Tiago Forte's Blog, page 10

October 24, 2022

How to Thrive in a World of Uncertainty

The future has become so uncertain that goals are now obsolete.

The stable, predictable world we grew up in is gone. The idea that you can make a “5-year plan” and execute it one step at a time is laughable. No one knows what’s going to happen in the next 5 years or even the next 5 weeks.

Goal-setting was once central to our conception of what it means to navigate the future successfully. But goals can no longer serve as guides to an unfolding future that we have so little control over.

But this doesn’t mean that we have to throw up our hands in defeat. It doesn’t mean there’s nothing we can do to influence our fate. It just requires us to make a shift from leading with goals to leading with questions.

Replacing goals with open questionsQuestions shine a light toward the future – but more like a lantern than a focused beam.

They illuminate a space of possibilities where many avenues can open up, not just a single narrow path. Goals lead with certainty toward a predetermined outcome, taking the future for granted. While questions lead with doubt into the unknown, acknowledging the inherent uncertainty of everything that is yet to come.

Questions ask you to start with what you don’t know but would like to discover. They draw in others to pitch in and make their own contributions. They serve as open invitations to collaborative projects, versus the solitary path of individualistic achievement envisioned by goals.

In a world of uncertainty, questions are more powerful than answers. Answers serve you for a season, but a question lasts forever. Let’s revisit Richard Feynman’s story to discover the principles he used to navigate the uncertainty he faced effectively and even joyfully.

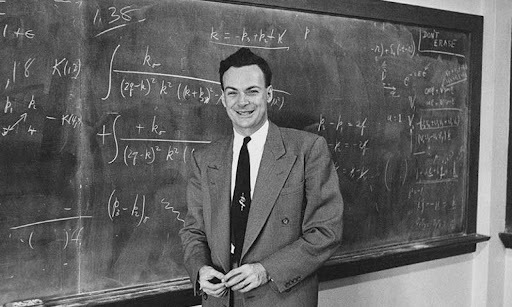

3 principles for navigating uncertaintyRichard Feynman rose to prominence during a 20th century which saw enormous advances in science, but also a destabilizing plunge into uncertainty that foreshadowed our own time.

The famous Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle rocked physics when it was introduced in 1927. Formulated by German Nobel laureate Werner Heisenberg, the principle stated that it is impossible to know with accuracy both the position and the momentum of a particle, no matter how much is known about its initial conditions.

This introduced a fundamental amount of uncertainty into physics, which up until that point had been on a ceaseless march to ever-greater levels of precision. It defined for the first time a frontier of knowledge that it seemed we would never be able to cross.

Feynman was part of the first generation of physicists to grow up in this “era of uncertainty,” and one of his chief contributions was developing an approach to scientific knowledge that worked despite such ambiguity.

His philosophy relied on three pillars:

The value of ignoranceThe value of transparencyThe value of a change in perspective

1. The value of ignorance

Feynman loved knowledge, but that doesn’t mean he hated ignorance.

As his biographer James Gleick notes, he seemed to “hoard shallow pools of ignorance, seemed to protect himself from the light like a waking man who closes his eyes to preserve a fleeting image left over from a dream.”

He famously refused to read the academic literature of his predecessors or contemporaries, preferring to work problems out for himself to see if he could find a simpler, more elegant solution (which he often did). He chided his graduate students who began their research by studying what had already been discovered. He believed that by doing so, they were giving up their chance of finding something original.

He said later: “Maybe that’s why young people make success. They don’t know enough. Because when you know enough it’s obvious that every idea that you have is no good.”

Feynman believed in doubt, not as a blemish on our ability to know, but as the essence of knowing. The only alternative to doubt was to blindly trust in an external authority, which science had fought against for centuries. He believed that it was not certainty but freedom from certainty that empowered people to act even when they didn’t have all the necessary information.

Toward the end of his life, he encapsulated his attitude in an interview:

“You see, one thing is, I can live with doubt and uncertainty and not knowing. I think it’s much more interesting to live not knowing than to have answers which might be wrong . I have approximate answers and possible beliefs and different degrees of certainty about different things, but I’m not absolutely sure of anything and there are many things I don’t know anything about, such as whether it means anything to ask why we’re here…. I don’t have to know an answer. I don’t feel frightened by not knowing things, by being lost in a mysterious universe without any purpose , which is the way it really is as far as I can tell. It doesn’t frighten me.”

2. The value of transparencyFeynman’s second principle for dealing with uncertainty was a deep commitment to radical transparency.

In a competitive academic world in which a discovery might lead to prizes, fame, and riches, the honest pursuit of truth sometimes takes a back seat. Then and now, scientists can be tempted to race to publish first, criticize each others’ results, or zealously guard resources and equipment.

It seemed to Feynman that scientific integrity required not just honesty, but an extreme form of honesty that included effort. In his book Surely You’re Joking Mr. Feynman! (affiliate link), he describes it as a “leaning over backward” to purposefully expose your hidden assumptions and potential mistakes.

For example, when conducting experiments, he advised reporting not only on everything that went as planned, but also anything that could be invalid or misunderstood. Details that could throw doubt on your interpretations must be given, so that an independent observer can decide for themselves the value of your contribution. And his highest test of all: a theory should be able to explain something that you didn’t even set out to explain, not just your original hypothesis.

Feynman’s commitment to this level of utter honesty can be summarized in perhaps his most famous quote: “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself– and you are the easiest person to fool.”

3. The value of a change in perspectiveBoth ignorance and transparency set the stage for the third principle in Feynman’s worldview: the importance of seeing things from a new perspective.

The most concrete example of this view was his extensive foreign travel. At a time when overseas trips were not nearly as common, he spent months at a time exploring Latin America and Asia on both work trips and personal vacations.

In Brazil, one of his favorite places, he became fond of the musical style known as samba and even joined a local samba school. There, he mastered an instrument known as the frigideira, a metal plate emitting a light, fast tinkle, well enough to perform in street parades and paid private gigs.

In Rio de Janeiro in the summer of 1949, Feynman was invited to teach physics as a visiting lecturer at the newly established Brazilian Center for Research in Physics. He often expressed his appreciation for what the art of teaching taught him:

“The questions of the students are often the source of new research. They often ask profound questions that I’ve thought about at times and then given up on, so to speak, for a while. It wouldn’t do me any harm to think about them again and see if I can go any further now.”

His students gave him a fresh perspective from the point of view of a novice, which he cherished throughout his life. He once said: “There is a pleasure in recognizing old things from a new point of view. Also, there are problems for which the new point of view offers a distinct advantage.”

The ultimate “beginner’s mind” is that of a child, and Feynman consciously cultivated an innocent, childlike way of viewing the world. He said, “Children and scientists share an outlook on life. If I do this, what will happen?… Every child is observer, analyst, and taxonomist, building a mental life through a sequence of intellectual revolutions, constructing theories and promptly shedding them when they no longer fit. The unfamiliar and the strange—these are the domain of all children and scientists.”

As our own time becomes more ambiguous and our future more uncertain, we can learn powerful lessons from Feynman about what it looks like to thrive in a world we don’t fully understand.

We can value our ignorance in questioning old assumptions, communicate with transparency to invite others to correct our mistakes, and purposefully take a chance on changing our perspective when the problems we are facing seem to have no solution.

The question of living a full lifeLooking at the totality of Richard Feynman’s life, what stands out to me the most is not his scientific achievements. There have been many equally brilliant scientists through the ages.

What strikes me is that he also lived a full, rich, well-rounded life. He didn’t limit himself to excellence in just one arena or force himself to fit into a particular mold. He traveled, made music, raised a tight-knit family, formed many close friendships, and contributed to important causes, always pursuing what fired his imagination regardless of whether it was popular.

For me, this is the heart of a question-oriented approach to life: the decision to remain fundamentally open to the full range of experiences that life has to offer. To express your values and dreams without fear, trusting that the universe is inherently full of possibilities more wondrous than you can possibly imagine.

In Part 6, I’ll share examples of favorite problems you can borrow or use as templates for your own curiosity.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post How to Thrive in a World of Uncertainty appeared first on Forte Labs.

October 18, 2022

How To Build A Second Brain | Anthony Pompliano

It was a pleasure to sit down with Pomp to chat about all things Second Brain.

We dove deep into a host of topics, including:

Are we consuming too much?How many hours do I read a day?How to create projects from your notesWhy removing risk from your life is wrongDo our team members have a company Second Brain?And much much more…Watch the full interview on YouTube here:

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post How To Build A Second Brain | Anthony Pompliano appeared first on Forte Labs.

October 17, 2022

How Favorite Problems Evolve: A Case Study

Your favorite problems will likely stay consistent over many years, but that doesn’t mean they can’t evolve.

I’ve found that in most cases I never actually arrive at a final, definitive answer to a question. Instead, the question changes as I learn more.

Let me illustrate this with a case study. I’ll show you how one of my favorite problems – teaching – changed over time as my life went through different stages.

The 15-year evolution of my favorite problemWhen I first started teaching English as a volunteer at my local community college in Orange County, California, my open question was very specific to the challenge at hand: “How do I teach English to recent immigrants who have no background in the language?”

That question led me to seek out specialized learning resources that used images and games to bridge the gap from their native language to English.

I soon fell in love with teaching, and when I moved overseas to study abroad in Brazil during my senior year of college, I started a side job teaching English at a small private school in Curitiba where I lived.

My open question changed a little: “How do I most effectively teach English to working professionals who are tired after work and only have an hour of instruction per week?”

Notice how this question introduced the element of effectiveness for the first time. This was now a job, and I had to think about how my work would be evaluated. Not only that, but I was charged with making a difference for my students in only one session per week, forcing me to come up with easy ways to help them practice speaking throughout the rest of the week.

A couple years later, I joined the Peace Corps, a U.S. government program that sends American volunteers to serve abroad. I found myself stationed in a small town in Eastern Ukraine, the lone American for many miles around, and responsible for about 8 classes of students ranging from 3rd to 11th grade.

My question suddenly became “How do I keep Ukrainian students of all ages engaged and interested in English?” I looked for ways to use games, role play, and improv activities to make learning English an interactive, and even fun, experience.

For example, we painted a large map of the world on a classroom wall, labeling each country in English. We made up adventure stories, narrated, of course, in English. I showed them pictures from my life in the U.S. and asked them to point out words they knew.

When I returned to the U.S. after two years of service, I wanted teaching to remain a part of my life. And after two years working in consulting, I decided to try teaching online as a freelancer. Once again, my attitude toward teaching had to adapt in line with my changing life.

My new question became “What do I know how to teach that could become a profitable business?” I had to think about the economics of teaching for the first time, which eventually led me to a model of “cohort-based” courses that combined online content with live interaction on Zoom.

As that business has grown and evolved, my question has continued to change. I’m no longer directly responsible for most aspects of our programs. I don’t make most decisions, don’t answer most questions, and am not in direct contact with students most of the time. My job is instead to build the team that does all those things, and to keep them productive and happy.

My questions these days include:How can I design an effective online learning community that sustains itself?How do I build and maintain a high-performing remote team to run the best training program on personal knowledge management in the world?How do I use free content on our blog, YouTube channel, and social media platforms to serve people even if they never take our course, but prepare them better for the course if they do?What new formats, mediums, and platforms can we use to reach more people more effectively with the Second Brain message, without overtaxing our resources or bandwidth?What kind of company are we? Are we a media company, a professional development company, a tech-enabled services firm, or something else? What should our model of success be?How do we make our community bottom-up instead of top-down? How can we enable others to unlock their potential using our community as a platform?How can I be the kind of leader and manager that inspires people to greatness without me needing to be there?These questions have led me to such unexpected places. In pursuit of answers, I’ve unexpectedly found myself learning the art of recruiting, figuring out how to structure an organization, designing salary ranges and benefits, and spending time doing financial planning, among many others.

These are topics I never imagined would have anything to do with teaching. And yet they are the natural consequence of an underlying, insistent question that has been with me for as long as I can remember: “How can teaching change people’s lives?”

Your favorite problems are always a “draft”As you formulate your own favorite problems, keep in mind that they are always just a first draft. They can and will evolve as you uncover deeper and more subtle layers of your initial curiosities.

Not only should you be open to this change, it is the entire point of this exercise: to immerse yourself in the inherent uncertainty that comes with asking questions with an open mind, and embracing the unknowns that will inevitably come into your life as a result.

The information you consume is ultimately a result of the questions you are trying to answer. Change the question, and you’ll begin to notice entirely new kinds of answers you never imagined existed.

The quality of your life depends on the quality of the questions you ask. Ask wisely.

In Part 5, I’ll revisit Feynman’s life and work one last time for a look into the heart of how he viewed the world – as a place of fundamental uncertainty – and the principles he used to navigate that uncertainty effectively and even joyfully.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post How Favorite Problems Evolve: A Case Study appeared first on Forte Labs.

October 10, 2022

Amplify Your Thinking Ability With Open Questions

Writing down your open questions is an act of “externalization” – you are taking passing curiosities and interests from your mind and externalizing them into the outside world.

That is a first step to making those questions active generators of possibility in your life, but certainly not the last. Once they exist in written form, such as in your notes, you now have a place to begin collecting potential answers to those questions without having to memorize them.

A question is like a radio signal broadcast out into space. It’s only natural that you’ll want to record any replies that come back.

Let’s revisit Richard Feynman’s story and see how he did exactly that.

Working from first principlesRichard Feynman was famous for always working “from first principles.”

He always started with the most basic facts, asked the most seemingly obvious questions, and let no assumption pass by untested. Rather than blindly accepting the wisdom of outside authorities, he drilled down to the most fundamental principles he could find and built up his own understanding from there.

This often led people to underestimate him, thinking he was slow to understand the problem at hand. As he recounted in his book Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! (affiliate link) (emphasis mine):

“Some people think in the beginning that I’m kind of slow and I don’t understand the problem, because I ask a lot of these “dumb” questions : “Is a cathode plus or minus? Is an an-ion this way, or that way?”

But later, when the guy’s in the middle of a bunch of equations, he’ll say something and I’ll say, “Wait a minute! There’s an error! That can’t be right!” The guy looks at his equations, and sure enough, after a while, he finds the mistake and wonders, “ How the hell did this guy, who hardly understood at the beginning, find that mistake in the mess of all these equations? ”

He was willing to appear “dumb” and ask questions that everyone else was afraid of asking, in order to arrive at answers no one else was capable of finding.

For Feynman, knowledge did not just describe. It acted and accomplished. It was a pragmatic tool for predicting and shaping reality. For that reason, he wasn’t content to learn the names of things or abstract explanations of how they worked. He believed that it was only through empirical trial and error that the truth could be distilled from mere conjecture.

Extending the mindIn her excellent book The Extended Mind (affiliate link), author Annie Murphy Paul introduces an exciting new field called “extended cognition.”

Based on extensive academic research, she makes a compelling case that human thinking doesn’t end at the boundaries of our skulls. Instead, our brains are just one part of a greater system of cognition that transcends our purely mental abilities.

Paul argues that there are three main ways humans extend their thinking capabilities in this way:

Thinking with the bodyThinking with the environmentThinking with other peopleDecades before extended cognition was even recognized as a field of study, Feynman used all three of these mechanisms to amplify his intellectual and creative powers. Even such a formidable mind as his relied heavily on outside sources of intelligence to achieve his intellectual heights.

Thinking with the bodyFeynman was known for his physicality, perhaps surprising for a theoretical physicist.

Feynman’s biographer James Gleick noted that “Those who watched Feynman in moments of intense concentration came away with a strong, even disturbing sense of the physicality of the process, as though his brain did not stop with the gray matter but extended through every muscle in his body.”

He would often be seen tapping rhythmically with his fingers on tabletops or other objects, gesticulating wildly as he talked, or using props to communicate ideas.

Feynman often described how he used visualization to put himself in nature: in an imagined beam of light, in a relativistic electron. Once he could see things from an electron’s point of view, new possibilities suddenly opened up to him.

The mathematical symbols he used every day had become entangled with his physical sensations of motion, pressure, and acceleration to the point that he “saw” physics in living color and “felt” the motions of particles as bodily sensations.

Gleick recounts a remark by a colleague of Feynman’s flabbergasted by his ability to make unexplainable intuitive leaps:

He suspected that when Feynman wanted to know what an electron would do under given circumstances he merely asked himself, “If I were an electron, what would I do?”

The colleague was joking, but his explanation was more accurate than he realized.

Thinking with the environmentFeynman’s commitment to testing ideas through direct interaction with the physical world extended to the tools he used to do so, especially his notes.

Gleick tells the story of how Feynman prepared for his oral qualifying examination to graduate from MIT. In typical fashion, he refused to read the standard papers of his field – he didn’t want his perspective to be colored by what other physicists thought was possible (or impossible).

Instead, he opened up a fresh notebook, turned to the first page, and wrote: Notebook of Things I Don’t Know About. For the first time (but not the last), he began to reorganize his knowledge of physics on the page. He worked for weeks disassembling each branch of physics he thought he understood, before putting it all back together and looking for raw edges and inconsistencies.

He took apart ideas on the page like a mechanic takes apart an engine – refusing to trust that anything fit without trying it out himself. His notebooks were like free-form canvases one might find in an artist’s studio, containing (according to his biography) “not just the principles of these subjects but also extensive tables of trigonometric functions and integrals—not copied but calculated, often by original techniques that he devised for the purpose.”

Much later in life, Feynman was interviewed at his home by the historian Charles Weiner, who was considering writing an official biography of the man. They were discussing Feynman’s attitude toward his notes, and Weiner casually observed that they represented “a record of the day-to-day work.”

Feynman sharply disagreed (emphasis mine):

“I actually did the work on the paper,” Feynman countered.

“Well,” Weiner said, “the work was done in your head, but the record of it is still here.”

“No, it’s not a record, not really. It’s working. You have to work on paper, and this is the paper . Okay?”

This distinction may seem small but was a crucial one for him: Feynman didn’t do the thinking in his head, only to record it afterward in his notebooks. The interaction between his mind and his notes constituted his thinking. Together they formed an integrated system of cognition criss-crossing the boundaries between flesh and paper.

A page from one of Feynman's notebooks from his youth, when he learned calculus from a textbook by copying and solving equations since his high school didn't offer calculus classes Thinking with others

A page from one of Feynman's notebooks from his youth, when he learned calculus from a textbook by copying and solving equations since his high school didn't offer calculus classes Thinking with othersFeynman was known as a singular genius, but that doesn’t mean he worked in isolation. He relied heavily on connection and collaboration with other leading minds of his era, both within and outside of physics.

His Nobel Prize in 1965 was shared with two other collaborators, Julian Schwinger and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga, each of whom contributed critical insights to the emerging understanding of quantum physics. He learned from mentors like Hans Bethe, a German-American theoretical physicist who was a major influence in teaching him how to understand physics from first principles.

Even beyond his professional life, his family and friends shaped him into a far more well-rounded, empathetic person than he was naturally inclined to be. Feynman recalled fondly how his mother taught him that “the highest forms of understanding we can achieve are laughter and human compassion.” His high school sweetheart and first wife Arline taught him to not take himself too seriously by teasing him about his pride and ego.

Feynman’s numerous and deep collaborations point to one of the most profound side effects of seeing the world through open questions: they will inevitably bring into your life people who share the same questions.

The purpose of generating your list isn’t just to clarify your own pursuits. Once you have this list in hand, it can serve as an invitation to the people you want to attract into your life – whether as friends, romantic partners, collaborators, colleagues, supporters, or investors.

When you are clear on the questions you are immersing yourself in, it makes it much easier for others to identify what kind of person you are and what you are trying to create in the world. When others can see what you’re trying to accomplish, it becomes far easier for them to help you do so.

A leader is not someone who relentlessly advances their own opinion through the opposition of others. A leader is someone who insistently asks a big question, again and again, creating a space of possibility into which others can pour their own contributions.

A close relative of Feynman’s favorite problems is a discipline known as Appreciative Inquiry. It involves asking questions not as a form of criticism, but (as the Wikipedia article above puts it) “to stimulate new ideas, stories and images that generate new possibilities for action.”

The article goes on: “Questions are never neutral, they are fateful, and social systems move in the direction of the questions they most persistently and passionately discuss.” And on an even grander scale: “Human systems are forever projecting ahead of themselves a horizon of expectation that brings the future powerfully into the present as a mobilizing agent.”

In other words, our future unfolds as a result of the questions we ask ourselves in the present. As long as those questions are externalized and made concrete in the world beyond our heads.

In Part 4, I will present a case study of how I used an evolving set of open questions to guide my career through years of uncertainty, ultimately leading to finding a calling that uniquely aligned with my deepest curiosities and passions.

A big thank you to Chris Winterhoff, Diana, Eric Colby, Julia Saxena, and Marla Maestre Meyer for their feedback and suggestions on this piece.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post Amplify Your Thinking Ability With Open Questions appeared first on Forte Labs.

October 4, 2022

How to Generate Your Own Favorite Problems: A 4-Step Guide

In this step-by-step guide, I’ll share the exact process I use for myself and my students to formulate the most powerful open-ended questions possible.

In Part 1, I introduced “favorite problems” as a lens through which to filter the immense amount of information we are exposed to every day. A favorite problem is an open-ended question you use to prime your subconscious to notice potential answers in the information you’re consuming.

Each question serves multiple purposes:

Giving you a filter for deciding which information you’re consuming now helps move forward your long-term goalsFocusing your reading and learning where it has the highest chance of making a differenceReminding you of which interests captivated your attention in the past and may be worth revisitingBut these benefits can only be realized when you make a concrete list of open questions in a trusted place outside your head. You need a list you can revisit, revise, and reflect on without having to wrack your memory. Your digital notes are the perfect home for such a list.

Here’s my current list of favorite problems as an example:

How can I design an effective online learning community that sustains itself?How can I translate principles from the Theory of Constraints to modern knowledge work?How can I cook healthy meals for my family every day that don’t take too much time and also taste good?How can I exercise joyfully every day?What would the ultimate corporate offering for our Building a Second Brain program look like?How can I build a bootstrapped company that serves people around the world while still preserving my free time and peace of mind?How can we create the world’s best free library of content on digital notetaking on YouTube in a way that is financially sustainable?How can information science be used to enable people’s personal growth?How can I teach timeless values and principles to my kids when my own are always evolving?Where in the world do we want to live (and for how long) to inspire a sense of adventure and novelty while also providing stability and lasting friendships for our kids?How do I support and contribute to the people I care about without interfering in their own learning and growth?What is the right structure for our company to give everyone freedom and balance while also provoking personal growth and progress?Notice that these are hard problems without simple answers. The truth is, they aren’t even necessarily designed to be definitively answered.

The value of questions comes from provoking your thinking at deeper and subtler levels, not finding a single “correct” answer. You may even arrive at different answers to the same question in different seasons of your life, depending on what you’re going through and what’s important to you at that time.

Open questions are “serendipity engines” – active generators of possibility to fuel your learning and growth over many months and years.

Here’s my 4-step guide to formulating your own favorite problems. I suggest setting aside a few minutes to make a first pass at your own list using the prompts below, keeping in mind you can always go back and revise them later.

1. Get started with these promptsHere are some prompts to help you get started identifying your own favorite problems:

What were you obsessed with as a child or teenager? (Ask your parents or caregivers)What are the longest running hobbies you’ve had in your life?What common themes or patterns do you notice emerging in your life repeatedly?What kinds of stories, art, or music give you goosebumps, make your hair stand up, or move you to tears?What pursuits that others consider challenging do you find fun and engaging?What do you find your mind wandering to in the in-between moments of your day?If you could wave a magic wand and have the ultimate answer to any question, what question would it be?If you could travel to the future and ask your future self anything, what would it be? What would you ask your past self?If you read all the books and took all the courses you wanted to, what question would you like to have answered after all that?What are your most pressing problems currently?2. Formulate your own “How/What” questionsOnce you have an idea of your long-term interests, I recommend phrasing them as questions that begin with “How…” and “What…” Such questions can’t be answered with a simple yes or no – they invite more subtle, complex answers based on deeper reflection:

How can I…?How might we…?How can my team/organization…?How can I help others to…?How does X relate to Y?How do I…?What does it look like to…?What would be possible if…?What do I want with…?What would I do if…?What would happen if…?What would have to be true to…?Once you’ve made a first draft of your list, save it in your notes (my recommendation is a digital notetaking system, which I call a “Second Brain”). That way they will appear in your searches, can be linked to and tagged with related ideas, and you’ll always be free to edit and change them as your interests evolve.

3. Make your questions specific, counter-intuitive, or cross-disciplinaryHere are some guidelines to help you come up with the most direct, impactful questions possible:

Make them specificMake them counter-intuitiveMake them cross-disciplinaryMake them specificOpen questions are often profound and a little mysterious, but that doesn’t mean that they can’t be specific as well. The best questions are ones that focus your problem-solving and spur you into action.

For example, instead of “How can I be a better leader?” which is a little broad, try “How can I be a better leader as an introvert?” See how that second version puts a fine point on the question, while also creating constraints to guide your thinking?

Don’t be afraid to make the question completely unique to you and your circumstances – in fact that is the entire point!

Make them counter-intuitiveThe best open questions have an element of surprise – they grab your attention and refuse to let go. Try to include something counterintuitive, unexpected, or paradoxical within the question.

For example, instead of “How can I improve the standard of living in the global south?” try “How can I improve the standard of living in the global south without further contributing to the climate change that threatens those regions the most?” Such a question has a tension between two important but potentially opposing forces, which will force you to come up with more creative solutions.

Asking a question is an art form, and like any art form, there should be a bold element of surprise hidden within.

Make them cross-disciplinaryOpen questions don’t have to be contained within one field, industry, or subject. At their best, they cross the usual boundaries between categories to spark unorthodox connections that no one else is likely to look for.

For example, instead of “How can I improve education?” you could ask “How can I improve education by borrowing ideas from video games?”

With such a framing, you are laying down tracks for your mind to follow. You are purposefully biasing yourself toward certain kinds of answers while drastically reducing the number of options you have to consider.

4. Start capturing information relevant to your favorite problemsYour favorite problems are a powerful complement to digital notetaking, because they tell you what you should be capturing in the first place, i.e., anything that potentially leads to answers.

Instead of doing what most people do – randomly and haphazardly hoarding tons of digital stuff hoping it will all somehow magically lead to an insight – you are taking a far more focused approach. You are detailing precisely in which areas you would like to have breakthroughs, which makes them much more likely to happen.

Think of it this way: If your Second Brain is a problem-solving machine, what kinds of problems do you want it to solve for you? Assuming that you are constantly coming across potential solutions every day, what kinds of problems do you want the solutions for?

A flexible approach to problem-solvingOne of the most powerful aspects of open questions is that they are extremely flexible.

It’s not important to have a precise number of them – the idea is to have enough balls in the air and enough potential pathways of interest that should your progress stall in one direction, you can simply set it aside and pursue something else.

It’s not important that they be “career-oriented” or have a practical use case right away. Goal-setting has a place, but favorite problems are also for the mysterious and whimsical musings that captivate you for reasons you may not be able to explain.

It’s not important for them to appear in order of priority – this isn’t a list of tasks or priorities that you have to tackle in a rigid, linear way starting at #1. Their purpose is to give you permission to move toward whatever naturally sparks your curiosity and joy right here and now.

Over time, you’ll begin to view the world through the lens of questions; they will arise spontaneously, unbidden, as a filter telling you what information matters and why.

In Part 3, we’ll return to Richard Feynman’s story and how he used his favorite problems together with a variety of “thinking tools” to produce some of the most profound breakthroughs in 20th century physics.

A big thank you to Rubén García Pérez, Matthew Brandabur, Jeremy Cunningham, Lukas Puris, Julia Saxena, Arno Jansen, and king chan for their feedback and suggestions on this piece.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post How to Generate Your Own Favorite Problems: A 4-Step Guide appeared first on Forte Labs.

September 26, 2022

12 Favorite Problems: How to Spark Genius With the Power of Open Questions

Richard Phillips Feynman was one of the most important scientists of the 20th century.

Born on the outskirts of New York City in 1918, his work in theoretical physics radically reshaped our understanding of the universe we live in at the most fundamental subatomic levels.

When it was all said and done, his biography would simply and fittingly be titled Genius (affiliate link). It is the astonishing story of a mind grappling with the deepest questions we can ask about reality, and against all odds, arriving at useful answers.

But Feynman’s brilliance was not solely due to his natural cognitive abilities. He relied on a method: a simple technique for seeing the world through the lens of open-ended questions, which he called his “favorite problems.”

You can create a list of your own favorite problems – a concrete set of questions you rely on both to filter the information you consume and to connect the dots between challenges and potential solutions.

They allow you to:

Dedicate your time and attention to ideas that truly spark your curiositySee how a piece of information might be useful and why it’s worth keepingSee insightful patterns across multiple subjects that seem unrelated, but might share a common threadFocus the impact of your work on problems where you can make a real differencePrime your subconscious to notice helpful solutions to your biggest challenges in the world around youAttract like-minded people who have the same interests and goals as youA modern Renaissance ManFeynman helped pioneer the emerging field of quantum physics, which dramatically changed our understanding of matter and energy in the 20th century.

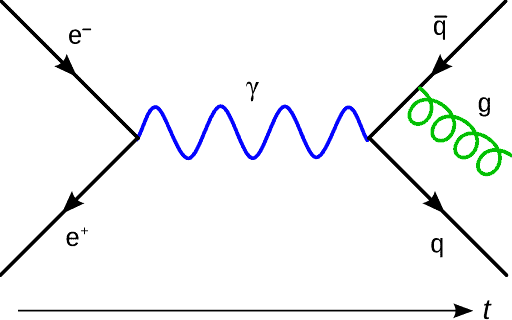

In 1965, he won the Nobel Prize for his invention of “Feynman Diagrams,” a notation system that allowed physicists to better understand the interactions between subatomic particles across time.

Incredibly, Feynman’s career was so prolific and impactful that at least three of his later achievements (in superfluidity, radioactive decay, and the study of quarks) might have also qualified him for the highest prize in science if he had published his research.

His relentless curiosity about the world led him to pursue a wide variety of research subjects: how friction worked on highly polished surfaces, how wind makes ocean waves grow, the elastic properties of crystals, and turbulence in gases and liquids, among many others.

Even today, decades after his death, the leading edge of physics known as “string theory” relies on his work as a foundation.

But none of the awards or accolades Feynman received can fully capture how stunningly diverse and wide-ranging his interests were. He refused to limit himself to one field, or even to science itself. He followed his passions wherever they might lead, conducting practical experiments along the way to confirm that his discoveries were valid.

He experimented for years with lucid dreaming and sensory deprivation to unravel the mysteries of consciousness. He taught himself how to play the drums, pick lock safes, draw nude figures, and decipher Mayan hieroglyphics. He embraced all of the surprise and serendipity that life had to offer with an attitude of childlike wonder.

Richard Feynman was a true Renaissance Man – as impressive as his scientific accomplishments were, what truly distinguishes him in our era of hyperspecialization is that he also managed to live a rich and varied life. His intense focus on his research didn’t prevent him from savoring the finer things in life – travel, culture, art, music, and family.

For me, this is Richard Feynman’s greatest achievement: he both went deep in the area where he could make a genuine contribution to society, while also embracing the full breadth of everything else life had to offer along the way.

Let’s take a closer look at how he did it.

Feynman’s favorite problemsBuried in an obscure article written by a contemporary of Feynman’s, the MIT mathematician Gian-Carlo Rota, lies a clue to how Feynman achieved his formidable reputation (emphasis mine):

“You have to keep a dozen of your favorite problems constantly present in your mind, although by and large they will lay in a dormant state. Every time you hear or read a new trick or a new result, test it against each of your twelve problems to see whether it helps . Every once in a while there will be a hit, and people will say, “How did he do it? He must be a genius!”

In other words, Feynman’s approach was to keep a list of a dozen of his “favorite problems” – these were fascinating open questions that he found himself returning to again and again in his research.

Here are some of the kinds of questions we know he pursued and that he might have been referring to:

How can we measure the probability that a lump of uranium might explode too soon?How can I accurately keep track of time in my head?How can we design a large-scale computing system using only basic equipment?How can I write a sentence in perfect handwritten Chinese script?What is the unifying principle underlying light, radio, magnetism, and electricity?How can I sustain a two-handed polyrhythm on the drums?What are the most effective ways of teaching introductory physics concepts?What is the smallest working machine that can be constructed?How can I compute the emission of light from an excited atom?What was the root cause of the Challenger Space Shuttle disaster?How could the discoveries of nuclear physics be used to promote peace instead of war?How can I keep doing important research with all the fame brought by the Nobel Prize?Each time he learned something new, Feynman used it as an opportunity to see if it could help him make progress on something he was already curious about. When he heard about a new finding in a research paper or a new result from an experiment, he would ask himself: Does this have any relevance to any of my favorite problems?

Most of the time, the answer was no. After all, the chances of making a connection between any two random ideas was relatively low.

But once in a while his method would strike gold. He would compare a new finding or result with one of his open questions – even if they were from completely different fields – and find a match. And the insights and breakthroughs that came pouring out as a result would leave everyone around him astonished.

Feynman worked on the Manhattan Project, the U.S. government’s secret effort to develop the first atomic bomb during World War II. Such a device had never been built before, and it required a mind that disregarded the conventional wisdom of the past.

Feynman used an unorthodox mathematical approach that wasn’t taught in any textbook to solve a key equation governing nuclear reactions. He devised a way for technicians to safely store radioactive materials (some of those technicians later believed it had saved their lives). Turning his attention to computers, Feynman helped invent a system for sending three problems at once through the rudimentary computers of the era, an early predecessor of “parallel processing.”

His approach required patience, but it had the advantage of helping him perceive connections that no one else could see. In his book Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! (affiliate link), he once noted, “My box of tools was different from everybody else’s, and they had tried all their tools on it before giving the problem to me.”

It may seem strange to label questions as “problems,” since that word usually has a negative connotation. But that is exactly what we are trying to do here – change the connotation in our minds from a negative one to a positive one.

Imagine what would be possible if we began to see the endless problems we encounter in our work and our lives as opportunities in disguise. Opportunities to learn, to grow, to change our minds, or to see things from a new perspective.

In Part 2 of this series, I’ll guide you through the process of creating a list of your own favorite problems.

A big thank you to Julia Saxena, Billy Oppenheimer, Vera Silva, Jeremy Cunningham, Luiz Eduardo, Arno Meijer, Colin Fortuner, Mike Haber, Alexandra P, Vaibhav Jain, Divyesh Pandya, Rubén García Pérez, Michael Pistorino, Ádil Bulkool Bernstein, Beth, Parisa R, and Yassen Shopov for their feedback and suggestions on this piece.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post 12 Favorite Problems: How to Spark Genius With the Power of Open Questions appeared first on Forte Labs.

September 19, 2022

The Only Marketing Program I Recommend – Is Back

The Keystone Accelerator is back!

Two years ago, I partnered with my top marketing advisor, Billy Broas. I said to Billy:

“The marketing side of my business has been so important and so filled with powerful lessons. I want to teach online marketing to my readers, but I’ve got to stay focused on Building a Second Brain. If you create the marketing program, I’ll support you.”

With that, our marketing accelerator for online educators was born.

What a ride it’s been, too.

You see, in that first Keystone cohort, Billy unveiled the latest iteration of a marketing framework he’d been using for years. It was a direct descendant of the framework I learned when I first got Billy’s help.

This latest version Billy calls “The Five Lightbulbs.”

This new framework was the result of years of Billy’s work with top educators, and it immediately struck a chord. People loved it.

We surveyed the participants at the end of that first cohort, and despite The Five Ligthtbulbs being just one of eight original modules, every participant (except one) voted The Five Lightbulbs as their favorite part.

The wins and breakthroughs people were getting from The Five Lightbulbs – in such a short period of time – surpassed that of all the other material.

There’s something about this approach to marketing educational products and programs that “turns on the light” for people and gives them clarity when it comes to boldly promoting their offerings.

Billy knew what to do.

You see, he is an avid Second Brainer and knows the power of distillation. He looked at everything he could teach (which is a ton – he’s like a walking encyclopedia) and applied distillation to it.

He asked himself, “The Five Lightbulbs is THE thing that works best –what if I focused completely on that?”

So he stripped away everything else from Keystone and decided to go deep on The Five Lightbulbs.

Since that first cohort, Billy has been sharing his new framework with the outside world. The response has been phenomenal.

Ryan Deiss, the CEO of DigitalMarketer.com and one of the world’s top marketing experts, hired Billy as a consultant. Together, they applied The Five Lightbulbs to Ryan’s organization, using it to get their team aligned on messaging and to craft new marketing campaigns.

One of the world’s top copywriting trainers, David Garfinkel, called Billy’s framework “A brilliant construct.”

More than one experienced marketer has said, “The Five Lightbulbs is going to revolutionize marketing.”

Soon, you’ll hear from Keystone members using the framework to grow their businesses.

(By the way, you can learn the Five Lightbulbs here in 10 minutes. It’s extremely intuitive)

Learn the framework, but don’t be fooled by its simplicity. The Five Lightbulbs is like an iceberg – most of it lies beneath the surface.

Here at Forte Labs, we’re now using The Five Lightbulbs in all our marketing efforts. My Director of Marketing, Julia Saxena, was trained by Billy. When she sits down to create marketing content for us, she follows this approach.

Today, I’m excited to announce the third cohort of our Keystone program, and you’ll get the chance to put The Five Lightbulbs to work in your business.

If you’ve been looking for a fresh marketing approach, Keystone delivers it.

So, who is Keystone for?

Here’s the quick way to know: If you’re creating content online for your business, Keystone can help.

If you’re creating sales pages, emails, blog posts, podcast episodes, or YouTube videos – in the hope of growing your business – Keystone can help.

If you:

Are completely overwhelmed by marketingFeel icky or inauthentic when you sit down to create marketing contentAre too in the weeds with your topicHave no idea how to take someone from being a stranger to a customerIf any of these are true, Keystone can help.

What began as a mission to help cohort-based-course creators has blossomed into something greater. Our graduates include consultants, coaches, copywriters, course creators, service providers, and thought leaders seeking to impact people’s lives through digital platforms.

Do you know what we’ve noticed?

The Keystone participants are not only using the process they learned to sell their online courses. They are using it to strengthen their entire business.

Glen Lubbert, one of our top BASB mentors, emerged from Keystone with a brand new way to package and present his expertise. He now uses his new messaging in public talks and all his products.

Other participants have repositioned their products based on what emerged inside Keystone. One consultant, Jordan, tripled his prices mid-program and immediately closed three deals.

How? He got clear on his prospect, his message, and how to best convey the value he delivers.

You see, Keystone can make your business more resilient. It doesn’t matter the product you sell – the format of your product can and will change over time.

At Forte Labs, we’ve gone from a 5-week program down to a 3-week program. We’ve gone from one-off cohorts to an annual membership. We now have a physical book, evergreen courses, corporate consulting, and now, a thriving YouTube channel.

How do we align our products around a common message?

How do we make sure we are advancing our audience towards becoming paid customers?

How do we get our products and marketing channels to complement and compound on each other? Rather than just pile more work onto our plate?

The answer: These products and platforms branch out from a central marketing message.

That message is shaped by our Five Lightbulbs. Literally, we have a “messaging map” in our company with our Five Lightbulbs fully fleshed out. We continually update and refer to it.

(You’ll create your own messaging map inside Keystone.)

Now, you know I don’t recommend just anybody. I only recommend the people I’ve personally worked with and can vouch for.

On the writing side, I’m a vocal supporter of David Perell and his Write of Passage course. On the personal development side, I recommend Joe Hudson and his Art of Accomplishment program.

Well, on the marketing side, I give my full support to Billy Broas. And in an industry filled with fake gurus, hucksters, and slime – it’s a relief to find someone respectable.

After all, marketing is the thing that makes your business possible. Without marketing, you don’t get customers or clients. If that happens, nobody gets to benefit from what you know – and that’s just a shame.

Yes, you know your topic well. You’ve studied, trained, and worked in your field.

But when was the last time you invested in your marketing education? Have you fed your brain with enough marketing knowledge to keep pace with your topic knowledge?

If you’re like I was, you’re nutrient-deficient on the marketing side.

No, you don’t need to become a marketing expert. You don’t need to learn everything. You only need to learn what matters most. Later, you can delegate and oversee, like I currently do with Julia and her team.

But my marketing education is the best investment I’ve made.

Keystone will give you one of your best returns on investment. It will strip away the B.S. and set your attention on the big needle movers. When you gain this new, clearer vision, everything about marketing your business becomes easier.

Billy’s teachings can help you, and I now invite you to keep reading and learn more about our marketing approach. The next step is to join our interest list.

Starting Monday, September 26th, you’ll start receiving an email series. That series will elaborate on the topics introduced in this email. I’ll share more about what I’ve learned about marketing over the past ten years, growing my company from a solo career to a profitable business employing 22 people with thousands of customers across the world.

Then, you’ll have an invitation to join the upcoming Keystone cohort. It’s four weeks long, running from October 24th through November 17th. Mark your calendars now.

Thanks, and talk soon.

Tiago

P.S. Please, if you don’t get marketing help from us, get it from somewhere. Don’t be “above” investing in your marketing education. Again, it’s been the best investment I’ve made.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post The Only Marketing Program I Recommend – Is Back appeared first on Forte Labs.

September 12, 2022

Everything Is Information | What Is Money Show with Robert Breedlove

I talked to Robert Breedlove on the What is Money Show about Building a Second Brain, email, PARA, and more.

We covered…

What is “Inbox Zero” and is it something you want to aspire toHow to organize your email with the “executive approach”How I manage my daily calendar and what tool I useThe PARA Method for organizing your files and responsibilitiesTips for taking notesClick below to watch the full interview on YouTube:

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post Everything Is Information | What Is Money Show with Robert Breedlove appeared first on Forte Labs.

September 9, 2022

Growing a Sustainable Business & Living a Life of Service | The Build In Public Podcast

On the Build in Public podcast, KP and I dove into my journey as an entrepreneur, course creator, author, and dad.

We covered…

Why and how I “build” my book in publicHow being a dad influences my business decisionsWhy hiring people is a lot like having kidsWhat ambition really meansWhen can you call yourself an entrepreneurHow David Allen’s Getting Things Done changed my lifeAnd much moreClick below to watch the full conversation on YouTube:

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post Growing a Sustainable Business & Living a Life of Service | The Build In Public Podcast appeared first on Forte Labs.

August 31, 2022

The 1-Percent Rule for Capturing the Best Information | Smart Passive Income Podcast

I joined Pat Flynn on the Smart Passive Income podcast to chat about everything Building a Second Brain.

We covered…

What is a Second Brain and how to use itHow to find the right notetaking app for your needs and get started with it in the first 30 daysHow the CODE system can help you deliver higher quality work with less effortThe 1-percent rule for capturing the best informationThe question you should ask yourself when you take notesThe PARA system for organizing information effectivelyWhy you should never organize information as you capture itAnd much more…Listen to the full episode here.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post The 1-Percent Rule for Capturing the Best Information | Smart Passive Income Podcast appeared first on Forte Labs.