Bodhipaksa's Blog, page 4

January 14, 2015

Could meditating as a cure for insomnia backfire?

When I find myself awake in the middle of the night, perhaps after a trip to the bathroom or a weird dream, I often practice some kind of meditation to quiet my over-active mind. I’ll usually pay attention to my breathing, or do a body scan, and most times this will help me calm down and nod off.

When I find myself awake in the middle of the night, perhaps after a trip to the bathroom or a weird dream, I often practice some kind of meditation to quiet my over-active mind. I’ll usually pay attention to my breathing, or do a body scan, and most times this will help me calm down and nod off.

But could meditating in the middle of the night create its own problems? Someone asked me whether this practice could either lead to us developing the habit of falling asleep during meditation, or keep us awake because mindfulness is so associated with alert attention that we can’t fall asleep.

I don’t think the first is much of a danger; we’re not likely to end up training ourselves to fall asleep in meditation. What happens when we can’t sleep is that intrusive mental activity inhibits the normal physiological mechanism that causes sleep. By being more mindful of the body, we let go of that mental activity, stop inhibiting sleep, and nod off. But in normal meditation (unless you’re already very tired) the physiological mechanism leading to sleep isn’t active, and so you’re not likely to drop off.

Not only can the second problem happen, but it’s something I’ve experienced many times. Meditation isn’t just about relaxation, but involves the arising of counter-balancing “active” qualities like curiosity, interest, and physical arousal. While calmness and relaxation are more likely to predominate when we meditate in order to get to sleep, sometimes alertness will prevail, so that we find ourselves in a “perked up” state that isn’t conducive to nodding off. But if that happens, I think it’s just a signal that we need to take another approach.

I find that visualizing soothing but boring imagery works rather well. For example I’ll imagine rain pattering on the leaves of a tree, on a particularly gray and dismal day. This counteracts the thought patterns and the emotional arousal that prevent sleep from happening, but it makes for a dull experience, and so I don’t get excited about it. I sometimes suspect that I fall asleep just so that I can dream about something more interesting!? This isn’t classic meditation, obviously, but it’s a good way of applying the principles of meditation in order to bring about a desired result — in this case a good night’s sleep.

If you like our articles and want to support the work we do, please click here to check out our ebooks, guided meditation CDs, and MP3s.One way that middle-of-the-night meditation has backfired on me has been when I’ve woken from an anxious dream, and taken my attention to the feeling of anxiety. Normally what I’d do is to give the anxiety some compassionate attention, and to sooth myself by being aware of the breathing down in the belly. But recently I’ve found that if I try being mindful in the middle of the night, my experience of the body changes radically. The body’s solidity and sense of form dissolves away, and I’m left with an experience of a translucent cloud of sensations hovering in space. The first couple of times this happened there was a “What the heck?” reaction that led to me remaining awake, seemingly for hours, just observing this phenomenon. But now that I’m used to this happening, I quite quickly get back to sleep again. Perhaps a general lesson is that if using meditation to overcome insomnia doesn’t work at first, keep going. It may be something that you need to persist with.

If you like our articles and want to support the work we do, please click here to check out our ebooks, guided meditation CDs, and MP3s.One way that middle-of-the-night meditation has backfired on me has been when I’ve woken from an anxious dream, and taken my attention to the feeling of anxiety. Normally what I’d do is to give the anxiety some compassionate attention, and to sooth myself by being aware of the breathing down in the belly. But recently I’ve found that if I try being mindful in the middle of the night, my experience of the body changes radically. The body’s solidity and sense of form dissolves away, and I’m left with an experience of a translucent cloud of sensations hovering in space. The first couple of times this happened there was a “What the heck?” reaction that led to me remaining awake, seemingly for hours, just observing this phenomenon. But now that I’m used to this happening, I quite quickly get back to sleep again. Perhaps a general lesson is that if using meditation to overcome insomnia doesn’t work at first, keep going. It may be something that you need to persist with.

Related posts:

Keeping a level head while meditating

Meditating with IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome)

When you’re afraid of meditating

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

January 12, 2015

Creating a natural anti-depressant brain?

I haven’t read the book I’m about to introduce, but I’m familiar with the author and the advance information about it makes it sound interesting.

I haven’t read the book I’m about to introduce, but I’m familiar with the author and the advance information about it makes it sound interesting.

Uncovering Happiness: Overcoming Depression with Mindfulness and Self-Compassion is written by psychologist and bestselling author Elisha Goldstein, PhD. It shows us the science of natural anti-depressants and gives us the practices to unlock them, building new neural structures to uncover genuine happiness.

Hardcover: Barnes & Noble, Book Passage, Indie Bound, Powell’s, Simon & Schuster.

eBook: iBooks, Nook, Simon & Schuster, Google Play Store.

We now know that we can use our minds to change our brains, but Dr. Goldstein’s Uncovering Happiness reveals techniques that help us break our negative habit loops and release these five natural anti-depressants in the brain: mindfulness, self-compassion, purpose, play and developing confidence—ultimately creating a natural anti-depressant brain.

The book integrates the findings of hundreds of academic studies and dozens of interviews with mindfulness teachers, psychologists, neuroscientists and researchers. There are also stories of many people who have used these teachings to find their personal pathway to healing.

This book contains a message of hope: Having experienced bouts of anxiety, depression or being just down in the dumps doesn’t mean you have to suffer from it in the future. As Goldstein says, “Science and thousands of people’s experience are showing that these seven simple elements can help us take back control of our minds, our moods and our lives.”

The book comes out on January 27th. You can pre-order a copy and receive the free bonus of Dr. Goldstein’s “Uncovering Happiness Training” – A 90 Minute presentation that take you step-by-step through the elements of Uncovering Happiness, by visiting the author’s site.

Related posts:

Brain can be trained in compassion, study shows

Hardwiring Happiness: The New Brain Science of Contentment, Calm, and Confidence

Creating a culture of generosity

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

January 9, 2015

How to stop beating yourself up (and practice self-compassion instead)

Here’s a video I recorded for En*Theos Academy last year.

It’s on the crucial topic of how to develop self-compassion, and I offer a step-by-step guide to the basic skills of doing this.

En*Theos have kindly made the video available for general use.

I hope it’s helpful!

Related posts:

How to stop beating yourself up

Another great self-compassion resource

How to stop beating yourself up

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

December 27, 2014

Finding the Sacred Balance: One more push!

As 2014 draws to a close, our Finding the Sacred Balance fundraiser is now over 90% funded! We now have just over $1,000 left to raise in order to break even by the end of the year. We’d like to thank the more than 200 people who have already donated!

As 2014 draws to a close, our Finding the Sacred Balance fundraiser is now over 90% funded! We now have just over $1,000 left to raise in order to break even by the end of the year. We’d like to thank the more than 200 people who have already donated!

Please consider financially supporting us in our efforts to promote meditation, by giving whatever you can afford.

If you want to use a credit card, you can click here, enter the amount you want to donate, and then click on “add to cart.”

If you have a Paypal account, you can click here and enter your chosen donation.

And lastly, checks can be mailed to: Wildmind, 55 Main St. Suite 315, Newmarket NH 03857, USA.

Here’s how we’re doing so far

Related posts:

Finding the sacred balance

Urgent appeal for donations

An urgent appeal – please give today!

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

December 23, 2014

“All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.” — St. Julian of Norwich

This was revealed to St. Julian by Jesus in a vision, and recorded by her in her Revelations of Divine Love: “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.” These words have been of great comfort to me in times of stress and anxiety.

This was revealed to St. Julian by Jesus in a vision, and recorded by her in her Revelations of Divine Love: “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.” These words have been of great comfort to me in times of stress and anxiety.

Meditation practice can reduce, but doesn’t erase, anxiety. In fact meditating makes us more sensitive to what’s going on within us, both emotionally and physically. When we meditate we feel more. Meditating can also lead to us being more present with those feelings, so rather than than avoid or bury them we experience them full-on. In these ways, meditation can cause our anxiety to be stronger!

If this sounds like bad news, it should be balanced by the fact that meditation also gives us the ability to stand back from our anxiety and to befriend it, so that it becomes less threatening and is less likely to lead to worry.

(What’s the difference between anxiety and worry? I see anxiety as being an initial unpleasant feeling in the body, produced by parts of the brain that are not accessible to conscious awareness. Worry, on the other hand, is where the mind responds to this initial unpleasant feeling with a succession of “what if” thoughts, that again and again turn toward what we’re anxious about, and in doing so intensify our anxiety.)

Sometimes I can be with my anxiety mindfully. I can accept it. I can recognize that I don’t have to turn it into worry. And to prevent my mind getting caught up in worrying thoughts, I can keep myself grounded in my experience of the body. I can especially be aware of sensations low down in the body, like the movements of the belly or sensations of contact with the ground, my seat, or whatever else is physically supporting me. I can relax the physical tension that accompanies anxiety and worry by really letting go on the out-breath. I can offer my anxiety (or the anxious part of my mind) reassurance and kindness. I can say to it, “May you be well; may you be happy; may you be at peace.” The point here is not to make the anxiety go away, but to be a compassionate presence for it while it’s in existence.

But there are times when I turn to those words of St. Julian (or of Jesus, depending on your perspective).

One thing they remind me of is that all things pass. I’ve had intense worries in the past. I remember one time being in utter despair because of financial problems (although really those fears were more to do with concern that I wouldn’t get support from others). I even had some suicidal thoughts, although I knew I had no intention of following through on them. But where are those particular financial problems now? The debt I was struggling with at that time has just gone. (I may have new debts, but they are new, and not a continuation of the same problem I had before.) Where is the isolation that I feared before? That’s gone too. Where is the anxiety I experienced in the past? It’s no more than a memory, and not even a very vivid one. I can recall feeling despair, but in recollecting it I feel compassion for my old self rather than falling into despondent once again. The past is gone. Memories are just thoughts. They’re like dreams or mirages.

So even though there are things going on in my life right now that prompt anxiety to arise — health concerns, housing concerns, financial concerns — I know that from the perspective of my future self they too are going to have a dream-like or mirage-like quality. And so I can remind myself, “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.”

Julian had been concerned with the question of sin: why did God allow it, since if he hadn’t then all would have been well from the beginning. The reason is to do with sin, pain, and faith. Sin, she tells us, is another kind of mirage: “I saw not sin: for I believe it hath no manner of substance nor no part of being.” She did believe that the experience of pain was real, however, even if it was impermanent. “Nor could sin be known but by the pain it is cause of. And thus pain, it is something, as to my sight, for a time.”

An album of guided meditations for stress reduction is available for download from our online store.The value of pain, in Julian’s view, was that it could cause faith to arise. It causes us to reach out to God. Had we not had sin, and therefore not had pain, then we would, in some sense, have been god-like. And so God allowed sin.

An album of guided meditations for stress reduction is available for download from our online store.The value of pain, in Julian’s view, was that it could cause faith to arise. It causes us to reach out to God. Had we not had sin, and therefore not had pain, then we would, in some sense, have been god-like. And so God allowed sin.

Buddhism doesn’t use the word “sin,” but it does say that our pain is caused by spiritual ignorance. And one key manifestation of this ignorance is that we see things that “hath no manner of substance” as being real and substantial. And as in Julian’s view, it is pain (dukkha) that impels us to seek happiness and peace — that drives us toward awakening.

Julian’s view of “sin” was quite remarkable, and it would be misleading not to point out her belief that because God allowed sin to exist, he therefore shows no blame to any who shall be saved. We don’t, after all, choose to have spiritual ignorance, or to be born with sin.

To Julian, “all shall be well” because we’ll find God in heaven. To me, “all shall be well” not just because pain will pass, but because we’ll awaken to the nature of reality, and will see that pain itself (such as the pain of anxiety) “hath no manner of substance.”

Anxiety isn’t just dream-like or mirage-like when we look back on it from the future. It has those illusory qualities right now, whether we see that or not. Right now, when we look closely at our anxiety, we’ll see that it’s not really there. It’s just patterns of sensation in space. When we can see our experience in that way, then “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.”

Related posts:

Day 15 of Wildmind’s 100 Day Meditation Challenge

Your anxiety deserves your love

There’s nothing to hold onto; there’s nothing to do any holding on. (day 89)

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

December 22, 2014

“But right now … right now”

You know the standard advice: when you notice during meditation that the mind has been caught up in thinking rather than with paying attention to your present-moment experience, just let go of the thoughts, without judgement, and just come back to the object of the meditation practice. And do that over and over.

You know the standard advice: when you notice during meditation that the mind has been caught up in thinking rather than with paying attention to your present-moment experience, just let go of the thoughts, without judgement, and just come back to the object of the meditation practice. And do that over and over.

But sometimes the thoughts are very persistent, especially if there’s something that’s preoccupying you emotionally. If you’ve been involved in an unresolved conflict, or have unfinished business, or if you’re looking forward to some big event, then it’s natural that your mind is going to turn to that over and over.

Over the years I’ve found a “trick” that helps me to disengage, gently but firmly, from obsessive thinking. It’s a simple phrase that I drop into the mind: “But right now…”

When I realize that I’ve been caught up in thinking — yet again — in whatever train of thought has been preoccupying me, I’ll drop that phrase into my mind as I return to the meditation practice. Often it takes the form “But right now … right now …”

If you like our articles and want to support the work we do, please click here to check out our books, guided meditation CDs, and MP3s.This phrase does three things:

If you like our articles and want to support the work we do, please click here to check out our books, guided meditation CDs, and MP3s.This phrase does three things:

It affirms the value of the present moment: “But right now.” I’m redirecting my mind away from thoughts of the past or future, and back to whatever is arising for me right now.

It also affirms whatever it is that I’m obsessing about. In saying “but right now” I’m implicitly acknowledging that there is a time and place for thinking about the issue my mind keeps turning toward, but that that time is not now. I’m not saying that it’s “bad” to think about these things, just that this isn’t the right time.

It creates a sense of openness and curiosity. “But right now … what?” What is arising right now? What have I not been paying attention to while I was obsessing about the past or future?

A friend told me that she has a similar phrase: “What is?” She redirects her mind to what’s implicit in the question, which is “What is my present-moment experience?” “What is arising for me right now?” “What is going on in my experience?”

So there you have two phrases you can play with. Or perhaps you’ll come up with your own way of gently redirecting your mind away from persistent thoughts.

Related posts:

“Being in the moment”

Day 17 of Wildmind’s 100 Day Meditation Challenge

Relax, rest, reveal

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

December 20, 2014

The holographic dinosaur; or, How fear is an illusion

You’re walking down a busy shopping street, and you hear panicked screaming. You turn to see what the fuss is, and behind a fleeing crowd you see something impossible: a velociraptor. It’s snarling and roaring, turning its head from side to side as it follows the hysterical populace, almost as if it’s herding them. Perhaps it is.

You panic. Before you even realize you’re doing it, you’re sprinting to the doorway of the nearest shop. Fortunately velociraptors, as is well known, are not good with door handles. As long as you get through that doorway you’ll be all right.

Safe behind the protection of the shop window, you watch people on the street fleeing the fearsome creature.

But then you notice a curious thing: the velociraptor doesn’t actually seem to be harming anyone. And anyway, a velociraptor? They’ve been extinct for millions of years! Surely it’s some kind of trick? A joke. A stunt. Still feeling terrified, but convinced there’s more to this than meets the eye, you step back into the street and approach the animal. It certainly looks very real. It’s not someone in a suit. There are no dangling power cords. It doesn’t seem to be mechanical.

The velociraptor stares at you. Your heart pounds. You take a wary step forward. It snarls. You reach toward it, almost close enough to touch its feathery skin. At the very point when your fingers should encounter solid flesh, you feel — nothing. Precisely nothing. Your hand passes right into the velociraptor. Fascinated, you realize that it must be some kind of holographic projection. There was never any danger. In a way there was never anything to fear.

We’ll come back to that a little later…

Over the years I’ve taken many different approaches to feelings, or vedanas, as they’re called in Buddhism. I’ve written about these a lot, but for the sake of a quick recap, vedanas are internal, self-generated sensations — pleasant or unpleasant (or also, to be complete, neutral) that we have in response to things we’ve perceived or thought about. They often manifest in the solar plexus or around the heart. They result from the activation of nerve endings. They’re also involuntary — they’re not under conscious control. In my view they include things like frustration, ease, anxiety, joy, disgust, and pleasant anticipation.

At first I didn’t acknowledge vedanas, but would simply react to them. If I saw someone acting in a way I didn’t like, for example being greedy, I might feel the vedana of disgust, and then immediately react with anger, accompanied with critical thoughts. (The anger and the thoughts are cetanas, or volitions. They are under conscious control, at least potentially.)

Later I learned to identify and pay more attention to them, so that a “gap” would appear in which I could act more creatively — not reacting with anger or craving, for example, but instead with patience or kindness. Not that I do this all the time, but I do at those times when I’m most mindful. When we’re mindful of our feelings and create this gap, more helpful volitional responses have a chance to arise.

Later still I recognized that these feelings were often forms of suffering, and so I’d use them as a basis for self-compassion, sending them thoughts of lovingkindness, just as I would to a person who was in pain. This was the most radical practice I’d ever done. It literally changed my life, and freed me from a lot of suffering. Practicing self-compassion also made it much easier for me to practice compassion toward others.

More recently I realized there was another way to look at these feelings, which is where our holographic dinosaur comes in.

In the last few months I’ve realized that feelings are an illusion. When something like anxiety arises (and believe me, I’ve had ample opportunity to be mindful of anxiety in the past couple of years) I turn toward it — as I’ve done in the past. And I regard it with compassion rather than fear (or with not much fear). But now I really look at it. And what do I find? I see a constellation of sensations, hanging in space. There’s nothing substantial. There’s nothing solid. And there’s nothing to be afraid of. If anything, the experience of anxiety, closely examined, is a source of beauty, delight, and wonder.

An album of guided meditations for stress reduction is available for download from our online store.You’ve probably noticed the connection with the holographic velociraptor. It appears to be solid, and it appears to be scary. But there’s nothing there. When we touch the hologram, or attempt to, there’s a sense of joy, wonder, fascination. That’s what examining anxiety is like for me now.

An album of guided meditations for stress reduction is available for download from our online store.You’ve probably noticed the connection with the holographic velociraptor. It appears to be solid, and it appears to be scary. But there’s nothing there. When we touch the hologram, or attempt to, there’s a sense of joy, wonder, fascination. That’s what examining anxiety is like for me now.

I’m still caught out by anxiety and fear. Even if you know that at some point a velociraptor is going to appear from nowhere and charge at you, and even if you know that this creature is a harmless hologram, it’s still freaking scary when it does appear. You still jump out of your skin.

So when I wake at two AM, with the realization that I may be homeless and bankrupt early next year, and my heart’s pounding and my head’s racing, it all feels very real — as when we would experience panic when a velociraptor lunges at us from a dark alley, even though we know on some level that the animal isn’t real. But then, after that momentary and visceral panic has arisen, more reflective parts of the brain kick in, I turn toward the anxiety, and it’s revealed once more to be an illusion.

So I’d encourage you to turn toward your fears, and so examine them closely. What sensations are actually present? How are they changing, moment by moment? Keep doing this, and you’ll discover that the experience of anxiety is like a holographic projection.

I’m not saying that if you do this you’ll find that your anxiety is instantly revealed to be illusory. Perhaps your relationship with vedanas will have to evolve in the same way mine did. Perhaps it’ll take years. But as with many hard-won fruits of practice, I look at what I see now and think that this realization might have come more quickly had someone pointed it out to me earlier. (Maybe they did, and I didn’t take it on board.) And so I offer this in case it saves you some time, and speeds up the evolution of your practice. Maybe it makes no sense to you at the moment. But perhaps one day it’ll fall into place, and you’ll realize your fears to be illusions.

PS. I know that if I don’t share this video, someone will tell me I should!

Related posts:

An antidote to fear (Day 71)

The illusion of separateness, part one

Separating feelings and thoughts

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

December 16, 2014

The spiritual power of a smile

Studies have found that smiling makes people happier. Normally of course we think of things working the other way around: being happy puts a smile on our face. But the reverse is true as well. Feelings of happiness are triggered even when we don’t realize we’re smiling—for example when we’re clenching a pencil with the teeth, which causes the face to use the same muscles that are used when we smile. So the emotional impact of smiling is obviously not just the power of association, and it seems that it’s the activation of our “smiling muscles” that triggers the happiness response. But maybe it doesn’t matter why it works, as long as it does.

Studies have found that smiling makes people happier. Normally of course we think of things working the other way around: being happy puts a smile on our face. But the reverse is true as well. Feelings of happiness are triggered even when we don’t realize we’re smiling—for example when we’re clenching a pencil with the teeth, which causes the face to use the same muscles that are used when we smile. So the emotional impact of smiling is obviously not just the power of association, and it seems that it’s the activation of our “smiling muscles” that triggers the happiness response. But maybe it doesn’t matter why it works, as long as it does.

So as you meditate, smile, and help joy to arise. You don’t have to have a grin on your face. A gentle, almost imperceptible smile can have a transformative effect on how you feel. Smiling is a short-cut to unleashing your repressed joy.

One of the things that smiling does is to give us a sense of reassurance. When we smile, we send ourselves a signal saying “It’s OK. We got this. We can handle this.” When we smile, even in the face of difficulties, we remind ourselves that there’s a grown-up present. There’s a part of us that can function as parent, as mentor, as wise friend. We become our own spiritual guide.

Radical Self-Acceptance is available on our online store.Smiling shouldn’t however become a way of avoiding our experience. We don’t smile in attempt to drive away or replace difficult experiences but in order to be a friendly presence for them. Smiling, and the confidence it can bring, should make it easier for us to be with our experience, and less likely to turn from it.

Radical Self-Acceptance is available on our online store.Smiling shouldn’t however become a way of avoiding our experience. We don’t smile in attempt to drive away or replace difficult experiences but in order to be a friendly presence for them. Smiling, and the confidence it can bring, should make it easier for us to be with our experience, and less likely to turn from it.

A simple smile can help us to feel more playful. Playfulness—letting our effort be light, allowing our heart to be open, not taking things personally, and appreciating the positive—allows joy to arise. On the other hand, taking things too seriously is a sure-fire way to kill joy. When we try to force or control our experience—trying to do everything “right”—our experience becomes cold, tight, and joyless. Smiling helps us to lighten up.

When we smile, we’re more confident, and we can let go of our fear-driven need to police and control our experience. We’re less likely to judge, and can be more accepting. So we might, for example, notice that many thoughts are passing through the mind, and yet find ourselves at ease. We might notice an old habit kicking in once again, and rather than blame ourselves for messing up, feel a sense of kindly benevolence.

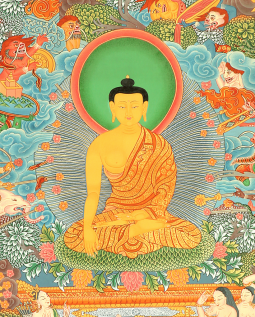

Guided Meditations for Self-Healing, by Jack KornfieldOne potent illustration of the power of a smile is the image of the Buddha being assaulted by the hordes of Mara, the personification of spiritual doubt and defeat. In this allegory, which has been depicted many times, Mara’s armies, which consist of hideous demons that symbolize craving, discontent, laziness, and fear, surround the Buddha. At the center of a tempest of demonic fury, the enlightened one sits, smiling serenely. A radiant aura extends around him, and when the weapons of his foes touch it, they fall harmlessly as flowers.

Guided Meditations for Self-Healing, by Jack KornfieldOne potent illustration of the power of a smile is the image of the Buddha being assaulted by the hordes of Mara, the personification of spiritual doubt and defeat. In this allegory, which has been depicted many times, Mara’s armies, which consist of hideous demons that symbolize craving, discontent, laziness, and fear, surround the Buddha. At the center of a tempest of demonic fury, the enlightened one sits, smiling serenely. A radiant aura extends around him, and when the weapons of his foes touch it, they fall harmlessly as flowers.

In a sense the Buddha’s aura is the radiance of his smile—the protective effect of his determined yet playful confidence. Every time we smile in meditation, we create the conditions for joy and peace to arise. Every time we smile in meditation, we connect ourselves to the Buddha’s own awakening.

Related posts:

Smile your way to kindness (Day 10)

Turning problems into spiritual opportunities

When spiritual practice gets in the way of spiritual progress

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

December 14, 2014

The bells!

Here’s a funny story for you.

Here’s a funny story for you.

One of the things we do to fund our activities at Wildmind is selling meditation supplies, which means that our office is also a mini-warehouse, stocked with incense, Buddha statues, meditation cushions — and mindfulness timers.

One day my work kept getting interrupted by a bell that would go off from time to time. The first couple of times it was no big deal. I thought that someone had perhaps jostled a wind chime, which will happen when stock’s being moved around. But as the sounds continued to happen, it became an annoying interruption.

The puzzling thing was that no one seemed to be doing anything that could be making this noise. I asked around to see if anyone, for example, had some app running that was creating a chiming noise, because I was trying to write an article and the interruption was really bothering me. It turned out that everyone else was also being disturbed and had been wondering what the noise was. In fact they’d all assumed it was the result of something I was doing!

Eventually we realized that one of the mindfulness timers we stock had somehow been switched on, and it seemed that the offending item was one that was boxed. The trouble was, which one? There was a pile of perhaps two dozen boxed meditation timers, and the bell would only ring once every few minutes. And by the time someone had dashed over to the place the timers were stored, the sound had already stopped.

It became my mission to find out which timer was ringing. This involved splitting them up in a process of eliminating non-offending timers. To cut a long story short, I finally tracked down and deactivated the timer that had been interrupting us, and we were all able to work undistractedly. The whole episode was very disruptive, not just because the bell had been interrupting our work, but because it had taken so much effort to switch the timer off.

The ironic thing, of course, is that the random bell was supposed to be an invitation to practice mindfulness — to stop what you’re doing and to spend a few moments tuning into the breath, to relax, and to let go! None of us had remembered to be mindful when we heard the bell ringing! In fact we’d all rather unmindfully been irritated by something that was supposed to me a mindfulness tool!

One trivial thing to learn from this is that something like a mindfulness bell only works when I have the expectation that it will. Unless, when I hear the bell, I have an assumption “this bell is intended to help me be mindful” it’s not going to function as a prompt for mindfulness.

But something I wonder is, why don’t I regard every annoyance as a mindfulness bell! Ironically, as I was writing this article I kept being interrupted by a co-worker who needed my advice on a number of questions. It dawned on me that I could use these interruptions to my routine to mindfully check in with myself. And the other week, when I found myself irritated by some software that didn’t function as expected, someone pointed out to me that I could be grateful to the company concerned because they were giving me an opportunity to become mindful of my impatience. I think that’s a brilliant idea, and something I need to work on.

Basically, I’d like to train myself to see the experience of annoyance as a mindfulness bell — letting it jolt me into a deeper awareness of myself. When I find I’m irritated by something, instead of going on a rant I can drop down to the level of feelings, recognize that the feeling of frustration I’m experiencing is a form of pain, and then send compassionate thoughts to that pain.

PS. Yes, I know that Quasimodo never said “The bells!” but I couldn’t resist the temptation to use a photograph of that character.

Related posts:

Hit the ground sitting! Day 7 of our 100 Day Meditation Challenge

ZenFriend: A new meditation timer for iPhone

Day 16 of Wildmind’s 100 Day Meditation Challenge

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

December 13, 2014

Perspectives on Satipatthana

An interview with Bhikkhu An?layo, author of Satipa??h?na: The Direct Path to Realization.Bhikkhu An?layo’s latest book, Perspectives on Satipa??h?na, uses a comparison of three different versions of the Satipatthana Sutta to reveal what the original core teachings are likely to have been.

An interview with Bhikkhu An?layo, author of Satipa??h?na: The Direct Path to Realization.Bhikkhu An?layo’s latest book, Perspectives on Satipa??h?na, uses a comparison of three different versions of the Satipatthana Sutta to reveal what the original core teachings are likely to have been.

Hannah Atkinson: Perspectives on Satipa??h?na is a companion volume to your earlier publication, Satipa??h?na: The Direct Path to Realization. How are the two books distinct and how do they work together?

Bhikkhu An?layo: My first book, Satipa??h?na: The Direct Path to Realization, came out of a PhD I did in Sri Lanka. It was the product of my academic study of the Satipa??h?na Sutta, the practical experience I had gained in meditation, and what I had read about the experience of other meditators and teachers – I tried to bring all that together to come to a better understanding of the text itself.

At that time I was working on the Pali sources of the Satipa??h?na Sutta because the Buddha’s teachings were transmitted orally from India to Sri Lanka and then eventually written down in Pali, which is fairly similar to the original language or languages that the Buddha would have spoken. However, the transmission of the Buddha’s teachings also went in other directions, and we have versions of the Satipa??h?na Sutta in Chinese and Tibetan. So after completing my PhD I learnt Chinese and Tibetan so that I could engage in a comparative study of parallel textual lineages, and this is the focus of my new book, Perspectives on Satipa??h?na.

Although this was, at the outset, mainly an academic enterprise, what I discovered really changed the focus of my practice. When I took out the exercises that were not common to all three versions of the Satipa??h?na Sutta, I was left with a vision of mindfulness meditation that was very different to anything I would have expected. Contemplation of the body, which is the first of the four satipa??h?nas, for example, is usually practised in the form of the mindfulness of breathing and being mindful of bodily postures, but these exercises are not found in all versions. What I found in all three versions were the exercises that most of us do not like to do: seeing the body as made out of anatomical parts and thus as something that it is not beautiful, as something that is made up of elements and thus does not belong to me, and the cemetery contemplations – looking at a corpse that is decaying.

So then I understood: body contemplation is not so much about using the body to be mindful. It is rather predominantly about using mindfulness to understand the nature of the body. As a result of these practices one will become more mindful of the body, but the main thrust is much more challenging. The focus is on insight – understanding the body in a completely different way from how it is normally perceived.

Normally we look at the body and see it as ‘me’, but these texts are asking us to take that apart and see that actually we are made up of earth, water, fire and wind, of hardness, fluidity and wetness, temperature and motion. They are asking us to directly confront our own mortality – to contemplate the most threatening thing for us: death.

Bhikkhu An?layo is a Buddhist monk (bhikkhu), scholar and meditation teacher. He was born in Germany in 1962, and ‘went forth’ in 1995 in Sri Lanka. He is best known for his comparative studies of early Buddhist texts as preserved by the various early Buddhist traditions.

Bhikkhu An?layo is a Buddhist monk (bhikkhu), scholar and meditation teacher. He was born in Germany in 1962, and ‘went forth’ in 1995 in Sri Lanka. He is best known for his comparative studies of early Buddhist texts as preserved by the various early Buddhist traditions.

I found a similar pattern when I looked at the last satipa??h?na, which is contemplation of dharmas. The practices that were common to all three versions were those that focused on overcoming the hindrances and cultivating the awakening factors. The emphasis is not so much on reflecting on the teachings, the Dharma, but really on putting them into practice, really going for awakening. As a result of this discovery I have developed a new approach to the practice of satipa??h?na which I have found to be very powerful, and this would never have happened if I had not done the academic groundwork first.

HA: Your books are a combined outcome of scholarly study and practical experience of meditating. Do you find that these two approaches are generally compatible with each other, or do they ever come into conflict?

BA: It is not easy to be a scholar and a practitioner at the same time. If you look throughout Buddhist history, it is more usual to find Buddhists who are either practitioners or scholars than Buddhists who are both. However, for a while I have been trying to achieve a balance between these two sides of me, and I have found a point of concurrence: the main task of meditation is to achieve ‘knowledge and vision of things as they really are’ and actually this is the main task of academics as well. We use a different methodology, but the aim of both is to understand things as they really happen. If I take that as my converging point, then I am able to be both a scholar and a meditating monk, and this has been a very fruitful combination for me.

Both of my books are aimed at people who, like me, are interested in academic study and meditation. They are academic books where the final aim is to help people develop their meditation practice. They are not books for beginners, and the second book builds on the first book, so one would need a basic familiarity with what I covered in Satipa??h?na: The Direct Path to Realization in order to fully engage with Perspectives on Satipa??h?na.

HA: Both of your books mention the idea of satipa??h?na as a form of balance, and the title of your new book suggests that there are many different perspectives on satipa??h?na that could be taken into account. Is the very essence of satipa??h?na practice a balance of perspectives or is there one particular perspective on satipa??h?na that has been most useful in the context of your practice?

BA: I think that balance is an absolutely central aspect of mindfulness practice. If you look at the Awakening Factors, the first one is mindfulness and the last one is usually translated as ‘equanimity’, but in my opinion it would be better to understand it as balance or equipoise. To be balanced means to be mindful and open to the present moment, to be free from desire and aversion, and this is what the Satipa??h?na Sutta continually comes back to.

I believe that balance is also an essential element of academic study. If, through my mindfulness practice, I am cultivating openness and reception then how can I say that one approach to a topic is totally right and another one is completely wrong? If I do that, I have to exclude all of the other approaches from my vision. Often, when we get into very strong opinions, we have tunnel vision – we see only one part of reality, one side of it, but that is not how things really are. So, in my academic work, if I find one approach that seems more reasonable to me, I keep it in the foreground, but I have to keep the other approaches in the background, I cannot just cut them out.

HA: Satipa??h?na: The Direct Path to Realization and Perspectives on Satipa??h?na both mention the importance of combining self-development with concern for others. Does satipa??h?na practice lead naturally to a person becoming more compassionate or is it necessary to engage in other practices to achieve this? Is satipa??h?na practice a solitary activity or is it important that it is undertaken in the context of a Sangha?

Buy Perspectives on Satipa??h?na for Kindle or iBooks.

Buy Perspectives on Satipa??h?na for Kindle or iBooks.BA: I think that compassion is a natural outcome of Satipa??h?na practice, but it is also good to encourage it in other ways as well. There is a simile from the Satipa??h?na Samyutta of two acrobats performing together on a pole – we need to establish our own balance in order to be in balance with other people and the outside world, but other people and the outside world are also the point at which we find out about our own balance. I can be practising alone, sitting in my room, feeling that I am so incredibly balanced and equanimous, but let me get out into the world and have some contact with people, come into some problems, and see how balanced I am then! Of course, time in seclusion and intensive meditation is essential, but there must always be a wider context to our practice.

Republished with permission from Windhorse Publications.

Related posts:

Gotcha!

Walking with love (Day 20)

Meditation is not enough

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.