Bodhipaksa's Blog, page 8

September 9, 2014

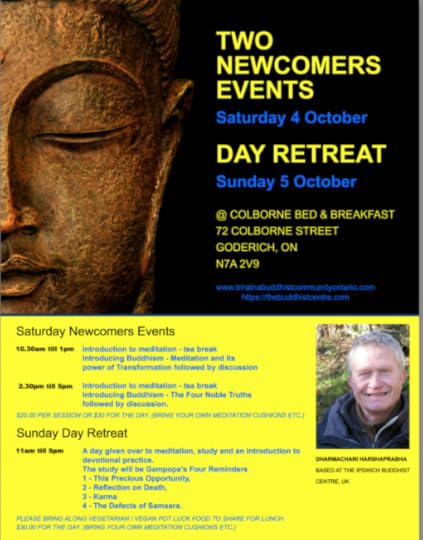

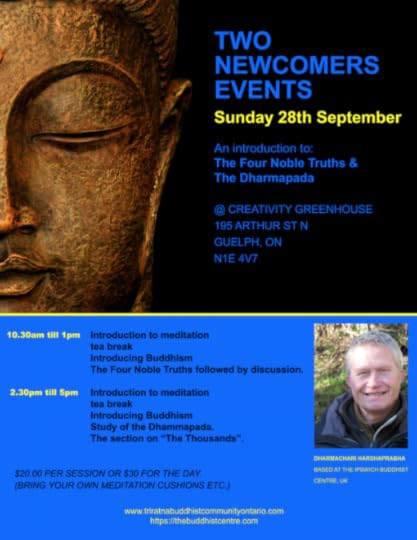

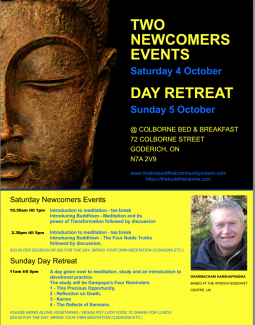

Meditation in Guelph and Goderich, Ontario

Harshaprabha is making the second of his twice yearly visits to Ontario. The events, in Guelph and Goderich, are suitable for those with an understanding of, or even just a curiosity about, Buddhism.

Harshaprabha is making the second of his twice yearly visits to Ontario. The events, in Guelph and Goderich, are suitable for those with an understanding of, or even just a curiosity about, Buddhism.

Harshaprabha’s dream is to see the Triratna Buddhist Community established in the Province.

To realize this dream he makes bi-annual trips and leads events for newcomers and others. These give people an opportunity to experience being with other like-minded people in meditation and in discussing Buddhism as interpreted by the founder Urgyen Sangharakshita and his disciples.

In between his visits Harshaprabha keeps up his connections via e-mail, Skype, telephone, and Facebook. His dream is to be doing this work full time.

Details of the Ontario events are in the attached e-flyers.

Harshaprabha was ordained in 1982 in Tuscany, Italy, was a founding member of The Buddhist Hospice Trust. He ran a Buddhist Right Livelihood business called Octagon Architects + Designers for 21 years and was instrumental in setting up the Colchester Buddhist Centre, Essex, UK. He now co-leads a newcomers evening every week, facilitates a weekly Men’s Group, gives talks, and supports retreats at the Ipswich Buddhist Centre, Suffolk, UK.

Related posts:

The Power of Self-Compassion: A Workshop in Toronto, Oct 19, 2013

Meditation is not enough

The marriage of meditation and neuroscience

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

September 2, 2014

The Buddha’s radical path of jh?na

Jh?na — a progressive series of meditative states of absorption — is a controversial topic in Buddhism. This should be rather amazing given that the Buddhist scriptures emphasize jh?na so strongly. In the Eightfold Path, Right Concentration is consistently defined as the four jh?nas. The Buddha said things like “There is no jh?na for him who lacks insight, and no insight for him who lacks jh?na.” The jh?nas are enumerated over and over again in the P?li scriptures. They’re also implicit in teachings like the Seven Bojjha?gas, the 12 positive nid?nas, and the ?n?p?nasati Sutta, which mention various of the jh?na factors.

Jh?na — a progressive series of meditative states of absorption — is a controversial topic in Buddhism. This should be rather amazing given that the Buddhist scriptures emphasize jh?na so strongly. In the Eightfold Path, Right Concentration is consistently defined as the four jh?nas. The Buddha said things like “There is no jh?na for him who lacks insight, and no insight for him who lacks jh?na.” The jh?nas are enumerated over and over again in the P?li scriptures. They’re also implicit in teachings like the Seven Bojjha?gas, the 12 positive nid?nas, and the ?n?p?nasati Sutta, which mention various of the jh?na factors.

Despite the scriptural importance of jh?na, some teachers, like Thich Nhat Hanh, have argued that jh?na was something that the Buddha rejected, and that it was smuggled into the suttas after the Buddha’s death:

The Four Form Jh?nas and the Four Formless Jh?nas are states of meditational concentration which the Buddha practiced with teachers such as ?l?ra K?l?ma and Uddaka R?maputta, and he rejected them as not leading to liberation from suffering. These states of concentration probably found their way back into the sutras around two hundred years after the Buddha passed into mah?parinirv?na. The results of these concentrations are to hide reality from the practitioner, so we can assume that they shouldn’t be considered Right Concentration. (Transformation and Healing: Sutra on the Four Establishments of Mindfulness, page 29)

The specifics of this objection are interesting because they contain some fundamental misunderstandings, and I’d like to explore in this article the topic of the relationship of the so-called “formless jh?nas” (I’ll explain that qualification in due course) to the “jh?nas of form,” and the role of these “formless jh?nas” in the Buddha’s biography — specifically his training under ?l?ra and Uddaka, and the Buddha’s later realization that jh?na was the “path to Awakening.”

First, there’s the assumption that ?l?ra and Uddaka taught the Buddha the four jh?nas. Now, the Buddha never mentions that he learned or practiced the jh?nas with his two teachers. He says that he learned to attain the “sphere of nothingness” (?kiñcañña-?yatana — I prefer “no-thingness” as a translation) from ?l?ra Kalama, and the “sphere of neither perception nor non-perception” (nevasaññ?n?sañña-?yatana) from Uddaka Ramaputta. (Uddaka had apparently not experienced this himself, and was merely passing on Rama’s teaching).

“But,” many Buddhists will object, “if ?l?ra and Uddaka taught the Buddha how to attain these spheres, then they must also have taught the Buddha how to attain jh?na, since these spheres are the seventh and eighth jh?nas — part of the four ‘formless jh?nas’ that follow on from the four ‘jh?nas of form.’” (The first two “formless jh?nas” are the sphere of infinite space and the sphere of infinite consciousness.) But this is the very error that I am keen to address.

The suttas never refer to any “formless jh?nas.” What are nowadays called the “formless jh?nas” are in fact never referred to as jh?nas in the scriptures, but are referred to consistently as “?yatanas” or “spheres.” It’s only in the later commentarial tradition that the two lists are presented as one continuous list of “eight jh?nas.” They should really be known as “formless spheres.”

Now this is important, because the four formless spheres are in fact not jh?nas at all. Many meditators have discovered that it’s possible to experience these formless spheres without having first gone through the jh?nas. There has been much confusion for some who have had such experiences, because the assumption that the ?yatanas can’t be experienced without first having traversed the jh?nas is so prevalent. I am in fact one of the many people who has experienced that confusion.

There are suttas in which there is reference to experiencing the ?yatanas without first going through the jh?nas. Most people would tend to assume that in these suttas the jh?nas are assumed, without being mentioned explicitly, but there’s no need to make that assumption, and experience shows it to be false. Certain forms of meditation predispose to direct experience of the ?yatanas. Suttas discussing the six element practice and the divine abidings show those meditations leading directly to the formless spheres. I don’t disagree that it’s possible to reach the ?yatanas via the jh?nas, but there are other ways.

The fact that it’s possible to reach the formless spheres without going through the jh?nas helps us make sense of an important episode in the Buddha’s life. In the Maha-Saccaka Sutta the Buddha described how he intuited, prior to his enlightenment, that jha?na was “the way to Awakening”:

I thought: ‘I recall once, when my father the Sakyan was working, and I was sitting in the cool shade of a rose-apple tree, then — quite secluded from sensuality, secluded from unskillful mental qualities — I entered and remained in the first jha?na, with rapture and joy born from seclusion, accompanied by initial thought and sustained thought. Could that be the way to Awakening?’ Then following on that memory came the realization: ‘That is the way to Awakening.’

That’s a strong statement. The Buddha had not just a hunch, or an idea, but an actual realization that jha?na is the way to Awakening.

Now, many people have struggled to make sense of this episode. The Buddha had previously attained the seventh and eighth “jh?nas” (in reality the third and fourth ?yatanas) under Uddaka and ?l?ra’s instructions, so how could a memory of first jh?na be so significant in pointing the way to Awakening? All sorts of explanations for this apparent contradiction have been made, but the simplest is one that may be least obvious: that the Buddha had not in fact previously explored the jh?nas with ?l?ra and Uddaka, and that he had explored the ?yatanas through means other than by going through the jh?nas. Confusion arises because we’re so conditioned by the commentarial belief that to enter the ?yatanas we must first go through the jh?nas, that we assume that the Buddha must have had experience of the jh?nas.

I see the jh?nas and the ?yatanas arising in different ways. Jh?na involves paying more and more attention to less and less. In going deeper into jh?na we progressively “tune out” first our thinking, then the pleasurable sensations that arise in the body as we relax, and finally joy. This leaves only one-pointed attention on an object of attention, accompanied by a sense of great peace. Jh?na is a form of progressive simplification — more and more attention being focused on a smaller and smaller subset of our experience.

The ?yatanas involve the opposite approach. Rather than “homing in” our attention so that it’s focused on less and less of our experience, we allow our attention to be all-inclusive, excluding nothing from our awareness. Speaking of my own practice, when I enter the ?yatanas, what I do is pay full attention to all of my experience: that which arises from within (thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations) and that which arises from outside (light, sound, space, etc.). I then maintain an awareness of both of these fields of experience, finding a point of balance of inner and outer. AS that balance is maintained, the mind becomes very still. At a certain point, the boundary between “inside” and “outside” is lost, and there is simply a single field of awareness. This process is speeded up if I consciously focus on the supposed boundary between inside and outside. In meditation this boundary is perceived to be very fuzzy, and in fact, the closer you look at it the less it seems to exist. Later, other distinctions are lost as well, and there is a loss of the sense that the body has a three dimensional orientation in space.

In the suttas, all of the entry points to the ?yatanas have one thing in common: equanimity. The jh?nas culminate in an experience of equanimity; having narrowed down our experience and brought the mind to a state of peace, we then broaden our experience once again and enter the formless spheres. (Or so I am told; I have never entered the formless spheres this way.) The fourth divine abiding is of course equanimity, which is also a springboard to an experience of the ?yatanas. And the sutta describing the six element practice says that it beings the mind to equanimity and thus into the ?yatanas. The formless spheres can be experienced from any meditation that brings about a state of tranquil equanimity.

The Buddha experienced the formless spheres to the furthest possible extent, but he didn’t manage to become enlightened by so doing. Instead, he intuited, jh?na was a more likely route to spiritual liberation. Why should this be? We can only speculate, but my sense is that the teachings of ?l?ra and Uddaka explained the ?yatanas in terms of unifying oneself with the wider universe. In the ?yatanas, certain discriminative faculties — those that produce a sense of spacial separateness — are progressively shut down. (These faculties are a function of the brain’s parietal lobes, which become less active in non-dual meditation.) This sense of religious union would fit with pre-Buddhist views of there being an atman (Self) that is part of a larger “Brahman” (a cosmic reality). ?l?ra and Uddaka may not have used those precise terms, but a sense of unity with the cosmos is a common religious trope, and it’s reasonable to assume that they saw that experience as the desired outcome of practice.

What does jh?na do? What is its function? It allows us to focus in exquisite detail on minute aspects of our experience. And that allows us to see that everything that constitutes the self — or what we take to be the self — is in fact an experience that is changing moment by moment. By repeating this minute examination of our experience, we come to the realization that there is no possibility of there being a separate self that needs to be unified with the cosmos.

The Buddha in fact was fond of saying:

I tell you, friend, that it is not possible by traveling to know or see or reach a far end of the cosmos where one does not take birth, age, die, pass away, or reappear. But at the same time, I tell you that there is no making an end of suffering and stress without reaching the end of the cosmos. Yet it is just within this fathom-long body, with its perception & intellect, that I declare that there is the cosmos, the origination of the cosmos, the cessation of the cosmos, and the path of practice leading to the cessation of the cosmos.

Although we would often like the Buddha to be like a modern scientist, in some important respects he wasn’t. He didn’t seem particularly interested in what we would think of “cosmic” questions, and in fact saw them as distractions from the spiritual life. After all, at the Buddha’s time, when it came to questions of whether the universe was finite or infinite, had a beginning or was eternal, etc., there was no possibility of doing more than speculating. These cosmic topics are all matters that the Buddha thought of as being useless subjects for discussion. Rather than indulging in speculation, he preferred to put his attention onto matters where he could have knowledge arising from direct observation. In that regard he did, in an important sense, take a scientific approach. And his work was akin to that of a scientist who finds that in order to understand the nature of stars, we must look at how subatomic particles behave. The way to understand our place in the cosmos, the Buddha was suggesting, is to examine ourselves. And this is what jh?na allows us to do. Jh?na supports insight.

In the Buddha’s view, samatha (the cultivation of the jh?nas) and vipassan? (the cultivation of insight) were not mutually exclusive or antagonistic activities, which is how they are sometimes seen today. In the Samaññaphala Sutta, for example, the Buddha describes the practitioner moving deeper into the jh?nas and then, “With his mind thus concentrated, purified, and bright, unblemished, free from defects, pliant, malleable, steady, and attained to imperturbability, he directs and inclines it to knowledge and vision.” Jh?na makes it easier for the mind to observe impermanence through minute examination of our experience, and thus makes it easier for insight to arise. Conversely, insight also makes it easier for jh?na to arise, and so he says elsewhere, “There’s no jha?na For one with no wisdom (pan?n?a), No wisdom for one with no jha?na).” Samatha and vipassan? are complementary and synergistic.

If you want to know your place in the universe, it may seem intuitively obvious that you need to reflect on (or speculate on) the universe. So it was a radical departure on the Buddha’s part to withdraw from speculation on the universe, and to turn his attention inwards. It was also a radical departure for him to turn away from the experience of the formless spheres, which bring about a temporary sense of unification of self and cosmos, but which do not entirely remove our self-clinging. It was a massive leap of intuitive wisdom for the Buddha to arrive at the conclusion, “Jha?na is the way to Awakening.”

But why, having failed to gain insight through the ?yatanas, should the Buddha have kept them as part of his teaching? Wouldn’t it make more sense to jettison the formless spheres and focus exclusively on the jh?nas? I see two possible reasons for him doing this.

First, the assumptions that ?l?ra and Uddaka made about the ?yatanas (that they were an experience of a permanent self uniting with the universe) may have been the main reason that the Buddha didn’t find them conducive to insight, assuming, as is likely, that he’d picked up on the same assumptions. Stripped of those assumptions, experience of the formless spheres, he may have reckoned, may be more spiritually useful.

Second, the experience of the ?yatanas, even if it doesn’t lead directly to insight, does a valuable job in changing our sense of self. Learning that our sense of self is malleable may not directly help us to lose our attachment to that self, but it does help us to loosen such attachments. There can be less grasping after something that is fluid and malleable rather than something that is solid. Experience of the ?yatanas helps us to appreciate that our sense of self is not fixed, but can be dramatically different than it normally is. In my own experience, the altered states of self-perception that I experienced in the formless spheres did seem to have a bearing on my later experience of non-self.

A parallel is to be found in that way that experience of psychedelic drugs has brought many people to Dharma practice. Having had the experience that their “normal” sense of reality is just one possible configuration of their experience can lead some to wonder what other modes of perception there might be. Psychedelics have even been used experimentally to help treat anxiety and depression — conditions that tend to involve a very fixed sense of self — sometimes bringing about long-term positive change very rapidly.

So, the Buddha had no formal experience of the jh?nas until shortly before his awakening. He had not been trained in the jh?nas by ?l?ra and Uddaka, although he did have extensive experience of the ?yatanas. The intuition that jh?na might be the way to Awakening was the beginning of a process whereby he began to explore his experience in minute detail, learning to observe its impermanence. And it was through this means that he became Awakened.

It’s time to lay aside the notion that the ?yatanas are jh?nas, and that they can only be experienced by traversing the jh?nas. It’s time also to lay aside the very non-traditional notion that the samatha (cultivating the jh?nas) and vipassan? (cultivating insight) are mutually antagonistic activities, and to recognize them as synergistic parts of one path.

And lastly, it’s time to recognize the radicalness of the Buddha’s decision to turn his attention away from meditations that lead to an apparent unity of the self with the cosmos, the radicalness of using jh?na to hone the mind into a powerful focused instrument, and even the radicalness of refusing to settle for the blissful and peaceful experiences that arise in jh?na, so that he could enter into a minute examination of the nature of his experience and find that there was, in a sense, no self there.

Rather than jh?na acting to “hide reality from the practitioner,” as Thich Nhat Hanh puts it, it is jh?na that allows us to lay reality bare, so that we may attain awakening.

Related posts:

Fake Buddha Quote: “You cannot travel the path until you have become the path itself.”

Lovingkindness as a path to awakening (Day 25)

Cultivate only the path to peace

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

August 29, 2014

Empathy versus compassion

On the Boston Review, Paul Bloom has a provocative article titled “Against Empathy.” It’s not advocating an uncompassionate approach to life, and in fact central to his thesis is that there is a distinction between empathy, which he says can limit and exhaust us, and compassion, which he points out is more sustainable.

On the Boston Review, Paul Bloom has a provocative article titled “Against Empathy.” It’s not advocating an uncompassionate approach to life, and in fact central to his thesis is that there is a distinction between empathy, which he says can limit and exhaust us, and compassion, which he points out is more sustainable.

There’s one particular section where there are several references to Buddhism and to Buddhist practitioners:

It is worth expanding on the difference between empathy and compassion, because some of empathy’s biggest fans are confused on this point and think that the only force that can motivate kindness is empathetic arousal. But this is mistaken. Imagine that the child of a close friend has drowned. A highly empathetic response would be to feel what your friend feels, to experience, as much as you can, the terrible sorrow and pain. In contrast, compassion involves concern and love for your friend, and the desire and motivation to help, but it need not involve mirroring your friend’s anguish.

Or consider long-distance charity. It is conceivable, I suppose, that someone who hears about the plight of starving children might actually go through the empathetic exercise of imagining what it is like to starve to death. But this empathetic distress surely isn’t necessary for charitable giving. A compassionate person might value others’ lives in the abstract, and, recognizing the misery caused by starvation, be motivated to act accordingly.

Summing up, compassionate helping is good for you and for others. But empathetic distress is destructive of the individual in the long run.

It might also be of little help to other people because experiencing others’ pain is exhausting and leads to burnout. This issue is explored in the Buddhist literature on morality. Consider the life of a bodhisattva, an enlightened person who vows not to pass into Nirvana, choosing instead to stay in the normal cycle of life and death to help the masses. How is a bodhisattva to live? In Consequences of Compassion (2009) Charles Goodman notes the distinction in Buddhists texts between “sentimental compassion,” which corresponds to empathy, and “great compassion,” which involves love for others without empathetic attachment or distress. Sentimental compassion is to be avoided, as it “exhausts the bodhisattva.” Goodman defends great compassion, which is more distanced and reserved and can be sustained indefinitely.

This distinction has some support in the collaborative work of Tania Singer, a psychologist and neuroscientist, and Matthieu Ricard, a Buddhist monk, meditation expert, and former scientist. In a series of studies using fMRI brain scanning, Ricard was asked to engage in various types of compassion meditation directed toward people who are suffering. To the surprise of the investigators, these meditative states did not activate parts of the brain that are normally activated by non-meditators when they think about others’ pain. Ricard described his meditative experience as “a warm positive state associated with a strong prosocial motivation.”

He was then asked to put himself in an empathetic state and was scanned while doing so. Now the appropriate circuits associated with empathetic distress were activated. “The empathic sharing,” Ricard said, “very quickly became intolerable to me and I felt emotionally exhausted, very similar to being burned out.”

One sees a similar contrast in ongoing experiments led by Singer and her colleagues in which people are either given empathy training, which focuses on the capacity to experience the suffering of others, or compassion training, in which subjects are trained to respond to suffering with feelings of warmth and care. According to Singer’s results, among test subjects who underwent empathy training, “negative affect was increased in response to both people in distress and even to people in everyday life situations. . . . these findings underline the belief that engaging in empathic resonance is a highly aversive experience and, as such, can be a risk factor for burnout.” Compassion training—which doesn’t involve empathetic arousal to the perceived distress of others—was more effective, leading to both increased positive emotions and increased altruism.

Related posts:

Self-hatred, self-compassion, and non-self

Brain can be trained in compassion, study shows

Joan Halifax: Compassion and the true meaning of empathy

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

August 27, 2014

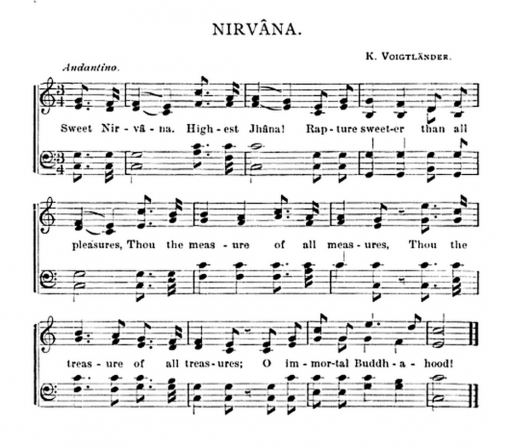

Sweet Nirv?na!

I found this sweet hymn in a book by Paul Carus, called Sacred Tunes for the Consecration of Life: Hymns of the Religion of Science. Carus (18 July 1852 – 11 February 1919) was an early German-American translator, compiler, and popularizer of Buddhist texts.

Carus seems to have been fond of hymns, since he published an entire book of settings of Buddhist texts. This is available online, courtesy of archive.org.

Unfortunately my sight-reading skills have atrophied through decades of disuse, and I’m only able to guess at what the tune is.

Here is the rest of the song.

Sweet Nirv?na,

Highest Jh?na!

Rupture sweeter than all pleasures,

Thou the measure of all measures,

O, immortal Buddhahood!

Sweet Nirv?na,

Highest Jh?na!

Balm that all our ailments curest.

Thou alone for aye endurest!

O, immortal Buddhahood!

Sweet Nirv?na,

Highest Jh?na!

State where thoughts are truest, purest;

Where our wisdom is maturest,

And our hearts in love securest,

O, immortal Buddhahood!

Sweet Nirv?na,

Highest Jh?na!

Of all jewels thou the rarest,

Him thou fill’st with radiance fairest,

O, immortal Buddhahood!

Sweet Nirv?na,

Highest Jh?na!

Overcome all selfish clinging,

Let love’s harmonies be ringing,

While all join the chorus, singing:

O, immortal Buddhahood!

Related posts:

Revenge isn’t sweet

The marriage of meditation and neuroscience

The book that changed my life

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

August 5, 2014

Stunning!

A New Report Argues Inequality Is Causing Slower Growth. Here’s Why It Matters.

A new report says inequality is causing slower growth. It is not a novel conclusion. The surprise is the source: Standard & Poor’s.

Related posts:

Inequality and the farm bill

Santa is a black man

A modicum of sanity breaks out

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

August 3, 2014

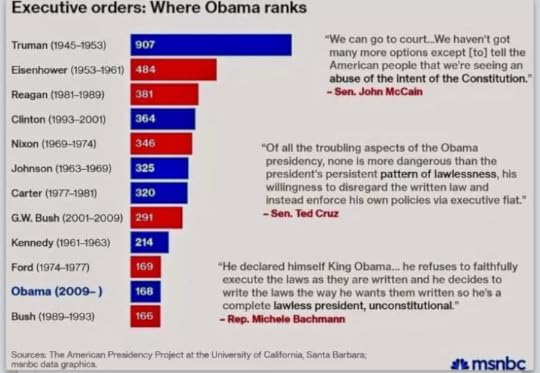

Willful blindness?

Can so many really politicians be so ignorant of facts, or is it a willful blindness? In other words, is this ignorance or deception? Neither is a good trait to see in the country's government.?

This post has been reshared 14 times on Google+

View this post on Google+

Related posts:

Funny!

This is brilliant in so many ways…

Word

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

August 1, 2014

Word

Word

Reshared post from +Victoria Robin

This post has been reshared 9 times on Google+

View this post on Google+

Related posts:

Funny!

This is brilliant in so many ways…

Free Market Jesus speaks…

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

July 30, 2014

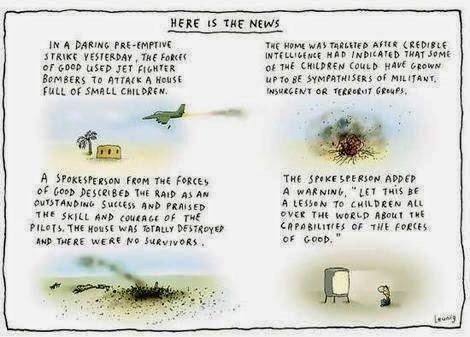

Here is the news…?

Here is the news…?

This post has been reshared 2 times on Google+

View this post on Google+

Related posts:

Funny!

This is brilliant in so many ways…

Word

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

July 24, 2014

Urgent appeal for donations

Wildmind needs to raise at least $3000 before the end of July, and preferably a bit more since $3000 would just allow us to scrape by.

Wildmind needs to raise at least $3000 before the end of July, and preferably a bit more since $3000 would just allow us to scrape by.

Right now we have a financial crisis. The end of the month is coming and we don’t have enough in the bank to pay our staff. That’s rather worrying for all of us on a personal level, for obvious reasons.

(This has been an unusual month for Wildmind, financially. I’ll put a note with more details below.)

Anything you can contribute would be most welcome. You’d not just be helping those of us who work at Wildmind (Mark, Amy, and myself), but also the “greater us,” which is the tens, and even hundreds of thousands of people Wildmind benefits.

It would be wonderful if you could donate $1000, or $100, or even just $10.

If you want to use a credit card, you can go to this page, enter the amount you want to donate, and then begin checking out by clicking on “add to cart.”

If you have a Paypal account, you can click on the button below and enter your chosen donation:

Checks can be mailed to: Wildmind, 55 Main St. Suite 315, Newmarket NH 03857, USA.

If you’ve been participating in our 60 Days to Jhana (which may extend beyond 60 days, since I’ve slowed the pace of posting — a development that many people have welcomed) I hope you’re enjoying and benefiting from the event. If not, I hope to see you when we repeat this event next year.

Wildmind’s activities are largely supported by donations. We’re very grateful to everyone who contributes to what we do. Without the support of people like you, we wouldn’t be able to offer free events like our Year of Going Deeper, or maintain our free online meditation guides, or keep bringing you a constant stream of advice, news, and inspiration to nourish your meditation practice. So please do help support Wildmind!

With metta,

Bodhipaksa

PS. I said I’d say a bit more about our financial situation this month and why it’s unusual. First, last year our tax accountant messed up our tax filing, and we just paid $3000 to a new accountant to fix the previous accountant’s errors. Second, we had a major computer malfunction and had to pay for specialist help. And lastly, the supplier of one of our meditation timers put a fraudulent charge for over $1300 on our debit card; the best case scenario is that it’ll take a few weeks to get this refunded, and the worse case is that we’ll just have to accept the loss.

Related posts:

Progress, pitfalls, and more progress!

Paying the Dharma forward

Five benefits of helping to free Bodhi

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

July 19, 2014

How to raise compassionate kids

Are you raising nice kids? A Harvard psychologist gives 5 ways to raise them to be kind

Think your kids are being raised to be kind? Think again. A Harvard researcher and psychologist has 5 ways to train your child to be kind and empathetic.

Related posts:

Wordless wednesday: kids in Ethiopia

The compassionate art of taking breaks

A Buddhist blog by kids, for kids

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.