Tiago Forte's Blog, page 8

April 1, 2023

Our 2023 Goals at Forte Labs

Here are our company goals for 2023, which we’re sharing for accountability and collaboration.

CompanyOur goal is to reach gross revenue of $3 million in 2023. This sales volume would give us healthy margins, allow us to compensate our people well, and make major investments for the future.

YouTube2022 was our first serious investment in YouTube, and this year, we’re going to continue growing our channel while also connecting it more closely with the rest of the business.

Grow our channel to 300,000 subscribersAfter the meteoric growth we saw last year, from 20,000 to 140,000 subscribers, we’re once again setting a lofty target to double our following to 300,000.

We’re going to do that while continuing to optimize for monetization via our products and services so people can go deeper on the ideas they’re introduced to on our channel.

Launch our YouTube Partner Program with 6–8 videosIn 2023 we’ll begin partnering with select, premium brands to create custom YouTube videos that introduce our subscribers to their products.

We’ll work exclusively with sponsored partners who are the absolute best fit: willing to fund dedicated videos (not 90-second inserts) where we conduct detailed product walkthroughs with Tiago, for products we’d happily cover anyway (if we had infinite time and resources)

Ideally, these will be true long-term partnerships, not just short-term user acquisition. We’ve booked our first 3 partnerships and are looking for 3-5 more.

If you’re a good fit for that kind of partnership, reach out at hello@fortelabs.com, and let’s talk!

Publish new videosWe are planning over 30 videos on Second Brains and digital productivity, including dedicated videos on the following topics:

Tiago’s Second Brain Tour – a guided look behind the scenes of my own personal Second Brain systemA deep dive series into PARA, my ultimate organizational system for digital informationA “trailer” for my book Building a Second Brain to make the key ideas easy to understand and shareCollaborations with a wide variety of thought leaders and content creators on how they use digital notesMarketing/Content2022 was focused almost completely on audience growth, and this year we’re switching our focus to growing revenue.

Measure & increase the conversion rate of our funnelWe’re going to be putting more attention into metrics this year, regularly tracking net new subscribers to our email list, the conversion rate from email subscribers to our portfolio of products, and revenue from other sources besides courses, with the goal of diversifying our business.

Launch newsletter sponsorshipsFor the first time ever, we’re beginning to partner with select sponsors for our weekly email newsletter, which reaches over 100,000 people each week with consistent 50%+ open rates.

If you have a brand you’d like to share with our audience, please get in touch here!

Kick off our affiliate marketing programWe’ve begun officially recommending the tools, apps, and online platforms we use to run our business and manage our company Second Brain, which you can find here.

For those who complete our flagship program Building a Second Brain, we are also now recommending the courses and programs of other online educators we trust and believe in to help them continue their learning journey.

Launch a premium offeringWe don’t yet know exactly what this will look like, but we’re seeing a lot of demand from entrepreneurs, creators, executives, and business owners for a premium offering that allows them to work with us more closely and intensively.

We’ll explore the absolute best ways we can serve these leaders this year.

Keep our audience growth rate stableGrowing our audience won’t be our main focus this year, but with our content flywheel spinning, we are seeking a consistent growth rate across all our main channels this year.

Operations/EducationWe merged our Operations and Education teams recently after realizing that every program we offer relies strongly on effective operations.

The new combined team will be prioritizing training effective facilitators for our courses, with the goal of increasing retention rates and growing revenue by keeping members engaged, satisfied, and committed to the community.

Maintain the BASB Membership CommunityGraduates of our online course can now join an ongoing membership community which we call the BASB Membership. As part of the Membership, we offer consistent content updates, host learning events, and offer exclusive access to other resources for course alumni only.

Train new BASB facilitatorsWe will develop and document a standardized process for onboarding, managing, and offboarding new facilitators for BASB cohorts this year, with the goal of giving our students the best training suited to their needs, choice of platform, and professional background.

If any of these goals overlap with yours and you see a way we could work together, please reach out to us at hello@fortelabs.com.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post Our 2023 Goals at Forte Labs appeared first on Forte Labs.

March 23, 2023

100,000 Copies Sold: My Long-Term Goals for the Building a Second Brain Book

We recently crossed the astounding milestone of 100,000 copies sold of my book Building a Second Brain!

That’s just in the US and UK, and over the next few months, it will go on sale in 20+ other countries and languages around the world.

I have to be honest: every goal that I ever imagined for this book has been fulfilled. I feel a little dumbfounded and very much in awe that we’ve reached the limits of my imagination just 10 months after its release.

I sat down recently to brainstorm a list of 20 “ridiculous” new goals for the next chapter of the book’s life. I have no idea how many of these might come to pass, and many of them are honestly purely vanity goals, but they are meaningful to me nonetheless.

Hosting a 1,000-attendee conference in LA or Long BeachHaving a scientific paper published on my work in a major academic journalReceiving an invitation to guest lecture at Harvard, Stanford, or another Ivy League universityRunning pilots to teach BASB in 100 K-12 schoolsReaching 1 million copies sold within 5 yearsAppearing on the New York Times bestseller listSeeing a Times Square billboard advertising the bookHaving a feature-length film made on BASB with a wide theatrical releaseBeing name-dropped in a chart-topping rap or pop songAppearing on an episode of the Hidden Brain podcastCollaborating on an exhibition at a major museum on the “history of thinking tools”Creating a board game for children to learn the principles behind BASBLanding a Tim Ferriss podcast interviewBeing thanked onstage at a music or film award ceremonyLanding an Oprah interviewSpeaking in front of a stadium or arena-sized audienceRunning a Super Bowl adDoing a Mr. Beast collab on YouTubeSigning a Netflix production deal to produce a BASB documentary, movie, or limited seriesPhoto of the book being read in space or on Mars by astronautsIf you know of any way to make any of these happen, please let me know!

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post 100,000 Copies Sold: My Long-Term Goals for the Building a Second Brain Book appeared first on Forte Labs.

March 13, 2023

Team Knowledge Management: How to Use PARA in Your Organization

Our digital world is constantly colliding and overlapping with the digital worlds of others.

No one is an island, and that is especially true in our hyperconnected age where information can be so easily shared and intermixed. I’ve long advocated for individuals to create a personal system of knowledge management to help them skillfully navigate this world of information abundance – which I call their “Second Brain.”

One of the most common questions people have as they begin implementing what I teach is how they can share it with others. Whether by teaching their colleagues how to organize their own private thoughts and ideas, or creating a shared platform where everyone they work with can collectively document the knowledge they use.

Knowledge is meant to be shared, so this is a natural direction to move in once you start to experience the power of organizing your digital world.

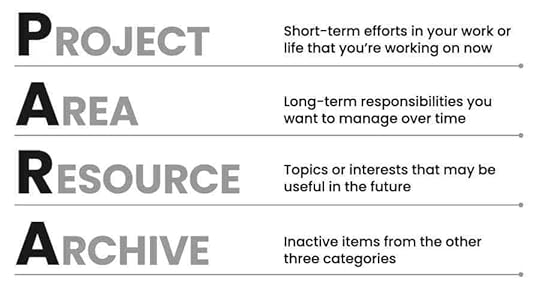

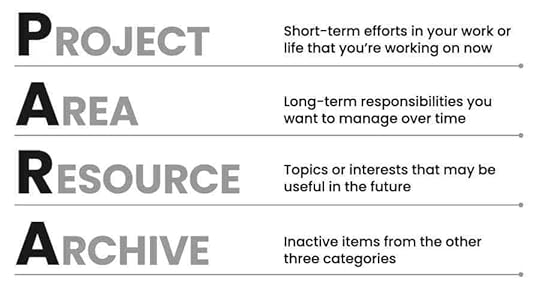

It all begins with PARA – the cornerstone of my book Building a Second Brain and the starting point for organizing digital information of any kind. PARA is a system and a methodology for making knowledge stored in digital form far more accessible and useful, and it applies just as well to teams and companies as to individuals.

I’ve consulted with many organizations on how to implement PARA, from multi-billion dollar international financial institutions like the World Bank, to leading biotech firms like Genentech, to innovative startups like Sunrun.

We all operate in a knowledge-based economy, and thus the ability to document what your people know and help them access that knowledge when it’s needed is a crucial capability for any organization. I would say it’s even essential for survival.

A Bottom-Up Approach to Knowledge ManagementPARA is part of a discipline called “Knowledge management,” or KM for short.

KM is an extensive field with many research studies, academic journals, and conferences stretching back decades. Its purpose is to find ways for people to effectively share their knowledge with each other to advance the organization’s goals.

Let me give you my controversial take on Knowledge Management as it is usually practiced: it’s often used by management as a tool for top-down control.

A wiki or knowledge base is created one day out of the blue, and staff are told to “share their knowledge” by inputting what they know. On the surface, this seems like a perfectly reasonable proposition. We are hired to contribute our knowledge to our employer, right? But in practice, there are multiple problems with this “top-down” approach to knowledge management.

First, it takes a lot of time and effort to articulate one’s knowledge in a form that can be easily understood by others. And typically, staff aren’t being evaluated or compensated for this effort, which means it is essentially a distraction from the outcomes they are being evaluated on.

Second, there are risks to sharing one’s knowledge so openly. You don’t know how it will be interpreted, where it will end up, or whether you will be properly credited. It might even be taken out of context and used against you.

Finally, there is always the fear lurking in the back of people’s minds that by sharing their hard-won knowledge, they are making themselves obsolete. If your most valuable knowledge can be fully documented and made searchable, why should they keep you around?

All of this leads to my conclusion that modern organizations need to take a “bottom-up” approach to knowledge management instead of a top-down one. It can’t be about “extracting” knowledge from their people; it has to be about empowering them to do their absolute best work.

The following recommendations are centered on the needs and goals of the individual. It’s not that the organization isn’t important – it’s that the organization only benefits when staff embraces and feels inspired by the approach to knowledge sharing they’ve been asked to follow.

I’ll summarize my years of consulting experience into 5 concrete recommendations for how to practice knowledge management effectively within teams.

Here are my 5 recommendations at a glance:

Get clear on your organization’s flavor of PARATrain people in how to use PARAKeep only shared projects on shared platformsDefault to informality whenever possibleEncourage a culture of writing1. Get Clear on Your Organization’s Flavor of PARAMy first recommendation is to define what PARA looks like and how it works for your team specifically.

Even if you’ve decided you’re going to follow my advice to the letter, there is always a “flavor” of PARA that makes sense for your culture. This can include decisions such as:

What is our definition of a “project,” “area of responsibility,” “resource” and “archive”?What needs to happen when we kick off a new project for it to be considered “active”?What needs to happen when a project gets completed, put on hold, or canceled (for it to be considered “inactive”)?Who is responsible for maintaining the standard for each shared area of responsibility?What are the officially supported platforms on which PARA will be used?What are the strict rules, softer “rules of thumb,” dos and don’ts, and cultural norms that govern how people will use PARA?Who will be the “PARA Champion” who oversees its implementation and makes sure the guidelines are being followed?I suggest summarizing these decisions in a one-page “PARA Guide” for your team where everyone can reference it.

2. Train People in How to Use PARAI recommend viewing the implementation of PARA in your team as primarily a training challenge, not an organizational or technical challenge.

The fact that it takes me thousands of words to explain what PARA is and how it works should be a clue that even with such a dead simple method, people still need to learn it. They have to change their mindset, let go of limiting beliefs, observe and practice new behaviors, and then integrate all of that into their day-to-day work habits.

The first and biggest pitfall I see managers succumb to is the idea that they can implement PARA without teaching their people anything. That they can “install” it on their shared cloud storage drive like a piece of software and people will somehow magically know how to use it.

Nothing could be further from the truth. I promise you: you will need to train your people not just in how PARA works, but how it works in your team. The document you created previously with all the norms and rules of PARA will serve as a reference, but you will also need to make presentations, conduct training, and facilitate discussions with your staff around what that looks like.

PARA is really a set of common behaviors that everyone on your team will need to adopt: a shared set of assumptions, conventions, and policies that govern how people create files and folders, where they put them and why, and in what circumstances they should retitle, move, or archive them.

3. Keep Only Shared Projects on Shared PlatformsA tendency I often see is for teams to want to centralize all digital assets of their team in a single, all-encompassing place. The thinking goes: if all this digital content is potentially valuable, shouldn’t everyone have access to it?

The answer is no. You absolutely do not want everyone to have access to everything. Here’s why: for a piece of information to be understandable and usable by a wide variety of people, it has to be highly formal and structured, which takes a lot of time and effort. And you shouldn’t spend that time and effort without very good reason.

For example, if you have some notes on a book you’re reading, meant only for your personal use, those notes can exist in a very informal, casual, free-form state. You don’t need to define your terms, don’t need to add headings or sections, don’t need an outline or table of contents, and can add highlights and annotations without much context at all. In other words, you can depend on the fact that the person making the notes and the one retrieving them are the same person – you.

However, if you want to share those book notes with even one other person, suddenly the whole situation changes. There is a chasm that separates any two minds. You have no idea what the other person knows, remembers, or understands. You now have to add a considerable amount of context and structure to make sure they have a shot at understanding what your notes contain. Now expand that to dozens or hundreds of others, and the effort needed to make that knowledge intelligible explodes.

Adding context and creating structure – including steps like defining your terms, making your assumptions explicit, or bridging the logic from one point to another, among many others – are cognitively expensive. And every minute you spend adding formality and structure to a document is a minute you’re not spending moving your team’s projects and goals forward. There is always a tradeoff.

I recommend advising your staff to keep all their notes, files, and documents in their own individual PARA folders by default. That way they can remain informal and messy until the moment more formality is needed.

Only when a project or area becomes collaborative, with multiple people involved, should it be moved to shared Projects or Areas folders. If you think about the totality of all the work the entire team takes on, most of it will be at the individual level. Thus only a minority of the organization’s overall workload should reside in the shared PARA system.

4. Default to Informality Whenever Possible

4. Default to Informality Whenever PossibleI previously said that it takes a lot more context and structure – in other words, a lot more formality – to make content intelligible for a wider audience. However, even in the case where that’s necessary, you should still default to the minimum level of formality you can get away with.

I often see organizations default to a high level of formality in all their communication. For example, a complex feedback form with 12 required fields, a memo template that reads like a government decree, or a company wiki with 10 levels of hierarchy requiring you to find the exact place something belongs.

Defaulting to overly elaborate information-sharing is a constant temptation inside organizations because it feels like the right thing to do. It feels responsible to make precise workflows, comprehensive questionnaires, and elaborate rules to ensure people do things “right.” No one gets in trouble for being too rigorous or too precise in the documentation they create.

Yet what few seem to realize is that every bit of formality carries a hidden cost. It extracts a toll on people’s time and energy that will inevitably show up in the form of frustration, discouragement, and a sense of defeat.

When you force people to follow elaborate rules whose purpose they don’t understand, you are robbing them of the enthusiasm and excitement they need to do their most creative, inspired work. No one will complain, but under the surface, their morale will suffer.

It doesn’t have to be that way. One of the most powerful but also unusual cultural norms I’ve noticed within companies is the expectation that informality is not only okay, it’s preferred. I believe this is one of the secret weapons of tech startups – the beanbag chairs and ping-pong tables don’t make a difference by themselves, but they imply a culture where it’s okay to be yourself. That attitude of informality then carries over into how people plan, strategize, communicate, and collaborate, which is a much more natural and effective way to work!

Formality is needed only in very specific, limited circumstances. For example, when doing randomized controlled trials for a drug you’re developing, or when drawing up blueprints for a new bridge, or when handling toxic chemicals. Beyond this kind of dangerous or high-risk situation, informality should rule.

As important as informality is, it depends completely on clear, transparent communication. In the absence of clear communication, overly bureaucratic processes will be created to pull the necessary information out of people, leading back to a top-down approach.

That’s why the fifth and final element is the lynchpin of effective Knowledge Management within organizations.

5. Encourage a Culture of WritingOne thing you’ll quickly discover when it comes to Knowledge Management is that it is essentially a form of communication.

A document, note, or other digital asset is a message being communicated through time. When it comes to team knowledge management, the quality of that communication becomes even more important, since you don’t know who exactly will be receiving it on the other end.

What determines the quality of a piece of communication? Well, it turns out it’s the same things that determine the quality of a piece of writing, for example:

Is it interesting and attention-grabbing? (Does it make people want to read it?)Is it precise and clear? (Can people easily understand what it’s trying to say?)Is it empathetic? (Is the writer seeing things from the reader’s point of view?)Does it help people solve a problem? (Is it useful and effective, or merely interesting?)Does it inspire people to take action? (Does it make it easy for people to apply it?)It turns out that effective knowledge management within an organization essentially boils down to how well people write down what they know, and share or otherwise express it in a form that other people benefit from.

The skills learned through writing also translate to other kinds of “knowledge” that aren’t in textual form: images, graphs, photos, GIFs, diagrams, slides, etc. also need to be intelligible and useful to future receivers.

Writing is the individual skill most relevant to Knowledge Management, and the fact that most people don’t write particularly well or often indicates why KM is also lacking in most organizations. To put it simply: the only way to share knowledge effectively is to create a culture of writing within your team.

Here are some ideas for how to do that:

Senior leadership can set an example by regularly sharing their most important ideas and decisions in writingStaff at all levels can be encouraged to take the time to express their thinking in writing, and rewarded when they doFeedback and coaching to direct reports can include direction to develop their ideas in writingMemos and other writing can be requested, circulated, and referred to in meetings and phone calls as central items for discussionMeetings can begin with “reading time” to emphasize that the context for discussions is best absorbed in document formUse a standard term for an internal piece of writing (such as memo, proposal, one-pager, article, or thesis doc)Decide on a standard template (such as a Google Doc or Notion page), default length (such as 1,000 words or 2 pages), and method of sharing (such as email or Slack) these internal documentsThe more encouragement and feedback, incentives and rewards, and practical tools and templates you can provide to your people, the likelier they are to sit down and compose their ideas in written form, and thus the more likely that knowledge will spread and make an impact.

By successfully creating a culture of writing within your team, not only will knowledge be shared far more fluidly and effectively, you will also be creating a healthier psychological environment where people believe in their ideas and are invited to find their voice and speak powerfully.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post Team Knowledge Management: How to Use PARA in Your Organization appeared first on Forte Labs.

February 24, 2023

The PARA Method: The Simple System for Organizing Your Digital Life in Seconds

Imagine for a moment the perfect organizational system.

A system that told you exactly where to put every piece of information in your life – every document, file, note, agenda, outline, and bit of research – and exactly where to find it when you needed it.

Such a system would need to be incredibly easy to set up, and even easier to maintain. After all, only the simplest, most effortless habits endure long term.

It would need to be both flexible, adapting to your needs in different seasons of your life, but also comprehensive, so you can use it in every one of the many places where you store information, such as your computer’s file system, a cloud storage platform (e.g., Dropbox or Google Drive), or a digital notetaking app.

But most of all, the ideal organizational system would be one that leads directly to tangible benefits in your career and life. It would dramatically accelerate you toward completing the projects and achieving the goals that are most important to you.

In other words, the ultimate system for organizing your life is one that is actionable.

Instead of putting more obstacles in your way, postponing the actions that will make a difference, it would pull those actions closer and make them easier to start and finish.

After more than a decade of personal experimentation, teaching thousands of students, and coaching world-class professionals, I’ve developed such a system.

It’s called PARA – a simple, comprehensive, yet extremely flexible system for organizing any type of digital information across any platform.

I promise you that it will not only bring order to your life, but equip you with a set of tools for skillfully mastering the flow of information to achieve anything you set your mind to.

4 Categories to Encompass Your Entire LifePARA is based on a simple observation: that there are only four categories that encompass all the information in your life.

You have projects you’re actively working on – short-term efforts (in your work or personal life) that you take on with a certain goal in mind. For example:

Complete webpage designBuy a new computerWrite research reportRenovate the bathroomFinish Spanish language courseSet up new living room furnitureYou have areas of responsibility – important parts of your work and life that require ongoing attention. These might include:

Work responsibilities such as Marketing, Human Resources, Product Management, Research and Development, Direct Reports, or EngineeringPersonal responsibilities such as Health, Finances, Kids, Writing, Car, or HomeThen you have resources on a range of topics you’re interested in and learning about, such as:

Graphic designPersonal productivityOrganic gardeningCoffeeModern architectureWeb designJapanese languageFrench literatureNotetakingBreathworkHabit formationPhotographyMarketing assetsFinally, you have archives, which include anything from the previous three categories that is no longer active, but you might want to save for future reference:

Projects you’ve completed or put on holdAreas that are no longer active or relevantResources that you’re no longer interested inAnd that’s it! Four top-level folders – Projects, Areas, Resources, and Archives – each containing a small number of subfolders dedicated to each active project, area of responsibility, resource, and archive in your life.

It may be difficult to believe that a complex, modern human life like yours can be reduced to just four categories. It may feel like you have far more to deal with than can fit into such a simple system.

But that is exactly the point: if your organizational system is as complex as your life, then the demands of maintaining it will end up robbing you of the time and energy you need to live that life.

The system you use to organize information has to be so simple that it frees up your attention, instead of taking more of it. Your system has to give you time, not take time.

The Key Principle – Organizing Information By Your Projects And GoalsMost of us first learned how to organize information in school. We were taught to categorize our class notes, handouts, and study material by academic subject, such as Math, History, or Chemistry.

But then without realizing it, we took that same approach into adulthood. We continued to categorize our documents and files according to incredibly broad subjects like “Marketing,” “Psychology,” “Business,” or “Ideas.”

This makes zero sense in your post-academic career. In the workplace, there are no classes, no tests, no grades, and no diplomas. No teacher is going to tell you what to write down for the final exam, because there isn’t one.

What you do have, both at work and in life, are outcomes you are trying to achieve. You are trying to launch a new product, plan a family vacation, come to a crucial decision, find daycare in your neighborhood, publish a new piece of writing, or reach a quarterly sales number.

In the midst of your busy day, as you are trying to make these things happen, you absolutely do not have time to go rummaging through a vast category like “Psychology” to find the one piece of information you need.

Instead of organizing information according to broad subjects like in school, I advise you to organize it according to the projects and goals you are committed to right now. This is what it means to “organize by actionability,” a mantra I will return to again and again throughout this book.

When you sit down to work on a graphic design project, for example, you will need all the notes, documents, assets, and other material related to that project all in one place and ready to go.

That might seem obvious, yet it is exactly the opposite of what most people do. Most people tend to spread out all the relevant material in a dozen different places that would take them half an hour just to locate.

How do you make sure that all the material related to each project or goal is all in one place? You organize it that way in the first place. That way you’ll know exactly where to put everything, and exactly where to find it.

The Power of Organizing By ProjectFor several years, I worked as a productivity coach in the San Francisco Bay Area. It was the peak of the tech boom, and high-powered professionals from some of the world’s most influential companies were looking for any edge in their performance. I was happy to oblige.

I coached several executives at a well-known biotech firm in South San Francisco, on a beautiful campus overlooking the bay. I remember one beautiful spring day I was waiting for my next client, a Senior Director in charge of developing several new life-saving pharmaceuticals.

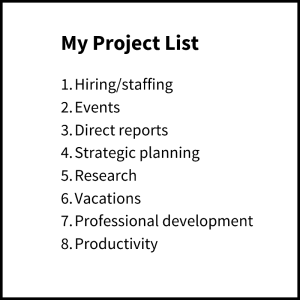

Once he arrived, our coaching session started like every other, with a simple question of mine: “Do you have a project list?”

When working with a client as a productivity coach, one of the first things I will always ask them is to show me their project list. I need it to get a sense of what kind of work they do, their current workload, and what priorities and outcomes they are trying to move forward.

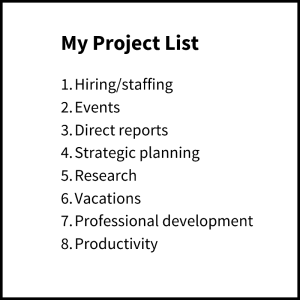

He said “Sure!” and, after jotting down a quick list from memory (the first warning sign), handed me a list like this:

Do you see the problem? Look again closely.

Not a single item on this list is a project, according to our earlier definition. Does “strategic planning” ever end for good? Is there ever a time when you can permanently cross off “vacations” from your list? Hopefully not!

Every item on this list is, in fact, an area of responsibility. This might seem like semantics, but it’s anything but. I’ve learned that no matter how smart or driven you are, there are two critical things you cannot do until you break down your areas of responsibility into specific projects.

1. You Can’t Truly Know the Extent of Your CommitmentsOne of the most common complaints I hear from people is that they “have no bandwidth.” And I sympathize – how much of the time does it feel like you have way too much on your plate?

But as long as you view your work through the lens of areas, you’ll never quite know just how much is on your plate. Looking at the list above, how much of a workload does “Hiring” represent? It could be anything from a part-time hire every 6 months to filling 50 positions this quarter.

There’s simply no way to know at a glance, and that uncertainty will manifest itself as every area feeling more burdensome than it really is.

Imagine if you identified each of the projects within Hiring, and kept that list in front of you every day. Wouldn’t it be so much easier to tell how much there is left to do, and what you should do next? For example:

2. You Can’t Connect Your Current Efforts to Your Long-Term Goals

2. You Can’t Connect Your Current Efforts to Your Long-Term GoalsOne of the most challenging (but also rewarding) aspects of knowledge work is that it requires our creativity. And creativity can’t really be sustained without a sense of motivation. You can’t keep doing your best thinking and contributing your best ideas if you’re burned out and demoralized.

What does our motivation depend on? Mostly, on making consistent progress. We can endure quite a bit of stress and frustration in the short term if we know it’s leading somewhere.

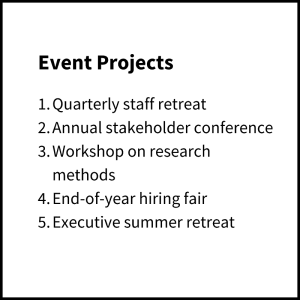

Which brings us to our second problem: without a list of individual projects, you can’t connect your current efforts to your long-term goals.

Look at the list above again. None of the items on it will end or change – that’s the definition of an area of responsibility, that it continues indefinitely. Now imagine the psychological effect of waking up week after week, month after month, and even year after year to the exact same list of never-ending responsibilities. No matter how hard you work, the endless horizon never seems to get any closer.

Honestly, I couldn’t design a better way to kill your motivation if I tried.

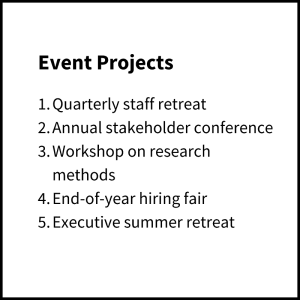

When you break down your responsibilities into bite-sized projects, you ensure that your project list is constantly turning over. This turnover creates a cadence of regular victories that you get to celebrate every time you successfully complete a project. Imagine how motivated and accomplished you’d feel by breaking out the broad area of “Events” into each individual event you’re running:

No matter how wide-ranging your responsibilities are, you can always break them down into smaller projects. And you must, if you want to know whether you’re actually making progress toward your goals.

Getting Organized For the Life You Want to LeadUsing PARA is not just about creating a bunch of folders to put things in.

It is about identifying the structure of your work and life—what you are committed to, what you want to change, and where you want to go. It is about organizing information in such a way that it supports and calls into being the future life you want to lead.

So much of what we call “organizing” is essentially procrastination in disguise. We tell ourselves we’re “getting ready” or “doing research,” pretending like it’s progress. When in reality, we are seeking any little thing we can polish or tidy to avoid having to face the task we are dreading.

PARA cuts through this facade, giving us a method for organizing anything that is so radically simple, there is no excuse and nothing left to do except the next essential step. It is a minimalistic way to add just enough order to your environment that you have the clarity to move forward, and no more.

There are other more complex, sophisticated, and specialized ways of organizing information out there, but PARA is the only one that stands the test of time because it gives you more time than it takes.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post The PARA Method: The Simple System for Organizing Your Digital Life in Seconds appeared first on Forte Labs.

The PARA Method: A Universal System for Organizing Digital Information

Imagine for a moment the perfect organizational system.

A system that told you exactly where to put every piece of information in your life – every document, file, note, agenda, outline, and bit of research – and exactly where to find it when you needed it.

Such a system would need to be incredibly easy to set up, and even easier to maintain. After all, only the simplest, most effortless habits endure long term.

It would need to be both flexible, adapting to your needs in different seasons of your life, but also comprehensive, so you can use it in every one of the many places where you store information, such as your computer’s file system, a cloud storage platform (e.g., Dropbox or Google Drive), or a digital notetaking app.

But most of all, the ideal organizational system would be one that leads directly to tangible benefits in your career and life. It would dramatically accelerate you toward completing the projects and achieving the goals that are most important to you.

In other words, the ultimate system for organizing your life is one that is actionable.

Instead of putting more obstacles in your way, postponing the actions that will make a difference, it would pull those actions closer and make them easier to start and finish.

After more than a decade of personal experimentation, teaching thousands of students, and coaching world-class professionals, I’ve developed such a system.

It’s called PARA – a simple, comprehensive, yet extremely flexible system for organizing any type of digital information across any platform.

I promise you that it will not only bring order to your life, but equip you with a set of tools for skillfully mastering the flow of information to achieve anything you set your mind to.

4 Categories to Encompass Your Entire LifePARA is based on a simple observation: that there are only four categories that encompass all the information in your life.

You have projects you’re actively working on – short-term efforts (in your work or personal life) that you take on with a certain goal in mind. For example:

Complete webpage designBuy a new computerWrite research reportRenovate the bathroomFinish Spanish language courseSet up new living room furnitureYou have areas of responsibility – important parts of your work and life that require ongoing attention. These might include:

Work responsibilities such as Marketing, Human Resources, Product Management, Research and Development, Direct Reports, or EngineeringPersonal responsibilities such as Health, Finances, Kids, Writing, Car, or HomeThen you have resources on a range of topics you’re interested in and learning about, such as:

Graphic designPersonal productivityOrganic gardeningCoffeeModern architectureWeb designJapanese languageFrench literatureNotetakingBreathworkHabit formationPhotographyMarketing assetsFinally, you have archives, which include anything from the previous three categories that is no longer active, but you might want to save for future reference:

Projects you’ve completed or put on holdAreas that are no longer active or relevantResources that you’re no longer interested inAnd that’s it! Four top-level folders – Projects, Areas, Resources, and Archives – each containing a small number of subfolders dedicated to each active project, area of responsibility, resource, and archive in your life.

It may be difficult to believe that a complex, modern human life like yours can be reduced to just four categories. It may feel like you have far more to deal with than can fit into such a simple system.

But that is exactly the point: if your organizational system is as complex as your life, then the demands of maintaining it will end up robbing you of the time and energy you need to live that life.

The system you use to organize information has to be so simple that it frees up your attention, instead of taking more of it. Your system has to give you time, not take time.

The Key Principle – Organizing Information By Your Projects And GoalsMost of us first learned how to organize information in school. We were taught to categorize our class notes, handouts, and study material by academic subject, such as Math, History, or Chemistry.

But then without realizing it, we took that same approach into adulthood. We continued to categorize our documents and files according to incredibly broad subjects like “Marketing,” “Psychology,” “Business,” or “Ideas.”

This makes zero sense in your post-academic career. In the workplace, there are no classes, no tests, no grades, and no diplomas. No teacher is going to tell you what to write down for the final exam, because there isn’t one.

What you do have, both at work and in life, are outcomes you are trying to achieve. You are trying to launch a new product, plan a family vacation, come to a crucial decision, find daycare in your neighborhood, publish a new piece of writing, or reach a quarterly sales number.

In the midst of your busy day, as you are trying to make these things happen, you absolutely do not have time to go rummaging through a vast category like “Psychology” to find the one piece of information you need.

Instead of organizing information according to broad subjects like in school, I advise you to organize it according to the projects and goals you are committed to right now. This is what it means to “organize by actionability,” a mantra I will return to again and again throughout this book.

When you sit down to work on a graphic design project, for example, you will need all the notes, documents, assets, and other material related to that project all in one place and ready to go.

That might seem obvious, yet it is exactly the opposite of what most people do. Most people tend to spread out all the relevant material in a dozen different places that would take them half an hour just to locate.

How do you make sure that all the material related to each project or goal is all in one place? You organize it that way in the first place. That way you’ll know exactly where to put everything, and exactly where to find it.

The Power of Organizing By Project

For several years, I worked as a productivity coach in the San Francisco Bay Area. It was the peak of the tech boom, and high-powered professionals from some of the world’s most influential companies were looking for any edge in their performance. I was happy to oblige.

I coached several executives at a well-known biotech firm in South San Francisco, on a beautiful campus overlooking the bay. I remember one beautiful spring day I was waiting for my next client, a Senior Director in charge of developing several new life-saving pharmaceuticals.

Once he arrived, our coaching session started like every other, with a simple question of mine: “Do you have a project list?”

When working with a client as a productivity coach, one of the first things I will always ask them is to show me their project list. I need it to get a sense of what kind of work they do, their current workload, and what priorities and outcomes they are trying to move forward.

He said “Sure!” and, after jotting down a quick list from memory (the first warning sign), handed me a list like this:

Do you see the problem? Look again closely.

Not a single item on this list is a project, according to our earlier definition. Does “strategic planning” ever end for good? Is there ever a time when you can permanently cross off “vacations” from your list? Hopefully not!

Every item on this list is, in fact, an area of responsibility. This might seem like semantics, but it’s anything but. I’ve learned that no matter how smart or driven you are, there are two critical things you cannot do until you break down your areas of responsibility into specific projects.

1. You Can’t Truly Know the Extent of Your CommitmentsOne of the most common complaints I hear from people is that they “have no bandwidth.” And I sympathize – how much of the time does it feel like you have way too much on your plate?

But as long as you view your work through the lens of areas, you’ll never quite know just how much is on your plate. Looking at the list above, how much of a workload does “Hiring” represent? It could be anything from a part-time hire every 6 months to filling 50 positions this quarter.

There’s simply no way to know at a glance, and that uncertainty will manifest itself as every area feeling more burdensome than it really is.

Imagine if you identified each of the projects within Hiring, and kept that list in front of you every day. Wouldn’t it be so much easier to tell how much there is left to do, and what you should do next? For example:

2. You Can’t Connect Your Current Efforts to Your Long-Term Goals

2. You Can’t Connect Your Current Efforts to Your Long-Term GoalsOne of the most challenging (but also rewarding) aspects of knowledge work is that it requires our creativity. And creativity can’t really be sustained without a sense of motivation. You can’t keep doing your best thinking and contributing your best ideas if you’re burned out and demoralized.

What does our motivation depend on? Mostly, on making consistent progress. We can endure quite a bit of stress and frustration in the short term if we know it’s leading somewhere.

Which brings us to our second problem: without a list of individual projects, you can’t connect your current efforts to your long-term goals.

Look at the list above again. None of the items on it will end or change – that’s the definition of an area of responsibility, that it continues indefinitely. Now imagine the psychological effect of waking up week after week, month after month, and even year after year to the exact same list of never-ending responsibilities. No matter how hard you work, the endless horizon never seems to get any closer.

Honestly, I couldn’t design a better way to kill your motivation if I tried.

When you break down your responsibilities into bite-sized projects, you ensure that your project list is constantly turning over. This turnover creates a cadence of regular victories that you get to celebrate every time you successfully complete a project. Imagine how motivated and accomplished you’d feel by breaking out the broad area of “Events” into each individual event you’re running:

No matter how wide-ranging your responsibilities are, you can always break them down into smaller projects. And you must, if you want to know whether you’re actually making progress toward your goals.

Getting Organized For the Life You Want to LeadUsing PARA is not just about creating a bunch of folders to put things in.

It is about identifying the structure of your work and life—what you are committed to, what you want to change, and where you want to go. It is about organizing information in such a way that it supports and calls into being the future life you want to lead.

So much of what we call “organizing” is essentially procrastination in disguise. We tell ourselves we’re “getting ready” or “doing research,” pretending like it’s progress. When in reality, we are seeking any little thing we can polish or tidy to avoid having to face the task we are dreading.

PARA cuts through this facade, giving us a method for organizing anything that is so radically simple, there is no excuse and nothing left to do except the next essential step. It is a minimalistic way to add just enough order to your environment that you have the clarity to move forward, and no more.

There are other more complex, sophisticated, and specialized ways of organizing information out there, but PARA is the only one that stands the test of time because it gives you more time than it takes.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post The PARA Method: A Universal System for Organizing Digital Information appeared first on Forte Labs.

February 13, 2023

How We Saved $27,000 in Two Weeks: Cost-Cutting in a Creator-Led Business

Over the past few weeks, we completed our first rigorous cost-cutting exercise in the 10 years Forte Labs has been in business.

Cost-cutting is a strange subject to talk about as a creator-led business. We’re not supposed to worry about those pesky annoyances called “expenses” or “profitability.” We’re on the Internet, and the Internet is a wide-open frontier of endless possibility, right?

Right?!

But as 2022 came to a close, we began to see signs of a weakening online education sector after several years of white-hot growth. Whether it was expectations of a looming recession, punishing inflation, or a post-pandemic preference for in-person experiences versus online events, I don’t know.

What I do know is that people are more hesitant to take out their wallets and spend their money on online self-development programs than at any time since before the COVID pandemic. I decided to learn how other companies typically approached cost-cutting and to review our expenses in the new year.

The results?

We saved $27,764 in recurring annual expenses, equaling about 3% of our non-labor costs. More importantly, we questioned where our money is going and what we really need to serve our customers. That led to a more realistic understanding of which software platforms and services are essential for us.

Finally, we seem to have cultivated a mindset of frugality in our company culture that’s already reaping rewards as we’re faced with countless special offers and “must-have” purchases heading into the new year.

Read on to find out how we did it, and get a checklist you can use to perform a similar feat in your own company, organization, or life.

The mindset of profit-maximizationThe single most important thing I needed to do to cut costs effectively was to change my mindset toward money.

The last decade has been one of the strongest bull markets for online businesses ever, capped by two years of completely unprecedented, explosive growth. A decade of plenty instilled in me an attitude that it was so much easier and more fruitful to spend my time growing revenue rather than pinching pennies. It felt like we should spend money as fast as possible in order to make money even faster.

A mindset of abundance makes sense when the environment is one of abundance. But an environment of scarcity demands an attitude resilient to scarcity. In order to make a cultural shift within our company, I first needed to make that shift psychologically myself.

I asked Twitter how I could learn to become frugal, and picked up one of the recommended books, Double Your Profits in 6 Months Or Less (affiliate link) by Bob Fifer. The title sounded like a late-night infomercial, and the cover looked like it was from the 90s, which I soon discovered was accurate: the book was first published in 1993.

In Internet terms, an ancient relic.

As I opened its pages, the author’s writing reflected an old-school attitude to business that I barely recognized. He sounded like a survivor of the Great Depression, scrounging for every nickel and treating every cost as a personal offense.

But as I continued reading, Fifer slowly introduced me to a powerful framework for thinking about costs during uncertain economic times. Here are a few of the most important takeaways that I decided needed to become part of our culture:

Our driving goal as a company is to be THE BEST in our field, which means we must maximize profit, which is the “permission to keep going.” All other goals or objectives don’t matter if we’re not profitable.To maximize profit, we need to consistently ask “What is the customer willing to pay for?” and eliminate everything else.All costs can be divided into 1) Strategic costs (essential for generating revenue) and 2) Non-strategic costs (not essential for revenue). Our goal is to spend more on the former than any of our competitors and cut the latter to the bone.Keeping resources (human and monetary) purposefully scarce forces us to soul-search about which tasks and projects are truly value-producing.Always make the spending of money a difficult process so that people must jump through several hoops to prove its worthiness.Every cost should be treated as a necessary evil at best, and we should look for any possible way to eliminate it.When considering eliminating an expense, ask yourself, “If I eliminated this cost, would I immediately lose revenue or profits? How and where?”If in doubt, default to cutting a cost, and if a consequence emerges, you can always add it back (whereas leaving it in place means that money is gone forever).The hardest part of all of your cost-cutting initiatives will be the resistance to change you will encounter. People learn to treat every service as essential even when it’s not.As hard as this may be to believe, I had never really thought that the #1 job as a CEO is to maximize profit. With revenue doubling every year, and gross margins consistently above 60%, profitability seemed to more or less take care of itself. All that was left to do for us was to figure out how to spend it.

Which is why this quote rang so powerfully inside my head: “Full empowerment of an organization when you have not focused on profits is an abdication of your most basic responsibility as a leader.”

I could see with sudden, newfound clarity that nothing else we achieved – big product launches, huge audience growth, a bestselling book, prestigious media attention, or even an empowered team – meant anything if we weren’t profitable.

I was encountering a set of timeless, conservative business principles for the first time, and it all seemed new again.

Cost-cutting as a ritualWith my new mindset in place, I wanted to spring immediately into action and begin eliminating costs right, left, and center.

But I knew that cost-cutting wasn’t a one-time event – it was a repeatable ritual that we would need to do again and again indefinitely. I resolved to move slowly and purposefully instead, documenting every step we took, every question we asked, and every unnecessary expense we identified for future reference.

Here were the 9 main elements of the cost-cutting process I put in place:

Formed a Budget Committee made up of me, our Director of Operations, and Business Operations Manager, with a standing monthly meetingSet aside time for a year-end review of every single transaction over the last quarter, in order to identify candidates for cost reductionScheduled monthly reviews of every transaction going forward (to question whether it’s necessary, can be reduced, and to categorize it correctly)Reached out to our main suppliers, contractors, and service providers to proactively negotiate price reductions (or extend payables or other terms)Instituted a new policy that all new costs must be approved by me personallyReviewed employee benefits to decide which ones people truly value, cutting the restWrote an internal memo to all staff explaining what we were doing and why it was important to our goals as a companyAsked every person on our team to suggest ideas for expenses we could reduce or eliminateBroke down our financial statements into 4 departments – Product, Operations, Marketing/Content, and YouTube – with each Director responsible for controlling their own spendingI also shared with the team a set of questions we would be using to question how we had spent money in the past, partly drawn from the book and partly from my own experience:

What is the customer willing to pay for? What are they not?Which difficult, uncertain expenses are we avoiding to cut in favor of easy, clear reductions?How can we make the process of spending money more difficult?Where can I personally set an example of how much we value each dollar?How can we make our company more of a meritocracy, rewarding those who contribute directly to the bottom line?How can we create a profit-maximized customer, instead of just a happy one?How can we remove benefits that employees don’t value, in favor of the ones they do?How can we create an attractive offering for each major category of customer at a price they are willing to pay?Examining our credit card statements with a critical eye, I decided we needed to put as much thought into keeping money as we put into earning it in the first place.

How we reviewed every transactionOur newly formed Budget Committee kicked things off by reviewing each and every transaction in the last quarter of 2022.

Our goal was not only to come up with a list of specific expenses to eliminate but to create a baseline that future quarters could be compared to. We also took the time to make sure expenses were assigned to the correct department, so that future decisions about where to invest would be more accurate.

The prospect of reviewing each and every transaction for a quarter – over 700 in total – might seem daunting, but we developed a succinct set of questions to accelerate progress. Here were the questions we asked for each item:

“Is this expense truly necessary?”: If not, cancel it (and ask for a refund for any unused periods)If it is necessary, then ask: “How can this cost be reduced?”Can it be paused when not needed?Can it be downgraded to a cheaper plan or lower level of service?Can it be switched from monthly to annual billing (to save money) or from annual to monthly (if it’s only needed occasionally)?Can we negotiate a better price?If it still remains, then finish by asking: “Which department should this be assigned to?”Take notes on any follow-up actions needed (to find out more details about a service from the person who uses it, and share corrections with our bookkeepers so they can accurately categorize transactions in the future)As we walked through these questions, we were surprised by how many opportunities there were for cost reduction. We thought we ran a lean operation, but even for services that we couldn’t eliminate completely, there was often a more basic plan or smaller number of users that served our needs just fine.

Renegotiating rates with our suppliers and contractorsOur next task was to see how we could reduce how much we spent on suppliers, service providers, and contractors, which made up a significant chunk of our spending.

I found this can take many forms, and doesn’t have to be adversarial. People understood that we need to look out for our profitability and were often willing to work with us to keep us as a customer in uncertain economic times that they’re probably feeling themselves.

This part is ongoing and might include switching contractors from retainer to hourly billing (or vice-versa), asking them to add more value in lieu of reducing their rates, asking them to cover costs that are essential to their work (as is appropriate for contractors), requesting more favorable terms such as longer payable periods, seeking bulk discounts for suppliers we buy a lot from and other requests.

SaaS services were much easier to reduce since they often have extremely high margins of 70-90% and thus are willing to keep you at almost any cost. We found that in some cases simply asking for a discount was effective.

The key to all these conversations was for the negotiation to come directly from me, the CEO, since the staffperson who works most closely with a contractor is often on too friendly of terms to make such requests.

The results of our cost-cutting exerciseAt this point you’re probably wondering what we cut exactly. Here’s the full list, including full cancellations and partial reductions on an annual basis:

In addition to $26,510 in planned spending, we received $1,254 in refunds from some of the services above for unused periods. The grand total of $27,764 represents about 3% of our annual non-labor costs, and 1.3% of our total costs, a sizable chunk of recurring spending that meaningfully improves our profitability for the coming year and beyond.

More important than the numbers, however, is the psychological effect of working through this process as a team. To my surprise, I found it required tremendous creativity and imagination. It’s forcing us to learn how to hack together jerry-rigged solutions to problems instead of just buying something off the shelf. As a result, we’re discovering how adaptable and resilient we are, and how possible it is to do more with less.

If constraints are necessary for innovation, purposefully creating financial constraints around our spending has channeled our problem-solving ability and helped us prioritize what’s truly necessary from what isn’t. And through it all, we are finding new ways to rely on each other and hold each other accountable to protect the only number that proves we are creating value: profit.

If you want to know which software tools, apps, and services we continue using, click here. These are the ones we’ve found essential for running and growing our business.

The post How We Saved $27,000 in Two Weeks: Cost-Cutting in a Creator-Led Business appeared first on Forte Labs.

February 6, 2023

How I Used Amazon Reviews to Predict Sales of My Book

This research project started with a simple question that has crossed every author’s mind:

How can I tell which books are successful?

TV shows have Nielsen ratings, music albums have the Billboard Top 100, and movies regularly publicize their box office earnings, but not books. Bestseller lists like The New York Times are notoriously subjective, while more objective ones like Amazon and The Wall Street Journal only provide rankings, not raw numbers.

The most reliable sales figures in the publishing industry come from NPD BookScan, but a subscription to that service costs hundreds of thousands of dollars per year and is only accessible to people in the publishing industry. Academic research on BookScan is explicitly banned!

Now, why is it a problem that we don’t have access to reliable sales figures for books?

Without that information, authors don’t know who to look to as models. We don’t know if the seemingly meteoric rise of a book or author in the media is just hype, or if those books are actually flying off the shelves. As a result, we can’t learn what the most successful authors are doing right and thereby open the door for more authors to succeed.

That is, until now…

Using official sales figures from BookScan, publicly available data from Amazon, and some basic math, I’ve created a model for determining with a considerable degree of certainty which books are selling, to what extent they are selling, and the odds they are likely to continue selling in the future.

Here’s a summary of my findings:

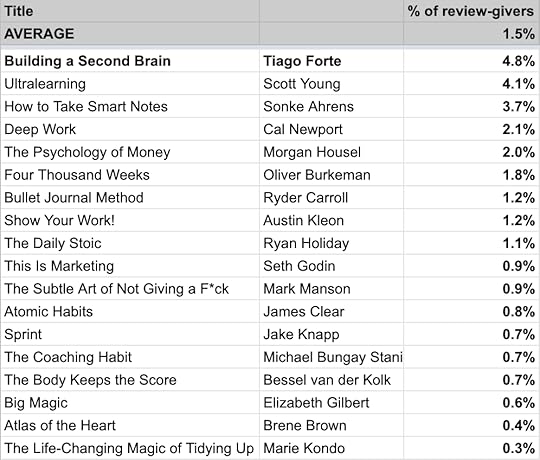

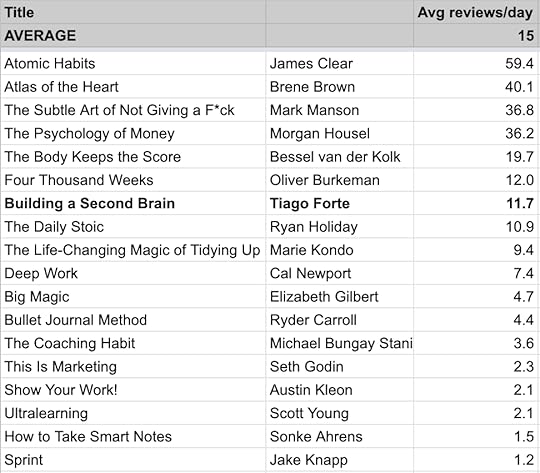

The total number of Amazon reviews a book has is an excellent indicator of its actual sales (88% correlation)A book rapidly receiving a large number of Amazon reviews upon release is a strong indicator of lifetime sales potential (65% correlation)A book’s average Amazon rating is a weaker predictor of sales (30% correlation), meaning that it doesn’t matter so much whether a review is positive or negativeThe average book in my sample received 15 reviews per day over its lifetime, on average 1.5% of book buyers left a review, and each review on average corresponds to $115 in salesMy book Building a Second Brain is accumulating 11.7 Amazon reviews per day on average – faster than 11 books in this sample, and slower than 6As more time passes since a book’s publication, its average rating drops slightly, and the number of reviews it receives per day drops substantiallyRead on for more detailed findings.

How can I tell if a book is selling well?I started by selecting 20 books (including my own for comparison) to study closely. Each of these books had to meet the following criteria:

Published no more than 10 years ago (5.2 years ago on average)Received at least 2,000 Amazon reviews (with an average of 23,000)Rated highly on Amazon (with ratings between 4.4 and 4.8 and an average of 4.6)I only chose books that I personally admired and felt had made a significant cultural impact, so that I’d be confident drawing lessons from them for myself.

Here are my subjects:

How to Take Smart Notes, by Sonke AhrensThe Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, by Marie KondoBuilding a Second Brain, by Tiago ForteUltralearning, Scott YoungSprint, by Jake KnappThis Is Marketing, Seth GodinFour Thousand Weeks, Oliver BurkemanThe Bullet Journal Method, by Ryder CarrollThe Coaching Habit, Michael Bungay StanierBig Magic, Elizabeth GilbertDeep Work, Cal NewportThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck, by Mark MansonShow Your Work!, by Austin KleonThe Psychology of Money, by Morgan HouselAtlas of the Heart, by Brene BrownThe Daily Stoic, by Ryan HolidayThe Body Keeps the Score, by Bessel van der KolkAtomic Habits, by James ClearI then looked up official BookScan sales figures for these books, via an industry contact. BookScan claims to measure about 80% of book sales, which doesn’t include ebook, audiobook, international, and certain retailer sales. However, since I have access to much more accurate and comprehensive data on sales of my own book, I was able to determine it’s actually far below that. I decided to apply a multiple to the BookScan sales figures to arrive at a more realistic “projected” sales volume for each book, which I then used in the rest of my analysis.

Each of the bestselling books I studied has sold 3.1 million books on average as of January 2023, ranging widely from 53,000 to 11.8 million copies. By cross-referencing these numbers with information from Amazon, I found the following correlations (ranging from -100% for a perfectly negative correlation, to +100% for a perfect positive correlation):

The total number of reviews positively correlates to total sales: 88%The average Amazon rating positively correlates to total sales: 30%The time since publication positively correlates to total sales: 29%In other words, a book’s total number of Amazon reviews is an excellent indicator of a book’s actual sales. This makes sense since Amazon is the dominant retailer of books today and the more people buy and read a book, the more of them will likely leave a rating or review. Thus, a book’s number of Amazon reviews can be used as a publicly available signal of how it’s selling, a useful rule of thumb for any aspiring author looking for models of success.

The average Amazon rating for a book also correlates with more sales, but much less so, which means that it doesn’t matter very much whether a review is positive or negative. Just the act of leaving a review signals that a book is selling well. There’s no such thing as bad publicity apparently. The number of days a book has been on the market also somewhat correlates with its sales since obviously, they have had more time to make sales.

So far, not much of a surprise: books with more Amazon reviews, higher ratings, and more time on the market sell better!

How can I tell if a new book will be successful long term?My next question was, “Are there any publicly available early signals that a book is going to be a long-term bestseller?”

While it’s useful to know whether a book published years ago has been successful, the lessons I can draw from it are limited. What worked well back then may no longer work well now. On the other hand, strategies that are working well for them now might not work for someone releasing a new book in today’s market. Lifetime sales aren’t enough – I needed to find a way to control for how long a book has been on the market.

To find the answers to these questions, I calculated the “average number of reviews per day” that each book on my list had received over its lifetime. In other words, at what rate did they receive reviews on average? I call this metric “review velocity.”

The review velocity represented a very widespread, from 1.2 reviews per day for Sprint, to 59.4 for Atomic Habits, with an average of 15 reviews received per day across all 20 books.

The reason review velocity is so helpful is that it allows me to compare the “trajectories” of books that were published at completely different times, including recently published books. I have no idea how a book’s reviews are distributed across time (Do a lot of them come in early when it gets released and then decline over time? Or do they start slow and pick up speed over time?), but working with averages allowed me to see the broad strokes.

When I compared “review velocity” with “sales to date” it produced quite a strong positive correlation of 65%. This means that a book’s review velocity isn’t as strong a predictor of sales as the total number of reviews, but a lot stronger than the average rating or time on the market. In other words, a book rapidly receiving a large number of Amazon reviews is a fairly strong indicator of lifetime sales potential.

I also noticed a lot of variation in the percentage of book buyers who left a review. It ranged from 0.3% for The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up to 4.8% for my book, with an average across all 20 books of 1.5%. I’m guessing this number starts high as hardcore fans leave reviews and then declines as the book spreads to more mainstream, less dedicated audiences. But it’s a good sign!

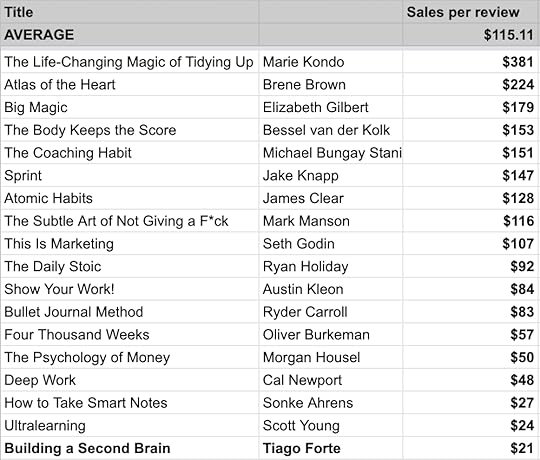

Sorting the list again by “sales per review” (How much in sales did a review correspond to on average?) produced the reverse of the list above: a range from $21 for my book to $381 for The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up (and an average of $115). Which implies that as a book becomes more popular it sells better, but receives fewer and fewer reviews as a percentage of sales.

How can I tell how successful my book will be?

How can I tell how successful my book will be?The next question I wanted to answer was personally motivated: Could I use these correlations to predict the future sales of my book Building a Second Brain?

More than 7 months after its release, while I know it’s doing well, I really have no idea how well. Sales numbers mean nothing on their own – what matters is what standard of success I’m comparing myself to. Without knowing how the book is doing in the grand scheme of things, I’m not really sure what to do next.

Is this a niche hit that will exhaust the early adopters and fizzle after a year or two? Or is it showing signs of potentially crossing over into a mainstream phenomenon? Is it on a path to becoming a career-defining mega-bestseller, like Getting Things Done, or is it more likely an introductory title that sets me up to write more impactful books later on?

By calculating what trajectory we’re on and what magnitude of sales we’re on track for, I can decide whether to change my marketing strategy, invest more resources (or less), or adjust my business model in response.

I sorted my spreadsheet by review velocity, with the following results:

My book comes in at 11.7 reviews per day since its release 7 months ago.

This indicates that it is probably selling faster on average than The Daily Stoic, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, Deep Work, Big Magic, The Bullet Journal Method, The Coaching Habit, This is Marketing, Show Your Work!, Ultraleaning, How to Take Smart Notes, and Sprint, but not as fast as Four Thousand Weeks, The Body Keeps the Score, The Psychology of Money, The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F***, Atlas of the Heart, and Atomic Habits.

Assuming that review velocity stays fairly constant over a book’s lifetime, this is very good news! I would be overjoyed to have the same financial results and cultural impact of any of these books, and I seem to be around the middle of the pack. My book also has the same average rating among this group of 4.6. Being average among such a crowd is a great honor.

If you would be so kind, especially given these findings, I would deeply appreciate if you left a review for my book here:

Leave a Review Other interesting correlationsWhile correlation doesn’t mean causation, here are other interesting relationships between metrics I discovered (along with my interpretations in parentheses):

Days on the market – No. of reviews: 17% (If books sold equally well over time, you’d expect this to be close to 1. This indicates that review velocity has increased a lot for more recently published books, versus older ones.)

Days on the market – Average rating: –11% (The longer a book has been out, the lower its rating drops, slightly.)

Days on the market – Reviews/day: –33% (The longer a book has been out, the more its review velocity slows down.

No. of reviews – Average rating: 44% (The more reviews a book has, the higher its average rating. This isn’t intuitive, as you would think more reviews from a broader audience would mean lower ratings over time as the hardcore fans get diluted. It suggests a kind of “bandwagon” effect of people leaving higher ratings just because a lot of people have left reviews.)

Average rating – Reviews/day: 58% (The faster a book accumulates reviews, the higher the average rating will be. This also suggests a bandwagon effect, as people leave higher ratings just because they see the number of reviews growing quickly, suggesting a lot of people are reading the book.)

If you or someone you know has further insights into these questions, please let me know!

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post How I Used Amazon Reviews to Predict Sales of My Book appeared first on Forte Labs.

January 23, 2023

A Single Creative Project Can Change the Trajectory of Your Life

It doesn’t have to be a huge project. It doesn’t have to be well-funded or prestigious or public. But it does have to draw something out of you so unexpected that it changes your conception of who you are.

The kind of creative project I’m talking about creates an unmistakable inflection point in your life. It changes your identity so much that you can never see yourself the same way again.

I recently read through years of my old journals for the first time ever, and five creative projects stood out as early inflection points in my life. Each one taught me an essential principle for how to purposefully choose life-changing projects. Each of these projects:

Were about serviceWere self-initiatedWere shared with othersProduced a tangible artifactAsked for something in returnTogether they make up a kind of “creative autobiography” that made me who I am today. Let’s take a closer look at each one to see how you can apply it for yourself.

Creative projects are about serviceThe foundation of my attitude toward creativity is that it is fundamentally a form of service to others.

I vividly remember traveling to Mexico for the first time at 10 years old on a volunteer trip with a group from our church. Before dawn on a Saturday morning, I climbed into my father’s red F-150 pickup truck, and together we drove two hours south to the border with a bed full of tools and supplies.

A community on the outskirts of Tijuana, similar to the one we visited

A community on the outskirts of Tijuana, similar to the one we visited We made our way to an impoverished community of ramshackle houses, built out of pieces of scrap and plywood, on the outskirts of Tijuana. We had brought lumber to erect a series of simple wood-frame houses for families who lacked adequate shelter.

At 10 years old I couldn’t help much with the construction, so my responsibility was to ferry around hammers and nails, water and snacks. I worked tirelessly, stretching my inventiveness to its limit in search of any small skill I could offer or any meager resource I could give. Something as simple as playing with a 4-year-old so his parents could make a meal for the work crews proved that I could make a difference.

This might not seem like a typical creative project, but it demanded profound imagination from me. Only a short car ride from the wealthy suburbs of Orange County where we lived, I had stepped into a starkly different reality. I found myself face to face with the hungry eyes of children living in a kind of squalor my mind could barely comprehend. Everything I thought I knew about fairness, justice, and privilege was thrown into doubt.

This early experience shaped my understanding of creativity as a gift that is meant to be given away. I came to believe that if I had a skill, a resource, or a piece of knowledge that could alleviate someone’s suffering, I had the responsibility to offer it to them.

From that point on, I could never tell myself that I wasn’t ready, didn’t know or have enough, or needed to satisfy my own needs before I could afford to contribute. I had made a difference for someone when I was only 10 years old! For the rest of my life I’ve carried that value of service with me – to give even when I don’t feel ready, even when I’m afraid, and even when I don’t know exactly what I have to offer.

I see so many artists, writers, and other creatives getting wrapped up in their own perfectionism and preciousness. They seem to believe if they can just understand and analyze their own psychology well enough, the obstacles to their self-expression will disappear. But the mind can throw up psychological barriers far faster than you can tear them down.

The only reliable way out of my creative blocks is not to endlessly dissect them – it is to transcend my own fears and insecurities by making myself useful to someone with greater needs than mine. By the time I return to my own problems, they always seem so minuscule in comparison.

Creative projects are self-initiatedThe second key milestone in my creative autobiography was to commit to projects that were self-initiated: I chose to take them on of my own free will, and not because of any external obligation.