some of these numbers. Or think about them. Or maybe get a little irritated by them.

And maybe you don’t want to get irritated either. But knowledge is power. Without knowing our business—what we make and how we make it—we have nothing. We can’t even begin to fight for pay equity and pay fairness if we don’t understand what we’re being paid and why. So…unless you want to be a park bench your whole life…

Women! Read your royalty statements!

March 16, 2018

The Shaming of Desire

I was flipping through the latest issue of Vogue while waiting for a prescription refill at CVS when I read this from new-mom Serena Williams:

“To be honest, there’s something really attractive about the idea of moving to San Francisco [where her husband’s company, Reddit, is headquartered] and just being a mom. But not yet. Maybe this goes without saying, but it needs to be said in a powerful way: I absolutely want more Grand Slams. I’m well aware of the record books, unfortunately. It’s not a secret that I have my sights on 25.”

Whoa! That’s not what you usually hear from a brand-new celebrity mom who’s featured on the cover of a glammy women’s magazine. Where’s the snuggling? Where’s the cooing? Where’s the nesting? Where’s the Madonna-and-child soft-focus photo? (To be fair, there is a picture of Serena holding her baby, but she’s holding the child in the crook of one arm and looks like she could bench press the kid a hundred reps without breaking a sweat.)

Here are the things I love about Serena Williams:

I love her massive arms and pile-driving legs. I love her wide, open smile.I love her power. I love her complicated, loving, loyal relationship with her sister, Venus. I love it that she won the women’s title at the Australian open when she was eight weeks pregnant. I love it that she wins, period. She wins and wins and wins. I really love that about her.It isn’t easy for a woman to express desire. To say, “I want this.” To say it in a powerful way. To say it without equivocation, without apology, without mumbling and backtracking and trying to hide it in a bouquet of qualifiers. But to say it in print in a national magazine—"I absolutely want more Grand Slams"—that takes ovaries of steel.

I just got back from two weeks of school visits in Chicago, and one of the things I talk about in my presentation with the upper elementary kids is character motivation. I explain that a story’s main character needs to want something in order to move the plot forward. I explain that everybody wants something. And then I ask slyly, “What do you want?”

The boys’ hands go up first. A lot of them want Nintendos and money and to play in the NBA. A surprising number want Lamborghinis. Sometimes their answers are wisecracks, and sometimes they’re heartfelt. On this trip, a fourth-grade boy bravely admitted that he wanted friends because he was new to the school.

The girls are usually a beat behind the boys in telling me what they want. They sometimes want money, too. But more often I hear about wanting a particular pet or a phone or some form of self-improvement. (I want to get good grades; I want to be nicer to my sister.) Occasionally, a girl expresses a desire for world peace, and I often find myself wondering what that concept means to her. Where did she hear that phrase? And has she already accepted the cultural norm that boys belong to the world of war, while it is the job of women to bring peace? I’m sure boys desire world peace, too, but it doesn’t occur to them in the moment. At least, not before Lamborghinis.

Are boys and girls taught to want different things? Or is it that boys absorb the message that it’s okay to want, while girls (who grow into women) approach the subject of desire with a little more trepidation? The waters are muddy for women who want. Muddy and filled with crocodiles. Data shows that neither men nor women like women who want. For this reason, women are sometimes coached to ask for a raise by invoking their family’s need—never their own value or their own needs.

This year, the movie Battle of the Sexes reanimated the 1973 tennis match between Billie Jean King and (what’s his name? it’s hard to even remember), oh, yes, Bobby Riggs. I was a feisty eleven-year-old feminist when the match took place, and I remember thinking there’s no way an old has-been like Riggs is going to beat the World’s No. 1 tennis player. A woman who would win 12 Grand Slam singles titles in her career and who fought just as hard for women’s rights, including equal pay. But Bobby sure did shoot his mouth off, and he could almost make you believe just by saying it was so.

The match was an absurd spectacle, built for entertainment appeal, but it also mattered. Intensely. And not just to 11-year-old feminists who wanted to believe that women could be equal to men—and even victorious over them. Fifty million people watched the televised match in the United States alone. Another 90 million watched worldwide. Later, King would say, “I thought it would set us back fifty years if I didn’t win that match. It would ruin the women’s tour and affect all women’s self-esteem.” King beat Riggs in three straight sets.

In the movie, one of the characters asks, “Billie Jean, what do you want?” The eternal question. It can be so hard for women to locate desire—desire that has nothing to do with nurturing others.

I spent years writing in closets. (Literally. When I was seven, I commandeered a linen closet as my writing office. My mother moved the sheets to a higher shelf and maneuvered around my chair.) As I grew older, I learned to hide my writing in other ways. All the years I was a young mother, I was writing, but I never told anyone. I was too ashamed. Not ashamed to be a writer; ashamed of wanting to be a writer. Ashamed of the desire. The arrogance of desire. Who was I to want to write?

(Later, when I was teaching at a university in a low-residency writing program, one of my students, who was a successful, working actress in L.A., admitted that not even her closest friends knew where she went when she traveled East twice a year for the residencies. She let them believe that she was having “work done.” In her world, it was less humiliating to have plastic surgery than to have desire.)

Serena Williams wasn’t alive in 1973, but she remembers the lessons of that time. Speaking of other women tennis players, she said,

“I really believe that we have to build each other up and build our tour up. The women in Billie Jean King’s day supported each other even though they competed fiercely. We’ve got to do that. That’s kind of the mark I want to leave. Play each other hard, but keep growing the sport.”

In Battle of the Sexes, the character of Billie Jean King says to one of the smirking, condescending male promoters, “When we dare to want a little bit more, just a little bit of what you’ve got, that’s what you can’t stand.” Forty-five years later, we’re having the same conversation.

Last year I found myself seated around a large conference table at my publisher’s downtown corporate headquarters. We were negotiating contract terms, and had been for almost two years. There were four women in the room: the Senior Vice President and Publisher, the Vice President of Sales and Children’s Marketing, the Vice President and Editor in Chief—and me. They sat on one side of the table, I sat on the other. The question was raised by the Publisher: What did I want, specifically?

I knew exactly what I wanted, but saying it out loud felt impossible. For fives minutes, I talked around the question. I spoke in broad outline. I made reference to related topics. I advanced and then retreated. I left sentences unfinished. I apologized for a poorly chosen word. Essentially, I was rearranging furniture: moving the couch, straightening the rug, adjusting the coffee table. But I wasn’t answering the question.

Eventually, I just ran out of words. I was out of moderate responses. Out of soft generalizations. Out of euphemisms. Out of time. There was nothing left to say except the thing itself. “I want more money,” I said, shocking myself. And then, because the world didn’t explode and no one in the room threw knives at me, I said it again. “That’s it. I want more money.”

Later, when the negotiating part of the meeting had ended and we had moved on to safer topics, the Vice President of Sales—a woman who seems unflappable, never at a loss for words, and ever capable of stating her position with clarity—looked at me across the table. Our eyes locked. It felt to me as though her eyes pierced mine. She said in a low voice, directly to me, “Don’t ever apologize for asking for money.”

Daring to want. For women, it’s an act of subversion. It’s an act of resistance. And it often feels like it holds the potential to be an act of destruction. (What do we fear we might destroy? Our careers? Our chance to be loved? The system that discriminates against us?) Daring to want: a writing contract. An award. A seat on a panel. Fair payment. Attention. Respect. Power.

“Women are sometimes taught to not dream as big as men,” said Serena Williams, who is the greatest tennis player—male or female—of all time. “I’m so glad I had a daughter. I want to teach her that there are no limits.”

I visited eleven schools over the past two weeks in Chicago, and I told the students the same thing over and over: every story is about motivation, the thing your character wants more than anything else in the world. I wish I could tell the girls you have every right to want as much as the boys. Don’t be ashamed of wanting. Name your desire. Say it out loud. And go after it.

March 1, 2018

The Conversation

We're celebrating Women's History month with 31 days of posts focused on improving the climate for social and gender equality in the children’s and teens' literature community. Join in the conversation on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/kidlitwomen or Twitter #kidlitwomen

I want to tell you the story of a conversation—a conversation between two women, two colleagues, two friends. Because I think you’ve probably had a conversation like this at some point in your career. And if you haven’t, you probably will.

The background to this conversation is simple, familiar, and largely irrelevant. I was working in an organization in which the men were paid more than the women by virtue of being given more assignments. More assignments meant more pay. After a few years with the organization, I began to raise the question of how assignments were handed out. I asked questions of the male director, who gave the assigments. (Was it seniority? rotation? matching assignment to writer?) I invited all the members of the group into the conversation through all-group emails: soliciting their input, listening to their perspectives, and expressing my own thoughts and feelings on the subject. It was important to me that the discussion include everyone, even the men, who I knew wouldn’t be too jazzed by the topic.

Now comes The Conversation.

The most senior woman in the group called me on the phone. Let’s call her Julia, because I like that name and I still like this woman, even though we’re not in touch any longer.

Julia had been with the organization since its beginning, over a decade before I joined. She was more than ten years older than I was. I respected her intelligence and experience. I appreciated her forthrightness. I admired her work. I liked her humor. And I considered her a mentor in terms of working within the organization. We had also, over the years, become friends and were peers in our professional world outside the organization.

Julia began The Conversation by saying that when she looked at me she was reminded of her younger self. She said that she had made the same mistakes I was making now and that she wanted to help me avoid those mistakes.

She told me I was angering the men in the group. (This wasn’t news to me: they’d already made that plenty clear in their reply emails.) She told me that I was “sounding” wrong. That I lacked political judgment. (This is true, then as it is now.) Discussions like these, she said, were delicate. They should be private. Whispered. Handled one-on-one—never as a group. Alliances should be formed and then a strategy implemented. Everything should take place behind closed doors. In smoke-filled rooms. That’s where power was exchanged.

The gist of what she was saying to me was Stop talking about this in the open! Stop talking.

Hmmm. What was so dangerous about talking? I wondered. While Julia continued, I puzzled over this question. I remember thinking that there was something deeper going on here. That there was a parallel conversation taking place, but I couldn’t quite hear it.

Julia went on, explaining things to me. Her arguments became more pointed. Pointed at me. She began to explain to me who I was. She told me I was ambitious. She told me I was aggressive. And she told me that she sensed a deep well of anger in me that was coming out in some pretty unattractive ways.

(She also said I was strident. Now I ask you: Have you ever heard that word used to describe a man? Ever? And since a dictionary definition of the word is “presenting a point of view, especially a controversial one, in an excessively and unpleasantly forceful way,” doesn’t the word have as much to do with the listener as with the speaker?)

So the parallel conversation, the one I had sensed but couldn’t quite hear, was Julia telling me, You have flaws that are shameful and un-female and ugly. And you need to shut up before everyone else sees how ugly you are.

Why is it so seductive to believe what other people say about us? Is it because we’re flattered that they’re thinking about us at all?

But even as I listened to what Julia was saying, I heard a humming in my head. I know I’m supposed to call this a “voice,” but it wasn’t, because the word “voice” implies words, and this humming was below the level of language. And still, without words, it was there: quiet, insistent, and filled with meaning. The humming floated questions in my brain, What’s wrong with being ambitious? Why aren’t women allowed to be aggressive? Is anger off limits?

It was Julia’s comment about the “deep well of anger” that tipped the scale for me. Even my own highly active self-critical voice knew that this wasn’t a match. (That self-critical voice shouted, That’s not what’s wrong with you. I’ll tell you what’s wrong with you!)

And if Julia was wrong about that, then wasn’t it just as likely that she was wrong about all of it? Or at least her spin on it: that there was shame and humiliation for women who were ambitious and aggressive and angry? And that the consequence—angry men—must be avoided at all costs.

Humming, humming, humming.

All my life, I’ve struggled to hold onto my sense of myself in the face of someone else telling me who I am. When I was younger, it was my sisters who held great sway over my identity. And later, it was teachers and boyfriends—and one particularly terrible therapist. And after that, as I made my way in the world of children’s publishing, it was editors and agents and librarians and readers. And here I was, old enough to know better, and yet I might have stumbled in the midst of this conversation with Julia—because she was older and spoke with that particular voice of authority and seemed so damn certain.

But I could still hear the humming in my head. The humming of friction, of electricity running through a wire. The sound a tuning fork makes when it’s struck, sending out one, clear note. It came from deep, deep within me and told me that what Julia was saying wasn’t true about me, and I didn’t have to accept it and internalize it as the truth of my own identity. I had a choice. I could listen to her and still make up my own mind about who I was and who I wanted to be. A smart, aggressive, ambitious, successful woman who sometimes gets angry but is confident enough and skilled enough and compassionate enough to express that anger in a productive, healthy, and respectful way. At least, that's the goal.

Humming. Humming. Humming.

I began to wonder if Julia heard a humming inside her head, or if that sound had been drowned out years ago by the myriad voices telling her who she could be and what she was allowed to want. It is so easy to internalize these voices and take them on as our own. I found myself thinking, as Julia spoke, Do you hear what you're saying— one woman telling another to sit down and be quiet? Can you hear the humming inside your head? Or has it grown too faint?

I think this was the first time in my life that I managed to keep my compass pointing north, despite the magnetic pull of millennia of female naming and shaming and silencing.

And that’s the point I most want to make, and I hope that it’s the piece of this experience that will help you in the future. If we keep straining to listen to that quiet humming inside of us, we get to be who we are. Without silence or shame.

I left that organization years ago, and I’ve since joined lots of groups of wonderfully supportive, smart, loyal, talented, funny, got-your-back women. Women of KidLit is one of them. So the message of this post isn’t you can’t trust your sisters. Or that you should never accept an honest piece of criticism offered with love and support. It’s just that it’s really important that you listen to the humming in your own head, and give it a place of honor when someone—anyone—is telling you you’re too much this or too much that for their pleasing. Because chances are you’re never going to end up pleasing them, and you’d probably hate yourself if you did.

Jacqueline Davies's Blog

- Jacqueline Davies's profile

- 266 followers