Phyllis Cole-Dai's Blog, page 12

October 26, 2020

“Let Me Carry You on My Back”

Yesterday I awakened to several inches of snow. Today, as I write this, big wet flakes are falling yet again. The world outside my window looks like a holiday postcard, and my family hasn’t even raked our leaves yet.

I just pulled my winter coat out of the closet. Made of quilted goose down, it reaches below my knees. It’s guaranteed to keep a body warm down to -40F. (Yep, it gets that cold here, before the chill factor.)

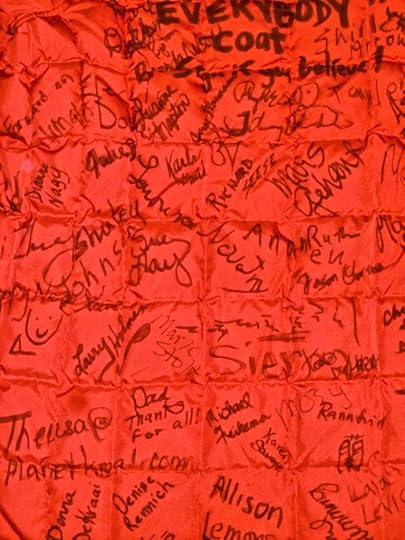

This bright red coat warms me in winter not only because of what it’s made from but also because of what it’s covered with: hundreds of signatures, all scribbled in black or silver ink. Last time I counted, people had signed my coat in at least eight languages besides English, from Arabic to Hindi to Dakota to Chinese. Most of the signers have been complete strangers to me. What they’ve had in common is a hunger to belong. A desire for community.

All this coat-signing began nine years ago. That August, in anticipation of winter, I told my husband I was ready to shell out the money for a serious coat. Having moved to South Dakota nearly a dozen years before, I’d grown weary of being bone-cold during the winter months.

I soon found the perfect coat online, in cardinal red. (Color, too, can help keep you warm in winter.) The coat arrived at my door only two days later. I stuffed it into my closet with a satisfied smile and promptly forgot about it.

Then, in October, I stumbled onto “Everybody,” a poem by Marie Sheppard Williams. The narrator of the poem tells how she was standing at a bus stop one day, when a seemingly poor (perhaps even homeless) man asked her to sign his “dirty canvas coat.” The coat was covered in signatures. He held out his pen to her, saying, “I’m trying to get everybody.” The poem concludes:

I signed. On a

little space on a pocket.

Sometimes I remember:

I am one of everybody.

That year, at our first snow of the season, I knew what I had to do. I took out my new coat and laid it across the family table. With a huge black marker, I printed these words on its back in bold letters: “The `I AM PART OF EVERYBODY’ coat. Sign if you believe!”

I was grinning now. (Better watch out for poetry. It can make you do crazy things. It can be downright dangerous.)

After my giggling nine-year-old son, the first person to autograph my coat was a woman friend. She was half-laughing, half-chiding, as she inscribed her name. “What would your mother say,” she asked, “if she knew you were ruining a brand-new coat!”

As I told my friend then, and many others since, my coat only becomes more valuable, not less, with each signature added. People have autographed my coat in check-out lines, on street corners, in airports, in restaurants, in classrooms and auditoriums. An introvert by nature, I rarely invite them to sign. I wait for them to ask. When they do, I smile and pull a marker from my deep red pocket.

Once, on a flight to Washington, DC, I was sitting beside a little girl from China. When she signed my coat, she expressed concern through an interpreter that someday it might be too crowded for any more signatures. Laughing, I flipped the coat over to reveal its lining, as yet untouched. Her eyes grew wide and bright. “Don’t worry!” I said, through the interpreter, “we can fit the entire world on this coat!” I truly believe that. We can make enough room for everybody.

Every winter, wearing this coat, I have felt like I’m carrying the world on my back, in a good way. I’ve hoped that everybody who signs will feel, at least for one happy moment, that they belong. That their life is bigger than themselves. That nobody has to be all alone, out in the cold.

This winter will be different, though. Isolating at home, socially distancing when I venture out, I doubt that any new signatures will bless my coat.

Unless you want to help me….

You see, the red lining of my coat remains mostly pristine, as if waiting for just this moment. I’m devoting that part of my coat to you and everybody else who believes in the power of community. Especially now, we need more than ever to understand that what is good for us is bound up with what is good for others.

If you’d like me to inscribe your name on my coat’s lining, send me an email. Tell me how you want your name to appear. After I’ve added it to the coat, I’ll email you a photo, to remind you that you are, indeed, part of everybody, and that I’m happy to carry you on my back.

October 19, 2020

“The Clarinet in the Attic”

Pat and Peter went together to the doctor’s appointment. In their eighties, they’d been married over sixty years. Pat was a poet; Peter, a retired minister.

The specialist confirmed an earlier diagnosis: Peter was suffering from dementia, cause unknown. Some “accident in the brain” was robbing him of his short-term memory. Every ten or fifteen minutes, his mind would reboot, and he lost all recollection of what he’d experienced in that short span of time—what he’d done, what he’d said, what he’d heard, where he’d gone, whom he’d met. His long-term memory remained intact, along with his sweet and gracious personality, his intelligence and dry wit, his devotion to peace and justice-making, his love of Pat and their family. But he was living now in a radical present, with no continuity of awareness from one quarter-hour to the next. He could no longer meaningfully build upon the past or anticipate the future.

The moment he arrived home from the doctor’s office, Peter climbed up into the attic and rummaged around for his old clarinet. Born into a musical family, he’d been a skilled clarinetist in his youth, but he hadn’t played in the many decades since.

Instrument case in hand, he closed the door behind him in the little room he used as a study. He set up a music stand, sat down in his chair, and assembled the clarinet. It would need refurbishing, but for now, it would do.

He leaned into his music. Playing again was remarkably easy, as if the instrument were a friend he’d met for coffee every day of his life. He practiced that afternoon for hours, without realizing. In his world, clocks no longer mattered. For the first time in months, he had something purposeful to work on.

Elsewhere in the house, Pat marveled, having never heard him play. She relaxed, listening to his music, happy not only for him, but for herself. So long as he was playing, she knew exactly where he was and what he was up to. She didn’t have to worry. She could even write poems.

Over the next couple of years. Peter’s dementia deepened, even as his skill on the clarinet increased, assisted by a private teacher who came to the house. Peter couldn’t remember the man from one lesson to the next, but he sensed a familiarity with him and enjoyed his company. Pat continued to publish poetry, all the while caring for Peter and struggling with chronic complications from a broken hip.

Pat’s health steadily declined until she and Peter finally had to move into an elder care facility. Peter’s clarinet made the move with them, but it lay untouched in its case. Perhaps he gave up the instrument because of his dementia. Perhaps he was too shy to play where strangers would hear him. Perhaps he was so stimulated by his strange environment that he couldn’t concentrate on his music. Nobody could say for sure.

Refusing to separate from Peter, Pat insisted on living with him in the dementia care unit. Over the course of months, micro-strokes robbed her of her ability to write poetry, to read, to reason—to do most everything that made her who she magnificently was.

In Pat’s last days, the medical staff had to isolate her in a private room to save her from Peter. He was always unplugging her medical equipment or switching off the power. The staff said he didn’t know any better. I have to wonder.

When Pat finally passed from this life, Peter wasn’t with her. On the advice of the staff, the family spared him the knowledge of her death, which he’d never be able to remember. He didn’t participate in the celebration of her life. He didn’t attend her burial. He never asked where she was. He didn’t seem to notice she was gone.

Yet the very day after his beloved wife was laid to rest, Peter took out his clarinet and began to play for the first time since he and Pat had left their yellow frame house on McClellan Street.

Today Peter has a new roommate, a naturalized citizen who speaks no English. They get along just fine. Peter’s music serves as a bridge between them. And Peter plays clarinet not only for his roommate, but for every resident in his unit—”all of [them] passengers,” Peter believes, quite literally, “on the same train.” They adore his playing, and this humble man who had always closeted himself in his study to practice doesn’t hesitate to perform for them.

When Peter first dug out his dusty clarinet from the attic, he needed consolation after a terrible diagnosis. He brought it out again after losing the woman he loved.

This is a love story: between Pat and Peter, between Peter and his clarinet. It nudges us to reach inward, to tap into our creative self, when we’re rocked by bad news or going through a tough patch. Doing so helps to restore balance in our wounded spirits. It might also help people all around us who likewise are feeling unsteady.

Do you have a clarinet waiting in the attic of your life? I suspect you do. I invite you to take it down. Be brave enough to play, for consolation, if only behind a closed door.

October 14, 2020

“Covering Our Part of the Garden”

I shiver in my sweatshirt, the sun already setting. Grabbing one end of an enormous blue tarp, I help my friends Jim and Ruby spread it like a blanket over our giant pepper patch. How much longer can we protect the garden from these killing frosts?

Last spring, my family teamed up with Jim and Ruby to create a “pandemic victory garden.” Our friends maintain the biggest garden I’ve ever seen: 70 x 100 feet—around a sixth of a football field. The plot is always more work than the two of them can handle on their own. This year, the five of us tended it together (socially distanced, of course). Ruby says that they’ve never enjoyed such abundant crops. Not even close.

If you’re a gardener, you know the intense labor it involves, with no guarantee of success. That’s especially true here in South Dakota. Our growing season is very short. Hard frosts—even blizzards—can hit late in the spring and early in the fall. Summers, meanwhile, can be exceedingly hot and dry. Or hot and exceedingly wet. June through August, we can count on only two things: the garden will be buggier than free computer software and as windy as a politician on steroids.

But hey, what’s a few bugs and a little wind among friends?

We’re losing daylight faster than we expected. Ruby and Jim just picked the last of the tomatoes and squash. Some Hubbard squash weigh upwards of 30 pounds. They look like shelled creatures brought up from the bottom of the sea.

In another part of the garden, I sped with buckets through the pepper plants bent beneath bunches of fruit. I harvested sweet bell peppers of every color, from yellow to chocolate-brown; jalapeño peppers, some of them as red and glossy as lipsticks; slender serrano peppers, longer than fingers. The two habanero plants were so thick with orange peppers, Jim told me that he’d yank them up by the roots and hang them upside-down to dry.

It’s going to be a spicy winter. Yum.

One piece of advice from someone who should know better: Always wear gloves when harvesting hot peppers. (I forgot. Again.) And never touch your eyes. (Yep, I forgot. Again.)

By this time of year, we’re well past the bugs and the weed-pulling. Now it’s all about keeping things alive until they don’t need us anymore. With five of us caring for the garden, these past months, we’ve never gotten tired. Well, maybe that’s not quite true, considering our aching muscles and blisters. Let’s say, rather, we’ve not gotten as tired as we would have without one another’s help.

These days I’m seeing a lot of tired people. “Pandemic fatigue” or “coronavirus burnout,” the experts are calling it. A recent survey of citizens in 24 nations suggests that while we’re all using facemasks more than we used to, we’re also venturing out more without social distancing, and we’re handwashing less.

I get it. I’m tired, too. Tired of worrying about my aged parents, unable to see them except on a screen. Tired of worrying about my husband, teaching on a university campus rife with infected students. Tired of worrying about my son, trying to stay healthy in high school and at his job while applying for admission to colleges he can’t visit in person.

I’m tired of not having guests for dinner. Tired of not recognizing friends on the street behind their masks. Tired of not hugging or even shaking hands. Tired of not hanging out in coffee shops and bookstores and museums and concert halls and, well, anywhere indoors, just for fun. Tired of imagining new ways to celebrate, to mourn, to protest, to build community. Tired of learning new means of earning income when I can no longer travel to book festivals, readings, and other gigs.

Like I said, tired. We’re all tired, the essential workers perhaps most of all. Our society is treating many of them as if they’re disposable. The pandemic has utterly changed our worlds. Change is always difficult, even under the best of circumstances, but these months have been an unbelievable slog straight up the mountain. Everyone’s climbing at once, blazing a trail as we go, through rough, unforgiving terrain. Sometimes it’s downright hard to breathe, and the summit isn’t even in sight yet.

I lay a rock on my corner of the blue tarp to weight it down against the wind. Ruby, a brick. Jim, a chunk of wood.

One secret of gardening: you can’t rush what can’t be rushed. We need to respect our place in the scheme of things, as uncomfortable as that may be.

So cover your part of the garden. Dig up the potatoes, but wait on the carrots—Jim says they’ll get sweeter with the freeze. Sing and laugh as the chill falls on your shoulders. Say a blessing in frosty plumes. Yack it up with somebody you love, the next row over. Let the rich dirt stain your hands. Sit down when weary and take a breather. Someday this tough season will be past.

October 6, 2020

“Follow the Nudge”

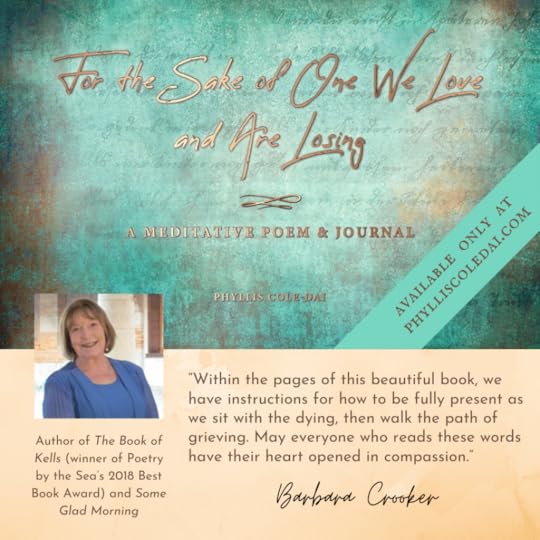

Early this past February (doesn’t that seem like a lifetime ago?), I was on a personal writing retreat in San Diego. One night, I dreamed that my aunt had invited multitudes of family members to a reunion at her house. Once there, we realized that she was dying. She’d summoned us to say goodbye. She asked us to gather around her bed (in dreams, multitudes can easily do that). She handed us a very old book with a turquoise cover. Its text was handwritten in ink on parchment. The title was For the Sake of One We Love and Are Losing. As my relatives and I read the book aloud (in dreams, multitudes can easily do that together), we discovered that it was a long, meditative poem. The words of the poem evoked in us a profound sense of love and kinship. The intensity of that shared feeling woke me up.

“Write down the words,” a voice said to me, not in a voice I could hear, but a voice nevertheless. (I’ll call this voice the Muse.)

“It’s too cold to get out of bed,” I said.

“Write them down.”

“I want to go back to sleep. I’ll write them down in the morning.”

“You’ll never remember. Write them down now.”

I gave up arguing and reached for a journal and a pen. I wrote as fast as I could, in whatever order the lines of the poem came, until I couldn’t remember any more. Then I dropped back to sleep, as if somebody had pulled my plug.

Once I returned home from my retreat, I shaped the poem—arranging the lines, adding words or phrases to fill gaps in the flow, deleting what made no sense. I sent my draft to several poet friends for feedback. Their overwhelming response was, “You must find a way to share this.”

I have no idea why the Muse brought this poem to me. But a month later, COVID-19 hit the U.S. hard. I don’t think that’s mere coincidence. Especially now, with the pandemic often preventing us from being with those we love as they’re dying, or from gathering as we’d like to mourn their loss, this poem can help us help us grieve.

Creative inspiration—what I’m calling the Muse—often comes as a surprise visitor, as if from beyond ourselves. Here are a few suggestions for what to do when the Muse visits you.

Welcome the Muse as a dear friend and esteemed guest, even if inconvenient. Would you ever leave such a friend standing on your stoop in the middle of the night because you didn’t want to be bothered? Of course not. Hearing their voice, you’d run to the door.Trust that the Muse is bringing you something important. She won’t knock on your door at three in the morning to remind you to do the dishes. She wants to deliver something of value—maybe so valuable, you feel unworthy or incapable of it. Suspend self-doubt. The Muse only brings what you’re ready for.Immediately honor the Muse’s gift. Jot down the inspiration in your journal. Talk it into your phone. Confide it to a trusted friend. Just don’t push it away, making excuses like I did in San Diego, saying, “I’ll do it later.” The Muse of Procrastination is no muse at all, but a trickster.

Work with whatever the Muse has brought you. Sometimes the Muse brings only threads of an idea when you want an elaborate tapestry. Be prepared to collaborate with her, bringing all your skills to the work. Whatever the Muse brings will be enough to get you started.

Spare the Muse any cravings you might have for personal gain. The Muse doesn’t come to you out of her own need. She doesn’t come to you to meet your needs, either. She comes to meet the needs of a wounded, if wondrous, world.

Keep asking the Muse for help. Don’t sit around waiting for the Muse to drop by again. Like any relationship, this one takes work. The more you seek out the Muse’s help, the more you’ll find it.

Allow the Muse to change you. Every creative project that I’ve ever undertaken has changed me; by the time I finish, I’m more myself than when I began. Follow the Muse’s inspiration, and the same will be true for you.

Be alert for the Muse’s nudge. It will come. Be swift to acknowledge it. Be grateful enough to trust it and brave enough to follow it. Say to your friend the Muse, with humility, “Teach me. Show me the way.”

October 5, 2020

“Laughing in the Dark”

Last week I joined my friend and fellow writer Ruby Wilson on a personal retreat in a local state park. Camping in adjoining sites, we socially distanced across a shared fire. We worked on our separate writing projects. We read books. We discussed current events and family matters. We told stories of the supernatural, and bad jokes. We mourned the loss of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. We sat in stunned silence, hearing that the husband of a mutual friend had died in an accident. Sometimes even retreating to the woods can’t protect you from the harsh realities of life.

Our second night in camp, we got a little crazy. We decided to hike the Tetonkaha Trail in the dark. Without flashlights. Without even a sliver of moon to see by.

In daylight the Tetonkaha Trail is a peaceful stroll, especially in cooler weather, when the lake empties of boats and jet skis. You don’t meet many other hikers. Only three-quarters of a mile long, the rolling path loops around a peninsula jutting out into a shallow lake. Most of the way, you’re sheltered by warty hackberry trees, gigantic oaks and cottonwoods, box elders and ashes and ponderosa pines, clusters of willows. Songbirds accompany you, lest you intrude on their banquet of berries. Nearing the point, you break out of the woods into a spacious meadow of waist-high prairie grasses. From there you can see herons striding the shorelines and crowds of migrating white pelicans riding the water, along with noisy gulls and ducks.

Like I said, a peaceful stroll in daylight. After sundown? Ruby and I could only guess. We zipped on our coats, grabbed our trekking poles, and abandoned the comfort of our slow campfire. We set off on a short walk to the trailhead, amazed at the stars, still brilliant despite the smoke blowing through from western wildfires.

Ruby had hiked the Tetonkaha Trail only once before, but being a brave, hearty soul, she volunteered to lead. I shadowed her up the gentle hill from the trailhead into the woods, where the world contracted to shades of black, with flecks and patches of deep gray. There her silhouette melted away. I could only follow the sound of her voice and the popping of acorns beneath her feet.

My eyes believed that they could conquer the night by sheer determination. They tried squinting. They tried opening wide. They tried peering over the rims of my bifocals. Nothing helped them adjust. I might as well have been staring into the unrelenting dark of a cave. I couldn’t see any light at the end of the tunnel of trees. Just blacker black.

Autumn leaves dripped down on my head and shoulders, startling me. I relied on my poles for balance. “Go up,” they told my feet. “Go down.” They warned of protruding roots and rocks. They let me know when I was straying into underbrush. When I swept against weeds on the edge of the trail, I eased back toward the imagined center, pushing aside my worries about poison ivy and stinging nettles.

In the interval of the meadow, I could vaguely discern Ruby, six or seven feet ahead. Anchored by the sight of something I recognized, my body relaxed into the sighing of grasses, the chirping of crickets, the beating of waves against the beach. When we reentered the trees, I laughed.

Truth be told, I’ve rarely laughed so much as I did that night, wending around that loop trail. It was the same for Ruby. At first, our laughter might have been thanks to nerves—though what’s the worst that could have happened? We couldn’t have fallen off a cliff or been gobbled up by a bear. We couldn’t even have gotten lost, not on a loop trail with flashlights in our pockets (just in case).

Most of our laughter, though, arose from pure wonderment—at how magical the world appeared in its varied shades of black; at how, without light, our eyes surrendered to the guidance of other senses; at how phenomenally those senses teamed up to navigate a safe way through; at how profound ignorance of what was coming next forced us to pay close attention to every step we took. We scarcely stumbled, and we made good time. We hiked around the peninsula at almost the same pace as we did in broad daylight.

“I’d never have done this on my own,” Ruby and I said to each other, more than once.

We were so enthralled by that hike, we did it again the very next night. This time, I led, and Ruby followed. Reversing roles changed our experiences of the trail. And still we laughed.

In the woods of these strange and troubled times, let’s just keep putting one foot in front of the other, trusting the wisdom of all our senses and rejoicing in one another’s company. If we do, we won’t need to whistle in the dark, trying to sound braver than we feel. We’ll be laughing for dear life down the path.

September 22, 2020

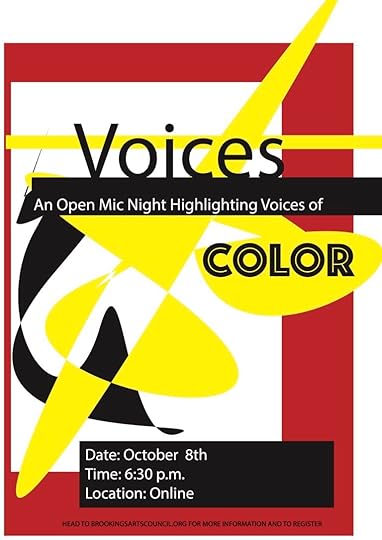

Virtual Event to Feature Voices of Color

Phyllis invites you to participate in “Voices,” a virtual open mic highlighting voices of color. Sponsored by the Brookings Arts Council and the South Dakota Humanities Council, “Voices” will be held on October 8th at 6:30PM.

This event will be hosted through Zoom and anyone may attend. However, readers at the event must reside in Brookings County and/or be a current student at South Dakota State University.

Registration is available online at brookingsartscouncil.org. Non-electronic registration will be available at the Brookings Arts Council outdoor art distribution center starting this Saturday.

The deadline for registering to read at the event is midnight on Sunday, October 4th. Registration for the event for non-readers will be open till October 8th. Kas Williams, Chief Diversity Officer for South Dakota State University, will be the emcee.

For more information or questions please contact the Brookings Arts Council at 605-692-4177 or directorbac@swiftel.net. The BAC is located at 524 4th.

Working with Phyllis on the planning team are Kas Williams, Nieema Thasing, Ashley Ragsdale, and Ruth Harper.

September 16, 2020

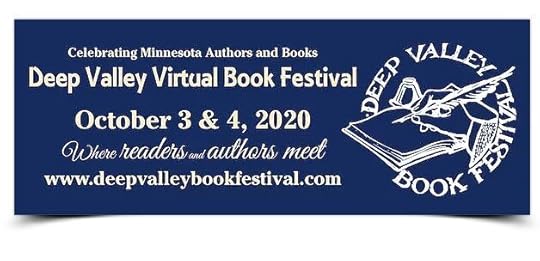

Join Phyllis at the Deep Valley Book Festival

One of the silver linings to this awful pandemic is that Phyllis can participate as an author in two book festivals at once: the Deep Valley Book Festival in Mankato, Minnesota, as well as the South Dakota Festival of Books. Both will be held online during the first weekend of October. The DVPF is traditionally the largest event of its kind in southern Minnesota. All events this year are free through Zoom. Their links will be posted on the festival website.

In addition to being an online exhibitor at the DVBF, Phyllis will participate in three panels:

11AM, Saturday, October 3: “Writing the Truth” (pre-recorded). Registration link will be posted on the DVPF website the day of the event.2PM, Saturday, October 3: “Live Q&A with Festival Authors.” Registration link here.2PM, Sunday, October 4: “The Road to Publishing” (pre-recorded). Registration link will be posted on the DVPF website the day of the event.September 15, 2020

Phyllis Slated to Appear at South Dakota Online Festival of Books

Phyllis is happy to announce that she has been invited to give two presentations for the upcoming South Dakota Online Festival of Books. She will also be an online exhibitor.

Her first presentation, “What to Do When the Muse Wakes You Up”, will be a Zoom event at 4pm on Friday, October 2. “How does the Muse communicate with you?” Phyllis will ask. “Does she nudge your shoulder? Tug your sleeve? Startle you awake in the middle of the night?” Phyllis will reflect on the magic of inspiration while sharing the story behind her latest book, a slender special edition called For the Sake of One We Love and Are Losing (Bell Sound Books, 2020). She’ll also present a reading of this meditative poem, which is dedicated to all who grieve.

Her second presentation, “Creating Gatherings in a Time of Pandemic,” will be a Zoom event later in the Festival month, at 3pm on Tuesday, October 20. “Imagine,” Phyllis says, “a small birchwood box with a poem hidden inside, handwritten by the poet. Imagine that box, painted by an artist, traveling through the varied lives of multiple recipients. Each person celebrates its contents, then offers his or her own imaginative contribution, before passing it to someone new. Imagine 54 such boxes, full after several months, being exhibited, sold, and the proceeds donated to the relief of creatives impacted by the pandemic. This project is Gatherings, an arts-based “experiment in giving and receiving” that concluded in August.

Phyllis co-managed the poetry dimension of Gatherings. She’ll share poetry selections and box art from the project while reflecting on the significance of the written word in a time of pandemic.

These and all SDFOB events will be broadcast on the South Dakota Humanities Council Facebook page. Please watch this page at the Council website for more information.

September 10, 2020

September 7, 2020

“Laughing at the Silver Linings”

Amid storms of suffering and hardship, we often see soft flashes of light: things that make us happy, give us hope, fill us with appreciation. Sometimes we’re reluctant to celebrate these glimmerings, lest we seem indifferent to the distress and anguish all around us. Still, our hearts are big enough to hold many emotions at once, aren’t they? In fact, that’s normal. So let’s not be afraid to express our gratitude for the proverbial silver linings in our dark clouds, or even to joke about them. Gratefulness and humor can help us meet and overcome adversity.

In that spirit, I’ve set down this rather light-hearted list of 45 silver linings I’ve found in the clouds of my pandemic isolation. (Forty-five was an arbitrary cut-off point. Otherwise, I’d still be writing.)

1. Since I scarcely go anywhere, I don’t have to worry anymore about misplacing my car keys or my wallet.

2. I’ve picked up the clarinet again after not playing since high school. (I’m not sure that my family regards this as a blessing.)

3. I’m growing more houseplants and haven’t killed them all yet. (Only a couple.)

4. Our home is now more like a sanctuary than a pit stop between activities.

5. I’m basking in the immensity of my relative solitude. (Yes, I’m an introvert by nature.)

6. Shopping almost exclusively online has freed me from the chore of store-shopping.

7. I regularly splurge on comfort foods that I rarely used to eat. (Hmm … is that a good thing? Maybe that should be on a different list.)

8. Our family cats are reveling in our constant company and more frequent treats.

9. My brief calls from telemarketers now end with a genuine exchange of good wishes for each other’s health.

10. I no longer take the U.S. Postal Service for granted. (Or my hair stylist. Or my trash collector. Or my doctor.)

11. I can now tell the difference between vegetables and weeds in the garden.

12. I’m discovering which friends and neighbors love fresh tomatoes and squash and those who can’t eat cucumbers or spicy peppers.

13. Our house is cleaner because we’re disinfecting more often.

14. When I must leave the house, I can show my respect for others simply by wearing a mask.

15. Behind my mask, I’m learning to smile with my eyes and through my voice.

16. My husband and I are figuring out that there are some movies we do like to watch together.

17. I can now Zoom in something other than a car.

18. I have virtual front row seats to all kinds of musical performances and literary events that I wouldn’t get to attend otherwise. (I can also duck out early without feeling like a louse.)

19. I’m getting acquainted with my white fragility and challenging myself to more actively build racial justice.

20. I’m saving a ton of money on make-up, seldom wearing it anymore.

21. I now remember why, two decades ago, I switched from long hair to short.

22. My professional wardrobe now consists of pajamas, old T-shirts, shorts or sweatpants, and walking shoes.

23. I conduct all of my business from the comfort of a couch.

24. I’m not living out of suitcases and hotel rooms, though this is my prime season for speaking engagements and book festivals.

25. Commuting to public appearances now involves walking to my couch and logging onto my computer.

26. My troublesome shoulders don’t ache from lugging boxes of books to my public appearances. (That’s fortunate, since I’m not risking a pandemic massage.)

27. My feet and back aren’t sore from standing for hours at author events. (Ditto the massage.)

28. Without my usual business trips, I’m spending less money on gasoline and reducing my carbon footprint.

29. I can now eat garlic right before a (virtual) author talk without worrying about my breath.

30. I’ve virtually toured amazing museums in faraway places that I’ll never visit in person.

31. I’m investing far less time in social media and am lighter for it.

32. After lying dormant for 40 or more years, my love for writing poetry (not just reading it) has reawakened with a jolt.

33. Kind messages in chalk now decorate many of our neighborhood’s sidewalks.

34. My son has been whipping up his specialties in the kitchen, including cheesecake, vindaloo, and guacamole. (No, not all for the same meal).

35. I’m deepening my already close relationship with my mother, quarantined in an assisted-living facility half a continent away. We now talk by phone or video chat at least once a day.

36. I’ve progressed to Level Three in my Spanish lessons on Duolingo.

37. I now have another excuse—COVID brain fog—for always forgetting things. (How can I remember Spanish?)

38. I have endless opportunities to channel my anxieties into creativity.

39. I’m finding uncommon ways to support people who are grieving, since I can’t be with them physically.

40. Because more people are reading books, I’m selling more books and can contribute more to my son’s college fund.

41. I’m having more wonderful correspondence than ever with readers of my work.

42. I bought a hula-hoop and can now keep it endlessly spinning. (Next, mastering the art of walking while hooping.)

43. Our busy street has less traffic, less noise, and seemingly less pollution.

44. I’ve made focaccia and other breads for the first time (and loved it).

45. I’ve gotten a glimpse of what my dear husband might be like in retirement. (Just kidding, sweetie.)

Maybe this playful list of my silver linings will inspire you to brainstorm your own. Care to share?

(Photo by Saruna Burdulis, used under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license.)