Bodhipaksa's Blog, page 2

May 8, 2015

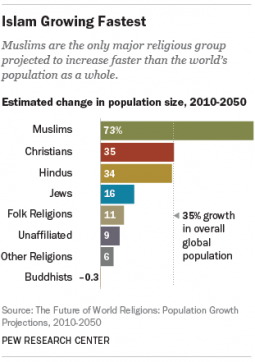

Buddhism poised to shrink globally

A new report by the Pew Research Center suggests that of all the world’s major religions, Buddhism is the only one destined to lose ground between now and 2050.

A new report by the Pew Research Center suggests that of all the world’s major religions, Buddhism is the only one destined to lose ground between now and 2050.

The total number of adherents to Buddhism will remain virtually unchanged, with a slight decline from approximately 187 to 186 thousand people. But since the global population will have risen, the percentage of the world population that practices Buddhism will have declined sharply from 7.1% to 5.2%.

In the meantime, the percentage of the world practicing Christianity will be roughly static, while Islam will go from being embraced by 23.2% to 29.7% of the world.

This strikes me as ironic, since at the moment Buddhist practices are being tested in laboratories around the world, and being shown to have beneficial effects ranging from slowing the aging of the brain to reducing pain. I would have hoped that this evidence would have encouraged more people to explore Buddhist practice, but I’d guess that this spread of Buddhist practice is taking place mostly in the west, and that most people who take up meditation are doing so in a secular way, through Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction classes, etc. And while the secular, unaffiliated, population is set to increase by 100 million, they’ll be shrinking from 16% to 13% of the global population. It looks like Buddhism’s going to have a hard time sneaking in through the back door!

Will this all happen as foretold? I’ve no idea. I’m imagine that the Pew researchers know what they’re talking about, but projections don’t always translate into reality, and can even bring about changes. Who knows, seeing these projections some Buddhists may increase their outreach efforts and bring new converts into the religion.

Related posts:

Tricycle on Buddhism and politics

Does Hawaii represent the future of religion in the US?

10 things science (and Buddhism) says will make you happy

YARPP powered by AdBistroPowered by

April 23, 2015

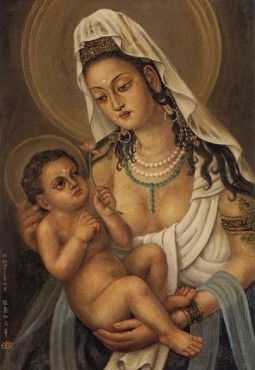

You are the child of all beings

A well-known Buddhist teaching explains that all (or at least most) beings have, at one time or another in the inconceivable past, been close family members:

A well-known Buddhist teaching explains that all (or at least most) beings have, at one time or another in the inconceivable past, been close family members:

From an inconstruable beginning comes transmigration [sa?s?ra]. A beginning point is not evident, though beings hindered by ignorance and fettered by craving are transmigrating and wandering on [literally “sa?s?ra-ing”]. A being who has not been your mother at one time in the past is not easy to find… A being who has not been your father… your brother… your sister… your son… your daughter at one time in the past is not easy to find. [M?ta sutta]

A millennium or so later this was elaborated by Buddhaghosa into a reflective practice, so that we contemplate in detail how any person we’re feeling resentful of has, at some point in the past, as our mother, carried us in her womb, given birth to us, suckled us, and taken care of us. And as our father, this being has previously worked tirelessly and took great risks to provide for us, and even went to war to protect us.

The point of this practice is to eliminate ill will. Recognizing the debt we owe to others, we can think, “It is unbecoming for me to harbor hate for him [or her!] in my mind.”

Being of a scientific bent, and not putting much stock in reflections that hinge upon a belief in rebirth, I find myself approaching this advice in a different way. Let’s take rebirth as a metaphor: change is happening all the time, and so we’re each moment we die and are reborn.

This is what I think the Buddha had in mind, rather than literal rebirth, when he said in the Dhatu-Vibhanga Sutta:

Furthermore, a sage at peace is not born, does not age, does not die, is unagitated, and is free from longing. He has nothing whereby he would be born. Not being born, will he age? Not aging, will he die? Not dying, will he be agitated? Not being agitated, for what will he long?

If you like my articles and want to support the work I do, please click here to check out my books, guided meditation CDs, and MP3s. Or you can make a donation.If there’s only a constant process of death and rebirth, moment by moment, then there’s no “thing” that can be born, age, or die. Thus there’s nothing to mourn or fear, or to long for.

If you like my articles and want to support the work I do, please click here to check out my books, guided meditation CDs, and MP3s. Or you can make a donation.If there’s only a constant process of death and rebirth, moment by moment, then there’s no “thing” that can be born, age, or die. Thus there’s nothing to mourn or fear, or to long for.

If we look closely at our own moments of death and rebirth, we see that ultimately each one of them takes place not with us as an isolated unit, but as an inextricable part of a greater whole. Each momentary contact with the world is part of this process of death and rebirth.

Each perception is the birth of a new experience, and thus of a new “us.” Each time we see someone, hear someone, touch someone, or even think of someone, a new experience arises and we change; in a sense, we die and are reborn with every contact we have with another being.

Right now, as you read these words, my thoughts are echoing in your mind, evoking new experiences. Each word gives birth to a new you that didn’t exist a moment before.

And since the constellation of experiences that is me arises in dependence upon many other beings, your reading this article right now connects you to everyone who has ever been in my life, everyone who has been in those people’s lives, and ultimately all beings who are or have existed.

And since, in our immensely complex world, the unfolding, never-ending death-and-rebirth of each being is ultimately connected with the never-ending death-and-rebirth of each other being, all beings are our mothers and fathers.

Related posts:

“May all beings dwell in peace”: A guided meditation (Day 91)

All beings are from the very beginning Buddhas

“As a parent raises a child with deep love, care for water and rice as though they were your own children.” Dogen

YARPP powered by AdBistroPowered by

April 22, 2015

Facing the demon of self-doubt

Someone wrote to me the other day, asking for advice:

Someone wrote to me the other day, asking for advice:

I just started regularly meditating about a month ago. I’m scared to continue now though. I had a sudden feeling of self resentment and I felt it so deeply. I remembered the bad choices I have made in my life and felt so unworthy of love and compassion. I felt unworthy of the meditation itself. I felt like I was the most selfish person in the world. I can’t even begin to describe how painful it was.

What she’d described is what we call the “hindrance of doubt.” There are five of these hindrances, which are mental patterns that stop us from being at ease with ourselves. They are (1) craving, (2) ill will, (3) anxiety, (4) lethargy, and (5) doubt, which is the sneakiest of them all.

Doubt tells us stories that sap our confidence. This woman’s thoughts of unworthiness and of being “the most selfish person in the world” are doubt’s modus operandi. Sometimes the doubts are about our practice, but more commonly they’re about ourselves.

Doubt is the hardest of the hindrances to recognize, because the stories we’re telling ourselves “hit below the belt” emotionally and leave us feeling vulnerable and exposed. We totally believe the stories we’re telling ourselves, and have difficulty questioning their validity.

It’s very important to learn to recognize the patterns through which doubt expresses itself, and to remind yourself that this is just doubt—that it’s not reality you’re describing to yourself. It’s just a story.

When you do that, you’re less inclined to believe what you’ve been telling yourself. Having a thought like “I am unworthy of love” isn’t actually much of a problem if you don’t believe it, and if you recognize that this is just some frightened part of yourself trying to “protect” you from positive change.

And I do think that the function of doubt is to “protect us.” It may be a fear-based response to some difficulty. By telling ourselves we’re not capable of meeting this challenge, we take away the possibility of failing. It may also arise from a fear of positive change, however. Habits we have that are going to be eliminated act like sub-personalities and try to prevent change from happening. My guess is that this is what was going on with this woman: after a month of meditation, parts of her were fearful of change.

Don’t be afraid of doubt. Recognize that it’s just a story, and don’t take it seriously.

There are huge benefits to doing this. Often when we’ve recognized doubt and chosen not to believe it, there’s an immediate upwelling of energy and confidence in ourselves and our practice. On the other side of doubt lies faith.

Related posts:

The demon in the dark

Cultivating self-compassion (Day 29)

Separating feelings and thoughts

YARPP powered by AdBistroPowered by

April 20, 2015

Meditation in Ontario

I just wanted to flag up that in late May and June my friend Harshaprabha of the Triratna Buddhist Order will be offering the opportunity to meet with like-minded people in Goderich, Guelph and Sudbury, Ontario.

I just wanted to flag up that in late May and June my friend Harshaprabha of the Triratna Buddhist Order will be offering the opportunity to meet with like-minded people in Goderich, Guelph and Sudbury, Ontario.

He has planned a diverse set of events, ones which he believes will meet the expectations of those living in those places.

This is the first of his 2015 visits and one he is particularly looking forward to; not just meeting old and potentially new friends but the first time he has put on events in Sudbury.

Harshaprabha lives in the UK but has family ties to Ontario. He’s visited the province many times over the years in order to promote the practice of Buddhism.

I am sure you will receive a warm welcome by him and enjoy being introduced to meditation, practicing it and then hear about a particular Buddhist topic.

The events are in Goderich (29 and 30 May), Guelph (31 May), and Sudbury (6 and 7 June). These links will take you to PDF fliers for the relevant venues.

Related posts:

Meditation in Guelph and Goderich, Ontario

Join us for our second Year of Going Deeper

Any meditation you can walk away from is a good meditation

YARPP powered by AdBistroPowered by

April 17, 2015

“25 Mostly Fake Buddha Quotes That May or May Not Change Your Life.”

A blog post listing 25 Buddha quotes—most of which are fake—has now been “liked” over half a million times on Facebook. Sheesh.

So I’ve written a blog post debunking the list, with a link to an article on the origins of each quote, usually also with references to actual quotes from the Buddhist scriptures. The article’s called “25 Mostly Fake Buddha Quotes That May or May Not Change Your Life.”

So far it’s been liked nine times on Facebook. Only another 600,000 “likes” to go and we can leave the article of fake quotes standing in the dust :)

Head on over to FakeBuddhaQuotes.com, and remember to click the Facebook button at the foot of the article!

Related posts:

Fake Buddha Quote: “If we could see the miracle of a single flower clearly, our whole life would change.”

Fake Buddha Quote: “When words are both true and kind, they can change our world.”

More Fake Buddha Quotes, or fake-ish, at least

YARPP powered by AdBistroPowered by

April 2, 2015

Self-compassion: lovingkindness squared

Self-compassion is the most radically transformative practice that I’ve stumbled upon in more than 30 years of exploring Buddhism. It’s helped me to cope with many difficulties I’ve faced, ranging from the mundane challenge of a child’s tantrum, to financial problems and even serious illness. It’s helped me to become kinder and more compassionate not just to myself but also to others. In fact I don’t know of any other practice that’s changed me so much. I’d describe self-compassion as “lovingkindness squared.”

Self-compassion is the most radically transformative practice that I’ve stumbled upon in more than 30 years of exploring Buddhism. It’s helped me to cope with many difficulties I’ve faced, ranging from the mundane challenge of a child’s tantrum, to financial problems and even serious illness. It’s helped me to become kinder and more compassionate not just to myself but also to others. In fact I don’t know of any other practice that’s changed me so much. I’d describe self-compassion as “lovingkindness squared.”

Self-compassion is simply treating yourself kindly, responding to your own pain with compassion in the same way you’d respond to the pain of someone you care about. “Self-compassion” is a bit of a misnomer; we give compassion not to ourselves as a whole, but to any part of us that’s suffering.

I’d like to outline five steps that are involved in cultivating self-compassion.

1. Drop the Story

The mind generates stories around our suffering. These may be stories in which we blame others, or tell ourselves that the discomfort we’re experiencing is unbearable or shouldn’t be happening. They may be stories of revenge, or stories that we are bad, or worthless, or are doomed to suffer. They may be stories about ways we can numb or escape the pain.

These stories themselves cause us further pain, and so as we notice them arising it’s wise to disentangle ourselves from them, just letting the words echo away into the mind.

Our stories are what the Buddha called, in a famous analogy, “the second arrow.” He pointed out that we’re all subject to discomfort and pain, whether it’s having our feelings hurt or having a toothache or experiencing loss. This is the “first arrow,” which arrives unexpectedly. This kind of suffering suffering is inevitable. But our response to being hit by this arrow is often, the Buddha said, to indulge in the kinds of thoughts I described above, which he described as “sorrow, grief, and lamentation.” It’s these responses—our second arrows—that cause most of our suffering. Each thought like, “This is terrible!” or, “Why is this happening to me!” is a self-inflicted stab with the second arrow.

It can take a lot of practice to become mindful enough to stop these stories from arising, or even to catch them in the early stages. For a long time it may be that the first time we notice that something is up is when we’re in the middle of a reaction, having already created a full-blown inner (or outer) drama. So the first thing we do is to recognize that through our stories we’re creating unnecessary suffering for ourselves, so that we can drop the story line and become mindfully aware of the first arrow.

2. Recognize That Pain is Present

In order to practice self-compassion we have to notice that we’re in pain. But this may not be easy, because we have unhelpful habits such as taking our own suffering for granted, or denying our pain—perhaps seeing it as a sign of weakness—or just failing to notice it because pain is so common in our lives. We also may be so quick to jump to emotional reactions and stories—attempts to protect ourselves against suffering—that we don’t really acknowledge the suffering.

But whenever we’re frustrated, or angry, or lonely, or anxious, or longing, or when our feelings are hurt, we’re suffering. Every sub-optimal state we experience is a form of suffering. It’s important that we recognize this pain, otherwise we can’t practice self-compassion.

Let’s take an example: a friend saying something that hurts our feelings. First we hear the words and interpret them as an insult, even though they may not have been intended that way. Then the brain flags up the comment as something potentially harmful to you by creating a sensation of pain in the body, probably in the solar plexus. This is the mind’s way of saying “Here’s a threat! Pay attention to it!”

Another common place for painful feelings to arise is around the heart. The heart and gut are areas of the body rich in nerve clusters, and the brain generates sensations in those places as a way of catching our attention and provoking us to action. Sometimes feelings of hurt can be so strong it’s like we’ve been punched in the gut. No wonder we react strongly.

One fascinating thing that’s recently been found is that feelings such as the ache of isolation become less intense when we take pain-killers such as Tylenol. What we think of as “emotional” pain is just a special form of physical pain, induced in the body by the mind.

The kinds of internal sensations I’ve been discussing are what Buddhism calls vedanas. Vedana is a technical term referring to the pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral sensations that are generated to accompany every perception we have.

The mental processing that leads to the arising of these feelings takes place in parts of the brain that aren’t accessible to conscious awareness. We can’t, for example, choose not to be hurt. We do, however, have some ability to chose how to respond to the perception of hurt.

3. Turn Toward the Pain

We can choose to respond to pain with acceptance. In practicing self-compassion, it’s important that we learn to accept our pain—that we allow it just to be there, without having aversion toward it. To respond skillfully to suffering we have to be prepared to turn toward it.

Taking a mindful approach to our pain means recognizing that it’s OK to experience suffering, and even to take an interest in it. It’s especially helpful to notice, as precisely as we can, where the pain is located in the body, and to observe its size and texture, and how it changes from moment to moment.

Accepting our pain in this way means that we’re no longer stabbing ourselves with the second arrow—no longer creating stories that intensify and prolong our suffering. Instead, we’re simply mindful of the first arrow. If we find that the stories start to creep in again, and that thoughts are arising, we keep letting go of them, just as we do when we’re meditating.

The Buddha pointed out that another way we turn away from pain is to pursue pleasure. Often we’ll do that through numbing ourselves with food, or alcohol, or busyness, or television. We may not actually get much pleasure from these activities—it’s the pursuit of pleasure that’s the distraction. As long as we’re leaning into the future, seeking pleasure, we’re no longer being with the pain of the present moment. So, just as we need to drop our stories, we need also to drop our avoidance. The most effective way to deal with discomfort is to turn toward it.

It can be hard to turn toward pain in this way. In evolutionary terms, pain evolved as a protective mechanism. The whole point of pain is to alert us to the fact that something is wrong, so that we can escape the painful situation. The way I think about turning toward our pain is this: imagine that a friend has turned up on your doorstep in a state of distress. What do you do? Well, hopefully you won’t respond with aversion, trying to get rid of the discomfort by slamming the door and running into the house. Ideally, you’d invite your friend in, sit them down, and take a kindly and compassionate interest in what’s going on with them.

Sometimes it can be useful to say, “It’s OK to feel this. Let me feel this,” just to remind ourselves to stay with our discomfort.

Being mindful of our feelings in this way creates what we call “the gap.” This is a pause—I think of it as a sacred pause—in which we can choose not to let our normal reactions kick in. Instead, we create an opportunity for compassion to arise.

4. Give Your Pain Compassionate Attention

Having accepted a painful feeling mindfully, the next stage is to give it your compassionate attention. This means treating your pain with the same gentleness and kindness with which you would treat a friend who is suffering. Sometimes I think of my pain as a small, wounded part of me that is in need of love and comfort—like a small animal.

To relate to your pain compassionately, wish it well. Talk to it. Soothe it. You can use the same phrases you would use in lovingkindness or compassion meditation, saying things like, “May you be well; may you be happy; may you be free from suffering.” But sometimes those words can seem hackneyed, so I’m more likely to say something like, “I know you’re in pain, but I’m here for you,” or “I love you, and I want you to be happy.” With intense suffering I’ll sometimes resort to the deep trust expressed by St. Julian of Norwich: “All will be well, and all will be well, and all manner of thing will be well.”

5. Respond Appropriately

As you become more skilled at recognizing and accepting your pain, and with responding to it compassionately, you’ll find that it’s easier to respond in an appropriate way to situations that give rise to pain in the first place.

There are no rules for how to respond. It depends on the situation, on your skills in communication, etc. But when you’re mindful of your pain and cultivate compassion toward it, you’ll discover you have more creativity at your disposal than you’d imagined possible. You’ll probably find that having responded with empathy and compassion toward yourself, you’ll quite spontaneously behave the same way toward others.

These five steps can be worked through very quickly. I’ve run through them while driving at 65 miles per hour on a highway: Someone cuts me off, I start up with an angry storyline “Idiot! How dare you!” I realize that this is causing me to suffer, drop the story, notice the pain that (it’s usually fear, located in the solar plexus), accept it, and then send it some compassionate thoughts (“May you be well; may you be free from suffering”). And my having done that, the anger vanishes and I find that I’m not only compassionate toward myself, but to the other driver as well. This may take just a few seconds.

I’ve found it useful as well when I’m stressed. For example while I’m cooking and being bombarded with demands from my children. I’ll notice a knot of tension building up in my gut, give it a moment’s compassionate intention, and find that the desire to snap at the kids has gone. It works for sadness, depression, and anxiety. Self-compassion is the Swiss Army Knife of spiritual techniques.

One myth I’d like to dispel is that if you’re reacting to a situation, it’s too late to find the gap. The pain of the first arrow doesn’t disappear just because you’ve started reacting to it! Every time you let go of your stories and drop your awareness down into the body so that you can notice your initial feelings of hurt, fear, etc., you are bringing the gap into being, and with it the freedom to respond creatively.

It’s only through treating my pain compassionately that I’ve realized the extent to which the way we treat ourselves is related to the way we treat others. Once we are able to respond to our own pain with compassion, we find that compassion for others flows freely. It’s lovingkindness squared.

Related posts:

Self-hatred, self-compassion, and non-self

Compassion as an antidote for our own suffering (Day 45)

The Urban Retreat, Day 8: Developing compassion

YARPP powered by AdBistroPowered by

March 31, 2015

“Not being able to govern events, I govern myself.” Montaigne

I’ve been depressed a few times in my life, but only once has it ever got so bad that I felt I had to seek medication. My doctor prescribed me something—I no longer remember what—and after taking just one tablet my depression instantly lifted. This was no miracle drug; these medicines take days or even weeks to have an effect. In fact the medication had nothing to do with my recovery, and the reason I felt better so quickly was, I think, because I admitted I was helpless.

I’ve been depressed a few times in my life, but only once has it ever got so bad that I felt I had to seek medication. My doctor prescribed me something—I no longer remember what—and after taking just one tablet my depression instantly lifted. This was no miracle drug; these medicines take days or even weeks to have an effect. In fact the medication had nothing to do with my recovery, and the reason I felt better so quickly was, I think, because I admitted I was helpless.

Michel de Montaigne, the famous 16th French essayist, said that although he was not able to govern external events, he was able … Read more »

Related posts:

Some French music that mostly isn’t by French artists

Power of prayer flunks an unusual test

Twitter Updates for 2008-09-11

YARPP powered by AdBistroPowered by

March 30, 2015

“Not being able to govern events, I govern myself.” Montaigne

I’ve been depressed a few times in my life, but only once has it ever got so bad that I felt I had to seek medication. My doctor prescribed me something—I no longer remember what—and after taking just one tablet my depression instantly lifted. This was no miracle drug; these medicines take days or even weeks to have an effect. In fact the medication had nothing to do with my recovery, and the reason I felt better so quickly was, I think, because I admitted I was helpless.

I’ve been depressed a few times in my life, but only once has it ever got so bad that I felt I had to seek medication. My doctor prescribed me something—I no longer remember what—and after taking just one tablet my depression instantly lifted. This was no miracle drug; these medicines take days or even weeks to have an effect. In fact the medication had nothing to do with my recovery, and the reason I felt better so quickly was, I think, because I admitted I was helpless.

Michel de Montaigne, the famous 16th French essayist, said that although he was not able to govern external events, he was able to govern himself. This beautiful observation embodies a truth that is old, but which we often have to be reminded of anew.

We can’t control what happens to us but we can, if not control, then at least influence how we respond to it. We often think of happiness in terms of providing ourselves with an endless stream of pleasant experiences, with no unpleasantness to mar the perfection of our paradise. And yet we can never achieve such a goal. The conditions that exist in the world are far too complex for us to be able to manage. We may want to have only pleasant experiences, but the world isn’t going to cooperate with us. We’re always going to have a mixture of pleasant and unpleasant experiences

From the Buddhist point of view, the truest happiness comes from not allowing ourselves to be swayed either by the pleasant or unpleasant. This is what’s called “equanimity,” or upekkha. When pleasant experiences arise, we enjoy them, yes, but we don’t try to get more out of them than they’re able to give us. We don’t try to hold onto them, and recognize that they’re impermanent phenomena. When unpleasant experiences arise, we bear with them, knowing that they’re going to pass, not causing ourselves further pain by resisting the discomfort with thoughts like, “This shouldn’t be happening. This is terrible!” We allow all experiences to come and go.

This doesn’t mean that we become inactive and passive, simply putting up with things that can be changed: if the room is cold we can turn up the heat; if there’s injustice in the world we can campaign to right it. But there are always going to be things we can’t control.

My depression was one such thing. I didn’t know at the time what had cause the depression, and I’m not 100 percent sure I do now, but I suspect that what was keeping it in motion was that I thought I should be able to fix it. And the more I was unable to fix my depression, the more depressed I stayed. What might have been no more than a passing mood ended up being with me for weeks. In seeking held and telling my doctor that I had a problem I couldn’t control, I freed myself from thinking that I had to control or should be able to control the depression. Without the internal pressure that came from needing to be in control, my depression had nothing to feed on, and simply vanished.

In this case, “governing myself” didn’t mean “being in control of everything.” No government is ever in total control of its nation. A government is an organ of adaptation. Instead, governing myself meant taking the most appropriate action open to me, which in this case was relinquishing my belief that I should be able to control my experience. Sometimes the best use of our ability to control is surrendering the illusion that we have control.

Related posts:

“Not being able to govern events, I govern myself.” Montaigne

Turning problems into spiritual opportunities

Six ways of reflecting on impermanence

YARPP powered by AdBistroPowered by

March 28, 2015

Pat Robertson on Buddhism as a “disease”

Christian Broadcasting Network host Pat Robertson suggested to viewers on Monday that Buddhism was like a “disease” and that a Christian could get “infected” if their coworkers practiced it.

“I work in an environment where all of my coworkers are Buddhists,” a viewer named Tina explained in an email. “They talk about Buddhism all day long and try to preach to me. It didn’t matter much to be before, but since I recommitted myself to Jesus a year ago, it has started to bother me a lot.”

Robertson replied by noting that “healthy” people might not contract a “mild contagion.”

“But if you put yourself in the middle of a … Read more »

Related posts:

Tricycle on Buddhism and politics

Buddhism’s dirty secret

Jesus meditating

YARPP powered by AdBistroPowered by

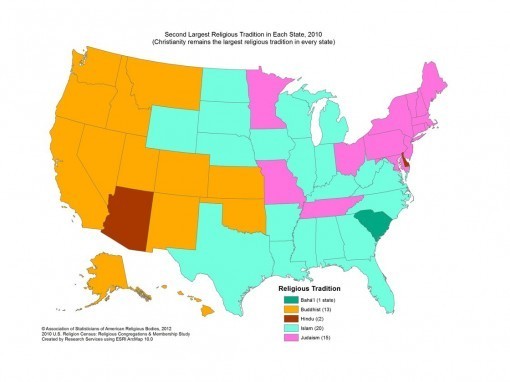

Does Hawaii represent the future of religion in the US?

This fascinating map from the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies (click to enlarge) shows the second largest religious tradition in each of the states of the US. Buddhism is in second place in 13 states. Hawaii, with a large population of Japanese descent, perhaps isn’t a surprise. California is perhaps incapable of giving surprises. Alaska? I did not see that coming.

Of course it probably doesn’t take much for a religion to be in second place in the US. Christianity, as you’d expect, is the majority religion in every state. Another resource shows that the percentage of the population identifies as Buddhist in each of these states is … Read more »

Related posts:

Religion versus wealth

Einstein on Religion

School Board to Pay in Jesus Prayer Suit

YARPP powered by AdBistroPowered by