Tiago Forte's Blog, page 6

September 25, 2023

When You Should Switch Your Second Brain App (And When You Shouldn’t)

I’ve had some form of a Second Brain (a personal system of knowledge management) for a couple decades now, and during that time it’s been hosted on four different platforms:

Paper was sufficient for most of my school years when I didn’t have my own computer (and wouldn’t have been allowed to use one if I did). Microsoft Word was a good fit for my late high school and college years because it was the only text-based software I knew of, and it allowed me to gain fluency in an app I’d be using for years of further schooling. Google Docs was ideal during my 20s when I was living and traveling abroad and needed a “digital nomad” solution that always saved everything to the cloud.Evernote has been a great companion for the last decade of my career when I needed a simple, mobile-friendly solution that allowed me to focus on content creation.

What jumps out at me as I look back at this timeline is that each season of my life has benefitted from a notetaking medium that complements it. Each season puts different demands on us, imposes certain constraints, and highlights certain weaknesses – the tool you use to manage your life should compensate for those weaknesses while amplifying your strengths.

In general, you don’t want to switch notes apps too often, since making such a move invariably consumes a huge amount of time and energy that is then unavailable to actually move forward your priorities. Switching Second Brain apps is akin to changing the water heater in your home, the transmission in your car, or moving to a new bank – something to be done as infrequently and reluctantly as possible, only when circumstances demand it.

This is why I think the best time to switch apps is at major life transitions – changing jobs or careers, moving to a new city, getting married, having kids, buying a house, etc. You’re already expending a huge amount of effort and upending all your habits and routines to make such transitions anyway, so you might as well use that opportunity to retool as well.

By timing your digital migration to accompany a major life transition, you ensure that you’re doing it for the right reasons – not because you’re bored, or craving distraction, or because the hype for a new hotshot app is too powerful to resist. No, you’re changing your support systems because your life is changing, and your Second Brain should mirror that change.

When NOT to move appsThere are three situations in which people commonly switch their Second Brain apps that I think are ill-advised.

1. When your existing app “breaks”One of the most common reasons people decide to switch to a new notes app is when their existing one “breaks.” Often this decision is made spontaneously, in a moment of acute frustration at some unmet expectation, which is the first red flag. You wouldn’t move homes or trade in your car based on a momentary annoyance, would you?

But there is a more fundamental reason why this isn’t a good reason to make a switch: in virtually all cases, the app isn’t truly breaking – it’s probably just a little slow, or suffering a temporary glitch, or maybe at most they eliminated one of your favorite features.

While I know these things can be frustrating, changing your digital home base entirely is almost always an overreaction. I guarantee whatever new app you switch to will have its own fair share of glitches and problems, and now you’ve paid the tremendous penalty of changing all your existing habits and workflows.

The same goes for price increases – I cannot imagine a worse reason to overhaul your digital life than a nominal price increase. If you are using your existing platform at even 1% of its potential, the time savings it is creating exceeds that additional expense many-fold.

2. When embarking on a new projectAnother common situation in which people feel the need to move to a new platform is when embarking on a new project or other endeavor. It’s understandable to want to start with a fresh, clean slate when starting something new, but I think this is almost always a mistake.

Here’s why: when a project is just starting, you don’t have time to adopt new tooling. Unless you are building a particle accelerator, or something else highly technical requiring exotic technology, your tools and infrastructure are almost never the bottleneck to your progress in the early days.

Since your choice of notes app is not your bottleneck, not only will changing it not help, it will probably just distract you from the necessary next steps that would actually represent tangible progress. Endlessly reevaluating your software options is usually just a form of sophisticated procrastination.

3. When a new paradigm of notetaking arrivesThe third most common rationale for moving Second Brain apps is when a new paradigm of notetaking or knowledge management emerges.

Back in the day, as soon as cloud-based, real-time word processing arrived in the form of Google Docs, the whole concept of editing static Word docs saved to your hard drive immediately felt hopelessly outdated. When Evernote arrived, my previous practice of keeping all my notes in one giant Google Doc quickly felt like something from the Stone Age.

More recently, the paradigm of “digital file cabinets” embodied by apps like Evernote – in which notes are individual documents stored in discrete containers such as folders – is giving way to a new wave of “networked” or “linked” or “graph-based” tools.

The network is the dominant paradigm of the Internet, and that paradigm is now invading and transforming even our most personal, private repositories of information via apps like Obsidian, Roam, Logseq, and Tana.

This might seem like the perfect time to jump ship and ride the new technological wave, but in most cases, it’s not. To understand why, you have to understand when it is desirable and advantageous to be at the forefront of an emerging technology, and when it is undesirable and actively harmful.

How new technologies matureThe Gartner Hype Cycle is a well-known model for how new technologies enter the marketplace and change our behavior. I encountered it early in my consulting career, and it’s shaped how I’ve seen technology-driven change ever since.

Put simply, a Technology Trigger (at bottom left) is a new, breakthrough technology that gets invented. It quickly ascends the Peak of Inflated Expectations (top left), as the hype around its potential escapes all bounds of reason (“OMG it’s going to change everything!!!”).

But that peak always overshoots, and leads soon thereafter to the Trough of Disillusionment (center bottom) as the reality of the technology’s limitations sets in. As the trend continues maturing throughout this roller coaster, it eventually climbs the Slope of Enlightenment as the practical use cases become more clear.

Finally, the new tech matures and enters the Plateau of Productivity, where it can start to become integrated into our everyday lives and, therefore, tangibly improve our productivity and performance.

Perhaps not surprisingly, that Plateau of Productivity is the part I’m most interested in. It’s counterintuitive in a world where technological progress often makes headlines, but it is only mature technologies that have been around for some time that truly make a difference.

As just one example (recounted in the book Power and Prediction which I summarized here), twenty years after the invention of the lightbulb, only 3% of US households had them. It took another two decades for it to reach just half of US households. There needed to be a series of improvements and supporting innovations to make the lightbulb a mature product ready to be installed widely in people’s homes. The most radical breakthroughs take the longest time to spread.

What this means for us individually is that you have to consciously resist rushing immediately to the cutting edge of new technological waves, because at the cutting edge you will find mostly noise, hype, scams, outlandish promises, and unmet expectations.

To be clear, it’s hard to resist the siren song of new tech, especially if you are an early adopter who enjoys trying, exploring, and testing new things. That’s fine to do as a form of entertainment, learning, or experimentation, but not when it comes to the basic, foundational infrastructure that runs your life.

If you use a second brain app like I do – as an extension of your mind and the engine of your responsibilities – you cannot afford to upend it all just because you have FOMO about a sexy new app someone is raving about on social media.

Here’s the bottom line: the right time to adopt a new paradigm of notetaking is when the paradigm is mature, not when it’s just emerging. Because we’re talking about a basic utility here, the most important feature is reliability.

And the products that tend to be most reliable are the ones that are mature and proven, with all the kinks having been worked out long ago.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post When You Should Switch Your Second Brain App (And When You Shouldn’t) appeared first on Forte Labs.

September 11, 2023

What It’s Like to Hire a Speaking Coach: Discovering the Power of Spontaneous Self-Expression

Around the time my first book Building a Second Brain came out in June 2022, I started looking for a speaking coach.

I had just delivered my first keynote to a large audience at World Domination Summit, followed soon thereafter by my Google Talk. These experiences had been not only fantastic promotional opportunities but fulfilling and meaningful for me personally as well.

There is nothing quite like standing on stage and delivering a message you deeply believe in to an enthusiastic, roaring crowd.

At the same time, I could see clearly that “winging it” wasn’t a sustainable strategy for future speaking gigs. I’d been lucky to be offered a couple of valuable opportunities, but I wanted to start pursuing speaking more purposefully, as a skill and a craft that could serve me for decades.

I always like to start new projects by listing my intentions, and this time was no different. I decided I had six of them:

To build a world-class speaking business based on my BASB messageTo use speaking to promote sales of both my book and our courseTo connect with people on a human level and inspire them to greatnessTo generate a new source of revenue for the businessTo connect with like-minded thought leaders and learn from themTo master all the major elements of speakingIn other words, I wanted to use my new book as a springboard to launch a full-fledged speaking career, both to grow the business and for personal enrichment.

After interviewing several candidates, I decided to work with Michael Gendler, co-founder of Ultraspeaking. I liked his attitude and philosophy toward speaking, admired the education business he’d built around that philosophy, and the fact that he lived nearby in Los Angeles was icing on the cake.

Here’s what I learned and how I changed as a result of that collaboration.

Speaking as self-expressionI came in hot and heavy myopically focused on learning how to book corporate keynotes, nail big speeches, and maximize my profitability per hour. Like any good coach usually does, Michael quickly pumped the brakes and started asking me some basic questions about what I truly wanted.

I’ve often said in the past that the main job of a consultant is to repeatedly ask “So what are you really trying to accomplish here?” since much of the time we tend to be deep in the weeds on one narrow pursuit.

This turned out to be a fruitful question because depending on what I was trying to accomplish, there were usually far better ways of accomplishing a given goal. Looking at my list of six intentions above:

If my goal was to promote sales of my book and course, it would be far more efficient to create online content that serves that purpose day and night, rather than flying to far-flung locations and talking to small groups of people.If my goal was to connect with people and inspire them, I could do that much more easily via local meetups, doing my own coaching, or simply hosting workshops on Zoom.If my goal was to grow the business and increase revenue, there are many other ways of doing that that don’t require trading my time for money.If my goal was to connect with other thought leaders, grabbing coffee with them is probably more effective than speaking on stages.This exercise revealed something I’ve often noticed about setting intentions: if you have too many of them, no single one is important enough, which means none of them end up being fulfilled.

The intention that couldn’t be fulfilled any other way, and that stood apart, was to master all the elements of speaking. But that isn’t an end in itself. Michael and I spent a good amount of time digging into the root of that desire. The answer we arrived at was obvious as much as it was surprising: self-expression.

Michael’s philosophy, as embodied in the Ultraspeaking courses, is that speaking in public isn’t just about delivering corporate keynotes. It’s about self-expression, a much deeper and broader need that everyone can benefit from, whether it involves speaking up in a meeting of three people, communicating confidently over a group dinner, or simply being able to spontaneously share what you’re feeling in a conversation with one other person.

Ironically, self-expression is also at the root of my work. The reason I believe that curating and organizing and synthesizing information is worth doing is because of what it allows you to express: a message, a story, a cause, an idea. We came full circle and realized that my desire to improve at speaking was rooted in the same core desire that drives all my work: to communicate and connect with people more deeply and authentically.

With this clarified, much simpler intention in mind, we created an action plan with six main elements:

How to make public speaking an opportunity for me to become an amplified version of myselfHow to bring playfulness, silliness, and humor into my speakingHow to make my speaking more variable and dynamicHow to speak more spontaneously, with minimal notes or preparationHow to structure prepared speeches for larger, more formal audiencesHow to identify the main points of my message, and illustrate them with personal storiesMy default approach to speaking is to be overly prepared, which tends to make me too rigid, caught up in my head, and obsessed with hitting every single point. Our action plan was designed to make the whole experience much more spontaneous, and thereby both reduce the burden of preparing my talks while also allowing me to connect with my audience as a human being.

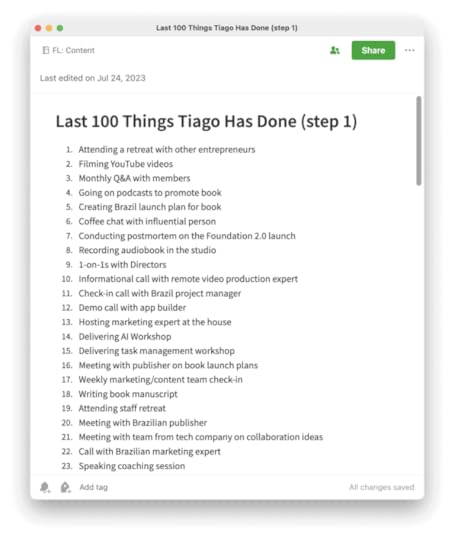

Identifying my main ideasWe met for each session in the studio at my house, and in our second meeting, we began to identify the main messages that I wanted to communicate.

You might think that I already knew exactly what my message was, but the problem with being immersed in a subject every day is that it’s almost impossible to avoid losing the forest for the trees. The idea of a “Second Brain” is so expansive and multi-faceted that I could potentially address any one of a dozen different aspects of it.

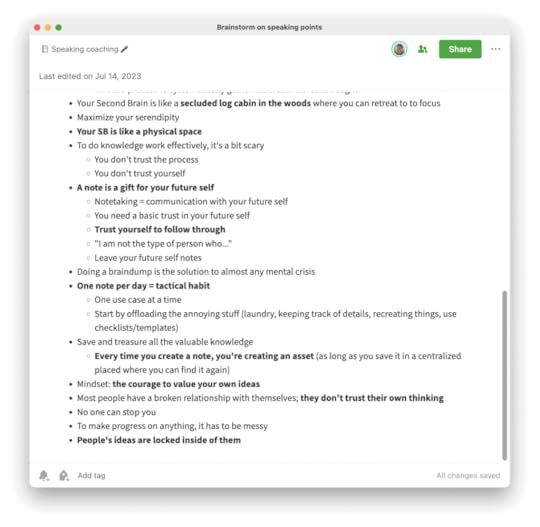

We did a live brainstorming session, with Michael repeatedly asking me questions and prompting me to expand on certain points while he took notes. The result was a fascinating brain dump of ideas that could serve as takeaways from any talk I gave. Here is a page from Michael’s notes, which he shared with me afterward:

Seeing my own thoughts reflected back to me through another person’s perspective was tremendously helpful, allowing me to notice that certain subtle and complex topics I found interesting were unintelligible to others, while others I found basic and obvious were eye-opening.

I digitized those notes and, on my own, bolded the points I thought were substantial enough to support a talk. These became an “idea bank” I can turn to any time I need to deliver a speech.

Michael also helpfully summarized what he thought were my most salient and unique ideas in a follow-up email. Again, this is a priceless window into how someone not fully immersed in this topic views it:

Practicing spontaneous speaking

Practicing spontaneous speakingOnce we had a set of ideas that I knew enough about to speak on, I was surprised that Michael wanted to go right into spontaneous practice. I tend to follow rather thorough, overly detailed processes when creating new things, so going straight to delivery felt like an uncomfortable leap.

Michael set a timer for three minutes, asked me to pick any idea from our list, and before I knew what was happening, he said “Go” and I found myself talking. Without an idea where I was going and absolutely no outline or structure in my mind, I was pleasantly surprised that I could still make it engaging. In fact, I could quickly tell that it was more entertaining than if I had been sticking to a strict outline.

Michael set the timer again for one minute, and I went again, preserving some of the phrases and anecdotes that I sensed from the prior round had resonated the most. Finally, he set a timer for 30 seconds and had me do it one more time…and I almost instantly broke into tears.

With 30 seconds you don’t have time to plan, strategize, or even think. There is no room for narrative, logic, or reason. There isn’t even a beginning, middle, and end. It’s enough time to say one thing. One thing to leave an impression on your audience, to have them walk away different than how they walked in.

I wasn’t just repeating my talk; I was distilling it. Each round the energy and emotion I was trying to convey got condensed into a shorter, more compressed space. By the time we got down to 30 seconds, I was shocked to hear the following words erupt from my mouth like a long-dormant volcano:

“I am so tired of you fucking perfectionists!!!!!”

What I discovered in that moment was that there is a tremendous anger lying close to the heart of what I do. It’s anger at all the brilliant, unbelievably talented and creative people I interact with every day who are stuck endlessly organizing and optimizing their systems. To me, this is the greatest wasted resource on the planet – all the people who could contribute such amazing ideas and life-saving solutions to our world but can’t get out of their own way.

I initially got in touch with that anger in my first experience with anger work at a week-long course called Groundbreakers. Back then, it had come out messy, a new reservoir of energy being tapped for the first time. This time it was much cleaner, the rage flowing smoothly into a determination to do everything in my power to help people get over the fear and perfectionism stopping them from pursuing their creative dreams.

I don’t know if I will ever use this 30-second, anger-fueled, tearful style of speaking in the business world, but that wasn’t the point. The point was to remember that I have all the emotions flowing through me at all times, like a subterranean river, and that I can tap into any one of them whenever I need to. And that it is the emotion I am tapping into – in myself and therefore also in my listeners – that people will remember, not concepts.

After our three in-person sessions together and a couple Zoom calls to check in, I was ready to converge on all this experimentation and arrive at a final product. If you know me, you know I always try to arrive at a final product – a concrete artifact that distills the work I’ve done so that it lives on and remains accessible in the future.

The format of talks that Michael introduced me to was remarkably simple. It had only two elements – messages and stories – with each message having one or more stories to support and illustrate it. A short talk could constitute as little as one message with one story, or it could have multiple like this:

Message 1StoryStoryMessage 2StoryStoryMessage 3StoryStoryWhat I like about this format is that it is simple enough to easily keep in your head, can be expanded or contracted as needed, and it’s always obvious what comes next. I created a new note with two headings, and in a single page summarized everything we had identified:

I add “HQ” to the title of any note that I know will serve as an important hub for new projects in the future. This screenshot captures almost the entirety of its contents. I’ll add to it over time, but it already fills me with a tremendous sense of confidence knowing that I can hop in here and have a customized talk ready for any occasion in minutes, based on material I know like the back of my hand.

This is such a stark contrast to my previous process: spending many hours creating meticulously designed slides, avoiding outlining and practicing my talk until the last possible moment, realizing too late that I have too many slides and most aren’t necessary, and then rushing to fix it in a panic, leaving me in a stressed and anxious state of mind on the eve of my performance, while failing to practice more than once or twice.

I’m moving into a new season where my communication around BASB isn’t about conveying precise technical details. We now have multiple channels for that that are much more effective.

My role is to give people an impression – to express a feeling or an experience of what life is like with such a powerful force at one’s disposal. To share how much it means to me, what it enables and allows in my life, and what might be possible for them if they were to embrace it as well.

I wrote this article to integrate my own learning, but also to offer that same opportunity to you: if anything I’ve shared resonated with you, and it’s something you want for yourself, the next cohort of Ultraspeaking is now open for enrollment. I’ve asked Michael to make a special offer to my followers: You’ll get $100 OFF with the code TIAGO100. This is the most accessible, social, playful approach I’ve ever encountered for learning how to express yourself authentically.

If you’re interested in hiring Michael Gendler or his co-founder Tristan de Montebello for 1-on-1 coaching as I did, you can also inquire by emailing coaching@ultraspeaking.com.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post What It’s Like to Hire a Speaking Coach: Discovering the Power of Spontaneous Self-Expression appeared first on Forte Labs.

August 28, 2023

Surviving the Post-Pandemic Slump: How We Recovered From an 87% Drop in Profit

At the start of 2023, as I reviewed the end-of-year financial report sent over by our accountants, I had a stunning realization: our net income had dropped 87% in 2022 compared to the year before.

From an incredible 64% profit margin in 2021 we ended 2022 with a razor-thin 6%. The picture got even worse when we took into account the enormous growth in our subscriber base: revenue per email subscriber fell from $38 at the peak of the pandemic in spring 2021, to just $3 in fall 2022, a 92% drop.

I knew our business had slowed since the last several launches of our cohort-based course had been smaller than previously, but I had no idea the drop was this severe.

As I dug into the numbers, I saw that the COVID-19 pandemic represented an outlier: a huge surge in revenue for online courses like ours. As the pandemic subsided in 2022, people were returning to their normal lives, which didn’t involve spending hours a day on Zoom.

I thought we had hired conservatively, growing the team from 4 full-timers to 9 over the previous couple of years. But the fixed overhead cost of our staff combined with a precipitous drop in the revenue from our only product brought us to the brink of unprofitability, which is especially troublesome for an Internet-based business that is supposed to have high margins.

I met with the team, consulted a range of mentors and advisors, and decided to embark on a series of decisive actions to turn the company around. Six months later and I can confidently say we succeeded, though it was a hard road.

I’m sharing the story of what we did and why in the hopes that it will provide some ideas for other online businesses that have experienced the same downturn as us.

There were five main decisions and initiatives we committed to:

Changing our planning horizon to the short termCutting $27,000 in expenses and conducted 3 layoffsRecruiting facilitators so we could turn our attention elsewhereCreating multiple new revenue streamsChanging our policies and priorities1. Changing our planning horizon to the short termThe first shift we needed to make was rooted deeply in our culture: to temporarily shift the horizon of our thinking and planning from long-term and growth-oriented to short-term and revenue-oriented.

I’ve always tried to think as long term as possible, making decisions that would pay off years from now even if they seemed risky in the present, planting lots of seeds for future products and services, and not worrying too much about our spending.

These attitudes and assumptions had been baked into the company culture, and thus my first task was to communicate to the team clearly, in ways direct and indirect, large and small: now it’s time to figure out how to make money.

The book Double Your Profits in 6 Months Or Less (affiliate link) by Bob Fifer was the perfect antidote to my previous attitude of not caring about profitability, and I ate it up eagerly.

2. Cutting $27,000 in expenses and conducting three layoffsProfitability always has two main components – revenue and expenses – and expenses was the next place I looked. Costs have the benefit of being something you can cut immediately, whereas growing revenue always takes time.

In the ten-year history of the company, we had never conducted a wide-ranging cost-cutting initiative. In fact, for all that time we had always struggled to find new ways of spending money, given how high our margins were. It felt like an abrupt change in direction to review every transaction from the last six months looking for anything we could cut, reduce, postpone, or renegotiate.

That process took us about two weeks and resulted in $27,000 in expenses (much of it recurring) we could eliminate with minimal impact on the business, which you can read about in full here.

I also had to make the difficult decision to let go of three full-time staff members, as labor is by far our biggest expense. Our team shrunk from nine to six people, which meant we had to be even more selective and strategic about how to use our time for the decisions to come.

3. Recruiting facilitators so we could turn our attention elsewhereNext, we turned our attention to the revenue side. I knew that we needed to create new sources of revenue, but that any new product line would require my bandwidth, at least in the beginning as it started up.

The problem with that was that most of my time and attention was taken up teaching our live cohort-based course, Building a Second Brain. We’d hired “alumni mentors” for the last several years to serve as coaches and role models for new students, but now I needed much more from them. I needed them to teach and lead the cohort itself.

We decided to create a new role, BASB Facilitators, and significantly increase the authority we gave them to teach not just breakout sessions, but the main “live sessions” that made up the backbone of the program. We recruited some of our most experienced graduates, increased the support we provided to them, and placed them in charge of the core curriculum.

We’ve now relied on facilitators for a couple of cohorts, and have been pleasantly surprised by how quickly they’ve become self-reliant and capable of delivering the program. The feedback from students has been mostly positive as they’ve appreciated the wider diversity of perspectives, which has led me to step away from teaching the cohorts knowing our students are in good hands.

With the rapid decline of our cohort revenue, I knew that the only way back to profitability would be to find new sources of revenue.

We did a survey of all the available opportunities, at least a dozen in total. Here are the ones we decided to invest in and launch:

Publishing The PARA Method book using mostly existing content on the blog (totaling nearly $100,000 USD in book advances within a couple of months)Upgrading our affiliate program, including a new Recommended Tools page listing all our favorite SaaS tools, and establishing affiliate relationships with a dozen of our favorite courses (generating 4 figures recurring per month)Soliciting sponsored YouTube videos and newsletter placements, making use of the work we were already doing to produce high-quality videos and send out our free weekly newsletter (5-figures recurring per month)Turning our annual 2023 Second Brain Summit into a paid event, based on the value we knew we could deliver after hosting the event before (5 figures in revenue, plus ongoing sales of the recordings)Offering a new virtual workshop on How to Use AI for Your Second Brain, summarizing everything I’d learned over several months of immersion in the generative AI world (5 figures in revenue, plus ongoing sales of the recording)Creating an all-new BASB Foundation 2.0 course, applying everything we’d learned from YouTube to completely redesign and reshoot it (the relaunch generated 6 figures in revenue, and the course is now sold year-round)To summarize, within a few months we were able to create or massively upgrade six separate revenue sources, totaling multiple six figures ongoingly, using only the existing team and existing assets. Some of them brought in surges of revenue upfront via launches, while others provide a steady stream of recurring income over time.

This to me is one of the most remarkable aspects of information-based businesses: you have saleable assets just lying around everywhere. All it takes is some repackaging and repurposing and they can be turned directly into revenue-generating assets relatively quickly.

The core asset that makes the business viable is the aggregated attention of our subscribers and followers. As long as that relationship is strong, there are any number of needs and problems we can solve for them.

All these decisions and projects together have worked wonderfully, completely turning around the business and returning it to profitability. After losing money for the first few months of the year, the last few months have been some of our most profitable ever. Not to mention, our culture feels more supercharged and determined than ever as we tackled this crisis and resolved it through sheer ingenuity and hard work.

5. Changing our policies and prioritiesThe transition from 2021 to 2022 was the first time in the company’s history that we failed to grow. Instead, our revenue shrunk by 1/3, from about $3 million to $2 million USD.

I hadn’t realized up to that point how much of our culture, strategy, and mindset was shaped by this background expectation that growth was guaranteed. We always had the luxury of preparing for the long term, committing to long timelines, and investing now to reap the benefits later, all because we could rely on revenues growing seemingly on their own.

The first half of 2023 was a jarring return to reality, and I was surprised by how many things had to change about how I operated and made decisions. Here were a few of the most substantive shifts I’ve made as a result:

Preferring contractors over full-time employeesI had always strongly preferred to hire people full-time, as W2 (or equivalent) employees with good salaries and substantial benefits. I saw it as a moral duty, recalling the precarity of my 20s.

But this year, I learned that the ability to be generous is a privilege. It’s tremendously gratifying, but can only be justified if the underlying business is healthy and profitable. As a result of giving away more than the business could support, I had to lay off three people.

There are also several major risks with employees that only came to light in a downturn: salaries and benefits are easy to raise, but basically impossible to reduce. Employees can’t be dialed up or down based on the company’s needs – they are always at 100% capacity. And in many countries, laying someone off triggers onerous requirements for documentation, mandated retraining, and severance payments that I wasn’t fully aware of upfront.

Going forward, I’m going to prefer keeping people as part-time contractors, only increasing to full-time if the needs of the business truly justify it, and reserving employee status to a small, core team of people that are essential to the business’s survival.

Diversifying the businessFor many years, I’d resisted diversifying the business into different products and services, because I wanted to focus 100% of our attention and effort on making the cohort-based course as good as it could possibly be.

That strategy paid off handsomely when the pandemic started because we had the most well-known, mature live program just as people wanted to learn new skills in a social setting. We were completely dedicated to it, resulting in big leaps of improvement from one cohort to the next. This was in contrast to many creator-led businesses who I believe diversify too early and split their attention across too many things to make any of them truly excellent.

But the tables turned as the post-pandemic slump caught us off guard. Suddenly people distinctly did NOT want to take live programs – they wanted to see their friends, travel, and go out. The tried-and-true launch process we’d perfected over 14 cohorts suddenly kicked into reverse gear, and since the whole company depended on it, we had no secondary revenue stream to fall back on.

From this point on, I’m going to proactively diversify our business so that we’re insulated from dramatic swings in the market. We now have a strong brand and highly capable team that I believe will be able to maintain and improve a full portfolio of offerings, while leaving me free to create new ones. We’ve now grown up and matured into a “real” business that can do more than one thing at once!

Preparing for a new chapterI’ve always thought about my life in terms of stages or “seasons.” A chapter often opens with me moving to a new place, starting a new job or relationship, or embarking on a new endeavor.

It’s clear to me now that the business also moves through seasons, and it is approaching the end of one. The BASB book that defined the last four years has now been out for more than a year and is thriving on its own momentum.

The follow-up “implementation guide” The PARA Method came out on August 15th, 2023. The team is fully integrated and confident in its abilities, I’m no longer involved in teaching our courses, and have stepped back from almost all day-to-day operational duties as our new COO Monica takes over.

I recently wrote about my most important realizations and insights as this chapter closes, which emerged from a mastermind retreat I hosted with other creators in June 2023. It was a wonderful opportunity to step out of my normal reality and take stock of everything that’s happened over the last year, especially as seen through the eyes of others.

I don’t know what will happen next, but I have a strong intuition that whatever it is, it will be the most exciting season yet, building on everything we’ve accomplished before in ways I’m confident I can’t even imagine.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post Surviving the Post-Pandemic Slump: How We Recovered From an 87% Drop in Profit appeared first on Forte Labs.

August 20, 2023

Organize Your Bookmarks with the PARA Method for Lightning Fast Web Browsing

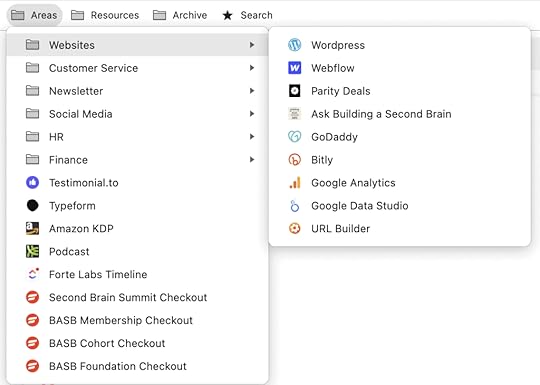

I don’t know about you but I spend a BIG chunk of my workday in my browser (I use Chrome).

It’s where I draft landing pages in Google Docs, send emails in ConvertKit, publish blog posts in WordPress and check sales numbers in SamCart.

Everything I create becomes ultimately a link, a URL that needs safekeeping somewhere.

That means having the right links readily accessible is crucial for moving smoothly through my day.

The problem: My bookmark bar looked like a junk drawer! It was an indistinguishable jumble of links, without hope of finding the one I truly needed in the moment.

Sounds familiar?

The solution seemed stupidly simple once Rodney Daut, one of our BASB Facilitators, pointed it out.

Organize your bookmarks just like you organize any other information: according to the PARA Method.

What’s PARA? A Brief IntroductionPARA stands for Projects, Areas, Resources, and Archives. It’s a simple system for organizing virtually any information in your life.

Projects are what you’re currently working on that has a concrete outcome and timeframe. For example, some of my current projects are The PARA Method book launch, a trip to ConvertKits Craft + Commerce conference, and the Ultraspeaking cohort I’m part of.Areas are your responsibilities that don’t have an end date. For example, my areas include my apartment, my Muay Thai practice, and my Course Creator Lab website.Resources are your interests and curiosities. For example, I continuously gather resources around copywriting, minimalism, and remote living.Archives are all items from the previous three categories that are no longer relevant. For example, my Archive is full of trips I’ve taken in the past.The key principle is organizing by actionability. PARA helps you keep the information you need the most right now front and center (while keeping everything else accessible but out of sight).

Want to learn more about PARA? Check out this intro.

Implementing PARA in Your Browser

Implementing PARA in Your BrowserI’ve had my notetaking app Evernote and my Google Drive organized according to PARA since 2020.

But it never occurred to me that I can apply the same structure to my browser. (Duh!)

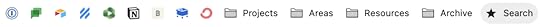

Here’s what my bookmarks bar looks like after I re-organized it:

On the left side are all sites that I’m visiting multiple times per day. On the right side are my PARA folders plus the bookmark search. Finally, I have the links I need readily accessible.

Let’s look at how to implement this for yourself in a few simple steps:

Step #1: Create your Archive folder and move all your bookmarks in thereIf you don’t currently have a bookmarks bar in Chrome, go to “View,” then click “Always Show Bookmarks Bar.”

Create a folder by right-clicking on the bookmarks bar and selecting “Add Folder…” Then drag and drop all your current bookmarks into your new Archive folder.

Now, you can start from a clean slate.

Step #2: Create your Projects folder and add links to your active projectsYour Projects folder should contain the links that you need the most at this moment because they’re associated with concrete outcomes you want to achieve.

Here’s an example of my Projects folder with a sub-folder for each active project.

Each of these folders contains at least one link. There are no empty folders as these would just clutter the view.

Once a project is complete, I’ll move the associated folder simply to Archive.

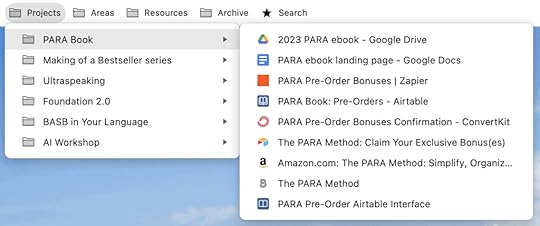

Step #3: Create your Areas folderYour Areas are everything that needs continuous attention from you, without a specific end date.

For me, that includes maintaining our websites, feeding our social media channels, and creating our weekly newsletter, among others.

Here’s what my Areas folder and sub-folders look like:

Step #5: Create your Resource folder

Step #5: Create your Resource folderYour Resource folders contains everything else that’s useful and handy to keep around. This is a great place to save links to templates, tools, and learning resources.

This is what my Resource folder and sub-folders look like:

Optional: Add shortcuts to your most visited websites

Optional: Add shortcuts to your most visited websitesI already know that I’ll visit a few websites multiple times per day, so I want to get to them with one click.

Here’s how you can add these icons to your bookmarks bar.

Visit the website you want to bookmark.Right click on the bookmarks bar and select “Add Page…”Delete the “Name” and hit save.Now, only the favicon shows up in your bookmarks bar.

Optional: Add a bookmark searchIf you reach a point where you have A LOT of bookmarks stored, having a shortcut to search comes in handy.

Right click your bookmarks bar and select “Bookmark Manager.” Now, add a bookmark to the Bookmark Manager as described above.

You may want to rename it “Search”, too. It’s easy to forget that it’s your method of searching your bookmarks without that label.

(Not using the Chrome browser? The same principles can be applied to any browser you might use.)

After testing PARA in my browser for a month, I can say it has helped me create a more productive, friction-less work environment. And I hope it can do the same for you, too.

This blog post was written by Julia Saxena , Director of Marketing at Forte Labs, and inspired by BASB Facilitator Rodney Daut .

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post Organize Your Bookmarks with the PARA Method for Lightning Fast Web Browsing appeared first on Forte Labs.

August 5, 2023

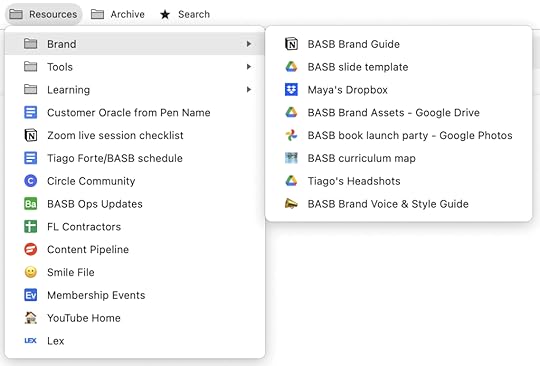

How to Create an AI Style Guide: Write With ChatGPT in Your Own Voice

I recently came across an interesting guide on how to train ChatGPT to write in your own voice and style. It is part of the Substack publication Write With AI, by Nicolas Cole and Dickie Bush.

I decided to give it a try because if I succeeded, this would solve one of the biggest problems I’ve noticed with ChatGPT: the writing it generates is almost always boring, vague, and lifeless.

Here are the three steps the article suggested I follow:

Step 1: Grab a “signature” piece of writingStep 2: Prompt ChatGPT to analyze the writingStep 3: Give ChatGPT the sample writingHere’s how I did it, step by step.

Step 1: Grab a “signature” piece of writingI started by using Google Analytics to find the most popular pieces of writing I’ve published:

The PARA Method: The Simple System for Organizing Your Digital Life in Seconds (2,000 words)Building a Second Brain: The Definitive Introductory Guide (4,500 words)Progressive Summarization: A Practical Technique for Designing Discoverable Notes (2,900 words)How To Take Smart Notes: 10 Principles to Revolutionize Your Note-Taking and Writing (7,000 words)12 Steps to Build a Second Brain (700 words)One-Touch to Inbox Zero: How I Spend 17 Minutes Per Day on Email (3,800 words)The One-Touch Guide to Doing a Weekly Review: How I Go From Chaos to Clarity in 30 Minutes (3,900 words)The 4 Notetaking Styles: How to Choose a Digital Notes App as Your Second Brain (1,600 words)How to Summarize Books Using ChatGPT: 7 Experiments in AI Distillation (2,700 words)What I Learned From The Bullet Journal Method (2,000 words)My ultimate goal is to be able to replicate the success of these pieces, “mass producing” articles at the same standard of quality and in my same voice without me having to personally compose every single word.

A quick Google search reveals that the current “context window size” (i.e. how many words ChatGPT can process and understand at once) is now about 4,000 words. I used the Google Chrome plugin Word Counter to determine how many words each of the above pieces was and added that number in parentheses after each one.

Good news! It looks like nearly all of them can fit in their entirety within a single ChatGPT prompt.

Step 2: Prompt ChatGPT to analyze the writingHere’s the prompt I used from the Write With AI guide:

You have expertise in linguistics, natural language processing, and prompt engineering.

Your task is to convert the provided text into an elaborate style guide.

This guide will serve as a blueprint for creating fresh content on a distinct topic while maintaining the original style demonstrated in the text.

Pay special attention to aspects like:

The voice and tone: How formal or casual is the language? Is it authoritative, friendly, neutral, or something else? Mood: What emotional atmosphere is created? Does the text seem cheerful, melancholic, mysterious, etc.? Sentence structure: Are the sentences simple, compound, complex, or a mixture? How long are they typically? Transition style: How does the writer navigate from one idea to another? What types of transition words or phrases are used? Rhythm and pacing: Is the writing fast-paced with lots of short sentences, or is it slow and deliberate with longer sentences? Signature styles: Are there any recurring phrases or unique punctuation usage that stands out? Any patterns or repetitions?I am particularly interested in the stylistic nuances that set this author’s writing apart.

Identify those elements that could serve as indicators of this author’s distinctive writing style.

Let me know when you are ready for the text.

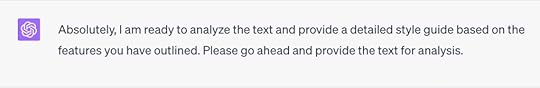

Within a few seconds, ChatGPT responded:

It’s go time!

Step 3: Give ChatGPT the sample writingNext, I copied and pasted the entire text of my first piece, The PARA Method blog post, into the chat window. Here’s what it looked like:

And here’s how ChatGPT replied:

After reading the text thoroughly, I will outline the key stylistic elements that can be used to create a similar style of content in the future.

Voice and Tone : The voice is authoritative, informed, and experienced. The tone maintains a balanced blend of formality and conversational approachability, making it authoritative yet relatable. The writer frequently uses inclusive language (“you,” “we,” “us”) to foster a sense of connection with the reader. Mood : The mood is largely optimistic, motivational, and encouraging, creating a sense of potential and progress for the reader. Sentence Structure : The sentences are a mixture of simple, compound, and complex structures. The writer employs a variety of sentence lengths to maintain reader interest and pace. Short sentences are often used for emphasis or to make important points. Transition Style : The writer transitions smoothly between ideas, often using connective phrases like “in other words,” “but most of all,” “instead of,” and “after more than.” This helps the reader to follow the flow of ideas and see their interconnections. Rhythm and Pacing : The writing maintains a deliberate pace, giving the reader time to absorb and understand each point. Shorter, punchier sentences are used to maintain rhythm and punctuate key points. Signature Styles :The writer frequently employs the technique of introducing an idea, followed by further explanation and then real-world examples. This lends credibility and aids understanding.Questions are regularly posed to engage the reader and encourage reflection.The writer uses personal anecdotes and experiences to provide real-world context and authority.The use of lists and bullet points is common to highlight multiple examples or steps.The writer often directly addresses potential doubts or concerns the reader might have, and then offers solutions.Using these stylistic elements as guidelines, you can create content that maintains the distinctive style of this text. The ability to balance an authoritative tone with approachability, provide clear examples, and directly address the reader’s potential concerns are key elements in recreating the style demonstrated in the text.

Wow! There’s a lot to unpack here, but I could tell right away that these were useful guidelines for creating writing in my style.

I decided to try it again with a different piece, to see if ChatGPT’s evaluation of my style varies much from one piece to another. I typed:

“Next, I will ask you to perform the same evaluation on a different piece by the same author. Please let me know when you’re ready,” and then pasted in the full text of The 4 Notetaking Styles.

Here’s what ChatGPT replied with:

This piece, like the previous one, also follows a discursive and pedagogical style. Here are some key stylistic features:

Direct Address to the Reader : The author communicates directly to the reader, guiding them through a personal journey of understanding. It creates a friendly, conversational tone that draws the reader in and keeps them engaged. Use of Analogies and Metaphors : The author uses archetypal roles (e.g., the Architect, the Gardener, the Librarian, and the Student) as metaphors to describe different types of note-takers, making abstract concepts more concrete and understandable. These are enriched with specific examples and descriptions, giving each metaphor a solid characterization. Balanced Exposition : The author offers a balanced discussion of each note-taking style, detailing its strengths, potential pitfalls, and suited note-taking applications. This makes the content feel fair, objective, and comprehensive. Empowerment : The article emphasizes the individual’s ability to understand their unique style and adapt accordingly. It promotes self-efficacy, encouraging readers to determine their unique way of working and choose the tools that best serve their needs. Use of Rhetorical Questions : The author uses rhetorical questions (e.g., “How do you pick the right app?”) to engage readers, provoke thought, and prepare them for upcoming answers or discussions. Interdisciplinary Approach : The piece draws on concepts from various fields, such as architecture, gardening, library science, and education, showcasing the author’s broad knowledge base and the interdisciplinary nature of their approach. Signposting : The author uses clear headings to structure the piece, allowing the reader to follow the progression of ideas easily. Invitation to Interact : The author invites the reader to engage with additional resources (a YouTube series), extending the conversation beyond the written piece. This further strengthens the pedagogical nature of the work.The author’s style, again, is clear, engaging, and approachable, with a strong focus on empowering readers to understand their personal styles and needs. This work demonstrates a deep understanding of the subject matter and a strong commitment to helping readers navigate their individual paths through the terrain of knowledge management.

Fascinating!

Despite the topic being quite similar, ChatGPT identified a number of new stylistic elements. For example, it picked up on my “Use of Analogies and Metaphors,” which wasn’t mentioned anywhere in the first analysis despite being something I tend to rely heavily on. It also named “Signposting” as a wonderfully specific way of structuring articles, which wasn’t mentioned in the first analysis either.

In other cases, ChatGPT identified the same element but described it in a more precise way that will be easier for me to apply to future output. For example:

“Direct Address to the Reader” (from the second analysis) is much more specific than “The writer frequently uses inclusive language (‘you,’ ‘we,’ ‘us’) to foster a sense of connection with the reader” (from the first analysis)“Use of Rhetorical Questions” is much more accurate and succinct than “Questions are regularly posed to engage the reader and encourage reflection”“Interdisciplinary Approach” is much more useful than “provides real-world context and authority” because it explains why it has authority – by drawing on multiple disciplinesThis significantly better result made me wonder if ChatGPT benefited from seeing multiple examples of writing by the same author.

I decided to do a third round and typed “Thank you, that second analysis was better because it used more specific and concrete terminology and examples. I’d like to give you a third piece by the same author to analyze in the same way. Let me know when you’re ready.”

After pasting in the full text of One-Touch to Inbox Zero, here is the result (I’ve underlined the parts we haven’t seen before):

Based on the provided text, here’s a breakdown of the key stylistic elements and the subsequent style guide:

Voice and Tone : The text’s voice is authoritative and instructional. It provides clear directions on how to manage emails efficiently and doesn’t leave much room for interpretation, showing the writer’s expertise on the subject matter. The tone, however, is conversational and engaging, with an emphasis on addressing the reader directly (“you”) to create a sense of intimacy and personal relevance.Style Guide: Maintain an authoritative yet conversational tone. Use the second person pronoun ‘you’ frequently to keep the text engaging and personalized.

Mood : The mood of the text is empowering and encouraging. It aims to provide solutions, motivate the reader to take control of their email management, and thus their time and productivity.Style Guide: Ensure the mood remains empowering and solution-focused. The aim is to instill a sense of confidence and control in the reader.

Sentence Structure : The sentences are a mix of simple, compound, and complex structures. The author uses longer sentences to explain concepts or processes and shorter sentences to emphasize key points or actions.Style Guide: Use a mix of sentence structures. Use longer sentences for explanations and shorter ones for emphasis and action points.

Transition Style : The author uses a mixture of numbers, line breaks, and transition words (such as ‘then’, ‘but’, ‘also’) to navigate from one idea to another. This helps in breaking down the information into digestible chunks.Style Guide: Use a combination of numeric points, transition words, and paragraphs to guide the reader from one idea to the next. Break down complex ideas into simpler, digestible parts.

Rhythm and Pacing: The pacing of the text is steady, and the rhythm is dictated by the transition between different ideas and steps. The author carefully balances detail with progression to maintain reader interest and comprehension.Style Guide: Maintain a steady pace. Provide enough detail to fully inform the reader without overwhelming or slowing down the flow of information.

Signature Styles : The author has a habit of using all-caps for emphasis (e.g., “WITHOUT ACTUALLY DOING IT,” “YOU”). Quotations are used strategically to reinforce points. Repetition is used for emphasis and to ingrain crucial points in the reader’s mind (e.g., the various references to archiving each email).Style Guide: Use capital letters for emphasis sparingly. Incorporate relevant quotes to support points. Use repetition strategically to reinforce important concepts.

Distinctive Element : One distinctive aspect of the author’s style is the use of numbered points to present a clear step-by-step guide. Another is the use of direct commands to guide the reader’s actions (e.g., “Turn on Auto-advance,” “Open Gmail”).Style Guide: Use numbered points for step-by-step instructions. Use direct commands to guide the reader’s actions.

This style guide should help maintain the original style while creating new content on different topics. The key is to balance the authoritative tone with a conversational approach, using clear instructions, strategic repetition, and a mixture of sentence structures.

And finally, a fourth round, on the piece 12 Steps to Build a Second Brain (novel parts underlined):

Having analyzed both text samples, here’s the comprehensive style guide that reflects the author’s writing:

Voice and Tone : The voice in these texts is authoritative, yet friendly and approachable. The author is clearly knowledgeable and experienced in the subject matter and provides guidance with confidence. However, the language is quite informal and conversational, making the content accessible and engaging. Mood : The mood of the texts is upbeat, positive, and encouraging. The author empowers the reader to take steps and implement the suggestions offered, promoting a can-do attitude. Sentence Structure : The sentence structures are quite varied. There is a good mix of simple, compound, and complex sentences. The author seems to prefer shorter sentences for making specific points or giving instructions, while longer sentences are used to explain concepts or provide context. Transition Style : Transitions are clear and organized, typically with the use of numbered or bulleted lists to guide the reader through sequential steps or related points. The use of informal, conversational transitions (e.g., “Believe me,” “But I know”) are also common, making the text more relatable. Rhythm and Pacing : The rhythm is generally consistent, using a mix of sentence lengths to maintain reader engagement. Pacing varies according to the content – instructions or steps are delivered in a brisk, direct style, while explanations or conceptual content take a more measured pace. Signature Styles : The author regularly employs the technique of Direct Address , speaking directly to the reader using “you,” which helps in creating an engaging, interactive feel to the writing.The author frequently uses Imperative Sentences for instructions or recommendations, which conveys authority.The texts feature several External References , directing the reader to other resources (e.g., workshops, blog posts, videos) to provide additional context or detail.There is a noticeable trend of the author using Phrases of Assurance (e.g., “Believe me,” “I invite you,” “I recommend”), which help build trust and rapport with the reader.The author often uses Colloquial Language and Informal Phrasing (e.g., “get your Second Brain started,” “saving any article or other piece of online content you’re interested in for later consumption”) to keep the tone light and relatable.In sum, when crafting content in this author’s style, strive for a friendly yet authoritative tone, use a mix of sentence structures, clear and organized transitions, and maintain an upbeat mood. Remember to address the reader directly, give clear instructions, make external references, use phrases of assurance, and use informal language when appropriate.

I’m surprised that we’re still seeing many new patterns that ChatGPT has identified in my writing. Presumably I could keep feeding it new pieces, but I think this is enough for now.

Next, I combined all four analyses produced so far, and asked it to synthesize them into a single, unified style guide. I adapted the initial prompt, instructing ChatGPT to analyze and integrate its previous four analyses into a style guide:

You have an expertise in linguistics, natural language processing, non-fiction writing, and prompt engineering.

Your task is to convert the following analyses of an author’s writing into an elaborate, detailed style guide.

This guide will serve as a blueprint for creating fresh content on a distinct topic while maintaining the original style demonstrated in the analyzed texts.

Let me know when you are ready for the analyses.

Here’s what ChatGPT came up with:

Author’s Writing Style Guide1. Voice and Tone

The voice of the author should come across as knowledgeable and authoritative yet approachable. In other words, the writing should carry a sense of expertise without sounding overly academic or detached. The language should strike a balance between formality and conversationality. The author should be seen as a guide, providing valuable insights while fostering a strong sense of connection with the reader.

Guideline: Write in a manner that comes across as informed and experienced without being intimidating. Use an approachable tone that is conversational yet professional, fostering a sense of connection with the reader.

2. MoodThe mood of the writing should be largely optimistic, motivational, and encouraging. The goal is to foster a sense of potential and progress, urging the reader to aspire and strive for better.

Guideline: Keep the mood uplifting and positive. The writing should inspire the reader and encourage them to take action.

3. Sentence StructureThe author employs a mix of simple, compound, and complex sentences. A variety of sentence lengths should be used to maintain reader interest and control the pacing of the narrative. Short sentences should be used for emphasis or to highlight important points.

Guideline: Craft sentences of varying structures and lengths. Utilize short sentences for emphasis and longer sentences for detailed explanations or descriptions.

4. Transition StyleTransitions should be smooth and seamless, using connective phrases and words to link ideas. This helps guide the reader through the text, allowing them to follow the narrative and see the interconnections between different points.

Guideline: Use transition words and phrases such as “in other words,” “but most of all,” “instead of,” and “after more than” to ensure smooth transitions between ideas.

5. Rhythm and PacingThe writing should maintain a deliberate pace, allowing readers time to absorb each point. Shorter, punchier sentences can be used to maintain rhythm and accentuate key points.

Guideline: Maintain a steady rhythm throughout the text by controlling the pace with the use of sentence length.

6. Signature StylesThe author uses several distinct techniques and patterns in their writing. These include the use of:

Introduction of an idea followed by further explanation and real-world examplesRegular use of questions to engage the reader and encourage reflectionPersonal anecdotes and experiences to provide context and authorityLists and bullet points to highlight multiple examples or stepsDirectly addressing potential doubts or concerns the reader might have, and offering solutionsGuideline: Implement these signature styles in your writing. Introduce ideas and follow them up with explanations and examples. Pose questions, share personal experiences, use lists and bullet points, and directly address the reader’s concerns.

7. Use of Analogies and MetaphorsThe author is known for the use of archetypal roles as metaphors to make abstract concepts more concrete and relatable. They draw from various fields to provide enriching and characterizing examples.

Guideline: Utilize appropriate analogies and metaphors in your writing, drawing from various disciplines to make your points more understandable and relatable.

8. EmpowermentA significant theme across the author’s work is the empowerment of the reader. The author encourages the reader to understand their unique style and adapt accordingly.

Guideline: Write in a way that promotes self-efficacy and encourages readers to recognize and harness their unique potential.

9. Use of Rhetorical QuestionsThe author frequently uses rhetorical questions to engage the reader, provoke thought, and pave the way for discussions or answers.

Guideline: Incorporate rhetorical questions in your writing to stimulate the reader’s thinking and to introduce new ideas or discussions.

10. Interdisciplinary ApproachThe author draws from various fields in their writing, showing their broad knowledge base and the interdisciplinarity of their approach.

Guideline: Use an interdisciplinary approach in your writing, linking concepts from various fields to provide a rich and diverse perspective.

11. Direct Commands and Use of NumbersThe author is known for using direct commands and numbering to guide the reader’s actions and structure information.

Guideline: Use direct commands to guide the reader’s actions and numbering to provide a clear structure to your writing.

Following this style guide will help you create content that reflects the author’s distinctive style, while being adaptable to various topics. It offers a balance of authority and approachability, promotes reader engagement, and encourages personal growth, which are key elements in replicating the style demonstrated in the analyzed texts.

This looks great! It’s always a bit dangerous to perform an “analysis of an analysis” when it comes to writing, as that can quickly turn into talking “about” things rather than just saying them directly. For example, the instruction “Write in a way that promotes self-efficacy” strikes me as unhelpful, as it’s not actually saying how to do that.

Still, this is without a doubt the most detailed and thorough analysis of my writing style I’ve ever seen. If it can be used to produce even a rough draft in my voice, that will represent a huge leap forward in our editorial process.

If you’re looking for advice on how to leverage AI tools like ChatGPT for writing, I can highly recommend subscribing to Write With AI. They have both free and paid options, and it’s been one of my favorite educational resources on this topic.

In a future piece, I’ll take you through the steps I followed to utilize this style guide to generate a new piece of writing.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post How to Create an AI Style Guide: Write With ChatGPT in Your Own Voice appeared first on Forte Labs.

July 31, 2023

Bring Building a Second Brain to Your Organization

We’re looking for organizations that want to teach their people how to build their own “Second Brain” – a system of knowledge management that empowers them to capitalize on the value of what they know and use it to advance their organization’s goals.

We now offer a complete portfolio of products and services on this theme, including a bestselling book available in multiple languages and formats and our new self-paced course BASB Foundation. Together they provide learners with an accessible, flexible, and impactful training experience at their own pace and on any device.

Over the years we’ve heard countless times from people within companies and organizations who desperately need a Second Brain for the work they do. We’ve heard the stories of rampant Information Overwhelm, crushing volumes of email and other communication, not to mention the constant need to innovate and solve complex new problems in an uncertain economy.

After a decade of working with individuals to develop the BASB methodology, and testing it with a small group of influential organizations (like Toyota, the World Bank, and Genentech), we are opening the doors for the first time to new organizations who want to partner with us.

We are seeking deployments of at least 100 employees to receive BASB training. You will work closely with our expert team to assess your organization’s training needs, set learning goals for participants, and track the impact of this educational experience on your organization.

Here are some of the top benefits we’ve found professionals receive from this kind of training:

1. Enhanced Productivity & Job Satisfaction

Rapid improvements in productivity and effectiveness due to an enhanced ability to move initiatives forward on multiple fronts simultaneouslyRelief from Information Overload and the burden of high volumes of incoming information through the use of digital organization methodsMajor reductions in stress levels, overwhelm, and burnout as people organize their digital environment to promote clarity and peace of mind2. Improved Communication & Collaboration

Improvement in people’s ability to handle communication across multiple channels, and respond effectively in a timely wayBetter participation in meetings due to a reliable method for taking notes on and following through on action itemsSurfacing tacit knowledge hidden within the organization, allowing people to learn from each other and double down on what’s working3. Advanced Learning & Skill Development

Enhanced learning and development abilities due to better notetaking and retrieval skillsHigher fluency with the latest digital platforms, including learning how to rely on external tools to manage and push forward their responsibilitiesRapid skill acquisition from being able to independently pursue and complete skills-focused training4. Streamlined Project Management & Decision Making

More effective project management, especially in projects that require tracking large volumes of informationGreater capacity to document, reference, and resurface organizational knowledge to improve products, services, and internal processesEnhanced decision-making as past insights and lessons can be easily revisited via digital notesIf you’re interested, please click the button below to complete a short form. We’ll be in touch.

I'm interested in corporate training!The post Bring Building a Second Brain to Your Organization appeared first on Forte Labs.

The 6 Pillars of Our Book Promotion Strategy

There’s something book publishers don’t tell you when you sign their offer on the dotted line: almost all the responsibility for promoting your book will fall on your shoulders.

A lot of authors complain about this fact as if it represents publishers shirking their duty or being lazy. I see it quite differently: authors are responsible for selling their books because they are by far the best positioned to do so.

No one else has the direct relationship with potential readers, an abundance of behind-the-scenes and “making of” material, the voice and point of view that the book embodies, and of course, the motivation to give it everything they got.

Expecting any publisher to simply forget these facts and valiantly sell your book on your behalf is a denial of reality. No one is going to put in a fraction of the time, effort, and care into promoting your book as you.

Keeping that in mind, our promotion strategy for Building a Second Brain rested on six pillars, each one representing a powerful leverage point in its trajectory:

The proposalThe brand identity design and media kitThe pre-order campaignThe email listThe YouTube channelSharing regular updates on my journeyPillar #1: The ProposalLaunching a book into mainstream awareness is like starting a business from scratch.

You will eventually need to recruit an entire ecosystem of people, companies, communities, funding sources, distribution channels, wholesale and retail outlets, online platforms, promotional partners, and digital and physical supply chains, and then coordinate them all to gracefully deliver an impactful message on a global scale.

Sounds easy right?

Most of the advice out there says to make your proposal as good as it can be, but I don’t think most aspiring authors put nearly enough emphasis on it. Your proposal is everything – a step-by-step business plan that lays out everything you will make happen over a period of years.

It’s impossible to invest too much time and attention on the proposal, not only because it determines whether your book gets sold in the first place, and for how much, but because the decisions you make there will bias every subsequent decision made by everyone connected to the book.

This is why it took me 9 months to finish my proposal (which you can read in its 61-page entirety). It was some of the best time I spent. I hired a highly experienced developmental editor Janet Goldstein to help me with it, and it was a major project within itself. (If you’re looking for an expert opinion on your book idea, I suggest booking one of her Laser Intensives).

Many authors don’t work with a developmental editor, but I think that’s a big mistake. No agent or friend can give you anywhere close to the level of attention and experience you’ll receive from someone who has worked on multiple successful book proposals in the past. I went on to hire the same editor to work with me on the manuscript itself, which gave me a long-term thought partner who provided continuity through this long process.

In the proposal we tried to make as many important decisions as possible, including:

The main problems we were proposing to solveThe main historical analogy we would use to frame our solutionThe dysfunctional approach we would compare our solution with most directlyWhich tangible benefits of building a Second Brain to highlightHow to tell my origin story and why it led me to want to write this bookWhich main audiences we thought would be interested in the bookWhich competing and complementary titles to use as modelsA selection of marketing and promotion opportunities we envisionedThe topics of each chapterFor me, the most important outcome from this entire proposal-writing process was the decision to pivot the BASB message to a much more mainstream, “beginner” audience.

It was necessary and important to appeal to hardcore PKM nerds in the early days, as they were at the forefront of this emerging field and had the motivation to wade through the messy details. But now that the core ideas and method had been established, I didn’t want to remain limited to that niche. I didn’t want to write a book preaching to the same choir: I wanted this idea to spread to wider circles of people who hadn’t previously even heard of the concept of a second brain, and if it wasn’t for this book, might never be exposed to it.

In retrospect, this seems like the obviously right decision, but it wasn’t an easy one. I had to endure a lot of dissatisfaction and outright criticism from the audience I had built up to that point. Many people felt like I’d “dumbed down” the ideas and diluted their power. Some even felt like I’d abandoned or betrayed them.

What kept me going was the thought of the many new kinds of people we’d be able to reach with a broader, more accessible voice, including:

The Creator Economy and content creators in generalFreelancers and entrepreneurs of all kindsGig workers who need a way to take information from one job to anotherMillennials, who are quickly rising into positions of leadership across the economyRemote workers needing better self-management skills (which exploded in numbers during the pandemic)Notion users (Notion raised major funding the same week as my proposal was sold, with a featured article in the New York Times, which I believe positively impacted our prospects)Fans of organizing and decluttering (such as Marie Kondo)People who like to take online courses and need a way to take notes on themPeople with ADHD and other neurodivergent conditions, looking for a way to alleviate their symptomsThe early decision to “go mainstream” gave me the clarity and courage to break away from the insider language of the “PKM clique” that predominates online, and to instead seek language that anyone – older and younger generations, people in non-digital professions, people without formal education, people living in other countries, and the non-tech savvy – could not only understand but put to use in their own lives.

The proposal was extremely well-received, attracting four imprints from three publishers in a two-round auction that ended with a multi-six-figure deal. Once we had that in hand, it was off to the races.

Pillar #2: The Brand Identity Design and Media KitI decided early on to create a full-fledged visual brand identity for my book. I already had a BASB ecosystem with multiple products and services and knew that in the future we’d likely have multiple books, other titles like journals or workbooks, physical products, and eventually, even other media like films, TV shows, board games, and apparel.

To make sure all of these elements fit together as a cohesive brand, I hired an experienced designer to deeply research our content and audience and develop a comprehensive BASB brand identity made up of:

Core brand attributesA beautiful logo that works across platforms and different media typesUsage guidelines for ourselves and external partiesAn official typeface and typography samplesColor palette and how colors should be usedAccessibility improvementsAn entire graphic language we call “circuits”Photography examples and guidelinesA creative gallery envisioning what future touchpoints could look likeThose brand guidelines became part of a broader BASB media kit, which was unbelievably helpful to share with anyone who wanted to talk about or promote the book, providing everything they might possibly need with just a link. The media kit additionally includes:

Important linksKey messagesHigh-quality book photosPress kit materialsMy bio and headshotsDownloadable brand assetsLogos in various shapes, colors, and sizesFair use guide encouraging people to share the BASB message within certain limitsContact info in case they needed something else Pillar #3: The Pre-Order CampaignI didn’t have a large audience back in 2019 when I wrote the proposal – only 6,000 email subscribers and 10,000 Twitter followers. I knew the pre-order campaign was going to be our single best chance of breaking through the media noise, and I needed to do everything possible to create a groundswell of support on release day.

Our publisher set a very early date for opening pre-orders so we had as much time as possible to collect them: November 16, 2021. There would be 210 days, or 7 months, of pre-orders before the official release date on June 14, 2022. I set a goal of reaching 10,000 pre-orders in that time (based on reports from other authors of reaching bestseller lists with similar numbers), which would require about 1,400 pre-orders per month, 357 per week, or 50 per day.