Phyllis Cole-Dai's Blog, page 13

August 30, 2020

“The Table and the Tap”

This week I learned the Italian word abbondanza. Don’t you love how it rolls off the tongue? Can’t you just hear it on the lips of Luciano Pavarotti or Leontyne Price or another great opera singer? Abbondanza. The word begs for hearty support from the belly. Fill those syllables! Ab-bon-dan-za!

I’ll tell you what the word means in a minute, but for now, enjoy the sound of it. Saying abbondanza fills my mind with visions of a rustic table overlooking a lovely vineyard in Sardinia or Lombardo. It’s evening, the sun no longer hot. Spread on the table is a feast of pasta dishes and homemade breads, cheeses and olives, fine wine. For dessert, there’s the promise of a refreshing gelato, with pastries and coffee…. Can you picture the scene? Care to join me there for dinner?

For me, abbondanza is one of those magical words whose sound perfectly embodies its meaning. In English, it translates to “abundance.” Notice that “dance” is built into its spelling. This is a word that almost breaks the festivity meter. Abbondanza!

Don’t let me fool you. Unlike the friend who taught me this word, I’ve never stepped foot in Italy, except in my imagination. But I do have a strong sense of what abbondanza is.

Some folks believe that having abundance is about accumulating wealth. It’s about getting what we can and holding onto it, no matter what. It’s also about fearing that we’ll never get ahead if other people get too much; or, if they have too little, they might come after whatever we’ve got—especially if they look or sound different from us.

What I’ve just described isn’t abundance, though. It’s ugly materialism. It’s putting possessions and comfort ahead of everything else, including the deepest, most abiding values that we human beings possess, like generosity, compassion, humility, and gratitude. It’s putting money and property ahead of that shared table in the vineyard, and wherever else strangers may gather and learn (despite their differences) to become friends.

Marianne Murphy Zarzana, a poet-friend of mine, lives by the mantra “Make me an open tap.” That’s a commitment to abbondanza. Wherever Marianne turns her attention, she helps lay the feast, build the peace, spread the light—through her poetry, yes; through her teaching and mentoring, yes; but most of all, through being present. With full intention she gives herself to whatever moment she’s in and whomever she’s in it with.

We’re all living through tough times. Too much sickness and death, too much fearmongering and lying, too much anger and hatred, too much racial injustice, too much poverty and economic stress, too much isolation, too much denial, too much devastation from drought and derecho winds and wildfires and hurricanes … too much, too much, too much.

Such chaotic times might tempt us to turn off our tap, or at least reduce it to a trickle. Hold back. Pull in. Cling with desperation to what we have.

Let’s try instead to trust in the overflow of abbondanza—of Goodness, sharing itself. Abbondanza is bigger than any threat we face, if only we let it flow. When the tap of our lives is wide open, it gushes up like water from the limitless depths of our spirits and rushes out into the world, bringing healing and sustenance. It doesn’t happen by magic—it takes vision and hard work. But nothing at all happens if we let fear and despair shut off the tap.

All around us, small, frightened voices are saying, “What you need is gone.” The voice of abbondanza says, “What you need is here. Even now.” What we need is within us, among us, around us—just waiting to be tapped. Let’s not pray for a new earth or heaven, Wendell Berry suggests in his poem “The Wild Geese,” but for “the ability to be quiet in heart, and in eye, clear. What we need is here.”

I’ll never say the word “abundance” again without feeling the power of abbondanza behind it.

Out in the world’s vineyard stretches a table with a feast meant for us all. I’ll meet you there.

August 24, 2020

“A Pandemic Letter to My 17-Year-Old Son”

Son Nathan exploring the headwaters of the Mississippi River at Itasca State Park, MN, this summer.

Starting when you were just a toddler, you’d crawl into my lap to play a game. I’d lay hands on each part of your body, naming it aloud. We’d begin with the “grass” of hair on your head and slowly work our way down to your “piggy” toes. You soon learned even the regions of your brain, the organs in your torso, and your seven chakras.

Our game wasn’t just about naming and knowledge, though. Even more, it was about attention and loving touch. You craved the physical sensations as my hands tenderly pressed and poked, tickled and caressed in a safe, predictable way. My touching made you laugh, but it also calmed and comforted you. When you were sleepy, you asked for “body parts.” When you were sad, “body parts.” When you had a bad cold, “body parts.” At least once a day, “body parts.”

Every round of “body parts” took a half-hour or more. To be honest, I sometimes didn’t want to play when you did, especially when tired. But our time together was too precious, too fleeting, ever to turn you down. When you finally outgrew my lap, and our game ended, how I missed that intimate ritual! We had to invent new ones.

Now you’re nearly eighteen, headed into your senior year. After carefully researching and weighing the options available in our school district this fall, you’d settled on a hybrid of online and in-person classes (including Human Anatomy). But the school has just informed you that it won’t be offering any of your courses virtually. You have no choice but to attend in person and assume the risks.

You feel betrayed by the process. So do I.

Yesterday we sat together on the couch, discussing this and other grown-up stuff. Part of you is a man already; another part, you told me, “isn’t ready for adulthood, and doesn’t want to be.” Part of you wants to tell me everything; another wants to hide. Part of you doesn’t understand how I can be “so happy all the time”—how I can sing and joke in the middle of a pandemic, with the country falling apart, two sick parents at a far distance, and a never-shrinking pile of projects. Meanwhile, another part of you is trying like mad to “protect” me from anything that might cause me unhappiness. These are the “parts” we’re touching now, the tender game we play.

I want you to know that I still see the boy in you. As your mother, I’ll always still see the boy, no matter how old you get. But I also see—and believe in—the beautiful man you’re growing into, even when you can’t.

I want you to know that whenever you have something to say, I’ll be here to listen, and you never need to hide anything from me because you’re afraid or ashamed. But I also don’t expect you to tell me everything. You have a right to privacy. You get to decide which of your soul’s doors to invite me through. I should warn you, though, I might sometimes knock on a closed door, and if you don’t answer, I might plop down on the floor and wait. (Don’t be surprised if I start singing.)

I want you to know that, despite what you think, I’m not happy all the time; that I sometimes sing or joke because I’m unhappy. These things help me cope, like having a good cry, or taking a long walk, or venting to someone I trust. To me, life isn’t about being happy. It’s about making my peace with the fact that life, while amazing, is hard. (I’m still working on that.)

I want you to know that you don’t need to protect me, though I love your dear heart for wanting to. I’m not made of glass. I’m suede—soft leather, but tough. My love for you is bigger than any pain I could ever suffer because of you.

Here’s my hope: Wherever you go, whenever you’re anxious or angry, afraid or lonely, you might remember sitting on my lap as a little guy. Feel my hand resting lightly on the crown of your head. Over your heart. On your shoulder. And remember in that moment that wherever I am, and whatever else I’m doing, I’m remembering you.

August 17, 2020

Want a cup of coffee?

Phyllis invites you to join her new Facebook group, “Coffee Break with Phyllis Cole-Dai.” Launching today, this private group will be an informal hangout exclusively for her newsletter subscribers. She’ll get to know you and other readers better, dive into fun discussions, and hold special gatherings by video chat.

Join today, and invite your Facebook friends to do the same. By signing up, you’ll automatically subscribe to her mailing list. Here’s how to become a member: Go to the group page. Once there, click “Join” and follow the prompts. You might also want to click “Notifications” (beside “Join”) and select “All” so that you don’t miss anything important.

We can all use a friendly breather, can’t we? So pour a cup of your favorite beverage and get comfortable.

“The Same Job As Always”

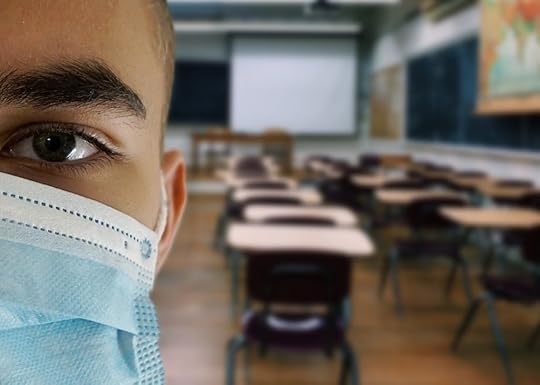

These are anxious days at our house. Son Nathan is a rising senior in high school. He should be looking forward with excitement to his last year with his classmates. Instead, he has been researching the pros and cons of returning to school in person, taking all of his courses online, or doing a mixture of both.

He’s torn. He feels keenly responsible for protecting everybody’s health, including his own. Against this he must weigh an urgent need for companionship, a deep desire to play again in the orchestra, and a strong sense that classrooms would better prepare him for college than a screen. What should he do?

This isn’t a decision that a 17-year-old should have to make.

By age, Nathan stands on the brink of manhood. But the fact is, he has already arrived. His father and I can see it. The pandemic has prematurely ushered him out of the relative ease of adolescence into the complexities of adult life. He won’t be making this decision about his schooling alone, but Jihong and I have given him the final word. Nathan has earned the right to make his own informed choice by coping so well with the ordeal of these past five or six months.

I won’t heap on you my opinions about our country carrying out a grand experiment in public health by reopening schools amidst a surging pandemic. I understand the arguments on all sides. There’s no perfect solution that will satisfy everyone.

I will tell you, though, that I’m afraid. And my fear is stoked by grief. Too many people have already become ill. Too many have died. Too many are still struggling to recover. Too many have lost their livelihoods, even their homes. My fellow citizens, including my friends, neighbors, and loved ones, are experiencing so many types of suffering, I can’t begin to list them all.

As a nation, we’re tired of being in this mess. Some of us want—even need—our children to return physically to school. Others of us can’t bear the thought of it. How do we come together?

My mind runs back to when Nathan was 14. This vibrant, skinny kid who rarely had a sniffle suddenly crashed with what’s called “complicated pneumonia.” In the middle of the night, a medical team life-flighted him to a larger regional hospital. Jihong and I sped in our car down the dark interstate, chasing after the helicopter. I was clutching one of Nathan’s old stuffed animals, holding on as if it were him. Throughout the preceding hours, I’d managed to remain calm, but now I dissolved into sobs.

All at once, I heard a voice. Not a human voice—Jihong, who was driving the car, didn’t hear it—but it was a voice nevertheless. It asked me a simple question that instantly set me straight. The question itself is insignificant here; what matters is the response that welled up in me. I realized that, despite the crisis we were facing, my job as Nathan’s mother was the same as it had always been: To love him. To be there for him, with every ounce of me. While my love couldn’t guarantee that he would survive, it could guarantee that he’d never feel alone in his suffering.

After nearly a week in grave condition, Nathan was slowly brought out of sedation. Once he was alert enough, he gestured for something to write with, unable to talk because of the ventilator. We gave him a small whiteboard, on which he weakly scribbled two words: “Thank you.”

The takeaway from my story? When it comes to our nation’s children (and those who teach and tend them in our schools), our collective job is no different now than it has always been. Our job is to love them. To be there for them.

Our love won’t guarantee their safety, but this much it should guarantee: That they’ll never feel alone in this ongoing crisis. That we’ll provide them with whatever’s necessary to help them survive and thrive. That we’ll give them such skilled care and emotional support, the first thing they’ll want to say when this pandemic ends is “thank you.”

(Image by Alexandra_Koch from Pixabay)

August 10, 2020

“The Dugnad in Our DNA”

Dugnad. Say it with me: dugnad (doog-nod). It’s a Norwegian word I learned this week; an ancient word, traceable to the Viking Age, when villagers would labor together to bring ships ashore after long seafaring trips. That’s dugnad. In later centuries, Norwegian farming communities would work together to prepare for harsh winters and to survive other hardships. Dugnad. In the 1940s, Norwegians rallied to resist five brutal years of Nazi occupation. Dugnad.

Traditionally, dugnad is the collective effort of individual Norwegians who sacrifice their personal desires, and allow their own sense of “normal” to be temporarily disrupted, for the benefit of their community or country.

On March 12 of this year, after the first Norwegian died from COVID-19, Prime Minister Erna Solberg called for a national dugnad. She asked everyone in Norway to band together to reduce the spread of the disease. As a result, the country contained the outbreak, avoiding massive numbers of infections and deaths.

To my knowledge, I don’t have any Norwegians in my family tree. But a concept similar to dugnad lives in my DNA. I call it “love of the neighbor,” or “commitment to the common good,” or “civic duty,” or even “patriotism,” in the best sense. I credit my upbringing, my spiritual life, and my liberal arts education, among other things, for cultivating in me a deep respect for others. But I suspect that I was born with the seed of this sensibility, just as you were. It’s part of our nature as human beings. How could it not be? We’ve had to count on one another to survive since the dawn of history.

Sometimes, though, that seed of Us gets buried so far down inside, we don’t even realize it’s there. We lack fellow feeling. We’d rather do our own thing than devote ourselves to a common purpose, even in a crisis.

I keep hoping that we can find ways to strengthen our faith in one another. Maybe we could start, right where we are, by sharing frankly what we believe in—one person speaking at a time, while the rest of us listen. I mean, really listen, without mentally picking apart what we’re hearing. Listening so well that when the speaker finishes, we offer only our thanks, without commentary. We now understand better, and that’s enough.

Let’s try it, shall we? I’ll speak first, if you don’t mind, since I’m already at it:

I believe in greeting each new day with a bow of gratitude. In nurturing the promise of children. In being faithful to friends. In being kind to strangers. In trying to love without clinging.

I believe in neighborly potlucks and pots of coffee. In bicycles and flowers and porches. In silence and solitude. In sanctuaries and wilderness. In letting things be. In sometimes losing myself in order to find myself again. In the necessity of pulling weeds in my garden. In the delight of digging potatoes and giving them away. In striking a fine balance between freedom and responsibility. In the power of naming. In the duty to vote.

I believe that the universe is big and our place in it isn’t even a speck, yet what we do and say matters. I believe that joy is fleeting. That life is hard. That equanimity is possible, even in the midst of suffering. That life is a fragile web of kinship. That death is always close. I believe in the smallness of what I know, the value of what you know, the vastness of what we can know together, and the existence of what we can’t know at all.

I believe in trees, especially old ones, and in the ever-changing sky, which has no borders. I believe that what’s good for me is bound up with what’s good for you. I believe in stepping over the line of what’s nice for the sake of what’s right. I believe in poetry and stories and music and art and dreams—everything that helps us to question who we are and to imagine who we might become, together.

I believe in you….

I could keep going, but now it’s your turn to speak, if you’d like. I’m listening.

August 3, 2020

“View from the Top of the Temple”

When I was a sophomore at Goshen College, I traveled to Belize for a Study-Service Trimester (SST). This was back in 1982, just a year after Belize had been granted independence by the United Kingdom. About the size of Massachusetts, the country shares borders with Mexico and Guatemala. It’s a beautiful place. Perhaps you’ve had the good fortune to visit.

Except for family excursions into Canada, my trimester in Belize was my first time outside the United States. I returned home with a suitcase stuffed full of questions about what it meant to be American, Caucasian, female, middle class, capitalist, and Christian. Two of the people who helped load up my bag were Roy and Ethel Umble, the leaders of our SST unit.

About three weeks into the term, Roy and Ethel took our group to the ancient Mayan ruins of Xunantunich. Located in the jungle less than a mile from Guatemala, the site dates back to the first millennium B.C.E. Its most prominent feature is a temple pyramid dubbed El Castillo (“The Castle”). The top of the pyramid measures 130 feet, making it the second tallest structure in all of Belize. And that’s where we were on our tour—at the very peak, 13 stories up in the air—when my bad knee popped out of joint. I collapsed with a moan. Now I had much more than my fear of heights to contend with.

After composing myself, I made my way down the ruins, scooching on my bottom. When I finally reached the ground, I sank down in the grass under some trees and chugged water. I wondered how I would ever manage the mile hike back through the jungle to our rattly old school bus.

Roy and Ethel grasped my hands and hoisted me to my feet. I tested my swollen knee. It had been a chronic problem since a middle school injury. Within a few months, I would undergo surgery, hoping to repair it. But for now, it couldn’t bear weight.

Roy stood on one side of me, and Ethel on the other. They were both gray-haired retirees with slim builds. “Put your arms around our necks,” they told me. “We’ll be fine.” The rest of our group had disappeared, headed back to the bus.

The ordeal that followed was hot, muggy, buggy, painful, and torturously slow. But somewhere in that stretch of jungle, the three of us stopped being acquaintances and became friends. We bonded for life. In later years, whenever we looked back upon our decades of steadfast relationship, we all pointed to Xunantunich as the beginning. We didn’t realize on that day what was happening, of course. In fact, in my journal entry, I devoted only three quick lines to the drama surrounding my knee.

Now, almost four decades after Belize, Roy and Ethel are both gone (though they still live in me). The suitcase of my life remains stuffed with questions. I don’t even bother wrestling with it anymore, trying to zip it closed.

This matter of “helping and being helped” takes up a ton of room in my bag. It also takes up a ton of room these days in our nation’s collective baggage. It isn’t always easy to know how to help one another through this crisis, is it? Sometimes, frankly, we’d rather abandon the scene and go sit on the tour bus, leaving the hard stuff behind. We forget that the bus won’t be going anywhere until we’re all on board.

Other times we struggle to hold up those who are hurting. “Put your arms around our necks,” we tell them. “We’ll be fine.”

But sometimes we’re not fine. We’re exhausted. We’re heartbroken. We’re afraid. We’re sick. We don’t have enough money, enough hours, enough hands, enough equipment, enough power, enough answers. What then?

We take a deep breath, and we ask for a little help. A lot, even. There’s no shame in it. Helping one another is a big part of what creates and maintains community. Helping helps make us Us.

Besides, asking for help—like offering it—can lead to great and unexpected things … most especially, perhaps, to friendship, the kind we can always count on to hold us up when we can’t walk on our own.

July 27, 2020

“Birthplace”

Last week our family took a collective breather at Lake Itasca State Park in north central Minnesota. It was our first time there. We camped. We hiked. We biked. We kayaked. And we learned why the pesky mosquito is Minnesota’s state bird—a joke that’s no joke.

Minnesota is famous as “the land of 10,000 lakes.” To be more precise, the state has 11,842 lakes. Itasca is pleasant enough. It’s situated right where the Great Plains meet the coniferous forests of the north and the deciduous forests of the south. You can see all three habitats in the state park. Otherwise Lake Itasca isn’t noteworthy, except as the headwaters of the Mississippi River. That’s right—from there, the mighty Mississippi flows all the way down to New Orleans and empties into the Gulf of Mexico, a meandering journey of over 2,300 miles.

Lake Itasca is in the traditional homeland of the Ojibwe nation. The Ojibwe call it Omashkoozo-zaaga’igan, or Elk Lake. On an expedition in 1832, the American geographer Henry Schoolcraft identified this small glacial lake as the primary source of the Mississippi. In typical colonialist fashion he then promptly changed its name to Itasca, an Indian-sounding word that he coined from Latin, meaning “true source.” Also in colonialist fashion, Schoolcraft forgot to mention that Ozaawindib, an Ojibwe man, had led him there.

Tribal historians say that the Ojibwe people thought Schoolcraft’s obsession with the exact starting point of the Mississippi was rather strange. To them, every part of the “Great River” had equal value. They helped him anyway.

Even now, during the pandemic, tourists are flocking to the little rock dam on the north end of Lake Itasca that officially marks the birthplace of the Mississippi. That dam, like the lake’s name, is not original. Back in the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps poured some concrete, heaped some rocks on top, and created the tiny rapids that still entertains visitors.

For the sake of solitude, our family twice explored the headwaters site around sundown. The first time, as we perched together on some dry rocks amidst the rapids, son Nathan remarked, “I’m sitting at the birthplace of the Mississippi with the woman who gave birth to me.” I nearly swooned.

The three of us returned to the spot a third and final time on our last afternoon in the state park. We wanted to wade the first section of the river. There the Mississippi is a peaceful, winding channel lined with cattails, sedge, wildflowers, and tamarack trees. The narrow, quiet stream never runs deeper than mid-thigh. You can see straight down to its sandy gravel bottom, where young fish dart around your feet. Eventually human sounds recede, and there’s only the swoosh-swoosh of your legs through the water. You don’t speak. You don’t want to intrude. You just want to lose yourself in the landscape. Your breathing relaxes, sinking slowly from your upper chest into your belly. A half-mile later, when you reach the plank steps that signal the end of the walkable portion of the river, you don’t want to leave.

But here’s the thing: From the moment you start sploshing through the water below the rock dam, something’s off. It keeps nagging, like the tiny pebbles slipping into your hiking sandals. All at once, it hits you: To make its way south to the Gulf of Mexico, the Mississippi is headed north. Stop and let that sink in while you empty your shoes. To get where it wants to go, the river has to go somewhere else. It doesn’t force things. It follows the lay of the land.

Look at a map. Trace the Mississippi with your finger; a long-tailed question mark, missing its dot. What causes that curve at the top? North.

Especially during this pandemic, the Mississippi could probably teach us a thing or two about being patient. About trusting the flow of what’s true and necessary to take us where we want to end up. About being content if we can’t see around the bend just yet. About letting whatever stretch of the river we’re on be enough for now—water rippling, birds singing, breeze catching the cattails, and sunshine kissing our tired faces.

July 22, 2020

Phyllis launches My Poetry Studio

This week Phyllis launched My Poetry Studio, a “poetry play space” where she’ll post an occasional poem-in-progress. Each poem will be accompanied by a “play note,” briefly describing the inspiration behind the piece and offering a general poetry prompt. Readers can subscribe to receive new poems in their inbox.

“I’ve always been reluctant to call myself a poet,” Phyllis says. “I’m not well versed in the craft, though I’ve occasionally studied and dabbled. Yet during these chaotic times I’ve been writing more poetry than ever before. It’s very therapeutic.

“I decided to post my poems-in-progress in order to encourage others to read and write poetry, too. Both can be good medicine. I’m not trying to churn out perfect poems. I’m trying to turn out poems that are real—poems that spring from my life and, hopefully, that will resonate strongly with the lives of others.”

If you’d like to join the My Poetry Studio mailing list, do so here.

July 12, 2020

“If You Ever Wonder”

Note: Phyllis included this poem in another recent blog post but has been encouraged to publish it on its own.

If You Ever WonderA response poem for Gloria Heffernan

I want you to know

in these dark days

when all the world

is utterly changed,

one thing that remains

is how we feel

when anyone opens

the book of Us

to a random page

and finds a truth

they had forgotten.

Nurses and doctors,

meat packers and crop pickers,

journalists and janitors,

clerics and counselors,

bus drivers and truckers,

mail carriers and shelf stockers,

first responders and trash collectors,

scientists and governors and cooks,

every essential worker

eats and drinks

from the book of Us.

Pots and pans clang

from balconies and windows

flung wide from street to sky.

We are the cheering crowd, the book of Us

assembled without masks and bound

together between soft covers

by a strong, supple spine.

Every page is sacred text.

Nobody is not essential.

We are the prayer for our ailing world

and this is the beginning of our shift.

“A Bit of Heaven”

Let me tell you about Don. He’s a retired DC firefighter, about to turn 89, living alone in his Maryland apartment. Father of six, grandfather to a tribe, he’s an Irishman, and darn proud of it. Around the start of the pandemic, he dropped me a line out of the blue, a reader offering his take on my novel Beneath the Same Stars. Since then, we’ve struck up a fairly regular email correspondence. We share stories about family escapades, our bad knees, the loved ones we’ve lost and are losing, the dear ones who take care of us and bring us joy. We banter about politics and public health and books and the best way to cook broccoli. We swap original poems. We joke a lot, tossing around dry one-liners.

I’ve never met Don. Yet he calls me “Dearie” and “Kid,” with no trace of sexism or condescension. My impression is that he’s always adopting strangers into his tribe, and I smile to be among them. Perhaps his friendship helps me compensate as I watch my elderly father decline, far from my reach. For the first time, on Father’s Day, Dad didn’t recognize me when we tried a video chat.

In our latest email exchange, Don and I were discussing kindness—how every act of kindness matters; how it’s a “pebble in the water” whose ripples spread in ways we’ll never be aware of. That was a lesson, Don acknowledged, that he carried with him from his twenty years on the streets as a firefighter. He told me how, early in his career, he saw an officer in his department slip some money to a woman standing on the sidewalk, surrounded by her children, staring at the remains of their burned-out apartment. It was something that Don saw this officer do often. The quiet gesture made an impression on him, and through the years, he kept money in his own pocket to do the same.

“I know that kindness happens everywhere, uptown and downtown,” Don wrote. “But when someone is really out of luck, kindness is heavenly.”

On July 2, here in my town of Brookings, South Dakota, a 10-year-old boy went missing. After hours of searching, authorities found his bike and sandals lying in the grass at the edge of a pond. Early the next morning, the Fire Department drained much of the water. A dive team soon located the boy’s body.

His name was Molu Zarpelah. He had immigrated to the U.S. with his mother and sisters from Liberia when he was only four. His father had already come over to establish himself, hoping to provide a better life for his family than he could in his home country.

Molu didn’t know how to swim. But from what I understand, the rising fifth-grader did know how to give the biggest, warmest hugs. How to greet his teachers and classmates every day with high-fives. How to dance for joy and show off his new moves. How to tutor his sisters on their homework. How to dream: he wanted to go to college, then play football for the Philadelphia Eagles.

From his school to his church to his neighborhood, many in Brookings are sorrowing over Molu Zarpelah. Tomorrow the town will join with Molu’s parents and four sisters to celebrate his life, pandemic-style, socially distanced in a parking lot. Then, in the traditional Liberian way, those gathered will walk Molu to the cemetery, a mile away, that his soul might safely reunite with his ancestors in the afterlife.

I didn’t know Molu Zarpelah. But when he smiles at me from every photograph, I feel like I did. And because I’m a mother who can’t imagine my child drowning, I plan to walk in his funeral procession, out of respect for those who cherished him.

“Kindness is everywhere,” Don said, “uptown and downtown.” It’s where you are. It’s where I am. It can knit us together in troubled times; it can help us make the unbearable bearable. It can ripple out, even from the sidewalk near a burned-out apartment or the bottom of a drained pond. It can ripple out from our pockets and from our presence. It can ripple out to everyone in this world who is lost in pain and grief, to surround them with a bit of heaven.