Stan Garfield's Blog, page 18

February 10, 2023

The Five Cs of KM: Capture, Part 4 — Input

In Part 2 and Part 3 of this series, I discussed the types of content and information to capture as part of a knowledge management program. This fourth and final part covers input.

Capturing input involves getting feedback from the people you serve on the services you provide to them. This includes soliciting their recommendations for improvements and capturing their stories about how they use your services and the associated benefits.

FeedbackCapturing feedback is asking for suggestions on what your library or information center can do better and how to improve things. You should also provide a way to submit corrections. If there is incorrect information in a knowledge base, you want to know so you can correct it. If there is missing information in a repository, or there are resources not currently available in the library that would be useful, there should be a way of alerting you to this. And if your users have additional content and information they wish to supply, you should make it easy for them to do so.

A proven way to capture feedback is to use surveys. You can use one-time or periodic user surveys to determine user preferences, needs, and challenges and to determine how people view your library and its assets.

Surveys are essential tools to ensure that your library or information center meets the needs of the organization. You should also develop processes for soliciting ongoing suggestions and submitting change requests.

Implement a regular satisfaction survey to solicit feedback on how users perceive your library. Use this survey to stay in touch with how your users view the library, what they like, and what needs to be improved. This is particularly important over time as the expectations of your end-users change due to comfort with technology, and other (often generational) attributes.

RecommendationsEnabling the capture of user recommendations can increase the effectiveness of your library and lead to greater use of its assets. To enable users to easily find important content, add a button for each library asset with labels such as:

ValuableI reused thisI found this usefulAllow users to tag content with one or more of these attributes:

RecommendedGood exampleProven practiceLet your users click the buttons and add the tags to show which assets they downloaded, checked out, or referred to and that proved useful to them. This is similar to a like button, but it has a very specific meaning. This will allow people to search for and find content tagged with these attributes, with the most useful assets quickly surfacing.

Users often ask for content rating systems for one to five stars similar to the user ratings offered by sites such as Amazon, but that is ineffective when not at scale. The percentage of people who actually rate items on Amazon is small, but because there are so many total users, the number is large enough to matter.

The scale of the Internet is far greater than that of most organizations. Inside a company, the percentage of people who might actually rate a document is tiny. Therefore, the number of ratings given to any document in a repository may not be sufficient to yield useful results and will typically be either one or five.

Determining a star rating is hard. Users have to struggle with, “Is this three or four or five?” so they just avoid it. A simple question such as, “Were you able to reuse this document?” is easier to answer, similar to a like button. If you click a like button, you don’t have to think too hard about it. You either like it or not.

Avoid implementing content ratings within your organization. Here are three reasons:

The value of a document is unknown until after it has been downloaded and read. There is a lag between the time it is accessed and the time a rating can fairly be made, and the user may no longer be logged into the repository at the time the rating could be applied.Within an enterprise, the user identity is generally known. Thus, users may be unwilling to give a bad rating since they would become known to the document contributor and possibly suffer negative social consequences.The number of people who might actually rate any given site or document is too low to be statistically significant.StoriesStories are the ways people talk about how they have done something. There are stories about successes and stories about failures. There are stories that explain how to do something and stories used to help capture what people know before they depart from an organization.

As people retire or move on from jobs, most organizations want to be able to retain their knowledge for reuse after they leave. Capturing their stories could be through writing, audio recording, or video. Ask people to tell stories on community calls, in apprenticeships, and in recorded videos.

One type of input to prioritize is the success story. There are two types of success stories to capture. Stories that impart valuable lessons should be collected, stored, and promoted. Moreover, you should regularly request from your users stories that show the value of your library or information center — and then use them in your communications efforts.

When capturing library success stories, ask the following questions:

What challenges did you face?What library resources did you use?How did you use these resources to address these challenges?What was the outcome?What benefits did you realize from using the resources? (e.g., time saved, costs avoided, incremental revenue, problems avoided, increased customer satisfaction, accelerated delivery, innovation, process improvement, etc.)What benefits did you and your organization derive?Did anyone else benefit as well (e.g., a community)?What alternatives (instead of using the library resources) did you consider?Which alternatives did you try?If you did not use the library resources, how do you think the outcome would have been different?This concludes the initial series on The Five Cs of KM. Please register for next week’s webinar on the first C: Capture, where I will present on the topics covered in this series. And get ready for the next series of blog posts where I will discuss the second C: Curate.

[image error]

[image error]

February 3, 2023

The Five Cs of KM: Capture, Part 3 — Information

In Part 2 of this series, I discussed the types of content to capture as part of a knowledge management program. This part covers capturing information.

In addition to collecting documents, knowledge capture also includes making entries into databases. Examples of this information include personal profiles, repositories, and knowledge bases. Following are details of each type and how to capture it.

Personal ProfilesThe personal profile is a way of capturing information about people and their skills. It allows people to enter information about who they are; their location; what they know, and what they can do. A personal profile aggregates an individual’s contributions to libraries, databases, and repositories; their social media posts; and their other activities to make all of this available on a single page specific to that person. Use personal profiles for locating experts, helping staff projects by finding the right people with the right skills and backgrounds, and providing a place to learn about each member of a social network.

Information entered in a skills database can include technical knowledge, process expertise, work experience, languages spoken, roles performed, customer and industry experience, community membership, professional organizations, publications, certifications, and so forth. The more details collected, the more searchable it is, but at the cost of complexity — and possibly annoying the users who must rate themselves on a multitude of categories.

The challenge with skills databases is getting employees to enter and maintain their personal data. Even with mandates from top management to do so, many people do not enjoy this task. As a result, they enter minimal information and don’t keep it updated as they develop new skills.

Social software can help address the difficulty of motivating employees to maintain their expertise in a tool. By allowing users to define their own tags for both interests and skills, a folksonomy of expertise is developed, which is less onerous than a massive list of standard skills. If a social networking tool offers other desirable features such as photos, personalized information, and friends, it may draw in users who will also enter and maintain their skills.

RepositoriesRepositories are structured lists, databases, and collections that allow information to be stored, searched for, and retrieved. A knowledge capture process requires a place to store what is collected. A repository is such a place, designed for ease of use when storing and retrieving information. It can take the form of a database, a list within a tool such as Microsoft SharePoint, or a collection of files within an intranet site, team space, or portal.

When creating a knowledge repository, decide on what type of content to capture. Plan for storage capacity that will remain adequate even as the number of collected files increases dramatically. Define the metadata required for each submitted file. Decide on a structure: hierarchical folders, different list views, faceted taxonomy navigation, or metadata-based search. Specify a contribution process. Ensure that search is properly integrated so that contributions can be found. Consider publishing the list of the latest submissions, providing alerts for posted material, and otherwise highlighting new submissions to make users aware of them.

Examples of repositories include project databases that capture key information on all projects, reference databases that include details on all reference materials, and asset collections with cataloged assets such as books, art, and music held in a library or museum.

In addition to providing a way for users to browse and search to find content, repositories are also useful in conjunction with threaded discussions. When a community member asks if a specific type of content is available, another member can reply with links to instances within existing repositories. This is an example of combining collection with connection; content has been collected and stored in a repository, and connections between people are made so they can take advantage of that content at the time of need.

An example of a project database is Hewlett-Packard’s Project Profile Repository, in which an individual record was captured for every project. The information collected included details on work performed and the team that delivered the project. This answered the question, “Where have we done this kind of work before?” which arises frequently in any kind of project-based organization.

If you have a database such as the Project Profile Repository where all previous work has been cataloged, you can easily search by any project attribute. You can identify people who worked on the project, contact them to learn more about it, and apply that knowledge to a new, similar effort.

Knowledge BasesA knowledge base is typically used to store answers to questions or solutions to problems enabling rapid search, retrieval, and reuse by reference librarians, information specialists, help desk personnel, or directly by those needing support. Examples of knowledge bases include customer support applications that capture problem resolutions, proposal generators that use an archive of proposals to help create new ones, and presentation builders that use a library of slides to generate custom slide decks.

The information stored in a knowledge base is captured in several ways. It can be seeded with authoritative articles written by recognized experts. This content can then be supplemented by reference librarians or help desk personnel as they respond to queries and requests. Once they have fulfilled a request or solved a problem, they enter information into the knowledge base so it can be reused the next time a similar need arises. In some cases, knowledge bases may be opened up to end users so they can add their own solutions and suggestions, thus helping each other directly.

In Part 4 of this series, I will discuss the types of input to capture as part of a knowledge management program.

The Five Cs of KM[image error]

The Five Cs of KM[image error]

January 27, 2023

The Five Cs of KM: Capture, Part 2 — Content

In Part 1 of this series, I introduced Capture as part of a knowledge management program. This part covers capturing content.

The kinds of content typically captured are documents, communications, and training. Following are details on each type and how to capture it.

DocumentsA document is the electronic equivalent of a piece of paper printed with text and graphics. It typically contains written information and may also include images.

Customer documents, ones that are used for or relate to clients, include brochures, specifications, product descriptions, proposals, presentations, case studies, and testimonials. Some of these documents are used in general marketing to prospects and some are used to sell specific solutions to individual customers.

Some customer documents are created for marketing campaigns, and some are created as part of sales efforts. The latest versions of brochures, specifications, and product descriptions should be stored in a library of marketing materials and updated whenever they are revised. Proposals and presentations should be captured at the end of the sales cycle, cleansed of customer-specific information, and stored in a sales database. Case studies and testimonials should be captured after wins and stored in a case study collection.

Internal documents, ones that are used inside organizations, include documentation on processes, procedures, and policies; meeting minutes and notes; and various reports and plans. Some of these documents apply to the entire organization, and some are specific to individual business units or teams.

The latest versions of standard processes, procedures, and policies should be stored in authoritative libraries and updated whenever they are revised. Meeting minutes and notes should be captured in collaborative team spaces, with access provided to all interested parties. Reports and plans should be published on the intranet so they can be referred to as needed.

Publications, documents that are formally published, include handbooks, guides, and other books; articles, essays, and periodicals; and lessons learned and proven practices. Some of these are in electronic form and some are physical hardcopies.

Electronic handbooks, guides, articles, essays, and periodicals should be posted to an online library. Lessons learned and proven practices should be published in specialized databases. Physical assets such as books should be made available in the corporate library or information center.

CommunicationsCommunications are vehicles for conveying ideas and information to other people. They can be transmitted in writing, sound, image, or video.

Written communications, consisting of words, include announcements, communiqués, and newsletters. Typically, these are mailed out to all recipients on a distribution list, and can be electronic, hardcopy, or both.

Announcements, communiqués, and newsletters should be stored in an internal blog. This allows them to be easily found by date or through search.

Blogs are websites where posts are made (such as entries in a journal or diary), displayed in a reverse chronological order, providing commentary or news on a particular subject. Some function as personal online diaries or logbooks. Blogs combine text, images, and links to other blogs and websites. They typically provide archives in calendar form, local search, syndication feeds, reader comment posting, trackback links from other blogs, blogroll links to other recommended blogs, and categories of posts tagged for retrieval by topic.

For knowledge management, blogs are good tools for communication and personal knowledge management. As a communications tool, they are available online, can be easily searched, and can be syndicated and subscribed to using RSS (Really Simple Syndication) or other feeds. For personal knowledge management, blogs offer a way of keeping a journal of insights, techniques, pointers, and contacts. They are the modern version of lab notebooks, easily shared with others to allow them to take advantage of what the blogger has recorded.

Blogs can eliminate the need for websites and newsletters, which may be costlier to maintain. Individual departments can produce their own blogs, which could feature a photo of the department manager and link to the organization chart. News items can be entered as blog posts, and subscriptions can be offered as RSS feeds. As a result, separate website maintainers and newsletter editors may no longer be needed.

Subscription management systems are tools that allow content providers to reach subscribers on an opt-in basis, and subscribers to sign up to receive periodicals and other communications based on their interests. There is still a need for allowing people to subscribe to traditional newsletters.

Newsletters are periodicals sent to subscribers interested in specific topics. They can be used to regularly capture and provide updates, stories, and useful content to interested parties.

Here are guidelines for creating newsletters: If your newsletter contains multiple topic categories, try to include only one story per category in each issue. Keep each story short and sweet. Link to longer articles, posts, and discussion threads. Avoid attachments. Post any necessary files to an easily accessible site and include links. Leave out boring announcements and predictable leadership messages. Include reminders of upcoming events and recaps of previous events.

Audio communications, consisting of sounds, include conference calls, podcasts, and recordings. These are typically listened to online or through syndicated subscription.

Conference call recordings and transcripts should be posted in a database. Podcasts should be stored on a website and made available via subscription in a similar fashion as Apple podcasts. Other recordings should be stored in a library and tagged for easy retrieval.

Podcasts are recorded broadcasts that can be listened to online, or downloaded manually or automatically through syndication and then listened to on mobile devices at the listener’s convenience. Podcasts are available on demand or by subscription. Use podcasts for those who prefer audio, like to listen while performing other tasks, or who aren’t connected to the network and subscribe for automatic downloads of the broadcasts through syndication.

Podcasts can be delivered through several channels. An audio file in MP3 format can be posted for online listening. Syndicated subscriptions can be offered to allow automatic downloading to mobile devices. Transcripts can be posted for those who prefer reading to listening.

Visual communications, consisting of sights, include videos, photos, and images of all kinds. These are typically viewed online or reused through an image library.

Videos are recordings or live telecasts that be viewed online or downloaded for later viewing on mobile devices. Videos are available on demand or by subscription. Use videos for those who prefer video, when there is important visual content, or for instructing or explaining.

Videos should be stored in a library modeled after YouTube. Photos and images should be stored in an image library.

TrainingTraining is a means of educating people about a specific topic. This can be done in person or online, in real time (synchronously) or on demand (asynchronously), and self-paced or with an instructor.

Courses are formal classes that can be conducted in person or virtually. They are typically long in duration, over multiple sessions ,and include instruction, assignments, and tests. They can be held live or pre-recorded and made available to view whenever convenient for the student.

Courses should be published in an e-learning system. They should be searchable by topic, date, instructor, language, and duration.

Tutorials are short-form instruction, typically in the form of videos. They can be searched for and consulted as needed to address a specific requirement.

Tutorials should be stored in a library modeled after YouTube. They should be tagged with all appropriate keywords.

Webinars are live, online educational presentations during which participating viewers can submit questions and comments. They may include slide presentations, video, chat, whiteboards, and polls. They can be recorded and made available later for people who missed the live version.

Webinars should be stored in a library. They should be searchable by topic, date, presenter, language, and duration.

In Part 3 of this series, I will discuss the types of information to capture as part of a knowledge management program.

[image error]

[image error]

January 24, 2023

Chun Wei Choo: Profiles in Knowledge

This is the 87th article in the Profiles in Knowledge series featuring thought leaders in knowledge management. Chun Wei is Professor in the Faculty of Information (iSchool) at the University of Toronto. He has a Ph.D. in Information Studies from the University of Toronto, a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Engineering from the University of Cambridge (UK) (where he was at Christ’s College), and a Master’s degree in Information Systems from the London School of Economics and Political Science (Dept of Management).

His main research interests are information and knowledge management, information behavior, environmental scanning, organizational learning, organizational epistemology, and early warning. In 2022, he received an honorary doctorate from Tampere University, Finland, for his contribution to the study of “the relationship between information science and knowledge management.” In 2021, he received the ASIS&T Research in Information Science Award for his “outstanding contribution to information science research.”

Background

Chun Wei has supervised PhD students in areas such as organizational use of Web information systems, knowledge discovery in Web use databases, information behavior of healthcare providers, health information seeking on the Web, a knowledge-based view of the firm, the public library as knowing organization, customer knowledge management, and group information culture in the use of collaborative information systems. In 2016, he received the JJ Berry Smith Doctoral Supervision Award for “outstanding performance in the multiple roles associated with doctoral supervision.”

Chun Wei’s articles and papers have appeared in the Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, Financial Times of London, First Monday, Information Processing and Management, Information Research, International Journal of Information Management, Journal of Documentation, Journal of Information Science, Journal of the Association for Information Science & Technology, Journal of Knowledge Management, Library and Information Science Research, Library Management, Management Decision, National Post of Canada, Sloan Management Review, Tijdschrift Management & Informatie, and Wirtschafts Woche. Chun Wei’s articles and books have been translated and published in Dutch, French, German, Korean, Portuguese and Spanish.

Chun Wei has worked on research projects with a number of organizations, including Bell Canada, Canadian Human Resource Planners, Clarica, Enbridge, Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN, Human Resource Development Canada, Toronto Hospital for Sick Children Research Institute, Ontario Legislative Assembly, Ontario Power Generation, and Royal Bank Canada Capital Markets.

Before moving to Canada, Chun Wei was Director of Planning at Singapore’s National Computer Board (now Government Technology Agency of Singapore), and Manager, Research Planning of the Board’s Information Technology Institute (now Institute for Infocomm Research). Earlier, he was Head Office Systems Group and Head Research Department in the Ministry of Defense.

EducationPhD, Faculty of Information Studies, University of Toronto, 1989–1993MSc, Master’s Program in the Analysis, Design and Management of Information Systems, London School of Economics & Political Science, University of London, UK, 1983–1984Postgraduate Diploma in Business Administration, National University of Singapore, Singapore, 1982–83Postgraduate Diploma in Computer Science, National University of Singapore, Singapore, 1977–78MA, Engineering, University of Cambridge, UK, 1977BA, Engineering, University of Cambridge, UK, 1972–75Experience2003-present, Professor, Faculty of Information, University of Toronto1998–2003, Associate Professor, Faculty of Information Studies, University of Toronto1993–1998, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Information Studies, University of Toronto1989, Director, Planning Department, National Computer Board of Singapore1987–1989, Deputy Director (IT Planning), Planning Department, National Computer Board of Singapore1986–1989, Manager (Research Planning), IT Institute, Singapore1985–1986, Senior Systems Analyst/Project Leader, Information Systems Department, Ministry of National Development, Singapore1981–1983, Head, Office Systems Group, Systems & Computers Organization, Ministry of Defense, Singapore1977–1981, Head, Research Department, General Staff Division, Ministry of Defense, SingaporeProfilesPersonal SiteCVFaculty of Information (iSchool) — University of TorontoContentGoogle ScholarResearchGateOrcidSemantic ScholarAcademia.eduResearch.comdblpACMArticles and PapersThe strength of trust over ties: Investigating the relationships between trustworthiness and tie-strength in effective knowledge sharing. Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management [PDF]

Organizational knowledge sharing and trust networks should be analyzed by conducting a social network analysis. If the sociogram reveals too many strong ties (i.e., high closure or density), it may be prudent to add non-redundant weak ties. Possible techniques include moving employees with similar expertise across projects, departments, or divisions. This encourages individuals to transfer their knowledge outside of their immediate closed network. Holding casual and informal “all-hands” social events may create similar effects, with less commitment and risk. On the other hand, a network with too many weak ties may be strengthened by facilitating resource pooling, coordination, and project work between and across weakly tied co-workers.

The Effect of Knowledge Management Context on Knowledge Management Practices: An Empirical Investigation. Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management [PDF]

The results of our survey illustrate that both organizational and personal information behaviors are influenced by the corporate wide knowledge management environment comprising the practices, policies and processes institutionalized and the technologies implemented for KM initiatives. Subsequently, personal information behaviors are also influenced by organizational information behaviors suggesting that an individual’s own behavior towards information and knowledge sharing is influenced by his/her perceptions of others’ commitments and tendencies towards knowledge sharing. Furthermore, our research shows that specific career based demographic variables also impact the relationship between a firm’s KM environment and information behaviors at both organizational and individual levels. Specifically, males, older employees, and those with professional designations (as opposed to support roles) have a positive perception of and attitude towards the corporate KM context and organizational level KM practices.

The findings in this paper have both practical as well as theoretical implications. From a practical standpoint, the results of our survey compel businesses, especially those that regard themselves as “knowledge intensive” organizations to acknowledge, explore and positively influence the people-factors that are critical to task performance and organizational success through various material as well as relational means. Firstly, as an overarching approach, organizations need to promote knowledge sharing processes among employees through the establishment of formal policies and procedures and the implementation of requisite technology infrastructures. As shown in our research results, such formalized practices not only lead to positive perceptions about the knowledge environment and organizational information behaviors but also enhance personal information behaviors. Additionally, the organizational information behaviors construct emphasizes the importance of pooled expertise, relationships, and alliances to the progress of KM initiatives, hence suggesting that in their efforts to further harness the knowledge-based capabilities of their human capital, managers should undertake the development of various incentives for their employees to work collaboratively and share their knowledge with one another.

The Individual and Social Dynamics of Knowledge Sharing — An Exploratory Study. Journal of Documentation [PDF]

A unique feature of this study is in comparing sharing behavior with different sharing targets. Results showed that individuals were significantly more likely to share knowledge with their superior than with a close colleague or a distant colleague. No significant difference in propensity was found between sharing knowledge with a close colleague and a distant colleague.

An overarching theme of this study has been that knowledge sharing is volitional and cannot be forced or mandated. (While organizations may decree that employees share their knowledge, reluctant employees have always found ways to circumvent or undermine the spirit of such directives.) We discovered that individual perceptions about costs and benefits, personal preferences about the distribution of sharing outcomes, and the structural relationship of knowledge recipients, all have effects on knowledge sharing behavior.

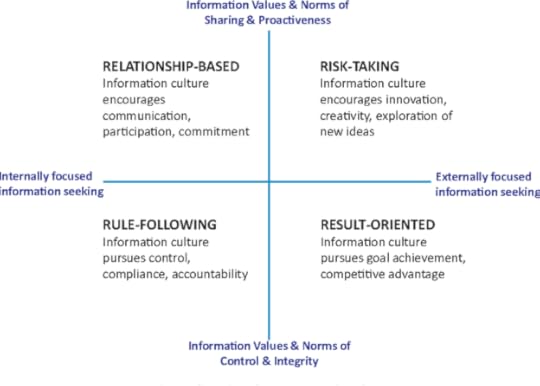

Information Culture and Organizational Effectiveness. International Journal of Information Management [PDF]

Information Cultures: A Proposed Typology

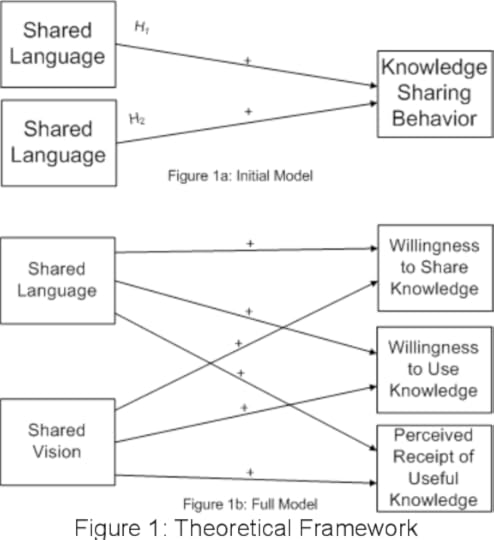

Information Cultures: A Proposed TypologyHow Shared Language and Shared Vision Motivate Effective Knowledge Sharing Behavior. 13th European Conference on Knowledge Management [PDF]

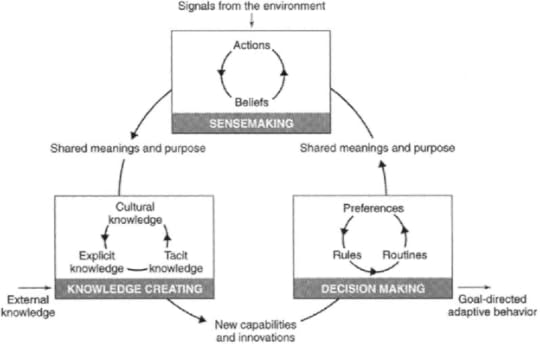

Sensemaking, Knowledge Creation, and Decision Making: Organizational Knowing as Emergent Strategy. Strategic Management of Intellectual Capital and Organizational Knowledge [PDF]

The Organizational Knowing Cycle

The Organizational Knowing CyclePerspectives on Managing Knowledge in Organizations. Cataloguing and Classification Quarterly 37 (1/2: Special Issue on Knowledge Organization and Classification in International Information Retrieval) [PDF]

Any organization that wants to excel at managing knowledge will need to perform three KM processes well: generation, codification, and transfer of knowledge.

Knowledge generation refers to activities that increase the stock of organizational knowledge. Five modes of knowledge generation are discussed: acquisition; dedicating resources; fusion; adaptation; and building knowledge networks. Organizations may acquire knowledge by hiring individuals, buying another organization, or renting/leasing external knowledge. They may also dedicate resources to the generation of knowledge by establishing units that undertake research and development. The authors note that some corporate libraries function like R&D departments, developing and providing new knowledge to the organization. Knowledge generation through fusion can occur when different individuals and groups with different specializations and perspectives are brought together to work on a problem or project. Adaptation takes place when the organization responds to new conditions in its external environment. Here, knowledge generation is a result of organizations adapting to significant competitive, economic, or technological changes; and the most important adaptive resources are employees who can acquire new knowledge quickly and who have the openness to learn new skills. Knowledge is also generated in networks of people in an organization who share common work interests, face common work problems, and are motivated to exchange their knowledge. Organizations may attempt to formalize these informal, self-organizing networks over time.

Knowledge codification. Tom Davenport and Larry Prusak offer four principles that should guide the codification of organizational knowledge.

Managers must decide what business goals the codified knowledge will serve.Managers must be able to identify knowledge existing in various forms appropriate to reaching these goals.Knowledge managers must evaluate knowledge for usefulness and appropriateness for codification.Codifiers must identify an appropriate medium for codification and distribution.Codification of tacit knowledge is generally limited to locating someone with the knowledge, pointing the seeker to it, and encouraging them to interact. For example, a knowledge map (an actual map, a Yellow Pages, a directory database) can be constructed to point to knowledge but does not contain it. Trying to turn knowledge into a “code” can sometimes seem to defeat the purpose of communicating it. The challenge is to codify knowledge and still leave its distinctive attributes intact, putting in place codification structures that can change as rapidly and flexibly as the knowledge itself. Davenport and Prusak suggest that stories, in their ability to embody and extend experience, and to combine feeling and thought, may be a way of capturing knowledge without removing its richness.

Knowledge transfer. Since organizations behave as knowledge markets, they should create market spaces and places where this trading and sharing of knowledge can happen. Much of knowledge transfer occurs through personal conversations, so places such as water coolers, talk rooms, knowledge fairs, and open forums become important venues for sharing information. A major theme in Davenport and Prusak’s discussion is that the sharing of knowledge between people and groups in an organization may be the most daunting task in knowledge management. Most of the impediments are related to the culture of the organization. Davenport and Prusak identify seven barriers: lack of trust; different cultures, vocabularies, and frames of reference; lack of time and meeting places; status and rewards going to knowledge owners; lack of absorptive capacity in recipients; belief that knowledge is the prerogative of particular groups; the “not-invented-here” syndrome; and intolerance for mistakes or need for help.

Davenport and Prusak distinguish between formal and informal knowledge transfer and point out that: “Informal knowledge transfer is endangered by a particularly American sense of what is and isn’t “real” work. … an employee who reads a book at his desk — arguably an effective approach to knowledge acquisition — is looked at with suspicion. … A company that claims to value knowledge but discourages reading and talking on company time sends mixed messages. The more convincing message is that knowledge is not much valued after all. Managers need to recognize that the availability of “slack” time for learning and thinking may be one of the best metrics of a firm’s knowledge orientation.

Articles by OthersChun Wei Choo wins 2021 Research in Information Science AwardASIS&T 2021 Research in Information Science Award — Association for Information Science and TechnologySense-Making by Mary Lee KennedyChun Wei Choo has looked at sense-making in the context of his explorations on “knowing organizations”. He sees sense-making as part of three broad activities that are interrelated, and which are done well in “knowing organizations”. So rather than it being only an individual action, Chun Wei Choo’s work looks it in the context of what organizations and individuals do. The three broad interrelated activities are sense-making, knowledge-creating, and decision-making.

Sense-making is related to the management of ambiguity; knowledge-creating is related to the management of learning, and decision-making is related to the management of uncertainty. Each one of these form three points on the triangle (the apexes) and the gap between sensing and knowing, sensing and doing, and knowing and doing is addressed through other sets of activities. At the individual level, he distinguishes between sensing (noticing potentially important messages in the environment) and making sense (constructing meaning from what has been sensed) as critical to organizations today. His book, “The Knowing Organization”, presents a review of many studies on organizational sense making (March and Olsen, Starbuck and Milleken, Thomas, Clark and Gioia, and of course Weick and Dervin).

Choo discusses Dervin’s work (which is both theoretical and empirically based) as a model analyzing information seeking and use in terms of a triangle of “situation-gap-use” reflected in three questions:

What in your situation is stopping you from moving forward?What questions or confusions do you have?What kind of help do you hope to get?30 Knowledge Management InsightsIn Sensemaking, Knowledge Creation, and Decision Making: Organizational Knowing as Emergent Strategy, Chun Wei Choo lists three kinds of knowledge:

Tacit knowledge in the expertise and experience of individualsExplicit or rule-based knowledge in artifacts, rules and routinesCultural knowledge in the assumptions and beliefs used by members to assign value and significance to new information or knowledgeThree kinds of knowledge creation:

Knowledge conversion: the organization continuously creates new knowledge by converting between the personal, tacit knowledge of individuals who develop creative insight, and the shared, explicit knowledge by which the organization develops new products and innovations.Knowledge integration: the result of the organization’s ability to coordinate and integrate the knowledge of many individual specialists.Knowledge transfer: across organizational boundaries; can involve tacit, explicit, and cultural knowledge to varying degrees.And four modes of organizational decision making:

Boundedly rational mode: goal and procedural clarity are both high, choice is guided by performance programsPolitical mode: contested by interest groups, but procedural certainty is high within the groups; each group believes that its preferred alternative is best for the organizationAnarchic mode: goal and procedural uncertainty are both high; decision situations consist of relatively independent streams of problems, solutions, participants, and choice opportunities arriving and leaving; a decision then happens when problems, solutions, participants, and choices coincideProcess mode: goals are clear but the methods to attain them are not; decision making becomes a process divided into three phases:Identification: recognizes the need for decision and develops an understanding of the decision issuesDevelopment: activates search and design routines to develop one or more solutions to address a problem, crisis, or opportunitySelection: evaluates the alternatives and chooses a solution for commitment to actionGood KM Quotes by Kaye VivianKnowledge management is a framework for designing organizational goals, structures, and processes so that the organization can use what it knows to learn and to create value for its customers and community. — Chun Wei ChooBook Reviews

The Inquiring Organization by Martin White

I am constantly looking for answers to ‘why’ certain approaches to information management seem to work within some form of information culture. Then in 2013 I came across a paper on information culture and organizational effectiveness by Professor Chun Wei Choo of the University of Toronto. In this paper he described result, rule, relationship and risk taking cultures and their impact on organizational effectiveness, and I have used this model many times in the period since its publication.

…

Professor Choo’s book rewards careful reading, because the evidence he presents and the insights he gives will provide you with an invaluable set of lenses with which to view aspects of information and knowledge management. In much of his writing his initial training in engineering comes through, with a very grounded approach to the analysis of the case studies and a sure understanding of how organizations work. In many respects he presents a unifying theory of information and knowledge management, and I would suggest that the KM community would do well to consider what Professor Choo has to say. After all the root of the word ‘epistemology’ is the Greek word epistēmē, meaning “knowledge”. It may take you nine weeks to read and consider the nine chapters but at the end I am certain you will say to yourself “Now I understand”. The benefits to both you personally and to your organization will be significant and long lasting.

The inquiring organization by Elena Macevičiūtė

The amount of intellectual effort put into the book is remarkable. The reference lists at the end of many books may be quite extensive, but in this particular case each entry has been scrutinized, deeply read and, in many cases, filtered through empirical research done by the author, even when an empirical investigation itself is not visible in this particular text. The directions of further research on information in organizations are not highlighted as part of conclusions, but rather prompted in multiple pages. I am quite sure that many young and senior researchers may find a way out of a creative block that many of us run into from time to time or a brilliant idea for a project while reading this monograph.

Information management for the intelligent organization by Elena Macevičiūtė

His book remains one of the most comprehensive and enlightening texts on information management.

The knowing organization by Tom Wilson

This new edition of a deservedly popular text is welcome and will be of considerable value to students seeking to understand how information is put to use in organizations: if they retain a skeptical view of the concept of ‘organizational learning’, they may even learn more.

Managing information for the competitive edge by Tom Wilson

I find the collection as a whole very useful — and it would be an incredible feat on the part of any editor to satisfy every reader. There is much here that the student of information management will find of value: the papers by Taylor (information use environments), Daft and Lengel (information richness), Ellis and others (information audits), Davenport, Eccles and Prusak (information politics) and Koenig (information and productivity), among others are all worth being brought together in this way. The book is intended for practitioners, teachers and students, but I suspect that the main audience was intended to be the academic. Practitioners, however, could certainly benefit from many of the papers presented here, which may offer an alternative perspective from that conveyed by the dominant paradigm of information handling under which they might have received their early training.

Books

The Strategic Management of Intellectual Capital and Organizational Knowledge: A Collection of Readings edited with Nick Bontis

Web Work: Information Seeking and Knowledge Work on the World Wide Web with Brian Detlor and Don Turnbull

The Inquiring Organization: How Organizations Acquire Knowledge and Seek Information

Managing Information for the Competitive Edge edited with Ethel Auster

Book Chapters (selected)The Effects of Enterprise Portals on Knowledge Management Projects in

Encyclopedia of Portal Technologies and Applications

[PDF]Knowledge Management in Encyclopedia of Communication and Information [PDF]Perspectives on Managing Knowledge in Organizations in Knowledge Organization and Classification in International Information Retrieval [PDF]Knowledge, Intellectual Capital, and Strategy: Themes and Tensions in

Strategic Management of Intellectual Capital and Organizational Knowledge

[PDF]Environmental Scanning as Information Seeking and Organizational Learning in Introducing Information Management: An Information Research Reader [PDF][image error]

Book Chapters (selected)The Effects of Enterprise Portals on Knowledge Management Projects in

Encyclopedia of Portal Technologies and Applications

[PDF]Knowledge Management in Encyclopedia of Communication and Information [PDF]Perspectives on Managing Knowledge in Organizations in Knowledge Organization and Classification in International Information Retrieval [PDF]Knowledge, Intellectual Capital, and Strategy: Themes and Tensions in

Strategic Management of Intellectual Capital and Organizational Knowledge

[PDF]Environmental Scanning as Information Seeking and Organizational Learning in Introducing Information Management: An Information Research Reader [PDF][image error]

January 20, 2023

The Five Cs of KM: Capture, Part 1 — Basics

This post is the first in a series about knowledge management in special libraries and information centers, structured around Five Cs: Capture, Curate, Connect, Collaborate, and Create. There will be four posts for each of the Five Cs. This four-part series is about the first C: Capture.

Knowledge capture includes collecting documents, presentations, spreadsheets, records, processes, software source code, images, audio, video, and other files that can be used for innovation, reuse, and learning. Gartner defines knowledge capture as “one of the five activities of the knowledge management process framework. Knowledge capture makes tacit knowledge explicit, i.e., it turns knowledge that is resident in the mind of the individual into an explicit representation available to the enterprise.”

Dave Snowden has famously asserted, “If you ask (people) to give you your knowledge on the basis that you may need it in the future, then you will never receive it.” This suggests that it is difficult to capture knowledge. And even if you do capture it, there is no guarantee that it will be reused.

Many knowledge management (KM) programs emphasize capture too much — collecting lots of documents, but not being able to effectively reuse them. It is reasonable to question the value of devoting significant energy to document collection in advance of a need.

Taking these caveats into consideration, it is nonetheless useful to establish processes for capturing knowledge for later reuse. As long as you avoid getting carried away with attempting to capture all documents, a capture process can be helpful in providing a supply of reusable content. There is still value in capturing some information in easily retrievable repositories.

An example of a capture process is storing information on every project undertaken by an organization in a project repository. This allows members of the organization to search the database to find out if there is knowledge from previous projects that can be applied to new ones.

This can be used in multiple ways. Sometimes you need to answer the question, “Have you ever done this before?” when proposing a new project. Or you want to review lessons learned from prior work. Reusing documents such as proposals, statements of work, project plans, and designs is another benefit of knowledge capture.

Not all of the documents created by previous projects may have been captured, but if the names of the project team members are available, then it is possible to contact them to request other relevant documents. And it can be helpful to discuss their experiences, insights, and suggestions before embarking on similar efforts.

A project repository can have a simple entry form for information about the project. It might include the project name, a unique identifier, department, dates, location, solution, a brief description of the project, and a list of the team members. This may be all the information that is required, with the option to associate other documents that are project related.

Another example is a white paper capture process for tips, rules of thumb, insights, or nuggets of knowledge. These can be categorized by subject, and people can subscribe to and read the white papers based on their interests. If someone has solved a particular problem or has come up with a concept other people might benefit from knowing, a capture process for easily publishing their knowledge can lead to sharing and reuse.

Without such a process, those who are known for their good ideas may be repeatedly contacted by others seeking the benefit of their experience and expertise. After the sixth time of explaining the same information over again, those being contacted will appreciate a way to capture that information so it is in one place for everybody to access.

Collection and SupplyCapturing explicit knowledge requires collection processes and repositories, which involve attempting to codify and encapsulate knowledge in writing or some other form of stored data. Explicit knowledge is formal knowledge that can be conveyed from one person to another in systematic ways. Examples include books, documents, white papers, databases, policy manuals, email messages, spreadsheets, methodologies, multimedia, and other types of files.

Collection provides the supply side of knowledge. There must be a supply of knowledge in order for it to be reused. Supply-side knowledge management includes collecting documents and files, capturing information and work products, and storing these forms of explicit knowledge in repositories. Tacit knowledge can also be captured and converted to explicit knowledge by recording conversations and presentations, writing down what people do and say, and collecting stories.

Examples of supply include project repositories, skills inventories, and document libraries. The captured content represents the raw materials. These can then be analyzed, codified, disseminated, queried, searched for, retrieved, and reused.

Even if every possible document and knowledge object is captured and stored, there is no resultant benefit unless there is significant reuse of all that content. Be sure to keep supply and demand approaches in balance.

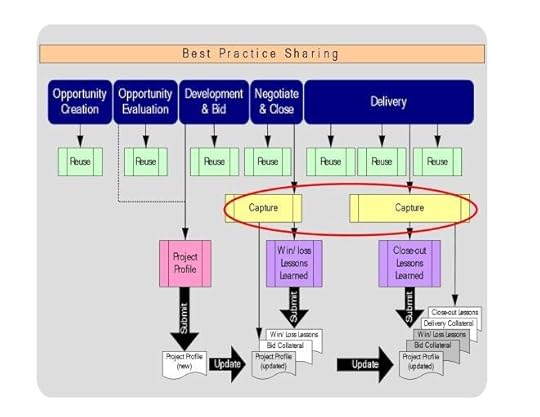

ExampleOne of the three goals in the HP Engagement Knowledge Management program was capture, which meant capturing the content and experience from customer bids and projects. This included such things as project summaries, lessons learned, proven practices, white papers, bid documents, and project deliverables.

The formal goal was: Capture content and experience from all customer bids and projects (project profiles, lessons learned reports, bid/project documents, solution collateral/service kit content, knowledge briefs). It was measured by the number of new project profiles in the Project Profile Repository, divided by the number of new projects.

To help achieve the goal, HP embedded knowledge capture into the customer engagement process. The HP Customer Engagement Road Map was the required process to follow from opportunity creation to delivery. It was the basis of the Engagement Knowledge Map on the HP Knowledge Network homepage. It displayed a grid of steps and resources necessary to carry out a client engagement.

Across the top of the grid were five categories: opportunity creation, opportunity evaluation, development & bid, negotiate & close, and delivery. People followed the roadmap because it was integrated into the process.

The HP Knowledge Capture & Reuse Process

The HP Knowledge Capture & Reuse ProcessKnowledge Capture & Reuse was an official process and policy that specified when knowledge was to be captured and reused. Project Startup included the required submission of a project profile to the Project Profile Repository. The Project Closeout process included a requirement to capture project lessons learned.

Initially, there was a problem with capturing project profiles. The quality of the information submitted was often poor, with missing or inaccurate data. HP assigned the people who supported the knowledge help desk an additional task: review all project profile submissions and approve only those that met a minimum quality test. Those submissions that failed this test were followed up to ensure good data. HP measured and reported on the quality, and after a year, the quality was nearly 100% and the process was working perfectly.

—

Capture involves collecting explicit knowledge, including content such as documents, information such as entries into databases, and input such as feedback from users about what they want and what they need. In Part 2 of this series, I will discuss the types of content to capture as part of a knowledge management program.

[image error]January 13, 2023

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 34: Mary Lee Kennedy

Mary Lee Kennedy is the Executive Director of the Association of Research Libraries (ARL). ARL represents 124 institutional members drawn from libraries and archives in major public and private universities, federal government agencies, and large public institutions in Canada and the USA. ARL’s mission is to advance research, learning, and scholarly communication by fostering the open exchange of ideas and expertise, promoting equity and diversity, pursuing advocacy and public policy efforts, forging partnerships, and catalyzing collective efforts.

Mary Lee managed the Corporate Library Group at Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) while I was leading DEC’s knowledge management program. At Microsoft, she led a global team in the design and implementation of knowledge and information strategies that served all Microsoft employees and supported internal pilots for enterprise products. Mary Lee developed Microsoft’s intranet portal and collaboration solution to connect employees with internal and external knowledge and information. She achieved significant advances in market analysis, competitive intelligence, research and product information management, and internal communications.

EducationLouisiana State University, Master of Library ScienceUniversity of Alberta, Bachelor of Arts in Social Psychology and ClassicsExperienceAssociation of Research Libraries (ARL), Executive Director, 2018-PresentNew York Public Library, Chief Library Officer, 2013–2016Harvard University, Senior Associate Provost for the Harvard Library, 2011–2013Harvard Business School, Executive Director, Knowledge and Library Services, 2004–2011Microsoft Corporation, Director, Knowledge Network Group, 1998–2004Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), Corporate Library Group Manager, 1995–1998Profiles Association of Research Libraries LinkedIn Twitter SaintOnge Alliance Association Of Knowledgework (AOK) Star Series Biography Profiles in Knowledge BooksIntranets for Info Pros edited with Jane Dysart

TIMAF Information Management Best Practices — Volume 1 edited by Bob Boiko and Erik Hartman — Chapter 1: Creating a Desired IM State: Understand, rationalize and take control of the state of information management in your organization — with Bob Boiko

The Emerald Handbook of Modern Information Management edited by James M. Matarazzo — Chapter 6: Leading and Managing Strategy in the 21st Century — with Rebecca Jones

Knowledge Management in Libraries and Organizations edited by Leda Bultrini, Sally McCallum, Wilda Newman, and Julien Sempere — Chapter 21: Knowledge Collaboration in Higher Education

Videos Keynote LIANZA Conference 2019 NYPL’s Library HotSpot Program Interview on Information Types Keynote Roundtable: The Future of Libraries “Perspectives” discussion: “The Past, Present, and Future of University and College Libraries Presentations Technology and Collaboration with Stephen Abram Leadership Roles for [Research] Libraries in the Fourth Industrial Revolution Conferences Dublin Core Conference 2003 Information TodayKnowledgeNets 2001 — Microsoft Case Study: Portals as Communities for Knowledge Sharing 2002 Workshop 1: Tying Information & Knowledge Together: Successful Strategies Session D103: Setting Context: Personas, Archetypes, and Organizational Engagement — Understanding User Requirements for the Enterprise Information Portal Intranet Professional’s Intranet Resources: CyberTour KMWorld & Intranets2003Preconference Workshop 2: Intranet Professionals AcademySession D301: Inside the Microsoft Intranet: Partnerships Across the Enterprise with Mark Davies2005Session B303: Sharing Critical Knowledge: Healthcare Lessons Session E102: Governance Do’s and Don’ts Session F101: Implementing New Technologies — Lessons on Adoption from the Field — with Deb WallaceComputers in Libraries Additional Links 2022 Powerful Thinking with Powerful Questions 2019 D102: The Courage to Be Strategic Change Models: Strategy Leadership and Management 2018 Change Management 2017 W11: Innovation for Significant Results Practitioners Panel: Strategies & Practices 2014 Keynote: Hacking Strategies for Library Innovation 2005 Delighting the Real User: Personas in Action The Gilbane Conference Boston 2012 Creating Information Environments that Generate New Knowledge: Is it Science Fiction or Time to Suspend Disbelief? San Francisco 2007 CM-1: Case Studies — Stretching the New SharePoint Boston Content Management Technologies 2004 CM-1: Planning for & Evaluating CMSes — How to Get StartedKM-2: Collaboration and Knowledge Management Best PracticesOther Content ResearchGate Emerging Technologies for Research and Learning: Interviews with Experts with Scout Calvert What Do Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Ethics of AI Mean in the Context of Research Libraries? Moving Beyond Open Access to Digital Fluency How to Future-Proof Your Library The NYPL at its best Supporting Researchers at NYPL: Today, Tomorrow & Beyond Innovation, Creativity and Meaning: Leading in the Information Age with Tomalee Doan The “t”, “i” and “e” in knowledge A new approach to conference learning with Deb Wallace The tangible and potential impact of research libraries Why Net Neutrality Matters and What Research Libraries Can Do about It Implementing Open Science Principles through Research Partnerships with Judy Ruttenberg The Opportunity for Research Libraries in 2018 and Beyond How Employees Shaped Strategy at the New York Public Library with Bruce A. Strong Curating Knowledge Under Digital Conditions: Transforming into a New Era Research Libraries as Catalytic Leaders in a Society in Constant Flux Building Blocks for Knowledge Management at Digital Equipment Corporation: The WebLibrary Sense-Making Change Models: Strategy Leadership and Management [image error]

[image error]

January 6, 2023

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 33: Joitske Hulsebosch

Joitske Hulsebosch is a consultant and facilitator working with Sibrenne Wagenaar in their Dutch company, Ennuonline.

Her specialties are designing and facilitating blended learning, choosing the right tools and platforms, setting up communities of practice and networks, continuous (knowmadic) learning in organizations, hybrid meetings, and digital innovation.

Always looking for new tools and platforms, Joitske tries out at least one new tool every month to come up with innovative applications for learning and knowledge sharing. She helps learning professionals evolve from classical to innovative learning, creating enthusiasm through positive experiences with new technology.

EducationWageningen University & Research: Master’s degree, Irrigation and soil & water conservation, 1984–1990Corderius College, Amersfoort: 1978–1984Profiles LinkedIn Twitter About me KM4Dev OEB Global Profiles in Knowledge BooksDesign Blended Learning: Everything You Need to Know About Tools, Design and Facilitating with Sibrenne Wagenaar (in Dutch) — English Blurb

En nu online …: Sociale media voor professionals, organisaties en trainers (Dutch) And now online …: Social media for professionals, organizations and trainers — with Sibrenne Wagenaar

Leren in tijden van tweets, apps en likes: de invloed van sociale technologie (Dutch) Learning in times of tweets, apps and likes: the influence of social technology — with Sibrenne Wagenaar

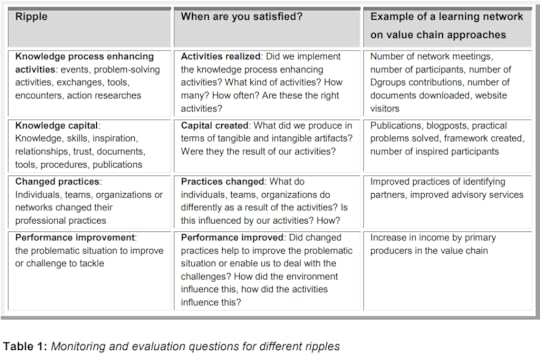

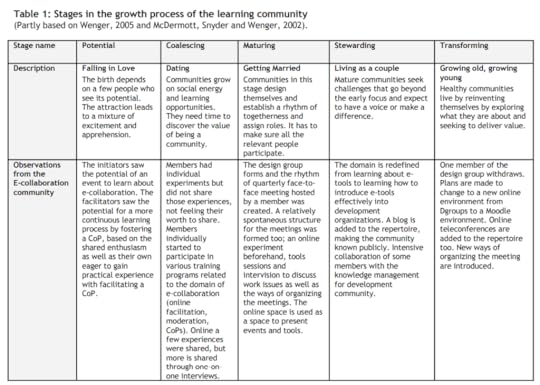

Other Content Site and Blog (Dutch) Company Site (Dutch) SlideShare YouTube LinkedIn Articles Linkedin Posts Academia Company Blog (Dutch) Blog Monitoring and Evaluating Knowledge Management Strategies with Mark Turpin and Sibrenne Wagenaar From a meeting to a learning community with Sibrenne Wagenaar

From a meeting to a learning community with Sibrenne Wagenaar Is introducing technology hard? Don’t blame the technophobes!

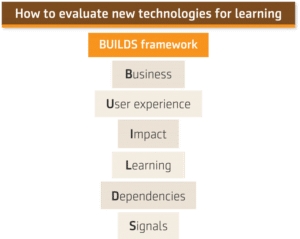

Is introducing technology hard? Don’t blame the technophobes!BUILDS- Watch the influence of the technology on the users

The plea of BUILDS is to answer the following questions much earlier in the process. This can be done through interviews, group discussions or workshops.

What new ways of learning and working does the technology offer? What does it offer the users? What will make them happy and what not?To what extent does the technology provide a user-friendly experience compared to what they also use and like privately?In which ways will users deploy the technology? What changes are necessary? It is great if you can observe what people are doing now so that you know the biggest changesDevelop one and preferably multiple use cases. What is the use case of a colleague? What are the different types of users?Can the users use the technology in their own way, does it offer this flexibility?How will you test and set up together with users? How do you keep collecting feedback to improve it?[image error]December 23, 2022

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 32: Mary Adams

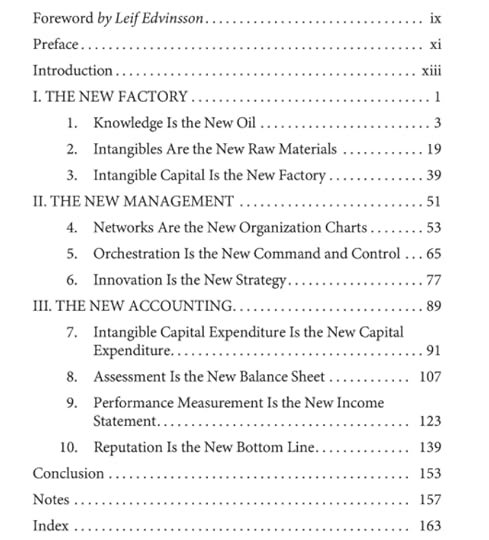

Mary Adams helps business leaders deliver sustainable corporate value through ESG (environmental, social, and governance) optimization. Based in Boston, she specializes in intangible capital, the multi-capital model, integrated thinking, and integrated management.

The focus of her work is bringing sustainability and long-term thinking into business decisions. Mary’s career started in high-risk finance and moved to entrepreneurship and strategy consulting. Her current work at Insights7 is building software that enables business leaders to literally connect the dots between profitability and sustainability. The rising pressure on companies to incorporate ESG factors into corporate reporting and management systems is an important impetus.

Mary supports two communities she helped create: The Exit Planning Exchange (XPX) that brings long-term thinking to the private company market, and the Integrated Reporting U.S. Community that brings long-term thinking to public companies.

Her career started in the world of hard assets and finance, with 15 years in high-risk lending at Citicorp and Sanwa. In 1999, Mary started a strategy consulting firm. As she helped clients adapt to changing markets and changing expectations, she saw firsthand how the financial models she had used as a banker were failing to capture the value being created (and destroyed) in the form of human, digital, natural, and relationship resources.

Mary is the co-author of Intangible Capital: Putting Knowledge to Work in the 21st Century Organization which outlined approaches she developed to support systems thinking, integrated value creation, and a multi-capital framework. This kind of approach is now gaining greater market acceptance thanks to the work of organizations like the integrated reporting and management movement under the umbrella of ISSB — the International Sustainability Standards Board, a movement she actively supports.

EducationRice University — BA, Political Science, 1977–1981Thunderbird School of Global Management — Masters, International Management, 1981–1982ExperienceCo-founder and CMO — Insights7, 2021 — PresentFounder — Smarter-Companies, 2013–2022Co-Founder — Trek Consulting LLC, 1999–2013Vice President — Sanwa Business Credit, 1990–1999Profiles LinkedIn Smarter Companies Twitter Facebook BooksIntangible Capital: Putting Knowledge to Work in the 21st-Century Organization with Michael Oleksak

Table of Contents

The Routledge Companion to Intellectual Capital edited by James Guthrie, John Dumay, Federica Ricceri, and Christian Nielsen — Chapter 23: Emerging Integrated Reporting Practices in the United States

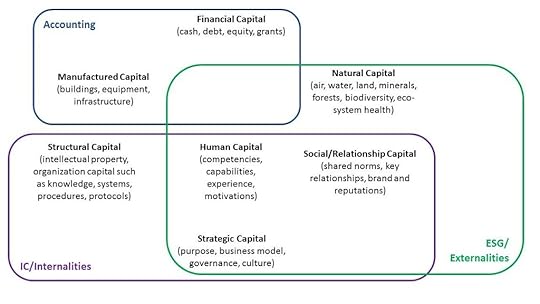

Leading Issues in Knowledge Management Volume 2 edited by Kenneth Grant and John Dumay — Chapter 2 with John Dumay: The Learning Journey of IC Missionaries: Intuition, control, and value Creation

Knowledge Management and Intellectual Capital Excellence Awards 2015: An Anthology of Case Histories edited by Dan Remeny — Chapter 1: Road Map to Growth and Exit: Jumpstarting Growth with IC

Flat World Navigation: Collaboration and Networking in the Global Digital Economy by Kim Chandler McDonald — Chapter 3: Demand and opportunity through business collaboration (interview)

PodcastHow to Increase Value with Intangible Capital

Videos YouTube Interview Smarter Companies Multi-Capital Model Presentations IT + IC = Innovation Risk in the Knowledge Era: Intangible. But Very Real Knowledge is the New Oil Accounting in the Knowledge Era Other Content Smarter Companies Insights7 LinkedIn Articles LinkedIn Posts BlogHow Intangible Capital Saves Bookshops

Three key strategies that helped drive the change (and the intangible capitals behind them):

Community — strong focus on local connections (relationship capital)Curation — emphasis on the value add of the staff choices and recommendations (human capital)Convening — building the capacity to promote and run events to bring together like-minded customers (structural capital)A New Way of Looking at Intangible Capital

Articles

ArticlesThe Learning Journey of IC Missionaries: Intuition, control, and value creation with John Dumay

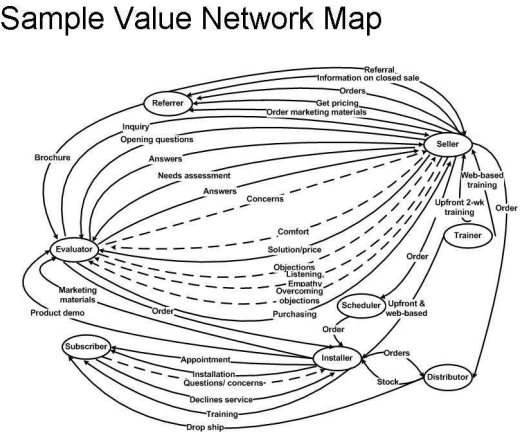

Optimized for Growth: Case Study of a Sales Organization with Verna Allee

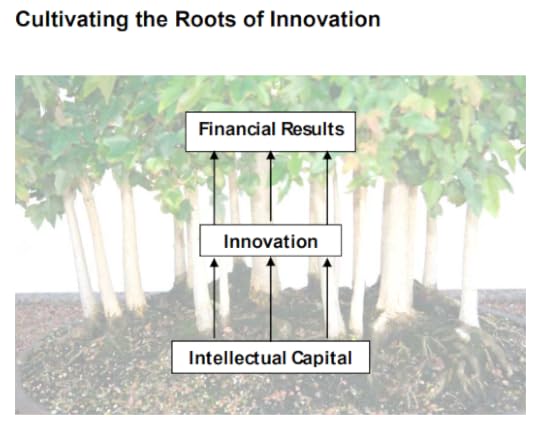

Cultivating Innovation: Lessons from America’s Chief Innovation Officers

[image error]

[image error]

December 15, 2022

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 31: June Holley

June Holley is a Network Weaver, researcher, and Writer at the Network Weaving Institute. The author of the Network Weaver Handbook, she has developed and implemented strategies for systems shifting, self-organizing networks that catalyze transformation. She is exploring how to network those working on transformation around the world and co-create the systems needed to support collaborative learning to advance the field.

In 1981 June discovered complexity science and became intrigued with the process of transformation. How could communities change in ways that would make them good places for everyone? For the next two decades, she worked with others in Appalachian Ohio to catalyze cascades of network experimentation, observing and documenting the dynamics that enabled many hundreds of people to start and then expand businesses in rural Appalachia. With these newly minted entrepreneurs, she mobilized dozens of area organizations to collaborate, self-organize and create an environment that would help these businesses innovate, expand, and work together to create an effective support system for networked entrepreneurs.

After twenty years as executive director of the Appalachian Center for Economic Networks (ACEnet), she stepped down to devote her energies to helping communities around the globe form system shifting, self-organizing networks by training and supporting network weavers and helping new networks form.

I met June at the Ohio KM Cluster in Cleveland in 2006. She is based in Athens, Ohio.

EducationOhio University — MA, sociology, 1981–1982Temple University — MEd, social science education, 1969–1970Profiles LinkedIn NetworkWeaver Network Weaving Institute Twitter Facebook BooksNetwork Weaver Handbook: A Guide to Transformational Networks

An Introduction to Network Weaving

Podcasts

Creating a Personal Network for Transformation

Building meaningful, lasting and impactful connections through purpose-led network weaving

Everyone a network weaver

Videos

YouTube

Collaborative Funding for a Just Transition

Introduction to Network Weaving

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Presentations

SlideShare

Trust in Networks

Basic Network Concepts

Articles by Others

Collective Change and the Culture of the 21st Century

by Christine Capra

What are you learning about Network Leadership?

by Deborah Meehan

What is Network Weaving? — Q & A

by Natalie WilliamsOther Content

Network Weaving Institute Writing

Network Weaver Mailings

Resources — NetworkWeaver

Scoop.it

Medium

Network Weaving Institute Blog

LinkedIn Posts

ResearchGate

Network Weaving Facebook Group

Weavr App: Build more impactful networks and communities

Building Smart Communities through Network Weaving with Valdis Krebs

Podcasts

Creating a Personal Network for Transformation

Building meaningful, lasting and impactful connections through purpose-led network weaving

Everyone a network weaver

Videos

YouTube

Collaborative Funding for a Just Transition

Introduction to Network Weaving

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Presentations

SlideShare

Trust in Networks

Basic Network Concepts

Articles by Others

Collective Change and the Culture of the 21st Century

by Christine Capra

What are you learning about Network Leadership?

by Deborah Meehan

What is Network Weaving? — Q & A

by Natalie WilliamsOther Content

Network Weaving Institute Writing

Network Weaver Mailings

Resources — NetworkWeaver

Scoop.it

Medium

Network Weaving Institute Blog

LinkedIn Posts

ResearchGate

Network Weaving Facebook Group

Weavr App: Build more impactful networks and communities

Building Smart Communities through Network Weaving with Valdis Krebs

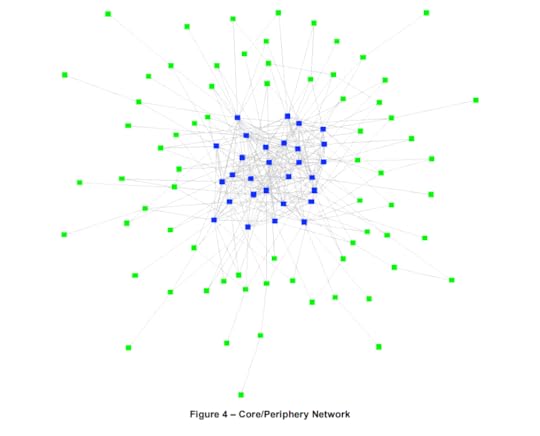

Figure 4 shows a well-developed core/periphery structure. The blue nodes are the core, while the green nodes reside in the periphery. This network core is very dense — not all cores will have as high a concentration of connections as this one. Too much density can lead to rigidity and overload of activity. Monitoring your network using social network analysis can help you see where your network needs to shift connections to match the current environment.

At this point the network weavers’ initial task are mostly completed. Now, attention turns toward network maintenance and building bridges to other networks. The network weavers can begin to form inter-regional alliances to create new products, services, and markets — or to shape and influence policy that will strengthen the community or region. This happens by connecting network cores to each other utilizing their peripheries. The network weavers maximize the reach of the periphery into new areas, while keeping the core strong. The weavers now focus on multi-core projects of large substance that will have major impact on the community.

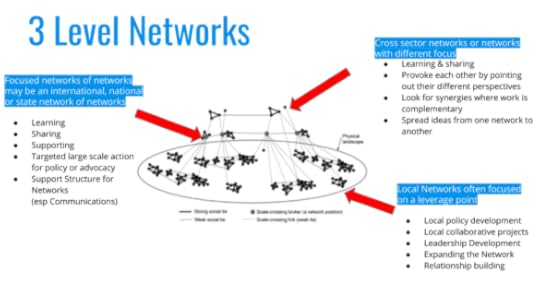

The Transformative Power of Networks of NetworksThree Level Networks for Transformation: Networks need to be part of three types of networks.

Local Networks are networks formed in a particular locale, usually a city, town or in rural areas or a multi-county region.Focused Networks are networks, often national (though they may be state, multi-state or international), that focus on a particular issue, problem or alternative.Networks with Other Networks: Networks can really benefit when they network with other networks. These types of networks help networks be transformative either through their differences or through their power of aggregation. However, this type of network is most likely to be neglected. These networks can be one of three different kinds:networks of networks with a similar focus formed to create the numbers needed for effective large actionscross sector networksnetworks that are quite different in purpose but can be constructively provocative for each other and stretch everyone’s world views [image error]

[image error]

December 9, 2022

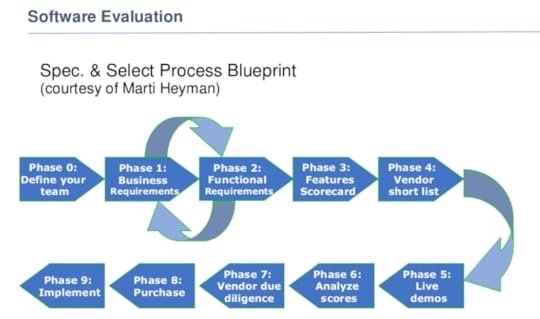

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 30: Marti Heyman

Marti Heyman designs, builds, and implements metadata solutions to enable the discovery of data, information, and knowledge.

Marti Heyman designs, builds, and implements metadata solutions to enable the discovery of data, information, and knowledge.Marti Heyman designs, builds, and implements metadata solutions to enable the discovery of data, information, and knowledge. She is driven by a passion to connect people to the information and knowledge they need — when they need it. She is experienced in many facets of information management and knowledge organization.

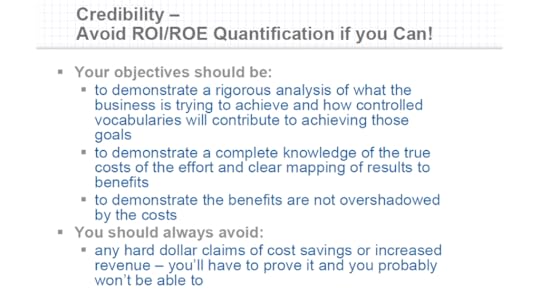

Marti focuses on generating revenue and cost savings through metadata architecture (including design, development, and implementation of taxonomies and other controlled vocabularies) and knowledge capture, storage. and retrieval in a manner that facilitates maximum return for the enterprise. Marti and I overlapped at Deloitte from 2009–2011. She is based in Ocala, Florida.

ExperienceOwner and Principal Consultant — Heyman Information Services, LLC, 2022 — PresentExecutive Director, Metadata Strategy and Operations — OCLC, 2016–2021Information Creation and Curation Topic Committee Member and Co-Chair — National Information Standards Organization, 2012–2021Adjunct Professor — Drexel University iSchool, 2008–2018Executive Director, Metadata Standards and Services — Cengage Learning, 2012–2016Director, Knowledge Management Strategy — InQuira (acquired by Oracle), 2011–2012Global Knowledge Management — Deloitte, 2009–2011 and 2000–2006Global Director of Taxonomy Delivery Services — Dow Jones (EMG), 2007–2009Taxonomist and Content Expert — Solution.com, 1999–2000Sr. Information Scientist, Research Technician — DuPont, 1983–1999EducationDrexel UniversityMBA, Business Management, 1999–2001MLIS, Library and Information Science, 1994–1996University of Delaware — BS, Chemistry, 1990–1993The Johns Hopkins University — BA, Social Anthropology, 1978–1982Profiles LinkedIn Twitter Facebook Profiles in Knowledge Book ChapterWhere Do We Go From Here?: Charleston Conference Proceedings, 2015 edited by Beth Bernhardt, Leah Hinds, and Katina P. Strauch, pages 536-538: Not So Strange Bedfellows: Information Standards for Librarians AND Publishers — with Betty Landesman — PDF

Videos

Taxonomies in the Real World

The New Age of (Web) Discovery: New Resource Metadata Standards (ISTE 2013)

ROI Analysis for Taxonomy Programs

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Conferences

2015 Charleston Library Conference: Not So Strange Bedfellows

with Betty Landesman

2019 SLA (Special Libraries Association): Taxonomy Tools and Tool Evaluation

NISO (National Information Standards Organization)2020

The Complexities of Vocabularies

2021

Z39.4, Criteria for Indexes

Taxonomy Boot Camp

2005

Developing an Enterprise-wide, Global Taxonomy (Case Study)

with Peter Doliska2007

Spec & Select: How to Be Efficient & Effective in Purchasing Taxonomy Software

2014

Getting Started

:

Buy It or Build It? How Do You Make the Decision?

Other Content

Not So Strange Bedfellows: Information Standards for Librarians AND Publishers

with Betty Landesman

Keeping the beat: how controlled vocabularies affect indexing

Bringing index standards into the twenty-first century

Building Successful Relationships with IT Professionals

KM Maturity Model: Request for your views

Presentations

LRMI Presentations from ISTE: New Resource Metadata Standards

with Michael Jay and Roger Rosen

The Complexities of Vocabularies

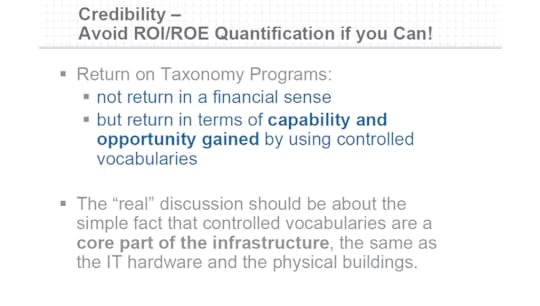

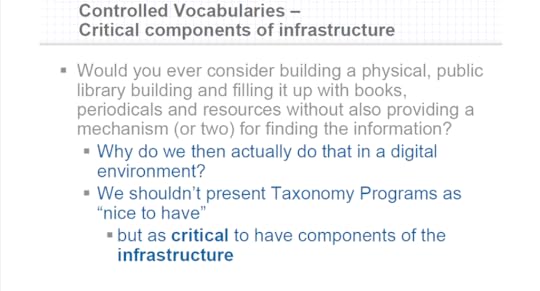

Ensuring ‘ROI’ and ‘ROE’ on Taxonomy Programs

Videos

Taxonomies in the Real World

The New Age of (Web) Discovery: New Resource Metadata Standards (ISTE 2013)

ROI Analysis for Taxonomy Programs

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Conferences

2015 Charleston Library Conference: Not So Strange Bedfellows

with Betty Landesman

2019 SLA (Special Libraries Association): Taxonomy Tools and Tool Evaluation

NISO (National Information Standards Organization)2020

The Complexities of Vocabularies

2021

Z39.4, Criteria for Indexes

Taxonomy Boot Camp

2005

Developing an Enterprise-wide, Global Taxonomy (Case Study)

with Peter Doliska2007

Spec & Select: How to Be Efficient & Effective in Purchasing Taxonomy Software

2014

Getting Started

:

Buy It or Build It? How Do You Make the Decision?

Other Content

Not So Strange Bedfellows: Information Standards for Librarians AND Publishers

with Betty Landesman

Keeping the beat: how controlled vocabularies affect indexing

Bringing index standards into the twenty-first century

Building Successful Relationships with IT Professionals

KM Maturity Model: Request for your views

Presentations

LRMI Presentations from ISTE: New Resource Metadata Standards

with Michael Jay and Roger Rosen

The Complexities of Vocabularies

Ensuring ‘ROI’ and ‘ROE’ on Taxonomy Programs

Content by Others

Marti Heyman on ROI for Taxonomy Initiatives

by

Patrick Lambe

Selecting Software for Taxonomy, Thesaurus and Ontology Management

by

Heather Hedden

Content by Others

Marti Heyman on ROI for Taxonomy Initiatives

by

Patrick Lambe

Selecting Software for Taxonomy, Thesaurus and Ontology Management

by

Heather Hedden

[image error]

[image error]