Bodhipaksa's Blog, page 10

June 12, 2014

Self-compassion for writers (and other tortured souls)

I was talking to a Buddhist friend recently who’s a wonderful writer. She creates amazing blog posts that usually start off deeply personal but go on to teach important and universal lessons about life. I have a lot to learn from her about combining the personal and the instructional, and in many ways I regard her as the better writer. The thing is, she told me she hasn’t been able to write for two years now, because she’s a perfectionist.

I was talking to a Buddhist friend recently who’s a wonderful writer. She creates amazing blog posts that usually start off deeply personal but go on to teach important and universal lessons about life. I have a lot to learn from her about combining the personal and the instructional, and in many ways I regard her as the better writer. The thing is, she told me she hasn’t been able to write for two years now, because she’s a perfectionist.

And that’s the problem with perfectionism. Perfectionism makes us anything but perfect, because, for one thing, it makes it harder for us to create. Perfectionism is like teaching an animal to do a trick by beating it every time it doesn’t do exactly what you want. What would happen if you tried to do this? You’d end up with an animal that could only cower in terror. If the animal was sensible it would run away. If it was really sensible it would bite you first. And I think this is what happens with the creative parts of ourselves when we’re perfectionists. We end up training our creative energies not to create, and we produce what we call writers’ block, or (more generally) creators’ block. Our creative urges run and hide. They see the blank page, and don’t dare mar it because the critical part of us is sure to step in immediately and say “Not good enough. YOU IDIOT!”

But perfectionism is just another name for “low levels of self-compassion.” We need to recognize this because I think saying “I’m a perfectionist” is a way of humble-bragging: I won’t do anything unless it’s perfect, ergo, anything I do is perfect. I don’t create, but if I did it would be awesome. But while there are some high achievers who are perfectionists, their achievements come at a price. Perfectionism puts us on edge. It makes us rigid. When we’re driven by perfection we’re less likely to learn through play, experimentation, or trial and error. Self-compassion is where we treat ourselves kindly, even when we make mistakes. We recognize that we, just like everyone else, mess up. We recognize that mistakes are not only inevitable, but that they’re a helpful part of the learning process. To do anything meaningful we need to tolerate imperfection

I guess I’m an “imperfectionist.” A saying that I take as my pole star, my guide through life, is “If a thing’s worth doing, it’s worth doing badly.” So when I’m writing I just plunge in. I ignore my inner critic and allow myself to mar the page. The first effort may be ugly, repetitive, shallow, confused, or whatever. I don’t care. At least I have something to work with. Only after that initial creation do I go back and make improvements. That’s when the inner critic comes in handy. Your inner critic is an invaluable asset if you give it the right job to do — and that job is to tell you what’s not best about your work after you’ve written the first draft. Its job is not to prevent you from getting started. So I review and rewrite my work over and over, and each time I smooth the clunks out of my writing my inner critic has less and less to say. In the end it just shuts up because it’s done its job, and there’s nothing but good feelings when I read the text.

If you like my articles and want to support the work I do, please click here to check out my books, guided meditation CDs, and MP3s. Or you can make a donation.Beating yourself up just doesn’t work very well as a motivational strategy, and it has wider consequences for your wellbeing as well. Constantly being on edge in case we slip up, and then criticizing ourselves when we inevitably do, is a tough way to live. People who score low for self-compassion are much more prone to being stressed or depressed.

If you like my articles and want to support the work I do, please click here to check out my books, guided meditation CDs, and MP3s. Or you can make a donation.Beating yourself up just doesn’t work very well as a motivational strategy, and it has wider consequences for your wellbeing as well. Constantly being on edge in case we slip up, and then criticizing ourselves when we inevitably do, is a tough way to live. People who score low for self-compassion are much more prone to being stressed or depressed.

So self-compassion is a great habit. And it is a habit. It’s something that we can train ourselves to have. Just as with my iterative approach to writing, we won’t suddenly produce full-fledged self-compassion out of thin air, so at first we’ll do it badly, as we do with all things worth doing. But we keep practicing, and get better at it as we do.

So, how do we get started? There are three things areas I’d like to focus on: perspectives for self-compassion, mindfulness, and kindness.

1. Perspectives for self-compassion

Everyone suffers. Everyone finds life hard in different ways. We all want to be happy and not to suffer, but happiness is often elusive, and suffering keeps coming along, often unexpectedly. We all mess up. Being human isn’t easy. These perspectives help us to let go of any expectation that life — and our lives in particular — should be free from difficulties. The also help us see that we shouldn’t expect creative work to be easy. As Stephen King said, “Sometimes you have to go on when you don’t feel like it, and sometimes you’re doing good work when it feels like all you’re managing to do is shovel shit from a sitting position.” Suffering — whether at the keyboard or in any other aspect of life — is normal.

Embrace this discomfort, because it’s through building your shit-shoveling muscles that you’re going to create.

2. Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a form of awareness in which we observe our experience almost as if we were watching an external event. Being mindful of our experience — and especially of painful experiences — is a critical component of self-compassion.

First we have to acknowledge that there’s pain present, and this isn’t always easy, because too often we believe the stories that spring up to distract us from our pain. So you sit down to write and it’s emotionally uncomfortable. Instead of just acknowledging the discomfort and starting to write, you decide it’s time for a snack, or time to dust the shelves, or to update Facebook. And off you go; the story has won: it’s prevented you from working through your fear. Being mindful creates a gap between the stimulus of discomfort and our response to it, and this gives us the freedom to choose how to act. I feel restless? It’s uncomfortable, but that’s OK. I’m feeling uncomfortable and I’m going to write.

Mindfulness involves acceptance. In the “gap” that mindfulness opens up, there is peace. It’s OK to suffer. It’s OK to feel frustration, to feel disappointed, sad, frustrated, hurt, despondent. These things are not signs that we’re failing, but that we’re human and engaged in the process of living. And when we’re in the act of creating, and we hear the inner critic saying that our work isn’t good enough, we can be mindful of that critical voice and decide not to believe it. Just keep going.

3. Kindness

Imagine you a friend shows you a draft of a short story, and it’s not very good. What do you say to them? “You idiot! You’re so stupid to try to write! No one’s ever going to want to read this crap!”? Of course not. But that’s the way we often talk to ourselves.

Elizabeth Gilbert says that self-discipline is overrated: “The more important virtue for a writer, I believe, is self-forgiveness. Because your writing will always disappoint you.” It’s by being kind and by forgiving the shortcomings in ourselves and our work that we get better at creating. This doesn’t mean that we recognize that a piece or work is bad, forgive ourselves, and leave it as it is. It just means not judging ourselves as “bad writers” for having written something that’s not yet good. It means treating what’s substandard as a first draft. It means looking at the crap head-on until we can figure our how best to shovel it. We accept imperfection and then go back and rewrite. Then rewrite again. And again.

What’s going on when we’re kind to ourselves is that the most mature and compassionate part of us is showing kindness to the part of us that’s most in pain. Our inner grown-up is comforting our inner child, giving it reassurance. Treating our painful feelings compassionately can be as simple as placing a hand on the part of our body where the hurt is most prominent, and saying “It’s OK.” We can offer reassurance by saying to our discomfort, “I know you’re hurting, but I’m here for you.” That might sound cheesy. That’s OK. I’d rather sound cheesy than be a blocked writer.

So next time you’re stuck on a project, staring at a blank page, or whatever your creative equivalent is, try on for size the perspective that discomfort is an integral — and valuable — part of creating. Have a mindful acceptance of any painful feelings that arise. Stay with the discomfort rather than turning away from it. Offer yourself some kindly reassurance as you shovel the shit.

Creating is hard, and that’s OK. Be an imperfectionist, and just keep doing it badly, at least at first. Because it’s worth doing.?

Related posts:

Loving your inner critic (Day 15)

Exploring Self Compassion: A retreat in Washington, Sep 26–29, 2013

Cultivating self-compassion (Day 29)

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

June 9, 2014

Turning problems into spiritual opportunities

I remember one day, thirty years ago, when I was living in Glasgow, Scotland, and was depressed. I can’t remember what I was feeling down about, exactly, although it definitely wasn’t a clinical depression. There were just things in my life that weren’t going well, and I was taking things too seriously. But there I was, in a state of self-pity, heading home on the bus. It was a rainy night, and being on a bus in Glasgow when it’s dark and raining, and the windows are running with condensation, is not a cheery experience. I guess I spent much of the bus-ride mulling over my woes and talking myself deeper into a state of despondency. Then I stepped out into the rain, and started trudging along the sidewalk in the direction of home. I must not have been paying enough attention, because the climax of my crappy day came when I tripped on a crack in the concrete and fell flat on my face in a puddle.

I remember one day, thirty years ago, when I was living in Glasgow, Scotland, and was depressed. I can’t remember what I was feeling down about, exactly, although it definitely wasn’t a clinical depression. There were just things in my life that weren’t going well, and I was taking things too seriously. But there I was, in a state of self-pity, heading home on the bus. It was a rainy night, and being on a bus in Glasgow when it’s dark and raining, and the windows are running with condensation, is not a cheery experience. I guess I spent much of the bus-ride mulling over my woes and talking myself deeper into a state of despondency. Then I stepped out into the rain, and started trudging along the sidewalk in the direction of home. I must not have been paying enough attention, because the climax of my crappy day came when I tripped on a crack in the concrete and fell flat on my face in a puddle.

How do you imagine I felt? Despondent? Humiliated? Angry? Actually, I was delighted. So much so that I burst out laughing, and had a grin on my face all the rest of the way home. I bet that sounds weird.

The reason I was so happy was that when I landed in the puddle, my first thought was “It’s a test.” I can’t say exactly why that thought popped up at that particular moment, but the notion of treating difficulties as if they were tests — of mindfulness, of character, of spiritual development — was one I’d heard a number of times. And so, instead of interpreting my fall as a sign that the universe had it in for me, or as a confirmation that things were going badly in my life, or as affirmation that I was a failure, I took it as an opportunity to practice patience, acceptance, and mindfulness, and to meet difficulties with good humor.

This kind of reinterpretation of our experience is called “reframing.” Reframing is one of the approaches that I teach to help people develop greater self compassion. Self compassion is when we relate with kindness to our painful feelings. Those feelings arise because ancient parts of the brain constantly scan our environment, looking for things that may be threats or benefits. When your mind detects a potential benefit, it sends signals into the body, creating feelings of pleasure — perhaps a sense of pleasant anticipation, or a warm glow. When your mind detects a threat, or potential threat, it sends signals that activate pain receptors in the body, and so we have a painful feeling, often in the heart or solar plexus. This painful feeling may be the heaviness of depression, or the nervousness of anxiety, or a feeling of hurt, for example. The point of this is to catch the attention of the rest of your mind, so that you can bring heightened awareness to the threat or benefit.

Falling flat on your face into a puddle is usually interpreted as a threat. We’ll assume that our clumsiness is a sign to others that we’re incompetent, and that our social status will drop, which is a painful thing.

But this thing is that this is just an interpretation, not a reality. It’s possible to change our interpretations — the filters that lead to the arising of pleasant and unpleasant feelings — either so that different feelings arise, or so we’re able to bear our suffering more easily.

We can reframe by considering unpleasant experiences as being a test, or an opportunity to cultivate patience.

We can reframe by considering our misfortunes to be the ripening of past karma, so that we’ll suffer less in the future, that particular stream of negativity having now passed though our life.

We can reframe by considering that unpleasant experiences are impermanent.

We can reframe by considering that unpleasant experiences are not us, but are simply passing though us, like clouds through the sky.

We can reframe by reminding ourselves that there are others who are suffering as badly, or worse, so that we feel a sense of gratitude.

We can reframe by seeing our misfortunes as being a way to develop empathy with others who are suffering, so that we can increase our compassion.

What’s we’re doing in all of these reframes is changing the mental filters that interpret our experience and that normally lead to the mind flagging up potential threats by creating unpleasant sensation. Now the mind registers our experiences as opportunities. We’ve turned a threat into an opportunity, and although we may not find that our unpleasant feelings vanish (though that happens sometimes) we’ll find them easier to be with, and so we won’t cause ourselves unnecessary suffering by engaging in self pity, and won’t cause others unnecessary suffering by acting out in anger.

Related posts:

When spiritual practice gets in the way of spiritual progress

Learning to love your suffering

Even-mindedness and the two arrows (Day 79)

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

May 30, 2014

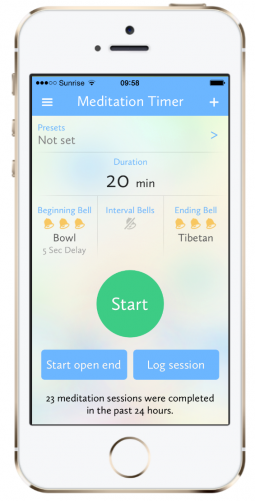

ZenFriend: A new meditation timer for iPhone

I’ve recently been trying out a new meditation timer app for iPhone. It’s very nicely designed and has a lot of promise. And it’s free today, and for the next two days.

I’ve recently been trying out a new meditation timer app for iPhone. It’s very nicely designed and has a lot of promise. And it’s free today, and for the next two days.

The app is called ZenFriend, and it has a very clean and, well, friendly design scheme. The other app I use for timing meditations is the well-known Insight Timer, which I enjoy using, although I don’t like the faux-wood design. Skeuomorphism is so iOS6!

As you’ll see from the first screenshot, there’s a nice blurred-out background image, beautiful typography, and nice clean “buttons” for pausing or ending your sit.

The interface for selecting the length of your sit, whether there are stages, and the kinds of bells used for the start, finish, and intervals (if any) is relatively easy to use. There’s a choice of four bells: one called “outside,” a standard meditation bowl, a Tibetan-style chime, and a Zen-style woodblock. You can create “presets” with your most common combinations of length and number of stages. In case you think the status bar at the top clutters the look, this disappears when the app is running, leaving you with a clean and undistracting screen.

The interface for selecting the length of your sit, whether there are stages, and the kinds of bells used for the start, finish, and intervals (if any) is relatively easy to use. There’s a choice of four bells: one called “outside,” a standard meditation bowl, a Tibetan-style chime, and a Zen-style woodblock. You can create “presets” with your most common combinations of length and number of stages. In case you think the status bar at the top clutters the look, this disappears when the app is running, leaving you with a clean and undistracting screen.

The timer keeps stats that can let you know how many sits and what length of time you’ve meditated in the last 30 days and since you’ve started using the app.

As with the Insight Timer, you can connect with friends and see how many other people are using the timer. ZenFriend isn’t as fully featured in this regard — there’s no map for example — but you can take that simplicity as a lack or as a welcome feature, depending on your taste. Since the app’s new there aren’t as many people using it as you’ll find on the Insight Timer.

You can set the app to remind you to meditate at particular times. This doesn’t have to be the same time every day.

So this is a nice alternative to the Insight Timer, especially if you like simplicity of design. And it’s free on the iTunes store for three days. I’d suggest getting it now and trying it out.

Related posts:

Meet Wildmind’s iPhone app!

Download Wildmind’s FREE iPhone app

Hit the ground sitting! Day 7 of our 100 Day Meditation Challenge

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

May 29, 2014

Progress, pitfalls, and more progress!

Last year we had an amazing response to our Free Bodhi campaign. Until last year I was up to my eyeballs in administrative tasks, like publicity, financial planning, and even buying office supplies. The Free Bodhi campaign was to raise funds so that we could take on Mark Tillotson as my business manager, and to free me up to teach and to write.

Last year we had an amazing response to our Free Bodhi campaign. Until last year I was up to my eyeballs in administrative tasks, like publicity, financial planning, and even buying office supplies. The Free Bodhi campaign was to raise funds so that we could take on Mark Tillotson as my business manager, and to free me up to teach and to write.

That’s worked out wonderfully! We reached our target, and now I spend my time writing and teaching. This has allowed Wildmind to run massive events as part of our Year of Going Deeper, like our Sit Breathe Love meditation challenge and our 100 Days of Lovingkindness, which both have had over 1,500 participants. Those events have been free, and we’ve asked for donations from participants to help cover the cost of running the office in order to make them possible.

Onward and upward!

Did you think there was a “but” coming? You’re right! The catch has been that, although many of the participants in our events have given very generously, the donations have come from a small minority. Plus, people who would have signed up for our online course, The Power of Mindfulness, have (naturally enough) been diverted to the free events, meaning that the donations have pretty much just covered the lost income from those courses. (Increasingly, though, I’ve been uncomfortable with those paid classes, and we’d like to move all of our activities to being on a donations basis. )

This has created a real financial crisis, and is putting us under a lot of strain. Our costs have increased because we have more staffing costs, and our income hasn’t gone up much. It looks like we’ll make it into early June, but whether we’ll be able to keep running our activities (the free meditation events, the blog, etc) beyond that is in doubt. Unless we can get more people to support us.

What’s been particularly helpful is regular monthly donations. At the moment about 115 people are supporting Wildmind with monthly donations ranging from $3 to $80. If we double the number of supporters, Wildmind should have a secure future.

So we’re encouraging you to make a monthly donation to Wildmind. The most common amounts that people donate are $3, $5, $10, $15, and $20. You can use the menu below to set up a donation via Paypal. (Prefer not to use Paypal?)

Monthly donation

Donation : $15.00 USD – monthly

Donation : $3.00 USD – monthly

Donation : $5.00 USD – monthly

Donation : $10.00 USD – monthly

Donation : $20.00 USD – monthly

To help show our appreciation, we’re setting up a rewards program. Anyone who donates $15 a month or more will receive two things:

Copies of all our new electronic products (MP3s, audiobooks, and ebooks) starting with the most recent at the time of signing-up (currently that’s our audiobook, the Power of Mindfulness)

Access to our Lifemember program, which gives access to the materials from nine online meditation courses.

All current donors who give $15 or more each month will be sent login details for the Lifemember program over the next month.

At the moment I often find myself carrying around an unreasonable amount of anxiety. Wildmind’s future has been insecure, and neither myself nor Mark (there’s only the two of us working here full-time) have health insurance, meaning that a simple accident or illness could be financially catastrophic (and no, even Obamacare is not affordable for us at the moment).

So your help would be much appreciated. It would allow us to focus on what we’re good at, which is making teachings on meditation more widely available.

Thank you!

Bodhipaksa

PS One time donations are fine as well.

If you prefer not to use Paypal, you can go to this page in our store, enter the amount you’d like to donate monthly into the text box, and then proceed to checkout. With your permission, we can turn this into a monthly recurring charge to your card.

Related posts:

Make a donation to Wildmind, and receive a 2.5 hour mindfulness audio download

Sit : Love : Give (Part II)

Sitting, loving, giving

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

May 27, 2014

The empty room, the plagiarist, and the boys in the basement

A lot of people have trouble understanding the Buddhist teaching of anatta (non-self). It’s hard to get the head around. They assume that “someone” has to be in control. They assume that they have a self that they somehow have to lose. And the thought of losing this self brings up problems: sometimes they fear that if they lose this self, then there will be no control (because someone has to be running the show). Sometimes they think that if there were not this “someone” in control, there would be no possibility of making choices: they assume there has to be “someone” who choses. They wonder how anyone can live without a self.

A lot of people have trouble understanding the Buddhist teaching of anatta (non-self). It’s hard to get the head around. They assume that “someone” has to be in control. They assume that they have a self that they somehow have to lose. And the thought of losing this self brings up problems: sometimes they fear that if they lose this self, then there will be no control (because someone has to be running the show). Sometimes they think that if there were not this “someone” in control, there would be no possibility of making choices: they assume there has to be “someone” who choses. They wonder how anyone can live without a self.

The Buddha didn’t actually teach that there is no self. I, and other teachers, often say that there’s no self, but this is just shorthand for saying that the kind of self you think you have doesn’t exist. The self you don’t have — the illusory self — is usually thought of as a unitary entity that sits inside you, pulling all your disparate experiences and actions into a single whole. It’s also in charge. And it’s conscious. You don’t have this kind of self — or in short-hand, you don’t have a self. Therefore you don’t have a self to lose, and those problems of “how to live without a self” don’t arise. You already don’t have a self, and you already do just fine. What you do have is an illusion of having a self, and that illusion makes you do less fine than if you got rid of it. The trouble is that once you believe you have a self, and you recognize that your self isn’t happy a lot of the time, you have to start wondering what kind of self you have. It’s obviously lacking! Maybe it’s broken! Maybe it’s not as good as other people’s selves! The illusory self becomes a real burden and gets in the way of our being happy.

An important aspect of this illusory self is that we assume it acts consciously. It seems natural to think that there are decisions we make consciously (I decide to lift my arm and it lifts), and decisions that we make unconsciously (I’m swayed by advertising to buy this brand rather than that brand of cereal, but am unaware of how my choices have been swayed). But this is incorrect. Even our so-called conscious decisions are made unconsciously. Ben Libet showed back in the 1980s that there’s a burst of activity happening outside of conscious awareness when we make a “conscious” decision to do something, like press a button, and that this activity occurs prior to conscious awareness of the decision having been made. More recently, the ability to look inside the brain in real time, through fMRI, has allowed researchers to know what a person is going to decide a full six seconds before the person themselves consciously knows what the decision is. The decision has been made outside of conscious awareness, and although we think that we’ve made the decision consciously, we haven’t. Here’s a video showing some of that research.

People think that this is a real problem because they assume that consciousness is the self, or that the self is consciousness. But neither of those things is true. This is all easy to accept once we’ve seen through the delusion of self, but if we’re still caught up in that delusion then it’s hard to process. There’s a sense of bafflement, or the whole question is dismissed as unimportant, or the problems with the self-view are acknowledge, but there’s a “Yes, but…”

Even if you’ve seen through that delusion, it’s hard to describe what’s actually going on, but it’s worth trying. One way of doing this is the form of teaching known as “direct pointing.” Direct pointing encourages practitioners to look beyond their delusions to see what’s really going on, and to look at the delusions and to realize their inadequacy. Direct pointing challenges our assumptions and encourages us to directly see what’s actually going on, rather than to have our view limited by our delusions. The evidence for non-self is omnipresent and should be obvious, but we choose to ignore it. But we don’t all have access to that kind of guidance.

It’s also useful, I think, to try to give people models that better help them to understand conceptually what’s going on. I’ve struggled to come up with metaphors that help people understand non-self, and I think I’ve finally come up with one that is accurate and (I hope) helpful.

The Boys in the Basement

Let’s start with the “boys in the basement.” This is a term that the novelist Stephen King uses to describe the unconscious creative forces that actually write his novels. Any writer knows that the words we write emerge, mysteriously, from “down there” in some part of the mind which is intelligent and creative, and to which there is no conscious access. There is a conscious awareness of what “the boys” produce, but we never see them at work. Those of us who write are very grateful for the work that the boys do, down there in the basement. We know that “we” (the conscious parts of us) don’t write anything.

Let’s start with the “boys in the basement.” This is a term that the novelist Stephen King uses to describe the unconscious creative forces that actually write his novels. Any writer knows that the words we write emerge, mysteriously, from “down there” in some part of the mind which is intelligent and creative, and to which there is no conscious access. There is a conscious awareness of what “the boys” produce, but we never see them at work. Those of us who write are very grateful for the work that the boys do, down there in the basement. We know that “we” (the conscious parts of us) don’t write anything.

While most of us recognize the operation of an unconscious intelligence, we naturally assume that there is also a “conscious self” that is “up here” and that makes some, perhaps most, of our decisions, and that it relates in some way to “the boys” — that other part of us that’s unconscious. We assume there is a conscious self and an unconscious self: conscious decisions and unconscious decisions. But there is in fact no conscious self. There’s just an illusion of a conscious self. And therefore there are no conscious actions, in the sense that the conscious part of us does not act; it merely is conscious of actions as they take place.

The basement and the empty room

Here’s a model to help you see how this works.

Here’s a model to help you see how this works.

Imagine a building with a central atrium, from which several other rooms branch. The atrium itself is empty. The other rooms contain various members of “the boys” — think of them as subcommittees with voting powers. To maintain the metaphor of the boys in the basement, imagine that all the rooms connected to the atrium are actually downstairs. The boys in the basement inhabit separate rooms, and so are not a coherent group. There may be several of them in one room, and the group members can have discussions amongst themselves. Even within one room they are not united. And each room has a different “culture” as you would expect to see in separate groups of people. Some are more emotional, some more rational. Some take a long-term view, some are very short-sighted. Some are selfish, some consider the needs of others.

Some of the basement rooms have connecting doors, so that discussion between different sub-groups of the boys can take place, entirely outside of awareness. But in other cases the rooms are entirely separate, apart from the fact that they all open into the atrium, upstairs. Therefore the groups in the different rooms are not all in direct contact with each other.

The communications channels are actually a bit more complicated than this, because we are not simply minds. We are embodied, and bodily sensations and movements also act as means of communication between otherwise separate rooms in the basement. And when we act in the world, we perceive our own actions, and this is itself a form of communication — information flowing from one room in the basement, to the world, back to other rooms in the basement. Speaking, for example, is not only an action that we take, but data that we receive, and so verbal communication with others includes communication between different parts of ourselves as well.

This model attempts to reflect something odd about the brain. It’s based on the fact that the brain was not designed from the ground up, but evolved in fits and starts, ad hoc, and by adding new “modules.” The brain is modular, and some modules cannot communicate directly with some other parts. That’s why I see the “boys” as being in separate rooms. Now the boys may be split up, but they have to communicate, somehow. And that’s where the central atrium comes in. This room represents our conscious awareness. There is no one in this room. The atrium is an empty space. It’s merely a conduit for communications. Therefore, there is no “conscious decision-making.” There is no “conscious mind” that can make decisions. What happens is that there are some decisions — but only some — that pass through the atrium and that various parts of the mind are aware of. We call this conscious awareness.

There are also decision-making processes that take place entirely outside of consciousness. This is like the “boys” having discussions amongst themselves — sometimes just the boys in one room, and sometimes the boys in different rooms having discussions though their connecting doors. This direct mode of communication of course bypasses the atrium, so that some decisions are made entirely outside of conscious awareness.

In this model, there is no central “self.” What we are is a kind of community. None of the members of this community is in charge of the whole show. There isn’t even one part of this community that knows everything that’s going on. Decisions don’t come from one internal source, but from debate amongst many different aspects of ourselves. None of the “boys” is fixed or permanent, either. They’re all in a state of flux.

How this works

To give an example of how this works, imagine a typical situation where there’s emotional conflict. Say someone has said something, and we’ve felt hurt, and we want to say something cutting back to them, but we are also aware that doing so may well lead to further conflict. I see it working like this:

To give an example of how this works, imagine a typical situation where there’s emotional conflict. Say someone has said something, and we’ve felt hurt, and we want to say something cutting back to them, but we are also aware that doing so may well lead to further conflict. I see it working like this:

We hear the cutting words. In one particularly deep and dark room in the basement, the message is taken as a threat. From this room, signals are sent down into the body, activating pain receptors in the abdomen. This is what we call “hurt feelings.” The parts of the brain that give rise to hurt feelings are ancient and not well connected to other parts of the brain. The creation of an internal painful stimulus is a form of communication among various rooms in the basement. In this peculiar, round-about way, one part of the brain communicates to others that there is a situation needing their attention.

Having received this embodied message, some of the boys who are more emotional may start clamoring for us to retaliate. Those messages pass through the atrium, and so we’re conscious of them. Some of the boys who take a cooler, longer-term view of our life suggest restraint. And those messages too pass through the atrium. Which will prevail? That depends on many factors, including past habits: are the boys in the emotional room stronger than those in the more rational room? Have they had more opportunity to be exercised in the past? But there is in effect a kind of debate going on. The atrium becomes a conduit for debate, although it’s not a debating chamber as such; the boys stay firmly in the basement, and only their messages travel through the atrium.

There is a debate, but there is at some point a resolution of the conflict. Let’s be optimistic and say that in this case the cooler parts of us make the stronger case and drown out the voices from the more emotional and retaliatory parts. The words, “I felt hurt when you said that,” emerge from one of the verbal parts of the basement. These words are not said by the “conscious mind” since there is no conscious mind that is capable of taking action. Instead, some of the boys send messages to the vocal apparatus and the words appear, straight from the unconscious. We may think we acted consciously, but that is a delusion.

The other person hears the words that have been uttered, has their own internal debate, involving their own “boys,” and they have their own response. Perhaps they are apologetic, and harmony between us is restored.

Acting and receiving feedback from our environment leads to changes within us. Our having acted, lessons are learned. Some of the boys are responsible for keeping track of patterns (in the past, this happened and that painful or pleasurable result ensued). The pattern “I did not retaliate and instead expressed that I was hurt” led to the result “I avoided further conflict and instead experienced harmony with the other person.” This correlation is logged, and will affect, in some small way, our future actions. This is how emotional intelligence arises.

In looking at brain activity, we see something very similar to the above. We see the deliberation of the boys in the basement represented as electrical and metabolic activity, which takes place before any conscious awareness of a decision arises. But the one thing I haven’t described is how we come to think that we consciously make decisions. Because there is a persistent and convincing delusion that when we say something like “I felt hurt when you said that,” we initiated the action consciously. We believe there is a conscious mind that makes things happen, even though no such thing takes place.

The “plagiarist,” and the illusion of self

Imagine, if you will, another room branching off of the atrium. This room hasn’t so far been mentioned. It contains another of the boys, and this one is a control-freak. He observes thoughts and impulses passing through the atrium, and he thinks “I did that.” I call him “The Plagiarist.” He doesn’t act, but he thinks he’s responsible for everything he sees going on. He sees a thought going by in the atrium, and he thinks he did it. He’s aware of a decision being made as it arises in consciousness, and he thinks it’s his decision, even though he wasn’t aware the decision had been made elsewhere, in a part of the basement that’s inaccessible to him. He’s like a student who sees a classmate handing in an essay, and he says, “I did that.” The weird thing is that he genuinely believes his own story, much as, in some Buddhist accounts of Brahma, the god genuinely believes that he is the creator of the universe, although he was merely a passive observer of the latest version of the universe as it condensed.

Imagine, if you will, another room branching off of the atrium. This room hasn’t so far been mentioned. It contains another of the boys, and this one is a control-freak. He observes thoughts and impulses passing through the atrium, and he thinks “I did that.” I call him “The Plagiarist.” He doesn’t act, but he thinks he’s responsible for everything he sees going on. He sees a thought going by in the atrium, and he thinks he did it. He’s aware of a decision being made as it arises in consciousness, and he thinks it’s his decision, even though he wasn’t aware the decision had been made elsewhere, in a part of the basement that’s inaccessible to him. He’s like a student who sees a classmate handing in an essay, and he says, “I did that.” The weird thing is that he genuinely believes his own story, much as, in some Buddhist accounts of Brahma, the god genuinely believes that he is the creator of the universe, although he was merely a passive observer of the latest version of the universe as it condensed.

The plagiarist, although he is nothing more another of the boys in the basement, gives us the sense that we have a self that is conscious and in charge, that responds to incoming stimuli, deliberates, and makes decisions. The plagiarist is absolutely not a self. The plagiarist does nothing. He knows nothing except what passes through conscious awareness. He has no access to the true decision-making parts of the mind, and is unable to initiate any action. He is a mere observer. All he does is claim responsibility for actions taken by others of the boys in the basement, and he attaches the label “I” to them. “I” did this. “I thought that. Even when those actions change and contradict each other, he still thinks they are his thoughts and actions. One moment “I” believe “I” want to get out of bed. The next moment “I” want to stay snug under the covers. The contradictions do not faze him. Buddhism calls him ahamkara, the “I-maker” and mamankara, the “mine-maker.”

I mentioned before, in passing, two examples in which we assume there are some decisions made by the conscious mind and other decisions made unconsciously. The examples are: 1) I decide to lift my arm and it lifts (a “conscious decision”), and 2) I’m swayed by advertising to buy this brand of cereal rather than another brand, but am unaware of how my choices have been swayed (an unconscious decision). Let’s look at each in turn.

1. I decide to lift my arm and it lifts. We assume that this is a conscious act: that the conscious mind made a decision to act, and an action followed. Actually, the decision to act was made unconsciously. We know this from neuroscience, where the activity that represents the decision to lift the arm takes place up to six seconds before we’re consciously aware that the decision has taken place. Say we’ve been asked, as part of a neuroscience study, to lift our arm randomly. The boys in the basement decide when a good time it, initiate the decision to act, the decision passes through conscious awareness, and the plagiarist, more or less instantaneously, says “I did that.” There is no conscious awareness of the decision until it emerges from the basement and passes through the atrium. There is still choosing going on. It’s just an illusion that it happens as a result of conscious choice.

2. In choosing one cereal brand over another, exactly the same process happens. In the basement, the boys take into account a number of factors regarding cereal — cost, familiarity, and the promises of excitement and healthiness (for example) communicated by the advertising we’ve been exposed to. The choice to choose the new cereal erupts into consciousness and the plagiarist once again says “I did that.” And so we feel we’ve made a conscious choice. When a scientist comes along and tells us that it’s likely we’ve been swayed by advertising, we may choose not to believe them, because we think we made our decision consciously.

Both situations are identical. Our problem is that we assume that the second case is an anomaly: that normally we make decisions consciously, and that that usual mechanism has been altered. In fact, all our decisions are made unconsciously, by the boys in the basement. The notion of conscious choice is an illusion.

Three experiments

The evidence for non-self (that is, that the kind of self we think we have doesn’t exist) is omnipresent, but we ignore it as an inconvenient truth. We’re very much invested in the notion that we choose consciously. So here are three experiments you can do that will help you to see through the delusion of conscious choice. These experiments are forms of the “direct pointing” that I mentioned earlier.

The evidence for non-self (that is, that the kind of self we think we have doesn’t exist) is omnipresent, but we ignore it as an inconvenient truth. We’re very much invested in the notion that we choose consciously. So here are three experiments you can do that will help you to see through the delusion of conscious choice. These experiments are forms of the “direct pointing” that I mentioned earlier.

Experiment 1: Seeing thoughts appear

Our thoughts should be generated consciously. We should be aware of what we’re going to think before the thought appears. So just sit quietly, think “I wonder what my next thought is going to be?” and watch. A thought will appear at some point. Did you know what that thought was going to be before it arose? Can you see how your own thoughts are a mystery to you? Can you notice how, even though you didn’t know what your next thought was going to be, there was an instant sense of “I did that; that’s my thought”? Can you slip deeper into observing your thoughts appearing, and let go of that clinging and identification — let go of that activity of claiming thoughts as your own? Can you let the origin of your thoughts be a mystery to you?

Now you might think, Yes but … I consciously generated the thought, “I wonder what my next thought will be?” Well, certainly that thought arose in consciousness, and you (or your plagiarist) took the credit for it when it appeared. But how did you create that thought? Are you aware of any process by which the words were assembled, and presented to conscious awareness? That thought was just another product of the boys in the basement. It was not a thought generated by the conscious mind, because the conscious mind doesn’t do anything.

Experiment 2: Hearing words appear

Our words should be generated consciously. We should be aware of what we’re going to think before the words appear, fully formed. Now, we sometimes do have thoughts that arise (“I’m going to say this…”), rattle around in the mind, and then appear as speech. Those thoughts, of course, come from the basement. Although the plagiarist takes credit for them, they weren’t created in consciousness, but only passed through it.

Most of the time, when we’re in the flow of conversation, our words go straight from the basement to our speech apparatus. It’s interesting to notice this. So the experiment here is to notice how, in the flow of conversation, you hear your own words at the same time as the person you’re conversing with hears them. Become an audience for your own words, and pay as much attention to hearing your speech as if you were listening to someone else.

You’ll notice that you rely on hearing your own speech to know what you’re saying! You have no special insight into what you’re going to say before you hear the words spoken aloud.

Experiment 3: Observing actions

Switching from hearing to seeing, start to notice your hands, and other parts of your body, in action. Become an observer of your own body. Typing is a great way to do this, because your hands are in front of you and easy to see, and because they’re moving automatically. You don’t have to instruct your hands where to go — they just type on their own. Or observe your hands on the steering wheel as you drive. Notice that you’re not having to consciously instruct them how to move. They’re moving on their own. Your conscious mind is not in control. The most it does is to take the credit for bodily movements that are controlled by your unconscious.

Once again, you may think, Yes, but … I can consciously instruct my arm to move.” Well, it appears so. But when you think “I’m going to move my arm” this thought comes from the boys in the basement. If you observe such a thought appearing, you’ll notice that you don’t really know where it’s coming from. And the action that follows that thought also comes from the basement. There are times when you try to move your arm and you can’t — for example if you’ve been hypnotized, or if you’re paralyzed by fear.

Free will

I hope can see from the above how free will and non-self aren’t incompatible. Actually, none of our decisions are made by a “conscious mind.” The best that happens is that some of our decisions become known in conscious awareness. But there is still choice happening. It’s just that it happens as a result of thinking processes that go on outside of conscious awareness, and which only later (if at all) pass into the “atrium” of conscious awareness.

I hope can see from the above how free will and non-self aren’t incompatible. Actually, none of our decisions are made by a “conscious mind.” The best that happens is that some of our decisions become known in conscious awareness. But there is still choice happening. It’s just that it happens as a result of thinking processes that go on outside of conscious awareness, and which only later (if at all) pass into the “atrium” of conscious awareness.

It must be said, though, that “free will” is an inappropriate term to describe the kind of freedom to choose that is open to us. The term “free will” is hyperbolic, because our ability to choose is always constrained. We can decide that we’re going to be happy from now on, or that we’re going to stop thinking in meditation, but those things aren’t going to happen. It’s not that these things aren’t under our conscious control: nothing is under our conscious control. The problem is that our unconscious us not a unified thing: it’s composed of varying “basement rooms” containing different groups of “boys” with different agendas. One group of boys may say “Now we’re going to stop thinking” but there’s no reason that other groups should listen to them. Some of the boys are really very short-sighted and primitive, and are inclined to generate thoughts and actions that lead to unhappiness. We just don’t have the kind of unified self that we like to think we have.

But we can and do make choices, even if they’re selected from a limited menu of options. We have a relatively free will. In fact the more mindfulness we develop, the more free our will is.

Non-self and training

Many Buddhist scriptures compare training the mind to training wild animals — especially to training wild elephants. We tend to assume, because we assume that there is a conscious self, that this represents the conscious self training the unconscious mind. But there is no conscious self, in the sense of a conscious entity that is able to act. What these metaphors represent is one part of the unconscious (some of the boys in the basement) training other parts of the unconscious (others of the boys in the basement).

Many Buddhist scriptures compare training the mind to training wild animals — especially to training wild elephants. We tend to assume, because we assume that there is a conscious self, that this represents the conscious self training the unconscious mind. But there is no conscious self, in the sense of a conscious entity that is able to act. What these metaphors represent is one part of the unconscious (some of the boys in the basement) training other parts of the unconscious (others of the boys in the basement).

Some parts of the mind are “wiser” than others, and are better able to predict what actions will lead, in the long term, to our happiness and well-being. Our problem at first is that the less wise, more short-sighted, more reactive parts of the mind are powerful and vocal. We may know, on some level, that yelling at people isn’t helpful or that resentment makes us unhappy, but it’s hard to resist, because the “boys” in charge of such actions are strong, and the other boys’ voices are weak in comparison. In fact for a long time we probably didn’t realize that these actions were unhelpful. Our evolutionary history tells us they are. But at some point some of the boys figure out that there are more helpful ways of behaving. From time to time they manage to “outvote” the other inhabitants of the basement, and we begin to associate those actions with pleasant consequences.

I gave an example of this above, where very ancient parts of the brain that keep track of patterns (this event in the past led to unpleasant consequences, while this other event led to a pleasant outcome) can be retrained.

In the elephant-training metaphor, the elephant trainer doesn’t represent a “conscious mind” or “self” training our unconscious forces, but a wiser unconscious part of us training less wise unconscious parts of us.

Where does the illusion of self arise from?

I don’t think anyone knows. I have a hunch, though, that it’s to do with how we create, in our minds, models of the world.

I don’t think anyone knows. I have a hunch, though, that it’s to do with how we create, in our minds, models of the world.

At some point in our early development we start to predict the future. We start to think in terms of “last time I wrote on the wall, mommy was angry; I’ve just written on the wall, and mommy will be angry again.” This is first of all done visually. We remember (see, hear) mommy yelling in the past, and remember how upset we were, and we imagine mommy in the future yelling again, and we feel upset. In this kind of mental activity, we have constructed not only a model of mommy, but a model of ourselves. We run this model of ourselves in various mentally simulated environments in order to predict the outcomes of various actions we take, and to predict how various future events might affect us. We end up with a model of ourselves in the substrate of our own mind. We create a kind of “mini-me,” or homunculus, in our imagination, and refer to it constantly in order to plan the future. Even when we recall the past, we are evoking this homunculus. Notice how, when you recall an event from the past, you see yourself as if from the outside, as one of the characters. You don’t see past events from an internal perspective, through your past eyes, but from an external perspective, looking at a model of yourself in a reconstructed simulation of the past.

Could this homunculus be the origin of our sense of self? Do we in some way take this simulated character representing ourselves to actually be ourselves? I suspect we do. Just for clarity, I’m positing this homunculus as being at least part of the illusion of self. I suspect that we imagine this homunculus as inhabiting the “atrium” — as inhabiting the conscious space that exists in part of the mind — and as being the part of us that generates our actions.

If this is what’s going on, it’s a convincing illusion, but also a burdensome one: this imagined self, as I’ve suggested, is always found to be inadequate. It is dukkha, unsatisfactory. It is always being compared to other imagined selves, and this comparison leads to an inevitable sense of insecurity. That insecurity leads to aversion and craving, which lead in turn to increased, and unnecessary, suffering. And so to reduce our aversion we need first to train the mind to act less from aversion and craving, and more from mindfulness and compassion, and second to lose the belief we have in this illusory self, which we imagine to exist inside us, pulling the strings, and acting consciously.

I hope the model I’ve offered here will help you to dispel that illusion of a self, and to lay down the burden that accompanies it.

Related posts:

Gratitude, creativity, and the Boys in the Basement

Gratitude, creativity, and the “boys in the basement”

Can the Unconscious Outperform the Conscious Mind?

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

May 11, 2014

Meditating with IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome)

Someone recently wrote to tell me that she suffers extreme embarrassment when meditating with other people, because her IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome) causes a lot of intestinal gurgling. She becomes self-conscious about these noises, finds that the anxiety about them dominates her meditations, and has been so upset at times that she’s left the meditation room in tears. Also, her anxiety around making noise actually causes her condition to get worse.

Someone recently wrote to tell me that she suffers extreme embarrassment when meditating with other people, because her IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome) causes a lot of intestinal gurgling. She becomes self-conscious about these noises, finds that the anxiety about them dominates her meditations, and has been so upset at times that she’s left the meditation room in tears. Also, her anxiety around making noise actually causes her condition to get worse.

I can appreciate her anxiety. I think we’ve all had times when we’ve been self-conscious about bodily noises (gas, swallowing, coughing, etc.), but to have it be more than an occasional thing must be very hard indeed.

If you’re affected by similar problems, I’d suggest letting people know that you have IBS and that it’s going to cause some noise if that’s at all possible. Just telling people that there’s a medical problem will probably help relieve some of the anxiety. Possibly you could ask the person leading the meditation to make an announcement. Any compassionate meditation instructor will be able to frame what they say in terms of practicing acceptance, etc.

To give other people the opportunity to practice patience or lovingkindness as they sit with any noise they may hear is an act of generosity. Don’t assume it’s a problem for them. I’ve had people flee the meditation room because they’ve had a cough and didn’t want to disturb people, when actually no one was disturbed — except perhaps being disturbed by the fact that another person hasn’t trusted them to be able to handle a bit of noise. So please do trust people. Give them the chance to learn to handle sitting with noise. You’ll be doing them a favor.

It may at first seem embarrassing to tell people you have a medical condition, but there’s no more shame to it than in having a cough, and you probably wouldn’t feel ashamed about letting people know you have a cold and that you’ll probably be coughing during a sit. You’ll get used to telling people this, so although it may be hard at first, it’ll get easier.

Meditation actually helps IBS sufferers. Three months after a group of IBS sufferers took an eight-week meditation course, 38.2% of them reported a reduction in severity of their IBS symptoms, according to a study carried out by Susan Gaylord, PhD, of the University of North Carolina’s program on integrative medicine. At the core of mindfulness is learning simply to observe our experience, without reacting to it with aversion or clinging. So if there is noise, or even pain, we simply notice those as sensations. If we notice ourselves tensing up or becoming anxious, we simply note that too, but we let go of the tension and let the anxious thoughts pass without getting caught up in them.

I remember some times I had problems with loud swallowing, and that has the same dynamic as my correspondent described — the more anxious you are about it the worse it gets. I got around this by trying to swallow as loudly as I could. For some reason it’s hard to swallow loudly on purpose. You might try something like that with your bowel sounds, if IBS is a problem for you. Now I know the intestines are not under conscious control, but if you pretend they are and give them permission to be as loud as they want (You go, intestines!) then that reassurance will help them to be more relaxed, and then they’ll be quieter. Also, if you’re almost defiantly trying to make noise, then the whole issue of being embarrassed about it becomes less important.

The practice of lovingkindness and self-compassion would also be helpful. First, start with your shame. Locate where in the body you feel the shame most strongly, and say “May you be well; may you be at ease.” Part of you is hurting, and it needs comfort and reassurance.

Do the same with your intestines. Show them love and reassurance like you would for a baby that had gas pains. Place a hand on your belly and say, “I know you’re struggling, but I’m here for you. I love you and I want you to be well.”

Have you been in the situation this person described? What’s worked for you?

Related posts:

When you’re afraid of meditating

Your anxiety deserves your love

Four tips for meditating in public

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

May 7, 2014

Sit : Breathe : Love (May 13 – Jun 9)

Want to experience the physical and mental health benefits of meditation, but have trouble setting up a regular practice?

Want to experience the physical and mental health benefits of meditation, but have trouble setting up a regular practice?

Sit : Breathe : Love is a 28 Day Meditation Challenge, with the aim of helping you to set up the habit of meditating daily. There are already almost 1,100 people signed up!

The benefits of regular meditation have been demonstrated again and again in multiple studies. Meditating makes you happier, is good for your health, protects your brain from aging, boosts your intelligence, and helps reduce pain, stress, and depression.

But it’s not easy to set up a regular meditation practice.

So we’re here to help you!

The aims in the 28 Day Challenge are:

To work toward building up a daily habit of meditation

If possible, to sit every day for 28 days

We set the bar for success low: although we hope you’ll meditate for 20 to 40 minutes a day, a “successful” day is one in which you’ve done some form of sitting meditation for at least five minutes — because there are Days Like That, aren’t there?

In the 28 Day Challenge we’ll teach you how to find a comfortable meditation posture (“Sit”); we’ll teach you how to calm your mind and settle agitated emotions by practicing the mindfulness of breathing (“Breathe”); and we’ll teach you how to appreciate yourself and others more through the practice of lovingkindness (“Love”). Hence, Sit : Breathe : Love”.

You’ll receive an email every day containing meditation instructions and links to guided meditations.

There is also a Community on Google Plus where you can share your experiences and receive support and encouragement from other participants in the challenge. If you already have a Google account, then joining the Community is easy. Even if you don’t have a Google account, it’s simple to set one up.

The challenge is free, although we do appreciate donations. In fact we need donations to cover our running costs.

Donate!

You can make a donation right now using the Paypal button below.

Register!

To participate, sign up for the challenge below. You’ll receive an email every day, containing meditation instructions and links to guided meditations. You can select multiple events using the checkboxes, and you also have the option to join our regular newsletter, which goes out twice a month and contains an exclusive article (not found on our blog) as well as links to significant posts and news stories published on our blog in the previous two weeks or so.

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; }

/* Add your own MailChimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block.

We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Register for any or all Year of Going Deeper events and (optionally) our regular newsletter.

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name *

Last Name *

Wildmind

Meditation Newsletter

Sit : Breathe : Love #2 (May 13 – Jun 9, 2014)

60 Days to Jhana (Jun 6 – Aug 10, 2014)

Sit : Breathe : Love #3 (Aug 13 – Sep 9, 2014)

42 Days: 6 Elements (Sep 12 – Oct 23, 2014)

Sit : Breathe : Love #4 (Oct 27 – Nov 23, 2014)

4 Weeks of Insight (Nov 28 – Dec 25, 2014)

var err_style = '';

try{

err_style = mc_custom_error_style;

} catch(e){

err_style = '#mc_embed_signup input.mce_inline_error{border-color:#6B0505;} #mc_embed_signup div.mce_inline_error{margin: 0 0 1em 0; padding: 5px 10px; background-color:#6B0505; font-weight: bold; z-index: 1; color:#fff;}';

}

var head= document.getElementsByTagName('head')[0];

var style= document.createElement('style');

style.type= 'text/css';

if (style.styleSheet) {

style.styleSheet.cssText = err_style;

} else {

style.appendChild(document.createTextNode(err_style));

}

head.appendChild(style);

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

var mce_preload_checks = 0;

function mce_preload_check(){

if (mce_preload_checks>40) return;

mce_preload_checks++;

try {

var jqueryLoaded=jQuery;

} catch(err) {

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

return;

}

var script = document.createElement('script');

script.type = 'text/javascript';

script.src = 'http://downloads.mailchimp.com/js/jqu...

head.appendChild(script);

try {

var validatorLoaded=jQuery("#fake-form").validate({});

} catch(err) {

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

return;

}

mce_init_form();

}

function mce_init_form(){

jQuery(document).ready( function($) {

var options = { errorClass: 'mce_inline_error', errorElement: 'div', onkeyup: function(){}, onfocusout:function(){}, onblur:function(){} };

var mce_validator = $("#mc-embedded-subscribe-form").validate(options);

$("#mc-embedded-subscribe-form").unbind('submit');//remove the validator so we can get into beforeSubmit on the ajaxform, which then calls the validator

options = { url: 'http://wildmind.us6.list-manage1.com/...?', type: 'GET', dataType: 'json', contentType: "application/json; charset=utf-8",

beforeSubmit: function(){

$('#mce_tmp_error_msg').remove();

$('.datefield','#mc_embed_signup').each(

function(){

var txt = 'filled';

var fields = new Array();

var i = 0;

$(':text', this).each(

function(){

fields[i] = this;

i++;

});

$(':hidden', this).each(

function(){

var bday = false;

if (fields.length == 2){

bday = true;

fields[2] = {'value':1970};//trick birthdays into having years

}

if ( fields[0].value=='MM' && fields[1].value=='DD' && (fields[2].value=='YYYY' || (bday && fields[2].value==1970) ) ){

this.value = '';

} else if ( fields[0].value=='' && fields[1].value=='' && (fields[2].value=='' || (bday && fields[2].value==1970) ) ){

this.value = '';

} else {

if (/\[day\]/.test(fields[0].name)){

this.value = fields[1].value+'/'+fields[0].value+'/'+fields[2].value;

} else {

this.value = fields[0].value+'/'+fields[1].value+'/'+fields[2].value;

}

}

});

});

$('.phonefield-us','#mc_embed_signup').each(

function(){

var fields = new Array();

var i = 0;

$(':text', this).each(

function(){

fields[i] = this;

i++;

});

$(':hidden', this).each(

function(){

if ( fields[0].value.length != 3 || fields[1].value.length!=3 || fields[2].value.length!=4 ){

this.value = '';

} else {

this.value = 'filled';

}

});

});

return mce_validator.form();

},

success: mce_success_cb

};

$('#mc-embedded-subscribe-form').ajaxForm(options);

});

}

function mce_success_cb(resp){

$('#mce-success-response').hide();

$('#mce-error-response').hide();

if (resp.result=="success"){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(resp.msg);

$('#mc-embedded-subscribe-form').each(function(){

this.reset();

});

} else {

var index = -1;

var msg;

try {

var parts = resp.msg.split(' - ',2);

if (parts[1]==undefined){

msg = resp.msg;

} else {

i = parseInt(parts[0]);

if (i.toString() == parts[0]){

index = parts[0];

msg = parts[1];

} else {

index = -1;

msg = resp.msg;

}

}

} catch(e){

index = -1;

msg = resp.msg;

}

try{

if (index== -1){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

} else {

err_id = 'mce_tmp_error_msg';

html = '

'+msg+'

';

var input_id = '#mc_embed_signup';

var f = $(input_id);

if (ftypes[index]=='address'){

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index]+'-addr1';

f = $(input_id).parent().parent().get(0);

} else if (ftypes[index]=='date'){

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index]+'-month';

f = $(input_id).parent().parent().get(0);

} else {

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index];

f = $().parent(input_id).get(0);

}

if (f){

$(f).append(html);

$(input_id).focus();

} else {

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

}

}

} catch(e){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

}

}

}

Related posts:

Join us on January 1st for our 28 Day Meditation Challenge, “Sit : Breathe : Love”

Sit : Breathe : Love breaks 900 subscribers!

Sit : Love : Give (Part II)

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

May 4, 2014

Six Element Practice: Guided Meditation MP3

Another guided meditation from the retreat I’m co-leading with Sunada and Aryaloka. This one’s the Six Element Practice, which is a reflection on non-self.

The quality of the recording is not great, and the only editing I’ve done is to increase the volume and to remove a cough. You’ll hear the building creaking, and people shuffling (and no doubt some coughs that I missed.

Still, I hope it’s of benefit:

Related posts:

Lovingkindness meditation: another guided meditation MP3

Guided meditation: The six element practice

Mindfulness of Breathing: another guided meditation MP3

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

Lovingkindness meditation: another guided meditation MP3

Another of the recordings from the retreat I’m currently co-leading at Aryaloka retreat center. The retreat’s on creativity and meditation, and I’ve been noticing how self-critical (i.e. “perfectionist” many creative people can be. So I threw in this short meditation at the end of the evening in order to connect us with the fact that life is messy, that we don’t “do life” perfectly, and how this can be an opportunity for us to develop more empathy and kindness rather than to beat ourselves up.

I hope this is of benefit to you. (By the way, the meditation room is kind of noisy, and the recording equipment wan’t great. And it’s only very lightly edited to remove some of the coughs.)

Related posts:

Mindfulness of Breathing: Guided Meditation MP3

Mindfulness of Breathing: another guided meditation MP3

Guided Meditation: Mindfulness of Breathing

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

May 3, 2014

Rebirth and radical honesty

This morning I had an email from Sheila, one of our newsletter subscribers. She’d shared the article called “The Buddha’s Wager” with a Buddhist friend, and wasn’t sure how to address the points her friend had raised. So here’s what her friend had written:

This morning I had an email from Sheila, one of our newsletter subscribers. She’d shared the article called “The Buddha’s Wager” with a Buddhist friend, and wasn’t sure how to address the points her friend had raised. So here’s what her friend had written:

i find it fascinating that ‘sceptics’ want to know how consciousness can survive the death of the brain – when we have no inkling of how consciousness arises in a living brain – to me it’s as much of a leap of faith to believe that other people are conscious as it is to believe that ‘my’ consciousness can survive the death of my body. we are all profoundly agnostic about almost everything…. i find a belief in rebirth gives a me a sense of meaning – of possible progress – i still don’t understand how anyone can profess to be seeking Enlightenment – in the Buddha’s sense of a release from suffering – and not believe in rebirth. if death is the end of suffering then what’s all the fuss about? let’s just die….

And here’s what I wrote to Sheila:

Thanks for writing with these interesting questions. It’s always interesting for me to meet, even indirectly, someone like your friend who sees life and Dharma practice in very different ways.

To take things out of order, with regard to the whole idea that life is pointless unless you believe in rebirth, I’d quote the Kalama Sutta, and gently point out that the Buddha seems to have disagreed with your friend’s position. If he taught the Kalama sutta, then he clearly thought that Dharma practice made sense even if you don’t have a belief in rebirth.

[To quote from the Buddha's wager, in that sutta the Buddha tells the Kalamas that his "noble disciples" acquire four assurances in the here and now. The first two of these assurances are:

If there is a world after death, if there is the fruit of actions rightly and wrongly done, then this is the basis by which, with the break-up of the body, after death, I will reappear in a good destination, the heavenly world.

But if there is no world after death, if there is no fruit of actions rightly and wrongly done, then here in the present life I look after myself with ease — free from hostility, free from ill will, free from trouble.So the Buddha is saying here that his disciples can practice the Dharma and benefit from that practice without believing in rebirth. What's more, these disciples have mind "free from hostility, free from ill will, undefiled, and pure." In other words, these are enlightened disciples of the Buddha, who have the assurance that their practice is worthwhile, even if they don't know whether rebirth happens. You can go all the way to enlightenment and still not be convinced that rebirth is true!]*

Your friend gets her source of meaning from rebirth, but those of us who are skeptical about rebirth get our meaning elsewhere. Life to me doesn’t need any justification, so “let’s just die” would strike me as being a weird position to take, or even to imagine that people might take (unless, say, they were profoundly depressed). I don’t think it takes much empathy to recognize that people with differing views find life, and dharma practice, meaningful without the conviction that there is rebirth.

I hear similar arguments from Christians, who say that God is what gives life meaning, and if you don’t believe in God then you have no reason for living and might as well kill yourself. If your friend doesn’t believe in God then perhaps she might recognize that she’s adopting the same attitude in thinking that her source of meaning is the only possible source of meaning.

I wonder what she means by “let’s just die?” That without a belief in rebirth we should just kill ourselves? That’s absurd, since I don’t need a belief in rebirth to feel that my life is meaningful. That we should cease practice and just hang on until we die and then our suffering will all be over? That’s also absurd, since she’s suggesting that we should stop doing the things we find meaningful because we don’t get our sense of purpose and meaning in precisely the same way she does.

We all have different ways of finding purpose in life, and to me life is meaningful in and of itself. To be alive and conscious is a constant wonder and miracle. But in addition, seeing suffering in myself and others, and recognizing that most of that suffering is unnecessary, I find meaning in wanting to free myself and others from suffering. Now I can see how a Christian can think that serving god is a source of meaning or how the idea of pursuing enlightenment over many lives can give meaning, so I wonder why your friend can’t recognize that other things give my life meaning? I mean, hasn’t she ever *asked* someone with different beliefs what their source of meaning is? To just assume that they have none suggests some kind of lack of empathy or imagination.

To take your friend’s first point, I don’t think it takes much of a leap of faith to accept that other people are conscious. I am a human, and I am conscious. Other humans show the external signs, though facial expressions, words, etc., that they are experiencing the world in a similar way to me. So it would be bizarre, in my opinion, to assume that other people are not conscious. Assuming that consciousness survives death is an assumption of a completely different order from assuming that others are conscious.

As for agnosticism, I am profoundly agnostic when it comes to the teaching of rebirth. I have no evidence either way. It seems unlikely to me that consciousness can somehow function separate from a body (if I don’t need a body to be conscious, why does brain damage affect our ability to think?) and transfer itself to another body. There are on the other hand accounts of past-life memories, but few of us have had the opportunity to check those out first hand, and even if we did there’s no way we can rule out the possibility of the supposed memories having been acquired through some other route. I was advised to watch a video about a Scottish boy who apparently remembered a part life. I didn’t find it very convincing, and when much was made of his knowing that on the island of Barra, planes use the beach as a landing strip, it seemed quite possible to me that he’d seen this on TV. I try to keep a reasonably close eye on what my kids see on TV, but they’re always coming up with surprising things that they’ve picked up, and that I’d no idea they’d been exposed to. So most of the evidence that I’ve seen is rather shaky (plus there are some well-known instances of supposed memories having come from books people have read). On the other hand, we live in a very strange and wonderful universe, where there’s quantum entanglement. We don’t even know what 95% of the matter in the universe is made up of! So I’m not ruling anything out.

For me, being agnostic about rebirth is actually an ethical position. The Buddha promoted a sort of radical honesty (although of course we’re to be kind as well as honesty). The suttas describe truthful speech like this: