Phyllis Cole-Dai's Blog, page 14

July 7, 2020

A Pandemic Response Poem for Gloria Heffernan

A few months ago, the poet Gloria Heffernan sent a poem of gratitude to Phyllis and her co-editor Ruby R. Wilson for Poetry of Presence. Phyllis and Ruby had never met Gloria, or even communicated.

Gloria’s poem, “In Case You Ever Wonder,” floored Phyllis. By way of reply, she decided to write a “response poem,” building on Gloria’s own words. She shared the two poems, side by side, with her monthly newsletter list in May. (If you’d like, subscribe to her newsletter here.) She has since tweaked her poem and shared it through the Gatherings project, a powerful “art-and-poetry based experiment in giving and receiving” that has emerged from the pandemic.

The two poems by Gloria and Phyllis are presented below. Phyllis remains grateful to Gloria for her lovely words as well as her permission to share.

Gloria teaches at Le Moyne College in New York and the Syracuse YMCA’s Downtown Writers Center. Check out her poetry collection, What the Gratitude List Said to the Bucket List, as well as her two chapbooks: Hail to the Symptom and Some of Our Parts.

Gloria Heffernan

In Case You Ever Wonder

For Phyllis Cole-Dai and Ruby R. Wilson, editors of Poetry of Presence

It started as a letter,

A simple thank you note for a book I love.

It started as a few thoughts

I would put down on paper someday

when I had the time.

And now I have the time,

like a castaway on a desert island

where I can finally say, yes,

this is the book I would want to have with me

when I washed up on that desolate shore.

So if you ever wonder,

I want to tell you both that you

are essential workers.

I want you to know that

in these dark days when everything has

Changed, changed utterly,

one thing that remains is the peace

I find when I open your book to a random page

and find exactly the words I need to hear.

I want you to know that when I walk

the aisles of the supermarket

and see the masked employees stocking

shelves,

I think of the nourishment I derive from

conversations with Pablo Neruda and

Mary Oliver.

When I think of bus drivers

ferrying nurses and janitors to work,

I think of the roads I have travelled

with Wendell Berry and Alice Walker at the

wheel.

When I hear the pots and pans clanging from

windows

and the crowds cheering at the change of shift,

I think of you both as health care workers

toiling in the soul’s emergency room,

where the healing words you have assembled

give us the courage to take off our masks

and pray for our ailing world.

Phyllis Cole-Dai

If You Ever Wonder

A response poem for Gloria Heffernan

I want you to know

in these dark days

when all the world

is utterly changed,

one thing that remains

is how we feel

when anyone opens

the book of Us

to a random page

and finds a truth

they had forgotten.

Nurses and doctors,

meat packers and crop pickers,

journalists and janitors,

clerics and counselors,

bus drivers and truckers,

mail carriers and shelf stockers,

first responders and trash collectors,

scientists and governors and cooks,

every essential worker

eats and drinks

from the book of Us.

Pots and pans clang

from balconies and windows

flung wide from street to sky.

We are the cheering crowd, the book of Us

assembled without masks and bound

together between soft covers

by a strong, supple spine.

Every page is sacred text.

Nobody is not essential.

We are the prayer for our ailing world

and this is the beginning of our shift.

July 4, 2020

“Circling the Pond”

I grew up on a family farm near Mt. Blanchard, a sleepy village in northwest Ohio. Its “lofty” elevation over the Blanchard River supposedly inspired its name. But take it from me: visiting Mt. Blanchard won’t make your ears pop or your nose bleed. Its altitude is only 846 feet.

I was one of those lucky kids who never wished I lived somewhere else. On the farm, when we didn’t have chores to do, my brothers and I had lots of room to roam, and our imaginations too. The swings on the enormous red swing set that my dad built from scratch were our “horses” when we played at being cowboys; its trapeze was the “rope” to which we clung, upside down, over a snake pit or an alligator swamp. The attic above my dad’s shop had wooden stairs that raised and lowered on a rope—perfect for a secret hideout from “the bad guys.” In the barn we had tons of straw bales through which to tunnel. Behind it we had plenty of dirt to dig through to China, though we never got much deeper than six feet before dropping our shovels.

The best place of all to play was a woods and a half-acre pond, located south of the farm buildings. Every July 4th a passel of relatives would gather there for a day-long picnic. We kids would romp and fish and swim. I remember hurtling my bike down the grassy hill, pedaling hard, straight into the pond. When my bike spilled me off and sank, I dove around its submerged form, pretending it was a long-lost shipwreck to be explored, or a flood-swept car whose occupants needed rescue.

When sundown came, nobody shot off fireworks, perhaps because one of my cousins suffered from sound sensitivity. But we kids would shower the dewy grass with our multi-colored sparklers. With our fire-wands we cast magic spells and drew silly designs in the air—until the racing began.

Our races were solo; the competition, ourselves. One child at a time, we stuck the fat tip of a sparkler in the flame of a grownup’s match. Once it flared, proving it wasn’t a dud, we took off on a sprint around the pond, holding our sparkler as high as an Olympic torch, desperate to circle back to the starting line before it fizzled. Not even the fastest among us made it more than halfway around. Year after year I would try, and though I always pushed past my previous best mark, the pond always got the better of me. My sparkler would peter out well short of the goal. Like my brothers and cousins I’d trudge back to the crowd of relatives, my dead steel wire trailing smoke.

How easily we all could have won the race if we had worked together instead of running alone! Despite our lively imaginations, it never occurred to us to station ourselves at intervals around the pond, each with an unlit sparkler. The lead-off runner could have dashed through the darkness, a bouncing ball of sparks, and then ignited the next runner’s sparkler at the exchange point. As the relay proceeded, child to child, success would have been assured. For a greater challenge, we could have run against the clock, as in a track meet. Better yet, by equipping ourselves with multiple sparklers, we could have seen just how many times our “team” could circle the pond without losing our fire.

This July 4th weekend, as I survey the sad pandemic landscape around our country, I can’t help but wish that all of us would work together instead of running alone. A little more imagination might help us recognize that other lives matter just as much as our own. But as a people, priding ourselves as we do on independence, we’re not very practiced at interdependence, are we? So we insist on going solo, despite the odds against us and the tragic facts staring us in the face.

Can you see me? I’m over here, waving from the far side of the pond. I’ve got my mask. I’ve got my supply of sparklers. Are you ready to run your leg of the race? No matter how long this relay lasts, let’s not lose our fire.

(Photo by Brent Gorwin on Unsplash)

July 1, 2020

“I Want to Play”

I work hard. Sometimes too hard. I even work hard at play. Perhaps you suffer the same affliction. Call it “passion” or “devotion” or “loving what you do,” but it is possible to have too much of a good thing.

Recently I gave myself a leisurely gift—a series of online poetry-writing classes with Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer. This might sound to you like just more work in disguise, but trust me, every minute has been pure pleasure. Not one page of assigned homework between sessions. I just have to show up on Zoom and soak it in.

Rosemerry is one of the finest poets and kindest people I know. Ruby Wilson and I featured several of her poems in Poetry of Presence, our popular anthology. As a teacher, Rosemerry coaches you up without intimidating you. Whether you’re a beginning poet or an old hand, she creates a safe space for you to practice—classroom, sanctuary and playground, all rolled into one.

In our latest gathering Rosemerry discussed several poems with the class, including “I Want to Speak with the Blood that Lies Down,” an ecstatic poem by the late Jim Tipton. Here’s just a taste of it:

... I want to speak with thethirsty rain, the lonely garbage, the tire that remembers

when it was a tree in Brazil; I want to speak with

the fragrance of sage that rises up, late into the night,

after a soft rain; I want to speak with cinnamon

and chocolate, and with windows that do not open,

and with the bag of hair in the shop of the old barber….

Do you hear how Jim drives his poem forward by constantly repeating “I want to speak with…”? The poem uses those exact words almost 20 times.

Rosemerry invited us to come up with a similar phrase: “I want to sit with,” or “I want to go to,” or “I want to dream of,” and so on. The words that rose up in my mind and demanded to be used were “I want to play like….” (Big surprise, eh?)

We had twenty minutes to write a poem that repeated and completed our chosen phrase with images. As always, before we started to compose, Rosemerry urged us to lower our expectations and just have fun. This is the poem that tumbled out of me, tweaked a bit the next day:

I Want to PlayI want to play like the bird

that plunges from sky into lake

and surfaces with beak dripping

with fish. I want to play

like ebony and ivory beneath the knobby

fingers of an old pianist,

home at last after a life in exile.

I want to play like my toddler son

once did, making friends of monsters,

tunnels of doors, secret rooms

of walls. I want to play

like the bumblebee bouncing

over my tingling skin

without ever stinging.

I want to play like Brandi Chastain

ripping off her jersey on the soccer field,

baring skin without shame

for joy. I want to play

like eyes that study the chessboard

with such care and skill

and still make the wrong move,

and laugh out loud. I want to play

like the leaves that turn their silver bellies

up to the wind, inviting rain. I want to play

like the magician whose sleight of hand

is so practiced, nobody wants to learn

how it’s done. I want to play like words

cascading down the page

in search of a soft place to land,

freefall of pleasure.

I want to play as if hard work never taught me

to forget how.

I’ve shared this poem with you not because it’s a masterful piece of poetry (it isn’t), but because I enjoyed writing it—and mostly because my son Nathan loved hearing it and thought you might, too.

Now I want to invite you to join me on the playground of poetry. Choose your own repeated phrase, then write a poem of your own. Follow Rosemerry’s advice: Lower your expectations, and just have fun. If you’d like, send me what you come up with. I’d love to read what you write.

Listen to this reflection on the Staying Power Podcast. Remember, you can subscribe to Staying Power on your favorite podcast platform.

June 25, 2020

Art, Poetry & Community Unite in Gatherings Project

Phyllis is happy to announce the public launch of Gatherings, an art and poetry-based project that grew out of the pandemic. The artist Lynda Lowe invited Phyllis to collaborate on this project shortly after COVID-19 struck the U.S. with full force.

Gatherings began with 54 artists creating art on handcrafted birchwood boxes (sized 10″x10″x3″), to which 54 poets then contributed original poems. Ruby R. Wilson and Phyllis managed the poetry side of the project. They recruited work from Naomi Shihab Nye, Jane Hirshfield, Ted Kooser, Ellen Bass, Alberto Ríos, Todd Davis, Danusha Laméris, Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer, and dozens more incredible wordsmiths.

As of this week, all boxes have begun to “travel,” each artist giving the box to someone else. The recipient may keep it for up to three weeks, adding something to the box that speaks to his/her experience of the pandemic—a story, poem, or other writing; a piece of artwork; a meaningful object…. That person then chooses the box’s next recipient, and so on. This sequence of giving and receiving will continue throughout the summer.

Each box and its contents is for sale. All proceeds beyond expenses will be donated to relief funds supporting artists, writers, and other creative professionals who are struggling financially because of the pandemic. Nearly 20 boxes have already been bought. Interested in a possible purchase? Learn more here.

The gallery below presents just four of the 54 box lids, offering a taste of Gatherings. (Click on any image to enlarge it, or view all 54 box lids at once here.) The first image is Untold (watercolor, oil, wax) by project founder Lynda Lowe. It was randomly paired with Naomi Shihab Nye’s “Poem Menu” (read here).

Next, moving clockwise, you’ll see One Tree, Not Alone (oil) by Ivy Jacobsen.Her work is accompanied by two poems penned by Lynn Ungar, entitled “Pandemic” and “Essential” (read here).

The third image is Family (oil, metal leaf) by Tal Walton. Its companion poem is “Reading Faces” by Ruby R. Wilson (read here).

Finally, the whimsical image Domicile (acrylic) by Tyson Grumm is joined by a pair of Phyllis’s poems, “If You Ever Wonder” and “Lessons from a Park Bench” (read here).

May Gatherings bring you a wealth of viewing and reading pleasure. If you’d like, follow the project’s progress on Instagram and/or Facebook.

June 23, 2020

“You Don’t Want to Go There”

The summer of 1976, when I was fourteen, Dad decided that our family of five would take a two-week patriotic pilgrimage. We rarely indulged in big vacations. We were unable to afford either the cost or an extended absence from our farm. Yet there was Dad, pouring over his Triple AAA brochures and the World Book Encyclopedia, mapping our route to Plymouth Plantation, Bunker Hill, the Statue of Liberty, Independence Hall, Valley Forge….

What I remember most about that vacation occurred over a two-day span, late in the trip. On the evening of July 4th, after a furious swing through New England, we arrived in New York City. Dad intended us to enjoy the spectacle of fireworks over the Hudson River. For several days after, we would visit various historic sites.

Caught in a huge traffic jam ahead of the fireworks, Dad cut off on a side street, hoping to escape. His endless zigzagging soon got us lost in Harlem, a place we knew only by (white) reputation. “Lock your doors,” Mom said, eyeing the black pedestrians on the crowded streets.

Exhausted from hours behind the wheel, frayed nerves, and whining kids, Dad finally gave up on the fireworks. He pulled over and studied his city map. Then he started for the Holiday Inn where he’d booked a room, assuring Mom it was in a “good section of town.” (I somehow understood that was code for “white.”) On our way there, we passed a taxi parked at an odd angle from the curb. A man’s body was hanging out the open door of the driver’s side. The murder of that cabbie made the late local news.

The next morning, Dad announced that we wouldn’t stick around to sightsee all the attractions on his New York list. After touring the Statue of Liberty, we’d leave at once for Philadelphia (our version of “white flight”).

Our hotel in the City of Brotherly Love lay in the heart of the Historic District. Despite torrential rains, the District was jampacked with bicentennial tourists. In the hotel lobby, Dad asked the front desk for directions to the nearest McDonald’s, thinking we’d walk.

“Oh, you don’t want to go there,” said an older man, dawdling nearby.

“I don’t?” Dad said, forcing politeness.

“No,” said the man, who looked short as Danny DeVito next to my tall father. From his shoes to his fedora, he was clad in black. Thick, dark glasses obscured his eyes. He put me in mind of a mobster. “Let me take you someplace good,” he said. “Do you have a car?”

Dad was a proud, self-reliant farmer, rather scornful of city slickers. Yet within minutes we were piled in our car with this strange man, wending through the narrow streets at his instruction, our wiper blades not keeping up with the rain. After what seemed forever, we pulled into an alley and parked beside a dumpster under a lonely security light behind a shabby building.

“Come with me,” the stranger said, stepping from our car and popping his black umbrella.

Dad switched off the ignition. The man had already vanished into the building. We exchanged nervous glances.

“We’ve come this far,” Dad said at last to Mom, his fears unspoken. “Might as well go in.”

We were met at the back door by a waiter in fancy clothes. He seated us at a linen-covered table and distributed menus for La Scala’s Copper Penny, one of the most fashionable restaurants in upscale Society Hill.

“We can’t afford this,” Dad murmured to the waiter.

“It’s already taken care of,” the waiter said. He informed us that the stranger was the priest at historic Christ Church. “He also thought you could use this,” he said to Mom, handing her the black umbrella.

The next day our family located Christ Church, returned the umbrella, and put money in the poor box. But we never saw the priest again.

I tell this remarkable story out of gratitude and love for my father, who now dwells in the fog of Alzheimer’s. But I also tell it with sad recognition: Our family would never have had this story of kindness to tell, had the stranger’s skin been the same color as his clothes.

This was originally published in the June 21, 2020 (Father’s Day) edition of Staying Power.

You Don’t Want to Go There

The summer of 1976, when I was fourteen, Dad decided that our family of five would take a two-week patriotic pilgrimage. We rarely indulged in big vacations. We were unable to afford either the cost or an extended absence from our farm. Yet there was Dad, pouring over his Triple AAA brochures and the World Book Encyclopedia, mapping our route to Plymouth Plantation, Bunker Hill, the Statue of Liberty, Independence Hall, Valley Forge….

What I remember most about that vacation occurred over a two-day span, late in the trip. On the evening of July 4th, after a furious swing through New England, we arrived in New York City. Dad intended us to enjoy the spectacle of fireworks over the Hudson River. For several days after, we would visit various historic sites.

Caught in a huge traffic jam ahead of the fireworks, Dad cut off on a side street, hoping to escape. His endless zigzagging soon got us lost in Harlem, a place we knew only by (white) reputation. “Lock your doors,” Mom said, eyeing the black pedestrians on the crowded streets.

Exhausted from hours behind the wheel, frayed nerves, and whining kids, Dad finally gave up on the fireworks. He pulled over and studied his city map. Then he started for the Holiday Inn where he’d booked a room, assuring Mom it was in a “good section of town.” (I somehow understood that was code for “white.”) On our way there, we passed a taxi parked at an odd angle from the curb. A man’s body was hanging out the open door of the driver’s side. The murder of that cabbie made the late local news.

The next morning, Dad announced that we wouldn’t stick around to sightsee all the attractions on his New York list. After touring the Statue of Liberty, we’d leave at once for Philadelphia (our version of “white flight”).

Our hotel in the City of Brotherly Love lay in the heart of the Historic District. Despite torrential rains, the District was jampacked with bicentennial tourists. In the hotel lobby, Dad asked the front desk for directions to the nearest McDonald’s, thinking we’d walk.

“Oh, you don’t want to go there,” said an older man, dawdling nearby.

“I don’t?” Dad said, forcing politeness.

“No,” said the man, who looked short as Danny DeVito next to my tall father. From his shoes to his fedora, he was clad in black. Thick, dark glasses obscured his eyes. He put me in mind of a mobster. “Let me take you someplace good,” he said. “Do you have a car?”

Dad was a proud, self-reliant farmer, rather scornful of city slickers. Yet within minutes we were piled in our car with this strange man, wending through the narrow streets at his instruction, our wiper blades not keeping up with the rain. After what seemed forever, we pulled into an alley and parked beside a dumpster under a lonely security light behind a shabby building.

“Come with me,” the stranger said, stepping from our car and popping his black umbrella.

Dad switched off the ignition. The man had already vanished into the building. We exchanged nervous glances.

“We’ve come this far,” Dad said at last to Mom, his fears unspoken. “Might as well go in.”

We were met at the back door by a waiter in fancy clothes. He seated us at a linen-covered table and distributed menus for La Scala’s Copper Penny, one of the most fashionable restaurants in upscale Society Hill.

“We can’t afford this,” Dad murmured to the waiter.

“It’s already taken care of,” the waiter said. He informed us that the stranger was the priest at historic Christ Church. “He also thought you could use this,” he said to Mom, handing her the black umbrella.

The next day our family located Christ Church, returned the umbrella, and put money in the poor box. But we never saw the priest again.

I tell this remarkable story out of gratitude and love for my father, who now dwells in the fog of Alzheimer’s. But I also tell it with sad recognition: Our family would never have had this story of kindness to tell, had the stranger’s skin been the same color as his clothes.

This was originally published in the June 21, 2020 (Father’s Day) edition of Staying Power.

June 1, 2020

Upon George Floyd’s Death: “We Are the Medicine”

More than 100,000 Americans are now dead of COVID-19. Think about that. One hundred thousand lives, each with a unique way of walking through this world. On May 24, The New York Times marked the grim milestone by listing one percent of those lost on its front page. On the newspaper’s website, we can scroll through a huge graphic that helps us glimpse the persons behind those 1,000 names:

“Carol Sue Rubin, 69, West Bloomfield, MI, loved travel, mahjong and crossword puzzles….”

“Lakisha Willis White, 45, Orlando, FL, was helping to raise some of her dozen grandchildren….”

“Eugene Lamar Limbrick, 41, Colorado Springs, CO, loved automobiles, especially trucks….”

As if 100,000 pandemic dead weren’t bad enough, yet another African-American is dead at the hands of police: George Floyd, in Minneapolis. His alleged crime? Using a counterfeit $20 bill. That’s something I might do myself, without realizing, but if I ever did, I wouldn’t end up dead. My skin’s the “right” color.

George Floyd cried out for his mama and begged for help as a police officer knelt on his neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. For the last three of those minutes, he didn’t speak or move. For the last two minutes, he had no pulse.

The New York Times could fill its front page with the names of African-Americans who have died wrongfully through the years at the hands of police. A huge scrolling graphic on its website might help us glimpse the unique persons behind those names and how easily they were dispatched from this life:

“George Floyd, 46, Minneapolis, MN, called `Big Floyd’ by his friends, a `gentle giant’ with a quiet personality who would `give you the shirt off his back.’ Killed by police outside a grocery store.”

“Breonna Taylor, 26, Louisville, KY, a first responder, killed by police while sleeping in her bed….”

“Dominique Clayton, 32, Oxford, MS, killed by police while sleeping in her bed….”

“Eric Garner, 43, New York City, killed by police after breaking up a fight….”

“Tamir Rice, 12, Cleveland, OH, killed by police while playing in a park….”

“Atatiana Jefferson, 25, Fort Worth, TX, killed by police while babysitting her nephew….”

“Walter Scott, 50, Summerville, SC, killed by police while driving to an auto-parts store….”

“Philando Castile, 32, St. Paul, MN, killed by police while driving home from dinner with his girlfriend….”

“Botham Jean, 26, Dallas, TX, killed by police while eating ice cream in his living room….”

The list would go on and on.

Even during a pandemic, we dare not keep silent when yet another unarmed person of color has been “lynched.” I applaud the peaceful marchers and demonstrators. If I could, I’d be out in the streets with them. As for the rioters, looters and arsonists, let’s be clear: in many cities, community members and public officials agree that the vast majority of them are using the outrage over George Floyd’s death as a cover for their own agendas. Authorities should investigate them and prosecute, where appropriate.

I’m not being political. I’m being clinical. Like all dutiful citizens, I’ve been monitoring the health of our country. The vital signs aren’t good. The coronavirus has only aggravated our nation’s “pre-existing morbidities.” Our risk factors include the rise of white supremacy; deepening scorn for the rule of law, even by those sworn to uphold it; the growing divide between the haves and the have-nots; religious arrogance and hypocrisy; stubborn contempt for science and analytical thinking; pervasive idolatry of “self” and “individual liberty” at the expense of fellow feeling and civic responsibility; suspicion and loathing between political parties, and between liberals and conservatives. We’re fighting a civil war, lung against lung. The guns just haven’t started firing yet.

These symptoms are grave. Survival isn’t guaranteed. The recovery of the nation depends on … well … us. We are the medicine for what ails America. We are the vaccine, tested and true.

You heard me right. We the citizens are both patient and cure. Even from behind our masks, we must help one another breathe—now, before it’s too late.

May 5, 2020

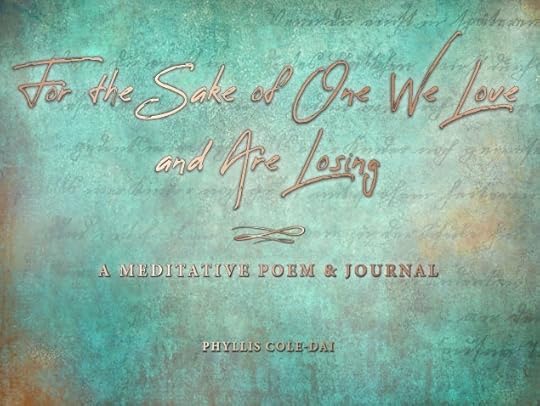

Phyllis Brings “Unforgettable Dream” to Life in Latest Book

“Sometimes inspiration gently tugs at your sleeve,” Phyllis says. “This time it broke through in an unforgettable dream.”

In early February, Phyllis was in California working on a novel-in-progress. “One night I dreamed that a relative had invited `the family’ to her home for a reunion. Multitudes were there. As we spent time together, I realized that my relative was dying. We were there to give her a loving passage from this world into the next.”

“We gathered around her bed,” she continues. “She handed us a book and asked us to read it to her, together. I can still see its turquoise color, and feel the texture of its paper, and sense its great age. It seemed like a sacred book. Its title was For the Sake of One We Love and Are Losing.”

The book turned out to be a meditative poem. “As we read it aloud, together, an incredible wave of love and consolation swept through us all. That feeling was so powerful, it woke me up.”

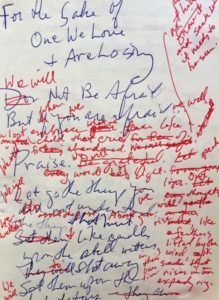

Phyllis says that “something like a voice” told her to get out of bed and write down what she could remember of the poem. She resisted, wanting to go back to sleep, but finally she started scribbling in the dark. “The lines were already escaping my memory. I wrote as fast as I could until I couldn’t remember any more. Then it was like somebody threw the off-switch, and I dropped back to sleep.”

Phyllis says that “something like a voice” told her to get out of bed and write down what she could remember of the poem. She resisted, wanting to go back to sleep, but finally she started scribbling in the dark. “The lines were already escaping my memory. I wrote as fast as I could until I couldn’t remember any more. Then it was like somebody threw the off-switch, and I dropped back to sleep.”

Days later, when Phyllis returned from California to her South Dakota home, she shared the poem with some poet-friends. They urged her to publish it. “I don’t consider myself much of a poet,” she says, “and I don’t take any credit for this poem. It came from the Unknown. It’s my responsibility to honor the dream by getting the poem into the hands of readers who might need it.”

Phyllis teamed up with Tammie Mohr of Choke Cherry Photography & Design to bring the turquoise dream-book to life. Readers can draw comfort from it, share it during (virtual) gatherings of farewell and remembrance, save it as a keepsake, or offer it as a memorial gift. The book includes blank pages for photographs and space for journaling around the poem’s lines.

“I’m struck by how the poem arrived just before the pandemic was known to have hit the U.S.,” Phyllis says. At that time, she was worried about her husband’s quarantined relatives in China. She was also saddened by the general decline of her father in a North Carolina nursing home. “But this poem transcends my personal concerns,” she says. “It speaks to a world in pain. I’ve dedicated it to everyone who grieves.” She plans to sign every copy of the special-edition book.

For the Sake of One We Love and Are Losing (Bell Sound Books, $18.95) will be officially released in mid-May. You may pre-order until May 15. For now, this book will only be available through the author website.

April 6, 2020

Center for Western Studies Awards Phyllis Research Prize

The Center for Western Studies at Augustana University (Sioux Falls, SD) has presented Phyllis with the Richard Cropp Amateur Award for a research paper she delivered at the 51st Annual Dakota Conference. Her subject was Sarah Wakefield and the 1862 U.S.-Dakota War, the basis of her historical novel Beneath the Same Stars. Phyllis is grateful for the Center’s encouragement to reexamine our histories and their ramifications for the present.

March 27, 2020

A Pandemic Poem-Prayer

To observe her 58th birthday yesterday, Phyllis wrote 58 one-line pandemic prayers and shaped them into a poem. See the text below. Perhaps it will give you a boost. You can listen to Phyllis read the poem here or download it here.

ON MY 58TH BIRTHDAY: 58 PANDEMIC PRAYERS

Phyllis Cole-Dai

May we all survive to another birthday.

May we greet the sun each morning and rejoice in being alive.

May we breathe the miracle of fresh air.

May we honor every moment as a chance to begin anew.

May we root our faith in richer soil than worry.

May we let separation knit us close.

May we see faces besides our own in the mirror.

May we recognize all people as kin.

May we cherish them as much as ourselves.

May we stay home to keep them safe.

May we nurture the body that houses our soul.

May we have adequate shelter, food, water, medicine, and rest.

May we share freely from our abundance.

May we resist the temptation to hoard.

May we ask for help without hesitation or shame.

May we draw comfort from the company of animals, flowers, and trees.

May we befriend the sounds of silence.

May we welcome the intimacies of solitude.

May we dive to the depths of our being and bring up blessings we didn’t know we had.

May we be sanctuary for one another.

May we refuse to dwell in the blindness of denial, indifference, or contempt.

May we tame our temper and carry no grudge.

May we empathize even with those we dislike.

May we gift one another with radical attention.

May we listen to one another as if lives depend on it.

May we speak as if our voice will be the last sound ever heard.

May we explore how to touch without touching, how to hold without holding.

May we not be embarrassed by tears and trembling.

May we learn from our children the joy of unstructured time and the solace of routines.

May we reassure our children about the monsters beneath their beds.

May we create new rituals of togetherness.

May we laugh from our bellies.

May we cultivate wonder.

May we help our society to do better than it has done.

May we examine problems from all angles and talk straight as lines.

May we base decisions on collective wisdom rather than contagious fear.

May we invest our trust in those who are experts, not those who pretend.

May we value health over wealth.

May we dedicate our daily work both to those we love and to the common good.

May we sustain those workers whose invisible labor sustains us all.

May we protect those who put themselves at risk to protect us.

May we transform the impossible into the doable.

May we inquire into the welfare of strangers.

May we stand up for those who are scapegoated and targeted by hate.

May we sing porch to porch until all the world is our neighbor.

May we drop expectations of how hard or long this road will be.

May we pace ourselves as we go.

May we each shoulder more of the load so that nobody stumbles beneath it.

May we prepare ourselves for the unknown.

May we follow the light of our brightest prayers.

May we live together into better versions of ourselves.

May we plant the seeds of a new world in what remains of the old one.

May we remember in the dark hours that we’re not alone.

May we let no one die forsaken, in pain, or unt ouched by kindness.

May we grieve the lost, though we cannot gather.

May we do right by their memory.

May we not waste a minute of the precious time they should have had.

May we love one another as we would be loved.

May our children survive us all.

March 26, 2020

© 2020 Phyllis Cole-Dai

Some rights reserved.