Joline Godfrey's Blog, page 2

March 25, 2014

Happy Birthday, Gloria

In 1994, Gloria Steinem wrote the foreword to my book, No More Frogs to Kiss: 99 Ways to Give Economic Power to Girls.

She didn’t agree to write it with a breezy, ‘Sure, no problem.’ She was careful, skeptical at first, but open—willing to consider. So it was not until I met with her, submitting to a lively and pointed conversation intended to make sure my work had integrity and I measured up, did she gift me her words. It was an afternoon I shall never forget.

Discussing economic justice, capitalism and women’s empowerment with Gloria Steinem was surreal. Sitting in her upper east side Manhattan living room, I found my head flying between intense engagement (Gloria’s intellect is in steady 4th gear—you have to keep up) and that ‘pinch me’ wonderment of, ‘Am I really here?’

1994 was a fraught time in the quest for women’s economic power. Take Our Daughters To Work Day had just launched the year before and it was a controversial idea (really—we were JUST suggesting that showing girls possibility was a good idea—who knew that would cause such a maelstrom?). Women were economically invisible, though in the 90s there were already something like 10 million women entrepreneurs in the US who were making jobs, spurning conventional companies to take charge of their own lives. Entrepreneurs and single moms had been running their business and home economies for decades but were still battling glass ceilings and an either/or calculus that trapped women between roles as castrating feminists or subservient little women; sexy vamps and dull suited professionals.

At that point Gloria had been fighting the good fight for a long time and by the mid-90s had become a kind of godmother to young women who were trying to figure out how to make feminism relevant to their own lives without actually adopting their mothers’ feminism. They aspired to all the goals that earlier eras of feminists sought: how to be independent; powerful; socially responsible. And they looked to her to help them define what became known as ‘third wave’ feminism. One of the questions prevalent as I sat in her living room that day was, ‘What did economic power look like when practiced by feminists at the end of the 20th century?’

When it comes to economic power, one theme has been the base note throughout each era of feminism. Feminists have consistently held that it was not enough to be equal. Or as the lyrics of an old protest song put it:

“If I’m going to play the game, I’m going to change the __ __rules…”

Gloria wanted to know if I was using financial education to change the rules or just trying to get girls to play the same old game. Were we teaching girls about cooperatives, she wanted to know. Were we encouraging social enterprise not just enterprise? Did I really think women could run companies without being co-opted? Why companies? Why not non-profits?

These were questions I had spent years contemplating; there was nothing she could throw at me that I wasn’t prepared for that day. Yes, yes, yes, I could say. But I also said that my first goal was to create a new generation of economically powerful women—so they could create their own business models, determine their own ways of being financially fit, without having to bend to anyone’s rules: economic self-determination for women was what we were talking about. I didn’t/still don’t have an agenda for what women should do: only that they have the knowledge, the freedom, and the economic skills and confidence to choose what they want to do.

That afternoon she agreed to write the foreword. Gloria’s courage is inestimable and her ability to fuse the personal and the political for the sake of social justice is exquisitely well tuned. In the foreword she shared her story—and her mother’s story, infusing the small book I had written with the power of her voice and life experience.

In celebration of her 80th birthday I am sharing a part of that foreword here.

A foreword by Gloria Steinem,

excerpted from No More Frogs to Kiss: 99 Ways to Give Economic Power to Girls.

This was written two decades ago, in 1994.

It took me years to learn what the boys around me seemed to know in their bones, as well as to learn with every paper route and summer job: that $50 earned through one’s own efforts was more rewarding than $500 received as a dependent, that working in the world outside the home was a way to find an identity in the world as well as to survive, and that doing a good job could be a joy in itself.

It took me even longer to discover that the idea of an income of one’s own as just “something to fall back on”—which may be a more rare phase now, but is still one directed at girls—was a myth even when I was hearing it. Only when I was in my thirties and feminism had begun to challenge such myths did I realize that my own mother had loved her work and the independence it gave her. After earning egg money on a family farm as a little girl, doing bookkeeping and needlework as a student, and becoming a math teacher to please her mother (for whom teaching was the ultimate thing “to fall back on”), she finally found the career of her heart as a pioneer in the “masculine” profession of newspaper journalism. GIving up her work as a reporter to follow her husband and raise my sister was the beginning of the many sacrifices of the self that broke my mother’s spirit, even before I was born, and turned her into the sad woman I knew. She, too, had been made to abnormal compared to the “feminine” myth of subservience, and a little embarrassed by her working-class mother, who was always economically active, whether it was digging a kitchen garden, ghost writing sermons for the church next door, gambling on horse races, or saving money to buy a second small house as rental property. Though my mother greatly admired her mother-in-law, a pioneer in vocational education, suffrage, and elected office, she also absorbed this idea that this upper-middle class woman’s work was more acceptable because it was done under the ladylike disguise of volunteerism.

That’s the amazing thing about myths. They are so powerful that we internalize them even when they contradict our deepest experience. So we blame ourselves for not conforming to their impossible standard, whether it’s “happily ever after” (a marzipan coating on reality even when people only lived to be fifty), or the idea that an adult woman should be happy living in childlike dependency (even though an adult man could not).

No single book can dispel all the myths much less outline a better way in all its diversity, but the one in your hands takes on this task early, radically, and with spirit. For one thing, its pages are full of examples—real-life, imaginative, multicultural examples—of girls who are succeeding at enterprises that many would still think unlikely for adult women. GIrls themselves will be inspired by these stories. After all, unless you’ve seen a deer, it’s hard to see a deer. That’s why nothing is more valuable than role models. As a byproduct, however, I wouldn’t be surprised if adult women pick up this book for its value to the next generation and also find themselves moved to action by realization “If a girl can do this, so can I!”

I’m not privy to the personal economic journey Gloria continued on these last two decades, but I know she continues to make women’s economic self-determination part of our American Story, indeed, part of the global human story. She has shown us all ‘the deer.’ And for being a role model for so many of us, I send her love, gratitude and wishes for a Happy, Happy Birthday.

February 6, 2014

Lost and Learned in Translation

By Whitney Webb

Taking a slightly different approach to Christmas, I returned to Cambodia this past December to run short financial literacy workshops for teens at two orphanages that I volunteered with back in 2010. In the last three years I’ve gained experience and appreciation for the power of financial education. Working as the COO of Independent Means, and a trainer to several families, I’ve seen the impact that financial skills can have on a young person’s life. With a new objective in mind, my coworker and longtime friend, Genine, and I decided to help teach teens living in those orphanages basic financial skills.

Cambodia is one of the poorest nations in the world and the teens living in those orphanages have little opportunity to handle money for day-to-day needs, or practice the skills they need for financial independence. That being said, we found them to be savvy, intelligent, motivated and aware of the basics of economics and finance, even if they didn’t yet know how to verbalize it.

Genine and I adapted and created the following curriculum:

What is finance? What is microfinance? What is a bank?

Savings and budgeting

Loans and interest

Entrepreneurship

How to leverage human, social, intellectual, and financial capital

Instead of focusing on the charts, vocabulary, and activities that we used to cement these ideas (you are welcome), I’m going to focus on my takeaways from the sessions:

1. Passion is great. But it is passion plus knowledge that makes real change. As a volunteer in Cambodia nearly 4 years ago, I think I believed that just being there was going to improve things. I taught English and helped with grant proposals, doing the only things I was equipped to do. Looking back, both of these contributions could have easily done more harm than good, even with the best intentions. Money without proper oversight and implementation can have disastrous results, especially in a country ridden with corruption. Education without structure and context can lead to confusion and frustration for those trying to learn.

I returned to Cambodia a bit older, more experienced, and much more realistic about the impact I could make. I had never run financial literacy sessions for teens in developing countries, but I do understand the nature of financial services in poor countries from my work with Kiva and several Microfinance Institutions in Rwanda. And from my work with Independent Means, I understand how to teach financial concepts to adults, teens, and even children who can’t yet read. I felt comfortable that my background gave me a fair shot at equipping these teens with the language and concepts to feel more confident about independent life, and at the least, help them know the right questions to ask.

[image error]I hope to take what I learned, and hopefully some other people who want to learn along with me, on another endeavor…coming soon.

August 26, 2013

Radio Interview With Koren Motekaitis

In the so-called lazy, hazy days of summer, nothing seems to be slowing down at Independent Means. I have several topics that are stirring around and are almost ready for print, but until those are fully formed, I thought I’d share this radio interview with Koren Motekaitis. Koren gave me a chance to muse out loud about kids and money. i’d be interested in your comments. And I hope you have a few hazy, lazy days left before the post Labor Day rush begins!

LISTEN HERE on how she really does it.com

July 15, 2013

On Finance

Survival—it’s one of man’s strongest, most basic instincts. Yet time and again, I see families drive themselves to the brink of financial disaster following the death of a parent, because the parents didn’t realize this truth at the time of their estate planning. It’s become a rather predictable phenomenon in my practice to hear clients say,

“Not my family. My family would never do that. My kids would never treat each other that way. My brother would never do that to our family business. My second spouse would never treat my children like that after I’m gone,”

and so forth. As family members, we forget that an inheritance—be it a house, business, money, or anything valuable—tends to change how heirs view and treat each other more frequently than you might imagine. The problem is preventable. But not if one takes a naïve stance towards human nature, family roles, and perceived or real power within a family unit.

It’s understandable that we want to believe the best about our loved ones. It’s not that our families don’t love each other or are not inherently well meaning. Rather, it’s that we don’t realize the natural human survival instinct, influenced by complications of self-esteem, may manifest in many negative psychological ways, such as narcissism, greed, sibling rivalry, anger, rigid defensive behaviors, attempts for power, self-interest, and more. Through human evolution and other environmental influences, these characteristics have become so strong and ingrained in human nature that, more often than not, they supersede our most civilized rational intentions.

We can ruin our families for generations… yes ruin them… when we ignore or dismiss this fact. The good news is that now there are ways in the estate planning process to minimize the pitfalls of human instinct.

A Holistic Approach

Today, the wisest and most successful long-term estate-planning approaches for most families are holistic. This means they engage the whole family and embrace H.B. Karp’s philosophy in his book, The Change Leader. Karp states that, “No human being has the right to make a unilateral decision that affects the lives of other individuals without offering them a voice in that decision.” I can see many of you and your professional advisors responding with, “Ugh. I have to involve everyone in the family? That’s extra work. I could lose control of the situation. How much more would that cost me up front?”

Today, the wisest and most successful long-term estate-planning approaches for most families are holistic. This means they engage the whole family and embrace H.B. Karp’s philosophy in his book, The Change Leader. Karp states that, “No human being has the right to make a unilateral decision that affects the lives of other individuals without offering them a voice in that decision.” I can see many of you and your professional advisors responding with, “Ugh. I have to involve everyone in the family? That’s extra work. I could lose control of the situation. How much more would that cost me up front?”

These are reasonable reactions and questions. The answers are, “Yes, involve everyone in the family who matters to you. And yes, it’s a little more work up front, but the long-term benefits far outweigh the costs in time, effort, emotional trauma, and dollars. And no, you won’t lose control of the situation. I guarantee it.”

Here’s how the holistic approach to estate planning works (you can read more about this method of planning at www.familiesandwealth.com): The senior generation keeps the control but asks the succeeding generation(s), in a structured and controlled environment, for their input on all of the issues that could impact them after the parents are gone. Before the process begins, a document is signed by everyone involved giving the lawyer permission to guide the process and interact with each generation. The document specifies who the lawyer actually represents (usually the senior generation) so that the lawyer’s legal and fiduciary responsibility to the client is clear. In our office, if an expert is needed to help everyone calmly reach an understanding about the goal, we call in a family communication facilitator. After the formalities are handled, the lawyer (and family communication expert, if needed) begins focusing, facilitating and managing the family’s communications toward an estate plan that works for everyone.

Ultimately, the succeeding generation presents their ideas to the senior generation and if those ideas are fair, just, and equitable, then those ideas may be adopted by the senior generation and drafted into the testamentary or other controlling legal documents. If the attorney is experienced at this holistic approach, he or she will know how to guide the process toward a harmonious and effective conclusion.

Bring Everyone Together

Perhaps the most important tip I can pass along from my many years of estate planning is to tell you not to ignore history. Estate planning processes are changing to this more precautionary, preventive approach for a reason. The toll on your family, both emotionally and financially, is far less the more you use a long-sighted, whole-family approach to estate planning. Like a good insurance plan, it’s not wise to leave these situations to chance. Too many things can go wrong. If you still find yourself hesitating, consider how much the average family fight can cost in legal fees. If a typical, litigated divorce these days averages between $15,000 to $30,000, with hourly lawyer’s rates running from $150 to $1,150, you can imagine how much more costly it could become with multiple litigants and lawyers and a case that drags out for years! I’ve seen cases where a single person will hire up to four and even as many as 25 lawyers to advise and fight their case for them if they think they’re entitled, or “right,” or feel they’ve been wronged.

It’s not a matter of what’s true. It’s a matter of what they perceive, feel, and want. While other kinds of cases can be grounded in fact, with estate plans you just have people getting upset and suing because their feelings got hurt! If we follow this line of thinking into the worlds of finance, sports and entertainment, even a $30,000 court case is cheap. The divorces of Michael Jordan, Neil Diamond, Harrison Ford and Steven Spielberg each cost more than $100 million, according to Reuters. And again, that’s just a contested divorce between two people! Remember, it is not just the wills of the famous, like singers Michael Jackson, Frank Sinatra, and John Lennon or oil magnates like J. Howard Marshall II (Anna Nicole Smith) that get disputed.

It’s not a matter of what’s true. It’s a matter of what they perceive, feel, and want. While other kinds of cases can be grounded in fact, with estate plans you just have people getting upset and suing because their feelings got hurt! If we follow this line of thinking into the worlds of finance, sports and entertainment, even a $30,000 court case is cheap. The divorces of Michael Jordan, Neil Diamond, Harrison Ford and Steven Spielberg each cost more than $100 million, according to Reuters. And again, that’s just a contested divorce between two people! Remember, it is not just the wills of the famous, like singers Michael Jackson, Frank Sinatra, and John Lennon or oil magnates like J. Howard Marshall II (Anna Nicole Smith) that get disputed.

The key is to remember that no parent will ever be able to predict with 100% certainty who will feel what if they try to put together a simple, quick plan without consulting the rest of their family during the decision-making process. By bringing everyone together in a neutral, emotionally safe, respectful, structured & controlled setting, you at least have an opportunity to guide the next generation through the issues that might arise for them and mitigate the outcome. It’s too late after the family leader is gone. When the emotional, psychological, physical and financial “safety” net you (or they) provide is no longer there, the urge to survive is so strong it does outweigh human rationality. “Not my family?” I don’t know. Do you really want to leave it all up to chance when there’s a less fallible way of avoiding hurt feelings and family litigation?

by John Ambrecht, Esquire

John Ambrecht, JD, MBA, LLM, is managing partner of Ambrecht & Associates, a U.S. & international estate planning, trust, tax, & tax litigation law firm in Montecito. Co-author of the book For Love & Money: Protecting Family &Wealth in Estate & Succession Planning, Worth magazine listed him among the country’s top 100 lawyers. For more information, visit www.TaxLawSB.com.

John Ambrecht, JD, MBA, LLM, is managing partner of Ambrecht & Associates, a U.S. & international estate planning, trust, tax, & tax litigation law firm in Montecito. Co-author of the book For Love & Money: Protecting Family &Wealth in Estate & Succession Planning, Worth magazine listed him among the country’s top 100 lawyers. For more information, visit www.TaxLawSB.com.

July 1, 2013

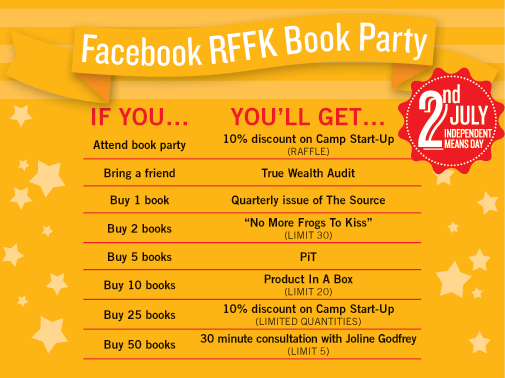

RFFK Book Party

This Giveaway Guide shows you how you can win all sorts of prizes and discounts on Independent Means products. From games to financial education tools, the Raising Financially Fit Kids Book Party offers a wide variety of resources and ideas for parents and money mentors of kids of all ages.

We hope you will join us tomorrow

July 2, from 9:00am-3:00pm PST,

to celebrate the updated edition of Joline Godfrey’s classic. More prizes and activities are in store, so don’t miss out! Follow this link to join the party:

https://www.facebook.com/events/134410270092380/

June 17, 2013

Pound Foolish, Financial Education, and Success

I think a lot about what success means in the context of financial education.

How do we know if the methods and content we offer families have any impact? How can families know if the work they are doing is worth the time and money invested? What exactly does success look like?

In the early days of Independent Means (actually back when we were still a fledgling non-profit in the early 1990s) I plowed forward with our programs mostly as a leap of faith. I was scared silly most of the time because I really didn’t know if anything we were doing would make a real difference or not. It was an experiment—and at the time I felt it was better to try something than do nothing. Still, I worried all the time about whether I had anything of value to offer.

Now, in the light of two decades in the field, I am confident. I’ve acquired some wisdom, made some verifiable observations, seen impact, made mistakes large enough to affect my learning curve, and I no longer suffer from secret fears of offering snake oil. Even so, we’re constantly searching for reliable ways to measure and report success, whatever that is—and it is no surprise that different families think of success in different ways.

For some families it’s a demonstration of expertise: Does my son/daughter know how to calculate the time/value of money? Can they manage a budget?

For others it’s a matter of trust: Can I send them away to school and feel secure they will make good judgments on their own? If I increase their allowance and pay it out monthly, will they manage wisely through the end of the month? Three months? Can I reduce the amount of subsidy we’re providing to that 25 year old?

And for others, it’s the embodiment of values, demonstrated in a recent conversation with a college freshman. The family meeting had gone well that morning, and over lunch, conversation turned to a consideration of how the family’s financial education program was proceeding after the first two years.

At one point I turned to C, the eldest grandchild and a freshman at a top NYC college. “How has this process been for you?” I asked. “What impact do you think it has had on you?”

C. thought for a moment and said, “Last year at Christmas I went shopping with some of my friends. And I was aware they were buying gifts for their parents with the parents’ own credit cards. That struck me as very weird. I’d saved money from a summer job to buy presents for my parents and my sister, and I took a lot of care with what I chose. They bought things randomly, without much thought to what their parents might actually like. I think the process has made me think pretty carefully about how I make decisions about money.”

C. doesn’t yet manage her budget to the penny as well as some of the other kids we work with, but she is a thoughtful young woman who is mindful of her financial habits. I think her family and I agree that her attitude is a “success” and she is on a path of life long learning—her knowledge will build over time as an outcome of the values and mindfulness of her financial behavior. And in the meantime, we meet regularly to deepen her skills and awareness. Success in this case is an emergent, unfolding process.

This notion of success is preoccupying me more than usual these days, in part because of the publication of a new book I’ve been enthusiastically encouraging everyone I know to read: Pound Foolish by Helaine Olen. Olen’s book is a long overdue critique of the ways the so-called personal finance industry is entwined with financial institutions, celebrity experts, and money made on the financial naïveté of otherwise smart people who mistakenly assume that fiduciary responsibility is a standard that still exists in this country.

This notion of success is preoccupying me more than usual these days, in part because of the publication of a new book I’ve been enthusiastically encouraging everyone I know to read: Pound Foolish by Helaine Olen. Olen’s book is a long overdue critique of the ways the so-called personal finance industry is entwined with financial institutions, celebrity experts, and money made on the financial naïveté of otherwise smart people who mistakenly assume that fiduciary responsibility is a standard that still exists in this country.

Sadly, as Olen makes clear, the fiduciary standard (your advisor’s first responsibility is to your financial well being, not his or her company’s) is rapidly and casually being replaced by a new standard of ”reasonableness.“ And this means that the advice now offered—often in the guise of education—is as often a cover to make money on the consumer’s lack of knowledge. It’s a juicy read, illuminating the ways financial institutions and celebrities make money warning against the very scams they have a hand in.

But her cynicism is hard edged and unforgiving. It’s well earned. She has been reporting on these issues for a long time and has come face to face with the dark side of the financial industry. In Olen’s world, there is no room for any effective financial education; no possibility of any advances in effective strategies to build financial fluency. She has a fully mapped out explanation that all is untrustworthy and unsavory. And she buttresses her POV with some important but narrow research authored by Lew Mandell, a professor of finance emeritus and former dean of the School of Management at SUNY Buffalo.

Olen excels as the pontificator of what is not working; however, she has not put forth much about what should be done. There is a section on her website that lays out a few general ideas that address both issues of consumer financial fluency (we need to talk about our money) and the potential for corruption (ban all commission sales). Everything Olen points out is good and worth pursuing but perhaps it is my own cynicism that leads me to believe that the financial industry will not change without a change in the mood—and literacy—of its market: the people. Financial literacy and education is as important to financial consumers speaking to their advisors as some degree of automotive literacy is to people speaking with mechanics. One of the reasons the financial industry may have lost some of its way is because it realized just how clueless the rest of us are.

It is clear we must do something, but if the financial industry cannot be trusted to provide sound financial education, then why can we not include instruction in schools? This is a reasonable question that many intelligent people, including myself, have wondered often. This is also an area that Olen criticizes, though her criticism is mostly parroting the work of Lew Mandell, a professor of finance emeritus and former dean of the School of Management at SUNY Buffalo.

Lew was one of the first to jump on the financial education bandwagon years ago when the topic first emerged as one strategy in the welfare to work policies established in the Clinton administration. Mandell was a serious advocate of financial education and on the board of a number of the early advocacy groups. including Jump Start (which I always thought of as more of a lobbying group for big financial institutions than an advocacy organization that actually cared about the well-being of young people). Though it has been a few years since the two of us have talked, I’m convinced that Lew was genuinely optimistic about the potential of financial education. Until he started to evaluate impact.

What Mandell and Jump Start found in a 2008 survey, as I knew they would, was that school-based, short, intermittent programs had limited impact. Having tried tenaciously to make impact through the school systems myself—both public and private—I came painfully to understand that in spite of the best intentions of people like him and I, schools were not an effective delivery system. They didn’t have the bandwidth, the value base, or the expertise to deliver serious, impactful financial education programs. So it wasn’t that financial education didn’t work—it was that the methods, the delivery systems, and the instructors at that time were not effective.

This is not to say that educators and administration are inept, or that schools fail our children. The thing that cannot be replicated in school, and the thing that is so important with successful financial education, is that the concepts and language must be tied to experience—both practical experience and the family experience. Schools must present a one-size-fits-all strategy because they do not have the time or resources to put each child on their own learning plan. Learning about compound interest in a classroom can be miserable. However, putting that in the context of a personal savings goal creates relevancy and application. Making it a family experience creates the learning culture that communicates financial principles as shared experiences and connected values.

And even with all of those things—relevant instruction and a family of learners—financial fluency still requires what the mastery of a sport, a musical instrument, or another language requires: practice, practice, practice. One can no more master the skill and art of managing a budget, stewarding significant assets, or being an effective philanthropist in a few afternoon sessions, or even in an hour a week for a few months, than you can deliver a decent piano recital or hold your own in a serious tennis match without a well conceived learning plan that is practiced over time.

Perhaps because Junior Achievement has been around for over a hundred years and its model seemed so effective (give a volunteer a few kids to help make a bird house and sell it, and you’ll raise a generation of entrepreneurs), we wanted to believe that financial education was a cinch to master. And to be fair, in the years before anyone could go online to buy stock, take out a loan, make a big purchase, give away large sums of money, or commit fraud under an assumed identity, financial education seemed more basic. Mid-century Junior Achievement was a simpler time—when banks were regulated, compound interest actually accumulated something, and the level of sophistication the average person required was considerably less than is needed now by every member of the family.

So as much as I appreciate Ms. Olen’s work, I’m genuinely concerned her cynicism will be contagious. And now with the new release for the 10th Anniversary Edition of Raising Financially Fit Kids (Ten Speed/Random House), I worry that families already reluctant to commit to the hard work of helping family members acquire fluency will throw up their hands in despair. For the most part, the families we work with are true thought-leader families—well aware that mastery of anything of value takes time, effort, practice, commitment, good techniques, and committed teachers.

So as much as I appreciate Ms. Olen’s work, I’m genuinely concerned her cynicism will be contagious. And now with the new release for the 10th Anniversary Edition of Raising Financially Fit Kids (Ten Speed/Random House), I worry that families already reluctant to commit to the hard work of helping family members acquire fluency will throw up their hands in despair. For the most part, the families we work with are true thought-leader families—well aware that mastery of anything of value takes time, effort, practice, commitment, good techniques, and committed teachers.

This has never been more important. We need more thought-leader families. As boomers age and trusts are transferred from one generation to the next, the Age of Disruption is in full gear. It has never been easier to give money away so fast; to invest in more mind-boggling change; to risk so much on such big dreams. Helping next-gen family members use family assets—financial and human—to benefit from the disruptions underway in transportation, energy, space, medicine, and agriculture, rather than be undone by those disruptions, is serious business. And turning away from opportunities to build financial fluency because we are too cynical to trust anything or anyone or because we are afraid to try anything because we do not wish for it to become “another failure” is a dangerous path to follow.

The quest for ways to measure and report success has been continuous. In the first decade, when financial education was mostly a tactic to help enforce new welfare-to-work policies implemented in the Clinton administration, any promise of “success” was mostly a leap of faith. This is because financial education is a lot like growing asparagus. It takes two years of dedicated work, care, and maintenance to get edible asparagus grown from seed. Likewise, we can teach some concepts in a day, some in a week or a month. We can create a basic level of fluency over the course of a year. But we won’t see progress for years to come. Longitudinal studies—designed to track people as they learned over time—were too expensive to run, and nobody can still agree on the metrics for what constitutes “success” (knowing definitions for words like beneficiary and Class A stock? being able to calculate compound interest? make 20% more earnings over your lifetime than your non-educated colleagues?). Indeed, people like Olen may claim there are no successes simply because we haven’t learned how to measure them yet.

Olen’s work is the easiest in many ways—the financial industry and the notion of financial education is rife with a myriad of issues that need to be addressed. The work that I and other passionate educators do is much harder. I have found success in the bespoke curriculum, offering customized education plans for families. A consequence of that approach is that the population I first served on my journey—at –risk youth—could not afford the work I offer now because it is so labor intensive. I don’t yet have an answer for how to make really effective, excellent financial education available to everyone. But I do at least know what effective financial education looks like, and I am ever hopeful that we will find a way to not only measure, but create success for all.

May 17, 2013

Kids, Camp Start-Up, and the Disruptor Generation

I attended the Milken Global Summit this week where I was dizzied and dazzled by evidence that “life as we know it” is changing more rapidly than we collectively realize. A panel on precision medicine illuminated that as the ability to screen genomes becomes routine, current medical diagnostics will become obsolete. Elon Musk talked nonchalantly about terraforming Mars, a concept I first encountered in a sci-fi novel by Kim Stanley Robinson. Drones were discussed as a new delivery system that could replace Big Brown, and satellites with absurd new powers will redefine the quaint communication systems in place today. All around me were casual conversations about the coming disruptions of online education, alternative energy, electric cars, and the seeming insignificance of our actual brains compared to the new wave of smarter, cooler, and ubiquitous computers.

I attended the Milken Global Summit this week where I was dizzied and dazzled by evidence that “life as we know it” is changing more rapidly than we collectively realize. A panel on precision medicine illuminated that as the ability to screen genomes becomes routine, current medical diagnostics will become obsolete. Elon Musk talked nonchalantly about terraforming Mars, a concept I first encountered in a sci-fi novel by Kim Stanley Robinson. Drones were discussed as a new delivery system that could replace Big Brown, and satellites with absurd new powers will redefine the quaint communication systems in place today. All around me were casual conversations about the coming disruptions of online education, alternative energy, electric cars, and the seeming insignificance of our actual brains compared to the new wave of smarter, cooler, and ubiquitous computers.

When any system is disrupted, overturned, or revolutionized, there are always winners and losers. Nick Dunne, the husband under suspicion in the runaway best seller Gone Girl described how disruption works in this way:

“We had no clue that we were embarking on careers that would vanish within a decade. I had a job for eleven years and then I didn’t, it was that fast. All around the country magazines began shuttering, succumbing to the sudden infection brought on by the busted economy. Writers (my kind of writers: aspiring novelists, ruminative thinkers, people whose brains don’t work quite quick enough to blog or link or tweet) were through. We were like women’s hat makers or buggy whip manufacturers: Our time was done.”

Anyone 35 and older must intuit this “brave new frontier” we are entering. And no parent attending the Milken Conference could help but leave with a renewed mission to go home and introduce their children to the final frontier (space) or the undiscovered frontier (the ocean). Others were thinking about how to break it to their children, intent on becoming doctors, that studying genomes would be safer than med school as we’ve known it. And parents whose fortunes are invested in funds that will be undermined by the “next new thing” surely left with a new zeal to mentor their kids to be disruptors before they are disrupted.

The world is a wild and unforgiving place when it comes to the speed of change. and I’m aware that in choosing to be a disrupter I am practically a chemical catalyst for life at the speed of light. Though I am part of the “slow food” movement and have built a “slow money” company, I seem unable to stanch the speed of anything.

So to help kids slide into the stream of change at warp speed, we offer Camp Start-Up, a summer program for teenagers growing up in the Age of Disruption.

So to help kids slide into the stream of change at warp speed, we offer Camp Start-Up, a summer program for teenagers growing up in the Age of Disruption.

No matter how privileged, smart, well connected today’s 10 year old, 16 year old or 25 year old is, the world they are inheriting requires a new kind of preparation. Anyone who knows me at all knows this is one of Independent Means programs I am most proud and fond of. This year we have moved the program to Santa Clara University, in the heart of Silicon Valley, to expose kids directly to the forces—and the opportunities—coming at them.

Teens who attend Camp Start-Up this year will spend time with a Google brainiac who will give them a tour of the campus and challenge them to consider what it would be like to work in a true meritocracy. Kiva Fellows will share stories of making a difference in far flung corners of the world, and all the teens will get a chance to go behind the scenes at Tesla, getting a glimpse of a car company that may be to cars what the Model T was to the horse.

At Camp Start-Up this year we will emphasize how to spot weak signals from the future (so teens can be proactive, not reactive, in their life dreams). They will practice the ability to spot and leverage opportunity and will go home with their first business plan done and presented—a skill much of the planet is still trying to master. And perhaps because I am also a bit wary of the unintended consequences that come with speed of light change, we’ve increased the time we will spend on conversation and case studies that explore ethics, stakeholder management, and social responsibility. All this will be imbedded in 12 days of fun, creativity, and adventure. We know teenagers, and unless we serve a serious program with serious fun, we’ll lose them. But this is our 19th year of operation and in all that time we’ve lost less than 1% to homesickness or lack of interest.

I feel good about our ability to prepare kids for the Age of Disruption—if not their actual arrival.

May 14, 2013

As the Titles Pile Up, It’s Time to Share: Recent Great Books

I’ve been on planes a lot lately, so I’ve been consuming books in a voracious way. In between flights I pepper talks with,

I’ve been on planes a lot lately, so I’ve been consuming books in a voracious way. In between flights I pepper talks with,

“and another book you MUST read is…”

I’ve done this so often lately that I decided to list a few here so I could more efficiently share my new discoveries. You will surmise correctly from this list that I am an eclectic reader. This will either make you think of me as a person with a wide range of interests or an eccentric who scans the world like an owl for a diversified meal of small prey after dark. Either way, this is not a boring list!

Among my new reads, must reads, is Resilience by Andrew Zolli. Andrew is the Exec Director of PopTech and a brainiac by any measure. This book is one of those “a ha” reads that illuminates the world while it puts words and pictures on your deepest intuitive knowledge. Resilience is wonderfully upbeat, and hopeful—it explains why in the midst of head-spinning change we are adapting, can adapt, will adapt, and maybe even get better. If you have not yet organized a family book club, this is the book that you might choose to launch one. A great read for anyone 15+, this is a book that will speak to each generation in a relevant and useful way. Download it before you get on that next flight.

Accidentally I read two books that, in the light of the Boston Marathon bombings, put a new light on war, random victims, and the implications for how cultures and communities are affected by the surreal dimensions of man’s inhumanity to man. The first of my accidental reads was a novel called The Book of Jonas by Stephen Dau. Jonas got up in the middle of the night to empty his kidneys in a privy well away from his main house, escaping as in a strange dream the horror of bombs obliterating his family, his home, his village. A young boy, he runs instinctively into the mountains and hides in a cave, only to meet up with one of the soldiers responsible for the bombing. Their encounter and their impact on one another and on the lives of people who cared for them is a reminder that war is the great unraveler—its impact trickles and pours from one person and place to another…guns, bombs, and drones, no matter how well “controlled” are indiscriminate in the damage they do. This book pushed my pragmatic self to the edge of a radical pacificism. Like the second accidental book, Escape from Camp 14 by Blaine Harden, I want to buy cases of these books and mail them to Congress (do we think those guys actually ever read anything that isn’t delivered as a poll or a review on their own behavior?).

Escape from Camp 14 was apparently first brought to the attention of the American public by 60 Minutes (I missed that episode). But the book surely brought North Korea to my consciousness in a whole new way. The book chronicles the existence of prison camps in North Korea that make Stalin’s Gulag look like summer camp—and it does this by following young Shin Dong-hyuk, as he escapes, impossibly, from Camp 14 and makes his way to China, South Korea, and eventually the US. I am embarrassed I was not more aware of the barbarity of North Korea—and it’s impact on our humanity.

I also finished Gillian Glynn’s Gone Girl. Fair warning: you will stay up all night to finish it. And Ellen Foster, by Kaye Gibbons, is the amazingly vivid and moving story of an 11 year old whose name is not really Ellen Foster—and therein lies the tale.

Finally, lately I have gotten a number of requests for my favorite science fiction books (anyone who has heard me speak lately knows I am finally fessing up to the genre as one way I have kept my eye on weak signals from the future). At the head of the list is Kim Stanley Robinson (The Mars Trilogy: Red Mars, Green Mars, Blue Mars) whose stories contain remarkable scientific details. (May have something to do with his scientist wife, but in any event, he’s a brilliant writer). And now that the Mars Rover, Richard Branson, and Elon Musk are bringing Mars to our doorstep, his scenarios of terreforming Mars seem completely plausible.

Finally, lately I have gotten a number of requests for my favorite science fiction books (anyone who has heard me speak lately knows I am finally fessing up to the genre as one way I have kept my eye on weak signals from the future). At the head of the list is Kim Stanley Robinson (The Mars Trilogy: Red Mars, Green Mars, Blue Mars) whose stories contain remarkable scientific details. (May have something to do with his scientist wife, but in any event, he’s a brilliant writer). And now that the Mars Rover, Richard Branson, and Elon Musk are bringing Mars to our doorstep, his scenarios of terreforming Mars seem completely plausible.

I’m also a Neal Stephenson fan because he was the one who, for me, changed science fiction from ‘a distant planet, a thousand years in the future’ to “here” in the not so distant future. Cryptonomicon was the first book of his I read–it is a page turner and enormous fun. I went from there to Diamond Age and then Snow Crash. Both are dark but provocative. He has launched a new project I’m following with interest: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_Hieroglyph

Of course Isaac Asimov and Ray Bradbury are the old classics—Asimov nailed the idea of singularity, which has entranced Ray Kurzweil all these years, and Bradbury was a much more philosophical thinker than most people understood. Shortly after Bradbury died, I shared a paper he wrote for USC’s management magazine in the late 80s, It’s a doozy and if you can’t find it, let me know. And Philip Dick has been so well discovered by Hollywood you hardly have to read him any longer, but I do like Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?.

Frank Herbert, who wrote the Dune series, got me paying attention to water issues long before I moved to California. And Mary Doria Russell’s book, The Sparrow is a very moving, very unusual take on science fiction. One of my favorite books, period. Wow, I could go on but this is already TMI. But check out our GoodReads website for titles we think are relevant to financial education in the broadest sense!

May 13, 2013

As the Titles Pile Up, It’s Time to Share: Recent Great Books

I’ve been on planes a lot lately, so I’ve been consuming books in a voracious way. In between flights I pepper talks with,

I’ve been on planes a lot lately, so I’ve been consuming books in a voracious way. In between flights I pepper talks with,

“and another book you MUST read is…”

I’ve done this so often lately that I decided to list a few here so I could more efficiently share my new discoveries. You will surmise correctly from this list that I am an eclectic reader. This will either make you think of me as a person with a wide range of interests or an eccentric who scans the world like an owl for a diversified meal of small prey after dark. Either way, this is not a boring list!

Among my new reads, must reads, is Resilience by Andrew Zolli. Andrew is the Exec Director of PopTech and a brainiac by any measure. This book is one of those “a ha” reads that illuminates the world while it puts words and pictures on your deepest intuitive knowledge. Resilience is wonderfully upbeat, and hopeful—it explains why in the midst of head-spinning change we are adapting, can adapt, will adapt, and maybe even get better. If you have not yet organized a family book club, this is the book that you might choose to launch one. A great read for anyone 15+, this is a book that will speak to each generation in a relevant and useful way. Download it before you get on that next flight.

Accidentally I read two books that, in the light of the Boston Marathon bombings, put a new light on war, random victims, and the implications for how cultures and communities are affected by the surreal dimensions of man’s inhumanity to man. The first of my accidental reads was a novel called The Book of Jonas by Stephen Dau. Jonas got up in the middle of the night to empty his kidneys in a privy well away from his main house, escaping as in a strange dream the horror of bombs obliterating his family, his home, his village. A young boy, he runs instinctively into the mountains and hides in a cave, only to meet up with one of the soldiers responsible for the bombing. Their encounter and their impact on one another and on the lives of people who cared for them is a reminder that war is the great unraveler—its impact trickles and pours from one person and place to another…guns, bombs, and drones, no matter how well “controlled” are indiscriminate in the damage they do. This book pushed my pragmatic self to the edge of a radical pacificism. Like the second accidental book, Escape from Camp 14 by Blaine Harden, I want to buy cases of these books and mail them to Congress (do we think those guys actually ever read anything that isn’t delivered as a poll or a review on their own behavior?).

Escape from Camp 14 was apparently first brought to the attention of the American public by 60 Minutes (I missed that episode). But the book surely brought North Korea to my consciousness in a whole new way. The book chronicles the existence of prison camps in North Korea that make Stalin’s Gulag look like summer camp—and it does this by following young Shin Dong-hyuk, as he escapes, impossibly, from Camp 14 and makes his way to China, South Korea, and eventually the US. I am embarrassed I was not more aware of the barbarity of North Korea—and it’s impact on our humanity.

I also finished Gillian Glynn’s Gone Girl. Fair warning: you will stay up all night to finish it. And Ellen Foster, by Kaye Gibbons, is the amazingly vivid and moving story of an 11 year old whose name is not really Ellen Foster—and therein lies the tale.

Finally, lately I have gotten a number of requests for my favorite science fiction books (anyone who has heard me speak lately knows I am finally fessing up to the genre as one way I have kept my eye on weak signals from the future). At the head of the list is Kim Stanley Robinson (The Mars Trilogy: Red Mars, Green Mars, Blue Mars) whose stories contain remarkable scientific details. (May have something to do with his scientist wife, but in any event, he’s a brilliant writer). And now that the Mars Rover, Richard Branson, and Elon Musk are bringing Mars to our doorstep, his scenarios of terreforming Mars seem completely plausible.

Finally, lately I have gotten a number of requests for my favorite science fiction books (anyone who has heard me speak lately knows I am finally fessing up to the genre as one way I have kept my eye on weak signals from the future). At the head of the list is Kim Stanley Robinson (The Mars Trilogy: Red Mars, Green Mars, Blue Mars) whose stories contain remarkable scientific details. (May have something to do with his scientist wife, but in any event, he’s a brilliant writer). And now that the Mars Rover, Richard Branson, and Elon Musk are bringing Mars to our doorstep, his scenarios of terreforming Mars seem completely plausible.

I’m also a Neal Stephenson fan because he was the one who, for me, changed science fiction from ‘a distant planet, a thousand years in the future’ to “here” in the not so distant future. Cryptonomicon was the first book of his I read–it is a page turner and enormous fun. I went from there to Diamond Age and then Snow Crash. Both are dark but provocative. He has launched a new project I’m following with interest: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_Hieroglyph

Of course Isaac Asimov and Ray Bradbury are the old classics—Asimov nailed the idea of singularity, which has entranced Ray Kurzweil all these years, and Bradbury was a much more philosophical thinker than most people understood. Shortly after Bradbury died, I shared a paper he wrote for USC’s management magazine in the late 80s, It’s a doozy and if you can’t find it, let me know. And Philip Dick has been so well discovered by Hollywood you hardly have to read him any longer, but I do like Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?.

Frank Herbert, who wrote the Dune series, got me paying attention to water issues long before I moved to California. And Mary Doria Russell’s book, The Sparrow is a very moving, very unusual take on science fiction. One of my favorite books, period. Wow, I could go on but this is already TMI. But check out our GoodReads website for titles we think are relevant to financial education in the broadest sense!

April 16, 2013

The Economics of Change (And why Kiva can’t get rid of me)

Theogene and his wife

By Whitney Webb

On January 19th, 2012, I was climbing a mountain in northern Rwanda, after taking a 3-hour bus ride plus spending an hour on the back of a motorcycle. I was covered in dirt, smiling, and on my way to meet Theogene, a borrower of a loan provided by Vision Finance Company and Kiva. My job was to interview him and verify an $800 loan that allowed him to buy and raise goats.

“Raising Financially Fit Families” event in Dubai

Exactly one year later, in January 2013, I found myself flying first class on Emirates Airline to meet with a group of wealthy families in Dubai. I was sipping champagne, still smiling, but contemplating how I had gotten to this moment. My assignment was to run a session on financial fluency and raising financially responsible families.

What led me from working with the poorest of the poor to the wealthiest people in the world? On a basic level, the common thread was finance. But during the heartbreaking decision to leave Rwanda and Kiva in order to work in Santa Barbara with Independent Means and Camp Start-Up, I have realized the end goals of these organizations are, in fact, the same. Regardless of where we fall on the economic spectrum, we are all trying to utilize our resources, opportunities, and hopes in the best ways possible—to make a better world for ourselves and others.

Visiting a group of client borrowers (and trying to not be so tall!)

When it comes to capital, the lesson I learn over and over is that it’s not just about the money. Yes, some form of capital is needed to propel us forward, but that can be in the form of human, social, intellectual, or financial capital. This idea is at the core of the microfinance model. No collateral? Tap into your social capital and band together with your friends and neighbors to qualify for a group loan.

But it is also at the heart of managing abundance. Have a few hundred million dollars at your disposal? Tap your intellectual and human capital to make sure you use it wisely and make real impact. Leverage your education to handle the extreme responsibilities and expectations of wealth; count on family and friends and be deeply conscious of your values as you make choices and decisions that will affect the stewardship of your resources—and your potential to actually change the world.

Happy and hopeful kids. Guess which one probably hadn’t seen a camera before…

I can’t reasonably say that the clients I work with in Dubai or Santa Barbara face challenges equal to those in Rwanda. The issue of feeding your family is more imminent and the consequences more dire than the issue of managing your funds well for the next generation. However, the strategies we use to tackle our issues, and the dreams we have for ourselves and our children, are eerily similar across the globe. In the end, I believe we are bound together by the shared qualities of compassion for one another, a willingness to leverage resources for a successful life, and a sustaining hope for the future.

It turned out that the values that got me to Rwanda (a desire to make a difference and impact the world) have helped me link two worlds that are usually held as mutually exclusive: the world of scarcity and the world of abundance. IMI’s culture and commitment to helping young people find purpose and meaning in the process of becoming financially independent make Camp Start-Up/Silicon Valley a great environment for inspiring and educating the next generation. Our mission is to teach teens how to manage, invest, and leverage their money and resources. But, the teens we work with want more than that. This partnership with Kiva brings to light the importance of global citizenship, socially responsible start-ups, and the many faces of an entrepreneur. I believe that this integration of financial intelligence and passionate commitment makes this years camp a place where the teens, staff, and volunteer mentors can be inspired, and excited about the possibilities of the future.

Every day I realize a new overlap between the missions of Independent Means and Kiva, and it gives me hope that the lines between non-profit and for-profit will blur as intention and purpose starts to play a bigger role in the way we run our companies and our lives. I hope this partnership between the two organizations is the beginning of many future collaborations as we do our part in making the world better, no matter how far apart our strategy and approach.

Check out Camp Start Up 2013: Silicon Valley

http://www.independentmeans.com/camp-start-up/