Linnea Tanner's Blog, page 43

July 8, 2020

Welcome to Day 4 of #RRBC’s July “SPOTLIGHT” Author Tour for Karen Black! @KarensStories

It is my pleasure to welcome you to Day 4 of RRBC’s July “SPOTLIGHT” Author Tour for Karen Black, a member of Rave Reviews Book Club. Below, you’ll learn about what inspired Karen Black to write and discover some of the work she has published. I hope you’ll support her at every stop of her blog tour!

Meet Karen Black

As soon as I learned to read, I became a voracious book lover. After I mastered “Dick and Jane,” Nancy Drew became my heroine, and Agatha Christie’s incredible Hercule Poirot fascinated me. Dick Francis was a favorite author of mine, too, probably because his novels took place at the racetrack. The Dick Francis novels fed my appetite for two loves: horses and mysteries.

In the old days, clouds had magical qualities. A favorite pastime was to watch them and find an image and create a scenario around it. Although I didn’t realize it then, cloud watching was my introduction to flash fiction. My childhood fascinations stayed with me and they are apparent in the stories that I write.

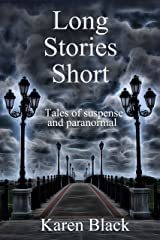

“Long Stories Short” is a collection of ten short stories. I tried to create scenarios that are believable, or at least within the realm of possibility. There are, of course, exceptions. For example, “Magic or Miracles” is a story with paranormal overtones that might be possible. But someone who doesn’t believe in what they can’t see might find “Indisputable Evidence” difficult to believe.

“LONG STORIES SHORT”

“Race into Murder” is my first novel, and it came as no surprise to those who know me, that it is a mystery set at a thoroughbred racetrack.

“RACE INTO MURDER”

My most recent eBook, “Treacherous Love,” is a short story about misdirected passion that often occurs in situations of domestic abuse. It is the first of several stories that will be included in my next anthology.

“TREACHEROUS LOVE: A SHORT STORY OF MISDIRECTED PASSION”

About Karen Black

Karen Black lives in the eastern United States, with her husband and a variety of critters, wild and domestic. Hobbies include herb gardening, wildlife watching and winemaking, though all are put on hold when she’s caught up in a story. With a lifelong affection for animals, a fascination with the supernatural and a background in criminal justice, the author draws on experience, as well as imagination to create stories that are believable, unique, and entertaining. Expect the unexpected.

Contact Karen Black at:

Twitter: @KarensStories – https://twitter.com/KarensStories

Facebook: Stories by Karen – https://www.facebook.com/StoriesbyKaren/

Website: Stories by Karen – https://storiesbykaren.org/

To follow along with the rest of her tour, please visit the “SPOTLIGHT” Author forum on the RRBC site!

***

If you’re an author and interested in receiving this kind of support for you and your work, please join us at RAVE REVIEWS BOOK CLUB! We look forward to adding your name to our roster and your books to our catalog!

July 5, 2020

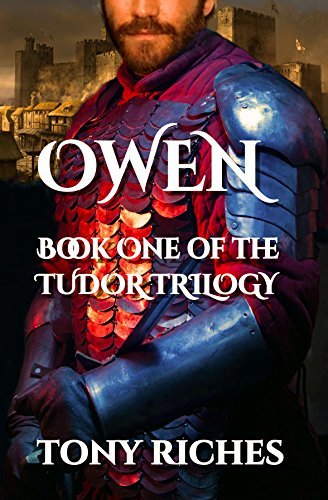

Book Review Owen by Tony Riches

Owen by Tony Riches

Owen by Tony Riches

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

The legacy of King Henry VIII has always fascinated me, but I knew very little about the earlier accounts of the Tudor dynasty. Thus, I selected Owen: Book One of the Tudor Trilogy by Tony Riches to learn more about how the Tudor Dynasty was established. The story of Owen, the great-grandfather of Henry VIII, is as fascinating as the tales about the legendary king. Told in the first-person perspective of Owen, the story begins in 1422 when he first meets his new mistress, Queen Catherine of Valois, the young widow of King Henry V. The queen’s young son, Harry (Henry VI), is crowned King of England and France. Nobles responsible for the young king’s upbringing tightly control the queen’s life and her influence on her son. Owen, serving as the Keeper of the Wardrobe, loyally serves and befriends Queen Catherine and gains her trust. Rumors of Catherine’s affair with the 2nd Duke of Somerset prompts a parliamentary statute that forbids her to remarry until her son comes of age. Soon after, Catherine and Owen fall in love and secretly marry in the backdrop of political turmoil that ultimately leads to the War of Roses.

Author Tony Riches has masterfully written a poignant love story narrated by Owen in the present tense. The moment-by-moment narrative helps the reader more actively engage with Owen’s life journey. The story is rich with vivid descriptions and natural dialogue that highlights Owen’s wit and cleverness. Although his childhood has been shattered by the loss of his Welsh noble parents and heritage, Owen becomes the unlikely second husband to Queen Catherine and the father of her children. Their secret love and marriage have tragic consequences in the backdrop of the War of Roses. Yet Owen’s firstborn son, Edmund, ultimately becomes the father of King Henry VII, the first monarch in the Tudor Dynasty.

Owen: Book One of the Tudor Trilogy is one of the best historical fiction novels I’ve read this year. I highly recommend this book to historical fiction readers, particularly those interested in the Tudor Dynasty.

July 2, 2020

Author Interview Thomas H. Goodfellow

It is my pleasure to introduce Thomas H. Goodfellow—an author who recently released his international thriller, The Insurmountable Edge (Book One). Though I don’t normally read and post reviews for thrillers, I found his debut novel to be unique with engaging characters whose smart, crisp dialogue spiced up the action scenes with humor. My husband, an avid reader of suspense, buried himself in the book and commented that the main character, Jack Wilder, reminded him of Jack Reacher who was created by Lee Child. Thus, I contacted Thomas Goodfellow for an interview which he graciously accepted.

Below you will find a brief biography, the interview, and the contact information for Thomas H. Goodfellow.

Thomas H. Goodfellow, Author of International Suspense

BIOGRAPHY

Thomas H. Goodfellow spends most of his time in California, Hawaii, Kentucky, and Wyoming. He is an avid hiker and a fly fisherman (he always throws the fish back). He also has a lot of cats, dogs, and horses.

AUTHOR INTERVIEW QUESTIONS:

Would you provide an overview of your debut novel, The Insurmountable Edge, that you recently released?

Rob Errera in Indiereader (Thanks Rob!), really hit the nail on the head in his review:

The Insurmountable Edge (Book One) is an on-point action thriller with a wisecracking antihero that will win over fans of Tom Clancy, Jeffrey Deaver and Robert Ludlum. PTSD makes for an unreliable narrator and a wild–at times surreal–ride in this military who-done-it…A tough-as-nails general who cares for a troubled teenage niece as well as a fellow soldier with post-traumatic stress disorder, is called out of retirement by a beautiful damsel-in-distress. If James Bond and John Rambo were mated in a secret government super-soldier laboratory–and the resulting male child raised by double dads Jack Ryan and Jason Bourne–he might grow up to be General Jack Wilder, star of The Insurmountable Edge (Book One) by Thomas H. Goodfellow.

What inspired you to write an international thriller about the United States pitted against China in the Middle East?

I think China is on a long march to destroy the United States. I’d prefer they did not succeed.

What inspired you to create the primary character, General Jack Wilde? What are characteristics that are unique to him that make him stand out among other heroes in this genre?

I think he’s tougher, smarter, better looking, more athletic, more talented, and has a better sense of humor than most of the other heroes. Not many of the others have even the slightest sense of humor so I really wanted to create a character who saw the world a little differently than most of them.

Is there any other character in The Insurmountable Edge that is your favorite? Explain why.

I love them all.

How often do your characters surprise you by doing or saying something totally unexpected?

Always.

Have you received reactions/feedback to your work that has surprised you? In what way?

Everyone who has read The Insurmountable Edge has raved about it. I didn’t expect that.

What are three things you think we can all do to make the world a better place?

Just one. Follow the Golden Rule.

What are the most important traits you look for in a friend?

Intelligence and a sense of humor.

What makes you laugh?

Marx Brothers movies. Woody Allen’s character in a comedy. Eddie Murphy’s character in Beverly Hills Cop. Caddyshack. The 2000 Year Old Man. Dave Chapelle stand-up routines.

You can purchase The Insurmountable Edge at the following sites:

You can contact Thomas H. Goodfellow and learn more about him at:

June 28, 2020

Caesar’s Invasions of Britain: Celtic Perspective

“Of the inhabitants, those of Cantium (Kent), an entirely maritime district, are far the most advanced, and the type of civilization prevalent here differs little from that of Gaul. With most of the more inland tribes, the cultivation of corn disappears and a pastoral form of life succeeds, flesh and milk forming the principal diet, and skins of animals the dress. On the other hand, the Britons all agree in dying their bodies with woad, a substance that yields a bluish pigment, and in battle greatly increases the wildness of their look. Their hair is worn extremely long, and with the exception of the head and upper lip the entire body is shaved.”

(Julius Caesar’s account of Britain)

Caesar’s Invasions of Britain: Celtic Perspective

Introduction

The following is a reblog of the post entitled, “Caesar’s Invasions of Britain: Celtic Perspective,” published at this site on August 31, 2015 by Linnea Tanner.

While researching Celtic history, I ran across an interesting book entitled, “History of the Kings of Britain,” which was written in Latin by Geoffrey of Monmouth in 1136 AD. This book traces the history of Britons through a sweep of nineteen hundred years, stretching from the mythical Brutus, great-grandson of the Trojan Aeneas, to the last British King, Cadwallader. Geoffrey claims he translated his stories from “a certain very ancient book written in the British language” that was given to him by Walter the Archdeacon. Though his work has been sharply criticized for its historical inaccuracies, there are bits of truth that cannot be completely discounted.

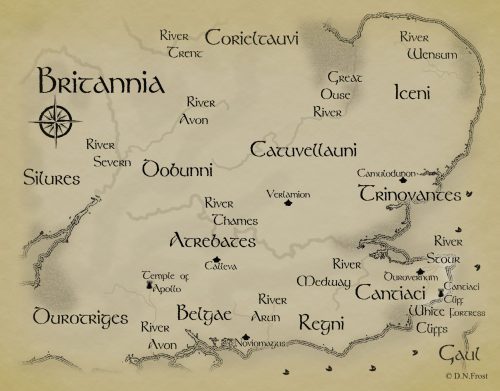

Celtic Tribes Southeast Britain

Of particular interest is Geoffrey’s account of Caesar’s invasions of Britain and his battles with Cassivellaunus which is told from his patriotic British viewpoint. What rings true in his story is the fragility of the British rulers’ egos and their lust for power, a weakness that eventually plays into the hands of Claudius who invaded Britain in 43 AD. Previous posts that have summarized Caesar’s Invasions of Britain from his accounts are located in the archives under the categories: Julius Caesar and Roman Invasion of Britain.

Below is a summary of Geoffrey’s version. One has to wonder if there are some truths from his version that put some of Caesar’s accounts into question.

Geoffrey’s Account of Caesar’s Invasions of Britain

Julius Caesar was fascinated with Britain as he had been told the Britons were founded by Brutus, a descendant of Aeneas who fled from the ruined city of Troy to Italy. Although the Romans were descended from the same ancient Trojan stock as the Britons, Caesar underestimated the Britons, believing it would be a simple matter of forcing them to pay tribute and to swear their perpetual obedience to Rome. Thus, Caesar dispatched a message to the British King, Cassivellaunus, with the demand that he pay tribute.

After reading Caesar’s message, Cassivellaunus became indignant and sent Caesar a written message that he refused to accept his terms of slavery. He further says, “It is friendship which you should have asked of us, not slavery. For our part, we are more used to making allies than enduring the yoke of bondage…we shall fight for our liberty and for our kingdom.”

The moment Caesar read this letter he prepared his fleet to set sail to Britain.

Collapsed Wall of White Cliffs Near Dover Photographed in 2012

King Cassivellaunus—along with his brother Nennius, his nephew Androgeus (Duke of Trivovantum), and other nobles—marched down to meet Caesar after he had landed and set-up his Roman camp near the Dover Cliffs. A fierce hand-to-hand battle ensued. In single combat, Caesar cut his sword into Nennius’ shield that he could not wrench out. Nennius, taking Caesar’s sword, raged up and down the battlefield killing everyone he met. The Britons pressed forward as a united front cutting the Roman forces into pieces. That night, Caesar reformed his ranks, boarded his ships, and sailed back to Gaul in defeat. Nennius succumbed to his wounds fifteen days after the battle and died. Cassivellaunus buried him with Caesar’s sword called Yellow Death, for no man who was struck by it escaped alive.

Celtic Shield Retrieved from Thames River

Celtic Swords Displayed at the British Museum

Two years later, Caesar prepared to cross the sea a second time to avenge Cassivellaunus for the humiliating defeat he had suffered at his hands. As soon as the king heard of this, he garrisoned villages everywhere and planted stakes shod with iron and lead below the water-line in the bed of the River Thames, up which Caesar would have to sail to attack Trivovantum.

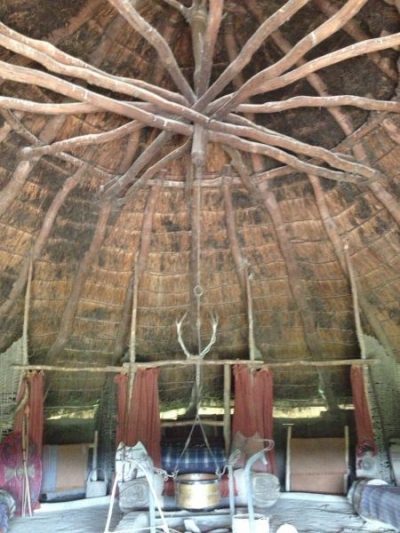

Replica of Celtic Village with Roundhouses

Cassivellaunus and every man of military age waited for Caesar to cruise up the Thames where his ships were ripped apart by the stakes. As a result, thousands of Romans drowned, but several survivors clambered with Caesar onto dry land. The King ordered his warriors to charge the remaining Romans. The Britons, outnumbering the Romans three to one, were victorious over their weakened enemy. Again, Caesar escaped to his remaining undamaged ships and sailed back to Gaul.

Celtic Horned Helmet Found at River Thames Date 150-50BC

Elated from his overwhelming victory, Cassivellaunus invited all his noblemen to a glorious feast where cows, sheep, fowl, and wild beasts in the hundreds were sacrificed as offerings to the gods. At the sporting events that night, the king’s nephew was beheaded by the nephew of Duke Androgeus as a result of a dispute. Cassivellaunus demanded that the Duke present his nephew in court for sentence. Androgeus refused.

Inside of Replica of Celtic Roundhouse for Chieftain

Enraged by the Duke’s refusal, Cassivellaunus ravaged his lands. In desperation, Androgeus dispatched a message to Caesar with a plea to help him restore his position. Only after the Duke sent his son, together with thirty young nobles as hostages, did Caesar depart for Britain a third time.

Replica of Ancient Roman Ship

This time, Cassivellaunus was sacking Trinovantum when Caesar landed. Upon hearing the news of Caesar’s return, the king abandoned his siege and rushed to meet his Roman adversary. When the two sides met, they hurled deadly weapons at each other and exchanged mortal blows with their swords. In an unexpected move, Androgeus and his forces attacked the rear of the king’s battle line, forcing his warriors to give ground from the assaults on both sides.

Cassivellaunus took flight from the battlefield and retreated to a hillfort. Caesar besieged the hillfort but still couldn’t defeat the king. Even now, when driven off the battle-field, Cassivellaunus and his battered forces continued resisting a man whom the whole world could not withstand. Caesar resorted to cutting off all means for the King’s retreat to starve them.

Example of Ancient Celtic Hillfort (Maiden Castle Dorchester)

After two days without food, Cassivellaunus sent a message asking Androgeus to make peace for him with Caesar. When the envoys delivered the message to Androgeus, he said, “The leader who is as fierce as a lion in peace-time but as gentle as a lamb in time of war is not really worth much.” Nonetheless, he was moved by the king’s pleas and went to Caesar to plead mercy for Cassivellaunus. Androgeus told Caesar, “All that I promise you is this, that I would help you humble Cassivellaunus and conquer Britain. He is beaten, and, with my help, Britain is in your hands. Yet I cannot allow you to kill him while I myself remain alive.”

Celtic Carnyx Serpent War Horn

Ultimately, Caesar made peace with Cassivellaunus who, in turn, promised yearly tribute to Rome. The tale ends well as Caesar and Cassivellaunus become great friends and give each other gifts. Androgeus travels to Rome as a guest of Caesar.

Concluding Remarks

Certainly, the above tale of Caesar’s Invasions of Britain differs from the Roman General’s account, but there are some similarities. Caesar wrote that, after Cassivellaunus brought down the King of the Trinovantes, his son Mandubracius fled to Gaul. Mandubracius begged for Caesar’s help in regaining the Trinovantes kingdom. On Caesar’s second invasion of Britain in 54 BC, Cassivellaunus fiercely resisted the Romans, but he eventually surrendered after they devastated his territories and other rival kings sought peace with his enemy.

Celtic Greaves Used to Protect Shins

Though Caesar was proclaimed a hero by the Roman Senate for his accomplishments in Britain, it can be argued his expeditions were not successful, for he did not complete the conquest. The scenario of British rulers fleeing to Rome and asking for help to regain their sovereignty from rival rulers repeats time and time again, up to the final conquest by Emperor Claudius in 43 AD. At that time, the King of the Atrebates, Verica, asked for help from Claudius in regaining his territory from Caratacus, an anti-Roman chieftain from the Catuvellauni tribe.

Richborough Roman Fort Ruins

To be continued

The next posts will provide an overview of rival dynastic kings that came to power in Britain between the time period of Caesar’s invasion of Britain in 54 BC up to Claudius’ conquest in 43 AD.

References:

Geoffrey of Monmouth, The History of the Kings of Britain, translated with an introduction by Lewis Thorpe; Penguin Books, New York; first published 1966.

Julius Caesar, The Conquest of Gaul, translated by Rev. F. P. Long and introduction by Cheryl Walker; Barnes & Noble, Inc., New York; 2005.

©Copyright August 31, 2015, by Linnea Tanner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

June 4, 2020

Author Interview Tony Riches

It is my pleasure to introduce Tony Riches—an author of both best-selling fiction and non-fiction books, a blogger, and a podcaster. He has published several historical fiction books set in the 15th and 16th centuries about one of the most fascinating dynasties in England—the Tudors. I was excited to learn that he lived near the Pembroke Castle which I visited in 2013 and found fascinating.

Below you will find a brief biography, interview, and contact information for Tony Riches.

Tony Riches Author

Biography

Tony Riches is a full-time UK author of best-selling historical fiction. He lives in Pembrokeshire, West Wales and is a specialist in the history of the Tudors. For more information about Tony’s books please visit his website tonyriches.com and his blog, The Writing Desk and find him on Facebook and Twitter @tonyriches

Author Interview Tony Riches

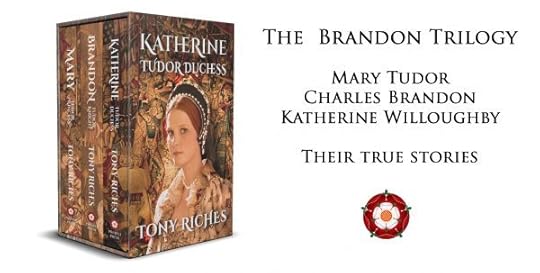

Would you provide an overview of the newest books or series that you have recently released?

My latest book is the conclusion to my Brandon trilogy, Katherine – Tudor Duchess. This began as a ‘sequel’ to my best-selling Tudor trilogy, with the intriguing story of Henry VIII’s little sister Mary, who briefly became Queen of France. I visited her home at Westhorpe and became fascinated by the adventures her second husband, champion jouster and best friend of the king, Charles Brandon, so decided to tell the story from his point of view. After Mary died, Charles married a fourteen-year-old heiress, Katherine Willoughby, so her story was perfect for the third book of the trilogy.

What inspired you to write historical fiction about the Tudors in the 15th and 16th centuries?

I was born in Pembroke, birthplace of King Henry VII, so have always been interested in finding out more about his story. I realised many visitors to Pembroke Castle had no idea he was born there, so my wife and I helped raise funding for the life-sized statue of Henry, now in front of the castle, so now he will always be remembered.

Henry Tudor Statue

How much research was involved in writing your books?

I usually spend at least a year visiting the actual locations, uncovering primary sources and planning each of my books. This has taken me to follow Henry and Jasper Tudor in exile to remote Brittany, although many of the locations are closer to home, as I live in Tudor Wales.

Is there any character that is your favorite in any of the books you have written? Explain why.

Owen Tudor, founder of the dynasty has to be my favourite, as although he came from modest beginnings, that didn’t stop him from secretly marrying the Queen of England and changing history. (Owen was also my first book to earn enough royalties to enable me to become a full-time author.)

Owen Book One Tudor Trilogy

How often do your characters surprise you by doing or saying something totally unexpected?

I like to stick to the historical facts, so they surprise me all the time. For example, Henry VII is thought of by many as ‘miserly’ but the records show he spent a fortune on his clothes and loved to gamble at cards (he often lost!) Mary Tudor didn’t complain when her brother married her off to the much older and sickly King Louis of France, and Katherine Willoughby risked everything for what she believed in.

Have you received reactions/feedback to your work that has surprised you? In what way?

I like hearing from readers, and one comment that I remember was from a mother in the US who said she’d bought all my books to help her son with his school work! Readers sometimes tell me they are descended from characters in my books, or that they are going to travel half way around the world to see the locations for themselves.

If you could have one skill that you don’t currently have, what would it be?

I need to learn to read medieval French and Latin, as I often find primary sources where I have to rely on someone else’s interpretation.

What might we be surprised to learn about you?

I play the tenor sax and met my wife when we played in a group together – it was called ‘Black Knight’ – a clue to my future career?

What makes you laugh?

Tudor TV dramas, such as when they ‘merged’ Henry VIII’s sisters, Mary and Margaret in ‘The White Queen’. I had to stop watching but still wonder why. Did they not find either interesting enough? Could they not afford two actresses? I also cringed when they made Margaret Beaufort into a scheming villain… and I could never believe Jonathan Rhys Meyers as Henry VIII – although I was happy with Damian Lewis in ‘Wolf Hall’.

What simple pleasure makes you smile?

Talking to my two-year-old grandson on Facetime, as he takes video calling entirely for granted – but I’m still amazed that such a thing is possible for free.

Tony Riches, Pembrokeshire, West Wales

You can contact Tony Riches and learn more about him at:

June 1, 2020

Caesar’s 2nd Invasion Britain 54 BC (Part 4)

‘Cities and Thrones and Powers,

Stand in Time’s eye,

Almost as long as flowers,

Which daily die.

But, as new buds put forth

To glad new men,

Out of the spent and considered Earth

The Cities rise again’

–Rudyard Kipling

Introduction

This is a reblog of Caesar’s 2nd Invasion of Britain 54 BC (Part 4) which was first published on June 9, 2013 on this website. Part 4 continues the historical and archaeological evidence that supports the theory that Julius Caesar’s invasions of Ancient Britain (Britannia) in 55-54 BC helped establish Celtic dynasties loyal to Rome. The political unrest between rival Celtic tribal rulers provides the backdrop of the epic historical fantasy series, Curse of Clansmen and Kings.

Below are highlights of Caesar’s second expedition after he learns that several of his ships had been damaged in a storm.

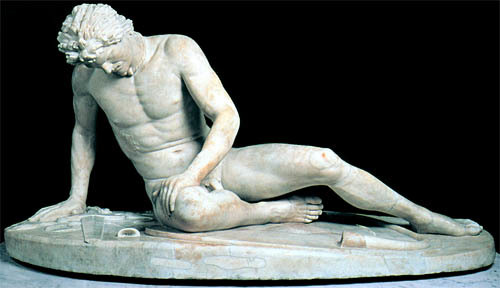

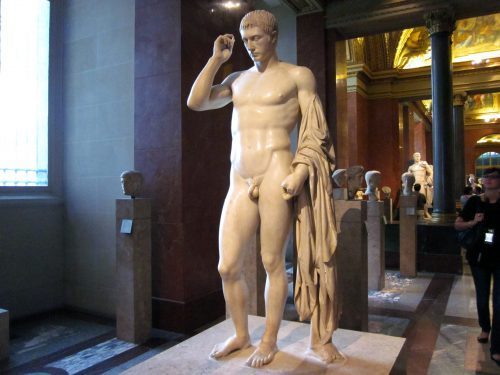

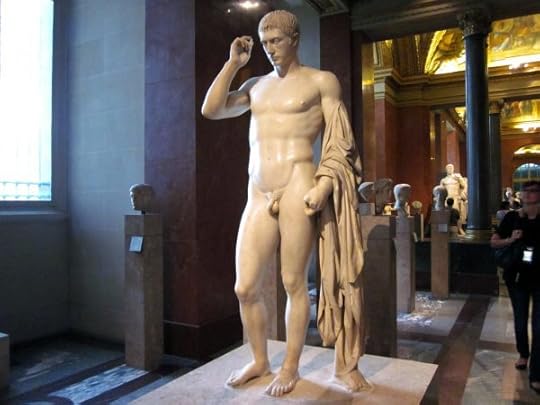

Statue of Julius Caesar Displayed at Louvre Museum

Caesar’s 2nd Invasion Britain

Purpose of the Second Expedition

In his accounts, Julius Caesar never gave a rationale for his return to Britain in 54 BC. However, it can be surmised that his single-minded march to the Thames River and from there to Essex was to barter for the return of Prince Mandubracius and to grant him sovereignty of the Trivovantes tribe. The prince had escaped to Gaul, seeking Caesar’s protection after his father had been brutally slain by Cassivellaunus—the ruler of the Catuvellauni tribe. Mandubracius was Caesar’s trump card for dividing the tribal kingdoms in their resistance to Rome. The strategy of ‘divide and conquer’ was a tactic that the Roman general had often used in his conquest of Gaul.

Southeast Britannia Showing Location of Celtic Tribal Kingdoms

March to the Thames

Julius Caesar had to halt his initial advance so his soldiers could repair ships that had been damaged in an overnight storm off the coastline. His army worked day and night for ten days to repair the sea vessels and to drag them on the beach into a fortified encampment. The huge task of protecting the fleet required a defensive line of four to five miles. The loss of time cost Caesar a resounding conquest, as the Britons had time to forget their political differences and to ally under a supreme commander, Cassivellaunus—the ruler of lands bounded by the north bank of the Thames River.

Replica of Ancient Roman Ship

Cassivellaunus had learned not to engage with the Roman army in open battle. He instead resorted to guerrilla tactics to menace the Roman army. Nonetheless, three Roman legions routed his main forces, forcing the Celtic warriors to withdraw to dense woodlands north of the Thames. There, the Britons prepared to resist.

Yet once again, the Roman troops displayed their discipline and training by fording the river in neck-high water. Not willing to risk an open engagement with the enemy, Cassivellaunus disbanded most of his forces and kept only 4000 charioteers to harass the flanks and rear of advancing Romans. He must have been bitterly disappointed that his forces could not even hold the Thames.

Celtic Chariot Displayed at Colchester Museum

Hidden Weapon

Caesar’s march into hostile territory, separating him from the main supply line, might have appeared to be fool-hardy. However, Mandubracius proved to be a valuable ally when he negotiated with envoys from the Trivovantes tribe to supply the Roman troops with grain and forty hostages in exchange for Caesar’s recognition of the prince’s rightful claim to the throne. Further, the young prince persuaded five other tribes that bordered the kingdom of Cassivellaunus to join him in submitting to Rome. The political implications of these tribal defections to Caesar were dramatic. The capitulating British leaders informed Caesar of the location of Cassivellaunus’ forces in the thick woodlands and marshes. The Roman legions promptly and effectively attacked the enemy warriors that resulted in the slaughter of many Britons.

Celtic Shield Retrieved from Thames River

Final Surrender

In one last desperate attempt, Cassivellaunus ordered Kentish tribes along the coastline to attack the Roman naval encampment to cut off Caesar from Gaul. The Romans were ready for the attack and inflicted several Celtic casualties and captured the leaders.

Cassivellaunus had no other option but to negotiate his surrender to Commius, the king of the Arbetrates tribe from Gaul. As mentioned in a previous post, Caesar had sent Commius as an envoy to persuade the Britons not to resist his first invasion of Britain in 55 BC. However, the British kings held Commius as a prisoner, but they eventually handed him back to Caesar as part of the negotiations in the first invasion. Any plans that Caesar had for staying in Britain had to be abandoned when he learned of serious trouble in Gaul that demanded his attention. He collected several British hostages, levied an annual tribute on the hostile tribes, and ordered Cassivellaunus not to attack either Mandubracius or the Trivovantes.

By the autumn equinox, Caesar’s troops returned to the coastline, where all of the sea vessels had been fully repaired. The ships had to make two voyages to ferry the innumerable hostages, prisoners, and Roman legions back to Gaul. It should be noted that Commius remained Caesar’s loyal client king throughout the Gaulish revolts of 54 BC. In return, Caesar allowed the Atrebates to remain independent and exempt from tax until Commius joined forces with Vercingetorix to defeat Caesar. More will be said about Commius in upcoming posts.

Pathway Along Coastline Near Dover, UK

Conclusions

In both expeditions, Caesar failed to understand his most formidable enemy —the strong tidal currents from the English Channel. The tidal current continued to be an obstacle that the Romans had to be overcome in their invasion eighty years later by Claudius in 43 AD.

White Cliffs of Dover

(To be continued)

The next series of posts will discuss the role of British hostages in forging alliances from Rome, the subsequent political unrest with emerging anti-Roman tribal leaders, and the cultural differences between Rome and Ancient Britain which precipitated the invasion by Claudius in 43 AD.

References:

Julius Caesar, translated by F. P. Long, 2005. The Conquest of Gaul; United States: Barnes & Noble, Inc.

John Peddie, Conquest: The Roman Invasion of Britain; Reprinted 1997 by St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Graham Webster, The Roman Invasion of Britain; Reprinted 1999 by Routledge, New York.

Christopher Vogler, The Writer’s Journey; 3rd Edition Reprinted by Sheridan Books, Inc., Chelsea, Michigan

© Copyright June 9, 2013, by Linnea Tanner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

May 21, 2020

Caesar’s 2nd Invasion Britain 54 BC (Part 3)

THE STANDARD PATH of the mythological adventure of the hero is represented in the rites of passage: separation—initiation—return. A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder where fabulous forces are encountered and a decisive victory is won, then the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow advantage on his fellow man—Joseph Campbell

Introduction

The following is a reblog of a post published on May 20, 2013 about Caesar’s 2nd invasion of Britannia. The epic historical fantasy series, Curse of Clansmen and Kings, is set in Britannia (modern-day Great Britain), Gaul (modern-day France), and Ancient Rome and spans the period from 24AD to 40AD prior to the invasion of Claudius in 43AD. This is Part 3 of the historical and archaeological evidence that supports the theory that Julius Caesar’s invasions of southeast Britannia (55-54BC) help establish Celtic tribal dynasties loyal to Rome. The political unrest of rival tribal rulers in 24AD sets the backdrop to APOLLO’S RAVEN (Book 1 Curse of Clansmen and Kings) where the Celtic warrior princess, Catrin, first meets the great-grandson of Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony).

Statue of Julius Caesar Displayed at Louvre

Caesar’s 2nd Invasion Britain

Prelaunch Preparations Redesign Ships

Due to the frequent tidal changes that Caesar encountered in his first expedition to Ancient Britannia in 55BC, he ordered his generals to construct smaller transports with shallower drafts for easier loading and beaching. The vessels’ beams were built wider to carry heavy cargoes, including large numbers of horses and mules. As a result of the redesign, the clumsy ships were difficult to maneuver and thus were equally fitted for rowing and sailing. It was not clear from Caesar’s accounts whether the purpose of this second exhibition was to conquer Britannia, to punish hostile tribes, or to open the isle to Roman trade. The unfolding events in his accounts suggest the primary objective was to establish pro-Roman dynasties that would be subsequently rewarded with lucrative trade for their loyalty.

Replica of Ancient Roman Ship

Description of Inhabitants

In his accounts, Caesar describes the population along the southern coast of Britannia to be densely populated by Belgic immigrants, who had crossed the channel from Gaul to plunder and eventually settle. There were thatch-roof, roundhouses everywhere that were similar to those in Gaul. Flocks of sheep and herds of cattle were plentiful. The inhabitants of Cantium (modern-day Kent), an entirely maritime district, were far more advanced than the inland tribes consisting of the original pastoral inhabitants who had their own traditions.

Replica of Celtic Village with Roundhouses

In common, all Britons dyed their body with woad that yielded a bluish pigment and in battle increased the wildness of their look. The men’s hair was extremely long and with the exception of the head and upper lip, the entire body was shaved.

Statue of Dying Celtic Warrior

Second Landing

On 6 July 54BC, at sunset, Caesar embarked from Portis Itius (modern-day Wissant France) to Britannia with a fleet of 800 ships that transported five legions (30,000 soldiers) and 2,000 cavalrymen. The tide turned the next morning, taking the ships with it. As a consequence, the soldiers had to row the ungainly vessels without stopping to reach the Kent coast by mid-day. Unlike the first expedition, there were no signs of the enemy to oppose the landing. Caesar learned later the tribal forces had been dismayed to see the vast flotilla in the English Channel and thus decided to seek a stronger position inland to fight.

Without any opposition, Caesar’s ships anchored and a site was chosen for camp.

Shingle Beach Near Deal UK where Julius Caesar Possibly Landed

Initial Conflict

A little after midnight, Caesar marched his legions twelve miles inland to the River Stour near Canterbury. The Britons fell back to a formidable position in the woods which Caesar described as being fortified by immense natural and artificial strength. The hill-fort was strongly guarded by felled trees that were packed together. Possibly this site was initially built for tribal wars. The Roman soldiers locked their shields above their heads to form a testudo (tortoise) to protect themselves from missiles while they hacked their way into the fortress and drove the British forces into the woods. Further pursuit was forbidden by Caesar as the countryside was unfamiliar and he needed sufficient time to entrench his camp.

Celtic Shield Retrieved from Thames River

Storm’s Wrath

The following morning, the Roman pursuit of the British fugitives began in earnest. Again Caesar underestimated the powerful forces of the English Channel. A terrible storm along the coast tore the ships from their moorings and drove them ashore. When Caesar received the bad news about the shipwrecks, he abandoned his speedy advance which would have desolated the Britons and returned his army to repair the damages to his vessels.

Frieze of Ancient Warship

(To be continued)

References:

Julius Caesar, translated by F. P. Long, 2005. The Conquest of Gaul; United States: Barnes & Noble, Inc.

Graham Webster, The Roman Invasion of Britain; Reprinted 1999 by Routledge, New York.

Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces; 3rd Edition Reprinted by New World Library, Novato, CA.

© Copyright May 20, 2013, by Linnea Tanner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

May 14, 2020

Caesar’s Invasion Celtic Britain 1st Expedition (Part 2)

The Call to Adventure: The first stage of the mythological journey—designated as the ‘call to adventure’—signifies destiny has summoned the hero and transferred his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of his society to a zone unknown—Joseph Campbell

INTRODUCTION

This is a reblog of a post that was published on April 26, 2013, by Linnea Tanner at this website. Based on historical and archaeological evidence, there is evidence that Julius Caesar’s invasion in 55-54 BC helped to establish dynasties in the two most powerful tribes of southeast Britain who pledged their loyalty to Rome. Below is a continuation of Caesar’s first expedition to Celtic Britain in 55 BC (Part 2).

Statue of Julius Caesar

Caesar’s Invasion Celtic Britain: First Expedition

Tidal Phenomena

After Caesar defeated the Britons near the Kent coastline, the tribal leaders surrendered, promising to serve his every need and to let him use the natives at his disposal. On the fourth day of the Roman expedition, eighteen ships carrying the cavalry were driven back by a sudden storm. On the same night, the full moon brought a tidal phenomenon that Caesar was not prepared to face. Waves surged up the beach and destroyed or damaged most of his ships. Caesar ordered some of his soldiers to repair the damaged ships using the timber and copper from the worst wrecks while he directed others to forage for corn in the surrounding fields.

Replica of Ancient Roman Ship

There was a marked change in the attitude of the Celtic chieftains who secretly met and pledged to take up arms again and starve out their invaders. They covertly called upon their followers to fight. Caesar was unaware of their treachery as there had not been any suspicious hostile movements by local inhabitants who continued to farm and to visit the Roman encampment. That all changed when outposts outside the main camp reported to Caesar that there was a cloud of dust in an area that had been taken by the Romans. Now suspecting a new plot had broken among the natives, Caesar ordered a battalion to march a considerable distance to where Celtic warriors in chariots had ambushed some of his soldiers foraging for food.

Pathway Along Dover Cliffs

Chariot Fighting

Caesar had not previously encountered chariot fighting which threw his infantrymen into dire confusion. The Celtic charioteers, galloping wildly down the whole field of battle, terrified the Roman soldiers by charging their horses into the melee of fighting. A Celtic warrior would leap out of the chariot and fight on foot. Meanwhile, the driver positioned a short distance from battle to retreat whenever they became overpowered. Thus, the Celts combined the skill of an infantryman with the mobility of the cavalry. Even on the most treacherous terrain, the charioteers had perfect control over their horses.

Replica of Celtic Chariot at Colchester Castle

Final Roman Victory

Though these chariot-fighting tactics challenged the military discipline of the Romans, Caesar returned back to camp with his remaining troops. In the meantime, news of Rome’s weakness and an appeal to expel the invaders from their entrenchments spread throughout the countryside. Caesar resolved to crush the advancing enemy forces on foot and horse by charging them with two legions. The Celtic warriors could not withstand the Roman attack and many of them were killed. Several of the villages and farms were burned to ashes.

Celtic Village with Round Houses

Tribal leaders agreed to surrender under the terms that the number of hostages previously imposed would double. With the equinox close on hand, Caesar feared his repaired ships might not withstand the ocean’s storms and thus he sailed back to the Continent with a few of the hostages. When he ordered the remaining hostages from Britain, most of the tribes refused to send them.

During the following winter months, Caesar ordered his generals to build a fleet of newly designed ships that could better handle the seas in the British Channel for his next invasion.

Frieze of Roman Warship

(To be continued)

References:

Julius Caesar, translated by F. P. Long, 2005. The Conquest of Gaul; United States: Barnes & Noble, Inc.

John Manley, 2002. AD 43—The Roman Invasion of Britain. Charlston, SC: Tempus Publishing Inc.

Graham Webster, The Roman Invasion of Britain; Reprinted 1999 by Routledge, New York.

Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces; 3rd Edition Reprinted by New World Library, Novato, CA.

© Copyright April 26, 2013, by Linnea Tanner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

May 5, 2020

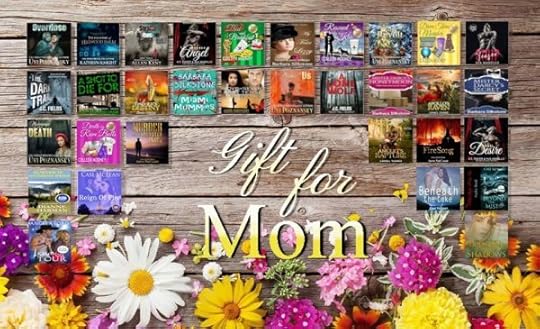

Gift for Mom Event

Looking for the perfect gift for Mother’s Day? I’ll be joining a select group of authors who have joined forces to bring you amazing audiobooks. You’ll have a chance to listen to our audiobooks. Celebrate Mother’s Day with a chance to win one of them! Meet authors from all genres and listen to excerpts of their audiobooks on May 7th and 8th. I’ll be giving away audiobooks in my Curse of Clansmen and Kings series: Book 1: Apollo’s Raven, Book 2: Dagger’s Destiny, and Book 3: Amulet’s Rapture.

✿ Join the Facebook event hosted by Uvi Poznansky and you’ll be entered. GIFT FOR MOM

✿ Take a look at what you can win if you’re a GOING guest. Click FREE AUDIOBOOKS

✿ Never listened to an audiobook before? It’s easier than you think. Click NEVER LISTENED

✿ CLICK BELOW to join the Gift for Mom Event

Release of Amulet’s Rapture Audiobook

First, the Good News! The audiobook of Amulet’s Rapture has now been widely released at various retail sites, including the following:

Now, the Bad News. Audible and Amazon have significantly delayed the release of the Amulet’s Rapture audiobook. The delay has been the result of a few authors, publishers, and producers engaging in fraudulent activity to exploit the Audible Promo code program. The misuse led to an unprecedented volume of newly created accounts, increased account activities, and content submission, resulting in significant production delays to the detriment of the ACX service and community. This has unfortunately impacted me as an author. As an alternative, I’ll be offering giveaway codes that can be redeemed at an authors-direct site. For those who subscribe to my newsletter, will have a chance to win books, e-books, and audiobooks in the Curse of Clansmen and Kings series in the SOLSTICE SUMMER GIVEAWAY which will be held next week.

Thank you for your continued support during this difficult pandemic. Keep safe and stay well!

Best wishes,

Linnea

April 28, 2020

Julius Caesar’s Invasion of Britannia (Part 1)

Celtic Tradition of Raven:

I have fled in the shape of a raven of prophetic speech (Taliesin). The raven offers initiation—the destruction of one thing to give birth to another. For deeper understanding, the heroine must journey through darkness to emerge into the morning’s new light.

INTRODUCTION

This is a reblog of a post that was published on March 28, 2013, by Linnea Tanner on this website. The historical fantasy series, Curse of Clansmen and Kings, is envisioned to be five-book saga spanning from 24 to 40 AD in Britannia (England), Gaul (modern-day France), and Rome prior to the invasion of Claudius in 43 AD. Though Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britannia occurred eighty years earlier in 55 and 54 BC, there is archaeological evidence that his invasion was not a momentary diversion from his conquest of Gaul. Instead, it was his effort to establish the dynasties of the most powerful tribes of southeast Britain who would swear their loyalty to Rome.

Statue Julius Caesar Displayed at Louvre Museum

The next series of posts will summarize historical and archaeological evidence of possible events that led to the Roman invasion of Britain in 43 AD. The military expedition of Julius Caesar into Britannia, occurring eighty years earlier, sets the backdrop for Rome’s foreign relationships with the Celtic rulers in Britannia. The political unrest of tribal rulers competing for Rome’s favor sets the stage for the Curse of Clansmen and Kings series. The series follows the epic odyssey of Catrin — destined to become a warrior queen of her Cantiaci kingdom — and her Roman lover, the great-grandson of Marc Antony (Marcus Antonius).

Caesar’s Invasion of Britannia

Planning

In 55 AD, Caesar decided to invade Britannia because powerful chieftains had secretly aided the Gauls in their war against Rome. Most of Caesar’s limited information about Britannia was derived from traders. Thus, he wanted to learn more about the island’s size, the harbors suitable for landing larger vessels, and the names of tribal leaders and their military state and organization. He dispatched Commius, King of the Atrebates tribe from Gaul, to impress upon the British leaders that they needed to cooperate with the Romans. A formidable general, Caesar threatened to visit them in person to assure their alliance.

Collapsed Wall of White Cliffs Near Dover 2012

As Caesar prepared his fleet to invade Britannia from a port near modern-day Boulogne France, traders informed British chieftains of his planned military expedition. Some Celtic tribes from southeast Britannia (modern-day Kent) sent envoys promising to hand over hostages to Caesar and to acknowledge Rome’s suzerainty over them. In essence, the Celtic leaders promised Caesar that Rome could control their foreign relations as a vassal state in exchange for allowing them authority over their internal affairs. Encouraged by the willingness of the Celtic rulers to negotiate, Caesar allowed the British envoys to return home.

Frieze of Roman Warship

Roman Landing

In late summer at midnight, Caesar disembarked eighty ships that were sufficient to transport two legions (about 10,000 soldiers). He left instructions for eighteen ships to transport the cavalry further north on the coastline. When his warships first reached the Britannia shores early the next morning, the whole line of hills (Dover Cliffs) was crowned with armed warriors. There was little space between the sea and rising white cliffs from which the Celtic spearmen could easily hurl their weapons down. As landing was impossible, Caesar directed his fleet to sail seven miles north to an open, flat expanse of shingled beach. The Celtic horsemen followed Caesar’s ships on the hilltops as they sailed up the coastline.

Replica of Ancient Roman Ship

Battle with Celtic Horsemen

Further north, Caesar’s forces found getting ashore to be a difficult feat. Roman soldiers were forced to jump overboard without knowing the depth of the bottom. Laden with heavy equipment, Roman troops waded through the channel’s shallow waters to get ashore. While trying to maintain their footing in the surf, the Roman infantrymen confronted Celtic horsemen that could outmaneuver them on land.

Celtic Horned Helmet Found at River Thames Date 150-50BC

At first, the Roman legionaries panicked. Then Caesar ordered the warships to hurl sling-stones, arrows, and artillery at the Celtic horsemen to drive them from their point of vantage. An eagle-bearer from the Tenth Legion emboldened his comrades by leaping into the water and shouting, “I, at any rate, shall not be found wanting in my duty to my country and general.”

Probable Site of Caesar’s First Landing Shingled Beach near Deal UK

The battle was fiercely contested. The Romans found it impossible to maintain formation, while the Celtic warriors seized every opportunity to dash in with their horses at isolated groups of soldiers struggling to get ashore. Once Caesar firmly landed the infantrymen, they charged and routed the Britons. After the Celtic army was vanquished in battle, the tribal rulers again sent envoys to Caesar and returned Commius, the King of the Atrebetas who had been originally dispatched to herald Caesar’s coming. The Celtic chieftains again promised to give Caesar hostages and to yield to his orders.

(To be continued)

References:

Julius Caesar, translated by F. P. Long, 2005. The Conquest of Gaul. United States: Barnes & Noble, Inc.

John Manley, 2002. AD 43—The Roman Invasion of Britain. Charlston, SC: Tempus Publishing Inc.

© Copyright March 28, 2013 by Linnea Tanner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.