Phyllis Cole-Dai's Blog, page 11

December 9, 2020

December 7, 2020

“Love Letter to America”

Attribution: justphotos.ru

Attribution: justphotos.ruDear America,

The piece of paper you’re holding in your hands isn’t a political rant. It isn’t a sermon or a lecture. It’s a love letter, plain and true.

I love you—not you alone, but you most deeply, of all the nations in the world. By accident of birth, I know you better than the rest. I’ve made my life here. And by every measure my life has been fortunate.

Yet, for all that I appreciate about you, and must thank you for, I recognize that, like other countries, you’re not perfect. For one thing, you never admit when you’ve screwed up. In your own eyes, you’re never to blame. You can never bring yourself to say, “I’m sorry,” let alone work to make amends.

This criticism might be hard for you to accept, even from someone who loves you. But you can’t expect me to ignore what’s going on. Genuine love isn’t blind. It sees what must be seen, says what must be said, does what must be done.

As I’m writing you this letter, almost 282,000 of your people have succumbed to COVID-19. (Your eyes are glazing over. You’re tired of numbers. But wake up and listen, will you?) That toll of 282,000 is likely a gross underestimate. Even so, it’s 94 times the number of people killed on 9/11. In fact, as of late, as many or more of your people are dying every single day than the 2,997 who perished in those awful terrorist attacks.

In the aftermath of 9/11, you held public memorials. You planned and built monuments and museums. You passed laws that curtailed our civil liberties, hoping to ensure your safety. You started two wars to avenge those killed.

But now, in this pandemic, with a death toll that dwarfs 9/11’s, where is your outpouring of grief? Why won’t you acknowledge and mourn the scope of your suffering? Why won’t you act more purposefully to slow the spread of this dread disease throughout your body?

You’ve now buried more people from COVID-19 than you did during World War I, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War combined. Yet you seem in extreme denial, unwilling to face facts.

I believe that your inability to grieve stems in part from your reluctance to admit what’s obvious to any sober-minded citizen: This pandemic is a catastrophe, and your response has been a disaster. Every death reminds you of your failure. But rather than let yourself feel remorse and sorrow, you’ve gone numb.

A 61-year-old sculptor based in Bethesda, MD, did her utmost over these past months to wake you up. Her name is Suzanne Brennan Firstenberg. (Forgive my regional pride when I note that she was born in South Dakota, the state where I reside.) Way back in March, Suzanne heard a politician remark that elderly Americans should be sacrificed to the virus in order to preserve the economy. That comment distressed her. Twenty-five years as a hospice volunteer had taught her that “every life is valuable, no death … just a statistic.”

To help you visualize your pandemic losses, Suzanne created an art installation in front of the Washington DC Armory, near the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium. That’s just down the street from your Capitol building. There she began planting small white flags in memory of your citizens killed by COVID-19.

That three-and-a-half-acre field quickly became a space of collective mourning. Every day Suzanne and her team of volunteers would add enough white flags to keep pace with the rising death toll, posted on a billboard on the west side of the installation. Members of the public could submit requests for personalized flags honoring deceased loved ones.

By November 30, the last day of Suzanne’s exhibit, over 248,000 flags were rippling in the breeze, as far as the eye could see. The field in front of the stadium had filled up. White flags had spilled into nearby medians and other green spaces.

“Look at a single flag,” Suzanne would say to visitors. “Now conjure up a story. Think of it as a schoolteacher who just lost her life.” She invited them to imagine everyone affected by that one teacher’s death, including the medical professionals who had fought to save her. “Try to hold all that grief,” she’d say, “and then look up and multiply—” referring to the flags stretching out of sight.

O America! If only you would have taken time to walk in silence among that field of flags and meditate upon what they represented! Doing so would surely have helped you face up to what’s happening. There—in the immensity of your grief—you would have discovered a wiser way forward.

You can no longer visit the field of flags. But somehow you must grieve. You must allow yourself to feel all that you’ve lost, down to the marrow of your bones. You can’t keep lying to yourself, pretending that the pandemic dead don’t matter. Lies have a way of coming back to haunt us. If you ask me, far too many ghosts are already wandering around, from coast to stricken coast.

Listen … can you hear the veteran in Queens playing “Taps” on his bugle at sundown? Can you see the billboard-sized portraits of the dead displayed along the streets of Detroit? The hundreds of handmade roses hung on fishing nets in East Los Angeles? The candlelit rows of empty chairs on the public square in Phoenix? The wall of broken paper hearts in Atlanta?

I’m begging you, America: Open your mind and your heart.

Don’t leave us to grieve alone.

December 1, 2020

November 30, 2020

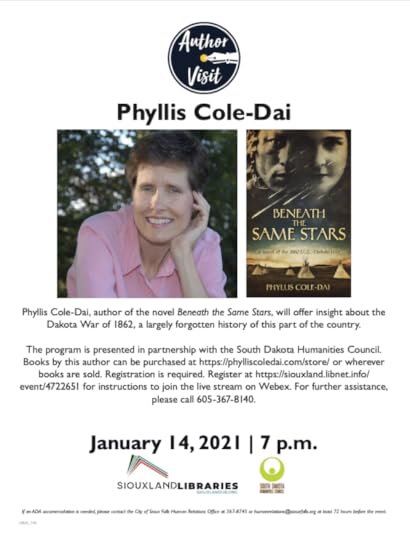

Phyllis to Co-Host Solstice Event

“The Day the Sun Stands Still”:

A Solstice Hour of Storytelling & Poetry

An online gathering led by Phyllis, Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer & James Crews

Monday, December 21, 6:00 to 7:00 p.m. (Central Time)

Tickets: $15 or Pay What You Can

Pause with Phyllis, Rosemerry & James around an imaginary fire to mark the shortest day of the year. Through stories, poems, and music we’ll reflect together on this transition between seasons and celebrate the coming of the light. The evening will leave you with a renewed sense of purposes and belonging, ready for whatever challenges lie ahead.

This will be a Zoom event. Purchase tickets here.

Phyllis will co-host this event with her friends and fellow poets Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer and James Crews. Rosemerry co-hosts “Emerging Form” (a podcast on creative process), “Stubborn Praise” (an online poetry reading series with James Crews) and “Secret Agents of Change” (a surreptitious kindness cabal). Her poetry has appeared in O Magazine and Poetry of Presence, on A Prairie Home Companion, PBS Newshour, and her daily poetry blog, A Hundred Falling Veils. Her most recent collection, Hush, won the Halcyon Prize.

James is the author of four full-length collections of poetry, The Book of What Stays, Telling My Father, Bluebird and Every Waking Moment. His poetry appears or is forthcoming in Ploughshares, The New Republic, New York Times Magazine and The Sun, among other journals. He is also the editor of the anthologies, Healing the Divide: Poems of Kindness and Connection and How to Love the World: Poems of Gratitude and Hope, forthcoming in April 2021. He lives with his husband in Shaftsbury, Vermont and hosts the bi-monthly show, “Stubborn Praise,” with Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer.

November 23, 2020

“Making Room at the Table”

Lost in the heart of a wild forest, you stumble upon a farm, generations old. It’s an impossible thing—a working farm smack-dab in the middle of dense, dark woods—but here it is: a huge red barn, a cluster of outbuildings, and a three-story brick house, all carefully maintained.

Entering the barn, you find the mow stacked high with hay. The stalls and pens are fat with animals. Out back, the smokehouse is crowded with hams and sides of beef. The root cellar’s crates and burlap bags are bulging with apples and pears and potatoes and carrots and onions….

You step up onto the front porch of the house and open the door. Like many farmhouses, it isn’t locked. Somehow you know that you’re welcome here without needing to be told. You walk right in.

Once inside, you find the rooms unremarkable, except for the fact that each is a garden plot. Corn stalks, vining cucumbers, melons and squash, rows of beans and peas and pepper plants, bushes of basil, stands of lavender, flowers of every imaginable sort are growing straight up out of the floor.

You come across a man tending the garden, planting, weeding, pruning, harvesting. This master gardener seems as ageless as the soil he tills. He’s so absorbed in his tending that he doesn’t notice you. Somehow you understand that while this man might live in this house—this bountiful earth become home—it doesn’t belong to him. He belongs to it.

Finally, in the depths of the house, you enter what must be called, despite its rich vegetation, a dining room. It’s filled with tables covered with starched white linens. The sight of these tables stuns you. Suddenly you’re aware that you aren’t alone in the house. The tables are clear evidence: there must be multitudes here; multitudes who, just like you, were not so long ago traipsing through the forest, and have somehow ended up here, their presence long expected. Multitudes who, just like you, need to eat.

This is the moment you wake up. You’re no longer a mere sightseer in this house, a tourist just passing through this earth become home. You get it now: you have both place and purpose here.

A woman appears out of nowhere, elderly but by no means frail. Like the gardener, she’s very old, yet somehow beyond the reach of time. She’s obviously the keeper of this house, the maker of this home. You think of her as Grandmother Earth.

And what does Grandmother do but immediately put you to work. She knows that having you help set the table for the unseen multitudes will help prepare you to actually sit down and eat with them, when the time comes. It will help you regard their lives as equal in worth to your own.

She hands you a tall stack of plates to set around the table—not big dinner plates, but little bread plates. They seem to signify the wisdom of desiring and consuming only what one truly needs. Given the linens and other finery on the tables, you would expect these dishes to be bone china. But they’re everyday dishes, cracked and chipped. Still, they’re sufficient for what they must do, even as you are.

You take the bread plates from Grandmother, and, without needing to be asked, you begin setting them around the tables. It’s precisely now, when you begin to help, that the tables are suddenly overflowing with all kinds of food: platters of fried chicken and roast beef, tureens of soup, bowls of mashed potatoes and creamed spinach and corn, brimming gravy boats, pans of fruit cobbler, filled pies…. Endless food—more than any holiday meal you’ve ever seen.

As you’re trying to squeeze in the bread plates among the serving dishes, you speak for the first and only time. You ask Grandmother a single question. Not “Will there be enough food to feed everyone?” Not “Does everyone deserve to be fed?” No, what you ask over your shoulder is this: “Will there be enough room for everybody at the table?”

“Enough room?” Grandmother says, with a chuckle. She stands there, hands on hips, a bemused look on her face, as if she’s been asked this question every day for the last century. “Of course, there’ll be room! Not everyone will be fed here—there are thousands and thousands of rooms in this house—but everybody has a place at the table.”

* * *

I dreamed this dream while living by choice for 47 days on the streets of Columbus, Ohio. I recount that story in The Emptiness of Our Hands, co-authored with James Murray, my dear friend and fellow street dweller. More than 20 years have passed since our season on the streets, yet this vivid dream is always running in the background of my days. I consider it a slight parting of the veil between What Is and What Could Be.

Are we willing to find room at the Great Table for the entire human family, even for those we’d rather turn away? Are we prepared to make room for one another?

The Great Feast is meant to be an everyday occurrence; every day, we take up anew the Great Work of laying it again and welcoming one another to the Table. Whatever we accomplish this day is enough. Tomorrow, if we’re lucky enough to be alive, we have the privilege of starting in all over again.

I’ll see you in Grandmother’s House.

November 16, 2020

“What If I Said You’re Beautiful?”

How does it feel to be beautiful? (Yes, I’m talking to you.) In my mind, that’s what you are, every last one of you. I’m not talking about what you look like—I’ve never laid eyes on you. I’m talking about who you are, with all your struggles and strengths, your doubts and dreams, your quirks and questions, your talents and troubles…. Beautiful. I don’t have to know you to say that. If you were born into this life, that’s all the evidence I need.

What I think of you, though, isn’t as important as what you think of you. If you don’t love yourself, if you’re not grateful to be alive, it’s apt to show, one way or another.

So, let me ask you now: Do you believe that you’re beautiful?

Last week I watched an hour-long video filmed by Thoraya Maronesy. Thoraya has a popular YouTube channel dedicated to interactive projects with strangers. Her stated goal is “to share as many real stories as possible in [her] lifetime.” Often she asks people on camera a tough question, like “What’s the loneliest you’ve ever felt?” “What’s your greatest challenge right now?” “Who is one stranger you still remember?” “How are you doing, really?” You get the idea.

For this episode, though, Thoraya recorded the reactions of random individuals when she told them simply, “You’re beautiful.” Most of her subjects—an endless parade of ages, colors, and backgrounds—were taken aback by her words. Nearly all of them seemed touched, in different ways.

When the video ended, I distilled those beautiful people into a poem:

When I Said You’re Beautiful

When I said You’re beautiful, you

stared at me without speaking.

Shook your head.

Frowned.

Chewed harder on your gum.

Opened your eyes wide.

Arched your brows.

Sighed.

Stepped back in shock.

Hid behind your shades.

Adjusted your hat.

Blushed.

Glanced away.

Tucked strands of hair behind your ears.

Scratched at your whiskers.

Struck a pose in fun.

Smiled behind your hand.

Beamed a grin.

Laughed as if I’d told a joke.

Gazed at me calmly.

Grimaced.

Bit your lip.

Wiped away tears.

Covered your face.

Said You’re calling me beautiful?

Really?

What do you mean?

Only my mom tells me that.

Stop.

I can’t talk about this….

Precious to hear you say so—sometimes I forget.

I’m beautiful in my own way.

It’s one of those things you want to tell yourself

but you never fully believe.

I work on it. Every single day.

You’ve got to be at peace with yourself.

You’ve got to know your worth.

Beauty comes from within.

Everyone should wake up in the morning

and like what they see in the mirror.

The world needs more of this.

That’s kind. That’s sweet.

You just made my day.

Thank you. Thank you.

You’re beautiful, too.

In these days of isolation and social distancing, I’ve started to tell people, in a friendly way, that I think they’re beautiful. Nobody has to earn my praise. By seeing them as beautiful from the inside out, I prepare myself to treat them as beautiful, from the outside in.

Beautiful friends, how easily we can spread love and healing in this world, just by what our lips say.

What If I Said You’re Beautiful?

How does it feel to be beautiful? (Yes, I’m talking to you.) In my mind, that’s what you are, every last one of you. I’m not talking about what you look like—I’ve never laid eyes on you. I’m talking about who you are, with all your struggles and strengths, your doubts and dreams, your quirks and questions, your talents and troubles…. Beautiful. I don’t have to know you to say that. If you were born into this life, that’s all the evidence I need.

What I think of you, though, isn’t as important as what you think of you. If you don’t love yourself, if you’re not grateful to be alive, it’s apt to show, one way or another.

So, let me ask you now: Do you believe that you’re beautiful?

Last week I watched an hour-long video filmed by Thoraya Maronesy. Thoraya has a popular YouTube channel dedicated to interactive projects with strangers. Her stated goal is “to share as many real stories as possible in [her] lifetime.” Often she asks people on camera a tough question, like “What’s the loneliest you’ve ever felt?” “What’s your greatest challenge right now?” “Who is one stranger you still remember?” “How are you doing, really?” You get the idea.

For this episode, though, Thoraya recorded the reactions of random individuals when she told them simply, “You’re beautiful.” Most of her subjects—an endless parade of ages, colors, and backgrounds—were taken aback by her words. Nearly all of them seemed touched, in different ways.

When the video ended, I distilled those beautiful people into a poem:

When I Said You’re Beautiful

When I said You’re beautiful, you

stared at me without speaking.

Shook your head.

Frowned.

Chewed harder on your gum.

Opened your eyes wide.

Arched your brows.

Sighed.

Stepped back in shock.

Hid behind your shades.

Adjusted your hat.

Blushed.

Glanced away.

Tucked strands of hair behind your ears.

Scratched at your whiskers.

Struck a pose in fun.

Smiled behind your hand.

Beamed a grin.

Laughed as if I’d told a joke.

Gazed at me calmly.

Grimaced.

Bit your lip.

Wiped away tears.

Covered your face.

Said You’re calling me beautiful?

Really?

What do you mean?

Only my mom tells me that.

Stop.

I can’t talk about this….

Precious to hear you say so—sometimes I forget.

I’m beautiful in my own way.

It’s one of those things you want to tell yourself

but you never fully believe.

I work on it. Every single day.

You’ve got to be at peace with yourself.

You’ve got to know your worth.

Beauty comes from within.

Everyone should wake up in the morning

and like what they see in the mirror.

The world needs more of this.

That’s kind. That’s sweet.

You just made my day.

Thank you. Thank you.

You’re beautiful, too.

In these days of isolation and social distancing, I’ve started to tell people, in a friendly way, that I think they’re beautiful. Nobody has to earn my praise. By seeing them as beautiful from the inside out, I prepare myself to treat them as beautiful, from the outside in.

Beautiful friends, how easily we can spread love and healing in this world, just by what our lips say.

November 10, 2020

Phyllis to Host “Lightening Those Holiday Blues”

As the holidays approach, we struggle with the harsh realities posed by a pandemic and political turmoil. Our Thanksgiving table will be emptier this year. Many of our cherished customs will be disrupted, perhaps even abandoned. We may feel so burdened by grief that gratitude seems impossible. A dark winter of uncertainty looms.

Together we can lighten our holiday blues.

Join Phyllis in this gathering of sharing and support on Monday, November 23, 2020, 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. (Central Daylight Time). We’ll acknowledge what hurts. We’ll explore and honor what helps us heal, through …

contemplative silencesoulful poemsthe practice of journalingheart-to-heart discussion, and more.Tickets for this Zoom event are $20. Get yours now.

November 9, 2020

“Same Air, Same Ground, Same Heartbeat”

Back in college, 40 years ago, I lived with Leah (name changed) on the same dorm floor. She was a brilliant woman who, by age, should still have been in high school. An aspiring lawyer, she could already out-argue every professor.

One day, while attending a religion conference together, Leah and I sat in on a session discussing homosexuality and the Bible. The scholar maintained in his lecture that homosexuality was deviant and sinful. Afterwards, I told Leah how impressed I’d been by the presentation. She was strangely quiet. I kept talking, filling the awkward silence, until I ran out of steam. That’s when she said, “You do realize that I’m gay, don’t you?”

I stared at her, stunned, as she walked away.

A year later, Leah and I both took part in a semester-long urban studies program on the South Side of Chicago. We lived with other students in an old townhouse. We weren’t really friends anymore. She didn’t trust me, and I didn’t understand her. She made me uncomfortable.

Late one evening, I was studying in my cold, dingy room in the basement when Leah appeared in the doorway, clutching her forearm. Blood was dribbling fast on the floor. “I’ve cut myself bad,” she said, in a panic. “Nobody can know!”

I didn’t ask questions. I tied a tourniquet, then wrapped her arm in a towel. “We’ve got to get you to the ER,” I said. Fortunately, a hospital was just up the street.

“I can make it there on my own,” she said. She nodded at the floor. “Somebody will see the blood—it’s everywhere! They’ll send me home! Please—you’ve got to help me!”

“Go,” I said, shoving her out my door. “I’ll take care of it.”

I don’t remember mopping up that night. But I do remember the dark trail of blood that led up the rickety steps from the basement into the kitchen; up the steep back stairs to the second floor; down the hall, into Leah’s room.

It was while mopping up that blood that a big part of me shifted. I realized how little I knew about homosexuality. That’s why Leah had made me uncomfortable: I felt threatened by my own ignorance. Now life was inviting me to worry less about abstract debates of “right and wrong” and more about the actual well-being of people—all of them my equals, all as worthy as myself of compassion and respect. I felt my part in Leah’s cutting. Along with so many others who inhabited her world, I’d burdened her with narrow-mindedness and prejudice. I’d made her feel “less than,” to the point she’d sliced open her own flesh in distress. Then, having nowhere else to turn, she’d had to seek my help.

I finished with the blood. Hours later, Leah returned from the hospital, pale and frightened, her arm heavily bandaged. She told me about her family’s rejection of her; about her struggle to reconcile her sexual identity with her faith; about her addiction to cutting, She promised to seek help from professionals. I promised to be a supportive friend.

Somehow nobody else in the house that night saw the trail of blood. I’ve carried the secret ever since. After graduation from college, Leah and I lost touch. I can only pray that the rest of her story has been happy.

How do we learn to accept the “Leahs” of our lives rather than causing them to suffer? We might begin by naming who we’re afraid of, exactly. Then, we might commit to informing ourselves about their lives, from their perspective. If we’re lucky, we can do that in their company, sitting around a table, listening to their stories. If not, we can read books by people similar to them. We can workshop. We can watch films. We can do whatever’s required to disarm our fear.

These days it seems that we’re not very curious about one another. Instead, when differences reveal themselves, we quickly become suspicious or resentful. We think we already know everything we need to know about everybody else when in fact we only know our own opinions. On that limited basis, we judge, exclude, demonize, and attack. By what we think or say or do, we help create the conditions that will make the “Leahs” around us bleed, simply because they’re not like us.

Who, I wonder, will be left to mop up?

I’m a white, straight, progressive, crazy woman writer living in Brookings, South Dakota USA. I’m not alive to make you become more like me. I’m here to be who I am, and to recognize who you are. So tell me what it’s like, being you in this world. I promise to listen with respect. I promise to try to understand. No matter where you may live or how we may differ, I give thanks that you and I are here together, breathing the same air, walking the same ground, with hearts that beat the very same way.

November 2, 2020

“What Could Keep You Warmer Than This?”

Last week I told you about my red winter coat—how it helps to keep me warm not only by what it’s made of but also by what’s on it: signatures of people who believe in the power of community; who understand that their lives are bound up with the lives of others; who know that they belong—or who want to belong and are struggling to find a way.

Entering pandemic winter in South Dakota, isolated and socially distanced, I realized that my coat would have no signers this year, unless I had some extraordinary help. So I invited you to sign by proxy. “Drop me an email,” I said, “and tell me how to inscribe your name. I’ll be happy to carry you on my back.”

Soon after I sent that edition of Staying Power, my invitation was also published in Daily Good: News That Inspires. I woke up that morning to a flood of emails from the U.S., Malaysia, India, Spain, Canada, New Zealand, Austria, Australia, France, South Africa, Great Britain, Belgium…. Now, at week’s end, I’m trying to draft this follow-up between tings on my laptop—more incoming requests from you. From the world. Forgive me if I have to mute you for an hour to concentrate on this. And if you’ve written me and haven’t heard back yet, please try again. This week has been a three-ring circus of community.

I’m not complaining. Believe me. You amaze me. You’ve moved me to tears.

Many of your messages have included snippets of your stories: The health care worker exhausted from the pandemic. The English as a Second Language teacher needing good news after a long day at school. The woman wanting to encourage her spirited 10-year-old granddaughter to keep building community. The reader who feels exceptionally alone after a recent move to a new state. The couple depressed by the election season and the divisions in their country. The woman unable to sleep, worrying about the coronavirus and wildfires. The 76-year-old widow, separated from her family, “working hard to monitor what she feeds her soul each day.” The reader whose little sister had died of cancer only hours before. The man signing for both himself and his differently abled friend, who speaks through a voice synthesizer on a computer. The “hermitess” in rural Montana who fills her hours knitting, weaving, sewing, and walking the mountains with her dog. Multiple people who, having struggled for a lifetime “to fit in and belong,” are starting to carve out their own spaces to be. The woman whose sister and husband are both terminally ill. The aged reader, isolated since March 6th except for grocery shopping, who writes, “Seclusion is changing me. I trust it all”….

So many stories. So many of you, so grateful or so hungry to belong, using this very simple act of signing a coat to affirm that you matter—and that everyone and everything else matters, too.

Often you have also shared with me details about your names—treasured nicknames; names with sacred meanings; birth names written in mother tongues; reclaimed names; monastic names; maiden names used as a way to bless deceased parents; invented names, representing parts of you that you’re trying to recover or nurture or become; shortened names, so as not to take up too much space. (That’s been a major worry for many of you—the coat running out of room. O ye kind folk, have more faith! This coat can carry the world.)

Some of you asked me not to bother signing your name. “It’s not important,” you said. “It will pass.” Instead, you asked me to inscribe an affirmation, alongside the messages sent by others: Hello everybody, I’m here with you…. Never Give Up. Love Never Fails…. One Family on Earth…. May all beings have enough of everything…. You are, therefore I am…. You Matter…. “Le deseo paz y tranquilidad, amor, paciencia y compasion a todos que mas lo necesiten. Nos tenemos que amar unos a otros.” (I’m just learning Spanish, but I think this translates to something like: ”I wish peace and tranquility, love, patience and compassion to all who need more of it. We have to love one another.”)

You’ve requested that I write your names with hearts and smiley faces and peace signs and paw prints and trefoils and maple leaves. One of you typed in red ink, to honor the red coat. Over and again, these emails have come with precious tears. Lots of tears. Probably every third email mentioned tears. (I wipe them gently from your eyes and cheeks.)

Some of you are now planning to start your own community coats. (Go for it, people!) Others of you intend to ask relatives to add your name to a piece of clothing they wear regularly, to bind you together. (I love it!) One of you asked permission to send me your signature on a piece of cloth that I could tuck into a coat pocket for other people to sign. (Sure, my pockets are bottomless.)

“What keeps you warmer,” one of you wondered, “the coat or the `everyone’ on it?”

You know the answer. You can’t separate the coat from Everyone, or Everyone from the coat. I’m warmed by you all. And I bless you even as you have blessed me:

Metta. As-aalaamu alaykum. Mitakuye oyasin. Beannacht. Mahalo. Kia ora. Namaste….* Deep peace.

*Translations of these blessings you gave me: Metta is Pali for “lovingkindness.” As-aalaamu alaykum is Arabic for “peace be upon you.” Mitakuye oyasin is Lakota for “All are my relatives.” Beannacht is Gaelic for “blessing.” Mahalo is Hawaiian for “thank you.” Kia ora is Maori for “have life.” Namaste is Hindu for “I bow to you.”