Tiago Forte's Blog, page 7

July 3, 2023

The Financial Reality of a Traditionally Published Book – a Complete Breakdown

The next area I want to examine is finances: How much money has the book made in the year since its release? How much did I spend to catapult it to bestseller status? And would I do anything differently?

Here are the real numbers.

How much money did the book make by itself?A year after its release, Building a Second Brain has sold over 100,000 copies in the US and UK alone, including 13,000 pre-orders made in the 9 months preceding its release.

In total, I’ve made $478,800 in advances across all formats and translations of the book.

That includes $325,000 for the initial U.S. rights, plus another $153,800 for 20 other foreign rights sales ranging from $800 in Turkey to $31,000 in China. In other words, all the foreign rights we’ve sold so far add up to 47% of the value of U.S. rights, though it’s expected to keep climbing.

Now that may sound like a lot of money at first. It’s definitely in the top .1% of advances, and a dream come true for any author. But wait until you hear what the corresponding outlay was.

Here’s the breakdown of the main costs:

$152,000 in U.S. federal (37%) and California state taxes (12.5%)$140,000 for the promotional agency$125,000 (plus a percentage of ongoing royalties) for the editor$40,000 for design (book cover, illustrations, swag, and visual brand identity)$25,000 for the website (plus ongoing maintenance)$15,000 for a book launch party$12,000 on three multi-day writing retreatsTo summarize, I’ve made about $478,000 and spent $509,000 in my quest to make Building a Second Brain a bestseller. In other words, despite this book becoming a breakout success, we’re only approaching breakeven.

I’m not including a variety of indirect and personal costs we incurred to make the book possible, from money spent on babysitters and house cleaners to takeout dinners when I was too exhausted to make food. These are just the direct costs required to create and promote it.

If I include the time our full-time staff (not including me and my wife Lauren) spent on the project, these figures look very different. Our team of 6 employees estimates that 28% of their total combined capacity was spent on the book over the last three years, which amounts to another $516,000. Taking that number into account, Forte Labs has spent over a million dollars on this book.

These figures also don’t take into account royalties. We seem to be about halfway through earning out the advance, which means that in about a year (mid-2024) I should begin receiving about $26,000 per month in royalties (8,700 books sold per month, with my share at $3 per book).

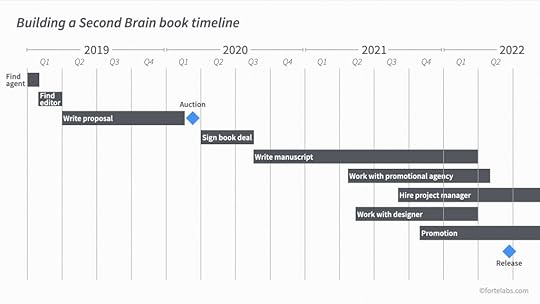

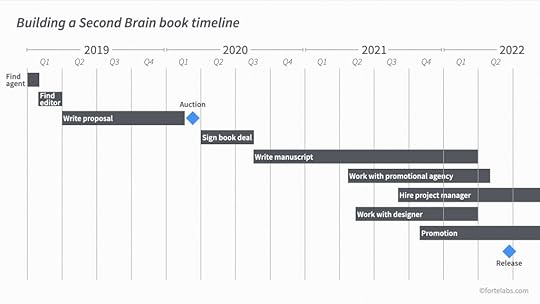

At this rate, and taking our staffing costs into account, it should take another 18 months after that, or until the end of 2025, before we break even on the entire project. That’s 3.5 years after the book’s release, and a full 7 years since I first started working on the proposal in early 2019.

To summarize, I can’t help but conclude that, if the book is viewed in isolation, writing traditionally published books is an awful business model for authors.

What if we include online course sales?What the numbers above don’t take into account, of course, is the extent to which the book has fueled sales of our other products.

Based on our internal data, 16% of our newsletter growth in 2021 and 2022 came from people interested in the book. Since our email newsletter is our main sales channel, this corresponds to roughly $720,000 in course sales if we assume those people purchase in typical numbers. So by that measure, the revenue associated with this book rises from $478,000 to about $1.2 million in total. Which means we’ve already broken even on the endeavor and profited almost $200,000 before even starting to receive royalties.

It has likely also had a positive impact on our other sources of revenue (such as YouTube ads, newsletter sponsors, other ebook sales, affiliate commissions on SaaS tools, and speaking gigs), but it’s difficult to know how much came directly as a result of the book, so these are conservative assumptions.

As a side note, we have a lot of evidence that the book also significantly cannibalized sales of our courses. Comments such as “I read the book and got what I needed, so didn’t feel the need to buy the course” became more common. My conclusion is that the book caused some people to not buy the course, and caused others to buy the course who wouldn’t have otherwise. So the book changed our customer base instead of just growing it.

My conclusion is that traditional publishing only makes sense financially if you have a product or service to sell on the backend. That could be another book, an online course or other program, a set of templates, coaching, consulting, or speaking services.

If I had to spend 7 years working so hard on my book only to break even, I would feel pretty disappointed regardless of any other accolades or milestones I’d reached. The uptick in sales of our products balances the books and makes the whole endeavor worthwhile.

Publishing a book is a lot like launching a massive global marketing campaign for an idea.

You are creating tons of assets, forming dozens of partnerships and alliances, recruiting hundreds of people who will eventually take part in its creation, and leveraging global supply chains throughout the world to make your book available “wherever books are sold.”

All that is worth doing for an idea you deeply believe in, but you wouldn’t expect a marketing campaign to be profitable in and of itself. From that perspective, it’s remarkable that a marketing campaign can even pay for itself and break even! Your campaign will ultimately attract vast amounts of attention, but what do you want to do with that attention once you have it? What action do you want people to take?

A common criticism of traditional publishing is that it isn’t profitable for writers. Based on the numbers I’ve shared, that seems to be true even for a breakout bestseller. But it also kind of misses the point. Writers are no longer just narrow specialists – they have the potential to be global media businesses in their own right. And a business has to do more than supply one product. It has to think about the holistic picture of profitability that is needed to ensure its survival.

The critical importance of having a courseUpon further reflection, having a course is even more pivotal for writers than I understood when I started for a few reasons.

Before the book: First, you need a way to thoroughly validate and prove your ideas before you even put them on the page.

If you’re going to dedicate years of your life to a set of ideas, you had better be sure they work. The best way to do that is to test them with real people through speaking, teaching, coaching, or consulting to see how effective they are for a wide variety of people. Teaching what you know as part of a course allows you to get rapid feedback and iterate through multiple versions of your message to find the one that sticks. Live cohort-based courses are the single most effective way to do this in my experience since live teaching gives you instant feedback on a sentence-by-sentence level.

While writing the book: Second, you need a way to sustain yourself financially during the writing of the book.

As I’ve shared, I fully intended to spend 100% of the advances for my book on its promotion, which meant I needed another source of income to pay my bills (not to mention my team). While speaking, coaching, and consulting can serve to test your ideas, an online course has the advantage of selling while you sleep (or write).

After the book comes out: And third, you need a way to monetize and capitalize on the attention your book will attract once it’s out.

You need a “next step” for people to take once they’ve read your book and want to put it into action. While in theory, you could create this product after the book comes out, it’s much better to have it ready on the day of its release since you’ll have your hands full promoting the book itself.

What I would do differentlyIf I could go back in time and do it all again, I don’t think I’d spend money differently. I took a maximalist approach of saying yes to everything, which means I left no stone unturned and thus have no regrets.

From a financial perspective, the expenses I incurred seem high but justifiable. You only launch your first book once, and I didn’t want to scrimp and save only to look back and wonder what could have been. That meant I probably said yes to expenditures that weren’t strictly necessary, overpaid instead of negotiating harder, and was less strategic and discerning than I could have been.

On the other hand, I learned a tremendous amount about what works and what doesn’t, which was my ultimate goal. Even if we’re only breaking even now, we also created an evergreen asset that will be valuable for many years into the future.

An informal analysis I did of 20 bestselling nonfiction books revealed that their Google search volume peaked on average 6 years after release. If the same is true of mine (and it’s a huge assumption that it will become a perennial bestseller), then BASB will reach its zenith of popularity around 2028. I can barely imagine how much will have changed in that time, both in the world and in my personal life and business. In a way, it’s out of my control anyway. I’ve given the world the best gift I know how to give, and what happens from here on out is up to the world.

In the next installment, I’ll detail how exactly we went about promoting this book.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post The Financial Reality of a Traditionally Published Book – a Complete Breakdown appeared first on Forte Labs.

June 19, 2023

The 5 Pillars of My Writing Process

In the second part of this blog series, I shared how I treated my book as a series of small projects culminating in a final product.

The same was true for each of the 10 chapters it contained: each one was its own project, with a deadline and a goal for what that chapter was trying to achieve. Each chapter had its own project folder (according to my PARA Method), where I collected everything I would draw on – notes, sources, supporting materials, stories, action steps, and key details.

These projects guided me over the 14 months it took to finish the manuscript. Here are the five pillars of my writing process that I depended on to make consistent progress, each one building on the one before:

Pre-existing blog postsOutlinesMorning writing sessionsWriting retreatsOutsourcing my lifeLet’s dive into each one.

#1 – Pre-Existing Blog PostsThe single most important resource I drew upon was my blog, where I’d published almost 500 articles containing more than 700,000 words since 2014. I always viewed these articles as research for a book I would write one day, and that is exactly what they became.

On average, about 70% of each chapter in the book was made up of writing I’d already published on the blog, though it often had to be extensively rewritten to conform to its newfound style and purpose. I can’t overemphasize how crucial it was to be able to start each chapter with 70% of the background research already done.

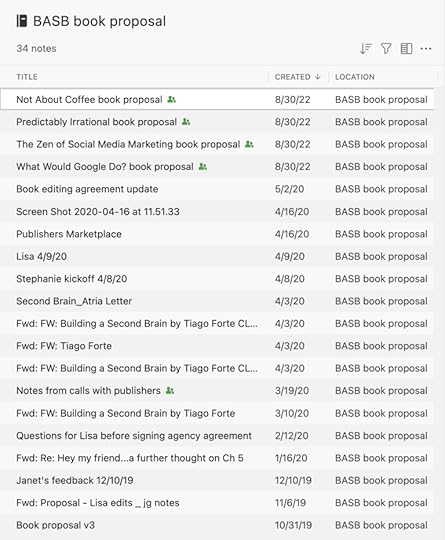

The remaining 30% came from notes I retrieved from my Second Brain. In total, I drew on 254 notes (saved as long ago as 2015) to round out the manuscript. Trying to digest all of those at once would have been a nightmare. By breaking them down into 10 chapter-specific groups, I only had to load an average of 26 notes into my head to complete each chapter. Totally doable!

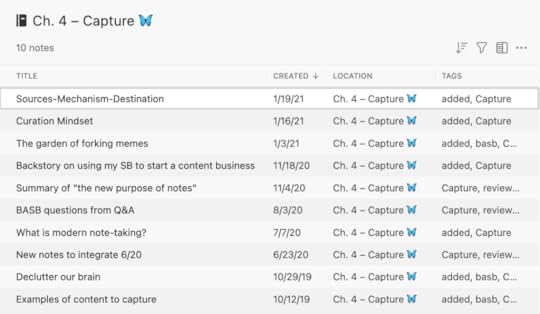

Here’s what the project folder for Chapter 4, on how to capture information in one’s Second Brain, looked like:

That’s only 10 short notes encompassing the vast field of “knowledge capture”! And it was more than enough material for my needs. In fact, I didn’t even use all these notes and had to cut out a lot to get it to a reasonable length.

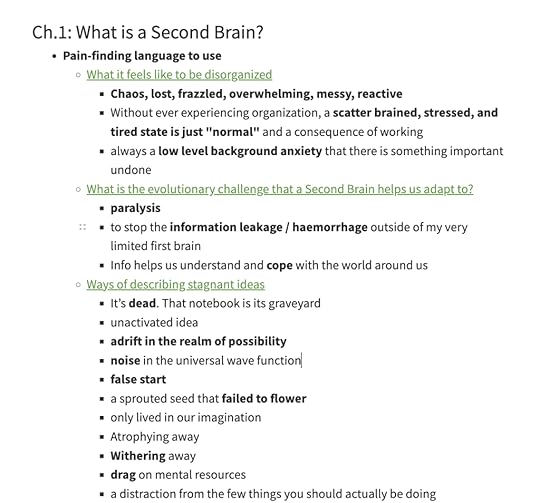

Here’s an example of one of the notes from this folder, containing my responses to a Q&A about knowledge capture. The bolded passages are the ones I thought were good, and the highlights in yellow indicate points that were important enough I considered incorporating them into the book. (You’ll notice that this is my Progressive Summarization technique in action.)

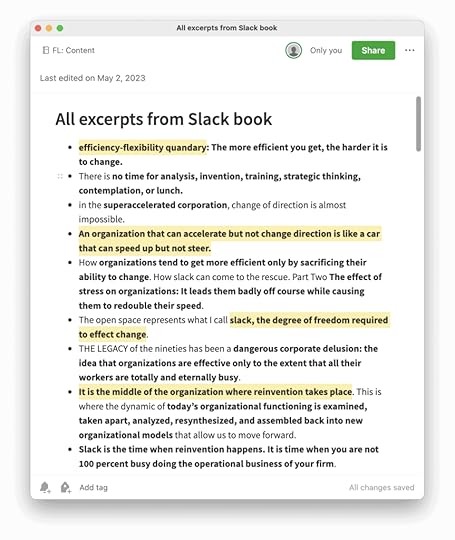

Here’s another example (view the public note) of how I deconstructed a publication from Microsoft called The Innovator’s Guide to Modern Note Taking, turning it into a highlighted chapter-by-chapter summary that was easy to reference in the flow of writing.

Treating each chapter as its own self-contained project also made it easy to go back and cite all my sources once the writing was complete. All that material (whether I ended up using it or not) remains available in my Second Brain in Evernote for reuse in future projects I may take on.

#2 – OutlinesAfter I had compiled the notes I thought I might want to use in a project folder for a chapter, my next step was to turn them into an outline. In my book, I call such a “digital outline” that links to other notes an “Archipelago of Ideas.”

Writing is inherently hierarchical, taking the form of:

Point 1Supporting point ASupporting point BSupporting point CPoint 2Supporting point ASupporting point BSupporting point CWhich means that the outline I used as the “scaffolding” for my writing also had to be hierarchical. This is where outlines can be so powerful: since they mirror the logical structure of the writing they will ultimately turn into, outlines can serve as a kind of “map” of where you’re going as you put down one sentence after another.

For example, here’s part of my outline for Chapter 1, where I draw on my past notes about what it feels like to be disorganized. Note how the green links lead to the original source, while the points indented underneath them contain the specific excerpts from that source that I thought might be worth using:

Outlines also serve another purpose: they’re markers for where you left off. That is an important function when even a single chapter might take many weeks to complete, spread across dozens of writing sessions.

#3 – Morning Writing SessionsI was used to writing multiple thousand-word articles since I’d been doing that for years on my blog. But each chapter in my book was about 6,500 words long on average, and after I’d finished a first draft of the first couple of them I quickly realized that this was an entirely different scenario.

Writing a single stand-alone article, all you have to remember is the main points of that one article. But when writing a book, you have to keep in your head 10 or 20 times more information. Every time I wanted to make an edit – whether it was changing the spelling of “note-taking” to “notetaking” or a much more substantive one like changing how I framed the purpose of a Second Brain – I then had to consider all the implications that change created.

Changing the spelling of a term is easy – all you have to do is perform a “find and replace” search. But for more subtle edits with unexpected side effects, it’s far more difficult. How could I detect that an edit in Chapter 7 to broaden the examples of “self-expression” I provide, also requires a different set of examples in Chapter 4 for which kinds of content they should save in their notes in the first place? (This is a real example).

Essentially, the “mental model” of the book you have to keep in mind is always growing, which means as the manuscript grows in size, the cognitive load needed to “hold it in mind” compounds exponentially.

To overcome this challenge, I decided to do everything I could to make my weekday morning writing sessions as immersive as possible. I canceled all meetings and commitments before lunchtime, sequestered myself in our home office with noise-canceling headphones, and started each morning by picking one problem I would dedicate myself to that day.

A “problem” could be deciding which term to use for a concept, choosing a metaphor to explain a technique, deciding on the exact sequence of points to build an argument, deciding which details in a story to include and which to remove, etc. It would often take an entire morning just to solve one of these problems, which explains how writing a book can take years.

I would typically sit down to work on my chosen problem for the day first thing in the morning, to give myself the longest possible runway for “cognitive liftoff” before I got tired or interrupted. But sometimes as I began to unpack the problem it would dawn on me that I couldn’t resolve the problem that day. Either because I didn’t have enough source material to draw from, or there were other more fundamental problems that had to be solved first, or because I simply didn’t have the energy.

In those situations, as soon as I recognized I wasn’t going to succeed on my current mission, I tried to switch as decisively as possible to preparing my tomorrow self to be able to solve it: distilling the notes I would need, getting feedback from others, listing my options, reducing the scope of the problem, and gaining clarity on what I was trying to achieve and why. My goal was to eliminate “thrashing” – the torturous process of trying to force myself to reach a goal that I wasn’t ready to reach.

Most of the writing problems I faced could be resolved in a morning writing session or two using the approach above. But some challenges were so great that they required larger blocks of time.

For those handful of major challenges, I turned to a more heavy-duty approach: off-site multi-day writing retreats. I ultimately went on 3 writing retreats over the course of about a year, and they were crucial to overcoming critical bottlenecks in my writing process. I chose the locations carefully:

An Airbnb apartment overlooking the beach in MalibuA high-end hotel near the waterfront in Marina del Rey, in Los AngelesA rural inn in the wine country of Temecula in Southern CaliforniaThese retreats had to be as efficient as possible because I was leaving my wife and infant son at home, and because each one cost thousands of dollars. Here are 12 guidelines and rules of thumb I used to make them as productive as possible:

Choose a place 1-2 hours from home, so it feels like “a world apart” but you don’t waste too much time in transit.3 nights and 4 days seemed like the ideal duration – long enough to get into deep flow, but not so long that I got lonely or felt like I was away from my family too long.Choose hotels, because you want everything to be provided for you and to not have to think about bedding, food, etc. during your time there (for one of my retreats I stayed at an Airbnb, but I noticed the higher cognitive load of having to think about these things).The ideal writing spot is minimalistic and quiet to avoid distractions, but also comfortable so that discomfort doesn’t become a distraction; hotel rooms are best because you can control every aspect of the room without needing permissionDo the prep work and planning for what you will tackle before you get there, otherwise you’ll spend the first day just getting your bearings.Make sure you’re well-rested and well-slept before the retreat, otherwise you’ll be too tired to focus and just spend the days sleeping.Ergonomics are important for such long writing stretches, so bring a laptop stand or external monitor, and external keyboard and mouse, and make sure your chair and desk are comfortableExercise regularly before and during the retreat, because you’ll need the physical stamina to stay in flow for such long periods.Set a rule that you’re only allowed to remove things, not add things, which helps you avoid the temptation of “doing more research.”Use long walks in nature and immersion in water (swimming pools, hot tubs, or a lake or ocean) to “reset” after a long day of writing.Pay close attention to your diet, since you need to maintain your energy levels for the long haul; avoid one-time energy spikes like sugary coffeeMake sure you have everything you might possibly need for the duration of the retreat (at my retreat in Marina Del Rey, I had to go into town to get a bathing suit because I’d forgotten one, and it somehow ended up consuming half a day by the time I got back to writing).

Here’s how I spent the 58 hours of one 3-day retreat (notice that even with all the focus I could muster, less than half the time was actually spent writing):

24 hours of writing and editing16 hours of sleeping3 hours resting3 hours taking and reviewing notes3 hours eating2 hours exercising7 hours miscellaneous#5 – Outsourcing My LifeThe fifth and in many ways most important pillar of my writing process was essentially outsourcing my life during the period I was most immersed in writing.

Early on in the process, it became clear that I simply didn’t have the bandwidth to manage my quickly growing business, conduct my busy personal life, care for my new family, while also writing a 65,000-word manuscript. It just wasn’t physically possible.

I made the decision to lean on all the people in my life who supported me. I know it was an incredible privilege to be able to do so. As I wrote in The Psychological Toll of Writing a Book, some of the steps I took included:

Limiting myself to two activities – focused writing and recovery – and eliminating, outsourcing, reducing in scope, or postponing everything else (including signing up for a daily meal delivery service for our family, hiring someone to do all our housekeeping and laundry, and letting my team handle most decisions).Leaning on our families – my wife Lauren and I made more requests of our families during this period than ever, for food preparation and babysitting and home projects and much more, and I discovered how fortunate we are to have such generous, caring families behind us.Spending money to save time – we were fortunate to have an online education business that was booming during the pandemic, and I used the money that was coming in with abandon to save even the smallest amount of my mental energy, from buying a new minivan to hiring a personal assistant and personal trainer to getting everything we needed delivered.Getting feedback constantly – I didn’t have enough mental horsepower to make all the decisions that needed to be made for the book, so I drew heavily on the ideas and contributions of everyone around me. I would discuss thorny writing challenges late at night with my wife, get feedback from the team on key decisions, talk through my thinking with friends, collaborators, and advisors, and even run polls on Twitter to test different options.Trusting my publishing team – early on I realized that I either needed to trust the people I’d partnered with to bring this book to fruition (my agent, publisher, and editor) or else I’d have to fight them every step of the way. I knew I didn’t have the energy for that, so I decided to trust them even when I didn’t understand or agree with their advice.In the next post, I’ll share how we marketed and sold the book that emerged as a result of this process, leading to a spot on the bestseller list.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post The 5 Pillars of My Writing Process appeared first on Forte Labs.

June 11, 2023

The Rise of Prediction Factories: How AI Allows Us to Replace Rules with Decisions

Two books I read recently helped me tremendously to understand what’s happening now with Artificial Intelligence: Prediction Machines and Power and Prediction (affiliate links) by Ajay Agrawal, Joshua Gans, and Avi Goldfarb.

The authors are economists and professors at the University of Toronto, one of the leading institutions studying the economic impacts of AI. Their books helpfully frame the advent of AI as just one in a long series of economic paradigm shifts, each of which has been closely studied and dissected before.

This article is a summary of the ideas I found most enlightening and impactful, and my interpretation of how they apply to modern knowledge work.

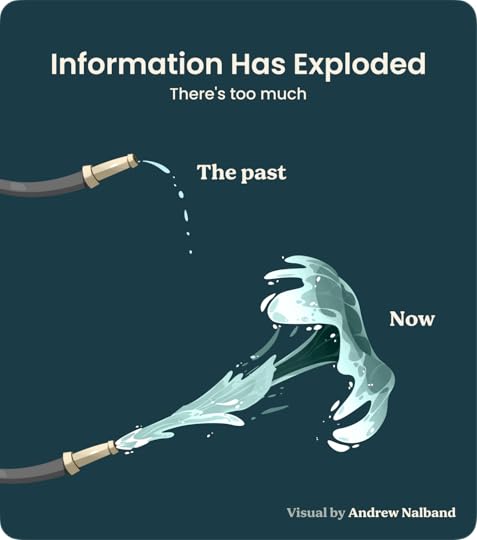

AI Is PredictionIt’s easy to get caught up in all the hype around AI’s potential, but at the fundamental economic level, AI is about dramatically lowering the cost of prediction.

When you ask ChatGPT “What is the capital of Delaware?”, the machine learning algorithm that powers it doesn’t “know” the answer in any sense. Instead, it is predicting “What does the user want to hear?”

But what exactly is prediction?

We use that word in a day-to-day sense of “guessing what’s going to happen,” but here we’re using it in a much broader sense. Prediction is the process of “filling in missing information.” It takes data you have, such as shoppers’ buying habits in a store, and uses it to generate data you don’t have, such as what they’re likely to buy next.

Think of each time you swipe your credit card at a store. The merchant has no idea who you are or what your creditworthiness might be. No human at the credit card provider knows either.

It is an algorithm that crunches the data it has about you, as well as the specifics of the transaction you’re trying to make, and then in seconds provides an answer: Approved or Not Approved. That is an example of a prediction not about the future, but about whether this transaction is authorized right at this moment.

Machines predict whether a smudge on an x-ray might be a tumor. They predict whether the person looking into the iPhone camera is its owner or not. They predict what you might want to buy next on Amazon, which links you might want to click on Google, and even when to automatically apply the brakes in your car to avoid a collision.

Prediction isn’t only about predicting what will happen in the future – it is about predicting what data a user might want.

The Mass Production of PredictionPutting on an economist’s lens, we can think of modern AI as a dramatic fall in the cost of prediction. Just as the factories of the Industrial Revolution started churning out mass-produced consumer goods, making previously rare and expensive items suddenly cheap and commonplace, we are witnessing the rise of “prediction factories” doing much the same with information.

Many of the highest-paying jobs requiring the most training involve making predictions. Doctors predict the right diagnosis, lawyers the right legal argument, and engineers the most effective piece of code to accomplish a function. Previously it was tremendously expensive to access the predictions of these highly trained professionals, but the price of that particular commodity is now plummeting.

What happens when the price of something drops? We typically find many more ways to use it. In other words, as the price drops, demand goes up.

The economist William Nordhaus documented how the price of artificial light plummeted by a factor of 400 from the early 1800s to today. We replaced kerosene with electricity, and it became trivially inexpensive to light our homes and offices at all hours.

In response, our consumption of artificial light exploded! We learned to use light carelessly, with abandon, illuminating everything from our garden pathways at home to empty streets at night.

The invention of computers similarly made arithmetic – a valuable commodity previously requiring highly trained bookkeepers – so cheap that we use it now without a second thought. We didn’t just consume more arithmetic – we also found radically innovative and unexpected new ways to use it: to play digital music, manipulate digital images, send digital messages, and consume digital content in all forms.

Note that the digital spreadsheet eliminated the most time-consuming activity for bookkeepers: doing arithmetic calculations. You might think that the entire profession would have disappeared as a result. But products like VisiCalc (the very first spreadsheet computer program) actually made their work more valuable overall. You could easily calculate the expected return for various projects, and then run multiple scenarios using different assumptions.

The same people who had laboriously calculated the answers by hand in the past were now best positioned to ask the right questions of the new computerized spreadsheet. Instead of making them obsolete, the new technology augmented them with superpowers.

What will happen as the cost of prediction goes from “expensive” to “practically free”? We need to understand a couple other points to find out.

AI Decouples Prediction And JudgmentOne reason prediction is currently so expensive and so few are qualified to provide it is that it is bundled with another rare quality: judgment.

When you ask your doctor for a diagnosis, you don’t just want to know your odds of survival (which is a prediction). You also want to know the course of treatment they recommend. That takes judgment. The judgment of what to do next always depends on the prediction of what will happen if we do.

“If you take this test, we’ll know what’s causing your pain.” “If you take these pills, your symptoms will be alleviated.” “If you undergo this surgery, your prognosis will improve.”

In other words, judgment has always been bundled together with prediction, which makes it even more difficult and expensive to access them in combination.

While prediction says what is likely to happen, judgment assigns value to the possible outcomes. It is the skill of determining the reward or profit of an outcome. Prediction says what will likely happen; judgment decides how much that outcome is worth to you.

To exercise judgment, you need to know what you want, and how much it matters to you to get it. It is about making tradeoffs to achieve the highest value possible from the options at hand.

Both prediction and judgment are combined to produce a crucial capability: decision-making. Decision-making is at the core of most occupations today, not to mention every moment of our daily lives.

Schoolteachers decide the best way to educate their students. Managers decide who to recruit and who to promote. Police officers decide how to handle potentially dangerous situations. Parents decide how much screen time their kids can have.

As humans, we have always had to do these three things – prediction, judgment, and decision-making – together.

But now that prediction is being unbundled and made superabundant, we have the chance for the first time to break this process down into its constituent parts. We can start to think clearly about which human activities will then diminish in value, and which ones will increase in value.

AI Allows Us to Replace Rules With DecisionsAs talented as humans are at making decisions, it is also tremendously taxing for us.

Think about the last time you made a major purchase for your home, like an oven, mattress, or new car. It probably took days if not weeks of serious reflection, researching and comparing options, identifying essential features, weighing tradeoffs, and of course, determining what you could afford.

To mitigate the tremendous mental and energetic cost of decision-making, we’ve developed countless rules as a society to guide our actions. We always stick to the right on streets and walkways (or left, in certain countries). We always take our trash out to the curb on certain pickup days. We always start work around the same time and end at the same time.

We may chafe at some of these rules, but there’s no question they save us a staggering amount of cognitive effort. So much so that we add a whole new set of rules to govern our personal lives: always eat this, never eat that; always shop here, never shop there; always do it this way, never do it that way.

We form these habits and rules when it costs too much to optimize our decisions. We decide not to decide. Just try to imagine how difficult life would be if you had to invent a completely new routine every day.

AI is a disruption to this rules-based order in which we live. If our rules exist to save us energy, and the reason we need to save energy is because decisions are so taxing, and one of the key inputs to decisions are predictions, then by making predictions cheap and plentiful, AI changes the very basis on which our society runs.

Here’s an example: We typically follow the rule to arrive at the airport two hours before the scheduled departure of our flight. This rule is so ingrained in us that it feels almost like a law of nature.

But it’s helpful to examine why this rule exists in the first place. It comes down to the large degree of uncertainty surrounding our arrival at the airport and getting to our gate. We don’t know what traffic will be like, how long the parking or dropoff will take, how long the lines will be at check-in and security, or any one of a number of other delays or snafus that might arise.

We can’t easily acquire the information that would be needed to reduce that two-hour buffer, so we make do: we leave early, bring lots of reading material or entertainment devices with us, and assume we’ll be waiting for a long time.

Now imagine if you had an AI that could take in all the needed information – your personal habits and time needed to get ready; local traffic and weather patterns; details about the layout and accessibility of the departing airport, and even data like the typical on-time departure rates for the airline and specific flight you’re taking. From all this data it could generate a customized airport departure time that told you exactly when to leave to maximize your chances of making your flight while minimizing the time you’ll have to wait.

Rather than blindly following a hard-wired rule like “two hours before,” you’re now following a personalized recommendation suited to your situation. In other words, because the prediction of how long it will take to arrive at your flight has become so cheap, you can now make the decision of when to leave, rather than following a rule.

Instead of making do with uncertainty, you now have the option to optimize your decision. You gain access to more options, without having to pay the cost of calculating them. You can contemplate more complexity with less risk. Rather than uncertainty being a threat or something to tolerate, it opens up more pathways for you to choose from.

When the Price of Something Falls, Its Complements Increase in ValueThere’s another piece to the puzzle we have to understand: when the price of something falls, anything that is a “complement” to it will gain in value.

For example, imagine there was a technological breakthrough in battery technology and all cars could now be powered virtually for free via built-in solar panels. People would take many more trips and drive many more miles in response, leading to a rise in the value of all the complements to driving: drive-through fast-food and coffee places, roadside rest stops and convenience stores, and even streaming music and audiobooks.

If we think of prediction as just such a raw material that has suddenly plummeted in price, we should expect anything that is a complement to prediction – that is consumed along with prediction – to become more valuable.

This includes data because high-quality predictions require a lot of data. Any data that is difficult to acquire or that changes frequently will be disproportionately valuable, and those who know how to acquire it will be sought after.

It includes judgment – the skill of knowing which predicted outcomes are valuable and why. Judgment is based mostly on experience, and thus human experience of unusual or complex events will become far more valuable. Paradoxically, the more we automate business and society, the fewer opportunities humans will have to acquire hard-won experience, thus making it even more valuable.

It also includes action – we still need a human to take most of the actions inspired by the predictions that machines make. People who know how to effectively navigate the tremendous complexity and uncertainty of the real world, and to advance particular ideas or causes or points of view, will be more valuable than ever.

And finally, a sense of perspective is a complement to prediction that will rise in value. One definition of wisdom is “broad framing” – not losing sight of the big picture and keeping seemingly intractable problems and crises in perspective. As each element of decision-making gets increasingly unbundled into ever more specialized and narrow algorithms, this kind of broad perspective will become even more challenging to maintain than it already is.

At the same time, human-generated prediction will fall in value as it faces more and more competition from the “prediction factories” of AI.

For example, cab drivers were once required to memorize all the roads in their city to be able to efficiently route passengers to their destination. This knowledge would often take them years to acquire and was highly prized and well-compensated. But as soon as we all gained smartphone-based navigation, the value of a cab driver’s ability to predict the best route to a location dropped to nothing.

AI Deployment is Going to Take a Long TimeAI pioneer Andrew Ng, who founded the Google Brain project and was chief scientist at Baidu, proclaimed that “AI is the new electricity. It has the potential to transform every industry and to create huge economic value.”

We can look to history for examples of what it looks like when an epochal new technology transforms society. And using electricity as a guide, that history suggests the spread of AI will take a long time.

Thomas Edison’s invention of the lightbulb in 1879 is hailed as one of the most revolutionary moments in human history. And yet, two decades after this groundbreaking moment, electricity had barely begun to be adopted – only 3% of US households had it. That number was barely higher in factories.

However, fast-forward another couple of decades, and electricity was everywhere, reaching half the US population. Understanding what happened in those “in-between times” is crucial to predicting how AI will likely play out in our lifetimes.

Electricity was a challenge to the existing dominant source of power in the late 19th century: steam power.

Steam power was reliable but highly inefficient, losing 30–85% of its potential before it could be applied. Steam power would typically enter a factory at a single source, a 3-inch drive shaft of iron or steel to which belts and pulleys could be attached throughout the rest of the building. This system had one serious drawback: you either had to power the entire factory at full steam, or not at all. You couldn’t use power in small doses, or in different locations.

By changing from steam power to electricity, factories unlocked enormous advantages. They could be built far away from cities, in cheaper and more spacious areas. They could mount electric drives to individual machines, making them portable for the first time. It became cheaper to use power in smaller doses, only if and when needed, rather than powering the entire factory. And it was cleaner and more consistent as well.

But why did it take four decades before such a powerful innovation spread to half the country? It was because it couldn’t be tacked on to existing factories. The very concept of a factory had to be reinvented, and new ones had to be designed and built from scratch in new and untested locations before the benefits could be realized. New kinds of organizations had to be created that were capable of designing and running such factories. Only then did electrification show up in the productivity statistics, and in a big way.

Electricity was such a radical breakthrough that it required a new system-level solution. It decoupled energy use from its source, challenging deep assumptions that had been embedded in manufacturing for decades if not centuries.

Artificial Intelligence is of similar magnitude: by decoupling prediction from the rest of the decision-making process, it is reshaping how intelligence is accessed and applied. In turn, that is shifting where and how we as humans apply our own thinking to solve problems.

Just as with the rise of electricity, to fully realize the benefits of AI we will need completely new system-level solutions and even new kinds of organizations that we probably can’t envision today. Just think about how cars were vastly better than horses once widely available, but cars needed gas stations, good roads, and a whole new set of laws to function.

Which means AI will also take a long time to be deployed – probably decades. Technological change happens fast, but the social technologies needed to deploy it evolve slowly.

Three Case Studies of AI-Driven PredictionLet’s take a look at three case studies, explained in detail in Prediction Machines and Power and Prediction, of what will happen once we have access to abundant AI-generated predictions:

College admissionsSchool bus driversWeather forecastsCollege AdmissionsThe challenging, time-consuming process of applying to college can be reframed as a prediction problem: each university is trying to predict which of the applicants is most likely to succeed in completing their degree.

Now imagine if the predictions required to make admissions decisions were free and instantaneous. Admissions advisors could run an algorithm that told them with a high degree of confidence who are the best candidates.

The cost of applications might fall to zero since they don’t require human time to evaluate. Schools might not even need applications – perhaps they could simply access your online profiles (with your permission) and generate an admission decision based on that data.

The admissions process itself might reverse: instead of an inbound process of prospective students applying to certain universities, those universities could proactively reach out to people whom their algorithm suggests would make excellent students. Not only would this save a lot of people a lot of effort, it might even lead to a wider applicant pool of people who wouldn’t normally consider higher education.

To take this a step further, imagine if this approach was extended throughout a student’s college career. The algorithm could predict which tutors and supplementary classes they would need at various points to maximize the value of their education. Rigid rules such as “everyone follows the same curriculum” and “everyone does the same homework” could be replaced with far more personalized assignments precisely targeted to address their weaknesses.

School Bus DriversIf self-driving cars become fully automated, the job of bus drivers might seem an obvious candidate for elimination. But consider that bus drivers do much more than drive: they supervise a large number of kids, look out for and protect them from hazards, and maintain discipline inside the bus, among other responsibilities.

If the act of driving became automated, they might be able to spend much more time on these other, arguably more valuable tasks. That might elevate the job into a caretaking and educating role, which would require more training and higher standards but also might be better compensated.

The lesson, often repeated elsewhere, is that AI often automates a task, but rarely an entire job. If there is even one element of a job requiring human involvement, then a human must still perform it. And they can often use all the time that’s been freed up on higher value, more complex tasks.

Weather ForecastsOver the last few decades, weather forecasts have become far more accurate, timely, and precise. Many of us now depend on daily and hourly forecasts without a second thought, and they’re rarely mistaken.

But a weather forecast is a “one-size-fits-all” service. It is the same forecast for everyone living in a city or region. Imagine if those forecasts could be personalized at the individual level.

You’d be given a temperature forecast that took into account your personal sensitivity to humidity and wind. The prediction for rain would consider your personal risk of being caught outside without a jacket or umbrella, based on where you live and even what you’re wearing. Your personal weather forecast could advise you to make certain decisions – such as wearing different clothes, taking an alternate route to work, or bringing your plants in from the back porch.

This example illustrates that the barrier to being able to offer more personalized products and services is often automation. We could generate the personalized weather forecast described above today, but it would take too much human time to be practical.

If AI took over the process, we should be able to switch from generic, uniform rules to thousands or millions of individualized recommendations, on everything from weather to traffic to job-seeking to having good conversations.

AI represents the rise of a new source of competition for us humans. Not only do we have to worry about other people taking our jobs, intelligent machines will substitute for an increasing number of the tasks we perform as well.

At this point, you may be wondering, “How can I use these ideas to protect and advance my own career and life?”

There are five questions suggested at various points in these two books that I think are worth asking yourself:

1. Which rules I’m currently following could be replaced with a decision?The rules we follow throughout our days protect us from having to make too many decisions. But in protecting us, they also limit us. It takes perceptiveness and meta-cognition (the awareness of your own thinking) to even notice when you’re following a rule.

If you’re an investment analyst who researches new companies and writes reports with your findings, what rules are you following in the preparation of those reports? Do you always start the same way, looking at the same sources of data, evaluating them with the same criteria, and presenting your results in the same format?

Those are all rules. How can you use AI to customize or automate one or more of those steps so you have the ability to make a more finely-tuned decision about how to execute them?

2. How can I enhance my judgment using AI prediction?Now that prediction and judgment have been decoupled, you will probably have to do much less prediction, but make more decisions with a greater degree of judgment. How can you use the newly plentiful supply of predictions to hone your decision-making skills?

For example, if you’re a graphic designer, you no longer have to create a new image from scratch hoping or guessing that it will be what your client wants. Instead, you can generate dozens of options with the click of a button. Could you apply your design skills to create a step-by-step process of iteration that includes your client, bringing them into the design process as a value-added service?

Imagine an immersive viewing room where AI-generated images move slowly across the walls in succession. Thematic music fills the air to create a sensory experience. The images get tweaked and tuned in real time based on which images most resonate with them, using eye-tracking technology and heart rate variability data. By the time they step out of the viewing, they have an image in hand which is better than you could have created upfront.

3. How can I find and access new, unconventional sources of data?One of the clearest lessons of recent AI models is that it takes an enormous amount of data to train them. There are serious concerns that humanity’s total supply of data will only last so long. We’ll have to constantly find and create more.

Given that fact, how can you put yourself in a position of securing access to new, untapped, hidden, secret, or quickly changing information? Perhaps it’s data about the natural world, such as how forests are growing or the movement of deep-sea oil reserves. Maybe it’s highly sensitive data, like people’s deepest fears or secret preferences (acquired ethically I hope).

All that data can be stored in a system of personal knowledge management – which I call a Second Brain – so you always have it ready to feed into any AI (or human) you’re interacting with. We offer in-depth training in how to build such a system as a best-selling book and a self-paced course.

Until AI can directly access the full richness of reality, both in the physical world and the psychological one, it will depend on us to learn and improve its understanding of the world.

4. What is the smallest number of decisions I can make to achieve my mission?This one may seem counterintuitive, but in the future, any decision that requires a human in the loop will be far slower, more expensive, and more complex (and maybe in some situations even more risky) than one handled purely by AI. Decisions that can be made solely by AI will happen at AI speed, whereas human decisions will have to proceed through the much slower world of human minds, relationships, and institutions.

Given this new predictive superpower we now have access to, there will be tremendous value in structuring an activity so that it requires as few human decisions as possible.

Imagine two non-profit microfinance organizations working to end poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa. They are both well-intentioned, well-resourced, and good at what they do. But one of them has automated the process of deciding who should be given a micro-loan using AI.

Over time they are likely to make lending decisions faster, improve the accuracy of those decisions by incorporating data on the results, changing how the staff operates to further improve the algorithm, and using flexible lending criteria that takes into account more variables than any human could consider.

This AI-driven nonprofit could well achieve a more effective, fair, and customized lending portfolio than its counterpart, leading to lower costs that further frees up funds for more lending. By minimizing the surface area of their organization that is exposed to humans, and thus the decisions that humans have to make, they could greatly accelerate their impact.

5. What information, if supplied to AI, would allow me to make better predictions?Predictions are like precisely engineered products, finely tuned for very specific purposes. Although we are early in the AI revolution and a few general-purpose platforms like GPT-4 are dominating the industry, that is likely to change as more companies enter.

Even if it doesn’t, there will always be a need for us to provide the context and details the AI needs to make a prediction. This is why almost any ChatGPT prompt can benefit from more rules and guidelines, specific details, background context, and examples for how to understand what you’re asking.

Most of our information management tasks, from reading to notetaking to file management to content curation to social media, will have to change in a world shaped by AI. We’ll need to think about the apps and platforms we use to orchestrate all that information as a system, and consciously design it to feed us just the right information we need to craft the next AI prompt.

The better the quality of the data you have access to, and the easier it is to access it, the more you will find yourself empowered and unleashed by AI, rather than threatened by it.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post The Rise of Prediction Factories: How AI Allows Us to Replace Rules with Decisions appeared first on Forte Labs.

June 5, 2023

Beyond Perfection: How AI Unleashes Creativity by Lowering Our Standards

Imagine a product manager sitting down with his team on a Monday morning to plan the next week. The main item on the agenda is the decision of whether to create a mobile app for their e-commerce website.

The team quickly gets excited about the idea, imagining all the possibilities it could entail. They propose features like personalized shopping recommendations, integrations with social media platforms, multiple payment options, and in-app notifications about releases of new products.

But our product manager is starting to feel uneasy.

He has trouble identifying even for himself what the problem is. It all seems too much, too fast. There are too many unspoken assumptions being made and too many sky-high expectations being formed. He knows better than anyone how much all these features are going to cost, and how long they’re going to take, and wants to test some basic assumptions before committing to a full-fledged mobile app.

He knows he has to say something.

Why Quality Is Sacrosanct But Shouldn’t BeOur product manager doesn’t dare say “I think we need to do this at lower quality first.”

Quality is sacrosanct in the modern workplace. You’re never allowed to say you’re going to deliver something at 70% quality, or 50% quality, not to mention 20% quality. The unspoken rule is that you always do “your very best.”

And yet, we never really follow this rule, do we? What percentage of the tasks you complete are executed with maximum effectiveness? How many of the projects you take on reach their full, unmitigated potential? How much of the work you do is the best it could possibly be?

I would argue that that number is close to zero. It has to be, because the closer you get to the mythical 100% quality mark, the more costs skyrocket. It might take you as much time and effort to go from 90% to 95% quality as it took you to go from 0% to 90%. And it might take you that much time again to go from 95% to 99%. And there probably is no such thing as 100% perfection.

In other words, quality is an asymptote when you take costs into account: it can only approach 100%, but never reach it. And the closer you get to that 100% standard, the more costs grow exponentially.

I think we know and understand this tradeoff at an intuitive level. All day long, we make such tradeoffs fluidly:

When sending quick emails to close colleagues you settle for a lower quality level versus an email sent to an important clientWhen giving presentations to the Board of Directors you put a lot more shine and polish into your slides than when running the weekly standupA piece of writing you know will be published nationally in print will receive a lot more editing attention than something going on your personal blogWe also do have ways of communicating to others that this tradeoff is being made. We say things like:

“Let’s make a basic prototype and test it before going to manufacturing.”“Let’s put up a rough landing page to gauge interest before building a full website.”“Let’s shoot a concept video on a smartphone before hiring a production crew.”“Let’s mock up this app feature before putting it into production.”“Let’s do a dry run of the presentation before getting on the Zoom call.”We have a whole vocabulary of terms and expressions to convey that we are going to do something at a lower quality than we could otherwise achieve, in order to save time, minimize expenses, mitigate risk, or test assumptions.

Notice how each of the terms above communicates some version of “Don’t judge this too harshly or nitpick details – it’s just a rough draft.” This language is meant to set the right expectations so you have permission to experiment with something you don’t know is going to work. This loosens the usual standards and conventions you operate under by asking your audience to consider the big picture rather than obsess over some tiny error.

What all this means is that we are constantly making tradeoffs about how much quality we can “afford” for a given task, document, deliverable, project, or goal. No unit of work can escape this tradeoff – it applies to the shortest email you answer to the grandest goals you have for your life. All we can do is move up or down the quality/cost curve.

But there is something missing from the diagram above: quality is not just a single curve.

Consider the following question: Which is higher quality – a lawn mower or a cold brew coffee? That question makes no sense. We have to compare similar items for quality to even apply.

Well, how about a Toyota Camry versus a Tesla Model 3? You might jump to say that the Tesla is obviously better. But it depends on the situation. If you’re a first-year college student living in a dorm on a shoestring budget with no access to an electric charger and afraid of break-ins in a new city, then the Camry is better along nearly every dimension.

And that is the word we need to unpack: dimension. The “quality” of a product isn’t just one dial that gets turned up or down. There are multiple dimensions of quality, each of which can be dialed up or down independently. For example, a car can be judged by its:

HorsepowerMaximum rangeAesthetic appealCarrying capacityCost of ownershipAmenities and featuresAnd many other criteria…Each brand and model of an automobile has a different combination of these dimensions they maximize, minimize, or satisfice on in order to appeal to a target customer. Different kinds of customers value certain dimensions of quality differently, which is why we have a thriving marketplace of numerous automakers, instead of a winner taking all.

Obvious, right?

Now consider how this idea applies to our digital creations – the websites, reports, slide decks, code bases, and pieces of art and music we produce. Let’s take a piece of writing for example. It might be judged on its quality along the following dimensions:

Density of insightEntertainment valueSpecificity and detailPracticalityStorytellingClarityThere are many other criteria we could use, but let’s take those 6 as a starting point. Once you break down the concept of “quality” this way, you can see that individual pieces of writing aren’t better or worse than each other – they are different, rating higher or lower on each of these dimensions of quality.

A tweet probably beats out an in-depth essay when it comes to density of insight but loses miserably on specificity and detail. A how-to article wins when it comes to practicality, but likely falls short with its storytelling.

This kind of comparison applies even to highly similar pieces of writing. Imagine two journalistic articles covering the same story, such as an oil spill off the Alaskan coast. They might rate the same on specificity, practicality, and clarity, but if one is told in a more entertaining way, that single superior dimension of quality might differentiate it from the other.

This effect is magnified on the Internet, where even a slight difference in just one dimension of quality can mean the difference between relative obscurity and viral growth. That’s because there are no barriers to what people can access online, which means a huge majority of their attention tends to flow to a tiny percentage of all the things that get posted online each day.

The Power of Knowing Which Dimensions MatterFor a given digital creation, we have control over which dimensions of quality to invest our time and effort into. It’s not random.

When working on a piece of writing, for example, you could ask yourself: “Which dimensions of quality are most important for this piece right now?” In most cases, there are only one or two that truly matter, and the others only need to be “good enough” or don’t matter at all.

For example:

For a “how to” article explaining how to use a piece of software, the quality of the storytelling probably doesn’t matter as much, whereas clarity is paramountFor a thought leadership piece, the level of insight is of utmost importance, whereas the specificity might not matter as muchFor an “elevator pitch” for a new business idea, the length needs to be as short as possible, whereas the practicality might not be important for nowOnce you see that the quality of any output is made up of multiple dimensions and that typically only one or two truly matter, you are free to spend most of your time and attention on only those dimensions. And not only are you free to, that is what you must do if you want any chance of standing out.

In contrast, a guaranteed way to get stuck and bogged down is to try to maximize many dimensions at once. That isn’t possible or necessary, since a given piece of writing can really only make one promise: a clearly explained idea, an engaging story, a practical series of tips. Therefore, any effort you spend improving the lower priority dimensions is not only wasted, it might even interfere with and obscure the ones that matter.

This is another way of saying, “Not all aspects of a piece of work matter equally.” By taking opinionated stances about which ones do matter, and pouring all your time and attention into them, you have a chance at “winning” the attention game along a dimension that no one else can match.

The Pitfalls of Defaulting to High QualityIf all this sounds reasonable, why don’t we do it?

I’ve long noticed that most people tend to have a default level of quality that they get stuck on, like a car stuck in a certain gear. It’s like a habit – a sticky set of behaviors and personal standards that are entwined with their identity, and thus difficult to change.

It’s easy to see why defaulting to a low level of quality would be limiting to one’s career and life – it will be hard to get that job you want, much less keep it, if the output you produce never reaches a high enough level of quality.

It’s much more difficult to see how being stuck at a high level of quality can be just as limiting. In fact, in my work with high-performers, this is one of the most common limitations keeping them from taking the next step in their careers and businesses.

Let me explain.

For any given profession or kind of work, there is usually a “standard of quality” that people hold themselves to. For example:

A graphic designer defaulting to a high degree of quality will insist that every graphic asset that leaves their desk be highly polished and ready for printingA writer defaulting to a high level of quality will refuse to send in their draft or manuscript until it perfectly meets their vision for what they want to express to the worldA software engineer will continue refining her code until every line has been thoroughly documented, tested, and validated to the highest standards of qualityAgain, notice that each of these cases describes a respectable, admirable professional. Such people are already rare! How unusual is it to encounter any high-quality piece of work anywhere? It is an accomplishment to reach such heights, and relatively few ever will.

But…if you have reached those heights, the very attitudes and skills that got you there are likely now holding you back. Here’s why: not everything can or should be high quality.

In fact, most things most of the time should not be. Why? Because it’s so damn expensive. If you insist that every. single. piece. of work that leaves your desk (or computer) with your name attached be at the highest level of quality you are capable of achieving, several increasingly severe consequences will start to happen.

First, over time, you’ll produce less and less.

You won’t have as much time to obsess over every detail and polish every facet as you get older. You may have a spouse and kids and a dog and all the responsibilities those wonderful beings entail. Your metabolism will slow down and your energy levels will go with it. This is just how life works. You won’t have the same boundless energy and vast swaths of free time in the future as you had in your youth.

Second, you’ll be limited to individual contributor positions.

As long as you identify solely as a craftsperson – as the expert who is always there on the workbench or at the drawing board or in the studio – that’s where you will remain. The privilege of being in those places doing the work you love will slowly turn to resentment as you realize you have no other choice. There is nothing you will grow to hate as much as something you used to love.

Third, you’ll be limited in the scale and impact of what you can create.

Any significant work of art, culture, engineering, or business requires other people to reach its potential. And not just a few people you personally know – a lot of people in far-flung places, most of whom you will never meet. Even for something as seemingly solitary as writing my book, I can count over two dozen people who were directly involved, and there were probably hundreds more indirectly involved. Working with others is challenging because they will never do it quite as well as you. But you have to learn to live with that if you ever want to manifest a grand vision.

Fourth, you’ll be under-compensated and under-appreciated.

The world doesn’t pay experts very well. Related to all the points above, as long as you have to control every aspect of your output, you’ll never receive the financial rewards and respect you deserve. You’ll be stuck producing exquisitely crafted but small, limited works of art that someone else will find a way to commercially exploit, likely leaving you with peanuts.

The paradoxical conclusion of all this is that, for the highest-performing professionals at the top of their game, the bottleneck to their growth is in learning to lower their standard of quality.

At first glance, it would seem easy to simply not try as hard and stop before you’ve brought something to perfection. But it’s hard for several reasons.

First, as I mentioned previously, our identities are closely tied to the default level of quality we are most comfortable with.

We know how to reliably reach our favored level of quality. It’s comfortable, predictable, and brings expected rewards. Many of us have built entire identities around the results we produce: we are the “kind of person” who “does great work” and are thus determined to never fall below that standard. Letting go of that standard can feel like letting go of who we are.

Second, delivering at a lower level of quality is not just a matter of stopping when you reach a certain point. It requires you to understand which dimensions of quality can be sacrificed, and which still need to be maximized.

You might make hundreds of micro-decisions over the course of producing a document or deliverable. For each decision, you have to become more sensitive to which dimensions of quality it is improving, and whether that dimension matters for the current iteration you’re working on. You have to spend more time thinking at a “meta” level, considering questions such as how long each feature is going to take, which risks or other consequences it creates, and which prerequisites depend on which others.

For a rough-cut concept video, do you really need title screens, precise editing, cinematic background music, and maximum resolution, or can any of those be saved for a later iteration? For the first round of photo proofs, do you really need touch-ups, color grading, and cropping, or does only one of those matter until you gather more information? To answer such questions, you have to get so clear about precisely which assumption you’re currently testing, exactly which information you’re trying to surface, or which hypothesis specifically you’re validating.

Third, working at lower levels of quality surprisingly requires more advanced communication and collaboration skills.

Other people and stakeholders have to be ready to receive the “quick and dirty” draft you’ve made, which means you need to prepare them in advance. It’s of no use to deliver it in half the time if they aren’t ready and it will just sit around collecting dust. The way you communicate has to change because you have to calibrate the expectations of your collaborators so they consider the big picture instead of zeroing in on some inconsequential detail.

Fourth, you have to get much, much better at receiving feedback.

This is a whole collection of skills within itself: how to ask for specifically the kind of feedback you need, how to ask follow-up questions to discover what people really think, how to convey which kinds of feedback aren’t helpful, how to decide who to get feedback from and in what form, how to document and structure that feedback so it’s helpful, how to implement what you’ve learned without getting discouraged or losing your vision.

And fifth, all the points above require greater emotional intelligence and self-awareness.

Each attitude or skill I’ve mentioned is about embracing change, and even accelerating it, as a means of learning faster. It turns out that in order to learn faster, you have to expose yourself: to people’s opinions of you and your work, to the consequences of mistakes and failures, to the disappointment of a promising new experiment not working out. You’re going to need more emotional fluidity to be able to pivot abruptly from one promising direction you may already be invested in, to another more promising one.

Moving From Quality to FidelityAll the ideas and observations I’ve offered above point to one glaring need for modern knowledge workers: to replace the concept of “quality” with a more subtle and sophisticated one: fidelity.

Quality is an industrial-age idea. It comes from a time when society changed slowly, business was about making something strictly uniform, and we could expect to spend our careers in one field or even one company perfecting our craft.

But all of that has changed. At every level, our society and politics and economy and culture are all shifting far faster than ever before, and in more unpredictable ways. Quality is no longer about sticking faithfully to a timeless process passed down through the generations. It depends instead on your ability to maintain situational awareness about your environment and adapt your thinking and behavior to match it.

The only way to maintain such situational awareness is to constantly test and probe your environment to discover what is happening and why. Such tests have to be low-quality because they have to be fast.

You can’t spend a year building a mobile e-commerce app, because the e-commerce landscape will look completely different in a year and your hypothesis will be obsolete, even if it was correct! You can’t spend months artfully crafting your take on an emerging trend, because, by the time you publish it, most of the value of taking an early stand on it will be gone.

The word “quality” has a moralistic connotation that implies more of it is always better than less. That’s why we need to let go of it. It’s time to embrace fidelity instead.

The word “fidelity” means “faithfulness,” as in “How faithful should this deliverable be to the ultimate version of what it could be?” Sometimes, the answer may be that whatever you’re creating demands the highest levels of fidelity. If you’re at the end of a major project for example, and it’s time to deliver the final product to a client, it’s probably wise to maximize fidelity.

But fidelity is also a morally neutral term, conveying that more is not necessarily better. There is tremendous value in being able to produce rough, early, unfinished, unpolished experiments, especially when speed and adaptability are the top priorities.

If you’re early in a project, or there are still a lot of unknowns, or you’re trying something new and risky, then working at low fidelity might serve you better. You can save tremendous amounts of time and expense, not to mention avoid huge risks and pitfalls, by creating something rough and ready and then iterating from there.

How can we use this new understanding of fidelity to increase our speed?

By giving ourselves permission to reduce the fidelity of whatever we’re creating. To dial it down to the absolute minimum needed to answer only the next, most important question we’re facing. To focus all our attention only on the next bottleneck, and ignore everything else.

Using AI For Low-Fidelity PrototypingThere is a special place for Artificial Intelligence when it comes to creating low-fidelity prototypes.

In a previous piece, I wrote about my experiments using ChatGPT to summarize books, my conclusion was that there wasn’t much value in the book I was trying to summarize. It didn’t answer any open questions for me, or solve any problems I’m facing.

This might seem like a failed experiment, and it was. But there is a lot of value in failed experiments – they reveal what isn’t true, doesn’t work, or isn’t worth pursuing.

Why was the conclusion I reached so meaningful? Because writing a summary of this book had been on my to-do list for 5 years. It was a “marginal” task that I had some interest and desire in doing, but not enough to actually commit the time and energy needed. Looking at the many tasks I’ve accumulated in my task manager over the years, most of them fall into that category: potentially important enough to keep around, but never urgent enough to actually do.

By using ChatGPT to make a low-fidelity summary that was just good enough for me to get a sense of the book’s contents, I was able to test the assumption that it would be relevant to my needs much more quickly than it would have taken otherwise. In a sense, I was able to create a “rapid prototype” of the summary that wasn’t good enough to publish but was good enough to help me decide whether this task was worth doing at all.

I suspect this may be the greatest impact of AI tools in the short term: allowing us to quickly create low-fidelity, 80/20 prototypes to test assumptions about what we should do next and get an idea of what a final version might look like if we do.

Imagine this scenario: you have the ability with the mere click of a button to have AI complete any task on your to-do list at 50% of the quality that you’d be able to do yourself. You can do so almost instantaneously, without risk or penalty if it goes wrong, and at no cost other than a couple of minutes and an affordable monthly subscription.

Let’s say you run “AI tests” of 50 tasks on your to-do list, revealing that:

20 aren’t worth doing at all15 can be executed completely by AI without your involvement10 need to be restructured and broken into pieces for AI to then complete with your supervision5 require your full and undivided attentionThat would be a tremendously powerful breakdown to have at your disposal. It basically represents a plan for how to tackle a broad spectrum of tasks, which would replace a large amount of cognitive effort you would otherwise have to spend yourself.

Many of the “intermediate” stages of our workflows include this kind of categorization, analysis, chunking, decision-making, and planning of tasks. By replacing these intermediate stages with AI, I think our time and attention will get freed up to spend in two places: the very beginning of our creative process – deciding which information to capture as inputs in the first place – and the very end of our creative process – polishing and refining the final product to perfection as only humans can.

This use case alone might dramatically free up our time since we all spend a fair proportion of our days doing tasks that don’t require our full attention. But there is another, even more interesting and profound way I think we’ll use AI.

It arises from the fact that there is an inherent amount of uncertainty surrounding much of our work. We don’t know in advance which tasks require 100% quality, 50% quality, or are worth doing at all at any level of quality. Often you don’t understand the nature and potential value of a task until you’re already doing it, as with my example of summarizing a book.

Reducing that uncertainty is another area where I think AI will make a major impact. If you can have it complete a task at 50% quality at virtually no cost, that should be enough to eliminate a lot of uncertainty about whether it’s worth doing and what the best approach is.

You might ask it to generate a mockup of a webpage you’re considering making, or a batch of test code you’re thinking of writing, or an outline for a course you’re thinking of designing – since this labor is free, there’s no downside in trying it, and only upside if it happens to produce something you can use.

Once you’ve seen a rough, low-fidelity version produced by AI, and made the decision to green-light the full-fidelity version, you might need to take it from there to bring it to a level where it can be published. But even in that case, you’ve gained a tremendous benefit: you’ve been able to visualize many more (and weirder, more divergent) scenarios and consider more (diverse, unusual) options before committing your precious time and attention to one.

This approach also gets around a lot of the personal baggage and identities that we attach to a certain standard of quality. We won’t be as attached to the work that AI does on our behalf and thus can tolerate a much wider range of fidelity than we would ever accept from ourselves.

By replacing the loaded term “quality” with the more precise “fidelity,” by focusing all your attention on the aspects of the deliverable you’re working on that matter most, by treating everything you do as a continuous iteration, and by using AI to rapidly test new directions before committing to them, you’ll open up a world of possibilities in which emerging technologies are an ally of your creative vision, not an impediment to it.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post Beyond Perfection: How AI Unleashes Creativity by Lowering Our Standards appeared first on Forte Labs.

May 22, 2023

The Extended Mind: Reimagining the Nature of Intelligence