Stan Garfield's Blog, page 20

October 14, 2022

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 24 — Rachel Happe

Rachel Happe (pronounced “hoppy”) is a digital workplace strategist based in Boston. She helps organizations implement emerging technologies to advance their business strategies using the power of community to spark joy in the workplace.

During her career, Rachel has served in analyst, product management, product marketing. and executive roles. She specializes in strategy, leadership, the future of work, the digital workplace, and community management.

Rachel founded Engaged Organizations and The Community Roundtable to support organizations in using community governance models to pursue agility and innovation. Her current work focuses on fostering workplace engagement and transforming how people work by building community-centric cultures. She published a decade’s worth of groundbreaking research in the annual State of Community Management report, including new perspectives on how to measure the engagement, culture, and value of communities.

Profiles LinkedIn Engaged Organizations The Community Roundtable 1 The Community Roundtable 2 Profiles in Knowledge BookBecoming Hybrid: A Team Collaboration Handbook

This handbook is organized into three primary sections. The first is designed to do individually and independently. The second and third are intended to be done as a team but can be completed incrementally.

Table of Contents

Individual ReflectionTeam DiscussionTeam CommitmentsAppendices

Facilitation GuideCollaboration Check-upTeam Discussion RolesPresentationsEnterprise 2.0 Conference

2011 Boston Online Communities — A Strategic Imperative 2011 Santa Clara Are You Getting Ahead Or… Are You The Red Queen? 2012 Boston The Iceberg Effect of Community ManagementKnowledge Management Conferences

KA Connect 2016 Architecting a Collaborative Culture Using TheCR’s Working Out Loud Framework APQC 2019 The Language of Engagement KMWorld 2019 C104: Crafting Culture with Communities & Engagement Other Content Engaged Organizations Blog Medium LinkedIn Articles LinkedIn Posts Twitter The Community Roundtable The Social Organization Blog Posts Muck Rack Articles Information Week Articles CMS Wire Articles SIKM Leaders Community Calculating the ROI of Customer Engagement 60 Strategy & Leadership Books Written by Women Social Media is Not Community Do Enterprises Have the Patience to Develop Communities? Leadership of Belonging

Manage the Environment, Not the People

Successful community managers can inspire and organize immense value creation from thousands or tens of thousands of individuals with very few full-time staff. How? They manage the environment, not people or tasks. Community managers ensure that the leadership, infrastructure, resources, metrics, and routines are all set up to make the work of the community easy, satisfying, joyful, and rewarding. They make sure each individual contributor receives more than they contribute by engaging in the work of the community. They must ensure that the culture of the community welcomes, accepts, and supports people. Community leaders do all of this without telling people what to work on or how.

Using a community operating model creates cultures in which people want to participate. Engagement grows because individuals get something more valuable than what they put in. People commit to each other because they form authentic relationships. People collaborate to build incredible things because it challenges and excites them. Perhaps most compelling is the impact of community operating models on business models. Community models generate unbelievable ROI because community-centric governance is much lighter than what currently exists in organizations — all for the ‘cost’ of giving up control.

Organizations that want employees to feel seen, accepted, and validated — to create a sense of belonging — would do well to learn more about community management because it is the key to transforming organizations.

Managing organizations like communities are what will inspire people to do their best work people by ensuring they receive attention, care, support, curiosity, inspiration, and excitement through authentic relationships with others. Optimizing organizations for this connection requires dismantling the heavy, layered governance that currently controls people and replacing it with governance that frees people to work collaboratively with more control, influence, and choice in how they work.

Leadership, Communities, and the Future of Work

Control over people no longer works in an age where we can connect with anyone, find information easily, and work remotely. Talented individuals will join organizations where they can satisfy both their extrinsic need for money and their intrinsic need for meaning and challenge.

Organizations that do not adapt to this new reality will lose traction because people do not want to be controlled. Control is also expensive, requiring layers of management, policies, infrastructure, and accounting mechanisms that shear investment resources away from value creation.

Communities are showing us what the future of work can look like — and it is compelling. To see what enterprise community teams are achieving, see Engaged Organization’s Digital Workplace Communities report.

[image error]October 7, 2022

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 23 — Annie Green

Annie Green is a knowledge strategist and architect who has led several KM initiatives. She helps individuals and organizations think and learn.

Her roles have included Associate Professorial Lecturer at The George Washington University, Knowledge Valuation Portfolio Editor for VINE Journal, a member of the International Institute on Knowledge and Innovation (IIKI), and an International Expert Reviewer for the Knowledge and Innovation Southeast Asia (IKI-SEA) Bangkok University Most Innovative Knowledge Enterprise (MIKE) Award.

Annie is an author, speaker, lecturer, journal reviewer, and a member of several brain trust/think tanks. She was the co-founder of the Knowledge Management Education Forum (KMEF), served as Chair of the Association for Intelligent Information Management KM Competencies team, and served as the chair of the International Conference on Intellectual Capital and Knowledge Management (ICICKM) 2013. She is the creator of the Framework of Intangible Valuation Areas (FIVA), a model that identifies intangible assets within the business structure

Annie created the Business Reasoning, Analytics, Intelligence Network (BRAIN), a model that identifies the components to establish artificial intelligence in the business enterprise structure. She has a Doctor of Science (D.Sc.) from George Washington University and a Masters in Information Systems (M.S.I.S) from George Mason University.

Her KM focus is on building an architecture that leverages data, intelligence, and knowledge to build a thinking organization. She has built a career on the effective and efficient operations of organizations. She prides herself on being an evangelist for individual and organizational thinking that leverages data, intelligence, and knowledge.

Profiles LinkedIn Twitter Profiles in Knowledge BooksA Framework of Intangible Valuation Areas: The Sources of Intangible Assets within an Organization

In Search of Knowledge Management: Pursuing Primary Principles edited with Michael Stankosky and Linda Vandergriff

Chapter 8: The Organizational Body Gets an Intelligent BrainChapter 19: Driving Change Using Knowledge Management — Lessons Learned from an Unidentified Organization

Making it Real: Sustaining Knowledge Management

Chapter 10: The Cognizant Organization Other Content

LinkedIn Articles

LinkedIn Posts

ResearchGate

Emerald

Georgetown University

Interviews

Because You Need to Know — Pioneer Knowledge Services

with Edwin K. Morris

Convergence Conversation: Unpacking Knowledge Management

with Deborah WestphalKMWorld Conference2010

Planting Seeds to Harvest Knowledge

—

Slides

2020

A401 — AI Landscape in KM

with Tony Rhem

Article: A framework of intangible valuation areas (FIVA): Aligning business strategy and intangible assets

with Julie J. C. H. Ryan

Other Content

LinkedIn Articles

LinkedIn Posts

ResearchGate

Emerald

Georgetown University

Interviews

Because You Need to Know — Pioneer Knowledge Services

with Edwin K. Morris

Convergence Conversation: Unpacking Knowledge Management

with Deborah WestphalKMWorld Conference2010

Planting Seeds to Harvest Knowledge

—

Slides

2020

A401 — AI Landscape in KM

with Tony Rhem

Article: A framework of intangible valuation areas (FIVA): Aligning business strategy and intangible assets

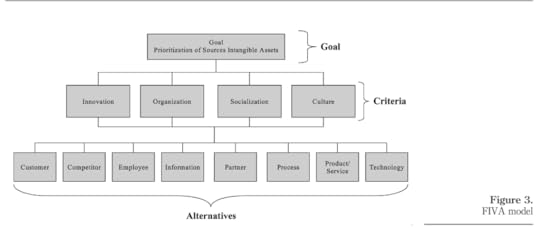

with Julie J. C. H. RyanThe combination of the value drivers of intangibles (alternatives) and the KM objectives (criteria) are modeled as depicted in Figure 3.

The FIVA model provides significant insight into the value components that contribute towards the achievement of a specific KM objective. The design of the FIVA model supports a dynamic mix of value components based on the business environment. FIVA is an initial step toward the development of a network and dynamic model to value and report intangible assets. FIVA leverages existing works to move the discipline of intangibles forward.

Conclusion

The FIVA represents a dynamic relationship between strategic objectives of KM and value drivers of intangible assets. FIVA provides a view of intangible assets within the context of the business enterprise and supports their valuation based on a common set of business dimensions. FIVA provides a concept of something familiar and similar to represent the complex business enterprise. It provides a systematic way to divide a business enterprise into its discrete activities. FIVA is a concept that could be used to examine the groupings of business activities and to establish boundaries that alignment with drivers of value, both tangible and intangible. FIVA incorporates intangible assets in the value chain of a business enterprise, which provides a first step to aligning intangible assets to value creation with its business strategy.

Today’s businesses are unaware if they have people, resources, or business processes in place to execute and succeed in their KM strategy. FIVA is a concept that allows a business to identify and link performance measurements/indicators to its intangible value drivers and subsequently capture measures to monitor and evaluate leading and lagging indicators in the achievement of its KM strategy. Understanding the value of its intangibles helps a business to develop, sustain and enhance its mission effectiveness and/or competitive advantage. FIVA provides a methodology to have command of and access to effective utilization of business resources and knowledge, which supports the business’s capability to implement cost and differentiation advantages.

[image error]October 6, 2022

Fave Five — My New Substack Newsletter about Books, Food, Music, Sports, and Humor

I just launched a new Substack newsletter, “Fave Five.” If you enjoy my posts about reading, dining, music, sports, and visual humor, I invite you to subscribe to receive weekly issues. Each issue has a book best bet, recommended restaurant, marvelous musician, sports star, and picture pun.

Subscribe to the Fave Five newsletter.Visit the Fave Five site.Read the first issue of Fave Five that includes: Book Best Bet: LittleRestaurant Recommendation: Teresita Mexican GrillMarvelous Musician: Ari HestSports Star: Aaron JudgePicture Pun: Canine Commode[image error]

Book Best Bet: LittleRestaurant Recommendation: Teresita Mexican GrillMarvelous Musician: Ari HestSports Star: Aaron JudgePicture Pun: Canine Commode[image error]

September 30, 2022

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 22 — JoAnn Girard

JoAnn Girard and her husband John were co-founders of Sagology, a firm that focused on connecting people with people to collaborate and share knowledge. JoAnn was the managing partner of Sagology.

She has worked on a variety of knowledge intensive research projects, which considered issues such as information anxiety, enterprise dementia, and organizational memories. JoAnn explored social media with a view to determining what organizational leaders need to know in this important domain.

Prior to forming Sagology, JoAnn was co-founder of two successful technology companies. Yacht-club.net developed and hosted web presences for yachting companies in the USA, England, Scotland, Spain, Gibraltar, and Greece. Quid Pro Quo Software developed educational and edutainment software, including their flagship game, Trivia Mania. Before entering the high-tech arena, JoAnn worked in the travel industry and as a school librarian. The experience she gained in these information intensive positions proved especially valuable as she considered the knowledge challenges confronting executives.

I can tell from our connection on Facebook that in addition to writing about knowledge management, JoAnn and I share a love of music, food, and humor.

Profiles LinkedIn Facebook Twitter Profiles in Knowledge BooksKnowledge Management Matters: Words of Wisdom from Leading Practitioners edited with John Girard

A Leader’s Guide to Knowledge Management: Drawing on the Past to Enhance Future Performance with John Girard

Social Knowledge: Using Social Media to Know What You Know edited with John Girard — Download

Business Goes Virtual: Realizing the Value of Collaboration, Social and Virtual Strategies with John Girard and Cindy Gordon

Other Content

Other ContentDefining knowledge management: Toward an applied compendium

We have gathered a collection of more than 100 KM definitions. We have very deliberately provided a broad selection of KM definitions: some are from academics, while others are from practitioners, some are from government, others from the for-profit sector, and still others are from the not-for-profits. We also tried to include definitions from a variety of countries.

A frequency analysis of the 100 definitions determined the most common words appearing in KM definitions were: knowledge, organization, process, information, use, share, create, and manage. Based on this review, we propose the following definition:

Knowledge Management is the process of creating, sharing, using and managing the knowledge and information of an organization.

Knowledge management is the creation, transfer, and exchange of organizational knowledge to achieve a [competitive] advantage. — John Girard & JoAnn Girard, Leading Knowledge 2.0

Knowledge Sharing as an Enabler of Virtual Business

The success of most virtual business is the result of four critical enablers coming together in the right balance: social technology, visionary leadership, collaboration culture, plus virtual worlds. This so-called TLC+V (technology, leadership, collaboration, and the virtual) of virtual business has suddenly combined to create exciting and uncharted business opportunities waiting to be harnessed. Some refer to this new discordant environment as “weapons of mass collaboration.” This new collaborative and more connected world is more adaptive, more agile, more fluid, more virtual, and finally, more collaborative and quite frankly more refreshing, fun, and inspiring.

The future of management… are you ready

There are many examples of how organizations are using the collaborative forces of the Internet to create and exchange knowledge. The question is, what are you doing in your organization to exploit the weapons of mass collaboration. Virtually every day, new web tools are being developed offering new ways to foster collaboration and knowledge sharing. Our aim is not to endorse particular tools, but rather to encourage leaders to think about how these tools will help them achieve a competitive advantage. The future starts now — are you ready?

Simple Ideas That Worked in Complex Environments

One of the real problems with the pyramid concept of data, information, and knowledge is that the boundaries are not clear. What is data to one person may be knowledge to another. At the end of the day, executives crave whatever is needed to make a decision; they do not worry about the nomenclature. Verna Allee, author of several excellent knowledge management books, reminds us that “fuzzy boundaries create innovation.” This phase was the catalyst for a new model to describe the relationship between data management, information management, and knowledge management. Rather than on focus on whether a particular tool, tactic, or technique should be labeled as a data management, information management, or knowledge management, the model suggests that a continuum exists. By eliminating strict boundaries, which are often difficult to define, the model focuses on outputs rather than preconceived categorizations.

[image error]September 23, 2022

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 21 — Susan Feldman

The late Sue Feldman (1947–2020) was known for her expertise in search, text analytics, and cognitive computing.

Sue was founder and CEO of Synthexis, a consulting firm that provides business advisory services to vendors and buyers of cognitive computing, search and text analytics technologies. Since 1990, she was instrumental in shaping market research and understanding in search and text analytics. She spoke frequently at industry events on topics such as trends in computing, conversational systems, big data technologies, and the hidden costs of information work. In 2014, she led a coalition of industry experts to define cognitive computing. She wrote the chapter on search engines for the Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science and was the first editor of the IEEE Computer Society’s Digital Library News. Sue’s clients relied on her for strategic advice and business coaching, as well as for her wide network of contacts in the industry. In her book, The Answer Machine, Sue discussed the technologies behind information seeking and analysis, and their central role in the future of computing.

Before founding Synthexis, Sue was Vice President for Search and Discovery Technologies at IDC (International Data Corporation), where she directed research on the technologies and markets for search, text analytics, categorization, translation, mobile and rich media search. Prior to coming to IDC, Sue was founder and president of Datasearch, an independent technology advisory firm, where she consulted on usability and on information retrieval technologies. She was a founder and former president of the Association of Independent Information Professionals, a member of the Association for Computing Machinery, and won numerous research and writing awards.

Sue held degrees from Cornell University in linguistics and from the University of Michigan in information science.

Profiles LinkedIn Synthexis Profiles in Knowledge Book

Table of Contents

IntroductionThe Query Process and Barriers to Finding Information OnlineOnline Search: An EvolutionSearch and Discovery Technologies: An OverviewInformation Access: A Spectrum of Needs and UsesFuture Tense: The Next Era in Information Access and DiscoveryAnswer MachinesBibliography

ConferencesCognitive Computing & AI Summit 2019

W4: Cognitive Computing 101 Panel: Ethical Considerations of AI TechnologiesText Analytics World

Text Analytics World 2012 — Keynote: Unified Access to Enterprise Information Text Analytics World 2013 — Five Trends That Will Reshape the Computing LandscapeTaxonomy Boot Camp

Taxonomy Boot Camp 2006 — The Categorization Quandary: Making Choices Taxonomy Boot Camp 2005 — Welcome & Keynote: Why Categorize?Enterprise Search & Discovery 2019 — What’s Ahead for Search? Enterprise Search & Discovery 2018 Evolution of Search & Discovery: A Panel Discussion Issues Surrounding Security, Privacy, and Ethics in Enterprise Search Enterprise Search & Discovery 2015 Keynote — Sparking Innovation: Human & Machine Learning & Knowledge SharingDynamic Developments Debate Enterprise Search Summit 2012 — Opening session: Trends in Enterprise Search: A Question and Answer Session Enterprise Search Summit East 2008 — Keynote Panel: Take a 30,000-Foot View of Enterprise Search Implementation Enterprise Search Summit West 2008 — Keynote — The Future of Search Enterprise Search Summit West 2007 — Welcome & Opening Keynote — Search in 2008: An Outlook for More Growth, Confusion & ChaosKMWorld 2015 W15: Inspiration, Insights, & Innovation Through Cognitive Computing Keynote: Sparking Innovation: Cognitive Computing & KM — Transcript — Slides — Blog post — Video KMWorld 2014 — C301: Cognitive Computing & KM Other Content Synthexis Publications Cognitive Computing Blog Pervasive Search White Paper KMWorld Cognitive Computing Consortium Considering Bias & Cognitive Systems Information Today Cognitive Computing and Search with Hadley Reynolds, interviewed by Jeff Fried Is There a Future for Information Professionals? — November/December 1996The imminent demise of the information professional has been a hot topic of discussion for years. It is something of a mystery to me why we are so convinced that we can be replaced, or so inclined to perceive new advances as threats. If we are so good at what we do, and others can’t seem to get the hang of it, why would the World Wide Web or an improved set of interfaces wipe us out? The answer, I think, is that we really don’t know what it is that we do. Sure, we “find information,” but what exactly does that entail? Perhaps if we assess our skills more precisely, we will be able to understand why our profession is not in danger of collapse.

Where Are We with Cognitive Computing Today? Part 1 — December 5, 2016Cognitive computing is emerging as a significant part of the next generation of computing. Because it is early days in this new generation of computing, there is still no widespread understanding of what it is and how it differs from some of its relatives: AI, internet of things, machine learning, conversational systems, bots, or NLP. We see in both the US and in Europe that companies are very interested but are mostly still at the experimentation and proof of concept stage. We will be tracking some of these projects as they develop their cognitive applications and roll them out more broadly. There is no question, though, that interest is high, and that the ability to augment and assist users, as well as to move from static to dynamic systems has great appeal.

I recently had the opportunity to attend a focus group, sponsored by SAS Institute, on cognitive computing adoption outside the US. Attendees came from Denmark, Japan, Finland, Serbia, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, India and Ireland. They represented financial services, telecom, consumer product manufacturers, government agencies, and airline companies. Here are some gleanings from their wide-ranging discussion.

How are you using or how do you expect to use cognitive computing?

Automatically revise and evolve rules to expedite adaptationUncover and improve best business practices and processesDetect patterns of behavior. Detect abnormalities. Identify risks.Augment human agents who can’t handle the current workload by automating the more predictable aspects of the job.

Why move to cognitive computing?

Handle large amounts of data with many more variables. Especially textual data.Reduce need for adding manpower. People just don’t scale.Stay ahead of competitorsUncover surprises. (This was a side benefit to a demonstration project that was originally designed to augment the human workforce)Curious to see what benefits might derive from cognitive computing that we can’t get nowGet rid of silosAutomate predictable or repeatable workAugment human work by developing digital assistantsExamples of uses:

Speech-to-speech product sales. One firm’s innovation lab is experimenting with building an App that will be personalized; will use machine learning to replace hundreds of business rules and 20 predictive models; and the machine learning will allow the models to evolve and help to revise rules faster.

One firm is experimenting with discovering and extracting patterns of best business practices to establish KPI’s worldwide from hundreds of business managers’ individual knowledge. Need to understand what practices work and why.Expedite transactional processing. Moving from rules-based processes to teaching a system how to assess issues and minimize delays.Another firm is tracking and analyzing invoices using rules and econometric models. Their goal is to teach a system to automate model development and modification for tracking and analyzing invoices. Extending beyond rules and econometric models they want to add sentiment from incoming, non-English communications.Recognize patterns of behavior to find anomalies and predict risk in order to more thoroughly assess people and goods.Automate responses to customers, but on a more individual level. Part of a project to analyze customer opinions — a big data project.In all cases, augmenting existing applications but seeking net new benefit from the use of cognitive computing systems was a consistent goal amongst all participants. Completely new product development or drastic changes to business processes from cognitive computing applications wasn’t seen to provide the palatable business benefit needed to embrace adoption. In all cases, however, changes and improvements to existing business practices were expected.

Where Are We with Cognitive Computing Today? Part 2 — December 12, 2016I recently had the opportunity to attend a focus group, sponsored by SAS Institute, on cognitive computing adoption outside the US. The group of early adopters attending this focus group was proceeding with caution. They had the bruises from past new technology experiments and don’t believe the hype around AI today. In each case, it was apparent, however, that they had support from high-level management, and that they were starting with a proof of concept, or several. We have heard this from other buyers. Several enterprises are working with more than one vendor, trying to compare dissimilar products with little in the way of best practices to guide them.

Some of the concerns that emerged were, first, that these systems are often a black box; that it was not clear why they were getting the recommendations that were delivered. Because business systems are traditionally data-based and deterministic, rather than stochastic, this ambiguity appears to be unacceptable to them for some uses today. The buyers felt that they needed the evidence behind the results. Probabilistic systems, including search engines, have long struggled with this problem. Although we know that information systems of all sorts deliver only what you ask for and not what you should have asked for, nevertheless they are seen as precise and complete. Managing expectations is a challenge for vendors and for IT managers.

Other groups of attendees were concerned about the common requirement for an extraordinary amount of computing power to handle cognitive processing. Several mentioned the challenge of developing non-English applications because most of the research has been in English-based systems. Perhaps most intriguing in terms of issues, though, were the predictable “What-if” questions: will we lose the institutional memory that originally trained the system? If so and if the system breaks down, will we be able to fix it? Centralized systems are always a problem, they said. They must be up and running 24/7. They must be reliable. That’s a challenge for any system. Cognitive systems’ lack of a track record in production operations sets off risk alarm signals for many.

Finally, these cognitive experimenters pointed to interaction design as a great unknown, especially for non-IT, non-analyst business users who need access to data stores but won’t understand the system design behind the interface. Right now there are experiments, but no accepted best practices.

It is apparent that SAS is seizing this trend toward cognitive computing. The announcement of SAS Viya™ at this conference, along with a variety of tools for both their loyal developer and analyst base and a wider business user audience positions them nicely as both a partner with other cognitive and IOT platforms and as a potential competitor.

[image error]September 16, 2022

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 20: Lilia Efimova

Lilia Efimova works at the intersection of social media, the changing workplace, knowledge, and learning. She is passionate about technology and understanding how people work. Lilia is Russian, lives in the Netherlands, and likes the “between two countries” dimension of her life for the rich perspective it provides.

Lilia has been blogging since 2002 on finding flow, growing ideas, crossing boundaries, creating spaces, and the bigger picture behind all that. She excels at asking questions, recognizing patterns, initiating change, facilitating learning, spanning boundaries, and translating between research and practice. Her specialties include the social web, collaborative technologies, communities of practice, research, knowledge mapping, information management, workshop facilitation, change management, and expertise location. She describes herself as an unschooling facilitator — facilitating learning outside of educational organizations.

Profiles LinkedIn Mathemagenic Blog Facebook KM4Dev Profiles in Knowledge BookPassion At Work: Blogging Practices of Knowledge Workers

Other Content

Twitter

Blog

PhD Research

ResearchGate

ACM

Publications

SlideShare

Getting value from employee weblogs: a knowledge management approach

On learning myths and learning styles

Other Content

Twitter

Blog

PhD Research

ResearchGate

ACM

Publications

SlideShare

Getting value from employee weblogs: a knowledge management approach

On learning myths and learning stylesSeveral publications came to my attention recently which focus on debunking “myths” in instructional design. Usually, I have mixed feelings about those — a lot of it makes sense, but at a deeper level, I have a feeling that it is often about replacing one research-based myth with an updated one. All of that is pretty much in the same domain of complicated, where experts know the answers and your choice is limited to which expert do you believe the most.

For example, a take on learning styles, Stop “Fixing” Your Brain by Believing in Learning Styles, which shows how different assumptions about sensory learning styles could be detrimental to learning. The post then goes on to point that those “predefined” learning styles are fluid and could be changed with time via neuroplasticity:

The study of neuroplasticity tells us that through challenging experiences, we can biologically change our brain. When we think about what this means for learning and our current learning habits, if you only have experience using certain strategies for learning (e.g., note-copying, highlighting, flashcards), then your brain’s neural pathway is stronger for those strategies. However, neuroplasticity suggests that with practice, you can develop other strategies that would help you learn in any environment.

Facilitating learning of three very different kids I see the truth behind both, “factory settings” that lead to the development of certain sensory preferences in learning and neuroplasticity. The question is at what costs “being able to learn in any environment” comes and if it is worth it. The answer to this question is different depending on the context.

In school settings, when you need a program to help many different kids to reach particular goals, it is logical to design for neuroplasticity. It should give good results “on average” by engaging different existing learning strategies and stretching into developing new ones.

From the perspective of an individual learner, it is different. Personally, I do not see the point of turning everyone into a well-rounded person able to learn in any environment. I see a lot of value in strengths-based development and being able to choose and shape your own environment in a way where your strengths could help to deal with the challenges. This is where paying attention to personal patterns in learning makes a difference (reading-related example and another one for a contrast).

As a researcher living in a fast-changing world I am also very much aware of the limits of any research in predicting what methods and techniques (±directions of pushing neuroplasticity with instructional design) would benefit learners in the long term. And all that without touching on bias coming from studying WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) societies and epistemological beliefs behind one’s research.

[image error]September 10, 2022

Hubert Saint-Onge: Profiles in Knowledge

This is the 83rd article in the Profiles in Knowledge series featuring thought leaders in knowledge management. Hubert Saint-Onge is the founder and Principal of SaintOnge Alliance, with expertise in knowledge management, strategy, organization capability and learning, performance enhancement through culture renewal, and leadership development.

He developed and refined a model called the Knowledge Assets Framework. This model strategically integrates business plans with branding, leadership, and people management to optimize the performance of an organization.

Hubert specializes in organizational performance, formulation and implementation of knowledge and learning strategies, development of communities of practice, strategic development of organizational capabilities, values alignment, development of leadership teams, leadership assessment and succession planning, leadership development, assessment of customer-perceived value, and development and implementation of branding strategy

The focus of this work is on strategic planning, organizational change and transformation, collaboration, knowledge sharing, capability building, and leadership development. He lives in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.

I first heard Hubert speak in 2002 when he presented a webinar at HP: “Tying Knowledge to Customers.” I later invited him to present on the September 2008 SIKM Leaders Community call: “Collaborative Networks and the New Enterprise.”

Background ExperiencePrincipal, SaintOnge Alliance, 2003 — PresentSenior Vice President, Strategic Capabilities, Clarica, 1996–2002Vice President, Leadership and Organization Development, CIBC, 1990–1996EducationCarlton University (Ottawa) — MA, Political Science (International Affairs), 1972–1973Glendon Campus of York University — BA, Political Science, 1969–1972ProfilesAboutLinkedInFacebookRotman School of ManagementEntovationContentSaint-Onge Toolkit

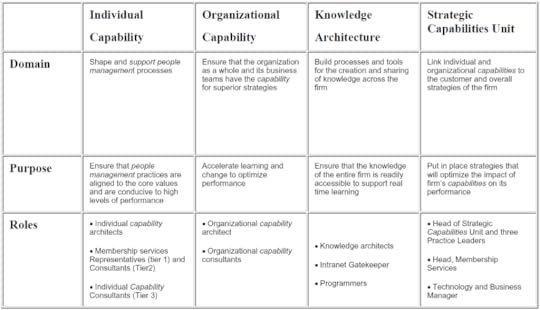

ExperiencePrincipal, SaintOnge Alliance, 2003 — PresentSenior Vice President, Strategic Capabilities, Clarica, 1996–2002Vice President, Leadership and Organization Development, CIBC, 1990–1996EducationCarlton University (Ottawa) — MA, Political Science (International Affairs), 1972–1973Glendon Campus of York University — BA, Political Science, 1969–1972ProfilesAboutLinkedInFacebookRotman School of ManagementEntovationContentSaint-Onge ToolkitFor over a decade, Hubert Saint-Onge has been refining a model known as the Knowledge Assets Framework. This proven model is designed for the strategic integration of business plans with people management systems, using technology architecture and organizational infrastructure.

Hubert Saint-Onge is well-known in the international community of knowledge assets practitioners. He began his life work in knowledge management and has been lauded for his innovative thinking and leadership skills. He has a solid track record in leading large organizations (previously as Vice President of The Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce and currently as Vice President of Strategic Capabilities at Clarica Insurance) to become knowledge-focused enterprises. Clarica recently ranked 17th among “Most Admired Knowledge Enterprises” in the world.

Mr. Saint-Onge has done seminal work in the area of corporate cultural values and customer relationships. He is a passionate and compelling presenter, and able to easily synthesize disparate perspectives into themes that will assist dialogue. Exposure to his ideas will permanently enlarge your awareness of how organizations function.

The Saint-Onge Toolkit is a compilation of his signature PPT slides enhanced by rich media (video clips from live presentations). Add to this Hubert’s lessons learned from the field and you have a comprehensive blueprint for a knowledge strategy implementation appropriate for any firm.

The Saint-Onge Toolkit is a support system for consultants, CKOs and individuals who wish to create a knowledge-focused strategy within organizations. The tools and methods included in the Toolkit are developed for conceptually agile people who are practical in their knowledge management approach.

Currently the Toolkit includes a Knowledge Management primer, Hubert Saint-Onge’s Knowledge Assets Framework, a module on Values mapping, an outline of a three-year Knowledge Strategy implementation process, a KM anthology, a library of video clips and white papers, a series of PowerPoint presentations with voice clips and a module on Customer Capital.

In the Saint-Onge Toolkit Knowledge Management Primer you will learn:

Why intangible assets must be managed differently from tangible assets.How knowledge management can reduce the gap between organizational capabilities and market demands.How to create new opportunities for your organization before the marketplace defines the need.The Knowledge Assets Framework: An Overview

Historically, every organization has had to manage its knowledge in one way or another. This module covers the systematic pursuit, capture and sharing of knowledge and how this process can leverage the effectiveness of individuals, teams and entire organizations.

The module is structured in three sections: The Knowledge Assets Framework, its subset The Knowledge Strategy, and a Case Study of a Knowledge Strategy success story.

Section I, The Knowledge Assets Framework, presents the wider context (which encompasses the Knowledge Strategy) and offers a new perspective on how the organization creates value through the management of its intangible assets. It also covers the measurement of intangible assets at the enterprise level, which complements the work of Karl Erik Sveiby (see The Sveiby Toolkit).

How does one identify the intangible assets of an enterprise?Why have intangible assets become important to the viability of an organization?How is the management of intangible assets different from the management of tangible assets?What are the implications of a Knowledge Assets Framework for measurement?Section II, The Knowledge Strategy, introduces the business rationale which justifies the investment required. The Knowledge Strategy addresses how to launch a coordinated approach to knowledge management in the organization. We will articulate a vision of what the end product might be for an organization once the key objectives of the Knowledge Strategy have been realized. A blueprint for constructing a Knowledge Strategy will be put forward (in the long version). It will describe the principles that should guide its implementation.

In Section III, Case Study, we will examine one project (the successful acquisition of 2nd Corporation) of a financial services organization, including the principles, the strategy, the orchestration, the business rationale (which justified the investment) and a methodology for measuring results.

Even though different organizations will have different questions, answers and approaches to implementing a Knowledge Strategy, the fundamental principles will remain the same and many of the dilemmas are common to all organizations. Examining real implementations like the Case Study will give us a fresh perspective on the issues and opportunities surrounding a Knowledge Strategy approach to creating value in our organizations.

In the end, an effective Knowledge Strategy should prove to be one of the key factors that will differentiate any organization in the marketplace!

Values: The story of value mapping at The Company

Hubert Saint-Onge developed this template for his own use, as he recounted the story of a successful values mapping project at The Company. As part of the Saint-Onge Toolkit, this template is available to any CEO or CKO for customization and is suitable is suitable for distribution as part of a corporate communications program on values mapping. It articulates in general terms the rationale for values work, covering:

organizational valuesknowledge capitalcontextapproachlanguage and labelingcore valuesdeploymentbrandingvalues as the lens of the organizationIts content is based on the following critical assumptions:

Your organization has conducted (or is in the progress of conducting) an in-depth review of the history of the firm through an analysis of documents dating back to the creation of the company;Your organization has already completed extensive work on individual and corporate values and its leaders are positioned to articulate those values;Your organization is actively working towards adopting a ‘customer-centric’ position in terms corporate strategy;Your organization has been actively working toward a definition of its brand and is currently developing a company-wide communications program on your brand;Your organization is actively creating new organizational structure.If these assumptions are satisfied, then appropriate substitutions at designated text placeholders should provide you with a 32-page booklet suitable for a company-wide communications program on values mapping.

Text placeholders will require appropriate text substitution for the following:

[Knowledge Capital Model] This requires specifying an appropriate model such as the Knowledge Assets Framework, Intangible Assets Monitor, Enterprise Capital Model, Balanced Scorecard etc.[A statement of your company’s corporate values][Describe your company’s key products and the strength of your brand. Describe any brand surveys conducted with your customers. Describe any learned outcomes from the dialogue with your customers.][Specify number of people and specific groups who responded to your internal values survey][Specify a specific corporate behavior attributable to a particular corporate value][Specify three core values of your company][Training initiative] Identify a training initiative that is also an implicitly reinforced core competence.[Describe recent strategic projects (such as key alliances) which will contribute to corporate growth]The Knowledge Assets Framework is a comprehensive model for leveraging knowledge for value creation, so that knowledge activities in an organization will have maximum impact. It comprises three pillars: knowledge architecture, technology infrastructure and culture.

An integral part of the Knowledge Assets Framework is the articulation of a Knowledge Strategy. This is best developed through a set of multi-dimensional questions to be addressed by the CKO through dialogue with other members of the organization. The questions cover the areas of intangible asset management, business case development, the role of learning and implementation issues.

Knowledge value creation must become a key theme in an organization before implementation begins. A scale determining the ‘knowledge readiness’ of an organization, or its ‘absorptive capability’ will help to determine what pre-cursors need to be in place prior to implementation.

Do we understand the intangible assets of the enterprise?Why have intangible assets become important to the viability of our organization?How is the management of intangible assets different from that of tangible assets?What are the implications of this framework for measurement?Where does knowledge and learning fit in this framework?Developing the business case:

How does one formulate the business case for a knowledge strategy to be put in place?What are the key drivers?What are the possible key areas of business impact?Is knowledge a top-line or a bottom-line contributor to the business?To what extent is there a link between the knowledge strategy and objectives for business growth?Developing the Knowledge Strategy:

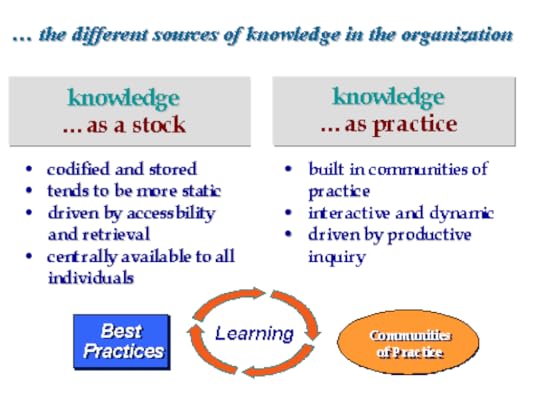

What do we consider to be the key components of a knowledge strategy? Does it imply a sequence or a “building block” approach?What is the relative emphasis placed on explicit versus tacit knowledge?To what extent is the strategy “technology” versus “culture” driven?Is the strategy based mostly on supporting more effective individual work or on supporting collaboration across individuals and teams?Is the main feed of knowledge internal or external to the organization?Is the strategy mostly oriented to a “knowledge as a stock” view (i.e., access and retrieval) or “knowledge as a flow” view (i.e., interaction, relationships and communities of practice)?To what extent is the strategy oriented to enhance “internal capability” as opposed to enhance the interface with customers/suppliers?Is our strategy best characterized as “grass root” or as “coordinated from the center”? What is the balance between creating the overall infrastructure and architecture and building discrete knowledge initiatives to serve specific business needs?Issues in Implementing the Knowledge Strategy:

Do the implementation plans explicitly take into account the “absorptive” capability of the organization?What role does the senior leadership of the organization play in increasing receptivity to the knowledge strategy?To what extent should the implementation approach take into account the main drivers/inhibitors for the implementation of the knowledge strategy in the organization?Knowledge Management Anthology

anthology

A collection of writings.A miscellany, assortment, or catalog, as of thoughts, comments, or ideas: “The Irish love their constitution for what it is: an anthology of the clerical-nationalist ideas of 1936” (Economist).[Medieval Greek anthologi, collection of epigrams, from Greek, flower gathering, from anthologein, to gather flowers : antho-, antho- + logos, a gathering (from legein, to gather. See leg- in Indo-European Roots).]

This KM anthology is a compilation of ideas organized into the following topics:

What is Knowledge?

The Business RationaleOrganizational KnowledgeTacit and ExplicitCharacteristicsOrganizational KnowledgeObtaining Knowledge

Capturing vs. CreatingThinking of Knowledge

Internal MarketAsset of KnowledgeIntangible KnowledgeStock or Flow?Barriers and PitfallsCase Studies

General MotorsDow ChemicalsSiemensU.S. ArmyAir LiquideCSCBuckman LabsHewlett-PackardScandiaChevron — TLOMcKinsey & Co.Booz Allen & HamiltonBritish PetroleumPostsTwitterLinkedIn PostsBlogHow to assess your organization’s capability to execute strategyIntegrating a new leader to a management teamCreating space for the exercise of judgmentBalancing “fast” and “slow” thinking for a more effective use of timeArticlesLinkedIn ArticlesKonverge and KnowTacit knowledge: the key to the strategic alignment of intellectual capitalHow Knowledge Management Adds Critical Value to Distribution Channel ManagementThe evolutionary organization: avoiding a Titanic Fate with Peter A.C. SmithManaging Toward InterdependenceThe Power of Shared KnowledgeStrategic Capabilities Shaping Human Resource Management within the Knowledge-Driven Enterprise

Avoiding the Sudden-Death Syndrome

Avoiding the Sudden-Death SyndromeAs vice president of people, knowledge, and strategies at Clarica insurance company, Hubert Saint-Onge is one of a new breed of chief knowledge officers charged with assessing and managing corporate knowledge capital. He spoke with Exec about the role of intellectual capital at the Waterloo, Ontario-based company, and the need for understanding and exploiting intangible assets.

Why is it important for companies to understand intellectual capital?

Intellectual capital is about looking at the firm from a new perspective. In the past we have viewed firms mostly from the tangible- and financial-assets perspective. But you can define the value of a company in three components: tangible assets, financial capital, and intangible assets. So we’re trying to see the firm from the perspective of those intangible assets, and see how those assets contribute to value. Obviously, you still need to manage the tangible assets to stay in business and operate. But we think that they are not what’s going to create competitive advantage for us.

We divide intangible assets — the intellectual capital — into three areas: human capital, which includes the capabilities of individuals to provide solutions to customers; structural capital, which is the capability of the organization to meet market requirements; and customer capital, which is the penetration, width, loyalty, and profitability of our franchise. What senior executives tend to say is that somewhere around 80 percent of the worth of the firm is in their intangible assets. But we have all been managing firms as if they are driven by tangible assets. Our accounting systems bias this allocation of attention in a big way, because the tangibles are the only thing that we are in fact measuring or monitoring or trending.

However, we’ve come to believe that strategic survival depends on how we manage the intangible assets of the firm. And if those intangible assets are actually being undermined, you are losing your competitive advantage in the marketplace. The problem is that, by and large, business leaders have not been actively managing their intangible assets. They are very actively managing the tangible assets, and very actively managing the financial assets. But one can say with confidence that they give only very partial attention to the intangible assets.

Do most executives appreciate this problem?

I think that most executives are becoming more attuned to this issue. I think most senior folks in private moments and times of candor will tell you that they understand that the rules of the game are changing — and that they are not all that clear on what the new rules are. But they do know that firms seem to be disappearing at an alarming rate — firms that they consider to be well-tooled, well-equipped, capable. We call this the sudden-death syndrome, and it comes in part from not knowing how to nurture, harness, and grow your intellectual capital.

When I sit down in front of CEOs and senior folks or speak in groups I will say, “OK, can you tell me whether right now you are building up or depleting your customer capital?” And if they are being candid they will tell you, a glimmer of fear in their eyes, that they don’t know. We haven’t put the mechanisms in place either to monitor or to understand what is happening to our intangible assets.

That means you can be losing customer capital by the ton and not even realize it. Think of a chart showing organizational capability, which is really based on structural capital, and market demands. Market demands are going up exponentially, so if your organizational capability is going up linearly, you’re falling behind in your ability to meet customers’ expectations. Even though your capability is increasing somewhat, you’re losing ground. But you can’t see that growing gap, because you can’t track how well you are building your intangible-based capability.

When that market-demand curve takes off and leaves you behind, it takes a while for the financial reality to catch up with the reality that’s first reflected in the intangible assets — the declining customer capital. So you might still have a great financial picture, but essentially you are undermining your future. That gives you the sudden-death syndrome — the kind of situation where the company celebrates its best year ever, and 18 months later it’s gone beyond hope of repair.

What is being done at The Mutual Group in the area of learning and intellectual capital?

At Mutual we are working to get a clear sense of our intangible assets, of the capabilities of our individuals and the organization as a whole. We are moving into Asia and expanding our presence in the United States, so we want to make sure we are leveraging our intangible assets to improve our competitive position in all our markets.

The CEO here at Mutual pointed out that one of the things that we are all doing is trying to measure intangible assets in the same way that we measure the tangible ones, and that is never going to work. So at this point we are putting in place an initial attempt to measure our intangible assets. We are in the very early stages of that. We are also putting in place a learning/knowledge system based on groupware. And we are doing a lot of work around customer knowledge — really tapping into what the firm knows in terms of customer knowledge.

We are finding that the firm knows more than it knows, if you will. We have some 2,000 agents out there in Canada alone that know a whole lot about our customers. But I don’t think we are as good as we need to be at capturing the insights that these people carry. So we are really working hard at building a customer-knowledge capability.

You recently wrote about the importance of “tacit knowledge” in the organization. What is that?

Knowledge is made up of explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge. Take a phone conversation, for example: The information going over the wires is the formal, explicit knowledge. But it’s the tacit knowledge of the speakers on both ends — what they know about the other person, the context of the information, and so forth — that allows them to decode that explicit knowledge and give it a richer meaning. Most managers think only of the explicit knowledge. So what is happening with a lot of IT systems is that companies are building an information mountain that people are buried in, rather than on top of, because they don’t have the tacit knowledge to interpret it.

How, in a practical sense, do you apply tacit knowledge to those mountains of information?

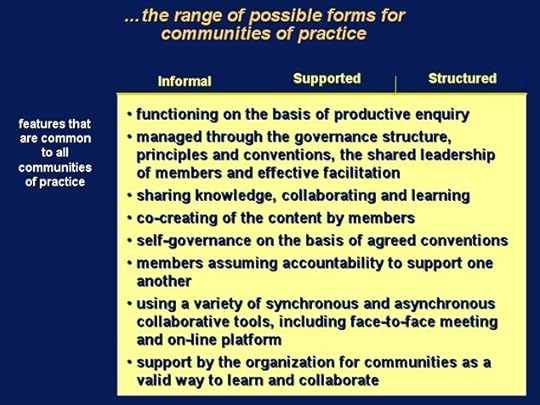

I think it calls for more of a cultural solution than a technical solution. One way is by building communities of knowledge where people work together in a relatively small group to derive and marshal insights from information. Each community should have some common purpose, an affinity of task or an affinity of occupation.

For instance, we might build a sales-management community by bringing together 20 or so of our good sales agents and letting them interact with those mountains of information through a shared database. They could exchange their respective learning and understanding, interact as a community around the information, build up tacit knowledge, and use it to apply that store of explicit knowledge and come up with new ideas or approaches.

You mentioned that The Mutual Group is in the early stages of creating measurements for its intangible assets. But the measurement of such assets is still a fairly inexact science, isn’t it?

It is very inexact and actually quite difficult. It is difficult to isolate variables. Also, the generation of intellectual capital manifests itself differently in each organization — meaning you can’t simply apply one company’s approach to another. So it’s not an easy proposition.

Let me give you an analogy of how we view this. In subatomic physics, scientists are finding that you can’t measure both the size and direction of a subatomic particle at the same time. I think that when we are dealing with intangible assets, we have to make the same kind of choice: Will we measure absolute volume, or will we measure the flow and the direction of the flow? I believe that we need to focus on that second area — measuring intangible assets in terms of trends, up or down, rather than absolute value.

We want to be able to determine ratios so that when we invest in our intangible assets, we can determine the impact that money will have. I’d like to be able to say, OK, if we spend $5 on our human and structural capital, it should bring $10 in financial capital. Right now, that’s what we do with financial capital: I know that if I increase my lending capital, I can add 12%, 14%, 16% to the bottom line. But if I invest that money in the development of our human capital, it’s just an expense in our current accounting format. So it creates a bias against the investment in intangible assets.

Are we at the point where we can come up with those ratios?

No, we’re certainly not there. We’re really in the first couple years of a 10-year ramp. But that’s where we want to be, and that’s where we need to be.

Articles by OthersA conversation with Hubert Saint‐Onge by Jay ChatzkelPower Of Shared Knowledge by Jack VinsonConductive Organizations are always on the move by Jack VinsonBlogs are knowledge management tools by Jack VinsonHubert’s error by Dave SnowdenIs your organization conductive? by Bertrand DuperrinSuccessful Knowledge Management Implementation by Dan KirschCollaborative Networks & The New Enterprise by Eric MackThe Nine Dilemmas Leaders Face by Thomas StewartBroad-based leadership vs. high-visibility leaders.Independence vs. interdependence.Long term vs. short term.Creativity vs. discipline.Trust vs. change.Bureaucracy busting vs. economies of scale.People vs. productivity.Leadership vs. capability.Revenue growth vs. cost containment.CommunitiesSIKM Leaders Community: September 2008 Call: Hubert Saint-Onge — Collaborative Networks and the New EnterpriseAssociation of Knowledgework (AOK)Conflicting Views on Training and CoPsWhat Worked, Didn’t Work at ClaricaPresentationsCommunities of Practice Slide for AOK How to re-ignite a sense of community in companies to increase collaboration and agilityKMWorld & Intranets2008 A205: Integration Strategies2007 A103: Collaborative Networks & The New Enterprise2005 Keynote: Building Capability in the Conductive Organization2003 Keynote: Knowledge, Learning & ProductivityPodcastsAre you being a thought partner? A Disruptive ConversationOpen to InfluenceVideosYouTubeRekindle CommunityIndividual learningNoble causeTrust advantageDynamic resourcingTrust innovationRadical opennessEmpowering individualsBegin with a level of analysis at an organization-wide levelUnderstanding the Importance of ValuesThe Inner Game of LeadershipValues Mapping in an OrganizationPrescribing a Careful, Measured Approach to Identifying ValuesCommitment vs. Loyalty, the new employment contract explainedShared values form the foundation for innovation and organizational agilityEmpowerment and the evolution of valuesValues Clarification and the Individual. What’s in it for me?The Next Step: Building External Networks of Value CreationOrganizational Values and Brand Identity: Is there a Connection?Measuring Up: The Metrics of Brand Identity and Shared ValuesBooksBeyond the Deal: A Revolutionary Framework for Successful Mergers & Acquisitions That Achieve Breakthrough Performance Gains with Jay Chatzkel

How to re-ignite a sense of community in companies to increase collaboration and agilityKMWorld & Intranets2008 A205: Integration Strategies2007 A103: Collaborative Networks & The New Enterprise2005 Keynote: Building Capability in the Conductive Organization2003 Keynote: Knowledge, Learning & ProductivityPodcastsAre you being a thought partner? A Disruptive ConversationOpen to InfluenceVideosYouTubeRekindle CommunityIndividual learningNoble causeTrust advantageDynamic resourcingTrust innovationRadical opennessEmpowering individualsBegin with a level of analysis at an organization-wide levelUnderstanding the Importance of ValuesThe Inner Game of LeadershipValues Mapping in an OrganizationPrescribing a Careful, Measured Approach to Identifying ValuesCommitment vs. Loyalty, the new employment contract explainedShared values form the foundation for innovation and organizational agilityEmpowerment and the evolution of valuesValues Clarification and the Individual. What’s in it for me?The Next Step: Building External Networks of Value CreationOrganizational Values and Brand Identity: Is there a Connection?Measuring Up: The Metrics of Brand Identity and Shared ValuesBooksBeyond the Deal: A Revolutionary Framework for Successful Mergers & Acquisitions That Achieve Breakthrough Performance Gains with Jay Chatzkel Leveraging Communities of Practice for Strategic Advantage with Debra WallaceChapter 11 Communities as Catalysts for Change

Leveraging Communities of Practice for Strategic Advantage with Debra WallaceChapter 11 Communities as Catalysts for Change The Conductive Organization: Building Beyond Sustainability with Charles Armstrong

The Conductive Organization: Building Beyond Sustainability with Charles Armstrong Breakthrough Performance for Mergers and Acquisitions in the Knowledge Era: The Knowledge Approach to Mergers and Acquisitions with Jay Chatzkel

Breakthrough Performance for Mergers and Acquisitions in the Knowledge Era: The Knowledge Approach to Mergers and Acquisitions with Jay Chatzkel Book ChaptersPerformance Through Learning: Knowledge Management In Practice — by Kurt April, Carol Gorelick, and Nick Milton — Chapter 13 (with Debra Wallace): Generating Capabilities in Communities of Practice: The Clarica StoryKnowledge and Strategy edited by Michael Zack — Chapter 12: Tacit Knowledge: The Key to the Strategic Alignment of Intellectual CapitalKnowledge Capital: How Knowledge-Based Enterprises Really Get Built by Jay Chatzkel — Chapter 14: Creating and Implementing a Knowledge StrategyNext Generation Knowledge Management: Transforming theory into practice edited by Jerry Ash — Chapter 14 (with Debra Wallace): Communities of Practice Supplant Training[image error]

Book ChaptersPerformance Through Learning: Knowledge Management In Practice — by Kurt April, Carol Gorelick, and Nick Milton — Chapter 13 (with Debra Wallace): Generating Capabilities in Communities of Practice: The Clarica StoryKnowledge and Strategy edited by Michael Zack — Chapter 12: Tacit Knowledge: The Key to the Strategic Alignment of Intellectual CapitalKnowledge Capital: How Knowledge-Based Enterprises Really Get Built by Jay Chatzkel — Chapter 14: Creating and Implementing a Knowledge StrategyNext Generation Knowledge Management: Transforming theory into practice edited by Jerry Ash — Chapter 14 (with Debra Wallace): Communities of Practice Supplant Training[image error]

September 9, 2022

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 19: Amy Edmondson

Amy C. Edmondson is the Novartis Professor of Leadership and Management at the Harvard Business School, a chair established to support the study of human interactions that lead to the creation of successful enterprises that contribute to the betterment of society.

Amy is a thought leader in several areas that are important for knowledge management: organizational learning, cross-boundary teaming, innovation, and eliminating fear in organizations. She is a pioneer and champion of psychological safety, and studies people, projects, and organizations to uncover the secrets of successful teaming.

Amy’s work on psychological safety has been groundbreaking. Her blueprint on creating a fear-free culture is essential, she argues, for organizations to be able to thrive in today’s knowledge economy in which new ideas and critical thought are essential to success. She has also explored the concept of teaming in dynamic work environments and demonstrated how cross-organizational teaming can impact the building of smart cities.

Her research examines psychological safety and cross-boundary teaming within and between organizations. She is particularly interested in how leaders enable the learning and collaboration that are vital to performance in a dynamic environment.

Profiles Amy C. Edmondson Harvard LinkedIn Thinkers50 Wikipedia Profiles in Knowledge Books Teaming: How Organizations Learn, Innovate, and Compete in the Knowledge Economy Teaming to Innovate Building the Future: Big Teaming for Audacious Innovation with Susan Salter Reynolds Extreme Teaming: Lessons in Complex, Cross-Sector Leadership with Jean-François Harvey Organizational Learning and Competitive Advantage edited with Bertrand Moingeon The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth Other Content

LinkedIn Articles

LinkedIn Posts

Twitter

Publications

Publications — HBS

Is Yours a Learning Organization? with David A. Garvin and Francesca GinoBuilding Blocks of the Learning Organization

Other Content

LinkedIn Articles

LinkedIn Posts

Twitter

Publications

Publications — HBS

Is Yours a Learning Organization? with David A. Garvin and Francesca GinoBuilding Blocks of the Learning OrganizationBuilding Block 1: A supportive learning environment.

An environment that supports learning has four distinguishing characteristics.

1. Psychological safety.

To learn, employees cannot fear being belittled or marginalized when they disagree with peers or authority figures, ask naive questions, own up to mistakes, or present a minority viewpoint. Instead, they must be comfortable expressing their thoughts about the work at hand.

2. Appreciation of differences.

Learning occurs when people become aware of opposing ideas. Recognizing the value of competing functional outlooks and alternative worldviews increases energy and motivation, sparks fresh thinking, and prevents lethargy and drift.

3. Openness to new ideas.

Learning is not simply about correcting mistakes and solving problems. It is also about crafting novel approaches. Employees should be encouraged to take risks and explore the untested and unknown.

4. Time for reflection.

All too many managers are judged by the sheer number of hours they work and the tasks they accomplish. When people are too busy or overstressed by deadlines and scheduling pressures, however, their ability to think analytically and creatively is compromised. They become less able to diagnose problems and learn from their experiences. Supportive learning environments allow time for a pause in the action and encourage thoughtful review of the organization’s processes.

Building Block 2: Concrete learning processes and practices.

For maximum impact, knowledge must be shared in systematic and clearly defined ways. Sharing can take place among individuals, groups, or whole organizations. Knowledge can move laterally or vertically within a firm. The knowledge-sharing process can, for instance, be internally focused, with an eye toward taking corrective action. Right after a project is completed, the process might call for post-audits or reviews that are then shared with others engaged in similar tasks. Alternatively, knowledge sharing can be externally oriented — for instance, it might include regularly scheduled forums with customers or subject-matter experts to gain their perspectives on the company’s activities or challenges. Together, these concrete processes ensure that essential information moves quickly and efficiently into the hands and heads of those who need it.

Perhaps the best-known example of this approach is the U.S. Army’s After Action Review (AAR) process, now widely used by many companies, which involves a systematic debriefing after every mission, project, or critical activity. This process is framed by four simple questions: What did we set out to do? What actually happened? Why did it happen? What do we do next time? (Which activities do we sustain, and which do we improve?) In the army, lessons move quickly up and down the chain of command, and laterally through sanctioned websites. Then the results are codified by the Center for Army Lessons Learned, or CALL. Such dissemination and codification of learning is vital for any organization.

Building Block 3: Leadership that reinforces learning.

Organizational learning is strongly influenced by the behavior of leaders. When leaders actively question and listen to employees — and thereby prompt dialogue and debate — people in the institution feel encouraged to learn. If leaders signal the importance of spending time on problem identification, knowledge transfer, and reflective post-audits, these activities are likely to flourish. When people in power demonstrate through their own behavior a willingness to entertain alternative points of view, employees feel emboldened to offer new ideas and options.

[image error]September 2, 2022

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 18: Vanessa DiMauro

Vanessa DiMauro is CEO of Leader Networks, a research and consulting firm that helps companies use digital and social technologies to gain competitive advantage. She is a strategist, advisor, researcher, author, and speaker. Vanessa is a pioneer in the field of online communities and in using digital business solutions to gain customer insight and increase revenue. Before founding Leader Networks, she held leadership positions at Cambridge Technology Partners, Computerworld, and CXO Systems.

Vanessa was named one of Forbes’s Top 40 Social Media Masters Worldwide and one of CEOWorld’s Most Powerful Women in Social Media and identified as one of 20 Top Digital Influencers of 2018 by Whatagraph. She was also recognized as Research Fellow of the Year by the Society for New Communications Research.

Vanessa was on the faculty at Columbia University in the Information and Knowledge Strategy (IKNS) Master’s program. I met her when we were both presenting to the class. She specializes in strategy, communities, knowledge management, and marketing

Profiles LinkedIn Leader Networks Profiles in Knowledge Books The Social Mind: A Research Study with Peter Auditore and Don Bulmer — PDF Copy The New Symbiosis of Professional Networks: Social Media’s Impact on Business and Decision-Making

with Don Bulmer —

Social Media Today Article

—

Survey Results (PDF)

—

Slides

The New Symbiosis of Professional Networks: Social Media’s Impact on Business and Decision-Making

with Don Bulmer —

Social Media Today Article

—

Survey Results (PDF)

—

Slides

Other Content

Publications

Blog

Medium

Twitter

LinkedIn Articles

LinkedIn Posts

Google Scholar

Semantic Scholar

ResearchGate

SlideShare

SIKM Leaders Community presentation —

Accelerating Knowledge at Scale: A mini case study

The Socially Enabled Enterprise Study

Socially Driven Collaboration Research Study

The Business Impact of Online Communities

Other Content

Publications

Blog

Medium

Twitter

LinkedIn Articles

LinkedIn Posts

Google Scholar

Semantic Scholar

ResearchGate

SlideShare

SIKM Leaders Community presentation —

Accelerating Knowledge at Scale: A mini case study

The Socially Enabled Enterprise Study

Socially Driven Collaboration Research Study

The Business Impact of Online Communities Seven Failures of Companies that Unplug Their Online CommunitiesCommunity goals are skewed to leadership — not member — needs.“Tool talk precedes strategy.Mausoleums are built instead of Sherpa tents. An online community requires continual enhancements driven by member feedback. Many make their online community planning into a long, drawn-out process. That’s a recipe for disaster. Communities are in constant flux from changing member needs, business objectives, technical improvements, and social norms. Community plans should focus on short sprints — not a big-bang approach.Failure to feed the content beast. Great content takes great effort, like getting a company’s thought leaders to put pen to digital paper, conducting studies, and inviting members to provide their expertise. Without it, members won’t come or stay for long.Poor community management skills. Community management is becoming a profession. Community managers need superior communications skills, the ability to cultivate strong relations, project management prowess, a research background, and social media proficiency.Chasing only business metrics and not member-driven ones. How has the community helped members better resolve their problems? Have community discussions bubbled up product or service defects? Measure what matters.No community zealot at the top. Online communities need a strong executive champion.[image error]

Seven Failures of Companies that Unplug Their Online CommunitiesCommunity goals are skewed to leadership — not member — needs.“Tool talk precedes strategy.Mausoleums are built instead of Sherpa tents. An online community requires continual enhancements driven by member feedback. Many make their online community planning into a long, drawn-out process. That’s a recipe for disaster. Communities are in constant flux from changing member needs, business objectives, technical improvements, and social norms. Community plans should focus on short sprints — not a big-bang approach.Failure to feed the content beast. Great content takes great effort, like getting a company’s thought leaders to put pen to digital paper, conducting studies, and inviting members to provide their expertise. Without it, members won’t come or stay for long.Poor community management skills. Community management is becoming a profession. Community managers need superior communications skills, the ability to cultivate strong relations, project management prowess, a research background, and social media proficiency.Chasing only business metrics and not member-driven ones. How has the community helped members better resolve their problems? Have community discussions bubbled up product or service defects? Measure what matters.No community zealot at the top. Online communities need a strong executive champion.[image error]

August 26, 2022

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 17: Kimiz Dalkir

Kimiz Dalkir is an Associate Professor and Director of the School of Information Studies at McGill University with a Ph.D. in Educational Technology, and an MBA and B.Sc. in Human Genetics. Her research focuses on tacit knowledge sharing and organizational learning. Prior to joining McGill, Kimiz was Global Practice Leader KM for Fujitsu Consulting, and she has worked in the field of knowledge transfer and retention with clients in Europe, Japan and North America.

Her background comprises artificial intelligence, cognitive science, online learning and online job aid systems, information and knowledge management, and organizational learning and memory. Her goals are to contribute to the development of Knowledge Management as an academic discipline; to conduct research on how tacit knowledge can best be identified, organized, shared, used, and stored for future research (particularly in non-profit settings); and to help train future KM researchers and practitioners. Her specialties are information and knowledge management strategy and systems, knowledge taxonomies, and intellectual capital management.

Profiles LinkedIn McGill University School of Information Studies Profiles in Knowledge BookKnowledge Management in Theory and Practice, Third Edition

Table of Contents

Introduction to Knowledge ManagementKnowledge Management ProcessesKnowledge Management ModelsKnowledge Capture and CodificationKnowledge SharingFinding KnowledgeOrganizational CultureKnowledge Management ToolsKnowledge Management Strategy and PlanningEvaluating Knowledge ManagementOrganizational Learning and Organizational MemoryKnowledge Continuity ManagementThe Knowledge Management TeamFuture Challenges for KMKM ResourcesOther Content LinkedIn Posts Google Scholar Semantic Scholar ResearchGate IGI Global A Holistic View of the Knowledge Life Cycle: The Knowledge Management Cycle (KMC) ModelThe Knowledge Management Cycle (KMC) model advanced in this paper contains seven phases: identify, store, share, use, learn, improve, and create:

1. Identify and/or Create — A knowledge request may be triggered for numerous reasons, some of which include strategic and/or operational problem solving, decision making, knowledge gap analysis, or innovation. When a request for knowledge is made, the searcher must identify if appropriate knowledge exists in-house, or if appropriate knowledge assets need to be created or acquired. This is one of the reasons why these phases are interrelated and grouped together in the KMC model. In some cases, the searcher may find that they will both identify existing appropriate knowledge assets and also have a need to create new knowledge assets.

1.1. Identify — The identify stage involves eliciting codified and encapsulated knowledge assets (e.g., documents in electronic and print format stored in a knowledge repository and/or live demonstrations and observations of artifacts). In addition, this stage identifies subjectively held tacit knowledge through methods such as network analysis or brainstorming sessions. Inevitably, this will be interrelated with the store phase. Along with effectively searching for knowledge assets, the identify stage subsequently involves analyzing and assessing the assets based on specific organizational rules, cultures, and evaluation criteria. Some general metrics include accuracy, currency, credibility, and value to the organization.

1.2. Create — A knowledge request may trigger the need for new knowledge assets to be created if none are found through searching during the identify stage. New knowledge assets may also need to be created if existing knowledge assets only partially satisfy knowledge needs. Some common organizational initiatives that assist in the creation of new knowledge assets include expert interviewing, prototyping, information and workflow analysis, and competence and process mapping. An example of technology that can be used in this phase is idea management software.