Mary Jane Walker's Blog: Adventures at Snow Farm Part 1 – Skiing with a broken shoulder! , page 38

April 4, 2018

An Easter Break in Brooklyn: Photos and writeup by NZ author Mary Jane Walker

This year, I decided I was going to revisit Red Hook, a waterfront district of Brooklyn. I discovered the charms of Brooklyn and its waterfront enclave of Red Hook just after Donald Trump was elected president. I had no time for the hysteria and street protests and wanted to go somewhere old-fashioned.

As this line of photos suggests, Brooklyn is just across the water from Manhattan. The bridge is, of course, the Brooklyn Bridge.

Brooklyn is probably New York’s oldest suburb, founded by the Dutch in the 1640s not long after New York itself. It has a lot of charm..

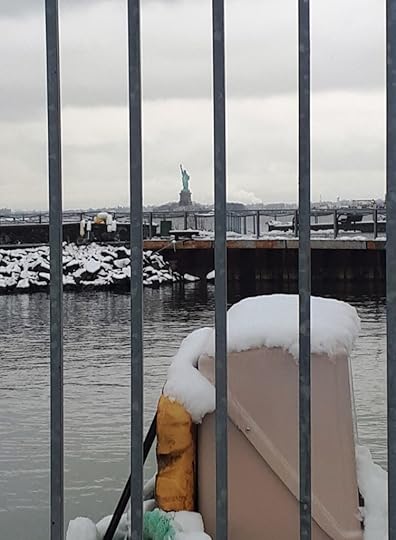

Back at the time of the election, I had taken a boat-sightseeing tour of the harbour for the day and stopped at Fair Way Cafe, Red Hook. The food, the done-up wharf area, the brick buildings and the renewed warehouse area fascinated me, along with being so close to Manhattan and having a view of Lady Liberty.

Red Hook port was the busiest freight port during the 40s and 50s and was inhabited by seafarers from all over the world, even Norway.

I had scored a room in Airbnb at a reasonable rate in Coffey St, next to the murals depicting life in the area. My editor Chris Harris had begun corresponding with a writer from Red Hook called Russell Bittner and his partner Elinor Spielberg. By chance or cosmic concern they lived at a house across the way in Coffey Street as well.

Bike lanes are everywhere. They are so extensive you could bike to Manhattan, and many do.

When I first arrived the bus driver took a detour and said it was a shooting and went around Coffey St. It was a movie shooting an episode of law and order and the movie set guarded by the NYPD

I received a random invite to a music evening called Woman of Color, featuring Ki and Sonic at a club called Nublu 151.

It was rap and great intimate music.

I got familiar with baseball — the Brooklyn Dodgers.

A weekly bus and underground pass is 32 dollars and the ferries from Ikea Red Hook are free during the weekends.

I walked to the Brooklyn Historical Society and saw the sandstone (‘brownstone’) houses and churches. This area, which has now been urbanised for four hundred years, was one of the first to take up arms in the American War of Independence.

The ferry being free, off I went wondering and wandering with my photography on the only fine and sunny day. I went to Central Park in Manhattan and photographed all kinds of remarkable scenes.

The next day it went from a comparatively warm 57 deg F to snow — wow!

And such was Easter 2018!

The post An Easter Break in Brooklyn: Photos and writeup by NZ author Mary Jane Walker appeared first on A Maverick Traveller.

February 25, 2018

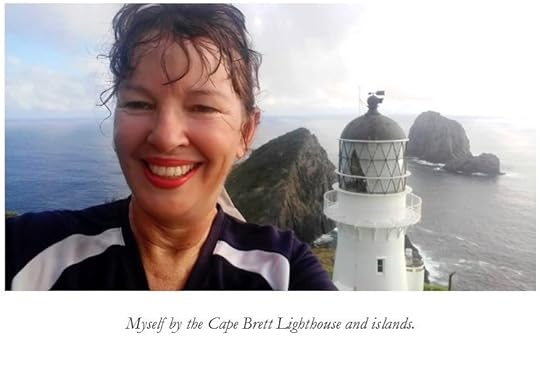

Cape Brett: Hiking to the Birthplace of Aotearoa

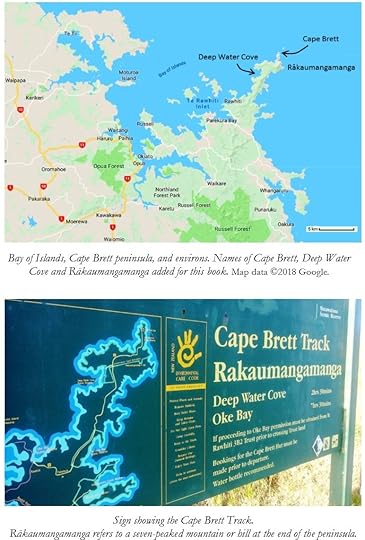

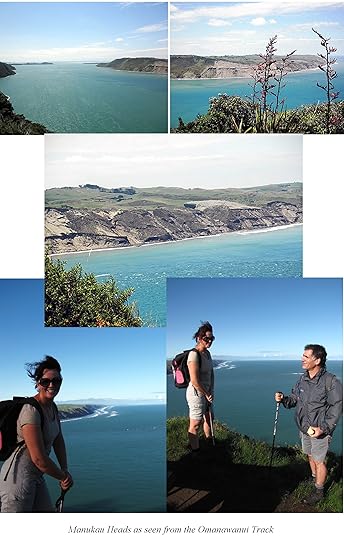

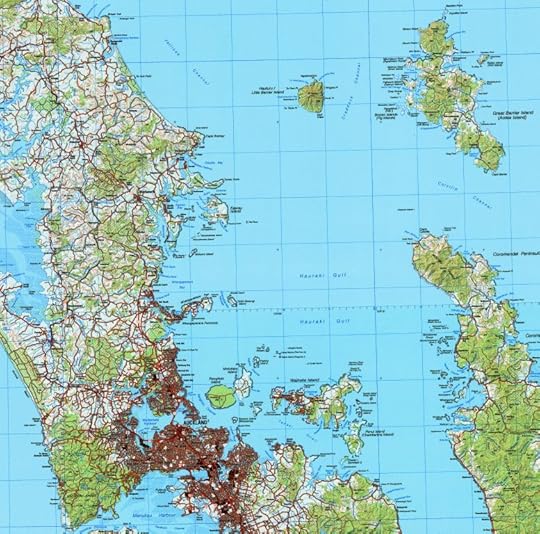

One of the most famous places in New Zealand is the Bay of Islands. As its name suggests, this gorgeous bay on the east coast of Northland, due north-east of Waipoua Forest, is full of islands. It is shielded from cold southern winds, any that make it this far north, by Cape Brett. I’ve added a map and some photos from my book A Maverick New Zealand Way, so that’s why one or two of the captions refer to a book!

The Bay of Islands is fairly touristy these days, though not as touristy as some other places in New Zealand. For a long time, the Bay of Islands attracted domestic holidaymakers, as well as wealthy visitors intent on catching big fighting fish such as Marlin. The American author Zane Grey wrote about the place in the 1920s, popularising it in a book called Tales of the Angler’s El Dorado.

Before that, the Bay of Islands was the seat of New Zealand’s very first capital at Russell; and is the site of the Treaty House, where the founding Treaty of Waitangi was signed on the 6th of February, 1840, between Queen Victoria’s representatives and a number of Māori rangatira, or chieftains.

With global warming, the area north of Auckland is slated to become more tropical. It is lashed from time to time by cyclones, and this is likely to get worse. However, between storms, it’s a lovely part of Polynesia. That’s particularly true of sheltered east coast areas like the Bay of Islands.

The Cape Brett peninsula is also of great significance to Māori, as the supposed branching-off place of the seven ancestral ocean-going canoes (double-hulled and more like catamaran yachts) on which the ancestors of the Māori were said to have arrived from Hawaiki, that is to say, Eastern Polynesia, roughly one thousand years ago.

Aotearoa is the Māori word for New Zealand, or for Māori New Zealand. It was coined in the nineteenth century as British colonisation forged a greater sense of common identity among separate tribal groups.

There are two words for tribe in New Zealand Māori, iwi and hapū. The word iwi refers to a group of distant relatives made up of several hapū, or clusters of close relatives. Iwi lineages customarily date back to the founding canoes; hapū identities are more recent. The iwi was the largest unit of government to exist in New Zealand before the coming of European colonisation.

Thus, the Cape Brett peninsula is the place where Aotearoa is supposd to have been born: albeit ironically in the form of the parting of the canoes and the establishment of the iwi system.

In the traditional story, the vessels arrived at the peninsula and then split up to settle different parts of New Zealand. The Māori of Northland, the Ngāpuhi, trace their ancestry to people who were on three of the seven canoes: the Ngātokimatawhaorua, the Māmari and the Mataatua.

I stopped in first of all at the Bland Bay Motor Camp near Whangaruru, which Is toward the bottom right of the map just above. This area, south of the Cape Brett peninsula, is a refuge from the busier and more commercialised Bay of Islands proper. The Bland Bay Motor Camp is run by the Ngāti Wai iwi.

I went for beautiful walks around Bland Bay and nearby Puriri Bay. I stayed there for three days just relaxing, but then I thought that I had to take up the challenge of hiking the length of the Cape Brett peninsula toward its jagged, seven-peaked tip known as Rākaumangamanga.

The Māori word rākau means tree or stick, while manga means branch. Doubling up the word manga adds emphasis. The name is associated with the the branching-off of the canoes, and maybe the the branch-like shape of the peninsula as well.

The seven peaks of Rākaumangamanga represent the original colonising fleet.

However many vessels there really were, and whether they all came at once or not, the legend’s theme of a deliberate and organised process of colonisation is backed up by modern research.

The ancestors of the Polynesians lived on islands off the Asian coast, where they were related to other island peoples such as the majority of the inhabitants of Java, and the indigenous people of Taiwan.

The Polynesians gradually spread eastward into the Pacific Ocean and became very accomplished and deliberate ocean navigators and colonists. The islands of New Zealand were merely the last and largest islands to be colonised by Polynesian people; who also frequently called themselves Māori, or a similar word. This meant ordinary or common, as opposed to other peoples that the Polynesians sometimes met such as the Europeans who began arriving, in earnest, in the eighteenth century.

The islands of New Zealand would have been the most challenging to colonise, since they were well south of the main latitudes of Polynesia, with different wind patterns and colder seas. So, the Māori colonisation of New Zealand could have required a particularly organised expedition, or series of expeditions.

With regard to hiking the Cape Brett peninsula—where the whole human history of New Zealand is thus said to have begun—the first thing to mention is that the track takes about eight hours from start to finish.

There is an excellent Youtube video called ‘Cape Brett Track – Living a Kiwi Life – Ep. 45’, which has been recommended by New Zealand’s Department of Conservation, and which gives a very good idea of what the track is like, including the exposed bits which may not be for everyone.

In several places it gets gnarly and exposed, with big drop-offs to either side, though the views are terrific.

The track is graded as ‘advanced’ in its Department of Conservation brochure, a grade which falls short of mountaineering but does mean that it is a good idea to be kitted out with boots and hiking poles and proper tramping gear all round, along with having a reasonable level of fitness and a head for heights. The track is not open to mountain bikers, because it is actually too steep and (potentially) dangerous for that.

There are several carparks at the beginning. A lot of cars get robbed, though you can pay $8, currently, for more secure parking. The first section runs along Māori communal land, and then you get into conservation areas. There is a stream and a water tank half along the track, but carrying water is recommended. I would recommend carrying water purification pills as well.

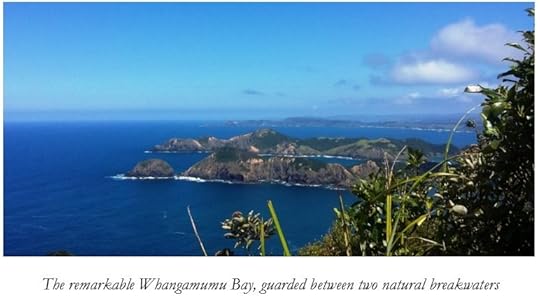

You can make side-trips from the main track to the old Whangamumu Bay whaling station and other areas of interest. Whangamumu Bay is well worth it, a white sand beach sheltered by two peninsulas that act as natural breakwaters.

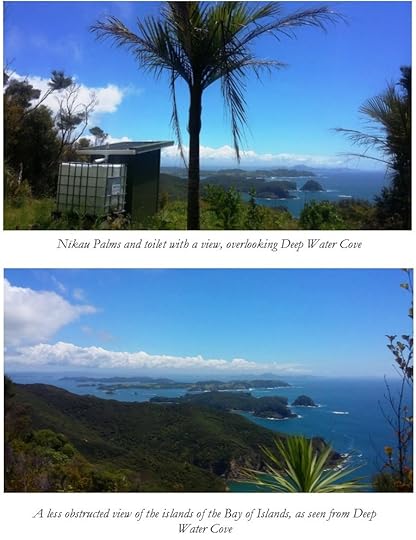

Further along, you get to Deep Water Cove on the western side, which has terrific views of the Bay of Islands. This also be enjoyed from a strategically-located toilet, though only with the door open of course.

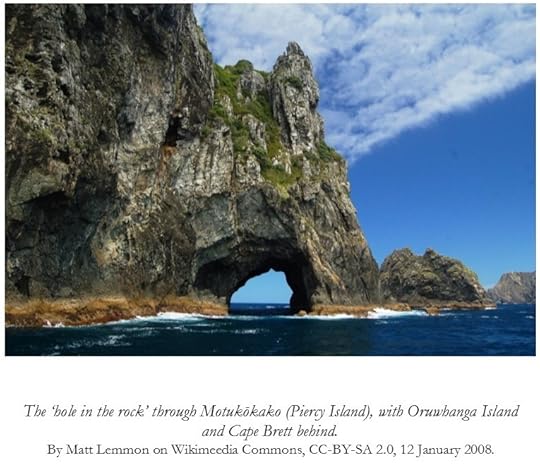

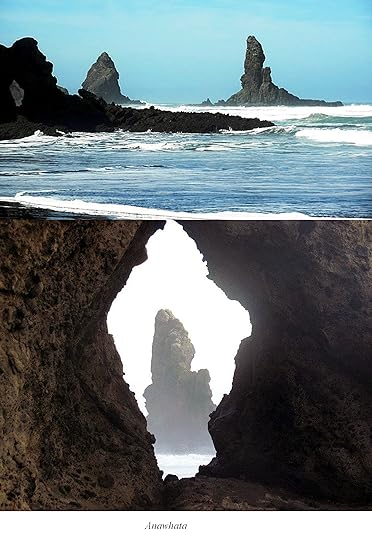

For those who don’t want parking hassles or too long a walk, it’s possible to take a water taxi from various Bay of Islands localities such as Russell, Paihia and Oke Bay to Deep Water Cove or Cape Brett. One advantage of taking the water taxi all the way to or from Cape Brett is that if sea conditions allow, the taxi may go through the famous ‘Hole in the Rock’ at Motukōkako (Piercy Island) just off Cape Brett.

The water taxi costs $50 per person to or from Cape Brett at the time of publication, or $40 to or from Deep Water Cove, but minimum per-boat charges apply, i.e. it must have a quorum of passengers (about five), or else the rate per person goes up. Details are on the web here.

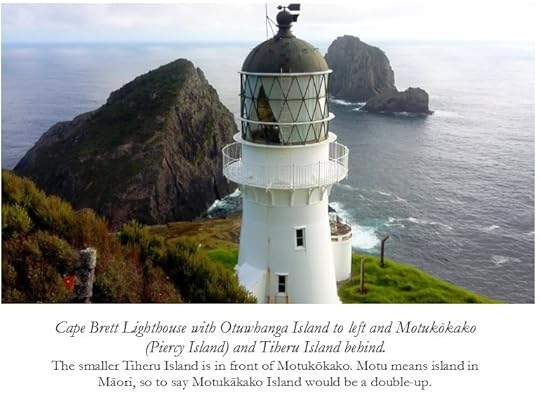

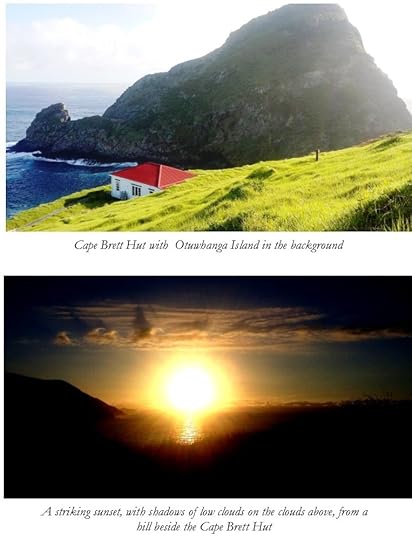

Near the Cape Brett Lighthouse is the so-called Cape Brett Hut, overlooked by the massive looming presence of Otuwhanga Island. Rather flash as huts go, it used to be the lighthouse keeper’s house, of course.

It’s necessary to book the hut in advance if you want to stay there. It has a combination lock, and you get the combination on booking. Currently, the fee is $15 a night for an adult (18+), half-price for those 11-17. Younger children are free.

I saw a stoat running along the track. Fingers of land like the Cape Brett peninsula are obvious candidates for being fenced off and made predator-free. It’s a sign of DOC funding stress that they aren’t.

There is also a fee for walking across the Māori land, which goes toward the maintenance of the track on that section. The fee is currently $40 per adult or $20 per child. The fee is paid on the Department of Conservation website. The website capebrett.co.nz, which also provides the details on the water taxi, notes that the arrangements for paying the fee on the DOC website are rather confusing and provides helpful tips on how to get it right.

The fee can be avoided by taking the water taxi both ways, though this means missing out on a portion of the track. In an ideal world the Māori landowners would be fully compensated by DOC, but I suspect that neither the department’s budget nor, perhaps, its present organisational capabilities run to that.

The post Cape Brett: Hiking to the Birthplace of Aotearoa appeared first on A Maverick Traveller.

January 27, 2018

Pacific Parallels: Auckland, Vancouver, San Francisco

PEOPLE are perpetually fascinated by history as it might have been: by parallel universes and the plotlines of films like Sliding Doors.

In that respect, there are a number of curious parallels between the Canadian city of Vancouver, British Columbia (BC), and Auckland, New Zealand, a city across the Pacific. “Arriving in Vancouver on a misty humid evening,” wrote one Kiwi visitor in the 1950s, “I thought it could have doubled for Auckland even down to its North Shore, which is always lit up at night”

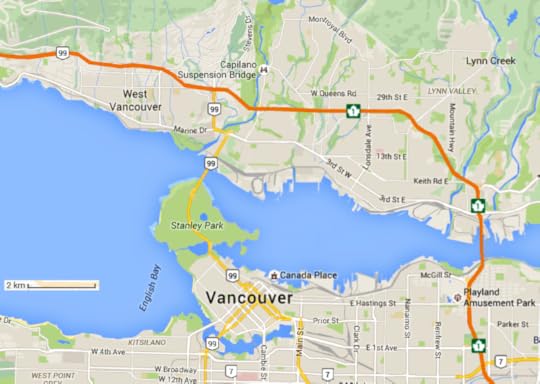

Just how parallel is Auckland? Consider this. The city centre is on the south side of a drowned valley called the Waitematā, Māori for ‘sparkling waters’; an arm of the sea that closely resembles Vancouver’s Burrard Inlet.

A series of narrows separates downtown Auckland from its suburban North Shore. To the south of the city there is a muddier estuary, known as the Manukau. Between the two there are grid-pattern streets.

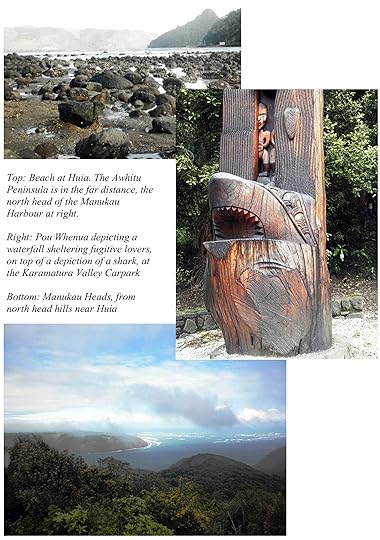

The city includes a surprisingly wild coastal nature-park north of the Manukau Heads, where The Piano was filmed; a parallel to the mountains, parkland and skifields of Vancouver’s North Shore.

Auckland is ethnically diverse, and its indigenous culture is conspicuous. The climate is rainy, and there was a building scandal in which thousands of apartments leaked and rotted. At the same time the city has been dogged by a runaway property-market bubble, just like Vancouver.

Off the eastern shore, there is a series of ecologically sensitive islands shielded from the wider Pacific by Great Barrier Island and the Coromandel Peninsula, both of which are still mostly covered in native forests. The parallel here is with Vancouver Island and other islands along the BC coast; a parallel that extends to Auckland’s rugged western shores as well.

Founded in Vancouver, Greenpeace had its Rainbow Warrior blown up in Auckland Harbour.

And both cities used to be British, of course.

Parallels – and Differences

Such are the parallels, which alone would make Auckland an interesting place for the Vancouverite to visit and vice versa. But there are differences too.

Both cities are ethnically diverse. But Auckland is even more diverse than Vancouver. Alongside a large Asian community, New Zealand Māori and their Polynesian relatives make up an additional quarter of Auckland’s population.

Such a First Nation presence is almost unique in a large Western city, as opposed to a rural district. Auckland is thus not only the largest city in Polynesia—much larger than Honolulu—but also the largest Polynesian city.

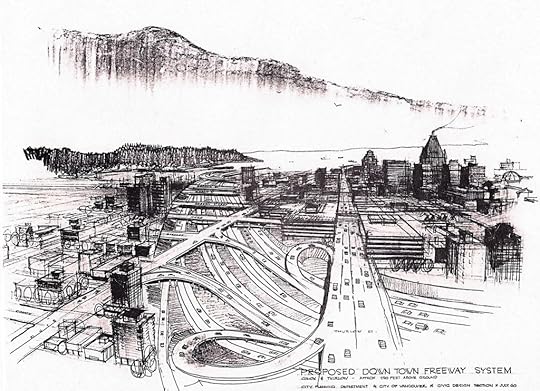

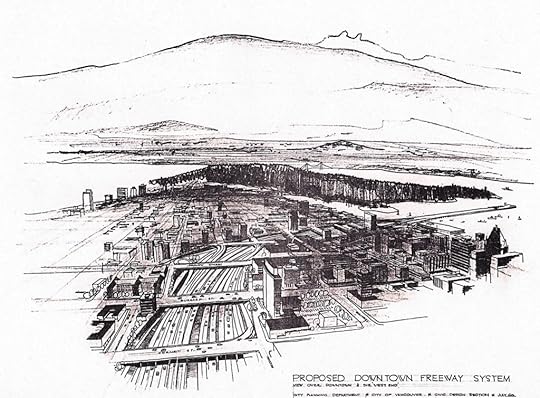

Another difference lies in transport policy. A story by John Mackie, published in the Vancouver Sun in January 2008, describes a 1960s scheme for a downtown freeway junction in Vancouver, of which a couple of sketches from back in the day (also depicted in Mackie’s story) are shown here.

As Mackie put it,

“The Vancouver Sun’s files are brimming with stories about politicians and planners who wanted to build all sorts of freeways and transit systems, but failed. Some of the plans look interesting, others are simply nuts. . . .

“The most mind-boggling plans were for the freeway systems in the late 1950s and 1960s. If they had been built, Vancouver would have been a very, very different place.

“The wackiest proposal was to build a giant trench through downtown. . . .

“A 1960 drawing of the big ditch at Comox and Thurlow shows a dizzying complex of roads and cloverleafs. Try to imagine the Trans-Canada Highway in Burnaby plopped down in the middle of the West End, only bigger (it was eight lanes wide, and 10 metres deep).

“It’s hard to imagine what the ditch designers were thinking. They planned bridges — bridges! — on Nelson, Barclay, Haro, Robson, Georgia and Hastings streets . . . .

“Looking back from 2007, the big ditch looks completely ludicrous . . .”

The junction was intended to serve a road bridge across the Burrard Inlet in the downtown area, which would have become the main crossing for the Trans-Canada Highway. But no such bridge would ever eventuate

As built, the Trans-Canada Highway gives downtown Vancouver a wide berth, crossing the Burrard Inlet further inland. A cloverleaf just south of the bridge finds itself in an industrial area, rather than in the middle of town.

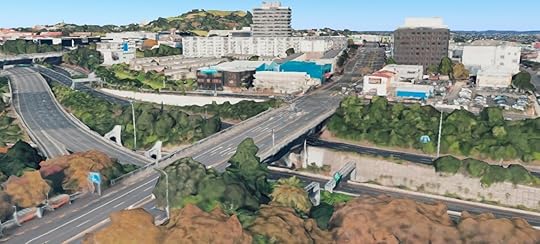

But in Auckland, the equivalent downtown bridge and motorway nexus did get built.

(NB motorway and freeway mean the same thing, one a UK/NZ usage, the other US/Canadian).

In the 1940s, planners intended that New Zealand’s main national highway should cross the Waitematā harbour well inland of downtown Auckland. However, in the 1950s, the decision was taken to build the main road bridge downtown.

Open for traffic in May 1959, the downtown Auckland Harbour Bridge was initially four lanes wide, one more than Vancouver’s Lions Gate Bridge. But during the 1960s, the Auckland Harbour Bridge was widened to eight lanes of motorway. This stimulated the development of a colossal motorway junction, bigger than any in the neighbouring, much larger country of Australia (!)). In fact, it resembled nothing so much as what had been originally planned for Vancouver.

However, because everything started out narrow in Auckland and then got widened, the Aucklanders were not told upfront what they would actually get.

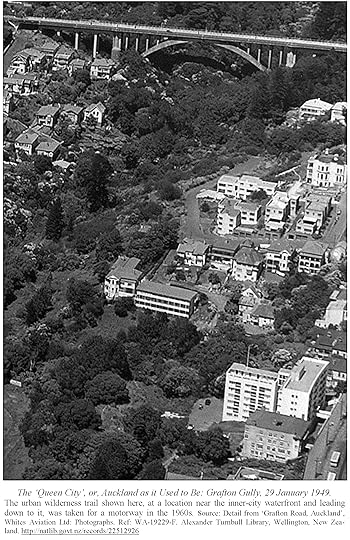

For instance, in the 1960 newsreel Expanding Auckland , locals were told that “The Southern Motorway will sweep up over Broadway at Newmarket, go down under Mountain Road. A tunnel will take it beneath Symonds Street, and it will come out in the great roundabout in Newton Gully.”

This was not what happened! In fact, large areas of precious inner-city parkland were either paved over or severed from the central business district.

As the late Australian urbanist Paul Mees wrote in his book Transport for Suburbia (2009), New Zealand’s environmental concern has not extended to its cities! In spite of its beautiful natural setting, Auckland has been trashed by motorways.

A massive downtown motorway junction in Auckland is the bullet that a similarly scenic Vancouver dodged.

In Auckland, you can see Vancouver as it might have been. And in Vancouver, you can see Auckland as it might have been.

There is also a similar if less exact parallel to San Francisco in California. San Francisco is a coastal city where plans for a massive downtown freeway interchange were also resisted; and where some flyovers that were built were torn down after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, and not replaced. Thus Auckland is also to some extent San Francisco as it might have been — and vice versa.

The wild western shore

Returning to happier parallels, both cities have an amazing endowment of wilderness right on their doorsteps.

There are many contenders for the title of the jewel in Auckland’s crown, with most favouring the sheltered eastern coast. But others prefer the windy west, with its leathery vegetation and black-sand surf beaches.

And, in particular, the vast Waitakere Ranges, which form the north head of the Manukau harbour entrance.

At this point in a tour around Auckland, another parallel to San Francisco suggests itself.

If on a misty night Vancouver is just like Auckland, so the Manukau Heads bear an uncanny resemblance to San Francisco’s Golden Gate.

But there is no bridge across the Manukau harbour; and no city by its dramatic entrance. Indeed, this wild western extremity often seems as empty as in The Piano, despite its current proximity to a city of a million and a half.

From Auckland, the Manukau Heads are reached most easily from the western suburb of Titirangi, already under primordial forests that stretch to the sea. Under these, it’s possible to walk a complete loop from Titirangi to the sea and back to another suburb via the Hillary Trail, named after the mountaineer.

The Hillary trail offers the best view of the Manukau Heads, and also visits several west coast beaches, including Karekare, where the piano came ashore.

Sadly, the kauri dieback disease, an introduced pest, is starting to limit visitors’ access to the western forests, and access may be restricted further in future.

A city not to overlook

Although many tourists come to New Zealand, they often head straight for the remote wilderness and miss out on Auckland.

In fact, Auckland is an interesting place with many parallels to cities of the North American west coast. It’s also just as old and historical, if not more so in a number of ways.

Auckland was founded in 1840, as the first proper colonial town and seaport in New Zealand. This makes Auckland a few years older than Seattle, Portland, or any Anglophone settlement in California, and about forty-five years older than Vancouver. In fact, Auckland is only a few years younger than Chicago.

Auckland’s strong indigenous culture stretches back further. Over fifty green volcanic hills in greater Auckland, many of them terraced by Māori to make them into more useful strongholds have now been submitted for the first step on the road to World Heritage status.

And that’s as good a place as any to round off what is, of necessity, a very quick introduction to an unreasonably neglected city, skipped through by tourists and treated in a cavalier sense even by New Zealand’s own Wellington-based bureaucracies.

Yet Auckland is clearly a city of some interest, with its own attractions and with many curious parallels to cities and districts in the US/Canadian West Coast, as well as points of difference.

Notes: The 1950s quote in which Vancouver is said to resemble Auckland on a misty night is by Peter Blish, as published in The Weekly News (NZ), 29 April 1953, p. 22. The Vancouver Sun article by John Mackie is ‘What Might Have Been’, published 19 January 2008 but written before the New Year.

The post Pacific Parallels: Auckland, Vancouver, San Francisco appeared first on A Maverick Traveller.

January 17, 2018

Auckland’s Great Barrier Island (not the Great Barrier Reef)

THE largest of Auckland’s Hauraki Gulf Islands is Great Barrier Island, also known as Aotea, the island of the white cloud or the shining sky. When I get tele-marketing calls selling holidays on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, I tell them, ‘We have our own Great Barrier Island.’ I don’t tell them it’s not so big!

Nor is it as polluted. Great Barrier Island comes in near the top of coastal destinations rated by National Geographic in 2010:

“Only 55 miles of ocean separate Great Barrier Island from cosmopolitan Auckland, but given how little the two places have in common, the distance seems much greater. With less than 1,000 permanent residents, more than half of its land area administered by New Zealand’s Department of Conservation, and fewer introduced species than elsewhere in the country, the island is in good shape ecologically and will likely remain so for a while.”

As of the time of posting of this blog, you can see the article here. Located north-east of Auckland on the edge of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park, New Zealand’s ‘National Park of the Sea’, the island can be reached by a 4-hour ferry ride, or a scenic half-hour flight.

Some time back, I bought shares in a bach (cabin) there along with a few other people. Over the years, I’ve loved going over to the island and tramping the 621-metre high Mount Hobson, also known by its Māori name of Hirakimata, as well as visiting other parts of the island. There are no possums, stoats or ferrets on the island, which means that despite the few remaining rats the forest is largely untouched.

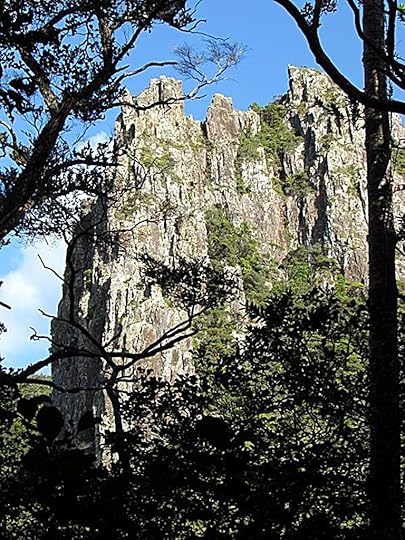

The island is beautiful, with jagged green mountains like those seen on Polynesian islands in the tropics and huge nīkau palms – the only palm endemic to New Zealand (in two species) and the southernmost palm in the world, growing to 44 degrees south. Furthermore, though handy to Auckland, Great Barrier Island / Aotea has no reticulated electricity, so you have to rough it a bit. It doesn’t get a lot of day-trippers either. It used to be that you couldn’t get much cellphone reception either, but now you can in most places. Altogether, it is the perfect place to get away for a proper break.

Known as the Barrier for short, the island has a history of mining and is riddled with disused mineshafts. This is something it has in common with the nearby, equally rugged, Coromandel Peninsula.

Conservation Efforts

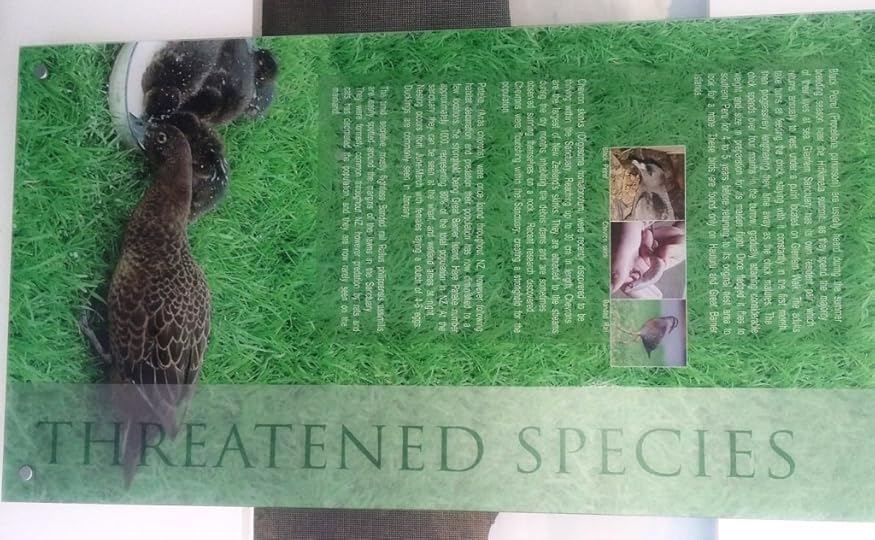

To a large extent, New Zealand conservation revolves around the control of introduced pests. For instance, an estimated 70 million individuals of the introduced Australian brushtail possum species, trichosurus vulpecula – ‘the little foxy one with the brush-tail’, which makes it sound extra cute – are thought to consume 21 thousand tonnes of New Zealand bush a night (brushtail possums are nocturnal). For the story behind these facts and figures, see the New Zealand Department of Conservation flier A Pest of Plague Proportions.

In New Zealand, the brushtail possum eats all forms of vegetation and also eats eggs and young birds; as do rats, ferrets and stoats. On top of that. brushtail possums spread diseases such as bovine tuberculosis, putting the farmer at risk. So, the introduced species of possum has few friends in New Zealand.

Because Great Barrier Island is so isolated, brushtail possums never made it ashore and this makes Great Barrier something of a special place. On the other hand, rodents are there, as they are almost everywhere in New Zealand.

At the moment there are plans to exterminate all the rodent pests on nearby Rakitu or Arid Island using brodifacoum, so that the island can be re-populated by native species, which of course evolved in the absence of ground-dwelling mammals. There is some opposition to this, and there’s a story on the controversy here.

Views and Pools

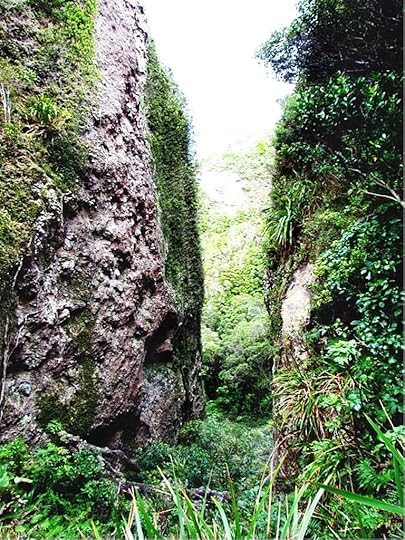

Several of the most popular destinations on the island are on a scenic trail known as the Aotea Track. These include the peak of Hirakimata, and Windy Canyon, a Lord of the Rings filming site, I walked a part of the Aotea Track in January 2015 with my friend Rose and her partner, Daniel. We hiked along it to the top of Hirakimata, where there are amazing 360-degree views of the island. There are also free hot pools located on a section of the track that leads from the Whangaparapara Road to Hirakimata: the Kaitoke hot pools.

Once upon a time Rose and I also tramped the tramline track in the middle of the island and found a well-formed bath with hot water flowing into it that had been carved into the rock by a Victorian gentleman, at a place called the Peach Tree hot springs. The bath is at a hidden location, now somewhat overgrown and quite hard to find, just above the better-known and more accessible Kaitoke hot pools.

I later re-did that walk by myself and visited Mt Heale Hut, which is a back-country hut with all kitchen implements, pots, pans, and even a dish brush supplied, and a view to die for.

Conservation Efforts

I read in a December 2014 New Yorker article I found at that Mt Heale (‘ The big kill: New Zealand’s crusade to rid itself of mammals ‘) that New Zealand conservation was indeed to a very large extent a matter of calling in the exterminators.

The New Yorker article gives a rather negative impression of the humanity of this approach. However, a more recent (paywalled) article in the New Zealand Listener by Rebecca Macfie, ‘ Natural born killers ’, 26 November 2016, makes clear that many of the introduced predators in New Zealand experience boom and bust cycles; if they are not poisoned, they will starve, after first eating as much of the native bush and wildlife as possible.

Certainly, our methods are working to the extent that the funding and resources (often volunteer resources) are available. Great Barrier Island had been partly cleared of its trees by pests such as possums, and is only now regenerating after all the work the volunteers have done in wiping out the pests. In the long run the scientists would prefer a species-specific contraceptive, but so far that has not yet been developed. Another article by Rebecca Macfie in the 3 December 2016 issue of the New Zealand Listener, Saving our species ‘, not paywalled at the moment, follows up on such long-term solutions.

Alongside government conservation efforts, at Port Fitzroy, on the western shore of the island, there is also a private conservation sanctuary called Glenfern, founded by the late Auckland yachtsman Tony Bouzaid.

When I was at Port Fitzroy in 2015, I hiked up to the local entrance of the Aotea Track. It turned out that I couldn’t tramp any further because of storm damage that had washed the track away! It was very sad, as they had upgraded all the tracks on Great Barrier Island in 2014 ready for tourism, and on the day the minister arrived to open them, a great storm came through the area and destroyed a lot of the hard work that had been done. However, the track and the huts re-opened in 2016 so now they are bouncing back.

In 2015, the New Zealand Government created the Aotea Conservation Park on the island. The Park’s advisory body, the Aotea Conservation Park Advisory Committee (ACPAC), is now lobbying for the Aotea Track to be proclaimed a Great Walk, which would give it the same status as the Milford Track and the Routeburn Track.

Lastly, let’s no forget the marine life!

My Latest Visit

I spent New Year 2017 / 2018 on the Barrier, and I’m pleased to say it’s better than ever. Some of the photos in this blog are from my latest trip. I even swam with dolphins at Okupu (Blind Bay)! It was also great to see new community artwork.

I went to a fair at Claris, the little township next to the island’s airport, which was being organised to raise money for the Aotea Family Support Group Charitable Trust. At Claris, a world champion breaks singer from New Zealand was performing. I missed out on the Great FitzRoy Mussel Fest and FitzRoy Family Festival, held at Port Fitzroy, however.

Here are some videos I shot, of a storm at Awana Beach (where the feature image that leads this blog was taken), and the breaks singer at Claris.

Starry Southern Skies

To round off, Aucklanders have long marvelled at theBarrier’s starry skies, criss-crossed with clearly visible wandering satellites and streaked by meteors. A small population, lack of mains electricity, and hardly any streetlights, all help to keep the skies desert-dark even though the island isn’t really all that remote.

In 2017, Great Barrier Island was awarded Dark Sky Sanctuary status by the International Dark Sky Association (ISDA), which will encourage astronomically-minded visitors. There are twelve IDA Dark Sky Reserves including one at Lake Tekapo in New Zealand, but only three Dark Sky Sanctuaries, astronomical viewing sites which are even more pristine. The three Dark Sky Sanctuaries are at Cosmic Campground in New Mexico, at the Elqui Valley in northern Chile, and now at Great Barrier Island as well.

The summer is normally the time to go to Great Barrier, because pohutukawa trees are everywhere and they blossom at Christmas. It’s also the summer holidays, of course. The locals hope that Dark Sky Sanctuary status will increase winter tourism as well, since in winter the nights are longer. At that time of year, it’s also possible to see the core of the Milky Way, which lies in the constellations of Scorpio and Sagittarius; whereby the Milky Way comes to look like a poached egg seen side-in rather than just a band of stars.

These constellations are most visible at mid-year and are more easily seen from the southern hemisphere than the northern because the nights at that time of year are longer in the south, it being winter downunder. The view from Great Barrier should rank with the clearest in the world, and of course one advantage of Great Barrier as a Dark Sky Sanctuary is that it is, as National Geographic says, only 55 miles (90 km) from the big city of Auckland.

The post Auckland’s Great Barrier Island (not the Great Barrier Reef) appeared first on A Maverick Traveller.

December 27, 2017

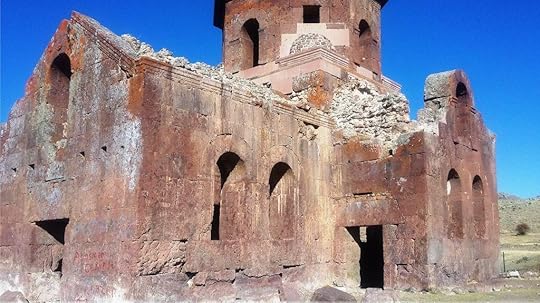

On a Kiwi Visa in Cappadocia

This October, I arrived in Turkey for the second time in my life, landing at Istanbul. Almost immediately, I could see that a lot had changed. The prosperous and secular country I visited last time was in a slump. Islamic headscarves, previously rare, were also common.

A combination of terrorist attacks and political upheaval had slashed tourism numbers and thrown the wider economy into a tailspin. Just before I arrived, the news media announced that visas would no longer be given to US visitors. This was because the USA was harbouring the cleric Fethulla Gülen, who the government of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan regarded as a coup plotter.

(Erdoğan’s opponents regard him as a would-be dictator and a ‘neo-Ottoman’, intent on carving out a sphere of Turkish influence in all the old provinces of the former Ottoman Empire ruled from Istanbul’s Topkapi palace; provinces such as Israel and Palestine, Egypt, and Syria. Certainly it is true that Ankara,the capital of modern Turkey, now takes a more independent line from Washington than it used to, though whether that is a bad thing or not remains to be seen.)

The visa ban was partly lifted in November, though it still takes Americans about a month to have one approved, apparently. The State Department continues to advise against travelling to Turkey.

Ironically, this means that American’s can’t easily spend Christmas this year in the land of Santa Claus. I’m not referring to a fictitious character at the North Pole, but to a real person who lived and walked in the land that is now Turkey. I’ll explain all that a little further on!

Luckily, I had a New Zealand passport, so I was alright. There are a lot of advantages to travelling on the passport of a country that hardly ever makes it into the news.

Here are some pictures I took in Istanbul. I’m going to write about Istanbul at more length in another blog. The rest of this blog, however, will be about a different topic: my experiences in Cappadocia.

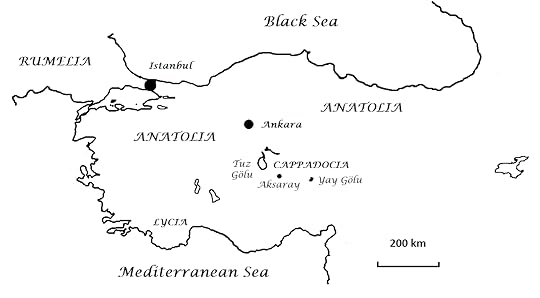

Cappadocia, in Anatolia

Cappadocia is a region in central Anatolia: the great peninsula between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. Modern Turkey consists of Anatolia plus a small part of Europe.

Before it became the heartland of Turkey, Anatolia was one of the last holdouts of the Roman Empire.

Westerners think that the Roman Empire fell in the 400s CE, when the barbarians occupied Rome.

In fact, the fall of the Roman Empire was more of a gradual whittling-away of territories, which continued for another thousand years.

After the fall of the West, Constantinople (now Instanbul) became the capital of the Empire, which became primarily Greek speaking from the 600s CE onward but nonetheless continued to call itself Rome or the Roman Empire, right up to the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453 CE.

(The name we now apply to this eastern survival of ancient Rome – Byzantium, or the Byzantine Empire, from another old name for Constantinople – wasn’t coined till the 1500s. Nobody ever referred to the Byzantine Empire when it existed. It reflects a Western view that the ‘real’ Roman Empire ended when Rome fell.)

Egypt and Syria were lost to the Moslem Arabs in the 700s CE, and most of Anatolia was lost in 1071 to the Seljuk Turks, a dynasty who came before the Ottomans. The Seljuks called their part of Anatolia the Sultanate of Rum, that is, of Rome.

As that name suggests, the Turks regarded themselves in those days as inheritors of Rome, of which they were generally in awe, rather than its destroyers. They saw themselves as moving in to take over in a simlar fashion to the Moslem Mughal rulers of India, who built the Taj Mahal and a whole lot of forts but otherwise didn’t stop India from being India. Thus, in 1453, the Ottoman Sultan made Constantinople his own capital and immediately took the title Kayser-i-Rum, Caesar of the Romans.

And so, the old-time Turkish empire was neither exclusively Turkish nor exclusively Moslem. It was an empire of many creeds and peoples, whose rulers actually chose to emphasise a continuity with ancient Rome, even after 1453! The name of Constantinople was retained in Turkish style as Konsnantiniyye, with the name İstanbul not becoming official until the twentieth century.

I mention a lot of Turkish names in this blog, quite a few with what may look like funny squiggles. Actually, pronouncing words written in modern Turkish letters – introduced in the twentieth century to replace a form of writing that was more like Arabic and unsuited to the sounds of the Turkish language – is easy even if you don’t know any Turkish.

The dot which appears even on the capital I in words like İstanbul means that it is pronounced ‘ee’ as in the English word ‘feet’. There is also an I that has no dot even on the lower-case letter, as in Turkish words like kızıl (‘red’) and Kaymaklı (the site of an underground city). This dotless letter ı is pronounced like the letter e in the English word ‘open’, so that it is really a sort of ‘uh’.

The Turkish letter g is hard except when written ğ as in Erdoğan, when it is softened past our usual soft g (represented in Turkish by c) to the point where it is more or less silent or pronounced like a w. A similarly extreme softening of the letter g is represented by gh in Gaelic, and for that matter in quite a few English words such as the name Roughan, so this isn’t an unfamiliar thing at all. Thus, an entry on Turkish spelling in Wikipedia suggests that English-speakers won’t go far wrong if they think of Erdoğan as Erdoghan!

Because Turkish c is pronounced like j or a soft g in English, the dynasty we term Seljuk is actually written as Selcuk in Turkish.

Where does that leave the Turkish letter j? The answer is that it is pronounced like ‘zh’ or the letter s in ‘measure’. And the Turkish letter r is also pronounced a bit differently from the way r’s are pronounced in English, more like an English d or a t. A similar kind of r in Māori led early British settlers to borrow the Māori expression piri-piri, meaning a sticky or barbed seed, into New Zealand English as biddy-biddy.

When c and s are modified into ç and ş in Turkish, that means they are to be pronounced like English ‘ch’ and ‘sh’ respectively. And when two dots appear above an o or a u, that has the same significance as in German. Once it acquires two dots on top, the Turkish letter o changes from a normal o sound to something like the e in ‘er . . . um’, while the u that has acquired two dots changes from ‘oo’ as in ‘foot’ to something more French-sounding, more like ‘ew’ or ‘yew’.

Apart from that, everything is the same as it would sound in English.

Cappadocia is spelt Kapadokya in Turkish and that gives you its official pronunciation. Westerners always use the ‘C’ spelling which is closer to the way it was spelt in Roman and Greek times. I will stick to that convention. As the Turkish spelling indicates, the first C is hard. The second c is officially hard as well but is often pronounced like a ch, or even locally like a ‘p’.

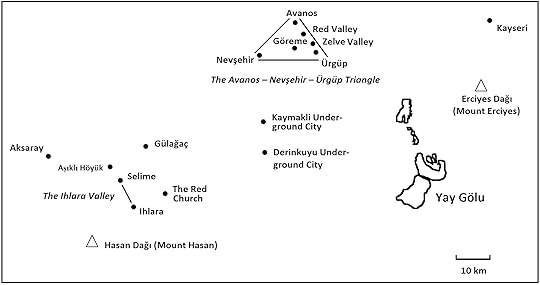

Cappadocia (or Kapadokya) is one of the most bizarre places on earth. The landscape is mostly made up of a thick layer of pumice-like volcanic ash built up over millions of years. Two prominent volcanoes, Erciyes Dağı and Hasan Dağı, stand guard over the region today. ‘X Dağı’ means the same thing as ‘Mount X’ in English. Hasan Dağı, Mount Hasan, also appears on maps as Hasandağ, although Erciyes Dağı doesn’t seem to get run together in the same way.

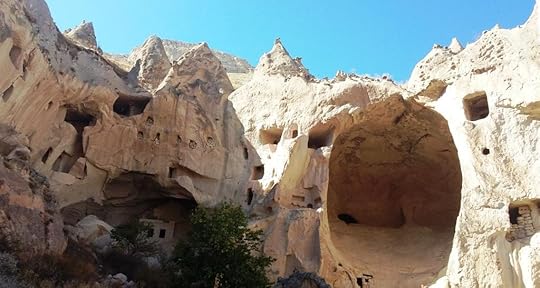

The ash has hardened into a material resembling pumice or porous concrete. By the same token, it erodes easily. Local rivers have sculpted it into deep valleys. It has also eroded into cones known as fairy chimneys in English.

These are the most distinctive features of the Cappadocian landscape. Every fairy chimney forms under a layer of harder material or even an individual boulder of more solid rock, which can sometimes still be seen perched on top.

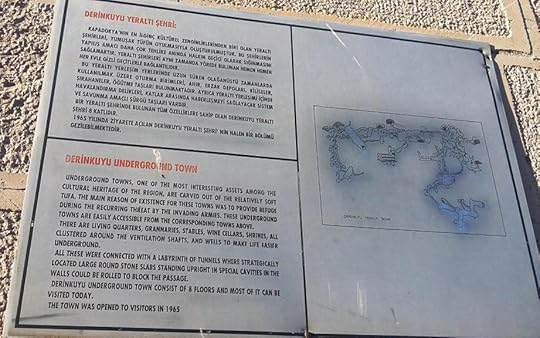

For perhaps ten thousand or so years, people have hollowed out the solidified ash to create dwellings inside the fairy chimneys and cliff-faces, in the ground, and above ground in houses cut from blocks of ash. Some of the most ancient evidence of habitation has been found at a Neolithic (late stone age) site called Aşıklı Höyük.

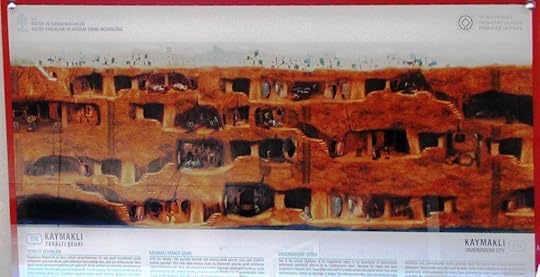

Those who felt insecure living above ground created entire, multi-level underground cities, as well as apartments carved into cliff faces, with smaller apertures for dovecotes.

Doves symbolise various spiritual and peaceful values in both Christianity and Islam. On a less exalted plane, dove manure was also used as a fertiliser for the soils of his rather barren landscape.

The scenic and ancient qualities of the Cappadocian landscape have also made it a hotspot for balloon flights.

The Minorities of Anatolia

As a result of these continuities, even as late as the First World War, about a fifth of the population of Anatolia was made up of Christian ethnic minorities: mainly Greeks and Armenians.

These minorities were concentrated in a number of distinct areas. Greeks lived along the coast and in Istanbul; Armenians in the east; and a further population of Greeks in Cappadocia.

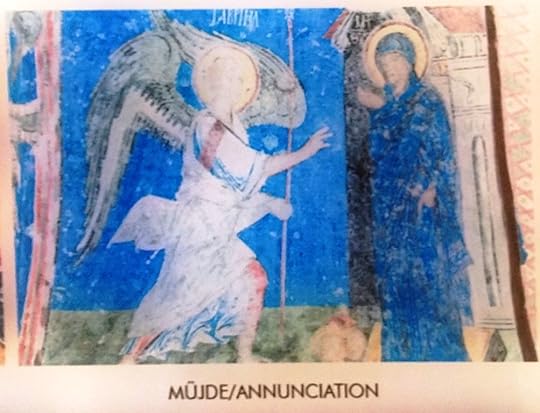

Cappadocia was especially important as a place of refuge for early Christians and as a place where early Christianity gelled.

In fact, many early saints lived in Cappadocia or came from the district. Even the Christian doctrine of the Holy Trinity was largely formulated by a group of thinkers known as the Cappadocian Fathers (the group was founded by a woman, but that’s par for the course).

In those days Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker also lived nearby, in the coastal region of Lycia. You might have heard of him as Santa Claus, which is what Saint Nicholas sounds like if said quickly. The connection comes about because the early, persecuted Christians continually gave each other gifts, in order to bind their community together.

Until the 1920s, Cappadocia remained a centre of Greek population and Greek-Orthodox religious culture.

However, after all those millennia, Greek/Christian Cappadocia succumbed to a 20th-century calamity.

At the beginning of the 1800s, in the days of Napoleon, the Ottoman Empire still ruled a vast area of Europe called Rumelia (the Rome parallel, again). Rumelia was as large as Anatolia, and Istanbul lay in the middle of the two, like the body of a butterfly between two wings.

But in a series of episodes that began in the 1820s and ended just before World War One, Ottoman Turkey lost almost all of Rumelia to various rebel peoples such as the Greeks and the Serbs.

By the second decade of the twentieth century, Istanbul was close to becoming a border town. These losses led to the rise of a movement called the Young Turks, which took over the Empire just prior to World War One.

The Young Turks saw the Empire as decadent and weak and in need of modernisation. Some of the ideas that they had for reforming it were sound. For instance, the Young Turks recognised that an incredible 90% illiteracy rate had to be brought down if the Empire was to prosper in the 20th century.

On top of that, the Young Turks observed that their country had almost no modern industries.

It was no wonder that such a ramshackle empire had been kicked out of a modern, industrialising Europe.

But other ideas the Young Turks held were more sinister, including the idea that the Empire had to be made more explicitly Turkish in national terms. What did this mean for minorities like the Greeks and the Armenians?

Although the Albanians were Moslems, all the other Balkan rebels were Christians. Christians started to be seen as disloyal, and so for that matter did anyone who wasn’t ethnically Turkish.

The Young Turks were modernisers who were hostile to aspects of Islamic culture that they saw as anti-modern. Thus, in addition to adopting a Latin alphabet and abolishing the Caliphate whereby the Sultan had claimed to lead all Moslems in addition to being Kayser-i-Rum, they suppressed burkas and veils.

Yet at the same time as they wished to see the Middle East catch up with the West in technical and scientific terms, they were militantly anti-Western in other respects.

Specifically, they saw the relation between the Middle East and the West in warlike, zero-sum terms. The only way the Middle East could catch up was, supposedly, by fighting the Christian colonial powers and physically kicking them out.

A resurgent and purified Turkey (itself a colonial power) was to lead a struggle directed mainly against the French, the British, and also the Russians, who had driven Turkey out of the Crimea and the Caucasus.

Parallels have often been made between the Young Turks and the rulers of Japan between the 1860s and the 1940s. Both had sought to modernise their country for purposes that were in other respects still quite warlike and old-fashioned.

There was one key difference. Unlike Japan, which was ethnically homogeneous and insular, Turkey was heir to a succession of cosmopolitan empires. Even Anatolia, the modern Turkish heartland, was full of minorities who didn’t fit into an extreme nationalist scheme. To repeat, what was to become of them?

Things really got bad for these minorities after the outbreak of World War I.

The Armenians, suspected of being sympathetic to Russia, were nearly exterminated, and a large proportion of the Empire’s Greeks and Assyrians were killed as well.

Many journalists, academics and foreign governments have thus taken the view that events in World War One-era Turkey closely foreshadowed the Nazi Holocaust. Officially, any such parallel is still denied by the Turkish government, but the denial is wearing thin.

During World War One, Turkey had been on the side of Germany and Austria. Turkey’s rulers hoped that if France, Britain and Russia were defeated, a new and more vigorous Turkish empire might regain territories lost to the Russians and Balkan rebels, and possibly even extend itself into central Asia.

Unfortunately for the Young Turks, they found themselves on the losing side in 1918. In another parallel with later events, some Turkish leaders were then prosecuted and in some cases executed for ‘crimes against humanity’: a phrase that first entered the lexicon at that time and in that context.

The treaty that ended Turkey’s war with the Western Allies was also, itself, a punishment. In addition to losing its Arab possessions, the Ottoman Empire was forced to cede some Greek-speaking parts of Anatolia to Greece, which had joined the war on the side of the allies in 1917.

Naively, the Greek Army crossed the Aegean to garrison its new empire.

At this point the Turks went to war again. Turkey might have just been defeated, disarmed, shorn of its possessions and internationally shamed in a similar fashion to the way Germany and Japan would be a generation later. But it still packed enough of a punch to defeat little Greece.

Greece had assumed that its former World War One allies were going to pitch in and help it set up camp in Anatolia.

But the Americans had gone home. Russia had morphed into a Soviet Union that viewed Turkey as a possible ally. And the British Empire and the French, traumatised by the Gallipoli campaign, weren’t too keen on going another round in that part of the world either.

Greece’s over-reaching was the final nail in the coffin of Greek culture in Anatolia. After Turkey succeeded in driving out the Greek army, the two countries agreed to a population exchange that foreshadowed the later partition of India. One and a half million Greeks were expelled westward from Turkey and at the same time, half a million Turks were expelled eastward from Greece.

After the expulsion of the Greeks, ethnic Turks moved into Cappadocia and the towns and villages were given new, Turkish names. The region continued to be known by its old name, however.

‘The Land of Beautiful Horses’: Birth of the Modern Tourism Hotspot

Half a century after the Greeks were thrown out of Cappadocia, the Turkish government began to realise that the region had tourism potential. It was a landscape full of natural wonders and abundant physical remains of Greek Christian culture, such as old churches and religious wall-paintings.

In the 1970s, the main champion of tourism in Cappadocia was a photographer named Ozan Sağdiç, who had been taking pictures of the region’s marvels for years. Here are some more from my recent trip, by the way:

While Sağdiç was promoting Cappadocia as a tourism destination, Turkey was ruled by a right-wing military junta full of ideological heirs to the old aggressive nationalism. In 1981, the junta demanded that broadcasters and promoters stop using the ancient name of Cappadocia and its Turkish equivalent Kapadokya on the grounds that they both sounded Greek. The junta wanted to replace Cappadocia/Kapadokiya with a more unambiguously Turkish name, which would have sounded more patriotic, but also unfamiliar to anyone who wasn’t Turkish and probably to most Turks as well.

This was obviously a potential marketing disaster. Quick as a flash, Sağdiç told one of the members of the junta that the name Cappadocia “could be Persian.”

Although it sounded like a Greek name, nobody knew for a fact what Cappadocia meant or what language it came from. Sağdiç suggested that it came from the Persian word Katpatukya, which meant the land of beautiful horses. The Hittites, who had inhabited the area before it was settled by Greeks, had been experts at breeding horses. That was a fact, even if the rest was speculation.

Heck, the theory was as good as any . . . and it mollified the generals and admirals enough for Cappadocia to keep its old name, whether it sounded Greek or not.

Postscript: The story about Sağdiç is told in Hürriyet Daily News, Does Cappadocia mean ‘the land of beautiful horses’?, 1 September 2015. Ironically enough, the name favoured by the junta, Göreme, which is already the name of a part of Cappadocia, is known to be a Turkish adaptation of an older Greek place name.

The post On a Kiwi Visa in Cappadocia appeared first on A Maverick Traveller.

December 13, 2017

Outfoxed in the Valley of Marvels

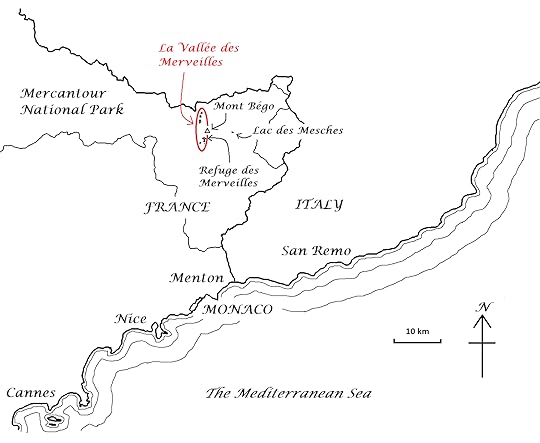

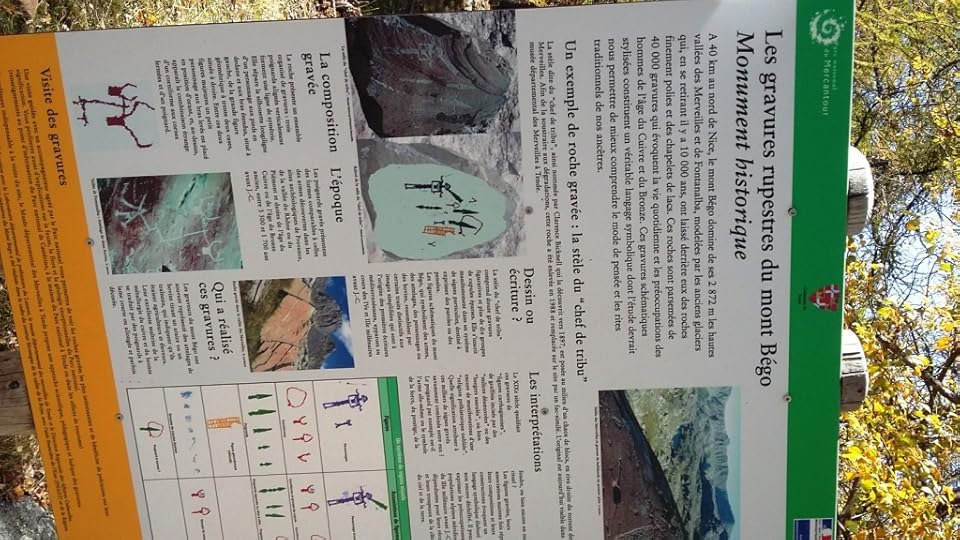

In October, my friend Jean-Claude and I went to visit an area that the French call la Vallée des Merveilles, the Valley of Marvels.

Google Maps calls it the Valley of Wonders. Whatever you call it, the valley is in the far southeast of France, inland from the Riviera and just west of Mont Bégo, an ancient name meaning the abode of the gods.

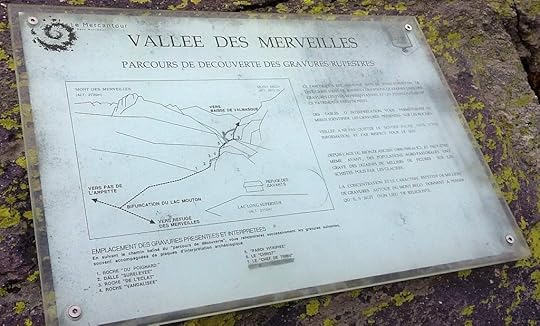

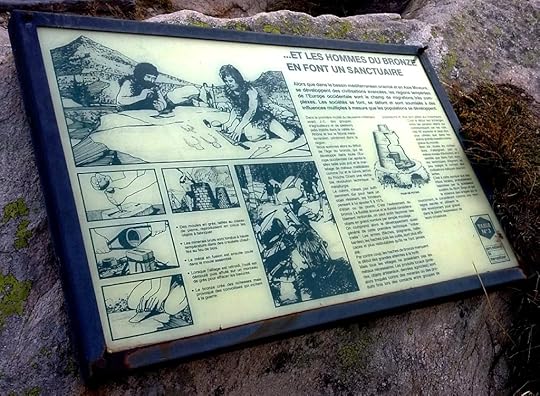

The Valley of Marvels is high up in the mountains. During the last ice age, it was covered in ice. The rocks were scraped flat, making them into natural targets for an early form of graffiti.

Some four thousand years ago, people who were probably related to the Celts carved tens of thousands of images, called petroglyphs, onto the rock faces. The images resemble sketch drawings and were made by hitting the rock face to carve shallow lines, between half a millimetre and five millimetres deep.

The name Valley of Marvels does not refer to these rock drawings but to the region’s mountain thunderstorms, called merveilles or wonders by French people in later, Christian times. The word reflects an ancient view of thunderstorms as supernatural.

It’s thought that the rock carvers lived on the modern-day Riviera, and made pilgrimages up to the valley to carve images which were mainly in honour of a thunder god. Others seem to have been carved in honour of a bull-god, a familiar Mediterranean motif. Many of the carvings depict figures with horns on their heads.

In the Middle Ages these were mistaken for images of the Devil, and the area was shunned. In fact, the valley is pretty spooky at the best of times. So, you can only imagine what the Mediaeval mind would have made of it.

The valley is accessible only on foot, and lies fairly deep inside the Mercantour National Park. It is regulated by an archaeological agency, and tents have to be taken down by 7 am. We drove to a carpark at a tiny hydro lake called the Lac des Mesches and hiked westward toward the valley. We made camp after only three hours, which was a mistake because it meant we had to hike for twelve hours the next day.

To make matters worse, all our best food was stolen in the night by a French fox. We left the food outside the inner part of the tent because we thought the place was so barren that nothing would happen to it. In the morning it was gone. We know a fox was responsible because it left fox poo in exchange for our salami and cheese. All we were left with was gluten-free rice crackers!

During our twelve-hour hike we climbed two mountains that were each 2,800 metres high. The valley itself is at an altitude of roughly 2,400 metres.

On a nearby lake stands the Refuge des Merveilles, a massive stone hostel with solar power and hot water. We also saw a warden’s hut, and a curious structure left over from the World War II era.

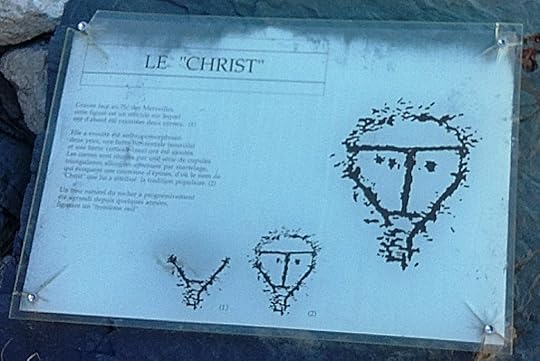

We had our photo taken next to a particularly famous rock carving called “Le Christ,” because it superficially resembles an image of Jesus. It probably pre-dates Jesus, however, by about as far as Jesus predates us. Which is something to think about.

After the Middle Ages,people started visiting the valley again and adding more graffiti. A rock drawing dated 1893 has a certain raw energy of its own. All the same, because of the threat that such additions posed to the older petroglyphs, the valley was eventually placed under strict archaeological regulation.

We saw two houses with French flags flying. Jean-Claude said that this was most unusual and reflected the rise of Marine Le Pen and the National Front.

La Vallée des Merveilles is only one of the attractions of the vast Mercantour National Park. Overall, the Mercantour National Park is an area of great biodiversity. It contains many rare species that were common in the Ice Ages but have now declined elsewhere in France.

Unlike national parks in New Zealand, Mercantour National Park also contains sizeable human populations, in picturesque hillside villages known as ‘perched villages’. Mercantour is popular with the French but seems hardly to be visited at all by English-speaking tourists. It is, in that sense, off the beaten track of Anglophone tourism despite its proximity to the Riviera!

The post Outfoxed in the Valley of Marvels appeared first on A Maverick Traveller.

November 30, 2017

From Country Music to Energy from Space: A Maverick USA Way

From Country Music to Energy from Space: A Maverick USA Way, Mary Jane Walker’s fifth book of world travels

Mary Jane Walker is pleased to announce the launch of the fifth in her series of unconventional accounts of world travel, A Maverick USA Way.

A Maverick USA Way is the United States as seen and experienced from the Antipodean point of view by Mary Jane, a regular visitor to the USA since 1996.

On her latest trip, Mary Jane took advantage of direct flights between Auckland and Houston to arrive in the American heartland, a change from Los Angeles.

She visited the Space Museum and learned how the Apollo program might have led to solar power from space, but didn’t.

Mary Jane rode the Amtrak tracks around the lower 48 states and passed through the Dakotas twice, the second time to catch up with the anti-Keystone pipeline protests at Standing Rock.

A protestor asked to use her phone at the Bismarck public library and she gave him a lift, so she got straight into the heart of the camp.

She hired 14 cars and listened to a musician on the train, who said that Johnny Cash was more authentic than Elvis because he wrote all his owns stuff.

Hiking in Glacier, Yellowstone, Yosemite and Rocky Mountain National Parks proved quite different to New Zealand. People needed bear-proof containers, electric fences and bear spray. Another hiker told her how his father had hoisted him onto his shoulders to keep from being eaten by a hungry mountain lion.

Detroit was a stately Art Deco city reverting to parkland, like ancient Rome after its fall.

Mary Jane was in the USA for the elections and saw a lot of discontent; she was not surprised Trump won.

On the way home she stopped off in Hawaiʻi and took in the view of the volcanoes, while noticing how many homeless people seemed to gravitate to the islands.

All of Mary Jane’s books are lavishly illustrated. The following Book2Look widget links provide previews of the printed monochrome text, and of the books’ photography in its original colour form:

A Maverick Traveller (preview) Extract with colour images

A Maverick New Zealand Way (preview) Extract with colour images

A Maverick Cuban Way (preview) Extract with colour images

A Maverick Pilgrim Way (preview) Extract with colour images

A Maverick USA Way (preview) Extract with colour images

A Maverick USA Way will be promoted for free on Friday 1 December and again on Friday 8 December 2017 (US dates).

For any further information, please contact Mary Jane or her editor Chris Harris by email to admin [at] a-maverick.com.

Facebook: amavericktraveller

Instagram: @a_maverick_traveller

Twitter: @Mavericktravel0

Pinterest: A Maverick Traveller

The post From Country Music to Energy from Space: A Maverick USA Way appeared first on A Maverick Traveller.

November 19, 2017

From Venice to Mt Etna: My Long Drive through Italy

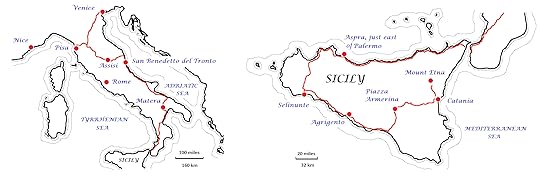

Will you be doing anything like this for Thanksgiving weekend? In October, I drove for more than 1,500 km down the Italian peninsula and around Sicily.

After my stay in Venice, which you can read about here, I drove to Mount Etna in Sicily. I travelled more than 1500 km, and it took me ten days to get there.

I had a four-wheel drive which only cost me 16 Euros a day with full insurance. I thought this was a bargain, but in hindsight I definitely wouldn’t recommend driving long distances in Italy!

I was forced to drive at 130 or 140 km/h (80+ mph) on the Autostrada and its many tunnels. On local roads I ended up going through villages where the roads were so narrow that it was hard not to get the car scratched. In fact, I had to cough up 250 Euros for scratches when I returned it.

From Venice, I went south-west into Tuscany and Umbria.

I made a bee-line for Pisa and its famous leaning tower.

The Via Francigena, a famous pilgrim trail, passes through these parts and I caught up with it near Pisa, too. (There are a couple of photos of the Via Francigena signs at the end of my earlier Venice blog.)

After Pisa, I got lost and ended up at the seaside, on a coast bordered with olive groves. I didn’t mind that at all!

Then I headed south-east, along a route that took me past the tomb of the legendary Saint Francis of Assisi, in the town after which he is named. Many people think of St Francis of Assisi as the first environmentalist, as well as a friend to animals.

I got to the Adriatic coast and rested up for a while at a town called San Benedetto del Tronto, roughly halfway down the Italian peninsula.

In San Benedetto, I was booked into a hostel by the port, which I didn’t like. I used my Italian SIM card to book another one, and went to a restaurant where I had sardines fried in batter—amazing!

The Adriatic is the shallow sea between Italy and the former Yugoslavia. It is named for the Roman Emperor Hadrian, Adriano in modern Italian.

I was keen to stick to the coast for this leg of the journey so that I could enjoy the sea views. I drove through lots of small towns on the coast, towns that often had incredibly narrow streets once you got off the main highway and no parking anywhere near the middle.

Once or twice I went the wrong way up one-way streets because the street layouts were so higgledy-piggledy it was hard to tell which street a given sign referred to!

One thing about Italy is that the food was terrific everywhere. Ensalada del mar was my favourite in coastal towns: seafood salad with cold aubergines and beans, you name it!

I carried on down the coast all the way to Bari in the south, near the ‘heel’ of the Italian boot. At that point I headed inland, toward the extraordinary town of Matera, which is partly hewn out of the rock in a ravine, in a similar fashion to the cave-towns of Cappadocia in Turkey.

The old part of Matera is a UNESCO World Heritage site: one of many in Italy, of course.

I followed my GPS and it took me literally all the way to the gangplank of the ferry to Sicily!

I crossed over and drove to Palermo, staying for four nights at a village called Aspra on the coast, east of the city. I didn’t miss much by staying so far out, as Aspra was always busy. There was always something happening, with night markets and some people filming a movie with actors on the beach. And more ensalada del mar.

I stayed for three days at a guest-house with a couple, as their only guest. The woman had had chemo and lost her hair. So, I gave her a necklace and ear-rings that I picked up in Murano, the famous glass-making district of Venice. She was forever grateful!

Sicily used to be hugely strategic, and Palermo the finest city in the Mediterranean around 1100 CE, or so it was claimed.

The island was at the crossroads of the early Mediaeval world, ruled successively by the Arabs, the Normans, the Spanish and even the Germans, both in the form of the ancient Goths and Vandals and also the later Holy Roman Empire and house of Hohenstaufen. Sicily was a far-flung possession of most of its rulers, yet a valuable one, since it lay in the centre of the Mediterranean.

But over time Sicily became something of a backwater, along with the rest of southern Italy, as Europe turned its attention away from the Mediterranean world and toward the Atlantic.

For about fifty years after World War II, Sicily was dominated by the Mafia, which had been used by the Allies to help fight fascism and thus given a leg-up into respectable society. But after numerous prosecutions and the 1992 murders of two judges, Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, the Sicilian Mafia became discredited and lost its former influence.

The Sicilians speak a dialect, or really a separate language, influenced by Greek and Arabic as well as the many other peoples who have passed through.

As in other parts of Italy, the local language has almost no official status in Sicily. However, there are about five million Sicilians in Sicily, plus a large overseas community (a million Sicilians emigrated between 1871 and 1914), so there is little chance of Sicilian dying out.

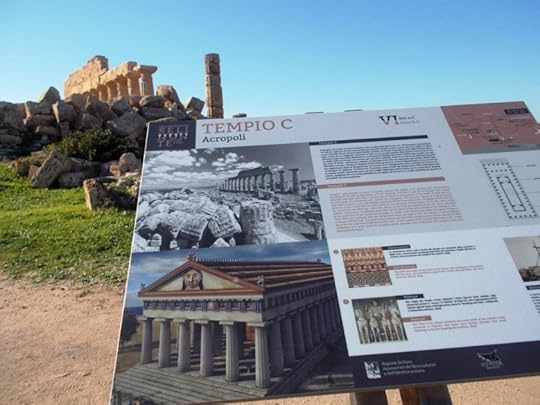

The Greek influence on Sicily was particularly strong in ancient times, more so than that of the Romans. The island is studded with Greek temples and other relics. Many famous Greeks of ancient times, such as the engineer Archimedes and the playwright Aeschylus, actually lived in Sicily.

I went to see some of the ruins at Agrigento, the home town of Empedocles, an early Greek scientist who was perhaps the first to argue that light travelled at a constant speed. And I also saw some more ruins at Selinunte, another ancient Greek city.

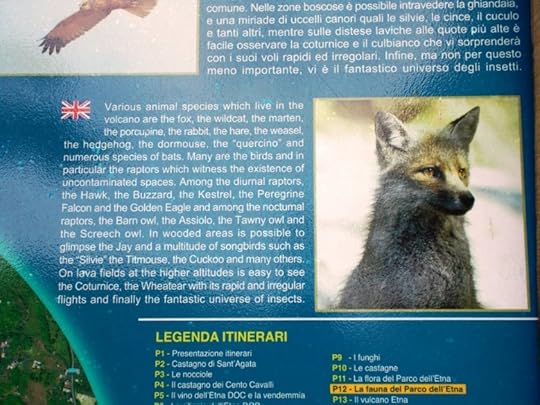

I spent another two nights at a place in an olive grove outside the central Sicilian town of Piazza Armerina. The building was run-down outside, like a lot of buildings in Italy, but a palace inside! I carried on to Catania and went and saw Mount Etna, the famous volcano nearby which has been active for thousands of years. Empedocles is supposed to have perished by leaping into the crater in the belief that volcanic fumes would support his weight. Of course, there is no reason to suppose that this is true.

I mentioned how driving long distances in Italy was a bad idea. It seems none of the locals risk it because, when I was in Sicily, I was pulled over by two full carloads of local cops who saw my Venice licence plates and thought that there had to be something fishy going on! They went through all my papers and asked lots of questions. That was quite heavy.

From Catania, I caught a plane to Rome, where I stayed near the airport at Fiumicino. I caught transport into the city at 4:30 am and wandered around Saint Peter’s Basilica. I’d forgotten how beautiful the city was.

After Rome, I flew to Nice in the south of France to catch up with an old friend who lived in the foothills of the Alps — a good topic for another blog!

To round off, here are some of the photos that I took, or had taken of me, along the way!

The post From Venice to Mt Etna: My Long Drive through Italy appeared first on A Maverick Traveller.

October 11, 2017

Views of Venice: A Maverick Traveller visits the ‘Most Serene Republic’

THIS has been an easy blog to write, and an even easier one to illustrate. Anyone with a modern camera can take pictures that look like the work of the painter known as Canaletto.

Strategically located on a cluster of harbour islands at the head of the Adriatic Sea, and immensely wealthy at one time from trade and skilled crafts such as the glass-workers of Murano, Venice was always on the itinerary of the old-time traveller and artist.

Venice was founded by refugees from the fall of the Roman Empire, who came to live on the islands to be safe from marauding barbarians. The islanders soon found that their new home was a good base for trade.

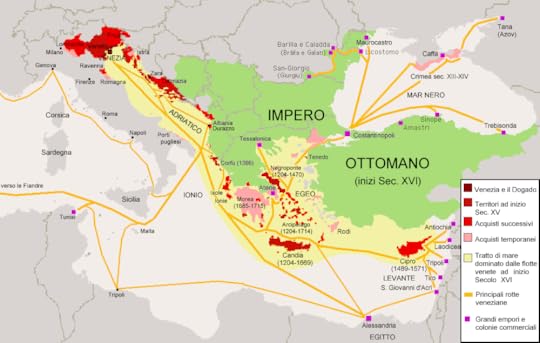

By the time of the Renaissance, the Venetians had established a surprisingly far-flung empire of their own, ruling over territories as distant as Cyprus. The long-distance traveller Marco Polo was a Venetian of this era, too.

The historical ups and downs of Venice

Precariously located along the edge of an expanding Ottoman Empire, the Venetian Empire—well, not officially an empire; it was always called La Serenissima, the Most Serene Republic—gradually shrank, thereafter, until the Venetians were bottled up in their home waters once more.

The Most Serene Republic was ruled by an official called the Doge, the local dialect equivalent of Duke, Dux or Duce.

The Venetians established once of the first modern factories, the Arsenale or Arsenal, which produced one war-galley or trading-ship every day by means of assembly-line techniques. The Arsenale still stands: it looks like it was built in 1900, not in the 1300s (when the greater part of it was constructed).

The Venetians were able to hang onto their maritime empire for as long as the Turks remained landlubbers. However, once the Turks got a navy of their own, it was all over for the more distant Venetian colonies.

The Most Serene Republic was finally abolished by Napoleon, who was good at abolishing things. He also abolished the Holy Roman Empire, another old empire ruled (rather loosely) from Vienna; not to mention miles, feet and inches over the greater part of Europe.

Napoleon made himself King of Italy, meaning a chunk of the north that included Venice, and his brother Joseph, King of Naples and Sicily. After the Bonapartes were booted out—the geography of Italy inspiring many a cartoonist on the subject—Venice was taken over by a an HRE which had bounced back under the new title of the Austrian Empire.

For a time, Austria would rule much of Northern Italy. However, at the beginning of the 1860s, Venice was liberated from the Austrians by the unifiers of Italy, who proclaimed that the city was free once more—and would therefore now be ruled from Rome, not Vienna.

Modern ups and downs

These days, Venice is perennially sinking into the mud and has a general air of having seen better days about two hundred and fifty years ago, after which it lost its independence and was bypassed by modern land transport and the Industrial Revolution.

Of course, that only makes Venice more touristy. Where else can you walk the streets of an eighteenth-century city which is still just as it was?

In my book A Maverick Pilgrim Way, from which the map of Italy at the start of this post is adapted, I describe how I’ve been to Venice before.

Before returning once again in October 2017, I’d read about a rise of anti-tourism sentiment among its dwindling population of 55 thousand, due to the general strain caused by 22 million visitors a year, excessively high prices for everything as a result, and, even, air pollution from cruise ships.

The last of these is a surprisingly serious problem. Several of my photos in this blog show hazy air. Ships’ engines do not have emission controls or limits on sulphur in the fuel and are still allowed to pump out black smoke all day long. The theory is that it all blows away at sea and anyway, there is no government to regulate it. Well, that’s as may be, except when they get to Venice, where it is bad for health and also eats away at old buildings and statues.

My trip this time

This time, to escape the overcrowding in summer, I decided to come in October. I stayed in the Rialto district at an Airbnb for 40 Euros or the equivalent of US $50 a night.

(It’s a sign of Venice’s popularity with the tourists that every other city also seems to have a cinema or a swimming pool called the Rialto, or the Lido, another district of Venice.)

I got a seven-day pass for the water taxis, which are called vaporetti, or vaporetto in the singular. This cost me 65 Euros or about US $ 77. Vaporetto basically means ‘little steamer’; that is, as opposed to the poles of the traditional gondoliers.

A 40 Euro museum pass got me into the Doge’s palace, into a number of Venice’s splendid museums and galleries, and most of the historic churches.

The grand view of Venice

I had to get a separate pass for St Mark’s Basilica and the bell tower in the Piazza San Marco, bypassing the queues for a physical ticket. Gong up the bell tower and looking down on Venice is a must! I’ve shown some of the photos I got from here, already, and here is a video as well.

Some of the other things I did

I went for a ride on a gondola, costing 80 Euros for fifteen minutes, which I split with an American woman. The gondolier told me that even he couldn’t afford to live in Venice these days.

And I went to famous Venice Biennale art show, which had a New Zealand exhibition by Lisa Reihana, all about the colonisation of the Pacific, set up inside the factory-halls of the Arsenale. The 2017 Biennale is the 57th; the Biennale has been going since 1895.

The Russian exhibition, Theatrum Orbis, was taken up with several thought-provoking themes that included online immortality and the surveillance society, while the American exhibition, by the artist Mark Bradford, was also impressive if a little gloomy.

I also went to see a play called Fuorissimo, meaning ‘crazy’, in which the characters all wore symbolic masks. This is an old tradition called Commedia dell’Arte, a stylised form of satirical entertainment based on stock characters identified by their masks, as in some Asian countries. In the local context, it probably descends from Greek and Roman drama or Mediaeval morality plays.

The meaning of Commedia seems to lean more toward more worthy themes than the word ‘comedy’ usually does in English. Maybe this reflects the influence of Dante’s Divine Comedy, at the heart of which is the Inferno. So, we aren’t talking about Mrs Brown’s Boys, in other words.

That reminds me, also: the Venetian dialect, which is distinctive, gives us the word ‘zany’ as well as Doge. Zany comes from the local pronunciation of the name of one of the stock Commedia dell’Arte characters, a fool called Gianni, or John.

Here are some photos of artwork that wasn’t part of the Biennale, just interesting modern street art, to show that not everything in Venice is ancient.

And though it might be because of all the air pollution, I have to say that I’ve rarely seen sunsets like the ones I shot in Venice!

Postscript:

On Sunday 22 October, the regions of Veneto (where Venice lies) and Lombardy voted for greater autonomy from the Italian state in regional referendums. Perhaps La Serenissima is being restored to some degree!

But before that, after I left Venice, I headed on south and hooked up with the Via Francigena pilgrim trail near Pisa. You can read about that in my new book A Maverick Pilgrim Way, which will be on a free special this Friday and Saturday, the 3rd and 4th of November (US time) on Amazon Kindle .

The post Views of Venice: A Maverick Traveller visits the ‘Most Serene Republic’ appeared first on A Maverick Traveller.

A Solo Woman Traveller in Qatar

Map data ©2017 Google, ORION-ME

AT THE beginning of October 2017, I stopped off for two nights in Doha, the capital city of the the small Persian Gulf state of Qatar (and its only sizeable city). Travellers from New Zealand often choose to break the long journey to and from Europe in Bahrain, Qatar, or in the nearby United Arab Emirates,

Long a refuelling-stop for airlines based in other parts of the world, the oil-rich region now has several well-known airlines of its own: Qatar Airways, Emirates, and Etihad.

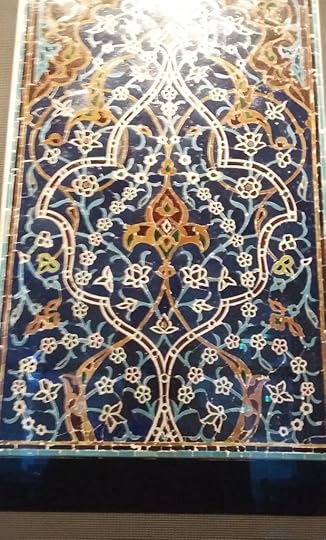

While I was taking a break in Doha, I also took quite a few photos. A gallery appears at the end of each of the next few sections. Click on each image and it will get bigger. I’ve also included a video of constantly changing Islamic designs, in a fascinating light-show which I saw inside Doha’s Museum of Islamic Art.

Why I Wanted to Visit Qatar

I was especially keen to visit Qatar because of the recent boycott by Saudi Arabia, which closed Qatar’s only land frontier in June 2017. Four Arab states, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, have boycotted Qatar since then. They have accused Qatar of destabilising the region via the Arabic-language broadcasts of Qatar’s state-owned broadcaster, Al Jazeera, which supported many of the protesters in the Arab Spring movement of 2011.

Much as in Thailand, the media in Qatar are not allowed to criticise the ruler himself, the Emir. But they are free to get stuck into anyone else. Neighbouring rulers, who have been regularly criticised by Al Jazeera under that they see as a double standard, want to see Al Jazeera Arabic closed down. The English-language version of Al-Jazeera, mostly viewed by Westerners, does not seem to be under attack to the same degree.

I wanted to see how Qatar was coping under the boycott.

About Qatar

Qatar has a population of 2.6 million, most of whom are foreign guest workers and their families. Only a little over 300,000 people in the country are Qatari citizens. The capital, Doha, is halfway along the east coast of Qatar, a peninsula with only one land border, the border with Saudi Arabia.

Qatar has a long history. It was known to the ancient Greeks and Romans, who spelt it with a K and a C, respectively. It was ruled by various Arab rulers for centuries, and then from 1871 until 1916 by the Ottoman Turks. After the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Qatar and the Emirates became part of the British Empire. They were subject to form of semi-colonial rule in which the British stationed troops locally and agreed to to defend them from attack in return for their not hosting troops from any other country.

In 1968, the British decided to bring home all troops stationed ‘east of Suez’ in order to save money. The policy was upheld until the first Gulf War in 1991. No more Tommies east of Suez meant that the Persian Gulf protectorate was finished. And so, Qatar and the Emirates became fully independent in 1971.

With the third-largest reserves of oil and gas in the world, the fortunes of the newly free Qatar were assured. On the other hand, like Kuwait, it was still coveted by its neighbours just as it had been in the past. A precariously independent Qatar must do the splits, diplomatically speaking, between nearby Saudi Arabia and Iran just across the water. With the British gone it hosts new military bases, both of the United States and of its former overlord Turkey (the splits, once again).

Qatar is also the first Arab nation to be hosting a FIFA World Cup football tournament, in 2022. Just lately, a a link has been made between the blockade and the World Cup. It seems that if Al Jazeera Arabic won’t be closed by the Emir, then Qatar giving up the World Cup might be the new price for ending the blockade.

What I Found

I ended up staying in the area of Doha known the consulate district, in the West Bay Lagoon area. This was some 30 minutes from the airport. I stayed in Airbnb accommodation with a huge and amazing room and a large double bed.

I went to the amazing Museum of Islamic Art: a form of art noted for its emphasis on calligraphy and abstract and floral designs. The museum described the cultures of various nationalities in the Islamic world: people such as the Kurds, Mughals (responsible for the Taj Mahal), Arabs, Persians, Turks, and the Uighurs from western China.

For the concerned female traveller are taxis aplenty (though not all of them well-regulated). And security guards of a sort that I found reassuring are everywhere as well.

I went to the markets, and enjoyed beautiful Arab food in the Old Market. On the shore I saw the dhows, which still ply these waters as in the days of Sinbad.

The main tourist season is winter and early spring, when cold desert nights make the mornings cool and crisp. When I was there it was about forty degrees C. And that wasn’t the hottest time of the year!

Although Qatar is wealthy enough to weather the blockade, it is starting to tell. There has been some inflation of food prices.

The Old amid the New and the New amid the Old

Qatar is unquestionably an Islamic country, though its guest workers practice a variety of faiths and non-faiths. It lives under a form of Sharia law similar to that of Saudi Arabia, complete with the prospect of being flogged or beheaded for things that people from elsewhere would not regard as terribly serious. There is one liquor store in the whole country, serving non-Muslims, who must have a permit to prove it.

The system is thus similar to Saudi Arabia in some ways, but less extreme in practice.

I did not run into any cultural obstacles to a single Western woman travelling alone. In contrast to Saudi Arabia, women have long been allowed to drive in Qatar. And in contrast to both Saudi Arabia and Iran, women are not forced to wear Islamic head-coverings in public.