Daniel Miessler's Blog, page 94

October 19, 2018

The Cybersecurity Hiring Gap is Due to The Lack of Entry-level Positions

I recommend reading this in its native typography at The Cybersecurity Hiring Gap is Due to The Lack of Entry-level Positions

—

If you haven’t heard yet—which is unlikely—there’s a problem with hiring in cybersecurity.

The issue is we’re not sure of the nature of that problem.

A number of studies are talking about there being 3.5 million unfilled cybersecurity positions by 2021. But many are in that same market looking for work and are unable to find any.

So who’s right? I think the unfortunate answer is that they both are.

Lots of people are trying to hire good Infosec people, and lots of people are looking to get into Infosec. The problem is that there’s a gap between these two groups caused by:

Companies need people who are somewhat effective on day one, even if they have a lot to learn, so they can’t be starting from nothing.

Companies are bad at hiring, so they often miss people with no hard credentials but that have the raw talent and a bit of experience that would make them a great hire.

People without hard credentials aren’t good at marketing themselves either, which makes it even harder for the interviewer to find their talent through an ancient hiring process.

Basically the system is broken.

People doing the hiring are gatekeeping using old techniques that probably didn’t even work well 30 years ago. They’re filtering for core academic principles, interesting facts within the field, and content that was in their interviews.

Interviewing is far too much like hazing—where the interviewer feels the need to pass on the pain of their previous experience as a right of passage.

These archaic practices filter out people who could likely do quite well if given a chance. And those types of people aren’t getting the advice they need to highlight their talents. Instead they go into the interview scared of the inquisition, which is likely what they run into.

Another part of the problem is that there are many people with some measure of technical skills or qualifications that can’t program and/or think dynamically to solve different kinds of problems. That’s what’s needed in Security roles—people who can adjust to lots of different situations and solve a wide spectrum of problems.

So sometimes the filters work as desired by removing people who have all the skills on paper but aren’t able to actually put them to use.

How we can do better

My advice for both sides of this equation is to focus on practical skills. Ideally, and what will surely be coming at some point, we’d be able to reverse engineer what good security people look like by taking a data science approach to their attributes.

Hmm, turns out the best security people are from Wyoming, are left-handed, and hate the color yellow.

But humans are horrible at this kind of big-data analysis. We’re stupid little bias machines, and that makes us likely to include and exclude people for all the wrong reasons. We can fight those inclinations though, using a methodology.

What we need to do is turn the hiring practice around completely, and start hiring for the things we care about instead of some arbitrary, old-world notions that probably never worked in the first place.

Don’t ask if they have a degree: ask them how they think the world works.

Don’t ask them if they’re an A student: ask them what they have built lately.

Don’t ask them if they can program: ask them to show you some code.

Don’t ask them if they’re good at problem-solving: ask them to solve a problem with you.

Filter for what they’re actually going to do be doing on the job.

Advice for hiring managers

Make a list of the attributes that your best security people have

Make a list of the attributes that your worst security people had (hopefully they’re not there anymore)

Rebuild your entire interview process based on finding those attributes

If they are going to be coding, ask to see recent code they made

If they’re going to be making tools, ask them about a recent tool they made, and why they made it that way

If they’re going to be hacking stuff, ask them how they would hack a given thing, and then let them do it in a live CTF environment

If they’re going to be doing documentation and communication, explain a complex technical and political situation to them, and have them write the documentation and emails that will be used to make all sides happy

Advice for people trying to get into the field

Stop focusing so much on how you look on paper as a candidate, and start thinking more about what you can do as a candidate

Have a lab—either at home or in the cloud

Have projects that you can talk about

Have a blog where you write up the projects you’re working on

Be active on Twitter where you are interacting with people with similar interests, where you give help to others, and where you share your projects

Have an active Github account where you’re sharing your projects, and where you’re helping others with theirs

The one offering assistance and asking for help with your own projects.

The great thing about this approach—on both sides—is that it’s quite hard to fake.

If someone has an active website, a lab, multiple projects in Github, and they’re spending good amounts of time on Twitter talking enthusiastically about their craft—that’s someone you want to hire.

They could be a high-school student or a Ph.D.—you want to hire that person. And that’s kind of the point: a bad interview process could still miss this candidate.

So what’s your work experience?

This same total-badass-in-the-making can completely screw up that question, and basically say:

Um, nothing sir. No experience. Just stuff I do on the side.

Pass.

That’s what’s wrong with the system. People asking the wrong questions, and people giving the wrong answers to the wrong questions.

In both cases, focus on the practical.

It’s not about how someone looks on paper. It’s about what they can actually do. And the best way to know that is to look at what they’ve done already.

Summary

There are two conflicting messages about the cybersecurity jobs gap.

Companies are saying they can’t find near enough people, and people trying to get into the industry are saying it’s impossible to get hired.

This disconnect is due to there not really being entry-level positions in cybersecurity. You have to be minimally useful on day one if you hope to get hired.

This is how both perspectives can be true simultaneously: it’s hard to get into the field, but once you’re in there’s basically zero unemployment.

There are basically three ways to get over the initial hump to start the career and be on your way: have a degree, have good certifications, or have a body of work out there that shows real-world capability.

As an employer, you can find more candidates by changing your perspective away from gotcha questions and gatekeeping interviews, and moving towards asking people what they’ve done and how they’d solve real-world problems, followed up by practical tests that simulate the actual work they’d be doing.

As someone looking to get into the industry, if you have a bachelors in CS, CIS, or cybersecurity you should be fine. If you don’t have that, get a Security+, build a lab, start a Github account, start a blog, get active on Twitter, and start making things. Write code to solve problems, help other people with their projects, ask questions, answer questions, and share your work with the community. Without a degree, the best way to get over the gap is to show your value through real-world projects. Get on it.

Notes

For more advice on getting into cybersecurity, check out these two guides by Lesley Carhart, and me.

—

I spend between 5 and 20 hours on this content every week, and if you're someone who can afford fancy coffee, please consider becoming a member for just $5/month…

Thank you,

Daniel

The Problem With Cybersecurity Hiring

I recommend reading this in its native typography at The Problem With Cybersecurity Hiring

—

If you haven’t heard yet—which is unlikely—there’s a problem with hiring in cybersecurity.

The issue is we’re not sure of the nature of that problem.

A number of studies are talking about there being 3.5 million unfilled cybersecurity positions by 2021. But many are in that same market looking for work and are unable to find any.

So who’s right? I think the unfortunate answer is that they both are.

Lots of people are trying to hire good Infosec people, and lots of people are looking to get into Infosec. The problem is that there’s a gap between these two groups caused by:

Companies need people who are somewhat effective on day one, even if they have a lot to learn, so they can’t be starting from nothing.

Companies are bad at hiring, so they often miss people with no hard credentials but that have the raw talent and a bit of experience that would make them a great hire.

People without hard credentials aren’t good at marketing themselves either, which makes it even harder for the interviewer to find their talent through an ancient hiring process.

Basically the system is broken.

People doing the hiring are gatekeeping using old techniques that probably didn’t even work well 30 years ago. They’re filtering for core academic principles, interesting facts within the field, and content that was in their interviews.

Interviewing is far too much like hazing—where the interviewer feels the need to pass on the pain of their previous experience as a right of passage.

These archaic practices filter out people who could likely do quite well if given a chance. And those types of people aren’t getting the advice they need to highlight their talents. Instead they go into the interview scared of the inquisition, which is likely what they run into.

Another part of the problem is that there are many people with some measure of technical skills or qualifications that can’t program and/or think dynamically to solve different kinds of problems. That’s what’s needed in Secuirty roles—people who can adjust to lots of different situations and solve a wide spectrum of problems.

So sometimes the filters work as desired by removing people who have all the skills on paper but aren’t able to actually put them to use.

How we can do better

My advice for both sides of this equation is to focus on practical skills. Ideally, and what will surely be coming at some point, we’d be able to reverse engineer what good security people look like by taking a data science approach to their attributes.

Hmm, turns out the best security people are from Wyoming, are left-handed, and hate the color yellow.

But humans are horrible at this kind of big-data analysis. We’re stupid little bias machines, and that makes us likely to include and exclude people for all the wrong reasons. We can fight those inclinations though, using a methodology.

What we need to do is turn the hiring practice around completely, and start hiring for the things we care about instead of some arbitrary, old-world notions that probably never worked in the first place.

Don’t ask if they have a degree: ask them how they think the world works.

Don’t ask them if they’re an A student: ask them what they have built lately.

Don’t ask them if they can program: ask them to show you some code.

Don’t ask them if they’re good at problem solving: ask them to solve a problem with you.

Filter for what they’re actually going to do be doing on the job.

Advice for hiring managers

Make a list of the attributes that your best security people have

Make a list of the attributes that your worst security people had (hopefully they’re not there anymore)

Rebuild your entire interview process based on finding those attributes

If they are going to be coding, ask to see recent code they made

If they’re going to be making tools, ask them about a recent tool they made, and why they made it that way

If they’re going to be hacking stuff, ask them how they would hack a given thing, and then let them do it in a live CTF environment

If they’re going to be doing documentation and communication, explain a complex technical and political situation to them, and have them write the documentation and emails that will be used to make all sides happy

Advice for people trying to get into the field

Stop focusing so much on how you look on paper as a candidate, and start thinking more about what you can do as a candidate

Have a lab—either at home or in the cloud

Have projects that you can talk about

Have a blog where you write up the projects you’re working on

Be active on Twitter where you are interacting with people with similar interests, where you give help to others, and where you share your projects

Have an active Github account where you’re sharing your projects, and where you’re helping others with theirs

The one offering assistance and asking for help with your own projects.

The great thing about this approach—on both sides—is that it’s quite hard to fake.

If someone has an active website, a lab, multiple projects in Github, and they’re spending good amounts of time on Twitter talking enthusiastically about their craft—that’s someone you want to hire.

They could be a high-school student or a Ph.D—you want to hire that person. And that’s kind of the point: a bad interview process could still miss this candidate.

So what’s your work experience?

This same total-badass-in-the-making can completely screw up that question, and basically say:

Um, nothing sir. No experience. Just stuff I do on the side.

Pass.

That’s what’s wrong with the system. People asking the wrong questions, and people giving the wrong answers to the wrong questions.

In both cases, focus on the practical.

It’s not about how someone looks on paper. It’s about what they can actually do. And the best way to know that is to look at what they’ve done already.

—

I spend between 5 and 20 hours on this content every week, and if you're someone who can afford fancy coffee, please consider becoming a member for just $5/month…

Thank you,

Daniel

October 6, 2018

On the History of Watches

I recommend reading this in its native typography at On the History of Watches

—

The NOMOS Tangente

Some friends just commented about a video on Twitter where a watch guy basically described why real watches are real watches, and technology-based watches like the Apple Watch don’t qualify. You should take a moment to watch the video.

I agree with many of his points, and I’ve recently consumed a number of similar opinions from similar people. There was a great review and podcast over on Hodinkee, which included comments by John Gruber, and they all seemed to have the same basic takeaways.

But this video above kind of jumped around making a series of very different points—some of which were good, and some that I think were mistaken. The reason some were off and others were accurate is because like the other watch purists he’s not addressing the core issue. Instead he’s dealing with effects of the issue, like treating symptoms instead of cause.

I know now how sacrilegious it is to merge motion with quartz, but I still think it’s cool.

Let me also say that I am a watch person myself. I’ve been categorically obsessed with watches since junior high school. I started with Casio watches like the original G-Shock (which I still have an affinity for), and then moved into Seiko after high school. I was super into—and still have—the first generation of Seiko Kinetic watch, which used arm motion to charge the battery that powered a quartz movement.

A newer model Seiko Kinetic

In the early 90’s I already knew what my ultimate watch was—the Submariner. In fact, here’s a blog post I wrote in 1997 talking about how I would eventually get one.

I have the stainless black Sub with date, circa 2012, show below.

I got that dream watch in the early 2000’s, and it remains my canonical and ultimate watch. I was set on getting a NOMOS Tangente for a while, but because I basically only wear my Apple Watch now I think I might abandon that plan.

My favorite watch of all time

But I never wear my Submariner. Not anymore.

I think I don’t wear my Submariner because I’ve read too much evolutionary psychology, and I therefore understand a lot more than the average person about why people do things—including myself.

I love how I feel when I wear my Submariner. It makes me feel good. It makes me feel good even if nobody is around, so it’s not all about broadcasting to others, but that’s a major part of it. I’m reminded of a quote, which reminds me of all sorts of people, including myself at various times.

Many a peacock hides his tail from all eyes–and calls it his pride.

Friedrich Nietzsche

I’m honestly not completely over this. I drive an M3. I wear fairly nice clothes. And I generally like to surround myself with nice things.

But there is no calculus that I can perform that isn’t either 1) some sort of internal confidence bolstering, or 2) a type of evolutionary value signaling that tells people what I’m about, how cool I am, etc.

That’s not just me, that’s everyone. You should read this book called Spent, which goes into how evolutionary psychology basically weilds us like sock puppets.

My favorite book on evolutionary psychology

Anyway.

Ultimately, when deciding to do one thing or another, you have to weigh the benefits and downsides of each. With my Apple watch I get the following:

Stay up-to-date with my appointments

Track my movement and exercise to make sure I’m being healthy

Can change faces based on mood and utility

Can change bracelets/bands based on mood and utility

That’s a lot of upside.

What’s the upside of wearing my Submariner? I’m going to write these out freely, without thinking or filtering.

Wow, timeless is a pun since it can lose or gain minutes per month.

It’s more timeless in the sense that if you’re doing anything old, traditional, or that you want to last for a long time (like pictures), you want to wear it rather something that can be dated easily.

It communicates taste to others who have taste. So it’s a way of raising your status with others of high status.

It communicates superiority to those who only have enough taste to know it’s better than anything they would wear, but not enough to fully understand why (or to be able to afford one).

It gives me a feeling of accomplishment and history, since I wanted this watch when I had nothing, and now it’s a symbol of having made it.

It’s a piece of art and engineering. It can last for decades and decades and still perform it’s nearly singular function.

It has the feeling of being rare and difficult to make, like it’s special in some way (which turns out not to be true)

Anyway, those are some of the reasons I would have worn my Submariner in the past. I personally am not the condescending type, so I don’t riff off the superiority bit much, but all of the others were present to some degree.

Wearing my Submariner reminds me of walking into a bookstore. It just makes me feel better about myself and the world. Like I’m doing ok…and my potential is infinite.

Watches have always straddled the line between form and function, and the move to wearable computers will not be any different.

But watches didn’t start out that way. They started out as a way to tell the time. They started out as functional, and over time they became (like anything else kept on the body) an indicator of values, class, etc.

Ultimately, anything you keep on your person and take into public is a signal of what you represent and want people to associate with you.

If you wear a $10 Timex that’s because you want people to know you’re frugal, or you might not actually care what people think. But that’s actually remarkably rare. You can tell people who actually fit into this category, and most people reading this are not that person, if they’re really being honest with themselves.

So when you have the choice of different types of form (design) and different types of function (capabilities), and you make your choice, you are doing so as a reflection of what you actually need and what you want others to think of you.

That’s just reality, and this is readily apparent to anyone who learns even a little about evolutionary psychology.

So, when it comes time to wear a beautiful mechanical watch that keeps horrible time, doesn’t know anything about your appointments, and can’t help you be more healthy, you have to ask yourself what you’re getting in return.

In my opinion, the tradeoffs are so severe in the function category that they can only be offset by an extraordinary weight on the signaling side of the scale.

Watch people—meaning people who claim to be such purists that they won’t wear a computer on their wrists—are simply making the decision to choose their watch fam and all the status, inclusion, and deeply fulfilling condescension that comes with it.

They want to signal that they are into something that others don’t understand or cannot afford, because that signaling attracts others who have similar values, and thus puts them in a superior position in their social circles.

That’s just life. It’s not bad. You can’t fault them for it. And that’s not the purpose of this piece. I’m simply trying to explain the underlying machinery to this entire debate.

If you wear something on your wrist, and you say you do so because it performs a function, then you should obviously want to wear something that performs a better function.

If you decline to use a better functioning tool, then there must be a non-functional reason for staying with the old one—it’s that simple. And the reason for watch people to wear pocket watches on their wrists is that they’re functioning as jewelry.

Anyone want to guess what the purpose of jewelry is? Yes—signaling your status to others.

Sure, it makes you feel good, but that’s because of the signaling, not the other way around.

And while we’re on the topic, what do you think the pocket watch people said about the people who wanted to strap a watch to their wrists? I’m not an expert on the topic, but I’m guessing they were viewed as a bunch of absolute savages.

Everything new is savage compared to the old.

Wearing computers on our wrists doesn’t currently allow us to adequately signal to others how rich or awesome we are. That’s a downside of course, but it’s very early in this cycle of wearable tech compared to the history of watches.

I’m sure many companies will release many tiers of wearable tech that can adequately differentiate you in terms of values and class—which is largely what sells.

The function matters, but not nearly as much as the form. We already have computers in our pockets after all.

To sum, watches for WatchPeople™ have become jewelry that tells time poorly, signals their values and tastes to like-minded collectors, and tells everyone else that they’re just a little bit better than you.

I’m ok with that. I get it. Part of me is that person—even today. And I’ll absolutely keep my Submariner for the occasional wear. But I see this entire conversation on the scale of human time.

At that scale we’re talking about the timeless jockeying of form and function. And in that battle, I see wearable tech completely dominating the limited capabilities of wrist-worn pocket watches very soon—if it hasn’t already.

But I’ll still never get rid of my Submariner.

Notes

There’s another element of watches that has universal appeal, which is the advantage of old things vs. new things. Heirlooms are valuable in part because of how old they are, and things have value based on time we’ve spent with them, what they’ve been through, etc. This is an advantage of jewelry over technology, but let us not confuse that with function.

There are some hybrids of form, function, and timelessness such as watches and certain old cars, which generate a certain type of happiness in collectors. But notice that they usually don’t drive those cars to work because they don’t have seat belts, anti-lock brakes, or many of the other things we need from a car. It’s the same with watches. And also notice that the main pastime of people with old car collections is showing them to other people so that they’ll be appreciated. Did I mean the cars or the owner? Hard to say.

There’s also the fact that watches like the Submariner aren’t that unique, or hard to make. Their main allure is still that they’re still only owned by a small percentage of people who can afford a $10,000 watch. But if you spend any time in airport clubs you’ll see that Rolexes are basically standard issue.

—

I spend between 5 and 20 hours on this content every week, and if you're someone who can afford fancy coffee, please consider becoming a member for just $5/month…

Thank you,

Daniel

September 28, 2018

Preparing to Release the OWASP IoT Top 10 2018

I recommend reading this in its native typography at Preparing to Release the OWASP IoT Top 10 2018

—

OWASP IoT Top 10 Comparison (Draft)

The OWASP Internet of Things Top 10 has not been updated since 2014, for a number of reasons. First of which was the fact that we released the new umbrella project that removed focus from the Top 10 format. This, in retrospect, seems to have been a mistake.

The idea was to just make a vulnerability list, and get away from the Top 10 concept.

As it turns out, people like Top 10 lists, and things have changed enough in the last few years that the team has been working this year to update the project for 2018.

The 2018 OWASP IoT Top 10 (Draft)

This is what we’ve come up with so far, and I wanted to just talk through some of the philosophy and methodology for this year’s release.

Philosophy

So the philosophy we worked under was that of simplicity and practicality. We don’t believe the big data approach works as well as people hope it would, i.e., collecting datasets from hundreds of companies, looking at hundreds of thousands of vulnerabilities, and then hoping for the data to somehow speak wisdom to us.

The quality of the project comes from picking great team members who have the most experience, the least bias, and the best attitudes toward the project and collaboration

Many of us on the team have been part of the OWASP rodeo for quite some time, and what we’ve learned over the years is that ultimately—no matter how much data you have—you end up relying on the expertise and judgment of the team to create your final product. At the end it’s the people.

That being said, we wanted to take in put from as many sources as possible to avoid missing vulnerabilities, prioritization, that others have captured elsewhere. We basically took it as a philosophy to be the best of what we knew from everywhere in the industry—whether that’s actual vulnerability data or curated standards and guidance from other types of IoT project.

What kind of widgets are these?

One thing that we deliberately wanted to sidestep was the religious debates around whether to call these things in the Top 10 vulnerabilities, threats, or risks. We solve that by referring to them as things to avoid. Again, practicality over pedantry.

Who is the audience?

The next big consideration from a philosophy standpoint was looking at who this list is meant to serve. The classic three options are developers/manufacturers, enterprises, and consumers. One option we looked at early on was creating a separate list for each. We might still do this as a later step, but having learned our lesson from removing the Top 10 we decided it’s hard enough getting people to focus on a single one—so three would make it at least three times as hard.

So the 2010 IoT Top 10 is a composite list for developers/manufacturers, enterprises, and consumers.

Methodology

Given that as a backdrop, here are the source types we ended up using to collect from and start analysis.

A number of sanitized Top N vulnerability lists from major IoT manufacturers.

Parsing of a number of relatively recent IoT security standards and projects, such as CSA’s Future-proofing the Connected World, ENISA’s Baseline Security Recommendations for IoT, Stanford’s Internet of Things Security Project, NIST’s Draft 8200 Document, and many more.

Evaluation of the last few years of IoT vulnerabilities and known compromises to see what’s actually attracting attention and causing damage.

Many conversations with our networks of peer security and IoT experts about the list, to get feedback on priority and clarity.

We very quickly saw some key trends from these inputs.

The weak credential issue stuck out as the top issue basically everywhere

Listening services was almost universally second in all inputs

Privacy kept coming up in every list, project, and conversation

These repeated manifestations in projects, standards, and conversations lead to them being weighted heavily in the project.

Prioritization is critical

And that brings us to weighting.

We saw the project as basically being two phases—collecting as many inputs as possible to ensure that we weren’t blind to a vector, vulnerability, category, etc., and then determining how to rank the issues to do the most good.

Naturally the ratings are based on a combination of likelihood and impact, but in general we leaned slightly more on the likelihood factor because the main attack surface for this list is remote. In other words, it might be (and usually is) much worse to have physical access than to have telnet access, but if the device is on the internet then billions of people have telnet access, and we think that matters a lot.

This is why Lack of Physical Hardening is I8 and not I4 or I5, for example.

So our weighting was ultimately a combination of probability and impact, but with a significant mind towards how common an issue was, how available that issue usually is to attackers, and how often it’s actually being used and seen in the wild. We used our vulnerability lists from vendors to influence this quite a bit, seeing that as a signal that those issues are actually being found in real products.

The ask of you

So what we have now is a draft version that we’re looking to release as final within the next month or so.

What we’d like is input from the community. Specifically, we’d love to hear thoughts on two aspects:

List contents, i.e., why did you have X and not Y?

List prioritization, i.e., you should put A lower, and B higher.

And any other input would honestly be appreciated as well. And if you want to join the project you can do that at any time as well. It’s been an open project throughout, and we’ve had many people join and contribute. We meet every other Friday in the OWASP Slack’s #iot-security channel at 8AM PST.

You can give us feedback there, or you can hit me up directly on Twitter at @danielmiessler.

The team

I really want to thank the team for coming together on this thing. It’s honestly been the smoothest, most pleasant, and most productive OWASP project I’ve ever been part of, and I attribute that to the quality and character of the people who were part of it.

Thanks to Jim Manico for the input as well!

Vishruta Rudresh (Mimosa): Mimosa was extraordinarily awesome throughout the entire project. She was at virtually every meeting, and took over meetings when I could not attend. Her technical expertise and demeanor made her an absolute star of a team member.

Aaron Guzman: Aaron is an OWASP veteran and all-around badass in everything IoT Security. His input and guidance were invaluable throughout the entire process.

Vijay Pushpanathan: Vijay brought his significant IoT security expertise and professionalism to help provide constant input into direction and content.

José Alejandro Rivas Vidal: José was a consistent contributor of high-quality technical input and judgement.

Alex Lafrenz: Significant and quality input into the list formation and prioritization.

Craig Smith

Daniel Miessler

HINT: No egos.

Seriously—I wish all OWASP projects could be this smooth. The team was just phenomenal. If anyone wants to hear how we managed it, reach out to me and I’ll try to share what we learned.

Summary

We’re updating the OWASP IoT Top 10 for the first time since 2014.

It’s a combined list of vulnerabilities, threats, and risks.

It’s a unified list for manufacturers/developers, enterprises, and consumers.

Our methodology was to go extremely broad on collection of inputs, including tons of IoT vulnerabilities, IoT projects, input from the team members, and input from fellow professionals in our networks.

We combined probability with impact, but slightly favored probability due to the remote nature of IoT.

We need your help in improving the draft before we go live sometime in October.

Thank you!

—

I spend between 5 and 20 hours on this content every week, and if you're someone who can afford fancy coffee, please consider becoming a member for just $5/month…

Thank you,

Daniel

September 22, 2018

Humanity’s Ultimate Red Pill

I recommend reading this in its native typography at Humanity’s Ultimate Red Pill

—

Man can do what he wants, but he cannot will what he wills.

Arthur Schopenhauer

One of the most powerful concepts in the Matrix was the idea that people were separated into two gropus: those who could only see the world as it appeared, and those who could see its true form.

I am saying 5% because of countries like China that have large educated and secular populations. If it weren’t for them I think this would be far below 1%, as I’m sure it is in the U.S.

I am about to give you a similar test, except this one applies to reality. I am guessing that less than 5% of humans on the planet will choose correctly.

In the movie, the two states were the blue pill, which was inside the virtual reality created by the machines, and the red pill where the people and machines physically existed.

The part that people generally can’t handle is the realization that you have spent your whole life thinking you were in one, when you were actually the other.

Humans on Earth can take one of two pills regarding their belief in their own autonomy:

The nested matrix of DNA-compelled desires

The Blue Pill: You are an independent, rational individual who wants to do things of your own free will, e.g., to do well at work, to have kids or not, to be a good person or not, etc.

The Red Pill: Evolution created every desire you have as a human, and your entire life is simply carrying out those desires as expressed in your DNA, i.e., you only want what you want because evolution compels you to do so.

What makes people want to have children? What makes you desire certain people? What makes you want to feel strong or attractive? What makes you want to improve yourself?

And could you stop wanting those things?

Could you simply wake up tomorrow and prefer to date a different gender, or a different kind of person within that gender?

Nothing is more fundamental to a character than their desires, and the truth is that our desires are given to us, not chosen by us.

The answer to all these things is, “No”.

We don’t decide to have a good work ethic, or lots of self-discipline, or to be a good parent. We have those things in our DNA, and they are taught to us by people who had those same two things in them as well.

Humans are the hand puppets of Evolution.

But that’s just the beginning of our story, not the end of it. It’s true that humans are stuck within an absurdist framework with regard to programming from evolution, DNA, and our environment, which ultimately results in a complete lack of free will.

That’s ok, because we operate inside of that reality. And inside that reality we still have all the things that make life wonderful. We still experience choice, and freedom, and beauty, and all those other wonders of being alive.

I just consider it fascinating that this base-level, fundamental truth about the reality of human life is not accepted—or even thought about—by most people.

I think this will take another 100 years, and that’s assuming we don’t go backwards due to some sort of global catastrophe.

I think it’s a good benchmark for ultimate human progress on a very long timescale. When this Evolutionary Hand Puppet (EHP) number for the planet hits something like 50% I think we’ll be in a lot better shape as a civilization.

Right now I’m guessing it’s below 1% for the United States, less than 10% for Western Europe, and perhaps only significantly understood in China.

How many people in your circle of friends accept the EHP hypothesis? I have pretty smart friends and loved ones, and I think only one or two of them are all the way there.

So fascinating to me.

—

I spend between 5 and 20 hours on this content every week, and if you're someone who can afford fancy coffee, please consider becoming a member for just $5/month…

Thank you,

Daniel

September 16, 2018

How I Reduced My Spam Phone Calls by 90%

I recommend reading this in its native typography at How I Reduced My Spam Phone Calls by 90%

—

Many of the calls are actually in Mandarin, which I don’t speak.

Over the last few months I’ve seen my spam phone calls go from around one a week to like ten a day, and it’s been infuriating.

After a good bit of Googling, I ended up coming up with two solutions that reduced the problem by around 90%.

Put Yourself on the Do Not Call List

A lot of spammers ignore the Do Not Call List, but many do honor it. It’s not possible to really know the ratio there, but being on the list will definitely reduce the number of calls you get to some degree.

This one is obviously AT&T only, but there are similar apps for other carriers below.

AT&T Call Protect

AT&T Call Protect is a carrier-provided app that automatically filters spam and fraud calls, and has a mobile app to help you manage it and see what it’s blocked.

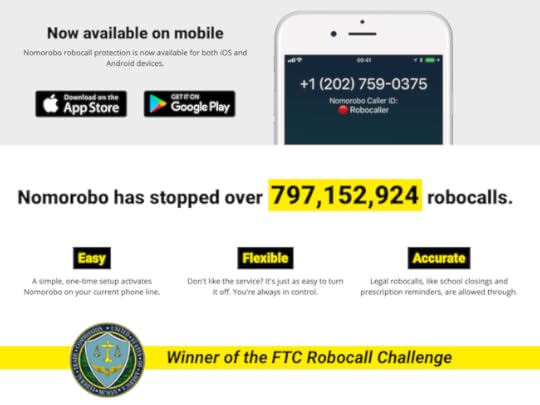

Nomorobo

Nomorobo is a third-party app that I settled on after trying 3-4 alternatives. I actually liked the look and feel of some of the others much better, but this one seemed most effective at stopping calls when combined with AT&T’s offering.

For non-AT&T customers

Advice from Verizon

Advice from T-Mobil

Advice from Sprint

Summary

This is a cat and mouse game, and the spammers are always adjusting, but this has helped me massively, and it should work for you as well.

—

I spend between 5 and 20 hours on this content every week, and if you're someone who can afford fancy coffee, please consider becoming a member for just $5/month…

Thank you,

Daniel

September 13, 2018

Stop Trying to Violently Separate Privacy and Security

I recommend reading this in its native typography at Stop Trying to Violently Separate Privacy and Security

—

I just stumbled upon an article by Mark R. Heckman, Ph.D, CISSP, CISA that—like so many others in the industry—wildly contorts himself to make a distinction between security and privacy. He writes:

I argued here why I don’t think this difference matters as much as people think.

Without a clear understanding of the difference, data security and privacy is often conflated in ambiguous and imprecise policies.

Mark R. Heckman

He then goes on to give some definitions: first from the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP):

Data privacy is focused on the use and governance of personal data— things like putting policies in place to ensure that consumers’ personal information is being collected, shared and used in appropriate ways. Data security focuses more on protecting data from malicious attacks and the exploitation of stolen data for profit. While security is necessary for protecting data, it is not sufficient for addressing privacy.

IAPP

Then he gives what he calls a better definition, from the US Department of Health:

The Privacy Rule sets the standards for, among other things, who may have access to PHI, while the Security Rule sets the standards for ensuring that only those who should have access to EPHI will actually have access.

US Department of Health

He’s using both definitions to set up his ultimate argument, which is that:

Data Security is enforcement of the authorized access rights currently in the access table, and Privacy is a policy on control over where and when authorized access rights appear in the table.

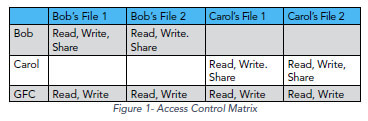

And he provides some tables to illustrate this.

And finally he goes on to say:

Privacy is not the state of information being protected from unauthorized access. Information is not private because unauthorized users are prevented from accessing the data, but it is secure. People frequently conflate confidentiality – the property that only authorized users can read protected information – with privacy. But as the access control matrix model clearly shows, confidentiality is a security policy.

Professor Mark R. Heckman

I have to say, I find this truly perplexing. Especially coming from a professor, with a Ph.D, who’s been in security for 30 years.

What exactly is the obsession with drawing such a bright line between these things?

There is clearly some kind of difference between Security and Privacy, but there are also differences between being a firewall engineer and an endpoint security specialist. Same with being a red-teamer vs. a compliance person.

These are all different things, but they’re all part of cybersecurity / information security.

Why is that?

Let’s look at the definitions of information security.

Information Security

noun

Information security, sometimes shortened to InfoSec, is the practice of preventing unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, inspection, recording or destruction of information. It is a general term that can be used regardless of the form the data may take (e.g., electronic, physical).[1] Information security’s primary focus is the balanced protection of the confidentiality, integrity and availability of data (also known as the CIA triad) while maintaining a focus on efficient policy implementation, all without hampering organization productivity.

Hmm, so, the prevention of unauthorized access, use, and disclosure of information? Do we need to look up what unauthorized means? I think it means people accessing or using a given set of data that aren’t supposed to.

Does that remind you of anything?

Professor Heckman is essentially arguing for a massive separation between these two terms, so that this can be spelled out in separate policies—all because there is evidently some sort of tangible problem today being caused by their conflation.

I’ve never seen that in my 20 years of consulting.

I’ve never seen a single person be confused by what it means to protect sensitive data. It’s common sense. The problem that companies actually have is not knowing where their data is, who has it, what its classification is, who has access to it, etc. It’s a data inventory problem, not an issue with confusing security and privacy.

Information Security means protecting data from unauthorized access and use, and privacy means ensuring that only authorized people can have access to peoples’ private data. Kind of similar, right?

These are not any different than database security vs. filesystem security, or firewall people vs. WAF people, or incident response people vs. compliance people.

You can have specialization within a field without needing to call it a different species altogether, and Privacy specialists are a good example of that.

Do they have different skillsets? Sure. Do they take different training? Sure. Go to different conferences? Fine. But are they fundamentally doing different things? Is one in security while the other isn’t?

No.

The final (and worst) point in his argument is that information is Secure when it’s protected according to policy, but that it’s Private when the owner can update who has access. This actually highlights how weak the overall separation is.

In his conclusion he writes:

Information is “secure” when a system correctly enforces the access rights currently in the matrix. Information is “private” only when the owner of the information has control over changing the rights in the matrix for the owner’s information.

Professor Mark R. Heckman

What?

Who has ever heard of an information security policy that says the Information Owner cannot define who has access to their own data?

Seriously? That’s what he’s using as a distinction?

So if you’re an InfoSec professional protecting some data, and the Data Owner says that the business or the customer is asking for some authorized party to have access—and it’s all legitimate—do we really think the answer is going to be no?

What reality is this?

Evidently a reality where there’s some kind of artificial boundary that says Security is enforcement of data security policy, while Privacy is the updating of the policy.

People. Please. Stop with this.

Information/Data Security is the art and science of making sure only the right people can access sensitive data. The extremely natural and obvious prerequisite to that is making sure the right policies—as defined by the data owner—are on that data. And yes, and that means keeping them updated.

Stop drawing such sharp lines when they’re not needed in the real world.

Let’s focus all this Pedantic-Chi Energy on finding, classifying, and protecting the data in the first place. That’s what companies actually need help with.

—

I spend between 5 and 20 hours on this content every week, and if you're someone who can afford fancy coffee, please consider becoming a member for just $5/month…

Thank you,

Daniel

September 12, 2018

Feedly Feature Request: Custom Long-press

I recommend reading this in its native typography at Feedly Feature Request: Custom Long-press

—

This post will serve as a feature request for my preferred news reader—Feedly. The feature is called: Custom Long-press

Custom Long-press

pro

Custom Long-press is a feature that allows users to assign an arbitrary function to the long-press action within Feedly. Examples might include sending to the Safari Reading List, Sharing on Buffer, etc.

My current workflow for my weekly show, Unsupervised Learning, is to capture stories throughout the week during my daily reading. I capture those stories within Safari’s Reading List feature because it’s available on all my devices.

The problem is that my current workflow on mobile involves four (4) steps:

Find the story in my feeds.

Select the story.

Click the share button.

Click ‘Add to Reading List’

That’s four steps where I would hope we could get it to one or two.

There’s a good chance that this is actually an API limitation around accessing the proper sharing interface, and if that’s the case then let’s just try to get the number of steps as low as possible, e.g., maybe long-press brings up the mobile platform’s sharing screen?

In the Pro version there’s already a feature called ‘Long Press to Save’, which currently saves the story you long-press into the Read Later queue. I’d love if we could simply re-map this function to other things—most importantly for me: Save to Safari Reading List.

That’s it.

Custom Long-press.

Thanks to the Feedly team for picking up the baton when Google dropped it, and for reading this request.

—

I spend between 5 and 20 hours on this content every week, and if you're someone who can afford fancy coffee, please consider becoming a member for just $5/month…

Thank you,

Daniel

September 6, 2018

How Technology Increases Production Without the Need for Humans

I recommend reading this in its native typography at How Technology Increases Production Without the Need for Humans

—

Over the last several years I’ve been reading extraordinary amounts about the future of artificial intelligence, and how it’ll affect human work. I’ve written about this extensively here, so feel free to explore if you’re interested.

Recently a reader reached out and pointed me to a video by Moshe Vardi of Rice University. The reader was himself a Ph.D. in AI, and he too went to Rice University. Anyway, he said that this lecture he saw there had a major impact on his view of the topic.

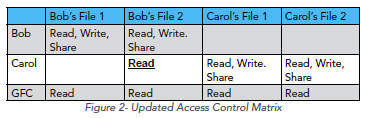

This is an updated version of that talk by Vardi, and one of the rather side points he made in the previous version was a comparison of the top 3 companies in 1990 in Detroit, Michigan vs. the top 3 companies in Silicon Valley in 2016. He basically calculated this across two dimensions: amount of market value, and number of employees working at the companies.

The chart was staggering, so I decided to update it for 2018, and that’s what the chart above shows.

Market value to employee comparison for three top companies in each time

So, for two of the top economically producing regions in the United States, from 1990 to 2018, we went from each employee providing around $54,000 dollars in value, to each employee providing $9,361,000 in value.

That’s roughly 173 times the level of productivity.

So forget AI—let’s take that off the table since it’s just getting started anyway. Just looking at technology and automation we’re seeing staggering amounts of value being created by fewer and fewer employees.

And there’s no reason to think this won’t continue—and accelerate—as ML/AI makes the tech even better at replacing humans.

Notes

I made this graph myself, by hand, using a style copied from Atlas Graphs, which I find to be super clear and visually attractive.

I think I need to factor in inflation as well to make the comparison more accurate.

—

I spend between 5 and 20 hours on this content every week, and if you're someone who can afford fancy coffee, please consider becoming a member for just $5/month…

Thank you,

Daniel

September 5, 2018

My Analysis of the Disconnect Between Sam Harris and Jordan Peterson

I recommend reading this in its native typography at My Analysis of the Disconnect Between Sam Harris and Jordan Peterson

—

If you follow the work of either Jordan Peterson or Sam Harris you’ve no doubt seen them engage each other in various ways over the past year or so. Jordan has been on Sam’s podcast, which didn’t go well. They talk about each other to their respective audiences, and now they have a new video podcast series together in Vancouver, moderated by Bret Weinstein.

I’ve been casually observing these interactions over the last year with some idea of where they’re missing each other, but haven’t felt the need to capture it until now. After watching the first Vancouver discussion I find myself compelled to engage. Their inability to clearly capture their differences has become a splinter in my brain.

What I’m going to attempt to do in this post is succinctly capture what each of them is saying, why they disagree with each other, and then what their audiences—and the world as a whole—actually needs to hear.

Sam Harris’ position

Sam sees harm in believing things that aren’t true, and much of his career is based on fighting those things. In Jordan he hears someone otherwise logical and intelligent (and kind and useful) say 7 good things out of ten, and then use the last three to go off into what basically equates to numerology. I’m not sure if he’s made that comparison, but I think he’d agree with it.

There could be some nuance here that’s not captured, but this is the basic idea of what he was saying.

In their first interaction, the big collision took place because Jordan refused to accept that facts were true on their own—instead insisting that things were only true if they were useful. This sent Sam into orbit, from which he seemed content to rain laser blasts upon Jordan’s head. Since I have known Sam longer, and therefore share more of his intuitions, I too saw this as a major flaw in Jordan, and I still do.

This same dynamic is at play with their new, more fundamental battleground of whether or not we should discard religion outright or whether there’s something useful there to preserve and make use of. Sam’s position is that:

Religion is clearly not true.

It’s often horrible.

Anything that is good and useful in it (which he admits there is some) can be found in other ways that don’t require belief in the supernatural.

For someone as smart as Jordan, with such a large audience, to say that he acts as if God exists, and to refuse to deny things like Jesus being reincarnated, he’s actually enabling and exalting very traditional and unsophisticated belief in religion—not the nuanced, usefulness-based scaffolding that Jordan seems to have constructed.

Jordan Petersons’ position

When I say tricks, I don’t mean that pejoratively. I mean that he is willing to use the various pecularities of the human mind to add valence to prescriptive guidance.

While Sam is first and foremost someone who protects objective truth from the irrational, Jordan is fundamentally someone who wants to help people, and he’s willing to use various tricks to accomplish that goal.

In this sense I actually give Jordan the upper hand here, as I see the practice of providing a prescriptive meaning infrastructure to be more direct and pure than Sam’s approach of helping people discard non-truth.

His entire career is based on finding patterns in stories, narratives, cultures, etc., which he then uses to construct a tangible plan to improve peoples’ lives. And he literally carries out this practice as his day job as a clinical psychologist.

So Jordan sees value in all these traditional stories and narratives, and he wants to use that value to help people. And he disagrees with Sam’s tendency and willingness to discard religions outright because of their downsides.

My analysis

My frustration in watching all this is that the disconnect seems obvious and avoidable. They’re obviously both correct. And they’re obviously both wrong.

Jordan is wrong to hide behind his custom-built, intellectually-nuanced, and utility-based belief system that he’s constructed because it’s obvious to Sam and his audience that to most people that Jordan just looks like a religious apologist.

To religious people who are looking for truth, Jordan is indistinguishable from a religious leader defending their faith.

That’s bad, because now we haven’t made the progress of getting them to decouple their understanding of reality from the belief in the supernatural—and all the negatives that come with that.

What should Jordan do about that? Simple. He should say something like this:

I am not a believer in the supernatural, or in any God, but I do believe that there are powerful forces within us humans, instilled by evolutionary biology, that work and can be controlled in large extent by the use of narrative, ritual, and story. What I have been doing is studying the patterns for these narratives and rituals for decades, and using that knowledge to help people improve their lives.

A possible Jordan Peterson

That to me would solve everything between he and Sam, since Sam has already said that he likes the infrastructure Jordan has built.

To be fair, Sam has mentioned elsewhere that he gets that pepole are asking for something, and that he recognizes that there’s a void there.

And Sam is wrong to downplay Jordan’s extraordinarily noble attempts to provide a semi-rational and culture-based belief system to millions who need it.

Here’s what I think Sam should say:

What Jordan is doing is fantastic. He’s used his knowledge of history, culture, and narrative to construct a meaning infrastructure that has ties to our past, our rituals, and many other elements that we’ve yet to understand out ourselves. My concern is simply that he’s not making it clear enough that he has built a secular system that is not tied at all to supernatural belief. And by not making that clear, while he uses religious language and symbology, it makes it look like he’s simply a new type of religious leader. That’s not helpful, as it keeps us tied to all the negatives that come with primitive religion.

A possible Sam Harris

This is the type of argument that I think Jordan would respond to, and good conversation and change to his behavior would likely come from it.

Summary

Both men are progressives who are doing great work that’s helping many, many people. They’re simply coming at the problem from opposite directions.

Sam Harris’s fundamental drive is removing people’s harmful beliefs.

Jordan Peterson’s fundamental drive is providing positive belief.

This is why they are disagreeing: Sam doesn’t like Jordan sneaking in non-rational structure, and Jordan doesn’t want Sam to strip things away without replacing them with something else.

But humans don’t need another supernatural belief system—or more tacit support for existing bad ones—as that’s just punting from our existing set of horrible choices. But at the same time, humans are suffering right now, and stripping away their false beliefs doesn’t help them as much as the New Atheists probably hoped for. When you strip away, as modernity has done, you must also give something as an alternative, and that need is what Jordan has tapped into.

In short, Jordan should try to become more Sam-like in his clear delineation of the supernatural and the factual, and Sam should try to become more Jordan-like in his willingness to create a meaning infrastructure for those who need it.

Notes

This has been said other places, but I want to celebrate the dialogue that Sam has created, with Bret Weinstein’s help, that was evident in this series of discussions. It used to be that people would show up to watch people engage in dialectic, and I am overjoyed to see this as a possible form of entertainment (and enrichment) again. The fact that we can even have this type of dialogue, i.e., one in which people actually have good faith, mutual respect, and are willing to change their opinions at all, is spectacular on its own. So thank you to Sam, Bret, and all his guests that have been participating in this new type of discourse-based entertainment.

Another point that’s been made elsewhere, but Bret Weinstein added a dimension to the discussion that I’ve never seen before in a moderator. He was like a third participant, which is normally not allowed, but performing the moderator role. I think this might signal a pivot point in moderated discussions, assuming one can find people of Bret’s quality, where the third person is of the same caliber as the two participants but opts to serve the two rather than his own opinions. Bret was more than capable of being one of the two primary participants in this conversation, for example. But he chose to help them have a discussion. The positions could have been rotated, and the topic changed, and I think it would have gone equally as well. This should perhaps become a new paradigm for discussion, where the third person is not merely a referee, but rather a facilitator who is also an equal.

—

I spend between 5 and 20 hours on this content every week, and if you're someone who can afford fancy coffee, please consider becoming a member for just $5/month…

Thank you,

Daniel

Daniel Miessler's Blog

- Daniel Miessler's profile

- 18 followers