Daniel Miessler's Blog, page 120

July 7, 2017

If Putin Ran Against Obama in Middle America

I think if Putin ran for President against Obama, and the only electorate was white, christian, middle America, Putin would win easily.

Here are some reasons.

At least Putin wouldn’t sell out America

At least Putin is a god-fearing Christian

We need strength, not weakness

We need someone who can make us respected again

Putin might be bad, but at least he’s not a communist

(or black)

These reasons would get him elected—in 2017—by millions of people in rural America.

Don’t blame candidates like Trump. They’re the symptom, not the disease. The disease is millions of dumb people who vote against their own interests, and the interests of America as a whole, due to ignorance and bigotry.

Notes

Yes, I know ignorance and bigotry are not the ONLY reasons people vote for candidates like Trump. But I’m as convinced as ever that they’re the primary reasons.

__

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I curate the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

If You Believe Nothing You Can Be Convinced of Anything

My Attempt to Explain Why People Voted for Trump

How I Became an Atheist

An Atheist Debate Reference

The Bible is Fiction: A Collection Of Evidence

July 5, 2017

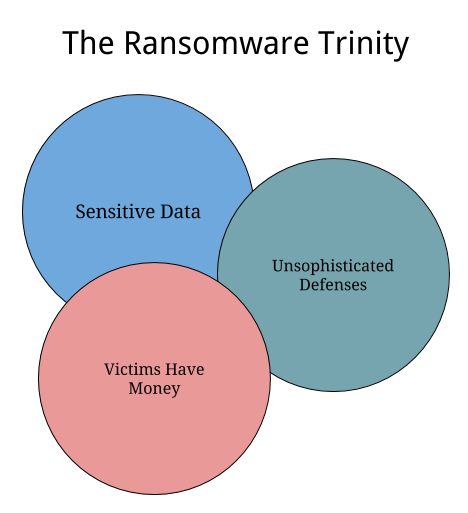

The Ransomware Trinity

There are three things that industries ravaged by ransomware tend to have in common.

They have data that is sensitive enough to be protected.

The industry lacks mature defenses.

Someone in the victim ecosystem is willing and able to pay.

Where we’ve seen this so far are places like:

Hospitals

Schools

Small businesses

Home users (to a lesser extent)

But if you look at those criteria I think you can predict new places that will be targeted in the future. One I think is ripe for it is:

Law firms

Think about the data they have. Think about how much effort they’re spending on security. And think about how much money they have to pay ransom.

It’s the perfect mixture.

What other industries should we be watching out for and getting ready to protect?

Notes

This also applies to Extortionware, if that ever becomes a thing.

Please do your best not to notice that there is no overlap in this Venn diagram. I blame Google Docs for not having a Venn function. You should too.

__

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I curate the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

How to Build a Successful Information Security Career

Ideas

My Explanation for the Sudden Rise in Ransomware

An Information Security Metrics Primer

My RSA 2017 Recap

July 4, 2017

The Future of Pentests, Bug Bounties, and Security Testing

People are very confused about the bounty vs. penetration test debate. They see fundamental differences that don’t actually exist, and they’re blind to what’s actually coming.

The reality of testing needs can be reduced to a few key variables, which exist on a spectrum.

Good vs. bad testers

Many testers vs. few testers

High vs. low business context

Paid by finding vs. by report

High tester trust vs. low tester trust

The future

Rather than giving my ideas about the future of testing, let me tell you what I believe to be the future of IT. Combined with the testing variables above the path should illuminate itself.

Businesses will eject most internal IT functions, preferring to use vendors instead.

The business will retain a small number of super elite IT people who are extremely fluent in both business and IT.

These business/IT (BIT) people will manage vendors in order to best achieve the goals of the business.

90% of IT workers will work for vendors / consultancies.

Infosec becomes vastly more data-driven in terms of what works for security and what does not, driven by insurance companies being the first groups incentivized to collect and use this information.

Insurance companies will determine the infosec standards because they will have the data about what works.

Because they will have the data, they know that certain projects need certain types of testing, and other types need other approaches.

Based on the type of project you have, the project’s business sensitivity, how many times its been assessed in the past, etc., there will be a best-fit type of assessment for that project.

The variables will be:

How sensitive the project is, i.e. the trust level of testers required to work on it.

Automated vs. manual testing.

How many testers are used.

Incentivization / payment structure.

The knowledge of the business required to provide valuable results.

The BIT person will reach out to several vendors and request an assessment with the precise mixture of these components.

Some vendors will excel at specific areas, such as high-trust testers, or testers who know a particular business, but the trend will be towards large companies that can do all of them.

Many large testing vendors will really be exchanges that can find any combination of individual to fit a given need.

The BIT will pick one vendor that has the best mix, and the work will get done.

Back to the present

So the future of testing is not a race to differentiation, it’s a race to similarity. Both penetration test companies and bounty companies need to become flexible enough to handle this entire range of capabilities.

Some assessments need highly vetted people, even if it’s just one or two. Other assessments need large numbers of people, no matter their background or alignment. Some require deep relationships with, and knowledge of, the customer. Others need no context whatsoever.

The truth is, as a BIT, you don’t care who you’re using as long as you can trust the results and that they’ll be professional. If you can provide better results, and better guidance on how to reduce risk for the company—all without breaking that precious trust that the whole thing is based on—you will do well.

Now, who do you think is better positioned to make this move?

Or, put another way, is it easier for:

Security services companies with deep relationships with companies built over years or decades to add a researcher program that brings hundreds or thousands of testers under their banner at varying levels of trust, and to then build/buy a platform for taking managing them finding bugs for their customers, or…

For companies based around a vulnerability platform to build the internal trust required to be trusted for ANY type of project the customer has?

I think it’s it’s the former. It would seem to be easier for a trusted security services company to add testers than for pure-play bounty companies to engage deeply into companies as a trusted advisor. But either way, that’s what the race looks like. And both company types must ultimately do both or face extinction.

Longer term It’s all about the testing talent

The funny part is that, long term, it actually doesn’t matter which model wins between pure-play bounty and traditional testing companies. The race described above is only on the 2-10 year scale. The next evolution of the future of work presents a threat to testing companies themselves—traditional, bounty, or whatever. Ask yourself this:

Who are the most important parties in the testing conversation?

The tester and the customer.

Everyone else is a middleman, i.e., a bunch of taxi companies in a world of ride sharing.

There is, of course, a component of, “Who are you going to sue if something goes wrong?”, and right now that dynamic heavily favors having a reputable testing company (not a bounty company) between the tester and the customer. But as the individual-based economy (and the technology-based trust infrastructure that powers it) gains acceptance, this will quickly decline as a factor.

As I talk about in The Real Internet of Things, individuals will be rated by trust, by quality, by how pleasurable they are to work with, etc., and they will win or lose contracts based on this rating.

As the infrastructure grows for tracking such meta, including one’s trustworthiness, how well they perform, how well they communicate, etc., having the middle-person will be needed less and less. The better the middle tech layer becomes at finding matches and ensuring quality, the less a third party is needed between the customer and the actual provider of the service.

In short, both the traditional testing and bug bounty companies represent the old, taxi model of staffing security engagements, and they’re both going to be replaced by the individual-based gig economy.

That’s why I laugh when I see the industry so obsessed with the distinction between being penetration tester, a researcher, a bounty player, or whatever specific title we wish to assign. In an individual-based economy this distinction becomes arbitrary.

Testers will be testers with a set of skills. They might have a regular-ish job with a particular company, while they’re also doing other contracts on the side, while they’re also pursuing their own research as well. What are they? Pentesters? Bounty people? Researchers?

Yes, yes, and yes.

The future of security testing is individual-based and non-binary, and if you’re a third party in between them and the customer, you’re going to be in a bad position.

Summary

People are far too emotional about the bounty vs. pentest debate, usually because of bias.

The industry is actually racing to similarity, with all companies having many testers and many trust levels.

In the longer-term future it won’t even be about pentest or bounty companies because testers will be non-binary participants in the gig economy.

In this model, both types of companies become part of the past because they are third-party middlemen in a gig-based transaction.

This is why I can’t get too worked up about the bounty vs. pentest debate anymore. In the overall story arc of where security testing is going, it’s a moot point. Both models are intermediary, and the future is coming.

I look forward to the purity that individual-based testing will bring. It will simply be people with skills and reputations being harnessed to solve problems. And that’s the future of work, not just security testing.

Let’s stop fighting about who’s better at the old models, and start thinking about how to get to the new one.

Notes

Keep in mind that this transition will take time and will have many different phases. There will still be entities that pop up to pre-filter resources, like exchanges, that companies can buy from. But all of these solutions are temporary fixes to the technological problem of purchasers not being able to fully trust the rating systems. As those systems approach a realistic representation of quality and trust, the third-party vouching and liability services will become less needed and less valuable.

Insurance will be another solution to the liability problem. I can imagine a thriving insurance market where highly rated individuals run with insurance policies that help their clients relax about using them. So not only will they have high ratings in dependability, trustworthiness, and results quality, but they’ll also be covered for millions of dollars in the event of something bad happening. This will further diminish the need for a third party in the middle to take on liability.

I’ve had these thoughts for years now and have been reticent to share them. For one, I work at a testing company. Second, one of my favorite humans in the world (Jason Haddix) works at Bugcrowd, and my buddy Jeremiah Grossman is an advisor for them as well. Plus I have many other friends there that I care about, so I want to see all of them, as well as my own company, thrive. But there’s politics surrounding the topic—politics that get worse when marketing departments get involved and start slinging poo at each other. This happened recently, coming from the bug bounty companies, and I decided to write this as a reminder that the whole debate is an exercise in deck chair placement on the Titanic. Let’s be smarter and better.

If you’re wondering where this meta on individuals will be stored, such as their testing quality, their trustworthiness, their dependability, etc., I think the answer is in large, universal tech layers like LinkedIn, FICO, Insurance companies, etc. It’ll be all about massive databases of people, transactions, ratings, and fraud detection and defense. These companies will link job seekers with job providers, and everyone will run the WORK app on their phone like ride share drivers do now. Except it’ll be for all of your skills, not just one of them. This is how testers will find gigs—they’ll come to them automatically based on the customer’s need combined with their skillset, just like Uber and Lyft find drivers based on where you need to go, at what time of day, for how many people.

Many of these concepts are talked about in more depth in my book, The Real Internet of Things.

There will still be a place for companies that provide vetting services, but those services will not be consumed as sources for contractors, but rather authoritative tagging of resources with a seal of quality. So rather than saying, “Go get me N testers from X company.”, it’ll be, “Find me N testers who have the following criteria plus the X seal of quality given by Y service.”

__

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I curate the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

Web Application Security Testing Resources

Information Security Assessment Types

How Cybersecurity Insurance Will Take Over InfoSec

Ideas

Bug Bounty Ethics and the Ubering of Pentesting

The Truth About the Future of Pentests, Bug Bounties, and Security Testing

People are very confused about the bounty vs. penetration test debate. They see fundamental differences that don’t actually exist, and they’re blind to what’s actually coming.

The reality of testing needs can be reduced to a few key variables, which exist on a spectrum.

Good vs. bad testers

Many testers vs. few testers

High vs. low business context

Paid by finding vs. by report

High tester trust vs. low tester trust

The future

Rather than giving my pitch now, let me just tell you what I believe the general future of IT looks like. Combined with the variables above the path should illuminate itself.

Businesses will eject most internal IT functions, preferring to use vendors instead.

The business will retain a small number of super elite IT people who are extremely fluent in both business and IT.

These business/IT (BIT) people basically manage vendors in order to best achieve the goals of the business.

90% of IT workers work for vendors / consultancies.

Infosec becomes vastly more data-driven in terms of what works for security and what does not, driven by insurance companies being the first groups incentivized to have this information.

Insurance determine the infosec standards because they have the data about what works.

Because they have the data, they know that certain projects need certain types of testing, and other types need other approaches.

Based on the type of project you have, it’s business sensitivity, how many times its been assessed in the past, etc., there will be a best-fit type of assessment for that project.

The variables are:

How sensitive the project is, i.e. the trust level of testers required to work on it.

Automated vs. manual testing.

How many testers are used.

Incentivization / payment structure.

The knowledge of the business required to provide valuable results.

The BIT person will reach out to several vendors and request an assessment with the precise mixture of these components.

Some vendors will excel at specific areas, such as high-trust testers, or testers who know a particular business.

Many large testing vendors will really be exchanges that can find any combination of individual to fit a given need.

The BIT will pick one vendor that has the best mix, and the work will get done.

Back to the present

So the future of testing is not a race to differentiation, it’s a race to similarity. Both penetration test companies and bounty companies need to become flexible enough to handle this entire range of capabilities.

Some assessments need highly vetted people, even if it’s just one or two. Other assessments need large numbers of people, no matter their background or alignment. Some require deep relationships with, and knowledge of, the customer. Others need no context whatsoever.

The truth is, as a BIT, you don’t care who you’re using as long as you can trust the company and its results. If you can provide better results, and better guidance on how to reduce risk for the company—all without breaking that precious trust that the whole thing is based on—you will do fine.

Now, who do you think is better positioned to make this move?

Or, put another way, is it easier for:

Security services companies with deep relationships with companies built over years or decades to add a researcher program that brings hundreds or thousands of testers under their banner at varying levels of trust, and to then build/buy a platform for taking managing them finding bugs for their customers, or…

For companies based solely on having a vulnerability platform to build the internal trust required to be trusted for ANY type of project the customer has?

I think it’s it’s the former.

I think it’s a whole lot easier for a trusted security services company to be able to add testers to their bench than it is for pure-play bounty companies to embed deeply into companies as a trusted advisor.

But either way, that’s what the race looks like. And both company types must ultimately do both or face extinction.

Longer term It’s all about the testing talent

The funny part is that, long term, it actually doesn’t matter which model wins between pure-play bounty company and traditional testing company. The future of work described above is only an intermediary step, and the next stage of evolution presents a threat to testing companies themselves.

What evolution am I talking about?

To answer that, ask yourself who actually matters in this mix. The most important players in a security assessment are the tester and the customer. Everyone else is a middleman, i.e., a bunch of taxi drivers in a world of ride sharing.

There is, of course, a component of, “Who are you going to sue if something goes wrong?”, and right now that dynamic heavily favors having a reputable testing company (not a bounty company) between the tester and the customer. But as the individual-based economy (and the technology-based trust infrastructure that powers it) gains acceptance, this will quickly decline as a factor.

As I talk about in The Real Internet of Things, individuals will be rated by trust, and they will win or lose jobs based on this rating. As the infrastructure grows for tracking such meta, including one’s trustworthiness, how well they perform, how well they work with others, etc., having the middle-person will be needed less and less. The better the middle tech layer becomes at finding matches and ensuring quality, the less a third party is needed between the customer and the actual provider of the service.

In short, both the traditional testing and bug bounty companies represent the old, taxi model of staffing security engagements, and they’re both in line to be replaced by the individual-based gig economy.

That’s why I laugh when I see the industry so obsessed with the distinction between being penetration tester, a researcher, a bounty player, or whatever specific title we wish to assign. In an individual-based economy this distinction becomes arbitrary.

Testers will be testers with a set of skills. They might have a regular-ish job with a particular staffing company, while they’re also doing other contracts on the side, while they’re also pursuing their own research as well. What are they? Pentesters? Bounty people? Researchers?

Yes, yes, and yes.

The future of security testing is individual-based and non-binary, and if you’re a third party in between them and the customer, you’re destined to be in a bad position.

This is why I can’t get too worked up about the bounty vs. pentest debate anymore. In the overall story arc of where security testing is going, it’s a moot point. Both models are intermediary, and the future is coming.

I look forward to the purity that individual-based testing will bring. It will simply be people with skills and reputations being harnessed to solve problems. And that’s the future of work, not just security testing.

Let’s stop fighting about who’s better at the old models, and start thinking about how to get to the new one.

Notes

Keep in mind that this transition will take time and will have many different phases. There will still be entities that pop up to pre-filter resources, like exchanges, that companies can buy from. But all of these solutions are temporary fixes to the technological problem of purchasers not being able to fully trust the rating systems. As those systems approach a realistic representation of quality and trust, the third-party vouching and liability services will become less needed and less valuable.

Insurance will be another solution to the liability problem. I can imagine a thriving insurance market where highly rated individuals run with insurance policies that help their clients relax about using them. So not only will they have high ratings in dependability, trustworthiness, and results quality, but they’ll also be covered for millions of dollars in the event of something bad happening. This will further diminish the need for a third party in the middle to take on liability.

I’ve had these thoughts for years now and have been reticent to share them. For one, I work at a testing company. Second, one of my favorite humans in the world works at Bugcrowd, and my buddy Jeremiah Grossman is an advisor for them as well. Plus I have many other friends there that I care about, so I want to see all of them, as well as my own company, thrive. But there’s politics surrounding the topic—politics that get worse when marketing departments get involved and start slinging poo at each other. This happened recently, coming from the bug bounty companies, and I decided to write this as a reminder that the whole debate is an exercise in deck chair placement on the Titanic. Let’s be smarter and better.

If you’re wondering where this meta on individuals will be stored, such as their testing quality, their trustworthiness, their dependability, etc., I think the answer is in large, universal tech layers like LinkedIn, FICO, Insurance companies, etc. It’ll be all about massive databases of people, transactions, ratings, and fraud detection and defense. These companies will link job seekers with job providers, and everyone will run the WORK app on their phone like ride share drivers do now. Except it’ll be for all of your skills, not just one of them. This is how testers will find gigs—they’ll come to them automatically based on the customer’s need combined with their skillset, just like Uber and Lyft find drivers based on where you need to go, at what time of day, for how many people.

Many of these concepts are talked about in more depth in my book, The Real Internet of Things.

__

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I curate the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

Information Security Assessment Types

How Cybersecurity Insurance Will Take Over InfoSec

Bug Bounty Ethics and the Ubering of Pentesting

Ideas

My RSA 2017 Recap

June 29, 2017

One Answer to Failing Advertising is Customized Product Discovery

Everyone hates bad advertising, which is why the industry is in a freefall. But what does it mean to be bad advertising? Is there such a thing as good advertising?

I think there is, and I think the way to tell the difference is to simply ask yourself if you consider the thing you’re being shown to be:

An annoyance, or

A service

If it’s annoying, it’s bad. That means that the thing you’re being shown is not something you’d ever buy, consider, share, or otherwise care about. It’s not matched to you in any way, or there’s some sort of other disconnect that otherwise puts you off (like being pitched wedding information during a painful divorce).

So that’s bad.

Good ads are indistinguishable from someone paying a service to find cool things for you. So imagine you just want to know the coolest bags, tech gadgets, vacations, services…whatever. And you’re willing to pay $100 a month for this service.

And imagine that the way they deliver this service is not to have you come to a designated location to browse options, but instead they subtly slip the products they find right into your normal daily workflow. So while you’re sitting at a stoplight. While you’re on a train. While you’re working out. While you’re browsing the internet. Etc.

Imagine that this service is excellent. It constantly finds items for you that you would have never found otherwise, but that you absolutely enjoy, and when you see them you are frequently delighted and happy that you paid for the discovery service.

That’s what good ads should be. And if any ad company wants to survive, that’s what they must become.

Facebook is getting pretty close to this already. I think I might have bought around 3-5 items from Facebook that I genuinely enjoyed learning about. Of course they’re using my data, data about who I like and follow, and a ton of machine learning to figure out the products I’d like to see, but that’s just a given at this point. Anyone trying to serve ads who can’t do this is basically doomed. See the industry freefall for reference.

So the point is this: good ad services don’t feel like ads at all. They feel like paid discovery services for the rich.

As a consumer, ask yourself what kind of ads you would be willing to tolerate, and why. Hopefully you’ll see some examples of ads that you enjoyed, and perhaps they’ll have this quality to them.

And as a company doing advertising, ask yourself whether or not the delivery mechanism for your ad is tuned enough to be mistaken for a paid service. If it’s not, you’re likely annoying someone and wasting a lot of money. Try to reach the standard of paid service in your delivery. If you can pull it off, your campaign is likely to be wildly successful.

Everyone is overwhelmed with information, and they’re tired of seeing things that aren’t relevant. Individually tuned, curated discovery of new products and services is where the game is at.

__

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I curate the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

An NMAP Primer

Lifecasting: What It Is and How It Will Change Society

Why Google Sucks at Ecosystems

[ ANALYSIS ] Internet Trends Report 2016

Summary: Spent

June 27, 2017

Unsupervised Learning: No. 83

This week’s topics: Petya ransomware worm, RNC breach, Anthem settlement, Russians want source code, risk ratings, patching, ICOs, ideas, discovery, recommendation, aphorism, and more…

This is Episode No. 83 of Unsupervised Learning—a weekly show where I curate 3-5 hours of reading in infosec, technology, and humans into a 15 to 30 minute summary.

The goal is to catch you up on current events, tell you about the best content from the week, and hopefully give you something to think about as well.

The show is released as a Podcast on iTunes, Overcast, Android, or RSS—and as a Newsletter which you can subscribe to and get previous editions of here.

Newsletter

Every Sunday I put out a curated list of the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans.

I do the research, you get the benefits. Over 5K subscribers.

The podcast and newsletter usually go out on Sundays, so you can catch up on everything early Monday morning.

I hope you enjoy it.

__

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I curate the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

Unsupervised Learning: No. 78

Unsupervised Learning: No. 76

Unsupervised Learning: No. 73

Unsupervised Learning: No. 75

Unsupervised Learning: No. 72

3 Factors That Determine the Effectiveness of a Worm

With WannaCry and now with Petya we’re getting to see how and why some ransomware worms are more effective than others.

[ Jul 3, 2017 — It’s now pretty well accepted that Petya wasn’t ransomware but a wiper instead. The post still applies to ransomware, though. ]

I think there are 3 main factors: Propagation, Payload, and Payment.

Propagation: You ideally want to be able to spread using as many different types of techniques that you can.

Payload: Once you’ve infected the system you want to have a payload that encrypts properly, doesn’t have any easy bypass to decryption, and clearly indicates to the victim what they should do next.

Payment: Finally, you need to be able to take in money efficiently and then actually decrypt the systems of people who pay. This piece is crucial otherwise people will soon learn that you can’t get your files back no matter what and will be inclined to just start over.

WannaCry vs. Petya

WannaCry used SMB as its main spreading mechanism, and its payment infrastructure lacked the ability to scale. It also had a killswitch, which was famously triggered and that stopped further propagation.

Petya seems to be much more effective at the spreading game since it’s using not only SMB but also wmic, psexec and lsasump to get onto more systems. This means it can harvest working credentials and spread even if the new targets aren’t vulnerable to an exploit.

[ NOTE: This is early analysis (Tuesday morning) so some details could turn out to be different as we learn more. ]

What remains to be seen is how effective the payload and the payment infrastructures are. It’s one thing to encrypt files, but it’s something else entirely to set up an infrastructure to have hundreds of thousands of individual systems send you money, and for you to send them each decryption information.

That last piece is what determines how successful, financially speaking, a ransomeware worm is. This is, of course, assuming that the primary goal was to make money, which I’m not sure we should take as a given.

Other questions

Manny attributed WannaCry to North Korea. Do they think the new worm is from the same origin?

What are defenses against non-exploit-based spreading mechanisms?

What are we learning about worm defense from both of these instances?

Sounds like it’ll be an interesting next few days, at the very least.

Notes

I’m sure there are much more thorough ways to analyze the efficacy of worms. These are just three that came to mind while reading about Petya and thinking about it compared to WannaCry.

Thanks to Michael A. for the updated information regarding spreading methods.

__

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I curate the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

Multi-dimensional Vulnerability Hierarchies

Windows File Sharing: Facing the Mystery

My Explanation for the Sudden Rise in Ransomware

An ICS/SCADA Primer

Ideas

3 Elements That Determine the Effectiveness of a Worm

With WannaCry and now with Petya we’re getting to see how and why some ransomware worms are more effective than others.

I think there are 3 main factors: Propagation, Payload, and Payment.

Propagation: You ideally want to be able to spread using as many different types of techniques that you can.

Payload: Once you’ve infected the system you want to have a payload that encrypts properly, doesn’t have any easy bypass to decryption, and clearly indicates to the victim what they should do next.

Payment: Finally, you need to be able to take in money efficiently and then actually decrypt the systems of people who pay. This piece is crucial otherwise people will soon learn that you can’t get your files back no matter what and will be inclined to just start over.

WannaCry vs. Petya

WannaCry used SMB as its main spreading mechanism, and its payment infrastructure lacked the ability to scale. It also had a killswitch, which was famously triggered and that stopped further propagation.

Petya seems to be much more effective at the spreading game since it’s using not only EternalBlue but also credential sharing / PSEXEC to get onto more systems. This means it can harvest working credentials and spread even if the new targets aren’t vulnerable to an exploit.

[ NOTE: This is early analysis (Tuesday morning) so some details could turn out to be different as we learn more. ]

What remains to be seen is how effective the payload and the payment infrastructures are. It’s one thing to encrypt files, but it’s something else entirely to set up an infrastructure to have hundreds of thousands of individual systems send you money, and for you to send them each decryption information.

That last piece is what determines how successful, financially speaking, a ransomeware worm is. This is, of course, assuming that the primary goal was to make money, which I’m not sure we should take as a given.

Other questions

Manny attributed WannaCry to North Korea. Do they think the new worm is from the same origin?

What are defenses against non-exploit-based spreading mechanisms?

What are we learning about worm defense from both of these instances?

Sounds like it’ll be an interesting next few days, at the very least.

Notes

I’m sure there are much more thorough ways to analyze the efficacy of worms. These are just three that came to mind while reading about Petya and thinking about it compared to WannaCry.

__

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I curate the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

Multi-dimensional Vulnerability Hierarchies

Ideas

An ICS/SCADA Primer

How to Build a Successful Information Security Career

A vim Tutorial and Primer

June 25, 2017

I’m Selling a Late 2013 MacBook Pro

My friend Saša is selling his MacBook Pro from late 2013 for $1,700 so that he can buy a MacBook. Here are the specs:

Retina

2.6 Ghz i7 (4 cores)

16 GB memory

1 TB SSD

1.5 GB dedicated video card

Model Name:MacBook Pro

Model Identifier:MacBookPro11,3

Processor Name:Intel Core i7

Processor Speed:2.6 GHz

Number of Processors:1

Total Number of Cores:4

L2 Cache (per Core):256 KB

L3 Cache:6 MB

Memory:16 GB

Boot ROM Version:MBP112.0138.B25

SMC Version (system):2.19f12

Serial Number (system): (redacted)

Hardware UUID: (redacted)

I’ve known Saša for almost 10 years, and he’s one of my closest personal friends. He’s an executive at a Fortune 10 company, and he’s extremely anal about all his possessions, as you can see from the images. He has all the original packaging.

If you’re interested, you can email me and I’ll put you in touch with him.

__

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I curate the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

The Ultimate Speed Guide for WordPress on NGINX

5X WordPress Speed Improvement with W3 Total Cache

A Varnish Primer

A DNS Primer

On Giving Advice to Friends

June 23, 2017

Gun Control and British Terrorism

I didn’t write about this immediately because it seemed insensitive, but I want to ask a couple of simple questions about the various terrorist attacks in Britain.

If you’re a “more guns equals more safety” type of person, do you honestly believe that the knife attacks in Britain would have been less deadly if guns were easy to get in the country? So, let’s say that it’s fairly easy to get an AR-15, multiple Glocks, and plenty of ammunition. Would the same terrorists armed with the same weapons (instead of knives) have done more or less damage?

Before you answer, let’s assume that some decent percentage of the population is also armed with a Glock or equivalent. Let’s say 25%, which seems high even for the United States.

Now, given both sides being armed in this way, would there be more or fewer deaths and casualties as compared to there being very few guns, i.e., so few that terrorists attack with vehicles and knives.

My intuition is that there would be far more damage, and far more deaths and casualties.

It seems to me that you’d need a population of 50-75% undercover cops before you’d be able to accurately take out attackers before they could do more damage than they could with a knife, and those are numbers that aren’t realistic.

To me this is a case in point of the gun control side being more right. Of course, it’s a whole separate matter of whether it’s possible to get gun numbers down to British levels. The argument is moot if they’re already saturated in a society as with the U.S.

Anyway, curious if you guys see it differently.

__

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I curate the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

The Broken Conversation About Gun Violence

A Liberal Gun Owner Explores Existing Data

My Current Thoughts on Gun Control

A Simple Answer to the Question of Whether Guns Make Us More or Less Safe

A Logical Approach To Gun Laws

Daniel Miessler's Blog

- Daniel Miessler's profile

- 18 followers